Sleuthing Early Tectonics - Carnegie Institution for Science

Sleuthing Early Tectonics - Carnegie Institution for Science

Sleuthing Early Tectonics - Carnegie Institution for Science

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

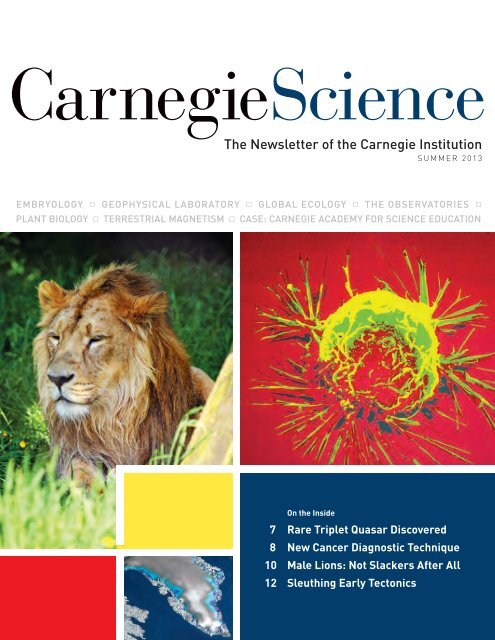

<strong>Carnegie</strong><strong>Science</strong>The Newsletter of the <strong>Carnegie</strong> <strong>Institution</strong>S U M M E R 2 0 1 3EMBRYOLOGY N GEOPHYSICAL LABORATORY N GLOBAL ECOLOGY N THE OBSERVATORIES NPLANT BIOLOGY N TERRESTRIAL MAGNETISM N CASE: CARNEGIE ACADEMY FOR SCIENCE EDUCATIONOn the Inside7 Rare Triplet Quasar Discovered8 New Cancer Diagnostic Technique10 Male Lions: Not Slackers After All12 <strong>Sleuthing</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Tectonics</strong>

L E T T E R F R O M T H EPRESIDENTThank You Mike Gellert!<strong>Carnegie</strong> <strong>Institution</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Science</strong>1530 P Street, NWWashington, D.C.20005-1910202.387.6400www.<strong>Carnegie</strong><strong>Science</strong>.eduPresidentRichard A. MeserveDirector,Department of EmbryologyAllan C. SpradlingDirector,Geophysical LaboratoryRussell HemleyDirector,Department of Global EcologyChristopher FieldDirector,The ObservatoriesCraw<strong>for</strong>d H. Greenewalt ChairWendy L. FreedmanDirector,Department of Plant BiologyWolf FrommerDirector,Department of Terrestrial MagnetismLinda Elkins-TantonDirector,Administration and FinanceCynthia AllenChief Advancement OfficerRick ShermanChief In<strong>for</strong>mation OfficerGotthard Sághi-SzabóDirector,External AffairsSusanne GarveyEditorTina McDowellMike Gellert has served as the chairman of the <strong>Carnegie</strong> board <strong>for</strong> the last10 years and as a board member <strong>for</strong> 18. At our recent board meeting, he turned overthe helm to our new cochairs, Suzanne Nora Johnson and Steve Fodor. I write here toacknowledge that we are deeply appreciative of Mike and all he has done <strong>for</strong> the <strong>Carnegie</strong><strong>Institution</strong>. <strong>Carnegie</strong> owes much of its current vitality to his decade of leadership.Mike became chairman at the same time that I became president, and I havegreatly benefitted from his counsel and wisdom. Moreover, the entire institution hasadvanced as a result of his philanthropy and guidance. He has helped all of ourscience and educational programs, and he has been pivotal in the resolution of amyriad of institutional issues that have arisen over the past decade. <strong>Carnegie</strong> hasprofited from the many insights Mike has offered as a member of various boardcommittees and as chairman.Mike demonstrates his commitment by his actions. He is among the first to makea pledge and the first to fulfill it. Only four others have surpassed him in giving overour entire history. Moreover, Mike has also actively encouraged philanthropy by others.Over the years, he has hosted numerous events and has traveled countless miles tohelp broaden the circle of <strong>Carnegie</strong> friends.In addition to his exemplary philanthropy, Mike has engaged personally in thepursuit of several noteworthy projects. He was deeply involved with establishing theDepartment of Global Ecology, our newest department. With only five senior staff,Global Ecology has made revolutionary advances in studying ecosystems using the<strong>Carnegie</strong> Airborne Observatory (page 10-11), understanding ocean acidification,unraveling the causes of aquatic algal blooms, exploring the carbon and nitrogencycles, and much more. The accomplishments of the department are nothing short ofastonishing and amply demonstrate Mike’s wisdom in advancing a department toconfront vital environmental challenges.During Mike’s term, we were also able to complete a new building <strong>for</strong> theDepartment of Embryology on The Johns Hopkins University Homewood campus.It was essential to upgrade the facility and to provide cutting-edge microscopy andgenomics facilities to remain at the <strong>for</strong>efront of cellular, developmental, and geneticsbiology. The facility is a model <strong>for</strong> others. Mike understands the necessity of highqualityinfrastructure in the pursuit of significant scientific advances.Mike is also committed to long-term projects, one of which is the Giant MagellanTelescope (GMT). In 2003, our astronomers advanced the dream of building atelescope that would dwarf anything previously built. Mike realized that thecommitment would take many years to fulfill, and if we did not get started we woulddepart from our century-long legacy of pioneering telescope and instrumentationdevelopment. Like Andrew <strong>Carnegie</strong>, Mike knew that success would be measuredlong after he left the chairmanship of the <strong>Carnegie</strong> board. The GMT will exploresome of the most tantalizing scientific questions that now confound us—the possibleexistence of life on other planets, the nature of dark energy and dark matter, and thestructure of the universe.We are indebted to Mike <strong>for</strong> his extraordinary, unselfish, and generous support.From all of us at <strong>Carnegie</strong>, thank you Mike!Richard A. Meserve, President<strong>Science</strong> WriterNatasha Metzler

Images courtesy Gediyon KifleTrustee News<strong>Carnegie</strong> <strong>Science</strong> | Summer 2013 3Left: <strong>Carnegie</strong> president Richard Meserve(left) unveils the plaque naming the MichaelE. Gellert Rotunda.Below: Trustees and guests applaud MikeGellert’s (sitting) service to <strong>Carnegie</strong> aschairman of the board over the last decade.Bottom: The Gellert family gathers in therotunda that now bears Michael Gellert’sname. From left to right: daughter CatherineGellert, brother Martin Gellert, Martin’s wifeJacqueline Michaud, wife Mary Gellert,Michael Gellert, daughter-in-law SamanthaGellert, and son John Gellert.The board of trustees held their 138th meeting at theWashington, D.C., administration building on May 2nd and 3rd. MichaelGellert, chairman of the board <strong>for</strong> the last ten years, stepped down as chair.He remains an active member of the board and is succeeded by cochairsSuzanne Nora Johnson and Steve Fodor, who will share duties.The Employee Affairs, Finance, and Development committees met onMay 2nd, followed by the first session of the board. That evening trustees and guests attendeda dinner in honor of Michael Gellert’s service. During the dinner PresidentRichard Meserve announced that the administration building’s stunning rotunda wouldbe named the Michael E. Gellert Rotunda.Norman Augustine was the evening’s speaker. He is the retired chairman and chief executiveofficer of Lockheed Martin Corporation and a longtime proponent <strong>for</strong> ensuringthat science and engineering remains a national priority. He chaired the NationalAcademy of <strong>Science</strong>s commission that conducted a congressionally requested study thatbecame the landmark report Rising Above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and EmployingAmerica <strong>for</strong> a Brighter Economic Future released in 2005.Augustine talked about the enormous impact of globalization and in<strong>for</strong>mationtechnology on societies. “Distance is dead,” he said. “America now has to compete <strong>for</strong> jobswith people across the planet.” He then described the challenges the U.S. faces in thisenvironment, stressing that innovation—particularly through research and development—iskey to successful competition. Augustine talked about the reasons <strong>for</strong> therecent decline the U.S. has witnessed in science and technology education and howthe U.S. now stacks up against the world, and he suggested some possible ways tochange course.The evening concluded with music by pianist and composer Hayk Arsenyan. The nextday the Audit committee and second session of the board met.Kathi Bump (left) with Wolf FrommerSteve ColeyServing <strong>Science</strong><strong>Carnegie</strong> president Richard Meserve presentedtwo Service to <strong>Science</strong> Awards <strong>for</strong> 2012 be<strong>for</strong>e the<strong>Carnegie</strong> Evening lecture on May 1. The award was createdto recognize “outstanding and/or unique contributionsto science by employees who work in <strong>Carnegie</strong>administration, support, and technical positions.”The first recipient of the 2012 award was KathiBump. Kathi started with the Department of Plantcontinued on pg 4

4<strong>Carnegie</strong> <strong>Science</strong> | Summer 2013continued from pg 3Biology in 1995 as an administrativeassistant. Sheheld various positions at thedepartment until 2006,when she was named thebusiness manager of thePlant Biology and GlobalEcology departments thatshare space on the Stan<strong>for</strong>dUniversity campus. Kathi’slevel of dedication is legendary.She handles issuesranging from accounting,inventory, facilities, and thecare of students and visitorsto the proper functioning ofthe soda machine.The second 2012 recipientwas Steve Coley. Steve joinedthe Geophysical Laboratoryas an instrument maker in1983. He has provided essentialsupport in developingand maintaining complexand highly specialized equipmentat the GeophysicalLaboratory. The instrumentsand equipment that Stevedeveloped have been essentialto the cutting-edge researchand groundbreakingdiscoveries of the scientificstaff at the Geophysical Lab.Due in large part to Steve’sabilities, the facilities of theGeophysical Laboratory areexceptional among Earthand materials science laboratoriesaround the world.The panel that reviewedthe nominations and selectedthe award recipientswere Alan Dressler, staff scientistat the Observatories;Steve Farber, staff scientist atthe Department of Embryology;and Cady Canapp,manager of human resources.Greg Asner compared his work in the GlobalEcology department to giving an ecosystem’slandscape an MRI—using technology to determineits construction and components. Asner discussedhis research in a talk titled “Exploring andManaging the Earth from the Sky” at the May<strong>Carnegie</strong> Evening lecture in Washington, D.C.Asner’s revolutionary technology combines laserand spectral instrumentation aboard a fixed-wingaircraft called the <strong>Carnegie</strong> Airborne Observatory(CAO). Researchers use this instrumentation to revealan ecosystem’s chemistry, structure, biomass,and biodiversity and create stunning 3-D maps.The technology allows surveys over extensive areasin a way not possible be<strong>for</strong>e.“We had limited types of in<strong>for</strong>mation aboutecosystems; the <strong>Carnegie</strong> Airborne Observatory[is] designed to overcome that,” Asner told thegroup. By using CAO’s laser and spectral technology,“we can look at something from afar andunderstand, <strong>for</strong> example, its carbon content [and]its … nutrient content.”Most of Asner’s talk focused on his work in theAmazon, which he said is “where my science heartlies.” The region is thought to contain about halfof all species on Earth and at least 100-billion tonsof carbon. The team has completed maps of theentire carbon stocks of Peru, Colombia, andPanama. Activities are underway to map <strong>for</strong> thefirst time the biological diversity of the westernAmazon region—a global hotspot <strong>for</strong> species diversity.Global Ecology’sGreg Asner was thisyear’s <strong>Carnegie</strong>Evening speaker.<strong>Carnegie</strong> Evening:Asner’s “<strong>Science</strong> Heart”Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, land development <strong>for</strong> energy,food, and minerals is dismantling the Amazonbasin. The Amazonian climate has also already begunto change, and species are migrating to survive.“I’m trying to understand the system while it’schanging, and it’s changing in ways that aren’teven the same year to year,” Asner said. “There’s somuch going on and there’s not one answer.”Using the CAO, the team is able to uncover illegalgold mining and palm oil holdings, which arenegatively affecting the Amazon’s ecosystem. Theyare also studying drought patterns in the wake ofthe 2010 Amazon megadrought.Outside of the Amazon, CAO technology is beingused to study wildlife, as well as plant life. Asnerdiscussed exciting research in South Africa’sKruger National Park where their mapping hasshed light on the hunting behavior of male lions,revealing that they aren’t the slackers they’ve longbeen believed to be. Their hunting behavior is justless well-observed, because it takes place in densevegetation “where nobody in their right mind isgoing to go. Believe me I've been there and I wasnotin my right mind,” Asner joked. These resultshelp park officials make decisions on managingthe land to best protect the animals.At the end of the talk, Asner said his goals <strong>for</strong> CAOinclude seeking out ecological frontiers that are stillunknown and unappreciated, to support environmentaldecision making, and to teach and inspire.The Andrew Mellon Foundation, the Avatar Alliance Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Grantham Foundation <strong>for</strong> theProtection of the Environment, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Margaret A. Cargill Foundation, Mary Anne Nyburg Bakerand G. Leonard Baker, Jr., the W. M. Keck Foundation, and William R. Hearst III helped make the <strong>Carnegie</strong> Airborne Observatory possible.

GasAlan BossNew theoretical modeling by <strong>Carnegie</strong>’s Alan Boss providesclues as to how our Solar System’s gas giant planets—Jupiter and Saturn—mighthave <strong>for</strong>med and evolved. The Astrophysical Journal publishedthis work in March.New stars are surrounded by rotating gas disks during the early stagesof their lives. Gas giants are thought to <strong>for</strong>m in the presence of these disks.Observations of young stars that still have these gas disks indicate that sunlikestars undergo periodic episodes—lasting about 100 years—thattransfer mass from the disk onto the young star, increasing its luminosity.Researchers think that these short bursts of mass accretion are drivenby marginal gravitational instability in the gas disk.There are competing theories <strong>for</strong> how gas giant planets <strong>for</strong>m aroundprotosuns. One theory proposes that the planets <strong>for</strong>m from slowlygrowing ice and rock cores, followed by rapid accretion of gas from thesurrounding disk. The other theory proposes that clumps of dense gas<strong>for</strong>m in spiral arms, increasing in mass and density, <strong>for</strong>ming a gas giantplanet in a single step.Boss developed highly detailed 3-D models demonstrating that, regardlessof how gas giants <strong>for</strong>m, they should be able to survive periodicoutbursts of mass transfer from the gas disk onto the young star.One model similar to our Solar System was stable <strong>for</strong> more than 1,000years, while another model containing planets similar to Jupiter andSaturn was stable <strong>for</strong> more than 3,800 years. The models showed thatthese planets were able to avoid being <strong>for</strong>ced to migrate inward and beswallowed by the growing protosun or being tossed completely out ofthe planetary system by close encounters with each other.Scientists have found extrasolar gas giant planets around about 20%of sun-like stars, which is a reassuring outcome.It suggests that our improvedtheoretical understanding ofthe <strong>for</strong>mation and orbitalGiantsHard to Destroyevolution of gas giants ison the right track. Image courtesy NASAAlan Boss is developing theoriesabout how gas giant planets likeJupiter <strong>for</strong>med and survived inthe early days of our SolarSystem. Jupiter and its fourplanet-sized moons, the Galileansatellites, were photographedand assembled into a collage.This research was supported in part by theNASA Origins of Solar Systems Program andcontributed to in part by the NASA AstrobiologyInstitute. The calculations were per<strong>for</strong>med onthe <strong>Carnegie</strong> Alpha Cluster, the purchase ofwhich was partially supported by an NSF MajorResearch Instrumentation grant.

6Image courtesy John Chapman Wikimedia CommonsSpotlight on MolybdeniteMolybdenite (dark) is shown on quartz.Mineral evolution is an approachto understanding Earth’s everchangingnear-surface geochemistry.All chemical elements werepresent at the start of our Solar System,but at first the elements <strong>for</strong>medfew minerals—perhaps no more than500 different ones in the first billion years.As time passed, novel combinations of elementsled to new minerals. A team led by <strong>Carnegie</strong>’sRobert Hazen is conducting research with the mineralmolybdenite, and their work provides importantnew insights about the changing chemistry ofour planet as a result of geological and biologicalprocesses.Molybdenite is the most common ore mineral of the criticalmetallic element molybdenum. Hazen and his team, which includedfellow Geophysical Laboratory scientists Dimitri Sverjenskyand John Armstrong, analyzed 442 molybdenite samples from 135locations with ages ranging from 2.91 billion years old to 6.3 millionyears old. They specifically looked <strong>for</strong> trace contamination ofthe element rhenium in the molybdenite. Rhenium is a trace elementthat is sensitive to oxidation reactions (the transfer of electrons)and it can be used to gauge historical chemical reactions withoxygen from the environment.The team found that concentrations of rhenium increased significantly—bya factor of eight—over the past three billion years. TheyRobert Hazensuggest that this change reflectsthe increasing near-surface oxidationconditions from the Archean eonbeginning more than 2.5 billion years agoto the Phanerozoic eon less than 542 millionyears ago. This oxygen increase was a consequenceof what’s called the Great Oxidation Event, whenthe Earth’s atmospheric oxygen levels skyrocketedas a consequence of the emergence of oxygenproducingphotosynthetic microbes.In addition, the team found that the distributionof molybdenite deposits through time roughly correlates with five periodsof supercontinent <strong>for</strong>mation: the assemblies of Kenorland,Nuna, Rodinia, Pannotia, and Pangaea. This correlation supportsprevious findings from Hazen and his colleagues that mineral <strong>for</strong>mationincreases markedly during episodes of continental convergenceand supercontinent assembly and that a dearth of mineral deposits<strong>for</strong>m during periods of tectonic stability.Overall, this work further demonstrates that a major driving <strong>for</strong>ce<strong>for</strong> mineral evolution is hydrothermal activity associated with collidingcontinents and the increasing oxygen content of the atmosphereRobert Hazen’s research showsthat molybdenite distributioncorrelates with five periods ofsupercontinent <strong>for</strong>mation,including that of Pangaea.Image courtesy USGScaused by the rise of life on Earth. Earth and Planetary <strong>Science</strong> Letterspublished this work in February.The <strong>Carnegie</strong> <strong>Institution</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Science</strong> provided a grant to support the initial development of the Mineral Evolution Database. NASA Astrobiology Institute and the Deep Carbon Observatory, aswell as an NSF-NASA collaborative research grant and DOE, supported this work in part.

<strong>Carnegie</strong> <strong>Science</strong> | Summer 2013 7RareTripletQuasarDiscoveredImage courtesy Emanuele Paolo FarinaThis image shows thequasars—A, B, and C—in the rare triplet system.For only the second time in history, a team of scientists—includingHubble <strong>Carnegie</strong>/Princeton Fellow Michele Fumagalli—has discoveredan extremely rare triple-quasar system. This rare phenomenonwill help scientists understand how cosmic structures assemble in the universeand the basic processes by which massive galaxies <strong>for</strong>m.Quasars are extremely bright and powerful sources of energy that sitin the center of a galaxy; they surround a black hole. In systems with multiplequasars, the quasars are held together by gravity. They are believedto be the product of galaxies colliding.It is very difficult to observe triplet quasar systems because of observationallimits that prevent researchers from differentiating multiplenearby bodies from one another at astronomical distances. Moreover,such phenomena are presumed to be very rare.By combining multiple telescope observations and advanced modeling,the team found the triplet quasar named QQQ J1519+0627. Thelight from these quasars traveled 9 billion light-years to reach Earth,which means the light was emitted when the universe was only a thirdof its current age.Advanced analysis confirmed that what the team found was indeedthree distinct sources of quasar energy and that this phenomenon is extremelyrare.Two members of the triplet are closer to each other than the third.This means that the system could have been <strong>for</strong>med by interaction betweenthe two adjacent quasars but was probably not triggered by interactionwith the more-distant third quasar. Furthermore, researcherssaw no evidence of any ultraluminous infrared galaxies, which is wherequasars are commonly found. As a result, the team proposes that thistriple-quasar system is part of some larger structure that is still undergoing<strong>for</strong>mation. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Societypublished this work in March.Hubble <strong>Carnegie</strong>/Princeton FellowMichele FumagalliThis research was based on observations collected at the La Silla Observatory with the NewTechnology Telescope of the European Southern Observatory and at the Calar Alto Observatorywith the 3.5 m telescope of the Centro Astronómico Hispano-Alemán. Societa Carlo GavazziS.pA., Thales Alenia Space S.pA., Germany’s National Research Center <strong>for</strong> Aeronautics andSpace, and NASA supported this work.Image courtesy Michele Fumagalli

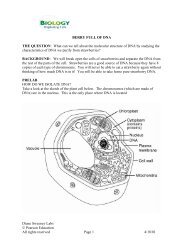

8<strong>Carnegie</strong> <strong>Science</strong> | Summer 2013Frommer’s teamdevised a newmolecular sensor thatdetects levels oflactate in individualcells in real time.Cancer cells, like thisbreast cancer cellshown here, producelactate at a muchhigher rate thannormal cells.Image courtesy Bruce Wetzel and Harry Schaefer, National Cancer Institute, NIHCancer cells break downsugars and produce the metabolicacid lactate at a muchhigher rate than normal cells.This phenomenon provides atelltale sign that cancer is presentand possibly offers an avenue<strong>for</strong> novel cancer therapies.<strong>Carnegie</strong>’s WolfFrommer workedwith a team ofChilean scientists todevise a molecularsensor that detectslevels of lactate inindividual cells inreal time. Prior tothis advance, noother measurementmethod could noninvasivelydetect lactatein real time at the single-celllevel.Over the last decade, theFrommer lab has pioneered theuse of Förster resonance energytransfer (FRET) sensors tomeasure the concentration andflow of sugars in individual cellswith a simple fluorescent colorchange, revolutionizing thestudy of cell metabolism. Usingthe same underlying physicalprinciple and inspired by thesugar sensors, Frommer and theChilean scientists invented aNewCancerDiagnosticTechniquePlant Biology directorWolf Frommernew type of sensorbased on atranscriptionfactor. A moleculethat normallyhelps bacteriaadapt to itsenvironment hasnow been trickedinto measuring lactate <strong>for</strong> researchers.Lactate shuttles between cellsand inside cells as part of thenormal metabolic process. Butlactate is also involved in diseasesthat include inflammation,inadequate oxygen supply tocells, restricted blood supply totissues, and neurological degradation,in addition to cancer.Standard methods to measurelactate are based on reactionsamong enzymes, which requirea large number of cells in complexcell mixtures. This makes itdifficult or even impossible tosee how different types of cellsact when cancerous. The newtechnique lets researchers measurethe metabolism of individualcells, giving them a new window<strong>for</strong> understanding howdifferent cancers operate. Animportant advantage of thistechnique is that it may be usedin high-throughput <strong>for</strong>mat,which is required <strong>for</strong> drug development.The research team used a bacterialtranscription factor—aprotein that binds to specificDNA sequences to control theflow of genetic in<strong>for</strong>mationfrom DNA to mRNA—as ameans to produce and insert thelactate sensor. They turned thesensor on in three cell types:normal brain cells, tumor braincells, and human embryoniccells. The sensor was able toquantify very low concentrationsof lactate, providing anunprecedented sensitivity andrange of detection. The researchersfound that the tumorcells produced lactate three tofive times faster than the nontumorcells. The open accessjournal PLOS ONE publishedthis work in March.The Chilean government, through the National Commission <strong>for</strong> Scientific and TechnologicalResearch’s (CONICYT) Basal Financing Program <strong>for</strong> Scientific and Technological Centers ofExcellence, the Gobierno Regional de Los Ríos, and the National Fund <strong>for</strong> Scientific andTechnological Development (Fondecyt); the National Institutes of Health; and the <strong>Carnegie</strong><strong>Institution</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Science</strong> supported this work.

<strong>Carnegie</strong> <strong>Science</strong> | Summer 2013 9Our galactic neighbor,the Large MagellanicCloud, is about 200,000light-years from Earth.Gas clouds collapseover time to <strong>for</strong>m newstars producingcelestial fireworks.Image courtesy ESA/NASA/HubbleRefining Hubble’s ConstantAn international team of astronomersincluding <strong>Carnegie</strong>’s Ian Thompson hasmanaged to improve the measurement ofthe distance to our nearest neighbor galaxyand, in the process, refine an astronomicalcalculation that helps measure the expansionof the universe.The Hubble constant is a fundamentalquantity that measures the current rate atwhich our universe is expanding. Determiningthe Hubble constant is critical <strong>for</strong>gauging the age and size of our universe.One of the largest uncertainties plaguingpast measurements has involved the distanceto the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC),our nearest neighboring galaxy.The team refined the uncertainty in thedistance to the LMC down to 2.2 percent.This new measurement can be used to decreasethe uncertainty in calculations of theHubble constant to 3 percent, with prospectsof improving this to a 2 percent uncertaintyin a few years.Astronomers survey the scale of the universeby first measuring the distances to closebyobjects and then using observations ofthese objects in more distant galaxies to pindown distances farther and farther out in theuniverse. But this chain is only as accurate asits weakest link. Up to now, finding a precisedistance to the LMC has proved elusive. Becausestars in this galaxy are used to fix the distancescale <strong>for</strong> more remote galaxies, an accuratedistance to it is crucially important.Because the LMC is close and contains asignificant number of different stellar distanceindicators, hundreds of distance measurementsusing it have been recorded overthe years. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately nearly all the determinationshave systemic errors, with eachmethod carrying uncertainties.The international collaboration worked outthe distance to the LMC by observing rareclose pairs of stars, known as eclipsing binaries.These pairs are gravitationally bound toeach other, and once per orbit—as seenIan Thompsonfrom Earth—the totalbrightness from thesystem drops as eachcomponent eclipses itscompanion. By trackingthese changes verycarefully, it is possibleto work outhow big the starsare, how massivethey are, andother in<strong>for</strong>mationabout theirorbits. When thisis combined withcareful measurementsof their apparentbrightness,remarkably accuratedistances can be determined.This method has been used be<strong>for</strong>e in takingmeasurements to the LMC, but with hot stars.As such, certain assumptions had to be madeand the distances were not as accurate as desired.The team’s new work used 16 years’worth of observations to identify a sample ofintermediate mass binary stars with extremelylong orbital periods, perfect <strong>for</strong> measuringprecise and accurate distances.The team observed eight of these binarysystems over eight years. The LMC distancecalculated using these eight binaries is purelyempirical, without relying on modeling ortheoretical predictions. The research was publishedin Nature in March.BASAL-Centro de Astrofisica y Tecnologias Afines (CATA),the Polish Ministry of <strong>Science</strong>, the Foundation <strong>for</strong> Polish<strong>Science</strong> (FOCUS, TEAM), the Polish National <strong>Science</strong>Centre, and the GEMINI-CONICYT fund supported this work.The European Research Council Advanced Grant programgave funding to the OGLE project.

10Male lions such asthis one take downprey using ambushstrategies, ratherthan the cooperativestrategies favored byfemale lions.Male Lions:Not Slackers After AllIImage courtesy Petr Kratochvil, publicdomainpictures.net Image below, courtesy <strong>Carnegie</strong> Airborne Observatoryt has long been believed that male lions are dependenton females when it comes to hunting. Butnew evidence suggests that male lions are, in fact, verysuccessful hunters in their own right. A new reportfrom a team including <strong>Carnegie</strong>’s Scott Loarie andGreg Asner showed that male lions use dense savannavegetation <strong>for</strong> ambush-style hunting in Africa.Female lions have long been observed to rely on cooperativestrategies to hunt their prey. While somestudies demonstrated that male lions are as capable athunting as females, the males are less likely to cooperate,so there were still questions as to how the malesmanage to hunt successfully. The possibility that malelions used vegetation <strong>for</strong> ambushing prey was considered,but it was difficult to study given the logisticsand dangers of making observations of lions indensely vegetated portions of the African savanna.Loarie and Asner combined different types of technologyto change the game. The team swept laserpulses across the African plains to create 3-D mapsof the savanna vegetation. They did this using aLight Detection And Ranging (LiDAR) scannermounted on the fixed-wing <strong>Carnegie</strong> Airborne Observatory(CAO) aircraft. They combined these 3-D habitat maps with GPS data on predator-prey interactionsfrom a pride of seven lions in SouthAfrica’s Kruger National Park to quantify the linesof sight, or “viewsheds,” where lions did their killingin comparison to where they rested.The team found that a preference <strong>for</strong> shadecaused both male and female lions to rest in areaswith dense vegetation and similarly short viewshedsduring the day; the real difference betweenmales and females emerged at night. Female lionsboth rested and hunted under the cover of darknessin areas with large viewsheds. But male lionshunted at night in the dense vegetation—areaswhere prey is highly vulnerable, but which researchersrarely explore. The scientific results showthat hunting success among male lions is linked toambushing prey from behind vegetation, unlikethe cooperative strategies employed by female lionsin open grassy savannas. By strongly linking malelion-hunting behavior to dense vegetation, thisstudy suggests that changes to vegetation structure—suchas through fire management—couldgreatly alter the balance between predator and prey.With large mammals increasingly confined to protectedareas, understanding how to maintain theirhabitat to best support their natural behavior is acritical conservation priority.The authors emphasized that their findingsshould be confirmed in other studies throughoutAfrica’s savannas. Nevertheless, these results couldhave major implications <strong>for</strong> park management,which is often heavily involved with manipulatingvegetation. Animal Behavior published their workin March.Instrumentation is mounted on the fixed-wing<strong>Carnegie</strong> Airborne Observatory plane.A grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation funded this research.The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Grantham Foundation <strong>for</strong>the Protection of the Environment, Avatar Alliance Foundation, W. M.Keck Foundation, the Margaret A. Cargill Foundation, Mary Anne NyburgBaker and G. Leonard Baker, Jr., and William R. Hearst III make the<strong>Carnegie</strong> Airborne Observatory possible.

Image courtesy NASAA research team led by<strong>Carnegie</strong>’s Anna Michalakdetermined that the 2011record-breaking algal bloom inLake Erie was triggered by longtermagricultural practices coupledwith extreme precipitation,followed by weak lake circulationand warm temperatures.The team also predicted that,unless agricultural policieschange, the lake will continue toexperience extreme blooms. Theresearch, published in the Proceedingsof the National Academyof <strong>Science</strong>s in April, was widelycovered by the media.Freshwater algal blooms canresult when excessive amountsof phosphorus and nitrogen areadded to the water, typically asrunoff from agricultural fertilizer.These excess nutrients encourageunusual algae andThis NASA Landsat 5 imageshows the record-breaking algalbloom in Lake Erie in October2011. The green scum is mostlyMicrocystis, a toxin to mammals.algalBlooms GoViralaquatic plant growth. When theplants and algae die, the decomposersthat feed on them use upoxygen, which can drop to levelstoo low <strong>for</strong> aquatic life to thrive.In the beginning, the Lake Eriealgae were almost entirely Microcystis,an organism that producesa liver toxin and can causeskin irritation.The scientists combined samplingand satellite-based observationsof the lake with computersimulations. The algalbloom began in the western regionof the lake in mid-July andcovered an area of 230 squaremiles (600 km 2 ). At its peak inOctober, the bloom had expandedto over 1,930 squaremiles (5,000 km 2 ). Its peak intensitywas over three timesgreater than any other algalbloom on record.The researchers looked atnumerous factors that couldhave contributed to the bloom,including land use, agriculturalpractices, runoff, wind, temperature,precipitation, andcirculation. The use of threeagricultural nutrient managementpractices in the areacould lead to increased nutrientrunoff: autumn fertilization,broadcast fertilization,and reduced tillage. Thesepractices have increased in theregion over the last decade.Conditions in the fall of 2010were ideal <strong>for</strong> harvesting andpreparing the fields, includingAnna Michalak<strong>Carnegie</strong> <strong>Science</strong> | Summer 2013 11increasing fertilizer application<strong>for</strong> the following spring’s planting.A series of strong storms inthe spring of 2011 caused largeamounts of phosphorus to runoff into the lake. This onslaughtresulted in among the largestobserved spring phosphorusloads since 1975, when intensivemonitoring began. Lake Eriewas not unusually calm andwarm be<strong>for</strong>e the bloom. Butafter the bloom began, warmerwater and weaker currents encourageda more productivebloom than in prior years. Thelonger period of weak circulationand warmer temperatureshelped incubate the bloom andallowed the Microcystis to remainnear the topof the water column,which hadthe added effect ofpreventing the nutrientsfrom beingflushed out of thesystem.To determine thelikelihood of futuremegablooms, thescientists analyzedclimate simulations under bothpast and future climate conditions.They found that severestorms become more likely inthe future; stronger storms,with greater than 1.2 inches(30 mm) of rain, could betwice as frequent. The authorsalso said that future calm conditionsin between storms, withweak lake circulation afterbloom onset is also likely tocontinue since current trendsshow decreasing wind speedsacross the U.S. This would resultin longer-lasting bloomsand decreased mixing in thewater column.This research is based upon work supported by the National <strong>Science</strong> Foundation (NSF)Water Sustainability and Climate program under grant no. 1039043, Extreme eventsimpacts on water quality in the Great Lakes: Prediction and management of nutrientloading in a changing climate (see www.miseagrant.umich.edu/nsfclimate). Additionalsupport <strong>for</strong> some of the co-authors was provided by NSF grant no. 0927643, the NOAACenter <strong>for</strong> Sponsored Coastal Ocean Research grant NA07OAR432000, and Lake ErieProtection Fund #SG 406-2011.

12Researchers still have much to learnabout the volcanism that shaped our planet’searly history. New evidence from a team led by<strong>Carnegie</strong>’s Frances Jenner demonstrates thatsome of the tectonic processes driving volcanicactivity, such as those taking place today,were occurring as early as 3.8 billion years ago.Upwelling and melting of the Earth’s mantleat mid-ocean ridges, as well as the eruptionof new magmas on the seafloor, drive thecontinual production of the oceanic crust.As the oceanic crust moves away from themid-ocean ridges and cools, it becomesdenser than the underlying mantle. Overtime the majority of this oceanic crust sinksback into the mantle, which can trigger furthervolcanic eruptions. This process isknown as subduction, and it takes place atplate boundaries.Volcanic eruptions that are triggered bysubduction of oceanic crust are chemicallydistinct from those erupting at mid-oceanridges and oceanic island chains, such asHawaii. The differences between the chemistryof magmas produced at each of thesetectonic settings provide geochemical fingerprintsthat can be used to try to identifythe types of tectonic activity taking placeearly in the Earth’s history.Previous geochemical studies have usedsimilarities between modern subduction zonemagmas and magmas that erupted about 3.8billion years ago, during the Eoarchean era, to<strong>Sleuthing</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Tectonics</strong>argue that subduction-style tectonic activitywas taking place early in the Earth’s history.But no one has been able to locate volcanicrock with compositions comparable to modernmid-ocean ridge or oceanic island magmasthat were older than 3 billion years and werefree from contamination by continental crust.Because of this missing piece of the puzzle,it has been ambiguous whether thesubduction-like compositions of volcanicrocks that erupted 3.8 billionyears ago were really generated at subductionzones, or whether this magmatism should beattributed to other processes taking placeearly in the Earth’s history. Consequently,evidence <strong>for</strong> subduction-related tectonics earlierthan 3 billion years ago has been highlydebated in the scientific literature.Jenner and her team collected 3.8-billionyear-oldvolcanic rocks from Innersuartuut,an island in southwest Greenland, and foundthat the samples have compositions comparableto modern oceanic islands, such asHawaii. The Innersuartuut samples may representthe world’s oldest recognized collectionof oceanic island basalts, free from contaminationby continental crust. As such, thisevidence strengthens previous arguments thatsubduction of oceanic crust into the mantlehas been taking place since at least 3.8 billionyears ago. Geology published their work inJanuary.Oceanic crustLithosphereTrenchIsland arcContinentalcrustLithosphereAsthenosphereOceanic-oceanic convergenceThe Earth’s plates move and can slideunder each other in a process calledsubduction, which can causevolcanic eruptions.Image courtesy USGSJenner and her teamcollected 3.8-billionyear-oldvolcanic rocksfrom Innersuartuut, anisland in southwestGreenland. This NASAimage shows theGreenland region.Image courtesy NASA Goddard’s Scientific Visualization StudioAn Australian International Postgraduate Research Scholarship, a Ringwood Scholarship,an ARC Discovery grant, and an NERC grant gave support to the authors of this study.

Image courtesy Argonne National LaboratoryHigh-energy X-rays are producedin vast facilities like the AdvancedPhoton Source shown here.13SynchrotronBCXDIHighly coherent X-rays from synchrotron sources canbe used <strong>for</strong> imaging nanomaterials in 3-D at tens ofnanometers of spatial resolution. This image shows amonochromatic hard X-ray pattern from a single crystalgold particle, which produces a speckle-like fringe image.Image courtesy Wenge YangRNANOT E CHNOLOGYAKTHROUGHA team of researchers including <strong>Carnegie</strong>’s Wenge Yang madea major breakthrough in measuring the structure of nanomaterialsunder extremely high pressures. The team developed a way to getaround the severe distortions of high-energy X-ray beams that areused to image the structure of gold nanocrystals. This techniquecould lead not only to advancements of new nanomaterials createdunder high pressures, but also a greater understanding of what ishappening in planetary interiors. Nature Communications publishedthis work in April.High pressures fundamentally change many properties of goldnanocrystals. The only way <strong>for</strong> researchers to see what happens tosuch samples when under pressure is to use high-energy X-rays producedby synchrotron sources. Synchrotrons can provide highly coherentX-rays <strong>for</strong> advanced 3-D imaging with resolution of tens ofnanometers. This is different from the incoherent X-ray imagingwith micron spatial resolution used <strong>for</strong> medical examinations.The team found that by averaging the patterns of the bentwaves—diffraction patterns—of the same crystal using differentsample alignments of the instrumentation and by using a speciallydeveloped algorithm, they could compensate <strong>for</strong> the distortionand improve spatial resolution by two orders of magnitude. This isanalogous to prescribing eyeglasses <strong>for</strong> the diamond anvil cell to correctthe vision of the coherent X-ray imaging system.The researchers subjected a 400-nanometer (.000015 inch) singlecrystal of gold to pressures from about 8,000 times the pressure at sealevel to 64,000 times that pressure. This latter is about the pressure inEarth’s upper mantle, the layer between the outer core and the crust.They compressed the gold nanocrystal and found, as expected, thatthe edges of the crystal became sharp and strained. But to their completesurprise, the strains disappeared upon further compression. Thecrystal developed a more rounded shape at the highest pressure, implyingan unusual plastic-like flow.Gold nanocrystals are very useful materials. They are about 60%stiffer compared with other micron–sized particles, and they couldprove pivotal <strong>for</strong> constructing improved molecular electrodes,nanoscale coatings, and other advancedengineering materials. This new structuremeasurement technique will be critical<strong>for</strong> advances in these areas.Now that the distortion problem hasbeen solved, the whole field of nanocrystalstructures under pressure can be accessed.The scientific mystery of whynanocrystals under pressure are somehowstronger than bulk material maysoon be unraveled. Wenge YangEFree, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by DOE-BES, supported thiswork. DOE-BES supports the Advanced Photon Source.

14<strong>Carnegie</strong> <strong>Science</strong> | Summer 2013This watercolorillustration shows thefruit fly, Drosophilamelanogaster, byEdith M. Wallace.CanSex ShedLight onCancer?Studying successfulovulation“and fertilizationin fruit flies has shed lighton these processes.”Eggs take a long time to producein the ovary. Researchersthink that the body has mechanismsto help an ovary ensure thatovulated eggs enter the reproductivetract at a time that maximizesthe chance of fertilization.Studying successful ovulationand fertilization in fruit flies hasshed light on these processes. Researchfrom <strong>Carnegie</strong>’s AllanSpradling and Jianjun Sun foundthat secretions from special glandswithin the fruit fly’s reproductivetract contribute to both ovulationand sperm function and that thehormone receptor gene Hr39controls this secretion. Their resultsalso suggest that Lrh-1, amammalian receptor gene closelyrelated to Hr39, regulates ovulation by controllingreproductive tract secretions in mammals.The biological processes underlying specifichuman tissues are often fundamentallysimilar to analogous tissues in seemingly verydifferent species, even insects. These commonprocesses are a consequence of the commonevolutionary history of virtually all multicellularorganisms. As a result of thesesimilarities, researchers can genetically manipulatefruit flies to identify the genes andpathways controlling a biological process—inthis case ovulation—and then use genome sequencingto identify the corresponding genesin other species, including humans.Spradling and Sun began such a strategya few years ago by characterizing how the secretoryglands within the ovary develop. Usingadvanced tools, they confirmed that oneimportant role of reproductive tract secretionsis to protect and store sperm; in humans,sperm is stored in the isthmus regionof the fallopian tube. Sperm are thought topersist in the isthmus <strong>for</strong> only a few days, butthey can last <strong>for</strong> a week or more in fruitflies. When reproductive tract secretion productionis compromised, sperm have difficultygetting to the gland and those that canget there undergo abnormal changes.The secretory “machinery” studied inthese experiments may also allow the reproductivetract to signal the ovary when itis ready to receive an egg. Waiting <strong>for</strong> such asignal be<strong>for</strong>e releasing an egg could reducethe chance that an egg would fail to enter thereproductive tract or arrive be<strong>for</strong>e activesperm were available.Spradling and Sun’s work shows that differentsecretions are responsible <strong>for</strong> ovulationand <strong>for</strong> attracting and storing sperm.Identifying the specific secretory cell products(and the corresponding genes) required<strong>for</strong> successful ovulation is an important stepin understanding the mechanisms of thisstill-mysterious process.Their research also has a possibleconnection to one of themost common <strong>for</strong>ms of ovariancancer, one that derives from abnormalitiesin reproductive tractsecretory cells. The genes andpathways that cells use in carryingout their normal functionsare often the targets of the alterationsthat drive cancer cellgrowth. Spradling and Sun’swork could stimulate an investigationof the role that genes suchas Lrh1 play in this devastatingdisease. eLife published the findingsin April.Above center: This microscopic imageshows the <strong>for</strong>mation of a fruit fly egg cell.Above: Allan Spradling and Jianjun SunThe Howard Hughes Medical Institute provided funding <strong>for</strong> this research.

<strong>Carnegie</strong> <strong>Science</strong> | Summer 2013 15InBriefImage courtesy Christine Pratt Above right: <strong>Carnegie</strong> presidentMeserve was the keynote speaker at theBiennial General Meeting of the WorldAssociation of Nuclear Operators inMoscow in May. Trustee Michael Long, third fromleft, and <strong>Carnegie</strong> president RichardMeserve, fifth from left, were amongthe group of visitors to <strong>Carnegie</strong>’s LasCampanas Observatory in Mar. Imagecourtesy Miguel Roth Participants gathered <strong>for</strong> a symposiumin honor of Joe Gall’s 85th birthday. Juliana Carten Shintaro IwasakiTRUSTEES ANDADMINISTRATION <strong>Carnegie</strong> president Richard A.Meserve testified be<strong>for</strong>e the HouseCommittee on Energy and CommerceSubcommittee on Oversight andInvestigations on Mar. 13 in Washington,DC, on an investigation on security atDOE weapon facilities he undertook atthe request of the Department ofEnergy’s (DOE’s) then-Secretary StevenChu. He chaired a meeting of the DOE’sNuclear Energy Advisory Committee onMar. 14 and June 13 in Washington, DC.He chaired a meeting of the InternationalAtomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA’s)international technical advisory group onMar. 21-22 and June 10-11 and chairedthe meeting of the IAEA’s InternationalNuclear Safety Group on Apr. 23-24, allin Vienna, Austria. He visited the LasCampanas Observatory in Chile on Mar.26-29 with a group of guests, includingboard member Michael Long. Meserveparticipated in a meeting of the VisitingCommittee to the Harvard KennedySchool of Government on Mar. 3-5 andpresided at meetings of the HarvardBoard of Overseers on Mar. 6-7 andMay 28-29, all in Cambridge, MA. Hewas a speaker on the lessons of theFukushima accident at an eventsponsored by the IAEA and the CanadianNuclear Safety Commission on Mar. 9 inOttawa, Canada. He attended meetingsof the Council and Trust of the AmericanAcademy of Arts and <strong>Science</strong>s inCambridge, MA, on Apr. 18-19. Hechaired a panel on advanced nucleartechnologies at the National Academyof <strong>Science</strong>s’ annual meeting on Apr. 28in Washington, DC. He introduced<strong>for</strong>mer Secretary of Energy Steven Chuat a stated meeting of the AmericanAcademy of Arts and <strong>Science</strong>s onMay 8 in Cambridge, MA. He attendedmeetings of the Council of the NationalAcademy of Engineering on May 9-10 inWashington, DC. Meserve cochaired ameeting of the National Academies’Committee on <strong>Science</strong>, Technology, andLaw on May 13-14, also in Washington,DC. He joined the celebration of thedesignation of the Department ofTerrestrial Magnetism as an AmericanPhysical Society historical site, thanksto the work of Vera Rubin and Kent Fordconfirming the existence of dark matter,on May 17. Meserve gave the keynoteaddress at the World Association ofNuclear Operators Biennial GeneralMeeting on May 20 in Moscow.EMBRYOLOGYDirector Allan Spradling was an invitedspeaker at the Keystone Symposia“Stem Cell Regulation in Homeostasisand Disease.” He also presentedseminars at UCLA, The Johns Hopkinsmedical institutes, and BiogenIDEC.Spradling attended the AnnualDrosophila Research Conference inWashington, DC. Also attending theconference and presenting posters weregraduate student Alexis Marianes andpostdocs Steven DeLuca, MeghaGhildiyal, Ethan Greenblatt, Ming-ChiaLee, Robert Levis, and Vicki Losick.— A two-day symposium in honor ofJoe Gall’s 85th birthday was held at thedepartment Apr. 12-14. There were over130 attendees including family, localand long-distance colleagues, currentlab members, and Gall lab alumni fromaround the globe.—Yixian Zheng presented a seminar inShanghai and met with collaborators.—Marnie Halpern presented her work atGeorgetown U. and was the keynotespeaker at the Regional Mid-AtlanticSociety <strong>for</strong> Developmental Biologymeeting at the College of William andMary in Williamsburg, VA.—Alex Bortvin was an invited speaker atthe Keystone Symposia “RNA Silencing.”—Steve Farber presented his work andchaired a session in a workshop onusing zebrafish in K-12 education at theStrategic Conference of Zebrafish Investigatorsin Asilomar, CA. He also attendedthe DEUEL Conference on Lipidsin Napa Valley, CA. Postdoc Jessica Otisalso attended the conference and presenteda poster.—Nick Ingolia was an invited speaker atColumbia U.—Christoph Lepper was an invitedspeaker at U. Kentucky.—Spradling postdoc Ethan Greenblatt receiveda three-year postdoctoral fellowshipaward from the Jane Coffin ChildsFund to support his project “UnderstandingNuclear Aging in theDrosophila Follicle Stem Cell Lineage.”—Gall lab’s postdoc Jun-Wei Pek receiveda three-year postdoctoral fellowshipfrom the Life <strong>Science</strong>s Research Foundationto support his project “Stable IntronicSequences (sis) RNA: NovelFunctions and Biogenesis Pathways.”—Halpern lab undergraduate researcherAlice Hung received a Johns HopkinsUniversity (JHU) Provost’s UndergraduateResearch Award <strong>for</strong> her work in theHalpern lab. Alice presented a poster“Tissue Specific Activation of EstrogenSignaling in Development” at the awardceremony.— Farber lab’s Juliana Cartensuccessfully defended her Ph.D. thesis“Lipids and Microbes and Sugars, OhMy! Investigating Microbial and DietaryInfluences on Fatty Acid Metabolism.”—The Fan lab’s Micah Webster received athree-year postdoctoral fellowship awardfrom the American Cancer Society to supporthis project “c-Met’s Role in SatelliteCells During Muscle Regeneration.”— Arrivals: Steven DeLuca joined theSpradling lab as a postdoc from UC-SanFrancisco. Student volunteer MaddieGoodman also joined the Spradling lab.Shintaro Iwasaki joined the Ingolia labas a postdoc from U. Tokyo. Iwasaki isthe recipient of both a Japan Society <strong>for</strong>the Promotion of <strong>Science</strong> award and aHuman Frontier <strong>Science</strong> Programfellowship <strong>for</strong> his proposal on miRNAmediated translational activation byribosome profiling. Lab technicianStephanie Kuo joined the Lepper lab,and animal technician Andrew Rockjoined the fish facility.—Departures: Former graduate studentKatie McDole left the Zheng lab to beginpostdoctoral studies in Phillip Keller’slab at the Janelia Farm Research Campus.Postdoc Helan Xiao also left the labafter completing her postdoctoral project.Julio Castañeda is leaving theBortvin lab <strong>for</strong> a postdoctoral positionwith Martin Matzuk at Baylor College ofMedicine. Lab technician Reid Woodsleft the Lepper lab to pursue a medicaldegree. Business manager DavidLawrence and animal technicianBrittany Hay left the department.GEOPHYSICAL LABORATORYRobert Hazen delivered a Linus PaulingMemorial Lecture in Portland, OR; an“Evolution Matters” lecture at Harvard;and a Naff Lecture at U. Kentucky-Lexington.He was a keynote speaker at theGordon Research Conference in Ventura,CA; at the Deep Carbon <strong>Science</strong> meetingin Washington, DC; at the EarthCubeStakeholders Workshop in Washington,DC; and at the Earth-Life <strong>Science</strong> Insti-

16Deep CarbonObservatory A number of GL/CDAC affiliated staffattended the Mössbauer symposium,including Viktor Struzhkin, Jung-Fu Lin,Brent Fultz, and graduate students.Carbon in Earth is the first major collectivepublication of the Deep Carbon Observatory(DCO). This special open-access volumeprovides an astonishing look at the newfield of deep carbon science. The 700-pagebook contains 20 chapters by more than 50researchers from nine countries, includingRobert Hazen, Russell Hemley, CraigSchiffries, and Anat Shahar from the GeophysicalLaboratory and Conel Alexanderand Steven Shirey from DTM. Carbon inEarth was launched at the DCO International<strong>Science</strong> Meeting, which was held atthe US National Academy of <strong>Science</strong>s onMar. 3-5. The meeting engaged more than160 researchers from around the world, includingmany current and <strong>for</strong>mer <strong>Carnegie</strong>researchers. Richard Meserve providedopening remarks. Russell Hemley moderateda panel discussion with Wendy Harrison(NSF Earth <strong>Science</strong>s Division Director;<strong>for</strong>mer Geophysical Lab predoctoral fellow),P. Patrick Leahy (AGI Executive Director),Marcia McNutt (USGS Director, 2009-2013),and Frank Press (National Academy of <strong>Science</strong>sPresident, 1982-1993; Cecil and IdaGreen Senior Fellow at <strong>Carnegie</strong>, 1993-1997). Perhaps nobody had a greater indirectimpact than Douglas Rumble, who’shad three <strong>for</strong>mer postdoctoral fellows—Shuhei Ono, Craig Schiffries, and EdwardYoung—on the plenary program. DCO held aDeep Energy Workshop in Manchester, England,Jan. 30-Feb. 1; an executive committeemeeting in Washington, DC, on Mar. 5;and a workshop on abiotic hydrocarbons inKazan, Russia, Apr. 13-17.Top: The Deep Carbon Observatory executive committee metin the boardroom of the National Academy of <strong>Science</strong>s onMar. 5. Front row (from left): Jesse Ausubel (US), IsabelleDaniel (France), Adrian Jones (UK), John Baross (US).Middle row (from left): Sara Hickox (US), Craig Manning (US),Nickolay Sobolev (Russia), Russell Hemley (US), BarbaraSherwood Lollar (Canada), Eiji Ohtani (Japan), TarasBryndzia. Back row (from left): Craig Schiffries (US), Kai-Uwe Hinrichs (Germany), David Cole (US), Robert Hazen(US), Erik Hauri (US), Claude Jaupart (France).Members of the International<strong>Science</strong> Meeting of the DCOpresented recent findings in Mar.From left to right: Frank Press, P.Patrick Leahy, Marcia McNutt,Wendy Harrison, Russell Hemley.Images courtesy Craig Schiffries Greg Asner (left) attended the St.James Palace meeting on tropical<strong>for</strong>est science in London May 8, wherehe met Prince Charles.Image courtesy © Paul Burns Ken Caldeira Anna Michalak Yunatao Zhoutute International <strong>Science</strong> Conference inTokyo, Japan, to which he was alsonamed to the advisory board. He also lecturedon the coevolution of the geosphereand biosphere at Harvard U.; ArizonaState U.; Rockefeller U.; the Cliff Salon,Scientists Cliffs, MD; and the Alfred P.Sloan Foundation in New York City.—Director Emeritus Wesley Huntress retiredfrom service after completing hissecond term on NASA’s Advisory Council(NAC) and as chair of the NAC <strong>Science</strong>Committee in Apr.—Ho-kwang (Dave) Mao presented theplenary speech “Breakthroughs in HighPressure <strong>Science</strong> and Technology” at theStudy of Matter at Extreme Conditions(SMEC) 2013 cruise meeting on Mar. 23.He also delivered a plenary talk “EnergyFrontier Research in Extreme Environments”at the GCOE-TANDEM InternationalSymposium 2013 on Mar. 6 inMatsuyama, Japan.— Postdoctoral fellow Caitlin Murphypresented an invited talk at the 7thNorth American Mössbauer Symposiumon Jan. 10-12 at U. Texas-Austin. It wasorganized by Geophysical Lab alumJung-Fu (Afu) Lin. Caitlin alsopresented a geochemistry seminar at U.Maryland-College Park on Jan. 30.—Microbeam specialist Katherine Crispingave an invited talk “Diffusion in Oxidesand Implications <strong>for</strong> Mantle Mineralogy”and a diffusion seminar at the Lamont-Doherty Observatory, Columbia U., onApr. 17.—HPSYNC/HPCATYuming Xiao attended the 7th NorthAmerican Mössbauer Symposium inAustin, TX, on Jan. 11-12 and gave aninvited talk on nuclear resonant scatteringunder high pressure at HPCAT.GLOBAL ECOLOGYDirector Chris Field was the keynotespeaker at a convention of broadcastmeteorologists at Lake Tahoe in Jan. Hepresented a keynote address at the EuropeanClimate Change Adaptation Conferencein Hamburg, Germany, in Mar.and the “Earth Matters DistinguishedLecture” at the Stan<strong>for</strong>d School of Earth<strong>Science</strong>s that month.— Greg Asner and the CAOspectranomics team made a collectingtrip to Panama’s Barro Colorado Islandin Jan. The team included Robin Martin,Byron Tsang, Katie Kryston, KellyMcManus, and three Peruvian climbers.— Ken Caldeira, Jana Maclaren, andLilian Calderia spent five weeks inFeb./Mar. on One Tree Island on Australia’sGreat Barrier Reef. They were involved infield studies, testing the consequences ofantacid in the ocean water <strong>for</strong> the growthof coral. NPR’s Richard Harris joined thefield expedition and featured it in twostories, one on All Things Considered andone on Morning Edition.— Anna Michalak was appointed editorof the journal Water ResourcesResearch, a premier journal <strong>for</strong>hydrology and water resourcespublished by the American GeophysicalUnion (AGU). She is the first womaneditor of the journal in its 50-yearhistory. Michalak was invited to becomea member of the <strong>Science</strong> Advisory Boardof the Climate Change <strong>Science</strong> Instituteat Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Shegave a keynote address at the NorthAmerican Carbon Program All-Investigators Meeting in Albuquerque,NM, and was an invited panelist at theSociety <strong>for</strong> Industrial and AppliedMathematics (SIAM) Conference onComputational <strong>Science</strong> and Engineering.— Yuntao Zhou defended herdissertation “Improved Estimates of theSpatial Distribution and TemporalTrends of Water Quality ParametersUsing Geostatistical Data FusionMethods” on Jan. 15th.—

<strong>Carnegie</strong> <strong>Science</strong> | Summer 2013 17 Andrew McWilliam Winslow Briggs Jóse Dinneny Plant Biologydirector WolfFrommer Sue Rhee Devaki BhayaYoichi Shiga won an Outstanding StudentPaper Award from the AGU <strong>for</strong> hispresentation “Exploring the Ability of InverseMethods to Isolate the Fossil FuelEmission Signal from Atmospheric CO 2Measurements” at the AGU fall meetingin San Francisco.—Shouren Zhang, from the Chinese Instituteof Botany in Beijing, is visiting theBerry Lab through the end of Aug. Hehas worked mostly on the ecophysiologyof trees.—Arrivals: Xuemei (Mei) Qiu joined theMichalak lab as a scientific programmerin Feb. Jovan Tadic became postdoctoralresearcher in that lab in Mar. BrandoPaolo began a postdoc position in theAsner lab, while Byron Tsang joined asa lab manager and Katherine Krystonas a lab technician, all in Jan. MorvaridTavassoli began working as a labtechnician <strong>for</strong> the Field Lab in Jan.—Departures: Predoctorial visitor DarioCaro, in the Caldeira lab, returned tohis home in Italy in Apr.OBSERVATORIESDirector Wendy Freedman attended aPhysics of the Universe Summit, in WestHollywood, CA, Jan. 11-13. On Jan. 23she gave a colloquium on the cosmicdistance scale at U. Chile. She and LasCampanas director Miguel Roth visitedthe Fundación Chile to introduce astronomyinto the K-12 curriculum. She presenteda talk on recent results on theHubble constant at the Canadian Institute<strong>for</strong> Advanced Research Feb. 15-17.Apr. 1-5 she attended an internationalmeeting in the Netherlands, discussingthe implications of the Planck results <strong>for</strong>cosmology. On Apr. 22 Freedman gave acolloquium on recent measurements ofthe Hubble constant at U. Pennsylvania.She also gave the Elon Musk Public Lecture“A Journey of Discovery: Our ExpandingUniverse.” During Mar. and Apr.she gave four talks to groups in the LosAngeles area on the Giant Magellan Telescope(GMT).— Staff astronomer Andrew McWilliamgave an astronomy colloquium at TexasA&M U. titled “Chemical Evolution,Nucleosynthesis and the ChemicalComposition of Stars in Dwarf Galaxies”on Apr. 1.—Staff members Luis Ho and Barry Madoreand <strong>Carnegie</strong> fellow Guillermo Blanc attendeda meeting Mar. 24-29 in Lijiang,China, titled “Dissecting Galaxies with 2DWide-Field Spectroscopy.” Ho chaired theScientific Organizing Committee <strong>for</strong> the internationalmeeting and hosted a workshopon black holes at the Key Laboratory<strong>for</strong> Particle Astrophysics (CAS). Madoregave the first public talk on TYPHOON, anew application of the wide-field CCD onthe Iréné du Pont 2.5-meter telescope atLas Campanas to produce data cubes <strong>for</strong>galaxies of extremely large angular size.Guillermo talked about VENGA, the instrumenthe used <strong>for</strong> his U. Texas thesis.—Luis Ho also gave colloquia at the NationalAstronomical Observatories, ChineseAcademy of <strong>Science</strong>s (NAOC) andHong Kong U.—Staff astronomer Josh Simon gave thecolloquium at UC-Santa Cruz on Jan. 30.—On Mar. 12, staff associate Andrew Bensongave a talk “What Can TheoreticalModels Predict <strong>for</strong> GMTIFS Observations?”at the GMT Integral-Field Spectrograph(GMTIFS) workshop held at theObservatories. He presented the openingtalk “Galaxy Formation Models:Past, Present & Future” on Mar. 21 atthe Stimulating Universes <strong>for</strong> FutureSurveys meeting at the InternationalCenter <strong>for</strong> Radio Astronomy Researchat U. Western Australia, Perth.—In Jan. postdoctoral research associateNimish Hathi attended the American AstronomicalSociety meeting in LongBeach, CA, and gave the talk “InvestigatingHST/WFC3 Selected Lyman BreakGalaxies at z=1-3” in an HST UV specialsession. He was also a judge <strong>for</strong> theChambliss Poster Award at this meeting.—Postdoctoral research associate RikWilliams gave an invited talk at the Institute<strong>for</strong> the Physics and Mathematics ofthe Universe, Tokyo, Japan, titled “GalaxyEvolution in the Thermal Era” on Jan. 23.PLANT BIOLOGY On Feb. 1 director Wolf Frommerpresented the Nathan Edward TolbertLectureship in Plant Biochemistryseminar at Michigan State U., EastLansing, titled “In vivo Biochemistry withthe Help of Genetically EncodedSensors.” He gave a Pioneers inGenomics Lecture titled “A Multi-Pronged Approach to Plant Nutrition:Pico-Sensors <strong>for</strong> Transport GeneDiscovery and Regulation” at U. Illinois-Urbana on Feb. 26, and he presented thesame talk <strong>for</strong> the Distinguished Lecturesin Life <strong>Science</strong> at Pennsylvania State U.,University Park, on Feb. 27. On Mar. 13-15 he attended the Grand ChallengesExplorations (GCE) Agriculture &Nutrition Awardee Convening in Seattle,WA, and presented a poster aboutsecuring the global food supply by cropimmunization. On Mar. 24 he attendedthe International Workshop on PlantMembrane Biology held in Kurashiki,Japan, and gave a seminar on nutrientuptake and translocation.— On Feb. 3 Winslow Briggs gave aseminar at Global Ecology on plant firesurvival. On Apr. 13 Briggs gave asimilar lecture and then led a four-hourfield trip <strong>for</strong> the docents of the Stan<strong>for</strong>dU. Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve onGreg Asner Elected to the NationalAcademy of <strong>Science</strong>s (NAS)Greg Asner (right) is one of 84 new NAS members and 21 <strong>for</strong>eign associatesfrom 14 countries elected this April “in recognition of their distinguishedand continuing achievements in original research.” The total number ofactive members now stands at 2,179.Asner was hired in 2001 as the Department of Global Ecology’s firststaff scientist. Since coming to <strong>Carnegie</strong>, he has pioneered new methods<strong>for</strong> investigating tropical de<strong>for</strong>estation, degradation, ecosystem diversity,invasive species, carbon emissions, climate change, and much more usingsatellite and airborne instrumentation. His innovations measure the chemistry,structure, biomass, and biodiversity of the Earth in unprecedenteddetail over massive areas not thought possible be<strong>for</strong>e. He has developednew technologies <strong>for</strong> conservation assessments, including tropical <strong>for</strong>estcarbon emissions and stocks, hydrologic function, and biodiversity. He leadsthe CLASLite <strong>for</strong>est change mapping project, spectranomics biodiversityproject, and the one of a kind <strong>Carnegie</strong> Airborne Observatory (CAO).

18<strong>Carnegie</strong> Astronomy Lecture SpeakersThe <strong>Carnegie</strong> Astronomy Lecture Series eleventh season was at the PasadenaConvention Center in Pasadena this year. <strong>Carnegie</strong>-Princeton/Hubble FellowMansi Kasliwal gave the first lecture, “Fireworks Lighting Our Universe,” on Apr. 8.Other presenters were Scott Sheppard, staff scientist at Terrestrial Magnetism,postdoctoral associate Jeff Rich, and <strong>Carnegie</strong> fellow Ian Roederer.Mansi Kasliwal Scott Sheppard Jeff Rich Ian Roederer DTM director Lindy Elkins-Tantonwith Brent Sherwood (JPL) attended theposter session during the 44th LPSC inHouston, TX. Staff scientist Alycia Weinbergerparticipated in commissioning theMagellan Adaptive Optics system atLas Campanas Observatory in Apr.the recovery of vegetation in Henry W.Coe State Park, which he has beenstudying since a 2007 wildfire.—Zhiyong Wang gave a seminar at U.Texas-Austin on Mar. 19 about hormonaland environmental signaling crosstalk inArabidopsis. On Apr. 9 he gave a talk onplant signal integration in developmentat the Howard Hughes Medical Institute(HHMI) as a semifinalist of the HHMI InvestigatorCompetition. He gave twotalks on brassinosteroids signaling networksat the IV Brazilian Symposium onPlant Molecular Genetics in BentoGonçalves, Brazil, on Apr. 11.— On Mar. 4-6 Sue Rhee talked aboutgenomic signatures of plant-specializedmetabolism at the Evolution ofMetabolic Diversity held at the BanburyCenter, Cold Spring Harbor Labs, NY.— Jóse Dinneny spoke about how localenvironmental cues control branching inroots at the American Society of PlantBiologists (ASPB) Western Section Meeting2013, held in Davis, CA, on Apr. 12-13.— On May 1 Devaki Bhaya presented aninvited talk on the context and conflict inmicrobial communities at the Frontiersin Biology conference at Stan<strong>for</strong>d U.—Matt Evans and postdoctoral researchersAntony Chettoor and YongxianLu attended the 55th Annual MaizeGenetics Conference Mar. 14-17 in St.Charles, IL. Lu presented posters at theSustainable Plant Yield in a ChangingClimate, ASPB meeting in Davis, CA, onApr. 12-13.—Eva Huala gave two talks, “ArabidopsisPhenotype Representation Using Ontologies”and “Application of Ontologies toPlant Gene Function and PhenotypeData,” at the Plant and Animal Genome(PAG) XXI, International Arabidopsis In<strong>for</strong>maticsConsortium Workshop heldJan. 12-16 in San Diego, CA. She presenteda seminar at the Third PhenotypeRCN Summit held Feb. 25-27 at theNational Evolutionary Synthesis Center,Durham, NC.—Donghui Li, a curator in the TAIR group,gave the talk “Gene Ontology Task atBioCreative IV” at the Sixth InternationalBiocuration Conference Apr. 7-10 inCambridge, UK.—On Apr. 5-6 Bob Muller, lead curator inTAIR, talked about the PLAIN project atthe GMOD/Biocuration 2013 meeting inCambridge, UK.—Bhaya Lab postdoctoral associateAnchal Chandra attended a workshopheld Mar. 24-30 at the QB3 facility atMission Bay Campus, UC-San Francisco.The workshop focused on intensivemicroscope-based instruction.—Dinneny lab graduate students NeilRobbins II, Yu Geng, and Rui Wu andpostdoctoral researchers Lina Duan,Jóse Sebastian, and Ruben Rellan-Alvarez attended the ASPB WesternSection meeting on Apr. 12-13. Robbinsand Dinneny also attended the MaizeGenetics Conference, Mar. 14-17, in St.Charles, IL.—Arrivals: Garret Huntress joined the Departmentsof Plant Biology and GlobalEcology on Jan. 15 as the IT Manager. Hewas <strong>for</strong>merly at the Geophysical Laboratory.Visiting student Alejandra Londonofrom ICESI U. Colombia joined the Frommerlab on Feb. 12. Visiting graduate studentLauro Bucker joined the Wang lab onFeb.16 from Federal U. of Rio Grande doSul, Brazil. Samuel Hokin, a senior computationalscientist from U. Wisconsin,started work in the Barton lab on Jan. 15.—Departures: Postdoctoral researcherGuido Grossmann left the Frommer labon Dec. 31 to become a group leader atU. Heidelberg, Germany. Visiting researcherYang Bai departed from theWang lab on Jan. 18 to return to theHarbin Institute of Technology, China.On Feb. 8 Shanker Singh, a databaseadministrator in the TAIR group, left <strong>for</strong>a position in industry. Lab technicianErika Valle-Smith left the Frommer labon Mar. 28 <strong>for</strong> a biotech company.TERRESTRIAL MAGNETISM In Feb. director Lindy Elkins-Tantonpresented a talk at the Institute <strong>for</strong>Advanced Study, Princeton. She alsopresented a talk at U. Colorado-Boulder.In Feb. she was appointed to the NASAMars 2020 Rover <strong>Science</strong> Definitionteam. In Mar. Elkins-Tanton attended a“Committee on Astrobiology andPlanetary <strong>Science</strong> (CAPS)” meeting atthe NAS, an AGU Council Meeting, andthe 44th Lunar and Planetary <strong>Science</strong>Conference (LPSC) in TX where shepresented the plenary MasurskyLecture, cochaired the “PlanetaryDifferentiation Across the Solar System”session, and presented a poster. Shealso gave an invited talk at the“Volcanism, Impacts and MassExtinctions: Causes and Effects”conference at the Natural HistoryMuseum in London in Mar. In Apr.Elkins-Tanton led a mission-planningmeeting at JPL in Pasadena, CA. On Apr.15-16 she hosted a workshop on theSiberian flood basalts and the end-Permian extinction at DTM. On Apr. 23she cohosted a joint <strong>Carnegie</strong>/NASApublic lecture at <strong>Carnegie</strong>’s mainadministrative office in Washington, DC.On Apr. 29 a camera crew from HHMI,NOVA/PBS, and Holt Productions cameto interview her and visit the nanoSIMSlab where she, staff scientist Erik Hauri,and MIT researcher Ben Black isolatedand measured melt inclusions as part oftheir Siberia research. In May Elkins-Tanton attended the Kongsberg seminarat the Center <strong>for</strong> Earth Evolution andDynamics in Norway, where shedelivered the keynote lecture “MagmaOcean and Planetary Evolution.”—In Mar. Conel Alexander presented atthe 44th LPSC in Houston, TX.—In Jan. Alan Boss chaired NASA’s CarlSagan Fellowship review in Long Beach,CA. In Mar. Boss spoke about isotopichomogeneity and heterogeneity in thesolar nebula at the 44th LPSC in Houston,TX. In Apr. he gave a talk about theorbital evolution of dust grains duringFU Orionis outbursts at the meeting on