Treb Allen - Department of Economics

Treb Allen - Department of Economics

Treb Allen - Department of Economics

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

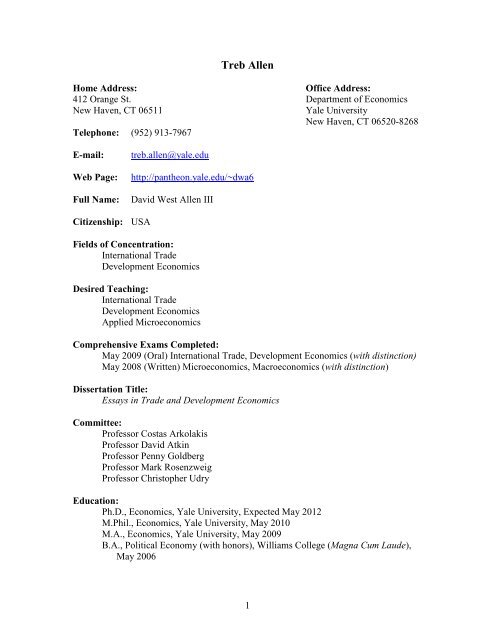

<strong>Treb</strong> <strong>Allen</strong>Home Address:Office Address:412 Orange St. <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Economics</strong>New Haven, CT 06511Yale UniversityNew Haven, CT 06520-8268Telephone: (952) 913-7967E-mail:Web Page:Full Name:treb.allen@yale.eduhttp://pantheon.yale.edu/~dwa6David West <strong>Allen</strong> IIICitizenship: USAFields <strong>of</strong> Concentration:International TradeDevelopment <strong>Economics</strong>Desired Teaching:International TradeDevelopment <strong>Economics</strong>Applied MicroeconomicsComprehensive Exams Completed:May 2009 (Oral) International Trade, Development <strong>Economics</strong> (with distinction)May 2008 (Written) Microeconomics, Macroeconomics (with distinction)Dissertation Title:Essays in Trade and Development <strong>Economics</strong>Committee:Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Costas ArkolakisPr<strong>of</strong>essor David AtkinPr<strong>of</strong>essor Penny GoldbergPr<strong>of</strong>essor Mark RosenzweigPr<strong>of</strong>essor Christopher UdryEducation:Ph.D., <strong>Economics</strong>, Yale University, Expected May 2012M.Phil., <strong>Economics</strong>, Yale University, May 2010M.A., <strong>Economics</strong>, Yale University, May 2009B.A., Political Economy (with honors), Williams College (Magna Cum Laude),May 20061

Fellowships, Honors and Awards:FREIT-EIIT Paper Prize (for “Information Frictions in Trade”), 2011Carl Arvid Anderson Prize Fellowship, 2011Sasakawa Research Grant, 2011Robert Evenson Travel Fellowship, 2011Ryoichi Sasakawa Young Leaders Fellowship, 2010-2011National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, 2007-2010Yale University Economic Growth Center Prize, 2007-2011Yale University Doctoral Fellowship, 2007-2011Phi Beta Kappa, 2006Williams Class <strong>of</strong> 1945 World Fellowship, 2005Teaching Experience:Yale University Teaching FellowInternational Trade, Fall 2010<strong>Economics</strong> Ph.D. “Math Camp,” Summer 2009Behavioral <strong>Economics</strong>, Summer 2009Williams College Teaching AssistantIntroductory Macroeconomics, Spring 2006Global Political Economy, Spring 2006Public Finance, Center for Development <strong>Economics</strong>, Fall 2005Research Experience:Research Assistant, Costas Arkolakis, Yale University, 2009-2011Field Consultant, Innovations for Poverty Action, Mexico, 2008Research Assistant, Justine Hastings, NBER, 2007Research Assistant, Chris Udry, Economic Growth Center, Yale University,2006-2007Research Intern, National Science Foundation Research Experience forUndergraduates, Andrew Young School <strong>of</strong> Policy Studies, 2004Working Papers:“Information Frictions in Trade” (Job Market Paper).“Optimal (Partial) Group Liability in Micr<strong>of</strong>inance Lending.”“The Value <strong>of</strong> Freedom: Fertility Decisions and the Escape from Slavery.”“Inviting Husbands in Women-only Solidarity Groups: Evidence from SouthernMexico” (with Beatriz Armendáriz, Dean Karlan, and Sendhil Mullainathan).2

Research Statement:My research interests span the fields <strong>of</strong> economic development and international trade,with a focus on the intersection <strong>of</strong> the two fields. I am particularly interested in the roleinformation plays in market interactions in developing countries. My research is guidedclosely by economic theory and combines structural analysis with reduced formtechniques.Information Frictions in Trade (Job market paper)The standard assumption in trade models with perfect competition is that arbitrageensures price differences across space arise solely from costs associated with transportinggoods. Recent empirical work, however, suggests that price variation is also affected bythe cost <strong>of</strong> acquiring information about prices elsewhere (“information frictions”).Despite recognizing that information frictions exist, we currently lack a theoreticalunderstanding <strong>of</strong> how they affect trade.In my job market paper, I contribute to the understanding <strong>of</strong> how information frictionsaffect trade in three ways. First, I develop a trade model that explicitly incorporates theprocess producers undergo to acquire information about market conditions elsewhere.Second, using a data set I assemble on regional agricultural trade flows in the Philippines,I show that observed trade patterns and price dispersion cannot be explained by standardtrade models but are consistent with my model incorporating information frictions.Finally, I structurally estimate the model to quantitatively assess the relative importance<strong>of</strong> information frictions and transportation costs.To introduce information frictions, I embed a search process into a many-region trademodel with heterogeneous producers. Producers sequentially search potential destinationsin order to discover market prices and determine where to sell their produce. Because thefixed cost <strong>of</strong> search comprises a smaller proportion <strong>of</strong> total revenue the greater thequantity produced, larger producers will search more intensively and on average sell todestinations with higher prices. I prove the existence and uniqueness <strong>of</strong> the equilibrium <strong>of</strong>the model for a large set <strong>of</strong> preferences and show that it yields a succinct equationgoverning bilateral trade flows.The introduction <strong>of</strong> information frictions yields three important implications for tradeflows and prices. First, price arbitrage opportunities remain in equilibrium. Second,bilateral trade flows differ from the standard gravity equation. Third, information andtransportation frictions affect bilateral trade flows differently, allowing the two tradecosts to be disentangled empirically.In the second part <strong>of</strong> the paper, I empirically evaluate the model using a comprehensivedata set I assemble on the universe <strong>of</strong> domestic shipments <strong>of</strong> agricultural commodities inthe Philippines from 1995-2009. I show that (1) observed patterns <strong>of</strong> trade and prices areinconsistent with the no-arbitrage equilibrium condition <strong>of</strong> standard models; (2) thestandard gravity model exhibits substantial bias in predicting how trade flows respond toidiosyncratic changes in prices; (3) estimated transportation costs are half as large as4

those implied by complete information models and more consistent with observed freightcosts; (4) the vast majority <strong>of</strong> the “gravity” relationship (93 percent) between trade flowsand distance can be attributed to information frictions rather than transportation costs;and (5) counterfactual exercises indicate reductions in information frictions reduceinequality whereas reductions in transportation costs increase inequality.The final part <strong>of</strong> the paper extends the basic model to incorporate intermediary traderswho purchase produce from farmers and then sell the produce to other regions. While thepredictions regarding regional trade flows remain qualitatively unchanged, the extensionallows me to directly examine the search process undertaken by farmers. Using a data set<strong>of</strong> more than two million individual farmer sales, I show that reductions in the cost <strong>of</strong>search owing to the introduction <strong>of</strong> mobile phones induce smaller farmers to search fortraders, as predicted by the model.Optimal (Partial) Group Liability in Micr<strong>of</strong>inance LendingIn this paper, I examine what the optimal joint liability contract is in micr<strong>of</strong>inancelending when lenders do not observe the realized investment returns <strong>of</strong> borrowers. Idevelop a simple model that incorporates partial group liability, where borrowers arepenalized if their group members default but are not held responsible for the entirety <strong>of</strong>the failed loan. The model clearly illustrates the trade-<strong>of</strong>f <strong>of</strong> group liability lending:while higher levels <strong>of</strong> group liability increase the willingness for group members to covereach other's bad returns, when liability becomes too high, borrowers find it optimal tostrategically default. The model implies the existence <strong>of</strong> an optimal partial liability thatmaximizes transfers between group members while avoiding strategic default. Twoextensions <strong>of</strong> the basic model incorporating household structure and group size,respectively, are shown to be able to estimate the prevalence <strong>of</strong> strategic default even inthe presence <strong>of</strong> correlated returns to borrowing. Using administrative data from a largemicr<strong>of</strong>inance institution in Mexico, structural estimates suggest high but variable returnsto borrowing and variation across loan <strong>of</strong>ficers in de facto group liability. Exploiting thisvariation in group liability, I demonstrate an empirical U-shaped relationship betweengroup liability and default rates, as predicted by the model. Structural estimates and out<strong>of</strong>-sampleregressions suggest that moving from full group liability to 75% liability couldsubstantially reduce the incidence <strong>of</strong> default in micr<strong>of</strong>inance lending.The Value <strong>of</strong> Freedom: Fertility Decisions and the Escape from SlaveryIn this paper, I examine the extent to which enslaved mothers in the U.S. antebellumsouth reduced their fertility in hopes <strong>of</strong> facilitating escape. Escaping from slavery withyoung children was extraordinarily difficult, so the possibility <strong>of</strong> escape providedincentives for women to reduce their fertility. A simple model demonstrates that motherswill prefer to have fewer children the greater the distance to freedom, whereas ownersprefer the opposite. Exploiting the Fugitive Slave Law <strong>of</strong> 1850 (which increased thedistance to freedom) and the particularity <strong>of</strong> U.S. geography, a strong negativerelationship between fertility and distance to freedom is demonstrated. This negativecorrelation is stronger on larger plantations, but disappears if the father <strong>of</strong> the child iswhite. The result is robust to controlling for the difficulty <strong>of</strong> the route and a similarcorrelation is not present for white children or for slave children born prior to the5

Fugitive Slave Law. Estimates suggest that fertility fell on average by 8.7 percent foreach additional 100 miles to freedom. Since the probability <strong>of</strong> escape was remote, thislarge reduction in fertility suggests the value <strong>of</strong> freedom is substantial; in particular, Iestimate that the value <strong>of</strong> freedom is at least 27 times greater than the average value <strong>of</strong> achild born in slavery.Ongoing ResearchIn two ongoing projects, I examine the effect <strong>of</strong> economic integration on individualbehavior in developing countries. The first project (with David Atkin and Sabrin Beg)examines how reductions in trade costs affect the responsiveness <strong>of</strong> local prices toproductivity shocks and how these changes affect risk sharing arrangements. We findevidence that transfers between farmers and non-farmers become more responsive toagricultural productivity shocks as economic integration increases, suggesting thatopenness to trade increases individual’s reliance on risk sharing networks. The secondproject examines the effect <strong>of</strong> reductions in information frictions on farmer-traderbargaining. I find evidence that farmers producing less perishable crops benefiteddisproportionately more from the introduction <strong>of</strong> mobile phones, suggesting that morepatient farmers have greater bargaining power.6