Untitled - Vance Stevens

Untitled - Vance Stevens

Untitled - Vance Stevens

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

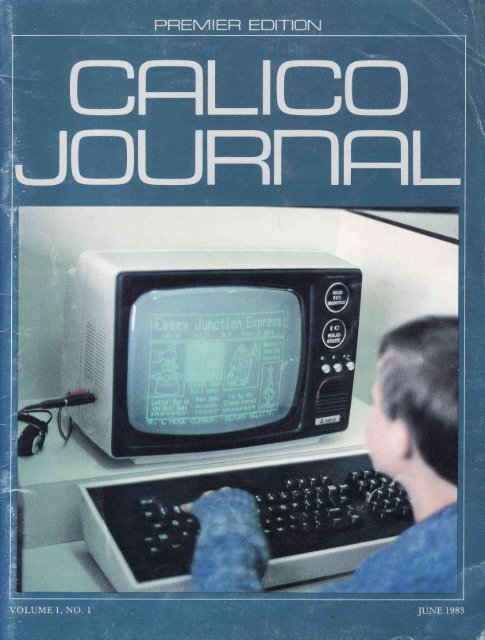

CtrLICOJOURNtrlL@GIIIreTEditor: Dr. Frank R. OttoArsirtant Editor: H. Leon TwymanDesign and Layout: Steve SmitGraphics Attist: Brenda BraunType*etting by Executype, Charlotte ColleyMeiling end Grorlation: Ivette GalvezPhotos: Cover and photos for the article on theWaterford School are courtesy of Fred O'Neal.Photos for the "Montevidisco" article arecourtesy of Brigham Young University MotionPicture Studio.Printed by Brigham Young University PressThe CALICO Journal is published quarterly in themonths of September, December, March, andJune.The CALIGO office is located at 229 KMB,Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602;(801) 378-6533.COMPUTEFI AIDED LANGUAGE LEAFINING S. INSTFIUCTION CG'NSOFTTIUMVOLUME I. NO. 1 JUNE, 1983About the CALICO JournalA Letter from the Executive DirectorAd PoliciesCALICO Database ReportQuestionnaire Survey Results1984 CALICO SymposiumCall for PapersCALICO CalendarThe Application of Instructional Technology toLanguage LearningJames E. AlatisEqual Time C. Edward Scebold l3A CALI Glossary for Beginners Randall L. Jones l5Waterford School and the WICAT EducationInstitute: An Alternative Model for CAI Researchand Development Fred O'Neal l9An Interactive Concordance Program for theSmall Computer NedJ. Davison 24A Report of a Project Illustrating the Feabibility ofVideo/Computer Interface for Use in ESLProposed CALICO Constitution and BylawsForeign Language Instructional Technology: The<strong>Vance</strong> <strong>Stevens</strong>State of the Art Constance E. Putnam 55Montevidisco: An Anecdotal History of an InteractiveVideodiscLarrie E. GaleComputers and College Composition Charlotte D. Lofgreen 47On Getting Started John R. Russell 5lWANTED:Courseware Reviewers and ReviewsThe Translation Profession and the Computer Alan K. Melbv D5Ethics and Computers: The "Oil and Water" Mixof the Computer World? Paul C. Hardin 58Boris and MENTOR: The Application of CAI Walter Vladimir Tuman 6lThe Foreign Language Teacher as CoursewareAuthor David Weible 623l

A FIEPOFIT OFA PFIOJECTILLUSTFIATING THE FEASIBILITYOF VIDEO/COMPUTERINTEFIFACE FOR USE IN ESLABSTRACTThis report describes a project whosepurpose uas to write a brief d,emonstrationlesson in listening'comprehensionand, then deliaer that lesson u.stng an AppleII 1 computer interfaced with a SonySL-t2t Betantax uid,eo cassette recorder(VCR) using a Gentech ETS-2000 controller.The listening cornprehensionlesson and, hard.uare configuration uered,emonstrated as part of the Rap Sessionon The Latest D.eaelopments in VideoESL/EFL Materials at the TESOL Conaentionin Honolulu, May, 1982.The report is in three parts: (1) a briefsuraey of oideo tape as. uideodisctechnology, (2) a rationale for the use ofinteractiae uideo in ESL, and Q) adescription of the project itself. It is intendedin this report to prouide somebackground in computer interfaced. vid,eoand then to giae insights into sorne difficultiesthat may be encountered bycomputer-naiae ESL instructors wishingto prepare interactiae video lessons.There are many uho belieae that computersuill soon alter on a major scaleuays that people uill be able to learn.Houeaer, existing educational and mediadesign systems may be inad,equate indealing with the demands oftechnologically enhanced ed,ucation.Therefore, new approaches to lessondesign uill haae to be considered. It isbelieued that interactioe tideo, insofar asit ,r highly compatible uith recenttheories of learning, will be able to Pl"y ad.ominant role in these neu approaches.Houeaer, there are technical limitationson uideo tape equipment uhich, fortunately,haue been largely oaercornewith the deaelopment of aideodiscsystems. Thus, although the presentproject deak uith video tape, bothsysterns are cornpared and d,iscussed inthis article.<strong>Vance</strong> <strong>Stevens</strong>fleforeembarking on a description ofl-f this project, some crucial differencesbetween video tape and videodiscshould be mentioned. Just as data can beloaded into a microcomputer either froma disk or from a cassette tape, so can aprogram of video material be accessedeither by means of a video tape or, withthe proper equipment, by means of avideodisc. Disk access has several majoradvantages over tape acce$. For onething, the maximum amount of timeneeded to traverse the two most distantpoints on the disk is five seconds, whereasto rewind a video tape over its entirelength can take several minutes. If thetape is being used as part of an interactivevideo program, then this waiting timecan seriously distract from the impact ofthe lesson.Another advantage of videodisc overvideo tape access is the frame-perfect accuracyof the former. Some video tapecontrollers, such as the one used in thisproject, detect pulses emitted for eachframe as the video tape is played. Thecomputer keeps track of these pulses andcan rewind, play, or fast forward the tapeto any given pulse. However, there is aproblem in that the tape player itself mayof its own momentum rewind (or fastforward) slightly farther than desired, sothat the tape begins a few frames out ofkilter. This problem can be so compoundedafter a few rewinds that, althoughthe computer is counting accurately, thetape is significantly displaced. Videodisctechnology, on the other hand, is suchthat the disk is read at precise points.Frames can be replayed accurately nomatter where they are on the videodisc.In fact, it is possible for the user to bepresented a seamless program despite thefact that the videodisc is being accessed atnon-contiguous points (Allen, 1981 :83).There are many other advantages (anddisadvantages; see Nugent, 1979) to usinga videodisc as opposed to a video tapeplayer in serious interactive videodevelopment. However, the two just merntionedare most pertinent to understandinglimitations on the present project.Santoro and Pollak (1980:50), in reportingon an interactive video authoringsystem developed for the Navy, note that"It has become clear that the video cassetteplayer is the weakest link in the CAVEhardware configuration, and we lookforward to its eventual replacement byvideo-disc technology." But perhaps thegreatest advantage to using videodisc isthe virtual freedom it offers to lessoncreators. As Woolley (1979:81) conciselyputs it, "One of the advantages of computer-basededucation with a microcomputervideodisc system is simply that it isnot technologically clumsy." Video taperecorders, de'spite their greatsophistication, are, relative to videodiscs,technologically clumsy, and those whocreate CAI lessons using them must keepin mind their limitations while attemptingto exploit their advantages.(More complete descriptions ofvideodisc systems can be found, to namejust two sources, in Woolley, 1979, andOnosko, 1982. Also, a VCR interfacesystem with much improved accuracy,called CATI, has been developed byWhitney, 1777 Borel Drive, Suite 402,San Mateo, California 94402.)RationaleThe potential of computer-assisted instruction(CAI) for the enhancement oflearning has excited some and disappointedothers. Many of those excited by thepotential inherent in CAI have yet to witnessor experience what they may envisionas the ideal battery of CAI programs fortheir own learners' needs. This is becauseproper implementation of CAI takes27

more of a commitment in time andresources than most individuals or institutionsare prepared to give.Therefore, when computers are purchasedor made available and CAI isplanned and implemented, short cuts areinevitably taken l.rhich seriously compromisethe final product. Flence,disillusionment can easily occur, preventingall but the most committed from exploringand eventually exploiting thepedagogic power of CAI.One of the most prevalent mistakes ingenerating CAI materials is the propensityof lesson authors to be, as Bork putsit, "imitative of other media" (1981:10).Bork cites in particular attempts by CAIlesson authors to present text on the computerscreen as if it were Pages from abook. Many English lessons on PLATOsuffer from this deficiency, and I mpelfhave watched CAI lesson authors workdirectly from grammar books. Thus,there is a tendency for educators confrontedwith a new medium to fail to makeuse of the unique characteristics of thatmedium, mainly through failure to shakeoff the constraints of old ways of doingthings, and this failure can result in imimproperapplication of what wouldotherwise be an innovative educationalProce$r.Indeed, it is very difficult for teachersbrought up in one educational system toconceive of, let alone prepare materialsfor, a system which, to accommodate therecent developments in computer enhancedlearning, will have to becomeradically different from the one that hassufficed throughout their own education.Yet the call for the re-structuring ofeducational paradigms is one echoedfrequently in recent CAI literature.Educators must not only developmaterials for technologically advancedmedia, but they must also take into considerationrecent trends in research intohow humans learn. Bork, for example,cites recent split brain research in supportof his arSument that the visual componentof instructional materials shouldbe enhanced, even to the point of havingartists join programmers and instructorsin CAI creation (1981:16). Molnar(1979:13) asks if we can "create new instructionalparadigms that will permit usto combine the various features of themedia to take advantage of differentialbrain functions and thereby facilitate andamplify human reasoning."As if on cue, technology has produceda breakthrough which seems to intersectneatly with the latest theories of learningpsychologists, and which has providedproponents of CAI with yet another cause28for excitement over the potential of interactivelearning. This new breakthroughis interactive video; that is, videowhose sequencing is controlled by amicroprocessor which in turn makespossible CAI capabilities.Although the idea of coupling computersand video devices has been aroundfor the past decade (manufacturers ofeach were brought together at a conferencein 1975), devices allowing actualinterface have been on the market foronly a few years. As is inevitable when anew toy hits the market, a plethora of articleshas quickly followed highly toutingthe potential of interactive video. Asalways, educators need to question thebasis of these claims; but the number ofwriters reporting success with interactiveThi^s neu breokthrough isinteractiae aid,eo; that i,s,ttid,eo uthose sequencing iscontrolled, by a microprocessoruhich in turn makespossible CA I capabilitics.video is impressive. According to Woolley(1979:81),"Obviously the market will bemoving rapidly in the direction of digitalaudio and digital video." Kadesch(1981:301) says, "It seems clear thatstand-alone systems employing interactivevideo and computer graphics willemerge as the system of choice . . . Thevideodisc coupled to improvedmicrocomputers can add to the learningsituation powerful capabilities simply notpresent in traditional environments."Molnar notes that at a recent (1975)Human Resources ResourceOrganization (HumRRO) conference,held under the auspices of the NationalScience Foundation, "The conferenceparticipants considered videodisc to havethe most promising near-termtechnological applications for educationand recommended the NSF explore thepossibility of combining computers withvideodisc" (1979:13). This is just a samplingof some of the very positive commentsmade in favor of interactive videoby people who have had the opportunityto work the new medium into theireducational programs.The need to revise paradigms by whichCAI is used has been most apparent withthe advent of interactive video, Particularlyvideodisc, technology. If the differencesbetween instructional strategiesusing computer and those usingtraditional means have been so subtlethat they have escaped some materialsdevelopers for the past 20 years, video interfaceis at least obviously in need of anew approach. With regard to this need,Molnar reports that it was agreed at theHumRRO conference that "whiletechnology had undergone orders ofmagnitude improvement, our instructionparadigms had not and currentparadigms for computer-assisted instructionand problem solving could not be extendedto take full advantage oftomorrow's technology" (1979:13).Leveridge (1979:38) says that old habitsof linear program design must yield to"new kinds of creative thinking . . Togain the benefits inherent in this newsystem, it will be necessary to think in newterms for program design and production."One of the assumptions Leveridgemakes in visualizing this future paradigmwas mentioned by Kadesch, and that isthat the "system of choice" will be standalone(unlike other systems which workvia cables or telephones off a centralmainframe). Leveridge would add thatthese stand-alone systems will be personallyowned: "Eventually, each learnerwill have his own microcomputer with attachedvideodisc player and televisionset" (1979:38). The assumption thatreduced costs and ubiquitous applicationwill result in computers (and videodiscplayers) proliferating like calculators iswidely held, and those who believe thatthis will come about feel that theresulting changes in educationalpossibilities will necessitate new approachesto teaching.Of course, there are forces from withinsociety acting in favor of change in theway education is carried out. Bork thinksthat the sheer numbers of studentsdemanding education these days are thwartingthe efforts of existing systems tocope. Thus there has arisen "a new force .. . in the educational scene," the "majordriving force behind which is the computer,particularly . . . the personal computer"(1981:8). The nature of this forceis a demand for interaction in education,an urge to return to the ideal of Socraticlearning that was possible wheneducation was available only to aprivileged few. Bork believes that in'telligent videodisc systems can bringmultimedia capabiligies to bear on theproblem, bringing active learning tostudents individually, regardless of theirnumbers.Allen mentions the trend in educationtoward "demassification," a term he hasborrowed from Alvin Tofler's book, The

Third Waue. Demassification is the use ofcomputers to approach smaller andsmaller clusters of people. Whendemassified computers are coupled withintelligent video, "the concept of the 'personalized'frlm is born-a unique configurationof video segments instantaneouslyassembled on the basis of theviewer's needs, wants, and capacities"(198r:92). .If there is indeed a trend in education,driven by advances in computer/videotechnolog'y, which will make possiblewidely varied options in futurestudent/teacher interaction, thenperhaps DeBloois' (l 979:3a) "comparisonof model assumptions" is a goodbarometer of how educational paradigmsmight change in the future. DeBlooiscompared "current instructional designmodel assumptions" with "probable newinstructional design model assumptions"and notes eight differences in the two.These are (l) mosaic/multi-dimensional(as opposed to linear) development ofmaterials and strategies, (2)heterogeneous ("r opposed tohomogeneous) audience planning, (3) interfacing,subsystem (as opposed tosequential) component development, (4)multiple and continuing (as opposed toone-time) selection'of material and format,(5) eclectic ("r opposed todominant) media options, (6) unlimited(as opposed to limited) validation cycles,(7) integration (as opposed to separation)of resource and presentation materials,and (8) extended (as opposed to limited)dissemination capacity.DeBloois' specification of areas wherechange in media design will likely occurshould be useful for those contemplatingtaking advantage of the new technologiesin creating mate,rials for teachingprograms. Nevertheless, Molnar cautionsagainst over-reliance on theory in copingwith the advent of advanced teachingtechnology. Noting that "Conventionalapproaches to research and developmentare generally inappropriate if one wishesto foster innovation," he suggests that"No amount of paper studies ortraditional equipment evaluations arelikely to produce answers." The only waythat educators will be able to developmaterials using the new media will be "bybuilding a prototype and using it"(1979:15).It is with all these thoughts in mindthat the present project was conceived.Exercising some of DeBloois' designassumptions, such as eclecticism in mediaoptions and interfacing of components,and in an attempt to appeal to both sidesof the brain while engaging students incognitive interaction with their lessonmaterial, a prototype intelligent videoESL lesson as described below has beendesigned and demonstrated to beworkable.ImplementationThe project, undertaken mainly as anillustration of applications to ESL ofcomputer/video interface, had at leasttwo auxiliary goals. The first of these wassimply to see if it would be possible, usinga Gentech ETS-2000 Video Controllerand Gentech software on floppy disk, tointerface two machines, an Apple II +computer and a Sony SL-323 Betamaxvideo cassette recorder, in such a way thatthe computer would control the VCR andinterject text and question frames at ap-"While technology lmdund,ergone ord,ers ofnmgnitud,e im,proa ernent,our inst lrctian parad,igmshad,not6nd,. . . currentparod,igms f or computer -as s i,s t e d ins truc tion andproblent soluing coul'd notbe extended to take fulladuantage of tornomou)tstechnology."propriate points in the lesson. It is alwaysa challenge to explore the potential ofnew equipment, but something of a risktoo, since computenvare does not alwaysperform as its manufacturers claim.Therefore, it could not be assumed asgiven that the parts would actually fittogether properly; hence, a major part ofthe project was to test the parts in relationto each other.In this regard, the project was a test ofGentech's equipment. However, theproject had also the goal of seeingwhether an ESL instructor, albeit onewith about a year and a halfs exposure tocomputers, could approach complexelectronic devices, glance over a manual,hook up an interface card, and within anhour or two be designing a lesson hecould himself input into the computerwithout outside assistance from a computerspecialist. Since much of gettingstarted in CAI is a matter of overcomingfear of frustration and impotence at thehands of complex and unfeelingmachinery, it was this second goal thatmay be of most significance to theaverage ESL instructor.In bringing the project to fruition,several steps were followed. First, all theequipment mentioned above had to bebrought together. Second, a video tapehad to be selected, reviewed, and thentranscribed. Third, target learning forthe lesson had to be ascertained and aninteractive CAI lesson teaching thedesired skills had to be conceptualizedand integrated with the film. Next, thelesson had to be fully conceived on PaPerbefore inputting it into the computer foreventual storage on disk. This lastoperation, inputting into the comPuter,was in turn a three-step procedure involving(t) input of text and questionframes, (2) division of the accompanyingfilm into video blocks, and (3)specification of logic flow.It would be interesting to recount theadventures involved in realizing the firststep, that of accumulating the equipment,but anecdotes of that nature areclearly outside the scope of this report.However, it might be worthwhile to mention,in light of present day economicexigencies, that around $3,600 worth ofgadgetry was enlisted in this project. Thevideo controller card and accompanyingsoftware, worth $550, was loaned by Gentech.The $850 VCR was the property ofthe Department of ESL at the Universityof Hawaii, and this particular VCR wasselected for purchase by the departmentbecause of its ability to accept interfacewith a computer. The other equipment(the Apple II * computer and disk drive)cost about $2250.Ttre second lrtep was choice of videomaterial. Since the goal of the project wasnot to try to develop the ideal intelligentvideo lesson around the ideal video tape,the choice of taped material was notcrucial. Selection of a tape of a lecture onthe renewal of the controversy betweenthe evolutionists and creationists, a topicdiscussed in listening comprehensionclasses at the University of Hawaii, wasmade on the basis of its being locallyproduced and readily available. Thus ataped lecture was used instead of aprogram developed especially to illustratethe unique properties of the medium.The latter would of course be more appropriateif serious development of interactivevideo were eventually to takeplace.Bork warns particularly against usinglectures in developing materials for interactivevideo, on the grounds that "Lecturesare not an interactive learningmechanism . . They are a passive ornegative method of learning(f98f :19). On the other hand, Hallgren

(1980), in an article written about computercontrolled video tape recorders, devised requiring the students to thinkblocks, at which point questions werereports success with use of intelligent about what they had heard within eachvideo at a medical college where "considerableuse" is typically made of videostrationtape to frve minutes helped toblock. (Limiting the length of the demontapedlectures, with or without computer minimize the rewind error noted aboveinterface. Perhaps the situation with ESL and precluded long delays shuttling fromlistening classes at the University of one end of the tape to the other). TheseHawaii more closely parallels Hallgren's, questions, along with accompanying text,since one purpose of the listening comprehensioncourse is to expose students to such a way that there was a space for eachhad to be written out on forms gridded inacademic lectures in English and subsequentlyto help students to analyze lines of available screen space. In otherof the forty characters per each of the 2lthese lectures.words, text and question frames had to beIn working from a lecture, it was planned down to the letter in order thattherefore logical to write a CAI program they could be smoothly typed into thedirected at an ESL student whose aim was computer. This was the most time consumingpart of the overall process, andto improve his listening comprehensionby developing awareness of certain skills one of the most important too, sincehelpful in fostering better listeninghabits. The skills selected were (l) getting Any concept which kthe meaning of unfamiliar words fromcontext, (2) understanding the meanings difficult to contextualize inof complex words derived. from. simplerthe CIASSfOOT, WOUId be Awords, and (3) extracting the main topicsfrom a stream of discourse. These skills suitable subiect for on inter'were selected because elements in the lecturelent themselves to exploitation ofthese skill areas. In addition to questionsconceming these three skill areas, a fourthquestion was added which was simply acheck that the lecture had been understoodup to a certain point.In developing a battery of lessonsutilizing interactive video, it wouldperhaps be better to drive several lessons,each concentrating on one skill areaalone. Then a final lesson might beproduced which would review all of theskills taught in the previous few lessons.Of course, it would be very time consumingto produce all of these lessons,and so, for the purpose of this shortdemonstration, it was decided to includea variety of questions in various formats,and thus demonstrate several possibilitiesfor using the medium.Having targeted the skills to be taught,it was then necessary to make a transcriptof the tape, making special note of thelecturer's topic shifts and pauses. Thesejunctures largely dictated where thedivision of the tape into video blockswould occur. With a videodisc system, itwould have been possible to go every timeto an exact frame and start a videosequence at that precisely predeterminedpoint, but the VCR tape trarxrport wasnot so accurate. After one or two rewindsand fast forwards, the tape would be offby as much as a sentence. So, it seemedprudent to let the video blocks bedelimited largely by natural junctures.The first five minutes of the video tapewere subdivided in this wav into natural30actiae aid,eo lesson.editing capabilities on Gentech's softwareproved to be nearly non-existent. In all,22 frames of text and questions wereprepared. The reader should note thatmost CAI authoring systems have editingcapabilities that are quite forgiving, sosuch meticulous preparation is not partand parcel of every CAI project.Once the frames had been written outand inserted on paper into the film script,the logic was worked out. Each frame hadbeen given a number, as had each videoblock, and setting the logic flow wasmerely a matter of deciding which numberedframe of text was to be placedbefore or after which video block. Whenquestions were asked, depending onwhether the student answered correctly ornot, the program could branch to combinationsof text and video (but notquestions) appropriately. Branchingcapabilities were rather weak; the studentwas only allowed one trial, and there wasnever an opportunity to re-question thestudent to see if a review of the video portionhad succeeded in straightening outwhatever misconception had led to an incorrectanswer in the first place. It shouldbe pointed out that capabilities lacking inthis authoring system would most likelybe available in others. For instance, seeKeller, 1982.With the lesson completely worked outon paper, it was time to input it into thecomputer. As mentioned earlier, this wasdone in a three-step process: text andquestion entry, video blocking, andspecification of logic. The software hadbeen devised so that someone with noprogramming abilities could enter thenecessary information in response toprompts by the computer. I found thereto be no problem with understanding theprompts and with entering the frames as Ihad written them.Once the frames had been entered, Ireturned to the main menu to initiate thenext step of the process: the setting off ofeach video block. This step was begun atthe press of a key, resulting in the videotape being automatically rewound andthe pulse counter being zeroed. At thestroke of another key, the computercaused the VCR to begin playing thetape, and when the key was touched athird time, the tape stopped. This wasvideo block #l , which was leader materialand a segment of the tape that thestudent would never see. At the touch ofanother key, the tape began to playagain, which it continued to do until Istopped the VCR with another touch ofthe keyboard. I had just delimited videoblock #2. In the same way, I was able toblock off the eight video segments that Iwould need for my program.The final step in the creation of the interactivelesson was entering the logicalsequence of questions, text, and videoblocks. To initiate this process, I simplyreturned to the main menu and followeddirections. Essentially, the computerasked me what I wanted it to do first. Itold it to present a text frame. The computerasked me what I wanted it to donext. I told it to show another text frame,and another, and then to play two videoblocks. Then I told it to display aquestion frame. The computer thenasked me what I wanted it to do if thestudent answered the question correctly. Itold the computer that if the student answeredby pressing the letter B, which wasthe correct answer, he should be presenteda text congratulating him on hisintelligence. The computer then askedwhat I wanted done if the student answeredanything other than B. I told it topresent a text frame telling the studenthis answer had been incorrect and thenreplay the second of the two videosegments it had just shown. The computerlikewise continued prompting mefor steps until it had been given the entirelogic sequence for the interactive lesson.With all the text and question frames,the video block delimitations, and logicalsteps preserved on disk, the lesson wasready to run. Fortunately, it workedsmoothly. The only problems encounteredwere that no text editing wasContinued on page 50, column 2

carefully assessed by the individualteacher."Do you really think computers canhelp a student write?" Probably not, ifyou think of the computer as a coldheartedor inimical piece of machinery.But if you think of it as a tool,programmed by expert teachers incooperation with sympathetic and helpfulprogrammers to do what it can do bestand free the teacher for further creativestudent-teacherinteraction, then theanswer is a definite yeslllI,ND NOTtrSlPatricia Cottey, "An Overview of the Computeras Teacher: A Progrcss Report of a ResearchProject to Introduce Diagnostic l'esting and Com'puterized Instruction into the CompositionProgram at Northeast Missouri State University "Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Con'ference on College Composition and Com -munication, San Francisco, California, March l8-20,19822Lester S Golub, "Compute r- Assisted Instructionin English Teacher Education " Paper presented atConference on English Education, National Councilof Teachers of English, St Louis, April 6-8, 19723William Wresch, "Computer-Assisted Learningfor Writing Programs: A Hands-On Demonstrationor Its Potential " Demonstration presented at Conference on College Composition and Communication, Detroit, Michigan, March t6-19, 1983tFor more information, write William Wresch,Ph.D , Uwc-MarinetteCounty Bayshor, Marinette,WI 54143tHelen Schwartz, "Monsters and Mentors: Com'puter Applications for Humanistic Education,"College English,44 (February 1982), pp. l4l-152tFred M Hechinger, "About Education: ComputerHelps Writers to Polish Technical Reports,"Neu Yorh llmes, November 18, 1980, C, 4TKathleen E Kiefer, and Charles R Smith, "Textual Analysis with Computers: Tcsts of BellLaborarories' Computer Software," forthcoming inResearch in the Teaching of EnglishsCharles R Rybero, and Edward B, Versluis,"Computer-Assisted Learning for WritingPrograms: A Hands'On Demonstration of ltsPotential," Demonstration presented at Conferenceon College Composition and Communication, Marchl6-19, 1983.e"Coming: Another Revolution in Use of Compuiers,"U S Neas and World Report, ltly 19,lY/b. D f,/Anastasia Wang's Index ro Computer-BasedLearning is available from the Jnstructional MediaLaboratory at the University of Wisconsin atMilwaukee. ElContinuedfrom page )0possible, and also that the video segmentsall began prematurely as a result of thetape rewind that occurred after theblocks had originally been marked off. Iwas able to partially correct the latterproblem by redoing the video blocking,this time anticipating the rewind lag byletting the tape play on for about asecond before stopping it. The frnal resultwas acceptable, but as noted-Previously,this problem would not have occurred atall had the work been done with videodiscinstead ofvideo tape.ConclusionAlthough the project was ratherlimited, it was shown that computer/video interface was workable and thatsoftware exists which will allow someonewith minimal cjrmputer skills to designand implemen-[ an interactive lessonwithout undue effort and frustration.Furthermore, it appears thatthe mediumcould be usefully exploited by ESL instructors.The lecture analysis/listeningcomprehension format opted for hereis only one possibility for lesson development.Any concept which is difficult tocontextualize in the classroom would be asuitable subject for an interactive videolesson.Use of interactive video is certainlyconsistent with recent theories oflanguage acquisition, especially withtheories recommending engaging bothhemispheres of the brain in the learningprocess. In addition, utilization of intelligentvideo meets needs for more per'sonalized instruction. Demand formaterials appropriate to computerizedvideo should increase as the availability ofsystem comPonents is improved, althoughthis may present a hardship for teacherswho frnd it hard to adapt to the designparadigms best suited to the newtechnologies.In spite of the limited success reportedhere in creating a video tape/CAI lessonto be used with ESL students, it may bethat the video tape medium is fatallyflawed. Videodisc, on the other hand, hasfewer technical lirnitations. As the priceof the components involved and theprice of producing and mastering thevideodiscs themselves declines, this maybe considered to be too powerful amedium to be ignored by educators.Therefore, it would behoove educators tolearn what they can about interactivevideo in order to be ready to imaginativelytake advantage of the uniquepotential inherent in intelligent videosystems when they do finally becomewidely available.REFERENCESAllen, Brockenbrough S. 1981. The video-computernexus: towards an agenda for instructionaldevelopment. Journal of Educational TechnologySystems 10, 2:81-99.Bork, Alfred. 1981. Educational technology andthe future. Journal of Educational TechnologySystems 10, l:3-20.DeBloois, Michael. 1979. Exploring new designmodels. Educational and Industrial Television11,5:34-36.Hallgren, Richard C. 1980. Interactive control of avideocassette recorder with a personal computer.Byte 5, 7:l16-134.Kadesch, R, R. 19E1. Interactive video computerlearning in physics. Journal of EducationalTechnology Systems 9, 4:291-301.Kehrberg, Kent T. and Richard A. Pollack. 1982.Videodiscs in the classroom: an interactive economicscoursee, Creative Computing 8, l:98-102.Kellner, Charlie. 1982. V is for videodisc: usinga videodisc with Apple SuperPilot. CreativeComputing E, I :105-105.Leveridge, Leo L. 1979. The potential of interactiveoptical videodisc systems for continuingeducation. Educational and industrial Televisionll,4:35-38.Molnar, Andrew R. 1979. Intelligent videodisc andthe learning society. Journal of Computer-BasedInstruction 6, I :l I -16.Nugent, Gwen. 1979. Videodiscs and ITV: thepossible vs. the practical. Educational andIndustrial Television I 1, 8:54-56.Onosko, Tim. 19E2. Visions of the future. CreativeComputing 8, l:84-94.Santoro, Ralph P. and Richard Pollack. 1980. Controllingfor the computer video environment: acomputer augmented video education experience.In ADCIS, Computer-Based Instruction: ANew Decade (1980 Conference Proceedings): 45-50.Woolley, Robert D. 1979. Microcomputers andvideodiscs: new dimensions for computer-basededucation. Interface Agent, 12:78-82. filAs part of a research project onEnglish-Persian computer-aidedlexicography, a system called 'Farsi' hasbeen developed at the University ofExeter, which produces Farsi (Persian)script on a 'Qume' daisy wheel printer. Itaccepts mixed English/Persian texts asinput and prints them simultaneously.The character set contains all of the Farsiletters, all diacritics and some special lettercombinations. The input text isprepared in single codes and the shape ofletters in connection with their contextualpositions is decided by the system software,which also takes care of theirproportional spacing and special combinations.Further information fromS.M. Assi, The Language Centre,University of Exeter, Queen's Building,The Queen's Drive, Exeter EX4 4qH,U.K.50