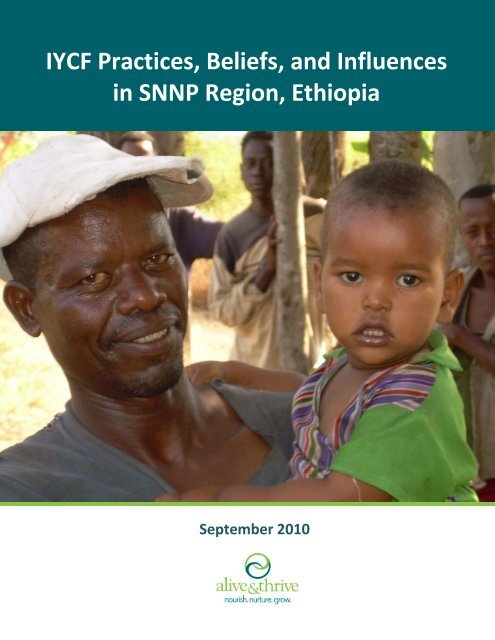

IYCF Practices, Beliefs, and Influences in SNNP ... - Alive & Thrive

IYCF Practices, Beliefs, and Influences in SNNP ... - Alive & Thrive

IYCF Practices, Beliefs, and Influences in SNNP ... - Alive & Thrive

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Acknowledgments<strong>Alive</strong> & <strong>Thrive</strong> acknowledges the special support of the <strong>SNNP</strong> Regional Health Bureau, the WoredaHealth Offices <strong>in</strong> Mareka, Misha <strong>and</strong> Chenicha for enabl<strong>in</strong>g us to undertake this formative research <strong>in</strong>the selected sites. More specifically, we would like to express our appreciation to the Woreda HealthExtension program heads of Mareka, Misha, <strong>and</strong> Chenicha. We also thank the health extensionworkers (HEWs) as well as the voluntary community health promoters (VCHPs) <strong>in</strong> the three woredasfor lead<strong>in</strong>g us to selected study participants <strong>and</strong> for shar<strong>in</strong>g their experiences <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant <strong>and</strong> young childfeed<strong>in</strong>g. We are <strong>in</strong>debted to the community members, especially the study participant mothers <strong>and</strong> otherfamily members, for shar<strong>in</strong>g their perceptions on local child feed<strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>and</strong> for spar<strong>in</strong>g theirvaluable time.<strong>Alive</strong> & <strong>Thrive</strong> acknowledges the professional consultancy service of Addis Cont<strong>in</strong>ental Institute ofPublic Health (ACIPH) for undertak<strong>in</strong>g this formative research. More specifically, we are thankful tothe research supervisors, Dr. Amare <strong>and</strong> Ms. Kidist, as well as all of the data collectors for theirdevotion <strong>and</strong> hard work.Staff members of <strong>Alive</strong> & <strong>Thrive</strong>, both at the headquarters <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>-country offices, who havecontributed <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>aliz<strong>in</strong>g this formative research report are deeply appreciated.<strong>Alive</strong> & <strong>Thrive</strong> is grateful for the f<strong>in</strong>ancial support for this formative research from the Bill & Mel<strong>in</strong>daGates Foundation.v

Abbreviations <strong>and</strong> AcronymsACIPHANCA&TAEDAIDSBCCCBNCMAMDALYsENAFGDF-MOHHEPHEWHIVIFHPIRB<strong>IYCF</strong>OTPORSPAHOPSNP<strong>SNNP</strong>USAIDVCHPAddis Cont<strong>in</strong>ental Institute of Public HealthAntenatal care<strong>Alive</strong> & <strong>Thrive</strong>Academy for Educational DevelopmentAcquired Immune Deficiency SyndromeBehavior change communicationCommunity-based nutritionCommunity-based management of malnutritionDisability adjusted life yearsEssential nutrition actionsFocus group discussionFederal M<strong>in</strong>istry of HealthHealth Extension ProgramHealth extension workerHuman immunodeficiency virusIntegrated Family Health ProgramInstitutional Review BoardInfant <strong>and</strong> young child feed<strong>in</strong>gOutpatient therapeutic programOral rehydration saltsPan American Health OrganizationProductive Safety Net ProgramSouthern Nations, Nationalities, <strong>and</strong> People’s (Region)United States Agency for International DevelopmentVoluntary community health promotersvii

GlossaryAabilaAtekanaBessoBullaChikoEnichelaEnsetMixture of barley flour <strong>and</strong> milkFood prepared from bulla mixed with milk <strong>and</strong> butter (used <strong>in</strong> the southern partsof Ethiopia)Food prepared from flour of roasted barley, with hot (not boiled) water; a thickversion is prepared with salt <strong>and</strong> butterThe white liquid extracted from the pseudostem of the enset (false banana plant)Food made of maize <strong>and</strong> wheat with kalePreparation from false bananaFalse banana plantFitfitFoseseInjeraInjera fitfitK<strong>in</strong>cheKitaKoloKotchoKurikufaMixture of <strong>in</strong>jera <strong>and</strong> stew or tomato sauceMaize flour dough, shaped <strong>in</strong>to a small ball <strong>and</strong> boiled with kale or a local leafcalled aleko/shiferaA flat th<strong>in</strong> bread resembl<strong>in</strong>g a pancake prepared from teff/barley/sorghumMixture of <strong>in</strong>jera with stewCracked barley or wheat boiled <strong>and</strong> later mixed with butter/oil <strong>and</strong> saltUnleavened flat bread prepared from teff/wheat/maize/ barleyRoasted cereals /legumes often made from barley, wheat, beans, chickpeasFermented food stuff from decorticated corm of the enset plant (false banana)Similar to fosese, maize flour is shaped <strong>in</strong>to a small ball <strong>and</strong> boiled with kale or alocal leaf called aleko/shiferaShiro wotTeffStew prepared from flour of roasted beans or peasT<strong>in</strong>y gra<strong>in</strong> used to prepare <strong>in</strong>jera or unleavened bread, known for its iron contentviii

Executive Summary<strong>Alive</strong> & <strong>Thrive</strong> Ethiopia undertook formative research to better underst<strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>fant <strong>and</strong> young childfeed<strong>in</strong>g (<strong>IYCF</strong>) practices <strong>in</strong> communities <strong>in</strong> Southern Nations, Nationalities, <strong>and</strong> People’s (<strong>SNNP</strong>)Region.The guid<strong>in</strong>g questions for the <strong>SNNP</strong> formative research, conducted <strong>in</strong> late 2009, were the follow<strong>in</strong>g:1. What are the beliefs <strong>and</strong> current practices for breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> complementary feed<strong>in</strong>g ofchildren <strong>in</strong> the study communities?2. What key factors <strong>in</strong>fluence mothers <strong>and</strong> family members to adopt recommended <strong>IYCF</strong>practices?3. Who <strong>in</strong>fluences mothers? What is the current role of family <strong>and</strong> community members tosupport optimal <strong>in</strong>fant <strong>and</strong> child feed<strong>in</strong>g practices?4. What is the current role of health extension workers (HEWs) <strong>and</strong> other health providers tosupport optimal <strong>in</strong>fant <strong>and</strong> child feed<strong>in</strong>g practices?5. What is the Health Extension Program (HEP) currently do<strong>in</strong>g to support child feed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>communities? What opportunities exist to support frontl<strong>in</strong>e workers to optimize child feed<strong>in</strong>g?Prior to design<strong>in</strong>g this formative study, A&T conducted a review of the exist<strong>in</strong>g substantial body of<strong>in</strong>formation concern<strong>in</strong>g maternal nutrition, early <strong>in</strong>itiation of breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> exclusive breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> Ethiopia. Formative research, <strong>in</strong> the form of focus group discussions under the LINKAGES Project,provided additional <strong>in</strong>formation on child feed<strong>in</strong>g practices that led to the development of EssentialNutrition Actions (ENA).Much of the exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation from the literature review focused on the <strong>in</strong>itiation of breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong> complementary feed<strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>in</strong> a general sense. More detailed <strong>in</strong>formation was thus needed tofully underst<strong>and</strong> the issues of <strong>IYCF</strong> practices <strong>in</strong> the project areas, <strong>and</strong> to identify barriers, facilitators,people, <strong>and</strong> approaches that can <strong>in</strong>fluence change. The f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from the formative research willcontribute to the design of effective strategies for improv<strong>in</strong>g breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>, especially,complementary feed<strong>in</strong>g practices for young children. F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs highlight the potential role of health <strong>and</strong>community workers to support this behavior change, contribut<strong>in</strong>g to efforts to reduce stunt<strong>in</strong>g amongyoung children <strong>in</strong> Ethiopia.Key F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsThe <strong>SNNP</strong> formative research on <strong>in</strong>fant <strong>and</strong> young child feed<strong>in</strong>g identified the beliefs <strong>and</strong> currentfeed<strong>in</strong>g practices for breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> complementary feed<strong>in</strong>g of children, along with key facilitat<strong>in</strong>gfactors to improve young child feed<strong>in</strong>g. The study also assessed the roles of different groups, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gfamily <strong>and</strong> community members, health extension workers, <strong>and</strong> voluntary community health promoters<strong>in</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>IYCF</strong> <strong>in</strong> their communities.<strong>IYCF</strong> practices <strong>and</strong> related beliefs <strong>and</strong> attitudes. This study <strong>in</strong>dicates that breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g is widelypracticed <strong>in</strong> the research communities <strong>and</strong> is expected of all mothers <strong>and</strong> valued <strong>in</strong> the community for its1

contribution towards child growth <strong>and</strong> healthy development. Unlike the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> related studies,mothers <strong>in</strong> the study areas seem to know the expected breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g requirements such as: on-dem<strong>and</strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g, frequency of breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> the need to feed from both breasts. Yet exclusive breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g isnot widely practiced <strong>in</strong> the study communities. Mothers commonly <strong>in</strong>troduce water, fenugreek, orl<strong>in</strong>seed water as early as 2 months. Mothers also use bottle feed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> consider this a good practice forfeed<strong>in</strong>g the child th<strong>in</strong> gruel, because the bottles are believed to keep the food covered <strong>and</strong> clean.This study demonstrates that mothers <strong>and</strong> other family <strong>and</strong> community members are concerned thatfeed<strong>in</strong>g a sick child extra food will cause further illness, diarrhea, <strong>and</strong> vomit<strong>in</strong>g, or that it wouldstimulate the child’s appetite <strong>and</strong> develop a habit for eat<strong>in</strong>g more food than the family can afford.In regards to complementary foods, the study <strong>in</strong>dicates that the age for <strong>in</strong>troduction of additional foodsranges from 2 months to 8 months, with a majority of mothers report<strong>in</strong>g that they had started giv<strong>in</strong>gfoods at 6 months or earlier. Certa<strong>in</strong> foods such as kale, enichila, banana, egg, pumpk<strong>in</strong>, carrot, <strong>and</strong>green vegetables are considered unsuitable <strong>and</strong> “too strong” for young children to digest before 1 yearof age. Meat, <strong>in</strong> particular, is considered by mothers as too hard to digest. Most mothers recommendmeat for children above 1 or 2 years old. Mothers also expressed that they need to have a good <strong>in</strong>cometo buy or feed their children such foods.Regardless of this, study participants believe that children <strong>in</strong> their communities are do<strong>in</strong>g well due toimmunization services, improved access to health services, <strong>and</strong> improved child feed<strong>in</strong>g practices.Community <strong>and</strong> family <strong>in</strong>fluences on mothers’ feed<strong>in</strong>g practices. The role of family members <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>IYCF</strong> practices was also explored. Mothers are seen as the primary caregivers for children<strong>in</strong> the home, sometimes assisted by an elder daughter, mother, or mother-<strong>in</strong>-law. Husb<strong>and</strong>s appear to<strong>in</strong>fluence child feed<strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>in</strong>directly, primarily <strong>in</strong> their role as provider <strong>and</strong> as the one whocontrols family f<strong>in</strong>ances. Family members’ <strong>and</strong> community elders’ advice on feed<strong>in</strong>g is often followed,even though traditional practices sometimes run counter to the MOH recommended <strong>IYCF</strong> practices.HEW <strong>and</strong> VCHP capacities. This study looked at perceptions of staff <strong>and</strong> volunteer capacity from theirown po<strong>in</strong>t of view <strong>and</strong> from the po<strong>in</strong>t of view of the families they serve. Capacity <strong>in</strong>cludes bothknowledge of recommended <strong>IYCF</strong> practices <strong>and</strong> the skills needed to teach, tra<strong>in</strong> or counsel.The study confirmed that the HEP system is well established, with tra<strong>in</strong>ed HEWs implement<strong>in</strong>g manyof the 16 key HEP packages. As a result, the HEW supervisors <strong>and</strong> HEWs believe that the overallhealth situation is improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> communities, <strong>and</strong> that morbidity <strong>and</strong> mortality have decreased. On theother h<strong>and</strong>, the potential burden of new <strong>in</strong>itiatives on HEWs <strong>and</strong> VCHPs <strong>in</strong> terms of compet<strong>in</strong>gpriorities <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong>s on their time was <strong>in</strong>dicated as a challenge.Accord<strong>in</strong>g to study participants, HEWs <strong>and</strong> VCHPs are well-known <strong>and</strong> active <strong>in</strong> the studycommunities. All of the HEWs have completed the 1-year HEW basic tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g program. They reportedthat they visit 40 or 50 households a week <strong>and</strong> also supervise 10 to 20 VCHPs.Regard<strong>in</strong>g BCC materials used <strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>IYCF</strong>, two previous USAID-funded projects, EssentialServices for Health <strong>in</strong> Ethiopia (ESHE) <strong>and</strong> LINKAGES, have distributed these materials to area2

communities as well as the guidel<strong>in</strong>es for the community-based nutrition approach. Additionalmaterials the HEWs receive through the Woreda Health Office <strong>in</strong>clude: the family health card <strong>and</strong> twotypes of posters, one with pictures of a well-nourished child <strong>and</strong> a child with malnutrition, <strong>and</strong> anotherwith the feed<strong>in</strong>g guidel<strong>in</strong>es. Some of the HEWs say they are us<strong>in</strong>g the counsel<strong>in</strong>g cards. The HEWs saythey f<strong>in</strong>d the family health card very useful <strong>in</strong> work<strong>in</strong>g with mothers <strong>and</strong> the posters are popular forwork<strong>in</strong>g with community groups.The study also revealed that HEWs feel they have a need to learn more about child feed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> order toeffectively counsel mothers on <strong>IYCF</strong>. Several po<strong>in</strong>ted out that they need more detailed <strong>in</strong>formationabout additional foods, types of foods, <strong>and</strong> best approaches for prepar<strong>in</strong>g food for young children, withfollow-up mechanism.Besides the HEWs, the role of the VCHPs was also identified. The VCHPs work more <strong>in</strong> sanitation <strong>and</strong>hygiene <strong>and</strong> family plann<strong>in</strong>g than <strong>in</strong> <strong>IYCF</strong>. Though not formally tra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> nutrition, many of theseVCHPs spoke of provid<strong>in</strong>g basic advice on child feed<strong>in</strong>g to families dur<strong>in</strong>g home visits, especially aboutbreastfeed<strong>in</strong>g. Most said they learned about child feed<strong>in</strong>g by read<strong>in</strong>g the family health card, which theybelieve is the most important resource for their job. Similar to the HEWs, the VCHPs suggested theneed for tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> giv<strong>in</strong>g consistent messages <strong>and</strong> feed<strong>in</strong>g recommendations to avoid <strong>IYCF</strong>misconceptions <strong>and</strong> to promote optimum <strong>IYCF</strong> practices <strong>in</strong> the community.3

1. BackgroundIn Ethiopia, A&T’s goal is to reduce death, illness, <strong>and</strong> malnutrition caused by sub-optimal feed<strong>in</strong>g of<strong>in</strong>fants <strong>and</strong> young children:• Increase exclusive breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g by 25 percent (from 49 percent to 61 percent) among <strong>in</strong>fants 0-5 months old• Prevent stunt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 353,000 childrenThe aim is to design, implement, <strong>and</strong> test strategies which can have a substantive impact oncomplementary feed<strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>and</strong> that can readily be adapted <strong>and</strong> scaled up all over the project area.To achieve coverage at scale, A&T is partner<strong>in</strong>g with Integrated Family Health Project (IFHP), WorldVision, <strong>and</strong> other organizations that support the Government of Ethiopia delivery system to effectchanges <strong>in</strong> <strong>IYCF</strong> through three ma<strong>in</strong> strategies: improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>IYCF</strong> policy <strong>and</strong> regulatory environments,shap<strong>in</strong>g <strong>IYCF</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> practice (community-based approaches), <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g supply, dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong>us of fortified complementary foods <strong>and</strong> related products.One of the major platforms for program implementation to shape <strong>IYCF</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> practice is throughexist<strong>in</strong>g programs which address community-based nutrition. The strategy is to support <strong>and</strong>strengthen the government’s community-based Health Extension Program which utilizes HEWs <strong>and</strong>VCHPs to mobilize their communities, deliver key preventive messages, <strong>and</strong> provide counsel<strong>in</strong>g topromote optimal <strong>IYCF</strong> behaviors. A key question which A&T seeks to answer through this approach isthe level of improvement <strong>in</strong> <strong>IYCF</strong> that can be achieved at scale, largely through the government’shealth program us<strong>in</strong>g the health extension workers to catalyze change.The Federal M<strong>in</strong>istry of Health <strong>in</strong> Ethiopia has made significant progress <strong>in</strong> support of <strong>IYCF</strong> <strong>in</strong> the lastdecade. A National Strategy for Infant <strong>and</strong> Young Child Feed<strong>in</strong>g was developed <strong>in</strong> 2004 which providesdetailed feed<strong>in</strong>g recommendations <strong>and</strong> guidel<strong>in</strong>es. A National Nutrition Strategy was developed <strong>in</strong>2005-06, <strong>and</strong> a National Nutrition Program for implement<strong>in</strong>g this strategy on a national scale was<strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> July 2008.In 2005, under the USAID bilateral project <strong>and</strong> AED’s LINKAGES project, key messages on theessential nutrition actions to improve the nutrition of women <strong>and</strong> young children <strong>in</strong> Ethiopia weredeveloped <strong>and</strong> dissem<strong>in</strong>ated. Us<strong>in</strong>g the favorable policy environment created, considerable work wasdone <strong>in</strong> the area of <strong>IYCF</strong> by government <strong>and</strong> nongovernmental organizations. <strong>Alive</strong> & <strong>Thrive</strong> isbuild<strong>in</strong>g on these efforts.2. Rationale, Objectives <strong>and</strong> Research QuestionsEthiopia is a large country with diverse cultures reflected by different food habits <strong>and</strong> traditionalpractices. To ensure that program strategies are effective <strong>in</strong> a diverse culture, <strong>in</strong>formation is needed tobetter underst<strong>and</strong> various <strong>IYCF</strong> practices at community <strong>and</strong> household levels as well as the factorswhich <strong>in</strong>fluence child feed<strong>in</strong>g practices. Further research was needed to fully underst<strong>and</strong> the <strong>IYCF</strong>4

practices <strong>and</strong> the barriers, facilitators, people, <strong>and</strong> approaches that can <strong>in</strong>fluence change for optimal<strong>IYCF</strong> practices. A&T offers an opportunity to exp<strong>and</strong> on earlier <strong>IYCF</strong> work <strong>and</strong> to focus on childrenunder 2 years of age towards prevent<strong>in</strong>g malnutrition. To reduce stunt<strong>in</strong>g, A&T focuses on improvedcomplementary feed<strong>in</strong>g. The research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs will be used to support effective strategies for improv<strong>in</strong>gcomplementary feed<strong>in</strong>g practices.2.1 Objectives of the formative researchThe general objective of the study is to underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant <strong>and</strong> young child feed<strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>and</strong> the roleof service providers <strong>in</strong> the study communities. Specific objectives are:• To describe current <strong>IYCF</strong> practices• To identify barriers <strong>and</strong> facilitators for recommended <strong>IYCF</strong> practices• To identify people <strong>and</strong> approaches that can <strong>in</strong>fluence optimal <strong>IYCF</strong> change• To explore strategies for improv<strong>in</strong>g complementary feed<strong>in</strong>g practices for young children• To explore the potential role of health <strong>and</strong> community workers to support <strong>IYCF</strong> behaviorchanges <strong>and</strong> thus reduce stunt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> young children2.2 Research questionsThe follow<strong>in</strong>g research questions were formulated to identify the gaps <strong>in</strong> <strong>IYCF</strong>, especially oncomplementary feed<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong> the study communities:a) What are the beliefs <strong>and</strong> current practices for breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> complementary feed<strong>in</strong>g ofchildren <strong>in</strong> the study communities?b) What key factors <strong>in</strong>fluence mothers <strong>and</strong> family members to adopt recommended <strong>IYCF</strong>practices?c) Who <strong>in</strong>fluences mothers? What is the current role of family <strong>and</strong> community members tosupport optimal <strong>in</strong>fant <strong>and</strong> child feed<strong>in</strong>g practices?d) What is the current role of health extension workers (HEWs) <strong>and</strong> other health providers tosupport optimal <strong>in</strong>fant <strong>and</strong> child feed<strong>in</strong>g practices?e) What is Health Extension Program currently do<strong>in</strong>g to support child feed<strong>in</strong>gcommunities? What opportunities exist to support frontl<strong>in</strong>e workers to optimize child feed<strong>in</strong>g?3. Methodology3.1 Study areaThe formative research was conducted <strong>in</strong> three zones of <strong>SNNP</strong> Region: Gamgofa, Hadiya <strong>and</strong> Dawiro.Research communities were selected from three woredas which were selected from the three zones,<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>cludes Mareka, Misha <strong>and</strong> Chenicha. The three locations were chosen to capture differences<strong>in</strong> breast feed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> complementary feed<strong>in</strong>g practices with<strong>in</strong> the region.5

3.2 Sampl<strong>in</strong>g techniquesSite Selection: Communities were purposefully selected by the A&T program team to capture vary<strong>in</strong>gfactors, such as staple food, access to market, women’s employment patterns, <strong>and</strong> tribal <strong>and</strong> languagecomposition. All of the study areas are currently served by a government health extension program <strong>and</strong>are with<strong>in</strong> the current IFHP program areas.Selection of Respondents: Prior to any data collection, discussions held at Woreda Health Officesassisted the program team <strong>in</strong> ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g permission to enter sample communities. Respondents werer<strong>and</strong>omly selected <strong>in</strong> each area from a list provided by the health post, <strong>and</strong> the study <strong>in</strong>terviewers alsowent door to door to identify households with children <strong>in</strong> the required age group. S<strong>in</strong>ce there was nobetter method to get a list of children under 2 years of age <strong>in</strong> selected communities, the health postimmunization registry book was used to select participants. Selection was based on the age of the child<strong>and</strong> the will<strong>in</strong>gness of the family to be observed.Maternal <strong>in</strong>terviews <strong>and</strong> observations: Household visits were conducted when the majority ofresidents were expected to be home. Observations were also conducted <strong>in</strong> the same households wheremothers of the eligible children were <strong>in</strong>terviewed.Focus group discussions: Focus group discussions (FGDs) were held with fathers <strong>and</strong> gr<strong>and</strong>mothersor mothers-<strong>in</strong>-law. Respondents for focus groups were selected from the same village where the women<strong>in</strong>terviewees were resid<strong>in</strong>g. Only one member of the household was selected, <strong>in</strong> order to avoid mutual<strong>in</strong>fluences <strong>in</strong> the responses. Focus group discussions were also held with village leaders <strong>and</strong> women’sgroup leaders. These participants were identified by village leadership <strong>and</strong> HEWs.Interviews with service providers: Interviews were also conducted with HEWs <strong>and</strong> VCHPs, as theyare the <strong>in</strong>dividuals provid<strong>in</strong>g advice to mothers on child feed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> treatment of illness. The twoHEWs serv<strong>in</strong>g each of the respective study communities were <strong>in</strong>terviewed; <strong>in</strong> addition three moreHEWs were <strong>in</strong>terviewed from neighbor<strong>in</strong>g communities. (In one site, an additional two were<strong>in</strong>terviewed.) Discussions were conducted at the Woreda Health Office, which also assisted the programteam <strong>in</strong> ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g permission to enter sample communities. HEW supervisors support<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>terviewedHEWs were also identified <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terviewed. The overall study design used for this formative research ispresented <strong>in</strong> Table 1.3.3 Data gather<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>strumentsThe mothers’ questionnaire <strong>and</strong> observation guide were adapted from the ProPan Manual: Process for thePromotion of Child Feed<strong>in</strong>g 1 , developed by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Focus groupguides had been adapted from formative research previously conducted <strong>in</strong> several countries under theLINKAGES Project.1 Pan American Health Organization (April 2004). ProPan Manual: Process for the Promotion of Child Feed<strong>in</strong>g.6

Table 1. Study participants <strong>and</strong> data collection methods, <strong>SNNP</strong> formative researchRespondent Method Number per site TotalMothers with children 6 to 23 months old-with children 6-8 months-with children 9-11 months-with children 12-23 monthsMaternal Observations-with child 6-23 monthsFathers with children 6 to 18 months oldGr<strong>and</strong>mothers of children 6 to 18 monthsoldWomen’s leaders <strong>and</strong> community healthcommittee membersVoluntary community health promotersHealth extension workersHealth extension worker supervisorSemi-structured<strong>in</strong>terviewObservation toolFocus groupdiscussionFocus groupdiscussionFocus GroupdiscussionSemi-structured<strong>in</strong>terviewSemi-structured<strong>in</strong>terviewSemi-structured<strong>in</strong>terview15-1747555 +2 <strong>in</strong> Mareka112-41 31 31 32 65 152 63.4 Data collectionOne team of eight <strong>in</strong>terviewers was established with four responsible for focus group discussions, onefor <strong>in</strong>terviews with health personnel, <strong>and</strong> the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for <strong>in</strong>terviews with mothers. Three <strong>in</strong>dividualswere selected from those who were do<strong>in</strong>g the mother <strong>in</strong>terviews <strong>and</strong> assigned for opportunisticobservations.The data collection process took seven days per site, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g transportation to the study sites <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>itial visits to obta<strong>in</strong> the necessary permissions to enter the community. Partners <strong>in</strong> the study sitesfacilitated the field work by identify<strong>in</strong>g study participants. Experts from ACIPH, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g two fieldsupervisors, stayed on the field for the whole duration of data collection to ensure accuracy <strong>and</strong>completeness.3.5 Data quality assuranceTo assure the quality of data collected, the follow<strong>in</strong>g steps were taken:• The data collection <strong>in</strong>struments were adapted from previous studies• Data collectors were tra<strong>in</strong>ed with the data gather<strong>in</strong>g protocol7

• Even<strong>in</strong>g discussions were held to identify the key f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs, challenges, <strong>and</strong> other issues raisedby the <strong>in</strong>terviewers.• A summary matrix was developed <strong>in</strong> advance <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terviewers completed this matrix foreach <strong>in</strong>terview with mothers to summarize <strong>and</strong> discuss f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs with supervisors.3.6 Ethical considerationsEthical approval was received from Addis Cont<strong>in</strong>ental Institute of Public Health’s Institutional ReviewBoard (ACIPH IRB) 2 . Permission to undertake the survey was obta<strong>in</strong>ed from the study sites <strong>and</strong> woredaauthorities. Informed consent was obta<strong>in</strong>ed from the study participants after expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the purpose ofthe study. Participation of all respondents <strong>in</strong> the study was on a voluntary basis <strong>and</strong> emphasis was givento assure the respect, dignity, confidentiality, <strong>and</strong> freedom of each participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong> the study.Interviewers were also tra<strong>in</strong>ed on the importance of obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formed consent <strong>and</strong> avoid<strong>in</strong>g coercionof any k<strong>in</strong>d.3.7 Data process<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> write-upData from FGDs was transcribed <strong>in</strong> the language of the <strong>in</strong>terview <strong>and</strong> then translated <strong>in</strong>to English foranalysis. Notes from <strong>in</strong>-depth <strong>in</strong>terviews were the ma<strong>in</strong> data for analysis of important <strong>and</strong> commonconcepts related to the ma<strong>in</strong> themes of the study. Data analysis was done ma<strong>in</strong>ly based on the<strong>in</strong>terpretative approach that <strong>in</strong>volves elicit<strong>in</strong>g mean<strong>in</strong>gs from the collected <strong>in</strong>formation. “Open Code”Computer program was used for sort<strong>in</strong>g transcribed <strong>in</strong>formation, look<strong>in</strong>g for patterns, similarities,differences or contradictions.2 Addis Cont<strong>in</strong>ental Institute of Public Health has an <strong>in</strong>dependent Ethical Review Board which is approved by the NationalEthical Committee.8

4. F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs4.1 What are beliefs <strong>and</strong> current practices for complementary feed<strong>in</strong>g of children?Breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> complementary feed<strong>in</strong>g practicesBreastfeed<strong>in</strong>g is widely practiced <strong>in</strong> the research communities <strong>and</strong> is expected of all mothers. Thispractice appears to be valued <strong>in</strong> the community, with respondents <strong>in</strong> all three locations express<strong>in</strong>g thedesirability for a mother to breastfeed, expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g that a breastfed child grows up to be a strong <strong>and</strong>healthy child. Mothers said that breastmilk gives energy <strong>and</strong> hastens growth, satisfies the child, <strong>and</strong>can protect aga<strong>in</strong>st disease. When asked about practices <strong>in</strong> their communities, most HEWs <strong>and</strong> VCHPsmentioned breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g, particularly their success <strong>in</strong> conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g some mothers to exclusivelybreastfeed.Breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g frequency <strong>and</strong> on dem<strong>and</strong>. All mothers except two were breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g at the time ofthe study, <strong>and</strong> mothers <strong>in</strong> all communities reported that they breastfeed frequently <strong>and</strong> on dem<strong>and</strong>, bothdur<strong>in</strong>g the day <strong>and</strong> at night. It was difficult for some mothers to quantify how many times theybreastfeed dur<strong>in</strong>g the day <strong>and</strong> night, although when pressed, around half said they breastfed eight to tentimes, even up to 13 times <strong>in</strong> the previous 24-hour period which <strong>in</strong>cluded two to four times at night.Some mothers reported that they breastfed only three to seven times <strong>in</strong> the previous 24-hour period,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g one who stressed that she can breastfeed only when she stays at home.Women tend to breastfeed from both breasts, with many mention<strong>in</strong>g that they empty one breast beforeswitch<strong>in</strong>g to the other. Many mothers expla<strong>in</strong>ed their own way of know<strong>in</strong>g when one breast is empty<strong>and</strong> when it is time to change to the other, while some mothers rely on cues from the child such aspush<strong>in</strong>g away or cry<strong>in</strong>g before switch<strong>in</strong>g breasts. A few mothers expressed concerns about feed<strong>in</strong>g onlyfrom one breast, such as the breast becom<strong>in</strong>g pa<strong>in</strong>ful or the unused milk <strong>in</strong> the breast not be<strong>in</strong>g healthyif left overnight. Several mothers stressed that it was necessary to feed from both breasts to fullysatisfy the child. Two mothers mentioned that one breast conta<strong>in</strong>s water <strong>and</strong> the other conta<strong>in</strong>s food,with one of these say<strong>in</strong>g that she learned this from the HEW. Almost all mothers stressed that anadequate <strong>and</strong> varied diet is important <strong>in</strong> produc<strong>in</strong>g enough breastmilk for her child. Some mentionedthat it is also important that the mother is <strong>in</strong> good health. One mother cautioned that if the child is notfed from both breasts, the unused breast will stop produc<strong>in</strong>g milk. No one else mentioned a l<strong>in</strong>k betweenthe frequency of breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> the production of breastmilk.Duration of breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g. Of the mothers <strong>in</strong>terviewed, only two women (with children 14 <strong>and</strong> 22months old) had stopped breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g. One stopped because she was pregnant <strong>and</strong> the other becauseshe started on <strong>in</strong>jectable contraceptives <strong>and</strong> was “busy with harvest.” Most of the mothers said theyplanned to cont<strong>in</strong>ue breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g until the child is 2 or 3 years old <strong>and</strong> some said even up to age 5 or 6years. Many of the women plan to stop breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g either when the child is old enough to eat on hisor her own (around 3 years old) or when they become pregnant aga<strong>in</strong>. Some mothers fear thatbreastfeed<strong>in</strong>g a child for more than two years is not good for the mother’s health. Several mothersstressed that they want to avoid pregnancy <strong>and</strong> that they believe that breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g to 2 or 3 years is9

important for protection. A few mothers admitted that they cont<strong>in</strong>ue to breastfeed because they can notafford or do not have access to additional food for their child.Many mothers <strong>and</strong> community members view breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g up to 2 years <strong>and</strong> beyond as feasible whilemany also stressed that cont<strong>in</strong>ued breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g is important <strong>in</strong> ensur<strong>in</strong>g that their children are healthy<strong>and</strong> protected from illnesses. Several mothers noticed that children who were breastfed for only a yearwere sick <strong>and</strong> weak, <strong>and</strong> not as strong as children who were breastfed for 2 years.“I will cont<strong>in</strong>ue breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g for 2 years so that it will prevent pregnancy, make the babystrong <strong>and</strong> walk on her feet quickly <strong>and</strong> become fat. My first baby was breastfed for one<strong>and</strong> half years <strong>and</strong> she is sick <strong>and</strong> weak. My friend’s baby who was breastfed for 2 years isstronger than m<strong>in</strong>e.” -A mother <strong>in</strong> ChenichaSome mothers stated that they had been advised by the HEWs to breastfeed their child up to the age of2 years, with one mother say<strong>in</strong>g that she plans to cont<strong>in</strong>ue breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g her child for 2 years becausethe HEW had warned her that stopp<strong>in</strong>g before this time would lead to decreased th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>gcapacity for her child.Exclusive breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g. While some mothers <strong>in</strong> all three communities give milk <strong>and</strong> noth<strong>in</strong>g else totheir children for the first 6 months, this is not widely practiced. Mothers as well as fathers <strong>and</strong>gr<strong>and</strong>mothers <strong>in</strong> all three locales confirmed that the <strong>in</strong>troduction of water, milk, th<strong>in</strong> gruels <strong>and</strong> otherfoods at 3 or 4 months is the customary practice. However, many mothers are aware of therecommendation to breastfeed exclusively, mention<strong>in</strong>g that HEWs rout<strong>in</strong>ely advise mothers to giveonly breastmilk <strong>and</strong> noth<strong>in</strong>g else for the first 6 months. One mother heard this from her antenatal care(ANC) nurse at the local hospital <strong>and</strong> was conv<strong>in</strong>ced to try it.Most of the mothers who said they are giv<strong>in</strong>g only breastmilk stated that they do so because of advicefrom a HEW. Several of these mothers said they had been told that breastmilk conta<strong>in</strong>s all the food ababy needs, or that a baby is too young <strong>and</strong> its stomach <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>es are not yet strong enough todigest food. Mothers also said that “the stomach will be clean,” that breastmilk is light <strong>and</strong> digestible<strong>and</strong> that it will not cause diarrhea or abdom<strong>in</strong>al pa<strong>in</strong>. One mother po<strong>in</strong>ted out that she has enoughbreastmilk to breastfeed exclusively, <strong>and</strong> another said that she does not have enough additional food tofeed her child anyway. Some mothers mentioned that they are conv<strong>in</strong>ced that breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g exclusivelycontributes to the health of their children.Mothers who do not exclusively breastfeed <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduce water <strong>and</strong> foods early do so for a variety ofreasons. Many cited community traditions <strong>and</strong> advice from their mothers, gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, mothers-<strong>in</strong>law,<strong>and</strong> village elders. Many respondents said that breastmilk is not enough to susta<strong>in</strong> a child for thefirst 6 months. Some mothers voiced concerns about exclusive breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g, say<strong>in</strong>g that giv<strong>in</strong>g onlybreastmilk would hurt both the mother <strong>and</strong> the child, or that the child would be hungry <strong>and</strong> cry withoutother fluids or foods. A gr<strong>and</strong>mother advised giv<strong>in</strong>g food because she believes giv<strong>in</strong>g breastmilk alonewill cause constipation. One mother is concerned about constipation as well as the local tradition ofburn<strong>in</strong>g the child’s stomach to relieve constipation. Others said that giv<strong>in</strong>g water <strong>and</strong> other foods <strong>and</strong>liquids does not cause any harm. A mother from Mareka said “even if I learned from HEWs that mothersshould give only breastmilk for 6 months, I believe that my breastmilk wouldn’t be enough for the baby so I gave my10

aby th<strong>in</strong> gruel prepared from millet, teff, macaroni, <strong>and</strong> barley at the age of 3 months <strong>in</strong> order to prevent the babyfrom becom<strong>in</strong>g ill <strong>and</strong> make her fat.” Another mother from Misha said, “Giv<strong>in</strong>g only breastmilk hurts themother as well as the child. The child will be hungry, weak <strong>and</strong> sick.”Mothers commonly <strong>in</strong>troduce water, fenugreek or l<strong>in</strong>seed water early at around 2 months <strong>and</strong>sometimes earlier. Some mothers are concerned that their baby needs water or liquids to quench his orher thirst. Other mothers said that water is needed to dilute breastmilk because it is not easily digested,too salty, or might cause stomach cramps. Mothers reported that elders recommend giv<strong>in</strong>g boiledwater to children. Giv<strong>in</strong>g fenugreek or l<strong>in</strong>seed water to young children was recommended to avoidabdom<strong>in</strong>al cramps, prevent diarrhea <strong>and</strong> other illnesses, or when breastmilk is <strong>in</strong>sufficient. Fenugreekwater is believed to help a child grow healthy <strong>and</strong> strong, <strong>and</strong> to be good for the sk<strong>in</strong>.Cow’s milk is commonly given to children start<strong>in</strong>g around 3 months or sometimes earlier, especiallywhen it is readily available <strong>in</strong> the home. Mothers who give cow’s milk said that breastmilk alone is notenough, especially for a 4- to 6- month- old child. One mother said that her child needs cow’s milkbetween breastfeeds to obta<strong>in</strong> enough energy, <strong>and</strong> another observed that children that dr<strong>in</strong>k cow’s milkgrow bigger <strong>and</strong> stronger than those who dr<strong>in</strong>k only breastmilk. A mother with tw<strong>in</strong>s said that hermother-<strong>in</strong>-law told her that her breastmilk is <strong>in</strong>sufficient for two babies <strong>and</strong> that additional milk isneeded. Mothers reported that their mothers, mothers-<strong>in</strong>-law <strong>and</strong> village elders encourage the giv<strong>in</strong>g ofmilk, boiled milk with butter, or home-made yogurt to the child. Milk is seen as important <strong>in</strong> ensur<strong>in</strong>gthat a child grows strong <strong>and</strong> fat, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fight<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>st illness.When asked what advice they would give to a mother with a 4- to 6- month-old child, all of the VCHPs<strong>and</strong> all but one of the HEWs re<strong>in</strong>forced the message of exclusive breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g. Nonetheless, severalmothers stated that food should be <strong>in</strong>troduced at 4 to 6 months, a message promoted as recently as2003, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the orig<strong>in</strong>al HEW tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g curriculum. One HEW said that <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g cow’smilk is needed to provide additional food for the child, <strong>and</strong> one mother spoke of a community healthagent (who served before the HEW) who advised start<strong>in</strong>g milk <strong>and</strong> food before 6 months. HEWsupervisors said milk is a common first food for <strong>in</strong>fants, with one supervisor say<strong>in</strong>g specifically that headvises giv<strong>in</strong>g one part milk with three parts water as a first food. However, from what mothers said,most health workers are now unified <strong>in</strong> support of exclusive breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g. In one case, a motherreported that she had been giv<strong>in</strong>g cow’s milk to her child, but that a nurse encouraged her to dr<strong>in</strong>k themilk herself <strong>and</strong> give only breastmilk to her child.Timely <strong>in</strong>troduction of first foods. The age for <strong>in</strong>troduction of additional foods ranged from 2 monthsto 8 months with a majority of mothers report<strong>in</strong>g that they had started giv<strong>in</strong>g foods at 6 months orbefore. Focus group discussions with other community members had similar f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs. A tendency to<strong>in</strong>troduce foods early was reported <strong>in</strong> Mareka, where a couple of mothers said they started with fruit at2 months, <strong>and</strong> others said they started with gra<strong>in</strong>-based gruels at 3 to 5 months. One gr<strong>and</strong>mother saidthat food is normally <strong>in</strong>troduced as early as 15 days. The primary reason given for <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g foodearly is the concern that breastmilk is not enough for the child, <strong>and</strong> that additional foods are needed toavoid hunger <strong>and</strong> ensure good growth <strong>and</strong> strength.In Misha <strong>and</strong> Chenicha, many mothers said they started foods around 6 months, though some motherswith children age 6 <strong>and</strong> 7 months they were still exclusively breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g at the time of the study.11

Other mothers <strong>in</strong> these areas with older children admitted that they did not start to give gruels or foodother than liquid milk to their child until the ages of 7 to 9 months. This was also mentioned by agr<strong>and</strong>mother, <strong>and</strong> two mothers admitted not giv<strong>in</strong>g porridge or gruel until age 1 year. One mother of a6-month-old plans to wait until her child is 7 months old <strong>and</strong> food is available from the harvest formak<strong>in</strong>g gruel, <strong>and</strong> another mother <strong>in</strong> Chenicha plans to wait to feed her child additional food until afterthe first year because she is afraid that “foods given to the child will br<strong>in</strong>g illness to the child’s stomach.” Shealso said she has “no money to buy cereal,” <strong>and</strong> that she would have to arrange with neighbors or borrowmoney for food.Many mothers <strong>and</strong> focus group participants (fathers, gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, <strong>and</strong> community leaders) stated thatthe <strong>in</strong>formation from HEWs has made them change their feed<strong>in</strong>g practices. Mothers noted that theearly <strong>in</strong>troduction of foods was previously the accepted practice <strong>and</strong> that HEW’s advice on exclusivebreastfeed<strong>in</strong>g is chang<strong>in</strong>g this practice.“Sometime ago, I believed that giv<strong>in</strong>g other foods before 6 months was good. I used tostart giv<strong>in</strong>g food to the child at the second <strong>and</strong> third month. But now I have beeneducated <strong>and</strong> changed this practice. I was told by HEWs that the child will be sick if I giveanyth<strong>in</strong>g before 6 months, but I chose to give fenugreek s<strong>in</strong>ce it will make the child ga<strong>in</strong>weight <strong>and</strong> it may not cause abdom<strong>in</strong>al pa<strong>in</strong> like other cereals.” -A mother <strong>in</strong> Chenicha“Giv<strong>in</strong>g additional food at 6 months makes the child healthy, <strong>and</strong> this habit came from theelders.” -A mother <strong>in</strong> MarekaAppropriate first foods. In all three areas, porridge <strong>and</strong> gruel were typically the first foods given tochildren, with some mothers also mention<strong>in</strong>g mashed fruit, such as banana, papaya, avocado <strong>and</strong> orange.Focus group participants (gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, fathers, <strong>and</strong> community leaders) agreed that gruel <strong>and</strong>porridge are often given, as are fruits. They mentioned that besso (porridge <strong>and</strong> gruel with a consistencyof mashed banana), kocho (false banana), atekana (prepared from fenugreek, bulla, milk <strong>and</strong> butter), <strong>and</strong>bread are also given <strong>and</strong> as a first food.Mothers listed many foods that are good for children, with gruel <strong>and</strong> porridge prepared from a varietyof cereals mentioned as the best foods, across the three study sites. Almost all mothers suggested thatgruel <strong>and</strong> porridge be prepared from at least two types of cereals, say<strong>in</strong>g that these foods will facilitatethe children’s mental <strong>and</strong> physical development <strong>and</strong> will help them grow. A mother <strong>in</strong> Misha had theidea that if children eat these foods, they will be better prepared to learn <strong>and</strong> be successful academically.The benefits of feed<strong>in</strong>g children these foods were described as children “will be healthy <strong>and</strong> strong,”“will be able to start walk<strong>in</strong>g early”<strong>and</strong> “will be energetic <strong>and</strong> will be protected from diseases.”“If children don’t get these foods their bodies will swell <strong>and</strong> they will also lose weight.Children who get these foods will not cry, will be happy <strong>and</strong> be able to start walk<strong>in</strong>g soon.”-A mother <strong>in</strong> Chenicha12

Table 2. Foods suggested by mothers as best for children 6 to 12 months <strong>and</strong> above 12 monthsoldStudyareasChenichaMarekaMishaList of first foods suggested by mothersChildren 6-12 monthsbesso (porridge <strong>and</strong> gruel with a consistencyof mashed banana)breadcabbagecarrotcow’s milkegggabila (mixture of barley flour <strong>and</strong> milk)gruel (from lentil, l<strong>in</strong>seed, barley, peas, beans, <strong>and</strong>maize)kalemangoorangepapayateaavocadobananabean barleyegggruel from sorghum<strong>in</strong>jera (of teff, an iron-rich gra<strong>in</strong>) with shiro (preparedfrom powder of beans or peas with sauce) preparedwith butter, porridge, <strong>and</strong> gruel, <strong>and</strong> mixed withyogurt/milk <strong>and</strong> butter teffmaizemangomilkatekana (prepared from fenugreek, bulla, milk <strong>and</strong>butter)beetrootbread with teabulla (made of false banana, orange, m<strong>and</strong>ar<strong>in</strong>)carrotchiko (made of maize <strong>and</strong> wheat with kale, chicken,gruel from different cereals, eggs, mango, <strong>and</strong>avocado)<strong>in</strong>jera fitfit (made of teff, wheat bread, butter, egg,papaya <strong>and</strong> avocado)kocho (false banana) <strong>and</strong> butterporridge prepared from bulla, barley, sorghum,peas, beans, <strong>and</strong> lentilsporridge or gruel from bulla13Children above 12 monthsapplebesso (made of barley)barleyboiled beanbulla (prepared from the root of false banana)eggenichela (prepared from false banana)k<strong>in</strong>che (barley or wheat, which is crushed <strong>and</strong> boiled)mashed potato, different cereals)kocho (false banana) with teapeasporridge from maizeunleavened bread prepared from kocho, potato,kurikufa (similar to fosse, maize flour is shaped<strong>in</strong>to a small ball <strong>and</strong> boiled with kale or a localleaf called aleko/shifera), <strong>and</strong> kaleavocadobananabread made of maize <strong>and</strong> sorghumgruel made of barley, teff, macaroni, <strong>and</strong> lentil<strong>in</strong>jera (of teff, an iron-rich gra<strong>in</strong>) served with“wet” (stew) of shiro (prepared from powder ofbeans or peas with sauce)kita (unleavened bread) made of teff or falsemilkatekana (prepared from fenugreek, bulla, milk<strong>and</strong> butter)butter <strong>and</strong> milkbread from wheat <strong>and</strong> maizehoneykalek<strong>in</strong>iche (crushed <strong>and</strong> boiled wheat or barley)kocho (false banana)<strong>in</strong>ijera fitfit (made of teff, wheat bread, butter,egg, papaya <strong>and</strong> avocado)meat, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g chickenmeatstew prepared from lentilsthick porridge prepared from bulla, barley,sorghum, peas, beans, <strong>and</strong> lentilsunleavened bread made from kocho <strong>and</strong> maize

Consistency of foods. Children are be<strong>in</strong>g fed various gruels <strong>and</strong> porridges, although observationsshowed that these mixtures are often th<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> liquid. Opportunistic observations showed that childrenare eat<strong>in</strong>g gruels <strong>and</strong> porridges from multiple gra<strong>in</strong>s, milk, <strong>and</strong> chiko (maize flour, kale, fenugreek). Theporridges <strong>and</strong> gruels are typically made from barley <strong>and</strong> rye, with peas, beans or lentils. One motheradded sugar <strong>and</strong> another added butter to the gruel. In two cases of younger children, the gruel wasth<strong>in</strong>ned with breastmilk. Two of the older children were given only kocho softened with milk or godere(a variety of taro/colocasia).Mothers <strong>in</strong> all three areas agreed that special foods need to be prepared separately for young childrenbecause they are too young to digest family food <strong>and</strong> need special food to grow healthy. Thereappeared to be some difficulty differentiat<strong>in</strong>g between semi-solid <strong>and</strong> liquid foods <strong>and</strong> many childrenwere be<strong>in</strong>g fed very th<strong>in</strong> gruels. Though most mothers <strong>in</strong>terviewed said that food with the consistencyof mashed banana should be given to children, dur<strong>in</strong>g observations, gruels were found to be th<strong>in</strong>, withone mother <strong>in</strong> Chenicha prepar<strong>in</strong>g gruel as th<strong>in</strong> as milk. Many mothers said that thick porridge shouldbe given to a 7-month-old child, although some completely disagreed with the idea. The reasons not togive thick porridge were: the porridge is not easily digestible for a child at this age, it is heavy for thisage, <strong>and</strong> the child may choke or have abdom<strong>in</strong>al illness. In all three areas, there were mothers who saidthick foods such as gruel <strong>and</strong> porridge should be given only after the child is 1 year old.“Thick foods stay <strong>in</strong> the child’s stomach for a longer time <strong>and</strong> make the baby fat.” -Amother <strong>in</strong> Chenicha“I would not recommend that a mother give thick porridge to her 7-month-old childbecause this k<strong>in</strong>d of porridge is heavy <strong>and</strong> will not be digested easily at this age. The childalso can’t chew <strong>and</strong> swallow this food. Instead I would advise her to give gruel.” -A mother<strong>in</strong> ChenichaMost mothers talked of prepar<strong>in</strong>g food separately for the child. There was little mention of tak<strong>in</strong>g foodprepared for the family <strong>and</strong> mash<strong>in</strong>g it to make a soft food for the child.Transition to family foods. In addition to feed<strong>in</strong>g young children gruels <strong>and</strong> porridge, mothers saidthat after children are 1 year old, they could eat from family food. Mothers stated that it is notappropriate to give family foods to children younger than 1 year old s<strong>in</strong>ce these children have no teethto chew the foods. Focus group discussion responses varied about the age at which children can startshar<strong>in</strong>g family food. Some <strong>in</strong>formants from Chenicha said the child could be served the family food at 1year or when it starts walk<strong>in</strong>g, while others said 2 to 4 years or even up to 5 or 6 years, <strong>in</strong> Mareka.Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terviews <strong>and</strong> focus group discussions, participants said that a child can share family food whenthey are old enough to sit with family members for a meal. At this po<strong>in</strong>t, the child eats the same food,from the same dish as the family. When asked about family foods that are not good for children, rootcrops were often mentioned; more specifically, godere was commonly mentioned <strong>in</strong> Mareka <strong>and</strong> tseguramd<strong>in</strong>ich (hairy potato) <strong>in</strong> Chenicha.“If a child is above the age of 1 year he can eat family foods like bread prepared frommaize, <strong>and</strong> also godere three times a day. But children younger than 1year old can’t chew<strong>and</strong> swallow thick, hard foods.” -A mother <strong>in</strong> Mareka14

Frequency <strong>and</strong> quantity of feed<strong>in</strong>g. Table 3 compares feed<strong>in</strong>g frequency responses from mothers withthe recommended practice.Table 3. Recommended <strong>and</strong> reported feed<strong>in</strong>g frequencyRecommended feed<strong>in</strong>gfrequency6-8 Months 2-3 meals per day plus 1-2snacks (3-5 times)9-11 Months 3-4 meals per day plus 1-2snacks (4-6 times)12-24 Months 3-4 meals per day plus 1-2snacks (4-6 times)Actual feed<strong>in</strong>g frequency(<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g snacks)Chenicha 1,2,6Mareka 4,4,6,6,6Misha 3,3,5,6Chenicha 2,3,3,5,5Mareka 4,4,5,5,6Misha 2,2,3,4,4Chenicha 3,4,4,5,5Mareka 3,3,4,4,6,6,6Misha 3,4,5,5,6,6Mothers reported that they feed food to their children frequently, rang<strong>in</strong>g from one to six times a day.A significant portion of children are be<strong>in</strong>g fed accord<strong>in</strong>g to the recommended m<strong>in</strong>imum frequencies foreach age group, at least three times for children 6-8 months old, at least four times for children 9-11months old, <strong>and</strong> at least five times for children age 12-24 months. However, some children are be<strong>in</strong>gfed less frequently. In Chenicha, some children aged 6-8 months are be<strong>in</strong>g fed as little as one or twotimes a day. In two of the three woredas, there are some children age 9-11 months who are be<strong>in</strong>g fedjust two or three times a day, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> all areas there are children over 1 year old who are be<strong>in</strong>g fed onlythree times a day.FGD participants confirmed these f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> clarified that this frequency either <strong>in</strong>cludes theadditional snack given between meals or that no snacks are given. Mother respondents expla<strong>in</strong>ed thatgiv<strong>in</strong>g snacks to children is not a common practice. Even if mothers give snacks, the food is typicallythe same as that fed dur<strong>in</strong>g mealtimes.Observations found that all mothers are feed<strong>in</strong>g their children us<strong>in</strong>g a variety of utensils <strong>and</strong> that it isdifficult to estimate the quantity of foods consumed. Children are fed us<strong>in</strong>g bottles filled with gruel,us<strong>in</strong>g cups <strong>and</strong> spoons, or plates <strong>and</strong> bowls, or us<strong>in</strong>g the mother’s h<strong>and</strong>. Children are fed until thequantity f<strong>in</strong>ish the amount of food served, or until they are satisfied or stop eat<strong>in</strong>g. Unconsumed food isset aside for future use. In the observations, two cases were reported where mothers stopped feed<strong>in</strong>gthe child even though the child appeared to want to cont<strong>in</strong>ue. Only one mother mentioned feed<strong>in</strong>g aspecific quantity of food to her child. The mother of a 10-month-old child <strong>in</strong> Misha said that she gave1½ coffee cups of food <strong>in</strong> a day <strong>and</strong> that to give more would be too much <strong>and</strong> would make her child sick.15

In the mother <strong>in</strong>terviews, some mothers who are feed<strong>in</strong>g their children below the recommendedfrequency expressed will<strong>in</strong>gness to <strong>in</strong>crease frequency if told by a health worker to do so. Thesemothers th<strong>in</strong>k that the advice from a health worker is useful <strong>and</strong> a child will be healthy, strong <strong>and</strong>protected from illnesses if food is <strong>in</strong>creased. Some mothers, however, are not will<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>in</strong>crease thefeed<strong>in</strong>g frequency or quantity, even if told to do so by a health worker. Several said that it is difficult toget enough flour or gra<strong>in</strong>s to make the gruel, or that <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g food is not easy because the family haslow <strong>in</strong>come, does not have the gra<strong>in</strong>s available, <strong>and</strong> cannot afford to buy more food. Others areconcerned about over-feed<strong>in</strong>g their child; they are worried that feed<strong>in</strong>g their child more would causesickness, diarrhea, <strong>and</strong> vomit<strong>in</strong>g, or that it would stimulate the child’s appetite <strong>and</strong> develop a habit foreat<strong>in</strong>g more food than the family can afford. Focus group participants <strong>in</strong> Chenicha mentioned repeatedlythat <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the frequency of feed<strong>in</strong>g accord<strong>in</strong>g to the age of the child is difficult <strong>and</strong> not affordablefor many families <strong>in</strong> their area.“I th<strong>in</strong>k giv<strong>in</strong>g the child food three times a day is enough. Giv<strong>in</strong>g the child too much food isa bad habit because if they stay for some time without food, they can’t survive. Too muchfood may also predispose them to illnesses.” -A mother with a child above 12 months ofage <strong>in</strong> Mareka“Increas<strong>in</strong>g the frequency of feed<strong>in</strong>g when the child gets 8 months is not possible.Sometimes feed<strong>in</strong>g a child twice a day is hard because mothers stay outside their home aschildren are gett<strong>in</strong>g older”. - Community leader <strong>in</strong> ChenichaHEWs, however, are conv<strong>in</strong>ced that mothers will feed their children the correct amount <strong>and</strong> frequencyif they have the correct <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>and</strong> advice. However, some of the HEWs <strong>and</strong> VCHPs <strong>in</strong> twolocales were skeptical that families would have enough food to feed the children as required.Food quality <strong>and</strong> diversity. Interviews with mothers suggest that women are widely aware of the needto feed a variety of foods to their child. When asked what they fed their child yesterday, the majority ofmothers talked of feed<strong>in</strong>g gruel or porridge made with two or three types of cereals, with many<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g pulses (various types of lentils, beans <strong>and</strong> peas) <strong>in</strong> the mixture. Mother s also said that theyenhance the gruel by add<strong>in</strong>g other foods, such as milk, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> a few cases, egg <strong>and</strong> pumpk<strong>in</strong>. Other foodmixtures given to young children are shiro wet (a stew prepared from peas or bean powder), atekana(cheese, milk, <strong>and</strong> butter), fosese (maize, kale, potato <strong>and</strong> kocho), kocho softened with milk, as well as<strong>in</strong>ijera, egg, <strong>and</strong> fruits <strong>and</strong> vegetables such as avocado, banana <strong>and</strong> mango. H<strong>and</strong>-held foods such askocho, sugarcane, enichila, boiled potato, godere, <strong>and</strong> bread made of maize are also given but often toolder children.The variety of food actually given to the child, witnessed dur<strong>in</strong>g opportunistic observations, was morelimited. Children are fed with gra<strong>in</strong>-based gruels <strong>and</strong> porridge, milk, <strong>and</strong> chiko (a preparation made frommaize, flour, kale, fenugreek <strong>and</strong> oil). Some of the gruels are made with multiple gra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> gra<strong>in</strong>/pulsemixtures with many <strong>in</strong>gredients.Some mothers believe that kocho is not digestible for children <strong>and</strong> that oil causes constipation. Otherfoods mentioned as unsuitable for younger children are kale, enichila, banana, egg, pumpk<strong>in</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> carrot.Focus group discussion participants expla<strong>in</strong>ed that foods for young children must be soft, chewable, <strong>and</strong>16

digestible. They also expla<strong>in</strong>ed that texture is important <strong>and</strong> that some foods such as kolo (a roastedcereal usually prepared from barley, wheat, maize <strong>and</strong> chickpea), toasted cereals such as barley, kocho <strong>and</strong>unleavened bread are too hard for young children. Some mothers do no give their children soft kocho,boiled godere, <strong>and</strong> sometimes kale, because they believe these foods are too hard to digest that theylikely cause gastro-<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al problems.Many mothers said they add milk, butter, <strong>and</strong> oil to foods because these foods are available <strong>and</strong> theygive children energy <strong>and</strong> help them grow healthy <strong>and</strong> strong. Several mothers have cows so milk isreadily available. Others said they do not have cows <strong>and</strong> access to milk, <strong>and</strong> although they sometimesbuy milk <strong>in</strong> the market, several are concerned that the milk from the market is not good. Many mothers<strong>in</strong> Misha <strong>and</strong> Mareka said that they have fruits <strong>and</strong> vegetables <strong>in</strong> their gardens or near their homes <strong>and</strong>could easily give these. Mothers stressed that fruits are important for the child’s health <strong>and</strong> one motherhad heard from a neighbor that it is good to give avocado, papaya, <strong>and</strong> orange. Another mother wastold dur<strong>in</strong>g her ANC visit that fruits <strong>and</strong> eggs are very important foods for children. Green vegetablesare not often given to children, <strong>and</strong> kale <strong>in</strong> particular was considered by some as unsuitable <strong>and</strong> toostrong for young children to digest. In Misha, mothers only feed cabbage to children over age 2because they are concerned about worms.Pumpk<strong>in</strong> is seen as a possibility <strong>and</strong> is given by a few mothers. One mother remarked that it is easy togive pumpk<strong>in</strong> because it is soft, <strong>and</strong> another had been advised by an HEW that pumpk<strong>in</strong> is good for heryoung child. Another mother, however, said that pumpk<strong>in</strong> is not good for children under age 1, yet shestill feed it to her child s<strong>in</strong>ce that is what she has. Several other mothers also said that a child needs tobe at least 1 year old before foods like pumpk<strong>in</strong>, carrot, <strong>and</strong> egg are appropriate.In all three communities, some mothers are already feed<strong>in</strong>g eggs to children. This is ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong>households where chickens are be<strong>in</strong>g raised. Other mothers po<strong>in</strong>ted out that they have eggs available athome <strong>and</strong> could feed them to their children. There were a few mothers who said that eggs are not safeto give to children under 1 year old because they might make them sick; <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> Mareka, egg wasconsidered suitable only for children above 3 years old. Others expressed will<strong>in</strong>gness to feed eggs ifthese were available, but added that this requires money, <strong>and</strong> that other foods or items would need to besold to buy eggs. In some households, eggs are available but are be<strong>in</strong>g sold so that the family could buygra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> other needed commodities. Eggs were seen by many as a luxury item <strong>and</strong> too expensive tobe given on a daily basis.Flesh foods, such as poultry, meat, <strong>and</strong> fish, are not easily available <strong>and</strong> are rarely given to children.When asked about these foods, most mothers responded that they are not available <strong>in</strong> the home <strong>and</strong> thatthey did not have enough money to buy them. For many, meat is eaten only on holidays or dur<strong>in</strong>gspecial festivals. Mothers also po<strong>in</strong>ted out that poultry, fish, or meat is not commonly given to youngchildren <strong>in</strong> their communities. Children are considered too young to chew <strong>and</strong> digest these foods.Meat, <strong>in</strong> particular, is considered by mothers as too hard to digest <strong>and</strong> is recommended for childrenabove 1 or 2 years old <strong>in</strong> Chenicha <strong>and</strong> Misha, <strong>and</strong> above 5 years old <strong>in</strong> Mareka.“Children start eat<strong>in</strong>g egg after the age of 1 year. It predisposes the child to diarrhea <strong>and</strong>vomit<strong>in</strong>g if given before this age.” -A mother <strong>in</strong> Mareka17

“To feed the child meat, fish, <strong>and</strong> egg I have to get a job <strong>and</strong> earn money. The governmentshould create a job opportunity for me.” -A mother <strong>in</strong> Chenicha“I never feed the child meat because it is not available here. Even if it is available, we don’tgive meat to children below the age of 5 years. If children start to eat meat at an earlierage, they will share with adults <strong>and</strong> want to eat more. We get meat once a year dur<strong>in</strong>g theMesikel holiday.” -A mother <strong>in</strong> ChenichaMost of the HEWs <strong>in</strong> Mareka <strong>and</strong> some <strong>in</strong> Chenicha <strong>and</strong> Misha said that the children <strong>in</strong> theircommunities are not gett<strong>in</strong>g a variety of foods for a number of reasons, the biggest reason be<strong>in</strong>gf<strong>in</strong>ancial constra<strong>in</strong>ts. Families do not have the ability to buy various types of fruits, vegetables <strong>and</strong>cereals, so families just prepare food from what is available at home. HEWs also said that mothers donot have adequate knowledge on child feed<strong>in</strong>g practices.“I don’t th<strong>in</strong>k children <strong>in</strong> this community are gett<strong>in</strong>g enough food, because foods like egg,banana, mango, avocado, <strong>and</strong> papaya are not easily available here <strong>and</strong> mothers also can’tafford to buy them. Mothers are try<strong>in</strong>g their best to feed their children, but they areeconomically poor. Previously mothers used to th<strong>in</strong>k that giv<strong>in</strong>g only milk is enough forchildren. But after we provide education, they sell some milk <strong>and</strong> buy fruits <strong>and</strong> cereals.” -HEW <strong>in</strong> MarekaSome HEWs <strong>in</strong> all areas said that children are gett<strong>in</strong>g enough food <strong>in</strong> some cases, when foods wereavailable <strong>in</strong> the household <strong>and</strong> when other family members provided help <strong>and</strong> support to the mother.The VCHPs <strong>in</strong> Mareka <strong>and</strong> Misha also feel that children are gett<strong>in</strong>g enough food.“…children are gett<strong>in</strong>g enough food because families are produc<strong>in</strong>g adequate vegetables,fruits, <strong>and</strong> cereals. They also buy foods that are not available at home from the market.Other family members give advice <strong>and</strong> money to buy food items from market.” – VCHP <strong>in</strong>MishaAll the HEWs <strong>and</strong> the VCHPs said that while they agree with the feed<strong>in</strong>g recommendations to addanimal flesh foods to a child’s food on a daily basis, they did not feel that this was realistic s<strong>in</strong>ce thesefoods are expensive <strong>and</strong> not readily available. Some did agree that giv<strong>in</strong>g children eggs might be apossible action.Food preparation <strong>and</strong> hygiene. Mothers take the primary responsibility for prepar<strong>in</strong>g food forchildren, sometimes helped by a daughter. In Chenicha, there were also a few cases where thegr<strong>and</strong>mother decides what to prepare <strong>and</strong> feeds the child. When mothers are away from the homedur<strong>in</strong>g the day, food is most often prepared ahead of time <strong>and</strong> left with another family member to feedthe child. In one case <strong>in</strong> Chenicha, the mother said that her husb<strong>and</strong> would prepare the food <strong>and</strong> feedthe child <strong>in</strong> her absence. In the observation households, all of the mothers were seen prepar<strong>in</strong>g thefood, with the husb<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> gr<strong>and</strong>mother look<strong>in</strong>g after the child <strong>in</strong> a few cases while the mother wasbusy.Dur<strong>in</strong>g the observations, almost all mothers were observed wash<strong>in</strong>g their own h<strong>and</strong>s before prepar<strong>in</strong>gfood but with water only <strong>and</strong> not soap. Children’s h<strong>and</strong>s were not washed even though many had theirh<strong>and</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the food or were try<strong>in</strong>g to feed themselves. Dishes, pots, utensils, <strong>and</strong> bottles were all washed18