NON COMPLIANT CONTINUOUS CRUISING - Canal & River Trust

NON COMPLIANT CONTINUOUS CRUISING - Canal & River Trust

NON COMPLIANT CONTINUOUS CRUISING - Canal & River Trust

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

COUNCIL MEETING– 27 SEPTEMBER2012BriefingPaper– <strong>NON</strong><strong>COMPLIANT</strong> <strong>CONTINUOUS</strong> <strong>CRUISING</strong>CONTENTSExecutive Summary1. Background2. Licensing & moorings policy regulations – overview3. Generic solutions4. Current local projects5. ResourcingAPPENDIX A - A SHORT CHRONOLOGY OF PAST CONSULTATION 2002 - 2012APPENDIX B – LEGAL BACKGROUUND – MORECONTEXTTAPPENDIX C – THE ENFORCEMENT PROCESSAPPENDIX D – HOTSPOT MAP OF PRIORITY NCCCsEXECUTIVE SUMMARYThis paper provides a briefing on ourcurrent policies for achieving fair sharing of increasingly scarce mooringspace along the towpaths in ‘hotspot’ locations around the waterways. The British Waterways Act1995enables those using their boat ‘bona fide’ for navigation and not staying ina ‘place’ for more than 14 days toavoid the obligation to secure a homemooring – somewhere where the boat may lawfully be kept when notbeing used for cruising. Since the passing of thelegislation, the number of boat owners taking advantage ofthis provisiongrew steadily and has accelerated markedly since 2007. One consequence is the emergence ofinformal residential boating communities along certain stretches of our towpaths in urban areas ofthe southand east, largely in response to the housing shortage.We have putin place guidance for boaters without home moorings which make clear our interpretation of thelegislation, but achievingsatisfactorycompliancewith it is a goal that has persistently eluded us. The legalprocess is sound but extremely slow and costly. The problemhas grown up over 15 years so thatt we nowhave substantial clusterss of long termresidents along some towpaths comprising people whose fundamentallife style would be threatened by anychange in our policies totighten up implementation of the statute. Thematter is nowthe cause of tension between the growing bandof ‘non-compliant continuous cruisers’ andleisure boaters who report being deprived of the opportunity to tie up at popular short term moorings duringtheir cruises.The <strong>Trust</strong> now needs to be clear on our way forward. As well as setting out essential context, thispaperoutlines a number of generic options for dealing with problems locally. They focus onstrategic managementoptions rather than continued reliance on legal powers, although the latter will continue to provide the lastresort credible sanction against non-compliance.They will equire increased effort aswe start to design andPage 1 of 13

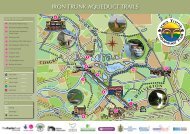

implement local mooringplans tailored to different areas and locations, and there maybe short term costimplications.Some of the proposed measures would however be expected to generate new income. Briefsummaries of how we are trying to apply solutions on the Kennet & Avon <strong>Canal</strong> and inLondon areset out andthe paper ends with a short discussion of resource implications.1. BACKGROUNDIncome from boat licences, moorings and associated activities accounts for over 15% of our annualturnover. It has beensubject to strong growthover the past decade arising from both volume and aboveinflation price increases. The number of boats using our network on a long term basis grew at an averageerate of c.825 each year in the decade from 2002 and nowstands at nearly 35,000.Growth in residential use of boats has been particularly strong. For many it’s a niche lifestyle choice andfor others, the need to secure affordable accommodationin areas close to employment opportunities isthe driving factor. Asa navigation authority, we are not concerned with how people use their boats, onlythat theycomply withlicensing rules. Our jobis to ensuree that the navigation andassociated facilities areavailableto all licence holders.In much the same way as parking control is an essential feature of smooth operation of highways,maintaining the amenity of the waterways requires some element of mooring control along thetowpaths.Legislation in 1995 gave us powers to requiree that boats should have a lawful home mooring, unless theywere used ‘bona fide’ for navigation. Shorthand for this isthat they ‘continuouslycruise’. Thelegislatorsdecided (and BW agreed) that it was reasonable that boats engaged in continuous journeys did not needto have a home mooring. Precisely what wasmeant in the Act by ‘bona fide navigation’ and ‘withoutremaining continuously in any one place for more than 14days or such longer period as is reasonable inthe circumstances’ has been the subject of ncreasing and sometimess acrimonious debate within theboating community since 1995.Quick facts In 2007, we had approximately 3,200 boatslicensed as continuous cruisers. In July 2012 thefigure was 4,400, an increase of37%. Thiscompares with a 12% increase in total licencesissued over the same period.Continuous cruisers currently account for c.13% ofall licencesAnalysis of our dataset of all boat sightingsbetween 1st Jan and 31st Aug 2011 suggestedthat over 2,000 boats coded as continuous cruisershadmoved less than 10km during the period.In spring 2012 were-ran our analysis toconcentrate on those boats which moved less than5 kmand we are now concentrating onapproximately 6000 boats which move the leastandare regularly sighted on visitor moorings. Theappended map shows geographic concentrationsof these boats.Theproblem weface is in enforcing ourinterpretation ofthis widely drawn legislation, whenthe only sanction provided within our statutorypowers is to remove the boat from the waterway. Inthe case of a residential boater, this would effectivelymean loss of their home. We have no desire tomake people homeless, but neither can we fulfil ourstatutory obligations of preserving waterway amenityfor public benefit in the face of large scale disregardof our interpretation of the legislation (which courtjudges find reasonable).Tension has been rising across different sections ofthe boating community about the number of boatsclaiming ‘continuous cruiser’status withoutappearing to be ‘bona fide’ navigators.On the one hand, we have the (relativelynew andsmall) National Bargee Travellers Association(NBTA) completely rejectingour interpretation of thelegislation for operational management purposes.They believe that any boater has the right to settleon the towpath within a specific area without thePage 2 of 13

need to secure a home mooring. Our attempts at constructive engagement with them to establish howthey reconcile this unconstrained‘right’ with our statutoryduty to preserve wide public benefit and amenityhave largely failed. Their activities include campaigning against our moorings policies on a number ofniche websites and internet groups, submitting successive complaintsand requests for detailedinformation (under FoI) and providing support to boaters who are within our enforcement process forfailing todemonstrate compliance with mooring guidance. †The 2,000 strong Residential Boat Owners Association also represents residential continuouscruisers(and those with a home mooring) and takes a constructive approach to the subject and has recentlypreparedits own document on the subject (http://waterwaywatch.org/rboa-produces-a-paper-on-vocal incontinuous-cruising/The Inland Waterways Association (representing c.27% of boat licence holders) isincreasinglydefending the rights of leisure boaters to enjoy access to towpath moorings for short periods during acruise. They have recently calledon us for “action on continuous moorers”.Appendix A providesa short chronology of past consultation on the subject.CorrectionMr Nick Brown made a complaint to the Waterways Ombudsman and as a result we have agreed to makecorrections to this document:† The FoI requests were made by members of theNBTA in an individual capacity andnot by the NBTA itself.2. LICENSING & MOORINGS POLICY/REGULATION- OVERVIEWAll boatsmust have a licence (average cost £700 p.a.) orriver registration (average cost £4000 p.a.) andEITHERa home mooring or be declared as a continuouscruiser in which case only the licence fee or riverregistration is paid. Licences aresubject to contractual terms and conditions which are consistent withour interpretation of our statutorypowers.The legislationSection 17(3)(c) British Waterways Act 1995 states that BW may refuse a licence (“relevant consent”)unless ( i) BW is satisfied the relevant vessel has a home mooring or: “(ii) the applicant for the relevantconsent satisfies theBoard that the vessel towhich the application relates will be used bona fide fornavigation throughout the periodfor which the consent isvalid without remainingcontinuously in any oneplace for more than 14 days or such longer period as is reasonable inthe circumstances.The language of the Act is generic and, as with all statutes, requires interpretationn. We thereforedeveloped guidance for customers based on professional legal advice, including from LeadingCounsel,which we believe reflects the correct legal interpretation of the Statute. The Guidelines updated in 2008were considered in the Bristol County Court in 2010 in thecase of British Waterways v Davies. The Judgeexpressly found that Mr Davies’ movement of his vessel every 14 days (whilst remaining on the sameapproximate 10 milestretch of canal betweenBath and Bradford on Avon) was not bona fide use of thevessel for navigation. We updated the guidelines in 2011 to reflect this judgement.In summary, the guidance says:1. theboat must genuinely be used for navigation throughout the period of thelicence.Page 3 of 13

2. unless a shorter time is specified by notice the boat must not stay in the same place for more than14 days (or such longer period as is reasonable in the circumstances);3. it isthe responsibility of the boater to satisfy CRT that the aboverequirements are and will continueto be met.A more detailed treatment of the legal context including our interpretation of ‘navigation’ and ‘place’,which is critical for operational implementation of the legislation, is at Appendix BImplementing the legislation – enforcement overviewWe employ an enforcement teamof 50 people at a cost this year of £2.18 million of which 69%are staffcosts, 16% are contract costs (for ‘Section 8’ boat removals, storage and disposal) and 9% legal fees andcourt costs. The team’s primaryfunction is to maintain a low level oflicence evasion, which reachedunacceptably high levels before 2009. Now that this is under control, greater focus is being applied toreduction of non-compliant continuous cruising.During August 2012,the enforcement team had some 640 NCCC cases in process. Because non-compliance is a breach of licencee conditions,our standard remedy is to revoke the licence andremovethe boatfrom the waterway. Thisis a long process whichh is further complicated when the boat issomeone’s primary residence, inwhich case, we obtain a court order before taking possession in order toavoid claims of unreasonable behaviour. Wehave neverbeen refused such an order in respect of anNCCC, although the number of cases reaching the final stage of process is small. Further detail of theprocesses we follow, from gathering of evidence of movement patterns over a sustained period through tosubmission of casess to our solicitors is contained in Appendix C3. GENERIC SOLUTIONSWe believe that our core policiesand enforcement procedures are sound and based on good legal advice.However, while goodenforcement is necessary for the credibility of our processes, it is not in itselfsufficient to achieve the compliance levels weneed to satisfy the great majority ofour boatingcustomersand to ensure the harmony amongst waterway users that’s needed tomaximise public benefit. Theprocess is unavoidably slow and expensive and can never be expected to achievee significant change inbehaviour by the considerable number of boaters who appear to be disregarding our rules. We thereforeneed to expand our toolkit to address the long standing non-compliance by a sizeable cohort ofcontinuous cruisers who have established their homes along the towpath in particular areas.Unofficial communities of residential boaters have taken root over theyears because they observed thatBW seemed unable or unwilling to take action to move them on. Some – or maybe many – of these donot see themselves as ‘boaters’ in the navigational sensee – they havechosen to live on a boat not in orderto navigate but to stay in the particular locality where their family, work and support arrangements are.Demanding that theyfollow mooring guidance at this latestage wouldbe futile.We havecome to recognise over the past 18months that constructiveengagement with NCCCs will bean essential ingredient of sustainable solutions and we have started work in two waterway areas to try outslightly different approaches. These are summarised in section 5 below. The difference in approacharises from particulalocal circumstances, but both are likely to draw on at least some of the followinggeneric solutions.i.CommunicationsPerception(and reality) is that our only one to one communication with NCCCs has beenthrough formal standard warning letters and notifications which of necessity set out the legalposition. Only relatively recently have we introduced an initial, more informally worded letter,Page 4 of 13

Overall cost reduction: Net reduction in costs for the <strong>Trust</strong> compared to current spend + liabilities.Reinvestment of surplus intothe project objectives and/or the <strong>Trust</strong>’s charitable objects.We have retained social enterprise and community engagement specialists, Locality (formerlytheDevelopment <strong>Trust</strong>ss Association) to lead thesupporting work programmes. Progress is being made, butis very slow, with anunderlying difficulty being that of establishing aneffectively constituted body whichcan speak for people whose motivations andobjectives vary widely. As a meansof building trust andunderstanding, we have recentlyentered into a short term ‘meanwhile’ lease for the (publicly funded)Waterside Centre at Stonebridge Lock on the Lee in Tottenham. Under this, London (residentialtowpath) boaters in partnership with three other local community groups will as tenants, develop asustainable business plan for optimising useof the centre. A ‘listening’ programme is underway, led bycommunity organisers funded through the government’s‘big society’ programmewith community conflictresolution techniques being applied. The disruption to mooring arrangements caused by theOlympicshas slowed progress as many boaters moved away fromthe area, but we are hopeful that a LondonBoatersgroup will soon achievee incorporation and the capacity to start creating social enterprise ventureswith continued help from Locality.Kennet & Avon <strong>Canal</strong> (West)We regularly observe approximately 150 boats without home moorings between Bath and Devizes whodo not comply with our mooring guidance.Our framework planissued in August has the following aims:a.b.c.d.To protect the amenity of the waterway for widest public benefitTo improve access to popular visitor moorings byboats beingused for leisure and holidaypurposes, and to stretches of ‘unmoored’ water by anglersTo provide a means by which boaterswithout a home mooring currently resident between Bathand Devizesmay continue with their chosen lifestyle without the need to move every 14 days.To clarify local rules and achieve understanding and compliance through effective, positive,communications and support, reducing dependence on requirement for exercise of legalenforcementpowers.Key elements within the plan are:1. Designate visitor mooring stretches; sign them clearly at start and end points; specify‘returnrules’ in the form of max. x days within any calendar month.2. Extended stay charges for breachingtime limits at visitor moorings. Sufficiently frequent sightingssby professionally recruited paid stafff to support this – warningnotes c. 24hours ahead of whenextended stay charge kicks in.3. New type of“Community” mooring permit for continuous cruisers who have been recorded by the<strong>Trust</strong> as being resident on the towpath in July 2012. Approx. 20 locationseach accommodatingup to c.10 boats to be designated where permit holders can stay for up to28 days at a timebefore moving on to another one – or any other length of towpath providing they comply with therules for that location.i.ii.Subject to an annual feee pegged to a percentagee of the average rate for our directlymanaged sites in the area.Permit holders will be treated as having a home mooring andpermits will be subjectto all applicable terms ofthe mooringagreement for our directly managedmoorings.Page 7 of 13

4.5.6.iii.iv.Eligible for a discount onwinter mooring fee (i.e. where you can stay put for 5months)Not assignable – only available to existing licencee holders (not their boats) who havealready established ‘residency’ in thearea. Eventually, the number of ‘community’berths will decline as people move away naturally.Define neighbourhoodsfor boaters without homemoorings and, using additional <strong>Trust</strong> resources,enforce continuous cruising rules (14day limit) using existingprocessesTowpath presence – current enforcement processes apply but a community worker tobeemployed for a fixed termto help with communications and tosupport boaters to in resolvingpersonal difficulties. (Weare planning to supportan extension the Waterways Chaplaincy and atemporary mooring warden for this purpose)Signage, maps and other informationn published in paper andelectronically.We have placed thisframework plan on our extranet for the waterway partnership and navigationadvisory group and have mailedit to national boating organisations and those involved in lastyear’sconsultative process. IWA, RBOA and APCO had requested updates on progress prior to completion ofthe planand we took those opportunities to share the detail before publishing. On the basis of theseinformal discussions, we believee that the approach, if wesucceed in implementing it, will meet wideapproval from traditional leisure boaters, theboating trade and manyresidential boaters.Implementation detail, particularly the decisions on zoning different stretches for visitor/community/no-moorings, is the next significant challenge. The waterway partnership has agreed to developadvice forus on these and other detailed aspects for which good local knowledge and perspectives areessential.It appears that the partnership will require support in the form of a professional facilitator for this work andwe are in the process of appointing a suitable contractor.5. RESOURCINGWe havecommitted £33k for thecurrent year to consultancy and community capacity buildingfor London,and a further sum (up to c.£5k) may need to be committed for completing the implementationplan for K&Amoorings. These sums are within current budget provision.Our Enterprise teamwill work with Workplace Matters toseek external funding for communitysupportwork for the K&A during the implementationphase for the new mooring plan once it is confirmed.Once we are ready to implement, signage costs will be the major itemof expenditure but the scale of costis dependent on thenumber of locations which is not yetknown. Assuming that the uptake of theCommunity Mooringpermit proposal is in line with our predictions, income from permit sales should morethan cover these and other setup costs.We anticipate that local partnerships may identify other problem areas needing specific NCCC strategies.Where the geographical scope is quite limited, a simple approach of updating visitor mooring signageand implementing extended staycharges may be sufficient. Elsewhere, there may be need forapproaches akin to our two existing project areas. We need to factor in this contingency intothe 2013/4business planning round.We are not planningat this stage to cut the budget for legal fees associated with enforcement cases.Whilst we hope thatt the need for legal actionwill declinee as the ‘softer’ initiatives outlined in this paperstart to bear fruit, it is important to maintain the deterrentt effect of legal enforcement.Page 8 of 13

APPENDIX A: CHRONOLOGY OF CONSULTATIONACTIVITIES,2002 - 2012With the passing of the British Waterways Act of 1995, BW was empowered to refusee to licence a boat whichdid not havea home mooring – unless the boat was used ‘bona fide for navigation’, ‘not staying inthe sameplace for more than 14 days’. In signing a licencee application, the boater confirms a commitment to “bona fidenavigate” if there is no home mooring. Growth inresidential boating had already started at this time, andestablishment of small groups of boats within a limited area inLondon, onthe westernK&A, southern GU andother suburban areas was becoming a feature ofthe local canal landscape.In 2004, following public consultation, we introduced mooringguidance for continuouscruisers which set outBW’s interpretation of thelegislation to help thosewithout home mooringsto comply with the Act.The absencee within the statute of clear definitionsof ‘bona fide navigate’ and ‘place’ contributed togrowth innon-compliant continuous cruising (NCCC) , as did growing evidence of a shortage oflong term mooringprovision. As a possible means of stemming growth in NCCC, consideration was given in 2002/3,in 2005/6and again in2007 (by BWAF) to modifying the licence fee structure so that those without a home mooringwould pay significantly more for their boat licence. No national boating organisation supported this approachin the associated public consultationss and the plan was dropped.The shortage of affordable housing inthe South East is a major driver to acceleratingdemand for boats forresidential use, and people buy boatsto live on without securing a home mooring because they know they can(usually) ‘get away with it’. We recognise the need for increased provision of long termresidential moorings,and a statement by the housing minister in August 2011 was helpful in encouraging local planningauthoritiesto take a more supportive stance, confirming thatt the New Homes Bonus is payable inrespect of residentialmoorings. The property director is leading a project to createe new residential moorings in London.We last consulted on thissubject during 2009 and in 2010 updated our national moorings policies as a result.We then attempted to implement newmoorings control processes as outlined in the policy throughhdevelopment of local mooring strategies for the western end of the K&A and the <strong>River</strong>Lee.For the former, we established a steering group representing all types of local boater and parish councils.After nearly a year of discussions, there was littleconsensus,but we tookuseful outputs from their work andhave recently published our framework plan on which <strong>Trust</strong>ees were briefed during their July meeting.In February2011, in an endeavour to fast track progress in London, we presented for public consultation atentative mooring plan which definedd movement requirementsfor continuous cruisers in the Lee Valley. Thistriggered vociferous opposition by unaffiliated residential boaters living along the towpath and an effective PRcampaign against our proposals. Weshelved theproposals in August 2011 in favour of a strategyofengagementwith boaters concerned with the aimof establishing a more effective social enterprisee model forcreating a happier environment for all on London’s waterways.This is a long standing issue, but the leisureboating community, the boating trade and some land based communitiesare increasingly concerned aboutthe impact on their enjoyment of boating of increasing number of residential boats tying up for longperiodsalong the towpath in the same place in some areas of our network. Theree is an increasing polarisation ofviews and the creation of the <strong>Trust</strong> has raised expectations that policy will be developed to progress thisissue.Page 9 of 13

APPENDIX B: LEGAL BACKGROUND – MORE CONTEXTTSection 17(3)(c) British Waterways Act 1995 states that BW may refuse a licence (“relevant consent”) unless(i) BW is satisfied the relevant vessel has a homemooring or: “(ii) the applicant for therelevant consentsatisfies the Board that the vessel to which the application relates will be used bona fide for navigationthroughout the period forwhich the consent is valid without remaining continuously in any one place for morethan 14 daysor such longer period as is reasonable in the circumstances.The language of the Act is generic and, as with all statutes, equires interpretation. We therefore developedguidance forcustomers based on professional legal advice, including fromLeading Counsel, which we believeereflects the correct legal interpretation of the Statute. The Guidelines updated in 2008were considered in theBristol County Court in 2010 in the case of BritishWaterwaysv Davies. The Judge expressly found that MrDavies’ movement of hisvessel every 14 days (whilst remaining on the same approximate 10 milestretch ofcanal between Bath and Bradford onAvon) was not bona fideuse of the vessel for navigation. Weupdatedthe guidelines in 2011 toreflect this judgement.In summary,the guidance says:1. the boat must genuinely be used for navigation throughout the period of the licence.2. unless a shorter time is specified by notice the boat must not stayin the sameplace for more than 14days(or such longer period as is reasonable in the circumstances);3. it is the responsibility of the boater to satisfy the <strong>Trust</strong>that the above requirements are andwillcontinue to be met.It provides definitions as follows:“Navigation” means travelling on water involvingmovement in passage or transit. We put reliance on themeaning given to the word in the case of Crown Estate Commissioners v Fairlie Yacht Slip Limited. Whilst adecision of the Scottish courts, the English courtscan, and have, taken the views of the Scottish Judge intoaccount. In that case thebasic concept and essential notion of the word “navigation” was said to be “passageor transit”, the underlyingconcept being one of movement.“Place” means a neighbourhood or locality, NOTsimply a particular mooring site or position. The ShorterOxford Dictionary gives some 8 separate principal meanings for the noun ‘place’. Therefore the rules of legalinterpretationn require themeaning that most appropriately fitsthe context to be used. Since ‘navigation’ meanstravelling by water and ‘travel’ meansa journey of some distance, the word ‘place’ in this context is used bythe Act to mean an “areaa inhabited or frequentedby people, as a city, town, a village etc” (meaning 4b in theShorter Oxford Dictionary).And the guidance which follows fromthe above is:to remain in the same neighbourhood formore than 14 days is not permitted. The necessarymovement from one neighbourhood to another can be done in one step or by short gradual steps.What the law requires is that, if 14 days ago the boat was in neighbourhood A, by day 15 it must be inneighbourhood B. Thereafter, the next movement must normally be to neighbourhood C, and not backto neighbourhood A (with obvious exceptions such asreaching the end of a terminal waterway orreversing the direction of travel in the course of a genuine cruise) .Page 10 of 13

What constitutess a ‘neighbourhood’ will vary from area to area – on a rural waterway a village orhamlet may be a neighbourhood and on an urban waterway a suburb or district within a town or citymaybe a neighbourhood. A sensible andpragmatic judgement needs to be made.It is not possible (nor appropriate) to specify distances that need to be travelled, since in denselypopulated areas different neighbourhoods will adjoin each other and in sparsely populatedareas theymaybe far apart(in which case uninhabited areas between neighbourhoods will in themselves usuallybe a locality and also a “place”).Exact precision is not required or expected – what is required is that the boat is used for a genuinecruise.Circumstances where it is reasonable to stay in one neighbourhood or localityfor longer than 14 daysare where further movement is preventedby causes outside the reasonable control of theboater.Examples include temporarymechanical breakdown preventing cruising until repairs are complete,emergency navigation stoppage, impassable ice or serious illnesss (for which medical evidence maybe equired) Such reasons should be made known immediately tolocal <strong>Trust</strong> enforcement staff with arequest to authorise a longerstay at the mooring site or nearby. The circumstances will bereviewedregularly and reasonable steps (where possible) must be taken toremedy thecause of the longer stay– egrepairs put in hand where breakdown is the cause. Where difficulties persist and the boater isunable to continue the cruise, the <strong>Trust</strong> reserves the right to charge mooring fees and to require theboatto be moved away from popular temporary or visitor moorings until the cruise can recommence.Unacceptable reasons for staying longer than 14 days in a neighbourhood or locality are a need tostaywithin commuting distance of a placeof work or of study (e.g. a school or college).The law requiresthe boater to satisfy us that the bonafide navigation requirement is and will be met.It is not for the <strong>Trust</strong> to provethat the requirement has not been met. This is best done bykeeping acruising log, though this is not a compulsory requirement. If however, we gaina clear impression fromour regular boat sightings that there has been limited movement insufficient tomeet the legalrequirements, wecan ask for more information to be satisfied in accordance with the law. Failure orinability to provide that information may result in further action being taken, but only after fair warning.Failure then to meet the movement requirements, or to provide evidence of sufficient movement whenrequested, can be treated asa failure to comply with s.17 of the 1995 Act. After fair warning the boatlicence may thenbe terminated (or renewal refused). Unlicensed boats must be removed from CRTwaters, failing which the <strong>Trust</strong> has powerto remove them at the owners cost.In any case where the boat isthe licencee holder’s primary residence, we seeka court order beforeexercising these powers. This provides the judge with the opportunity to consider the proportionalityof the sanction inthe contextt of the Human Rights Act. In the small number of cases that havecompleted the full course of our enforcement processes and reached the lawcourts, judges havealways upheld our case.Page 11 of 13

APPENDIX C: THE ENFORCEMENT PROCESSSFor the control of both licencing and mooring, all boats are monitored every 2-4 weeksregardless of theirmooring status. ‘Data checkers’ walk each stretch of towpath at least twice monthly. A ‘sighting’ isrecorded using GIS enabled hand-held devices – the boat’s index number, date and location is recorded.Sightings of boats without a home mooring are analysed regularly to buildup a pictureof their movementsover time. Inlocations where the same boats aresighted repeatedly and consistentlyin the sameplace, morefrequent visits will be made to help us form a viewof whetherthe guidance for boats without a home mooringappear to bebeing breachedWhere a boat is left on inland watersowned or managed by the <strong>Trust</strong> without lawful authority, we havestatutory powers to remove it. If the boat is sunk, stranded orabandonedd on our waterways, a statutory noticecan be served under Section 8 of theBritish Waterways Act 1983 permitting us to remove the boat after aminimum of 28 days’ notice. We canalso serve notice underSection 13 of the BritishWaterways Act 1971 toremove a houseboat that is moored unlawfully orwithout a valid licence after a minimum of 28 daysnotice. The procedure that is followed in each case will depend on whether the boat is occupied (“liveaboard”)or not:Liveaboard Procedure Our policy isto serve a series of letters on the owner/occupiewarning them of theconsequences of failure to remove the boat. Thiscorrespondence takes several months and gives theowner/occupier ample opportunity to remedy matters and discuss any queries with the<strong>Trust</strong>. If, despite theopportunitiesafforded, the boat remains on <strong>Trust</strong>waters without lawful authority, we will serve statutorynotices under Sections 8 and 13 (seee above).Upon expiry of the minimum 28 day notice periodthe <strong>Trust</strong> will notify the owner/occupier that the file is beingtransferred to solicitors toissue Court proceedings. Court proceedings are then issued for declaratory andinjunctive relief and are served on theowner/occupier. The owner/occupier has then an opportunity to defenddthe case andhave a fair trial on the merits. The Court can then review the procedure followed and determinethe scope (ifany) of the relief grantedto us.In most cases however, once the enforcement procedure commences theowner or occupier of the boatremoves it from the water, obtains a mooring or starts to follow the mooring guidance before we reach thestage of issuing legal proceedings. Cases are generally labour intensiveNon-liveaboards Where a boat is sunk, abandoned or otherwise not occupied, the <strong>Trust</strong> will serve a noticeunder Section 8 requiringremoval from its waterswithin 28 days. If the notice is not complied withwe canremove the boat from itswaters without issuing Court proceedings. Both of these procedures are humanrights compliant.The overwhelming majority of continuous cruiser enforcement cases which we open are resolved or closedwithout reaching court. We have sent a total of 19 cases to our solicitors since March2009. Of these:o 4 settledin court in our favouro 4 awaiting hearing dateo 5 resolved without going to courto 6 remain in processso The average costs incurred for the 11 cases closed and billed up to July 2011 isapproximately £8,100Page 12 of 13

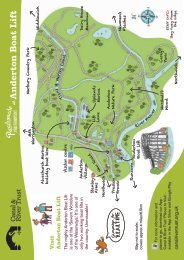

APPENDIX D: HOTSPOT MAP OF PRIORITY NCCCsPage 13 of 13