At Arm's Length: (Taking a Good Hard Look at) Artists' Video

At Arm's Length: (Taking a Good Hard Look at) Artists' Video

At Arm's Length: (Taking a Good Hard Look at) Artists' Video

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

PREFACEWhen my mom wanted to get a good look <strong>at</strong> me as a kid she'd take me by bothshoulders and hold me <strong>at</strong> arm's length. Most of the time I averted my eyes not entirely sureI'd we<strong>at</strong>her her scrutiny. Usually I squirmed, got defensive, felt misunderstood.Th<strong>at</strong>'s basically wh<strong>at</strong> I had in mind for AT ARM'S LENGTH. It was an <strong>at</strong>tempt toappraise video art, to understand how it fit into the bigger picture of culture and politicaleconomy. These essays could have been called trying-to-situ<strong>at</strong>e-video-art-in-the-realworld.Because even if art isn't supposed to fit into our day to day life, I'd still be troubled by itscontemporary irrelevance. Art can be powerful, much more powerful than it is

today, and as a society we badly need the spirit of empowerment and pluralism th<strong>at</strong>underlies video art. Th<strong>at</strong> spirit should reach more people.Reaching people—the audience question—is a big problem for video. Years ago Iasked an artist how he thought about his audience. "I don't", he answered. The implic<strong>at</strong>ionwas th<strong>at</strong> thinking about who you were talking to and whether they would understand orcare wh<strong>at</strong> you were saying was somehow out of keeping with being an "artist". Concernwith audience was equivalent to commercialism. This tacit formula struck me as colossallystupid. First because it perpetu<strong>at</strong>ed the century-old chasm between the public and the avantgarde, and second, because it reflected an embaressingly simplistic analysis of capitalism.Don't get me wrong, I'm not suggesting we produce video art for "mass audiences"(whoever they are), but solipsistic art-making is isol<strong>at</strong>ing—destructively so-as video art'strail-blazing twenty-five year history illustr<strong>at</strong>es.Complementing producers' unwillingness to deal with audiences' needs werecur<strong>at</strong>ors' and critics' reluctance to strike freely and mercilessly. Dale Hoyt sums up thesitu<strong>at</strong>ion in AT ARM'S LENGTH's opening epigram: "Criticism in the video art world is alove letter disguised as discourse."I wanted to poke a hole in this self-sufficient bubble. I looked for writers outside thevideo community, critics th<strong>at</strong> had nothing to lose, nothing to gain, no loyalties to negoti<strong>at</strong>e.I brought together a screenwriter, a specialist on intern<strong>at</strong>ional media and politics, a tvcritic/producer, and a video artist. Two of them were barely acquainted with video butpotentially symp<strong>at</strong>hetic. A third, John Wyver, was still an outsider although somewh<strong>at</strong>more familiar with the work. The final contributor was an exception to my rule.

Jon Burris is a video artist and administr<strong>at</strong>or. Given his extensive knowledge and interest inpublic funding, I asked Jon to write on the economics of video art. The other contributorswere asked to write about individual tapes in light of broad them<strong>at</strong>ic areas. I hoped wewould get some fresh perspectives, and even encourage a new group of critics to write aboutvideo.The very idea of going to "outsiders" suggests the prejudice th<strong>at</strong> most deeply affectsthis project. <strong>Video</strong> art should be able to be understood and appreci<strong>at</strong>ed without extensiveinculc<strong>at</strong>ion into video aesthetics and technology. My notion of audience requires onlyopenness and intelligence from a viewer. When my new-to-the-field writers worried th<strong>at</strong>they couldn't write about the work since they weren't experts, I argued th<strong>at</strong> video shouldn'trequire expertise. So these critics dove in and began learning, sifting, and thinking. By theend of the process, they were well-versed if not expert. Their responses are informed, butwritten from the gut. As such, they risk being provoc<strong>at</strong>ive. Hoorah.As a means to getting penetr<strong>at</strong>ing criticism, the "outsiders" str<strong>at</strong>egy was not a totalsuccess. Contributors' lack of commitment and understanding of the field was responsiblefor the de<strong>at</strong>h of more than one of these essays. I'm immensely disappointed th<strong>at</strong> there is nodiscussion here of video's rel<strong>at</strong>ionship to other contemporary visual art-making, or of videoand its rel<strong>at</strong>ion to technology. Additional tangents could have been developed th<strong>at</strong> weren ' t.Despite these regrets, I'm confident th<strong>at</strong> the essays will be useful to artists andaudiences eager to get beyond the assumptions of twenty years ago. The ideas clash andconflict-there is no unified thesis—but each of the essays in its own way nudges us

forward into the future. In John Wyver's essay, he muses on the st<strong>at</strong>e of the post-networktelevision hegemony and asks the question: If tv is no longer just the omnipotent mindfuckerand consumer delivery truck th<strong>at</strong> social critics said it was, wh<strong>at</strong> will happen tovideo art's identity? Leslie Fuller adds to the fracas, calling artists into the trenches ofTinseltown to make better television. John Downing tries to define a political aesthetic forU.S. video in the 90s. Downing's preference for the uninterpreted "voice"—selfarticul<strong>at</strong>ion structured in rel<strong>at</strong>ively conventional forms—may strike some readers as naiveor retrogressive. But form and audience-building are political questions, and the dilemmapoints back to Downing's first question: Wh<strong>at</strong> is politics? The final essay by Jon Burrisevalu<strong>at</strong>es the influence of the p<strong>at</strong>ron on the art—the p<strong>at</strong>ron in this case being publicfunding agencies. <strong>Video</strong>, as an "infant" art form raised in the "family" of public fundingwas uniquely affected by th<strong>at</strong> early development.Burris' discussion hints <strong>at</strong> unsettling questions. He reminds us th<strong>at</strong> the term"underground" film was replaced with "independent" <strong>at</strong> the onset of government funding.Did early public money remove the incentive to build links to new audiences in otherdisciplines or political communities, or to loc<strong>at</strong>e altern<strong>at</strong>ive financial sources, therebystamping out some of video's political potential? Could the perverse truth be th<strong>at</strong>sometimes st<strong>at</strong>e funding lessens video's vitality and relevance—even insures its marginalst<strong>at</strong>us? By influencing the way in which we present our messages, the government castsour rel<strong>at</strong>ionship to mainstream culture and politics.*Unfortun<strong>at</strong>ely, the crisis <strong>at</strong> the N<strong>at</strong>ional Endowment for the Arts has caused a newconsolid<strong>at</strong>ion of arts support within the arts community th<strong>at</strong> discourages us fromconsidering these issues. As we fight for the survival of the agency, we should not ignorewh<strong>at</strong> public funding has done for us and to us. There are no absolutes here: st<strong>at</strong>e funding• St<strong>at</strong>e funding has had other—perhaps leas fundamental, but nevertheless significant—impact on this project NYSCA's separ<strong>at</strong>ion ofvideo and film for instance, led to the essays dealing with issues only as they were relevant to video. Ultim<strong>at</strong>ely I made a single exception allowing JohnDowning to discuss an exceptional film an environmental issues.AT ARM'S LENGTH also suffers from wh<strong>at</strong> I've come to call "the public funding time warp". Conceptualiz<strong>at</strong>ion of this projectoccurred so long ago th<strong>at</strong> I no longer certain how well it addresses current problems in the video community. My life has moved on--as hasvideo. -

is neither entirely good or bad. But it's worth paying <strong>at</strong>tention to. As a condition of therelease of this year's grant award, the NEA asked The Kitchen to present an advance list oftapes for this exhibition and all other video exhibitions this season. No list. No dough. AndNEA surveillance of Kitchen activities continues. As the government reevalu<strong>at</strong>es itscommitment to free expression perhaps the arts community should reconsider wh<strong>at</strong> thegovernment's money is worth. Fighting for an unfettered grants process, the ostensibleprocedure of yesteryear, seems almost too good to be true in light of recent intervention.But the real danger is th<strong>at</strong> the present st<strong>at</strong>e of siege will obscure the actual impact offunding under even the best of conditions. -AcknowledgmentsMy gre<strong>at</strong>est thanks go to Jon Burris, John Downing, John Wyver, and Leslie Fullerfor their insight, tenacity, p<strong>at</strong>ience and'goodwill. Amy Sl<strong>at</strong>on worked doggedly on aninvestig<strong>at</strong>ion of technology th<strong>at</strong> was elusive and ultim<strong>at</strong>ely unfruitful. Others have been ofcritical assistance along the way. For editorial advice, Kevin Osborn, P<strong>at</strong> Anderson, Dai SilKim-Gibson, and Sarah Hornbacher were enormously generous. Mike Mills artfullydesigned the book on a penurious budget. Alliance Capital Management, LP came throughwith printing in our hour of need. Dale Hoyt was an enthusiastic and helpful Kitchenliaison. NYSCA staff took a risk and the agency's hand was bitten. Joe Beirne deservesthanks for his relentless assaults on the shibboleths I too readily embrace. And finally, JohnDrimmer for his kindness and confidence which often seemed to exceed the limits of goodsense.Barbara OsbornNew York City, 1990

CriticismIn the video art worldis a love letterdisguised asdiscourse.Dale Hoyt

COMING TO TERMS WITH THEFRIGHTFUL PARENT:VIDEO ART AND TELEVISIONJOHN WYVERFor much of its brief history, video art has been searching for its reason for being. Assoon as it emerged in the 1960s from the coupling of newly available technology with theNew York art world, video art sought legitim<strong>at</strong>ion. Such legitim<strong>at</strong>ion was essential for artistsseeking funders, for cur<strong>at</strong>ors seeking audiences, and for critics seeking meaning. And forthe most part this legitim<strong>at</strong>ion has been provided in the terms of either the museum or themedium th<strong>at</strong> David Antin dubbed "video's frightful parent": television (Antin 1986: 149).The museum has offered (albeit often grudgingly) an embrace in part <strong>at</strong> leastbecause video art has been seen as extending the concerns of wh<strong>at</strong> Martha Rosler hasidentified - as "old-fashioned Formalist Modernism" (Rosier 1986: 250). No such embrace,1

however has been proffered either by or towards television, and the rel<strong>at</strong>ionship hasinvariably been one of opposition. Especially for artists in the United St<strong>at</strong>es, television hasoffered a target for <strong>at</strong>tack, critique, pastiche, appropri<strong>at</strong>ion and subversion, as well as(occasionally) envy. And for critics television has been the object against which video can bedefined and defended. (It should be noted th<strong>at</strong> these remarks are prompted by the history ofvideo art in the United St<strong>at</strong>es. Broadcast television has been less central, though stillsignificant, to artists' video outside the USA, in part <strong>at</strong> least because the mainstreammedium has exhibited far gre<strong>at</strong>er variety in Europe and elsewhere.)The inadequacies of the formalist legitim<strong>at</strong>ion has been considered elsewhere,notably by Rosier in her important essay, "Shedding the Utopian Moment" (Rosier: 250).This essay concerns the origins and the problems of video's legitim<strong>at</strong>ion against television.There is no doubt th<strong>at</strong> the essential opposition between video and television has been centralboth to the preoccup<strong>at</strong>ion and achievements of many artists working with video and to muchof the discussion about video art. But my concern is to argue th<strong>at</strong> this idea was, as itremains, grounded in a narrow and limited critique of television; th<strong>at</strong> it has contributedconsiderably to the video art world's far from fruitful hermeticism; and (perhaps mostimportantly) th<strong>at</strong> it could prevent artists from recognizing contemporary changes withintelevision and the possibilities th<strong>at</strong> these may open up.Th<strong>at</strong> television has been profoundly important in shaping the development of videoart is accepted by most comment<strong>at</strong>ors on the medium. As the myths th<strong>at</strong> pass as historyhave it, television and artists' video were entangled from the earliest emergence of theyounger form. Most historical surveys of video art begin with the exhibitions by Wolf2

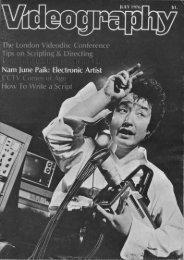

Vostell (in Cologne in 1959, remounted in New York in 1963) and Nam June Paik(Wuppertal, 1963 and New York, 1965) which incorpor<strong>at</strong>ed television sets into artworks.These artists' fascin<strong>at</strong>ion with television and their simultaneous rejection of it (Paikdistorted the images; Vostell broke, daubed with paint and even shot <strong>at</strong> the sets) were soon tobecome familiar concerns for many cre<strong>at</strong>ors.As video art has developed, many writers, including numerous artists, haveaccepted and asserted video's essential opposition to television. For some, this is an article offaith, as it was for the artist and critic Douglas Davis back in 1970: "The gre<strong>at</strong>est honor wecan pay television is to reject it" (Davis 1978: 33). Others are equally emph<strong>at</strong>ic, if a littleless blunt. In a recent study of artists' video, the Dutch critic Rob Perree st<strong>at</strong>es, "There is afundamental incomp<strong>at</strong>ibility of interests and principles between the artist and the televisionmaker" (Perree 1988: 53). And the cur<strong>at</strong>or K<strong>at</strong>hy Huffman writes in 1984, "<strong>Video</strong> art isfundamentally different from broadcast television and has been since its inception. Wherebroadcast television addresses a mass audience, video art is intensely personal—areflection of individual passions and consciousness" (Huffman: 1984).These comment<strong>at</strong>ors, along with many others, speak of television as if it were amedium defined by a single essence. They fail to recognize th<strong>at</strong> their remarks draw on onlyone conception of the medium. This conception, unsurprisingly, is derived fromunderstandings of the model of commercial network television in the United St<strong>at</strong>es in the1960s and 1970s, and from the particular intellectual clim<strong>at</strong>e of the time, which wasbroadly antagonistic to popular culture.3

It hardly needs st<strong>at</strong>ing—except th<strong>at</strong> it is often forgotten—th<strong>at</strong> the model of U.S.commercial network television is neither the sole nor the inevitable form of the medium.The neg<strong>at</strong>ive and hostile <strong>at</strong>titudes toward television still held by many artists and criticstoday ( and of course by many others ) perhaps fail to take sufficient account of theextraordinary potential of television, and of the ways in which audiences use television intheir lives, in their imagin<strong>at</strong>ions, in their fantasies. Seen in a context broader thancommercial broadcasting in the United St<strong>at</strong>es, television is not nearly as homogeneous asthe dominant conception assumes. Nor are audiences as undifferenti<strong>at</strong>ed and as passive as themainstream intellectual approach holds them to be.Consider two videotapes made in the 1970s which take television as their subject:Television Delivers People (1973) by Richard Serra and Carlota Faye Schoolman and the AntFarm collective's Media Burn (1975). Both tapes still fe<strong>at</strong>ure prominently in exhibitionsand anthologies, and both are frequently discussed and referred to in writings about video.The central, spectacular images of the l<strong>at</strong>ter—a customized Cadillac crashing through a wallof blazing television sets—is also often reproduced in books and articles, as well as onpostcards.Television Delivers People simply scrolls a text of discrete sentences up the screenwhile Muzak plays on the soundtrack. The sentences offer a strident critique of the oper<strong>at</strong>ionsof television: "The product of television, commercial television, is the audience." "You arethe product of tv." "Commercial television defines the world so as not to thre<strong>at</strong>en the st<strong>at</strong>usquo." "You are the controlled product of news programming" (Schneider and Korot 1976:114). The tape lasts six minutes.4

Media Burn is more than twice as long as Television Delivers People, andconsiderably more fun. The tape records the prepar<strong>at</strong>ions for the collision of car andtelevision, the maintream media interest th<strong>at</strong> the event gener<strong>at</strong>ed, and the carnival<strong>at</strong>mosphere of the day. But the appearance of a John Kennedy lookalike introduces anelement th<strong>at</strong> is just as didactic as Television Delivers People. "Kennedy" delivers a spoofIndependence Day address: "Mass media monopolies control people by their control ofinform<strong>at</strong>ion...Who can deny th<strong>at</strong> we are a n<strong>at</strong>ion addicted to television and the constant flowof media? Now I ask you, my fellow Americans, haven't you ever wanted to put your footthrough your television screen?" (Schneider and Korot 1976: 11). And this, of course, is thedesire acted out on a mythic level in the crash th<strong>at</strong> follows.Each tape flaunts its oppositional <strong>at</strong>titude to televsion, both in the texts quoted andin the form employed. The deadpan present<strong>at</strong>ion of a text in Television Delivers Peopleasserts itself against the glossy visuals of commercial broadcasting, just as the rough, videoverite of Media Burn is intended to contrast with the far more controlled and "professional"look of mainstream news and documentary production.Both tapes were framed by, and contributed to, the intellectual discourse abouttelevision in the United St<strong>at</strong>es. This discourse in turn was shaped in the 1960s in a clim<strong>at</strong>eantagonistic to popular culture in general, and to television specifically. For while fineartists like Warhol and Lichtenstein may have embraced television in their work, theoverwhelming majority of intellectuals in the United St<strong>at</strong>es vehemently rejected it. In hisenlightening collection of essays No Respect—Intellectuals and Popular Culture, AndrewRoss argues convincingly th<strong>at</strong>, by the beginining of the 1960s, for many writers and critics5

"...television had become the l<strong>at</strong>est unredeemable object in the continuing deb<strong>at</strong>e aboutmass culture" (Ross 1989: 104-105).In the post war world, the thinking of Frankfurt School intellectuals TheodorAdorno and Max Horkheimer (both of whom spent the 1940s in the St<strong>at</strong>es) was particularlyinfluential in framing for many American intellectuals their view of mass culture. Theirideas "reflected the breakdown of modem German society into fascism" comments DavidMorley, "a breakdown which was <strong>at</strong>tributed, in part, to the loosening of traditional ties andstructures and seen as leaving people <strong>at</strong>omized and exposed to external influences andespecially to the pressure of the mass propaganda of powerful leaders, the most effectiveagency of which was the mass media. This "pessimistic mass society thesis" stressed theconserv<strong>at</strong>ive and reconcili<strong>at</strong>ory role of "mass culture" for the audience (Morley 1980: 1).The polemical <strong>at</strong>tacks of Adorno and Horkheimer on the barbarian influences of the"culture industry" propag<strong>at</strong>ed the view th<strong>at</strong> popular forms like the cinema and televisionwere, in Ross' words, "profitable opi<strong>at</strong>es(s), synthetically prepared for consumption for asociety of autom<strong>at</strong>ons" (Ross 1989: 50).Commercial television as it had evolved since 1945 appeared to many to be theembodiment of such an idea. And the quiz show scandals of 1959, in which contestantsadmitted th<strong>at</strong> they had been prompted to che<strong>at</strong> by the program producers, reinforced for manycritics the sense of the medium , as not only banal and absurd, but also deceptive and grosslymanipul<strong>at</strong>ive. Ross quotes Gilbert Seldes asserting th<strong>at</strong>, "next to the H Bomb, no force onearth is as dangerous as television"(Ross 1989: 105). And the view of television held by thesocial, cultural and intellectual elite of Camelot was expressed by President6

Kennedy's Federal Communic<strong>at</strong>ions Commission chairman Newton Minow in his celebr<strong>at</strong>ed1961 speech <strong>at</strong>tacking television as a "vast wasteland". The high-culture echo of T.S. Eliotwas presumably appreci<strong>at</strong>ed by those concerned to preserve the cultural values of an earliertime.Following Adorno et al, w<strong>at</strong>ching television in the 1960s was seen as the simple,passive consumption of "messages". A parallel strand of modernist thought lamented theunrealized potential of the mass media which, under capitalism, was a one-way process oftransmission from the center band reception by the mass. One of the texts extensivelyquoted in critical essays about video art was Bertolt Brecht's short note, "The Radio as anAppar<strong>at</strong>us for Communic<strong>at</strong>ion". Brecht had originally published this in 1932, but it onlybecame available in English in a collection edited by John Willett in 1964....(Q)uite apart from the dubiousness of its functions, radio is onesidedwhen it should be two-... It is purely an appar<strong>at</strong>us fordistribution, for sharing out. So here is a positive suggestion:change this appar<strong>at</strong>us over from distribution tocommunic<strong>at</strong>ion...the radio should step out of the supply businessand organize its listeners as suppliers (included in Hanhardt 1986:53).John Hanhardt, writing in 1984, sees television in terms exactly paralllel withBrecht's sense of radio: "(Television) was not the communic<strong>at</strong>ions medium it claimed to7

He proposed th<strong>at</strong> the promises inherent in communic<strong>at</strong>iontechnology—particip<strong>at</strong>ion, decentraliz<strong>at</strong>ion, mobiliz<strong>at</strong>ion,educ<strong>at</strong>ion—ought to be more fully realized. Every receiver is alsoa transmitter! Enzensberger's slogan spoke directly to ways oftransforming the means of production (it had less to say about theactual conditions of consumption), and it was a direct injunction tothe New Left to abandon its technophobic allegiances to preindustrialforms of communic<strong>at</strong>ion, and to make "proper str<strong>at</strong>egicuse of the most advanced media"(Ross 1989: 121).Such brief quot<strong>at</strong>ions from, and summaries of, these important texts almostinevitably misrepresent their subtle arguments. But the writings are now familiar (perhapsoverfamiliar) cornerstones of the understanding of television and video in the UnitedSt<strong>at</strong>es. The Brecht, Benjamin and Enzensberger essays are three of the introductory essaysin Hanhardt's widely-read collection <strong>Video</strong> Culture: A Critical Investig<strong>at</strong>ion (alongsidefurther chunks of cultural pessimism from Louis Althusser and Baudrillard). And thequot<strong>at</strong>ions above help identify the essential <strong>at</strong>ittudes towards television among radicalthinkers from the 1960s on: suspicion, disdain and rejection on the one hand, and theurgency of a response to expose the workings of the media and promote particip<strong>at</strong>ionr<strong>at</strong>her than passivity. These are the same <strong>at</strong>titudes exemplified by the critical writingsabout video quoted earlier, and by the two tapes discussed.9

TV, in a highly visual culture, drives us inward in depth into <strong>at</strong>otally non-visual universe of involvement. It is destroying ourentire political, educ<strong>at</strong>ional, social, institutional life. TV willdissolve the entire fabric of society in a short time. If youunderstood its dynamics, you would choose to elimin<strong>at</strong>e it as soonas possible (as quoted by Ross 1989: 119).Given the prevalence of (perhaps slightly less extreme variants of) such <strong>at</strong>titudes in the1960s and 1970s, the convenience, and indeed the possibilities, of being able to legitimizevideo an against television are apparent. Early video exhibition titles, such as "TV as aCre<strong>at</strong>ive Medium" (1969) and "Vision and Television" (1970) reflect the desire both toacknowledge the frightful parent, but also to challenge it. <strong>At</strong> the time cre<strong>at</strong>ivity and visioncould be assumed to be so clearly antithetical to television, or r<strong>at</strong>her to the predominantunderstandings of television, th<strong>at</strong> just linking these qualities with the idea of television wasinevitably to offer opposition to th<strong>at</strong> idea. Many among the target audiences of these shows—from the art world and museums, from critics and l<strong>at</strong>er from funding agencies and thosewho s<strong>at</strong> on their panels—certainly shared the <strong>at</strong>titudes to television sketched above, and sothe legitim<strong>at</strong>ion of the fledgling medium of video against television was perfectlyacceptable, and for many must have seemed excitingly radical.Now consider an excerpt from a videotape about television made ten years afterTelevision Delivers People. The shot is of a young girl lying on the floor w<strong>at</strong>ching an offscreentelevision. As she tells her story, two adults—seen only from the waist down—appear behind her. .11

"The last time I saw my parents kiss was twenty-five years ago" sheremembers, "I was lying on the living room floor w<strong>at</strong>ching TV.Dragnet was on and th<strong>at</strong> music, th<strong>at</strong> horribly scary music was fillingthe room and my soul with pure terror, it was a show about Friday'spartner, who'd just been killed in action. Here I was trying to feelsafe and secure in the good TV graces of Sargeant Friday andinstead I was plugging my ears and shaking. Th<strong>at</strong>'s the way I w<strong>at</strong>chDragnet week after week. Then my parents came in to saygoodnight. They were going to a party. Mom looked so pretty in herorange sequined dress. And Dad looked so handsome in his bluemetallic suit. They bent over to say goodbye and then embraced andkissed right in front of the TV set. Then they walked out just as th<strong>at</strong>horrible music reverber<strong>at</strong>ed through the entire house. This time Ididn't have to plug my ears. Their kiss made me stfong enough tow<strong>at</strong>ch the final credits without shuddering" (Desmarais 1990: 54).This is from Ilene Segalove's Why I Got Into TV and Other Stories, a tape th<strong>at</strong>seems not to be exhibited, nor to be . written about, nearly as much as Television DeliversPeople. Nor does the critical consensus th<strong>at</strong> exists accord Segalove's tape a reput<strong>at</strong>ionanywhere close to the st<strong>at</strong>ure of Serra and Schoolman's piece. Yet it is comparably bold andsimple, and it challenges the conventions of television language <strong>at</strong> least as effectively12

with its knowing re-framing of a domestic encounter. The tape (unlike Television DeliversPeople) also has gre<strong>at</strong> charm and humor, and it wants to be w<strong>at</strong>ched and enjoyed.Unlike most artists' videotapes about television, this section of Why I Got Into TVis also about a particular program. The tape is so delic<strong>at</strong>e, funny and pleasing th<strong>at</strong> it wouldbe too easy to overburden it with a complex analysis, but it is important to recognize th<strong>at</strong>the tape explores how th<strong>at</strong> program was part of one young girl's fears and fantasies, andhow it became part of her life. And unlike most artists' tapes which protest the means'oftelevision production and urge resistance, this is a tape about consumption, about w<strong>at</strong>chingtelevision and making it a part of your life. Nor is consumption here simply passivereception, a process in which the viewer is manipul<strong>at</strong>ed by the consciousness industry.Instead, it is simply an element of everyday life, an element th<strong>at</strong> gets mixed up witheverything else going on, and an element th<strong>at</strong> can enrich and deepen one moment of thegirl's rel<strong>at</strong>ionship with her parents.The understanding of television encapsul<strong>at</strong>ed in Segalove's tape, parallels an.analysis of mass media which has been developed, primarily in Britain, over the pasttwenty years. This has come to be know as the "uses and gr<strong>at</strong>ific<strong>at</strong>ions" model, and itscentral idea is summed up in this suggestion from one of its pioneers, James Halloran: "Wemust get away from the habit of thinking in terms of wh<strong>at</strong> the media do to people andsubstitute for it the idea of wh<strong>at</strong> people do with the media" (as quoted by Morley 1980: 12).As with the post-Frankfurt School ideas explored above, this model (and itssubsequent refinements, adjustments and often radical re-workings by researchers such as13

David Morley) can be presented here only in sketch form. Mick Counihan's 1972summary, however, is useful as a pointer to the main ideas:...(A)udiences were found to `<strong>at</strong>tend to' and 'perceive' mediamessages in a selective way, to tend to ignore or to subtlyinterpret those messages hostile to their particular viewpoints.Far from possessing ominous persuasive and other anti-socialpower, the media were now found to have a more limited and,implicitly, more benign role in society; not changing, but'reinforcing' prior dispositions, not cultiv<strong>at</strong>ing 'escapism' orpassivity, but capable of s<strong>at</strong>isfying a gre<strong>at</strong> diversity of 'uses andgr<strong>at</strong>ific<strong>at</strong>ions', not instruments of a levelling of culture, but of itsdemocr<strong>at</strong>iz<strong>at</strong>ion (Morley 1980: 6).It is notable, however, th<strong>at</strong> ideas such as these are almost never reflected in theapproaches to television within artists' videotapes. Why I Got Into TV and Other Stories isremarkable (as are other tapes by Segalove) precisely because it is concerned with the"uses and gr<strong>at</strong>ific<strong>at</strong>ions" th<strong>at</strong> one viewer derives from one television program, and withher active and strongly particip<strong>at</strong>ory rel<strong>at</strong>ionship with it. For all its seeming fragility andinconsequentiality, Why I Got Into TV is an important challenge to the deep-se<strong>at</strong>ed andendlessly repe<strong>at</strong>ed orthodoxy th<strong>at</strong> "television delivers people".14

If the reception of television can be understood as offering far more than wasallowed by the ideas dominant from the 1960s on, so should the production of the medium.Twenty years ago, television in the United St<strong>at</strong>es comprised only network affili<strong>at</strong>es andlocal st<strong>at</strong>ions th<strong>at</strong> wished to be network affili<strong>at</strong>ies, together with the worthy butdesper<strong>at</strong>ely underfunded public broadcasting st<strong>at</strong>ions. PBS oper<strong>at</strong>ors are still underfundedtoday, and throughout the system the underlying commercial imper<strong>at</strong>ive is no lessimportant. Yet the television ecology is now far, far more varied, with numerous cable ands<strong>at</strong>ellite services supplementing and challenging the no longer overwhelmingly dominantnetworks. As the critic Marita Sturken recognized in 1984:Network television as we have known it is slowly becomingobsolete. Vast, expensive, centralized, inflexible, it is thedinosaur of the 1980s and 90s gradually giving way to anelectronic entertainment industry th<strong>at</strong> includes multiple channels,increased distribution via s<strong>at</strong>ellite, home recorders, and, forviewers, radically new elements of choice.Abroad, of course, since television started, there have been altern<strong>at</strong>ive modes offinancing, production and distribution quite different from those of the commercialnetworks. And in the last decade, despite the drive in many countries towards deregul<strong>at</strong>ionof st<strong>at</strong>e controls and increasing market pressures which are thought by many to stifledistinctive services, new television organiz<strong>at</strong>ions like Channel 4, London and France's15

Canal Plus and La Sept have demonstr<strong>at</strong>ed remarkable possibilities for the funding andexhibition of a very wide range of work.Political, economic and technological forces working on television todaythroughout the world are bringing a gre<strong>at</strong>er differenti<strong>at</strong>ion and variety to the medium thanever before. To some degree, since the changes are taking place <strong>at</strong> a dizzying pace, such ast<strong>at</strong>ement has to be as much article of faith as informed and accur<strong>at</strong>e analysis. But as thenumber of services throughout the world prolifer<strong>at</strong>es, and as audiences fragment into amultitude of new configur<strong>at</strong>ions, many new possibilities—for artists, just as for othermoving image makers—are opened up. The appetite of this vast industry is voracious, andelements of it no longer need to appeal, as did the American networks, to the largest massaudiences. Indeed, services will increasingly target specific demographic and particularinterest groups. To <strong>at</strong>tract these audiences, they will also need to define and presentthemselves as distinct altern<strong>at</strong>ives to the dominant structures.Moreover, distribution will no longer be constrained by broadcasting models andtechnologies which carry their own impetus towards maximizing an audience. The idea oftelevision already encompasses more than just wh<strong>at</strong> comes out of the air or down thecable. Cassettes and video games have begun to give us a quite new sense of thepossibilities of the box in the corner, and this is likely to develop rapidly with, for example,the introduction of interactive compact disc (CD-I) systems in the next two years. CD-I,backed by Sony and Phillips, offers the possibility of interactive moving images for thedomestic set. A wide range of uses are envisaged, including educ<strong>at</strong>ional discs, games andinteractive dramas.16

The production of programming primarily intended for broadcast will inevitablycontinue. But this seems likely to be increasingly lower cost (or compar<strong>at</strong>ively so), rapidturn-over programming, such as game shows, soaps, sports and news. Alongside this,production and distribution of discrete programs like dramas and documentaries, as well asartists' tapes, may follow more and more closely a publishing, r<strong>at</strong>her than a broadcasting,model. Different sources of finance will be brought together to fund a single production,and a wide range of distribution outlets may be possible. Television exhibition may beone of these, but so, for example, will cassette or video disc distribution.Such broad strokes of specul<strong>at</strong>ion can suggest th<strong>at</strong> in the coming decade therewill be (<strong>at</strong> least in an intern<strong>at</strong>ional context) a far gre<strong>at</strong>er variety of production funding andfinancing, the number and range of distribution systems will continue to increase, as willpossibilities for exhibition, and rel<strong>at</strong>ionships between televisions and audiences will beunderstood in new ways. All of which should offer important opportunities andchallenges for everyone, including artists, working with moving images.In crudely commercial terms, artists are in many ways well-placed to exploit theopportunities which are opening up. As sources of novel, distinctive and powerfullypresentedideas and images, they should be sought after by <strong>at</strong> least some of the newtelevision structures. And as artisanal producers, their costs are often (compar<strong>at</strong>ively) low,and copyrights and ownership are (compar<strong>at</strong>ively) straightforward.For two reasons, however, this essay is not intended to conjure up the vision of anew television utopia for artists' video. The first reason is, obviously, th<strong>at</strong> most of the new17

services already do, and will continue to share the languages, values and ideologies familiarfrom the commercial networks. But it seems likely th<strong>at</strong> the images will no longer be asrigidly directed towards audience maximiz<strong>at</strong>ion and profit as they once were. The dominantlanguages will no longer be quite as dominant, and altern<strong>at</strong>ives will be recognized and evenvalued. The contradictions of television, and of the meanings and ideas offered by it, maybecome richer, stronger and more exciting.The production and exhibition contexts opening up will inevitably entail limit<strong>at</strong>ionsand constraints, just as do those of the gallery and the museum. Television's limit<strong>at</strong>ions willbe different, but they will not necessarily be more onerous. Wh<strong>at</strong> seems important is th<strong>at</strong>the video art world's dominant ideas about television, as sketched above, should not preventthe widest range of responses.Recent history, however, suggests th<strong>at</strong> the blinkers about television may remain. Ashas been suggested, the range and richness of television has rarely been recognized in themajority of tapes produced by artists. Nor has it often been acknowledged by cur<strong>at</strong>ors andcritics writing about or assembling exhibitions or programs. As David Antin observes,Television haunts all exhibitions of video art, though whenactually present it is only minimally represented, with perhaps afew commercials or "the golden performances" of Ernie Kovacs (<strong>at</strong>elevision "artist"); otherwise its presence is manifest mainly inquotes, allusion, parody, and protest (included in Hanhardt 1986:148).18

In part precisely because of video art's struggle for legitim<strong>at</strong>ion, and an inevitabledefensiveness in its early years, the form has been concerned to assert its individual anddistinctive histories and traditions. As a consequence, video has been confined to a limitedcontext, and seen as separ<strong>at</strong>e from developments in film, in television and in other movingimage media like digital anim<strong>at</strong>ion. There are signs th<strong>at</strong> this is beginning to change, and twomajor European exhibitions in the autumn of 1990—Passages d'Image <strong>at</strong> the Centre GeorgesPompidou, Paris and The First Biennial of the Moving Image <strong>at</strong> the Reina Sofia Centre inMadrid—specifically address the rel<strong>at</strong>ionships between video and other forms of the movingimage. But in the past the understanding of video as separ<strong>at</strong>e from rel<strong>at</strong>ed media has meantth<strong>at</strong> video in the eyes of both its cre<strong>at</strong>ors and its critics, has tended to be cut off from likelyenrichment by other elements of our contemporary moving image culture.If the dominant <strong>at</strong>titudes are to change, as' l believe they should, the shift maycontribute to the possibly inevitable, and probably positive, dissolution of video art's currentidentity. <strong>Video</strong> art was never defined or legitim<strong>at</strong>ed internally either solely by technology orby a shared language. Nor, as I have argued, should it have been defined and legitim<strong>at</strong>edprimarily by reference to the external evil of television. Its identity, today as for much of itshistory, is .an institutional one, formed and sustained by now compar<strong>at</strong>ively well-establishedstructures of cur<strong>at</strong>orship, criticism and distribution. Even a slowly developing market, forinstall<strong>at</strong>ions and for archive-quality museum copies of tapes, is beginning to make acontribution to this identity.The primarily institutional n<strong>at</strong>ure of video art's identity today may inhibit the19

development of new rel<strong>at</strong>ionships between artists' video on the one hand and broadcasttelevision and new forms of moving image media on the other. (And this is the otherreason why my arguments are not intended to conjure up a vision of television as anew utopia for artists' video.) The possibilities th<strong>at</strong> may be opening up should beexplored and exploited by all those concerned to extend the potential of movingimages. And arguing and lobbying and working for the presence of something called"artists' video" will be, <strong>at</strong> best, only an exceptionally limited str<strong>at</strong>egy for extendingthis potential. It perpetu<strong>at</strong>es the idea of artists' video as distinct from, and indeedopposed to, television. And the str<strong>at</strong>egy will also inevitably perpetu<strong>at</strong>e television'scondescension towards and marginaliz<strong>at</strong>ion of artists' work.An altern<strong>at</strong>ive str<strong>at</strong>egy, and one th<strong>at</strong> seems to offer far more possibilities, is towork to understand the many different oper<strong>at</strong>ions of television's new structures, and toaccommod<strong>at</strong>e to a limited degree to these, while still offering challenging altern<strong>at</strong>ives tothe dominant ideas and languages of these structures. Artists like William Wegman andJohn Sanborn and Mary Perillo have achieved this by working within the commercialstructures of the medium. Wegman's recent sketches for Children's TelevisionWorkshop are as engaging as his earlier short works and his 1988 promo (co-directedwith anim<strong>at</strong>or Robert Breer) for New Order's Blue Monday (Remix) is a joyous threeminutes of image-making. Both the sketches and the promo encapsul<strong>at</strong>e Wegman'sindividual take on the world, even if they may seem as inconsequential and as fragile asIlene Segalove's Why I Got Into 7V.20

Sanborn and Perillo's work is seen by some as making too gre<strong>at</strong> an accommod<strong>at</strong>ion totelevision, so th<strong>at</strong> their manipul<strong>at</strong>ions of high-tech wizardry drain any substance fromthe work. Yet their Untitled (1989), made with the dancer and choreographer Bill T.Jones for PBS' Alive From Off Center, refutes any such criticism. Untitled is a simple,powerful and intense dance lament for Bill T. Jones' partner Arnie Zane, who died ofAIDS in 1988. Driven by a passion th<strong>at</strong> is both personal and political, the tape is asmoving and as memorable as the finest achievements in any medium.Two major recent tapes th<strong>at</strong> achieve a different accommod<strong>at</strong>ion withtelevision, yet still remain entirely distinctive, are Bill Viola's I Do Not Know Wh<strong>at</strong> It IsI Am Like (1986) and Gary Hill's Incidence of C<strong>at</strong>astrophe (1988). Both were partfundedby television, the former by ZDF and the l<strong>at</strong>ter by Channel 4, London. For alltheir many differences, both engage with long-established television forms, Viola'swith the n<strong>at</strong>ural history documentary, and Hill's with the adapt<strong>at</strong>ion of a classic literarytext. Yet both cre<strong>at</strong>e radical altern<strong>at</strong>ives to television's dominant languages, and eachemerges as a complex explor<strong>at</strong>ion of spirituality and identity. Both are alsouncompromising in their form and structure. <strong>At</strong> the most obvious level, Viola'smedit<strong>at</strong>ive images are held far longer than television usually permits, but it is with thisreflective scrutiny of the n<strong>at</strong>ural world th<strong>at</strong> the artist undertakes his religious quest. In aparallel manner, - Hill's fragmented and dispassion<strong>at</strong>ely cruel self-confront<strong>at</strong>ioncontributes to a tape th<strong>at</strong> is, in the most positive sense, profoundly unsettlling. (Themany problems of the str<strong>at</strong>egy of working with television may be suggested by the fact21

th<strong>at</strong> despite supporting the production of Incidence of C<strong>at</strong>astrophe more than two years ago,Channel 4 has still not screened the tape.)Each of these works by Wegman, Sanborn and Perillo, Viola and Hill offers a wayforward for moving images to explore and express new ideas in new ways. Each wasproduced with a strand of the varied and dispar<strong>at</strong>e institution th<strong>at</strong> television has become.Each is screened on television, as well as being shown extensively elsewhere. Each engageswith television's forms, while <strong>at</strong> the same time offering altern<strong>at</strong>ives. Each offers an implicitcritique of the generally impoverished languages of the medium, but constructively so.Each of the works suggest th<strong>at</strong> video art can see beyond the traditional <strong>at</strong>titude of rebelliontowards a once-frightful parent, and so achieve a new rel<strong>at</strong>ionship with television th<strong>at</strong> bothparent and offspring, together with the rest of us, will find enriching.ReferencesAntin, David. "<strong>Video</strong>: The Distinctive Fe<strong>at</strong>ures of the Medium" in John G. Hanhardt, ed.,<strong>Video</strong> Culture: A Critical Investig<strong>at</strong>ion, New York: Peregrine Smith Books (1986).Baudrillard, Jean. "Requiem for the Media" trans. by Charles Levin in Hanhardt, ed., <strong>Video</strong>Culture: A Critical Investig<strong>at</strong>ion, New York: Peregrine Smith Books (1986).22

Brecht, Bertolt. "The Radio as an Appar<strong>at</strong>us of Communic<strong>at</strong>ion" trans. by John Willett, inHanhardt, ed., <strong>Video</strong> Culture: A Critical Investig<strong>at</strong>ion, New York: Peregrine Smith Books(1986).Coulihan, Mick. "Orthodoxy, Revisionism, and Guerilla Warfare in Mass Communic<strong>at</strong>ionsResearch", CCCS mimeo, University of Birmingham, quoted in Morley (1980).Davis, Douglas. "The End of <strong>Video</strong>: White Vapor" in Gregory B<strong>at</strong>tock, ed., New Artists<strong>Video</strong>: A Critical Anthology, New York: E.P. Dutton (1978).Enzensberger, Hans Magnus, "Constituents of a Theory of the Media" trans. by StuartHood, in Hanhardt, ed., <strong>Video</strong> Culture: A Critical Investig<strong>at</strong>ion, New York: Peregrine SmithBooks (1986).Hanhardt, John G. (1984). "<strong>Video</strong> Art: Expanded Forms—Notes Towards a History" in TheLuminous Image, exhibition c<strong>at</strong>alogue, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.Huffman, K<strong>at</strong>hy (1983) The Second Link : <strong>Video</strong> Viewpoints in the 1980s, Banff, Canada:Walter Phillips Gallery.Lovejoy, Margot (1989) Postmodern Currents, Ann Arbor and London: UMI ResearchPress. -23

McLuhan, Marshall, and Steam, Gerald " A Dialogue" in Stearn, ed., Hot & Cool, NewYork: Dial Press (1987).Morley David (1980). The "N<strong>at</strong>ionwide" Audience. London: British Film Institute.Perree, Rob (1988) Into <strong>Video</strong> Art: The Characteristics of a Medium,Rotterdam/Amsterdam: Con Rumore.Rosier, Martha. "<strong>Video</strong>: Shedding the Utopian Moment" in Rene Payant, ed., <strong>Video</strong>,Montreal: Artextes (1986).Ross, Andrew (1989) No Respect: Intellectuals & Popular Culture. New York andLondon: Routledge.Schneider, Ira and Korot, Beryl (1976) eds., <strong>Video</strong> Art: An Anthology, New York andLondon: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.Segalove, Ilene (1990). "Dragnet Kiss" in Charles Desmarais, ed., Ilene Segaloveexhibition c<strong>at</strong>alogue, Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach.24

Five Answers to the Question: Wh<strong>at</strong> Has TV Meant in Your LifeTV taught me alien<strong>at</strong>ion. I turn it on and see something th<strong>at</strong>'s not me.$75,000 on Jeopardy.How I learned Paul McCartney got married.Star Trek before dinner.The only friend who hasn't run out on me.My parents were so proud the day they saw me on tv.

POLITICAL VIDEO IN THEUNITED STATES:A STATEMENT FOR THE 1990sJOHN DOWNINGWh<strong>at</strong> is politics?It is no longer, so easy to say. In the USA the word has been degraded to the pointth<strong>at</strong> convers<strong>at</strong>ionally it signifies the vicious thro<strong>at</strong>-cutting of bureaucr<strong>at</strong>ic intrigue, and so hascome to dignify the small everyday maneuvers of base cunning. "I loved th<strong>at</strong> job, nobody wasin the least political."/ "I h<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong> job, everyone was so political."For "politics" to shrink to the lust for power in the micro-environment of stagnantoffice ponds represents a sorry decline, a lurch downhill even from its redefinition as thehoopla of quadrennial presidential media circuses. In these an echo of n<strong>at</strong>ional political deb<strong>at</strong>esurvives, a sense th<strong>at</strong> space might be open for a candid<strong>at</strong>e such as Jesse Jackson to101

aise genuine issues however much the media punditry, in its infinite, infinite perspicacity, mightseek to drown them in a torrent of icy scorn. In the lilliputian cosmos of bureaucr<strong>at</strong>icdepartments, however, the more intense and engaging the "politics" the less likely will the issuestranscend personal spites and ascendancies—wh<strong>at</strong>ever the rhetoric.In this essay I 'am using "politics" in its archaic, now almost arcane sense, to denote theclash of opinion, analysis and actions between social forces set in fundamental opposition to eachother: feminists against p<strong>at</strong>riarchy, N<strong>at</strong>ive Americans against coloniz<strong>at</strong>ion, environmentalistsagainst energy corpor<strong>at</strong>ions, African-Americans against institutionalized racism, workers againstpay-cuts, lay-offs, medical benefit cuts, increasing debt-bondage... The list needs to becontinued <strong>at</strong> length, the interconnections recognized, and the problem<strong>at</strong>ic deepened to questionsof capital and the st<strong>at</strong>e (though doing so need not—must not—lure us either into the pop-eyedmessianism of some grouplets on the left, or the kneejerk pro-sovietism of others). So by"politics" I particularly mean the demands, the consciousness, the activity of politicalmovements, ebbing and flowing in strength, based in everyday struggles and confront<strong>at</strong>ions.Usually in' the United St<strong>at</strong>es these movements have had a very specific focus, such aspeace or civil rights, sometimes termed "single-issue" politics. In reality, many of these "single"issues, properly understood, raised profound questions about the n<strong>at</strong>ional political economy andculture, and are only defined as detached issues <strong>at</strong> the risk of seriously misconceiving them.However, since the Socialist Party's collapse after World War I, numerous experiences right upto the problems of the "rainbow" coalitions of the 1980s testify to how difficult it is to sustainpolitically integr<strong>at</strong>ed opposition across this very large and diverse country.102

To this sociological obstacle must be added the seemingly indelible legacy of".anticommunism" as a n<strong>at</strong>ional political religion which, to this very day, can be . mobilized todiscountenance—in a flash—almost every radical analysis or movement. Newsreel footage ofyoung U.S. soldiers walking forward into nuclear blast test-zones in the 1950s engraves asperhaps no other image can, the absolutism of U.S. anticommunism. Integrally with thisanticommunism, the summons to compete with the other superpower or go under has workedalmost unfailingly in favor of astronomical, sloppily evalu<strong>at</strong>ed military budgets, but againsteduc<strong>at</strong>ion, affordable health care and a healthy environment. Had it not been for theanticommunist impulse, could the st<strong>at</strong>e-by-st<strong>at</strong>e pork-barrel politics of Federal funding not haveembraced constructive needs as easily as destructive ones?The bold political moves of the Gorbachev team in the l<strong>at</strong>e 1980s and the suddenchanges in Central Europe in 1989 began for the first time to erode the appeal of thissummons, so dram<strong>at</strong>ically indeed th<strong>at</strong> much of the American power structure tookconsiderable fright (1). As Soviet political analyst Georgi Arb<strong>at</strong>ov once observed, ademonic USSR is as essential to business as usual in the USA as is the devil to afundamentalist'preacher...(1) In fact the Cold War propaganda machine's definition of the world has rarely been believed all th<strong>at</strong> strongly by senior tforeignpolicymakers themselves. The cynicism of the U.S. government's realpolitik was particularly in evidence in 1989 for anyone with eyes.People's judgments as to the most sickening examples will vary but.the tolerance of extreme violence by good" communists wenthand in glove with the almost totalitarian exclusion ol• "bad" communists, and the aversion tooppression by 'bad" dict<strong>at</strong>ors ncstledcosily with a blind eye to the <strong>at</strong>rocities of "good" ones...'bad"massacre around Tiananmen Square was met with embarrassment r<strong>at</strong>her than fin and brimstone, and theChinese government-supported Khmer Rouges victims were reduced to "about &.million" from the oft-cited three million and up earlierin the decade. Yet' Salvadorean guerrillas and Sandinistas were demonized; to the point where a terrified couple who hadwitnessed the Salvadorean Army's slaukhter of six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her daughter were thre<strong>at</strong>ened by the FBI withthe nigghtmare of deport<strong>at</strong>ion bacfi to El Salvador in the course of their interrog<strong>at</strong>ion, and here murderous U.S.-armed Contrastuclta an Nicaraguan civilians went without comment by Bush Administr<strong>at</strong>ion parrot. General Noriega's misdeeds were suddenlyblazoned everywhere, no doubt because of U.S. government anxieties about the Panama Canal; sustained repression by rulers, militaryor otherwise, in Gu<strong>at</strong>emala, Zaire, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and many other n<strong>at</strong>ions closely allied to the USA, continued unremarked.Without "communism" can these realpolitik c<strong>at</strong>egories continue to be masked? Wh<strong>at</strong> will be the next panic-buaon?103

In the USA politics most times involves the intern<strong>at</strong>ional context as well as n<strong>at</strong>ionalrealities. Beyond superpower rel<strong>at</strong>ions and their bearing' on domestic life, the United St<strong>at</strong>es'activity in policing the Americas since 1898 and the globe since 1945, has been no minorincidental in our political life (Korea, Cuba, Vietnam', Falasta-Israel, Iran, Nicaragua, ElSalvador, etc.), ignorant of the rest of the planet as many U.S. citizens.are, and convinced as areso many of them th<strong>at</strong> their country is a kind of hallowed island. Th<strong>at</strong> "island" was cre<strong>at</strong>ed bycoloniz<strong>at</strong>ion, from the first wars against N<strong>at</strong>ive Americans through the annex<strong>at</strong>ion of northernMexico in 1848 to the seizure of Hawaii and the Philippines in the 1890s. It is sustained todayby a vast intern<strong>at</strong>ional network of banks and military bases, mining corpor<strong>at</strong>ions andagribusinesses, media megaliths and space hardware.It follows th<strong>at</strong> political communic<strong>at</strong>ion in the USA is intensely important both for itscitizens and for the planet as a whole. A politically unlettered and globally uninformed U.S.elector<strong>at</strong>e is dangerously exposed, and a danger to others. If we do not exploit as intensively aspossible the scope th<strong>at</strong> the st<strong>at</strong>e and the culture provide for altern<strong>at</strong>ive political communic<strong>at</strong>ion,we can the more easily be suckered into supporting aggressive foreign policies. In the nuclearand chemical weapons era these policies could quite quickly lead to the extinction of all humanlife, or neg<strong>at</strong>ive domestic policies of many kinds, damaging the environment, thre<strong>at</strong>ening therights of immigrants, the health care of the elderly. (An irony of living in the USA is the giganticvolume of free or cheap inform<strong>at</strong>ion lying around unexploited, such as d<strong>at</strong>a on transn<strong>at</strong>ionalcorpor<strong>at</strong>ions, which could be used fruitfully by political movements in many "Third World"n<strong>at</strong>ions where it is virtually unavailable.)104

To come to the immedi<strong>at</strong>e question of political video for the nineties, I would argueth<strong>at</strong> there are certain issues, each one with intern<strong>at</strong>ional dimensions, which video-makerswith a conscious political commitment should take as priorities—which, indeed, any videomakertoday should seriously consider. In turn, my judgment will govern the selection ofthe videos for comment in this essay. The issues are class, racism, p<strong>at</strong>riarchy and ecologicalruin.Properly defining each here and justifying its priority is beyond the scope of a shortessay: I would only say th<strong>at</strong> these issues are deeply interconnected, as many of the videosselected make plain.I am defining social class not on the level of the rel<strong>at</strong>ive trivia of st<strong>at</strong>us differences,but as economic power rel<strong>at</strong>ions together with their countless ramific<strong>at</strong>ions. "Class" is not aliving concept in our political vocabulary in the USA, but the reality it signifies mostcertainly expresses itself in all directions, often transmuted into sp<strong>at</strong>ial terms such as "WallStreet", or "Beverly Hills" or "The Loop". Racism is a term in the political vocabulary, yetcontinues nonetheless to be the solar plexus of the culture, the nettle of choice for Whitepeople to refuse to grasp; denials of full humanity to non-White people take endless formsand s<strong>at</strong>ur<strong>at</strong>e the social system. P<strong>at</strong>riarchy has much of the same sinewy strength but is not sopeculiarly Anglo-American, and along with ecological ruin is today given somewh<strong>at</strong> moreintelligent consider<strong>at</strong>ion in the official public sphere than social class or racism. Together,however, these four forces confront us, and only numbed fools would set up a competitionfor which is most dangerous.But they do not only confront us. They are also part of us. They are not Martianculture. Our culture. Us.105

Wh<strong>at</strong> is video?Of the numerous dimensions to political communic<strong>at</strong>ion, the task here is to review just one,namely video. But video also needs defining.We might as well begin by asking wh<strong>at</strong> if anything is the difference between videoand television? As a visceral reaction. against the banality of most television programmingin the USA, the term "video" has been reserved by some to denote television programs withartistic qualities.The direct reaction , by film and video artists to the consuming andomniscient worlds of commercial. television and cinema is, in onesense, <strong>at</strong> the basis of all films and videotapes th<strong>at</strong> reject theproduct which fills the cinema screen or television monitor(Hanhardt 1989: 97).Indeed, comment<strong>at</strong>or after comment<strong>at</strong>or, critic after critic, talks about "television"when wh<strong>at</strong> they essentially mean is U.S. television (e.g. Miller 1988; Fiske 1988). Even aBritish writer (Armes 1988)—curiously, given th<strong>at</strong> British television has historically beenof a higher calibre than most—wrote a book entitled On <strong>Video</strong> and spent many pages of itexploring in cumbersome detail how video is to be distinguished from both film andtelevision.106

Is it really a meaningful exercise to concentr<strong>at</strong>e as he does on differences inaudience, and differences in p<strong>at</strong>ronage and contracts for the original production, as though allthese cre<strong>at</strong>ed a generic difference between video and TV? All these are important elementsin the situ<strong>at</strong>ion, but in Armes' text they make up a line of argument which reproduces theseemingly interminable nausea of the "high art/low art" deb<strong>at</strong>e, which has been dealt someweighty critical blows by a number of video critics (e.g. Antin 1976; Gever 1985; James1986).James, for example, points out how many of the techniques of so-called "video art"have been borrowed by mainstream television producers, and one might also note the waymany video-makers reproduce r<strong>at</strong>her than critique current televisual cliches. Or as thisquot<strong>at</strong>ion from the British magazine ZG puts it:...certain self-consciously borderline activities have grown upwhich aim to work between "styles" and their worlds... Hybridstyles abound... these new tendencies...challenge our most deeprootedorient<strong>at</strong>ions to the world whether they are in terms ofart/culture, elite/popular, or male/female... (cited in Walker 1983:87)Despite a number of insightful remarks sc<strong>at</strong>tered through his text (especially on thequestion of sound), Armes tends to produce st<strong>at</strong>ements such as this:107

...the video camera...is openly, transparently, both an instrument forcelebr<strong>at</strong>ing wh<strong>at</strong> is, r<strong>at</strong>her than wh<strong>at</strong> could be achieved by social change,and, <strong>at</strong> the same time, a machine for making life seem more pleasurablethan it is. (197)He endeavors, then, to develop an intric<strong>at</strong>e essentialist specificity for TV, , comparing itwith photography a la Barthes (1977) in its tendency to "n<strong>at</strong>uralize'.', drawing the nowfamiliar contrast with the big screen/darkened space/specially assembled audience ofcinema, noting the effect of current computerized averaging of light on foreground andbackground composition. In the process, however, the fluid boundaries between film,television and video are curiously posited as fixed, <strong>at</strong> least for the discerning eye and ear.This is despite the onset of advanced comp<strong>at</strong>ible television and high definitiontelevision—the l<strong>at</strong>ter now <strong>at</strong> the doors-as much for its military and remote sensingapplic<strong>at</strong>ions as for its <strong>at</strong>tractiveness to the television audience which look set to explodesome prem<strong>at</strong>ure aesthetic theorizing.As or more important than critics' definitions of the medium—I am now junkingthe video/TV distinction, and will use the terms interchangeably-is how the audienceconstitutes it. During the 1980s a younger gener<strong>at</strong>ion of media analysts who had cut theircritical teeth on trashing conventional audience researeh suddenly and avidly rediscoveredthe importance of the media audience. Their own methodology was largely qualit<strong>at</strong>ive andanthropological, sometimes even resembling a diary (e.g. Morley 1986), so this volte-face108

did not represent a total capitul<strong>at</strong>ion to Nielsen.A prolific exponent of this school is Fiske (1988), for whom the televisionaudience is lionized as the "producer of meanings" from the television text. He writes asdoughty champion of the unjustly despised mass audience:Television is a "producerly" medium: the work of the institutionalproducers of its programs requires the producerly work of theviewers and has only limited control over th<strong>at</strong> work. The readingrel<strong>at</strong>ions of a producerly text are essentially democr<strong>at</strong>ic, notautocr<strong>at</strong>ic ones. (239 my emphasis)The recovery of soap .operas and their audiences into cultural andpolitical respectability, is almost complete and thoroughlywelcome... (280)Fiske never defines "limited control", and indeed one is often led by his text tothink he sees the audience as hyperactive r<strong>at</strong>her than as merely active, taking the televisualtext by the scruff of its neck and wrenching its head off in a determin<strong>at</strong>ion to find its ownpleasures r<strong>at</strong>her than the bourgeois ideologies insinu<strong>at</strong>ed—a kind of no-holds-barredmental wrestling from which the original "institutional" producers can only retre<strong>at</strong> indisarray, shaken and hurt by the ferocity of the encounter. The "cultural and political109

espectability " in which these couch-pot<strong>at</strong>oes-turned-titans are now basking is of courseacademic, in the sense of the academic "community"; one hopes it is sufficient reward forthe obloquy under which they have so often groaned in the past, and which has held backmany a guilty hand from switching on the set.Marc Crispin Miller (1988) has argued exactly the opposite position in his essay"Big Brother Is You, W<strong>at</strong>ching". Counterpointing. his analysis of U.S. television-hesimply says "television"—with a reading of 1984, and drawing upon Horkheimer andAdorno's critique (1944/1987) of the destructive cultural impact of capitalist r<strong>at</strong>ionality, heclaims th<strong>at</strong> the audience is stimul<strong>at</strong>ed into homogeneity, into a 1984-like fear ofindividuality, by the codes and rituals of American TV. These he defines as typicallycontrasting the smooth, all-knowing, "in control", normal TV personality with deviants—often conserv<strong>at</strong>ive deviants, who are however trashed for their individuality r<strong>at</strong>her thantheir repressive postures. Longstanding U.S. examples would be Johnny Carson inrel<strong>at</strong>ion to Archie Bunker in All In The Family. He writes:TV seems to fl<strong>at</strong>ter the inert skepticism.of its own audience,assuring them th<strong>at</strong> they can do no better than stay right wherethey are, rolling their eyes in feeble disbelief. 'And yet suchapparent fl<strong>at</strong>tery of our viewpoint is in fact a recurrent warningnot to rise above this slack, derisive gaping... All televisualsmirking is based on, and reinforces, the assumption th<strong>at</strong> wewho. smirk together are enlightened past the point of nullity,having evolved far beyond wh<strong>at</strong>ever d<strong>at</strong>edness we might bejeering, whether the fan<strong>at</strong>ic's ardor, the prude's inhibitions, the110

hick's unfashionable pants, or the snob's obsession with prestige.(326)In other words, a quasi-critical, quasi-active audience is posited by the TVindustry-but an audience whose criticism is molded and channeled, r<strong>at</strong>her than impulsiveand anarchic. The phenomenon is one of "integr<strong>at</strong>ed spontaneity", in the memorable phraseof Dieter Prokop (1973). A banalized, thuggish irony and coarse, know-everythingskepticism—communic<strong>at</strong>ive styles intensively deployed both by O'Brien and the Oceanicelite of 1984 and by the Stalinist machine which was one of Orwell's targets—have beenadopted by U.S. television, Miller argues, to the point where they have become the U.S.audience's internalized censors which inure us against further critical reaction to the worldaround us, largely medi<strong>at</strong>ed via television. In the end, as the title of Miller's piece proposes,Big Brother becomes Us w<strong>at</strong>ching TV.Miller's analysis begins to vault in an interesting way right over the sterile 1980sdeb<strong>at</strong>e about liberal bias in U.S. media. Beyond this, however, the importance of the clash ofperceptions between him and Fiske—all of it on the left, which is still where most of theinteresting deb<strong>at</strong>e is to be found—is th<strong>at</strong> we cannot begin to make useful judgments aboutthe politics of video in the USA without developing our own views of the audience and itsdefinitions of television. Does U.S. television drain us of our non-consumer selves, as Millerargues, or do we make of it, as Fiske proposes, practically wh<strong>at</strong> we will?The nearer we stand to Miller, the more politically urgent become altern<strong>at</strong>ive andradical video-making, distribution, and media educ<strong>at</strong>ion. The nearer to Fiske, perhaps onlymedia educ<strong>at</strong>ion is politically relevant, and even th<strong>at</strong> might be questioned as dotting alreadyvisible i's'and crossing out already obliter<strong>at</strong>ed t's. In fact, for Fiske it would seem111

th<strong>at</strong> politically radical video is doubtfully worth the effort, given the new readings which itsaudiences will insistently produce of it.Craven and dull as it may seem to hew to a center course, neither Miller's norFiske's absolutisms appear to capture the many-stranded realities of televisual politics andaudiences. From the l<strong>at</strong>ter's emphasis on the audience, we may usefully avoid the TV critic'sstandard vice of self-projection on to the public, of arguing simply from text to effect, ofdismissing the audience as moronic. From the former's dissection of the pseudo-democracyof American television, we may maintain our w<strong>at</strong>chfulness against its powerful depoliticizingtrend. Neither however offers us ' too many clues to the two key issues: wh<strong>at</strong> counts aspolitics? and wh<strong>at</strong> can be said about a political televisual aesthetic? The first has beencommented on above; the second will occupy us now.A political televisual aesthetic for the 1990s USAMiller is essentially concerned with the television audience in its capacity as anaudience, invited to conspire in its own emascul<strong>at</strong>ion. The pseudo-democracy of which hespeaks exists in many other realms of the land of the free: women are denied rights overtheir own bodies, people of color face institutional racism, gays have to fear "faggot-112

ashing", toxic agents silently invade our bodies so th<strong>at</strong> corpor<strong>at</strong>e balances will lookhealthy, people with AIDS are segreg<strong>at</strong>ed and spurned, many "illegal" migrant workerslive in fear on subsistence wages.,As I have indic<strong>at</strong>ed above, "politics" for me is wh<strong>at</strong>happens in the movements of struggle against these forces.It is much harder to define a constructive political televisual aesthetic. Forpolitical aesthetics cannot flo<strong>at</strong> in a political vacuum, valid for every place and time.Indeed one of the problems of radical political writing about aesthetics is its tendency to tryto establish absolute criteria, whether of production or reception.I emph<strong>at</strong>ically do not share the understanding th<strong>at</strong>...video's formal project [is] the critique of the codes ofbroadcast tv as an intervention in the l<strong>at</strong>ter ' s ideological function(James: 88):For one thing, even though tv critiques are fine and necessary, we should not risk havingour ground defined for us by broadcast tv. Our media politics should strive to beautonomous, influenced more by political movements than by the hegemony of dominantideology. It should be cre<strong>at</strong>ing altern<strong>at</strong>ive public spheres and be organized in self-managedstructures (Downing 1984; 1987; 1988; 1989).This is why I feel obliged to <strong>at</strong>tack the media theory which argues th<strong>at</strong>represent<strong>at</strong>ion constitutes us, and therefore th<strong>at</strong> media art which directly confronts thecanons of mass media is the key to media politics:113

...the recognition th<strong>at</strong> there can be no reality outsiderepresent<strong>at</strong>ion, since we can only know about things through theforms th<strong>at</strong> articul<strong>at</strong>e them... As image-makers, artists...havecome to terms with the mass media's increasing authority anddominance through a variety of responses—from_ celebr<strong>at</strong>ion tocritique, analysis to activism, commentary to intervention(Phillips 1989: 67,57).Such an approach goes beyond the medi<strong>at</strong>ic and becomes media-centric, infl<strong>at</strong>ingthe perfectly valid and politically inform<strong>at</strong>ive analysis of codes and signs in mainstreammedia into an all-encompassing explan<strong>at</strong>ion of hegemony. One can see why video artistsand media studies specialists might be drawn to its exagger<strong>at</strong>ed claims, since these in turnseem to bolster the significance of their professional undertakings, in contrast to moretraditional studies in liter<strong>at</strong>ure and political science. The Whitney Museum exhibit volumeImage World: Art and Media Culture in which are to be found both Phillips' essay andHanhardt's referred to earlier, presents a brilliant visual survey of modern artisticresponses to mass media. Nonetheless, media-supremacism lends itself to such specul<strong>at</strong>iveexcess as the argument th<strong>at</strong> narr<strong>at</strong>ive is inherently p<strong>at</strong>riarchal, which may be delicious tocontempl<strong>at</strong>e in the airy redoubts of some Midwestern gradu<strong>at</strong>e school but offers little th<strong>at</strong> isvery chewable elsewhere. It is urgent th<strong>at</strong> media politics, video politics, should notconfine itself to a discourse internal to media or TV.114

Furthermore, "television" is capable of critiquing itself, as witness the classicMonty Python's Flying Circus. Yet again, many <strong>at</strong>tempts by video artists to break through the"codes" are so labored and indigestible except to a dedic<strong>at</strong>ed "video art" clique th<strong>at</strong> it isdoubtful the codes can be said to have been significantly ruptured (e.g. Tony Conrad'sBeholden To Victory and Lee Warren's and Remo Balcells' The Grooming Tool). Buchloh's(1985) comments on uncomprehending audience reactions to some of the videos he reviews,serve to make a similar point.I will begin instead from an impermissible posture: in the 1990s, in the USA,political aesthetics should primarily aim to be energized from the movements against class,racism, sexism and ecological ruin, and most particularly to enable the voices of thosestruggling to be heard.My crime is obvious. Not only am I confusing message with form, but I am indanger of <strong>at</strong> best populism, <strong>at</strong> worst copying a Zhdanov or Jiang Qing, with who knowswh<strong>at</strong> terrible implic<strong>at</strong>ions? (I can only say th<strong>at</strong> neither of the l<strong>at</strong>ter culture czars wasremotely interested in letting people speak for themselves.) In 1968 Raymond Williams putmy point r<strong>at</strong>her succinctly about the scarcity of voices:in British television, whose vice in thisrespect is sadly not unique:...we see too few faces, hear too few voices, and...these faces andvoices are offered as television dealing with life... Last week'sprogramme about farming steep land was a model of interest and .intelligence, with the, regular interviewers, farmers115

themselves, talking to other farmers and letting the camera seethe ground... The point would then be-th<strong>at</strong>, serious and pleasant asthese men are, we would not want them over the next sevendays, looking over their cues <strong>at</strong> Vietnam, the universities, an aircrash,a strike, Rhodesia, car-sales, a prison escape, cheeseimports, a philosopher, Czechoslovakia, suicides (in O'Connor1989: 42-44).To put it differently, in the 1990s in the United St<strong>at</strong>es we have the practicalopportunity, not least because of the considerable underemployed reserve of talent andexperience in television production, to utilize "the age of mechanical reproducibility" tocommunic<strong>at</strong>e the public's expertise on political m<strong>at</strong>ters (in the sense of "political" definedabove). Benjamin's essay (1936/1970) never specified how reproducibility could beactualized by the workers' movement, aside from pointing to Soviet film experimentswhich though he did not then know it were in the process of being strangled to de<strong>at</strong>h as hewrote. Today, outside the televisual mainstream and also in its many interstices, altern<strong>at</strong>iveproduction and reception are becoming gradually more viable.Let me illustr<strong>at</strong>e my movement aesthetics of the voice—or as Brecht put it, how"interests [have been made] interesting" (1930/1983: 171)-from a series of recent politicalvideos.116