Risk: From perception to social representation - UMBC Department ...

Risk: From perception to social representation - UMBC Department ...

Risk: From perception to social representation - UMBC Department ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

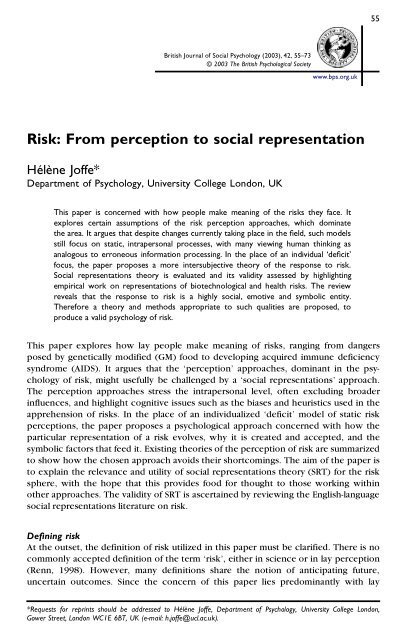

55British Journal of Social Psychology (2003), 42, 55–73© 2003 The British Psychological Societywww.bps.org.uk<strong>Risk</strong>: <strong>From</strong> <strong>perception</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>Hélène Joffe*<strong>Department</strong> of Psychology, University College London, UKThis paper is concerned with how people make meaning of the risks they face. Itexplores certain assumptions of the risk <strong>perception</strong> approaches, which dominatethe area. It argues that despite changes currently taking place in the eld, such modelsstill focus on static, intrapersonal processes, with many viewing human thinking asanalogous <strong>to</strong> erroneous information processing. In the place of an individual ‘de cit’focus, the paper proposes a more intersubjective theory of the response <strong>to</strong> risk.Social <strong>representation</strong>s theory is evaluated and its validity assessed by highlightingempirical work on <strong>representation</strong>s of biotechnological and health risks. The reviewreveals that the response <strong>to</strong> risk is a highly <strong>social</strong>, emotive and symbolic entity.Therefore a theory and methods appropriate <strong>to</strong> such qualities are proposed, <strong>to</strong>produce a valid psychology of risk.This paper explores how lay people make meaning of risks, ranging from dangersposed by genetically modified (GM) food <strong>to</strong> developing acquired immune deficiencysyndrome (AIDS). It argues that the ‘<strong>perception</strong>’ approaches, dominant in the psychologyof risk, might usefully be challenged by a ‘<strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s’ approach.The <strong>perception</strong> approaches stress the intrapersonal level, often excluding broaderinfluences, and highlight cognitive issues such as the biases and heuristics used in theapprehension of risks. In the place of an individualized ‘deficit’ model of static risk<strong>perception</strong>s, the paper proposes a psychological approach concerned with how theparticular <strong>representation</strong> of a risk evolves, why it is created and accepted, and thesymbolic fac<strong>to</strong>rs that feed it. Existing theories of the <strong>perception</strong> of risk are summarized<strong>to</strong> show how the chosen approach avoids their shortcomings. The aim of the paper is<strong>to</strong> explain the relevance and utility of <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s theory (SRT) for the risksphere, with the hope that this provides food for thought <strong>to</strong> those working withinother approaches. The validity of SRT is ascertained by reviewing the English-language<strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s literature on risk.De ning riskAt the outset, the definition of risk utilized in this paper must be clarified. There is nocommonly accepted definition of the term ‘risk’, either in science or in lay <strong>perception</strong>(Renn, 1998). However, many definitions share the notion of anticipating future,uncertain outcomes. Since the concern of this paper lies predominantly with lay*Requests for reprints should be addressed <strong>to</strong> Hélène Joffe, <strong>Department</strong> of Psychology, University College London,Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK (e-mail: h.joffe@ucl.ac.uk).

56 Hélène Joffepeople’s responses <strong>to</strong> the health and safety risks they face, it adopts Douglas’ (1994)definition of risk as simply ‘danger from future damage’ and focuses only on negativerisks. Douglas recognizes that the classical, contemporary definition used in the expertrealm is: ‘the probability of an event combined with the magnitude of the losses andgains that it will entail’ (p. 40). However, she argues that in contemporary thought, riskis less likely <strong>to</strong> include a positive outcome, and, furthermore, from a lay perspective,the connection <strong>to</strong> probability theory and rational choice is not paramount. Laypeople’s tendency <strong>to</strong> bypass probability theory is not explained in terms of theirinability <strong>to</strong> understand ‘the sums’, but in relation <strong>to</strong> the absence, in the classicaldefinition, of some of the issues that people care about.The overarching definition of risk as ‘danger from future damage’, at least from thelay perspective, is antithetical <strong>to</strong> a strand of the risk literature in which painstakingdifferentiation is made between ‘natural’ and ‘human-made’ disasters, as well asbetween ‘hazards’ and ‘risks’. 1 While the division appears irrefutable, from the layperspective, it is tenuous. One of the more robust findings in <strong>social</strong> psychologyindicates that lay thinkers conceptualize misfortunes as if human choices wereinvolved, whatever their material basis. People engage in such ‘spontaneous’ causalthinking particularly in relation <strong>to</strong> unexpected and more negative events (Weiner,1985). Therefore, distinctions between different categories in the risk literature areundermined by people’s tendency <strong>to</strong> implicate individual decisions—such as those <strong>to</strong>live in a particular place or <strong>to</strong> fail <strong>to</strong> implement safety checks—in their readings ofmisfortunes (see Walster, 1966). The scenarios discussed in this paper are both negativeand unexpected, and are therefore likely <strong>to</strong> evoke the ‘why’ question, and also <strong>to</strong>have a degree of the ‘human-made’ element read in<strong>to</strong> them, whatever their materialbasis.Finally, when defining risk, a question arises concerning the need <strong>to</strong> consider itsexistence ‘out there’. It might be argued that one cannot talk of lay responses <strong>to</strong> risks,since those phenomena that are perceived as ‘risks’ already embody people’s constructions.In this paper, risks, and the responses <strong>to</strong> them, are viewed as separate entities,but there is recognition that phenomena read as risks already contain <strong>social</strong> constructions.This follows Yardley’s (1997) material-discursive position in which a ‘risk’ isboth a material phenomenon and a <strong>social</strong>ly constructed one. However, it is with the‘readings’ of risks, particularly from the lay perspective, that the paper is concerned.Understanding the relationship between a potential danger and the reading thereofdepends upon the theoretical position adopted.Perceiving risk: Optimistic bias and beyondSince the 1950s, psychologists have been increasingly interested in how lay peopleperceive risks. Mainstream, psychological research has focused on the cognitive processesthat occur when humans are faced with risks. Kahneman, Slovic, and Tversky(1982) state that: ‘Cognitive psychology is concerned with internal processes, mentallimitations, and the way in which the processes are shaped by the limitations’ (p. xii).1 ‘Natural’ disasters include earthquakes, hurricanes, and oods. The ‘human-made’ disasters are those producedabundantly in contemporary Western society: nuclear and industrial accidents, the greenhouse effect, acid rain and so on.‘Hazards’ tend <strong>to</strong> be distinguished from ‘risks’ in that damage comes from an external source. The properties associatedwith the ‘natural’ disaster and ‘hazard’ categories overlap substantially. ‘Hazards’ are said <strong>to</strong> become ‘risks’ as soon asanything becomes known about how the danger might be averted; in other words, once human action can be taken inrelation <strong>to</strong> it.

Perception of risk 57In line with this, the area of judgment and decision-making regarding risks tends <strong>to</strong>evaluate the probabilities that individuals offer in relation <strong>to</strong> their chances of becomingaffected by a particular risk. Probabilities offered are often compared with scientificestimates of probability, and the focus has been upon the existence and source of layerror (see Kahneman et al., 1982, for a review).Thriving branches of the Tversky and Kahneman (1974) inspired risk <strong>perception</strong> areahave remained centrally focused on individual perceptual or cognitive errors. The areasthat examine the tendency <strong>to</strong>wards ‘overconfidence’ regarding one’s own judgments ofrisk, and the optimistic ‘bias’ (OB) tradition, pursue the notions of the fallibility orfaultiness of human information processing. In some sense, the two areas are connectedin their focus on people’s optimism, and the latter tradition will be highlighted.Scope and ndings of the OB approachThe OB approach has examined responses <strong>to</strong> a vast array of the health and safety risksthat people confront both daily and in more unexpected circumstances. It is employedextensively in the burgeoning health risk sphere forming a core element in many <strong>social</strong>cognition models that attempt <strong>to</strong> predict fac<strong>to</strong>rs that facilitate risk-taking. Theseinclude the Health Belief Model (Rosens<strong>to</strong>ck, 1974), Protection Motivation Theory(Rogers, 1975) and the Health Action Process Approach (Schwartzer, 1992). The coreof the theory is examined, in brief, as an inroad in<strong>to</strong> some of the limitations of thecognitive models. 2OB focuses on errors made when people compare their own, as opposed <strong>to</strong> others’,chances of coming in<strong>to</strong> contact with a host of misfortunes such as car accidents, radonproblems in the home, and HIV. When asked <strong>to</strong> think about their chances of facingrisks, people imagine, unrealistically, that the future holds few adverse events (Taylor,1989) and expect these <strong>to</strong> strike others, rather than themselves (Weinstein, 1982).Weinstein’s and Taylor’s influential work on OB describes the robust and widespreadnature of the personal sense of invulnerability. Taylor and Brown (1994) go as faras <strong>to</strong> assert that, typically, more than 95% of the population may exhibit unrealisticoptimism in relation <strong>to</strong> a wide range of risks.Weinstein (1987) attributes OB <strong>to</strong> information-processing errors: people’s lack ofexperience with the problem makes it difficult for them <strong>to</strong> imagine how it might affectthem; people compare themselves with others who are at particularly high risk inorder <strong>to</strong> maintain a sense of low personal risk; people overestimate the skills theypossess that would allow them <strong>to</strong> avoid being affected by the risk. This focus on thecognitive tricks played by individual minds resonates throughout the risk-<strong>perception</strong>literature, with its focus on biases such as those of availability, overconfidence and thedesire for certainty (see Slovic, Fischhoff, & Lichtenstein, 2000). Even though there isconsiderable debate concerning the ubiquity of the OB phenomenon, it centres onchallenges <strong>to</strong> aspects of the model rather than <strong>to</strong> its core assumptions. 3 The key tenet,2Since the focus of the current paper is on approaches used <strong>to</strong> map people’s thoughts, rather than their behaviouralintentions concerning potential dangers, models concerning people’s behavioural intentions in risky situations are notreviewed. These include the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behaviour, which have been employedextensively for assessing behavioural intentions such as those <strong>to</strong> practice safer sex (see Sheeran, Abraham, & Orbell,1999). The author has appraised these models elsewhere (see Joffe, 1996a).3Question marks hang over the degree <strong>to</strong> which OB manifests in the population as a whole (see Myers & Brewin, 1996;Myers & Renolds, 2000), <strong>to</strong> whether it exists cross-culturally (see Heine & Lehman, 1995; Kleinhesselink & Rosa, 1991;Peeters, Cammaert, & Czapinski, 1997; Taylor & Armor, 1996), <strong>to</strong> its links <strong>to</strong> the ‘actual’ risks faced (see Klein &Radcliffe, 1999) and <strong>to</strong> whether it is an illusion of control rather than of optimism (McKenna, 1993).

58 Hélène Joffeenshrined in OB and a broad spectrum of risk <strong>perception</strong> models, that many humansare basically risk-averse, but unintentionally miscalculate their risks due <strong>to</strong> cognitivedeficits, such as an inefficient handling of information, remains unquestioned.Challenging the assumptions of risk ‘<strong>perception</strong>’This assumption can be challenged along a number of dimensions. Wynne (1982)coined the now widely used term ‘deficit model’ <strong>to</strong> denote how objective scientists arejuxtaposed <strong>to</strong> irrational lay people in many theories of the human response <strong>to</strong> risk.Although the 1990s have heralded modifications in such theorization (see Pidgeon,Hood, Jones, Turner, & Gibson, 1992), it survives in both psychological theory andthe policy arena. Here the public is seen <strong>to</strong> be lacking intellectually, when measuredagainst ‘authoritative science’. In relation <strong>to</strong> nuclear power, for example, itsproponents have demanded that public debates evaluate the ‘hard facts’, withoutreference <strong>to</strong> other realms (Wynne, 1982). Yet when lay people think about nuclearpower they do not merely process information concerning the ‘hard facts’ utilizingvarious biases and heuristics. Nuclear power is a highly emotive issue. It carriessymbols of scientific and technological hubris and of environmental destruction. Theemotive, symbol-laden response <strong>to</strong> nuclear power is as legitimate as the scientific takeon it, rather than a delusional deviation from ‘objective reality’.Furthermore, talk of deficits in handling risk information, <strong>to</strong> varying degrees,assumes that the human mind is analogous <strong>to</strong> a machine. This obscures not only thesymbolic, meaning-making and emotive realms, but also the inter-subjective qualities ofhuman experience. Each will be highlighted. The cognitivist view of the human beingis a simplification, according <strong>to</strong> Moscovici (1984a), because society is not a source ofinformation, but of meaning. People forge questions and seeks answers about issuesthat concern them, rather than purely perceiving and processing the information theyreceive (Moscovici, 1984b). The notion of a mechanical processing of information alsounderplays the emotive element of the response <strong>to</strong> danger from future damage. In arecent re-evaluation, Slovic (2000a) states that:Although risk <strong>perception</strong> was originally viewed as a form of deliberative, analytic informationprocessing, over time we have come <strong>to</strong> recognise how highly dependent it is upon intuitive andexperiential thinking, guided by emotional and aVective processes (p. xxxi).The 1990s heralded a modification from the almost exclusive cognitive emphasis in therisk <strong>perception</strong> field, <strong>to</strong>wards recognition of the importance of affect. While this shifthas yielded useful findings, which will be illustrated, the status given <strong>to</strong> affect stillspeaks <strong>to</strong> the ‘deficit model’.Finucane, Alhakami, Slovic, and Johnson (2000) state that individuals use an‘affect 4 heuristic’ <strong>to</strong> make judgments. In relation <strong>to</strong> risk <strong>perception</strong>s, these are mentalshort-cuts by which individuals judge the risks and benefits of a hazard by accessingthe pool of positive and negative feelings that they associate with it. They do this eitherconsciously or unconsciously. In a related line of argument, emotions are viewed asentities that limit the search space of the reasoner: ‘They are heuristics that help usmake occasional leaps in life where no rational structures have yet been built <strong>to</strong> bridgethe ravines of our ‘‘ignorance’’ ’ (Oatley, 1996, p. 194). By way of example, Oatleystates that falling in love is a heuristic for having a relationship. According <strong>to</strong> his4 Affect, according <strong>to</strong> these authors, includes both feeling states that people experience (e.g. sadness) and qualitiesassociated with a stimulus (e.g. badness). However, much of the affective work that Slovic (2000a) is associated withcounts as affect the positive or negative valence with which various associations are rated.

Perception of risk 59argument, falling in love is a ravine of ignorance for which there will yet be built arational structure. It appears that a concern with cognitive theorists gripped by theemotion turning point still cling <strong>to</strong> some of their rationalist assumptions: ‘Emotionsbias thinking’ (Oatley, 1996, p. 194). In relation <strong>to</strong> the spate of studies borne of such ashift, Slovic (2000a) states that ‘it is tempting <strong>to</strong> conclude that these studies demonstratethat lay people’s <strong>perception</strong>s of risk are derived from emotion rather thanreason, and hence should not be respected . . .’ (p. xxxii).Even though the ‘emotional turn’ appears radical, it perpetuates the downgrading ofemotional aspects of lay thinking by privileging rational structures of the mind. Theexplicit low status accorded <strong>to</strong> the emotional underpinnings of ‘<strong>perception</strong>’ belies theapparent openness <strong>to</strong> moving away from conceptualizing responses <strong>to</strong> risk as (ideally)rational information processing.Not only do cognitive theories of risk <strong>perception</strong> remain focused on informationprocessing, but they are unified in their centre of attention being the intrapersonallevel. Cognitive psychologists recognize that until the 1990s the <strong>social</strong> nature of mostcognition was rather neglected (e.g. Oatley, 1996). Yet theorists such as Slovic, again,have been at the forefront of rethinking the role of <strong>social</strong> issues in risk <strong>perception</strong>. ForSlovic (1997), ‘worldviews’ or <strong>social</strong>, cultural and political attitudes, guide people’sjudgments of risks. In Slovic and colleagues’ empirical work, fatalism, individualism,egalitarianism and technological enthusiasm are key ‘worldviews’ used. They discoverthat public <strong>perception</strong>s of risks are correlated with particular worldviews (e.g.egalitarians tend <strong>to</strong> be strongly anti-nuclear). For Slovic and colleagues, worldview, likeaffect, is an orientating mechanism, directing how people judge risks.While this focus has the potential <strong>to</strong> revolutionize the field, worldview is theorizedas a quasi-dispositional, static state in this research. Yet, the worldview with whichpeople approach danger is shaped by other people, as well as cultural and institutionalforces. A challenge that Douglas (1994) lays at the foot of risk <strong>perception</strong> is that it saysalmost nothing about inter-subjectivity, consensus-making and <strong>social</strong> influences ondecisions. The public <strong>perception</strong> of risk is treated as if it were an aggregated responseof many private individuals. Irwin and Wynne (1996) augment this line of critiquewhen they state that in the risk <strong>perception</strong> approaches, the public is ‘implied <strong>to</strong> be anaggregate of a<strong>to</strong>mised individuals with no <strong>social</strong> composition, hence no legitimateau<strong>to</strong>nomous cultural substance’ (p. 215).This reflects a commitment <strong>to</strong> methodological individualism, on the part ofcontemporary cognitive psychologists: the doctrine that <strong>social</strong> phenomena can beunders<strong>to</strong>od solely with reference <strong>to</strong> ‘facts’ about individuals (Bhaskar, 1979). Thenatural sciences are emulated, and abstract, universal laws of human behaviour thattranscend individual, <strong>social</strong>, cultural and temporal boundaries are sought (see Kim,1999).The complex array of interpersonal, intergroup and ideological forces at work in risk‘<strong>perception</strong>’ cannot be linearly mapped. Slovic (2000a) laments that the psychometricrisk approach, in its desire for breadth and quantitative measures, sacrifices depth.Perhaps the risk-<strong>perception</strong> models have not moved as far from ‘cognitive algebra’(Spicer & Chamberlain, 1996), or the process of enclosing variables in boxes andlinking them with arrows <strong>to</strong> designate causality, as had been hoped. Spicer andChamberlain (1996) describe this as the ‘pathology of flow-charting’, which militatesagainst careful theory building (see Chamberlain, 2000).In summary, in the cognitive models the machine-like, rather than meaning-makingqualities, of the individual mind are emphasized. For Moscovici (2000), <strong>perception</strong> has

60 Hélène Joffeprimacy in less <strong>social</strong> branches of psychology, but <strong>representation</strong> has primacy in a<strong>social</strong> psychology of common sense. While <strong>perception</strong> is based upon sensorial knowledge,<strong>representation</strong> is concerned with symbols, <strong>social</strong> reality and <strong>social</strong> knowledge.Closely related <strong>to</strong> this line of argument, Pidgeon et al. (1992) point out that while thestimulus <strong>to</strong> the <strong>perception</strong> can be relatively objectively characterized in perceptualpsychology, in the psychology of risk the stimulus is already represented by scientists,when most people come <strong>to</strong> think about it. One might add that media <strong>representation</strong>salso intervene. Consequently, a series of <strong>representation</strong>s underpin lay people’s readingsof risks. The paper moves <strong>to</strong> addressing the need for a valid theory of how peopleconstruct risks. Instead of producing a generalized framework for pinpointing thejudgment strategies under way when people respond <strong>to</strong> risks, the aim is <strong>to</strong> enter in<strong>to</strong>the specific complexity of the meanings made of risks by people positioned withinspecific <strong>social</strong> contexts.Representing risk: The <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s approach<strong>From</strong> the 1960s onward, a strand of psychological research, which conceptualizes thereading of risk very differently from the dominant paradigm, has developed. In theplace of risk <strong>perception</strong>, the <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong> (Moscovici, 1976, 1984a, 1984b,2001) of risk (Joffe, 1999) places great emphasis upon fac<strong>to</strong>rs beyond individualinformation processing. Rather than conceptualizing lay readings of risk as deficient,they are viewed as entities that contain the eccentric contents of people’s reposi<strong>to</strong>riesof knowledge (Michael, 1996), which both express and protect their identities.SRT refers both <strong>to</strong> the process through which <strong>representation</strong>s are elaborated and thestructures of thought that emerge (Duveen, 2000). The theory maps the processeswhereby sociocultural, his<strong>to</strong>rical and group-specific forces become sedimented ininner experiences, how the ‘we’ becomes contained in the responses of the ‘I’. Themass media play a major role as do interpersonal interactions whereby existing <strong>representation</strong>sthat circulate in a given culture are communicated between people andenter their explanations of new events. The <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s that emerge arerelatively consensual understandings of phenomena, particular <strong>to</strong> specific <strong>social</strong>networks.Although not restricted <strong>to</strong> the risk sphere, SRT is particularly useful for it, since it isoriented <strong>to</strong>wards exploration of explanations that arise in the face of new events(Hews<strong>to</strong>ne & Augoustinos, 1998). Two key research areas are chosen <strong>to</strong> cast light onthe contribution offered <strong>to</strong> the risk field by this approach: responses <strong>to</strong> health threatsand <strong>to</strong> biotechnology. Alongside examples from work on responses <strong>to</strong> mental illness,they are used <strong>to</strong> demonstrate the role played by forces external <strong>to</strong> individuals, ratherthan intrapersonal processing, in shaping people’s risk-related thinking.The transformation of science in<strong>to</strong> common senseA key concern within SRT relates <strong>to</strong> how knowledge about a phenomenon, such as GMfood, changes as the mass media transform it from the more reified, scientific universein<strong>to</strong> lay thinking. Moscovici introduced the concept of <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong> as a <strong>to</strong>ol<strong>to</strong> explore the transformation of science in the course of its diffusion, and <strong>to</strong> examinethe common sense that arises in its wake (see Moscovici, 1998). ‘Transformation’, byits very definition, involves making changes <strong>to</strong> the initial content. In contemporarysociety, the mass media play the leading role in transforming expert in<strong>to</strong> lay

Perception of risk 61knowledge. The lay person’s first contact with a potential danger is often via thenews media, or via other people relaying items presented there. News media do notmerely present a ‘pho<strong>to</strong>copy’ of expert knowledge of risks. Instead, they simplify andsensationalize it, and set up debates concerning responsibility and blame, in the hopeof attracting the attention of mass audiences. The process often results in risks beingframed in a manner more akin <strong>to</strong> moral outrage than <strong>to</strong> scientific notions of calculablerisk (see Brown, Chapman, & Lup<strong>to</strong>n, 1996; Herzlich & Pierret, 1989).By concluding that dissemination of scientific ideas involves its saturation withvalues, one does not negate that scientific ‘facts’ already contain a considerable valuedimension (see La<strong>to</strong>ur & Woolgar, 1979). The point is not that a ‘pure’ scientificaccount is transformed in<strong>to</strong> a value-ridden common sense. Rather, as will be demonstrated,different ways of thinking arise in the different spheres, and these are linked <strong>to</strong>processes of meaning-making that emerge between institutions and individuals ratherthan intrapersonally.How is the scientific knowledge that the mass media transform taken up bylay people? Social psychology disavowed the notion of the ‘direct effects’ of themass media back in the 1950s, and there has been increasing realization that laythinkers bring aspects of an ‘already known’, 5 <strong>to</strong> their understanding of mediacontent. Yet the link between the individual’s understanding of newly encounteredphenomena and the particular messages <strong>to</strong> which he/she is exposed has remainedinsufficiently operationalized both outside and within <strong>social</strong> psychology (Wagner,Valencia, & Elejabarrieta, 1996). SRT’s energies are increasingly placed in attempts <strong>to</strong>develop the media–mind link, as opposed <strong>to</strong> the risk <strong>perception</strong> field’s intrapersonalfocus.The European public’s response <strong>to</strong> biotechnology, studied from a SRT perspective,forms a stage in the progress of this endeavour. In parallel <strong>to</strong> the moral intimation withwhich risks are imbued in the media realm, the European public (gauged by way ofrepresentative samples of national residents over 15 years old in all European Unioncountries) emphasizes the moral dimension in thinking about whether variousbiotechnological risks are acceptable <strong>to</strong> society (Concerted Action Group, 1997).Although they are deeply ambivalent about biotechnology, Europeans tend <strong>to</strong> acceptcertain risks, such as the medical uses of genetics, and this is dependent upon theirsense of its usefulness 6 and moral correctness. These authors define moral issuesas a collection of anxieties about the unforeseen dangers involved in a range oftechnologies that are perceived as ‘unnatural’. This very definition points <strong>to</strong> thenon-perceptual approach <strong>to</strong> risk adopted in this study. It hypothesizes that anxietiesand the symbolization of biotechnology as ‘unnatural’, rather than cognitive strategiesand errors in information processing, occupy centre stage in the process of risk<strong>representation</strong>.Are the moral concerns found in both media and lay <strong>representation</strong>s of riskslinked <strong>to</strong> a direct transmission process? The representative European findings werecompared with those from a US survey that asked the same key questions. In parallel<strong>to</strong> the survey, the press reportage of biotechnology in Europe and the USA was5 That which is ‘already known’ includes personal experience, political beliefs, and criticisms held in relation <strong>to</strong> media andgovernment sources of information. Those with certain constellations of the ‘already known’, such as broadsheet readers,constitute interpretative communities or interest group (see Corner, 1991; Joffe & Haarhoff, 2001).6 This resonates with the psychometric tradition’s nding that those hazards perceived <strong>to</strong> have high benet are perceived<strong>to</strong> have a low risk, and vice versa. This has recently been linked <strong>to</strong> affect (e.g. things people like are imagined <strong>to</strong> be lessrisky than those they do not; Alhakami & Slovic, 1994).

62 Hélène Joffecontent- analysed. Gaskell, Bauer, Durant, and Allum (1999) found that the Europeanpress coverage tended <strong>to</strong> talk more positively about biotechnology than the US coverage.Yet European public opinion was more negative than in the USA. This finding puts<strong>to</strong> rest the supposition that public attitudes correspond <strong>to</strong> what the public reads in thepress. Other fac<strong>to</strong>rs colour what is read: trust in the authorities that regulatebiotechnology is greater in the USA than in Europe. This may bolster the NorthAmericans’ positive relationship <strong>to</strong> biotechnology while leaving the Europeans with anelevated sense that they will not be protected from risk. A sense of confidence thatexperts can be relied on <strong>to</strong> act benevolently, rather than intrapersonal, cognitivefac<strong>to</strong>rs, may play a determining role in risk apprehension. Furthermore, and with majorimplications for the SRT field, the Europeans are found <strong>to</strong> have a significantly greatersense of the adulteration, infection and monster-qualities associated with GM food 7 ,than the North Americans. The importance of this sense of menace, like the issues oftrust and anxiety-based concerns, spotlights the emotive aspects of the response<strong>to</strong> risk 8 .While the findings presented from the biotechnology study are rather broad in theirfocus on whole cultures, rather than on members of specific groups, the cross-culturalcomparison suggests how different cultural currents build specific patterns of laythinking. They also show that rather than being passive or erroneous perceivers ofideas from experts and the mass media, lay people actively forge <strong>representation</strong>s in linewith their concerns, which are often driven by emotions. Anxiety and trust, ratherthan ‘cold’ information-handling processes, may well play pivotal roles in theapprehension of risk.Joffe (1996b, 1999) develops this thesis. In line with a psychodynamic extension of<strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s theory, it is posited that individuals faced with potential dangeroperate from a position of anxiety that motivates them <strong>to</strong> represent the danger in aspecific way. The psyche develops from affective roots, with the infant experiencinganxiety from birth. A key and deep-seated mental process used <strong>to</strong> alleviate anxiety issplitting. This unconscious defence mechanism is generally associated with takingin<strong>to</strong> the self good experiences and feelings, and projecting outward bad experiencesand feelings. The goal of splitting, manifest in <strong>representation</strong>s, is <strong>to</strong> keep the bad awayfrom the good in the hope that the good will not be invaded and destroyed. Thus, inthe earliest years of life, individuals protect a positive inner space by holding split<strong>representation</strong>s of what they experience. A universal life force motivates this protectiveprocess. This mechanism comes <strong>to</strong> the surface when dangers are representedthroughout life.In a study of responses <strong>to</strong> AIDS in Britain and South Africa, Joffe (1996a) shows thatthe early pattern that allows individuals <strong>to</strong> handle anxiety manifests in <strong>representation</strong>sof people who ‘leak’ AIDS in<strong>to</strong> the space of the ‘general public’. They are fantasized interms of a cocktail of sinful activities. Yet the content of the categories ‘moral/good’and ‘sinful/bad’, and whether the splitting response is evoked, does not stem fromintrapersonal information processing. Rather, messages that circulate in the <strong>social</strong>environment constrain or exacerbate splitting. Initial links made by scientists betweenAIDS and that which lies outside of the morally acceptable terrain of western thought7Such qualities were only gauged in relation <strong>to</strong> food biotechnology in this study.8 Slovic and colleagues work with similar concepts. Slovic, Flynn, and Layman (1991) asked respondents <strong>to</strong> note thethoughts or images that came <strong>to</strong> mind related <strong>to</strong> ‘underground nuclear-waste reposi<strong>to</strong>ry’ and found the majority ofthe associations <strong>to</strong> be negative, revealing dread, revulsion and anger.

Perception of risk 63(e.g. links <strong>to</strong> ‘poppers’, Haitian voodoo and blood-based rituals with animals) werepicked up, magnified and sensationalized by the Western mass media. The shared<strong>representation</strong>s that emerged in lay thinking responded <strong>to</strong> the anxiety raised bysuch reports, and their content, projecting this illness away from the space of in-groupand self.Social <strong>representation</strong>s research has been criticized on a number of different counts(e.g. see Fife-Shaw, 1997; Joffe, 1997; Potter & Edwards, 1999; Potter & Wetherell,1998). Regarding its application <strong>to</strong> the risk field, in particular, it might frustrate thoselooking for a predictive theory. Since linear, causal models are dominant in psychology,non-predictive models appear flawed. SRT’s deliberate attempt <strong>to</strong> build acomplex model of common-sense understanding, which contains multiple, reciprocalinfluences, appears insufficient. Although the theory leads one <strong>to</strong> expect that certainfac<strong>to</strong>rs will be present in responses <strong>to</strong> risk, such as associating them with ‘bad’ others,aspects of the meaning systems regarding each risk will be unforeseen. The very aim ofempirical work is <strong>to</strong> discern the specific constellation of meaning that evolves aroundeach particular risk.How common sense is built: Anchoring and objectifyingAn SRT approach <strong>to</strong> risk is distinctive in that it proposes that two specific processesare used when people, be they scientists, journalists or lay people, build <strong>representation</strong>sof events: anchoring and objectification (Moscovici, 1984b). Common senseis built by these rather than being an error-prone response <strong>to</strong> probabilistic scientificreasoning. These processes not only ensure that the core values and norms of thesociety are stamped on<strong>to</strong> new events, as the AIDS-linked <strong>representation</strong>s demonstrate,but drive mutations in common sense over time. As a consequence of anchoring, whena new event must be unders<strong>to</strong>od, its integration is accomplished by moulding it in away that it appears continuous with existing ideas (Moscovici, 1984b). Therefore,meaning is made of many newly discerned mass illnesses in line with those known,whatever their differences, at a material level. This is exemplified in AIDS beingreferred <strong>to</strong>, initially, as a ‘gay plague’ and its sufferers being ‘avoided like the plague’ inline with its anchor <strong>to</strong> the ‘great plague’ (Wellings, 1988).Anchoring is not purely an intrapersonal process of assimilation. Rather, the ideas,images and language shared within groups steer the direction in which memberscome <strong>to</strong> terms with the unfamiliar. This makes the alien event imaginable. However,it removes from the new event both its specificity and its potentially threateningquality.Since an emphasis in SRT is on how new risks are anchored <strong>to</strong> known dangers, agoal of a number of studies is <strong>to</strong> explore the continuities and discontinuities betweencurrent and past <strong>representation</strong>s of seemingly similar <strong>social</strong> objects. In taking thislongitudinal view, the field highlights the influence of socio-his<strong>to</strong>rical, rather thaninternal cognitive processes, on risk-related thinking. Markova and Wilkie (1987)showed that early <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s of AIDS, in the West, reflected voices from themass media, the women’s and the gay movement, transforming the <strong>representation</strong>sabout sexually transmitted diseases that had circulated in the syphilis epidemic of theFirst World War. Both syphilis and AIDS had been anchored <strong>to</strong> death, stigma, immoralbehaviour and just punishment. The government-led campaigns accompanying bothhad, <strong>to</strong> varying degrees, emphasized protection of the body, via condom use, and thedefence of dominant value systems via monogamy.

64 Hélène JoffeDespite this anchoring, major differences between the responses <strong>to</strong> the twoepidemics included: recognition of the sexuality of both genders in the time of AIDS,rather than dwelling upon male sexuality requiring outlet as occurred in the time ofsyphilis; and sexually explicit AIDS campaigns when juxtaposed with the discreetnature of the discussion of sexuality at the time of syphilis. The women’s and gaymovement had shifted the <strong>representation</strong> of the contemporary illness away fromheterosexual masculinity <strong>to</strong> wider sexual forces, yet the moralistic and stigmatizingresponses had survived. The longitudinal view of <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s of these illnessesreflects the impact of <strong>social</strong> processes, such as <strong>social</strong> influence, on lay thinking.This demonstrates that meanings of risks contain, in addition <strong>to</strong> the emotive elementsdiscussed, political dimensions, rather than purely cognitive elements.In <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong> formation, the process termed objectification works intandem with anchoring, transforming the abstract links <strong>to</strong> past ideas that anchoringsets up in<strong>to</strong> concrete mental content. Unfamiliar ideas can be made familiar by beinglinked <strong>to</strong> his<strong>to</strong>rically familiar episodes and/or <strong>to</strong> the culturally familiar. While anchoringinvolves drawing on shared knowledge from the past, objectification involvesdrawing on the current experiential world of the particular group member (Wagner,1998; Wagner et al., 1999). Objectification saturates an unfamiliar object with somethingmore easy <strong>to</strong> grasp. The earliest study in the SRT area demonstrates this. Whendifferent milieus (or naturalistically occurring <strong>social</strong> networks) in France werefaced with the new profession of psychoanalysis, it was initially saturated with theimage of ‘the confession’ among Catholic French people, and, in keeping with their se<strong>to</strong>f concerns, they rejected its focus on sexuality (Moscovici, 1976). This made itimaginable for this group’s members in a way that did not threaten their existingworldview. Other groups, such as the Communist milieu and the bourgeoisie,assimilated it in terms of different images: Confession and sexual repression played aless significant role in their experiential world.The trove of familiarity that is drawn upon <strong>to</strong> make a new phenomenon more concretelies in a <strong>social</strong> network’s images, symbols and metaphors (Wagner, Lahnsteiner, &Elejebarrieta, 1995). SRT-driven research on people experiencing the threat of mentalillness illustrates this. When rural, French families were interviewed about their role ashosts of mentally ill lodgers, they drew on images close <strong>to</strong> their everyday experience:They talked of decay, souring, going off and curdling <strong>to</strong> explain the process of becomingmentally ill (Jodelet, 1991). Their everyday experience offered up a diet of images fromwhich they could choose <strong>to</strong> characterize the phenomenon they sought <strong>to</strong> understand.The common thread in their responses indicates that the farmers’ <strong>social</strong> existence, ratherthan intrapersonal reactions, shaped their <strong>representation</strong>s.The mass media appear <strong>to</strong> form part of people’s <strong>social</strong> existence, their experientialworld. While the direct, visceral level is absent, mass media images may operate in asimilar manner <strong>to</strong> experience. The souring milk metaphor adhered <strong>to</strong> by the Frenchrural people may be the equivalent of the ‘monstrous’ and ‘contagious’ images ofgenetically engineered food held in Europe. In competing for mass audiences, tabloidstylenewspapers transmit menacing images of the biotechnology issues they cover(Wagner & Kronberger, 2001), and these may act as an ‘experiential’ resource forrepresenting such issues in the groups that consume them. The biotechnology studydemonstrates that the media–mind link is complex. In the same way that people prefer<strong>to</strong> converse with others of similar opinions, so they may read newspapers likely <strong>to</strong>confirm their own beliefs. This confounds the notion of a unidirectional flow ofinformation from media <strong>to</strong> mind.

Perception of risk 65As noted, cognitive risk traditions do not tend <strong>to</strong> pay attention <strong>to</strong> the externalmessages that people may draw on. Talking of cognitive traditions in general, Marcusand Plaut (2001) state that variation in individuals’ attitudes and schemas in differentimmediate <strong>social</strong> contexts (such as when other people are present or not, or otherpeople are in positions of authority or not) have been examined. Yet only scantattention has been paid <strong>to</strong> meaning systems that are likely <strong>to</strong> be shared as a result ofpeople being similarly positioned in the <strong>social</strong> world. Thus meaning systems have notbeen acknowledged <strong>to</strong> be a significant aspect of the <strong>social</strong> context. Sociologists havedevoted considerable energy <strong>to</strong> stressing the distinctive <strong>social</strong> context in which meaningsof risks are currently forged. The ‘risk society’ (Beck, 1986/1992) or ‘risk climate’(Giddens, 1991) refers <strong>to</strong> the conditions of contemporary western society in whichpeople have high levels of awareness of myriad risks, yet a lack of trust in the expertswho might be relied upon for protection from them. Such conditions are potentiallyanxiety-provoking, particularly since the nature of the risks created by the momentumof contemporary innovation—genetic, nuclear, chemical and ecological—increasinglyeludes the control of society’s protective institutions (Beck, 1986/1992, 1996). If laythinking is assumed <strong>to</strong> be linked <strong>to</strong> this external world of risks, <strong>to</strong> be shaped inthe communications that people experience, it would be curious <strong>to</strong> conceptualizereadings of risks as intrapersonal processes, devoid of interaction with (and within)this pervasive environment.This is an environment replete with symbols. The process of objectification overlapssignificantly with that of symbolization, a useful though severely under-representedconcept for risk research 9 . Symbols provide people with a means <strong>to</strong> understandabstract matters. In a study of <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s of Ebola in Britain, Joffe andHaarhoff (2002) found that Ebola was symbolized in terms of science-fiction imagery.While none of the newspaper articles that gave the Bri<strong>to</strong>ns their information onEbola referred <strong>to</strong> science fiction directly, pictures of people in protective clothingaccompanied some articles. Participants in the study may have ‘read’ these clothes asspace suits and, along with the popular film of the time (‘Outbreak’) that depictedsimilar images, this appears <strong>to</strong> have activated talk about a science-fiction scenario. Suchimagery not only designated Ebola’s distance from the present space of the Britishrespondents, but fed their sense of immunity from it.The focus on such symbols highlights a very specific role for SRT. It locatessome of its concerns beyond the linguistic expression of individual respondents. Thisdistinguishes it from those psychological traditions dependent on language for theirinroads in<strong>to</strong> psychic life. While work on the impact of imagery is in its early stages,Corner, Richardson, and Fen<strong>to</strong>n (1990) argue that images can exert a ‘positioning’power on viewers’ imagination, which may be resistant <strong>to</strong> commentaries that challengethe feelings they produce. They may be readily absorbed in an unmediatedmanner because viewers are not generally provoked <strong>to</strong> reflect on or <strong>to</strong> deconstructthem.The identity-protective motivation that drives <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>This does not imply that stimuli are ‘perceived’ in an unmediated fashion. Rather, textsand images are seen through a lens of existing, often <strong>social</strong>ly shared <strong>representation</strong>s9 For noteworthy exceptions, see a few recent studies by Slovic and colleagues (Slovic, 2000a).

66 Hélène Joffewhich in turn, are underpinned by various motivations. A core motivation 10 in relation<strong>to</strong> risk apprehension is identity protection, which refers, simultaneously, <strong>to</strong> the protectionof in-group and self identity. Social <strong>representation</strong>s are entwined with identity in anumber of ways. They emerge precisely in response <strong>to</strong> danger <strong>to</strong> the collective identityof the group, and consequently, a central purpose of <strong>representation</strong> is <strong>to</strong> defendagainst feeling threatened (Moscovici, 1976). However, the process whereby <strong>representation</strong>sserve <strong>to</strong> defend identity is not an intrapersonal one, as certain readings of OBwould see the optimism or sense of invulnerability that manifests in relation <strong>to</strong> threat(see Taylor et al., 1992). When risks are encountered, individuals draw—oftennot consciously—on ways of thinking that have always been, and continue <strong>to</strong> be,acceptable <strong>to</strong> the groups with which they identify. When such events are objectified,groups favour the images, symbols and/or metaphors compatible with in-group values.So the identity positioning of the represen<strong>to</strong>r determines the vision held of a newthreat. Different groups ascribe <strong>to</strong> different <strong>representation</strong>s of risks in accordance withthe identities that require protection.SRT emphasizes how thinking that develops in relation <strong>to</strong> risks is a way of coping,following Moscovici’s (1976) supposition that all thinking is a means of solving psychicor emotional tensions, a compensation <strong>to</strong> res<strong>to</strong>re inner stability. Wagner andKronberger (2001) juxtapose two types of coping in the face of potential danger.Material coping includes the activities of scientists, engineers and politicians undertaken<strong>to</strong> reduce health hazards and <strong>to</strong> control ecological risks. This involves technicalactions, political decisions and legislation. However, symbolic coping involves theappropriation of the novel and unfamiliar in order <strong>to</strong> make it intelligible and communicable.Social <strong>representation</strong>s reflect the endeavour <strong>to</strong> cope with threat, at a symboliclevel, and a splitting defence against anxiety is often manifest in them.Methodological challenges posedThe processes and motivations involved in <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong> formation are notsimple <strong>to</strong> discern empirically. Major methodological challenges are posed by the shift<strong>to</strong> identity-based, emotional and symbolic facets of human thinking. Once one assumesthat the fac<strong>to</strong>rs that forge readings of risk are not necessarily located in the privateknowledge of individuals, self-report data cannot be taken at face value. Individuals’responses <strong>to</strong> scale items cannot be used as a sole measure, as generally occurs in manymore mainstream models of risk ‘<strong>perception</strong>’. The studies reviewed above demonstratethat triangulation (see Flick, 1992), in terms of exploring ideas that reside in structuresoutside of individual minds (e.g. in the mass media, scientific publications and textbooks),as well as those that emerge from (closed and open-ended) surveys, andinterviews (with individuals and focus groups), has emerged as a key mechanism forensuring that both individual thinking and its context are sampled. The goal is <strong>to</strong>observe the transformations that occur as knowledge circulates between the differentrealms and <strong>to</strong> discover how particular group members make meaning of risk messages,and what functions these meanings have for them.10 Social <strong>representation</strong> is motivated by other fac<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong>o. While not centrally concerned with the ideological function of<strong>representation</strong>, it is recognized that at the same time as protecting self and in-group vulnerability <strong>to</strong> risks, the chosen<strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong> maintains the status of certain groups in a society. Of course, in maintaining the dominance ofcertain groups, the SR can con ict with the identity protective function: Those people who are members of ‘out-groups’ nd themselves at the receiving end of projective material that potentially can ‘spoil’ their identity (see Joffe, 1995). Afurther motivation is that the <strong>representation</strong> fosters solidarity within groups and facilitates communication between groupmembers. Kaes (1984) indicates that shared <strong>representation</strong>s provide a nucleus of identication for the group, allowing it<strong>to</strong> distinguish itself from its out-groups.

Perception of risk 67Like more mainstream risk studies, SRT research still suffers from over-reliance onconsciously accessible data. However, empirical methods for examining the implicit,symbolic content of thought are being developed. Attention is being paid <strong>to</strong> images,and <strong>to</strong>ols such as word-association tasks (e.g. see Wagner et al., 1996), participan<strong>to</strong>bservation and drawings are used. These provide useful counterpoints <strong>to</strong> self-reportdata. The added value of such methods is evident in aspects of Jodelet’s (1991) study ofmental illness that emphasize the importance of the workings of the response <strong>to</strong> threatthat have not reached a verbal level but are nevertheless informative of action. Herparticipant observation revealed that when mentally ill lodgers stayed with hostfamilies, their eating utensils and clothing were washed separately from those belonging<strong>to</strong> the hosts. This indicates the existence of a <strong>representation</strong> of mental illness ascontagious. Yet the interview material was more consistent with modern medicine’sunderstanding of mental illness, which does not refer <strong>to</strong> contagion. Fears of contagionwere expressed via the keeping apart of the belongings of the lodgers through ‘wordlessthought’ but not consciously thought about or, at least, mentioned in the interviews.The gulf between the meanings that emerge from the participant observationand interviews points <strong>to</strong> the importance of utilizing multiple methods. The gulf mayreflect the presence of self-presentation in the interviews, but, as plausibly, it mayindicate that the hosts hold complex, contradic<strong>to</strong>ry ideas about mental illness (Bauer &Gaskell, 1999).A focus on the non-verbal realm highlights that when self-report data are used alone,they do not provide a sufficiently valid account of risk-related thinking. Researchersneed <strong>to</strong> sample conscious and non-conscious material in naturally occurring <strong>social</strong>networks if they are <strong>to</strong> ascertain whether patterns of identity protective <strong>representation</strong>exist.Implications of a <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s approach for the psychology of riskIn itself, SRT represents a critique of models of ‘<strong>perception</strong>’ in the risk sphere, wherepeople are regarded as erroneous perceivers, and their patterns of <strong>perception</strong> aggregatedin order <strong>to</strong> establish nomothetic laws (see Lamiell, 1998). In place of this, manySRT-driven studies focus on commonalties across groups of persons in particular, howthey make sense of particular risk issues, and how their meaning structures evolve.SRT’s goal is <strong>to</strong> discern meaning, rather than <strong>to</strong> perform ‘cognitive algebra’. Identityprocesses largely influence the content of these meaning systems. For example, interms of meanings of ‘potential dangers’, <strong>representation</strong>s may defend the represen<strong>to</strong>rfrom the anxiety that they evoke. A motivation <strong>to</strong> protect the inner space underpinsconcepts wherein ‘others’ become linked with danger by absorbing that which isregarded as morally reprehensible.In addition <strong>to</strong> the meaning-based and emotive foci, SRT also injects in<strong>to</strong> risk psychologya concern with methods for grasping the contextual fac<strong>to</strong>rs that feed thecontent of individual belief structures. This differs substantially from the intrapersonalfocus of much psychological risk research. Menacing imagery in the mass media,for example, feeds objections <strong>to</strong> many biotechnological risks, despite any positiveaccounts conveyed in written form (see Gaskell et al., 1999).In the place of attempting <strong>to</strong> track and <strong>to</strong> understand what the cognitive traditionlabels ‘heuristics and biases in decision-making’, SRT studies human thoughts in themselves,without reference <strong>to</strong> an ideal. It is presumed that different pockets of sharedknowledge, in different groups, delimit what each group member sees as ‘rational’ (see

68 Hélène JoffeWagner, 1993). By way of contrast <strong>to</strong> the set of individualist assumptions contained inthe mainstream Anglo-Saxon models of risk psychology, where human thought processesare studied as if they arise within, and lie exclusively inside, individual minds,the <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>al approach proposes that human thought is relational at root.Explanations and judgments are not constructed within individual minds but in the‘unceasing babble’, the ‘permanent dialogue’ that people have with each other(Moscovici, 1984b) and with institutions.This paper has demonstrated that the link between individual thought and broaderinstitutional forces, such as those of science and of the mass media, is crucial <strong>to</strong> anunderstanding of the psychology of risk. In making the shift from cognition <strong>to</strong> the<strong>social</strong> transmission of ideas, and <strong>to</strong> the emotional and symbolic realms, the approachabandons reliance upon the respected experimental and survey methods. SRT’s dualfoci on group-based, and internal, rationality dictates that the contents of both the<strong>social</strong> context and individual minds be sampled. Consequently, triangulation, in termsof drawing material from both the <strong>social</strong> context and from individual minds, hasemerged as a key aspect of the method of many <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>al studies.ConclusionThe paper has focused on what SRT can contribute <strong>to</strong> the study of responses <strong>to</strong> risks.Its scope has been <strong>to</strong> emphasize those elements of the readings of risks that havebeen dormant (or seen as epi-phenomena) in cognitively-driven risk psychology. Thecontributions offered are summarized below.A key revelation is the lack of focus on the specific meaning made of one or otherrisk, in mainstream risk research. Instead of concentrating on intrapersonal cognitiveprocesses and their limitations, SRT emphasizes the specific, complex content ofcommon-sense thinking regarding particular risks. The mental illness example demonstratesthat the content of the response <strong>to</strong> risk is not only complex but often containscontradic<strong>to</strong>ry elements, which are difficult <strong>to</strong> discern by way of scales and surveyitems. SRT’s interest is not in whether a response <strong>to</strong> risk is correct or erroneous. Theconcern is not with whether it is false, weak, biased, or in any other way deficient(Bauer & Gaskell, 1999). Rather, the raison d’être of the theory lies in why and howsociety creates <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s, and the common sense that evolves from this.People construct risks through lenses tinged with elements of group attachment and ofthe experiences of their in-groups and selves, in terms of both the contemporaryimagery they are exposed <strong>to</strong> and past misfortunes. These elements do not dis<strong>to</strong>rt a ‘realrisk’. Rather, they are the ‘reality’ in the minds of those who look upon the risks.The <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong> is a relatively consensual or shared understanding within agroup, which is forged by way of communicative processes, and also facilitates them.As such, a <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s perspective addresses one of Douglas’ (1994) keyproblems with the risk field: that it fails <strong>to</strong> take in<strong>to</strong> account ‘intersubjective mobilisationsof belief’ (p. 40). SRT is uniquely positioned <strong>to</strong> address this. The level of examinationin SRT is the ‘we’ contained in the thinking of the ‘I’. The ‘we’ aspect is moredeveloped in the broader <strong>social</strong> sciences. Yet SRT, in focusing on the media–mind link,as well as anchoring and objectifying, makes a distinctive contribution <strong>to</strong> risk theory bypositing how the ‘we’ enters in<strong>to</strong> and constructs the <strong>representation</strong>s of the ‘I’. The linkbetween group and individual identity, on the one hand, and the <strong>representation</strong> of risk,on the other hand, offers a rich area for future investigation.

Perception of risk 69A further important aspect of the content of risk-related thought is its link <strong>to</strong> affect,and this provides an ongoing area of investigation in the SRT sphere. Emotions are notabsent from the cognitive theories. Taylor et al. (1992) obliquely acknowledge a rolefor the emotional dimension, such as heightened anxiety, and the mobilization of OBas a defence against it. In addition, the dimension of ‘dread’ in the psychometric workon risk (see Slovic, 2000b) speaks <strong>to</strong> a sense underpinned by emotion. However, it isonly in recent years that affect has been given a role in the risk-<strong>perception</strong> field.The paper has shown that sec<strong>to</strong>rs of the cognitive literature have also recentlybecome engaged with the symbolic and <strong>social</strong> aspects of the apprehension of risks.This results, in part, from awareness of the host of challenges <strong>to</strong> earlier cognitivetheory. The changes are reflected in the title of a recent review (Schwarz, 2000) ofwhere the <strong>social</strong> judgment and attitude field as a whole is heading: ‘Social judgementand attitudes: warmer, more <strong>social</strong>, and less conscious’. While the content of thereview reflects a less radical shift than the title implies 11 , these directions are certainlyevident in the field. Yet three key ways in which the new direction in the cognitiveliterature still differs radically from the SRT literature can be distinguished.First, the extant idea that emotions are dis<strong>to</strong>rters of cognition differentiates this newwave of literature in the risk <strong>perception</strong> field from the SRT approach, which proposesplural facets of the response <strong>to</strong> risk rather than dis<strong>to</strong>rted, as opposed <strong>to</strong> non-dis<strong>to</strong>rtedways. Second, when <strong>social</strong> fac<strong>to</strong>rs, such as ‘worldview’, are taken on board in the moremainstream literature, they are slotted in<strong>to</strong> a regression equation <strong>to</strong> predict ‘risk<strong>perception</strong>’. A rich explanation of the complexity of what people feel and think aboutrisks may be better theorized without reliance on a reductive typology. Third,<strong>representation</strong> is treated as a static element of cognitive organization in the newercognitive theories, while within SRT, the concept ‘<strong>representation</strong>’ is imputed withdynamism since it refers as much <strong>to</strong> the process through which <strong>representation</strong>s areelaborated (i.e. by way of transformations of material as it is mediated <strong>to</strong> lay peoplefrom the expert realm, and their anchoring and objectification) as it does <strong>to</strong> thestructures of knowledge that are established. Slovic and his colleagues have introduced<strong>to</strong> the risk field many dimensions for which rich theorization already exists in theSRT realm.In challenging mainstream risk psychology with findings that do not take the naturalsciences as their yardstick of good science, the unscientific, the ‘soft’, threatens <strong>to</strong>invade a tradition that works hard <strong>to</strong> conform <strong>to</strong> particular scientific aspirations. Thisproposition can be viewed in at least one of two ways. Either one recognizes that ideasgenerated outside predictive models are valuable for increasing understanding ofphenomena, but provide less ‘evidentiary weight’ (see Westen, 1998), or one adoptsthe stance that, contrary <strong>to</strong> beliefs held within and outside the scientific community,not just one scientific method exists (see Boulding, 1980). Science strives <strong>to</strong> developmethods that correspond <strong>to</strong> different epistemological fields. Within the latter vision,<strong>social</strong> and natural scientific approaches are of equal value. The <strong>social</strong>-<strong>representation</strong>s11 Schwarz (2000) states that the focus on the computer metaphor in terms of the encoding, s<strong>to</strong>rage and retrieval ofinformation (i.e. information processing) not only fostered concentration on individuals as isolated information processors,but ‘did not invite attention <strong>to</strong> subjective experiences and emotional and motivational inuences’ (p. 150). Despite hiscritique of this vision, his notion of where the eld is heading is not radically different. The metaphor he uses <strong>to</strong> sum upthe shift in<strong>to</strong> these realms is of the human as a ‘motivated tactician’. He says, of this new characterization, that ‘thismetaphor does not question the truism that humans are information processors. It merely highlights that informationstands in the service of, and is tuned <strong>to</strong> meet, the individual’s goals and needs’ (p. 151) (emphasis in original). In thisvision, humans are still essentially information processors, rather than meaning-makers.

70 Hélène Joffeapproach pursues its quest for understanding the complexity of human meaningmakingsystems by utilizing appropriate, scientifically rigorous methods. Logicalpositivism is useful for testing certain circumscribed hypotheses. Yet when the task is<strong>to</strong> discern how and what people feel and think when faced with the plethora of riskspresented <strong>to</strong> them daily, it may be useful <strong>to</strong> avoid methodola<strong>to</strong>ry: ‘a combination ofmethod and idolatry, <strong>to</strong> describe a preoccupation with selecting and defendingmethods <strong>to</strong> the exclusion of the actual substance of the s<strong>to</strong>ry being <strong>to</strong>ld.’ (Janesick,1994, p. 215)AcknowledgementsI would like <strong>to</strong> thank the three reviewers, as well as Steve Reicher and David Green fortheir excellent suggestions regarding earlier versions of this paper. I also acknowledge thecontribution of the British Academy <strong>to</strong> this paper.ReferencesAlhakami, A., & Slovic, P. (1994). A psychological study of the inverse relationship betweenperceived risk and perceived benefit. <strong>Risk</strong> Analysis, 14, 1085–1096.Bauer, M. W., & Gaskell, G. (1999). Towards a paradigm for research on <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s.Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 29, 163–186.Beck, U. (1986/1992). The risk society: Towards a new modernity. London: Sage.Beck, U. (1996). <strong>Risk</strong> society and the provident state. In S. Lash, B. Szerszynski & B. Wynne(Eds.), <strong>Risk</strong>, environment and modernity: Towards a new ecology (pp. 27–43). London:Sage.Bhaskar, R. (1979). The possibility of naturalism: A philosophical critique of the contemporaryhuman sciences. Brigh<strong>to</strong>n, UK: Harvester.Boulding, K. (1980). Science: Our common heritage. Science, 207, 831–826.Brown, J., Chapman, S., & Lup<strong>to</strong>n, D. (1996). Infinitesimal risk as public health crisis: Newsmedia coverage of a doc<strong>to</strong>r–patient HIV contact tracing investigation. Social Science andMedicine, 43, 1685–1695.Chamberlain, K. (2000). Methodolatry and qualitative health research. Journal of HealthPsychology, 5, 285–296.Concerted Action Group (1997). Europe ambivalent on biotechnology. Nature, 387, 845–847.Corner, J. (1991). Meaning, genre and context: The problematics of ‘public knowledge’ in thenew audience studies. In J. Curran & M. Gurevitch (Eds.), Mass media and society (pp. 267–284). London: Edward Arnold.Corner, J., Richardson, K., & Fen<strong>to</strong>n, N. (1990). Nuclear reactions: Form and response inpublic issue television. London: Libbey.Douglas, M. (1994). <strong>Risk</strong> and blame: Essays in cultural theory. London: Routledge.Duveen, G. (2000). Introduction: The power of ideas. In S. Moscovici & G. Duveen (Eds.), Social<strong>representation</strong>s (pp. 1–17). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Fife-Shaw, C. (1997). Commentary on Joffe (1996) AIDS research and prevention: A <strong>social</strong><strong>representation</strong>s approach. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70, 65–73.Finucane, M. L., Alhakami, A., Slovic, P., & Johnson, S. M. (2000). The affect heuristic injudgements of risks and benefits. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 13, 1–17.Flick, U. (1992). Triangulation revisited: Strategy of validation or alternative? Journal for theTheory of Social Behaviour, 22, 175–197.Gaskell, G., Bauer, M., Durant, J., & Allum, N. (1999). Worlds apart? The reception of geneticallymodified foods in Europe and the U.S. Science, 285, 384–387.Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Perception of risk 71Heine, S. J., & Lehman, D. R. (1995). The cultural construction of self-enhancement: Anexamination of group-serving biases. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72,1268–1283.Herzlich, C., & Pierret, J. (1989). The construction of a <strong>social</strong> phenomenon: AIDS in the Frenchpress. Social Science and Medicine, 29, 1235–1242.Hews<strong>to</strong>ne, M., & Augoustinos, M. (1998). Social attributions and <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s. InU. Flick (Ed.), The psychology of the <strong>social</strong> (pp. 60–76). Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress.Irwin, A., & Wynne, B. (1996). Conclusions. In A. Irwin & B. Wynne (Eds.), Misunderstandingscience: The public reconstruction of science and technology (pp. 213–221). Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.Janesick, V. J. (1994). The dance of qualitative research design: Metaphor, methodolatry, andmeaning. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research(pp. 209–219). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Jodelet, D. (1991). Madness and <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s. Hertfordshire: Harvester-Wheatsheaf.Joffe, H. (1995). Social <strong>representation</strong>s of AIDS: Towards encompassing issues of power. Paperson Social Representations, 4(1), 29–40.Joffe, H. (1996a). AIDS research and prevention: A <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>al approach. BritishJournal of Medical Psychology, 69, 169–190.Joffe, H. (1996b). The shock of the new: A psycho-dynamic extension of <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>stheory. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 26, 197–219.Joffe, H. (1997). Juxtaposing positivist and non-positivist approaches <strong>to</strong> <strong>social</strong> scientific AIDSresearch: Reply <strong>to</strong> Fife-Schaw’s commentary. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70,75–83Joffe, H. (1999). <strong>Risk</strong> and ‘the other’. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Joffe, H., & Haarhoff, G. (2002). Representations of far-flung illnesses: The case of Ebola inBritain. Social Science and Medicine, 54, 955–969.Kaes, R. (1984). Representation and mentalisation: <strong>From</strong> the represented group <strong>to</strong> thegroup process. In R. M. Farr & S. Moscovici (Eds.), Social <strong>representation</strong>s (pp. 361–377).Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Kahneman, D., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (1982). Judgement under uncertainty: Heuristics andbiases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Kim, U. (1999). After the ‘‘crisis’’ in <strong>social</strong> psychology: The development of the transactionalmodel of science. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2(1), 1–19.Klein, W. & Radcliffe, N. (1999). Generalised and risk-specific unrealistic optimism and theirrelation <strong>to</strong> the processing of health information. In 13th Conference of the European HealthPsychology Society, 1–3 Oc<strong>to</strong>ber.Kleinhesselink, R. R., & Rosa, E. A. (1991). Cognitive <strong>representation</strong>s of risk <strong>perception</strong>s: Acomparison of Japan and the United States. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 22, 11–28.Lamiell, J. T. (1998). ‘Nomothetic’ and ‘idiographic’: Contrasting Windelband’s understandingwith contemporary usage. Theory and Psychology, 8(1), 23–38.La<strong>to</strong>ur, B., & Woolgar, S. (1979). Labora<strong>to</strong>ry life: The <strong>social</strong> construction of scientific facts.Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.McKenna, F. P. (1993). It won’t happen <strong>to</strong> me: Unrealistic optimism or illusion of control?British Journal of Psychology, 84, 39–50.Marcus, H. R., & Plaut, V. C. (2001). Social <strong>representation</strong>s: Catching a good idea. In K. Deaux &G. Philogene (Eds.), Representations of the <strong>social</strong> (pp. 183–189). Oxford: Blackwell.Markova, I., & Wilkie, P. (1987). Representations, concepts and <strong>social</strong> change: The phenomenonof AIDS. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 17, 389–409.Michael, M. (1996). Ignoring science: Discourses of ignorance in the public understandingof science. In A. Irwin & B. Wynne (Eds.), Misunderstanding science: The publicreconstruction of science and technology (pp. 107–125). Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress.

72 Hélène JoffeMoscovici, S. (1976). La psychanalyse, son image et son public. Paris: Presses Universitaires deFrance.Moscovici, S. (1984a). The myth of the lonely paradigm: A rejoinder. Social Research, 51,939–969.Moscovici, S. (1984b). The phenomenon of <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s. In R. M. Farr & S. Moscovici(Eds.), Social <strong>representation</strong>s (pp. 3–70). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Moscovici, S. (1998). The his<strong>to</strong>ry and actuality of <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s. In U. Flick (Ed.), Thepsychology of the <strong>social</strong> (pp. 209–247). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Moscovici, S. (2000). Ideas and their development: A dialogue between Serge Moscovici andIvana Markova. In S. Moscovici & G. Duveen (Eds.), Social <strong>representation</strong>s (pp. 224–286).Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Moscovici, S. (2001). Why a theory of <strong>social</strong> <strong>representation</strong>s? In K. Deaux & G. Philogene (Eds.),Representations of the <strong>social</strong> (pp. 8–35). Oxford: Blackwell.Myers, L., & Brewin, C. (1996). Illusions of well-being and the repressive coping style. BritishJournal of Social Psychology, 35, 443–457.Myers, L., & Renolds, D. (2000). How optimistic are repressors? The relationship betweenrepressive coping style, controllability, self-esteem and comparative optimism for healthrelatedevents. Psychology and Health, 15, 677–687.Oatley, K. G. (1996). Emotions, rationality and informal reasoning. In J. Oakhill & A. Garnham(Eds.), Mental models in cognitive science: Essays in honour of Phil Johnson-Laird(pp. 175–196). Hove, UK: Psychology Press.Peeters, G., Cammaert, M-F., & Czapinski, J. (1997). Unrealistic optimism and positive–negativeasymmetry: A conceptual and cross-cultural study of interrelationships between optimism,pessimism and realism. International Journal of Psychology, 32, 23–34.Pidgeon, N., Hood, C., Jones, D., Turner, B., & Gibson, R. (1992). <strong>Risk</strong> <strong>perception</strong>. In Repor<strong>to</strong>f a Royal Society Study Group <strong>Risk</strong>: Analysis, <strong>perception</strong> and management (pp. 89–134).London: The Royal Society.Potter, J., & Edwards, D. (1999). Social <strong>representation</strong>s and discursive psychology: <strong>From</strong>cognition <strong>to</strong> action. Culture and Psychology, 5, 447–458.Potter, J., & Wetherell, M. (1998). Social <strong>representation</strong>s, discourse analysis, and racism. InU. Flick (Ed.), The psychology of the <strong>social</strong> (pp. 138–155). Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress.Renn, O. (1998). Three decades of risk research: Accomplishments and new challenges. Journalof <strong>Risk</strong> Research, 1(1), 49–71.Rogers, R. W. (1975). A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change.Journal of Psychology, 91, 93–114.Rosens<strong>to</strong>ck, I. M. (1974). His<strong>to</strong>rical origins of the health belief model. Health EducationMonographs, 15, 328–335.Schwartzer, R. (1992). Self-efficacy in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviours:Theoretical approaches and a new model. In R. Schwartzer (Ed.), Self-efficacy: Thoughtcontrol of action (pp. 217–242). Washing<strong>to</strong>n, DC: Hemisphere.Schwarz, N. (2000). AGENDA 2000—Social judgements and attitudes: Warmer, more <strong>social</strong> andless conscious. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30, 149–176.Sheeran, P., Abraham, C., & Orbell, S. (1999). Psycho<strong>social</strong> correlates of heterosexual condomuse: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 90–132.Slovic, P. (1997). Trust, emotion, sex, politics and science: Surveying the risk-assessment battlefield.In M. Bazerman, D. Messick, A. Tenbrunsel, & K. Wade-Benzoni (Eds.), Environment,ethics and behaviour (pp. 277–313). San Francisco: New Lexing<strong>to</strong>n Press.Slovic, P. (Ed.). (2000a). <strong>Risk</strong> <strong>perception</strong>. London: Earthscan.Slovic, P. (2000b). Perceived risk, trust and democracy. In T. Connolly, H. R. Arkes, &K. R. Hammond (Eds.), Judgement and decision making: An interdisciplinary reader(pp. 500–513). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.