Progress of the World's Women 2005: Women, Work ... - UN Women

Progress of the World's Women 2005: Women, Work ... - UN Women

Progress of the World's Women 2005: Women, Work ... - UN Women

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

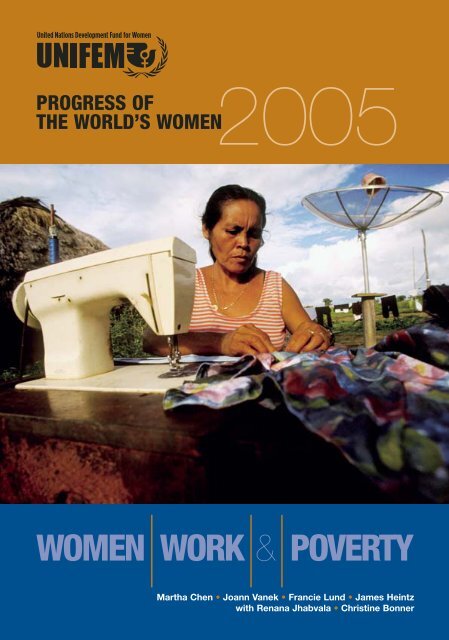

PROGRESS OFTHE WORLD’S WOMEN<strong>2005</strong>WOMEN | WORK | & | POVERTYMartha Chen • Joann Vanek • Francie Lund • James Heintzwith Renana Jhabvala • Christine Bonner

<strong>UN</strong>IFEM is <strong>the</strong> women’s fund at <strong>the</strong> United Nations. It provides financial and technicalassistance to innovative programmes and strategies to foster women’s empowermentand gender equality. Placing <strong>the</strong> advancement <strong>of</strong> women’s human rights at <strong>the</strong> centre<strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> its efforts, <strong>UN</strong>IFEM focuses on reducing feminized poverty; ending violenceagainst women; reversing <strong>the</strong> spread <strong>of</strong> HIV/AIDS among women and girls; and achievinggender equality in democratic governance in times <strong>of</strong> peace as well as war.The views expressed in this publication are those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> authors and do not necessarilyrepresent <strong>the</strong> views <strong>of</strong> <strong>UN</strong>IFEM, <strong>the</strong> United Nations or any <strong>of</strong> its affiliated organizations.<strong>Progress</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World’s <strong>Women</strong> <strong>2005</strong>: <strong>Women</strong>, <strong>Work</strong> and PovertyCopyright © <strong>2005</strong> United Nations Development Fund for <strong>Women</strong>ISBN: 1-932827-26-9United Nations Development Fund for <strong>Women</strong>304 East 45th Street, 15th floorNew York, NY 10017USATel: 212-906-6400Fax: 212-906-6705E-mail: unifem@undp.orgWebsite: www.unifem.orgOn <strong>the</strong> cover:Indigenous woman, home-based seamstress, Roraima Province, Brazil. Photo: Gerd Ludwig/Panos

PROGRESS OFTHE WORLD’S WOMEN<strong>2005</strong>WOMEN | WORK | & | POVERTYMartha Chen • Joann Vanek • Francie Lund • James Heintzwith Renana Jhabvala • Christine Bonner

Advisory TeamDebbie BudlenderCommunity Agency for Social EnquiryCape Town, South AfricaDiane ElsonUniversity <strong>of</strong> EssexColchester, EssexUnited KingdomGuadalupe EspinosaInstitute <strong>of</strong> Social DevelopmentMexico City, MexicoNoeleen HeyzerExecutive Director<strong>UN</strong>IFEMNew York, NY, USASelim JahanBureau <strong>of</strong> Development Policy - <strong>UN</strong>DPNew York, NY, USAFrancesca Perucci<strong>UN</strong> Statistics DivisionNew York, NY, USAAnne TrebilcockILOGeneva, Switzerland2<strong>Progress</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World’s <strong>Women</strong> <strong>2005</strong>Data Analysis TeamsCanada:Leah Vosko and Sylvia FullerYork UniversityTorontoCosta Rica:Jesper VenemaILO Regional OfficePanama CityEgypt:Mona Amer and Alia El MahdiUniversity <strong>of</strong> CairoCairoEl Salvador:Edgar Lara López, Reinaldo Chanchán,Sara GammageFundación Nacional para el DesarrolloSan SalvadorGhana:James HeintzPolitical Economy Research InstituteUniversity <strong>of</strong> MassachusettsAmherst, Mass.India:Jeemol UnniNational Commission for Enterprises in <strong>the</strong>Unorganized SectorNew DelhiSouth Africa:Daniela Casale, Colette Muller, Dorrit PoselUniversity <strong>of</strong> KwaZulu NatalDurbanEditor: Karen Judd, <strong>UN</strong>IFEMConsulting Editor: Gloria JacobsCopyeditors: Tina Johnson, Anna GrossmanProduction: Barbara Adams, Nanette Braun, Jennifer Cooper, Hea<strong>the</strong>r Tilbury, <strong>UN</strong>IFEMDesign: VanGennep DesignCover design: Cynthia RhettPrinting: ProGraphics

Contents5 Acknowledgements6 Preface8 Overview: <strong>Women</strong>, <strong>Work</strong> and Poverty14 Chapter 1: Employment and Poverty ReductionPoverty and Gender Inequality in <strong>the</strong> 21 st CenturyEmployment in <strong>the</strong> 21 st CenturyEmployment in <strong>the</strong> MDGs and PRSPsOrganization <strong>of</strong> this Report22 Chapter 2: The Totality <strong>of</strong> <strong>Women</strong>’s <strong>Work</strong>Understanding and Measuring <strong>Women</strong>’s <strong>Work</strong>Mapping <strong>Women</strong>’s Paid and Unpaid <strong>Work</strong>The Dynamics <strong>of</strong> <strong>Women</strong>’s Paid and Unpaid <strong>Work</strong>Gender and O<strong>the</strong>r Sources <strong>of</strong> Disadvantage: Implications for Poverty Reduction36 Chapter 3: Employment, Gender and PovertyInformal Employment: Definition and Recent DataMillennium Development Goal 3: Recommended Employment IndicatorsLabour Force Segmentation, Earnings and Poverty: Developed Country DataLabour Force Segmentation, Earnings and Poverty: New Data from Developing CountriesLabour Markets and Labour Force StatisticsTable Notes58 Chapter 4: The Reality <strong>of</strong> <strong>Women</strong>’s Informal <strong>Work</strong>Nature <strong>of</strong> Informal <strong>Work</strong>Benefits <strong>of</strong> Informal <strong>Work</strong>Costs <strong>of</strong> Informal <strong>Work</strong>Close-up: Occupational GroupsA Causal Model <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Informal EconomyPoverty, Gender and Informal EmploymentContents374 Chapter 5: <strong>Women</strong>’s Organizing in <strong>the</strong> Informal EconomyBenefits <strong>of</strong> OrganizingIdentifying as <strong>Work</strong>ersStrategies and Forms <strong>of</strong> OrganizingInfluencing Policy Decisions: National, Regional and International Networks and AlliancesThe Next Stage86 Chapter 6: A Framework for Policy and ActionPolicy Debates on <strong>the</strong> Informal EconomyFramework for Policy and ActionClose-up: Good Practice CasesThe Way Forward105 References Cited111 About <strong>the</strong> Authors112 Index

Tables and Figures4<strong>Progress</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World’s <strong>Women</strong> <strong>2005</strong>28 Table 2.1:Risks and vulnerabilities associated with employment at differentstages <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> life cycle40 Table 3.1:Wage and self-employment in non-agricultural informal employment by sex,1994/200045 Table 3.2:Percentage distribution <strong>of</strong> women’s and men’s informal employment byemployment status46 Table 3.3:Percentage distribution <strong>of</strong> women’s and men’s formal employment by type47 Table 3.4:Hourly earnings as a percentage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hourly earnings <strong>of</strong> formal, private, nonagriculturalwage workers by employment status category48 Table 3.5:Average wages per worker and women’s share <strong>of</strong> employment for small andmicroenterprises by size, Egypt, 2003 (expressed in 2002 Egyptian pounds)48 Table 3.6:<strong>Women</strong>’s hourly earnings as a percentage <strong>of</strong> men’s hourly earnings49 Table 3.7:Hourly earnings in selected employment status categories, Ghana (in cedisand purchasing power parity adjusted U.S. dollars)50 Table 3.8:Average weekly hours <strong>of</strong> work by sex and employment status50 Table 3.9:Total hours worked per week in employment and unpaid care work,employed population (15+), Ghana, 1998/199951 Table 3.10:<strong>Work</strong>ing poor as a percentage <strong>of</strong> employment (15+) in selected employmentstatuses by sex, 2003, El Salvador52 Table 3.11:Relative poverty rates: working poor poverty rates by sex andemployment status category and formal and informal employment,as a percentage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poverty rate for formal, private non-agricultural wage workers53 Table 3.12:Poverty rates by household type, South Africa, 200353 Table 3.13:Poverty rates among persons in households sustaining <strong>the</strong>mselves oninformal income, urban India, 1999/200054 Figure 3.1:Segmentation <strong>of</strong> Informal Employment by Average Earnings and Sex54 Figure 3.2:Poverty Risk <strong>of</strong> Households by Sources <strong>of</strong> Income54 Figure 3.3:Poverty Risk <strong>of</strong> Households by Primary Source <strong>of</strong> Income

AcknowledgementsThe authors are deeply grateful to <strong>UN</strong>IFEM forcommissioning this report on informal employmentand <strong>the</strong> working poor, especially women,and <strong>the</strong>ir importance in efforts to eliminatepoverty. In particular, we want to express ourgratitude to Noeleen Heyzer, Executive Director,for her leadership, her interest and expertise onissues <strong>of</strong> women, work and poverty, and for hersubstantive and financial support, without which<strong>the</strong> report would not have been possible.We would also like to acknowledge JoanneSandler, <strong>UN</strong>IFEM Deputy Director for Programmefor her inputs and support and Meagan Bovell,Nisreen Alami, Leyla Sharafe and Ellen Houstonin <strong>UN</strong>IFEM’s Economic Security and Rights sectionfor research support. Special thanks are dueto Karen Judd, <strong>UN</strong>IFEM editor, and GloriaJacobs, consulting editor, who provided valuableinputs and shepherded <strong>the</strong> report to completion.O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>UN</strong>IFEM staff with whom we consultedinclude Meenakshi Ahluwalia, Aileen Allen,Letty Chiwara, Nazneen Damji, Sandra Edwards,Eva Fodor, Chandi Joshi, Yelena Kudryavtseva,Osnat Lubrani, Lucita Lazo, Firoza Mehrotra, ZinaMounla, Natasha Morales, Sunita Narain, GraceOkonji, Teresa Rodriguez, Amelia KinahoiSiamoumua, Damira Sartbaeva, Alice Shackelford,Stephanie Urdang, Marijke Velzeboer-Salcedo.Thanks also to <strong>UN</strong>IFEM interns Michael Montieland Inés Tófalo for translation <strong>of</strong> material inSpanish and to Marie-Michele Arthur and TracyCarvalho for <strong>the</strong>ir management <strong>of</strong> contracts andpayments.We would also like to express our thanks to<strong>the</strong> <strong>UN</strong>DP and <strong>the</strong> ILO for both substantiveadvice and additional financial support. In addition,Selim Jahan <strong>of</strong> <strong>UN</strong>DP and Anne Trebilcock<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ILO served on <strong>the</strong> Advisory Team and providedvaluable comments. Debbie Budlender, <strong>of</strong>CASE in South Africa; Diane Elson, coordinator <strong>of</strong><strong>UN</strong>IFEM’s first <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World’s <strong>Women</strong> in2000; and Guadalupe Espinoza, former <strong>UN</strong>IFEMRegional Programme Director in Mexico providedmany helpful comments. Ralf Hussmanns <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ILO provided statistical guidance and FrancescaPerucci <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UN</strong> Statistics Division providedadditional statistical inputs. O<strong>the</strong>r ILO staff withwhom we consulted include Amy King-DeJardin,Marie-Thérèse DuPré, Rakawin Lee, KatarinaTsotroudi, María Elena Valenzuela, Linda Wirthand Sylvester Young.Very special thanks are due to <strong>the</strong> members<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Data Analysis Teams who carried out <strong>the</strong>data analysis in seven countries for Chapter 3.Special thanks also to WIEGO team membersMarais Canali, who compiled references, wrotesome <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> good practice cases and assisted<strong>the</strong> authors throughout; Shalini Sinha, whoworked closely with <strong>the</strong> authors on Chapter 5;Anna Marriott, Cally Ardington and KudzaiMakomva, who assisted with research for differentchapters; and Suzanne Van Hook, who managed<strong>the</strong> contracts for <strong>the</strong> data analysis team.O<strong>the</strong>rs in <strong>the</strong> WIEGO network who were consultedon <strong>the</strong> cases studies featured in Chapters 5and 6 include K<strong>of</strong>i Asamoah, StephanieBarrientos, Ela Bhatt, Mirai Chatterjee, NicoleConstable, Dan Gallin, Pat Horn, Elaine Jones,Paula Kantor, Martin Medina, Winnie Mitullah,Pun Ngai, Fred Pieterson, Jennefer Sebstad,and Lynda Yanz.Finally, we would like to thank <strong>the</strong> workingpoor women and men around <strong>the</strong> world whoinspire our work.Martha Chen, Joann Vanek, Francie Lund,James Heintz, Renana Jhabvala,and Christine BonnerAcknowledgements5

Preface6<strong>Progress</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World’s <strong>Women</strong> <strong>2005</strong>The modern global economy is now a reality. Yeteverywhere in <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>the</strong>re are people workingin conditions that should no longer exist inthis 21st century, for income that is barelyenough for survival. Home-based workers putin long hours each day, yet are paid for only afraction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir time. Rural women spend backbreakinghours on family plots, <strong>of</strong>ten for no paymentat all. Those in urban areas work in unregulatedfactories, earning pennies for productsthat are shipped via sub-contractors to marketsfar away, or <strong>the</strong>y find jobs as waste-pickers,scavenging garbage heaps for items to sell. Theworking poor are both men and women.However, <strong>the</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r down <strong>the</strong> chain <strong>of</strong> qualityand security, <strong>the</strong> more women you find. Yet it is<strong>the</strong>ir work — including <strong>the</strong>ir unpaid work in <strong>the</strong>household as well as <strong>the</strong>ir poorly paid work ininsecure jobs or small enterprises — that holdsfamilies and communities toge<strong>the</strong>r.Informal workers are everywhere, in everycountry and region. Globalization has broughtnew opportunities for many workers, especiallythose who are well educated, with <strong>the</strong> skillsdemanded in <strong>the</strong> high-tech global economy. Butit has deepened insecurity and poverty for manyo<strong>the</strong>rs, including women, who have nei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>skills needed to compete nor <strong>the</strong> means toacquire <strong>the</strong>m. The lives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se working poorpeople are <strong>the</strong> message <strong>of</strong> this report: too many<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m, both women and men, are in unregulatedand insecure jobs, in conditions that are frequentlyunhealthy and <strong>of</strong>ten unsafe.Increasingly, ra<strong>the</strong>r than informal workbecoming formalized as economies grow, workis moving from formal to informal, from regulatedto unregulated, and workers lose job security aswell as medical and o<strong>the</strong>r benefits. What we areseeing is that growth does not automatically‘trickle down’ to <strong>the</strong> poor. It can in fact widen <strong>the</strong>gap between rich and poor. As globalizationintensifies, <strong>the</strong> likelihood <strong>of</strong> obtaining formalemployment is decreasing in many places, with“footloose” companies shifting production fromone unregulated zone to an even less regulatedone elsewhere, employing workers in informalcontract or casual work with low earnings and littleor no benefits.In many developing countries, with <strong>the</strong> collapse<strong>of</strong> commodity prices and <strong>the</strong> persistence<strong>of</strong> agricultural subsidies in rich countries, manyrural communities are disintegrating, forcing bothwomen and men into <strong>the</strong> informal economy. Thatis partly <strong>the</strong> reason why, in developing countries,informal employment comprises from 50 to 80per cent <strong>of</strong> total non-agricultural employment.When agricultural workers such as c<strong>of</strong>fee harvestersor cocoa growers who are unable tocompete in <strong>the</strong> world market are included, <strong>the</strong>percentage <strong>of</strong> informal workers is dramaticallyhigher. In nearly all developing countries (exceptfor North Africa) <strong>the</strong> proportion <strong>of</strong> workingwomen in informal employment is greater than<strong>the</strong> proportion <strong>of</strong> working men: over 60 per cent<strong>of</strong> working women are in informal employmentoutside <strong>of</strong> agriculture.<strong>Women</strong> workers are not only concentrated in<strong>the</strong> informal economy, <strong>the</strong>y are in <strong>the</strong> more precariousforms <strong>of</strong> informal employment, whereearnings are <strong>the</strong> most unreliable and <strong>the</strong> mostmeagre. While in some instances, <strong>the</strong>ir incomecan be important in helping families move out <strong>of</strong>poverty, this is only true if <strong>the</strong>re is more than oneearner. This is a sobering fact to consider as weredouble our efforts to implement <strong>the</strong> MillenniumDevelopment Goals, including <strong>the</strong> elimination <strong>of</strong>poverty and <strong>the</strong> achievement <strong>of</strong> gender equality.Not achieving <strong>the</strong>se goals is unthinkable.Widening gaps between rich and poor, andwomen and men can only contribute to greaterinstability and insecurity in <strong>the</strong> world.And this is <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r message <strong>of</strong> this report:decent work is a basic human right, one thatgovernments, corporations and international policymakerscan make a reality for all working people.Change is possible, and innovative solutionsare already being acted upon. This report showshow and where change has happened, anddescribes how governments, <strong>UN</strong> and NGO partnersand socially responsible corporations canwork toge<strong>the</strong>r to ensure that informal workers,especially women, receive an equitable return for<strong>the</strong>ir labour.To make this happen, four things need to bemade a priority:First, organizing women informal workers toobtain legal and social protection. Unless womenare empowered to demand services, protectionand <strong>the</strong>ir rights, <strong>the</strong> basic structures that govern<strong>the</strong>ir lives will not change. <strong>Women</strong> acting alonecan only bring about limited change. This<strong>the</strong>refore means supporting women’s organizing,along with unions and member-based workers’organizations, to ensure that more workers receive<strong>the</strong> labour rights to which <strong>the</strong>y are entitled.Second, for <strong>the</strong> self-employed, greater effortmust be made to deliver services to <strong>the</strong>se workers,to improve access to credit and financial

markets and to mobilize demands for <strong>the</strong>ir productsand services. <strong>Women</strong>’s skills and assetsmust be upgraded so <strong>the</strong>y can compete moreeffectively in <strong>the</strong>se markets. In Burkina Faso, wesaw firsthand <strong>the</strong> difference that skills can make.<strong>UN</strong>IFEM helped women who produced shea butterlearn how to improve <strong>the</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir product.This in turn helped <strong>the</strong>m move up <strong>the</strong> valuechain, establishing a specialized, niche marketfor <strong>the</strong>ir product that is now bought by corporationsat better prices than <strong>the</strong> women werereceiving previously.Third, <strong>the</strong>re must be appropriate policies insupport <strong>of</strong> informal workers. This requires thatinformal workers are visible and that <strong>the</strong> totality<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir work — especially in <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> women— is valued. The starting point for meaningfulpolicy decisions is to make women’s informalwork visible through gender-sensitive, disaggregatedstatistics on national labour forces. Thisdata must be developed, analysed and used increating policy that focuses on economic securityand rights.Finally, <strong>the</strong>re is a need to streng<strong>the</strong>n strategiesthat can transform basic structures that perpetuategender inequality. What kind <strong>of</strong> globalrules are required to regulate markets, and guide<strong>the</strong> priorities <strong>of</strong> international economic institutionstowards globalization that improves livesand working conditions? Closing <strong>the</strong> genderincome gaps, ensuring safe and healthy workingconditions for all, must be central to policy andrule-setting. Socially responsible corporationscan lead <strong>the</strong> way in this. At <strong>the</strong> same time, allcorporations can be held accountable throughstandard-setting and <strong>the</strong> independent monitoringand verification that are a necessary part <strong>of</strong>implementation.This report is a call to action to achieve <strong>the</strong>goals outlined here. Advocates and <strong>the</strong> workingpoor <strong>the</strong>mselves have done much to improveconditions already and to ensure that <strong>the</strong> workingpoor in <strong>the</strong> informal economy remain on <strong>the</strong>international agenda. Socially responsible campaignsand ethical marketing initiatives havehelped to raise awareness around <strong>the</strong> importance<strong>of</strong> better working conditions for informalworkers. The Clean Clo<strong>the</strong>s Campaign and <strong>the</strong><strong>Women</strong>’s Principles, a set <strong>of</strong> goals for corporationsthat use sub-contractors or run factories indeveloping countries, created by <strong>the</strong> CalvertInvestment Group, working with <strong>UN</strong>IFEM, arepart <strong>of</strong> an effort by consumers in developedcountries to insist that <strong>the</strong> goods <strong>the</strong>y buy becreated under humane conditions. Governmentsare also recognizing <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> protecting<strong>the</strong> lives and well-being <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir citizens —<strong>the</strong>ir human capital — and have insisted thatcertain standards be maintained and minimumwages paid.These efforts should not be <strong>the</strong> work only <strong>of</strong>socially responsible companies, or concernedconsumers, or <strong>of</strong> organizations <strong>of</strong> informal workers.Corporations and entities active in <strong>the</strong> globalmarketplace must alter <strong>the</strong>ir policies to “makepoverty history.” Advocates can use <strong>the</strong> toolsprovided in this report to reach beyond <strong>the</strong>ir coreconstituencies. They can assess <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong>economic policies on women and men and insiston those that <strong>of</strong>fer concrete solutions to <strong>the</strong>deplorable conditions prevalent in <strong>the</strong> informaleconomy.Noeleen HeyzerExecutive Director, <strong>UN</strong>IFEMPreface7

Overview: <strong>Women</strong>, <strong>Work</strong>and Poverty8<strong>Progress</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World’s <strong>Women</strong> <strong>2005</strong><strong>2005</strong> marks <strong>the</strong> fifth anniversary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UN</strong>Millennium Declaration, adopted in 2000 and <strong>the</strong>tenth anniversary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Beijing Platform forAction in 1995. In <strong>the</strong> decade since Beijing, <strong>the</strong>number <strong>of</strong> people living on less than $1 a day hasfallen; <strong>the</strong> gender gap in primary and (to a lesserextent) secondary education has been reduced;and women enjoy greater participation in electedassemblies and state institutions. In addition,women are a growing presence in <strong>the</strong> labourmarket– <strong>the</strong> global indicator used to approximatewomen’s economic status (<strong>UN</strong> <strong>2005</strong>).However, <strong>the</strong> decline in overall povertymasks significant differences not only betweenbut also within regions. Asia experienced <strong>the</strong>greatest decline in extreme poverty, followed byLatin America, but sub-Saharan Africa experiencedan increase. Even where <strong>the</strong> numbers <strong>of</strong>extremely poor people have declined, notablyChina and India, poverty persists in differentareas and social groups, reflected in risinginequalities (<strong>UN</strong> <strong>2005</strong>).For women, progress, while steady, hasbeen painfully slow. Despite increased parity inprimary education, disparities are still wide insecondary and tertiary education—both increasinglykey to new employment opportunities. Andwhile women’s share <strong>of</strong> seats in parliament haveinched up in all regions, women still hold only 16per cent <strong>of</strong> parliamentary seats worldwide.Finally, although women have entered <strong>the</strong> paidlabour force in great numbers, <strong>the</strong> result in terms<strong>of</strong> economic security is not clear. According to<strong>the</strong> United Nations’ Millennium DevelopmentGoals Report <strong>2005</strong>: “<strong>Women</strong>’s access to paidemployment is lower than men’s in most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>developing world…. <strong>Women</strong> are less likely thanmen to hold paid and regular jobs and more <strong>of</strong>tenwork in <strong>the</strong> informal economy, which provides littlefinancial security” (<strong>UN</strong> <strong>2005</strong>).Today’s global world is one <strong>of</strong> wideningincome inequality and for many, increasing economicinsecurity. Informal employment, far fromdisappearing, is persistent and widespread. Inmany places, economic growth has dependedon capital-intensive production in a few sectorsra<strong>the</strong>r than on increasing employment opportunities,pushing more and more people into <strong>the</strong>informal economy. In o<strong>the</strong>rs, many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> jobsgenerated by economic growth are not coveredby legal or social protection, as labour marketsare de-regulated, labour standards are relaxedand employers cut costs (see Chapter 4). As aresult, a growing share <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> workforce in bothdeveloped and developing countries is not coveredby employment-based social and legal protection.Moreover, in <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> economicgrowth and trade liberalization, some informalworkers get left behind altoge<strong>the</strong>r. This includeswage workers who lose <strong>the</strong>ir jobs when companiesmechanize, retrench or shift locations. It alsoincludes <strong>the</strong> smallest-scale producers andtraders who have little if any access to governmentsubsidies, tax rebates or promotionalmeasures to help <strong>the</strong>m compete in export marketsor against imported goods. These ‘losers’ in<strong>the</strong> global economy have to find ways to survivein <strong>the</strong> local economy, many resorting to suchoccupations as waste picking or low-end streettrading.<strong>Progress</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World’s <strong>Women</strong> <strong>2005</strong> makes<strong>the</strong> case that streng<strong>the</strong>ning women’s economicsecurity is critical to efforts to reduce poverty andpromote gender equality, and that decent work isbasic to economic security. It provides data toshow that:■ <strong>the</strong> proportion <strong>of</strong> women workers engaged ininformal employment is generally greater than<strong>the</strong> proportion <strong>of</strong> men workers;■ women are concentrated in <strong>the</strong> more precarioustypes <strong>of</strong> informal employment; and■ <strong>the</strong> average earnings from <strong>the</strong>se types <strong>of</strong> informalemployment are too low, in <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r sources <strong>of</strong> income, to raise householdsout <strong>of</strong> poverty.The report concludes that unless efforts aremade to create decent work for <strong>the</strong> global informalworkforce, <strong>the</strong> world will not be able to eliminatepoverty or achieve gender equality.Statistical FindingsStatistics from a variety <strong>of</strong> developing countriesshow that, despite differences in size, geographiclocation and income level, fully 50 to 80 percent <strong>of</strong> non-agricultural employment is informal.Between 60 and 70 per cent <strong>of</strong> informal workersin developing countries are self-employed,including employers, own-account workers andunpaid contributing family workers in familyenterprises (ILO 2002b). The remaining 30 to 40per cent are informal wage workers, including <strong>the</strong>employees <strong>of</strong> informal enterprises, casual day

labourers, domestic workers and industrial outworkers.In terms <strong>of</strong> earnings, average earnings arehigher in formal employment than in informalemployment and in non-agriculture than in agricultureactivities. Average earnings also varyacross segments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> informal labour force.Informal wage employment is generally superiorto informal self-employment. However, a hierarchyexists: informal employers have <strong>the</strong> highestaverage earnings followed by <strong>the</strong>ir employees,<strong>the</strong>n own-account workers, and <strong>the</strong>n casualwage workers and domestic workers. Relatedstatistical analyses have found that industrialoutworkers have <strong>the</strong> lowest average earnings <strong>of</strong>all (Charmes and Lekehal n.d.; Chen andSnodgrass 2001).The risk <strong>of</strong> poverty is lower in formal employmentrelative to informal employment and in nonagriculturalemployment relative to agriculturalemployment. The risk <strong>of</strong> poverty also variesacross segments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> informal labour force.Generally, informal wage workers – with <strong>the</strong>exception <strong>of</strong> domestic workers, casual wageworkers, and industrial outworkers – have lowerpoverty risk than own account workers.Gender inequality in employment has multipledimensions. First, women are concentrated inmore precarious forms <strong>of</strong> employment in whichearnings are low. In developed countries, womencomprise <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> part-time and temporaryworkers.In developing countries, except in those withlarge low-wage export sectors, women typicallyaccount for a relatively small share <strong>of</strong> informalwage employment. However, informal employmentgenerally represents a larger source <strong>of</strong>employment for women than formal employmentand a greater share <strong>of</strong> women’s employmentthan men’s employment. In developing countriesover 60 per cent <strong>of</strong> women workers are in informalemployment outside <strong>of</strong> agriculture—far moreif agriculture is included. The exception is NorthAfrica, where 43 per cent <strong>of</strong> women workers, anda slightly higher per cent <strong>of</strong> men workers, areinformally employed.Within <strong>the</strong> informal economy, women areconcentrated in work associated with low andunstable earnings and with high risks <strong>of</strong> poverty.Outside <strong>of</strong> agriculture, women are more likelythan men to be own account workers, domesticworkers, unpaid contributing workers in familyenterprises and industrial outworkers. A significantproportion <strong>of</strong> women working in agricultureare also unpaid contributing workers on <strong>the</strong> familyfarm.Second, within employment categories,women’s hourly and monthly earnings are generallylower than men’s. A gender gap in earningsexists across almost all employment categories –including informal wage employment and selfemployment.A few exceptions exist among publicsector employees in certain countries, such asEl Salvador, and in cases like Egypt where most<strong>of</strong> women’s employment involves unpaid workon family enterprises and <strong>the</strong> few women who doparticipate in paid employment tend to be highlyeducated. In <strong>the</strong>se exceptional cases, women’saverage hourly earnings can be higher thanmen’s.Third, in <strong>the</strong> countries for which data areavailable, women work fewer hours on average inpaid work than do men. In part, this is due towomen’s long hours in unpaid household labour.Responsibilities for unpaid household work alsoreinforce labour force segmentation – womencan be restricted to own-account or home-basedemployment, even if <strong>the</strong>y have to work longerhours and earn less than <strong>the</strong>y would in o<strong>the</strong>rtypes <strong>of</strong> employment.Finally, despite <strong>the</strong> low earnings and precariousnature <strong>of</strong> much <strong>of</strong> women’s paid work, inboth developed and developing countries,women’s labour force participation can help keepa family out <strong>of</strong> poverty – provided <strong>the</strong>re are additionalsources <strong>of</strong> family income.Research FindingsThe links between work and poverty reflect notonly how much women and men earn but how<strong>the</strong>y earn it and for how long. Each place <strong>of</strong> workis associated with specific costs, risks and benefits,depending variously on security <strong>of</strong> sitetenure, costs <strong>of</strong> securing it, access to neededinfrastructure, such as light, water, toilets, storage,garbage removal, etc.; access to customersand suppliers; ability <strong>of</strong> informal workers toorganize; and <strong>the</strong> different risks and hazardsassociated with <strong>the</strong> site.Several broad categories <strong>of</strong> informal workerscan be distinguished according to <strong>the</strong>iremployment relations: employers, <strong>the</strong>ir employees,own account workers who do not hire o<strong>the</strong>rs,unpaid contributing family workers, casualOverview9

10<strong>Progress</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World’s <strong>Women</strong> <strong>2005</strong>wage workers and industrial outworkers.Industrial outworkers, <strong>the</strong> vast majority <strong>of</strong> whomare women, lack firm contracts, have <strong>the</strong> lowestaverage earnings and <strong>of</strong>ten are not paid formonths on end. The small amount and insecurity<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir income is exacerbated by <strong>the</strong> fact that<strong>the</strong>y have to pay for non-wage costs <strong>of</strong> production,such as workplace, equipment and utilities(ILO 2002b; Carr et al. 2000).The modern industrial system has notexpanded as fully in developing countries as itonce did in developed countries. In many developingcountries industrial production takes place inmicro and small units, in family businesses or insingle person units, while traditional personalizedsystems <strong>of</strong> production and exchange still obtain inagricultural and artisan production. But in today’sglobalizing economy, both traditional and semiindustrialrelations <strong>of</strong> production and exchange arebeing inserted into or displaced by <strong>the</strong> global system<strong>of</strong> production. Authority and power tend to getconcentrated in <strong>the</strong> top links <strong>of</strong> value chains or diffusedacross firms in complex networks, making itdifficult for micro-entrepreneurs to gain access,compete and bargain and for wage workers to bargainfor fair wages and working conditions. Highlycompetitive conditions among small-scale suppliersand <strong>the</strong> significant market power <strong>of</strong> transnationalcorporations mean that <strong>the</strong> lion’s share <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>value produced across <strong>the</strong>se value chains is capturedby <strong>the</strong> most powerful players.For <strong>the</strong> rest—those who can’t compete—some may become suppliers in <strong>the</strong>se chains ornetworks, o<strong>the</strong>rs struggle as subcontractorswhile still o<strong>the</strong>rs are forced to hire out <strong>the</strong>ir labourto subcontractors. In today’s global economy, itis hard to imagine a greater physical and psychologicaldistance, or a greater imbalance – interms <strong>of</strong> power, pr<strong>of</strong>it and life-style – than thatbetween <strong>the</strong> woman who stitches garments orsoccer balls from her home in Pakistan for abrand-name retailer in Europe or North Americaand <strong>the</strong> chief executive <strong>of</strong>ficer (CEO) <strong>of</strong> thatbrand-name corporation.The consequences <strong>of</strong> working informally g<strong>of</strong>ar beyond <strong>the</strong> income dimensions <strong>of</strong> poverty toinclude lack <strong>of</strong> human rights and social inclusion.Compared to those who work in <strong>the</strong> formal economy,those who work in <strong>the</strong> informal economyare likely:■ to have less access to basic infrastructure andsocial services;■ to face greater exposure to common contingencies(e.g., illness, property loss, disabilityand death);■ to have less access to <strong>the</strong> means to address<strong>the</strong>se contingencies (e.g., health, property, disabilityor life insurance);■ to have, as a result, lower levels <strong>of</strong> health, educationand longevity;■ to have less access to financial, physical ando<strong>the</strong>r productive assets;■ to have fewer rights and benefits <strong>of</strong> employment;■ to have less secure property rights over land,housing or o<strong>the</strong>r productive assets; and■ to face greater exclusion from state, marketand political institutions that determine <strong>the</strong>‘rules <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> game’ in <strong>the</strong>se various spheres.Toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>se costs take an enormous toll on <strong>the</strong>financial, physical and psychological well-being<strong>of</strong> many informal workers and <strong>the</strong>ir families.New Analytical Tools and PromisingExamplesThis report <strong>of</strong>fers several new conceptual andmethodological frameworks that provide freshinsights into <strong>the</strong> links among informal employment,poverty and gender inequality and serve asa basis for future research. These include:■ an analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> linkages between <strong>the</strong> genderdivision <strong>of</strong> labour, women’s unpaid work andinformal paid work along different dimensions(Chapter 2);■ a framework based on <strong>the</strong> proposed newemployment indicators for Millennium DevelopmentGoal 3; analysing differences by sex intypes <strong>of</strong> employment and earnings (Chapter 3);■ a statistical method for assessing <strong>the</strong> ‘povertyrisk’ <strong>of</strong> different employment statuses by sex,linking national labour force and householdincome data to show <strong>the</strong> links between gender,employment and poverty risk (Chapter 3);■ an expanded definition and a multi-segmentedmodel <strong>of</strong> labour markets that takes intoaccount labour market structures in developingcountries and changing employment relationsin developed countries (Chapter 3);■ a typology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> costs – both direct and indirect– <strong>of</strong> informal employment that can be usedto carry out a full accounting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> social anddistributional outcomes <strong>of</strong> different types <strong>of</strong>informal work (Chapter 4);■ a causal model <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> informal economy, whichposits that some people operate informally bychoice, o<strong>the</strong>rs do so out <strong>of</strong> necessity, and stillo<strong>the</strong>rs do so because <strong>of</strong> tradition (e.g., hereditaryoccupations) (Chapter 4);■ a new policy analysis tool, modelled on genderbudget analysis, called informal economybudget analysis (Chapter 6).

To ensure that appropriate policies, institutionsand services are put in place, <strong>the</strong> informalworkforce needs to be visible to policy makersand government planners. To date, relatively fewcountries have comprehensive statistical data on<strong>the</strong> informal economy, and <strong>the</strong> collection <strong>of</strong> suchdata needs to be given greater priority. Morecountries need to collect statistics on informalemployment in <strong>the</strong>ir labour force surveys, andcountries that already do this need to improve<strong>the</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> statistics <strong>the</strong>y collect. Moreover,data that is collected needs to be analysed tobring out <strong>the</strong> linkages between informal employment,poverty and gender equality, as done for<strong>the</strong> first time for seven countries in this report.There are many promising examples <strong>of</strong> whatcan and should be done to help <strong>the</strong> working poor,especially women, minimize <strong>the</strong> costs and maximize<strong>the</strong> benefits <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir work. This report featuresa selection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se. They come from allregions and are initiated by governments as wellas civil society and <strong>the</strong> private sector, women’sorganizations as well as labour organizations, anddemonstrate <strong>the</strong> power <strong>of</strong> working in partnership.Future DirectionsThe overarching future policy goal is to stop <strong>the</strong>ongoing generation <strong>of</strong> informal, insecure andbadly paid employment alongside <strong>the</strong> constriction<strong>of</strong> formal employment opportunities. Thisrequires expanding formal employment opportunities,formalizing informal enterprises and jobs,and increasing <strong>the</strong> returns to <strong>the</strong>ir labour <strong>of</strong> thosewho work in <strong>the</strong> informal economy. For labourand women’s rights advocates it meansdemanding a favourable policy environment andspecific interventions in order to increase economicopportunities, social protection, and representativevoice for <strong>the</strong> working poor, especiallywomen, in <strong>the</strong> informal economy.A favourable policy environmentBoth poverty reduction and gender equalityrequire an economic policy environment thatsupports, ra<strong>the</strong>r than ignores, <strong>the</strong> working poor.Most (if not all) economic and social policies –both macro and micro – affect <strong>the</strong> lives and work<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> working poor in various direct ways:■ as workers■ as consumers■ as users <strong>of</strong> infrastructure, finance and property,including urban space and naturalresources■ as potential recipients <strong>of</strong> tax-funded servicesor transfers (World Bank <strong>2005</strong>a).Economic policies that discount <strong>the</strong> real-lifestructure and behaviour <strong>of</strong> labour markets cannotbe assumed to be neutral towards labour.Similarly, economic policies that ignore <strong>the</strong> factthat most unpaid care work is done by womencannot be assumed to be neutral towardswomen’s labour in particular. Economic plannersmust take into account <strong>the</strong> size, composition andcontribution <strong>of</strong> both <strong>the</strong> formal and informallabour forces in different countries and recognizethat policies have differential impacts on formaland informal enterprises and workers, and onwomen and men within <strong>the</strong>se categories. Toassess how economic policies affect <strong>the</strong> workingpoor, it is important to analyse how class, genderand o<strong>the</strong>r biases intersect in labour markets.More specifically, it is important to identify inherentbiases in favour <strong>of</strong> capital (over labour), formalenterprises (over informal enterprises), formallabour (over informal labour) and men (overwomen) within each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se categories.A new tool, informal economy budget analysis,modelled on gender-responsive budget analysis, isdesigned to assess whe<strong>the</strong>r and how <strong>the</strong> allocation<strong>of</strong> resources by government at different levels(local, provincial/ state and national/ federal) andacross different ministries or departments (trade,labour, housing, health) serves to (a) lower or raise<strong>the</strong> costs <strong>of</strong> those working informally, and (b) provideor deny access to benefits that could help<strong>the</strong>m grow <strong>the</strong>ir enterprises and o<strong>the</strong>rwise takesteps along <strong>the</strong> path to steady and secureincomes. Used in conjunction with gender-responsivebudget analysis, informal economy budgetanalysis can also shed light on <strong>the</strong> intersection <strong>of</strong>gender and o<strong>the</strong>r sources <strong>of</strong> disadvantage (byclass, ethnicity or geography) in <strong>the</strong> realm <strong>of</strong> work.Targeted interventionsIn addition to a favourable policy environment,targeted interventions are required to address <strong>the</strong>costs <strong>of</strong> working informally. These should aim:■ To increase <strong>the</strong> assets, access and competitiveness<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> working poor, both self-employedand wage employed, in <strong>the</strong> informal economyFor <strong>the</strong> working poor to be able to takeadvantage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> opportunities <strong>of</strong>fered by a morefavourable policy environment, <strong>the</strong>y need greatermarket access as well as <strong>the</strong> relevant resourcesand skills with which to better compete in markets.Over <strong>the</strong> past three decades, <strong>the</strong>re hasbeen a proliferation <strong>of</strong> projects designed to providemicr<strong>of</strong>inance and/or business developmentservices to microenterprises. While <strong>the</strong> vastmajority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> clients <strong>of</strong> micr<strong>of</strong>inance are work-Overview11

12<strong>Progress</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World’s <strong>Women</strong> <strong>2005</strong>ing poor women, business development servicesare not typically targeted at <strong>the</strong> smallest enterprises,particularly those run by women. Futuremicr<strong>of</strong>inance and business development servicesneed to target working poor women moreexplicitly, and with context-specific and userfriendlyservices.■ To improve <strong>the</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> trade for <strong>the</strong> workingpoor, especially women, in <strong>the</strong> informal economyTo compete effectively in <strong>the</strong> markets, inaddition to having <strong>the</strong> requisite resources andskills, <strong>the</strong> working poor need to be able to negotiatefavourable terms <strong>of</strong> trade. This involveschanging government policies, government-setprices or institutional arrangements as well as<strong>the</strong> balance <strong>of</strong> power within markets or valuechains. This requires that <strong>the</strong> working poor, especiallywomen, have bargaining power and areable to participate in <strong>the</strong> negotiations that determine<strong>the</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> trade in <strong>the</strong> sectors withinwhich <strong>the</strong>y work. Often what is effective in thisregard is joint action by organizations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>working poor and like-minded allies who canleverage access to government policy makersand to rule-setting institutions.■ To secure appropriate legal frameworks for <strong>the</strong>working poor, both self-employed and wageemployed, in <strong>the</strong> informal economy<strong>Work</strong>ers in <strong>the</strong> informal economy, especially<strong>the</strong> poor, need legal recognition as workers and<strong>the</strong> legal entitlements that come with that recognition,including <strong>the</strong> right to work (e.g., to vend inpublic spaces), rights at work and rights to property.Strategies to secure <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> womeninformal wage workers include internationallabour standards and conventions; nationallabour legislation; corporate codes <strong>of</strong> conduct;and collective bargaining agreements and grievancemechanisms.■ To address risk and uncertainty faced by poorworkers, especially women, in informalemploymentAll workers, and informal workers in particular,need protection against <strong>the</strong> risks and uncertaintiesassociated with <strong>the</strong>ir work as well as <strong>the</strong>common contingencies <strong>of</strong> illness, property loss,maternity and child care, disability and death.Providing needed protections requires a variety<strong>of</strong> interventions, including different safety nets(relief payments, cash transfers, public works);insurance coverage <strong>of</strong> various kinds (health,property, disability, life); and pensions or longtermsavings schemes. Governments, <strong>the</strong> privatesector, trade unions, non-governmental organizationsand o<strong>the</strong>r membership-based organizationscan all play active roles in providing socialprotection to informal workers.Support for organizing by womeninformal workersTo hold o<strong>the</strong>r players accountable to <strong>the</strong>sestrategic priorities, <strong>the</strong> working poor need to beable to organize and have representative voice inpolicy-making processes and institutions.Informal workers, especially women, cannotcount on o<strong>the</strong>r actors to represent <strong>the</strong>ir interestsin policy-making or programme planningprocesses, including national MillenniumDevelopment Goals reports and <strong>the</strong> PovertyReduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs). Securingthis seat at <strong>the</strong> decision-making table requiressupporting and streng<strong>the</strong>ning organizations <strong>of</strong>informal workers, with a special focus onwomen’s organizations and women’s leadership.These organizations also require creative linkageswith and on-going support from women’sorganizations and o<strong>the</strong>r social justice organizations,including trade unions; governments; and<strong>UN</strong> partners, such as <strong>UN</strong>IFEM, <strong>UN</strong>DP and <strong>the</strong>ILO.While most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se priorities have been on<strong>the</strong> international development agenda for sometime, this report highlights two strategic concernsthat do not get sufficient attention.First, poverty and inequality cannot bereduced by expecting economic policies to generateemployment and social policies to compensatethose for whom <strong>the</strong>re are no jobs, oronly bad jobs. Economic growth <strong>of</strong>ten fails togenerate sufficient employment or employmentthat pays enough to live free <strong>of</strong> poverty, whilecompensation through social policies is typicallyinadequate or neglected altoge<strong>the</strong>r.Second, poverty reduction requires a majorreorientation in economic priorities to focus onemployment, not just growth and inflation. To beeffective, strategies to reduce poverty and promoteequality should be employment-orientedand worker-centred.In recent years, many observers have calledfor people-centred or gender-responsiveapproaches to poverty reduction. What is calledfor here is an approach that focuses on <strong>the</strong>needs and constraints <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> working poor, especiallywomen, as workers, not only as citizens, asmembers <strong>of</strong> a vulnerable group or as members <strong>of</strong>poor households. A worker focus will providecoherence and relevance to poverty reductionstrategies because most poor people work,because earnings represent <strong>the</strong> main source <strong>of</strong>income in poor households, and because work-

ing conditions affect all dimensions <strong>of</strong> poverty(i.e., income, human development, human rightsand social inclusion).The Way ForwardCombating poverty and achieving gender equalityrequire a major reorientation <strong>of</strong> economic anddevelopment planning. Governments and <strong>the</strong>irinternational development partners need to recognizethat that <strong>the</strong>re are no short-cuts in thiseffort: economic growth, even if supplementedby social policies, too <strong>of</strong>ten fails to stimulate <strong>the</strong>kind <strong>of</strong> secure, protected employment needed toenable <strong>the</strong> working poor to earn an income sufficientto pull <strong>the</strong>mselves out <strong>of</strong> poverty. <strong>Women</strong>’sentry into <strong>the</strong> paid labour force on <strong>the</strong> terms andunder <strong>the</strong> conditions identified in this report hasnot resulted in <strong>the</strong> economic security needed toimprove gender equalityThe creation <strong>of</strong> new and better employmentopportunities – especially for <strong>the</strong> working poor –must be an urgent priority for all economic policies.The experience <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> last two decades,especially in developing countries, has shownthat policies targeted narrowly towards containinginflation and ensuring price stability, such asthose frequently promoted by <strong>the</strong> IMF and <strong>the</strong>World Bank, <strong>of</strong>ten create an economic environmentthat is hostile to an expansion <strong>of</strong> more andbetter employment opportunities. Successfulefforts to combat poverty require a radical changein <strong>the</strong> economic policies promoted by <strong>the</strong>se institutionsand adopted by many governments.In <strong>the</strong> short term, however, <strong>the</strong>re are thingsthat can be done short <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> complete overhaul<strong>of</strong> development thinking and planning called for.What is needed is a critical mass <strong>of</strong> institutionsand individuals at all levels to work toge<strong>the</strong>r on aset <strong>of</strong> core priorities. These include:Core Priority # 1 - To promote decent employmentfor both women and men as a key pathway toreducing poverty and gender inequality. A concertedeffort is needed to ensure that decent employmentopportunities are viewed as a target ra<strong>the</strong>r than anoutcome <strong>of</strong> economic policies, including nationalMDG strategies and Poverty Reduction Strategies.Core Priority # 2 - To increase visibility <strong>of</strong>informal women workers in national labour forcestatistics and in national gender and povertyassessments, using <strong>the</strong> employment by type andearnings indicators recommended for MillenniumDevelopment Goal 3.Core Priority # 3 - To promote a morefavourable policy environment for <strong>the</strong> working poor,especially women, in <strong>the</strong> informal economy throughimproved analysis, broad awareness building andparticipatory policy dialogues.Core Priority # 4 - To support and streng<strong>the</strong>norganizations representing women informalworkers and help <strong>the</strong>m gain effective voice in relevantpolicy-making processes and institutions.This report shows that workers in <strong>the</strong> informaleconomy, especially women, have loweraverage earnings and a higher poverty risk thanworkers in <strong>the</strong> formal economy. The meagre benefitsand high costs <strong>of</strong> informal employmentmean that most informal workers are not able towork <strong>the</strong>ir way out <strong>of</strong> poverty. In <strong>the</strong> short term,<strong>the</strong>y are <strong>of</strong>ten forced to ‘over-work’ to cover<strong>the</strong>se costs and still somehow make ends meet.In <strong>the</strong> long term, <strong>the</strong> cumulative toll <strong>of</strong> beingover-worked, under-compensated and underprotectedon informal workers, <strong>the</strong>ir families, and<strong>the</strong>ir societies undermines human capital anddepletes physical capital.In conclusion, <strong>the</strong> working poor in <strong>the</strong> informaleconomy are relegated to low paid, insecureforms <strong>of</strong> employment that make it impossible toearn sufficient income to move out <strong>of</strong> poverty.So long as <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> women workers areinformally employed, gender equality will alsoremain an elusive goal. <strong>Progress</strong> on both <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se goals <strong>the</strong>refore demands that all thosecommitted to achieving <strong>the</strong> MDGs, including <strong>the</strong><strong>UN</strong> system, governments and <strong>the</strong> internationaltrade and finance institutions, make decentemployment a priority – and that corporationsbe made more socially responsible. Informalworkers, both women and men, organized inunions, cooperatives or grassroots organizations,are ready to partner with <strong>the</strong>m in this vitalendeavour.Overview13

1CHAPTEREmployment and PovertyReductionWoman selling ackeein a street market,Kingston, Jamaica.Photo: Christopher P.Baker/Lonely Planet

“Poverty means working for more than 18 hours a day, but stillnot earning enough to feed myself, my husband, and my two children.”<strong>Work</strong>ing poor woman, Cambodia (cited in Narayan 2000)At <strong>the</strong> Millennium Summit in September2000, <strong>the</strong> largest-ever assembly <strong>of</strong> nationalleaders reaffirmed that poverty andgender inequality are among <strong>the</strong> mostpersistent and pervasive global problems.After a decade or more <strong>of</strong> relative neglect, povertyhad pushed its way back to <strong>the</strong> top <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> globalagenda. After three decades <strong>of</strong> women’s advocacy,gender equality had moved from <strong>the</strong> margins to <strong>the</strong>centre <strong>of</strong> that agenda (<strong>UN</strong>IFEM 2002b). Moreover,<strong>the</strong> Millennium Declaration, adopted by <strong>the</strong> world’sleaders, recognized that <strong>the</strong> two are linked, noting<strong>the</strong> centrality <strong>of</strong> gender equality to efforts to combatpoverty and hunger and to stimulate truly sustainabledevelopment (<strong>UN</strong> 2000). In so doing, <strong>the</strong>Declaration honoured <strong>the</strong> vision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Platform forAction adopted at <strong>the</strong> 1995 Fourth WorldConference on <strong>Women</strong> in Beijing.<strong>Progress</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World’s <strong>Women</strong> <strong>2005</strong> marks<strong>the</strong> fifth anniversary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UN</strong> MillenniumDeclaration and <strong>the</strong> tenth anniversary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> BeijingPlatform for Action. It focuses on a key pillar <strong>of</strong> both<strong>the</strong> Millennium Declaration and <strong>the</strong> Beijing Platform:streng<strong>the</strong>ning women’s economic security andrights. Within that framework, it looks particularly atemployment, especially informal employment, and<strong>the</strong> potential it has to ei<strong>the</strong>r perpetuate or reduceboth poverty and gender inequality. It provides <strong>the</strong>latest data on <strong>the</strong> size and composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> informaleconomy in different regions and compares <strong>of</strong>ficialnational data on average earnings and povertyrisk across different segments <strong>of</strong> both <strong>the</strong> informaland formal workforces in several countries. It looksat <strong>the</strong> costs and benefits <strong>of</strong> informal work and providesa strategic framework for promoting decentwork for women informal workers.Poverty and Gender Inequality in <strong>the</strong>21st CenturyThe persistence <strong>of</strong> poverty worldwide is a majorchallenge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 21 st century. Five years after <strong>the</strong>Millennium Summit, more than 1 billion peoplestruggle to survive on less than $1 a day (<strong>UN</strong> <strong>2005</strong>).Of <strong>the</strong>se, roughly half – 550 million – are working(ILO 2003a). By definition, 550 million people cannotwork <strong>the</strong>ir way out <strong>of</strong> extreme poverty. They simplydo not earn enough to feed <strong>the</strong>mselves and <strong>the</strong>irfamilies, much less to deal with <strong>the</strong> economic risksand uncertainty <strong>the</strong>y face.The <strong>2005</strong> Millennium Development GoalsReport shows that progress is possible. The number<strong>of</strong> people living on less than $1 a day fell by nearly250 million from 1990 to 2001. But <strong>the</strong> decline inoverall poverty masks significant differencesbetween regions: Asia showed <strong>the</strong> greatest declinein extreme poverty, followed by a much slowerdecline in Latin America; while Sub-Saharan Africaexperienced an increase in extreme poverty. Chinaand India account for much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poverty decline inAsia (<strong>UN</strong> <strong>2005</strong>). But in India, deep pockets <strong>of</strong> povertypersist and regional disparities have increased(Deaton and Dreze 2002). And in China, income disparitiesbetween rural and urban areas and betweendifferent regions remain large, as reflected in <strong>the</strong>large numbers <strong>of</strong> rural to urban migrants from <strong>the</strong>late 1980s to <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1990s. 1For poor people who are working, how <strong>the</strong>ymake a living – <strong>the</strong>ir sources <strong>of</strong> income or livelihood– is a major preoccupation. Poverty, however, is multidimensional.Today, <strong>the</strong>re are several broadapproaches to understanding and measuring povertyand well-being, including:■ income and basic needs: focusing on <strong>the</strong>income, expenditures, and basic needs <strong>of</strong> poorhouseholds;■ human development: focusing on health, education,longevity and o<strong>the</strong>r human capabilities andon <strong>the</strong> choices or freedom <strong>of</strong> poor people;■ human rights: focusing on <strong>the</strong> civic, political,economic and social rights <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poor; and■ social inclusion: focusing on <strong>the</strong> access <strong>of</strong> poorpeople to what <strong>the</strong>y are entitled to as citizens andon giving <strong>the</strong>m representative ‘voice’ in <strong>the</strong> institutionsand processes that affect <strong>the</strong>ir lives and work.The lives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> working poor in <strong>the</strong> informaleconomy come up short along each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se dimensions<strong>of</strong> poverty and well-being.What about gender equality? While <strong>the</strong> understanding<strong>of</strong> this concept may vary, depending onCHAPTER 1 | Employment and Poverty151 The numbers <strong>of</strong> rural to urban migrants are estimated to have peaked at around 75 million in <strong>the</strong> period from <strong>the</strong> late 1980s to <strong>the</strong> mid-1990s and to have tapered to around 70 million by <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> 2000 (Chen and Ravallion 2004, Weiping 2001). The decline in <strong>the</strong> poverty ratein China appears to have flattened after 1996 despite per capita GDP growth rates around 7% through 2001 (Chen and Ravallion 2004).

Vendors in a street market, Hanoi, Viet Nam. Photo: Martha Chen16<strong>Progress</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World’s <strong>Women</strong> <strong>2005</strong><strong>the</strong> lived experiences <strong>of</strong> different groups in differentcountries, <strong>the</strong> Millennium Declaration providesa consensus understanding according to whichgender equality means “equality at all levels <strong>of</strong>education and in all areas <strong>of</strong> work, equal controlover resources and equal representation in publicand political life” (<strong>UN</strong> <strong>2005</strong>). 2 By <strong>2005</strong>, in mostregions, <strong>the</strong> gender gap in primary and (to a lesserextent) secondary education had narrowed;women’s representation in national parliamentshad increased; and women had become a growingpresence in <strong>the</strong> labour market. But higher educationremains an elusive goal for girls in manycountries; women still occupy only 16 per cent <strong>of</strong>parliamentary seats worldwide; and <strong>the</strong>y remain asmall minority in salaried jobs in many regions,while <strong>the</strong>y are overrepresented in <strong>the</strong> informaleconomy (ibid.).In addition, some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> measures <strong>of</strong> progressmay have contradictory outcomes for women. Forexample, women’s share <strong>of</strong> non-agricultural wageemployment, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> four indicators underMillennium Development Goal 3, simply showswhe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> share <strong>of</strong> women in such employmenthas increased or decreased; it does not show <strong>the</strong>conditions under which women work or <strong>the</strong> returnsto <strong>the</strong>ir labour. If women are concentrated in lowpaidand unprotected forms <strong>of</strong> non-agriculturalwage employment, <strong>the</strong>n an increase in <strong>the</strong>ir share <strong>of</strong>such employment does not represent an increase ingender equality (see Chapter 3).Employment in <strong>the</strong> 21st CenturyFor much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 20 th century, economic development– at least in Europe and North America –was predicated on <strong>the</strong> model <strong>of</strong> state-basedsocial and economic security as embodied in <strong>the</strong>welfare state, <strong>the</strong> goal <strong>of</strong> full employment andrelated protective regulations and institutions (ILO2004a). However, by <strong>the</strong> 1980s, a new economicmodel began to take shape: one that is centredon fiscal austerity, free markets and <strong>the</strong> ‘rollback’<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> state. Under this model, <strong>the</strong>re are threemain policy prescriptions for economic developmentand growth: market liberalization, deregulationand privatization. While inflation has beenbrought under control in many countries, financialcrises and economic volatility have become morefrequent and income inequalities have widened(<strong>UN</strong>RISD <strong>2005</strong>; ILO 2004a). More critically, <strong>the</strong>central goal <strong>of</strong> this new model – long-run, sustainablegrowth as <strong>the</strong> solution to uneven development– has not been achieved in many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>countries that have embraced it.The consequences <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se policies in terms <strong>of</strong>poverty or gender inequality are rarely discussed inmainstream economic debates, nor are <strong>the</strong> cuts indomestic social spending and legal protection thatare <strong>of</strong>ten part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orthodox policy mix. At best,<strong>the</strong>re is a call for <strong>the</strong>se policies to be complementedby investments in public goods such as education,health, infrastructure and by social policies to compensate<strong>the</strong> ‘losers’ in <strong>the</strong> processes <strong>of</strong> liberaliza-2 As <strong>UN</strong>IFEM and o<strong>the</strong>rs have pointed out, gender equality also entails <strong>the</strong> transformation <strong>of</strong> gender hierarchies and social andeconomic structures that perpetuate inequality; and ensuring women’s personal security and right to live free <strong>of</strong> povertyand violence (see Heyzer 2001a,b; <strong>UN</strong>DP <strong>2005</strong>).

tion, deregulation and privatization. But <strong>the</strong> fundamentals<strong>of</strong> free-market reforms, including <strong>the</strong>expectation that employment and standards <strong>of</strong> livingwill increase along with economic growth andthat market interventions create distortions that mayupset this relationship, remain largely unchallenged.In fact, <strong>the</strong>se economic reforms, unless properlymanaged, can have contradictory outcomes interms <strong>of</strong> poverty and gender inequality. They can<strong>of</strong>fer many opportunities for poverty reduction providedthat steps are taken to enable people who arepoor to gain ra<strong>the</strong>r than lose from <strong>the</strong> changesinvolved. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, <strong>the</strong>y can leave poorercountries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world – and <strong>the</strong> poorer section <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> population within <strong>the</strong>m – worse <strong>of</strong>f than before.The consequences for those who are poor, especiallywomen, depend on who <strong>the</strong>y are, where <strong>the</strong>ylive, whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y are allowed to earn a livelihoodand what <strong>the</strong>y do to earn it.Without an explicit focus on increasing <strong>the</strong>demand for labour, economic growth will not generateas many jobs as needed, resulting in joblessgrowth. Moreover, without an explicit focus on <strong>the</strong>quality <strong>of</strong> employment, <strong>the</strong> jobs that are created maynot be regulated or protected. Recent economicgrowth has been associated with flexible labourmarkets, outsourcing <strong>of</strong> production and <strong>the</strong> growth<strong>of</strong> temporary and part-time jobs.Countries around <strong>the</strong> world have adoptedlabour laws that tolerate and even promote labourmarket flexibility without much concern for <strong>the</strong>social outcomes <strong>of</strong> such policies in terms <strong>of</strong> povertyand gender inequality, and <strong>the</strong>refore without puttingin place safety nets or unemployment compensationschemes (Benería and Floro 2004). During <strong>the</strong>1990s in Ecuador, for example, as part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>reforms initiated by <strong>the</strong> International Monetary Fund(IMF) and <strong>the</strong> World Bank, measures to increaselabour flexibility were incorporated in <strong>the</strong> labourcode, including: (a) <strong>the</strong> replacement <strong>of</strong> indefinitelabour contracts with fixed-term contracts and <strong>the</strong>use <strong>of</strong> temporary, part-time, seasonal and hourlycontracts in hiring; and (b) restrictions on <strong>the</strong> right tostrike, collective bargaining, and <strong>the</strong> organization <strong>of</strong>workers (CELA-PUCE 2002, cited in Floro andHoppe <strong>2005</strong>). As ano<strong>the</strong>r case in point, <strong>the</strong>Government <strong>of</strong> Honduras is currently considering anew ‘temporary work law’ that would permit garmentfactories to hire up to 30 per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir workersunder temporary, instead <strong>of</strong> permanent, contracts.If this law is passed, those who are shifted totemporary employment would lose <strong>the</strong> benefits <strong>of</strong>paid leave, social security and an annual bonus andsee <strong>the</strong>ir earnings decline (Oxfam International2004; Kidder and Raworth 2004). 3In today’s global world, as economic insecurityand volatility are on <strong>the</strong> rise, <strong>the</strong> associated risks areincreasingly being borne by ordinary workers andworking communities ra<strong>the</strong>r than by large corporationsand <strong>the</strong>ir owners (ILO 2004a). 4 This is due notonly to labour market deregulation but also to <strong>the</strong>global system <strong>of</strong> production that involves dispersedproduction coordinated through networks or chains<strong>of</strong> firms. In <strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong> global competition, privatecorporations are hiring workers under insecureemployment contracts <strong>of</strong> various kinds or o<strong>the</strong>rwisepassing economic risk onto o<strong>the</strong>rs down <strong>the</strong> globalproduction chain. Authority and power tend to getconcentrated in <strong>the</strong> top links <strong>of</strong> value chains or diffusedacross firms in complex networks, making itdifficult for micro-entrepreneurs to gain access andcompete and for wage workers to bargain for betterwages and working conditions (see Chapter 4).Lead corporations <strong>of</strong>ten do not know how <strong>the</strong>ir subsidiariesor suppliers hire workers. This means thatmany <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> newly employed in developing countriesand a growing share <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> workforce in developedcountries are not covered by employmentbasedsocial and legal protections, thus joining <strong>the</strong>ranks <strong>of</strong> those who have always been informallyemployed in developing countries.From <strong>the</strong> 1960s through <strong>the</strong> early 1980s, it waswidely assumed that in developing countries, wi<strong>the</strong>conomic growth, workers in <strong>the</strong> informal economywould be absorbed into <strong>the</strong> modern industrial economy,as had happened historically in <strong>the</strong> industrializedcountries. However, over <strong>the</strong> past two decades,<strong>the</strong> informal economy has persisted and grown bothin developing and developed countries, appearing innew places and guises.This has led to a renewal <strong>of</strong> interest in <strong>the</strong>informal economy accompanied by considerablerethinking on its size, composition and significance.A group <strong>of</strong> scholars and activists, includingSEWA, HomeNet and o<strong>the</strong>r members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Women</strong> in Informal Employment: Globalizing andOrganizing (WIEGO) network, have worked with<strong>the</strong> ILO to broaden <strong>the</strong> concept and definition <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> informal economy to include all forms <strong>of</strong> informalwage employment and informal self-employment(see Chapter 3). They have also been part <strong>of</strong>a broader effort with <strong>the</strong> ILO, <strong>UN</strong>IFEM, and <strong>UN</strong>DPto work with both governments and civil societypartners to advocate for recognition and protectionfor people working in <strong>the</strong> informal economy.In developing countries, informal employmentas defined above represents one half to three quarters<strong>of</strong> non-agricultural employment (ILO 2002b).The share <strong>of</strong> informal employment in total employmentis higher still, given that most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> agriculturalworkforce is informal: notably, small farmers andcasual day labourers or seasonal workers. Even onplantations and large commercial farms, only part<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> workforce is hired under formal permanentCHAPTER 1 | Employment and Poverty173 As <strong>of</strong> April <strong>2005</strong>, <strong>the</strong> law had not been passed in Honduras (Lynda Yanz, Maquila Solidarity Network, personal communication).4 ILO 2004a presents summary findings from People’s Security Surveys in 15 countries and Enterprise Labour Flexibility andSecurity Surveys in 11 countries.