SIGCHI Conference Paper Format - Mark Ashdown

SIGCHI Conference Paper Format - Mark Ashdown

SIGCHI Conference Paper Format - Mark Ashdown

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

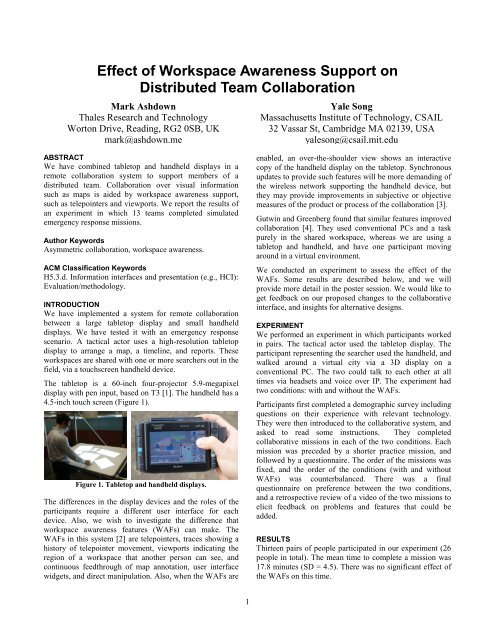

Effect of Workspace Awareness Support onDistributed Team Collaboration<strong>Mark</strong> <strong>Ashdown</strong>Thales Research and TechnologyWorton Drive, Reading, RG2 0SB, UKmark@ashdown.meYale SongMassachusetts Institute of Technology, CSAIL32 Vassar St, Cambridge MA 02139, USAyalesong@csail.mit.eduABSTRACTWe have combined tabletop and handheld displays in aremote collaboration system to support members of adistributed team. Collaboration over visual informationsuch as maps is aided by workspace awareness support,such as telepointers and viewports. We report the results ofan experiment in which 13 teams completed simulatedemergency response missions.Author KeywordsAsymmetric collaboration, workspace awareness.ACM Classification KeywordsH5.3.d. Information interfaces and presentation (e.g., HCI):Evaluation/methodology.INTRODUCTIONWe have implemented a system for remote collaborationbetween a large tabletop display and small handhelddisplays. We have tested it with an emergency responsescenario. A tactical actor uses a high-resolution tabletopdisplay to arrange a map, a timeline, and reports. Theseworkspaces are shared with one or more searchers out in thefield, via a touchscreen handheld device.The tabletop is a 60-inch four-projector 5.9-megapixeldisplay with pen input, based on T3 [1]. The handheld has a4.5-inch touch screen (Figure 1).Figure 1. Tabletop and handheld displays.The differences in the display devices and the roles of theparticipants require a different user interface for eachdevice. Also, we wish to investigate the difference thatworkspace awareness features (WAFs) can make. TheWAFs in this system [2] are telepointers, traces showing ahistory of telepointer movement, viewports indicating theregion of a workspace that another person can see, andcontinuous feedthrough of map annotation, user interfacewidgets, and direct manipulation. Also, when the WAFs areenabled, an over-the-shoulder view shows an interactivecopy of the handheld display on the tabletop. Synchronousupdates to provide such features will be more demanding ofthe wireless network supporting the handheld device, butthey may provide improvements in subjective or objectivemeasures of the product or process of the collaboration [3].Gutwin and Greenberg found that similar features improvedcollaboration [4]. They used conventional PCs and a taskpurely in the shared workspace, whereas we are using atabletop and handheld, and have one participant movingaround in a virtual environment.We conducted an experiment to assess the effect of theWAFs. Some results are described below, and we willprovide more detail in the poster session. We would like toget feedback on our proposed changes to the collaborativeinterface, and insights for alternative designs.EXPERIMENTWe performed an experiment in which participants workedin pairs. The tactical actor used the tabletop display. Theparticipant representing the searcher used the handheld, andwalked around a virtual city via a 3D display on aconventional PC. The two could talk to each other at alltimes via headsets and voice over IP. The experiment hadtwo conditions: with and without the WAFs.Participants first completed a demographic survey includingquestions on their experience with relevant technology.They were then introduced to the collaborative system, andasked to read some instructions. They completedcollaborative missions in each of the two conditions. Eachmission was preceded by a shorter practice mission, andfollowed by a questionnaire. The order of the missions wasfixed, and the order of the conditions (with and withoutWAFs) was counterbalanced. There was a finalquestionnaire on preference between the two conditions,and a retrospective review of a video of the two missions toelicit feedback on problems and features that could beadded.RESULTSThirteen pairs of people participated in our experiment (26people in total). The mean time to complete a mission was17.8 minutes (SD = 4.5). There was no significant effect ofthe WAFs on this time.1

Figure 2. Preference for the two conditions.Participants used versions of three shared workspaces withand without the WAFs. Figure 2 shows their statedpreference.The words spoken by the participants were assigned toseveral categories: Status "I've entered the site", Guiding"Go this way", Situation Awareness (SA) updates "Theroad is blocked here", Reporting (voicing informationwhich should be entered into a form), Feedback "OK",Social (joking), Meta-coordination "Can you see what I'vedrawn", and Other. Guiding and SA utterances wereclassified as deictic or non-deictic, depending on whetherthey involved pointing within a workspace. Deictic guidingwas possible without WAFs by using annotations. Figure 3shows that there was significantly more deictic guiding inthe condition with WAFs.Figure 4. Proportion of reports entered by each participant.DISCUSSIONParticipants preferred to have the WAFs for the map andreports. The amount of guiding was the same in the twoconditions, but more of it was deictic when the WAFs wereenabled. Collaborative reporting was used a little, butfeedback indicated the concurrency could be a source oferror.Qualitative feedback and suggestions were obtained fromthe questionnaires and retrospectives. On the tabletop, therewas mode confusion on the map because the toolbar wasoften out of the user’s field of view. The over-the-shoulderview was useful for monitoring the other participant’sactions and remaining aware of his restricted view, butinteraction with it should probably be disabled because ofpossible errors due to concurrent access from multipledisplays. Simple sketch recognition was used for enteringwaypoints that formed a route on the map, but inaccuracy inthe recognition was magnified by the time pressure of themission, causing frustration for some users.On the handheld, auditory icons, and possibly vibration,would help by directing the user’s attention to the device atthe right time. Lack of precision when drawing with thefinger on the handheld was a problem. This could bealleviated by providing a collection of drag-and-dropsymbols for common incidents.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThis work was funded by European Commission MarieCurie Outgoing International Fellowship 21743.Figure 3. Word counts for utterance types.Reports containing information obtained by the searcherhad to be entered. The entry could be done by eitherparticipant. Figure 4 shows the proportion of reportsentered by each one. Collaborative reporting was notavailable when WAFs were disabled.The tactical actor had the option of remotely panning themap on the handheld by dragging a region on the tabletopmap. Around half of the teams used this option. The tacticalactor usually indicated his intention to pan the otherperson’s map vocally, before doing so. This seemed to be acourtesy, implying he was encroaching into the otherperson’s territory.REFERENCES1. Tuddenham, P. and Robinson, P. T3: Rapid Prototyping ofHigh-Resolution and Mixed-Presence Tabletop Applications.Proc. TABLETOP 2007.2. <strong>Ashdown</strong>, M. Awareness in Synchronous Collaborationbetween Tabletop and Handheld Displays. Poster inTABLETOP 2008.3. Gutwin, C. and Greenberg, S. The Importance of Awarenessfor Team Cognition in Distributed Collaboration, in E. Salas etal. (Eds) Team Cognition: Process and Performance at theInter- and Intra-individual, APA Press, 2004.4. Gutwin, C. and Greenberg, S. The Effects of WorkspaceAwareness Support on the Usability of Real-Time DistributedGroupware. ACM Trans. Computer-Human Interaction 6:3,Sept 1999, 243–28.2