Download This Issue (PDF) - catalyst-chicago.org

Download This Issue (PDF) - catalyst-chicago.org

Download This Issue (PDF) - catalyst-chicago.org

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

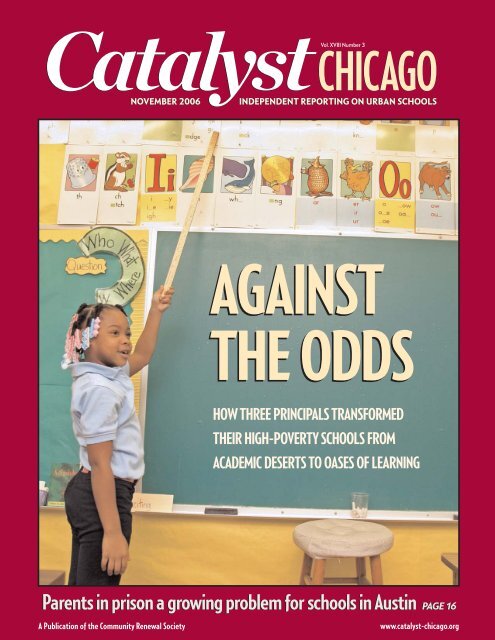

NOVEMBER 2006Vol. XVIII Number 3CHICAGOINDEPENDENT REPORTING ON URBAN SCHOOLSAGAINSTTHE ODDSHOW THREE PRINCIPALS TRANSFORMEDTHEIR HIGH-POVERTY SCHOOLS FROMACADEMIC DESERTS TO OASES OF LEARNINGParents in prison a growing problem for schools in Austin PAGE 16A Publication of the Community Renewal Societywww.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong>

FROM THE EDITORSuccess begins with the principalVeronica AndersonPublic schools that overcome the colossalodds that go hand in hand with extremepoverty must have a number of thingsworking in their favor. Five things, to beexact, as has been proven time and time again byresearch and experience. Among them are parentand community partners that rally around effortsto improve the school and a faculty of qualifiedteachers who have a can-do attitude.Two others are a safe and orderlyenvironment where children canlearn in peace, and a challengingcurriculum that builds on skills studentslearn each year.Yet, individually and collectively,these “essential supports” would beaimless and ineffective if it were notfor the most crucial factor of all: Aprincipal whose leadership sets highstandards and provides the chargethat motivates others to get onboard, improve themselves andmove in the right direction.A recent report on public schoolreform in Chicago underscores theimportance of these key ingredients.Published by the Consortium onChicago School Research, the reportnotes that students enrolled atschools with such supports are 10times more likely to post significantgains in math and reading.Researchers also measured the effectsof outside factors—such as crime,homelessness and whether childrenare in foster care—on public schoolimprovement. They found instancesof improvement even in the worstcommunities, but noted thatimprovement is much more difficult,even with the five supports in place.In this issue, we feature three publicelementary schools in Chicago—all with poverty rates that are aboveaverage—that have undergone dramatictransformations under theleadership of a dynamic principal.Contrary to ongoing debate aboutlocal versus central control, it didn’tseem to matter who hired the principal.Local school council membersmade the choice at Marsh Elementary;the district handpicked the principalat McCorkle. At Peirce, the principalwas chosen by a regional administratorunder a now-defunct process.What mattered is what the principalsdid once they got the job and, itseems, how long they stayed. (Two ofthe three remained at the helm oftheir school for more than 15 years.The third is in her tenth year.)Janice Rosales tackled student disciplinefirst and made connectionswith the growing immigrant populationin Edgewater whose childrenattended Peirce. She spoke Spanish;her predecessors did not. On thisfoundation, she built a team of teachers,many of them nationally certified,and extended the school day an extrahour to spend more time on readingand math instruction. Since 1990, passrates on reading tests have doubled.Discipline was also key to GeraldDugan’s success at Marsh, where firecrackersand gang graffiti were commonplacewhen he arrived. He partneredwith parents so they would helphim crack the whip on unruly students.Dugan also persuaded teachersto raise their expectations about students’capabilities and stepped upinstruction in all subjects. Like Peirce,pass rates more than doubled.Janet House, whose tenure asprincipal is the shortest of the three,came to McCorkle with the perfectset of skills to turn the school around.She had worked at the district for arespected accountability chief andthen taught at a high-performingschool in Grand Boulevard, home toMcCorkle. Her first move was tospruce up hallways and classroomswith plants and student art, then shemoved on to raising standards inbehavior and providing moreteacher training. Again, scores wentup and mobility went down.So the key is making sure everyschool has a strong principal. That’seasy to say, and CPS has made principaldevelopment a priority. It’shard, though, to see where thoseefforts have paid off. Accountabilityrequires the district to assess its ownprogress and share the results.ABOUT US I am pleased to welcomeour newest group of editorial boardmembers: Maria Vargas, counselor,Lloyd Elementary; Marvin Hoffman,principal, North Kenwood OaklandCharter; Guadalupe Martinez, principal,Latino Youth Alternative HighSchool; Keri Blackwell, program officer,Local Initiatives Support Corp.;John Paul Jones, director of communityoutreach, Neighborhood CapitalBudget Group; Steve Zemelman, IllinoisNetwork of Charter Schools;Peter Martinez, director, UIC’s Centerfor School Leadership; JuliaMcEvoy, education editor, ChicagoPublic Radio; and James Wagner,president, DuSable High SchoolAlumni Coalition.2 Catalyst Chicago November 2006

SUCCESS STORIESHow the good schools do itEach school has a different story, but italways takes a savvy principal to bringin the right mix of good teaching, acommitted staff and parental support to turnaround a failing school. COVER STORY: PAGE 6A YOUNG PRINCIPAL TAKES CHARGE AT PEIRCEJanice Rosales began a dramatic turnaround and thenhanded the reins to a successor who’s earned the dedicationof her teachers. PAGE 8TEAMWORK DRIVES UP SCORES AT MARSHGerald Dugan was hired by the first local school council andreached out to make parents and teachers partners in schoolimprovement. PAGE 10PROBATION BRINGS A BIG PAYOFF AT MCCORKLEJanet House was sent by central office to replace an oustedprincipal and brought in professional development and anoutside partner. PAGE 12JASON REBLANDOON THE COVER: Second-grader Yanikki Hoskins (also pictured above, ina classroom reading corner) leads her classmates in a lively phonics drill atMcCorkle Elementary.JOE GALLOAlice Jackson, who runs a halfway house for women in Austin,helps care for two grandsons whose parents are incarcerated.See Neighborhoods, page 14.DEPARTMENTSNEIGHBORHOODS Page 14• Austin: A place of extremesUPDATES Page 20• Peer evaluation makes debut• Task force to count, reclaimdropouts• More master teachers inpoorest communitiesNotebook 4Viewpoints 23Comings & Goings 24ON OUR WEB SITEGo to the Catalyst web site,www.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong>,for news and resources on Chicagoschool reform, including:• Spanish translations• Reform history news highlightswww.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong> November 2006 3

NotebookTIMELINEOct. 5: Test delaysState Supt. of Schools RandyDunn acknowledges that thestate is not likely to meet therequired Oct. 31 deadline fordelivering school reportcards, including test resultsand other information, toparents and the generalpublic. Scoring problemsand last spring’s late deliveryof the tests to schools are toblame. The state board votesto penalize test publisherHarcourt Assessment andtransfer most of the firm’sduties to Pearson EducationalMeasurement.ELSEWHERELos Angeles: Military leaderAn ex-Navy admiral with no educationbackground will be superintendent of theL.A. Unified School District, according to theOct. 13 Los Angeles Times. Mayor AntonioVillaraigosa said he was “deeply disappointed”that the School Board chose retired ViceAdm. David L. Brewer III without includinghim in the process. Villaraigosa and theboard had clashed over how much authorityhe would have over the selection. A new lawgiving the mayor veto power over the hiringof the superintendent, and substantial controlover the district, will go into effect Jan. 1,2007. The district is challenging the law.Ohio: Increase fundingOct. 7: Rivals agreeOhioans say the state should increasespending for public education, according toa new poll reported in the Oct. 3 ClevelandMayor Richard M. Daleyand Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr.(D-Ill.) join education leadersto call for more statefunding for education, sayingthe issue transcendspolitics. Funding reform hasso far not been a majorissue in the race for governor.Incumbent Gov. RodBlagojevich and GOP challengerJudy Baar Topinkahave both said they wouldnot raise the state incometax, a move that educationadvocates say is essential tofunding reform.Oct. 12: More gradsThe Consortium on ChicagoSchool Research revisesnumbers from its recentstudy on college graduationrates for CPS students, butsome of the corrected figuresare still dismal. The studysaid only 6 percent of CPSgraduates earn collegedegrees by their mid-20s, butthe Consortium now says thefigure should be 8 percent.The percentage of all CPSgrads who eventually earn adegree was originally reportedas one-third, but the newfigure is just 45 percent.Plain Dealer. About 80 percent of respondentssaid they want more money for education,more than the percentage that saidthey wanted more funding for economicdevelopment, courts and prisons, or healthcare for elderly and the poor. A majority ofrespondents also said they oppose the useof public money for private school vouchers.Texas: Bonuses rejectedMore than two dozen schools turned downstate grants for a merit pay program forteachers, reports the Oct. 3 Dallas MorningNews. The program gives teachers theauthority to approve the plan at theirschools. Teachers at schools that turneddown the money said the program wouldcreate animosity and division among staffand was too time-consuming to administer.The program calls for low-income schoolsto distribute bonuses based on test scores.IN SHORT“You can save a lot of grief and money if teachers understand thekinds of minds in their classrooms.”Dr. Mel Levine of the University of North Carolina Medical School, on how school districtsmight benefit if teachers knew how the brain functions and adapted lessons toaccommodate children’s strengths and weaknesses. Levine spoke at an Oct. 5 luncheonhosted by High Jump, an enrichment program for middle-school students.Q&Awith ...Syrennia McArthur HanshawSouth Side ParentsSouth Side Parents was launched lastyear by a small group of parents whonoted an abundance of informationsharingabout schools on the North Sideand wanted to launch a similar network.The group now has 79 members andcovers Woodlawn, Douglas, Kenwood,Hyde Park, South Shore, Oakland andpart of Washington Park. The Universityof Chicago is helping the <strong>org</strong>anizationprepare a booklet on schools, ChicagoPark District programs, and daycarecenters. Syrennia McArthur Hanshaw,vice-chair of communications and themother of three children at North KenwoodOakland Charter School, spokewith Associate Editor Debra Williams.What is your philosophy on parenting?Children have to have strong parent involvementin everything. Parents should be there notjust to drop them off [at school] and come toconferences and meetings but to participate inan active way, to volunteer. I know parents workand it’s hard, but they need to do it. All schoolsshould have mandatory volunteer time.Do you think the district pays attentionto parents?If you make a lot of noise (laughs). That’sthe only way. I don’t mean in a rambunctiousway. I just mean in a persistent way. But youalso have to present the district with solutions.That’s the best way to get results.You say parents have to make a lot ofnoise. But what would you like the districtto do to get parents more involved?Have quarterly parent meetings with allthe schools. There’s a lot of segmentation[among] schools, and they are kind of operatingindependently. Maybe the schools in Area15 or Area 16 can get together, for instance.We share similar concerns, I think.Teachers complain that some kids cometo school hungry or need discipline. Areparents accountable? What can be doneto hold them accountable?Parents are accountable, but some sufferfrom a lot of social needs. I don’t think most parentswould send their kids to school hungry ifthey really had the means to feed them. Also, youcan’t have a job where you have to be at work at4 Catalyst Chicago November 2006

ASK CATALYSTIt’s difficult to get good teachers at low-performing schools. Whydoesn’t CPS offer bonuses to teachers who take jobs at lowperformingschools and raise test scores?Tony Wilkins, community representative, Canter Middle SchoolJASON REBLANDO7 o’clock and your child has to be at school at8:30. It just doesn’t work—parents end up bringingkids to school and they haven’t eaten.Still, schools should make contracts withparents. The contract should be, “We’re going todo the best we can to provide a good educationfor your children in a safe and healthy environment,and we expect you to facilitate what istaught, to make sure children come to schoolon time and to help them with homework.”Even if a child is taught something, if they’re nothaving it reinforced at home, they’re more thanlikely not going to remember it.Do the parent boards at charters haveenough input? Would you like to see yourboard become a local school council?No. LSCs have become too political. That’smy observation. I think they can have a positiveeffect, but most of what I see is negative. I hada friend who was president of an LSC, and shesaid it was a hassle—she couldn’t get positiveparental involvement and it was a lot of politics.CPS recently applied for a $29 million federal grant to give bonuses to staff at strugglingschools that improve test scores. The program would start in 10 schools next yearand expand to 40 by 2011. Bonuses for teachers would average about $4,000 andwould be based on a performance evaluation, test score growth in the classroom andschoolwide score gains. Schools will have to obtain the approval of 75 percent of thefaculty to participate.Chicago Teachers Union President Marilyn Stewart opposes merit pay in general,saying too many factors that teachers can’t control, such as parental support, have animpact on student achievement. Better working conditions, such as lower class sizes,would do more than bonuses to attract and keep good teachers in underperformingschools, she insists.Paying teachers based on student performance is a growing trend. Florida, Texasand Alaska recently adopted cash bonuses for teachers based on student test scores.E-mail your question to or send it to Ask Catalyst, 332 S. Michigan Ave., Suite500, Chicago, IL 60604.MATH CLASSAfrican-American and Hispanic students are underrepresented in gifted programs in Illinois, whilewhites are overrepresented, according to data from the Illinois State Board of Education. In 2003(the latest data available), enrollment in gifted programs was 12% black, 8% Hispanic, 74%white and 6% other races, primarily Asian. However, statewide student enrollment is 21% black,17% Hispanic, 58% white and 4% Asian/other.FOOTNOTEBut an advisory board doesn’t choose aprincipal and manage a budget.We have a parent-teacher community<strong>org</strong>anization that does have input into thebudget and things like that.What advice do you have for schools tobring more parents into the building?Always have something going on. Last weekwe had “Bring your parents to school” night forthe pre-K through 1st grade, and they had adinner. We’re having a “house-hop” with housemusic and dancing. We had our first parentteachermeeting at Lucky Strike, the bowlingalley. We mingled with [new parents] and got toknow them.For info, go to www.southsideparents.<strong>org</strong>. •KURT MITCHELLwww.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong> November 2006 5

COVER STORY SUCCESS STORIESHow the goodschools do itBy Elizabeth DuffrinThe recipe for successfulschools is:Mix one strongleader with parentand communitysupport, astrong teaching staff, a schoolclimate that supports learningand high-quality instruction.These are the “five essentialsupports” for learning, noted indecades of research on effectiveurban schools and outlinedonce again in a September2006 report from the Consortiumon Chicago SchoolResearch. Schools with strongsupports were 10 times morelikely to make significant mathand reading test score gains,the Consortium found. (Thenew report covers 1990-96, theyears following the enactmentof the first School Reform Act.)The report adds a newdimension to the Consortium’sprevious research by quantifyingthe influence of neighborhoodcharacteristics, such ascrime rates and religious participation,on school success,as well as the impact of eachsupport on achievement.Progress is still possible underProfiles of three schools show how learning improves whentop-notch principals use the right mix of ‘essential supports’to build a foundation for academic achievementTHE 5 ESSENTIAL SUPPORTSLeadership is inclusive, <strong>org</strong>anizedand sets high standards for instruction.Parents and communityare partners in improving studentlearning and participate in schoolevents.Teachers are continually learning,have a “can do” attitude and a commitmentto school improvement.Safety and Order prevail inand around the school. Classroom disruptionsare minimal.Instruction is challenging, <strong>org</strong>anizedwithin and across grades and tiedto standards.To read the full report, go towww.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong>the direst circumstances,researchers found, but is farmore difficult to achieve.Consortium Co-directorPenny Sebring notes that thenew evidence bolstering theessential supports comes at atime of massive principal retirementsthat leave the progressof many schools in the hands ofuntried leaders. “Many havenot been principals before,”she notes. “The results of thisstudy provide a useful guide inhow to proceed.”A 2005 report from thereform group Designs forChange that identified elementaryschools with substantialreading improvement alsonoted the importance of thefive supports. (An update ofthe report will analyze achievementin charter and Renaissanceschools and is due to bereleased by January 2007.)Catalyst Chicago profiledthree of the 144 schools in theDesigns report—Marsh inSouth Deering, Peirce inEdgewater and McCorkle inGrand Boulevard—and foundthat while each school had adifferent mix of the five supports,the principal was,indeed, the spark that led todramatic transformation.Each principal arrived by adifferent route. Gerald Duganwas selected by the localschool council at Marsh. Centraloffice placed Janet Houseat McCorkle. A subdistrict officerchose Janice Rosales atPeirce from among three candidatessubmitted by a parentadvisory council.As crucial as a good principalis, other factors are alsocritical. With the first SchoolReform Act, “principals got thepower to select teachers withoutregard to seniority,” saysDonald Moore, executivedirector of Designs for Change.“Schools received flexibility in[selecting] curriculum andsubstantial discretionary dol-6 Catalyst Chicago November 2006

JASON REBLANDONatalie Wallace (left), Charles Cunningham, Kaitlyn Carro and Gabriel Inseria-Mousin discuss a novel in their 5th-grade class at Peirce. Tokeep instruction challenging, teacher Tiffany King chooses novels to match the reading levels of her various reading groups.lars.” All these freedomshelped Marsh, Peirce andMcCorkle move ahead.Racially diverse schoolslike Peirce and predominantlyLatino schools like Marshwere more than twice as likelyto show substantial improvementduring the early years ofschool reform, compared toschools like McCorkle thatwere located in the most disadvantagedcommunities,according to the ConsortiumIts report points out what itcalls a “cruel irony” for schoolsin the most disadvantagedcommunities, where largenumbers of children are likelyto live under stressful conditionsthat hamper learning,such as in homes where theyare abused or neglected:These schools are most likelyto need strong supports, yetare less likely to develop them.Of the schools in theDesigns report, only 25 percentare predominantlyAfrican-American, while 43percent are predominantlyLatino and 32 percent areintegrated or mostly white.Some of the schools had onlymodest gains, and at least two,Farren and Grant, were closedfor poor performance.JOIN THE DISCUSSIONThe Consortium found thatschools in middle-incomeneighborhoods made academicprogress even whentheir supports were weaker,while schools in the poorestneighborhoods, like McCorkle,needed exceptionally strongsupports to move ahead.In all three schools,progress came gradually andprincipals remained on boardfor the long haul. Peirce’s principalhand-picked her successor.Teachers stressed theneed for stable leadership. “Ifthe leader is strong, continuityCatalyst wants to know what’s been working for you.• What methods have been used to increase test scores at your school?• What pitfalls did you encounter along the way?• What suggestions do you have for schools that want to improve?Go to www.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong> and click on the icon that says“discuss this story.” Or e-mail editor@<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong>.is really important,” agreesSebring. “If the leader leavesand is not replaced by someoneequally strong, thenthere’s a problem.”As crucial as the principalis, it would be a mistake toassume that school improvementrequires “some superhuman,charismatic, turnaround-by-sheer-force-of-personalityperson,” cautions KatiHaycock, director of the EducationTrust, a national groupthat works on improvingachievement in low-income,minority schools. But, sheadds, it does take “somebodywho’s very determined, veryfocused, who can build a senseof shared mission and focus.”Research by the Trust indicatesthat parental involvementis less important, Haycockadds. Yet parents areessential for sustainingimprovement, especially if theprincipal changes. “It’s aboutbuilding an appetite for excellencein the community.”To see how four other schoolsimproved test scores, go towww.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong>To contact Elizabeth Duffrin, call(312) 673-3879 or send an e-mail toduffrin@<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong>.www.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong> November 2006 7

COVER STORY SUCCESS STORIESMarsh ElementaryTeamwork drives up scoresAs teachers gain more input into school decisions, academics and school climate improveBy Elizabeth DuffrinSource: CPS, 2005 IllinoisState School Report CardsWhen Marsh’s local schoolcouncil hired Gerald Duganas principal in 1990, his reputationas a skilled administratorand his Spanish-speaking ability werekey selling points.The South Deering school served aMexican immigrant community, but onlyone previous principal, who stayed just ashort time, spoke the language. Dugan,then a district administrator, had theright credentials and impressed thesearch committee, recalls teacher JudithMims, who was on the LSC.Teacher Leatha Brooks, who was alsoacting assistant principal, was itching totake a firmer hand with discipline. Brookssays she “had a gut feeling” Dugan wasthe right choice to support her effortswithout micromanaging.Tougher discipline was sorely needed,teachers recall. Chaos reigned at Marsh:Kids tossed eggs at the school’s brick walls,tagged the doors with gang graffiti, threwpaint from the windows onto teachers’ carsin the parking lot and set off firecrackers inclassrooms. Childrendubbed theMARSH, 2005 school “HarshMarsh.”ENROLLMENT 670“My first yearAVG. CLASS SIZE* 29here, I was goingLOW-INCOME 88%to write a book,”WHITE 4%says teacher LindaOstoich, whoBLACK 5%LATINO 91%arrived at MarshITBS READING (since 1990)in 1988.Rose from 25% to 54%“ H a r s hISAT (ALL TESTS)**Marsh” is a farRose from 50% to 59%different place*Grades K, 1, 3, 6 and 8. today, with test**1998-99 was the first scores above theyear the state administered city average andthe Illinois Standards a calm atmos-Achievement Test.phere. Theschool is nowpart of a districtinitiative to reward higher-performingschools by giving them more autonomy.Dugan is still at the helm 16 years laterand has had an unusually long tenurefor a principal in Chicago Public Schools.Fifth-grade teacher Beatrice Winters contrastsMarsh with her previous school,which she recalls had five principals infive years. “Every year, you could see theschool go down a peg,” says Winters.“Because we’ve had a consistent administration,there’s follow-through fromyear-to-year rather than change all thetime. That has made a difference.”Besides stable leadership, teacherscredit staff teamwork, a better curriculumand parental and community support(which helped the school get amuch-needed addition to relieve overcrowding)with fueling the turnaround.Schools like Marsh that began toimprove in the first wave of school reformwere more likely to be located in a communitywith strong social networks,according to a recent study by the Consortiumon Chicago School Research. Teacherssay South Deering is just such a place,with families who have deep roots in theneighborhood and value education.Many teachers have developed closebonds with the neighborhood as well aswith each other. “Some have been workinghere so long they’re teaching the children’schildren,” says reading teacherCarlos Bañuelos. “The families now trustus and invite us over to the fiestas.”Dugan “is just relentless in his quest forexcellence,” says Thomas Avery, Area 18instructional officer. “He is a fantasticinstructional leader. And he covers thewaterfront, making teaching a priority,making sure that students are learning andcomfortable and that parents feel goodabout having their children at the school.”FIVE SIMPLE RULESDugan recalls feeling excited about takingon Marsh’s challenges. The first time hewalked up to the vintage building, he wasWHAT IT TOOKMarsh Elementary in South Deering went from beingchaotic and undisciplined in the late-80s to becomingone of the higher-performing schools in the district.These are a few lessons learned along the way:• Stable leadership brings consistent improvement• Parents need to be partners in discipline• Teachers should have input on curriculum, hiringand spendingstruck by the graffti-marked doors and tallweeds poking through the cracks in thefront steps. “It was horrible,” he says. Withhelp from the district office and the building’sengineer, Dugan got the weedscleared away and the doors scrubbedclean by the time school opened.Brooks became assistant principaland was given authority over discipline.At first, some parents whose kids misbehavedgot defensive at efforts to enforcethe district’s Uniform Discipline Code,but Dugan says the school eventuallywon parents over by making them partnersin discipline decisions.“We never suspend a child on the firstoffense. We have a conference with parentsand ask for their support,” he says.“If they know that you care about theirchild and you want to work with them,you get their cooperation 99 percent ofthe time. You lose the trust of your parentswhen you haven’t involved them.”Dugan also hired outside trainers tohelp teachers craft their own approach toclassroom management. “[If] they don’tfeel a part of it, there’s a tendency not tosupport it,” he notes.After discussions in small groups, thefaculty unanimously agreed that theywould post and enforce five rules throughoutthe building: Follow directions, berespectful of yourself and others, handlematerials appropriately, come preparedfor class activities and cooperate.Another strategy requires students to10 Catalyst Chicago November 2006

stop talking and raise their hands when ateacher gives the order to “Give me five.”The strategy seemed “corny” at first tothe upper-grade teachers, Ostoichrecalls. But they agreed to try it—and itproved so effective that today Duganuses it to bring order to staff meetings.“We feel silly, but it works,” says 2ndgradeteacher Maeva Jankovich.Teachers also integrated charactereducation with the reading program. Studentsdiscuss values such as honesty andgenerosity that they encounter in literature.“You want discipline to come fromwithin, instead of from the outside,”Brooks explains. She also tells new teachersnot to yell at misbehaving studentsand to always let them know they arecared for. “Then they will listen to whatyou have to say,” she says.Teachers now have a book documentingeach student’s discipline infractions.Kids get one warning before being issueda “white slip.” Fourth- through 8thgraderswho rack up four white slips get adetention.In time, the school’s climate calmeddown, as kids and families realized misbehaviorwouldn’t be tolerated.“Younger brothers and sisters [who] sawthe older kids acting up also saw themgetting in trouble,” says science teacherWarren Fischer.“By the time I have them in 6th grade,some of them have come all the way frompreschool hearing the same rules overand over and over again,” says 6th-gradeteacher Laura Lukach. “You can ask themon the first day, ‘What are the five classroomrules?’ They all know them, andthey all know what they mean.”HIGH EXPECTATIONS, HIGH STANDARDSDugan knew he also needed to raiseteachers’ expectations and get them tobelieve that students could excel. To dothat, he brought research and case studiesof high-achieving low-income schoolsto professional development sessions forteachers to analyze and discuss.But he knew that expecting successwouldn’t do much good if the school wasn’tset up to achieve it. So Dugan also gotto work on instruction. In addition toreading, math, science and social studiesalso needed to improve. Parents complainedthat teachers assigned too littlehomework, while teachers insisted thatkids wouldn’t do it, Dugan recalls. Andthe bilingual program did not haveenough teachers.In his first year at Marsh, Dugan askedteachers to help select science and socialstudies textbooks that had English andSpanish editions. Dugan checked tomake sure that all subjects, and adequatehomework assignments, were includedin lesson plans. Over the next three years,Dugan added three bilingual teachingpositions. Classroom teachers got trainingin strategies for teaching second-languagelearners.In his eagerness to raise achievement,however, Dugan says he madeone big blunder: He identified a mathprogram with a strong research basethat he was certain would boost theschool’s math scores—but didn’t involveteachers in its selection.Uncomfortable with the new program,teachers attempted it half-heartedlyor reverted to the old, familiar one.Dugan pushed teachers to adopt the newprogram, but now says, “I was too forcefulin getting them to go along with it. Itdidn’t work.”From then on, teachers approvedevery program and textbook selection.The staff makes budget decisions together.And teachers at each grade level meetweekly for a common prep period to planlessons and share ideas and materials.Teachers say that Dugan’s high expectationsand openness to input have madethem more dedicated to their jobs andchanged the culture of the school. “Youdon’t feel like you’re just someone workingJASON REBLANDOPatricia Natseway (left) and Gilbert Garcia, parents of Marsh students, learn exercises to helptheir children at home with reading. Workshops like this boost parent involvement, which teacherssay is a major reason for the school’s academic progress.under him,” says librarian Diane Papage<strong>org</strong>e.“He treats you like, almost like anequal. He cares what your opinions are.”‘CAUGHT UP IN THE MOMENTUM’When 6th-grade teacher James Mullaneapplied to work at Marsh severalyears ago, he was a little taken aback by theprocess. When he arrived for the interview,he was asked to write an essay on the spot.His interview was held with a committeeof teachers as well as administrators.Marsh collects writing samples fromall of its applicants to make sure teacherscan communicate with parents. Newteachers are hired by consensus. Duganbelieves that teachers will feel moreinvested in helping colleagues succeed ifthey had a voice in selecting them.The collaborative effort results in anexceptionally dedicated and hardworkingstaff, says teacher Lukach. “You getcaught up in the momentum when youcome here. Everybody is doing something[extra]—committees, afterschoolprograms, sports programs, enrichmentclasses.”“You feel like your views matter and itreally is a team effort,” Mullane agrees.Jankovich, who recently became thefirst Marsh teacher to earn certificationfrom the National Board for ProfessionalTeaching Standards, is still early in hercareer but plans to stick around and seethe school’s upward climb continue.“It’s a place where I want to come,”she says. “I can’t imagine working anywhereelse.”•www.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong> November 2006 11

COVER STORY SUCCESS STORIESMcCorkle ElementaryProbation brings a big payoff‘A mess’ in the 1990s, probation got the school a new principalwho brought in intensive training and new staffBy Elizabeth DuffrinWhen Janet House becameprincipal of McCorkle Elementary,she faced the challengeof jump-starting aschool with rock-bottom test scores,uninspired teaching and high mobility.House was appointed to replace aprincipal who was ousted under the district’sfirst intervention initiative.“There was no real instructional programgoing on,” says Philip Hansen, whovisited McCorkle as director of intervention.“Everyone worked in isolation. Theupper grades were tumultuous in thehalls, in the classroom. It just was a mess.”(Hansen now works for Princeton Review.)Marvis Jackson-Ivy, a teacher at thetime, says no one was surprised by theouster of the old principal, given theschool’s history of failure. “We knew thatit was only a matter of time.”By moving quickly to inspire confidencein her leadership and setting high standardsfor teachers and instruction, Houseled the school toraise its test scoresMCCORKLE, 2005 by some 30 percentagepoints.ENROLLMENT 310AVG. CLASS SIZE* 22 Mobility, whichLOW-INCOME 94% soared to 43 percentin 1998, isBLACK 100%ITBS READING (since 1990)now at 27 percentRose from 7% to 39% (The district averageis 24 percent.)ISAT (ALL TESTS)**Rose from 23% to 40% As the surroundingRobert Taylor*Grades K, 1, 3, 6 and 8. Homes public**1998-99 was the firstyear the state administeredthe Illinois StandardsAchievement Test.Source: CPS, 2005 IllinoisState School Report Cardshousing projectwas being demolished,many familieswho had torelocate kepttheir children atMcCorkle. House says about half of studentsnow live outside the school’s attendancearea, some as far away as 112thStreet.“I like how my kids are being taught—they’re not struggling with anything” saysSerina Nolan, a mother of three whocommutes daily on two buses with herchildren to take them to McCorkle. “Theyget all the help they need.”‘LOW-HANGING FRUIT’House arrived with a resume thatseemed tailor-made for transforming theschool. She had worked for two yearsunder Patricia Harvey, then the district’swell-regarded chief accountability officer.She had been a teacher and teacherleaderat nearby Beethoven Elementaryunder the mentorship of Lula Ford, wholaid the groundwork for dramatic academicgains at that school.Given her experience and knowledgeof the neighborhood, House felt confidentwalking into McCorkle. Harvey toldher she could return to central office assoon as she’d taken care of the school.(Harvey later became the superintendentof St. Paul, Minn., Public Schools.)“I thought I could do this in a coupleof years,” House says with a smile.From the first staff meeting, Houseexhibited a warmth that calmed some ofthe staff’s anxieties about the transition,says preschool teacher’s assistant RillieLumpkin. And House found that her longtenure on State Street helped her to buildrapport with parents, including someparents who were confrontational withthe staff. “Many parents knew me frommy days at Beethoven. If they didn’t, relativesdid.”House began looking for what sherecalls Pat Harvey calling “low-hangingfruit”: a quick fix to inspire confidenceWHAT IT TOOKMcCorkle Principal Janet House had to deal with lowtest scores and high mobility when she came to theGrand Boulevard school in 1997. Here are a few of theways she was able to reverse both trends:• Look for a quick fix to inspire confidence inleadership• Don’t hesitate to encourage lackluster teachers tomove on• Focus on improving the weakest link in instructionand give teachers and parents someimmediate, tangible proof that your leadershipwill make a difference.So House got busy decorating toquickly improve the school’s environment.Drab hallways were hung with studentartwork, neatly framed. Pottedplants and small baskets of ivy suddenlyturned up in the corridors. She foundrugs for classroom reading corners and,with help from her building engineer,created a “poetry garden” in the centercourtyard with newly planted shrubs,lawn furniture and small pools.“My goal was to make McCorkle aplace where children would want tocome to learn and teachers would wantto come to teach,” she says.The next step was to improve disciplineand order. McCorkle did not adopta specific discipline strategy, but Housebegan insisting on higher standards ofbehavior for students.LAYING DOWN THE LAWYet the root of the discipline problems,she observed, was poor instruction.“Kids get in trouble when the classroomis not <strong>org</strong>anized, the teacher is not <strong>org</strong>anizedand [students] don’t have anythingproductive to do.”Like other principals in impoverishedcommunities, House found it difficult toattract good teachers, so she got to workto beef up the skills of the existing staff.Few had master’s degrees, so she encouragedthose who didn’t to return to school.She asked teachers to arrive an hour ear-12 Catalyst Chicago November 2006

ly, three to four days a week, for intensiveprofessional development.Jackson-Ivy, now the assistant principal,says House laid down the law aboutthe need to go above and beyond theminimum job requirements. “If you arenot ready to go back to school and get amaster’s degree or a [subject-specific]endorsement, you need to find anotherschool,” House told some of the oldguard. “If you’re not willing to come at7:30 a.m. for meetings and stay late, youneed to find another school.”As for hiring, “the pool of teachers hasnot been the greatest,” Jackson-Ivyacknowledges. Some candidates comefrom foreign countries and have poorEnglish-speaking ability. In Jackson-Ivy’sexperience, many career-changers havenot had adequate classroom training.While some prove to have natural talent,more often they flounder, she says.Now, House and Jackson-Ivy oftenconduct intensive interviews with 30 to40 candidates before hiring. “We’ll askthem, how do you teach reading comprehension?”Jackson-Ivy says. “We can discernby their answers if they don’t knowwhat they’re talking about.”Chante Asim, a 4th-grade teacher whopreviously taught in Los Angeles, saysother principals she interviewed withasked general questions such as “Whyshould I hire you?” But at McCorkle “theyasked about strategies, really focused oninstruction.”Others have been drawn by theschool’s climate. After attending a meetingat McCorkle, 1st-grade teacher ReneeThomas was so impressed with the schoolthat she made a beeline for the office torequest an interview. Eighth-grade teacherMargo Phillips-Thomas says when shearrived for an interview last year, shefound “big beautiful colors, plants in thehallway and flowers in front of the school.”Her previous elementary school spenta hefty sum on security guards, Phillips-Thomas says, but expected teachers topurchase their own classroom materials.McCorkle, by contrast, has one securityguard, excellent discipline and “classroommaterials galore.”Today, most of McCorkle’s teachersjoined the faculty within the last threeyears. In comparison to the district, ahigher percentage of teachers are considered“highly qualified” under No ChildLeft Behind guidelines.Yet turnover among the most talentedteachers remains an issue. The schoolrecently lost its three National Board-certifiedteachers: One enrolled in a principalpreparation program, anotherbecame a lead literacy teacher at a newlyopened Renaissance school and the thirdtook another teaching position.Kim Brasfield, a 2005 Golden AppleTeaching Award winner, also recentlyswitched schools. She cites family reasonsas well as the intense pressure tokeep raising test scores. Despite thatpressure, Brasfield admires House. “She’sdefinitely a strong leader,” Brasfield says.“You need to be in an environment likethat.”JASON REBLANDOD’Marris Smith reads a book from the library in Nicole Guillen’s 2nd-grade classroom atMcCorkle. Creating cozy, well-stocked reading corners is one strategy that helped raise readingscores at the school.BEYOND PENCIL-AND-PAPER TASKSTo improve curriculum, House quicklytargeted reading instruction. Based onher own teaching experience andMcCorkle’s test data, it was clear to Housethat students needed a stronger foundationin phonics. So she adopted the OpenCourt reading series, which provides aphonics base in the primary grades,along with literature and an emphasis onwriting.Reading specialists from ChicagoState University were recruited as theschool’s external partners (required atschools on probation), and House set upuniversity-run classes at the school soteachers could earn reading endorsements.House even modeled readingstrategies herself for staff.Overall, the goal was to help teacherslearn how to design complex and creativeassignments for students, not just penciland-papertasks.Now, even phonics is taught with flair.In Nicole Guillen’s 2nd-grade class,youngsters chant and act out lettersounds, bending over to mimic someonewith a backache to act out the sound “ow”and pretending to jump rope as theyread various letter combinations thathave a “j” sound.Other strategies Guillen uses include“reader’s theater,” in which children readstorybooks aloud like a script, taking onthe roles of characters and narrators. Inliterature circles, they divide into smallgroups to discuss books, with each studenttaking on an assigned task such asrecording unfamiliar words.“Ms. House really stresses that you haveto teach beyond the textbook,” Guillensays. “If we just stuck with one program,our scores would never go any higher.”Today, McCorkle awaits the latest testscore results to see if the school will makeit off probation. Yet House says she barelythinks about the label anymore—hersights are set higher.“The goal is to show that children onState Street can learn just as well as childrenanywhere else,” she says. “It’s nine yearsand I’m still chasing after that goal.” •www.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong> November 2006 13

ANDREW SKWISH

A place of extremesNeighborhoodsAUSTINCommunity activism and pride confront job, housing and public school challenges and anew wrinkle: a flood of ex-convicts—many of them parents—looking to reconnectBy Curtis LawrenceIt’s a place where small corner grocers servefamilies trying to make it on a tight income. It’salso where the city’s first Wal-Mart openedrecently, triggering a national debate about theneed for a living wage.It’s a place where patches of dirt lay before rundownapartment buildings. It’s also a place whereone can find block after block of neatly trimmedlawns. It’s a place where street corners give way to abustling drug trade. It’s also where the most activeblock clubs and community groups are found.All of these extremes are Austin, Chicago’slargest community area and a microcosm for thechallenges and promises of urban cities.“Austin ain’t no Mercedes Benz, but it ain’t noPinto either,” says U.S. Rep. Danny Davis (D-Chicago), who has lived in Austin for more than 25years. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s one of the mostdesirable communities in the city of Chicago.”Austin—about five miles west of downtown—used to be part of Cicero. The community of Europeanimmigrants underwent a massive growthspurt in the early 1900s after it had been annexedto Chicago. Between 1900 and 1930, the populationexploded from 4,000 to more than 130,000.By the 1960s, Italians were the dominant ethnicgroup. During the following decade, however, youcould almost hear the prophetic words sung bythe Temptations—“People moving out, peopleDID YOU KNOW THAT…• 84% of children living in Austin go to public schools• Poverty rates at two public schools in Austin are below the district average of 85%• 8th-graders at eight Austin elementary schools met reading standards in 2005For more statistics about the schools and residents in Austin, visit our website atwww.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong>.moving in. Why? Because of the color of theirskin”—playing in the background as 50,000 whitesmoved out and 60,000 blacks moved in.Today, Austin is one of the city’s more sociallyactivist communities, home to grassroots powerhouseBethel New Life, a major player in theaffordable housing movement. Recently, a battleover a new Wal-Mart superstore, which opened inSeptember just inside Austin’s boundaries onNorth Avenue, made national news when Ald.Emma Mitts (37th) made a crusade out of pressingfor more jobs despite labor unions’ calls for payingworkers a living wage.Small but potent groups have made a name forthemselves in Austin, too. Faith Inc. staked itsclaim in prisoner re-entry, an issue focused on theneeds of prisoners returning home. According to a2003 report by the Urban Institute, Austin is theleading community in Chicago where most prisonersreturn when they are released from prison.As Davis—and others whose eyes are trainedon prisoner reentry—says, most of those exoffendershave school-aged children who oftenhave been left with foster parents or grandparents.Navigating the public schools in Austin is challengingenough for families when both parents areat home. A recent flashpoint in the community isthe closure of Austin High School under ChicagoPublic Schools’ ambitious Renaissance 2010 initiative.<strong>This</strong> fall—while the number of studentsenrolled in the old school has dwindled to 255 seniors—theAustin Business and EntrepreneurshipAcademy moved in, the first of three smaller highschools planned for the site.LaShawn Ford, a candidate for state representativein the 8th District, has his own solution toAustin’s public education problems. He envisionstransforming the shuttered Brach’s candy factoryon Cicero Avenue, a symbol of lost industrial jobsin inner-city communities, into a high school. Sofar, CPS has been lukewarm about the idea.<strong>This</strong> is anoccasionalseriesexaminingschools froma communityperspective.Previousneighborhoodreports can befound online.•www.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong> November 2006 15

NEIGHBORHOODS AUSTINParent’s imprisonment tough on kidsAn estimated 1 in 10 children nationwide has a parent in thecriminal justice system. In Chicago, schools have no way to identifysuch children—and few resources to support them.<strong>This</strong> is the first report inan investigative series byCatalyst and The ChicagoReporter, both publishedby Community RenewalSociety, on the lives ofchildren whose parentsare or have been behindbars. The articles, in turn,will inform the work ofCivic Action, CommunityRenewal’s <strong>org</strong>anizing andadvocacy arm, to build abroad-based regionalcoalition to help thesechildren. Children’s nameshave been changed toprotect their privacy.By Curtis LawrenceIn summer school earlier this year,“James,” a 6th-grader at Howe Elementary,was having a run of baddays. He had enrolled at Howe acouple of years earlier and had someminor discipline problems, but soonbecame a star student.Then came an abrupt switch. “Hewas talking back and was disrespectfulto teachers,” says Sanya Gool,Howe’s social worker for the past sixyears. Even though she is responsiblefor nearly 700 students, Goolremembers James well.Later, Gool would learn fromJames’ grandfather and primaryguardian that the boy’s mother hadrecently returned to prison. “It gaveme some insight on why he was havingthese problems, and I was able toshare this with histeachers,” Gool says.Gool did not provideJames’ real name,to protect the juvenile’sidentity. But unfortunately,his family’supheaval is not unusualamong public schoolstudents in Austin—acommunity where asignificant chunk ofpeople who arereleased from prison goto get back on their feet.In 2005, 2,537 peopleleft prison undersupervision andreturned to zip codeareas that partially ortotally lie withinAustin. That’s about 13percent of the 19,167former prisoners whoreturned to communities in CookCounty last year, and about 8 percentof those released statewide.Even though the number of familiescoping with an incarcerated parentmay seem jarring, there are no targetedprograms in Chicago PublicSchools to help identify or supportstudents like James.“The status of a student’s parent isprivate information that we cannotrequire, therefore it’s difficult for usto determine whether a student’sparent is incarcerated,” says CPSspokeswoman Ana Vargas. A child inJames’ situation would be handledthe same as a child who neededintervention for any reason, such asa death in the family, she adds.Seven million children, or one in10 nationwide, have a parent behindbars, on probation or on parole,according to a 2005 report by SanFrancisco Children of IncarceratedParents Partnership, an advocacygroup for children whose parents arein prison.Last year, the <strong>org</strong>anization issueda bill of rights for children whoseparents are arrested or imprisonedthat asserts, among other things,their right to specially trained counselorsand other mentors.Nationwide, those helping exoffendersto reconnect to their communitieshave increasingly turnedtheir attention to children, who canhave problems with behavior, selfesteem and social adjustment as aresult of their primary caretakerbeing incarcerated. Much of thiswork has occurred on the East andWest coasts, but Chicago has becomeincreasingly involved, activists say.In Illinois, a task force for childrenof prisoners was formed in 2003, andafter hosting a conference two yearslater, it established a mission andgoals like increased training andsupport for caregivers as well associal educators, social workers andother mentors.Having a parent locked up inprison can be devastating for a child,particularly if it’s the mother, whomost often is the primary caretaker,says task force member Gail Smith,executive director of Chicago LegalAdvocacy for Incarcerated Mothers.Typically, women have shortersentences, “but it can have a hugeimpact on their child.” Smith says.“It’s hard [for them] to concentrate inschool. Most children grieve by gettingangry. A teacher may read that assomething else.”‘PROBABLY A LOT MORE THAN WE KNOW’Gool, James’ social worker, says ittook a couple of years for her to learnthat James’ behavior problems weretied to his mother’s imprisonment.She can only wonder how many otherchildren at Howe are dealing withsimilar issues.“There are probably a lot more thanwe know about, but there’s no way toidentify those students,” Gool says. “It’snot like we can send out a survey.”When James was having a roughtime back in 4th grade, he wasenrolled in an art therapy program atHowe that helped children deal withanger and build better social skills. Tohelp children confront bottled upemotions, a therapist working withstudents once a week might have studentsdraw super heroes who squeezeout anger. Or they might be assignedto work with a classmate on a jointproject to learn teamwork. The arttherapist was provided by a grant fromChicago Communities in Schools, agroup that connects public school studentsand their families with socialservices. James was in the program fortwo years. “Eventually, he became themodel student,” Gool says.Complications arising from a parent’sincarceration extend beyond a16 Catalyst Chicago November 2006

child’s emotional and behavior problems.A parent’s imprisonment canalso lead to logistical problems, likewhere a child can enroll in school,Smith says. A child whose parent is inprison often acquires a new addressbecause they have to move in with agrandparent or guardian. That canaffect school admissions, which formost public elementary schools istied to an attendance area. In someinstances, Smith says, guardianshave been falsely accused of “schoolshopping,” the practice of using falseaddresses to get a child into a desiredschool.Worse yet, Smith notes, areinstances when teachers and otherschool staff know that a child is dealingwith a parent’s incarceration butstigmatize rather than support them.“We have had situations where acaretaker has shared [informationabout a parent in prison] and reallyregretted it,” Smith says. “If somethingis missing, everybody looks atthat child first.”“We tell parents it can be helpfulto talk to a school social worker butto be careful because sometimes itcan backfire,” Smith explains.‘I HAVEN’T SEEN HER IN A LONG TIME’Howe Principal Vanessa Young, anAustin High School graduate, says itwould be easier to identify childrenlike James, whose mother recentlyreturned home, if the school had asecond social worker whose primaryresponsibility was to handle suchcases. “You tend not to come up toschool and blurt that out,” saysYoung, who does volunteer work withex-offenders at her West Side church.While some students like Jameshave the benefit of a social workersuch as Gool, others—for instance,“Jordan,” a 14-year-old 8th-graderwhose parents and two older brothersare behind bars—rely on grandparents.Jordan and his 13-year old brother,“Robert,” live with their maternalgrandmother, but they also spend alot of time with their father’s mother,Alice Jackson, who is executive directorof Mother’s House, a halfwayhouse in Austin for women who areContinued on page 22JOE GALLO“Derek,” a highschool freshman,is being raised bya great aunt. Hisfather has beenin and out ofprison for yearsand is now undercourt supervision.Imprisoned father a shadow on teen’s lifeIf you spotted “Derek” walking down thestreet in his Austin neighborhood, you’dprobably think he was a normal teenagerwith typical adolescent problems—homework,basketball and a little brother who sometimesgets on his nerves.And you’d be mostly right about the 15-year-old freshman, who has a smile that outweighshis slight frame.But there’s a catch. Derek is being raisedby a 59-year-old great aunt on his father’sside who has cared for him since he was 9. Hislittle brother was just a baby when the boysmoved from Minnesota back to Chicagowhere most of their family lives. Their mother’sfamily had major drug problems, accordingto Derek’s aunt.“My social worker said I couldn’t stay withmy mom or grandma anymore,” Derek says.While it’s unclear exactly why the boys’ motherwasn’t able to care for them, it is obvious whyDerek’s dad wasn’t available. He has served fivestints in prison on drug-related charges since1990, according to the Illinois Department ofCorrections, and he is now under court supervisionsince his release a year ago after servingclose to 12 months for narcotics possession.Derek sees his father occasionally, but hisaunt prefers to keep contact to a minimumbecause she suspects drug use and other dangerousactivities in the neighborhood where thefather lives.Derek has mixed feelings about his dad. Attimes, he seems resentful because “he’s nothelping us and nobody is trying to help us.”Then later, he will talk about missing his fatherand wanting to hang out with him.‘COMFORT ZONE’Meanwhile, Derek has other things on hismind, like trying out for his school’s basketballteam and doing homework for French andalgebra, one of his favorite classes. Back in elementaryschool, Latonya Brown was Derek’smath and language arts teacher. Citing confidentiality,she won’t discuss how Derek performedas a student, but notes that more andmore children in Chicago’s public schools haveparents who are incarcerated.These children will discuss with teacherstheir feelings about their parents being behindbars, “but you have to establish a comfort zonefirst,” Brown says.Derek’s aunt is supporting the boys on littlemore than $1,000 a month in disability paymentsshe receives for herself. She worriesabout both boys but tries to stay positive. “I’mconfident that [Derek’s] going to bring me adiploma from the 12th grade,” she says.Curtis Lawrencewww.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong> November 2006 17

NEIGHBORHOODS AUSTINNew beginning for Austin HighProgram anchored in entrepreneurship opens—the first of threenew small schools that will eventually replace the old high schoolBy Curtis LawrenceRev. Lewis Flowers walks down theechoing hallways of Austin HighSchool with such authority thatone could be f<strong>org</strong>iven for mistakinghim for a principal.On this Thursday afternoon, Flowers issporting a gray suit, black shirt and a purpleprint tie. He is on the fourth floormeeting with Deanna English, who, at thetime, was one of two real principals whooccupy the building. Austin Business andEntrepreneurship High School is one ofthe district’s new schools opened underRenaissance 2010, an aggressive plan toclose failing schools and replace themwith a mix of smaller schools.Eventually, two other new, but smallerhigh schools will share space in the samefacility and, after a three-year phase outthat ends next June with the last class ofgraduating seniors, the old Austin CommunityAcademy High School will ceaseto exist.Change at Austin, the yellow brickfortress on north Pine Avenue betweenFulton Boulevard and West End Avenue, isnothing new. Flowers has been along forthe high school’s rocky ride for more thana decade. Ten years ago, when he was amember of the local school council,Austin was in the crosshairs of the districtleadership’s school improvement sights,and was tagged to receive a “miracle”interim principal (Catalyst, October 1996).While there was some improvementin test scores under Principal ArthurSlater, progress was short of the miraclesome had hoped for. Since Slater left in2000, Austin had three principals. Thecurrent principal, Anthony Scott, tookthe post in January of 2004.Over the years, saving Austin hasbecome a crusade aimed at preserving aplace that, for much of the last century,was a West Side institution. Austin’s footballteams were feared, its academic programswere respected and its bands were asource of envy. Among music historians,Austin is known as the birthplace of Chicago-styleJazz. But white flight that began inthe 1970s gutted the neighborhood and itshigh school of diversity and resources thatmade both vibrant and successful.These days, Flowers is putting his hopein another effort to save Austin. Initially, hewas not in favor of CEO Arne Duncan’sdecision in 2004 to close Austin andreplace it with several smaller high schoolsin the same building. “I’m not going to saythe school wasn’t working,” Flowers says. “Ifeel that we were doing a damn good job.”He concedes that progress may not havebeen as fast as some would have liked, butnotes that it was progress nonetheless.But like others in the community,Flowers, CEO of the West Side MinistersCoalition, says he had little choice but toget on board with Renaissance 2010. Infact, he went a step further last year andteamed up with American QualitySchools, an educational management<strong>org</strong>anization that runs six local publicschools, to pitch the district on a highschool that would train students in businessand entrepreneurship skills. Theirproposal was approved last November.Since then, Flowers—who chairs theboard for Austin Business and Entrepreneurship—hasbeen making sure thenew contract school offers concreteopportunities for Austin’s youth andrestores confidence in public educationin the community. It’s a massive job, butFlowers says his focus is on the mostimport component—the students.Austin Business and Entrepreneurshipstarted fresh in September withabout 220 freshmen. The school willadmit approximately 200 students eachyear until it has full enrollment in the2009-2010 school year.Just outside the principal’s office,Flowers spots a despondent student sittingin a folding chair wearing blackpants and a maroon top, the school’s uniform.Flowers approaches her and, whispering,repeatedly asks her what’s wrong.After three tries, he gets a response: Thegirl says she may be suspended for cursingat one of her teachers.Flowers leaves. When he returns andshares the teacher’s side of the story, thegirl looks a bit sheepish. The teacher sayseven before the most recent incident, thegirl had not turned in assignments andkept her head down during classes. Flowersknew where the girl went to church andthreatened to report her to the pastor. Shepromised to mend her ways and Flowerswon her a reprieve from suspension.MORE THAN TOUGH LOVEFlowers knows it will take more thantough love and a new name to make Austinthe high school of choice rather than theschool of last resort. He reached out toMichael Bakalis, known for his tenure asstate superintendent of education and ashort-lived campaign for governor in 2002,to help develop the new school. Bakalis isnow president of American QualitySchools, which runs nine charter or contractschools in Chicago and Indiana,including Austin’s newest high school.One of Bakalis’ hires for Austin Businessand Entreprenuership was MalcolmCrawford, the director of the AustinAfrican-American Business NetworkingAssociation and owner of an art andhome décor store on Chicago Avenue.Crawford, who is now the school’sdirector of external relations, says he wantsstudents coming out of Austin to be readyfor college, but he also wants them to beable to write a business plan. Respondingto critics who claim the school is not academicallyfocused, Crawford says the firststudent <strong>org</strong>anizations to come togetherare honed on academics: student council,college-bound club and the honors club.Freshmen and sophomores will follow atraditional class schedule four days a weekwith 55-minute classes in English, languagearts, mathematics, social studies,reading and science. On Wednesdays, studentswill participate in business-relatedseminars, tutoring sessions and attendindependent study sessions. They also will18 Catalyst Chicago November 2006

e encouraged to join a club, among themone for students planning to attend college.But some observers aren’t yet sold onthe new school. “They don’t promote college,”says LaShawn Ford, the likely nextstate representative from the 8th District,who would like to see a high schoolinstalled at the site of the shutteredBrach’s candy factory on Cicero Avenue.“They promote these kids getting a businessafter high school.”Bakalis says that while he hopes thenew school will eventually result in morehomegrown businesses in Austin, theschool is not encouraging students tomake the leap immediately after graduation.Instead of steering Austin studentsaway from academics, they say they arepromoting innovative options.REFORM IS MESSYThere are signs, though, that a new eraof reform at Austin won’t be easy. Just weeksinto the school year, English was shifted toanother position and a new principal withexperience in middle school, Stefan Fisher,was brought in. Early expectations werenot being met and a leadership change wasnecessary, says Flowers. English is comfortablewith the change, he says.The idea for a small school centeredon business has been around for a while.A previous principal, Learna Brewer-Baker,tapped Bakalis for a potential partnershipand then successfully applied for aplanning grant from the Chicago HighSchool Redesign Initiative, which wascharged with dispensing funds to helplarge high schools improve by convertinginto several smaller schools. The overalleffort was bankrolled by a $12 milliongrant from the Bill & Melinda GatesFoundation and additional contributionsfrom several local foundations.But before the effort could get off theground, Brewer-Baker was removed amidconcerns about school security and discipline.(Catalyst, October 2003.) Not longafter, talk of a districtwide new schoolplan began to surface and the smallschools grant was put on hold.The sudden turn of events was anotherdisappointment for Austin, and Flowersfelt the best move would be keepingthe small-schools plan on life support byapplying to reopen under Renaissance2010. “You either get on board with [CPS]or you lose out,” Flowers says.Several others, including members ofthe Austin Transition Advisory Council,the group established to weigh options fornew programs at Austin, felt the same way.After reviewing the final round ofapplicants of schools that would openthis fall, advisory council membersdecided that none of the three applicationswere ready to fly. The other twoapplications were Austin Polytechnic, aJOHN BOOZHome-basedbusiness owner VeraNorris talks tofreshmen at AustinBusiness andEntrepreneurshipHigh School abouttoxic chemicals incommon householdcleaning products.Once a week, theschool offersbusiness-relatedtalks and seminars.program to train students for manufacturingcareers, and a math and scienceacademy run by Concept Schools.In the end, Schools CEO Arne Duncandecided not follow the advisory council’sadvice, and recommended that theSchool Board approve Austin Businessand Entrepreneurship.“We’re not going to wait forever toreopen these schools,” says JeanneNowaczewski, director of New SchoolsDevelopment. “Arne Duncan and theoffice of New Schools Development listenedto the [advisory council] for theentire six months that this was going on.”Duncan’s decision did not exactly godown smoothly.Advisory council members “harboredresentment, but they felt that they had tobe on board and be a good sport,” saysKhalid Johnson, who was not on the advisorycouncil for the first round, but wasclose to the process. <strong>This</strong> year, he is amember of the advisory council for thesecond round of school selections.Two proposals are currently underconsideration for a second school. One isfor Austin Legal Studies and Criminal JusticeAcademy, another contract schoolthat would be run by American QualitySchools in partnership with the West SideMinisters Coalition. The other is AustinPolytechnical Academy, which was alsounder consideration in the first round. •www.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong> November 2006 19

UpdatesPeer evaluation makes debutEight schools run by the teachers union are the first to try a newmethod of rating probationary teachersBy Lorraine ForteAfter years of being stuck in neutralin Chicago, the notion that teachersknow best how to evaluate andtrain other teachers is finally takinga toehold in the district.<strong>This</strong> fall, the teachers union and thedistrict are piloting a peer mentoring andevaluation program at eight union-runpublic schools, dubbed “Fresh Start”schools. The 125 new teachers at theseschools will take part this year, buttenured teachers who have been given“unsatisfactory” performance ratings willbe required to participate next year.“When we negotiated the Fresh Startagreement, one of the things we wantedwas to make schools more viable,” saysMarc Wigler, who oversees Fresh Start forthe Chicago Teachers Union. “<strong>This</strong> issomething we felt was important toenhance teacher retention and supportteachers in their careers.”The concept of peer evaluation firstsurfaced in 1993, when a new teachers’contract called for a joint union-CPScommittee to explore ways to improveevaluation, including peer review. Thecommittee went nowhere, and the nextcontract made no mention of any suchcommittee. The current contract, negotiatedin 2003 under the leadership of formerCTU President Deborah Lynch,picked up the concept again, but the ideanever moved forward. Lynch later lost aheated union election to current PresidentMarilyn Stewart.The new pilot, however, may becomea political football in the upcoming unionelection, expected to be a rematchbetween Lynch and Stewart.NEW RATINGS, BETTER TEACHERSThe pilot teacher evaluation programincludes a new rubric intended to giveteachers a clearer picture of their strengthsand weaknesses in the classroom.The rubric includes 22 skills dividedamong four categories: Teaching procedures,classroom management, contentknowledge and personal characteristicsand professional responsibility, such aslevel of interest in teaching and cooperationwith parents and other school staff.The current evaluation, for both newand tenured teachers, is less focused onteaching skills and knowledge andincludes a number of non-instructionalcriteria such as how students walk downhallways, says Wigler. “Why is a teacherbeing evaluated on how their bulletinboards look?” he says. “That doesn’t getto the heart of instruction.”Veteran mentors will rate new teacherson a scale of 1 (the lowest) to 3 in eachskill. Eight mentors will be full-timecoaches who observe each newcomerbefore evaluating him or her. They willwork a longer school day, receive a 20percent salary boost plus a $5,000 bonus.Based on the evaluations, a ninemembercommittee of union and districtofficials, CEO Arne Duncan and CTUpresident Stewart among them, willmake the final decision on whether toretain teachers who get low ratings in thepilot program. Principals have sole hiringand firing authority under the traditionalevaluation program.Adam Urbanski, president of theRochester, New York Federation of Teachersand an expert on peer evaluation, sayssuch programs have spread to “the morePILOT SCHOOLSSchools participating in the new evaluation program are:• Attucks• Hamline• Bass• Piccolo• Burke• Richards High• Chalmers• Wells Highprogressive” districts across the countrysince being pioneered in Toledo, Ohio inthe 1980s. “The fears that such a programwill be divisive and turn teacher againstteacher, or that it won’t improve the qualityof teachers, have turned out to beunfounded,” Urbanski says.A POLITICAL FOOTBALLMembers of Pro-Active ChicagoTeachers (PACT), the opposition caucusthat is expected to slate Lynch as its presidentialcandidate next spring, soundedthe alarm over an initial plan by CPS andthe union to change state law to accommodatethe pilot. Under the IllinoisSchool Code, only those who have a Type75 administrative certificate, which allprincipals are required to have, can evaluateteachers. Now, the district and theunion are planning to obtain a waiverfrom the Illinois State Board of Education.PACT maintains that the pilot, which issanctioned in the union contract as part ofan amendment related to the Fresh Startprogram, should be voted on by members.“When we had changes to the contract,we didn’t move forward without going tothe House of Delegates,” notes Lynch, whoadds that the current union leadership initiallyvoted against Fresh Start’s precursor,the partnership schools initiative.Wigler counters that the pilot is partof an existing contract agreement and“is not something that needs memberratification.”To contact Lorraine Forte, call (312) 673-3881 orsend an e-mail to forte@<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong>.20 Catalyst Chicago November 2006

Task force to count, reclaim dropoutsActivists, legislators also seek more funding and accountabilityBy Sarah KarpWhen Gov. Rod Blagojevichsigned a law to raise the age thatteenagers can legally leaveschool, it was the first steptoward tackling the high school dropoutrate. Step two, advocates say, is nailingdown how many teenagers are out ofschool now and then getting them tocome back.Last month, Blagojevich announcedthat State Board of Education ChairmanJesse Ruiz would head a new task forcethat focuses on re-enrolling dropouts.Other members of the task force—theresult of a House Resolution passed in thespring—are legislators, Schools CEOArnie Duncan and dropout preventionand recovery advocates like Jack Wuest.Wuest’s advocacy <strong>org</strong>anization, theAlternative Schools Network, has beenpushing the state to look at these issuesfor years.“We want people to see theseteenagers as students, not as dead-enddropouts,” Wuest says. Once people lookat these young people as students, theywill start to see the possibility that theywill re-enroll, he says.Over the next two years, the task forcewill look at a combination of issues. Atthe top of the list is determining the actualnumber of dropouts in school districtsthroughout Illinois.Currently, the Illinois State Board ofEducation calls for districts to count asdropouts any student who is not currentlyon the roster with the exception ofthose who transferred to another school,died or are absent due to a prolonged illness.Critics say this measure is faultybecause it is only a one-year rate and disregardsthose who transfer to alternativeschools but never wind up graduating.The report that the task force is compilingwill make use of data from the U.S.Census American Community Surveyand will show, over a period of time, howmany dropouts are in a particular town.The task force also will look ataccountability and funding for programsthat serve dropouts.Wuest says he would like the task forceto recommend that some funding be setaside for programs to help recapture studentswho have dropped out but want toreturn. Often, teenagers who drop out arenot going to return to their old highschools because whatever problems theyhad there still exist, he explains. “But ifthey see other options, they might comeback,” he says.There is already demand for more alternativehigh school programs, which existfor students who have previously droppedout or had discipline problems in traditionalhigh schools. Currently, all of Chicago’salternative high schools are operatingat capacity and have waiting lists.DROPOUT HEARINGS ACROSS THE STATE<strong>This</strong> month, the task force will releasedropout data for districts statewide, andthen hold hearings to determine whetherthe data is accurate and complete. Wuestnotes that a hearing may not be necessaryin Chicago because a comprehensivereport on CPS dropouts was producedby the Consortium on ChicagoSchool Research last year.That report revealed a 16 percentagepointgap between the district’s officialgraduation rate (70 percent) and theactual percentage of high school studentswho graduate in a four-year period(54 percent). The district figure ishigher than the Consortium’s because alarge number of students are counted astransfers—including those who go toalternative schools within the system—but never tracked to determine whetherthey eventually graduate. The Consortium,however, used individual studentrecords to track who graduated, whetherthey change schools or not.Statewide, the dropout rate declinedsignificantly over the past year, with 5,000fewer students leaving high school comparedto the previous year.However, some question whether thelower dropout rate means that moreteenagers are staying in school. In 2004,Illinois changed the legal dropout agefrom 16 to 17. Since then, 16-year-oldswho don’t come to school are counted aschronic truants, not dropouts, says PatriciaVesper, attendance director for RooseveltHigh School.To really tackle the dropout problem,Vesper says she needs truant officers totrack down students who stop showingup for school immediately. The districteliminated truant officers about a decadeago. The responsibility for keeping afterabsent students falls to high school attendanceoffices, which have limited staffand funding.Another challenge that complicatesdropout recovery efforts is the federalNo Child Left Behind law, says SheilaVenson, director of Youth ConnectionsCharter, which runs 23 programs inChicago. Accountability provisions inthe law now require that at least 50 percentof students perform at grade levelin reading and math.“We want people to see these teenagers as students,not as dead-end dropouts.”Jack Wuest, Alternative Schools NetworkBut most students in alternativeschools dropped out because they werestruggling academically, notes Venson,who estimates at least 65 percent of YouthConnections Charter students are readingbelow 7th-grade level. In 2005, only19 percent of the charter school’s studentspassed Prairie State exams.“There should be different standardsof accountability,” she says.To contact Sarah Karp, call (312) 673-3882 or e-mailkarp@<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong>.www.<strong>catalyst</strong>-<strong>chicago</strong>.<strong>org</strong> November 2006 21