ADDICTED AND CORRUPTED - Kentucky.com

ADDICTED AND CORRUPTED - Kentucky.com

ADDICTED AND CORRUPTED - Kentucky.com

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

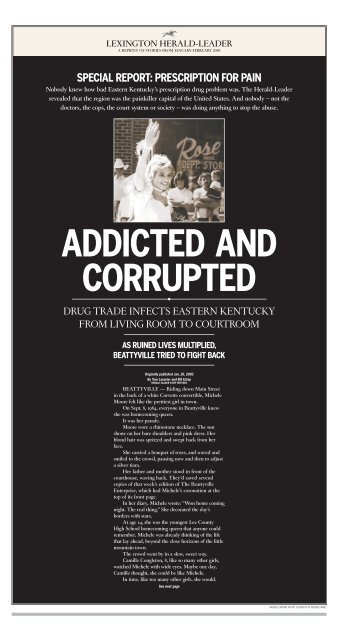

LEXINGTON HERALD-LEADERA REPRINT OF STORIES FROM JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2003SPECIAL REPORT: PRESCRIPTION FOR PAINNobody knew how bad Eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong>’s prescription drug problem was. The Herald-Leaderrevealed that the region was the painkiller capital of the United States. And nobody – not thedoctors, the cops, the court system or society – was doing anything to stop the abuse.<strong>ADDICTED</strong> <strong>AND</strong><strong>CORRUPTED</strong>◆DRUG TRADE INFECTS EASTERN KENTUCKYFROM LIVING ROOM TO COURTROOMAS RUINED LIVES MULTIPLIED,BEATTYVILLE TRIED TO FIGHT BACKOriginally published Jan. 26, 2003By Tom Lasseter and Bill EstepHERALD-LEADER STAFF WRITERSBEATTYVILLE — Riding down Main Streetin the back of a white Corvette convertible, MicheleMoore felt like the prettiest girl in town.On Sept. 8, 1984, everyone in Beattyville knewshe was home<strong>com</strong>ing queen.It was her parade.Moore wore a rhinestone necklace. The sunshone on her bare shoulders and pink dress. Herblond hair was spritzed and swept back from herface.She carried a bouquet of roses, and waved andsmiled to the crowd, pausing now and then to adjusta silver tiara.Her father and mother stood in front of thecourthouse, waving back. They’d saved severalcopies of that week’s edition of The BeattyvilleEnterprise, which had Michele’s coronation at thetop of its front page.In her diary, Michele wrote: “Won home <strong>com</strong>ingnight. The real thing.” She decorated the day’sborders with stars.At age 14, she was the youngest Lee CountyHigh School home<strong>com</strong>ing queen that anyone couldremember. Michele was already thinking of the lifethat lay ahead, beyond the close horizons of the littlemountain town.The crowd went by in a slow, sweet way.Camille Congleton, 8, like so many other girls,watched Michele with wide eyes. Maybe one day,Camille thought, she could be like Michele.In time, like too many other girls, she would.See next pageMICHELE MOORE PHOTO COURTESY OF MOORE FAMILY

PRESCRIPTION FOR PAINLEXINGTON HERALD-LEADERBEATTYVILLE COULDN’T GET HELP TO UPROOT ITS DRUG PROBLEM‘NO FAMILY’SIMMUNE TO IT’NBeattyvilleLEECO.Poverty,disabilityplagueLee CountyBeattyville sits atthe confluence ofthe <strong>Kentucky</strong> River’sthree forks; at theedge of the DanielBoone NationalForest; amid rollinghills that give wayto Eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong>’sCumberlandPlateau.POPULATIONLee County: 7,916Beattyville: 1,193EDUCATIONIn Lee County,about 30 percent ofthose 25 and olderhave less than a10th-gradeeducation.INCOMEThe gap betweenrich and poor isgreater in Lee thanin any other<strong>Kentucky</strong> county. In1999, 42 percent ofLee Countyhouseholds madeless than $15,000,and about 3.6percent made morethan $100,000.POVERTYAbout 25 percent offamilies lived at orbelow the federalpoverty level in 1999.DISABILITYAbout 40 percent ofthose older than 20report that they aredisabled.RUNNING DRY<strong>Kentucky</strong>’s largestoil field lies underpart of the county;it once providedhundreds of jobs.But production lasttopped 1 millionbarrels in themid-1980s, when200 people workedin the industry. Lastyear, the county hadonly 60 jobs in theindustry.SOURCES:2000 U.S. Census;<strong>Kentucky</strong> WorkforceDevelopmentCabinet; <strong>Kentucky</strong>Geological SurveyDAVID STEPHENSON | STAFFIn Beattyville, it’s not difficult to find someone whose family has been affected by the abuse of prescription drugs.Lawmen gone badFrom preceding pageToday, to follow the route of Michele Moore’s paradeis to tour a town of broken hearts and quietshame.To the left, there’s the office of local prosecutorTom Hall, who wears cowboy boots and likes tosmoke cigars. His stepdaughter stole from him,court records say, to buy painkillers from a man wholater pleaded guilty to dealing drugs.A couple blocks down, on the right, is the PurpleCow Restaurant, a home-cooking diner where thelocal Kiwanis Club meets. Owner Hazel Davidsonhad to post bond after her son was charged withselling OxyContin in 2001.A little farther, next to the courthouse, formerCircuit Judge Ed Jackson, 84, still keeps a law officeand knocks away on his 1950s Royal typewriter. Hiswife swore out an arrest warrant in 1997 accusingtheir daughter of assaulting her, charges she laterdropped. By court order, the girl was sent to a drugtreatmentcenter.Near the courthouse is a parking lot where policelast year said they found magistrate Ronnie PaulBegley’s son with a syringe full of an OxyContin solution.The charges were diverted on the conditionthat he join the Army.Such stories of lives undone, and many more, hadpiled high enough that by 2001, no one in town coulddeny it: Beattyville was watching its future be destroyed,one addict at a time.People started talking to one another — police,parents, business leaders and city officials.They spoke about their individual experiences,the county’s history of corrupt law enforcement and ageneral frustration with the courts.They formed a support/activist group called PeopleEncouraging People, with a mission of slowingdrug abuse.But prevention alone, they decided, was notenough.So in the cold, dark morning hours of Dec. 18,2001, Beattyville police unveiled Operation Grinch,a Christmastime drug roundup.Police fanned out across Beattyville to arrestmore than four dozen alleged drug dealers.In one visit, around 4:30 a.m., police pounded onthe door of a mobile home that sat halfway up a hillbehind the courthouse.No answer. Same thing at 8:30 a.m.Someone was inside. She just didn’t want to<strong>com</strong>e to the door.When police returned in the afternoon, theysmashed their way in. The suspect was gone.Michele Moore had fled.A few hundred yards from where she’d taken herhome<strong>com</strong>ing ride, Moore was no longer living thelife of the town darling.She was a drug addict, a single mother of two,with a sallow, acne-scarred face.After years of intravenous drug use, each ofMoore’s arms had a half-open sore, a little smallerthan a dime, with the lumpy, gray look of dead flesh.She was strung out on OxyContin and methamphetamine.Over the years she had been, in her own words,punched and kicked “like a man” in front of her children.The police were carrying a warrant for Moore’sarrest on a charge of selling methamphetamine. Sheturned herself in three days later and pleaded notguilty. (The substance turned out not to be methamphetamine— Moore had allegedly ripped off the undercoverbuyer — and the charge was later amendedto a misdemeanor.)Inside her mobile home, she had taken down herhigh school photographs.“I couldn’t look at my pictures, to look at what Iwas and what I’d be<strong>com</strong>e,” she said.Moore says she has been to drug treatment threetimes since her arrest in December 2001.Her future, like Beattyville’s, remains very muchin doubt. As for the sores, it’s hard to tell how muchthey’ve healed.In planning Operation Grinch, Mayor CharlesBeach III sought help from the <strong>Kentucky</strong> State Police,often a key force in rural drug operations.See next pageCHARLES BERTRAM | 1991 STAFF FILE PHOTOBeattyville Police Chief Omer Noe walked into U.S. DistrictCourt in London. In 1990, he was arrested during a federaldrug bust, along with Lee County Sheriff Johnny Mann.ED REINKE | ASSOCIATED PRESS FILE PHOTOLee County Sheriff Johnny Mann, right, was arrested in 1990during an FBI investigation. Authorities said he and Omer Noereceived money to protect drug shipments.CHARLES BERTRAM | 1994 STAFF FILE PHOTOLee County Sheriff Douglas Brandenburg was arrested on drugcharges. In 1995, he was sentenced to nine months in prisonafter pleading guilty to obstructing a drug investigation.

PRESCRIPTION FOR PAINLEXINGTON HERALD-LEADERPHOTOS BY DAVID STEPHENSON | STAFFMichele Moore talked about how her life has gone since she was crowned Lee County High School’s home<strong>com</strong>ing queen in 1984. She said she has been to drug treatmentthree times since December 2001. She took down her high school photographs. “I couldn’t look at my pictures, to look at what I was and what I’d be<strong>com</strong>e,” she said.BANK LOAN PAYS FORTOWN’S DRUG BUSTFrom preceding pageBusy with its own cases, KSP didn’t get involved.Beach went to the federal Drug EnforcementAdministration, as well, but came away emptyhanded.The agency decided that Beattyville’s problemsdidn’t involve the type of gang activity or violentcrime required for sending a street-level enforcementteam.The city was forced to devise, execute andeven fund its own large-scale crackdown — unusualsteps for a town of its size.Beach didn’t want to go solo, but he said heunderstood other agencies’ reluctance to partnerwith local police.“The credibility of law enforcement in LeeCounty left something to be desired,” Beach saidrecently.In 1990, the FBI had busted Lee County SheriffJohnny Mann and Beattyville Police ChiefOmer Noe for taking money to protect shipmentsof cocaine and marijuana.Authorities said Mann received $44,000 inpayoffs and even deputized two FBI agents whowere posing as drug traffickers. He and Noe wereconvicted of taking bribes.In 1995, Sheriff Douglas Brandenburg was sentencedto nine months in prison after pleadingguilty to obstructing a drug investigation. Witnessestestified that Brandenburg was getting$1,000 a month to protect drug shipments.Given that history, “we had to prove ourselves,”said Beattyville police Officer Matt Easter,who went from directing traffic outside the elementaryschool to coordinating drug buys.Step one was to round up some money. Beattyville’s$500,000 general fund couldn’t begin topay for a major sting operation.So Mayor Beach persuaded the city council totry an alternative. Beach’s family controls the localbank, Peoples Exchange Bank, which agreed toextend a line of credit to the city.The cash was advanced a few thousand dollarsat a time over several months. By the end, Easterand his partner, Capt. Joe Lucas, would spendsome $15,000 on the bust.Easter and Lucas were natural partners. Thepair had been buddies ever since Easter joined theLee County Volunteer Fire Department as a highschool student. There he met Lucas, 13 years hissenior.“He’s sort of like a second father,” said Easter,who with his military crew cut resembles a skinnierversion of Lucas.Neither officer had done undercover work before.They got a state police detective to givethem a crash course.The three of them sat in an unmarked statepolice car in the parking lot of the Save-A-Lotand went over the right way to document a drugbuy, how to set up tape recorders and other details.Afterward, Lucas and Easter went back totheir office, called an electronics <strong>com</strong>pany and orderedthe same kind of recorder the state policeuse. They also typed up an evidence form modeledafter one the detective gave them, substituting“Beattyville Police” where it said “<strong>Kentucky</strong>State Police.”It’s too simple to say all the bad things startedfor Michele Moore on the day in 1994 when sheran into the mayor’s cow.Most of the pain, and medication, came afterthat, but tragedy had already visited: Michele’sfather, Jesse Moore, died of a heart attack in1991.Jesse Moore was the longtime property valuationadministrator for Lee County. A formerteacher in Lee and Owsley counties, he was a pillarof the <strong>com</strong>munity.More important, Jesse Moore’s daughter“The credibility of law enforcementin Lee County left something to be desired.”Charles Beach IIIBeattyville mayoradored him. For years, Michele sang at countyfairs. If her father was in the crowd, she’d alwaysdo Daddy’s Hands just for him:I remember Daddy’s handsFolded silently in prayerAnd reachin’ out to hold me,When I had a nightmare.After he died, “I died inside, I guess,” she recalled.The next year, 1992, Moore left the husbandshe’d married at 19 and moved to Lexington.A licensed beautician, she got a job at Supercutsduring the day and worked at a bar a fewnights a week. There was some partying — shetried cocaine a few times and didn’t like it — butnothing that was too far over the top, Mooresaid.Then, on a weekend trip back to Lee Countyin 1994, she drove into a cow owned by MayorBeach. Moore herniated a disc in her back andwas prescribed painkillers.Within a year, she was hooked, she said.Moore’s daughter, Cheyenne, was born in1996. Soon after, Moore’s relationship withCheyenne’s father ended, and she went back toLee County in 1997. She was pregnant with herson, Dylan, within a few months.The prescription drugs had be<strong>com</strong>e a seriousproblem. “By ’98, when I had Dylan, I was justeating them,” she said.She tried cocaine again and liked it better thistime. In a while, it was on to methamphetamine.Along the way, Moore said, she was beatenmany times. Once, when she was eight monthspregnant, a man threw her to the floor and helda shotgun to her head, she said.Still, she said, she didn’t feel she had manyoptions. “There’s nothing to do. This is Beattyville,”Moore said. “I <strong>com</strong>e back to the sameold hole.”The Grinch came for her in 2001.Officer Easter and Capt. Lucas found it wasn’teasy trying to run a drug sting in a smalltown.The Beattyville Police Department, with astaff of five, couldn’t spare them for full-timedrug work. So Easter and Lucas would spendhours on accident reports and routine arrests,only to get off shift and then start Grinch duty.Much of the extra time was unpaid, the two said.There were some difficulties along the way. Afew times when Easter met informants on somesmall country road, sitting in a city police car,people spotted them.If word got around that a drug buyer was meetingwith the police, the secrecy of the sting wouldbe ruined. Gossip travels fast in a small town.“We were in the middle of nowhere, and Ithought nobody would drive by. Well, they did,”Easter said. “And you’re wondering, ‘Did we justget caught?’”Once, during the middle of the investigation,the town’s drug problems came un<strong>com</strong>fortablyclose. Lucas’ sister, Yvonne Lucas Angel, a dispatcherfor police and emergency services, wasarrested by state police on charges of conspiracyand <strong>com</strong>plicity to sell OxyContin, and conspiracyto sell Tylox.An indictment said she and another defendanttraded drugs for a stolen police radio, an IOU anda dog. The drug charges were dismissed; under aplea agreement, she pleaded guilty this month to<strong>com</strong>plicity in receiving stolen property.“No family’s immune to it,” Joe Lucas said.The first Grinch undercover buy was in June2001: four bags of poor-quality cocaine, totalingone gram, for $100.Over the next five months, police said, informantsmade 85 more purchases. The list of allegeddealers grew to eight pages; it includedsales of methamphetamine, cocaine, marijuana,Lortab, Xanax, OxyContin and other drugs.The purchases continued through late November.“We could have kept right on going andgot twice that much,” Lucas said.In December, when it came time to start arrestingpeople, state and federal agencies finallysent some help: about a half-dozen officers.Police set up a booking area at the fire stationon Dec. 18, <strong>com</strong>plete with a poster of the meanone, Mr. Grinch. They ran the operation therebecause the police station — located in a renovated1868 house — was too small for the rushof officers and accused drug dealers.Carl Noble, one of those arrested, said thescene was “kind of like going to a high schoolballgame. It was crowded.”Lexington television and newspapers acrossthe state covered the big bust. Beach accepted congratulations,shaking hands and slapping backs.Beattyville police Officer Matt Easter, left; Commonwealth’s Attorney Tom Hall, gesturing; and state trooperand former Beattyville officer Joe Lucas, foreground, waited in court during a case from Operation Grinch.Drugs in this seriesLORCET, LORTAB <strong>AND</strong> VICODIN(clockwise from left)For relief of moderate to moderatelysevere pain. Made from hydrocodone,with aspirin or acetaminophen.Overdose dangers: Slow, shallowbreathing; drowsiness leading to <strong>com</strong>a;liver damage; in extreme cases, cardiacarrest and death.Street price: $6-10 per pill.OXYCONTINPrescription drug for continuing reliefof long-term, moderate to severe pain.Made from oxycodone, with atime-release mechanism that itsaddicts disarm by crushing pills.Overdose dangers: Abnormally slowheartbeat and low blood pressure;drowsiness leading to <strong>com</strong>a and death.Street price: About $1 per milligram.Doses range from 20 to 80 milligrams.TYLOXPrescription drug for relief of moderateto moderately severe pain. Made fromoxycodone and Tylenol.Overdose dangers: Depressedbreathing; drowsiness leading to <strong>com</strong>aand death; liver damage.Street price: Increasingly rare,about $20 a pill.VALIUM, XANAXFor managing anxiety disorders andshort-term relief of anxiety; Xanax alsorelieves panic disorders. Side effectsinclude drowsiness and fatigue.Overdose danger: Confusion,<strong>com</strong>a, diminished reflexes;with Xanax, risk of death.Street price: $1 to $2 per Valium;$3 to $4 per Xanax.METHAMPHETAMINEWhite powder or clear, chunky crystalscooked in illegal labs; base ingredientis pseudoephedrine, a decongestant.Dangers: Can cause psychotic behavior;brain damage similar to Alzheimer'sdisease; stroke; and epilepsy.Street price: $100 a gram.COCAINEDangers: Powerfully addictive.Cocaine-related deaths are usuallycaused by cardiac arrest or seizures,followed by respiratory arrest.Street price: $100 a gram.MARIJUANADangers: Possible frequent respiratoryinfections; impaired memory andlearning; increased heart rate; anxiety;and panic attacks.Street price: Mexican marijuana sells forup to $1,100 a pound; <strong>Kentucky</strong>-grownmarijuana sells for about $2,200 apound if it’s grown outdoors or up to$3,200 a pound if it’s grown indoors.

PRESCRIPTION FOR PAINLEXINGTON HERALD-LEADERBeattyville police officer Matt Easter, left; prosecutor Tom Hall; BeattyvilleMayor Charles Beach III; and <strong>Kentucky</strong> State Trooper Joe Lucas listenedto a guilty plea in Lee Circuit Judge William Trude Jr.’s chambers.PUSHING FOR JUSTICE◆WHEN DRUG CASES FINALLY REACH COURTIN BEATTYVILLE, THERE ARE NO GUARANTEESOriginally published Jan. 27, 2003By Tom Lasseter and Bill EstepHERALD-LEADER STAFF WRITERSBEATTYVILLE — Mayor Charles BeachIII had just begun to savor Operation Grinch,a major drug bust by his police department,when the phones started to ring.With the defendants behind bars, a groupof citizens was making calls, sending e-mailand knocking on doors throughout Beattyville.Come to court on Dec. 21, 2001, callerssaid. Help make a show of force.The group, People Encouraging People,was formed to fight substance abuse in thetown. Its members wanted the judge and theprosecutor to know they supported tough sentences,said Lynda Congleton, who helpedcreate PEP.When the day arrived, and indictmentswere presented, nearly 40 friends and neighborsjoined Mayor Beach and Congleton inLee Circuit Court.Beach surveyed the scene and said, “Ithink the rest of the story will be how thecourts deal with these cases.”Circuit Judge William W. Trude Jr. wasnot impressed.“When you get 100 people up there sittingin the courtroom trying to put pressure onthe court, you’ve got a problem,” Trude saidrecently. “I think they were trying to intimidateme, and if I let that happen, what kind ofjudge am I?”Congleton, Beach and others assembledthe crowd out of fear that the Grinch bustwould end in little more than dismissals andprobation. That sort of thing had happenedbefore — usually because prosecutors agreedto plea bargains or had questions about thequality of police evidence.Also, some in Beattyville feared whatTrude, who by his own admission has hadpersonal contact with drug suspects, might dowith the cases.The stakes were high for Beattyville, andthe small Eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong> <strong>com</strong>munity wasno longer keeping quiet.Operation Grinch had its roots in outrage— outrage Beach and others felt as theywatched drugs crawl up from the streets intopolite society.In Lee County, census data show, the gapbetween rich and poor is greater than in anyother <strong>Kentucky</strong> county.For people in Beattyville, one aspect of thedivide is clear: You live either at the top of thehill, or at the bottom.At the top are people like Mayor Beach,whose family controls the town bank, PeoplesExchange Bank. He resides in an affluent enclavecalled Gourley Heights and keeps a$500,000 home in Lexington.Then there are those who live in mobilehomes with trash in the yard, like the one atthe bottom of Beach’s hill, which he passesdaily in his BMW.For decades, the embarrassment of drugaddiction simply had not climbed the hill.That changed during the 1990s.“You started seeing how rampant it was,”said Lynda Congleton, whose husband, TerryCongleton, runs a large family business, includinga hardware store that began in 1921.One of Lynda Congleton’s stepdaughters,Camille, was a little girl in 1984, whenMichele Moore was crowned Beattyville’shome<strong>com</strong>ing queen. Camille recalls standingin the crowd, watching the parade. She wantedto be just like the queen.Moore was charged in the Grinch operationwith trafficking drugs, just like 48 otheralleged dealers.Camille Congleton grew up to join a groupof kids of Beattyville elite who began usingdrugs during the 1990s. Another, whose drugtreatment is documented in court records,was Cherry Jackson, the daughter of a formercircuit judge.Jackson peeled away in a red Camaro in responseto an interview request.During high school, Camille Congleton recalled,the group “just ruled the school upthere.”PHOTOS BY DAVID STEPHENSON | STAFFTrude talked with attorneys who are involved in an Operation Grinch case. Trude says he has hadpersonal contact with drug suspects outside the courtroom.“The way we wanted it,” she said, “wasthe way it was.”Today, Congleton lives in a mobile home inLee County and says she no longer usesdrugs. As she sat on the sofa with herboyfriend last month and spoke about her life,Congleton’s eyes got wet.“Look at what I could have had, and lookat what I am. I will never get that back,” shesaid.Her experiments with drugs started as flirtation,she said. By the end, she saw a lot ofugly things.“There’s a lot of being taken advantage of.Pill dealers think they have this power overyou,” Congleton said. “They say, ‘I’ve gotwhat you need. What are you willing to do forit?’”She shifted around on the sofa andchanged the subject.When talking about the young women,Mayor Beach looks un<strong>com</strong>fortable, too. Itwasn’t until his friends began having problemsin their families that he realized somethingneeded to be done, he said.“That’s really where my passion camefrom,” Beach said.Jennifer Burgess, a friend of Beach’sdaughter, often came over after school whenshe was younger.Burgess, the daughter of a local schoolboard member, was arrested in 1999 and accusedof forging one of her father’s checks.The case was dismissed, but only after LarryBurgess told the judge that his daughter wasaddicted to Tylox and Xanax. She was sent toa drug-rehabilitation center.“This child grew up in our house. She wasbeautiful and smart as hell,” Beach said.Jennifer Burgess declined to <strong>com</strong>ment,saying she didn’t want to embarrass her family.Others also suffered the pain of a child’saddiction.In 1997, prosecutor Tom Hall’s wife,Karen, submitted a statement during the sentencingof a drug dealer. Karen Hall said thedealer sold Tylox to her daughter, Lyn Pelfrey.Pelfrey wouldn’t <strong>com</strong>ment for this storybeyond saying she’s clean these days. Sheadded that the drug problem is worse in Beattyvillethan it has ever been. “They just needto stop it,” Pelfrey said. “It’s crazy. It’s killingpeople.”Karen Hall wrote in the statement thather daughter traded the dealer $2,000 worthof jewelry — presents she had received fromher parents and grandmother on her 16thbirthday and other occasions. Pelfrey alsohocked $800 worth of her sister’s jewelry andstole money from the family, her motherwrote.The Halls eventually had Pelfrey arrestedto force her into treatment, according toKaren Hall’s statement. “A part of me diedthat day.”“When you give birth to a child, you wantonly the best for that child and you work sohard to attain that,” Karen Hall wrote. “Whenyou have to face the fact that your child is adrug addict, it tears your heart out …”The man who allegedly sold drugs to Hall’sdaughter was arrested in a drug operation in1995.Few of the accused in that roundup weresentenced to prison — which made some inBeattyville apprehensive about the local justicesystem.Fifteen cases made their way through LeeCircuit Court; 11 were probated. One was dismissedafter the defense cited insufficient evidenceand the prosecution agreed. Under aplea deal, another defendant got seven weekendsin jail.Two cases went to trial. In one, the juryre<strong>com</strong>mended that Frankie Brandenburg, theman accused of selling to Hall’s daughter,serve 15 years. Judge Trude gave him 10.(The charges were dismissed three years later,after the <strong>Kentucky</strong> Court of Appeals overturnedthe verdict. By then, Brandenburg wasout on parole.)In the other trial, a defendant chargedwith selling Tylox was sentenced to eightyears. But after the defense asked for shockprobation — a request that the prosecutorsaid he opposed — Judge Trude freed the defendantin less than 11 months.Trude, who has been on the bench formore than a decade, says it’s unfair to pin thelack of prison time on him or any other judge.Several factors — from weak police workto ineffective prosecution — can get casesthrown out, he noted, but the public sees it aslight punishment for drug criminals.A 1997 roundup was little different. Of 12people facing drug-dealing charges in circuitcourt, eight got probation as a result of pleabargains.“A lot of times, you have to <strong>com</strong>promise thecase by going for a plea for probation just toavoid trial,” said prosecutor Tom Hall. “Becauseyou know if you go to trial, you’re going to lose.”Prosecutors were pushed toward cuttingplea deals for the ’97 defendants when aninformant began signing statements sayingshe would not testify.Also of concern, according to court records,was that some grand-jury proceedings were notrecorded, and in at least one case, undercoverpolice tapes “simply had music on them.”The lone defendant who had to servetime?Frankie Brandenburg, the same man whohad been accused of selling drugs to TomHall’s stepdaughter. His 10-year sentence wasrun alongside his 1995 case.The mishaps behind the dismissals andmost of the probations were beyond Trude’scontrol, but it’s clear that some people inBeattyville don’t have much confidence in thejudge.Even Trude acknowledges the persistenttalk in his circuit that he associates with drugdealers, and rumors that he himself usesdrugs.“I hear it about myself. I hear it abouteverybody. It’s just a perception they have,”Trude said in an interview this month. “Idon’t know what to do about that.”One reason for the rumors, Trude says, isthat he collects agate, a semi-precious stone.The people who <strong>com</strong>e over to his house toshow him rocks have included some who solddrugs in the past, he said.“But that doesn’t bother me,” Trude said.“They’re not out there selling me drugs.They’re not selling drugs now, as far as Iknow. I don’t critique people who sell agate.All I do is buy the rocks.”Just last month, in a deposition, a longtimefriend of Trude’s testified that he knewthe judge had used drugs.“Judge Trude and I were friends for a numberof years and I know a lot about his drughabits and I can prove them all,” said OlinEstes, who had served as one of Trude’s trial<strong>com</strong>missioners.That testimony came as part of Estes’ bitterdivorce from his former wife, TammyEstes. Trude said a big factor in the acrimonyis that Tammy Estes now lives with him.The judge denied Olin Estes’ allegationand said that he’s contemplating filing suitagainst his former friend.“If he’s got proof of anything like that, heneeds to bring it out,” the judge said.“Hell, I’ll go take a test today, tomorrow orwhenever you want,” he said.Trude also said that he once asked a formergirlfriend to leave his house when he discoveredher cocaine on his kitchen floor.In the past, Trude has taken campaigncontributions from people who later madeheadlines for ties to drug trafficking.Among the contributions he received in1991, for his last contested race, was a $750in-kind donation of food for a fish fry fromPaul “Buddy” Johnson of Lee County. Trudealso got a $750 donation of food from JudyLittle, owner of Cotton’s Restaurant inOwsley County and wife of Willis “Cotton”Little.The next year, Johnson and Cotton Littlewere arrested at Little’s home in rural OwsleyCounty when state police and the FBI burst inand confiscated more than 100 pounds ofmarijuana.See next page

PRESCRIPTION FOR PAINLEXINGTON HERALD-LEADER“WHAT I HOPE HAPPENS IS WE HAVE AHEALTHIER COMMUNITY,” SAID LYNDACONGLETON, WHO HELPED START AGROUP TO FIGHT SUBSTANCE ABUSE.PHOTOS BY DAVID STEPHENSON | STAFFCamille Congleton was among a group of children of the Beattyville elite who began abusing drugs during the 1990s. Today, she laments what she could have been and what she has be<strong>com</strong>e.COURT’S PAST LEADS TO FEARFrom preceding pageThe pair pleaded guilty to drug charges.During a trial in 1994, a key prosecution witnesstestified that Johnson paid former LeeCounty Sheriff Douglas Brandenburg to protecthis drug business. Brandenburg laterpleaded guilty to obstructing a drug investigation.Little and Johnson declined to <strong>com</strong>ment.Trude said that after the men were arrested,he went to state police and volunteeredthat they had made the contributions.“They never offered me anything; theynever asked for anything,” said the judge,who also said, “You certainly can’t run a courtsystem doing favors for people.”Trude said he was unaware of the men’scriminal connections during his campaign.But another of his 1991 contributors had runafoul of the law before he gave to the candidate.In 1989, Estill County car dealer Delmus“Bunt” Gross was sentenced to five yearsfor laundering drug money through his carlot.Then in October 1991, while appealing hisconviction, Gross provided two dressed hogsworth $355.50 for another Trude fund-raiser,according to finance records.Gross recently said he didn’t rememberbuying the hogs but conceded that he mighthave.Trude said he probably knew aboutGross’s conviction at the time. “Obviously, ifit bothered me I wouldn’t have taken thepigs,” he said.Despite concerns about the past, Beattyvillepolice Capt. Joe Lucas was expectingbig things from the drug cases he had builtwith Officer Matt Easter.“When I went into this, we had high hopesof getting a lot convicted and gone, getting alot of the drug dealers off the street,” said Lucas,who has since moved on to a job with thestate police.“I was hoping to actually clean up ourcounty fairly quick, but they’re still out heredoing it,” Lucas said.Of the 49 Grinch defendants, only twohave gone to trial, and the out<strong>com</strong>es sentmixed signals. The jury re<strong>com</strong>mended sevenyears in one. The other ended in mistrial.In the mistrial case, Sharon Bray was facingtwo counts of selling Lortabs. Her casewas the first to go to trial, and she said herlawyer said “they were going to make an exampleout of me.”Last June, three jurors were not convincedby a tape of Bray allegedly arranginga drug deal and taking money. Police and aninformant also testified that Bray solddrugs.A new trial is scheduled for next month.“It was like, we’ve just wasted countlessmoney and countless hours,” Easter said. Hewas in the courtroom when the verdict, orlack thereof, was read.Two other Grinch offenders pleadedguilty in district court. Each was given ayear, but 335 days of that were probated,leaving just 30 to serve. And one case wasdismissed when the drugs, thought to bemorphine, turned out to be some other substance.In three other Grinch cases, prosecutorsarranged plea deals that are unusually toughfor drug cases in Lee County: two for fiveyears in prison, the other for six.Hall said he intends to oppose any motionsfor shock probation in those cases —though his opposition doesn’t always matter,he acknowledged. “If they get it, it’s not goingto be with my blessing,” he said.In a pending case, a potential problem forthe prosecution surfaced. In it, Trude suppressedthe testimony and undercover tapesof one of the main informants for Grinch aftera special prosecutor failed to produce medicalrecords.The defense was entitled to records fromany institutions where the informant hadbeen treated for psychological disorders “sothat this Court can determine her <strong>com</strong>petencyto testify as a witness,” according to acourt order.With 41 cases to go, it remains to be seenwhat kind of message the courts’ handling ofthe Grinch cases will send about drug chargesin Lee County.One defendant, Carl Noble, who was arrestedduring Grinch on charges of sellingmarijuana and Lortab, doesn’t seem too troubled.“I could’ve sold some (marijuana), but notno pills. They just made that up,” Noble said.He has had four drug-related charges dismissed,probated or thrown out since 1993.While showing a visitor the three marijuanaplants in his front yard last summer,Noble ran his hand up a stalk and offered thepungent smell on his fingers as proof of quality.Is it a bad idea for a man charged withtrafficking the stuff to be showing it off in hisyard?Noble shrugged. “Well,” he said, “it’s just a$100 fine and $82.50 court costs.”Since Beattyville first began grapplingwith the issue, it has had some successes infighting drugs.Mayor Beach spearheaded the constructionof a mental health counseling center,which will offer substance-abuse treatment.He hopes that it will eventually feature residentialcare.Judge Trude is mulling the idea of a drugcourt program that would help him monitoroffenders more closely.And the PEP group has won hundreds ofthousands of dollars in grants for its programsto try to keep young people from gettinginto trouble with drugs.“What I hope happens is we have a healthier<strong>com</strong>munity,” Lynda Congleton said. “It’snot impossible if we pull together.”As for Michele Moore, 18 years after herhome<strong>com</strong>ing parade, she still lives in LeeCounty. Until a couple of weeks ago, she wasstaying in a small house with particleboardceilings and junk cars in the yard.Mounds of dirty clothes and trash litteredthe home. There was a pile of tools and carparts on the kitchen floor.On Jan. 10, Moore moved back into herold mobile home, the same one she was inwhen the police came for her during OperationGrinch in 2001.Her mother, Patty, also still lives in thecounty but is trying to sell her house.“I feel like I’m a prisoner in my own home,and my life. I’m embarrassed to go out, andI’m bitter,” Patty Moore said. “I don’t even dogrocery shopping or go into town anymore …I feel like they’re looking at me and tellingeach other, ‘Do you know Michele is a drugaddict?’”Grinch wasn’t the end of Michele Moore’slegal troubles. Last March, state police arrestedher on charges of selling what she said wasmethamphetamine. As in the Grinch case, itlater turned out not to be.Also in March, Beattyville police chargedMoore with making a false report by sayingthat her home had been burglarized. Policesaid she had been seen selling the items shereported missing.About four months later, she was chargedwith forging her aunt’s signature on checksthat were allegedly stolen.Moore is scheduled to stand trial in LeeDistrict Court in a couple months for thestate-police bust and false-report charge.In the entry to the courthouse, there’s aplaque that hangs in honor of Jesse Moore,the county’s former property valuation administrator,who died in 1991.Carved on the plaque are the words, “Fatherof Michele Moore.”It’s hard to say whether his daughter willstop in front of his picture and read the manyac<strong>com</strong>plishments listed below. “Sometimes Ican’t even look at him,” she said.Whatever passes through her mind,Michele Moore, once the future of Beattyville,probably won’t linger before walking upstairs,to the courtroom.She will be there, after all, to answer forwhat she has be<strong>com</strong>e.Since March, Michele Moore, Beattyville’s former home<strong>com</strong>ing queen, has been charged with traffickingwhat she said was methamphetamine; making a false report to police; and forging her aunt’s checks.Moore is scheduled to stand trial in March for charges in the trafficking bust and the false-report charge.

PRESCRIPTION FOR PAINLEXINGTON HERALD-LEADERA LACK OF INTEGRITY, MONEY <strong>AND</strong> UNITY LIMITS INVESTIGATION OF DRUG OPERATIONS◆H<strong>AND</strong>CUFFING ENFORCEMENTShortages of cash,manpowerplague policeOriginally published Jan. 29, 2003By Bill Estep and Tom LasseterHERALD-LEADER STAFF WRITERSMCKEE — When police in JacksonCounty investigated two people last Auguston suspicion of selling drugs, Sheriff Tim Feesaid he forked over $80 of his own money soan informant could buy two OxyContin pills.That helps explain why there’s not moredrug enforcement in rural <strong>Kentucky</strong>. Manysheriffs’ offices don’t have the money or manpowerto do much of it.The <strong>Kentucky</strong> State Police has only twodozen officers specifically assigned to druginvestigations for 56 Eastern and Southern<strong>Kentucky</strong> counties.“It’s really, really slim,” said state policeMaj. Mike Sapp. “To properly enforce thedrug problem, we would need to at leasttriple the amount of people.”Instead, the agency is 64 officers short ofits budgeted strength.Meanwhile, the FBI has been consumedwith <strong>com</strong>bating terrorism, which shifts attentionand staff away from drugs, and the U.S.Drug Enforcement Administration focuses onlarge drug organizations, not street-level dealers.The bottom line: The size of the drugproblem exceeds the troops to fight it.Though the numbers fluctuate, <strong>Kentucky</strong>has ranked near the bottom in the nation in thenumber of sworn police officers per capita, accordingto the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics.In 1997, only two states had a lower rateof police officers in state and local departments.<strong>Kentucky</strong> had 15.5 officers per 10,000residents, ranking ahead of only Vermont andWest Virginia.By 1999, the most recent year for such data,the figure was 17.6 officers per 10,000 residents,which ranked <strong>Kentucky</strong> ahead of 10other states.Heavy workload for sheriffsSheriffs wear a lot of hats in <strong>Kentucky</strong>.They’re responsible for collecting taxes, transportingprisoners, providing court securityand serving court papers, such as summonses.Combine that with meager funding andbig areas to cover, and few are able to dodrug investigations that require extended surveillanceor expensive drug purchases.“The sheriffs are very limited in whatthey can do,” said former Letcher CountySheriff Steve Banks, who left office thismonth. Banks said he had five full-time andtwo part-time deputies to cover a county ofmore than 25,000.Jackson County’s Fee said he wants drugsoff the street, but money for investigators’drug buys often <strong>com</strong>es out of his pocket. “Aman suffers from financial pneumonia” doingthat, he said.In Lee County, which covers 210 squaremiles, Sheriff Harvey Pelfrey said he and hislone deputy rely on volunteer special deputiesfor help. “It keeps me busy just doing … paperworkand transports,” Pelfrey said.The state police are “strapped like everyoneelse,” said Col. Rodney Brewer. Whilethe state has authorized 1,020 officers, theagency has only 956. Brewer said 11 of thoseofficers have been called to military duty.The state police made a number of moveslast year to beef up drug enforcement, suchas setting up a system to better share informationamong officers. At each regional post,a detective was assigned to be a street-leveldrug investigator. The agency also expandededucation efforts against drug abuse.The changes came as a report by the statepolice and the National Drug IntelligenceCenter was making clear that <strong>Kentucky</strong>’sdrug problem “has exceeded the resources oflaw enforcement officials.”“Abuse of certain types of drugs is so pervasivethat effective law enforcement and preventionefforts prove extremely difficult,”said the report, released in July.FBI focuses on terrorismThe FBI has long played a key role in <strong>Kentucky</strong>drug investigations, especially cases involvingpolice corruption related to drugs. Theagency investigated the largest such case instate history, charging four Eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong>sheriffs, a deputy and a police chief in 1990with taking payoffs to protect drug runners.Because it can severely damage the qualityof life in <strong>com</strong>munities, public corruptionremains a top priority for the FBI, said J.Stephen Tidwell, special agent in charge ofthe FBI in <strong>Kentucky</strong>.Since Sept. 11, 2001, however, the FBIhas shifted resources to deal with terroristthreats. The agency has fewer agents in Eastern<strong>Kentucky</strong> now than before the attacks, althoughofficials declined to say exactly howmany agents it has in the state.Tidwell said there was a time when theagency could put other matters on the backburner, if necessary, in order to concentrateresources on investigating a large drug organization.“Now we’re not in the position to do thatas much as we’d like to,” Tidwell said.DAVID STEPHENSON | STAFFIn October, Clay County sheriff’s deputies Rick Wagers, left, Paul Whitehead and James Sizemore charged James Roberts with use or possession of drugparaphernalia. Roberts pleaded guilty and was fined $25, plus $130.50 in court costs.FEDERAL MONEY FAILS TO UNITE POLICE AGENCIESOriginally published Jan. 29, 2003By Bill Estep and Tom LasseterHERALD-LEADER STAFF WRITERSLONDON — Over the past five years, Congresshas approved $30 million for a programthat was supposed to meld federal, state and localpolice into one cooperative force to attackdrugs in Southeastern <strong>Kentucky</strong> and parts ofeast Tennessee and West Virginia.That hasn’t happened.■ Turf fights have sometimes gotten in theway, as one police agency avoided sharing informationwith another.■ The history of bribery and corruptionamong local lawmen has made state and federalpolice reluctant to share confidential informationwith local cops.“That is just not possible in some Eastern<strong>Kentucky</strong> counties, because of corruption,” saidDave Gilbert, a former deputy director of theprogram.■ Though money flowing through the AppalachiaHigh Intensity Drug Trafficking Areaprogram, called HIDTA, has paid for some expensiveequipment, member agencies have attimes used the money for their own work outsidethe target area, a former member of itsboard said.There’s no question the program has boostedthe fight against drugs in the sprawling areait covers.Agencies working under HIDTA haveseized millions of dollars worth of drugs andhundreds of weapons. They’ve cut and burnedmarijuana worth an estimated $5 billion in aneradication program one federal official called“second to none in the country.” And HIDTAmembers have arrested more than 6,000 peoplesince the program started in 1998, according toits annual reports.But some local agencies <strong>com</strong>plain they’veseen little of the money. And funding for oneleg of the program — an effort to interrupt theflow of drugs by stopping couriers on the highways— was frozen in 2002 after federal officialssaid it wasn’t working well.Changes aimed at addressing the problemsare under way. But police across Southeast <strong>Kentucky</strong>acknowledge that the illegal drug tradehas grown quickly over the past several years,and their side has some catching up to do.Federal money helpsIn 1998, an area centered on Southeast <strong>Kentucky</strong>became a HIDTA — that is, an area ofhigh-intensity drug trafficking. There are now28 such areas.The region’s enduring status as one of thefive largest marijuana-producing states in thecountry helped it win that designation. Theconsiderable influence of Republican U.S. Rep.Hal Rogers, who represents much of Eastern<strong>Kentucky</strong>, also played a role.Without HIDTA, the federal Drug EnforcementAdministration probably wouldn’t haveseveral agents stationed in Laurel County. TheU.S. Forest Service wouldn’t have extra officersto prowl for pot patches. And the Internal RevenueService and the federal Bureau of Alcohol,Tobacco and Firearms wouldn’t have extraagents in rural <strong>Kentucky</strong> to investigate moneylaundering and gun crimes related to drugs.HIDTA’s headquarters in London includesan intelligence center to help police. The programalso brings money for increased prosecutionin state and federal courts.But the core of the HIDTAconcept —bringing federal, state and local police togetherto share information and target drug traffickers— hasn’t <strong>com</strong>e to pass.For example, one goal of the program iscalled “co-location” — getting police from eachagency moved into the same office to share information.Though HIDTArents office space inJoining forcesThe Appalachia HIDTA was designated in 1998 totarget marijuana in 65 counties, primarily in Southeast<strong>Kentucky</strong>, East Tennessee and West Virginia. Ithas since expanded to 68 counties, shown below,and switched its focus because of growing problemswith drugs such as prescription narcotics andmethamphetamine.REPORT DRUG TRAFFICKINGThe Appalachia High Intensity Drug Trafficking AreaTask Force has a tip line where people can reportsuspected drug activity. The toll-free number is866-424-4382. Reports can be madeconfidentially.Tennessee<strong>Kentucky</strong>WestVirginiaCountiescoveredby HIDTAdowntown London for $150,000 a year, not allthe participating agencies keep officers there.Member agencies say it has been difficult to getall the agencies together, in part because of alack of space, and because they cover such alarge rural area.The program has been a financial boon forparticipating agencies, which include the FBIand DEA, several state-level police agenciesand the National Guard.For the last fiscal year, state-level policeagencies requested more than $750,000 fromHIDTA to pay officers overtime.Agencies have also put in for hundreds ofthousands of dollars to lease vehicles and buyhigh-tech surveillance and <strong>com</strong>municationsequipment. The West Virginia Public SafetyCommission, for instance, asked for seven mobile<strong>com</strong>munication systems at $7,728 each. The<strong>Kentucky</strong> State Police sought two $3,000 nightvisionmonoculars. And the U.S. Forest Servicerequested cameras that cost $7,300 each.HIDTA Director Roy Sturgill said mostsuch budget requests have been honored.But local police departments say little moneyhas trickled down to them. Harlan CountySheriff Steve Duff said his office got about$5,000 in overtime funding over the past threeyears through HIDTA.“Where they’re lacking with locals is they’renot giving us enough funding,” Duff said.Col. Steve Lundy of the Corbin police saidHIDTA once offered the department $4,000.That would have paid an officer to work only afew hours a week to investigate drug couriers,he said.“It’s too limited to do anything with drugtraffic,” Lundy said.Some police said they hadn’t seen much ofan effort to bring local police into investigations.“We expected more of a cooperative typething,” said Todd Roberts, assistant police chiefin Manchester.Glen Thomas, who recently retired as a lawenforcementsupervisor for the U.S. Forest Serviceand was on the HIDTA executive board,said the board urged local police to apply forfunding by submitting specific plans, but gotlittle response.Misdirection of fundsThe Appalachia HIDTA faced the first <strong>com</strong>prehensivereview by its parent agency lastsummer. The federal Office of National DrugControl Policy declined to release findings fromthe review, saying the document wasn’t final.But several people who saw results of the reviewsaid it raised questions about whetherparticipating agencies were using the programto boost their budgets and continue their ownwork, rather than <strong>com</strong>ing together to multiplyeffectiveness.The review noted concerns that investigativeagencies weren’t sharing information.Some agencies had used HIDTA-fundedequipment, such as cameras, drug-sniffing dogsand vehicles, for work outside the target counties,said Thomas, the former Forest Service supervisor.Agencies participating in the “interdiction”initiative aimed at stopping drug couriers werein effect using HIDTA money to fund their ownindividual programs, reviewers noted.Maj. David Herald of the <strong>Kentucky</strong> Divisionof Vehicle Enforcement said there was a shortfallin exactly what the HIDTA program is supposedto promote: cooperation, <strong>com</strong>municationand information sharing.The vehicle enforcement division had participatedin the interdiction program that wascanceled.Herald said investigators from other agenciesdidn’t let his officers know about potentialleads. And when the interdiction cops made anarrest, there was no attempt to follow up andconnect the drug courier to other investigations.“Everybody was basically doing their ownthing, and you’re not going to be successful thatway,” Herald said.Herald and others said the HIDTA concept isgood, but has been undermined at times whenparticipating agencies looked to protect turf.The federal reviewers also said federal andstate agencies needed to work with local officerson task forces, said U.S. Attorney GregoryF. Van Tatenhove.‘It’s done a lot of good’Several current and former HIDTA officialssaid it’s not unusual that there were somebumps in developing such a large program.Some say the Appalachia program didn’t get agreat deal of firm direction from ONDCP in itsearly days.Nonetheless, the good has far outweighedthe bad, they said.“I think it has been a successful program.It’s done a lot of good,” said Gilbert, the formerdeputy director.HIDTA officials are working on changesaimed at making the program more effective.For instance, the DEA, state police and theForest Service have started working on taskforces with local police, or developing suchjoint efforts, in several counties.The program’s executive board has requestedfederal approval to pick up salary and overtimecosts for some local officers to take part intask forces, said Sturgill, the HIDTA director.And though there have been concerns abouttrusting local officers, there are a lot of goodcops throughout the region who can work withfederal and state authorities to bust drug operations,Thomas said.At the direction of its federal overseers, theAppalachia HIDTA board will be putting itsmoney behind the concept of cooperation. Beforeany agency can get funding, it will have tobe part of a formal task force with a defined objective,said Van Tatenhove, who is on theboard.That change is aimed at ensuring that moneygoes to specific anti-drug operations, insteadof just going to agencies.As HIDTA nears the end of its fifth year inbusiness, Van Tatenhove said he is excitedabout its potential.“This is a great resource for our <strong>com</strong>munity,”he said, “particularly a part of our state thatcontinues to struggle with the war on drugs.”

Originally published Jan. 29, 2003By Bill Estep and Tom LasseterHERALD-LEADER STAFF WRITERSIn the late 1980s, two professors <strong>com</strong>pileda list of criminal rings in Eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong>,then hung around game rooms, roadhousesand restaurants, played a little poker and dida lot of listening.The goal was to make contact with peoplein crime rings and find out whether drugdealers, gamblers, prostitutes and others usedbribes or relationships with local public officialsto protect illegal activity.Turns out they did.Gary W. Potter and Larry K. Gaines, thencriminal-justice professors at Eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong>University, reported that of 28 criminal organizationsthey studied in five counties, 25 benefitedfrom some corrupt or <strong>com</strong>promising relationwith government and law-enforcement officials.The study reported payoffs; family ties betweenpeople paid to enforce the law and peoplebreaking it; and cases of “official acquiescence,”or cops looking the other way.“It is inconceivable that in these rural counties,illicit gambling, prostitution, alcohol anddrugs could be delivered on a regular and continualbasis without the knowledge of governmentofficials, law enforcers and ‘legitimate’ businessmenin the <strong>com</strong>munity,” said the study, publishedin February 1992 in the Journal of ContemporaryCriminal Justice, an academic journal.Potter and Gaines used news accounts toidentify criminal organizations. They later interviewed16 people involved in the rings,promising them anonymity.The professors did not identify the fivecounties in the study.Not much had changed by the late ’90s, accordingto a 1999 report from the AppalachiaHigh Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, basedin London.The assessment said the marijuana problemin Appalachia, <strong>com</strong>pounded by the ruralnature of the area and “increasing law enforcementand government corruption, is beginningto overwhelm the limited capacity ofstate and local officials.”Lawmen broke the lawSince the professors <strong>com</strong>piled their information,the courts have been busy dealingwith corrupt cops.In August 1990, six Eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong> lawenforcementofficers, including the sheriffs ofPRESCRIPTION FOR PAINLEXINGTON HERALD-LEADERGovernment corruption widespread, studies sayLee, Wolfe, Owsley and Breathitt counties,were arrested in an FBI drug sting describedas the largest of its kind in <strong>Kentucky</strong> history.A 42-count indictment charged them withconspiracy to extort money, distribute drugsand protect drug dealers. Five of the six wereconvicted.Two years later, Terrence Cundiff, a formerhonorary deputy in Breathitt County who wasrunning for sheriff, was arrested in Texas enroute to <strong>Kentucky</strong> with 400 pounds of marijuana.Cundiff later pleaded guilty to being involvedin a multistate marijuana conspiracy.In 1994, Douglas Brandenburg became thesecond Lee County sheriff charged with drugcrimes since 1990. Brandenburg, chargedwith conspiring to distribute marijuana andobstruction of justice, later pleaded guilty toobstructing justice. He was sentenced to ninemonths in prison.Other arrests of cops followed in Bell,Breathitt and Perry counties over the years.Potter said this month he doubts the incidenceof police and government corruptionhas declined in Eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong> since hewrote about it a decade ago.“I think that it’s pretty ingrained,” he said.PHOTOS BY DAVID STEPHENSON | STAFFState police Trooper Bret Kirkland hacked through briars while looking for a plot of marijuana. Anti-pot efforts in <strong>Kentucky</strong> cost about $7 million a year.‘Just growing marijuana’◆SOME SAY ANTI-POT MONEYSHOULD BE SPENT ELSEWHEREOriginally published Jan. 29, 2003By Tom Lasseter and Bill EstepHERALD-LEADER STAFF WRITERSHAZARD — As he prepared for anotherworkday scrambling around Eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong>’shills, cutting and burning marijuana, state policeTrooper Chris Clark pondered the future.“I feel like I’m going to show my kids photosone day — ‘Look at me burning this marijuana’— and it’ll be like Prohibition, like Iwas busting liquor barrels,” said Clark, a oneyearveteran of the most-questioned front in<strong>Kentucky</strong>’s drug war.Clark is part of an annual effort by statepolice, the National Guard and the U.S. ForestService to cripple the state’s giant marijuanaindustry.The strike-force campaign in <strong>Kentucky</strong>costs taxpayers about $7 million a year. It patrolsthe mountains in helicopters, Humveesand pickups on a search-and-destroy missionthat has burned an estimated $4.2 billionworth of pot over the past five years.But as prescription-drug abuse has skyrocketedin Eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong>, many peoplehave <strong>com</strong>e to think that marijuana eradicationburns time and money that should be focusedon deadlier, more-addictive drugs.One example is the abuse of prescriptionpainkillers. Federal officials report that betweenJanuary 2000 and May 2001, <strong>Kentucky</strong>had 69 deaths in which the drug that makesup the painkiller OxyContin was present inthe deceased. In 36 deaths, the levels weretoxic, according to a federal report.“Marijuana is a big problem in all of Eastern<strong>Kentucky</strong>, but it’s not killing people,” saidSusan Ramos, the executive director of theOwsley County Industrial Authority.Ramos spends her days trying to bring employersto one of the poorest counties in thenation — a job she said is <strong>com</strong>plicated by thearea’s drug problem. But it’s harder drugs, notpot, that scare off <strong>com</strong>panies and limit thesupply of able workers, she said.Meanwhile, police are “busy flying helicoptersand driving Humvees looking for marijuana,”Ramos said. “It’s backward.”Some prosecutors agree. “I think they wastetoo much time on marijuana,” said Clay CountyAttorney Clay Massey Bishop Jr. “I have yet tohear of anyone overdosing on marijuana.”Not a ‘benign herb’Larry Carrico, head of the <strong>Kentucky</strong>Agency for Substance Abuse Policy, said theeradication campaign is needed.Marijuana can cause health problems forusers and serves as an entry-level drug foryoung people, which can lead to bigger problems;it’s not the “benign herb” some peopleclaim, Carrico said.Sgt. Ronnie Ray, director of operations forthe strike force, said the marijuana tradewould explode if not for his team’s efforts. “Ilook at what we do as drawing a line in thesand,” he said.In some ways, it’s hard to imagine the illegalcrop growing much more.<strong>Kentucky</strong> and Tennessee account for almosthalf of the marijuana grown outdoors inthe United States, according to a 2000 federalreport.Marijuana, not tobacco, is <strong>Kentucky</strong>’sNo. 1 cash crop, federal law-enforcementagents say. They are not alone in that conclusion.A national group that hascampaigned for legalizing marijuana, theNational Organization for the Reform ofMarijuana Laws, says that in 1997, <strong>Kentucky</strong>’smarijuana crop was worth $1.36 billion,eclipsing approximately $814 millionfrom tobacco.Local impactThose who grow pot might think they arenot contributing to local drug problems becausethey sell their crop out of state, saidLeslie County Attorney Phillip Lewis, whotook office this month.In reality, he said, the business brings in abad element. The drug trafficker who <strong>com</strong>esto buy marijuana might try to barter withpills, which could be sold locally, Lewis said.“I don’t think you can fool with drugs andkeep it a clean crop going north,” Lewis said.Other prosecutors take a less-stringentview.Lori Daniel, the assistant <strong>com</strong>monwealth’sattorney for Magoffin and Knott counties, saidmarijuana is nowhere near the top of her listof drug crimes to prosecute.“I’m to the point now where when I’mlooking at cases, it’s ‘Oh, he’s just growingmarijuana.’ When did it get to that point? Wejust have another, bigger problem,” Danielsaid. “As bad as it sounds, people on marijuanastay home, get the munchies and don’t goout and rob and steal.”Left: <strong>Kentucky</strong>and Tennesseeaccount for almosthalf of the marijuanagrown outdoorsin the United States,according toa federal report.Below: State policeTrooper Mike Wolfecarried marijuana cutdown during a raid inPerry and Breathittcounties in October.ANATOMY OFA FAILED BUSTThanks tobad tapes,Bell casesdrew a blankOriginally published Jan. 29, 2003By Tom Lasseter and Bill EstepHERALD-LEADER STAFF WRITERSPINEVILLE — The informant gotmore than $3,000. The cops and the prosecutorgot nothing except a note backfrom the jury that said, “not enough evidence.”And a dozen defendants went free.A failed 1996 drug roundup in BellCounty shows how police can be burnedby unreliable informants, bad recordingsand their own missteps.In the Bell cases, informant Ricky Adkinswas sent to make secret audiotapes ofdrug buys with a hidden recorder — butthe tapes turned out to be either blank orgarbled, court records show.State police Det. Alice Chaney, then a15-year veteran with several <strong>com</strong>mendations,was running the investigation. Whenshe was named Post 10 Trooper of theYear in 1990, her boss wrote that no casewas too <strong>com</strong>plicated for her.Had Chaney checkedthe tapes soon after gettingthem — as police sayshe should have — shewould have discovered theproblem and could havetried again.Instead, Chaney testified,she didn’t listen tothe tapes until later.In all, a dozen peoplewere indicted in theroundup.But Bell Commonwealth’sAttorney KarenBlondell said she didn’tlearn of the tape problemuntil her office wasAlice Chaneyfailed to checkaudiotapes ofdrug buys.The tapesturned out tobe unuseable.preparing for the first trial — a cocainetraffickingcase against Derrick “Bugsy”Hariston, 26.“It’s disappointing, but you have got todo the best you can with what you’rebrought by the police,” Blondell said in arecent interview. “I’ll say this — it wasembarrassing.”Even without tapes, Blondell decided totake the Hariston case to trial with testimonyfrom Adkins and Chaney.Chaney testified that she had workedabout 400 drug cases in one 10-month period.Defense attorney Jennifer Nagle boredown on the tape issue, according to atranscript.Nagle: “That tape is totally blank?”Chaney: “Yes ma’am.”Nagle: “That tape had to be turned off,didn’t it?”Chaney: “It was either turned off or thetape recorder wasn’t working.”Hariston denied selling cocaine to Adkins,saying it was a case of mistaken identity.Jurors acquitted Hariston, writing“not enough evidence” on the verdictform.Charges against the other 11 Bell Countydefendants were eventually dismissedbecause of the poor quality of the tapesand problems locating Adkins, accordingto state police files.Adkins could not be reached for <strong>com</strong>ment.Chaney testified that for working as aninformant, Adkins received a standard paymentof $100 for each felony drug buy hemade and $50 for each misdemeanor. Thatwould have totaled more than $3,000 forthe charges listed in the 12 Bell County indictments.Chaney resigned from the state police inApril 2000. She recently said she sufferspost-traumatic stress disorder from her serviceas a state-police officer and receivesfederal and state disability payments.“It bothered me a lot … when thosethings started going to trial and the <strong>com</strong>plicationsstarted happening,” Chaneysaid, though she did not recall specific detailsof the 1996 drug roundup.State police Maj. Mike Sapp said that afew years ago, some detectives doingstreet-level drug investigations out of regionalposts — such as Harlan, whereChaney worked — didn’t have enoughtraining in such work. Nor were post-levelsupervisors specifically trained to overseesuch investigations, Sapp said.The <strong>Kentucky</strong> State Police now trainsdetectives who do drug investigations tolisten to audiotapes of undercover buyssoon after the transactions, Sapp said.Also, supervisors now get specific trainingin narcotics investigations, he said.Sapp also said the state police hadproblems with recording equipment at thetime of the Bell County roundup. Theagency has since upgraded its equipment.Prosecutor Blondell said she also has anew policy: She or someone in her officelistens to undercover tapes before presentinga case to the grand jury.

PRESCRIPTION FOR PAINLEXINGTON HERALD-LEADERQUESTIONABLE PRACTICES◆PROSPECT OF DOCS DEALING DRUGSPRESSURES MEDICAL-LICENSING BOARDDAVID STEPHENSON | STAFFDr. David H. Procter’s home in South Shore cost $750,000. The estate includes a swimming pooland maid’s quarters. Procter filled the home with Victorian furniture, Chinese rugs, African art andan $1,800 pair of 7-foot-tall bronze storks, according to bankruptcy records.Suspectclinic fueleda lavish lifestyleOriginally published Jan. 31, 2003By Lee Mueller and Charles B. CampHERALD-LEADER STAFF WRITERSASHL<strong>AND</strong> — Dr. David H. Procterstood still as a bird outside thefederal courthouse here one day lastJuly — until someone pointed a televisioncamera at him.Blinking once behind his wirerimmedglasses, he suddenly turnedon the heels of his square-toed shoes and fleddirectly into the traffic on four-lane GreenupAvenue. “He was escaping you,” his lawyer,Tracy Hoover, told reporters. Moments earlier,Procter had pleaded not guilty to criminaldrug charges.Of all the physicians linked to the plague ofprescription-pill abuse in this region, Procteris alternately the most visible — and the mostelusive.Some South Shore residents say he’s a finedoctor they’d gladly see again if he extractshimself from his legal problems and retrieveshis license.But law-enforcement officials claim Procter’sclinic supplied drugs to a legion of Eastern<strong>Kentucky</strong> and southern Ohio abusers, andeffectively served as a launching pad for otherdoctors who went on to start similar practices.In response to a federal indictment lastsummer, he denied writing illegal prescriptionsand claimed someone else in his officehired the doctors, some of whom he said henever met.Procter’s penchant for fine living has longmade him conspicuous in an area where theannual in<strong>com</strong>e averages $27,000. He wasclearing more than $200,000 a year by the late1980s, according to old bankruptcy records.By 1997, his clinic was generating as much as$450,000 a year before expenses.He built a $750,000 house with a swimmingpool and maid’s quarters on a gated estate.He bought Victorian furniture, Chineserugs, African art and an $1,800 pair of 7-foottallbronze storks, according to bankruptcyrecords. He owned a Mercedes, a motorcycle,a black Porsche 930 and a classic red Corvette.Procter and two former employees indictedwith him face trial April 23.Procter arrived in South Shore at age 26,wearing an Afro-style haircut and fresh from aone-year internship in Nova Scotia, Canada.After working briefly for a well-known localdoctor, he soon opened his own office beside aused-car lot along U.S. 23.By the early 1990s, an estimated 4,000 to5,000 patients from the region were trekkingto little South Shore to see Procter.Then things began to sour.Citing tax problems and losses on $1.2 millionof rental properties, Procter and his wife,Karen, filed for bankruptcy protection in1992. They listed nearly $1.6 million in debtsand $1.4 million in assets.Then, in 1993, Procter was acquitted ofthreatening a youngster in a local schoolyardat gunpoint over a T-shirt that Procter said belongedto one of his boys. He later settled acivil suit with the youngster’s family.Procter denied that he ever threatened theschoolboy with a gun. But twice in court papershe volunteered that shortly before the incident,he borrowed and returned a .357-caliberMagnum state-issued pistol from KeithNSouthShoreGREENUPCOUNTYCooper, a state trooper at the timewho is now Greenup County sheriff.Cooper claims ownership of about100 guns. He did not recall lendingone of them to Procter. “If (Procter)gets in trouble, he tells everybody,‘I’m so-and-so’s friend,’” said Cooper,who enjoys a solid reputation amonglocal lawmen.Procter also sold Cooper a housein 1985 on a land contract for $52,000 —$4,000 less than Procter had paid for it in1979. Cooper resold it for $66,000 in 1993.The link between the two is a political issueto some. “People had a lot of concerns,”said Sgt. Kevin Diedrich, a Flatwoods policemanwhom Cooper beat in the primary electionfor sheriff last year.Cooper dismissed the criticism as warmedoverelection rhetoric, claiming he bustedmore than 80 people <strong>com</strong>ing and going fromProcter’s clinic.Procter was accused of pressuring somepatients into performing sexual acts in the1990s, according to a <strong>com</strong>plaint prepared in2000 by the state Board of Medical Licensureto support a license-suspension order.One patient said Procter began counselingher for depression, but then initiated sexualactivities and eventually established a patternof visits that included no counseling — onlysex and prescriptions, according to the <strong>com</strong>plaint.Procter repeatedly denied the sexualmisconductallegations in fighting the attemptto suspend him.In November 1998, Procter drove off U.S.23 and hit a utility pole. He said in a warrantthat an angry patient knocked him off theroad. Procter later changed his story anddropped the charge.Citing injuries from that wreck, he surrenderedhis medical license in August 2000; hehas been collecting $198,000 a year in disabilityinsurance, court records show.Still, he kept the clinic open until last fall,paying as much as $3,250 a week for a seriesof fill-in doctors. Procter showed up at theclinic occasionally, but claimed he was doingnothing more than emptying trash or openingmail.Last month, Procter changed lawyers, hiringScott C. Cox of Louisville, a former federalprosecutor, to replace Hoover. Cox wouldn’t<strong>com</strong>ment on the charges against Procter.Before he was replaced, Hoover had arguedthat Procter was being made a scapegoatfor government agencies that have failed toprevent trafficking in prescription drugs.“It will be a trial about drugs, sex andmoney,” Hoover said. “He’s the one they’re goingto hang out there.”Until the day it closed last August, Procter’sclinic had a large sign inside the door declaringthat office visits cost $80 to $120.The last physician to work in the clinic, Dr.Steven Preston, 33, of Carlisle, Pa., said he arrivedknowing the clinic’s history, but Prestonsaid Procter told him to operate a family practice,offering pediatric care.Unfortunately, “about 100 percent” of thepatients he inherited were pain patients,Preston said.When he prescribed anti-inflammationmedication instead of pain pills, many did notreturn, he said.“It will be a trial about drugs, sexand money. He’s the one they’regoing to hang out there.”Tracy Hoover,former attorney for Dr. David H. ProcterLineup of the accusedDAVID H. PROCTER■ Opened medical clinic in South Shore in1978. Kept his last location, called PlazaHealthcare, open until 2002.■ In 1987, successfully fought attempted disciplineby <strong>Kentucky</strong> Board of Medical Licensure.In 1999, board filed new allegations, includingclaims that he traded narcotics for sexual acts.■ Is accused in a federal indictment of conspiringwith two office aides to illegally prescribenarcotics.Now: Pleaded not guilty. Living in South Shoreon gated estate, he awaits trial April 23.STEVEN PARIS SNYDER■ Licensed by <strong>Kentucky</strong> in 1997 despite earlierdrug and weapons charges in Indiana. Beganworking for Procter in January 1999. Pay:about $2,800 a week.■ Left Procter after eight months; beganworking on his own. Pay: up to $2,100 a day.■ Admitted taking up to 30 Lorcet pain pills aday and injecting OxyContin, a powerfulpainkiller. Now drug-free and expected to testifyin Procter’s trial, his lawyer said.Now: Awaits sentencing after pleading guilty tofederal weapons and drug charges in April 2001.Owned 107 firearms at one time, records say.FREDERICK COHN■ Began working for Procter in September1999. Procter paid a physician-placementagency $3,250 a week for his services, plusliving expenses, court records say.■ Left Procter to open his own clinic inPaintsville in August 2000. He and a partnerwrote prescriptions for 45,000 pills a day.Charged with illegal distribution of drugs.■ Now: Free on $25,000 bond, living in Albuquerque,N.M.; awaiting Feb. 24 trial in London.FORTUNE J. WILLIAMS■ Licensed by <strong>Kentucky</strong> in 1996 despite hisfailure to disclose a drug charge. Started in<strong>Kentucky</strong> as a diet doctor in Covington.■ Began working for Procter in August 2000,but left shortly afterward for Garrison, about20 miles away in Lewis County. There, heworked in a clinic managed by Procter’sformer office manager.■ Left <strong>Kentucky</strong> for Jamaica before his sealedindictment was opened last year. Was arrestedupon his return, charged with writing illegalprescriptions.Now: Unable to post $10,000 bond afterpleading not guilty, he awaits trial in theLewis County Jail.RODOLFO SANTOS■ Joined Procter’s payroll in 2001 at $2,500 aweek; stayed until his arrest last summer.■ As many as seven of his patients died ofdrug overdoses, according to a <strong>Kentucky</strong> medicalboard document.■ Told medical board investigator that his patientswere all liars and drug addicts. “I amnot the police; I do not know if they are sellingor sharing their prescriptions.” Charged withwriting illegal prescriptions.Now: In Pennsylvania; awaiting trial April 14in Greenup Circuit Court.Originally published Jan. 31, 2003By Charles B. Camp and Lee MuellerHERALD-LEADER STAFF WRITERSSOUTH SHORE — Illegal machine guns.Drug arrests and drug addiction. Tales of baddebts, exploitative sex and gunpoint confrontations.Credentials for a street gang, perhaps. Not amedical career.But these five men weren’t gangsters. Theywere doctors — doctors who authorities saysupplied millions of dollars’ worth of prescriptionnarcotics to drug abusers in Eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong>.Each of the physicians, who have been indictedon specific counts of illegally prescribingdrugs, worked at one time or another at a smallclinic in the tiny Ohio River town of SouthShore.Each got started or managed to stay in businessin <strong>Kentucky</strong> thanks to the way the state policesdoctors.At a time when a raging drug crisis haskilled or damaged thousands of Kentuckians,the state Board of Medical Licensure has beenconfronted by a problem unforeseen when itwas created 30 years ago:The narcotics of choice choking rural <strong>Kentucky</strong>don’t <strong>com</strong>e from Turkish poppy fields orColombian coca plants. Most <strong>com</strong>e from theprescription pads of licensed doctors.And a board created to monitor professionalstandards and assure high-quality health carehas been overmatched by the growth of a lucrative,illicit market for pills.The panel, which screens more than 1,000new applicants for licenses annually, oftenmakes trusting assumptions. It doesn’t get asmuch information about applicants as it could.And it’s confined by statutes that limit its powersin controlling — or even monitoring —the 8,800 doctors already practicing in <strong>Kentucky</strong>.In the South Shore cases:■ Three of the physicians were granted <strong>Kentucky</strong>licenses despite histories of criminal, civilor professional trouble elsewhere.■ A fourth escaped scrutiny by <strong>Kentucky</strong>regulators until an Ohio coroner raised questionsabout him. By the time <strong>Kentucky</strong> acted, hehad been linked to seven patient deaths.■ The fifth doctor, who at various times employedall the rest, first came into regulators’sights 20 years ago, but kept his clinic open untillast fall despite two attempts to sanction him.One has pleaded guilty; the others face trialsthis year.Board members say they know it’s their jobto prevent all this.The board “is not in business to protectphysicians, we’re in business to protect the public,”said president Danny M. Clark, a Somersetdoctor with 16 years on the panel.Still, the state’s soaring prescription-drugproblem has some members of the board reeling.They aren’t accustomed to looking for criminalpotential in a fellow doctor.“Until a few years ago, you just didn’t thinkabout physicians having felony convictions,”Clark said.A very small number of <strong>Kentucky</strong> doctorsare unscrupulous, but just one can do seriousdamage, said Michael Duncan, director of specialinvestigations for the state attorney general’soffice.“Bad docs are just overwhelmingly horriblefor a <strong>com</strong>munity,” Duncan said. “Get people addicted,take their money.”Regulator can’t look for troubleIn a 66-month stretch that ended last month,<strong>Kentucky</strong> licensed 4,715 new medical and osteopathicdoctors, and rejected just 27. Eight rejectionscame in the last six months.The medical board couldn’t check any applicants’backgrounds through the FBI’s criminalrecord database — despite a law passed by theGeneral Assembly last year authorizing suchchecks. The FBI rejected the bill’s wording astoo vague.This session, lawmakers will be asked to tryagain, specifying that the board would submitapplicants’ fingerprints to the FBI for checking.<strong>Kentucky</strong> doesn’t look for or ask applicantsabout bankruptcies, in<strong>com</strong>e-tax liens or big disputeddebts — many of which are easily discoverablethrough Internet searches or credit reportingagencies.Few if any states do those things, though somestates’ medical boards ask about delinquent childsupport; and other states, including <strong>Kentucky</strong>, askabout delinquent student-loan payments.Such financial information might signal thata doctor is “desperate for money,” said Dr. L.Douglas Kennedy, a Lexington pain specialistwho often evaluates suspect physicians for theboard. But the board’s general counsel, C. LloydVest II, said members couldn’t deny an applicanta license on financial grounds alone without citingsome violation of state law.<strong>Kentucky</strong> runs applicants’ names through twonational databases for evidence of misconduct. Itchecks medical degrees; training; hospital connections;old jobs; and any disciplinary recordsfrom other states. Candidates must answer abouttwo dozen questions about current or old sins.The checks must turn up serious defects beforethe board can refuse a license. “Both morallyand legally, we have to be able to defend ourposition,” Clark said.See next page