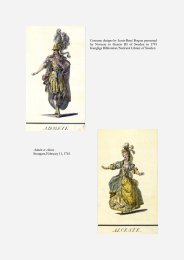

AAR <strong>Act<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Archives</strong> Essays Supplement 1 – April 2011was closely l<strong>in</strong>ked with a new requirement, that of present<strong>in</strong>g rigorously andconv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>gly <strong>the</strong> precise image of a particular character.In fourth-century <strong>the</strong>ory, <strong>the</strong> character – its function <strong>in</strong> poetic composition and<strong>the</strong> significance of its presence <strong>in</strong> mak<strong>in</strong>g a work – had gradually become <strong>the</strong>dist<strong>in</strong>ctive element of <strong>the</strong>atrical dramatic form. In <strong>the</strong> Republic Plato traced <strong>the</strong>difference between ‘simple’ poetry and ‘imitative’ poetry, observ<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>former <strong>the</strong> poet spoke ‘<strong>in</strong> his own person’, while <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> latter he reported <strong>the</strong>discourse ‘as if he were someone else’, and <strong>in</strong> this way suited ‘his own words to thoseof <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual character’ as far as possible. And, he concluded, <strong>the</strong> form of thispoetry is that ‘of tragedy and comedy’. 37 Aristotle later established <strong>the</strong> famousdist<strong>in</strong>ction between ‘narrative’ or ‘epic’ poetry and ‘dramatic’ poetry, expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g that<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> latter it is <strong>the</strong> actors who directly represent <strong>the</strong> whole action ‘as if <strong>the</strong>y were<strong>the</strong>mselves <strong>the</strong> characters who lived and acted’. 38It is <strong>the</strong> presence of <strong>the</strong> character, <strong>the</strong>n, <strong>the</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g motor force of <strong>the</strong> action, thatconstitutes <strong>the</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>ctive element of dramatic form. If, however, <strong>the</strong> character is toseem conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g and effective onstage, he needs an <strong>in</strong>dispensable quality: anunderly<strong>in</strong>g ‘coherence’ <strong>in</strong> his essential nature, <strong>the</strong> passions that agitate him, and <strong>the</strong>actions he performs. He cannot feel passions that are ‘out-of-character’, or showmoral qualities that have noth<strong>in</strong>g to do with <strong>the</strong> actions <strong>in</strong> which he is <strong>in</strong>volved, orperform actions that seem improbable for a person of his k<strong>in</strong>d. As Aristotle expla<strong>in</strong>s:given, for example, someone with a character of this or that k<strong>in</strong>d, what he says or doesshould seem to emerge from his character <strong>in</strong> accordance with <strong>the</strong> laws of truth andverisimilitude. 39The figures <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> drama were, <strong>the</strong>n, a rigorously pre-arranged comb<strong>in</strong>ation ofcharacter, passions and actions. The different forms this comb<strong>in</strong>ation could takewere codified, and this def<strong>in</strong>ed a sort of gallery of figures, or a typology of exemplaryprofiles of various k<strong>in</strong>ds of humanity, identified by generational, social, economic ormoral categories. The typology was widespread <strong>in</strong> treatises on rhetoric or ethics.Aristotle’s Rhetoric, for example, dist<strong>in</strong>guished <strong>the</strong> categories of <strong>the</strong> ‘young’, ‘maturepersons’, and <strong>the</strong> ‘old’, or <strong>the</strong> ‘rich’, <strong>the</strong> ‘powerful’ or <strong>the</strong> ‘unfortunate’. Each of <strong>the</strong>sefigures was assigned specific forms of passion and behaviour. 40Thus, <strong>in</strong> a perspective of this k<strong>in</strong>d, each <strong>the</strong>atrical character had to correspond to<strong>the</strong> parameters of an established typology, and, to render him adequately on stage,<strong>the</strong> actor had to reproduce precisely his expected passions and behaviour, avoid<strong>in</strong>gattitudes or ways of behav<strong>in</strong>g that might clash with <strong>the</strong> accepted code. It wasabsolutely wrong, Aristotle <strong>in</strong>sisted, for example, to represent ladies of <strong>the</strong> nobility asif <strong>the</strong>y were loose women, or, observed Lucian, bold heroes with a languid andeffem<strong>in</strong>ate gait. 4137 Plato, Republic, III,393a-c and 394c.38 Aristotle, Poetics, 1448a.39 Ibid., 1454a.40 Aristotle, Rhetoric, 1388b-1391b. The typology of characters, def<strong>in</strong>ed by social, generational andmoral categories, is also reflected <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> form of <strong>the</strong> masks. On this see <strong>the</strong> list of masks described <strong>in</strong>Iulius Pollux, Onomasticon, IV,133-154.41 See Aristotle, Poetics, 1462a, and Lucian, The Fisherman, 31.10

<strong>Claudio</strong> <strong>Vicent<strong>in</strong>i</strong>, <strong>Act<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Theory</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Ancient</strong> <strong>World</strong>5. The New Form of Emotional InvolvementRepresent<strong>in</strong>g characters and display<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir passions and attitudes was, <strong>the</strong>n, <strong>the</strong>actor’s fundamental task. But to really depict a character <strong>in</strong> action it was not enoughto coldly put toge<strong>the</strong>r a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of features that fitted toge<strong>the</strong>r with each o<strong>the</strong>r.A simple comb<strong>in</strong>ation of <strong>the</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d would have seemed <strong>in</strong>ert and unconv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g. Toanimate it, <strong>the</strong> artist had to really feel, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> act of creation, <strong>the</strong> passions experiencedby <strong>the</strong> character.This rule, accord<strong>in</strong>g to Aristotle’s Poetics, concerned <strong>the</strong> poets above all:<strong>the</strong> most persuasive poets are those that start from <strong>the</strong> same state of m<strong>in</strong>d as <strong>the</strong>ircharacters, and experience each time <strong>the</strong> very passions <strong>the</strong>y <strong>in</strong>tend to depict: so that, forexample, one whose soul is <strong>in</strong> turmoil will succeed <strong>in</strong> represent<strong>in</strong>g a soul <strong>in</strong> turmoilwith much greater truth, one who feels angry a soul <strong>in</strong> anger. 42It was an op<strong>in</strong>ion that had been widespread <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Greek world for some time.Eighty years before, Aristophanes had already used it satirically <strong>in</strong> a comedy, <strong>the</strong>Thesmophoriazusae, <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> poet Agathon, whose homosexual tastes were wellknown, appeared, stretched out languidly on a bed, clad <strong>in</strong> female cloth<strong>in</strong>g andsurrounded by elegant toilet articles. He expla<strong>in</strong>ed that he had to behave like this forpurely professional reasons, claim<strong>in</strong>g that no poet could write his plays if he did notassume <strong>the</strong> manners of his characters. To depict <strong>the</strong> female figures effectively he<strong>the</strong>refore had to adopt all <strong>the</strong>ir ways and costumes.Thus Greek culture from <strong>the</strong> late fifth century BCE reveals a new way ofunderstand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> artist’s emotional <strong>in</strong>volvement at <strong>the</strong> moment of creation.Alongside <strong>the</strong> archaic way, which <strong>the</strong>orized div<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>tervention able to produce astate of halluc<strong>in</strong>ated and uncontrollable frenzy, <strong>the</strong>re was a more recent conception,<strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> artist’s participation consisted <strong>in</strong> his capacity to reproduce <strong>in</strong> himself arange of passions that ra<strong>the</strong>r than be<strong>in</strong>g ‘extreme’ and ‘disruptive’, were precise andcarefully def<strong>in</strong>ed, follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dications dictated by <strong>the</strong> type of character.Given this premise, <strong>the</strong>n clearly <strong>the</strong> actor could do noth<strong>in</strong>g onstage withoutbr<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g his own <strong>in</strong>ner self <strong>in</strong>to play. To represent <strong>the</strong> character he must really feel itspassions, and only <strong>in</strong> this way can he effectively render its attitudes and expressions.This is a carefully controlled and moderate emotional <strong>in</strong>volvement however: <strong>the</strong>actor uses his own <strong>in</strong>terior tension exclusively to render, with voice and gesture, predeterm<strong>in</strong>edexpressive attitudes that are rigorously coherent with <strong>the</strong> figure to berepresented.On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, <strong>the</strong> control that <strong>the</strong> actor must exercise over his feel<strong>in</strong>gs by nomeans limits <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tensity of <strong>the</strong> emotional effect of his performance on <strong>the</strong>audience, which is led to suffer, despair or delight as it follows <strong>the</strong> vicissitudes of <strong>the</strong>characters onstage. The ability to unleash <strong>the</strong> audience’s passions rema<strong>in</strong>ed, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>op<strong>in</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> time, <strong>the</strong> fundamental criterion for evaluat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> mastery of aperformer, and it was not for noth<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> most famous actors cont<strong>in</strong>ued toboast of <strong>the</strong>ir ability to make <strong>the</strong> audience weep unrestra<strong>in</strong>edly. 43 But <strong>the</strong> audience’s<strong>in</strong>volvement no longer happened through a mysterious contagion of div<strong>in</strong>e orig<strong>in</strong>. Itwas <strong>the</strong> simple result of a wholly natural process, already described by Plato, by42 Aristotle, Poetics, 1455a.43 See Xenophon, Symposium, III,11.11

- Page 1 and 2: Claudio VicentiniTHEORY OF ACTINGIA

- Page 3 and 4: Claudio Vicentini, Acting Theory in

- Page 5 and 6: Claudio Vicentini, Acting Theory in

- Page 7 and 8: Claudio Vicentini, Acting Theory in

- Page 9: Claudio Vicentini, Acting Theory in

- Page 13 and 14: Claudio Vicentini, Acting Theory in

- Page 15 and 16: Claudio Vicentini, Acting Theory in

- Page 17 and 18: Claudio Vicentini, Acting Theory in

- Page 19 and 20: Claudio Vicentini, Acting Theory in

- Page 21 and 22: Claudio Vicentini, Acting Theory in

- Page 23 and 24: Claudio Vicentini, Acting Theory in

- Page 25: Claudio Vicentini, Acting Theory in