Noninvasive vulvar lesions An illustrated guide to ... - Urogyn.org

Noninvasive vulvar lesions An illustrated guide to ... - Urogyn.org

Noninvasive vulvar lesions An illustrated guide to ... - Urogyn.org

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

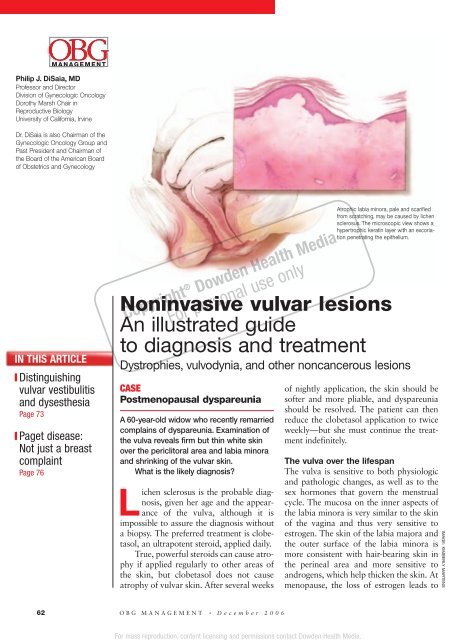

For mass reproduction, content licensing and permissions contact Dowden Health Media.OBGM ANAGEMENTPhilip J. DiSaia, MDProfessor and Direc<strong>to</strong>rDivision of Gynecologic OncologyDorothy Marsh Chair inReproductive BiologyUniversity of California, IrvineDr. DiSaia is also Chairman of theGynecologic Oncology Group andPast President and Chairman ofthe Board of the American Boardof Obstetrics and GynecologyIN THIS ARTICLE❙ Distinguishing<strong>vulvar</strong> vestibulitisand dysesthesiaPage 73❙ Paget disease:Not just a breastcomplaintPage 76<strong>Noninvasive</strong> <strong>vulvar</strong> <strong>lesions</strong><strong>An</strong> <strong>illustrated</strong> <strong>guide</strong><strong>to</strong> diagnosis and treatmentDystrophies, vulvodynia, and other noncancerous <strong>lesions</strong>Copyright ® Dowden Health MediaFor personal use onlyCASEPostmenopausal dyspareuniaA 60-year-old widow who recently remarriedcomplains of dyspareunia. Examination ofthe vulva reveals firm but thin white skinover the pericli<strong>to</strong>ral area and labia minoraand shrinking of the <strong>vulvar</strong> skin.What is the likely diagnosis?Lichen sclerosus is the probable diagnosis,given her age and the appearanceof the vulva, although it isimpossible <strong>to</strong> assure the diagnosis withouta biopsy. The preferred treatment is clobetasol,an ultrapotent steroid, applied daily.True, powerful steroids can cause atrophyif applied regularly <strong>to</strong> other areas ofthe skin, but clobetasol does not causeatrophy of <strong>vulvar</strong> skin. After several weeksAtrophic labia minora, pale and scarifiedfrom scratching, may be caused by lichensclerosus. The microscopic view shows ahypertrophic keratin layer with an excoriationpenetrating the epithelium.of nightly application, the skin should besofter and more pliable, and dyspareuniashould be resolved. The patient can thenreduce the clobetasol application <strong>to</strong> twiceweekly—but she must continue the treatmentindefinitely.The vulva over the lifespanThe vulva is sensitive <strong>to</strong> both physiologicand pathologic changes, as well as <strong>to</strong> thesex hormones that govern the menstrualcycle. The mucosa on the inner aspects ofthe labia minora is very similar <strong>to</strong> the skinof the vagina and thus very sensitive <strong>to</strong>estrogen. The skin of the labia majora andthe outer surface of the labia minora ismore consistent with hair-bearing skin inthe perineal area and more sensitive <strong>to</strong>androgens, which help thicken the skin. Atmenopause, the loss of estrogen leads <strong>to</strong>IMAGE: KIMBERLY MARTENS62 OBG MANAGEMENT • December 2006

atrophy, and the <strong>vulvar</strong> epithelium isreduced <strong>to</strong> a few layers of mostly intermediateand parabasal cell types. The labiaminora and majora as well as the cli<strong>to</strong>risgradually become less prominent with age.The skin of the vulva consists of bothdermis and epidermis, which interact witheach other and respond <strong>to</strong> different nutritionaland hormonal influences. Forexample, estrogen has little effect on <strong>vulvar</strong>epidermis, but considerable effect onthe dermis, thickening the skin and preventingatrophy.Postmenopausal atrophic changes canbecome a clinical problem when a womanresumes sexual intercourse after a long periodof abstinence, as in the opening case. Ifatrophy is the main complaint, estrogenreplacement therapy will alleviate symp<strong>to</strong>msof tightness, irritation, and dyspareunia, butit may take 6 weeks <strong>to</strong> 6 months <strong>to</strong> achieveoptimal results. In the interim, women need<strong>to</strong> be reassured that reasonable function canbe achieved.Hygienic considerationsWith any <strong>vulvar</strong> irritation, the patientshould discontinue the use of syntheticundergarments in favor of cot<strong>to</strong>n panties,which permit more adequate circulationand do not trap moisture.Sitz baths often help relieve local discomfort,but should be followed by thoroughdrying.❚ Vulvar dystrophies:Think “white”In the past, these diseases have beendefined as non-neoplastic epithelial disordersof the vulva. Although there havebeen many attempts <strong>to</strong> more accuratelydefine <strong>vulvar</strong> dystrophies, none have completelydescribed the wide variety of clinicalpresentations.In general, dystrophies are disorders ofepithelial growth and nutrition that oftenresult in a white surface color change. Thisdefinition includes intraepithelial neoplasiaand Paget’s disease of the vulva. TheACOG opinion on vulvodyniaThe new ACOG Committee Opinion reflects recommendationsof the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. 17• Vulvodynia may be localized or generalized. Painlocalized <strong>to</strong> the <strong>vulvar</strong> vestibule, formerly termed <strong>vulvar</strong>vestibulitis, is now classified as localized vulvodynia.• The cause is unknown, and therefore it cannot bedetermined whether localized and generalized vulvodyniaare different manifestations of the same disease orcompletely different entities.• Treatment can be difficult, and improvement can takeweeks or months, even with appropriate therapy.– No single agent is successful in all women– Pain may never subside completely– Patients may need us <strong>to</strong> help them developrealistic expectations for improvement• Some women need psychological support, such assex therapy and counseling.Vulvodynia. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists CommitteeOpinion No. 345. Obstet Gynecol. Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2006;108:1049–1052.International Society for the Study ofVulvovaginal Disease has proposed multipleclassifications since 1975. I prefer theclarity of the 1987 classification system. 1 Ialso consider these terms out-of-date:lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, carcinomasimplex, leukoplakic vulvitis, leukoplakia,hyperplastic vulvitis, neurodermatitis,kraurosis vulvae, leukokera<strong>to</strong>sis, erythroplasiaof Queyrat, and Bowen’s disease.What makes the <strong>lesions</strong> white?The white appearance of dystrophic<strong>lesions</strong> is due <strong>to</strong> excessive keratin, at timesdeep pigmentation, and relative avascularity.All 3 of these characteristics are presentin the spectrum of <strong>vulvar</strong> dystrophies.Biopsy of the affected skin is the key <strong>to</strong>accurate diagnosis and successful therapy.FAST TRACKVulvar dystrophies❙ Lichen sclerosus❙ Squamous cellhyperplasiaFormerly “hyperplasticdystrophy”❙ Other derma<strong>to</strong>sis❙ Squamous cellcarcinoma in situMay present clinicallyat any age as papulesor macules, coalescent ordiscrete, single or multiple❙ Paget’s diseaseof the vulvaClinicopathologic entitywith a pathognomonichis<strong>to</strong>logic appearanceSource: Modified from Voet RL 1❚ Lichen sclerosusDoes not raise risk of carcinomaThe most common of the 3 groups ofwhite <strong>lesions</strong> described in the 1987 classificationof dystrophies, lichen sclerosususually occurs in postmenopausal women,but can appear at any age, including childwww.obgmanagement.comDecember 2006 • OBG MANAGEMENT 63

▲<strong>Noninvasive</strong> <strong>vulvar</strong> <strong>lesions</strong>: <strong>An</strong> <strong>illustrated</strong> <strong>guide</strong>FIGURE 1Lichen sclerosus affects all ages3-year-old child. Note the inflammationsecondary <strong>to</strong> excoriations.20-year-old woman. The glanscli<strong>to</strong>ris has begun the hoodingprocess.70-year-old woman. The introitushas shrunk, making intercourseimpossible.FAST TRACKThere is no goodevidence thatwomen with lichensclerosus facea higher risk for<strong>vulvar</strong> carcinomahood (FIGURE 1). Despite claims <strong>to</strong> the contrary,there is no good evidence thatwomen with lichen sclerosus face a higherrisk for <strong>vulvar</strong> carcinoma.Signs and symp<strong>to</strong>msIn lichen sclerosus, the skin of the vulvaappears very thin, atrophic, and dry,resembling parchment. It is also white,with loss of pigmentation.Pruritus is the most common symp<strong>to</strong>m andis usually the presenting symp<strong>to</strong>m.Scratching during sleep may create ulcerationsand areas of ecchymosis, and there isgeneralized shrinking of the <strong>vulvar</strong> skin,with eventual loss of the labia minora.The edema and shrinking that occuraround the cli<strong>to</strong>ris cause a “hooding” ofthe glans cli<strong>to</strong>ris. If the process continuesunchecked, it can involve the labia majoraas well as the skin of the inner thigh andanal region.Prescribe clobetasol ointmentThe patient should be instructed <strong>to</strong> use clobetasol0.05% ointment on a continuingbasis. This drug is so successful it haseclipsed the use of tes<strong>to</strong>sterone propionatefor this indication. Lorenz and colleagues 2found very high success rates in 81 symp<strong>to</strong>maticpatients with biopsy-proven diseasewho had failed previous therapy.For reasons that are unknown, persistentuse of this steroid on <strong>vulvar</strong> skin doesnot cause the atrophy commonly seen withprolonged use of high-potency steroids onother areas of the skin.Start with twice-daily application and taper<strong>to</strong> less frequent use as the symp<strong>to</strong>ms comeunder control. Most patients in remissioncan be maintained with twice-weeklyapplication. Pruritus should disappearcompletely, and the skin itself will becomeless “leathery.”Surgical treatment is not advisedSurgery does not appear <strong>to</strong> have a rolebecause lichen sclerosus often recurs outsideexcised areas. Several reports haveeven described the return of disease in skingrafts used <strong>to</strong> replace large diseased areas.I do not recommend surgery except indire circumstances, when symp<strong>to</strong>m relief isessential <strong>to</strong> the patient’s quality of life andall other therapies have failed.❚ Squamous cell hyperplasiaThis disease is probably the same entity aslichen simplex chronicus. Changes in <strong>vulvar</strong>skin appear <strong>to</strong> result from chronicscratching secondary <strong>to</strong> intense pruritus.This complaint often involves a viciouscycle of scratching, increased pruritus, andmore scratching, until excoriations occur.CONTINUED64 OBG MANAGEMENT • December 2006

<strong>Noninvasive</strong> <strong>vulvar</strong> <strong>lesions</strong>: <strong>An</strong> <strong>illustrated</strong> <strong>guide</strong>▲The aim of therapy is <strong>to</strong> eliminate the pruritus(FIGURE 2).Signs and symp<strong>to</strong>msVulvar skin is typically white or pink.Biopsy will confirm the diagnosis, revealinga markedly thickened keratin layer(hyperkera<strong>to</strong>sis) and irregular thickeningof the Malpighian ridges (acanthosis).Inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry changes are also present,especially when there are areas ofexcoriation.FIGURE 2Squamous cell hyperplasiaTreatment is similar<strong>to</strong> therapy for lichen sclerosusPotent <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroids are the backboneof treatment; clobetasol is the preferreddrug. The frequency of application isidentical <strong>to</strong> that described for lichen sclerosus,and response <strong>to</strong> therapy usually takes 2months. In the interim, it is advisable <strong>to</strong> prescribeother medications for the pruritus.Lichen sclerosus and squamous cell hyperplasiasometimes coincide. Fortunately, thetherapies are quite similar and both conditionstend <strong>to</strong> respond.75-year-old woman. The skin isthickened and may be leathery.• His<strong>to</strong>ry of yeast infection, 64%• Vulvar burning, 57%• Vulvar itching, 46%• Problems with sexual response, 33%Women with <strong>vulvar</strong> dysesthesia whoappear <strong>to</strong> have urinary tract symp<strong>to</strong>msshould undergo a urine culture, though itwill often be negative and antibiotic therapywill have little effect.Intense pruritus and aggressivescratching lead <strong>to</strong> excoriations.❚ VulvodyniaThis disorder consists of chronic <strong>vulvar</strong>discomfort due <strong>to</strong> itching, burning, and/orpain that causes physical, sexual, and psychologicaldistress. 3,4 Once referred <strong>to</strong> asessential vulvodynia, it now is defined asgeneralized <strong>vulvar</strong> dysesthesia.Signs and symp<strong>to</strong>msWomen with this condition tend <strong>to</strong> havedifficulty localizing their pain. They oftenpresent with a complaint of recurrent yeastinfection or constant irritation at theintroitus. Dyspareunia may or may not bea presenting symp<strong>to</strong>m, although intercourseoften triggers this condition. Tightpants or rough undergarments also maytrigger symp<strong>to</strong>ms.Common symp<strong>to</strong>ms. In a study bySadownik, 5 women with <strong>vulvar</strong> dysesthesiareported the following symp<strong>to</strong>ms:• Dyspareunia, 71%A diagnosis of exclusionThe pain of dysesthesia appears <strong>to</strong> be neuropathicin origin in that it mimics pain ofthe sensory nervous system. It may be diffuseor focal, unilateral or bilateral, constan<strong>to</strong>r sporadic. Thus, it is a diagnosis ofexclusion.Recommended therapiesVulvar dysesthesia should be regarded as achronic pain syndrome and treated accordingly,with emphasis on generalizedimprovements in health and attitude ratherthan single-therapy approaches.Potent <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroids are usuallyof no benefit. Nor does <strong>to</strong>pical estrogenproduce long-term relief.Once all possible causes of symp<strong>to</strong>msare excluded, refer the patient for education,support, and treatment of depression,if present. Occasionally, <strong>to</strong>pical anestheticswill provide short-term relief.At least 2 <strong>vulvar</strong> pain societies—theNational Vulvodynia Association and theCONTINUEDFAST TRACKVulvodynia painmay never subsidecompletelywww.obgmanagement.com December 2006 • OBG MANAGEMENT 69

<strong>Noninvasive</strong> <strong>vulvar</strong> <strong>lesions</strong>: <strong>An</strong> <strong>illustrated</strong> <strong>guide</strong>▲Vulvar Pain Foundation—have newsletters,outreach programs, and Web sites.❚ Vulvar vestibulitisA more readily definable condition in thesame category as vulvodynia is so-called<strong>vulvar</strong> vestibulitis, also known as localizedvulvodynia (as classified by the new ACOGCommittee Opinion on vulvodynia).Signs and symp<strong>to</strong>msThe defining presentation is severe pain onvestibular <strong>to</strong>uch (eg, entry at intercourse),with tenderness <strong>to</strong> pressure localized withinthe <strong>vulvar</strong> vestibule in a horseshoe distributionpattern encompassing 3, 6, and 9o’clock on the vestibule. Erythema is oftenpresent, especially at the 5 and 7 o’clockpositions (FIGURE 3).Patients have no symp<strong>to</strong>ms during normaldaily activities, but complain of dyspareuniaand an inability <strong>to</strong> use tampons.TABLE 1Distinguishing <strong>vulvar</strong> vestibulitis and dysesthesiaVULVAR VESTIBULITISPain is usually not constantErythema in sensitive areasLidocaine quells sensitivityCause is dermal inflammationESSENTIAL VULVAR DYSESTHESIAPain is a constant burning sensationNo erythema or abnormal appearanceLidocaine has no effectCause is allodynia (heightenednerve sensitivity)TABLE 2Impressive track recordfor surgical treatment of vestibulitis% RESPONSESTUDY COMPLETE PARTIAL NONEBornstein et al 7 76 24 0Bergeron et al 12 63 37 0Kehoe and Luesley 13 60 29 11Mann et al 14 66 21 13Schover et al 15 47 37 16Marinoff and Turner 16 82 15 3Adapted from Bornstein et al 7Diagnostic strategiesVulvar vestibulitis can be diagnosed usinga moistened cot<strong>to</strong>n-tip applica<strong>to</strong>r. Pressureapplied in the area of the urethral meatuswill result in minimal discomfort, but pressurein the horseshoe area of the vestibulewill cause exquisite discomfort.Careful inspection at 5 and 7 o’clockin the vestibule usually uncovers intenseerythema over an area of 4 or 5 mm. Todistinguish vestibulitis from dysesthesia,see the comparison in TABLE 1.Recommended therapiesTreatment of <strong>vulvar</strong> vestibulitis is complex.It is important <strong>to</strong> see the patien<strong>to</strong>ften <strong>to</strong> ensure that this syndrome is trulypresent rather than <strong>vulvar</strong> dysesthesia.Xylocaine jelly should be given in anattempt <strong>to</strong> relieve symp<strong>to</strong>ms; <strong>to</strong>picalsteroid ointments are another option.Women with persistent symp<strong>to</strong>ms aredifficult <strong>to</strong> treat medically. Earlier theoriespointing <strong>to</strong> infection as the cause ofvestibulitis have been discounted.Some experts believe that foods containingoxalates precipitate these symp<strong>to</strong>ms.It may be advisable <strong>to</strong> have the patientreduce the content of oxalates in her diet inan effort <strong>to</strong> address all possible remedies.For refrac<strong>to</strong>ry cases, consider surgeryConsider surgical removal of the tendervestibule if all other therapies fail <strong>to</strong> provideadequate relief. Surgery for this indicationhas a high success rate (TABLE 2). 7Some surgeons have attempted treatmentwith laser ablation, but most havefound excision more satisfac<strong>to</strong>ry, withfaster recovery and excellent cosmesis.Schneider and colleagues 8 had 69women complete a questionnaire 6 monthsafter surgery, 54 (78%) of whom replied.Moderate <strong>to</strong> excellent improvement wasreported by 45 women (83%); 7 had repeatsurgery, after which 4 improved.❚ Pigmented <strong>lesions</strong>Are they cancer precursors?Precursors of malignant melanoma of theFAST TRACKHallmark ofvestibulitis: Severepain on <strong>to</strong>uch,with tendernesslocalized withinthe vestibulein a horseshoepatternWEB RELATEDSee the Web version of this articleat www.obgmanagement.comfor a list of selected foodsand their oxalate contentwww.obgmanagement.com December 2006 • OBG MANAGEMENT 73

FIGURE 3Vestibular adenitisIntense erythema at the 5 o’clockposition in the vestibule.FIGURE 4Basal cell carcinoma<strong>An</strong> uncommon type of <strong>vulvar</strong> cancer,this tumor rarely metastasizes.Assessing malignant potentialOnly a small number of dysplastic neviprogress <strong>to</strong> malignant melanoma, but thefrequency increases when the dysplasticnevus is familial and not acquired.In general, the more severe the dysplasia,the greater the likelihood it willprogress <strong>to</strong> malignancy. In dysplasticnevi, the pattern and appearance of themelanocytic cells are atypical. Bridging ofmelanocytic clusters of atypical cells mayoccur. Often, the atypical melanocytes arevaried in size and shape, increasing in celland nuclear size as severity increases. Inthe most severe cases, nucleoli are veryprominent.Many pigmented <strong>lesions</strong> of the vulvaare lentigines, similar <strong>to</strong> freckles. Distinguishingone pigmented lesion fromanother is difficult even with magnification,and the clinician often must decidewhether or not <strong>to</strong> biopsy. One set of<strong>guide</strong>lines recommends excisional biopsyof <strong>vulvar</strong> nevi when there is a change in:• surface area of the nevus,• elevation of a lesion, ie, it becomesraised, thickened, or nodular,• surface, from smooth <strong>to</strong> scalyor ulcerated, or• sensation, including itching or tingling. 10Note that a reddish lesion may bebasal cell hyperplasia, which has beenassociated with the development of basalcell carcinoma (FIGURE 4).FAST TRACKVIN <strong>lesions</strong>are hyper- orpseudopigmentedin about 30%of casesvulva have yet <strong>to</strong> be clearly defined. Themajority of these melanomas appear <strong>to</strong>arise de novo; however, some are associatedwith precursor nevi, especially junctionalnevi. The 3 most common types of nevithat appear on the vulva are:• Junctional—located in the basal layer;most likely <strong>to</strong> develop in<strong>to</strong> melanoma.• Compound—melanocytes at the epidermal–dermalinterface and withinthe dermal layer.• Intradermal—Compound nevus whenneval cells in the junctional zone cease<strong>to</strong> be active. Intradermal nevi have lowmalignant potential.❚ Premalignant <strong>lesions</strong>of squamous epitheliumThe variable appearance of <strong>vulvar</strong>intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) necessitatesthe liberal use of diagnostic biopsies,particularly when <strong>lesions</strong> persist orrecur. VIN can present as a white lesion,or as pseudopigmented, pink, or raisedand eroded.Cigarette smoking is a risk fac<strong>to</strong>r.Clinical appearanceMacroscopically, VIN <strong>lesions</strong> are oftenmultiple and appear slightly raised andpapular. Hyper- or pseudopigmented<strong>lesions</strong> are seen in about 30% of cases.A confluence of VIN can create anappearance of diffuse plaques. In VIN, asfor CIN, carcinoma in situ involves a fullthicknessabnormality.TerminologyIf the abnormal parabasal layer extends <strong>to</strong>one half <strong>to</strong> two thirds of the epithelium,moderate dysplasia is present. A lowerdegree of involvement is called mild dysplasia,and full-thickness involvement issevere dysplasia or carcinoma in situ.High rate of persistence, recurrenceHerod and colleagues 9 reported on a 15-year follow-up of VIN and found that dis-74 OBG MANAGEMENT • December 2006

<strong>Noninvasive</strong> <strong>vulvar</strong> <strong>lesions</strong>: <strong>An</strong> <strong>illustrated</strong> <strong>guide</strong>▲FIGURE 5VIN III <strong>lesions</strong>: A trio of presentationsWhite lesion. Pseudopigmented <strong>lesions</strong>. Pink lesion.ease persisted or recurred in 48% ofwomen managed surgically, and 7% ofpatients progressed <strong>to</strong> frankly invasive carcinoma.These investiga<strong>to</strong>rs used the followingclassification system:• VIN I—mild dysplasia (formerly mildatypia)• VIN II—moderate dysplasia (formerlymoderate atypia)• VIN III—severe dysplasia (formerlysevere atypia)• VIN IV—carcinoma in situJoura et al 10 strongly suggested that theincidence of this condition is increasing,especially in women prior <strong>to</strong> the 7thdecade of life. Whether this increase is due<strong>to</strong> better recognition or a true rise in prevalencehas been debated.Diagnostic strategiesApplication of 5% acetic acid <strong>to</strong> the <strong>vulvar</strong>skin will, after 3 <strong>to</strong> 5 minutes, allow areasof involvement <strong>to</strong> be readily seen with ahandheld magnifying glass. Colposcopycan be used, but is slower and not as efficientas a simple magnifying lens. Most clinicianshave abandoned the use of <strong>to</strong>luidineblue <strong>to</strong> identify multicentric <strong>lesions</strong>, sinceacetic acid appears <strong>to</strong> be less cumbersomeand just as efficient.White or pseudopigmented <strong>lesions</strong>(FIGURE 5) can be seen anywhere on thevulva and represent 2 of the 3 presentationsof VIN. Pink <strong>lesions</strong> (FIGURE 5) are usuallyseen on moist surfaces near mucous membranes,whereas the white or pseudopigmented<strong>lesions</strong> are usually seen on thedrier, hair-bearing areas of the vulva.Biopsy reveals similar his<strong>to</strong>logy.The cause of the pseudopigmented<strong>lesions</strong> is unclear, but is unrelated <strong>to</strong> a disturbanceof the melanin cells. As withother <strong>vulvar</strong> <strong>lesions</strong>, biopsy is essential fora correct diagnosis.Recommended therapiesVIN is treated by destroying or excisingthe epithelium involved. When the area islimited in size, simple excision or laservaporization is preferred. A 2- <strong>to</strong> 3-mmmargin is adequate, because these <strong>lesions</strong>have sharp borders.Laser therapy warrants extra care becausethe epithelium is rarely thicker than 0.5mm. For this reason, vaporization of thevulva should be limited <strong>to</strong> the followingdepths:• Labia minora (hair-free): 0.5 mm• Labia majora (hair-containing): 1.5 <strong>to</strong>2 mmThese limits will speed healing andprevent the unnecessary destruction ofdermis.Also be aware that the depth of hairfollicleinvolvement rarely exceeds 1 mm.Vaporization of the full thickness of thedermis will lead <strong>to</strong> alopecia and <strong>vulvar</strong>dryness.When disease is multifocal or confluent, treatmentis more challenging. Several decadesFAST TRACKBiopsy is essentialfor correctdiagnosis of <strong>vulvar</strong>intraepithelialneoplasiawww.obgmanagement.com December 2006 • OBG MANAGEMENT 75

▲<strong>Noninvasive</strong> <strong>vulvar</strong> <strong>lesions</strong>: <strong>An</strong> <strong>illustrated</strong> <strong>guide</strong>FIGURE 6Paget disease: Not just a breast complaintPaget disease of the nipple withunderlying ductal adenocarcinoma.Vulvar Paget disease: lesion (left) and pho<strong>to</strong>micrograph of the lesion.FAST TRACKPaget’s diseaseof the vulva oftenrecurs, especiallywhen the initiallesion is largeago, simple vulvec<strong>to</strong>my was performed, butthe patient was left a sexual cripple.Since then, laser therapy has beenattempted in these cases, and has proved<strong>to</strong> be effective when the area treated doesnot exceed 25% of the <strong>to</strong>tal area of thevulva. Extensive laser therapy leads <strong>to</strong>considerable pos<strong>to</strong>perative pain and anunhappy result.Extensive involvementmay necessitatelaser treatment by quadrant <strong>to</strong> achievethe best results. <strong>An</strong>other option is “skinningvulvec<strong>to</strong>my” using a skin graft. Thisprocedure, first described by FelixRutledge, 11 requires a 7- or 8-day hospitalization,but allows for complete therapyin 1 session.❚ Paget’s disease of the vulvaThis disease is most frequently seen in thebreast nipple (FIGURE 6), where it is usuallyassociated with an underlying infiltratingductal carcinoma. Extramammary sitesinclude the <strong>vulvar</strong>, perianal, and axillaryregions. The disease has also been seen inthe ear canal.Paget’s disease is an intraepithelial adenocarcinomaof eccrine or apocrine origin.Clinical appearancePaget’s disease of the vulva appears as asuperficial, red <strong>to</strong> pink, velvety, eczema<strong>to</strong>idlesion (FIGURE 6), which is very pruritic andoften associated with exfoliation. Marginsare difficult <strong>to</strong> identify grossly.On rare occasions, a nodular tumorcan be found in the middle of the skininvolvement, but in most cases no invasivemalignancy is found at extramammarysites on the vulva.Diagnostic strategiesMicroscopic appearance of Paget cells(FIGURE 6) are pathognomonic of thedisease.Older textbooks suggest that 10% <strong>to</strong>20% of patients have an associated, underlying,invasive carcinoma of a skinappendage, Bartholin’s gland, urinarytract, or bowel or rectal site, but laterexperience has not confirmed this. Rather,the likelihood of concomitant invasive diseaseis much lower than 10%.Excision is the treatment of choice<strong>An</strong>y attempt <strong>to</strong> achieve negative marginsmust utilize frozen section. Some studieshave suggested that negative margins are notassociated with a reduced rate of recurrence,but these findings have been inconsistent.Recurrence is commonPaget’s disease of the vulva often recurs,especially when the initial lesion is large.Close moni<strong>to</strong>ring will detect these recurrenceswhen they’re quite small and easilyC ONTINUED76 OBG MANAGEMENT • December 2006

<strong>Noninvasive</strong> <strong>vulvar</strong> <strong>lesions</strong>:<strong>An</strong> <strong>illustrated</strong> <strong>guide</strong>▲removed via local excision. Occasionally, theinitial disease is so extensive that skin graftingmay be necessary <strong>to</strong> cover the defect. ■REFERENCES1. Voet RL. Classification of <strong>vulvar</strong> dystrophies and premalignantsquamous <strong>lesions</strong>. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:86–90.2. Lorenz B, Kaufman RH, Kutzner SK. Lichen sclerosus. Therapywith clobetasol propionate. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:790–794.3. Proceedings of the XVth World Congress. International Societyfor the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease, Santa Fe, NM;September 26–30, 1999. International Society for the Study ofVulvovaginal Disease Newsletter, Summer 2000.4. Masheb RM, Nash JM, Brondolo E, Kerns RD. Vulvodynia: anintroduction and critical review of a chronic pain condition.Pain. 2000;86–93.5. Sadownik A. Clinical profile of vulvodynia patients. J ReprodMed. 2000;45:679–684.6. Edwards A, Wojnarowska F. The <strong>vulvar</strong> pain syndromes. Int JSTD AIDS. 1998;9:74–78.7. Bornstein J, Zarfati D, Goldik Z, Abramovici H. Vulvar vestibulitis:physical or psychosexual problem? Obstet Gynecol.1999;93(5 Pt 2):876–880.8. Schneider D, Yaron M, Bukovsky I, Soffer Y, Halpern R.Outcome of surgical treatment for superficial dyspareunia from<strong>vulvar</strong> vestibulitis. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:227–231.9. Herod JJ, Shafi MI, Rollason TP, Jordan JA, Luesley DM. Vulvarintraepithelial neoplasia: long-term follow-up of treated anduntreated women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:446–452.10. Joura EA, Lösch A, Haider-<strong>An</strong>geler M-G, Breitenecker G,Leodolter S. Trends in <strong>vulvar</strong> neoplasia. J Reprod Med.2000;45:613–615.11. Rutledge F, Sinclair M. Treatment of intraepithelial carcinoma ofthe vulva by skin excision and graft. Am J Obstet Gynecol.1968;102:807–818.12. Bergeron S, Bouchard C, Fortier M, Binik YM, Khalife S. Thesurgical treatment of <strong>vulvar</strong> vestibulitis syndrome: a follow-upstudy. J Sex Marital Ther. 1997;23:317–325.13. Kehoe S, Luesley D. <strong>An</strong> evaluation of modified vestibulec<strong>to</strong>myin the treatment of <strong>vulvar</strong> vestibulitis: preliminary results. ActaObstet Gynecol Scand. 1996;75:676–677.14. Mann MS, Kaufman RH, Brown D Jr, Adam E. Vulvar vestibulitis:significant clinical variables and treatment outcome. ObstetGynecol. 1992;79:122–125.15. Schover LR, Youngs DD, Cannata R. Psychosexual aspects ofthe evaluation and management of <strong>vulvar</strong> vestibulitis. Am JObstet Gynecol. 1992;167:630–636.16. Marinoff SC, Turner ML. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: anoverview. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:1228–1233.17. Haefner HK, Collins ME, Davis GD, et al. The vulvodynia <strong>guide</strong>line.J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2005; 9:45–51.The author reports no financial relationships relevant <strong>to</strong> this article.Care <strong>to</strong> commen<strong>to</strong>n an article in this issue?Email us at OBG@dowdenhealth.comOBG MANAGEMENT 79