Robert Richard Thornton - Voice For The Defense Online

Robert Richard Thornton - Voice For The Defense Online

Robert Richard Thornton - Voice For The Defense Online

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

-the Texas (<strong>Robert</strong> <strong>Richard</strong> <strong>Thornton</strong>EBRUARY 1987

JOURNAL OF THE TEXAS CRIMINALDEFENSE LAWYERS ASSOCIATIONVOICEfor rite <strong>Defense</strong> USSN 0361-2232) ispublished monthly by the Texas Criminal<strong>Defense</strong> Lawyen Association, 600 W. 13th,Austin, Texas78701, (512) 478-2514. Annualsubscription rate for members of thc associationis $24, which is included in dues. Secondclass pastage paid at Austin, Texas. POST-MASTER: Send address changes to VOICEforrheDefeiue, 6M) W. 13th. Austin, Texas 78701.All articles and othcr editorial contributionsshould be addressed to theeditor, Keny P. Atz-Gerald, 1509Main St., Suite7W, Dallas, Texas75201. Advertising inquiries and contracts sen1to Allen Carnally, Artfom, I=., 6201 Guadalupe,Austin, Texas 78752 (512) 451-3588.OFFICERSPresidentKnox JonesMcAllenPresident-ElectCharles D. BullsSan AntonioFirst Vice PresidentEdward A. Mallet1HoustonSeeond Vice PresidentJ. A. "Jim" BoboOdessaSecretary-TreasurerTim Evans<strong>For</strong>t WorthAssistant Secretary-Treasurrr<strong>Richard</strong> A. AndersonDallasEdilor, VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong>Kerry P. FitzGeraldDallasEdilar, Significant Dceisions ReportCatherine Greene BurnettHoustonExecutive DirectorJohn C. BostonOmre ManagerNanee Nelle"I987 TEXAS CRIMINAL DEFENSELAWYERS ASSOCIATIONFEBRUARY 1987 VOL. 16, NO. 8FEATURE ARTICLES5 <strong>The</strong> Effective and Judicious Use ofOral Argument in the Court of CriminalAppealsby Judge Charles F. Catnpbell, Jr.and John M. Bradley9 Federal Sentencing in the 1980s andBeyond-Part Iby Alan Ellis18 Aliens as Criminal Defendants:Strategies to Avoid Adverse ImmigrationConsequencesby Alan Vonmcka24 Search Warrants and Arrest Warrantsby Jade Meeke,; assisted by SusartGogganCOLUMNS3 President's Reportby Knox JonesSDR1-12 Significant DecisionsReport34 DWI Practice Gemsby J. Gary Trichter37 Evidence: Clarity andVitalityb)! Geofley A.FitzGerdd40 From the Inside Outby WI~. T. HabernNEWS17 Index to Advertisers47 New Motions43 <strong>The</strong> Investigatorb)~ Jack Murray45 Ethicsby Pro$ Wnlter Steele, Jr.50 Jury Selection-<strong>The</strong> <strong>Voice</strong> Listensby <strong>Robert</strong> B. Himchhorn54 A View from the Benchby Judge Lnny Gist56 <strong>The</strong> Last Wordby Jack V. Strickland59 In and Around Texasby John Boston53 Letters59 Lawyer's Assistance CommitteePAST PRESIDENTSClifford W. ~rohn. ~ubbock (1982-83)Charles M. McDonald, Wac0 (1981-82) Phil Burteson, Dallas (197314)<strong>Robert</strong> D. Jonw. Austin (1980-81) C. Anthony Frilow, Jr., Hourton (1972-73)Vincent Walker Perini. Dallas (1919-80)Gmrge F. Luquene, Houston (1978-79)Frank Maloney, Auxin (1971-72)DIRECmRsDavid R. BiresHoustonWilliam A. Bratton 111DallasCharles L. CapenonDallasJoseph A. Connora 111McAllcnDick M. DcGuerinHourtonBuddy hl. DickenShermanBob ErtradaWichita FallsCarolyn Clause GarciaHoustonGerald H. GoldnteinSan AntonioBill HabemSugar landJeremiah HandySan AnlonioMerrilec L. HarmonWac0Joseph C. 'Lum" Ha\\lhomBeaunwnlHarry R. HeardIanevicwDallasJeffrey HinkfeyMidlandPrank JacksonDallasJeff KearneyFon worthJames H. KreimeycrBeltonJohn LinebargerPort WorthEdear - A. Maw"DallasArch C. hlcColl 111DallasE. G. "Gerry" MorrisAuxinJack 1. RawitscherHoultanGeorge ScharmenSan Antoniohlark StcvcnrSan Anlonio<strong>Richard</strong> <strong>Thornton</strong>GalveslonJ. Douglas Tinkercorps Chris6Stanley I. WeinbergDallasSheldon WeisfeldBrownrvilleDain P. WhitwonhAustinBill WisrhkaemperLubbockRoberl 1. YlaguirrehlcAllenASSOCIATEDIRErnRSDavid L. BotsfordAustinRonald GuyerSan AntonioMark C. HallLubbockChuck LaneharlLubbockhl. Mark LesherTuarkrnaLynn Wadc MatoneWac0Glenn A. PerryIangviewGeorge RolandhlcKinncyKent Alan SchafferHouslonDavid A. SheppardAustinWilliam B. SmithMidlandRandy TaylorDallas

PRESIDENT'S REPORTIKnox JonesIt's won derh 11 to be living in an age of"less-intrusive government.'~ust knowingthat Big Brother is not looking over yourshoulder and that the unfettered exerciseof free enterprise remains unhampered iscomforting. <strong>The</strong> problem is, however, thatgovernment intrusion can exist outside themarket place.It seems that lately, any diminution ofregulations in our marketplace have beenoutweighed by intrusions into the most privateaspects of our everyday lives. <strong>The</strong>sepot shots at the Constitution historically beginwith sn~all caliber assaults on the politicallypowerless, e.g., the wiretappingprovisions of the 1969 Omnibus CrimeControl Act, directed against the "criminalelement." But by the mid-1980's. wesee the shotgun approach utilized to thepoint that many defense attorneys are concernedabout the sanctity of not only theirtelephone, but their offices as well.We live in a star wars world. <strong>The</strong>government now has the ability and thelicense to be all-pervasive in its quest forinformation about where we go, what wesay and what we do. <strong>The</strong> quality of life inour supposedly free society will bediminished unless the courts recognize anddefine the limits of permissible governmentintrusron.Until recently, abuse of power by thegovernment has been relatively unchecked.Denial of bail, loss t ~f presumption of innocence,coutenance of police subtrafizgeand "good faith" violations of the FourthAmendment lead the way towards increased"law and order" and decreased fundamentalliberty. Our courts are finallybeginning to rediscover that allowing thegovernment to usurp fundamental libertyevenwhen citizens accused of crime arethe initial targets-invites the governmentto seize that initiative. <strong>The</strong> result can leadto the kind of government intrusions whichnow confront the federal bench.Imagine yourself sitting as a UnitedStates District Judge. <strong>The</strong>attorney for theUnited States govenunent tells you that anyfederal employee who seeks a promotioowaives his constitutional right to object toa drug test and must submit to a samplingof his or her urine. Notwithstanding theprotests of government counsel and the imminenceof an appeal, your ruling is asfollows:(1) <strong>The</strong> mandatory collection of urinesamples constitutes a search even more intrusivethan a search of a home.(2) Urinanalysis testing, coupled with apre-test form (to be filled out by the persontested as per government mandate)amounts to involuntary self-incrimination.(3) <strong>The</strong> presence of an observer whilea "subject" performs excretory functions isa "gross invasion of privacy"-"a degradingprocedure that so detracts from humandignity and self-respect that it shocks theconscience and offends fhis court's senseof justice."<strong>The</strong>se were the words of a federal judgesitting in the Eastern District of Louisiana.<strong>The</strong> defendant was the United States CustomService. <strong>The</strong> complaintant was theNational Treasury Employees Union. NationalDeaswy Enployees Union V. VonRabb, U.S.D.C. E. La. No. 86-3522,11/14/86; 40 CRL 2182.Now who the hell made it necessary fora Federal District Judge to rule that wehave a reasonable expectation of privacyin our urine (and cite authority)? Was heillogical in his dicta that if carried to itslogical extreme, those who wished to rideupon federal highways must consent tohaving their urine tested?I asked my wife to help me think of asuitable ending to this diatribe. She mumbledthat either we ought to be thankful forcourageous and perceptive federal judges-or a constitution that gives us our systemof checks and balances-or both. NOWand then she mumbles the right thing. Sonow and then I take a few notes. WFebruary 1987 1 VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> 3

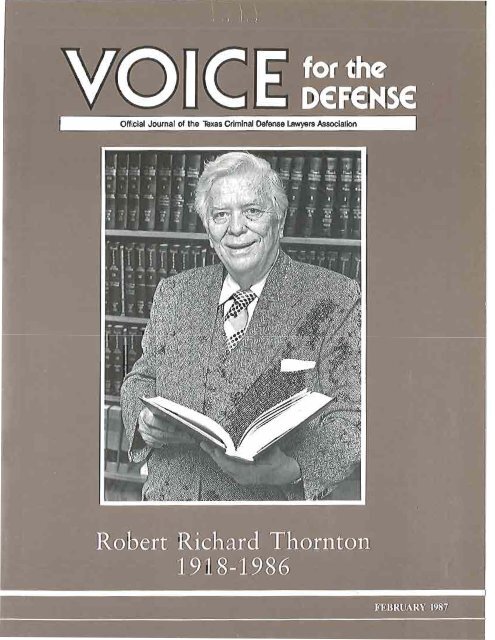

Memorial<strong>Robert</strong> <strong>Richard</strong> <strong>Thornton</strong>by John Boston<strong>The</strong> Texas Criminal <strong>Defense</strong> LawyersAssociation has lost one of its originals.Charter member <strong>Robert</strong> <strong>Richard</strong> <strong>Thornton</strong>,68, of Galveston died December 26, 1986after a brief illness. He had been a lawyersince 1947, having begun his legal educationin 1939. From 1940 through 1946 hewas on active duty with the United StatesArmy Air Corps.A native of Houston, <strong>Richard</strong> was bornJuly 12, 1918, attended Galveston publicschools and was an honor graduate of BallHigh School in 1935. He attended TulaneUniversity in New Orleans, the Universityof Texas at Austin (BA 1939), the Universityof Texas School of Law receiving anLLB degree in 1948. Like many of hisgeneration his education was interruptedby World War 11.Colonel <strong>Richard</strong> <strong>Thornton</strong> United StatesAir <strong>For</strong>ce Reserve (Retired) had a distinguishedmilitary career, both active dutyand Air <strong>For</strong>ce Reserve. He served in boththe Pacific and European theaters duringWorld War TI. He survived the ditching ofhis B-17 near New Guinea in the South Pacificin November 1942. He and his crewspent four days in life rafts in sbarkinfestedseas before they were rescued. InMarch 1943 he was transferred to the Europeantheater where the then Captain<strong>Thornton</strong> flew thirteen bombing missionsover Europe. On this thirteenth mission hewas shot down over France, parachuted tosafety and for some period of time evadedcapture with the aid of the Free French.He was captured near the French-Spanishborder by the Ciestapo in 1944. He wasliberated by the Russians in May 1945 andleft active duty as a Major, continuing inthe United States Air <strong>For</strong>ce Reserve andretiring as a Reserve Colonel in 1965. Hisdecorations include the Silver Star, DistinguishedFlying Cross with oak leaf cluster,Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters andvarious campaign medals from both thePacific and European theaters. He was amember of the National Ex-Prisoner ofWar Association, the Veterans of <strong>For</strong>eignWars and the American Legion.<strong>Richard</strong> <strong>Thornton</strong> was admitted to practicein the State of Texas in 1947; UnitedStates Supreme Court in 1953. He was admittedto practice before various othercourt and commissions throughout hiscareer including three of the Federal DistrictCourts of Texas, Immigration Appeals,Interstate Commerce Commission,United States Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuitand the US. Court of Military Appeals.In addition to being a chartermember of TCDLA, he was a member ofthe American Trial Lawyers Association,Texas Trial Lawyers Association, GalvestonCounty Bar Association, havingserved as a member of the hoard or as anofficer of the latter two orgenizations. Hewas amemher of theNational Associationof Criminal <strong>Defense</strong> Lawyers.<strong>Thornton</strong> was very active in continuinglegal education programs including thefaculty of the Texas Trial Advocacy Institute,Sam Houston University; Lecturer,Criminal Law and Procedure Section StateBar of Texas; Adjunct Professor, CriminalLaw and Procedure, Trial Tactics,University of Houston Bates College ofLaw; and Southwest College of Law. Inthe past he has been a lecturer for theCriminal <strong>Defense</strong> Lawyers Project and acontributor of legal articles to the <strong>Voice</strong>fir, the <strong>Defense</strong>.Anoutline of the facts of a forty-year legalcareer in no way does justice to thecontributions that <strong>Richard</strong> <strong>Thornton</strong> madeto the legal profession in general and theTexas Criminal <strong>Defense</strong> Lawyers Associationin particular. <strong>Richard</strong> <strong>Thornton</strong> wasalways available to advise and assist criminaldefense lawyers with tough cases andproblems of any nature. <strong>The</strong> localnewspapers in Galveston County havereferred to him as "prominent." He wasthat and so much more. <strong>Richard</strong> <strong>Thornton</strong>'scontributions to his profession, his stateand his country were many. We willremember him as a first class gentleman,an honorablelawyer and a friend. We willmiss him.WPRIVATE* * CRIME LABORATORY *Prnvlrli~~g Qualily Fnrcnsic Analysisa ~ Expert ~ d l'cslilnony in thc Following Arras :Drug AnalysisBlood Alcohol AnalysisUrine Drug AnalysisAlcohol ToxicologyAnonymous Drug TestingDWI ConsultationClandestine Lab ConsultationAlcohol Absorption/Arson Debris AnalysisElimination CurvePhysical Trace Evidence,Preparation forMurder, Rape, etc.DWI ClientsPrivate Investigationsiz We specialize in preparing defense attorneysfor cross-examination of opposing scient@c experts QInitial consultation is free of chargeMICRO FORENSICS & INVESTIGATIONS1600 hkst Hichwnv 6, Suilc 350Alvin, Texas 77511Houston Area: (7131 331-2655 Austin Area: (512) 445-0190A VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> /February 1987

<strong>The</strong> Effective and Judicious Use ofOral Argument in the Court of Criminal Appealsby Judge Charles F. Campbell, Jr. and John M. BradleyOral argument is the only opportunityfor direct personal contact between appellatejudges and the p+ in a lawsuit.'In that short encaunter, an advocate has theunique opportunity to supplement the writtenword with the spoken word, therebyadding credibility.and emphasis to argumentsthat might otherwise be unremarkable.Knowing that the spoken word c-anhave a significant effect upon the decisionmakingprow, appellate judges have frequentlypublished their thoughts on the artof oral advo~acy.~ <strong>The</strong> purpose of this ar-ticle is to add to those comments by focusingupon improving oral argument in theTexas Court of Criminal Appeals.When Can Counsel RequestOral Argument?Counsel can request oral argument inanv "causes" acce~ted bv the Court of~rknal Appeals for suhhi~ion.~ <strong>The</strong>secauses include direct appeals, cases grantingdiscretionary review, extraordinarymatters and post-conviction writs of habeasco~pus.~ Prior to actual submission of acause, the Clerk of the Court must informcounsel of record that he bas 30 days withinwhich to notify the Court whether oralargument is desired.'C~unsel may not request oral argumentin motions requesting special consideration,e.g., to advance on the docket."Likewise, counsel may not request oral argumentin motions for rehearing or repliesto such motions.' However, if a motionfor rehearing is granted, the Court maypermit oral argument upon resubmissionof the causc8At present, the Court does not screen requestsfor oral argument. If requested, oralargument generally will he granted.Although the rules of appellate procedureindicate that oral argument may be deniedfor rehearings, the court has not indicatedany specific grounds for denying such argument.Nor has it shown any general ten-Charles F. Canlobell is a maduate ofSMU School of &v. He hashen AS&tant Disnict Aftomey in Harris Caunty;County Artonzq and District Altomey inHill County; Assistant Attorney General,Chief of Prosecutor's Assisfance Divisionunder Attorney General Mark While; electedJudae, Tam Court of - Criminal Aweals .-in 192.Mr. Bradley is Judge Campbell'sResearch Assistant. Previously he servedas Briefng Attorney for Judge Campbelland= intem to Harrts Corn District Atfonteykoffice. He graduak fmm theUniversity of St. i'h~homas in 1981 andfromthe llniwrsify of Houston LUW Center in1985.dency to deny argument upon rehearing.Tbese circumstances indicate that theCourt presently has a liberal policy ofgranting requests for oral argument.Some appellate courts have begunscreening requests for oral argument. <strong>The</strong>development of such a policy stems froman increase in frivolous cases, a rise inoverall caseloads and a recognition thatmany cases are governed by dear precedent?Those same policy considerationscould eventually lead to restrictions uponoral argument in the Court of Criminal Appeal~.'~To preserve an independentchoice, attorneys should make selective,intelligent requests for oral argument andthen follow through on that request.When Should CounselRequest Oral Argument?Counsel should request oral argumentwhen he believes that it will significantlyenhance his written brief. <strong>The</strong> opportunityto vocalize the contents of a brief, if usedto engage in mere repetition, is not a soundenough reason for requesting and presentingoral argument. Counsel must analyzehis oarticular case in terms of the obiec- "tives of oral argument and determinewhether there will he any distinct advantagesto supplementing his brief with thespoken word.Each Wednesday, when oral argumentsare presented in the Court of Criminal Appeals,at least one party to a cause typicallyfails to appear." Counsel's absence impliesthat his request for oral argument mayhave been mechanistic rather thanmeaningful. This sort of haphazard approachto appellate advocacy might eventuallylead to curtailment of oral argument.A former state supreme court justice hasidentified ten functions of orat argument:(1) to persuade judges(2) to focus on one important matter only(3) to reiterate most major points in thebrief(4) to clarify facts(5) to counter opposition's arguments(6) to appeal to '$mice," 'kight," and"fairness"(7) to legitimate the legal process by appblic confrontation of issum(8) to urge judges to read (or reread)February 1987 1 VOICE for fhe <strong>Defense</strong> 5

iefs(9) to prepare judges for conferencedeliberations(10) to force judges to cummunicate witheach other.12Counsel should ideally request oral argumentonly when his case provides an opportunityto accomplish a majority of thesefunctions.Some written arguments are simply notenhanced by subsequent oral presentation.<strong>For</strong> exmple, a brief challenging the sufficiencyof the evidence for a given convictionis rarely enhanced by oral argumentand is often inappropriately converted intoa second jury argument." Counsel inevitablyrepeats his version of the lengthyfactual foundation containe'in his brief,making numerous distractive trips to therecord, and predictably concludes that therecord does or does not support the verdict.Opposing counsel generally respondsby pointing to still more facts in the recordsupporting the contrary point of view.Such an extensive facbal dispute is bestleft to the briefs, to be carefully consideredby the Court after submission of the case.On the other hand, oral argument isoften an ideal forum for addressing theconstitutionality of a statute or the applicationof a particular constitutional provision.14<strong>The</strong> resolution of constitutionalissues affects the public generally andshould, therefore, follow public debate. Infact, oral argument of constitutional issueshas become even more necessary becauseof the recently recognized distinctions betweenstateand federal constitutional protection~.'~A complete list of the types of argumentsbest suited to oralpresentation in the Courtof Criminal Appeals is not possible becauseof the many factors that affect eachcase. However, counsel should be able toapply the principles set forth above indeciding whether oral argument wouldbenefit the Court.In making a decision, counsel shouldalso be aware of some institutional proceduresthat inherently limit the impact oforal argument in the Court of Criminal Appeals.First, oral argument is presently notrecorded,16 although a majority of thejudges, along with their briefing attorneys,do take notes. Second, following oral argument,the Clerk of the Court divides thesubmitted cases into nine approximatelyequal "stacks."17 <strong>The</strong> nine "stacks" arethen distributed among the judges bylot.lS No conference discussion of a caseoccurs until an opinion has been draftedand circulated. Third, a significant amountof time may pass between oral argumentand conference discussion of a case. <strong>The</strong>secircumstances may diminish the impactthat an oral argument could have upon theCourt.<strong>The</strong>se limitations, of course, could bepartially alleviated by recording oral argumentandlor holding tentative decisionalconferences hard on the heels of oral argument.In the United States SupremeCourt, for example, conferences are heldat the end of a week of oral argument, thuskeeping initial discussion of a case contemporaneouswith the oral argument.19 Onecommentator has even suggested that appellatecourts hold conferences or circulatetentative opinions prior to argument,thus increasing the likelihood that it willassist the court in its decision-makingprocess.20By concentratiw .. upon the Durposes oforaiargulntmt and npiiying objcc&e standardsforjudging the likcly effect of an argumentupon particular issues, counsel canmake an intelligent and productive decisionwhether to request oral argument. Presumingit is requested, counsel should then focusupon developing an effectivepresentation.How Should Counsel PrepareOral Argument?Counsel can ease much of the tensionrelated to his first argument before theCourt of Criminal Appeals by becomingfamiliar with the courtroom and the externaland internal court rules. In addition,counsel should watch several arguments:"observing the various styles ofargument and the reactions of the judges."Unless extended by the Court of CriminalAppeals in a special case, the totalmaximumtime for oral argument shall be 20minutes per side. Counsel for the appellantor petitioner is entitled to open andconclude the arg~ment."'~ "If oral argumentis permitted [after a motion for rehearingis granted], counsel will be limitedto 15 minutes per side. <strong>The</strong> movant is entitledto open and conclude the argume~~t."~'Any motions for extended argumentmust be timely filed with the Clerk of theCourt prior to the argument date andshould include specific reasons for allowingan extension of time." If counselwishes to reserve any time for rebuttal, heshould notify the timekeeper before argumentbegins.<strong>The</strong> Court, which consists of a "PresidingJudge" and eight "Judges,"= convenespromptly at 9:00 a.m. on Wednesdays withthe announcement of written opinions. AILparties arguing should then be present. <strong>The</strong>Presiding Judge then calls for the first caseto be argued. Each judge has before hima written memorandum, prepared by thestaff attorneys and studied by the jndgesprior to argument, that summarizes thefacts and issues present in each case. Uponcompletion of a case, the next case is inmediatelyargued, unless the Court recessesfor coffee or lunch.Facing the bench, counsel for the appellantis seated at the table on the left. <strong>The</strong>State's attorney is seated at the table on theright. A briefing attorney serves astimekeeper and is seated at a desk to theimmediate left of appellant's table, alongwith another briefing attorney who servesas bailiff.A clock and a diagram of the seating arrangementfor the judges are present on thespeaker's podium, which is located betweencounsels' tables. A yellow and a redlamp are also attached to the podium. <strong>The</strong>yellow lamp is Lit when counsel has oneminute remaining in his argument. <strong>The</strong> redlamp is lit when counsel's time has expired.Once time has expired, counsel should immediatelyconclude his argument or risksummary interruption by the PresidingJudge.Counsel should not feel compelled to useall of his time. Some of the best argumentshave often been made prior to the expirationof time but were significantlydi~inished in effectiveness by an attemptto fill the remaining time.To prepare the substance of his argument,at a minimum, counsel should rereadthe relevant portions of the record. Toooften, counsel imprudently downplays hisrole as appellate counsel by explaining thathe did not try the case. Counsel should thenstudy the relevant law and then prepare anoutline of his argument. Finally, counselshould practice his argument, making surethat sufficient time is left for questionsfrom the Court.If counsel is unable to provide the Court6 VOICE for rlze <strong>Defense</strong> / February 1987

with an mthoritatim? qmseto a questionmnming the record, he will losemuch of his credibility. Likewise, and0Derwk.e eEeotive argument is dilutedwhen counsel is unfamiliar with recent appellatedeeisioas.JustiGe Spears of the Texas upr re meCourt has noted the critical impoetance of .an outline:<strong>The</strong> otgdmprovided by an outlineis mucia! to a successful oral argumentfor several rms, =st, adisorganized presentation will confusea listener even more qWythan a poorly oqanized written argumentwilt confuse a readex. Second,heeauss your time forargument Bs limited, an outline ensuresthat you covet your ma@rpoints. Third, fhe ffow of your argum%ntmry beintempted by questioning,and fhe outline will hdp youto ream to pour former argument orto dungetbeorder of your argumentto ad;lpt to questioning?aftracted the iptmsst and attention of Briefs fired in direct ap~eals of capitalthe court. <strong>The</strong> room cam atiw fiurder 60nvictbns often allege multipleB~eryonei~asmtalfJtthewpoints of error." Extraordinary matten:of his chair, In-seconds mnsei had and post-eonviaion applications fw writsriveted the attention of all par- of b a h wpm alw g$ngrany conbintisipants unto the question tbt ail multiple complaints. It is auggestwt thatmcerned knew was critioaLn tbunsel arme no more than three pointsoFe~tov. neleetk onlvzho8sODints of erl'hesameapproaoh would prove eMvei r that relike$ to i$ e&& by oralIn tke Coure of C r W Appea18. <strong>The</strong> argument.judware familiar with the background of Gtter idewing the issue[%) in his ass,the case snd are premretl to heat COUIW counsel shoulditnmediately pfOwd to detdl fithem exactly what the bsues we and vetop his legal reatonin& suppo&g Itwhat relief is sought.wirh economical refernets to the record<strong>The</strong> majolity of cam before the and cae auFhorities.Cmrt of CriminaI Apmls involve p4-tiom for discretionarx review, vhich fOcusupon decisions of the courts ofappe,als?8 <strong>The</strong> Cmrt generally onlygrants a single, narrow ~ u n d forre vie^?^ If the pEtitiea correctlydescrih a ~pecifrcground for rwiew andthe brief properly focnses upon the sanfeground, fhen counsel will dmdy have anartow issue. for oral presntatdon." Ifseveral grounds for review have been-Coapel will not bepermittedto readat length from the brief, records orauthorities. Counsel may mab anoral comwtmn to his brief, bnt multipieadditionat cit&ions should notbe made orally; they should beredueed to writing and filed with heclerk."Counsel will more @anlikely he interyupteti~ted.then wwml &odd arfiue anly ed by quastions. He shqnld answer themffwunw~ has cons~imtious~y prepadfor those g&nds hest suited for od wg6- imm&&~~, weaving his ansms inm thewal argwmerrt, then his delivery of that ar- ment Fromapl-actical viewpoint, it is sug- mhstanoe of his argument. TBis task isgument .should provide the Court with a thatco counsel arguenodrethan two oftenqnitediffhIt, butanadvacateshouldvaluable blneplint for deciding the case. grounds for review. welcome questitlns because thef reflect theHow ~ u l Cmwl d PsesentOral Argument?Gtvm the physical limitatio~r~ placedupm om1 argument, w d mustmake efficientuse of his time, Counsel must beginby presenting the Court with anilmmdhte and coneiso StateiWnt Of themlevant isme. Justice G6dbbid ofthe UnitedStates Couct of Aaoeals for the FifthCircuit made the folGwing suggestion:I refall an especiaUJr effectivepresentation by a young lawyer,formerly a law derk for another circuitjudm who walked to the pdiumof out court and said: m y nameis So and So, from Houston, Texas.<strong>The</strong> issue, fb this case is whetherChwibl~r~.>y. d&csrotfey is r8tmBctive.")He had hidall else a6ideaadgone for the jugular. In two senteamhe had identffkd hinmlf, preeiselytargeted the dkposttive iaewon which discumion would be canteredand the case ddacided, and had1 ADVOCACY COURSEFebruary 1987 1 VOICE forth D6fetts.d 7

Court's interest in an issue.= At the conclusionof his argument, counsel should notmake open-ended requests for questionsfrom the Court on issues that have not beenargued. Counsel, after all, presumably hasalready requested oral argument on thoseissues he supposed worthy of oral argument.Although few lawyers thought so at thetime, one of the most critical coursesoffered in law school was Remedies 101,or some version thereof. Equally as criticalin an appellate argument is the prayeror reauest for relief. Does counsel seek anacquittal, a reversal, a vacate and remandorder, an affirmance, etc.? Whom doescounsel want to reverse or aftinn-the trialcourt, the court of appeals, the Court ofCriminal Appeals on rehearing? In short,counsel should know what remedy he isseeking." He should make it crystal clearto the Court and not get lost in the fog ofambivalent or alternative remedies.<strong>The</strong> procers of presenting oral argumentrequires an imaginative, diligent effort onthe part of attorneys. However, by makingjudicious use of oral argument, attorneysshould be able to affect and. indeed.improve the jurisprudential process itself:Effective oral argument will insure that appellatejudges receive not only accurate anduseful research but also information thatis persuasive in its artful presentation.I. Of mme, n crit~:inal Jcfcndaa's pcrwnal contactwith ihecoun is grwrally through his legalrepresentative because he has no constihrtionalright topresent his own oral argument before anappellate coun. Webb v. Slate. 533 S.W.Zd780,784-85 (Tex.Cr.App. 1976); Tookev. Srate. 23Tex.App. 10, 3 S.W. 782 (1887). CJ Anicle44.03, V.A.C.C.P. (Supp, 1986). repeated byV.A.C.S., art. 1811f. $4 (Supp. 1986) ("<strong>The</strong>defendant nced not be personally present upunthe hearingofhiscausein.. .thecourtof CriminalAppeals, but if not injail, he may appear inperson.'?. However, the Court of Criminal Appealsoccasionally allows adefendant topresenthis own aral argument. See Lenlry v. State, 13S.W.2d 874,884 Cl'ex.Cr.App. 1928) (opiniononrehearing). In fact, inthelast term, thecourtheard aral argument fmm a defendant who dividedhis time with his atlorney.2. Justices from the United States Supreme Courthave regularly offered their own suggestions forpresenting an effective oral argument before theirwun. See, e.g., Rehnquist, Oral Adsocac). 27S. 'Ter L. Kcv. 280 (1986); Powell, 77rr Ixvdof.%prw!,r C,,unAd,nvocy. Speech at 1:ifth Clr.Jud. Cmf. fMav 27. 1974): Harlan. IVl~rrr PurlAdwacy Before the Supreme Cow: Suggesliowfor Effecliw Gme Prerenrorions, 37 A.B.A.J.sol ii951).Justices from the Texas Supreme Coun havealso published their thoughts on oral argumentin their court. See, e.g., Spears, Pmenthtg anEffcc~he Appeal, 2K1) Trial 95 (1985); Greenhill,Advocacy in the Terns Suprenre Court, 44Tex. B.I. 624 (1981).3. See Tex. R. App. Pro. 220, 49 Tex. B.I. 558(1986) (hereinafter "Rule"). <strong>The</strong> Court has notspecifically excluded any cause fmm being arguedorally.Presumably, then, counsel can successfullyrequest oral argument in any causeaccepted for submission. Cf: Rule 750 ('Thcmurt of appeals may, in its discretion, advancecivil cases for submission withcat oral argumentwhere oral acgumeent would not materially aidthe court in he determination of the issues oflaw and faet presented in the appeal.'?.4. Rule 222(a).5. Rule 220. <strong>The</strong> Clerk generally mails notice tothe parks after the appell~le briefs have beenfiled. As a oractical matter. the Clerk reaucststhat rounscl rcspund within IS &ys uf notice.Simply including a wquest for oral aryumrnt inthe briefmay not be sufficient to comply withtherules. Cf: Rule75(9 ("A pany to the appealdeslnng oral argument [in the cow of appeals]shall file a request therefor st the time he fileshis brief 1n the case.'?.6 A motion requesting special consideration is nota "cause" subject to oral argument See Rule-.-\-, 212fA7. Rule 230(b).8. Rule 230(e).9. See Wasby, llie F~utctionsa~~dfinpoTfot~ce ofAppellateOral Argumnl: Smae Ken's oflawjersm,dFederalJlrdaes. 65 Judicature 340,351 352(198a); ~odbord, ntmy pages 02 TW,~).Mitrrrres-Effec0'r.e Ad~~oeneyo~~ Appe~l. 30 Sw.L.J. 801, 801-02 (1976).10. In 1985, outof 352 subminod causes, 144 or40.9pereent were orally argued. By contrast, the FifthCircuit has "made 'extensive use of truncatedprocedures,'with haoral argument in a high percentageof cases." Wasby, suprn note 9. at 34911.41.11. If an attorney is unable to attend aral argument,then he should notify the Clcrk of the Court atleast a week in advance of the argument date.Otherwise, counsel wastes Ule timeand resourcesof the Caurt and risks committing contemptuousconduct.12. Weaver, quored if, Sheldon & Weaver, PoLmCIANS. JUOOES. AND THE PEOPLE: A STUDY ~iCmZ6Ns PARTICIPATION 86 (WestpuCl, COnn.;Greenwwd Press, 1980).13. In a recont survey of federal circuit mun judges,only nine per cent regarded argumem based onsufficiency of the evidence as essential in civilappeals. Wasby, supra note 9, at 349.14. In a survey of lawyen fmm the Semnd, Fifthand Sixth Circuit Courts of Appeals, the lawyers"considered oral argument essential in 'caseswhich involve matters of great public interest(despite the absence of subslantial legal issues)[andl eases involving the constitutionality of astate shlute or a state aclion.*"Zd.., quoting DNry,Gaadman & Stevenson, Anonrrav An1-WDES TOWARD LlbUl'ATIONOF ORAL ARGUMENIAND WRlITEN OmNloNl~ THNB U.S. COURTSOF APPEAL, at 22 rnhington, D.C.: Bureau ofSocial Science Research, 1974).IS. See, e.g., MeOunbdge v Srale. 712 S.W.2d499, 501M n.9 (Tex.Cr.App. 1986).16. Thc Texas Supreme Coun records all oral arguments.17. Rule 222(c).18. Id.19. See Harlan, suprn note 2, at 7. Justice Harlanalso noted: "I amgiving away no secrets, I amsure, when I say that in one of the courts of ap-- . .oeals where1 was assiened to sit lemwrarilv thevoting an the cases took place each day follou,-ing thecloseof thearguments." Id. Using an evenmore radrcal approach, an intermediate Arizo-na &late court has a pallcy of issuing a tentativiwinen opinion to the parlics, allowingthem to argue the correctness of that opiniw.Telephone interview wilh Joyce Goldsmith,Clerk of the Division I1 Court of Appeals, Arizona(Nov. 17, 1986).20. See, Wasby, srrprn note 9, at 347.21. A number ofadvocates mcrit such attention, <strong>The</strong>authors recommend observing the following attorneys,who regularly present effective oral arguments:Chris Manhall, Assistant DistrictAttorney in Travis County; Edwilrd Shaughnessy,Assistant District Attorney in BexarCounty; RonaldGoranson, <strong>Defense</strong> Attorney inDallas County; and Janet Morrow. <strong>Defense</strong> Attorneyin Harris County.22. Rulc 221.23. Rule 230(e).24. Rule 212.25. See Tex. Conrt. an. V, S4.Attorneys commonlymake themistake of referring to members of theCourt of Crinlinal Appeals a; "Chieflustice" or"Justices." Those titles are resewed for membersof the Supreme Court. See Tex. Const. an. V,$3.26. Spears, supra none 2, at 97.27. Godbold, wpm note 9, at 809.28. Rule ZW(a).29. Rulc 202(d)(4).30. See McCnmhinge, rrrpra; see also Dcgrate vStnre. 712 S.W.2d755 (Tex.Cr.App. 1986) (percuriam).31. Under the new rules, former "gmunds of error"are now referred toas 'paints of ermr."See Rules74(d) & 21(i(b); Bwdlw s. Srute. No. 69,271,slipop. s1n.l (Tex.Cr.App. October 15, 1986)(not yet rcpaned).32. Rule 221.33. <strong>The</strong>reare masions whenquestions from men>bersof the Coun consume themaioritv of mun-. .wl's timc. pwenting \sl~;at ~wighl 113~ IKC~ 14brillisnl argLnwnt. Co~nsel rhuuld not ilrspairii this happns. It is s IAdy ~ign~l that tlw imterest of the Coun has been acutely piqued bythe issue praented.34. See Rules 80,202(k), & 211(c]; cl: Art. 44.24,V.A.C.C P. (Supp. 1986). &pealed byV.A.C S., art. 1811f. $4 (1986).8 VOICE for the Defe,tse / February 1987

Federal Sentencing in the 1980s and Beyond:Part I-A Practitioner's Guide to the Law of Sentencing Now in Effect andCurrent Practices of the United States Parole Commission and Federal Prison Systemby Alan EllisIntroductionIn response to a growing perception thatfederal sentences were grossly and unfairlydisparate, Congress passed as part of theComprehensive Crime Control Act of1984, a chapter entitled "<strong>The</strong> SentencingReform Act of 1984." While this legislationwill radically change federal sentencingas we now know it, despite its passagein 1984, the sentencing provisions, for themost part, will not take effect until November1, 1987.A major aspect of the Sentencing ReformAct of 1984 involves the creation ofthe United States Sentencing Conlmissionto be responsible for the promulgation ofsentencing guidelines to be submitted toCongress by April, 1987. Sentencingjudges will be bound by these guidelinesunless they find "that an aggravating ormitigating circumstance exists that was notadequately taken into consideration by theSentencing Colmnission." 28 U.S.C. 5994;18 U.S.C. §3553@). Parole will heabolished aud the amount of "good time"a prisoner can earn will he substantiallyreduced. In effect, the sentence imposedwill be the amount of time actually to beserved less approximately 15 percent.Since, however, the new sentencingprocess will not be completely in effect fora number of years, sentencing law andprocedure currently in effect as well aspractices and procedures of the UnitedStates Parole Commission and the FederalPrison System should be recognized bydefense attorneys as they approach the sentencingprocess.Part I of this acticle, therefore, dealswith such current law and practices. PartI1 to be published this spring, will discussthe new sentencing reforms to take effectin November, 1987.New LegislationWithin the last two and a half years, twonew laws have been enacted which drasticallyaffect the sentencing of federal criminaldefendants.On october 12, 1984, the ComprehensiveCrime Control Act of 1984 becameAlan Ellis of Plrilnrlelp11ia. Penrrs)~lvarriais narionally recognized for his successfdpost-co~rsiction represefrtntion ofcrimirral defendants. He writes, lectares,mrd practices atemively in the area ofplea bnrgairring, sentencing, Rale 35 Mo-tions, p~ison designation, parole, 2241 and2255 Motions and appeals.Mr. Ellis is n for~ner lawprofessor, andfederal law clerk to hvo United States DistrictCourt Judges. Presently, he serves asi71ir.d Vice-President of the National Associationof Criminal <strong>Defense</strong> Lnbvyers(NACDL) and is the Clrairmarr of its U.S.Serrterrcbrg Corn~nission Liaison Conunittee.Mr. Ellis was named as one of '82 Peopleto Watch in 1982 by Philadelphiamagazine and is listed in Who's Who inAmerican Law.law. This Act contained two chapterswhich deal primarily with sentencing: <strong>The</strong>Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 and theControlled Substances Penalties AmendmentAct of 1984.<strong>The</strong> drug penalty amendments increasedthe penalties for various controlled substancesoffenses and were made applicableto all offenses committed on or afterOctober 12, 1984. While a few of the provisionsof the Sentencing Reform Act tookeffect in 1984, most of the provisions donot take effect until November 1, 1987.As stated above, the major aspect of theSentencing Reform Act of 1984 involvedthe creation of a United States SentencingCommission to be responsible for thepromulgation of sentencing guidelines tobe submitted to Congress by April, 1987.Congress has six months thereafter to examineand consider the guidelines. Unlessrejected or modified by Congress, the proposedguidelines will take effect onNovember 1, 1987. A first preliminarydraft of the proposed guidelines has beenpromulgated by the US. Sentencing Commissionand can be found at 51 FederalRegister No. 190, pg. 15080 et seq. (October1, 1986). This preliminary draft willnot be discussed at this time except to saythat under the draft, sentences served bymost federal prisoners will be drasticallyincreased.<strong>The</strong> Controlled Substances PenaltiesAmendments Act of 1984, as above stated,increased the penalties for various controlledsubstances offenses and were madeapplicable to all offenses colnmitted on orafter October 12, 1984 and before October27, 1986.' <strong>The</strong> Controlled SubstancesPenalties Amendments Act of 1984 amendedthe penalties for 21 U.S.C. $841(a)(manufacture, distribution, possession withintent to distribute a controlled substance)and 21 USC §960@) (importation of a controlledsubstance) and increased the maximumprison sentence andlor fines fornumerous drug offenses.Three distinct categories of penaltieswere createdinnew21 U.S.C $841@)(1):(1) Enhanced penalties of up to twenty(20) years imprisonment and a fine of$250,000.00 for offenses involving certainlarge amounts of Schedule I or I1 narcoticdrugs, PCP and LSD;(2) Regular penalties of up to fifteen (15)years imprisonment and a fine of$125,000.00 for offenses involving allSchedule I or I1 controlled substances thatFebruary 1987 / VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> 9

tory minimum jail terms will be imposedfor drug trafficking offenses involving thefollowing quantities of the same controlledsubstances:(i) 100 grams or more of a mixture orsubstance containin a detectable amount ofheroin;(ii) 500 grams or more of a mixture orsubstance containing a detectable amountof -coca leaves, except coca leaves andextracts of coca leaves from which cocaine,ecgonine, and derivatives of ecgonineor their salts have been removed:(11) cocaine, its salts, optical and g oometric isomers, and salts of isomers:(111) ecgonine, its derivatives, theirsalts, isomers, and salts of isomers; or(IV) any compound, mixture, orpreparation which contains any quantity ofany of the substance referred to in subclauses(I) through (111);(iii) 5 grams or more of a mixture orsubstance described in clause (ii) whichcontains cocaine base;(iv) 10 grams or more of phencyclidine(PCP) or 100 grams or more of a mixtureor substance containing a detectableamount of phencyclidine (PCP);(v) 1 gram or more of a mixture or substancecontaining a detectable amount oflysergic acid diethylamide (LSD);(vi) 40 arams or more of a mixture orUnited States Code, or $2,000,000 if thedefendant is an individual and $5,000,000if the defendant is other than an individual.A court must also impose a term of supervisedrelease of at least four (4) yearson such "first-time drug offenders."Persons convicted of such offenses whohave prior, final state, federal or foreigndmg-related convictions must be sentencedto a mandatory minimum term of imprisonmentof ten (10) years with a maximumof life imprisonment. If death orserious bodily injury bas resulted from useof the substance in question, such "repeatdrug offenders" must be sentenced to lifeimprisonment. In addition to imposing aterm of imprisonment, a court may finesuch "repeat drug offenders" an amount notto exceed the greater of twice that authorizedunder Title 18, United States Code,or $4,000,000 if the defendant is an individualor $10,000,000 if the defendantis other than an individual. A court mustalso impose a term of supervised releaseof at least eight (8) years on such "repeatdrug offenders."Penalties Involvirrg Non-MandatoryJail TennsPenalties involving non-mandatory jailterms are to be imposed for traffickingoffenses involving lesser quantities of thecontrolled substances or anyother Schedule I or Il controlled substance(except for offenses involving less than 10kilograms of hashish or less than 1 kilogramof hashish oil or less than 50 kilogramsof marijuana unless the offenseinvolves 100 or more marijuana plantsregardless of weight). Persons convictedof such offenses who have no prior, finaldrug-related convictions may be sentencedto a term of imprisonment of up to twenty(20) years and may also be fined anamountnot to exceed the greater of that authorizedunder Title 18, United States Code, or$l,W0,000 if the defendant is an individualor $5,000,000 if the defendant is otherthan an individual. If death or serious bodilyinjury has resulted from use of the substancein question, however, such"first-time offenders" must be sentenced toa mandatory minimum term of imprisonmentof twenty (20) years with a maximumof life imprisonment and may also be finedaccording to the foregoing amounts. <strong>The</strong>court must also impose a term of supervisedrelease of at least three (3) years onall "first-time drug offenders."Persons convicted of such drug traffickingoffenses who have prior, final drugrelatedconvictions may be sentenced to aterm of imprisonment of up to thirty (30)years and may also be fined an amount notto exceed the greater of twice that authorizedunder Title 18, United States Code,or $2,000,000 if the defendant is an in-idinyl] propanamide or 10 grams or moreof a mrxture or substance containing a detectableamount of any analogue of N-phenyl-N-[1-(2-phenylethy1)-4-piperidinyl]propanamide; or(vii) 100 kilograms or more of a mixtureor substance containing a detectableamount of marijuana.Persons convicted of such drug traffickingoffenses who have no prior, final drugrelatedconvictions must be sentenced toa mandatory minimum term of imprisonmentof five (5) years, with a maximumof forty (40) years imprisonment. If deathor serious bodily injury has resulted fromuse of the substance in question, such"first-time drug offenders" must be sentencedto a mandatory minimum term ofimprisonment of twenty (20) years and amaximum of life imprisonment. In additionto imposing the term of imprisonment,a court may fine such "first-time drugoffenders" an amount not to exceed thegreater of that authorized under Title 18,<strong>The</strong> Attorney Who CaresWhatever the case. Whatever the Court.Our NationaI/InternationaI Sentencingand Parole Memorandums save precioustime. <strong>For</strong> You. <strong>For</strong> Your Clients. When alife is on the line, a second opinion can'thurt.Call Now: 1 -800-241 -0095NATIONAL LEGAL SERVICESSentencing Alternative Planning71 0 Lake View Avenue, Atlanta, Ga. 30308Sentencing and Parole ConsultantsFebruary 1987 1 VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> 11

dividual or $10,000,000 if the defendantis other than an individual. If death or seriousbodily injury has resulted from use ofthe substance in question, such "repeatdrug offenders" must be sentenced to lifeimprisonment and may also be fmed accordingto the foregoing amounts. <strong>The</strong>court must also impose a term of supervisedrelease of at least six (6) years onsuch "repeat drug offenders."<strong>The</strong> new Act also substantially increasesthe fines which may be imposed under Section401@) of the Controlled SubstancesAct (21 U.S.C. 841(b) or 1010@) of theControlled Substances Import and ExportAct (21 U.S.C. 960(b)) for drug traffickingoffenses involving less than 50 kilogramsof marijuana (except for offensesinvolving 100 or more marijuana plants,regardless of weight, which are punishableas set forth in21 U.S.C. §841@)(l)(c),as amended), 10 kilograms of hashish or1 kilogram of hashish oil. It also substantiallyincreases the fmes which may be imposedfor drug trafficking offenses underSection 401(a) of the Controlled SubstancesAct (21 U.S.C. §841(a)) involvingSchedule III, N and V controlledsubstances and for cultivation of controlledsubstances on federal property.'Work-Off" Provision<strong>The</strong> new Act provides that a court maynot place on probation or suspend the sentenceof any manduto~y minimum term ofimprlsonrne~zt. It also provides that such aperson may not be released on parole duringthe term of imprisonment. However,there is a "work-off provision in the newAct which allows a court to impose a termof imprisonment less ffmn the applicablemandatory minimvm term upon motion bythe government seeking such a reducedscntencc and dernonstratina that thc dcl'endanthas rendered suhstan&il assistance inthe investigation andlor prosecution ofanother criminal offender. However, thereduced sentence must still comport withthe guidelines to be established by the SentencingCommission.' F.R.Crim.P.35 isamended to make this latter restriction explicit.Federal Parole<strong>The</strong> Sentencing Reform Act of 1984abolishes the United States Parole Com-12 VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> /February 1987mission. At least one Court has held thatthe US. Parole Commission will go outof business on October 12, 1989: <strong>The</strong>Departmentof Justice and the Parole Commission,however, contend that it will remainin existenceuntil November 1,1992.In the meantime, however, nearly all federalprisoners, except those serving timeunder both old and new mandatory minimumsentencing provisions and, arguably,those with parole ineligibility dates under18 U.S.C. §4205(a) beyond 1989 or 1992.will become eligible for parole within thenext 3 to 5 years. It is thus extremely importantthat a federal practitioner heknowledgeable of the workings of theUnited States Parole Commission.Virtually no federal prisoner serves hisentire sentence actually confmed in prison.Unless earlier paroled. the prisoner will bemandatorily reieased from prison 180 daysbefore the scheduled end of his6 sentence,and the usual prisoners' stay will be furtherreduced by two types of goodtime:statutory goodtime and extra goodtime(also called meritorious goodtime, camptime and indusq time).A prisoner may be released as soon ashe becomes eligible for parole, andprisoners with sentences of five years orlonger must be paroled after serving twothirdsof their sentences in prison. Twothirdsof the sentence is roughly equal tototal sentence minus normal goodtimedeductions.Parole: What is It?Parole, like probation, is a grant of conditionalliberty. It occurs when a prisonerafter serving some portion of his sentenceis allowed to serve the remainder of his fullsentence in the community. A formerprisoner on parole rcmains under thc juris-diction of the United Statcs Pxolc Commission(the "Commission") until theexpiration of the maximum term to whichhe was sentenced. Thus, although free tolive and work in the community, theparolee must obey conditions imposed onhim by the Commission. Failure to do socould mean revocation of parole and returnto prison where he will be required to serveall or part of the remainder of his sentence.Usually, a federal prisoner may not bereleasedprior to the expiration of his sentenceexcept by order of the Commission.In order to obtain release, a prisoner whois eligible will be given a hearing beforea panel of Commission hearing examiner(~),~who regularly visit the variousfederal prisons every other month. <strong>The</strong>prisoner may be represented at this hearingby the person of his choice to speakon his behalf. This representative can be,but doesn't have to be, a lawyer.At the hearing, after discussing the casewith the prisoner, the examiner(s) will determinethe prisoner's parole guidelines,and win recommend to the Regional Offkeof the Commission whether and when theinmate should be paroled. This tentativerelease date is subject to modificationeither upward or downward.Within21 days, the Regional Cornmissionerwill send a Notice of Action to theprisoner notifying him of the offieial decisionin his case. This decision may thenhe appealed administratively to the NationalAppeals Board of the Commission.After exhausting the administrative appeal,the prisoner may challenge the Commission'sdecision in federal court, througha petition for writ of habeas corpus, commonlycalled a '2241" petition.A prisoner's case will be reheard atstatutorily-mandated interim hearings, untilhe is released on parole or at the mandatoryrelease date.Parole EligibiliiyParole eligibility is a requisite if theCommission is to release an inmate. <strong>The</strong>type of sentence an inmate is serving determineswhen he is eligible for parole:thus, eligibility is set by the sentencingjudge but affects the inmate throughout hisrelationship with the Cornniission. <strong>The</strong>various types of adult sentences a judgemay impose and the parole eligibity timeswhich correspond to them are described in18 U.S.C. 84205. <strong>The</strong> adult sentencesgenerally fall into the following categories:Regular Adult: 18 U.S.C. 54205(a): Aftercompleting 113 term or terms, or aftercompleting 10 years of a life sentence orof a sentence over 30 years."T-1": 18 U.S.C. §4205@)(1): At a timedesignated by the sentencing judge, whichmay not be later than 113 of the sentenceimposed."B-2": 18 U.S.C. §4205@)(2): Eligiblefor release immediately.As above indicated, a federal offenderusually becomes eligible for parole after

serving one-third of his sentence, or less,or even immediately after commencementof his sentence. However, because initialparole hearings need to be conducted only"within 120 days of a prisoner's arrival ata federal institution or as soon thereafteras practicable," in practice no prisoner isreleased immediately. <strong>The</strong> standard applicationof the parole guidelines discussedbelow also operates to foreclose the possibilityof immediate release.Life terms of sentences of 30 years orlonger must become eligible after serviceof 10 years, but not before.Of course, not all inmates are releasedat this eligibility date. Indeed, a good numberof inmates are never released on parolebut instead serve their entire sentence lessgoudtimt. 'l'l~c relcxr: daisicul dcp~~ds on:I vxrictv ot t;~ctur> ol'which eliaihilitv - - i\a necessary, but not the only consideration.Parole Guidelirres<strong>The</strong> Parole Commission and ReorganizationAct of 1976 provides a frameworkfor the release determination. <strong>The</strong> paroledate is figured by calculating, first, thedefendant's offender characteristicslparoleprognosis1 salient factor score and, second,the severity of the offense. Once these twoitems are determined, the Parole Commissionguideline chart will show a range ofmonths which will generally be servcd priorto release on parole. <strong>The</strong>se "guidelines"indicate the customary range of time to beserved before release for various combinationsof offense (severity) and offender(parole prognosis) characteristics. <strong>The</strong>time range as specified by the guidelinesis established specifically for cases withgood institutional adjustment and programprogress. However, where aggravating ormitigating circumstances warrant, decisionsoutside of the guidelines, eitherabove or below, may be rendered. <strong>The</strong>gn~delines appear on a chart which measurestwo factors: (1) offense severity leveland (2) salient factor score.'<strong>The</strong>re are eight offense severity levelsranging from category one or lowestseverity, through category eight or highest.<strong>The</strong> "offense severity" levels subjectivelymeasure the relative seriousness of thecrime for which the defendant was cnnvicted.All offenses are indexed according toone of the eight offense severity categories.<strong>The</strong> second component of the guidelinessystem is called the "salient factor score,"which is intended to be clinically predictiveindicating the likelihood of the inmate'sfavorable parole prognosis. <strong>The</strong> salientfactor score primarily measures the defendant'scriminal history, and other statisticallyrelevant factors. It is based on a10-point evaluation system which, converselyto the offense severity categories,rewards "very good parole prognosis witha score of 8 to 10, with poorer parole prognosisafforded a lower point total.<strong>The</strong> Initial Parole HearingTiming of the initial parole hearing canbe a key factor in the outcome of any decisionand should be considered by the inmateand his attorney as part of theirstrategy. However, an inmate is entitled toan initial parole hearing within 120 daysof his arrival at a federal institution, or assoon thereafter as is practical. <strong>The</strong>re arethree exceptions to this rule: (1) a prisonerwho is not eligible for parole for ten yearsor longer does not have a right to an initialhearing until at least 90 days prior tothe completion of such minimum term, oras soon thereafter as is practical; (2) a federalprisoner serving concurrent state andfederal sentences in a state institution isgiven ;m ill-pcrsun hearing as soon as feasihlcaitcr his nrrivdl at a fcderal instilulion;and (3) a prisoner who is serving a federalsentence exclusively, but is being boardedin a state or local institution, may receivea federal parole hearing at the state or localinstitution, or may be transferred to a federalinstitution for a hearing.Application for this initial hearing ismade when the inmate completes the appropriateapplication form and an InmateBackground Statement. He may also waiveparole consideration as part of an overallstrategy and apply later. At least 60 daysprior to the hearing, the prisoner must beprovided with written notice of time andplace of the hearing and of his right toreview documents considered by the Commission.<strong>The</strong>se documents include the presentenceinvestigation report (PSI), theUSA 792 form, and the AO-235 form.<strong>The</strong>se last two forms are sent by the U.S.Attorney's office and the sentencing judge,respectively, and they reflect, among otherthings, the prosecutor and judge's recommendationsas to when parole should begranted. Documents from the RegionalParole File will he disclosed to him within40 working days of his request. Documentsin an Inmate's Institutional File will be disclosedto him within 15 calendar days ofhis request. Diagnostic opinions, confidentialmaterial, and material which, if disclosed,might result in harm to another areexempt for disclosure. In such cases, theCommission and the Bureau of Prisons arerequired to identify what material is beingwithheld and summarize its contents.<strong>The</strong> prisoner's parole representative isthen permitted to review the disclosableportions of his client's file within 30 daysof the initial parole hearing.Several hearing examiner($ visit eachfederal prison every two months to conductparole hearings. <strong>The</strong> purpose of thehearing is for the examiner($ to discussan inmate's background with him, determineguidelines, and recommend a paroledate to the Regional Commissioner. Hearingsare conducted in small rooms at theinstitution and are tape recorded. Presentare two hearing examiners from the Commission:the inmate, his case manager,and, if he wishes, a representative to speakon his behalf. This representative may bea relative or friend, a fellow inmate, amember of the institution staff, an attorney,or parole specialist. Representativesare not permitted to act in an adversarialcapacity by participating in the questioningor advising the inmate during thecourse of the hearing, but may simplymake a short statement at the end of thehearing. Representatives, of course, canaid an inmate in preparing for the hearing.An attomeylrepresentative can, also, oftenidentify problem areas that might arise duringthe hearing and recommend legal actionto he taken to prevent this.<strong>The</strong> hearing usually starts when the ex-aminer(~) introduce themselves and explainboth the hearing and appeal procedures tothe inmate. One, or occasionally both, ofthe examiner($ questions the inmate abouthis crime, background, institution recordand activities, and release plans with an eyetoward guidelines calculations. At this timethe examin@) usually, but not necessardy,advise the inmate of their tentativeguideline evaluation.<strong>The</strong> Parole Commission has recently implementeda pre-hearing assessment procedureunder which the inmate's case file isanalyzed several weeks before the actualhearing. This is not, however, a requiredFebruary 1987 1 VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> 13

procedure. When prehearing assessments nied or a release date in excess of six within 30 days of the entry of the decision.are done, however, inmates sometimes are months from the date of the hearing is set, In practice, this means within 30 days ofgiven written notice, before theh- hearings, the prisoner must also receive in writing the date on the Notice of Action, regardofthe examiner@)' initial assessment of a statement outlining the reasons for this less of when the inmate received the Notheirguidelines. This initial guidelines as- decision. Similarly, if a decision outside tice. <strong>The</strong> Commission has provided,sessment is, of course, subject to change of the guidelines is made, the Commission however, that since Notices of Action areat the hearing, but is considered by the ex- must advise the inmate in writing of the not typically date stamped in the instituaminer(s).specific factors and information relied tion, any appeal received within 45 daysAfter permitting theinmate to speak, the upon for departing from the guidelines. of the date of the Notice of Action will beexaminer(s) ask the representative if he <strong>The</strong> Commission's decision is normally accepted. If no appeal is filed within thiswishes to make a statement. After all state- based to a great extent on information con- time period, however, the decision renmentshave been made, the representative tained in the prisoner's PSI, especially that dered stands as the fmal decision of theand the inmate leave the mom while the section called the "prosecution version." Commission.examiner(s) confer; the case manager re- <strong>The</strong> description included in the PSI of the <strong>The</strong> grounds for appeal specified by themains in the hearing room. prisoner's offense having been usually Commission are:<strong>The</strong> inmate and representative are then provided by the prosecutor, may he inac- -That the guidelines were incorrectlyasked to return to the room, at which time wrate and heavily biased against the applied.theexaminer(s) state what their recommen- prisoner. Thus, a prisoner's representative -That a decision outside the guidelinesdation to the Regional Commission will be. at the parole hearing will normally have was not supported by the reasons or facts<strong>The</strong> Pre-Sentencelnvestigation (PSI) is to supplement the Commission's file with as stated.the document upon which the Commis- accurate information, and challenge any in- -That especially mitigating circumsionrelies most heavily. <strong>The</strong> PSI is a correct information, and take further legal stances justify a different decision.report prepared by a probation officer at action to have the PSI corrected. -That a decision was based on erronethejudge's request prior to sentencing, and If inaccurate information in the PSI is ous information and the actual facts justiitcan contain a summary of the inmate's identified, and it should he before the hear- fy a different decision.prior criminal, medical, family and em- ing, an attempt to have the sentencing -That the Commission did not followployment record as well as a description judge order corrections is advised. This correct procedures in deciding the case,of the current offense behavior. This may require making a motion pursuant to and a different decision would haveresultdescriptionis commonly calledthe"prose- 28 U.S.C. 52255 asking that the sentence ed it the error had not occurred.cution version." It is this version of the he vacated due to the fact that it was based -That there was significant informationoffense that the examiner(s) generally look on inaccurate information; or in the alter- in existence but not known at the time ofto in determining a prisoner's "offense native, for a correction of the PSI pursuant the hearing.severity" score. to F.R.Crim.P. 32. Once the corrections -That therearecompelling reasons whyare accepted, the Parole Commission a more lenient decision should be rendered<strong>The</strong> Notice of Action should be notified. on grounds of compassion.A prisoner may dispute the accuracy of <strong>The</strong> National Appeals Board must in-<strong>The</strong> examiner($ may recommend one of any information in his file. <strong>The</strong> Commis- form the inmate in writing of its decisionthree dispositions to the Commission's sion must resolve such disputes by the and the reasons for it withrn 60 days ofRegional Officer: (1) an effective parole "preponderance of the evidence'' standard. receipt of the appeal; however actualdate within six months of the hearing; (2) Note, of course, that the Commission has response timeis oftenlonger. <strong>The</strong> Nationala presumptive release date (either by parole a great deal of discretion in its decision to Appeals Board may affi, reverse oror by mandatory release) more than six grant or deny parole, and challenges to the modify the decision or order a rehearing.months after the hearing; (3) a "set-off" or Commission's use of erroneous informa- No appeal may result in a decision morecontinuation for a ten-year reconsideration tion are not necessarily effective. It is, adverse to the inmate.hearing if the projected mandatory release thus, best to have the sentencing judge is- <strong>The</strong>National Appealmust be submitteddate is within 10 years of the hearing date. sue an order directing that the PSI be cor- to the Regional office, which then trans-<strong>The</strong> Regional Commissioner may accept rected if such inaccuracies are contained mits it to Washington, D.C., along withtheir recommendation, modify or reverse in the report. the prisoner's case file. <strong>For</strong>ms are availaitif it is outside the guideline range, orble from the prisoner's case manager formodify it to bring it to a date not to ex- Appeals and Furthw Proceedings the appeal. Representatives may, and oftenceed six months from the recommended Administrative Appeal do, submit a memorandum along with thedate, or refer the case to the National Com-form in support of and explaining the ismissionersfor further consideration. With few exceptions, any decision made sues raised on appeal.<strong>The</strong> Regional Office must inform the in- by the Parole Commission may he apmateof its decision within 21 days of the pealed administratively by the inmate. Sub- inter in^ Hearingdate of the hearing, usually on a form mission of a written appeal by the inmatecalled a "Notice of Action." If parole is de- to the National Appeals Board must occur If the prisoner is not released soon after14 VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> /February 1987

his initial parole hearing, he is statutorily employed by the Commission to assist the parolees with a lesser salient factor scoregranted "interim" review hearings. An in- Bureau of Prisons in the maintenance of will be released after three suchyears. Afmatewill have an interim hearing every 18 institutional discipline. Guidelines for these ter five years of supervision in the commonthsif he is serving a sentence of less decisions have been enacted by the Com- munity, the Commission must terminatethan seven years, or every 24 months if he mission. jurisdiction unless it fmds, after a hearing,is serving a sentenee of seven years orthat there is a likelihood of further crime.more. However, in the case of a prisoner Case Reopening An inmate must have appropriate releasewith an unsatisfied minimum term, the firstplans made before he embarks on parole.interim hearing will be deferred until the Any finally-decided case may be reo- Once on parole he must comply with anydocket of hearing immediately preceding pened by the Regional Commissioner upon conditions imposed upon him by the Comthemonth of parole eligibility. <strong>The</strong> pur- receipt of new information of "substantial mission. <strong>The</strong>se conditions include, but arepose of these hearings is to consider any significance." <strong>The</strong>re are six grounds for re- not limited to, that the pamlee report to thissignificant developments or changes that opening a case: (1) receipt of favorablein- probation officer, not associate with permayhave occurred in the prisoner's status formation which is "clearly exceptional"; sons having a criminal record, not act assubsequent to the initial hearing. (2) receipt of new adverse information; (3) an informer, not possess weapons, remainFollowing the interim hearing, the Com- institutional misconduct; (4) new or addi- employed, not use drugs, and not use almissionmay: (1) order no change in the tioual sentences; (5) convictions after cohol to excess. In addition, restrictions onprevious decision; (2) advance apresump- parole revocation; and (6) changes in or parolee travel may be imposed.tive release date because of superior pro- insufficiency of release plans. When a case Parole may be revoked at any time if thegram achievement or other exceptional is reopened, the inmate receives a"special parolee violates the conditions of releasecircumstances; (3) retard or cancel parole reconsideration hearing." embodied in his particular parole contract.for disciplinary reasons; or (4) if the <strong>The</strong> Bureau of Prisons may petition for Revocation of parole can result in reincarpresumptiverelease date falls within six a reopening of the case and consideration ceration for all or a portion of the inmate'smonths of the interim hearing, it may be forparole prior to thedatepreviously set, parole term, i.e., the portions of the sentreatedas a pre-release review. for good cause, such as, emergency, hard- tence term remaining when he wasIt is the policy of the Commission that ship, or other extraordinary circumstances. released on parole. This is true regardlessa presumptive parole date may be ad- In addition, an inmate may receive of the time that the revocation or the viovancedonly for sustained superior pro- reductions from his presumptive parole lation occurs.gram achievement or other clearly date based upon "superior program Followingrevocation, aparoleereceivedexceptional circumstances. It is the intent achievement" beyond the normally good credit for time under supervision in theof the Commission to encourage meaning- institutional record which is elmost always community unless convicted of a crimeful voluntary program participation, not a prerequisite to parole release. <strong>The</strong> max- committed while under supervision. Asuperficial attendance in programs mere- imum permissible reductions range from parolee who has absconded from supervilyin an attempt to impress the parole 1 month for inmates who have received sion is credited with the time and the datedecision-makers. <strong>The</strong>refore, the advance- original presumptive parole dates of 15 to of release to supervision to the date of suchments permitted for superior program 22 months, to as much as 13 months for absconding.achievement are dehberately kept modest. inmates with presumptive parole date of 91months or more. Partial reduction underFederal Prison Designation andPre-Release Review the maximum for which the inmate is eligiblemay be given if, for example, an in-Conditions of ConfinementPrerelease reviews are a special type of mate with superior program achievement Beyond simply the amount of time, ifinterim hearing, held at least 60 days pri- is subject to a minor disciplinary in- any, the convicted defendant will spend in-or-to a presumptive release date in order fraction. carcerated, where he or she will spend thatto determine %hether the conditions of atime is of utmost importance to the defenpresumptiverelease date by parole have Relense on Parole dant seeking counsel.been satisfied," that is, whether the inmate<strong>The</strong> 47 institutions in the Federal Prisonhas maintained a satisfactory institutional An inmatemay beparoledC'to the street," System have been grouped into 6 securityconduct record since his last hearing and to a state, local, or immigration detainer, levels. An institution's security level iswhether release plans are in order. After or to a community treatment center (CTC). based upon the type of perimeter secnriaprerelease review, the Regional Com- Once "on the street" he will remain under ty, the nnmber of towers, its externalmissioner may exercise one of the first thejurisdiction of the Commission andun- patrols, its detection devices, the securitythree options described above, or he may der the supervision of a probation officer of housing areas, the type of living quartapprovethe parole date hut advance or until the end of his sentence term or until ers, and the level of staffing. Institutionsretard it for purposes of development and the Commission terminates ifs jurisdiction. labeled "Security Level 1" provide the leastapproval of release planning. A parole res- Parolees who have a salient factor score restrictive environment and the "Securitycission hearing may he ordered where mis of 8 or better will normally be terminated Level 6" institution is the most secure. Adconductappears to be present. Decisions after two years of supervision without new ditionally, prisons in a special administratorescind or retard parole are sanctions criminal conduct or serious violation; tive category may contain all six levelsFebruary 1987 1 V'OlCE for the <strong>Defense</strong> 15