Download PDF - The Poetry Project

Download PDF - The Poetry Project

Download PDF - The Poetry Project

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

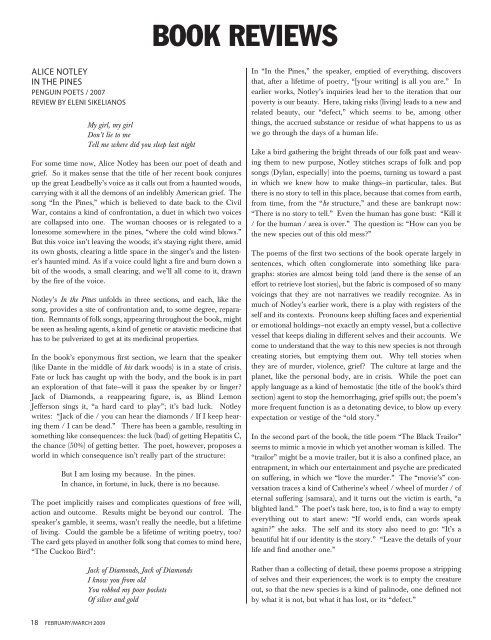

BOOK REVIEWSALICE NOTLEYIN THE PINESPENGUIN POETS / 2007Review by ELENI SIKELIANOSMy girl, my girlDon’t lie to meTell me where did you sleep last nightFor some time now, Alice Notley has been our poet of death andgrief. So it makes sense that the title of her recent book conjuresup the great Leadbelly’s voice as it calls out from a haunted woods,carrying with it all the demons of an indelibly American grief. <strong>The</strong>song “In the Pines,” which is believed to date back to the CivilWar, contains a kind of confrontation, a duet in which two voicesare collapsed into one. <strong>The</strong> woman chooses or is relegated to alonesome somewhere in the pines, “where the cold wind blows.”But this voice isn’t leaving the woods; it’s staying right there, amidits own ghosts, clearing a little space in the singer’s and the listener’shaunted mind. As if a voice could light a fire and burn down abit of the woods, a small clearing, and we’ll all come to it, drawnby the fire of the voice.Notley’s In the Pines unfolds in three sections, and each, like thesong, provides a site of confrontation and, to some degree, reparation.Remnants of folk songs, appearing throughout the book, mightbe seen as healing agents, a kind of genetic or atavistic medicine thathas to be pulverized to get at its medicinal properties.In the book’s eponymous first section, we learn that the speaker(like Dante in the middle of his dark woods) is in a state of crisis.Fate or luck has caught up with the body, and the book is in partan exploration of that fate—will it pass the speaker by or linger?Jack of Diamonds, a reappearing figure, is, as Blind LemonJefferson sings it, “a hard card to play”; it’s bad luck. Notleywrites: “Jack of die / you can hear the diamonds / If I keep hearingthem / I can be dead.” <strong>The</strong>re has been a gamble, resulting insomething like consequences: the luck (bad) of getting Hepatitis C,the chance (50%) of getting better. <strong>The</strong> poet, however, proposes aworld in which consequence isn’t really part of the structure:But I am losing my because. In the pines.In chance, in fortune, in luck, there is no because.<strong>The</strong> poet implicitly raises and complicates questions of free will,action and outcome. Results might be beyond our control. <strong>The</strong>speaker’s gamble, it seems, wasn’t really the needle, but a lifetimeof living. Could the gamble be a lifetime of writing poetry, too?<strong>The</strong> card gets played in another folk song that comes to mind here,“<strong>The</strong> Cuckoo Bird”:Jack of Diamonds, Jack of DiamondsI know you from oldYou robbed my poor pocketsOf silver and goldIn “In the Pines,” the speaker, emptied of everything, discoversthat, after a lifetime of poetry, “[your writing] is all you are.” Inearlier works, Notley’s inquiries lead her to the iteration that ourpoverty is our beauty. Here, taking risks (living) leads to a new andrelated beauty, our “defect,” which seems to be, among otherthings, the accrued substance or residue of what happens to us aswe go through the days of a human life.Like a bird gathering the bright threads of our folk past and weavingthem to new purpose, Notley stitches scraps of folk and popsongs (Dylan, especially) into the poems, turning us toward a pastin which we knew how to make things—in particular, tales. Butthere is no story to tell in this place, because that comes from earth,from time, from the “he structure,” and these are bankrupt now:“<strong>The</strong>re is no story to tell.” Even the human has gone bust: “Kill it/ for the human / area is over.” <strong>The</strong> question is: “How can you bethe new species out of this old mess?”<strong>The</strong> poems of the first two sections of the book operate largely insentences, which often conglomerate into something like paragraphs:stories are almost being told (and there is the sense of aneffort to retrieve lost stories), but the fabric is composed of so manyvoicings that they are not narratives we readily recognize. As inmuch of Notley’s earlier work, there is a play with registers of theself and its contexts. Pronouns keep shifting faces and experientialor emotional holdings—not exactly an empty vessel, but a collectivevessel that keeps dialing in different selves and their accounts. Wecome to understand that the way to this new species is not throughcreating stories, but emptying them out. Why tell stories whenthey are of murder, violence, grief? <strong>The</strong> culture at large and theplanet, like the personal body, are in crisis. While the poet canapply language as a kind of hemostatic (the title of the book’s thirdsection) agent to stop the hemorrhaging, grief spills out; the poem’smore frequent function is as a detonating device, to blow up everyexpectation or vestige of the “old story.”In the second part of the book, the title poem “<strong>The</strong> Black Trailor”seems to mimic a movie in which yet another woman is killed. <strong>The</strong>“trailor” might be a movie trailer, but it is also a confined place, anentrapment, in which our entertainment and psyche are predicatedon suffering, in which we “love the murder.” <strong>The</strong> “movie’s” conversationtraces a kind of Catherine’s wheel / wheel of murder / ofeternal suffering (samsara), and it turns out the victim is earth, “ablighted land.” <strong>The</strong> poet’s task here, too, is to find a way to emptyeverything out to start anew: “If world ends, can words speakagain?” she asks. <strong>The</strong> self and its story also need to go: “It’s abeautiful hit if our identity is the story.” “Leave the details of yourlife and find another one.”Rather than a collecting of detail, these poems propose a strippingof selves and their experiences; the work is to empty the creatureout, so that the new species is a kind of palinode, one defined notby what it is not, but what it has lost, or its “defect.”18 february/march 2009