THE WAYS PEOPLE LEARN By Dr. James B. Slack Exploring the ...

THE WAYS PEOPLE LEARN By Dr. James B. Slack Exploring the ...

THE WAYS PEOPLE LEARN By Dr. James B. Slack Exploring the ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

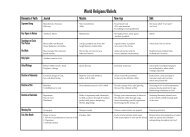

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>WAYS</strong> <strong>PEOPLE</strong> <strong>LEARN</strong><strong>By</strong> <strong>Dr</strong>. <strong>James</strong> B. <strong>Slack</strong><strong>Exploring</strong> <strong>the</strong> Implications of Orality, Literacy and Chronological Bible StoryingConcerning Global EvangelizationIn order for literates to choose <strong>the</strong> proper communication style for presenting <strong>the</strong> Gospelto those within <strong>the</strong> scale from primary illiterate to highly literate, a “Learning Grid” hasbeen developed. Based upon educational research, Jim <strong>Slack</strong> developed <strong>the</strong> LearningGrid in <strong>the</strong> early 1990s for use in connecting pedagogical categories and principles withChronological Bible Storying technology. Until recently, no known graphic of thisnature had been produced by ei<strong>the</strong>r secular or religious sources. An IMB worker in WestAfrica was <strong>the</strong> artist who drew <strong>the</strong> concepts which became <strong>the</strong> Learning Grid in a graphicformat. She did this during an advanced workshop in West Africa in <strong>the</strong> early 1990s.One should secure <strong>the</strong> demographics concerning <strong>the</strong> target people and place those figuresin <strong>the</strong> corresponding section, or sections, of <strong>the</strong> Learning Grid. The initial stage of anorality, literacy and Chronological Bible Storying workshop gives time to introducingparticipants to <strong>the</strong> terminology, demographic indicators, and dynamics of <strong>the</strong> LearningGrid. During this time, <strong>the</strong> positions, or categories are introduced that range from <strong>the</strong>primary illiterate who has never “seen” a word to <strong>the</strong> highly skilled literate who performsat <strong>the</strong> highest level of prose, document, and quantitative activities. The Learning Gridfulfilled <strong>the</strong> need for a graphic presentation of many of <strong>the</strong> terms, concepts, and processesthat literates face when communicating with oral communicators. This graphic iscompatible, but not an exact correlation with <strong>the</strong> technology represented in <strong>the</strong>NALS/IALS and UNESCO studies in <strong>the</strong> United States and o<strong>the</strong>r countries. Had <strong>the</strong>ybeen exactly <strong>the</strong> same <strong>the</strong>re would be no need for this graphic o<strong>the</strong>r than to show<strong>the</strong> correlation between Chronological Bible Storying and expositional andnarrative format uses. The content of this presentation should clarify <strong>the</strong>relationship between <strong>the</strong> Learning Grid categories <strong>the</strong>mselves and representativecategories in <strong>the</strong> academic or technical communities.As you read this presentation, give close scrutiny to <strong>the</strong> way in which eachcategory overlaps according to whichever perspective you use to consider <strong>the</strong> contents.Remember that educational science, thus <strong>the</strong> science of learning, is a behavioral scienceand has to deal with multiple variables that can be minimized but seldom removed ei<strong>the</strong>rin life or analysis.

The Ways People Learn--<strong>Slack</strong> 3There are multiple levels or categories ranging from primary oral learners to highlyliterate learners. Looking back on a century of educational and statistical demographics,one can see that at least five different categories of learning abilities or competencieshave emerged to become a functional reality in our time: (1) primary illiterates, (2)functional illiterates, (3) semi-literates, (4) functional literates, and (5) highly-literateindividuals. Only two of those were formally used in 1900--illiterate and literate.Primary illiterates are individuals who cannot read or write. A primary illiterate hasnever “seen” a word. To <strong>the</strong>m, a written word is nothing more than meaninglessscribbles. Words do not exist as words, but as pieces of a picture, of events and situations<strong>the</strong>y are seeing and experiencing. In fact, for oral communicators, words, as such, haveno exact dictionary type meaning. 1 Illiterates are oral communicators. The story is <strong>the</strong>irdominant communication style. (See Walter J. Ong's Orality and Literacy: TheTechnologizing of <strong>the</strong> Word for a comprehensive, technical presentation of <strong>the</strong>se issues.)A functional illiterate is one who has begun to read and write within a school setting,but who did not progress beyond eight grades, and did not continue to read and writeregularly after dropping out of school. Within two years of dropping out of school, <strong>the</strong>seindividuals often can read simple writings but no longer receive, recall, or reproduceconcepts, ideas, precepts, and principles through literate means. Values, for <strong>the</strong>m, are notreceived through literate means. Even though this type of individual is classified in everycountry of <strong>the</strong> world as a literate in <strong>the</strong>ir literacy percentage quotes, he or she learnsprimarily by means of narrative presentations. It is an error to consider <strong>the</strong>se as literate.Numerous studies during <strong>the</strong> past twenty years has confirmed that. Therefore, functionalilliterates are, like illiterates, oral communicators. In France, <strong>the</strong> common terminology ormeaning of <strong>the</strong> words used to describe <strong>the</strong> functional illiteracy situation is “educationalwastage.” 2 France pioneered in <strong>the</strong> research and development of much of <strong>the</strong> originalunderstanding of functional illiteracy. The National Adult Literacy Study, known asNALs, which has been conducted in at least 30, mostly Western countries, has enhancedwhat was previously known about functional illiteracy. (Again, see Adjunct Readings3.2. and 3.3. for <strong>the</strong> spreadsheets presenting samples of this NALs data on <strong>the</strong> USA.Remember, NALs is a close but not exact representation of <strong>the</strong> Learning Grid.)Semi-literates have usually progressed to at least <strong>the</strong> ninth or tenth grade in a school thathas middle school grades consisting of sixth, seventh, and eighth grades. For thosecountries that do not have <strong>the</strong>se middle school grades, <strong>the</strong> semi-literate level wouldextend to <strong>the</strong> equivalent of a high school graduate in those countries that do have at leasttwelve grades. These individuals function in a gray transition area between oralcommunication and functional literacy. If <strong>the</strong>ir personal high school training includeda significant emphasis on reading, writing, and liberal arts skills, <strong>the</strong>y have probablyprogressed to a literate classification ra<strong>the</strong>r than semi-literate. However, those individuals1 Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of <strong>the</strong> Word (London: Routledge, 1991), 75.2 Ibid.

The Ways People Learn--<strong>Slack</strong> 4who completed ten years of school or secured a high school diploma but did not spend alot of time in developing reading and writing skills, almost always test out to be semiliterate.Semi-literates learn best and most comfortably by means of oral communicationstyle presentations ra<strong>the</strong>r than through literate style presentations. However, most aredeveloping competencies that move <strong>the</strong>m in <strong>the</strong> direction of full literacy. Even so, all ofthose in this category, and most of those in <strong>the</strong> functional illiteracy category wouldbe classified by every school system and every country as literate, when in realitymost prefer and can best handle oral communication learning styles. This is one of<strong>the</strong> many reasons why most published literacy percentages cannot be trusted and used.The published percentages are as much driven by incorrect definitions of literacy;financial lending agency criteria for country loans and aid; and by "saving face" reasonsThe fourth category is literate. Some countries and some of those who work in literacyeducation refer to this category as functional literacy. This is not to be confused with aprevious category of functional illiteracy which is just <strong>the</strong> opposite. Literates are usuallythose individuals who have continued to exercise <strong>the</strong>ir ability to read and write up to andbeyond <strong>the</strong> equivalent of ten grades of school. They have not only gone through <strong>the</strong>grades in school, but have in fact attained <strong>the</strong> competencies equivalent to those grades.They are literate learners. Information such as ideas, precepts, concepts, and principlesare easily understood and handled by <strong>the</strong>m through literate means. Functional literacy is aterm that has been chosen to describe literacy in a way that is not dependent upon <strong>the</strong>number of years in school. 3 A gifted and/or applied learner, usually a self-starter andhighly motivated person, could become functionally literate after only a few years ofstudy, whe<strong>the</strong>r in or out of school. It would also be true that some could study wellbeyond twelve years and not be functionally literate.The average literate person, on <strong>the</strong> way to becoming literate, has lost or given up ameasure of his or her oral communication skills. Like physical body parts, oral skillstend to atrophy if not used regularly. Numerous academic studies in <strong>the</strong> fields ofeducation, psychology and anthropology have been conducted relative to this issue.Atrophy of oral skills is <strong>the</strong> price of becoming literate. The literate’s memory has becomeless and less dependent upon recalling what has been heard orally, and has progressivelybecome dependent upon recorded notes and information contained in books and o<strong>the</strong>rrepositories. These individuals are no longer classified as oral communicators. This doesnot mean that <strong>the</strong>y do not appreciate oral communication or that <strong>the</strong>y will not respond tooral communication. It only means that <strong>the</strong>y are less characterized by orality than byliteracy. A few do carry significant oral skills with <strong>the</strong>m into functional literacy.The fifth, and final category is highly literate. A highly literate person has usuallyspent time daily developing and using reading and writing skills at a very advanced level.Such individuals have usually attended college and are often professionals in liberal artfields. They are thoroughly word-culture individuals. Like literate level individuals, <strong>the</strong>yare no longer predominately oral communicators, but are literate communicators. Theyhave, through education, moved progressively from being an oral communicator to a3 Ibid.

The Ways People Learn--<strong>Slack</strong> 5highly literate communicator. As Walter Ong comments, many of <strong>the</strong>se highly literateindividuals do not remember and thus do not appreciate <strong>the</strong> oral roots from which <strong>the</strong>yemerged.Not only does <strong>the</strong> status of a person change as <strong>the</strong>y progress from oral communicationlevels to literate communication levels, but <strong>the</strong>ir style of communication has changeddrastically. Oral communicators — illiterates, functional illiterates and semi-literates —are not comfortable with, and cannot easily understand information that comes in <strong>the</strong>form of outlines, precepts, principles, and steps in a process. It is difficult, if notimpossible, for <strong>the</strong>m to engage in true analysis. They find it very difficult to outlineand reduce bodies of information to “bottom line” statements. Oral communicatorsprefer that information come to <strong>the</strong>m in <strong>the</strong> form of narratives or stories. They cannoteasily handle, and are definitely not comfortable with information that comes by o<strong>the</strong>rmeans. In fact, if <strong>the</strong>y have a teaching, a concept, or a principle <strong>the</strong>y want toremember, <strong>the</strong>y will clo<strong>the</strong> it in a story. Narrative styles are <strong>the</strong> common vehiclesthat oral communicators use to process and “carry around” information. Expositionalpresentations such as outlines, steps, principles, or lists of any kind are formidableobstacles for <strong>the</strong>m. They find it difficult to understand <strong>the</strong>m, and certainly cannot recall<strong>the</strong>m. They cannot use what <strong>the</strong>y cannot recall. Knowledge for oral communicators,and especially illiterates, consists only of what can be recalled.There are two important considerations. First, oral communicators — illiterates,functional illiterates, and semi-literates — can learn as well as literate persons. Theirability to learn is just as good as literates and <strong>the</strong>ir memory is superior to <strong>the</strong> averageliterate person’s memory. The problem is not that of learning but of <strong>the</strong> presentationformat through which information comes to <strong>the</strong>m. Information must come to oralcommunicators through stories, parables, poems, ballads, and similar types of formats.Format is <strong>the</strong> key for <strong>the</strong>m.Second, and conversely, most literates mistakenly believe that if <strong>the</strong>y can outline <strong>the</strong>information or put it into a series of steps or principles, anyone, including oralcommunicators, can understand it and recall it. That is a misconception concerninglearning, and how different individuals process information. Most oral communicators donot understand outlines, steps or principles, and <strong>the</strong>y certainly cannot remember <strong>the</strong>m.For that matter, nei<strong>the</strong>r can <strong>the</strong> literates, but <strong>the</strong>y store information in notes and can “lookit up” to refresh <strong>the</strong>ir memory. Illiterates cannot “look anything up,” and have nopersonal means of refreshing <strong>the</strong>ir memory if <strong>the</strong>y have forgotten something.It is very important when literate individuals prepare to communicate with o<strong>the</strong>rs that<strong>the</strong>y determine what learning category — illiterate, functional illiterate, semi-literate,literate, or highly-literate — <strong>the</strong> hearer represents before choosing <strong>the</strong> presentationformat. The Learning Grid illustrates <strong>the</strong> relationship between each learning category and<strong>the</strong> corresponding presentation format.When communicating with oral communicators — primary illiterates, functionalilliterates, or semi-literates — <strong>the</strong> story is <strong>the</strong> best “vehicle” that carries <strong>the</strong> information

The Ways People Learn--<strong>Slack</strong> 6to be understood, recalled, and reproduced. 4 When communicating with literates andhighly-literate persons, expositional formats are excellent presentation formats to use. Asone moves “to <strong>the</strong> right” in <strong>the</strong> Learning Grid, more exposition can be used in <strong>the</strong>presentation. As one moves “to <strong>the</strong> left” in <strong>the</strong> Learning Grid, less exposition should beused. For oral communicators, <strong>the</strong> story is <strong>the</strong> preferred style.Failure to match <strong>the</strong> proper presentation style with <strong>the</strong> corresponding learning preferenceor category hinders learning and effective discourse. When <strong>the</strong>re is an improper match,<strong>the</strong> presenter speaks, but <strong>the</strong> receiver seldom “hears.”The Learning Grid was devised to present <strong>the</strong> five major categories and to showwhen a literate should be careful about using expositional formats when communicatingwith oral communicators. The shaded areas are those places or times, duringpresentations, when <strong>the</strong> literate should refrain from using much, if any, expositionalpresentations. Within <strong>the</strong> shaded areas or times, <strong>the</strong> literate, for optimum learning tooccur, should use narrative, story formats for presenting whatever concepts, teachings,ideas, or principles are being presented.4 Ong, 12 and 15.