Book sample (PDF) - Heyday

Book sample (PDF) - Heyday

Book sample (PDF) - Heyday

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

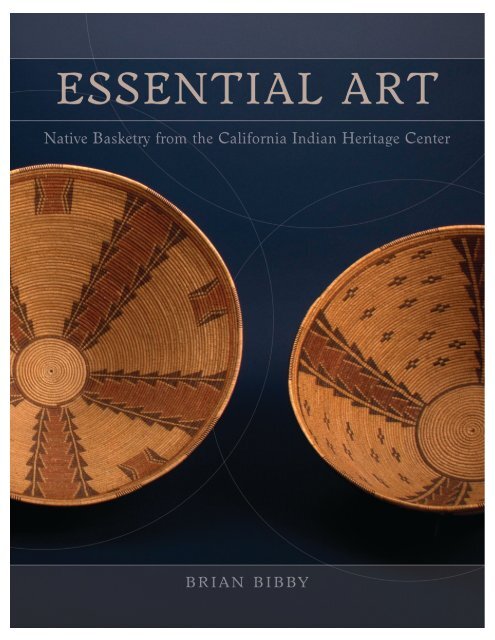

INTRODUCTION Basketry in Native LifeWorld-Class Art Born of NecessityCalifornia Indian basketry is one of the great textile traditions of theworld. In a region encompassing remarkably diverse natural environments,nearly every Native community excelled at basketry, creatinga marvelous palette of distinctive, regional weaving traditions—from therainy redwood forests of the North Coast to the arid expanse of Death Valley.Characterized by their structural integrity and technique, variety of form, andvisually stimulating designs, these containers are iconic of California Indiancultures.Baskets pervaded every aspect of Native life. Infants were cradled in basketswithin the first minutes of life, while a fine basket might cover one’s face inthe hour of death. Admired for their aesthetic merits, baskets were nonethelessborn of necessity, rooted in a way of life, used to collect, transport, process,and store diverse food resources. Strong, durable, versatile, lightweight, andoften watertight, Native baskets were perfected to suit local food-collectingeconomies.For centuries, basketry was a community-based tradition. It was not ahobby or an isolated art venture. All the women in a community were responsiblefor the production of baskets. Elder female relatives passed skills andstandards on to younger generations. The role of basketry was just one ofmany aspects of Native life that changed with the arrival of Euro-Americans.By the close of the nineteenth century, the use of baskets in everyday life beganto decline; instead, California Indian baskets had become one of the mostsought-after art forms in America, at the forefront of a burgeoning market xv

xvi Introductionsfor hand-crafted items. The “art basket” was primarily made for export tonon-Natives, part of a new economic strategy. Individual weavers respondedto demand with innovations, often modifying traditional forms, expandingthe use of decorative motifs, and refining traditional techniques to superfinelevels. This was partly in response to the tastes of buyers, but perhaps weaverswere also exploring the limits of their abilities and imaginations. Some becamefamous as master artists, such as the Washoe weaver Louisa Keyser (Datsolalee),the Wiyot weaver Elizabeth Hickox, and the Pomo weavers JoseppaDick, Mary Benson, and Sarah Knight.Diversity and abundance are the hallmarks of Native California, whetherin the context of language—California was one of the three most linguisticallydiverse regions on Earth—or ecological diversity. Not surprisingly, oneof the great attractions of California Indian basketry is its seemingly endlessvariety. This variety, along with the astounding quality and beauty of Nativebaskets made throughout California, reveals not only masterful techniquebut botanical expertise, distinctive cultural traditions, and personal artisticvision. They are vessels of delight, American masterpieces.The Native American ethnographic collections at the California Indian HeritageCenter, once included in the collections of the California State IndianMuseum and still under the umbrella of California State Parks, include morethan thirty-two hundred baskets from Native California.1 Marvelous andimportant examples of basketry from across the expanse of North America.are included as well. Beyond sheer quantity, perhaps the greatest value of theCalifornia collection is in its completeness. Nearly every genre and style ofbasket is represented. The weaving traditions of communities throughout theregion are here, from the days when California was a Spanish colony and apart of Mexico to the mid-1950s. Baskets from small tribal communities whoseworks have rarely been collected are here, and in some instances, the completespectrum of a community’s basketry history and tradition is represented.The collection ranges from exquisite art pieces by some of Native California’smost gifted master artists to heavily worn baskets documenting everyday life.It is much like a great library. A cause for outright celebration is the fact thattwenty-first century weavers are still making these ancient baskets. 2 KathyWallace (Yurok/Karuk/member of the Hoopa Tribe) describes its significancefor basket weavers:A basket collection the size and depth of this one is a majorresource for California Indian basket weavers. Whether one islearning to weave or expanding one’s knowledge, a weaver is greatlyhelped by seeing and handling the baskets of his/her ancestors.To have access to a collection of baskets is ideal. To be able to lookclosely, feel, turn the basket over and around, and examine it insideand out can be invaluable.

TolowaYurokChilulaWhilkutWiyotBear RiverMattoleLassikSinkyoneCahtoCoastMiwokKarukHupaTsnungweChimarikoNongatlWintuWailakiBay MiwukShastaNomlakiYanaMadesiPlainsMiwukModocAstarawiAchumawiIlmawiAtsugewiYukiKonkowNorthernPomo PatwinCentral WintunSouthern Lake NisenanMiwukWappoHammawiAtwamsiniAporigeMaiduSierraMiwukHewisedawiKosalektawiPit RiverTribesNorthernPaiuteWashoeMono LakePaiute Tribes of CaliforniaEsselenOhloneYokutsSalinanChukchansiTachiKechayiChoinumniWukchumneYowlumniOwens ValleyPaiuteWesternMonoYaudanchiPanamint/TimbishaShoshoneTubatulabalKawaiisuSouthernPaiuteChumashFernandeño/TataviamKitanemukTongva(Gabrieleno)SerranoCahuillaChemehueviMojaveHalchidhomaAjachmem (Juaneño)LuiseñoCupeñoKumeyaay(Diegueño)Quechan(Yuma) xxiii

Evolving Forms 79Glass BeadsBy the end of the nineteenth century, a multicolored palette of glass beads hadbecome available to weavers. Beads of increasingly smaller size were woven intoever more intricate patterns that often carried the entire design of the basket.Pomo weavers became particularly renowned for their fully beaded baskets. Ason the older beaded baskets, a sewing strand of split sedge root passes throughthe eye of each tiny “seed bead” and secures it to the surface.About the basket on the left, Pomo weaver Susan Billy comments, “This is a morenormal or expected response to weaving, using the glass beads for a two-tone pattern,following traditional light and dark contrast. It is a traditional interpretation, butwith a new medium.”The center basket, most likely woven by a Pomo woman who lived in the SantaRosa vicinity during the early twentieth century, Mary Mora, is highly unusual: boththe outer and interior surfaces are beaded, each surface receiving different patterns. 11Susan Billy comments that “conceiving both the interior and exterior patterns is acomplicated matter. The splicing and adding of weaving material is an extra challengebecause of the beads on both sides of the basket. It’s like she’s painting with beads.The designs stem more from introduced beadwork traditions than Pomo basketry.”Generally, the small, single-rod beaded baskets woven by Pomo and AlexanderValley Wappo weavers do not include woven patterns, relying solely on glass beadsto carry the design. The inclusion of bulrush on the rim of the basket on the right tocoincide with the convergence of the black bead pattern is a nice surprise andexemplifies both the climate of experimentation and the individual spirit of theweaver. As Susan Billy comments, “I like how she terminated the design with stitchesof black bulrush. It ties it all together very nicely.”Pomo beaded basketsCollected by H. H. WelshSonoma County–Mendocino County,c. 1910Left: 51976.d6Center: 51976.d13, by Mary MoraRight: 51976.d21

116 Essential ArtMabel McKay (1907–1993)Mabel McKay, 1973Photograph by Spence BillingtonCourtesy Pacific Western TradersMabel (Boone) McKay, a sickly child, spent most of her childhood with herWintun grandmother, Sarah Taylor, near Rumsey in Yolo County. Althoughshe lived in relatively recent times—born early in the twentieth century—duringher childhood virtually all of her female relatives still wove baskets. Sherecalled watching her grandmother weave but attributed her own knowledgeof weaving to a series of powerful dreams. By the age of twelve, Mabel McKayhad already had a number of spiritual experiences by way of her dreams, whicheventually led her into the life of a traditional healer, or “doctor.” The spirit hadprovided the direction of her life and the inspiration for her basket making.Mabel McKay became well known throughout Northern California forher doctoring, knowledge of Pomo and Wintun traditions, fluency in theWintun language, and impeccable basketry. She demonstrated her basketryskills on numerous occasions at the fledgling State Indian Museum (thenlocated within the State Capitol) during the 1920s and 1930s. The museum’sThe Sacramento Union reported onbasketry demonstrations by MabelMcKay (Katunum Kahum) at the StateIndian Museum. This clipping is datedJanuary 23, 1934.