Women Affected by Gun Violence Speak Out - SEESAC

Women Affected by Gun Violence Speak Out - SEESAC

Women Affected by Gun Violence Speak Out - SEESAC

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

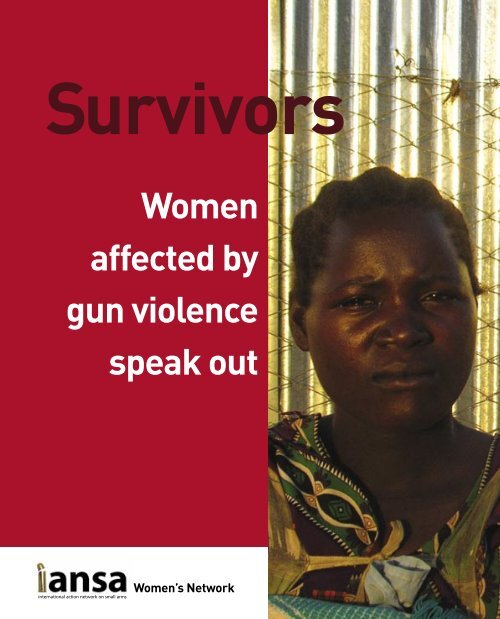

Survivors<strong>Women</strong>affected <strong>by</strong>gun violencespeak outinternational action network on small arms<strong>Women</strong>’s Network

Ambush in BurundiCHANTAL MANANI, BURUNDIAfricaIT WAS 10.30 AM ON 23 MAY 2003, when soldiersfrom the government army fell into an ambushset up <strong>by</strong> rebel combatants from the NationalLiberation Front (FLN) while coming back fromtheir regular patrol in the hills surrounding thevillage of the catholic parish of Mutunba.Chasing the rebels, the soldiers fired severalbullets in the direction where a murder wascommitted, nearly five kilometres away fromour house.The inhabitants of the village becamedisoriented and started looking for a safe place totake refuge. Each familyleft their home with onlytheir most essentialbelongings and headedtowards the local church,the only place they judgedto be safe.My family and I hadjust left our house andwere heading towards thechurch when suddenlytwo soldiers approached us and demanded thatwe go back to the house, where they ordered usto lie down.When I was down on the ground,one of the two soldiers demandedthat I come outside with him. Iobeyed the order and left the house.The soldiers started shooting underthe door to frighten my husband,who remained in the house withmy children and some other peoplethey had rounded up from the area.ONCE I WAS ON MY OWN OUTSIDE,the soldier lead me to a bush behind our toiletsand demanded that I lie down and get undressedor he would shoot me and my husband.With great force, he tore off my underwearand gave me a kick with his foot. I fell naked tothe ground. A few seconds later he was on top ofme and the act was consummated.Then the other soldier who had been insideterrorising the others <strong>by</strong> shooting into the air toldhis friend that it was his turn. He climbed on topof me and performed the same disgusting act.It was truly painful and horrible. I was fourmonths pregnant, and I could not breatheproperly. When the soldier realised that I haddifficulty breathing, he quickly got up andheaded off.A few minutes later, the neighbours pickedme up and took me to the parish clinic. In spiteof the help of the medical staff, I suffered amiscarriage.Word of my story spread quickly throughthe village. Whenever I walked down the street,I knew everyone was talking about me, whichmade me feel wretched.It was truly painful and horrible. I wasfour months pregnant, and I could notbreathe properly. When the soldierrealised that I had difficulty breathing,he quickly got up and headed off.1

AfricaSo many lost to gunsMUTESIA LEWARANI, KENYAMY NAME IS MUTESIA LEWARANI. I am a 40year-old widow. I come from the Baragoi divisionof the Samburu district in Kenya. The Samburudistrict is in the Rift Valley province wherethe marginalised pastoral and semi-pastoralcommunities of Kenya live. Cattle rustling(livestock theft) is a tradition and a way of lifefor these communities. Lately firearms areincreasingly and indiscriminately used inthe process.Competing with neighbouring communitiesover scarce resources such as pastures and waterfor our livestock has made us insecure. In mycommunity, guns have become tools for acquiringand protecting wealth. Small arms are so rife thatan AK47 rifle is often part of a bride price.Cattle rustling has always been a feature ofour lives, but it has escalated over the years dueto the presence of guns inour community. Before I gotmarried, Turkana warriorsraided my village constantly.During one of these raids, allof my father’s livestock wastaken away. My father wasaway during the attack, andso my two mothers raisedthe alarm. I watched as thearmed warriors raped one of my mothers inour shared sleeping quarters. Then both werebrutally shot dead. Although it happened severalyears back, the incident is still very vivid inmy mind.A FEW YEARS LATER, I got married. I was happyto have my own home, healthy children andlivestock. However, peace remained elusive. Myhappiness was cut short <strong>by</strong> a raid from Pokotwarriors on my homestead. My husband’s familylost 100 cattle and 30 goats and sheep in adaylight raid that lasted less than 45 minutes.My husbands’ two brothers who lived with uswere shot dead in the process.Now living in fear, we abandoned our homeand sought refuge in a camp in Maralal, wheredisplaced people like us were hosted. During thistime my husband’s health greatly deteriorated.He died, leaving me the sole breadwinner ofthe family with no property and nothing tocall a home. I decided to leave the camp andreturn to my marital home in Marti. By now, thegovernment had stepped up security and all of usin the villages felt safer. Living with my in-laws, Istruggled to fend for my children.Two of my children were among the childrenfrom the village who were shot dead <strong>by</strong> armedwarriors as they looked after relatives’ livestock.Today as I speak, I am looking after my son’sexpectant wife at the Maralal hospital. She isrecovering from gunshot wounds she sufferedI have lost count of the siblings I have lostto guns. I believe that if the governmentprovides my community with more security,a lot of people will surrender their illegalfirearms.during a raid in early April 2006. I pray that Godsaves her life as she is due to have a ba<strong>by</strong> in onemonth’s time.I have lost count of the siblings I have lost toguns. I believe that if the government providesmy community with more security, a lot of peoplewill surrender their illegal firearms. There arealso very sophisticated weapons being smuggledacross the borders. If security is tightened, wewill have fewer guns coming in.2

Trying to rebuild a lifeKAVIRA ZAWADI, DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGOAfricaONE NIGHT IN MAY 2004 my husband and I weresleeping in our house when we suddenly heardsome people asking us to open the door. It wasaround 3 am. Fearing an attack, we refused. Atthat time, insecurity ruled in our town.After around ten minutes, gunmen forcedthemselves through our flimsy door. They boltedinto our bedroom and warned us not to screamor put on the light. Their torches were the onlylight there was, but I could discern that therewere six men in military uniforms holding guns.The men told my husband that if he didn’t givethem money they would rape me and kill him.<strong>Out</strong> of fear, my husband gave them all of themoney we had in the house – around $300– which we had been saving to buy some land.The cash was not enough to satisfy them,and one of them decided to rape me after tyingup my husband. When I screamed, he startedshooting his gun in the air to deter anyone fromthe surrounding houses to come and rescue us.I viciously bit the gunman who was trying to rapeme. Angered <strong>by</strong> my action, he fired four bulletsinto my chest and another one into my forearm.I was presumed dead since my body lay limpMy arm injury and body scars mademe repellent to my husband. Hedeclared I was an unfit wife since Icould not perform household chores orhave children.on the floor. The men quickly left our house,although not before one fired a bullet into myhusband’s knee while the others shot into the air.I WAS TAKEN TO HOSPITAL, where it wasdiscovered that my fallopian tube was damagedand I had to have my tubes tied.My arm injury and body scars made merepellent to my husband. He declared I was anunfit wife since I could not perform householdchores or have children.Rejected <strong>by</strong> my husband, I am currently livingwithout any livelihood under my parents’ roofwith my elderly mother. My only consolation isa nongovernmental organisation called CREDDwhich provides legal assistance to victims ofsexual violence. The staff arehelping me to convince myhusband to take me back intoour home.3

AfricaAbduction, fear and painJANET AOL, UGANDAI WAS ABDUCTED BY REBELS from the Lord’sResistance Army (LRA) in northern Uganda whenI was seven and forced to fight as a child soldierfor 12 years.When the rebels attacked my village theyshot many villagers in front of me and took meaway from my parents. The rebels took me andsome other children through the bush to the LRAheadquarters in southern Sudan <strong>by</strong> binding uswith rope. It was a long way, but we had to walkthere without saying anything or they threatenedus with a gun. I saw several children killed on theway to Sudan just because they tried to escape.Although 15 years have passed, I cannot forgettheir cries or their faces in death.We abductees were forced to do anythingthe rebels needed or wanted, such as cooking,drawing water, carrying weapons and heavyluggage for long distances without food orwater. The most painful experience that wegirls suffered was rape <strong>by</strong> the commander andforced marriage to adult soldiers. Some girlswere forced to enter into shotgun marriageswith men who were more than ten years older.We had to obey because there was no way toresist men whowere armed withguns. Many girlsand women whorefused or tried toescape were killedor cut with a knifeas punishment. I donot remember howmany times overthose 12 years in the bush I prayed to go back tomy home and parents.I married one of the LRA soldiers and gavebirth to a ba<strong>by</strong> in the bush when I was only 13.A second child was born when I was 18. I wasrelatively lucky because the man who becamemy husband was not an old commander but anabducted child like me from the same village.I was forced to use a gunand kill people... I do notknow how many peoplewere injured or killed <strong>by</strong>my bullets.He was a kindly man who always took care of meand my babies.It was not easy for me to live in the bush.Whenever the government force, the UPDF,attacked girls with babies, we could not protectourselves. Helicopter attacks did not distinguishbetween children, women and men. Along withmen, many girls and their babies were killed orinjured during crossfire. I saw so many childrenshot and killed. I myself was shot in the handand still feel pain even now. I did my best to try toescape in order to defend my children, but whenthey began to cry, the adult soldiers sometimesgot angry and beat me.I WAS FORCED TO USE a gun and kill people. I wastrained how to use a gun in Sudan and how to fightthe UPDF in the bush. Then one day I was given agun and ordered to kill enemies. I could not stoptrembling when I fired a gun for the first time.I do not know how many people were injuredor killed <strong>by</strong> my bullets. I do not know whetherI killed civilians. Once crossfire broke out neara village there was almost no way for me todistinguish between civilians and the army. I havehad nightmares ever since. But I had no choicebut to fight until I was rescued <strong>by</strong> the UPDF at theage of 19.I continue to suffer from gun violence even4

Left alone to die slowlyCATHERINE, SIERRA LEONEAfricaON 7 JANUARY 1999, early in the morningwhile I was still in bed, I heard gunshots in ourcompound. I quickly woke up my husband andchildren and we hid in the wardrobe. We were soscared. We didn’t know what to do.Suddenly rebels banged on the door andforced it open. They demanded money from myhusband and he gave them 50,000 leones, whichwas all we had in the house. They asked for moremoney but there was nothing left. One of therebels cocked his gun and threatened to blowmy husband’s head off if he refused to give themmore money.‘You people thought we had gone, but we arehere today to kill all of you bloody civilians whorefused to support us!’ the rebel said. ‘If you haveno money then let me send you to eternal rest!’Then he shot my husband in the chest, whocried out, ‘You have killed me!’I could not bear it so I opened the door of thewardrobe, shouting, ‘You killed my husband!’Then they grabbed hold of me and all sixsoldiers raped me one after the other in frontof my kids. After the first rape, they askedeverybody else in the house to come outside. Oneof the rebels ordered me to march forward atgunpoint, and suddenly I saw smoke. He startedlaughing at me and told me that our house wasnow on fire.Whenever I criedand begged them,they insulted meand intensifiedtheir assault.THE SIX MEN CONTINUEDto torture me. They tiedmy legs and hands aparton a tree and kicked me inthe stomach. They rapedme again, one after theother, and invited othercombatants to join them.Whenever I cried and begged them, they insultedme and intensified their assault. Between 15 and20 men raped me that night.I was so helpless, I kept on bleeding.Eventually I felt something come out between mylegs. I later learnt that it was my womb. I was leftalone to die slowly for more than a month.after escaping the LRA. When I came back homeI found that my father had been killed <strong>by</strong> rebelsseveral years earlier. I met my husband at arehabilitation centre. He had been rescued ayear before me, but he was blinded <strong>by</strong> a bulletwhich hit him during a battle with the UPDF.When I met him he said, “I could not even seeour native village, and I found my parents haddied while I was in bush for 11 years. Now Icannot even see your face. I feel that a newdarkness laps over me.”Some neighbours said to us, “You are killers!You killed our relatives! Why did you come back?”But we just want to live in peace again like beforewe were abducted.I sometimes imagine what my life wouldhave been like if nobody had ever broughtweapons even a child can handle to our land ormanufactured them anywhere in the world. I couldhave spent my teen years with my beloved familyand friends in peace and happiness. Althoughit is too late, I hope that people who make suchweapons and transfer them to our land realisethe suffering they cause us in Uganda. More than20,000 children in my country were abducted andforced to fight as soldiers like me.For the past month I have been learninga vocation. I want to change my future eventhough it is difficult. I believe people can make adifference. My husband is studying small-scalebusiness. Although he is blind, he is committedto supporting our family. My hope is that in thefuture our children will be able to live in peace,free from fear of gun violence.5

AfricaTrying to get helpFADY, MALII WAS THE VICTIM OF A BARBARIC ACT in 1993on my way back from Gossy with my husband,Agaly Haidara, during the Touareg rebellion. Wewere attacked <strong>by</strong> a gang of armed bandits whileriding in a cab 50km from Gao in Intahaka.Suddenly we heard the driver shout, ‘It isthem, the rebels!’ I then realised my husbandwas leaning on me. Hehad just been shot inthe chest. The gunmenshot at us because theythought our driver failedto stop at their warning.The bullet went throughmy husband’s chest andlodged itself in my rightthigh, where it still liesto this day. There was noone to call for help. Later, we were rescued <strong>by</strong> aparliamentarian, Abdoul Madjid, andsome soldiers.When I realised that I was bleeding from mythigh I remembered that my father had taughtme to use a tourniquet in such a situation. I tookoff my headscarf and tied it around my thighin order to stop the bleeding. I held my deadhusband until we got to Gossy.The doctor nearly fainted when he saw us.He was so shocked that other people had tohelp stop my bleeding. The cab was drenchedwith our blood.I HAD TO HIRE A CAR TO TRANSFER myhusband’s body to Gao, where another doctortold me that there was nothing seriously wrongwith me. However, I was sure I had a foreignobject in my body. I knew it and felt it.My parents helped me travel to Bamakofor a more advanced check-up and x-ray whichconfirmed the presence of a bullet in my rightthigh. But I didn’t receive any particular care orcompensation despite the fact that I was entitledto it.Now I want to get the bullet out of my body. Ifeel it when I sleep for a long time on the rightside of my body or when it is cold. I want to befreed from this burden in my body, but I am poorand I need help.Later one of my relatives, Souleymane Idrissa,the former mayor of Gao, helped me to travel toCotonou where I received some treatment, but Ihave not gone back as I am too scared.Now I want to get the bullet out of my body.I feel it when I sleep for a long time on the rightside of my body or when it is cold. I want to befreed from this burden in my body, but I am poorand I need help.6

Hoping for peaceANONYMOUS, PAKISTANAsiaAT THE TIME OF MY BIRTH, my father anduncles prepared to fire their guns into the air incelebration. They were expecting a son. When Iwas born, they were very disappointed. Nobody inthe family was ready to welcome a girl child.The guns that remained silent at my birthwould later wreak havoc on my life.I was raised in a culture where guns andgun violence were routine. My male familymembers always carried weapons, and I wasafraid of them. Like most girls in my village, Iwas deprived of an education. My mother toldme not to complain because my brothers orfathers would kill me if they found out I wantedto be educated. ‘Don’t do this or that, otherwiseyour father will kill you’ was the most commonsentence I ever heard from my mother until Ireached puberty.When I was very young, I married a man wholoved nothing more than guns and weapons. Abloody 35-year dispute was raging between myhusband and his cousins over a very minor issue(my husband’s cousin had thrown water on myhusband during prayers some 35 years earlier).Over the years, this trivial feud claimed the livesof 98 people, including my husband, my son, mytwo brothers-in-law and many others.Although I had long been frightened <strong>by</strong>even the sight ofweapons, the familydispute forced meto learn how to fire,load and clean guns.My husband taughtme how to fire aAfter he died, I sold his weaponsto buy coffins and medicine for mydisabled son.Kalashnikov, 30 and 32-bore pistol and a 12-boreshotgun. I hated every second of it, but he wouldpunish me severely if I admitted this. He said thatif I wanted to remain his wife and alive, I had tolearn how to use these weapons.My entire life has been filled with bloodshed,tears and sorrow. Not a single year has passedwithout lives being taken. In 2000, my husbandand eldest son went out formorning prayers and theynever came back. They wereshot dead on their way homefrom the village mosque.In 2005, my 16 year-oldson Nasir was shot <strong>by</strong> anunidentified gunman in thesnooker club he ran. He wasshot three times in the chest and his spinal cordwas badly injured. He is now paralysed.My husband used to buy weapons <strong>by</strong> sellingmy jewellery and his property. After he died, Isold his weapons to buy coffins and medicine formy disabled son. Today the only source of incomefor my seven-member family is my 15 yearoldson, who earns less than $100 per monthworking in a motor mechanic workshop.I WONDER WHO TO BLAME for my misery. I wishI could destroy all the weapons from all overthe world, weapons which only kill, take fathersfrom their children, sons from their mothers,brothers from their sisters, and husbands fromtheir wives. I have lost almost all I have to gunviolence, and I feel very worried for the childrenof my village, city, province, country and world.I am alarmed to see that my government hasfailed to effectivelyaddress the problemof gun violence.Politicians do not careabout the children ofour nation.I hope that aday will come when no daughter, bride, wife ormother will suffer my fate, a time when people onearth will be able to live in peace without violenceand without weapons. I hope for a time whenpeople and governments will unite to eliminatelife-threatening weapons from God’s world.7

AsiaFour years of rapeANONYMOUS, INDIAI WAS A 13 YEAR-OLD girl and the youngestchild in my family. My parents were teachers. Inour town a play on the life of Lord Rama calledRamleela used to play for two weeks every year.Families would watch the play in a venue calledRamleela Maidan. I was a regular visitor. Asyoung teenagers, we would get permission froma friend’s parents for all of us to go.That evening, I was with my boyfriend and wehad just met one of our friends.It was around 9.30 or 10 pm. Thethree of us were passing througha dark lane (in winter the lanesare empty and often unlit), whensuddenly three men around 20or 25 years of age appeared from nowhere andscolded my friend and me <strong>by</strong> asking, ‘Where areyou two going in the dark?’ They said they werepolice in civilian dress. They had revolvers. Theytold my friend to go home immediately or returnto the theatre. My boyfriend disappeared afterthey pointed a gun at him.They asked me where I lived and I told themmy address. I was very scared as they said theywould tell my parents that I was walking aroundwith a boy in the dark instead of attending the playlike I was supposed to be. In India in those days itwas regarded as very bad for girls to roam freelywith boys. My parents were very strict, especiallymy father, who was short-tempered.The men ordered me to follow them sothey could take me home. We were marchingtogether, the three of them and me. Suddenlythey turned into a road that led to an abandonedarea of our city. I immediately said, ‘This is notthe way to my home!’ They held the gun to mytemple and told me to follow them silently orelse they would shoot me. I was sure I had beenkidnapped. I was a small girl and I started crying.Either I face what comes next or I die.At gunpoint, the three men took me to anabandoned plot surrounded <strong>by</strong> walls. One of themtold me he was totally in love with me and thatWith all my soulI am against guns.he would kill my parents unless I reciprocated.He said nothing would happen to him as he wasa policeman. He demanded that I respect his loveand said that he could wait no longer.I thought I had to give in or else I wouldbe killed <strong>by</strong> the gun. I did not want to die. Mymum wanted me to study hard and become alawyer. She adored me because I was the mostintelligent of her children, the youngest with apromising future.So I told him I loved himtoo. He demanded that sinceI loved him, and as proof ofmy loyalty, I must allow himto have me physically. He saidwe would marry later. I was shocked and startedcrying loudly. His friends helped him to rape meat gunpoint ‘as a proof of my loyalty towards him.’Then they took me home.After that he would follow me to my schoolalmost daily and would wait for hours near theschool so that he could follow me and force meto have physical contact on demand, always atgunpoint. He and his friends pressured me tobring them one of my friends so they could rapeher too.WHENEVER I RESISTED HE WOULD first insistthat he loved me and that he wanted to marryme. If I resisted further he would point his gunat me. If, in a fit of rage, I screamed that he mustkill me, then he would point the gun on himselfand say he might as well kill himself too. Myboyfriend was warned never to see me again.This went on for the next four years.Eventually my mum guessed that somethingwas troubling me. I told her that some boys werebothering me on the way to school but did notmention a word about the gun or the repeatedrape because my father’s anger would be worsethan anything else. I suffered repeated vaginalinfections at that young age, but I dared not seekany treatment.8

AsiaHome terrorised <strong>by</strong> gunsKAREN, PHILIPPINESI WAS BARELY FIVE YEARS old when my father,a field military officer, was assigned to workin Mindanao. Because my mother was alsoworking, she sent my two siblings and me to livewith different relatives. We lived apart for thenext ten years. My father visited us during eachChristmas season but was always in a hurryto leave.In 2001 my father came back for good. Mymother fetched us from our relatives and we alllived together again under one roof. The first fewmonths were awkward but happy. It was as if wewere meeting new people and my father tried hisbest to catch up with us.Things started to change one day whenmy father got drunk and came home reekingof alcohol. He grabbed my mother’s hair andshouted and cursed at us. When we thought hehad finally calmed down, we put him to bed.The next morning he got up early. We sawhim sitting at the dining table where his threepistols lay in bits and pieces. Hewas cleaning them. Everybody wasshocked at the sight.That afternoon he left thehouse for a couple of hours. Whenhe came back he was carryingthree guns, one in his hand, andtwo behind his back. We will neverforget what happened next. Hegrabbed my oldest sister and pointed a gun ather head. My mother screamed and begged himnot to pull the trigger.Maybe her screams annoyed him becausehe pushed my sister to the ground and divertedhis attention to my mother. Pointing his gun ather, he kicked her and dragged her to their roomwhere he violently ripped her clothes. My mothersubmitted to him so he would not touch any ofus. But it wasn’t enough. He beat her almost todeath while having sex with her. We could hearthem from the living room. We knew it was rape.My father did not even take care to close the door.It was like he wanted us to see him abuse ourmother.This went on for five years. For five years weheard our mother’s screams. For five years myfather always carried a gun with him and pointedit at all of us.ONE AFTERNOON WE CAME HOME from schoolto hear my father beating my mother. Thescenario had become so normal that we madeno noise and carried on with our daily routine.Suddenly we heard three gunshots followed<strong>by</strong> silence. We were terrified. After a coupleof minutes had passed, we heard our mothersobbing. She came out with a gun in her handand blood dripping from her clothes. She hadshot my father in his stomach three times.For five years we heard our mother’sscreams. For five years my father alwayscarried a gun with him and pointed it atall of us.Miraculously, the gunshots did not kill him,but they paralysed half his body.Today the five of us live in the same house.My mother still works. However, now we all haveto take care of my disabled father.10

AmericasKeeping hope aliveLUCIANA NOVÃES, BRAZILMY NAME IS LUCIANA NOVÃES and I am 22years old. I was a nursing student at Estacio deSá University in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil until 5 May2003, when I was hit in the neck <strong>by</strong> a stray bulletfired from somewhere outside. At the time, I wasinside the university, having a snack with a friendon a break between two exams.I have no memory of being shot. All I recallis waking up at the hospital and being confrontedwith the horror of what had happened. It wasan awful moment. I was just 19 years old at thetime. I had just been offered two jobs and wasplanning to start working in addition tomy studies.Instead, I spent the next year and ninemonths in hospital. The last six months of thistime were spent waiting to be moved to a homemore suited to accommodate my many needs.Doctors explained to me that the bullet hadentered the left side of my jaw, destroying avertebra and lodging itself in my spinal column.Now I move in a wheelchair and a machinemakes it possible for me to breathe.I was told the bullet came from a securityguard’s gun, but the real story was neveruncovered, the culprit never found. There wasa trial, and the University has to pay somecompensation, but so far all I received was ahouse on loan.The doctors told me I would never speakor eat again. Now I can do both things. Ibelieve I will keep getting better. My aim isto be able to breathe without help. When Ido that, I will be able to move around moreeasily and not be so homebound. Hopeshould be the last thing to die.THE ACCIDENT INTERRUPTED all my dreams.I took care of my father after his stroke, andall I wanted was to continue helping him andothers who would need my services as a nurse.Instead, now I am the one who needs lookingafter. My parents care for me around the clock;nurses come to me for twice daily physiotherapysessions. My sister Jo leaves her three childrenevery day to come and help.My favourite thing was going to the beach andthe gym. Now I read and watch TV from my chair.But I have faith. The doctors told me I wouldnever speak or eat again. Now I can do boththings. I believe I will keep getting better. My aimis to be able to breathe without help. When I dothat, I will be able to move around more easilyand not be so homebound. Hope should be thelast thing to die.11

AmericasOnly one bullet...MARTA ELSA GHIGLIA DE CANILLAS, ARGENTINAMY NAME IS MARTA ELSA Ghiglia de Canillas,but since 12 July 2002 I am known simply as JuanManuel’s mother.Our family used to call ourselves ‘LosCinquito,’ (‘The Fabulous Five’) and we lived inthe heart of the capital city of Argentina in a veryquiet residential area called Núñez, with bighouses, gardens in bloom and neighbours whohave known each other forever.It was a day just like any other for everyonein the family. It was Friday and dinnertime wasapproaching. Two of my children went to pick uptheir girlfriends. My husband had recently hada heart operation and was already home. I wasmaking dinner.The phone rang. I answered it and it was JuanManuel, the second of my three boys, who said,‘Mum, gather all the money we have at home andtake it to the front door. I will drive <strong>by</strong> to get it.’Since I thought he was buying something andneeded change, I asked him, ‘Tell me Juancho,how much money do you need?’‘Really mum, all the money we have in thehouse!’ he replied.That was the last time I heard his voice.The last ‘mum’ he gave me. Kidnappers hadintercepted him a few blocks from the house andmade him call us on a mobilephone. Almost instantly hiscar drove to our house withhim and the three kidnappersinside. We gathered all themoney we had in the houseand my husband went out togive it to them.In a desperate attemptto see our child, who wassitting in the back seat, myhusband peaked into one ofthe windows. One of the kidnappers hit him in theface and broke his glasses. They then started thecar and left.They let Juan Manuel off a few blocks fromOne bullet was all it took for meto cease being a happy housewifeand to push me out on to thestreets to seek justice for my sonand for so many others.the house. They let him get out of the car, andjust as he was running towards freedom, withoutany reason or warning, they shot him in the backand killed him.It is difficult to understand. Juan Manuel gavethem everything he owned: jewellery, money, thecar. But their greed was greater. They took his life.The ‘kidnap that became a murder,’ asthe killing of our son was referred to, was anemblematic case that resonated throughoutthe country. One of the murderers was arrested20 months ago and given an exemplarily longsentence, but it can still be appealed. The othertwo are awaiting trial.JUAN MANUEL’S MURDER was regrettable,but it was not the first or last of its kind. Thecorruption, complicity and poor performance ofsome public servants allows crime to prevail.There are many people with guns and they usethem to exercise their power.I am not going to pretend that Juan Manuel’skillers can begin to understand how precious thelife they destroyed was. It would be absurd to thinkthey would to be able to appreciate his values.Juan Manuel got his bachelor’s degree at 21and worked in his own business. At 23, he was arespectable professional and was about to starta new career as a doctor. He also loved diving.But there was something even more important– everyone who knew him loved him.He was a wonderful son. A wonderful brother.A wonderful friend. Kind. Noble. Generous.Joyous. A great person, as we say around here.12

AmericasA lucky escapeMARÍA TERESA GUILLÉN CORVERA, COSTA RICAI WAS RETURNING FROM A trip to Costa Rica’sCaribbean and it was raining so I hailed a cab. Thecab was identified as it should be, but I didn’t takenote of the number plate because it was rainingand there were a lot of people at the stop.The cab driver started driving towards myneighbourhood but suddenly he stopped the carand pulled out a gun. He pointed it to my chestand said, ‘This is an assault, jump to the frontseat!’ Then he asked if I had any cash. I told himthat I kept my money in the bank, so he drove meto a cash machine.He was pretty nervous, and he told me thatif I said anything to anyone or made anyonesuspicious, he would kill me. I tried to keep calmto avoid being shot because he was so jumpy. Ieven tried to keep a conversation going with him.This relaxed him and before arriving to the bankhe told me that he liked me and that I shouldthank him for not raping me.As soon as I came out of the bank I gave himthe money. He left. I was in shock, and I couldn’tstop crying. I even forgot all the phone numbersof my family members and friends.Later, I made a formal complaint to thepolice, even though I did not think it wouldchange anything. I felt it was my duty. Twomonths later, however, I received a call froman investigator. He told me they had received20 formal complaints from women who hadbeen robbed <strong>by</strong> a cab driver and were onto theassailant. He also told me his last victims hadbeen raped. The cab driver was subsequentlyarrested and he is now in jail.I WAS SO AFFECTED BY the experience that Icouldn’t sleep at night and could no longer takecabs. Some people asked me uncomfortablequestions such as why I went in a cab alone orwhy I didn’t take note of the number plate. Somepeople said that I should have jumped out of thecab while the robber was driving.I often think about what would havehappened to me if I had been shot on purpose oraccidentally, or if I had been beaten and left onthe highway. My worst fear was of being sexuallyassaulted. This is because I am a woman. Maybea man wouldn’t feel the same fear that I feel,and that’s why I should be ‘thankful’ that I wasn’traped.I often think about what would havehappened to me if I had been shot onpurpose or accidentally... my worst fearwas of being sexually assaulted.And we could easily imagine him as head of afamily and a father.One bullet was enough to shatter the livesand dreams of those who loved him. It only tookone bullet to destroy ‘Los Cinquito!’It only took one bullet to annihilate thepossibility of having grandchildren to lengthenour lives.It only took one bullet for his grandfather tocry himself to death and for his grandmother tolive out her years mourning his death.One bullet was all it took for me to ceasebeing a happy housewife and to push me out onto the streets to seek justice for my son and forso many others.Marta Elsa Ghiglia de Canillas is Director of thePeace Initiatives Department of the ArgentineanSolidarity Network, Vice-President of theAsociación Madres del Dolor, and a volunteer atMissing Children, the Lost Boys of Argentina.13

AmericasTrying to make a changeKARIN WILSON, USAI LOST MY BELOVED SON, my only childChristian, on 3 Dec 1999. Just 28 days after heturned 19, he was a man-child, not quite an adultbut past adolescence. The millennium came ina way I could have never imagined. The pain isindescribable; the magnitude of my loss makesme inconsolable. I’ve been wronged and robbed!I’m from the United States, I live in the state ofNew York, born and raised in the borough ofBrooklyn. The US is one of the most powerfuland technologically advanced countries on thisplanet. We haven’t fought a war in this countrysince the American Civil War, a war that wasfought from 1861-1865.Yet in my neighbourhoodand in many others in thiscountry we hear gunshotsat night. Parents start doingsilent headcounts of theirchildren after hearing thesound of gunshots. Wehave neighbours, friendsand family members who were either maimed orkilled with a firearm. Because of my son’s deathI became part of the largest grassroots anti-gunviolence movement in the United States.Let me tell you how my life has changed.I won’t have the comfort of my son lookingafter me in my old age. I won’t have my sonaround making sure I’m eating well, taking mymedications properly, taking care of my bills,making sure my house is warm in winter, and thesidewalks shovelled and de-iced when it snows.I don’t have any more graduations to attend,or opportunities to applaud successful careerachievements. I no longer hear funny storiesor jokes (and I was told my son was one of thefunniest guys around, he kept people laughingand feeling good.) But worst of all I can’t look ator touch him anymore.You probably have wives and husbands,children and grandchildren. You know it’s throughour children we get a little bit of immortality. YouI’ve learned that thereis nothing like definite,overt action to overcomethe inertia of grief.know that your face, your body type, your valuesare going to be around long after you’re gone…because of your children. Children are our legacy.Well I was robbed, and it looks like I won’thave a legacy now. My face, my body type, myvalues will probably disappear when I die – itdoesn’t look like any part of me will appear in thefuture. In the next century it will be as if I never,ever existed. And that’s pretty sad.I’ve learned that there is nothing like definite,overt action to overcome the inertia of grief. Mostof us have someone who needs us. If we haven’t,we can find someone! So instead of praying forthe strength to survive, Iprayed for strength to giveaway. Then I joined TheMillion Mom March. I wentfrom being a victim of gunviolence to a survivor of gunviolence. And now I’m anadvocate for survivors.I’m thoroughlycommitted to saving other children. Though Icouldn’t save my own child’s life, I’m going to doall I can to save yours.I KNOW IT IS POSSIBLE to reduce the numberof deaths and injuries caused <strong>by</strong> gun violence.Our children have the right to grow up inenvironments free from the threat of gunviolence. My son certainly had that right which hedidn’t get.Our children want to grow old. All humanshave the right to be safe from gun violence intheir homes, neighbourhoods, schools andplaces of work and worship.<strong>Gun</strong> violence is a public health crisis of globalproportions that harms not only the physical,but the spiritual, social and economic health ofour families and communities. The Million MomMarch has a slogan which I subscribe to 100%:‘No child’s life should end with a bang.’I’m trying to understand why my child had14

AmericasImmeasurable painKAREN VANSCOY, CANADAON SEPTEMBER 24, 1996, my beautiful 14 yearolddaughter Jasmine (pictured below) was shotin the head <strong>by</strong> a 17 year-old young man who hadobtained a semi-automatic handgun from hisstepfather’s collection of unsecured guns andammunition.I don’t know which memories of this eventare worse.Was it saying my last good<strong>by</strong>es to my onlydaughter while she lay in the hospital bed, herface bruised and bandaged?Her skull had shattered and her brainexploded when the gun pierced her head. Shewas already gone. There was only the mechanicalrise and fall of her chest.Or was it returning home for the first timesince her death? The walls and floors werecovered with blood, decaying flesh and brainmatter. The smell was putrid; it was like a scenefrom a horror film. Noone had advised us thatwe would be faced withcleaning up the mess.Then there are theimages of my autisticson Jordan describingthe blood oozing fromher ears and mimickingher killer <strong>by</strong> grabbinga knife, pointing it andshouting, ‘I’ll fuckingkill you!’ I guess IThis act of violence has had negativeconsequences for her friends,teachers, community and everyonearound her. <strong>Gun</strong> violence affects all ofus. We need to work toward creating aculture of safety, security and peace.<strong>Gun</strong> violence is avoidable.would have to choose this last memory as theworst because my son Jordan continues to sufferimmensely due to the trauma of witnessing themurder of his sister, friend and caregiver.THE TRUE IMPACT OF GUN violence isimmeasurable. My family has not only had to facethe death of a child, we’ve suffered emotionaland mental health difficulties, and we lost ourhome, and much, much more.Jasmine’s death did not affect just us. Thisact of violence has had negative consequencesfor her friends, teachers, community andeveryone around her. <strong>Gun</strong> violence affects all ofus. We need to work toward creating a cultureof safety, security and peace. <strong>Gun</strong> violence isavoidable.to die <strong>by</strong> gunshot, but I don’t understand. If I hadone wish it would be that all governments wouldmonitor the manufacturing and distribution offirearms and bullets with the same degree ofcare that they use to monitor the removal ofnuclear waste from reactors.We have an opportunity to change laws andcreate real accountability on these items. Wehave to stand up now and be counted on to do theright thing.Karin Wilson is a volunteer for the Brooklyn,New York chapter of the Million Mom March, agrassroots organisation campaigning for sensiblegun laws. She gave this speech at the UnitedNations in July 2005.15

EuropeLiving under the gunVESNA, MACEDONIAI WAS BEATEN UP BY my husband for the firsttime soon after our wedding. I thought that it wasnormal. Soon after that, his verbal and physicalassaults became more and more frequent.During the last 12 years of our marriage, myhusband harassed me literally every day and beatboth me and my children. Onseveral occasions he chased meout of the house with a gun inhis hand.I did not have anywhere togo and did not dare to leavemy home. My parents were notable to help, so I had to bear theharassment.My husband never had anymoney to support us, but once amonth he would replace his guns. He would oftencome home very drunk and sit on the table wherehe would take out his ‘new child’, as he referredto the guns he obtained from the Old Bazaar [themarketplace in Skopje]. He would stroke andcuddle them as if they were the most importantthing in his life. ‘You represent everything to me,in good times and in bad. With you, I will get rid ofVesna. I will blow her to pieces,’ hewould say to his gun.Then once when he was drunkhe shot at me and at my son. Istill carry the bullet wounds andmy child is receiving psychiatrictreatment.I AM MOST UPSET WITH the police who stood <strong>by</strong>and did nothing even though they knew there wasarmed violence in our home and that my husbandhad an illegal gun. ‘Do not argue in front of thechildren, it is not good for them,’ is all they wouldsay when I called on them to intervene.I am most upset with the police whostood <strong>by</strong> and did nothing even thoughthey knew there was armed violence inour home and that my husband had anillegal gun.After 18 years of marriage and 12 years ofdaily harassment, I finally succeeded in escapingfrom my home with my young daughter a fewmonths ago, and we are now living in a shelter.16

InformationFurther readingResources from the IANSA <strong>Women</strong>’s NetworkIANSA <strong>Women</strong>’s Network Portal and Bulletin:http://www.iansa.org/womenIANSA Information Kit on <strong>Women</strong> and Armed<strong>Violence</strong>: http://www.iansa.org/women/documents/<strong>Women</strong>-and-<strong>Gun</strong>s-Information-Kit.pdf‘<strong>Women</strong>, Men and <strong>Gun</strong> <strong>Violence</strong>: Options forAction,’ in Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue,Missing Pieces: Directions for Reducing <strong>Gun</strong><strong>Violence</strong> through the UN Process on Small ArmsControl, 2005 http://www.hdcentre.org/datastore/Small%20arms/Missing_Pieces/Missing%20Pieces.pdfPublicationsControl Arms, The Impact of <strong>Gun</strong>s on <strong>Women</strong>’sLives, 2005. http://www.controlarms.org/documents/smalla-arms-women-report-final2-1.pdfVanessa Farr & Kiflemariam Gebre-Wold (eds),Gender Perspectives on Small Arms and LightWeapons: Regional and International Concerns,BICC Brief 24, 2002. http://www.bicc.de/publications/briefs/brief24/brief24.pdfVanessa Farr, ‘Scared Half to Death: The GenderedImpacts of Prolific Small Arms,’ ContemporarySecurity Policy Vol. 27, No. 1(April 2006: 45-59):2006International Alert, Inclusive Security, SustainablePeace: A Toolkit for Advocacy and Action. http://www.international-alert.org/our_work/themes/gender_training.phpNicola Johnston and William Godnick withCharlotte Watson and Michael von Tangen Page,Putting a Human Face to the Problem of SmallArms Proliferation: Gender Implications for theEffective Implementation of the UN Programme ofAction, 2005. http://www.international-alert.org/pdfs/gender_and_programme_of_action.pdfElisabeth Rehn & Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, <strong>Women</strong>,War, Peace: The Independent Experts’ Assessmenton the Impact of Armed Conflict on <strong>Women</strong> and<strong>Women</strong>’s Role in Peace-Building, 2002.http://www.unifem.org/resources/item_detail.php?ProductID=17UNIFEM, Getting it right, doing it right: Gender andDisarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration,October 2004. http://www.womenwarpeace.org/issues/ddr/gettingitright.pdfWebsitesIANSA <strong>Women</strong>’s Network Portal: http://www.iansa.org/womenPeacewomen Project of the <strong>Women</strong>’s InternationalLeague for Peace and Freedom (WILPF): http://www.peacewomen.org/UNIFEM Portal on <strong>Women</strong>, Peace and Security:http://www.womenwarpeace.org/ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSMost of all we thank the women who contributedtheir stories for this publication. We are gratefulto many members of the IANSA <strong>Women</strong>’s Networkwho helped us compile the stories and photographs,including Wendy Cukier (Coalition for <strong>Gun</strong> Control,Canada), Maria Pia Devoto, Raquel Dias, NatasaDokovska (Journalists for Children and <strong>Women</strong>’sRights and the Protection of the Environment),Jessica Galeria, Shobha Gautam (Institute ofHuman Rights Communication Nepal – IHRICON),Viviane Kitete, Geeta Kurhade (Medicovet RuralWelfare Society), Miel Laurinaria (Kilusang parasa Pambansang Demokrasya), Fatoumata Maiga(Association des Femmes pour les Initiatives de Paix– AFIP), Christelle Manirankiza Feza (Associationdes Jeunes Chrétiens en Afrique Centrale – AJECA),Roselyn Mungai (Oxfam GB Kenya), Qamar Naseem(Blue Veins), Ruth Ochieng, Shingo Ogawa (TerraRenaissance), Viviam Perrone (Asociación Madresdel Dolor) and Dulce Umanzor.‘Survivors’ was compiled and edited <strong>by</strong> SusannaKalitowski, IANSA <strong>Women</strong>’s Network Coordinator.Thanks also to Magda Coss, Ludovic N’Doua, FranProtti-Alvarez and Branislav Trajkovski for theirtranslation assistance. It was designed <strong>by</strong> HilaryTranter. The project was funded <strong>by</strong> the Governmentof Norway.

‘‘My hope is that in the future ourchildren will be able to live in peace,’’free from fear of gun violence.Janet Aol, UgandaThe IANSA <strong>Women</strong>’s NetworkWOMEN HAVE TAKEN a leading role inefforts to prevent gun violence all over theworld, yet they remain underrepresented insmall arms policy and practice. The IANSA<strong>Women</strong>’s Network was founded to connectorganisations working on women’s issueswith the global campaign to control theproliferation and misuse of small arms,and to ensure that this campaign reflectswomen’s concerns and reality. We aim to builda united and dynamic movement of womenresisting gun violence around the world.IANSA <strong>Women</strong>’s Network members comefrom a diverse range of organisations inevery region of the world. They are workingto mobilise popular opinion against theproliferation and misuse of small arms,lob<strong>by</strong>ing for policy change at the national,regional and international levels, andproducing much-needed information aboutthe different ways that gun violence affectswomen, men, girls and boys.The IANSA Secretariat supports theefforts of <strong>Women</strong>’s Network members<strong>by</strong> promoting their work to the largerdisarmament community, particularly at theUN level, producing information on topicsrelated to women, gender and small armsand acting as a focal point for global policyon gender and small arms. The <strong>Women</strong>’sNetwork Portal, www.iansa.org/women,contains the Network’s quarterly bulletin,<strong>Women</strong> at Work: Preventing <strong>Gun</strong> <strong>Violence</strong>,as well as news and resources on women,gender and small arms.international action network on small armsIANSA – International Action Network on Small Arms56-64 Leonard Street, London EC2A 4JX, UK Tel: +44 (0)20 7065 0870www.iansa.org women@iansa.org