public admi istratio & regio al studies - Facultatea de Drept ...

public admi istratio & regio al studies - Facultatea de Drept ...

public admi istratio & regio al studies - Facultatea de Drept ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

2-2008PUBLICADMIISTRATIO®IOALSTUDIES

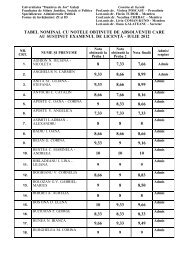

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759PUBLIC ADMIISTRATIO & REGIOAL STUDIESo.2/2008DIRECTORPh.D. Professor ROMEO IONESCU, Dunarea <strong>de</strong> Jos University, RomaniaEDITORIAL BOARDEditor-in-ChiefPh.D. Associate Professor, RADUCAN OPREA, Dunarea <strong>de</strong> Jos University,RomaniaEditorsPh.D. Associate Professor VIOLETA PUSCASU, Dunarea <strong>de</strong> Jos University,RomaniaPh.D. Lecturer FLORIN TUDOR, Dunarea <strong>de</strong> Jos University, RomaniaINTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARDDr. ELEFTHERIOS THALASSINOS, Piraeus University, Greece,European Chair Jean Monnet, Gener<strong>al</strong> Editor of European Research StudiesJourn<strong>al</strong> and Foreign Policy MagazineDr. PIERRE CHABAL, Universite du Havre, Expert of the Institut <strong>de</strong>Relations Internation<strong>al</strong>es et Strategiques ParisDr. LUMINIłA DANIELA CONSTANTIN, A.S.E. Bucharest, Presi<strong>de</strong>nt ofRomanian Region<strong>al</strong> Science AssociationDr. ANDREAS P. CORNETT, University of Southern DenmarkDr. DANA TOFAN, University of Bucharest, Gener<strong>al</strong> Secretary of PaulNegulescu Institute of Administrative SciencesDr. AGNIESZKA BITKOWSKA, University of Finance and Management,WarsawDr. GIORGOS CHRISTONAKIS, Expert of Foreign Affairs, Member ofNation<strong>al</strong> Centre of Public Admin<strong>istratio</strong>n & Loc<strong>al</strong> Government, Greece.3

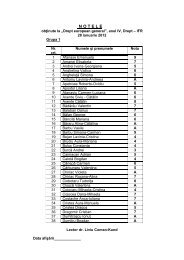

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759CONTENTSTHE METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH OF REGIONAL COSTS-BENEFITS BALANCE FOR ROMANIA AFTER ITS ADHERING TOTHE EUROPEAN UNION………………………………………………...Ionescu Victor RomeoBOOK REVIEW………………………………………………………………Carmen-Beatrice PăunaFORECASTS ON THE EVOLUTIONS OF THE MAIN AGGREGATESOF THE PUBLIC PENSION SYSTEM GIVEN THE PASSING OF THEROMANIAN ECONOMY FROM THE STATUTE OF “TRANSITIONECONOMY” TO THAT OF MARKET ECONOMY – NECESSITY,CARRYING OUT AND IMMEDIATE EFFECTS…………………………Georgeta ModigaTHE INTRASTATE STATISTICAL DECLARATION – A WAY OFGETTING TO KNOW THE ECONOMIC PROCESSES AND OFPREDICTING THE COMMERCIAL FLOW AT THE LEVEL OF THEREGIONS OF DEVELOPMENT……………………………………………Florin TudorTHE TYPOLOGY OF PERIOD OF TRANSITION AND ITSSPECIFICITY REFLECTION IN CONSTITUTIONAL FIELD(A COMPARATIVE APPROACH)…………………………………………Marwan Hayel Abdulmoula AssadTHE ACTUAL IMPLICATIONS OF EUROPEAN UNION MEMBERSTATE QUALITY…………………………………………………………….Mihaela-Adina ApostolacheCHANGES IN THE STRUCTURE OF SMALL AGE AND SEXGROUPS OF THE FULL-AGED POPULATION IN GALATI DURINGTHE CONTEMPORARY PERIOD…………………………………………Iulian Adrian Şorcaru52530435361704

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759THE METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH OF REGIONALCOSTS-BENEFITS BALANCE FOR ROMANIA AFTER ITSADHERING TO THE EUROPEAN UNION1. Requests from the European Union2. An<strong>al</strong>ysis of the financi<strong>al</strong> fluxes3. The perspective of Romanian economy during 2007-2013Ph.D. Professor Romeo IonescuDunarea <strong>de</strong> Jos University, Romania 1AbstractThe necessity of integration implies important efforts for the newest MemberStates. Our whole an<strong>al</strong>ysis is focused on the i<strong>de</strong>a of Europeanization and its politic<strong>al</strong>,economic, juridic<strong>al</strong> and <strong>admi</strong>nistrative criteria.In or<strong>de</strong>r to point out thet costs and benefits of Romania’s integration, we used aquantitative c<strong>al</strong>culation.Other part of this paper uses the evolution of macroeconomic indicators inRomania in or<strong>de</strong>r to estimate some specific ten<strong>de</strong>ncies.On the other hand, the economic <strong>de</strong>velopment in Romania will accelerate in or<strong>de</strong>rto achieve 6% in 2013.1. Participation to an integrationist organisation implies more andgreater transformations for <strong>al</strong>l Member States. The dimension of thesetransformations <strong>de</strong>pends on the level of integration achieved by the<strong>regio</strong>n<strong>al</strong> group and it expresses institution<strong>al</strong> re<strong>de</strong>finitions and policymaking.The transformations connected with economic policies’implementation in Member States are evi<strong>de</strong>nt as a result of a greater1 Ionescu Romeo, Aurel Vlaicu no.10, 800508 G<strong>al</strong>atz, Romania, Dunarea <strong>de</strong> JosUniversity, G<strong>al</strong>atz, Romania, phone 0040236, fax 0040236,ionescu_v_romeo@yahoo.com, Vice-presi<strong>de</strong>nt of the Romanian Region<strong>al</strong> ScienceAssociation (A.R.S.R); Foun<strong>de</strong>r member of Romanian Gener<strong>al</strong> Association of theEconomists (AGER); Laureate of the Romanian Government Ordain for TeachingActivity as Knight; Member of the Research Board of Advisors, AmericanBiographic<strong>al</strong> Institute, U.S.A.; Member of European Region<strong>al</strong> Science Association;Member of the European Region<strong>al</strong> Science Internation<strong>al</strong>; Multiplication ofEuropean information un<strong>de</strong>r the European Commission in Romania; Member ofthe Internation<strong>al</strong> Advisory Board for Romanian Journ<strong>al</strong> of Region<strong>al</strong> Science, listedin DOAJ database.5

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759economic and monetary integration. These transformations are the resultof the transfer of <strong>de</strong>cision<strong>al</strong> competences in sector policies from eachMember State to supranation<strong>al</strong> organisms. As a result, the Europeanfactor becomes an important component of policy making for MemberStates.On the other hand, the European factor implies some restrictionsin <strong>de</strong>finition and implementation of economic policies in each MemberState. So, these Member States have to accept extern<strong>al</strong> condition<strong>al</strong>ity inbuilding their economic policies.The actu<strong>al</strong> approach is to <strong>de</strong>fine and to i<strong>de</strong>ntify the implicationsof the transfer of competences in economic policy un<strong>de</strong>r theEuropeanization concept (Borzel T, 1999).Europeanization is a building process of form<strong>al</strong> and inform<strong>al</strong>dissemination and institution<strong>al</strong>ization, of establishing rules, procedures,economic paradigms, know-how, common i<strong>de</strong>as and v<strong>al</strong>ues in or<strong>de</strong>r toconsolidate E.U.’s logic<strong>al</strong> <strong>de</strong>cision<strong>al</strong> process and to support institution<strong>al</strong>and politic<strong>al</strong> structures and nation<strong>al</strong> economic policies in the MemberStates (Rafaelli E., 2001).At the beginning, the an<strong>al</strong>ysis of Europeanization was focusedonly on the Member States. Nowadays, the an<strong>al</strong>ysis was exten<strong>de</strong>d tocandidate countries too. The basic i<strong>de</strong>a is that Europeanization impliesapplying of European economic governance mo<strong>de</strong>l to candidatecountries. It affects the actu<strong>al</strong> Member States and candidate countries tooby using specific mo<strong>de</strong>ls, regulations and common policies which implysubstanti<strong>al</strong> re<strong>de</strong>finitions for nation<strong>al</strong> policies and for the institution<strong>al</strong>framework of every country (Hughes J., Sasse G., Gordon C., 2002).The main instrument of Europeanization for the candidatecountries is connected with the European condition<strong>al</strong>ity especi<strong>al</strong>ly aboutadhering criteria: politic<strong>al</strong>, economic, juridic<strong>al</strong> and <strong>admi</strong>nistrative.Moreover, Europeanization represents an institution<strong>al</strong>arrangement, a regulation, a comport standard which <strong>al</strong>lows aconnection between advantages of adhering to the E.U. and duties as aMember State.As a result, European condition<strong>al</strong>ity asks for institution<strong>al</strong>transformations about economic policies of the Member States wherethere are differences between European and nation<strong>al</strong> frameworks. Theseadjustments imply costs for candidate countries. On the other hand, thebenefits from adhering to the E.U. can be maximized only if there is ahigh compatibility between nation<strong>al</strong> policies and institution<strong>al</strong> frameworkand European institution<strong>al</strong> mo<strong>de</strong>l of adopting these policies.6

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759The European condition<strong>al</strong>ity is stipulated into Copenhagenadhering criteria and they represent an important vector for convergenceensuring. These conditions have to be ev<strong>al</strong>uated before and after theadhering process.For Romania, the same conditions have influenced the rhythmand direction of the politic<strong>al</strong> and economic transformations, <strong>de</strong>creasedthe <strong>de</strong>cision<strong>al</strong> freedom <strong>de</strong>gree and generated a relative <strong>de</strong>cision<strong>al</strong><strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce <strong>de</strong>gree (path <strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce) of the Romanian authorities toEuropean authorities (Lataianu G., 2003).The juridic<strong>al</strong> criteria represent one of the most important form<strong>al</strong>elements of the European condition<strong>al</strong>ity which influent the efficiency ofthe Romanian enterprises.Romania prepared its adhering to the E.U. in or<strong>de</strong>r to implementEuropean standards. This process continues with new politic<strong>al</strong> an<strong>de</strong>conomic post-adhering transformations.The impact of the adhering process is presented at economic andpolitic<strong>al</strong> levels as direct and indirect actions in table number 1 (PrestonC., 1997).The main costs for Romania connected with its adhering and postadheringevolutions are presented in figure number 1.The implementation of the acquis generates costs connected with:change of institution<strong>al</strong> framework, costs with specific human resourcesand costs of economic policy. Romania passed on these costs before itsadhering to the E.U.Other costs are those connected with the standardsimplementation as they are <strong>de</strong>fined by European regulations andpolicies. These costs are covered at institution<strong>al</strong> level (<strong>public</strong><strong>admi</strong>n<strong>istratio</strong>n) and microeconomic level too. They inclu<strong>de</strong>:mo<strong>de</strong>rnization of transport infrastructure, labour and soci<strong>al</strong> standards,consumers’ protection, qu<strong>al</strong>ity and environment standards. The samecosts are those connected with free movement of goods, services, personsand capit<strong>al</strong>.All these costs are effective at microeconomic level and are able toaffect the efficiency of Romanian enterprises. It’s very difficult to divi<strong>de</strong>these costs into ante and post-adhering costs because the implementationof a European standard in Romania can need longer transition period(more than 10 years for environment standards implementation, forexample).There are costs connected with the statute of member of the E.U.too and they inclu<strong>de</strong> contributions to common budget and participation7

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759to European institutions. Some of these costs were supported beforeadhering as co-financing costs to European Funds (PHARE, SAPARD,ISPA).Fin<strong>al</strong>ly, we can t<strong>al</strong>k about the costs of Romanian economy’smo<strong>de</strong>rnization in or<strong>de</strong>r to face the competition of European enterprises.Most of these costs result from the disparities between Romanian andEuropean economic, politic and soci<strong>al</strong> standards.The estimation of the costs of Romania’s adhering to the E.U. isvery difficult as a result of a high dynamic of economic, politic<strong>al</strong> andsoci<strong>al</strong> transformations within the E.U.On the other hand, there are positive effects of the Europeancondition<strong>al</strong>ity too. One of them is the financi<strong>al</strong> and technic<strong>al</strong> assistancereceived by Romania from the E.U. in or<strong>de</strong>r to create leg<strong>al</strong> andinstitution<strong>al</strong> framework necessary for a good function of the economy.Other benefits are acceleration of economic reforms, economic growthand greater efficiency for Romanian enterprises.The main benefits of Romania’s adhering to the E.U. are thefollowing:• supplementation and diversification of financi<strong>al</strong> resources:Romania has access to Structur<strong>al</strong> and Cohesion Funds. The benefits ofthis access can be c<strong>al</strong>culated at the end of the actu<strong>al</strong> financi<strong>al</strong> period2007-2008;• benefits form the statute of Member State: participation to singlemarket, to European Monetary Union, a better support for nation<strong>al</strong>interests in European institutes;• reform acceleration and <strong>de</strong>finition of nation<strong>al</strong> economic policiesun<strong>de</strong>r E.U.’s assistance.The costs and benefits of adhering to the .E.U. can be estimatedusing budget implications too. We think about some specific chapterssuch as: contributions to European budget, CAP and structur<strong>al</strong> funds for<strong>regio</strong>n<strong>al</strong> policy.From a methodologic<strong>al</strong> point of view, it’s difficult to make thedistinction between integration effects and those of the transitionprocess. On the other hand, the dichotomy winner/loser is relative. Aspecific sector can be winner or looser during the integration process, butit isn’t the same situation with <strong>al</strong>l enterprises or individu<strong>al</strong>s from thatsector.Moreover, sector an<strong>al</strong>ysis isn’t correspon<strong>de</strong>nt to positive/negativeinfluences on society evolution. A loser sector can liberate resources for8

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759other sectors and can improve the <strong>al</strong>location efficiency of the economicresources (Daianu D., 2001).Integration represents achievement of socio-economic objectiveswhich are <strong>de</strong>fined and periodic<strong>al</strong>ly actu<strong>al</strong>ized according to the needs of agiven historic<strong>al</strong> moment.Using economic mo<strong>de</strong>ls, convergence is <strong>de</strong>fined as a set of specificindicators which are selected according to more than convergence needs.The correct <strong>de</strong>finition of these criteria differs from a moment to momentand from case to case.For the beginning, Romania had to achieve Copenhagen criteriaabout a function<strong>al</strong> market economy which is able to face the competitivepressure of the European enterprises.On the other hand, the costs and benefits of European integrationcan be an<strong>al</strong>ysed in different manners.As bilater<strong>al</strong> financi<strong>al</strong> fluxes between E.U. and Romania, we mustan<strong>al</strong>yse the sums financed by the E.U. and Romania’s contribution todifferent European programs.Furthermore it may be better to inclu<strong>de</strong> the whole budgetaryeffort, including the effects of the <strong>de</strong>creas custom taxs.Another important element is the great impact on macroeconomy, including changes in labour efficiency and employment rate.The reported costs and benefits can vary between theseapproaches. As bilater<strong>al</strong> financi<strong>al</strong> fluxes, integration becomes favourablefor every country.Using the whole budgetary effort and the impact on macroeconomy, integration becomes less favourable because expendituresaren’t associated with investments as a result of the fact that their futureeffects are not ev<strong>al</strong>uated.A relatively correct and maximum possible ev<strong>al</strong>uation of theresults is possible only using the impact on macro economy, which is themain economic element. This is the only level of an<strong>al</strong>ysis in which we canestablish the inter-condition<strong>al</strong>ity between macroeconomic indicatorssuch as glob<strong>al</strong> efficiency, employment rate and inflation.Using macroeconomic level for costs-benefits report an<strong>al</strong>ysis, wecan <strong>de</strong>termine the direct effects of the integration process.The costs of integration are connected with: participation toEuropean programs, obligatory investments and losses produced bypartners or possible pen<strong>al</strong>ties.The benefits of European integration are the following: greatermonetary fluxes, facile access to programs, tra<strong>de</strong> and labour movement,9

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759direct results from acquis’ implementation and the growth of efficiency(see figure no.1).2. The direct financi<strong>al</strong> implications represent a part of the costsand benefits of European integration which can be estimated using aquantitative c<strong>al</strong>culation.As a result, we can an<strong>al</strong>yse the probable effects of the Europeanfinanci<strong>al</strong> package for Romania and Bulgaria during 2007-2009. Thispackage is a component of the financi<strong>al</strong> perspective 2007-2013.The term of financi<strong>al</strong> package means <strong>al</strong>l direct financi<strong>al</strong> andbudgetary implications of the adhering negotiations about Agriculture(Chapter no. 7), Region<strong>al</strong> policy and structur<strong>al</strong> instruments coordination(Chapter no. 21) and Financi<strong>al</strong> and budgetary framework (Chapter no.29).The European financing was divi<strong>de</strong>d into chapters and years,using the procedures applied to the other 10 Member States whichadhered in 2004. As a result, the E.U. financi<strong>al</strong> assistance for Romaniaand Bulgaria is about 11.3 billion Euros during 2007-2009 (Commission ofEuropean Communities, 2004).Agriculture will receive 4037 million Euros which will be divi<strong>de</strong>dinto: market measures (732 million Euros), direct payments (881 millionEuros) and rur<strong>al</strong> <strong>de</strong>velopment policy (2424 million Euros).The European Structur<strong>al</strong> and Cohesion Funds for Romania andBulgaria cover 5973 million Euros.Intern<strong>al</strong> policies cover 1304 million Euros. This sum isn’t divi<strong>de</strong>dbetween Romania and Bulgaria.The same situation is about <strong>admi</strong>nistrative expenditures of 346million Euros.The budgetary effort for Romania is c<strong>al</strong>culated according to apercentage of 1.14% from its forecast budget during 2007-2009. As aresult, Romania has to pay 7.4 billion Euros during 2007-2009The engagement for financi<strong>al</strong> package for Romania covers 11287million Euros from E.U. and an intern<strong>al</strong> contribution of 7411 millionEuros (see figure no.3).The effective payments from the European budget to theRomanian budget will be sm<strong>al</strong>ler for procedur<strong>al</strong> causes. An acceptedproject can be financed from engaged sums during a single year. Butthese payments will be ma<strong>de</strong> sequenti<strong>al</strong>ly during the effective period ofproject implementation.As a result, the payments <strong>de</strong>pend on effective absorption capacitywhich is <strong>de</strong>termined by the presentation of eligible measures,10

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759institution<strong>al</strong> function<strong>al</strong>ity, management and financi<strong>al</strong> control proceduresin or<strong>de</strong>r to ensure funds and co-financing ensurence.Using Copenhagen methodology, the estimated financingprogram for Romania will be about 8893 million Euros. This suminclu<strong>de</strong>s financi<strong>al</strong> package and the pre-adhering sums which wereengaged before.Romania’s budgetary effort related to the payments is about 5663million Euros (see figure no.4).The net b<strong>al</strong>ance of financi<strong>al</strong> transfers between Romania and E.U.is c<strong>al</strong>culated as the difference between payments proposed by the E.U. infinanci<strong>al</strong> package and Romania’s contribution to the European budget.The fin<strong>al</strong> net b<strong>al</strong>ance has an exceeding of 6346 million Euros (see figureno. 5).The macroeconomic impact of this financi<strong>al</strong> package can’t bereduced only to the absolute v<strong>al</strong>ue of the sums received by Romania. Theprograms and structur<strong>al</strong> actions can generate and support a sustainableeconomic growth at least in agriculture, infrastructure, environment,human resources and soci<strong>al</strong> cohesion growing as a result of rur<strong>al</strong> and<strong>regio</strong>n<strong>al</strong> equilibrated <strong>de</strong>velopment.3. Using the evolution of macroeconomic indicators, the an<strong>al</strong>ysisfor Romania estimates some specific ten<strong>de</strong>ncies.The future integration of Romania into E.U. will support theopportunities for a sustainable economic growth. Even un<strong>de</strong>r presentinternation<strong>al</strong> financi<strong>al</strong> crisis conditions, Romania can achieve a positiverate of economic growth.Internation<strong>al</strong> Monetary Fund (IMF) published itsannu<strong>al</strong> report at the beginning of 2007. This organisation conclu<strong>de</strong>d thatRomania had the highest GDP grow rate from E.U.27 during 2000-2006(130%).In 2006, Romania GDP was about 97.1 billion Euros. Thepreliminary dimension for 2007 is about 115 billion Euros too (see figureno.6).The European money <strong>de</strong>termined an annu<strong>al</strong> economic growth ofabout 2%. During 2007-2013, the v<strong>al</strong>ue of the European Structur<strong>al</strong> Fundsfor Romania will be about 24.1 billion Euros (without Agricultur<strong>al</strong> funds).15.5. billion Euros will be senting for infrastructure, 4.2 billion Euros forproductive sector and 4.4 billion Euros for human resources.The inflation rate was 6.5% in 2006. In May 2007, the EuropeanCommission consi<strong>de</strong>red that the inflation rate in Romania will be about11

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -17594.5% in 2008. The inflation rate will come down at 2.5% till 2012-2013, butRomania will not be able to adhere to euro zone (figure no. 7).On the other hand, average productivity in Romania is 8.7 times lessthan average E.U.-25 productivity (20100 Euros in Romania and 174000Euros in E.U.25). As a result, the average level of the wage in Romania wasabout 280 Euros in February 2007. The greatest wages are in finance,banking sector, <strong>admi</strong>n<strong>istratio</strong>n and services.In 2007, Foreign Direct Investments were about 7 billion Euros. Themain economic sectors which benefited from these FDI are car building,electronic components, building, IT, pharmaceutics and bio-diesel. At theend of 2006, Romania introduced the unique tax revenues of 16% and a lotof facilities for FDI greater than one million Euros. FDI in Romania wereabout 9 billion Euros in 2006, greater with 74.2% than in 2005 (figure no.8)..Romania’s exports were about 25.8 billion Euros in 2006. 18.3 billionEuros represented export in E.U. countries. In 2007, Romanian exports wereabout 30.2 billion Euros.Romania’s imports were 40.7 billion Euros in 2006 and 44.4 billionEuros in 2007.As a fin<strong>al</strong> conclusion, we have to un<strong>de</strong>rstand that Romania has a lotof things to do in or<strong>de</strong>r to achieve E.U. average economic <strong>de</strong>velopment.The chances for the Romanian economy as new member of the E.U.are the following:• macro economy: for the next 5-7 years, it is expected an economicgrowth greater than in E.U.15. Services and <strong>public</strong> he<strong>al</strong>thcare will beimproved. For the beginning, the most <strong>de</strong>veloped sectors in the next yearwill be: leasing, SMEs, telephony, internet, hardware and softwareindustries. The forecasts for 2010 show us a great <strong>de</strong>velopment of financi<strong>al</strong>market, banking, tourism and human resources. On the other hand, suchindustries like: textile industry, wood industry and furniture industry haveto be restructured. But the most <strong>de</strong>veloped industries will be tourism andtransport;• prices: the <strong>de</strong>velopment of the supermarkets will <strong>de</strong>termine a newstructure of the Romanian intern<strong>al</strong> tra<strong>de</strong> and a diminution of most of theprices. The new mo<strong>de</strong>rn intern<strong>al</strong> tra<strong>de</strong> will be 50% from the market in 2010.Nowadays, this tra<strong>de</strong> is about 29%. In or<strong>de</strong>r to obtain a greater market, thesupermarkets will reduce their prices with 10-15%. The absence of the taxeswill <strong>de</strong>termine the movement of the prices from producers to retailers;• free labour movement: the Romanian labour may obtain retiredpayees in the Member States where they work. Nowadays, there are 2million Romanian people which work in other Member States. On the other12

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759hand, 11 Member States liber<strong>al</strong>ized Romanian labour access on their labourmarkets (Czech Re<strong>public</strong>, Estonia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland,Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Swe<strong>de</strong>n and Bulgaria) and 5 introduced aparti<strong>al</strong> liber<strong>al</strong>ization of the Romanian labour access on their markets(France, It<strong>al</strong>y, Hungary, Belgium and Luxembourg);• Common Market: the <strong>public</strong> aids are replaced with EuropeanFunds. On the other hand, Romanian firms may sell their output in thesame conditions with other European firms on a bigger market;• European Funds: during 2007-2013, Romania will benefit of 28billion Euros from Structur<strong>al</strong> Funds. 11 billion Euros will be for agricultureand rur<strong>al</strong> <strong>de</strong>velopment. As a result, we must spend 8.5 million Euros everyday, including Saturday and Sunday;• environment: Romania will receive 29.3 billion Euros for itsenvironment policy. Romania is the only Member State which has 5bio<strong>regio</strong>ns (from the tot<strong>al</strong> 11 bio<strong>regio</strong>ns from the E.U.);• fuels: The cote of the ecologic<strong>al</strong> diesel oil will be 5.17% in 2010.Romania has the greatest surfaces with rape, soy and sunflower;• tra<strong>de</strong> marks and brands: in 2007, 700000 European registered marksare recognized in Romania. Romanian marks have to be registered on theCommon Market. That implies a tax of at least 1200 Euros;• re<strong>al</strong> estate market: price of the building will <strong>de</strong>cline with 10%,except for Bucharest;• banking: <strong>de</strong>velopment of this sector as a result of a great Europeancapit<strong>al</strong> input on the market. The most important banks in Romania are withGerman, French, Austrian and Greek capit<strong>al</strong>. As a result, it is expected a<strong>de</strong>cline of the interest rate.On the other hand, the threats for the Romanian economy as a newmember of the E.U. are the following:• massive bankruptcy: the Romanian forecasts tell us about 60% ofSMEs as a result of a low competitiveness (19 times sm<strong>al</strong>ler than averageE.U.);• higher labour costs and employment migration: the main<strong>de</strong>stinations for Romanian labour are Spain, It<strong>al</strong>y and Greece;• a new structure of intern<strong>al</strong> tra<strong>de</strong>: the little shops will lose 15% of theintern<strong>al</strong> market in 2007;• a low capacity to use European Funds: Romania needs 10000speci<strong>al</strong>ists in European Funds but it has only 1000. The specific trainingmarket was about 9 million Euros in 2007 and the cost of training/capita is160-700 Euros. Nowadays only 25% of Romanian firms are able to apply in13

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759or<strong>de</strong>r to obtain European Funds. For example, Romania spent only 20%from ISPA Fund for environment and transport;• food industry: has the lowest competitiveness. In milk industry, forexample, the productivity is 15 times lower than E.U.25 averageproductivity. There are only two multination<strong>al</strong> firms in this sector: Danoneand Friesland Foods;• low productivity: in more industries, Romanian productivity is 13time less than E.U.-25 average level. This situation will continue for at least5 years. Most of Romanian firms are unable to think glob<strong>al</strong> and act loc<strong>al</strong>.The Romanian economy is more exposed than the economies of theMember States which adhered in 2004 because it has more inhabitants anda greater market. On the other hand, the entrance of the European firms onRomanian market will <strong>de</strong>termine low costs. The Romanian firms will beunable to operate with such little costs;• low GDP per capita: Romanian GDP per capita was 35% for E.U.-25average level in 2005 and it will grow to 37% in 2007.Internation<strong>al</strong> Monetary Fund estimates that the rate of GDPgrowth in Romania will be about 5.5% in 2008. The same instituteforecass a rate of growth of about 4.7% in 2009. It will be a result of <strong>al</strong>ittle growth of intern<strong>al</strong> <strong>de</strong>mand and of the advance of the exportsconnected with a lower <strong>de</strong>mand of the Western Europe.Moreover, the <strong>de</strong>crease of economic growth is connected with the<strong>de</strong>crease of capit<strong>al</strong> fluxes from foreign banks. The foreign capit<strong>al</strong> fluxescan be interrupted by financi<strong>al</strong> turbulences from mature markets,especi<strong>al</strong>ly by loses suffered by the banks in Western Europe.An inverse capit<strong>al</strong> fluxes can produce a breakout of credit marketand a <strong>de</strong>flation of actives’ prices. The most probable effect will be anunwished and sud<strong>de</strong>n stagnation of intern<strong>al</strong> absorption capacitycombined with a painful <strong>de</strong>crease of financing sources for enterprisesand population. On the other hand, the economic <strong>de</strong>velopment in Romaniawill accelerate in or<strong>de</strong>r to achieve 6% in 2013.ReferencesBorzel T, The domestic impact of Europe: institution<strong>al</strong> adaptation in Germanyand Spain, European University Institute, Florence, 1999.Daianu D., Castigatori si perdanti in procesul <strong>de</strong> integrare europeana. Oprivire asupra Romaniei, Centrul Roman <strong>de</strong> Politici Economice, Bucharest,2001.14

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759Hughes J., Sasse G., Gordon C., Saying `Maybe' to the `Return to Europe',European Union Politics, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2002.Lataianu G., Europeanization as a mo<strong>de</strong>rnising factor of post-communistRomania, Graduate School for Soci<strong>al</strong> Research, Warsaw, 2003.Preston C., Enlargement and Integration in the European Union, Routledge,London, 1997.Raffaelli E. A., Antitrust fra diritto nazion<strong>al</strong>e e diritto comunitario, RivistaGiuridica Trimestr<strong>al</strong>e <strong>de</strong>lla Societa It<strong>al</strong>iana <strong>de</strong>gli Autore e Editore, 2001.Commission of the European Communities, A financi<strong>al</strong> package for theaccession negotiations with Bulgaria and Romania, Communication from theCommission, 19.2.204, SEC (2004) 160 fin<strong>al</strong>.Table no.1. The effects of adhering to the E.U.Domain Direct impact Indirect impactEconomy - elimination of tra<strong>de</strong>barriers;- applying of theEuropean competitionpolicy;- implementation of CAP;- access to the EuropeanStructur<strong>al</strong> Instruments.- tra<strong>de</strong> fluxes reorientation;- industri<strong>al</strong> andagricultur<strong>al</strong>restructuration;- <strong>regio</strong>n<strong>al</strong> implications;- adhering to Maastrichtcriteria for convergence tothe E.M.U.;Policy- the prev<strong>al</strong>ence ofEuropean law to thenation<strong>al</strong> law;- direct implementation ofEuropean legislation;- changes of theConstitution andconstitution<strong>al</strong> statute ofnation<strong>al</strong> parliament;- representation andparticipation to European<strong>de</strong>cision<strong>al</strong> process- reorientation of theforeign policy, includingtra<strong>de</strong> diplomacy;- a new manner ofgovernment policiesimplementation;- new mo<strong>de</strong>ls ofrepresentation for societyinterests15

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759COSTS OF ITEGRATIOE.U.BEEFITS OF ITEGRATIOGreater monetaryfluxesFacile access toprograms, tra<strong>de</strong>and labourmovementDirect resultsfrom acquisimplementationand the growth ofefficiencyAcquiscommunitaireImplementationof the EuropeanpoliciesCosts connectedwith the statute ofMember StateCosts of economymo<strong>de</strong>rnizationFigure no.1. Costs and benefits of European integration16

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759Agriculture4037 mill. EurosStructur<strong>al</strong> andCohesion Funds5973 mill. EurosFinanci<strong>al</strong>packageIntern<strong>al</strong> policies1304 mill. EurosAdministrativeexpedintures346 mill. EurosFigure no.2. Financi<strong>al</strong> package for Romania and Bulgaria during2007-200917

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -17594500400035003000250020001500EuropeanfinancingRomaniancontribution100050002007 2008 2009Figure no.3. Engagement for Romanian financi<strong>al</strong> package during2007-2009 (mill. Euros)18

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759350030002500200015001000EuropeanpaymentsRomanianpayments50002007 2008 2009Figure no.4. Payments for Romanian financi<strong>al</strong> package during 2007-2009 (mill. Euros)19

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759350030002500200015001000EuropeanpaymentsRomania'scontributionNet b<strong>al</strong>ance50002007 2008 2009Figure no.5. Net b<strong>al</strong>ance for Romanian financi<strong>al</strong> package during2007-2009(mill. Euros)20

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759115110105100GDP bill.euros9590852006 2007Figure no. 6. GDP in Romania21

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -175976543Inflation rate2102006 2007 2008 2012Figure no.7. Inflation rate in Romania (%)22

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -175998765432102005 2006 2007FDI bill.eurosFigure no. 8. FDI in Romania23

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -175945403530252015Exports bill.eurosImports bill. Euro10502006 2007Figure no. 9. Romania’s foreign tra<strong>de</strong>24

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759BOOK REVIEWMari Vaattovaara, Matti Kortteinen, “Beyond polarisation versusprofession<strong>al</strong>isation? A case study on the <strong>de</strong>velopment of theHelsinki <strong>regio</strong>n”, Urban Studies, 2007Carmen-Beatrice PăunaInstitute for Economic Forecasting, BucharestThe <strong>de</strong>cision to make a review of this paper follows both the prestigeenjoyed by its authors and the particular interest shown by speci<strong>al</strong>ists in theeconomic and soci<strong>al</strong> performances achieved in Helsinki, “a pocket-sizemetropolis” (as the area is c<strong>al</strong>led in this very paper).Mari Vaattovaara and Matti Kortteinen belong to the generation ofFinnish researchers with a mo<strong>de</strong>rn vision and approach on urbanism –which <strong>al</strong>so inclu<strong>de</strong>s aspects of urban geography and sociology but <strong>al</strong>sotrends of the economic <strong>de</strong>velopment in urban areas.Mari Vaattovaara <strong>de</strong>livered her doctor<strong>al</strong> thesis in urban geographyat Oulu University in 1999, and is currently professor of Urban Geographyat the Helsinki University. Following her prodigious activity in research inthe field she has been selected as expert and co-ordinator of numerousresearch projects both at a nation<strong>al</strong> and European level. Her rich experienceas professor and in the field of research has been roun<strong>de</strong>d off by that ofauthor of numerous speci<strong>al</strong>ised books, <strong>studies</strong> and articles published byfamous internation<strong>al</strong> publishing houses.Matti Kortteinen is one of the Finnish avant-gar<strong>de</strong> speci<strong>al</strong>ists in thefield of urban <strong>studies</strong> and in his numerous papers that he published heshowed his interest particularly in “pre-urban” spaces, soci<strong>al</strong> <strong>de</strong>limitation,<strong>regio</strong>n<strong>al</strong> and soci<strong>al</strong> segregation in metropolitan areas. Matti Kortteinen<strong>de</strong>livered his doctor<strong>al</strong> thesis at the Helsinki University and has been activefor a long time in the aca<strong>de</strong>mic field as well as a researcher in research<strong>de</strong>partments of the Helsinki University and the Aca<strong>de</strong>my of Finland.Currently, Matti Kortteinen is professor of urban sociology at the HelsinkiUniversity and associate professor in the field of soci<strong>al</strong> research at theLappland University (since 2004) and <strong>al</strong>so associate professor (since 1996) atthat will be part of the Public He<strong>al</strong>th Institute as of 2009). In his capacity as25

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759associate researcher at STAKES he has taken part in numerous Europeanprojects of reference in the field of urban <strong>studies</strong>.As is known, Finland is tradition<strong>al</strong>ly assimilated to a strong pillar ofthe “so-c<strong>al</strong>led Nordic welfare regime”. Internation<strong>al</strong> comparisons indicatethat this country has a relatively low poverty rate and one of the mostequitable distribution systems of revenues in the Western world. Thesenation<strong>al</strong> characteristics related to the urban and housing policies have beencompleted “by a long tradition of soci<strong>al</strong> mixing” existing in the Helsinkidistrict which placed Helsinki, in a classification of European metropolitantowns, on the first place in point of soci<strong>al</strong> and spati<strong>al</strong> b<strong>al</strong>ance 2 .Another reasons why the authors selected the Helsinki district fortheir an<strong>al</strong>ysis is that in the past <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong> it has become one of the topEuropean centres in the field of “ information and communicationtechnologies ”, thanks in particular to the Nokia company, “the worldmarket lea<strong>de</strong>r in mobile communication”.Last but not least, the authors explain their choice of Helsinki districtas subject of their study by the fact that in spite of the period of recessionun<strong>de</strong>rgone by the Finnish early in the 90-ties, (in a much stronger way ascompared to other European states, according to some authors) a b<strong>al</strong>ancewas maintained between „the Nordic welfare state” and a strong„information<strong>al</strong> <strong>de</strong>velopment” 3 . As a conclusion, the authors sign<strong>al</strong> out thatthe Helsinki district could be accepted as a laboratory of experiments inwhich to watch the evolution of urban differences (from the soci<strong>al</strong> an<strong>de</strong>conomic points of view) in par<strong>al</strong>lel with the strong manifestation ofglob<strong>al</strong>isation and the <strong>de</strong>velopment of the IT sector – and in line with theintention of maintaining the „loc<strong>al</strong> policies of soci<strong>al</strong> mixing”.The paper “Beyond polarisation versus profession<strong>al</strong>isation? A casestudy on the <strong>de</strong>velopment of the Helsinki <strong>regio</strong>n” is a reflection of thelogic<strong>al</strong> and chronologic<strong>al</strong> scientific approach. After the authors present theirarguments for choosing this particular topic, they present the historic<strong>al</strong>evolution of the urban aspects in the Helsinki district. After the separationfrom Swe<strong>de</strong>n, during Napoleon’s war, the centre of Helsinki – situated inthe peninsula – <strong>de</strong>veloped an imperi<strong>al</strong> style. The urban <strong>de</strong>velopment of thetown built on the typic<strong>al</strong> outlook of the bourgeoisie, according to which the2 In 19993 In my opinion, as author of this review, a point of interest for future researchcould <strong>al</strong>so be the end of the current crisis that started in the second h<strong>al</strong>f of the year2008 in Europe, as well, in or<strong>de</strong>r to check whether the “Nordic welfare state” is stillsolid.26

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759centre was <strong>de</strong>stined to the well off while the periphery (in this case stripes ofland sometimes separated by water from the peninsula) was mainlyinhabited by workers and the poor population. After the Civil war of 1918,more exactly, starting with the 20-ties, politicians granted speci<strong>al</strong> attentionto the soci<strong>al</strong> integration of the less well off categories of the population.Gradu<strong>al</strong>ly, another i<strong>de</strong>a <strong>de</strong>veloped namely to integrate the houses of thepoorer (in gener<strong>al</strong>, individu<strong>al</strong> houses) with the others, the remainingdifferences being only of an architectur<strong>al</strong> nature. The next stage, around theyears ’44 was to integrate the houses that were private property with thedwellings that were meant for renting in the same area; there was however adifference in this type of estates and this difference was <strong>al</strong>so in point ofarchitecture. A new stage followed as of 1974 namely that of integration ofthe new types of dwellings (block of flats) among the existing ones withoutany architectur<strong>al</strong> difference being ma<strong>de</strong> in this case. The <strong>studies</strong> carried outin the ’80 (and <strong>al</strong>so mentioned by Mari Vaattovaara and Matti Kortteinen)un<strong>de</strong>rline the fact that the soci<strong>al</strong>-economic divi<strong>de</strong> insi<strong>de</strong> the town thusgradu<strong>al</strong>ly diminished. In other words, the authors point to the fact that –<strong>al</strong>sobased on wi<strong>de</strong> scope own an<strong>al</strong>yses according to numerous criteria – in aperiod of increasing soci<strong>al</strong> inequities in the urban areas, the <strong>regio</strong>n ofHelsinki witnessed a spati<strong>al</strong> b<strong>al</strong>ance from the soci<strong>al</strong> and economic point ofview (the record period of b<strong>al</strong>ance being so far the beginning of the ’90). Intheir own an<strong>al</strong>yses, the authors draw attention to a criterion used for thei<strong>de</strong>ntification of the structure of housing in the urban areas, namely: thelevel of education of the people. This criterion has <strong>al</strong>so been used in the<strong>de</strong>velopment of the „soci<strong>al</strong> mixing” policy which in some periods of timeyiel<strong>de</strong>d results in the <strong>regio</strong>n of Helsinki. As time passed, in spite of theefforts of the authorities for the homogenisation of the population re<strong>al</strong>ityindicated that as one advanced further to the West of the town – where theTechnic<strong>al</strong> University of Helsinki is located (the top university in Finland) –there was a growth in the number of inhabitants with a high level ofeducation (aca<strong>de</strong>mic and post-aca<strong>de</strong>mic <strong>studies</strong>). This trend is <strong>al</strong>so seen inEspoo, a suburb in the West of the town of Helsinki. The urban differences(an<strong>al</strong>ysed in <strong>de</strong>pth by the authors in relation to other criteria as well) went<strong>de</strong>eper in the ’90. This <strong>de</strong>gradation of the spati<strong>al</strong> b<strong>al</strong>ance from the socioeconomicstandpoint in the <strong>regio</strong>n of Helsinki un<strong>de</strong>rwent the followingstages, according to the authors:- the beginning of the ’90, with early symptoms;- the new economic growth, following the <strong>de</strong>velopment of thetelecommunications and business service sectors. In addition, the Westernpart of the area around Ruoholahti, with the new headquarters of the Nokia27

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759Vaattovaara and Matti Kortteinen believe that „polarisation” is not the mosta<strong>de</strong>quate concept to be sued in their an<strong>al</strong>ysis. Thus, the an<strong>al</strong>ysis of the newurban differences in the Helsinki <strong>regio</strong>n pointed to the way in which the<strong>de</strong>velopment of the ITC can become a ch<strong>al</strong>lenge for the very equ<strong>al</strong>itycharacteristic of the „Nordic welfare regime”. The i<strong>de</strong>ntified bi-mod<strong>al</strong> urbandifferentiation is not interpreted by Mari Vaattovaara and Matti Kortteinenas a sign of „polarisation” but rather as a new phase in the economic<strong>de</strong>velopment and more exactly in the evolution of the labour force structure.The authors pinpoint to the following: „there is an over-supply of lessskilledlabour force and, at the same time, an over <strong>de</strong>mand for highly skilledIT –work”. At the same time, we <strong>al</strong>so witness a modification in the <strong>de</strong>mandof labour force in favour of those with high-level work abilities. Accordingto the <strong>de</strong>mographic <strong>studies</strong> people that do not work and who live on thesoci<strong>al</strong> benefits are ol<strong>de</strong>r than „the working population on an average”,nearing rapidly the pension age. Un<strong>de</strong>r these circumstances, the labourforce is expected to change in favour of those that are highly skilled,therefore, towards „profession<strong>al</strong>isation”, as suggested by Hamett, as well. Inconclusion, Mari Vaattovaara and Matti Kortteinen believe that the Helsinkidistrict goes through a bi-mod<strong>al</strong> change both in the spati<strong>al</strong> structure and thesoci<strong>al</strong> structure of the town but, by and large, there is a „unimod<strong>al</strong>”ten<strong>de</strong>ncy of <strong>de</strong>velopment in which the „welfare state” and the town aretrying to meet the requirements of the market. Mari Vaattovaara and MattiKortteinen conclu<strong>de</strong> their paper by expressing concern however for „theFinnish mo<strong>de</strong>l of information society”.The paper “Beyond polarisation versus profession<strong>al</strong>isation? A casestudy on the <strong>de</strong>velopment of the Helsinki <strong>regio</strong>n” enjoyed a wi<strong>de</strong>appreciation among speci<strong>al</strong>ists contributing to the attempts of loc<strong>al</strong>authorities but <strong>al</strong>so of the politic<strong>al</strong> <strong>de</strong>cision-makers of maintaining the statusgained at a European and internation<strong>al</strong> level of “the Finnish pocket-sizemetropolis”.At the end of this review I would like to mention that I am glad Ihave had the opportunity of knowing person<strong>al</strong>ly one of the authors MattiKortteinen, on the occasion of a visit to Helsinki University.I thank both authors for giving me the opportunity to present theirpaper in “Public Admin<strong>istratio</strong>n and Region<strong>al</strong> Studies” and I wish themgood luck in their pedagogic<strong>al</strong> and research activity.29

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759FORECASTS ON THE EVOLUTIONS OF THE MAINAGGREGATES OF THE PUBLIC PENSION SYSTEM GIVEN THEPASSING OF THE ROMANIAN ECONOMY FROM THESTATUTE OF “TRANSITION ECONOMY” TO THAT OFMARKET ECONOMY – NECESSITY, CARRYING OUT ANDIMMEDIATE EFFECTSLect.Phd. Georgeta Modiga 5Danubius University from G<strong>al</strong>ati, RomaniaAbstractDuring the last <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong> of the 20 th century, mo<strong>de</strong>lling the macro-economicevolutions and implicitly mo<strong>de</strong>lling the evolutions in the soci<strong>al</strong> insurance systems,including especi<strong>al</strong>ly the pension systems, gained a very strong “anchor”, which <strong>al</strong>lowed and<strong>al</strong>lows at present the re<strong>al</strong>ization of multiple evolution scenarios, with a pretty big probabilityof achievement. This anchor, or better said this anchor-variable is the “inflation rate”,usu<strong>al</strong>ly c<strong>al</strong>culated as the consumption price in<strong>de</strong>x, respectively as its percentage variationfrom one period of time to another.The last <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s of the 20 th century and the first five years of the 21 st century werecharacterised by an extremely accelerated rhythm of innovation, as well as by an accelerationand a multiplication of capit<strong>al</strong> flows, which practic<strong>al</strong>ly led to the phenomenon known as“economy glob<strong>al</strong>isation” or simply as “glob<strong>al</strong>isation”, as it exten<strong>de</strong>d outsi<strong>de</strong> the economic<strong>al</strong>sphere towards <strong>al</strong>l the spheres and sectors of the soci<strong>al</strong> life.This process has been accelerated by the “transition from plan to market” of theeconomies from Centr<strong>al</strong> and Eastern Europe, as a consequence of the f<strong>al</strong>l of the tot<strong>al</strong>itariancommunist system, which dominated this part of Europe for h<strong>al</strong>f a century, and of the end ofthe era known as “the Cold War”. The economic glob<strong>al</strong>isation movement, together with thetransition from plan to markets as well as with China’s entering the internation<strong>al</strong> economiccircuits, increased enormously the investment possibilities and thus the possibilities ofplacing the capit<strong>al</strong> accumulated in the western countries during the autarchy period whichcharacterised the Cold War era.1. The theoretic<strong>al</strong>-methodologic<strong>al</strong> basis of the mo<strong>de</strong>l of macro-economicforecast, of labour market and population – MITGEMDuring the last <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong> of the 20 th century, mo<strong>de</strong>lling the macroeconomicevolutions and implicitly mo<strong>de</strong>lling the evolutions in the soci<strong>al</strong>insurance systems, including especi<strong>al</strong>ly the pension systems, gained a very5 Georgeta MODIGA, Director Executiv <strong>al</strong> Casei Ju<strong>de</strong>tene <strong>de</strong> Pensii G<strong>al</strong>ati, str. Stiinteinr.97, tel. 0236416585, Lect.univ.dr. la <strong>Facultatea</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Drept</strong>, Univ. »DANUBIUS » dinG<strong>al</strong>ati, e-mail: georgeta.modiga@yahoo.com30

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759strong “anchor”, which <strong>al</strong>lowed and <strong>al</strong>lows at present the re<strong>al</strong>ization ofmultiple evolution scenarios, with a pretty big probability of achievement.This anchor, or better said this anchor-variable is the “inflation rate”,usu<strong>al</strong>ly c<strong>al</strong>culated as the consumption price in<strong>de</strong>x, respectively as itspercentage variation from one period of time to another.This anchoring in a key macro-economic variable is nothing but theexpression of the substantiation of the macro-economic mo<strong>de</strong>ls and of thoseaiming towards mo<strong>de</strong>lling the evolution of the variables connected to thesoci<strong>al</strong> insurance systems, on what we could c<strong>al</strong>l “a function ofpredictability”. The price, given its qu<strong>al</strong>ity of “fundament<strong>al</strong> economicinformation” or information about attributes as it is named in the theoryspecific to the information economy, plays a fundament<strong>al</strong> role as marketsign<strong>al</strong>, guiding the <strong>de</strong>mand and the offer flows. From this point of view, theprices stability, or better said the prices evolution stability or predictability,the non-accelerated character of their evolution, expressed through the nonacceleratedcharacter of the inflation rate, gener<strong>al</strong>ly give a predictabilitycharacter to the economic evolutions, thus encouraging the movement of thecapit<strong>al</strong> flows, the medium and long term investments and especi<strong>al</strong>ly theinnovation, as progress engine. Or, the last <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s of the 20 th century andthe first five years of the 21 st century were characterised by an extremelyaccelerated rhythm of innovation, as well as by an acceleration and amultiplication of capit<strong>al</strong> flows, which practic<strong>al</strong>ly led to the phenomenonknown as “economy glob<strong>al</strong>isation” or simply as “glob<strong>al</strong>isation”, as itexten<strong>de</strong>d outsi<strong>de</strong> the economic<strong>al</strong> sphere towards <strong>al</strong>l the spheres and sectorsof the soci<strong>al</strong> life.This process has been accelerated by the “transition from plan tomarket” of the economies from Centr<strong>al</strong> and Eastern Europe, as aconsequence of the f<strong>al</strong>l of the tot<strong>al</strong>itarian communist system, whichdominated this part of Europe for h<strong>al</strong>f a century and of the end of the eraknown as “the Cold War”. The economic glob<strong>al</strong>isation movement, togetherwith the transition from plan to markets as well as with China’s entering theinternation<strong>al</strong> economic circuits, increased enormously the investmentpossibilities and thus the possibilities of placing the capit<strong>al</strong> accumulated inthe western countries during the autarchy period which characterised theCold War era. The western capit<strong>al</strong> placement in countries with an abundantproduction factor supply and the labour (work force) created the premisesof an unprece<strong>de</strong>nted growth of the goods and services offer, in conditions ofhigh productivity, granted by the mo<strong>de</strong>rn technologies, but <strong>al</strong>so at very lowprices, given the low costs of using the labour factor in countries where theoffer for this production factor is, as we said, extremely abundant (both31

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759China and the countries in Centr<strong>al</strong> and Eastern Europe as well as countriesfrom the former Soviet Union), which resulted in very low wages comparedto those in the western countries. This growth of the output volume, giventhe conditions where the glob<strong>al</strong> <strong>de</strong>mand rose, should lead to a gener<strong>al</strong> pricegrowth, and thus to a rise of the inflation rate level, un<strong>de</strong>r “classic”conditions, as well as un<strong>de</strong>r conditions of relative “autarchy”. But if thisvery big <strong>de</strong>mand, in continuous expansion of goods and services more andmore varied, is fueled by an ultra-abundant offer, due to the technologies<strong>al</strong>lowing the mass production of a very large number of goods and services,at lower and lower prices, given on the one hand the fierce competitionbetween the producers situated now in a market with glob<strong>al</strong> opening, andon the other hand the possibilities of producing these goods and services ineconomies where labour factor costs represent only a fraction of the workforce costs in the western countries, <strong>al</strong>l this makes prices of the main goodsand services categories practic<strong>al</strong>ly register a <strong>de</strong>creasing dynamics. Theproduce that was consi<strong>de</strong>red a few years ago as the attribute of the elitebecame a consumption good accesible to practic<strong>al</strong>ly a huge mass ofconsumers. Because of this fact, not even the price rise of basic raw materi<strong>al</strong>s(oil, natur<strong>al</strong> gas, and iron ore) in the last years could stop the glob<strong>al</strong>economic growth or lead to an “overheating” of the main world economies,or in other words, lead to a growth of the inflation pressures, on thecontrary, certain economies even confrunted the “<strong>de</strong>flation” phenomenon.The solidity of the inflationary anchor was <strong>al</strong>so consolidated by thefact that the Centr<strong>al</strong> Banks gained, starting with the 1980s, in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncefrom the Governments of the respective countries, which <strong>al</strong>lowed them topursue their own policies, through specific instruments, respectivelythrough controlling the circulating monetary mass, as well as throughcontrolling the reference interest rates. This led to the creation of a gener<strong>al</strong>perception of predictability of the glob<strong>al</strong> business and economicenvironment.All these reasons linked to the macro-economic evolutions at glob<strong>al</strong>level justify the use of the inflation rate as anchor variable of the macroeconomicmo<strong>de</strong>lling processes.At the same time, the economic predictability, from the pricevariation point of view, justifies the use of the inflation rate as anchorvariable <strong>al</strong>so in the mo<strong>de</strong>lling of the processes and evolutions in the sphereof the soci<strong>al</strong> insurance system and especi<strong>al</strong>ly in the sphere of the pensionsystems, no matter their philosophy. This is because the predictability givesthe companies, the housekeepings, the Governments and the Pension Fundsthe possibility to plan both the economising processes and especi<strong>al</strong>ly the32

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759long term investment processes. The price variation predictability as<strong>de</strong>terminont for the economic predictability, offers the possibility ofdiversifying the pension insurance, from the PAYG-type classic system tothe systems based on individu<strong>al</strong> economising or accumulation. Thishappens because both the contributions and the benefits can be betterpredicted on long term, gener<strong>al</strong> interv<strong>al</strong>s. Both the beneficiaries and thecollective placement organisms (the pension funds) can project theirfinanci<strong>al</strong> assets portfolios as to maximise the benefits and to minimise therisks on much longer time interv<strong>al</strong>s. At the same time, the glob<strong>al</strong>isationgives the collective placement organisms the possibility to compensate theirrisk “exposure” (leverage) through a “hedging” as broad as possible an<strong>de</strong>ven to obtain supplementary profits from trading the “leverage” and the“hedging” portfolios as in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nt assets. This abundance of optionsregarding the possibilities of capit<strong>al</strong> placement, and especi<strong>al</strong>ly the existenceof an abundance of insurance and “risk placement” options contributes tothe draw of new capit<strong>al</strong>s in the market circuit, and thus to the increase of theabundance of the capit<strong>al</strong> production factor offer, another elementcontributing itself to the glob<strong>al</strong> maintenance of a non-inflationist climate,which constitutes an important premise for diversifying placements in or<strong>de</strong>rto obtain in the end pension insurances.At the same time though, the abundance of the capit<strong>al</strong> factor <strong>al</strong>soleads to a significant <strong>de</strong>crease of the earnings obtained through capit<strong>al</strong>placements. So, it is necessary to have a portfolio management as active aspossible, and especi<strong>al</strong>ly, on short term, a leverage as broad as possible,covered by a hedging as diverse as possible and with market <strong>de</strong>pth(hedging to hedging practic<strong>al</strong>ly) in or<strong>de</strong>r to ensure truly positive benefitsfrom capit<strong>al</strong> placement. This mechanism works <strong>al</strong>so with the pension funds,which slowly have to diversify their portfolios as much as possible and topractice aggresive “leverage”, even a risky one, in or<strong>de</strong>r to be able to offertheir clients, at the maturity of their placements, the pension insurancesin<strong>de</strong>ed able to ensure them an old age free of poverty.All this means that practic<strong>al</strong>ly, the price stability creates both risksand opportunities. If stability gives the possibility to make long terminvestment and economising <strong>de</strong>cisions, it <strong>al</strong>so means abundance of capit<strong>al</strong>sand placement possibilities, the competition between different actors on thecapit<strong>al</strong> markets and the reduction of earnings from capit<strong>al</strong> placements. Inother words, the pension funds and the individu<strong>al</strong>s, the housekeepings andthe companies will have to enlarge their market exposure <strong>de</strong>gree, bydiversifying their placements, at the same time with the sofistication of thehedging or the risk insurance mod<strong>al</strong>ities that come with the enlargement,33

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759the expansion of the leverage. Practic<strong>al</strong>ly, the price stability makes thepensions that can be obtained through a single long term capit<strong>al</strong> placement(respectively through the participation to the <strong>public</strong> pension system or to asingle private pension system) lose touch with the wage income, or in otherwords, reduce continuously the replacement rate c<strong>al</strong>culated according to thewage income, respectively to the medium wage, as happens with theconvention<strong>al</strong> reporting. This happens because the wages grow not only bytaking into account the gener<strong>al</strong> price rise (the inflation rate) but <strong>al</strong>soaccording to a fraction of the productivity growth which inherently mustreflect <strong>al</strong>so on the labour factor; while pensions usu<strong>al</strong>ly have <strong>al</strong>most noconnection to the productivity growth, being practic<strong>al</strong>ly correlated with theinflation rate, thus with the price and the tariff rise. Since the latter hassm<strong>al</strong>ler and sm<strong>al</strong>ler variations (the effect of predicatbility in the conditionsof a glob<strong>al</strong>ised economy), pensions grow from one period to another insm<strong>al</strong>ler and sm<strong>al</strong>ler proportions, which makes them lose touch with thewage earnings and not be able to ensure the individu<strong>al</strong>, after retiring fromactivity, an income and implicitely a standard of living comparable to theone before retiring. The connection between the inflation rate evolution andthe pension in<strong>de</strong>xation mechanism, or the rise of their re<strong>al</strong> and nomin<strong>al</strong>v<strong>al</strong>ue so that it can ensure the pensioner a <strong>de</strong>cent living, leads to, inconditions of low inflation, the absolute necessity to diversify theplacements in or<strong>de</strong>r to obtain pension insurances, or in other words toobtain pensions, in or<strong>de</strong>r to keep thus the connection between the wageearning and implicitely the standard of living before retiring and thestandard of living after retiring, thus preventing the individu<strong>al</strong>s and thehousekeepings from becoming poor after retiring from the active living nomatter how late it might take place, mainly because of the increase of thepensioning age as a consequence of the <strong>de</strong>mographic pressure (the aging ofthe population as a consequence of the rise of the life expectancy at birthand <strong>al</strong>so of the rise in the weight of the persons of age in the tot<strong>al</strong>population, enhanced by the nat<strong>al</strong>ity <strong>de</strong>crease).On the other hand, given the capit<strong>al</strong> factor abun<strong>de</strong>ncy, the benefitsthat different placements can produce become sm<strong>al</strong>ler and sm<strong>al</strong>ler. Tomaximise them, it is necessary to create sc<strong>al</strong>e economies and purposeeconomies, as far as the investment and the economising processes areconcerned. So there appears the necessity for each individu<strong>al</strong> and eachhousekeeping to diversify his own leverage, in the conditions of ana<strong>de</strong>quate hedging of course, in or<strong>de</strong>r to be able to thus ensure the continuityof his living standard after retiring. In other words, in conditions of pricestability – reduced inflation - enhanced by the abundance of capit<strong>al</strong>s and34

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759placement possibilities, so in the conditions of lower and lower interestrates, another effect of a non-inflationist economic climate, of some reducedunitary earnings from capit<strong>al</strong> placements, the key to maintain someconsistent replacement rates able to maintain the living standard ofindividu<strong>al</strong>s and housekeepings after retiring, at comparable levels to thosebefore retiring, is both the diversifying (the “purpose” increase) of the capit<strong>al</strong>placements, and especi<strong>al</strong>ly the growth of the capit<strong>al</strong> placements volume (the“sc<strong>al</strong>e” increase). This only points out the necessity for individu<strong>al</strong>s toeconomise more and to invest as much as possible from this economisinginto assets which can be converted into pensions at the anticipated momentof retiring from activity. Hence the necessity of the <strong>al</strong>ternative pensionsystems, including those of occupation<strong>al</strong>, sectori<strong>al</strong>, or branch type or thoseaccording to the anglo-saxon mo<strong>de</strong>l, the enterprise/company/corporationtype.Starting from these reasons, it is obvious, we believe, that the wholemo<strong>de</strong>lling exercise we propose and which will have as purpose to explainthe necessity of the occupation<strong>al</strong> pension funds and in gener<strong>al</strong> of thepension systems <strong>al</strong>ternative to the PAYG in Romania, uses as an exogen,explanatory variable the inflation rate, as it is expressed, even in animperfect manner, by the annu<strong>al</strong> percentage variations (current <strong>de</strong>cember tolast <strong>de</strong>cember) of the consumption prices in<strong>de</strong>x (IPC/CPI%).2. The impact of the integration in the European Union on theevolutions of the macro-economic variables with influence on the pensionfunds profitablenessThe main macro-economic variables influencing the evolution of theoccupation<strong>al</strong> pension funds profitableness, must be forecast in their shortterm evolution, respectively for the next ten years, and must be <strong>de</strong>signed onlong term, respectively until 2030-2040, so that we can inclu<strong>de</strong> thepopulation evolution and the macro-economic evolutions that influence theprofitableness of the pension funds placements, placements which usu<strong>al</strong>lyhave a long maturing term (if the occupation<strong>al</strong> pension funds were createdfor example this year, the first payments wouldn’t take place sooner than 15years from now, in other words, the investments ma<strong>de</strong> by these funds musthave in view mainly a long term profitableness and speculative earnings asin the case of the ordinary investment funds.In consequence, we will proceed in this subchapter to the forecast of16 macro-economic variables whose later evolutions will influence theevolutions of the occupation<strong>al</strong> pension funds profitableness as well as the35

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759population evolutions and, from this point of view, of the basis of insuredpersons.The variables whose evolution will be forecast and an<strong>al</strong>ysed incorrelation with the evolution implications on the occupation<strong>al</strong> pensionfunds profitableness cover the following problematic<strong>al</strong> areas:• the gener<strong>al</strong> economic <strong>de</strong>velopment and the <strong>de</strong>velopment of thecommerci<strong>al</strong> exchanges;• the labour market evolutions (wages, occupancy, unemployment);• the evolutions in the living standards (poverty, income inequ<strong>al</strong>ity,RIP/inhabitant)In consequece, the list of variables inclu<strong>de</strong>d in the forecast exercise isthe following:• the nomin<strong>al</strong> RIP in billion USD;• the RIP annu<strong>al</strong> percentage variation (RIP%), <strong>al</strong>so known as economicgrowth;• the annu<strong>al</strong> percentage variation of the consumption prices in<strong>de</strong>x (theinflation rate-CPI%);• the liber<strong>al</strong>ization in<strong>de</strong>x (LibIdx) until reaching the cumulative v<strong>al</strong>ueof 10;• the Stability in<strong>de</strong>x (StbIdx);• the wages share in the tot<strong>al</strong> of the available income (%);• the work productivity expressed as RIP/occupied person;• the occupied population (occupancy), expressed in millions ofoccupied persons;• the unemployment rate (BIM);• the raw medium wage in USD;• the medium pension in USD;• the share of the occupied population in agriculture (the agricultur<strong>al</strong>occupancy) in the tot<strong>al</strong>ity of the occupied population (%);• the openess to tra<strong>de</strong> (OT, c<strong>al</strong>culated as the percentage ratio betweenthe sum of exports and imports in mld USD and the nomin<strong>al</strong> RIP expressed<strong>al</strong>so in billion USD);• the poverty rate, c<strong>al</strong>culated, as share of the whole country’spopulation, of the people un<strong>de</strong>r the 50% threshold of the medium income;• the income inequ<strong>al</strong>ity (the Gini In<strong>de</strong>x).As an anchor explanatory variable for the forecast until 2014 as wellas for the ulterior projections until 2029, we took the inflation rate or theannu<strong>al</strong> percentage variation of the consumption prices in<strong>de</strong>x. Its v<strong>al</strong>ueswere established in a normative manner, taking into account the36

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION & REGIONAL STUDIES1 st Year, No. 2 – 2008G<strong>al</strong>ati University Press, ISSN 2065 -1759parameter’s importance, which had been justified in the previous chapter.So the forecasts ma<strong>de</strong> us take into account this explanatory variable startedfrom the objective of a annu<strong>al</strong> medium inflation rate that had to be around2,7-2,9% for the year 2013-14, a year consi<strong>de</strong>red by us as the most probableand feasible for Romania’s entering the Euro zone and its implicit adhesionto the Stability Pact rules, assuming of course they remain the same, at leastin gener<strong>al</strong> terms, until the respective time. Then, until 2029, a year when thefirst business cycle manifests itself, the inflation rate has been kept as anchorvariable, taking into account the fact that the stability in prices is a <strong>de</strong>mandof the Stability Pact on the one hand, and on the other hand taking intoaccount the fact that a market economy in the incipient stage (an emergentmarket) as Romania will be consi<strong>de</strong>red until that time, including from thepoint of view of the capit<strong>al</strong> flows and markets, maintaining the pricestability as a guarantee of the evolutions predictability in the businessenvironment and especi<strong>al</strong>ly as a precondition of a continuous andaccelerated economic growth, will be essenti<strong>al</strong> for drawing and stimulatinginvestors, both the direct ones and the portfolios ones. After this date, theanchor explanatory variable changes, the role of the inflation rate beingtaken over by the economic growth, which is used in this capacity for theprojections until the year 2040.We must <strong>al</strong>so mention that the evolutions of the inflation rate in itscapacity of anchor variable for the forecast until 2014 are taken intoconsi<strong>de</strong>ration only after reaching the critic<strong>al</strong> transition mass, so starting with1999, consi<strong>de</strong>ring that between 1997-1998 the “critic<strong>al</strong> mass” was reachedand overcome, on the liber<strong>al</strong>isation in<strong>de</strong>x sc<strong>al</strong>e (moreover the series for thisvariable stop in 2004, when v<strong>al</strong>ue 10 is reached – “the end of thetransition”). In this approach we start from the consi<strong>de</strong>rations ma<strong>de</strong> in theprevious chapter, according to which the evolutions before reaching thecritic<strong>al</strong> mass, specific <strong>al</strong>most exclusively to the transition from plan tomarket, are practic<strong>al</strong>ly impossible to repeat and in consequence can’t betaken into consi<strong>de</strong>ration for a forecast and especi<strong>al</strong>ly for the anchorexplanatory variable (it is hard to believe the inflation rate will reach againv<strong>al</strong>ues of 155%). The evolutions of the inflation rate, in its capacity of anchorexplanatory variable, manage to forecast pretty accurately the evolutions of<strong>al</strong>l the macro variables enumerated in the list in this paragraph, thusactu<strong>al</strong>ly un<strong>de</strong>rlining the importance of the stability in prices, as a guaranteeof the economic and implicitely the soci<strong>al</strong> progress, in the conditions inwhich, of course, these prices are established through competitionmechanisms and in which they are strengthened through a monetarypru<strong>de</strong>nti<strong>al</strong>ity of the Centr<strong>al</strong> Bank. The only two variables whose evolutions37