history_yorkhill_1882-2015

history_yorkhill_1882-2015

history_yorkhill_1882-2015

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

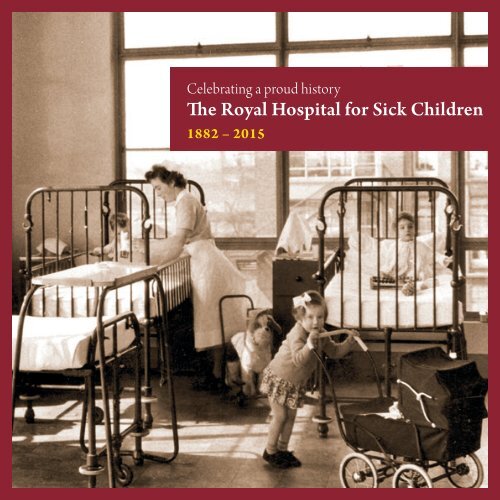

Celebrating a proud <strong>history</strong>The Royal Hospital for Sick Children<strong>1882</strong> – <strong>2015</strong>

Growing demand for servicesThe Drumchapel‘Country branch’opened in 1903.Surgical greatsIn 1889 the hospital receivedpermission to add ‘Royal’ to its titleand received visits from royal visitorsPrincess Louise, daughter of QueenVictoria and later from her eldersister Princess Christianof Schleswig-Holsten.The number of admissions steadily roseand the proportion of surgical patientsincreased. By the late 19th centurythere were more patients admitted bysurgeons than by physicians, and moreseen at the dispensary by surgeonsthan physicians – a pattern which hascontinued. The mortality in surgicalpatients was significantly lower thanthat in the medical wards, no doubtrelated to the diseases present atthe time.The demand for the services was muchgreater than the established situationcould sustain. An extension providinga further 12 cots was provided in 1887when Chairman Thomas Carlilepersonally funded the purchase of thenext-door house in Buccleuch Street.The following year, the Board openeda dispensary in West Graham Street,which functioned until 1954. In itsfirst year it dealt with just over 16,000patients. By the end of the 19th century– it was almost 25,000 and by 1933 itwas more than 100,000.The out- patient facilities fromthis dispensary became knowninternationally, thanks in the main tothe work between 1894 and 1914 ofvisiting surgeon James Nicoll, one ofthe country’s greatest. He pioneeredwork in many fields, notably brain andabdominal surgery and it was at WestGraham Street that many of his radicalideas were put into practice.He was also Professor of Surgery at theAnderson College, had an extensiveprivate practice, and he presentedmany papers at meetings. His lastingcontribution has been emphasisedby the increasing drive to, andpopularity of, day surgery, and thishas been highlighted many timesover the last few decades.An indication of the extent of hissurgical contribution is recorded inthe period 1899 to 1901, when heperformed 460 operations on hare-lipand cleft-palate; over a 10 year periodat that time, he operated upon morethan 7000 patients in the West GrahamStreet Dispensary.After the establishment of thedispensary in 1888, the next majordevelopment was the opening of acountry branch in 1903, with 96 beds.This was in addition to the 76 bedsat Garnethill. This new Drumchapelfacility was to provide a ‘healthier’environment for the children who hadreached the convalescent stage and didnot require the acute services providedat Garnethill.The new facility also boasted a rooftopsun lounge where children wouldbenefit from fresh air and sunshine.The children at Drumchapel enjoyed anoutdoor sun lounge on the balcony.The Drumchapel facility in the 1930’s.The early 20th century wasindeed an era of brilliantScottish surgeons and Sir WilliamMacewen was perhaps the finestof them all. He served the hospitalfor over a decade before movingto become Professor of Surgeryat the Western Infirmary.He developed many aspects ofsurgery in the post-Lister era,and ultimately became knownas the father of neurosurgery.His international standing wassuch that he was invited to becomeHead of Surgery in Baltimore,USA, but declined the invitation.He was followed in his positionin 1894 by Thomas KennedyDalziel, who, through his work atthe Royal Infirmary, recognisedand reported on chronicinterstitial enteritis. Some 30years later Crohn was to describethis same entity again and thedisease is generally known asCrohn’s Disease.8 9Fun on the lawn at Drumchapel.

The move to treat infantsSurgeon Thomas Kennedy Dalzielwas to clash with the board over theadmission of children under the ageof two. In 1901 the board instructedmedical chiefs to keep the numbersas low as possible but Dalzielopposed them with the response:“I think it would be better to admitfewer aged between six and twelveand take in more under two years– that is, if the hospital is to fulfila real want”.The board relented and by 1914 athird of all patients were under two.Infant mortality at the beginning ofthe 20th century had not yet begunto mirror the general reduction indeath rates, for despite improvementsin sanitation, housing conditions hadnot improved much, if at all in thepreceding 50 years.Neither had the conduct of somemothers, who neglected to feed orcare properly for their infants, oftendue to alcoholism.These conditions were vividly andperceptively described by one of thehospital’s directors – Dr James B.Russell – who as Glasgow’s secondmedical officer of health hadsuccessfully guided the late-Victoriansanitary reforms. He was nodesk-bound administrator; hiswork took him out to the slums andin 1886 he wrote an account of lifein Glasgow’s single-ends. It containedthe poignant description of one visit:“On your last visit you saw a childvery ill and this time you see themother huddled up on top of herbed sleeping in a drunken sleep,and you know the child is dead.They baptise with whisky and theybury with whisky”.If alcohol was the source of infantmortality then so was milk. Manymothers did not breastfeed andresorted to the use of adulteratedmilk, often containing high levelsof boracic acid. Poor milk causedtuberculosis and infantile diarrhoea– so prevalent it was known as thesummer plague.In 1904 the establishment of aGlasgow Infant Milk Depot withadvisory services went some wayto addressing the problem.Infant mortality under threemonths continued to be a problemand education of mothers becamean important element of thehospital’s objectives.In 1910 physician Barclay Nessnoted that by far the most commoncause of illness was the ignoranceof the mother. It was only by teachingher to care for, feed and bring up herchildren properly that any real andlasting benefit could be conferredon the children.10 11

The day the soldiers marched to the dispensaryA group of probationer nurses in 1917.On the move to YorkhillThe drive towards better public healthwas, strangely, partly prompted by thenumber of volunteers for the Boer Warwho were turned down on the groundsof being unfit through ill health.The first annual inspection of schoolchildren in Glasgow took place in1904 and it was found that morethan half of those deemedunfit had never seen a doctor.The remedy for such a problem wassocial rather than medical but as plansfor a new hospital at Yorkhill tookshape, the day was coming whenGlasgow would play a pioneering rolein the treatment of children’s diseases.By the early 20th century it hadbecome clear that the hospital had12outgrown its Garnethill building.Just over 70 cots could not cope witha population of almost two million inGlasgow and the west of Scotland.By 1907 there were always between100 and 200 patients on thetwo-month waiting list.An appeal for £100,000 was launchedand after inspecting a number ofpotential sites the board purchaseda 19 acre site containing “the bestand highest parts of the landsof Yorkhill” for £16,000.Among many city architect firmsbidding to design the new building wasCharles Rennie Mackintosh’s, but hewas to be rejected in favour of theAn early ambulance outside the new hospital at Yorkhill.father and son firm of John JamesBurnet. Between them they designeda number of great buildings in the cityincluding the Clydesdale Bank onSt Vincent Street, Cleveden Terrace,the Academy of Music and theWestern Infirmary.Burnet and his team toured Europe,particularly Germany, in search of themost modern ideas in hospital designand settled on the pavilion system,with widely spaced ward blocks linkedby broad corridors, maximising lightand air. There were 12 wards with312 cots and two operating theatres.The cost £140,000 – was more than tentimes its predecessor at Garnethill.The new Royal Hospital for SickChildren (RHSC) was opened inJuly 1914, weeks before the outbreakof war, by King George V and QueenMary. A crowd of 10,000 attendedthe opening including the usualdignitaries, Boy Scouts, Guides,and even the builders were affordeda grandstand of their own.Just four weeks after the openingceremony World War One beganand it was to be four years before theRHSC would be fully functionalas a children’s hospital.Instead, the military authoritiescommandeered four wards forthe treatment of army and navalofficers. Bearing in mind the hospitalhad been designed for children thisnecessitated the purchase of biggerbeds, mattresses and blanketsand also alterations to the sizeof the toilets!On one occasion in 1916advance news of a Zeppelin raidprompted staff to hurriedly evacuatethe children to the basement but intheir rush they forgot to label them.When the all clear sounded and theyreturned to the wards many of themhad to be re-diagnosed. The militaryoccupation of the Dispensary wasmuch shorter. One day soldiers fromMaryhill barracks were marcheddown to West Graham Street andafter a short interval marched backminus their tonsils.Peace was declared in late 1918 but itwas several years before the militaryoccupation ended and the hospitalcould revert to its intended use forthe sole treatment of children.Passing the time on one of the old wards.Crowds at RHSC wait to greet the King andQueen on their visit to Glasgow in 1927.13

One of the operating theatres in the 1920s.The fathers of paediatricsWith its up-to-date design andequipment the hospital now forgedlinks with Glasgow University, pavingthe way for medical students to receivelectures and eventually becomepaediatric specialists.By the 1920s Yorkhill could boastone of the UK’s leading teams ofscientific workers, working on anumber of innovations in paediatricmedicine. The array of eminentsurgeons and physicians now plyingtheir trade at Yorkhill ensured that thehospital’s reputation continued to grow.Chief amongst them was the fieryLeonard Findlay, distinguished in bothappearance and reputation, he and JohnThomson of Edinburgh areregarded as the founders ofpaediatrics in Scotland.He realised theimportance ofcombining laboratorywork with clinical workand he gathered a teamof assistants fromacross the globe andencouraged them tomake full use ofpathological andbiochemical methods inthe clinical study of theiryoung patients.Generous GlasgowInflation and much needed newdevelopments placed pressure on thehospital’s finances after the war and in1924 an appeal was launched to raise£75,000, including a radio broadcastfrom the newly opened BBC studioin Bath Street. The money was raisedwithin four months, allowing work togo ahead on two new wings and anextension to the Drumchapel facility.At every step of the way from itsinception at Garnethill in <strong>1882</strong>, Yorkhillin 1914 right up to the creation of theNHS in 1948 the Royal Hospital forSick Children relied on voluntarysubscriptions and donations to fundbuildings, equipment and staff.The affection for the RHSC inPrincess Mary visits in 1930.the hearts of Glaswegians and peoplefrom the West of Scotland has notdimmed since that time. For more than130 years the public’s generosity hasensured that the children at the RHSChave received the highest standard ofmedical and social care.14 15

Men of CharacterTribute to nursesK Leonard Findlay was followedin his role by Geoffrey Fleming,a pioneer in the work onmetabolism. He was a keenhuntsman and on occasionhe would conduct his roundswearing his pink hunting coatbefore setting off to follow thehounds with the Lanarkshire andRenfrewshire Hunt. He was alsoa keen angler and he often sharedthe fruits of his labours withmembers of staff.Paediatric surgery, likemedicine, was making greatstrides at the Royal Hospitalfor Sick Children, thanks inthe main to names likeAlexander MacLennan,William Rankin andMatthew White.MacLennan is one of theoutstanding figures in theRHSC’s <strong>history</strong>. For most of theinter-war period he was Barclaylecturer and senior surgeon atthe hospital and was renownedfor his pioneering clinics, his defttouch with the scalpel and thedevelopment of many ingeniousdevices which he applied to hiswork. He set up one of the firstsplint departments in theUK at the RHSC.Matthew White wasMacLennan’s colleague in the30s and succeeded him in theBarclay lectureship from 1939to 1953. His first experience ofthe RHSC had been as a patientthere in 1916 during the war.Often described as the doyenof children’s surgery, Whitepublished works on almostevery branch of paediatricsurgery and was the authorof the first undergraduatetextbook in English.A graduate in Greek, Zoologyand Philosophy, White had apassion for speed and in 1933he learned to fly and was knownto swoop low over the roof ofthe hospital in his Gypsy Moth,much to the concern of his housesurgeons basking in the sunshineon the roof.Other members of staff werealso to rise to fame, includingdispensary physician Dr O.H.Mavor, better known asdramatist James Bridie.This period in the hospitals<strong>history</strong> also saw the emergenceof a number of women inimportant roles, includingDr Agnes Cameron and Dr MaryStevenson, assistants to LeonardFindlay, and Dr ElaineStocquart, for many yearssenior anaesthetist.By the 1930s clinics for thetreatment of former patientshad also been set up,including diabetics, chest, renaland speech. Research continuedto forge ahead under medicalchiefs Geoffrey Fleming andStanley Graham, supported inthe biochemistry laboratory byNoah Morris and in pathologyby John Blacklock.Despite these many advances,there was still little effectivetreatment for many severeinfections, including pneumonia,tuberculosis and gastroenteritis.The conquest of these diseaseswould have to await thedevelopment of modern drugsafter the Second World War.Records show that operationsperformed in 1937 totalled5000, many of them for burns,scalds and fractures, the latterbecoming increasingly commonthanks to the growth of the useof the motor car.Christmas on the ward in 1932.By the year of the hospital’s goldenjubilee in 1932, the role and theworking conditions of the nursingstaff had also undergone huge change.The establishment in 1919 of theGeneral Nursing Council led to athree-year training curriculum, thecramped nurses’ quarters had beenreplaced by custom builtaccommodation on the top floor,including recreation, lecture andsitting rooms.There was now no shortage of womenwishing to join the nursing profession.In 1932 the RHSC received 777applications.This period, as ever, produced manytalented and formidable nursinglegends including Matrons MaryCameron and Miss M. OliviaRobinson, and Sisters Jane Turnbulland Isobel Neilson.16 17

The war and the coming of the NHSThe Queen Mum’sWhen war came in 1939, the RoyalHospital for Sick Children wasto remain civilian, but still work washampered by the day-to-day black-outs,coal shortages and water problems.As in the earlier war, many doctors wereabsent on military service, their absenceplacing a strain on those who remained.In 1944 a serious outbreak ofgastroenteritis raised the alreadyscandalous infant mortality rate.Of 17 European countries Scotlandhad the highest rate, 77 per 1000, andGlasgow’s was the highest in Britain,57% higher than Birmingham. Theannual report stated: “The panacea canbe stated in two words – good homes– in the fullest sense of the term.”On July 5, 1948, the RHSC like all theother major hospitals in Glasgow,became part of the new National HealthService. Despite initial reservationsover the retention of endowment funds,the hospital was soon to embark on aperiod of the most rapid and remarkableadvances in its <strong>history</strong>.The development of antibiotic drugs(penicillin was first used at the RHSCin 1944) began to conquer many of theformer deadly diseases. It also allowedsurgeons to more safely undertake alarge number of major operations.The post war years saw the work ofeminent surgeons and physicians likeJames Hutchison, Andrew Laird,Wallace Dennison, Sam Davidson,John Bentley, Dan Young, Ellis Wilson,Noel Buckley and Robert Shanks furtherimproved treatments for children andthe reputation of the RHSC as a centreof excellence.Of immense significance to the RHSCwas the opening in 1964 of the QueenMother’s Maternity Hospital on the siteof the old staff hockey pitch.Then, in 1966, the hospital wastemporarily relocated to the formerOakbank Hospital buildings inMaryhill in order to facilitate thedemolition of the existing building,which was discovered to be sufferingfrom severe structural defects.The new Queen Mother’sMaternity Hospital opensin 1964.Nurses Station, the Queen Mums 1964.The building in the 1930s.The nurses’ sitting room in the 50s.The Queen Mother visits in 1964.18 19

Building for the futureAlways growingThe new RHSC in 1972.Moving patients back from Oakbank to the new hospital in October 1971.The new Royal Hospital for SickChildren building was reopenedat a cost of £5.7million at Yorkhillby Queen Elizabeth II in 1972 andcoupled with the Queen Mother’sMaternity Hospital, effectivelyestablished a national centre ofintegrated obstetrics andpaediatric healthcare.It took just 48 hours to completethe transfer of all the patients fromOakbank to the new hospital.The progress in almost everyaspect of paediatrics, obstetricsand orthopaedics has continuedabreast for the past 50 years sincethat Royal occasion.The Royal visit in 1972.A new operating theatre complexopened in 1998 and a new IntensiveCare Unit opened in April 2005.Prior to its move to the new SouthGlasgow site, the RHSC handledapproximately 90,000 out-patients,15,000 in-patients and 7,300 daycases every year.Its list of services are almost endlessbut amongst them are Accident andEmergency, Audiology Department,Biochemistry, Cardiac Clinics, DaySurgery Unit and many more.Many sick children spend days,months and years attending thehospital, some with minor ailmentsand some fighting for their lives.Yorkhill Children’s Charity workstirelessly doing all that it can to makethese difficult times easier for thechildren and their families, helpingto give them the best chance ofmaking a full recovery. Its fundraisingefforts attract support fromthroughout Scotland and ofteninvolve stars of sport, entertainmentand politics, such is the warmth offeeling and admiration the hospitalattracts. Fundraising income for thegroup has grown steadily sinceits inception, raising £319,000 in2001 (7 months) to £4.3 millionin 2013-14.The new A&E unit opened in 1995.Rangers legend John Brown joins Kilsythworkers Alan Kerr and Paul Lochrie topresent a cheque towards the RHSCScanner Appeal in 1997.2021

Introducing the new South Glasgow hospitalsThe Royal Hospital for Sick ChildrenSame wonderful care in bright new hi-tech surroundingsWhen the new Royal Hospital forSick Children opens its doors on10th June, you can be assuredthat your child will get the samewonderful care that they havealways had at Yorkhill. The stafffrom the world renownedhospital will be the same butthe key difference will be thefabulous new facilities that theyand your child will experience.The hospital was designed around theneeds of children...and who better togive us that insight than existing patients.Working together with architects, nurses,doctors and other clinical staff, our youngpatients have helped create a hospital thatis truly outstanding.Here we spotlight just a few of the strikingfeatures of this new jewel in the crown ofpaediatric hospitals.Age appropriate careUntil now, children from the age of 13 weretypically cared for in our adult hospitals.The new hospital is designed to treat allpatients until they turn 16, providing a muchmore appropriate setting for these youngpeople. There’s also a base for adolescents toplay games consoles, make a snack or chill withfriends or visitors.PlayPlay is an important element of a child’s timein hospital. An outdoor play area at the entranceto the hospital has disabled accessibleinstallations. Play specialists are based in theindoor play zone area to work with childrenahead of treatment. There’s also a part-coveredroof garden where young patients can enjoya range of activities in the fresh air and forchildren to be brought out to the roof gardenin their beds.Modern rooms for modern childrenThe vast majority of the 244 paediatric bedsare in single rooms with their own toilet andshower facilities and entertainment consolesystem, including TV and Wi-Fi. The roomsare spacious and designed to enable a parentor guardian to stay overnight with their child.There are a small number of four beddedwards for those patients who would benefitfrom social interaction with other children...these were created in response to feedbackfrom children, parents and experiencedpaediatric healthcare staff.Attention to detailEvery little thing has been given bigattention, down to the creation of speciallydesigned doors with viewing windows atdifferent eye levels that will ensure that eventhe tiniest tot has the same opportunity to seein and out of the room. The artwork has evenbeen installed into ceilings to let young patientson trolleys to see something bright and cheerfulwhen they’re being moved around. The brightreception desk is decorated by a bank of lightsthat constantly change colour.South Glasgow University HospitalDespite its size, this hugehospital has been designed tomake it very easy for you to getto your destination.From the hi-tech touch screeninformation points and thebarcode self check-in to thefriendly faces of our guidingvolunteers and landmarkartworks at key pointsthroughout the hospital…everything is geared towardsmaking it simple to get around.Science CentreTo entertain children whilst they wait for theiroutpatient appointment, the hospital has beenfitted out with an array of interactive activitiesprovided by the Glasgow Science Centre andfunded by Yorkhill Children’s Charity. Theseinnovative “distraction therapy” installationsprovide a range of hi and low tech approachesthat will delight young patients or their siblingsduring any visit to the hospital.CinemaA 48 seater cinema has been speciallycreated in the new hospital to provide firstclass entertainment to our young patientsduring their stay with us.Outpatient check-inIf you are attending as an outpatient you cancheck-in using the letter we sent you whenyou arrive – just like at the airport. Scan inyour hospital letter at one of the scanningcheck-in points, confirm your details andyou’ll be shown where to go next. It’s areally easy system to use but if you preferone of our friendly volunteers will be happyto help. When you arrive at your outpatientwaiting room, keep an eye on the screen– it will call you to your clinic room.Room with a viewThe hospital has 1,109 beds – all withtheir own toilet and shower facilities.Every room in our general wards has apanoramic external view and comes withfree TV and radio. There’s even free patientWi-Fi access throughout the hospital.Every room is designed to the highestspecification to reduce the risk of thespread of infection and provide safeand comfortable surroundings,including an electric bed as standard.Food and drinkNext to the restaurant on the first floorof the atrium is the Aroma Coffee shop.This is opened Monday through to Fridayfrom 9.00am until 6.30pm serving highquality beverages, sandwiches, snacks,fruit and cakes.Both the restaurant and the coffee shopare run by NHS staff and all profits go backinto the NHS.ArtThe colour scheme of the hospital hasbeen deliberately designed to help you findyour way around. Each floor has a clearlyidentifiable colour and many works ofdistinctive art are displayed to give usefullandmarks which can act as signposts.The use of therapeutic colour schemesthroughout the hospital has been carefullyselected by interior design specialiststo soothe, reduce stress and enhancewell being.RetailAs you would expect, in an ultra-modernhospital of this size there are a numberof commercial retail outlets for patients,visitors and staff alike. The retail outletsare all located on the ground floor in theatrium and include: Marks & Spencer;W H Smith; Camden Food co; and, SoupedUp & Juiced. There are also bank cashmachines located in the hospital.Lift systemThere are four wards on each level: A, B, C and D.Wards A and B are accessed by the liftssignposted as Arran on the ground floor; andwards C and D are accessed by the lifts signpostedas Bute.These lifts use smart technology to get you tothe ward you want as quickly as possible.You press the button panel outside the lift and itwill direct you to the best lift for you. All you needto do next is to get inside the lift and it will takeyou to the correct floor. There are no buttonsinside the lift.22

Getting thereThe new South Glasgow hospitals are easy to get to. They arelocated just a few minutes from the M8, within a few hundredyards of the Clyde Tunnel and served by a very frequent andfast bus link network.There are on site multi-storey car parks and ground level spaces for patients andvisitors. Car parking is free but there is a four-hour maximum stay between Monday toFriday 7.30am till 4pm. Disabled parking spaces are available on the ground floor of themulti-storey car parks.The new Fastlink bus route provides speedy links from Glasgow City Centre via theArc Bridge (known sometimes as the Squinty Bridge). At peak times there will be abus every minute arriving at or inside the hospitals campus.You can reach the direct bus link network via the city’s excellent rail and subwaytransport systems.Find out about the best routes for your journey call traveline on:0871 200 22 33 Or visit: www.travelinescotland.comA new dedicated section of the traveline website has been created giving you information on ticket options with linksto major bus operators and SPT as well as a link to a hospital journey planner. Simply click on the button “New SouthGlasgow Hospitals” on the homepage for all you need to know about getting to the hospital by public transport.Fastlink route

Created and designed by NHSGGCCorporate Communications Team.With special thanks for permissionto use archive images:Newsquest – publishers of the Herald& Evening TimesGlasgow City ArchivesGlasgow Caledonian University Archives