Making Mangrove - Seameo-SPAFA

Making Mangrove - Seameo-SPAFA

Making Mangrove - Seameo-SPAFA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

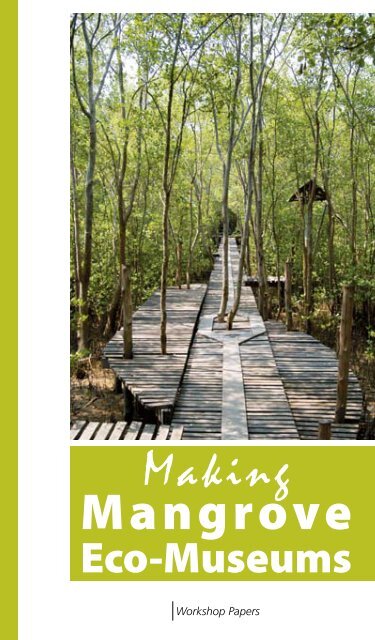

<strong>Making</strong><strong>Mangrove</strong>Eco-MuseumsWorkshop Papers

ISBN 978-974-7809-37-4SEAMEO-<strong>SPAFA</strong>81/1 Sri Ayutthaya Road,Samsen, Theves, Bangkok 10300THAILANDFax: (66) 2280 4030Website: www.seameo-spafa.orgE-mail: spafa@seameo-spafa.orgCo-ordinatorEan LeeAssistantsGirard BonotanTang Fu KuenTheera NuchpiamNipon Sud-NgamWanpen KongpoonWilasinee ThabuengkarnPhotographerNipon Sud-NgamPrinterAmarin Printing and Publishing Co., Ltd.Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication DataExtracts of papers and presentations given atworkshop on making mangrove eco-museumsBibliographical references<strong>Mangrove</strong> forests-Ecomuseums-marine ecologycommunityenvironmental conservationViews expressed in this publication are those of theauthors, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions orpolicies of <strong>SPAFA</strong>.C O N T E N T S5 Introduction13 The Bangpakong <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-MuseumProjectPisit Charoenwongsa20 Setting Up Nature Education Centresand Interpretation ProgrammesNoor Azlin Yahya37 Ha Long Bay – A World HeritageHoang Thi Ngoc Ha and Hguyen Thu Huyen59 The Site Development of the <strong>Mangrove</strong>Forest, Tabon Cave ComplexWilfredo Vendivil and Ernesto B Toribio Jr74 Education Programming in Muzium NegaraJanet Tee Siew Mooi85 Coastal Community in the Kingdom ofCambodia (A Case Study on <strong>Mangrove</strong>Management)Ouk Vibol98 Water Culture and the Community – RaisingEnvironmental AwarenessKoh Lee Chew, Lim Han She and Shawn Lum119 Nature Centres for Wetland Conservationin MalaysiaNoor Azlin Yahya, Chong Mew Im andAzyyati Abd. Kadir132 Recommendations151 List of Participants

IntroductionRegional WorkshopChachoengsao, Thailand19-28 March 2007Organised by SEAMEO-<strong>SPAFA</strong>in collaboration with the Bangpakong BovornWitthayayon SchoolRiver and floraat Bangpakong,Chachoengsao<strong>Mangrove</strong>s support eco-systems ofbiological diversity, and are sources ofproductivity in terms of aquaculture,fisheries and forestry. The mangroveswamps provide aquatic nurseries(breeding ground for several types offish, shellfish and a wealth of marinelife forms); complex and diversewildlife habitats; shoreline stabilizationwhich protects coastal areas from severe wave damageand erosion; and also maintain the quality of coastalwaters (by trapping, immobilizing or absorbing heavymetals, pesticides and inorganic nutrients which wouldflow to the sea). With this understanding, establishingmuseums out of mangrove swamps contributes to theconservation and management of mangrove eco-systems.The museums also perform the role of disseminatinginformation that enhances public awareness andappreciation of the importance of mangroves. In thePhilippines, Vietnam and Thailand, mangrove plantationsare grown in coastal regions for the ecological, social andeconomic benefits they provide to coastal fisheries andcommunities, and the establishment of eco-museums inmangrove swamps, which exist in most of the countries inSoutheast Asia, are of immense benefit to the region.Between 19 and 28 March 2007, SEAMEO-<strong>SPAFA</strong>organised a Regional Workshop on <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong>an Eco-museum, hosting twenty-five participants from

IntroductionIntroductiondifferent parts of Southeast Asia, for about ten days neara mangrove (by the Bangpakong Bovorn Witthayayonschool) in the Chachoengsao province of Thailand. Aspart of the workshop, the participants made presentations,discussed, explored the mangrove, and co-operated infinding ways to improve the Bangpakong mangrovemuseum, where the workshop was conducted.The workshop involved a multidisciplinary groupof museum professionals, environmental and marinescience experts, architects, artists, teachers andstudents from nine Southeast Asian countries (the listof participants is on page 151).Entrance tothe Bangpakong<strong>Mangrove</strong>Eco-Museumstabilization which protects coastal areas from severwave damage and erosion; and the role of coastalwaters.Beyond the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand,where mangrove plantations are grown in coastal regionsfor the ecological, social and economic benefits (tocoastal fisheries and communities), the establishment ofeco-museums in mangrove swamps, is of immensesignificance to most of the countries in SoutheastAsia.As the workshop was held at the BangpakongBovorn Witthayayon School, which has developed itsown eco-museum in the mangroves, the workshopparticipants also aimed at helping the school improveThey have been gathered together to discuss andassist one another in achieving the objectives of promotingthe establishment of eco-museums in mangrove swamps;increasing interest and understanding among museumpersonnel and other professionals in the conservationand management of mangrove eco-systems; andsupporting research and sustainable management,rational utilization and rehabilitation of mangroveenvironments.The workshop helped to furtherthe appreciation that mangrovessupport eco-systems of biologicaldiversity, and are sources ofproductivity in terms of aquaculture,fisheries and forestry. With sessionsthat touched on aquatic breedingground for fish, shellfish and othermarine life forms, participants learned about thecomplex and diverse wildlife habitats; shorelineArrival of workshopparticipantsWorkshopdiscussions atthe BangpakongBovorn WitthayayonSchoolthe management of its museum and mangrove ecosystems.At the end of the workshop, and having hadspent more than a week together, the participantsexpressed genuine affection for each other as well asgratitude for the experience of having worked hadplayed together, with a great spirit of co-operation andmany moments of fun. Among the recommendationsin concluding the workshop were a call for the museumto include a narrative in museum displays and a siteplan in the vicinity; establish a laboratory for scientificstudy; produce a mini guide booklet; improve thedrainage and landscape; and develop the localcommunity. <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums

IntroductionIntroductionT he workshop commenced with a speech given byDr. Pisit Charoenwongsa, SEAMEO-<strong>SPAFA</strong> Director,to an audience which included H.E. Professor Dr.Wichit Srisa-an, Minister of Education of Thailand,Director and staff of Bangpakong Bovorn WitthayayonSchool, President of the School Alumni Association,distinguished delegates and participants.Dr. Pisit remarked that it was an honour that theguests and participants accepted the invitation to gracethe opening ceremony of our workshop.He proceeded to inform about theschool which was hosting the event, andalso SEAMEO-<strong>SPAFA</strong> and its mission,which was to “work with the school toraise awareness of the importance of themangrove as one of the very many typesof educational resources”.He said that “whatever you havenear and in your school compound canbe made teaching and learningmaterials. We believe in the concept of‘interconnectedness’, just as scientistshave elaborated that ‘everything isconnected to everything else’.”As for the history of the museumof the school, it was planted in 1975 with the initiativeof the then Director Thamnoon Wisaichosu, and wasnurtured to become, in the first place, a study area ofenvironment for students. It has subsequently beenimproved by all school administrators and has won manyenvironmental awards so far.Dr. PisitCharoenwongsa,and staff of theschool receive H.E.Prof. Dr. WichitSrisa-an, Ministerof Education,ThailandDr. PisitCharoenwongsa,SEAMEO-<strong>SPAFA</strong>DirectorIt was the school’s AlumniAssociation’s Museum Committee,chaired by H.E. Professor Wichit Srisanan,that conceived the idea of developingthe school area into a museum andcentre for educational and recreationalpurposes. The museum was officiallyopened on 17 November 2001.Dr. Pisit took the opportunity to elaborate on<strong>SPAFA</strong>’s regional programmes that focus on the followingareas: archaeology, fine arts, visual arts, art education,architecture, museology, performing arts, culturalresource management, cultural heritage management,and tourism.SEAMEO-<strong>SPAFA</strong> is focused on (1) longer-termsustainable programming and (2) working in partnership,with the belief that the most effective results are obtainedfrom such endeavours, through combining resources– not just funds but people also – and avoidingduplicating efforts. Operating under the motto ofEducating for Sustainable Development through CulturalResource Management, the Centre has identifiedcommunity involvement as the real or key issue thatneeds attention because of the emphasis on peopleand their relationship with conservation and heritage.Dr. Pisit said that the Centre firmly believes that tosafeguard heritage and to develop programmes thatIn 1998, after the celebration of the schoolcentennial, a working group led by H.E. ProfessorDr. Wichit Srisan-an was set up to plan for theestablishment of a museum in the school compoundas an integrated learning centre on nature and cultureby making use of the mangrove as educationalresources first and then extending to cover otheractivities beyond mangrove use.Minister ofEducation Prof Dr.Witchit Srisa-anaddresses workshopparticipants <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums

IntroductionIntroductionwill be sustainable, “they must be inclusive, i.e. theymust involve all interested parties. This is why we are sopleased to be involved in this community project hereat Bangpakong and to see the active participation ofthe local community”.He commented that Southeast Asia is rich inresources and that “we are aware these resources requirewise management. To make wise management a realitywe try to maximize the benefits of networking, buildingrelationships, learning from each other, and developingstrong mutually beneficial partnerships”.In conclusion, Dr. Pisit thanked the audience,and said that the Centre believes that over the comingdays, the workshop would indeed help to improveupon ‘wise-management’ strategies, directly benefitthe museum at the school, and also the work of allparticipants from around the region.Following the SEAMEO-<strong>SPAFA</strong> Director’s openingremarks, H.E. Professor Dr. Wichit Srisan-an, theMinister of Education, Thailand, was invited toaddress the audience.He began by saying that it was a great pleasureto welcome the participants and all to the workshophere in his home province of Chachoengsao, and thatit was indeed reassuring to see so many delegatesfrom Southeast Asia as this reaffirms the importanceattached to the careful and resourceful managementof mangroves.H.E. Professor Dr. Wichit said that when wethink of mangroves, we think of aquatic nurseriesand complex and diverse wildlife habitats. “As weknow, mangroves support eco-systems of biologicaldiversity, and are sources of productivity in termsof aquaculture, fisheries and forestry. Another veryimportant aspect of mangroves is shorelinestabilization as they can help protect coastal areasfrom severe wave damage and erosion. Sadlyit took the tsunami of 2004 to really highlightthis fact. The establishment of museums out of<strong>Mangrove</strong>s supporteco-systems ofbiological diversitymangrove swamps can contribute to the conservationand management of mangrove eco-systems”.In Thailand alone, he said that the destruction ofmangroves must be stopped, pointing out the latestsurvey of the United Nations Environment Programme(UNEP) which estimated that mangrove coverage hasshrunk from 1.14 million rai in 1961 to 446,062 rai in2006 as a result of encroachment for shrimp farming,illegal logging, and coastal erosion.He added that eco-museums can disseminateinformation to raise public awareness and appreciation ofthe importance of mangroves, and the local communitiesliving near mangroves become the guardians andconservators of the mangrove plantations themselves.This is the idea at Bangpakong. As well aspromoting community involvement, there is alsothe unique opportunity to directly reach youthsas the Bangpakong <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museumis situated within eleven hectares of land and mangrovesthat also houses the Bangpakong Bovorn Witthayayonsecondary school.H.E. Professor Dr. Wichit informed thatthe school’s alumni association, which includesDr. Pisit and himself as members, has been advocatingthe development and establishment of an eco-museumas well as a water culture and sports centre forthe school. He remarked that the school has beenfortunate to have SEAMEO–<strong>SPAFA</strong>’s regular technicaland academic assistance on this matter.As the first regional workshop to be held at theschool, he believed that the knowledge and experience ofthe participants would generate “a tangible outcome thatwill be the better management of the Bangpakongmangrove eco-systems and the improved presentationand display of our mangrove eco-museum ‘exhibits’”.He wholeheartedly agreed with the SEAMEO-<strong>SPAFA</strong> Director that the mangrove of the schoolrepresents one of a number of types of resources for10 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 11

IntroductionThe Bangpakong<strong>Mangrove</strong>Eco-Museum Projecteducation, and he encouraged the use of it as an example ofresources a school or community may have available in plentythat can be used for educational purposes for all.H.E. Professor Dr. Wichit wished all the best inthe endeavour over the days, and looked forward tostudying the outputs and recommendations arising fromthe workshop.Following the Minister’s key address, workshoppresentations began. After each session, a period ofdiscussion was added in which all the participants freelyshared their ideas and thoughts in an informal and relaxedatmosphere.The 10-day workshop also included tours of themangrove Eco-Museum at the Bangpakong BovornWitthayayon School; short play sketches created andperformed by the participants touching on the issuesrelating to wet lands and the environment; researchcompilation of information, and working with thestudents and teachers; an exhibition or mangroves andproducts made by the school; and leisure trips to anancient market in Chachoengsao Province, as well asPattaya Beach.Visitors on a tourof the schoolmangroves/eco-museumPisitCharoenwongsaWalkways in theschool mangrovehabitatM any schools have museums or study collections butfew schools have mangroves. The Bangpakong BovornWittayayon, a secondary school in Thailand, has theuniqueness of being the only school with both themangrove and a museum, the Bangpakong <strong>Mangrove</strong>Eco-Museum.The school develops the museum as a paramountmeans of preserving and cultivating appreciation of theenvironment, and it is perhaps the first of its type inSoutheast Asia.When we think of museums, we think of a group ofbuildings constructed to keep or display objects ofinterest. The Bangpakong Bovorn Wittayayon schoolchose to present a different concept of museum, onewhich is not confined to specialists.The concept is based on the belief that everything canbe made into a museum, and thus it is possible for thegeneral public to build their own museum the way theythink is good for education.12 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums

The Bangpakong <strong>Mangrove</strong>Eco-Museum ProjectPisit CharoenwongsaThe Concept of Eco-Museum“Eco-Museum” may seem to be a new term and type ofmuseum, but the concept is not. It is believed that theword emerged in 1971, and refers to a museum dedicatedto the environment (the idea was developed in Franceand Algeria).The eco-museum, evolving from the ‘open-air’ museummodel, is essentially made up of two inter-relatedmuseums – a spatial, unconfined, no-walls museum; andan enclosed temporal one. This kind of museum has arole in the education and culture of a very wide audience,and a community that can see its past, feel its present,and be involved in its future.The SchoolThe SEAMEO Regional Centre for Archaeology andFine Arts (<strong>SPAFA</strong>) has been working closely with theadministration and Alumni Association of the BovornWitthayayon School in developing and establishing theeco-museum, and water culture and sports centre amongthe community of the school and its vicinity of mangroveplantations, natural vegetation, and maritime habitat.The Bangpakong Bovorn Witthayayon School is locatedin Chacheongsao Province (to the east of Bangkok),Thailand. It is one of the ninety-two schools establishedin 1897 in what was then Siam during the reign of KingRama V (1868-1910).The school, with about eight hundred school childrenand eighty teachers, is like any other ordinary secondaryschool in Thailand. It is unique, however, in itscommitment to global environmental concerns. As theschool is situated amidst a mangrove environment, itsadministration finds the natural surrounding – coveringeleven hectares of land and mangroves – a resourcefularea to turn into a centre for environmental studies.<strong>SPAFA</strong> has been extending regular technical andacademic assistance to the school on the developmentof programmes relating to culture and nature, theBangpakong <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museum, and Water Cultureand Sports Centre.The Bangpakong EnvironmentSurrounding the Bovorn Witthayayon school and thecommunity are mangrove plantations, natural vegetation,and maritime habitat, and the Bangpakong River alongit. Primarily to preserve its pristine environment andculture, a community involvement project was initiated by<strong>SPAFA</strong> to create an eco-museum out of the area, and tomake it a model for museums that different to the usualstructure of huge closed buildings that house collectionsof objects of beauty, rarity, and antiquity.Students ofthe school guidevisitors throughthe mangroveareasInformationon resources inthe area14 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 15

The Bangpakong <strong>Mangrove</strong>Eco-Museum ProjectPisit CharoenwongsaThe Eco-Museum of <strong>Mangrove</strong>At the Bovorn Witthayayon school, the mangrove isthe museum. This outdoor museum represents botha museum and a classroom without walls, and is opento all who come for recreation or to study the natureand culture of the mangrove. The area concerned iscomposed of water, earth, and organisms, which includeplants and animals cohabitating with human beings, anddepending on each other for sustenance.The museum was conceived at an alumni meeting,chaired by Professor Wichit Srisa-an, when <strong>SPAFA</strong> CentreDirector proposed a new type of museum to showcasethe mangrove existing in the school environs. The AlumniAssociation’s Museum Committee, chaired by ProfessorWichit Srisa-an, conceived and proposed the idea ofdeveloping the school area into a museum and centrefor educational and recreational purposes.The eco-museum can accommodate between forty andfifty visitors at a time. There are elevated walkways overthe water, leading to the view and study of various kindsof plants, marine life-forms, a collection of donated boats,all of which provide the visitor substantial information forunderstanding type, physiography, and function.A school and anoutdoor museumEnvironmentalresources arestudied in classesThere is also a pavilion to display temporary and specialexhibitions that highlight the relevance of the mangroveor museum to the community, and raises awareness whilstinstilling a sense of communal protection for it. Scientificinformation is presented on signboards, in an easilycomprehensible format; and focuses on various aspectsof the mangrove community: the ecology of mangrovesand its importance, effective practices in managementof its preservation and restoration, and the uses andfunctions of mangroves (emphasizing the long-termyield to be obtained for the improvement in mangrovedwellers’ quality of life, for instance).What impresses is the way the school teachers andstudents have utilised the knowledge on the mangroveas a content in many school subjects. In the teaching ofThai language, for example, the mangrove is used as aninspiration for the writing of poems and the compositionof songs and music.As such, the mangrove is integrated in many lessons andsubjects, an advanced concept in education that is notconfined only to the curriculum set up by the Ministryof Education of the national government.In teaching science, for instance, the species of plantsand animals are presented in a direct and straightforward16 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 17

The Bangpakong <strong>Mangrove</strong>Eco-Museum ProjectPisit CharoenwongsaThe Bangpakongriverstill visible on the banks of the Chao Phraya River andassociated canals in Bangkok.People are alienating themselves from nature, and thisis partly a result of the notion that an urban lifestyle ismore attractive and prosperous than remaining tied torural traditions. In the modern age, the use and abuseof water has become a serious environmental concern.manner because they are found right on the schoolenvirons, as such, they have direct access to the speciesand their habitat. These lessons can expand into findingways to use the species for the food industry, medicalindustry, or use in dyeing.Interestingly, drawings found all over the eco-museumwere drawn by students of science instead of art students,showing how well the students understand the lessonsthrough their ecological surroundings.The mangrove initiated by the school administration asa centre for environmental studies has so far won manyenvironmental awards.Naturally, as an on-going project, the eco-museum isevolving, and is not entirely complete in its present formand state.The museum is presented as a centre of ecology thatcould be developed into many other related projects inthe future, such as on water culture and recreation.Water CultureWater is our prime commodity, and has influencedimportant economic and political aspects of life forcenturies. On a community level, water has affectedthe way in which people carried out business, howthey travelled, and even provided opportunities forrecreation.Communication and trade via rivers became factors inthe growth of early societies. A traditional way of life isDisplay of a royalstatement at themuseumA Royal ConcernThe concluding statement that follows is a royal statementmade by H.M. the King on 10 May 1991, which is ondisplay at the Bangpakong Eco-Museum, a place wherethe King’s message is poignantly relevant:“<strong>Mangrove</strong>s help sustain the ecosystem of coastalhabitats and the Gulf of Thailand. Yet it is now beingencroached upon and depleted by exploiters who careonly for their own benefits. Measures have to be takento protect, conserve, and increase mangrove acreage,especially of the Rhizophora (kongkang in Thai), whichis rather difficult to germinate because of the fluctuationof tide water. Concerned governmental agencies, suchas the Department of Forestry, the Department ofIrrigation and the Naval Hydrographic Department,should work together to find appropriate places togerminate the Rhizophora and thus sustain the growthof the mangrove.”18 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 19

Noor Azlin YahyaSetting Up NatureEducation Centresand InterpretationProgrammesNoor Azlin Yahya,Forest ResearchInstitute, Malaysia (FRIM)T he first presentation, ‘Setting Up Nature EducationCentres and Interpretation Programmes’, of theworkshop was made by Noor Azlin Yahya, ForestResearch Institute, Malaysia (FRIM) (full presentationon page 24-36). Dr. Yahya said that nature educationcan be defined as learning about nature and enhancingawareness of natural resources and conservation.Nature Education Centres (NEC) or eco-museumshave been built to serve as a base where one canfind the resources (human or material) to facilitatesuch learning activities. It is a place where a group ofpeople (ranging from school children to members of thepublic or a private company) learn about nature throughprogrammes designed to enhance their understandingand appreciation of the environment.One principle of an NEC is to use the surroundingenvironment or forest as a living classroom. Thepresenters added that NECs have to reflect the valueof the biodiversity of the surrounding area, as well asthe aspirations of the partners and local communities.They should be managed professionally to achievetheir maximum objectives.NECs?1. Natural environments are scarce, especially in urbanareas. Hence, NECs or eco-museums are crucial inbringing nature and urban inhabitants together.Noor Azlin Yahya2. NECs will cultivate a way of learning environmentalethics for living which will lead to sustainable humandevelopment in the long run.3. Nature education itself is a form of enhancing humancommunication and quality of life.4. NECs serve as a link between the local people andnature, activating community involvement andinspiring awareness and appreciation of naturethrough increased sense of ownership.5. Well-designed programs will enhance environmentalvalues and concepts in the school curriculum,encouraging engaged outdoor learning.Aims of a Nature Centre1. To promote environmental awareness andunderstanding of the relationship between peopleand their surroundings through experiences thatencourage personal discovery, group interaction,and respect for the natural environment.2. Make nature education accessible and affordable.3. Ensure the sustainability of education programmes.Setting up an NEC1. Agreement with the local governmentThis is to ensure the legal use of the NEC and its immediatevicinity. It will also ensure smooth implementation ofthe project. Such an official agreement will demonstratethe participation and commitment of necessarystakeholders.2. Financial PlanningBudget has to be carefully allocated. Initial start-upfunds have to be channelled to establish a physicalinfrastructure. The housing may be in the form ofa newly-constructed building or an existing andrenovated building. There would be costs incurredfor electrical systems, furniture purchase, computersystems, etc. Staff salaries, utility and transportationcosts have to be taken into consideration.<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 21

Setting Up Nature Education Centresand Interpretation ProgrammesNoor Azlin Yahya3. Advisory CommitteeThe NEC must be perceived as belonging to thecommunity. At the same time, it needs the communicationand support of related organizations, such as NGOs,heritage agencies, or recreational societies. Hence,an advisory committee has to be set up to discuss andrecommend the programmes to be conducted, as wellas to evaluate the progress of the NEC.Setting up an NEC Program1. Identify Target GroupsThe different sectors of target audience can beclassified as: schools (primary and secondary); teachers;colleges and institutions of higher learning; youth clubs;adult members or non-members; corporate groups;planners, administrators, or government officials;potential sponsors; scientists or specialists; “friends”of the centre who may be committed to assisting inactivities.2. Human Resource ManagementThe success of any NEC is highly dependent on theallocation and deployment of its human resources,both the staff and the local community volunteers.3. Structure of PlanningPlanning at each stage must be consciously made witheducation and awareness goals in mind. An NEC has toidentify the conservation message/theme; the facilitiesneeded; the facilities available; the level of interpretationneeded for each group of intended users; the skills eachgroup needs to learn; the attitudes to be encouraged;and an evaluation plan/programme.4. ConsiderationsA good NEC programme would recognize the complexinterrelationships of the ecosystem, the environment,and the people. It has to acknowledge that changesare achieved slowly, especially in relation to attitudes,and it is important to maintain consistent efforts. It hasto realize that success speaks for itself and thereforetrack records and success stories are effective ways tomotivate people. Finally, it is essential to “package”the message, for the product is as important as themessage itself.5. Code of ConductMost people live at the “small picture” level; henceeffective awareness is needed to link bigger issues tothe local or immediate context. As far as indigenousknowledge and systems are concerned, there isnothing to lose by balancing the knowledge of modernscientific systems with the wisdom of indigenoussystems.Incorporating Environmental InterpretationEnvironmental learning, or interpretation, occurs bestin informal settings. This is because such settings areeducational as well as entertaining. Such an approachwould have the important effect of opening up andaffecting people’s otherwise conservative attitudesand behaviour. The presenters defined environmentalinterpretation as a technique of communication, a twowayprocess based on listening to, and understanding,the perceptions of the individual or group. It attendsto the need to communicate technical information tonon-technical audiences. It translates the technicallanguage of a natural science into terms and ideas thatnon-scientists can readily understand. It does so byadopting a method that is entertaining, informative, andsustaining at the same time.It was also emphasized by the presenters that theinterest of the audience has to be captured throughan organized and easy-to-follow presentation thatpromises to be rewarding. The process for an NECprogramme should aim at educational, emotional and22 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 23

Setting Up Nature Education Centresand Interpretation ProgrammesNoor Azlin Yahyabehavioural changes in the audience. It ideally proceedsin the following sequence: interpretation - attraction -exposure - understanding - appreciation - environmentalprotection.The must-have elements of interpretation, accordingto learning expert Freeman Tilden, consists in relating,revealing, and provoking. They combine in a holisticway, often involving art, expression and analysis.Analogies, comparisons, personal anecdotes should beused to relate to what the audience knows and caresabout. The emphasis should be on relationships ratherthan facts and figures. The tone should be human,pleasurable, relevant, fun and meaningful, for peoplemay forget specific details but not their feelings of theevent they have experienced. The presentation wasconcluded with an assertion from the speakers thatthe theme is always central to the interpretation, and,as in every good story, there is a clear beginning andan end.24 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 25

Setting Up Nature Education Centresand Interpretation ProgrammesNoor Azlin Yahya26 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 27

Setting Up Nature Education Centresand Interpretation ProgrammesNoor Azlin Yahya28 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 29

Setting Up Nature Education Centresand Interpretation ProgrammesNoor Azlin Yahya30 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 31

Setting Up Nature Education Centresand Interpretation ProgrammesNoor Azlin Yahya32 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 33

Setting Up Nature Education Centresand Interpretation ProgrammesNoor Azlin Yahya34 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 35

Setting Up Nature Education Centresand Interpretation ProgrammesHa Long Bay –A World HeritageHoang Thi Ngoc Ha and Hguyen Thu HuyenHa Long Eco-Museum,World Nature Project,Ha Long Bay Management Dept,Hoang ThiNgoc HaHguyen Thu HuyenT he presenters for ‘Ha Long Bay – A World Heritage’(full presentation on page 41-58) articulated that HaLong Bay is a world natural heritage, twice recognized assuch by UNESCO. In 1994, it was awarded this statusfor its outstanding aesthetic value, and, again, in 2000for its geological and geomorphological value.Ha Long Bay is a concentration of thousands oflimestone islands. Covering a total area 1553 squarekilometres, it includes 900 named islands. The protectedarea is about 434 square kilometers that covers 775islands. It is bounded by three areas, namely, Ba HamLake, Dau Go Island, and Cong Tay Island. Theseencompass hundreds of sand beaches, beautiful caves,lakes, lagoons and grottos, limestone plains and towers.There is a diversity of marine creatures and eco-systemsof plants and natural life.As the ancient home of the Vietnamese people,there is archaeological evidence of cultural relics in HaLong Bay. Even today, there are fishing communities thathave been living there for many generations, creating atruly unique Ha Long culture. Bearing such extraordinarybiodiversity, this special region is under research andwill be submitted to the UNESCO for the third time forofficial recognition.Ha Long Bay Eco-MuseumIt was asserted by the presenters that Ha Long BayEco-Museum adopts a holistic outlook and has a36 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums

Ha Long Bay – A World HeritageHoang Thi Ngoc Ha andHguyen Thu Huyen“people-centred” strategy with the purpose of bringingpeople and the environment together. The projectrepresents a new approach aimed at raising communityawareness and responsibility for the living heritage ofHa Long Bay and its environs through the developmentof an effective interpretative tool system. It also aimsto develop sustainable tourism, create more jobs andcontribute to poverty alleviation.In 2000, a feasibility study plan was devised whichdrew much attention from relevant Vietnamese institutionsand local communities. From July 2000 to February2001, with a donation from the UNDP, as well astechnical assistance from the Ministry of Culture andInformation and UNESCO’s National Commission,the feasibility plan was carried out. According to thespeakers, despite difficulties and challenges, itproduced important results that have contributed tothe success of the entire Ha Long Bay Eco-Museumproject.The Ha Long Bay Eco-Museum is essentiallyconceived in two parts. Part 1 consists of the Hubwhich promotes facilities for environmental studies andknowledge of the natural heritage. The facilities includethe interpretation centre, the exhibition room, the studyroom, the data centre and the GIS centre. At the Hub,one finds a playground for children, a botanic garden,an aquarium, and an activity area where there are artand handicrafts workshops.Part 2 of the Ha Long Bay Eco-Museum comprisesOutdoor Themes. Classified as the natural and culturalheritage of the Quang Ninh Province, the museumis officially a national museum with 12 outdoorthemes. These include the Ngoc Ving Retreat, BaiTho Mountain, Bach Dang – a Symbol of Freedom,Me Cung archaeological site, Traditional Boat-building,Coal Mining, Ecology Hotel, Soi Sim Island, Youth inQuang Ninh, Women in Quang Ninh, Children in QuangNinh, Cua Van Floating Cultural Centre.Of these 12 theme projects, the Cua Van FloatingCultural centre was the first to be implemented witha donation from NORAD under the auspices of theNorwegian Embassy. The following was expounded bythe speakers to spotlight on this successful project.Cua Van Floating Cultural CentreThe Centre itself is located in the charming Cua Vanfishing village which is one of the biggest among fourfishing villages on Ha Long Bay. Targeted at the fishermenof the community, the Centre organizes both shorttermand long-term training courses on managementand technical skills for the preservation of tangiblecollections and the living heritage. It was set up topromote awareness-raising activities and to educatethe communities to protect the Ha Long Bay and itsvalues. Through performances, lectures and exhibitions,the Centre transmits the importance of traditionaland contemporary cultural assets of Cua Van.The Centre has carried out its programmes withclear understanding of the ecology and needs of theCua Van environment and living culture. The historicCua Van village has 127 families and 600 people. Thecommunity economy primarily depends on fishing,as well as selling food, fresh water and fuel to touristboats. Before 1998, most of the villagers wereilliterate, but since 1998, floating classrooms have beenestablished for children from grade one to five, with anextra class for learning adults. Each family lives on aboat that is not only a shelter but also a fishing tooland transportation vehicle. The community subscribesto traditional spiritual beliefs such as worshipping theirancestors, village founders, and sea gods. Wheneverthere is a wedding or a traditional festival, the entirevillage would come together to celebrate. The presentersremarked that these are cultural values that the Centreseeks to enhance and preserve.38 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 39

Ha Long Bay – A World HeritageHoang Thi Ngoc Ha andHguyen Thu HuyenSome of the activities that are carried out have thusmobilized community participation and consciousness.These include campaigns to raise the heritage prideof the Cua Van villagers, instilling in them a sense ofhome, ownership and protection of their environment.Activities are organized on World Environment Dayand there has been education on garbage deposit andcollection. There are training courses on being local tourguides and also trips to visit caves to assess the impactof tourism activities on the natural landscape.As for visiting tourists, there are specially designedprogrammes to encourage the appreciation of thecultural values of Cua Van village. Students take part inactivities such as ethnographic discussions, interviewinga fishing family, giving gifts to pupils in the village,rubbish-collecting, studying the plants on Soi SimIsland, exploring the Luon Cave, <strong>Mangrove</strong>-planting,and learning about fresh water utilization. Thepresenter considered all these activities by the CuaVan Floating Centre to have contributed purposefullyto the sustainable conservation of Ha Long Bay on thewhole.40 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 41

Ha Long Bay – A World HeritageHoang Thi Ngoc Ha andHguyen Thu Huyen42 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 43

Ha Long Bay – A World HeritageHoang Thi Ngoc Ha andHguyen Thu Huyen44 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 45

Ha Long Bay – A World HeritageHoang Thi Ngoc Ha andHguyen Thu Huyen46 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 47

Ha Long Bay – A World HeritageHoang Thi Ngoc Ha andHguyen Thu Huyen48 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 49

Ha Long Bay – A World HeritageHoang Thi Ngoc Ha andHguyen Thu Huyen50 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 51

Ha Long Bay – A World HeritageHoang Thi Ngoc Ha andHguyen Thu Huyen52 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 53

Ha Long Bay – A World HeritageHoang Thi Ngoc Ha andHguyen Thu Huyen54 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 55

Ha Long Bay – A World HeritageHoang Thi Ngoc Ha andHguyen Thu Huyen56 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 57

Ha Long Bay – A World HeritageThe SiteDevelopment ofthe <strong>Mangrove</strong>Forest, Tabon CaveComplexWilfredo Vendivil and Ernesto BToribio JrNational MuseumThe PhilippinesD r. Wilfredo Vendivil and Mr. Ernesto B Toribio Jrpresented ‘The Site Development of the <strong>Mangrove</strong> Forest,Tabon Cave Complex’ (Quezon, Palawan), the Philippines(full presentation on page 63-73).WilfredoFernandez VendivilErnestoB Toribio JrTabon Cave ComplexThe Tabon Cave Complex is located at Lipuun Point atQuezon in Palawan. Its geological development datesback to some 9,000 to 10,000 years ago when it wasconnected to the mainland of Palawan. It was estimatedthat the shoreline was about 35 kilometres from theTabon Cave. At the end of the Ice Ages, the sea levelrose to its present level and the Tabon Cave Complexbecame an island. Over time, erosion and siltationtook place and this led to the growth of the mangroveforest which links the Tabon Cave Complex to themainland of Palawan.The paper noted that today, the site covers 138hectares of limestone formation and rugged cliffs, with218 caves and rock shelters, boasting diverse habitatswith indigenous flora and fauna. Archaeological finds dateback to 50,000 to 700 years ago, and it has beendiscovered that 38 caves were used as habitation and58 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums

The Site Development of the <strong>Mangrove</strong>Forest, Tabon Cave ComplexWilfredo Vendivil andErnesto B Toribio Jrburial sites in the ancient times. The famous archaeologistDr. Robert Fox and the National Museum team haveunearthed sites that reveal 50,000 years of Philippineprehistory, with invaluable findings such as the Tabonman skull cap and the Manunggul burial jar.The origin of ‘Tabon’ can be traced back to the localscrub fowl of the same name. The amazing biodiversity ofthe Tabon Cave Complex can be observed in its myriadnatural habitats such as the karst forest, beach forest,coconut plantation, marine environment, and mangroveforest. The karst forest is a limestone landscape thatdominates the complex, while the marine ecologyencompasses beautiful coral formation, the habitat ofa diverse species of fish and sea grass beds that areessential for many fish and turtles. There is also a widevariety of local species of crabs, indigenous birds likethe Palawan hornbill and rare bats that reside in thecaves, making the complex a vast home to natural lifeforms.Preserving Tabon Cave ComplexThe presenter reported that given the richness of theTabon Cave Complex, it was declared a Site MuseumReservation pursuant to the Presidential ProclamationNo. 996. As mandated by law, the National Museum isthe administrator tasked to protect and preserve thisreservation for the present and future generations.Site development projects have been proposed as jointefforts of various government agencies, such as theNational Museum; the Department of Tourism Authority;the local government of Quezon, Palawan; and theNational Commission on the Arts.The development plans have started since 1970,with the establishment of the National Museum Branchto better administer the site museum as well as to protectand preserve the resources. Coordination has been madewith the local government to impose local laws for theconservation of natural and cultural assets. Since then,ongoing efforts have been made to improve the qualityof the exhibits and carry out other works, including:• landscaping of the ground of the branch museum• construction of the boardwalk leading to the caves• installation of signage on the geology, flora, fauna,and archaeological resources• rehabilitation of the eco-tourism trails• tour guides’ training for the local community• publication of guidebooks• production of audio-visual materials• establishment of co-operatives of handicraftentrepreneurs and boat owners• development of the mangrove forest.Development of the <strong>Mangrove</strong> ForestThe main objective of developing the mangrove forest, asthe speakers described it, is to create a living laboratoryto study its importance to the community and tohumanity. The other specific objectives of this projectare as follows:1. To conduct an extensive study of the formation ofthe mangrove forest at the complex2. To carry out an inventory of flora and fauna3. To observe the ecological status of the mangroveforest4. To document through photography the dominantplants and animals5. To construct a boardwalk and observatory platformswithin the mangrove forest6. To install signage in key areas of the boardwalk7. To prepare a guidebook on the protection of themangrove forest8. To involve the community in the protection andpreservation of the mangrove forestThe development of the mangrove forest into aneco-museum is a significant project. As the mangroveforest connects the Tabon Cave Complex to themainland of Palawan, it serves as a sanctuary for marine60 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 61

The Site Development of the <strong>Mangrove</strong>Forest, Tabon Cave ComplexWilfredo Vendivil andErnesto B Toribio Jrlife and birds, protecting the complex from strongwaves, becoming a buffer zone as such that shelters thecultural resources of the complex.The mangrove eco-museum features a naturalwinding trail along the beach forest, with a 175-metreboardwalk equipped with observatory platforms, thusserving as a living laboratory to observe the mangroveecosystem. The signage has been installed to createawareness of the need for communal protection andpreservation of the mangrove forest. The signageprovides invaluable information on the geologicalevolution of the area; the location of the mangroveeco-museum in the complex; and the typology of plantsand animals in habitation. In particular, it highlights theimportance of mangrove eco-system.The paper emphasized that at the end of experiencingthe eco-museum, the visitor must carry away withhim/her the message that the mangrove forest isendangered. The illegal cutting of trees and theconversion of swamps into fish and prawn ponds andfor urban expansion have become widespread. Ifthese unhealthy practices persist, ecological stabilitythat has been in existence of thousands of years willbe destroyed and the environment faces extinction.The importance of the mangrove forest must bereiterated. It protects the coastal areas by reducingthe damages caused by typhoons and strong winds. Italso acts as a buffer zone protecting the sea grass bedsand coral reefs. It provides sanctuary to fish and othermarine organisms. It is a source of timber, firewood,dye, tannin, charcoal, thatch, alcohol, and medicine. Itis an essential recreational area for bird-watching andobservation of wildlife.Finally, as a living museum, the mangrove forest is anideal place to study the interaction of plants andanimals with the environment. The presenters believedthat every visit is an opportunity to understand thatthe forest helps to sustain the coastal and marineenvironment for the survival of many organisms, includingman. It stresses the awareness of communal protectionand the preservation of our natural heritage.62 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 63

The Site Development of the <strong>Mangrove</strong>Forest, Tabon Cave ComplexWilfredo Vendivil andErnesto B Toribio Jr64 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 65

The Site Development of the <strong>Mangrove</strong>Forest, Tabon Cave ComplexWilfredo Vendivil andErnesto B Toribio Jr66 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 67

The Site Development of the <strong>Mangrove</strong>Forest, Tabon Cave ComplexWilfredo Vendivil andErnesto B Toribio Jr68 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 69

The Site Development of the <strong>Mangrove</strong>Forest, Tabon Cave ComplexWilfredo Vendivil andErnesto B Toribio Jr70 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 71

The Site Development of the <strong>Mangrove</strong>Forest, Tabon Cave ComplexWilfredo Vendivil andErnesto B Toribio Jr72 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 73

Janet Tee Siew MooiEducationProgramming inMuzium NegaraJanet Tee Siew Mooi,Deputy Director,Muzium Negara Kuala LumpurI n another presentation from Malaysia, Ms Janet Tee SiewMooi, Deputy Director, Muzium Negara Kuala Lumpur,touched on the role of eco-museum in education inher paper, ‘Education Programming in Muzium Negara’(full presentation on page 77-84).The presenter noted that the International Councilof Museums (ICOM) defines a museum as a non-profitpermanent institution in the service of society and ofits development. The museum is open to the public, andits work consists in acquiring, conserving, researching,communicating, exhibiting for the educational andother related purposes, including those of givingenjoyment to the public and showing it the materialevidence of people and their environment.The motivation for setting museums comes from theneed to establish educational institutions that cancombine learning and enjoyment as well as expandedopportunities for leisure and tourism. As the speakernoted, people visit museums for various purposes – forrecreation, that is, to enjoy free, relaxed and unstructuredtime and activity; and for sociability, meeting with orparticipating with others, in shared public activities.Their social class and educational backgrounds may ofcourse be relevant to their decision to visit a museum,but in saying this we do not mean that museums belongto any particular class or group in society. It is opento all.Janet TeeSiew MooiThe priorities of a museum once included collectingand preserving. Now, however, museums also serve toeducate and entertain people. This changing role hasto be implemented with necessary adjustments to meetthe needs and requirements of the communities in whichthey are located. Greater services have to be introducedto meet the growing expectations of the visitors.Education Programming has to determine the TargetAudience. Though now museum educational activitiesoften relate to children, adults also seek opportunitiesto learn with the families. Museums, indeed, can “strengthenbasic skills, basic knowledge, basic comprehension, andbasic understanding”.Students are encouraged to say something abouttheir interests and how they might respond to a particularsituation or circumstance that has been carefullyselected. This association with the students’ immediateworld will help them become less self-conscious andthink in a predetermined direction.The “Educational Programming Schedule” can beorganized as a three-part initiative, as follows:• Planning: This includes the tactics and sequenceof activities organized to achieve the establishedgoals. This process identifies who will do what,when and how.• Presenting: This involves scheduling, which isan important factor in the educational process.Staff and volunteers must be available to presentthe programmes, and consideration must begiven to the times and locations that will bestaccommodate the target group.• Evaluating: Programme evaluation will provide theplanners with an idea of whether the programmeas presented corresponds with the planningobjectives. This will also serve as a guide for<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 75

Education Programming inMuzium NegaraJanet Tee Siew Mooifuture development of the programmes of thesame type.Such education programmes include self-guidedtours (with or without a volunteer) and guided tours(with a guide or pre-arranged script), hand-on activities(in the Discovery room) and direct involvement withmaking, touching or feeling. They can also involveorganizing activities of interest to different age groups,fringe activities, temporary exhibitions (artefacts,performances, demonstrations, and dioramas).There have been “Smart Partnership with the Media”(quiz and drawing competitions), “Sleep-over: A Night@ The Museum”, and “Behind the Scenes Tours”.Moreover, further museum interest can be generatedthrough Free Admission Day (on International MuseumDay, during Heritage Week, etc.) and Friends andVolunteers initiatives.To close the presentation, the speaker highlightedthe collaboration with other related agencies, whichinvolve the Ministries of Culture, Arts and Heritage,Education, Tourism and Youth and Sports, and schools,NGO’s Senior Citizens Clubs, and embassies.76 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 77

Education Programming inMuzium NegaraJanet Tee Siew Mooi78 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 79

Education Programming inMuzium NegaraJanet Tee Siew Mooi80 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 81

Education Programming inMuzium NegaraJanet Tee Siew Mooi82 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 83

Education Programming inMuzium NegaraCoastal Communityin the Kingdom ofCambodia(A Case Study on <strong>Mangrove</strong> Management)Ouk Vibol,Deputy Director ofConservation Division, FisheriesAdministration, Ministry ofAgriculture, Forestry and FisheriesCambodiaM r Ouk Vibol, Deputy Director of Conservation Division,Ministry of Agriculture, Cambodia presented ‘CoastalCommunity in the Kingdom of Cambodia (A Case Studyon <strong>Mangrove</strong> Management)’ (full presentation on page89-97).Ouk VibolGeneral IntroductionCambodia covers an area of 181,035 square kilometres.It is classified as country-rich in natural resources andconsidered a “water-wealthy” country. Its total fishproduction ranges from 279,000 to 441,000 tonsfrom inland water and 35,000 to 45,000 tons frommarine water. Before 1960, the forest area coveredmore than 70 per cent of its land surface, and it isestimated that in 1997, 10.6 million remained in thecountry.Cambodia’s total population (2005 estimate) is13.7 million. Over 84 per cent of the people live inrural areas, and 85 per cent of them depend directlyon natural resources. The country’s coastline extendsover 435 kilometres from the Thai border in the northto the Vietnamese border to the south.84 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums

Coastal Community in the Kingdomof Cambodia (A Case Study on <strong>Mangrove</strong> Management)Ouk VibolCoastal Resources and Legal FrameworkThe total stock of marine fin fish during the 1980’s wasestimated at 50,000 metric tons. 435 species of the fishstock remain in existence. <strong>Mangrove</strong> forest, coral reef,and sea grass habitats are some of the most biologicallyrich and economically valuable ecosystems. The paperexplained that the “Law of the Fishery” states that allthese mangrove, coral reef and sea grass habitats areclassified as protected conservation areas.Threats to <strong>Mangrove</strong> Forestand ResolutionThe presenter indicated that the most urgent threatsto the mangrove forests in Cambodia are numerous.These include:• Charcoal production• Land encroachments• Illegal logging• Urbanization• Coastal development• Salt farming• Intensive shrimp farmingConcept of Community-based NaturalResource Management (CBNRM)There is action to manage the mangrove forestthrough increased public awareness and communitybasedinitiatives such as the Community-based NaturalResource Management (CBRM).There are day-to-day watches conducted by fisheryofficials, community members and local authorities.<strong>Mangrove</strong> areas have been demarcated, and illegalencroachments on these areas have been confiscated.About 1,023 hectares have already been confiscated.At the same time, to replenish the mangrove, replantingof the mangrove has been recommended.Mr. Vibol described that in the Cambodian context,CBRM is defined as “a diversity of co-managementapproach that strives to empower local communities toactively participate in the conservation and sustainablemanagement of natural resources”. This measure isneeded in Cambodia because the resource stocks andenvironmental quality have become degraded, whilebiodiversity and the ecosystem are resources thaturgently need protection.The goal of CBRM can be divided into twocategories: community empowerment goals andecosystem conservation goals. Each category of theCRBM goals covers the following issues and themes:Community empowerment goals include:• Poverty reduction• Social justice/equity• Improvement of livelihoods• Viable economic income• Respect for local/traditional ecological knowledge• Community organization and local network.Ecosystem conservation goals include:• Ecosystem services conserved• Hydrological cycle• Water quality• Soil, forests, wildlife• Habitats• Sustainability.Guidelines for Coastal CommunityEstablishmentThe coastal community in Cambodia can be establishedin mangrove, coral reef, and sea grass areas, where waterdepth is less than 20 metres. Mr. Vibol explained that40 coastal community fisheries have been establishedso far. By-law and regulations on the establishment ofcoastal communities cover the following details:• Name of the community and its objectives• Community membership86 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 87

Coastal Community in the Kingdomof Cambodia (A Case Study on <strong>Mangrove</strong> Management)Ouk Vibol• Management of the community’s incomes andexpenses• Community committee arrangement• Community committee election• Community meeting arrangement• Termination of the community• By-law revision procedure.Opportunities and ChallengesThe development of coastal communities is a highlychallenging project. However, a successful resourcemanagement-oriented coastal community requires manyconditions. These include:• A sustainable policy and legal framework• Good governance and decentralization• Conflict resolution mechanisms• Attention to gender and equity issues• Information-flow management (cooperation,networking, and knowledge sharing)• Enforcement• Monitoring and reflective learning analysis• Sustainable livelihood.• To enhance the natural environment.As expressed during the presentation, the case studyhas confirmed that there are both challenges and benefitsof coastal community organization. The challengesrelating to this resource management initiativeinclude its political aspect, the problem of transparency,the lack of communication and involvement of therelevant institutions, poor knowledge and poverty,and the lack of funding. However, the project has alsoproved that the benefits to be gained should outweighthe problems it has encountered:• Most local people understand the significance ofthe mangrove forest.• The coastal environment has improved.• The general incomes of the people in the communityhave been improved.• Illegal fishing activities have been reduced.• <strong>Mangrove</strong> logging and encroachment havestopped.• 70 hectares of mangrove forest have beenreplanted.Participatory Management of <strong>Mangrove</strong>Resources in Peam Krasaop Wildlife Sanctuary:A Case StudyComprising three districts, six communes, and 12villages, the Peam Krasaop area has a population of about10,000 people. It was declared by a royal decree asWildlife Sanctuary on 1 November 1993. Its mangroveswamp, which covers an area of 10,000 hectares, has34 species of birds and a rich biodiversity of fish, crabs,snails, turtles, dugongs, and dolphins. The aims oforganizing this coastal community are as follows:• To solve conflicts in the area• To find a way of raising the incomes of thepeople• To strengthen local awareness of importance ofcoastal resource management88 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 89

Coastal Community in the Kingdomof Cambodia (A Case Study on <strong>Mangrove</strong> Management)Ouk Vibol90 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 91

Coastal Community in the Kingdomof Cambodia (A Case Study on <strong>Mangrove</strong> Management)Ouk Vibol92 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 93

Coastal Community in the Kingdomof Cambodia (A Case Study on <strong>Mangrove</strong> Management)Ouk Vibol94 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 95

Coastal Community in the Kingdomof Cambodia (A Case Study on <strong>Mangrove</strong> Management)Ouk Vibol96 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 97

Koh Lee Chew,Lim Han She and Shawn LumWater Culture andthe Community –RaisingEnvironmentalAwarenessKoh Lee Chew (Ngee Ann Polytechnic),Lim Han She (National University of Singapore), andShawn Lum (National Institute of Education)I n the presentation, ‘Water Culture and the Community– Raising Environmental Awareness’, Singapore’sdelegates discussed the efforts to increase awarenessof environmental issues in Singapore (full presentationon page 103-118).To start the presentation, the speakers cited thatas a city-state, Singapore is an island nation of almost700 km 2 sandwiched between Johor, Malaysia, andRiau, Indonesia. Serving as an important transport,shipping, trading, and manufacturing hub, the city-stateis economically vibrant. It is also known for its cleanlinessand celebrated for its efficiency.As an island nation, Singapore has importantconnections with water. Historical and present-day waterconnections include:• Raffles landing spot• Port and associated industries• Fishing and coastal communities• Love for seafood (and famous for suchrestaurants)• Rivers/estuaries with transport and entertainmentutilities• Domestic and industrial use of water• Land reclamation as a result of landfill for waste.Top: Koh Lee Chew;Middle: Lim HanShe;Bottom: Shawn LumDespite such close and multivariate connectionswith water, the speakers remarked that Singapore doesnot have a self-sufficient supply of water. It has variouswater bodies, including canals (7,000 km), reservoirs(14), rivers (32), and the coastline. Its main reservoirsinclude the MacRitchie – the first central reservoir – andthe Upper Seletar reservoir. Additional reservoirs alsoexist, which have been formed by damming estuaries.Still other connections with water can be found.The Labrador Nature Reserve is a coastal nature area,and at the Sg Buloh Wetlands Reserve, mangroves stillexist. Moreover, Bishan Park combines natural scenerywith lakes, while in the busy centre of the island state,Gardens by the Bay and Marina Bay Reservoir canbe found. At Sentosa, Singapore’s island resort,Underwater World offers a marine environment in a funand educational way.What are Singapore’s efforts at raising an awarenessof water?“National Policy and Implementation” includesthe “Four Taps of Singapore”. These are wastewaterreclamation, desalination of seawater, import fromMalaysia, and reservoirs. Many other projects andactivities have also been put into effect, including nolittering, a Save Water Campaign, Grassroots (an ABCWaters programme), educational programmes, andpassion to preserve the environment.ABC Waters stands for Active, Beautiful, CleanWaters. Tan Nguan Sen, the director in charge of thisproject, has explained its purpose as follows: “In the lasttwo years, we have been trying to bring people nearerto water through the introduction of water activities atreservoirs, such as kayaking, rowing, fishing and so on.Under the ABC Waters programme we will bring thewater to the people by exploring the potential of ourwater bodies throughout the island”. This ABC schemealso involves:<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 99

Water Culture and the Community –Raising Environmental AwarenessKoh Lee Chew,Lim Han She and Shawn Lum• Landscaping of river banks• Lookout areas that extend into the river• Creation of streams and pools by drawing waterfrom canals• Water stage for outdoor performance.There are ABC plans for a number of differentareas including Sungei Tampines, Sungei Punggol, andPang Sua Canal.As mentioned in the presentation, new reservoirsare expected to be constructed by 2009. At SungeiSerangoon, there will be a floating wetland, links tothe mainland by a suspension bridge and a floatingboardwalk; while at Sungei Punggol, a wetland will beconstructed at the edge of the reservoir covering anarea of 11 hectares.A useful comparison of the vegetation of Singaporein 1819 was made with that of the 1990’s. The comparisonwas based upon the case study of Sungei BulohWetland Reserve. Covering an area of 87 hectares,the site, which was gazetted in 1989, is of importancefor migratory birds.To enhance the passion to preserve the environment,numerous school activities have been initiated. Theseinclude:• Coastal cleanup• Paintings at shelters along the boardwalk• Students trained to work at stations to giveinformation or as guides• Adoption by schools of a particular environment• Preparation by schools of educational materials• Reforestation.One direct scheme implemented at secondary schoolsis the “Reforestation and Reach Out Project”. Underthisproject, schools in Singapore are directly involved inthe conservation of nature. The purpose is for them todo their part in this vital environmental task, which alsoincludes a revamp of outdoor classroom and surroundingareas through reforestation and development ofeducational materials and websites. Funding could beacquired from HSBC, Toyota, Shell, and National Parks.At Ngee Ann Polytechnic, for example, students,in pursuing their educational programmes, are providedwith an opportunity to appreciate the scarce naturalhabitat in Singapore, which is an urban society. Oneexample was the study of a “Rocky Seashore Biodiversity”at Labrador Park located southwest of Singapore. Part ofthe students’ work here consisted in compiling “Examplesof Classification and Taxonomy of Seashore Creatures”.The paper commented that there are promisingsigns that a concern for aquatic environments isgrowing in Singapore. Is this a possible outcome of awater culture? Young, dynamic environment-consciousgroups, such as the Blue Water Volunteers, have beenactive in enhancing concern for water and marineconservation and awareness. An outpouring of publicconcern for Pulau Ubin, Tanjong Chek Jawa, led topostponement of reclamation. Instead, visitor facilitiesare now under construction.As part of water culture and environment, schoolchildren learn about the environment and its conservation.They are taught the importance of water (and the need toconserve it). For example, students learn about pollution,the need to recycle, and the importance of conservingwater. A learning programme of this type can be seenfrom Singapore primary science syllabus:“At the social level, the interaction of Man withthe environment drives the development of Scienceand Technology. At the same time, Science andTechnology influences the way Man interacts with hisenvironment. By studying the interaction betweenMan and his environment, pupils can better appreciatethe consequences of their actions”.The primary six science syllabus asks students toidentify factors that affect the survival of an organism,100 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 101

Water Culture and the Community –Raising Environmental AwarenessKoh Lee Chew,Lim Han She and Shawn Lumincluding the physical characteristics of the environment,availability of food, types of other organisms present. Inthis way, it is hoped that pupils should appreciate andhave a respect for living things and the environment.Also, examples have to be given of man’s impact (bothpositive and negative) on the environment.In determining to what extent does Singapore have a“water culture”, can an analogue be found in Singaporeanattitudes to Nature Reserves and recreation?Bikit Timah Nature Reserve is the largest remnantpatch of primary forest remaining in Singapore. TheKayu Gelam (melaleuca cajuputi), a native of swamps,lends its name to a historic part of the town – KampongGelam. Telok Kurau, an area in great demand for housingcomes from “Ikan Kurau”, or “Threadfin” which promptsthe questions: How many students knew the origin ofthe place name?Tanjong Katong has seen a dramatic change inlandscape over the past century. This has resulted in adisconnection with our past – and hence a disconnectionwith water? How strong is the linkage between lifestyle,sustainable development, and nature and waterconservation – indeed, how great is the gap betweenawareness and action?In conclusion, the presenters stressed that “WaterCulture” was expressed with these views:• Better to have one than not to have one• Having a water culture is no guarantee of wisestewardship of water resources and habitats• It should lead to a desire to learn more aboutwater• In today’s world, this should lead to more holisticthinking about water (e.g., our impacts on waterelsewhere)• It should lead to positive outcomes• It should constitute more than knowledge – theremust be an emotional/spiritual/cultural link aswell102 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums• It should connect people to a place and one’s past(and future?)• It should connect generations to each other.<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 103

Water Culture and the Community –Raising Environmental AwarenessKoh Lee Chew,Lim Han She and Shawn Lum104 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 105

Water Culture and the Community –Raising Environmental AwarenessKoh Lee Chew,Lim Han She and Shawn Lum106 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 107

Water Culture and the Community –Raising Environmental AwarenessKoh Lee Chew,Lim Han She and Shawn Lum108 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 109

Water Culture and the Community –Raising Environmental AwarenessKoh Lee Chew,Lim Han She and Shawn Lum110 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 111

Water Culture and the Community –Raising Environmental AwarenessKoh Lee Chew,Lim Han She and Shawn Lum112 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 113

Water Culture and the Community –Raising Environmental AwarenessKoh Lee Chew,Lim Han She and Shawn Lum114 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 115

Water Culture and the Community –Raising Environmental AwarenessKoh Lee Chew,Lim Han She and Shawn Lum116 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 117

Water Culture and the Community –Raising Environmental AwarenessNature Centresfor WetlandConservation inMalaysiaNoor Azlin Yahya, Chong Mew Im and Azyyati Abd.Kadir, Ecotourism and Urban Forestry Programme,Forestry Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM)Noor Azlin YahyaI n the presentation, ‘Nature Centres for WetlandConservation in Malaysia’, (full presentation on page121-131) Noor Azlin Yahya, Chong Mew Im and AzyyatiAbd. Kadir began by stressing that Malaysia is home tovarious types of wetlands. These include the coastalwetland – mangroves and nypa; inland wetland; naturalwetlands, for example, marshes, lakes, rivers, floodplains and peat swamps; and man-made or artificialwetlands, e.g., rice fields, dams, and reservoirs. Wetlandconservation has been undertaken by the governmentagencies, NGO’s, as well as private organizations.Wetland conservation projects include:• Government projects: for instance, FRIM-UNDPproject and Forestry Department projects (LoaganBunut, Kilas Nenasi)• NGO projects: e.g., Malaysian Nature Societyand WWF Malaysia (Terengganu and KualaSelandgor)• Private organizations’ projects, such as PerwiraBintang (Sg Besar).Malaysia’s mangroves have received the conservationefforts of government forest departments, the privatesector (Perwira Bintang), as well as NGOs MNS & WWF.Other sites include Kota Kinabalu City (Bird Sanctuary)and Kuala Selangor Nature Park.118 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums

Nature Centres for WetlandConservation in MalaysiaNoor Azlin Yahya,Chong Mew lm and Azyyati Abd. KadirIt was explained by the presenters that environmentalinterpretation serves as a very important management toolto convey the message for sustainable forest management,for example, in the form Recreation Forests. Moreover,wetland tourism, consisting of village communities;tourism with an emphasis on education; fireflies, birds,and other wildlife watching; and floating restaurants, hasalso received growing attention.The Forest Research Institute in Malaysia (FRIM)receives various types of visitors. Members of the generalpublic constitute 70 per cent of its visitors, while 24 percent are students and 6 per cent are foreign tourists.All through its history, trees have been annually planted,and it has surveyed the number planted between 1927and 1960.Today, FRIM operates within forested grounds,explained the presenters. It has established enoughto support the different types of habitat required by adiversity of wildlife, including the wetland dependentamphibians, such as tree frogs that need specific nichesas their dwellings near the tree canopies.In the “River Corridor” (Sg Kroh in FRIM), variousspecies of flora can be found, including the Jelutong(Dyera constulata), Sentang (Azadirachta excelsa), andTeak (Tectona grandis).Wetland Interpretation activities also involveclass outings from schools. Birds spotted during theseInterpretation activities include kingfishers, GoldwhiskeredBarbets, Crested Serpent Eagles, GreaterRacket-tailed drongo, and yellow Bitterns. Moreover,there are Monitor Lizards (Varabus sp), insects andwetland plants in adaptation.Another type of activity is the Nature InterpretationCamp, for which the theme “Treasures of Wetland”has been adopted. The activity is undertaken with anInterpretation Kit that is used to conduct an environmentaleducation programme relating to freshwater wetland.The presenters underscored that still many othertypes of activities are already in existence, such as Naturegames, Traditional games, and arts and crafts includingorigami.120 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 121

Nature Centres for WetlandConservation in MalaysiaNoor Azlin Yahya,Chong Mew lm and Azyyati Abd. Kadir122 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 123

Nature Centres for WetlandConservation in MalaysiaNoor Azlin Yahya,Chong Mew lm and Azyyati Abd. Kadir124 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 125

Nature Centres for WetlandConservation in MalaysiaNoor Azlin Yahya,Chong Mew lm and Azyyati Abd. Kadir126 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 127

Nature Centres for WetlandConservation in MalaysiaNoor Azlin Yahya,Chong Mew lm and Azyyati Abd. Kadir128 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 129

Nature Centres for WetlandConservation in MalaysiaNoor Azlin Yahya,Chong Mew lm and Azyyati Abd. Kadir130 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 131

RecommendationsParticipants’Post-WorkshopRecommendationsfor Museum ofBangpakong BorvornWitthayayon School(Improvement plan)<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 133

RecommendationsRecommendations134 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 135

RecommendationsRecommendations136 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 137

RecommendationsRecommendations138 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 139

RecommendationsRecommendations140 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 141

RecommendationsRecommendations142 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 143

RecommendationsRecommendations144 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 145

RecommendationsRecommendations146 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 147

RecommendationsRecommendations148 <strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums<strong>Making</strong> <strong>Mangrove</strong> Eco-Museums 149