ADDICTED AND CORRUPTED - Kentucky.com

ADDICTED AND CORRUPTED - Kentucky.com

ADDICTED AND CORRUPTED - Kentucky.com

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

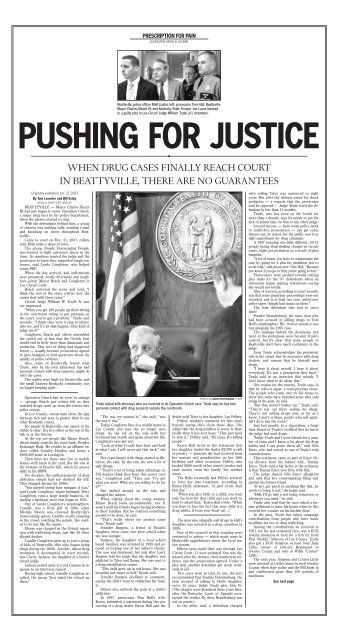

PRESCRIPTION FOR PAINLEXINGTON HERALD-LEADERBeattyville police officer Matt Easter, left; prosecutor Tom Hall; BeattyvilleMayor Charles Beach III; and <strong>Kentucky</strong> State Trooper Joe Lucas listenedto a guilty plea in Lee Circuit Judge William Trude Jr.’s chambers.PUSHING FOR JUSTICE◆WHEN DRUG CASES FINALLY REACH COURTIN BEATTYVILLE, THERE ARE NO GUARANTEESOriginally published Jan. 27, 2003By Tom Lasseter and Bill EstepHERALD-LEADER STAFF WRITERSBEATTYVILLE — Mayor Charles BeachIII had just begun to savor Operation Grinch,a major drug bust by his police department,when the phones started to ring.With the defendants behind bars, a groupof citizens was making calls, sending e-mailand knocking on doors throughout Beattyville.Come to court on Dec. 21, 2001, callerssaid. Help make a show of force.The group, People Encouraging People,was formed to fight substance abuse in thetown. Its members wanted the judge and theprosecutor to know they supported tough sentences,said Lynda Congleton, who helpedcreate PEP.When the day arrived, and indictmentswere presented, nearly 40 friends and neighborsjoined Mayor Beach and Congleton inLee Circuit Court.Beach surveyed the scene and said, “Ithink the rest of the story will be how thecourts deal with these cases.”Circuit Judge William W. Trude Jr. wasnot impressed.“When you get 100 people up there sittingin the courtroom trying to put pressure onthe court, you’ve got a problem,” Trude saidrecently. “I think they were trying to intimidateme, and if I let that happen, what kind ofjudge am I?”Congleton, Beach and others assembledthe crowd out of fear that the Grinch bustwould end in little more than dismissals andprobation. That sort of thing had happenedbefore — usually because prosecutors agreedto plea bargains or had questions about thequality of police evidence.Also, some in Beattyville feared whatTrude, who by his own admission has hadpersonal contact with drug suspects, might dowith the cases.The stakes were high for Beattyville, andthe small Eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong> <strong>com</strong>munity wasno longer keeping quiet.Operation Grinch had its roots in outrage— outrage Beach and others felt as theywatched drugs crawl up from the streets intopolite society.In Lee County, census data show, the gapbetween rich and poor is greater than in anyother <strong>Kentucky</strong> county.For people in Beattyville, one aspect of thedivide is clear: You live either at the top of thehill, or at the bottom.At the top are people like Mayor Beach,whose family controls the town bank, PeoplesExchange Bank. He resides in an affluent enclavecalled Gourley Heights and keeps a$500,000 home in Lexington.Then there are those who live in mobilehomes with trash in the yard, like the one atthe bottom of Beach’s hill, which he passesdaily in his BMW.For decades, the embarrassment of drugaddiction simply had not climbed the hill.That changed during the 1990s.“You started seeing how rampant it was,”said Lynda Congleton, whose husband, TerryCongleton, runs a large family business, includinga hardware store that began in 1921.One of Lynda Congleton’s stepdaughters,Camille, was a little girl in 1984, whenMichele Moore was crowned Beattyville’shome<strong>com</strong>ing queen. Camille recalls standingin the crowd, watching the parade. She wantedto be just like the queen.Moore was charged in the Grinch operationwith trafficking drugs, just like 48 otheralleged dealers.Camille Congleton grew up to join a groupof kids of Beattyville elite who began usingdrugs during the 1990s. Another, whose drugtreatment is documented in court records,was Cherry Jackson, the daughter of a formercircuit judge.Jackson peeled away in a red Camaro in responseto an interview request.During high school, Camille Congleton recalled,the group “just ruled the school upthere.”PHOTOS BY DAVID STEPHENSON | STAFFTrude talked with attorneys who are involved in an Operation Grinch case. Trude says he has hadpersonal contact with drug suspects outside the courtroom.“The way we wanted it,” she said, “wasthe way it was.”Today, Congleton lives in a mobile home inLee County and says she no longer usesdrugs. As she sat on the sofa with herboyfriend last month and spoke about her life,Congleton’s eyes got wet.“Look at what I could have had, and lookat what I am. I will never get that back,” shesaid.Her experiments with drugs started as flirtation,she said. By the end, she saw a lot ofugly things.“There’s a lot of being taken advantage of.Pill dealers think they have this power overyou,” Congleton said. “They say, ‘I’ve gotwhat you need. What are you willing to do forit?’”She shifted around on the sofa andchanged the subject.When talking about the young women,Mayor Beach looks un<strong>com</strong>fortable, too. Itwasn’t until his friends began having problemsin their families that he realized somethingneeded to be done, he said.“That’s really where my passion camefrom,” Beach said.Jennifer Burgess, a friend of Beach’sdaughter, often came over after school whenshe was younger.Burgess, the daughter of a local schoolboard member, was arrested in 1999 and accusedof forging one of her father’s checks.The case was dismissed, but only after LarryBurgess told the judge that his daughter wasaddicted to Tylox and Xanax. She was sent toa drug-rehabilitation center.“This child grew up in our house. She wasbeautiful and smart as hell,” Beach said.Jennifer Burgess declined to <strong>com</strong>ment,saying she didn’t want to embarrass her family.Others also suffered the pain of a child’saddiction.In 1997, prosecutor Tom Hall’s wife,Karen, submitted a statement during the sentencingof a drug dealer. Karen Hall said thedealer sold Tylox to her daughter, Lyn Pelfrey.Pelfrey wouldn’t <strong>com</strong>ment for this storybeyond saying she’s clean these days. Sheadded that the drug problem is worse in Beattyvillethan it has ever been. “They just needto stop it,” Pelfrey said. “It’s crazy. It’s killingpeople.”Karen Hall wrote in the statement thather daughter traded the dealer $2,000 worthof jewelry — presents she had received fromher parents and grandmother on her 16thbirthday and other occasions. Pelfrey alsohocked $800 worth of her sister’s jewelry andstole money from the family, her motherwrote.The Halls eventually had Pelfrey arrestedto force her into treatment, according toKaren Hall’s statement. “A part of me diedthat day.”“When you give birth to a child, you wantonly the best for that child and you work sohard to attain that,” Karen Hall wrote. “Whenyou have to face the fact that your child is adrug addict, it tears your heart out …”The man who allegedly sold drugs to Hall’sdaughter was arrested in a drug operation in1995.Few of the accused in that roundup weresentenced to prison — which made some inBeattyville apprehensive about the local justicesystem.Fifteen cases made their way through LeeCircuit Court; 11 were probated. One was dismissedafter the defense cited insufficient evidenceand the prosecution agreed. Under aplea deal, another defendant got seven weekendsin jail.Two cases went to trial. In one, the juryre<strong>com</strong>mended that Frankie Brandenburg, theman accused of selling to Hall’s daughter,serve 15 years. Judge Trude gave him 10.(The charges were dismissed three years later,after the <strong>Kentucky</strong> Court of Appeals overturnedthe verdict. By then, Brandenburg wasout on parole.)In the other trial, a defendant chargedwith selling Tylox was sentenced to eightyears. But after the defense asked for shockprobation — a request that the prosecutorsaid he opposed — Judge Trude freed the defendantin less than 11 months.Trude, who has been on the bench formore than a decade, says it’s unfair to pin thelack of prison time on him or any other judge.Several factors — from weak police workto ineffective prosecution — can get casesthrown out, he noted, but the public sees it aslight punishment for drug criminals.A 1997 roundup was little different. Of 12people facing drug-dealing charges in circuitcourt, eight got probation as a result of pleabargains.“A lot of times, you have to <strong>com</strong>promise thecase by going for a plea for probation just toavoid trial,” said prosecutor Tom Hall. “Becauseyou know if you go to trial, you’re going to lose.”Prosecutors were pushed toward cuttingplea deals for the ’97 defendants when aninformant began signing statements sayingshe would not testify.Also of concern, according to court records,was that some grand-jury proceedings were notrecorded, and in at least one case, undercoverpolice tapes “simply had music on them.”The lone defendant who had to servetime?Frankie Brandenburg, the same man whohad been accused of selling drugs to TomHall’s stepdaughter. His 10-year sentence wasrun alongside his 1995 case.The mishaps behind the dismissals andmost of the probations were beyond Trude’scontrol, but it’s clear that some people inBeattyville don’t have much confidence in thejudge.Even Trude acknowledges the persistenttalk in his circuit that he associates with drugdealers, and rumors that he himself usesdrugs.“I hear it about myself. I hear it abouteverybody. It’s just a perception they have,”Trude said in an interview this month. “Idon’t know what to do about that.”One reason for the rumors, Trude says, isthat he collects agate, a semi-precious stone.The people who <strong>com</strong>e over to his house toshow him rocks have included some who solddrugs in the past, he said.“But that doesn’t bother me,” Trude said.“They’re not out there selling me drugs.They’re not selling drugs now, as far as Iknow. I don’t critique people who sell agate.All I do is buy the rocks.”Just last month, in a deposition, a longtimefriend of Trude’s testified that he knewthe judge had used drugs.“Judge Trude and I were friends for a numberof years and I know a lot about his drughabits and I can prove them all,” said OlinEstes, who had served as one of Trude’s trial<strong>com</strong>missioners.That testimony came as part of Estes’ bitterdivorce from his former wife, TammyEstes. Trude said a big factor in the acrimonyis that Tammy Estes now lives with him.The judge denied Olin Estes’ allegationand said that he’s contemplating filing suitagainst his former friend.“If he’s got proof of anything like that, heneeds to bring it out,” the judge said.“Hell, I’ll go take a test today, tomorrow orwhenever you want,” he said.Trude also said that he once asked a formergirlfriend to leave his house when he discoveredher cocaine on his kitchen floor.In the past, Trude has taken campaigncontributions from people who later madeheadlines for ties to drug trafficking.Among the contributions he received in1991, for his last contested race, was a $750in-kind donation of food for a fish fry fromPaul “Buddy” Johnson of Lee County. Trudealso got a $750 donation of food from JudyLittle, owner of Cotton’s Restaurant inOwsley County and wife of Willis “Cotton”Little.The next year, Johnson and Cotton Littlewere arrested at Little’s home in rural OwsleyCounty when state police and the FBI burst inand confiscated more than 100 pounds ofmarijuana.See next page