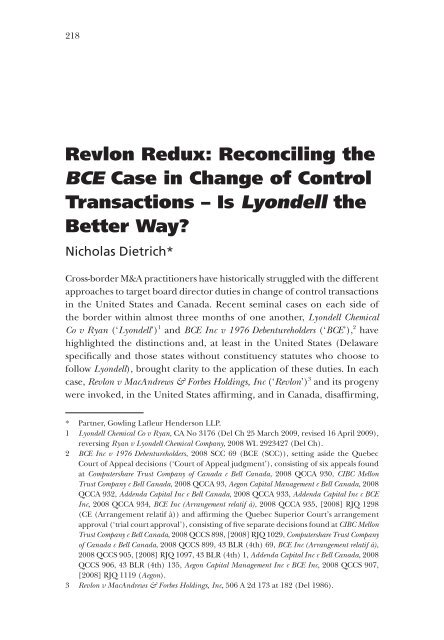

Revlon Redux: Reconciling the BCE Case in Change of ... - Gowlings

Revlon Redux: Reconciling the BCE Case in Change of ... - Gowlings

Revlon Redux: Reconciling the BCE Case in Change of ... - Gowlings

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

218<strong>Revlon</strong> <strong>Redux</strong>: <strong>Reconcil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>BCE</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> ControlTransactions – Is Lyondell <strong>the</strong>Better Way?Nicholas Dietrich*Cross-border M&A practitioners have historically struggled with <strong>the</strong> differentapproaches to target board director duties <strong>in</strong> change <strong>of</strong> control transactions<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States and Canada. Recent sem<strong>in</strong>al cases on each side <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> border with<strong>in</strong> almost three months <strong>of</strong> one ano<strong>the</strong>r, Lyondell ChemicalCo v Ryan (‘Lyondell’) 1 and <strong>BCE</strong> Inc v 1976 Debentureholders (‘<strong>BCE</strong>’), 2 havehighlighted <strong>the</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>ctions and, at least <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States (Delawarespecifically and those states without constituency statutes who choose t<strong>of</strong>ollow Lyondell), brought clarity to <strong>the</strong> application <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se duties. In eachcase, <strong>Revlon</strong> v MacAndrews & Forbes Hold<strong>in</strong>gs, Inc (‘<strong>Revlon</strong>’) 3 and its progenywere <strong>in</strong>voked, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States affirm<strong>in</strong>g, and <strong>in</strong> Canada, disaffirm<strong>in</strong>g,* Partner, Gowl<strong>in</strong>g Lafleur Henderson LLP.1 Lyondell Chemical Co v Ryan, CA No 3176 (Del Ch 25 March 2009, revised 16 April 2009),revers<strong>in</strong>g Ryan v Lyondell Chemical Company, 2008 WL 2923427 (Del Ch).2 <strong>BCE</strong> Inc v 1976 Debentureholders, 2008 SCC 69 (<strong>BCE</strong> (SCC)), sett<strong>in</strong>g aside <strong>the</strong> QuebecCourt <strong>of</strong> Appeal decisions (‘Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal judgment’), consist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> six appeals foundat Computershare Trust Company <strong>of</strong> Canada c Bell Canada, 2008 QCCA 930, CIBC MellonTrust Company c Bell Canada, 2008 QCCA 93, Aegon Capital Management c Bell Canada, 2008QCCA 932, Addenda Capital Inc c Bell Canada, 2008 QCCA 933, Addenda Capital Inc c <strong>BCE</strong>Inc, 2008 QCCA 934, <strong>BCE</strong> Inc (Arrangement relatif à), 2008 QCCA 935, [2008] RJQ 1298(CE (Arrangement relatif à)) and affirm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Quebec Superior Court’s arrangementapproval (‘trial court approval’), consist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> five separate decisions found at CIBC MellonTrust Company c Bell Canada, 2008 QCCS 898, [2008] RJQ 1029, Computershare Trust Company<strong>of</strong> Canada c Bell Canada, 2008 QCCS 899, 43 BLR (4th) 69, <strong>BCE</strong> Inc (Arrangement relatif à),2008 QCCS 905, [2008] RJQ 1097, 43 BLR (4th) 1, Addenda Capital Inc c Bell Canada, 2008QCCS 906, 43 BLR (4th) 135, Aegon Capital Management Inc c <strong>BCE</strong> Inc, 2008 QCCS 907,[2008] RJQ 1119 (Aegon).3 <strong>Revlon</strong> v MacAndrews & Forbes Hold<strong>in</strong>gs, Inc, 506 A 2d 173 at 182 (Del 1986).

<strong>Reconcil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> Control Transactions219<strong>the</strong> paramount pr<strong>in</strong>ciple <strong>of</strong> maximis<strong>in</strong>g shareholder value and obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> best price possible.LyondellThe recently released Delaware Supreme Court decision (decided 25 March2009) reversed on appeal <strong>the</strong> Delaware Court <strong>of</strong> Chancery f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g (‘Lyondelltrial decision’) 4 that <strong>the</strong> target board <strong>of</strong> directors’ ‘unexpla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>action’permitted a reasonable <strong>in</strong>ference that <strong>the</strong> directors may have consciouslydisregarded <strong>the</strong>ir fiduciary duties. The Lyondell trial decision provoked agood deal <strong>of</strong> controversy as it appeared to set a new high watermark fortarget company director duties <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> face <strong>of</strong> a change <strong>of</strong> control transaction,particularly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> a ‘blowout’ <strong>of</strong>fer with a short fuse for acceptance. Inreview<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> record, <strong>the</strong> Delaware Supreme Court concluded that, at most,a triable issue <strong>of</strong> fact might exist as to whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> directors exercised duecare, but <strong>the</strong>re was no evidence on which to <strong>in</strong>fer that <strong>the</strong> directors know<strong>in</strong>glyignored <strong>the</strong>ir responsibilities, <strong>the</strong>reby breach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir duty <strong>of</strong> loyalty. Thedist<strong>in</strong>ction is important because <strong>of</strong> exculpatory or ‘ra<strong>in</strong>coat’ provisions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>Delaware Act, 5 but first some factual background is helpful to set <strong>the</strong> stage.Lyondell Chemical Company was one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> largest <strong>in</strong>dependent publicchemical companies <strong>in</strong> North America with an 11-person board composed<strong>of</strong> Dan Smith (‘Smith’), <strong>the</strong> chairman and CEO, and ten o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>dependentdirectors, many <strong>of</strong> whom were experienced as heads or former heads <strong>of</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r large public companies. Basell AF (‘Basell’), through its <strong>in</strong>directowner, Leonard Blavatnik (‘Blavatnik’), approached Smith <strong>in</strong> April 2006to <strong>in</strong>dicate acquisition <strong>in</strong>terest. This was followed a few months later by aletter to Lyondell’s board suggest<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>of</strong>fer price <strong>of</strong> US$26.50–US$28.50per share. The Lyondell board found <strong>the</strong> price <strong>in</strong>adequate and for <strong>the</strong> nextyear no o<strong>the</strong>r acquirers <strong>in</strong>dicated an <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> Lyondell. However, <strong>in</strong> May2007 ano<strong>the</strong>r Blavatnik company, Access Industries, filed a Schedule 13Dwith <strong>the</strong> Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g its right toacquire an 8.3 per cent block <strong>of</strong> stock and also disclosed Blavatnik’s <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong>potential transactions with Lyondell. This disclosure put <strong>the</strong> company <strong>in</strong> play.The Lyondell board’s response to <strong>the</strong> Schedule 13D fil<strong>in</strong>g was a ‘waitand see’ approach. Shortly <strong>the</strong>reafter, Apollo suggested a managementledleveraged buyout (LBO) to Smith, which was rejected. One monthlater, Basell announced a US$9.6 billion merger with Huntsman but was4 Ryan v Lyondell Chemical Company, 2008 WL 2923427 (Del Ch).5 8 Del Code s 102(b)7, where exculpation for director breach <strong>of</strong> due care, but not duty <strong>of</strong>loyalty, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> certificate <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>corporation, is permitted. In Canada, such exculpation isgenerally not permitted; see Canada Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Corporations Act, RSC 1985, c C-44, s 122(3).

220 Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Law International Vol 10 No 3 September 2009trumped by a Hexion topp<strong>in</strong>g bid, which refocused Blavatnik’s <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong>Lyondell. Blavatnik and Smith met <strong>in</strong> July 2007 to discuss an all-cash bidby Basell at US$40 per share, which was raised to US$44–US$45 per share,and <strong>the</strong>n US$48 per share, as Smith advised Blavatnik to present his best<strong>of</strong>fer before Smith would go to <strong>the</strong> board. The self-trumped best <strong>of</strong>fer<strong>of</strong> US$48 per share was not cont<strong>in</strong>gent on f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g, but came with twostr<strong>in</strong>gs attached: a US$400 million break fee and a short fuse <strong>of</strong> one weekto sign a merger agreement.At <strong>the</strong> Lyondell board meet<strong>in</strong>g on 10 July 2007, which lasted a littleless than an hour, <strong>the</strong> board reviewed valuation material prepared bymanagement and discussed <strong>the</strong> Basell <strong>of</strong>fer, <strong>the</strong> Huntsman merger and<strong>the</strong> likelihood <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r suitors. Smith was <strong>in</strong>structed to secure a written<strong>of</strong>fer and additional f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g details, to which Blavatnik agreed. In <strong>the</strong>meantime, Basell had until 11 July to make a higher bid for Huntsman, whichled Blavatnik to request a firm <strong>in</strong>dication <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest from Lyondell to hiswritten <strong>of</strong>fer by <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> that day. Lyondell’s board met on 11 July 2007,for less than an hour, to consider <strong>the</strong> proposal compared to <strong>the</strong> advantages<strong>of</strong> rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dependent. The board authorised <strong>the</strong> retention <strong>of</strong> DeutscheBank as f<strong>in</strong>ancial adviser and authorised Smith to negotiate. Basell <strong>the</strong>nannounced it would not exercise its bid for Huntsman and <strong>the</strong>ir mergeragreement was term<strong>in</strong>ated.Over <strong>the</strong> next four days, a Lyondell merger agreement was be<strong>in</strong>gnegotiated, due diligence was conducted, a fairness op<strong>in</strong>ion was prepared byDeutsche Bank and <strong>the</strong> board <strong>in</strong>structed Smith to negotiate a higher price,a reduced break fee and a go-shop provision. The Delaware Supreme Courtobserved that <strong>the</strong> trial court noted that Blavatnik was ‘<strong>in</strong>credulous’ about<strong>the</strong>se new demands, but as a sign <strong>of</strong> good faith agreed to drop <strong>the</strong> break feefrom US$400 million to US$385 million.The board met on 16 July 2007 with management, f<strong>in</strong>ancial advisers andlegal advisers, all <strong>of</strong> whom presented reports. In particular, <strong>the</strong> advisersconfirmed that Lyondell would be free pursuant to <strong>the</strong> fiduciary outprovision <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> merger agreement to consider superior proposals, eventhough <strong>the</strong> merger agreement conta<strong>in</strong>ed a no-shop provision. DeutscheBank also op<strong>in</strong>ed that <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>fer price was fair and <strong>in</strong> fact its manag<strong>in</strong>gdirector described it as ‘an absolute home run’. The evidence also showedthat Deutsche Bank believed no one would top <strong>the</strong> Basell bid. Follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>presentations, <strong>the</strong> Lyondell board approved <strong>the</strong> merger and recommendedit to <strong>the</strong> stockholders, who approved <strong>the</strong> US$13 billion deal by greater than99 per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> voted shares.The class action compla<strong>in</strong>t alleged that <strong>the</strong> directors breached <strong>the</strong>ir‘fiduciary duties <strong>of</strong> care, loyalty and candour… and… put <strong>the</strong>ir personal

<strong>Reconcil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> Control Transactions221<strong>in</strong>terests ahead <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lyondell stockholders’. 6 Among <strong>the</strong> usual array<strong>of</strong> strike suit criticisms <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>adequate price, self-<strong>in</strong>terest, flawed process,unreasonable deal protection and disclosure omissions, <strong>the</strong> trial court foundfault only with process and deal protection. The Delaware Supreme Courtconcluded that <strong>the</strong>se two residual claims were really two aspects <strong>of</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gleclaim under <strong>Revlon</strong>, namely that ‘<strong>the</strong> directors failed to obta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best price<strong>in</strong> sell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> company’, 7 and that ‘<strong>Revlon</strong> did not create any new fiduciaryduties’. The court also agreed with <strong>the</strong> trial court that <strong>the</strong> ‘board mustperform its fiduciary duties <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> service <strong>of</strong> a specific objective: maximis<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> sale price <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> enterprise’. 8Although <strong>the</strong> trial court <strong>in</strong> review<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> record concluded that Ryanmight prevail at trial on a director breach <strong>of</strong> duty <strong>of</strong> care, Lyondell’scharter exculpated <strong>the</strong> directors from liability for a breach <strong>of</strong> duty <strong>of</strong> care.Accord<strong>in</strong>gly, <strong>the</strong> Delaware Supreme Court concluded: ‘This case turns onwhe<strong>the</strong>r any arguable shortcom<strong>in</strong>gs on <strong>the</strong> part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lyondell directorsalso implicate <strong>the</strong>ir duty <strong>of</strong> loyalty, a breach <strong>of</strong> which is not exculpated.’ 9The Delaware Supreme Court went on to say: ‘Because <strong>the</strong> trial courtdeterm<strong>in</strong>ed that <strong>the</strong> board was <strong>in</strong>dependent and was not motivated byself-<strong>in</strong>terest or ill will, <strong>the</strong> sole issue is whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> directors are entitled tosummary judgment on <strong>the</strong> claim that <strong>the</strong>y breached <strong>the</strong>ir duty <strong>of</strong> loyalty byfail<strong>in</strong>g to act <strong>in</strong> good faith.’ 10The Delaware Supreme Court summoned its exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> notion<strong>of</strong> ‘good faith’ <strong>in</strong> In re The Walt Disney Co Deriv Litig (‘Disney’) 11 and <strong>in</strong> Stone vRitter (‘Stone’). 12 For <strong>the</strong> purposes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lyondell appeal, <strong>the</strong> court drew nodist<strong>in</strong>ction between bad faith and <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> good faith. It cited Disneyto disavow any attempt to provide a comprehensive or exclusive def<strong>in</strong>ition6 Note 1 above, at 8.7 Ibid, at 9.8 Ibid. From Malpiede v Townson, 780 A 2d 1075 at 1083 (Del 2000). This description <strong>of</strong>fiduciary duties is clearly at odds with <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> Canada’s approach <strong>in</strong> <strong>BCE</strong>,which is explored later <strong>in</strong> this article.9 Lyondell, ibid.10 Ibid. See also Gantler v Stephens, 2009 WL 188828 (Del), (‘Gantler’), where <strong>the</strong> DelawareSupreme Court recently affirmed that <strong>of</strong>ficers owe <strong>the</strong> same duties as directors and, moreimportantly for present purposes, denied shelter under <strong>the</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess judgment rule where<strong>the</strong> pled facts <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>the</strong> chair’s failure to respond to due diligence requests from apotential bidder (who would have term<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>the</strong> board on successful acquisition), and<strong>the</strong> fact that two o<strong>the</strong>r directors provided services to <strong>the</strong> target which were likely to beterm<strong>in</strong>ated on successful completion <strong>of</strong> a merger. Accord<strong>in</strong>gly, <strong>the</strong> standard to be appliedto this non-<strong>in</strong>dependent board’s actions was entire fairness (<strong>in</strong>vok<strong>in</strong>g critical review <strong>of</strong> fairdeal<strong>in</strong>g and fair price), not <strong>the</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess judgment rule (customary deference to directordecisions). See also n 36 below.11 906 A 2d 27 (Del 2006).12 911 A 2d 962 (Del 2006).

222Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Law International Vol 10 No 3 September 2009<strong>of</strong> ‘bad faith’ and recalled its dicta <strong>in</strong> Disney that bad faith could encompassnot only <strong>in</strong>tentional harm (subjective bad faith) but also <strong>in</strong>tentionaldereliction <strong>of</strong> duty (conscious disregard for one’s responsibilities). Lack<strong>of</strong> due care (action taken solely by reason <strong>of</strong> gross negligence withoutmalevolent <strong>in</strong>tent), however, would not constitute bad faith. The court citedStone as authority that <strong>the</strong> standard articulated <strong>in</strong> In re Caremark Int’l DerivLitig 13 (susta<strong>in</strong>ed or systemic failure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> board to exercise oversight isnecessary to establish ‘lack <strong>of</strong> good faith’) was consistent with <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition<strong>of</strong> ‘bad faith’ <strong>in</strong> Disney. The court fur<strong>the</strong>r stated that Stone also ‘clarifiedany possible ambiguity about <strong>the</strong> directors’ mental state, hold<strong>in</strong>g thatimposition <strong>of</strong> liability requires a show<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> directors knew that <strong>the</strong>ywere not discharg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir fiduciary obligations’. 14As it happened, <strong>the</strong> Delaware Supreme Court acknowledged that <strong>the</strong>Court <strong>of</strong> Chancery recognised <strong>the</strong> appropriate legal pr<strong>in</strong>ciples. However,<strong>the</strong> trial court denied grant<strong>in</strong>g summary judgment so that it could obta<strong>in</strong> acomplete record prior to decid<strong>in</strong>g whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> Lyondell directors acted <strong>in</strong>bad faith. This deferment, while appropriate <strong>in</strong> order to expand <strong>the</strong> record<strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> circumstances, was found by <strong>the</strong> appeal court to be <strong>in</strong>appropriate<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se circumstances because <strong>of</strong> three factors contribut<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> trialcourt’s mistake:‘First, <strong>the</strong> trial court imposed <strong>Revlon</strong> duties on <strong>the</strong> Lyondell directors before<strong>the</strong>y had decided to sell, or before <strong>the</strong> sale had become <strong>in</strong>evitable. Second,<strong>the</strong> court read <strong>Revlon</strong> and its progeny as creat<strong>in</strong>g a set <strong>of</strong> requirements thatmust be satisfied dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> sale process. Third, <strong>the</strong> trial court equatedan arguably imperfect attempt to carry out <strong>Revlon</strong> duties with a know<strong>in</strong>gdisregard <strong>of</strong> one’s duties that constitutes bad faith.’ 15On <strong>the</strong> first factor, <strong>the</strong> appeal court found that <strong>the</strong> trial court’s imposition<strong>of</strong> <strong>Revlon</strong> duties, after <strong>the</strong> Schedule 13D fil<strong>in</strong>g effectively put <strong>the</strong> company<strong>in</strong> play, was mistimed. ‘The duty to seek <strong>the</strong> best available price appliesonly when a company embarks on a transaction – on its own <strong>in</strong>itiative or <strong>in</strong>response to an unsolicited <strong>of</strong>fer – that will result <strong>in</strong> a change <strong>of</strong> control.’ 16Accord<strong>in</strong>gly, <strong>the</strong> trial court’s criticism <strong>of</strong> director <strong>in</strong>action follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>Schedule 13D fil<strong>in</strong>g as ‘slothful <strong>in</strong>difference’ while know<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> company was<strong>in</strong> play was <strong>in</strong>sufficient to warrant denial <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lyondell directors’ motion13 698 A 2d 959 at 971 (Del Ch 1996).14 Note 1 above, at 11.15 Ibid, at 12.16 Ibid, at 15, cit<strong>in</strong>g In re Santa Fe Pac Corp S’holder Litig, 669 A 2d 59 at 71 (Del 1995) asauthority.

<strong>Reconcil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> Control Transactions223for summary judgment. 17 A ‘wait and see’ approach was found to be entirelyappropriate under <strong>the</strong> circumstances.On <strong>the</strong> second factor, <strong>the</strong> appeal court found that <strong>the</strong> trial court’sscepticism about <strong>the</strong> good faith <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> directors based on <strong>the</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g record,and based on <strong>the</strong> trial court’s read<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>Revlon</strong> and its progeny that a specificcourse <strong>of</strong> action must be taken, was misplaced:‘There is only one <strong>Revlon</strong> duty – to [get] <strong>the</strong> best price for <strong>the</strong> stockholdersat a sale <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> company. No court can tell directors exactly how toaccomplish that goal, because <strong>the</strong>y will be fac<strong>in</strong>g a unique comb<strong>in</strong>ation<strong>of</strong> circumstances, many <strong>of</strong> which will be outside <strong>the</strong>ir control. As we noted<strong>in</strong> Barkan v Amsted Industries, Inc, <strong>the</strong>re is no s<strong>in</strong>gle bluepr<strong>in</strong>t that a boardmust follow to fulfill its duties.’ 18While <strong>the</strong> trial court found that <strong>the</strong> directors had not sufficiently establishedthat <strong>the</strong>ir ‘impeccable knowledge’ excused <strong>the</strong> failure to conduct an auctionor a market check, <strong>the</strong> appeal court held o<strong>the</strong>rwise, but with a caveat:‘we would not question <strong>the</strong> trial court’s decision to seek additionalevidence if <strong>the</strong> issues were whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> directors had exercised due care.Where, as here, <strong>the</strong> issue is whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> directors failed to act <strong>in</strong> goodfaith, <strong>the</strong> analysis is very different, and <strong>the</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g record mandates <strong>the</strong>entry <strong>of</strong> judgment <strong>in</strong> favor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> directors.’ 19S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> appeal court had already op<strong>in</strong>ed that <strong>Revlon</strong> duties do not <strong>in</strong>vokeany legally prescribed steps, it was a small jump to conclude:‘<strong>the</strong> failure to take any specific steps dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> sale process could nothave demonstrated a conscious disregard <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir duties. More importantly,<strong>the</strong>re is a vast difference between an <strong>in</strong>adequate or flawed effort to carryout fiduciary duties and a conscious disregard for those duties.’ 20This comment from <strong>the</strong> appeal court segues <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> third factor. Cit<strong>in</strong>gParamount for <strong>the</strong> proposition that ‘reasonableness not perfection’ is <strong>the</strong>standard required <strong>in</strong> director decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g and cit<strong>in</strong>g In re Lear CorpS’holder Litig, 21 for <strong>the</strong> proposition that it requires an extreme set <strong>of</strong> facts to17 Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, <strong>the</strong> fil<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> a Schedule 13D <strong>in</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> did provoke full <strong>Revlon</strong> mode <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>ds<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> directors who determ<strong>in</strong>ed that a sale <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> company was <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation.18 Note 1 above, at 16. See also note 28 at p 16 <strong>of</strong> Lyondell, which surveys a number <strong>of</strong> issuesand cases: market checks (Barkan v Amsted Industries, Inc, 567 A 2d 1279 at 1286 (Del 1989)),no-shops (Paramount Communications, Inc v QVC Network, Inc, 637 A 2d 34 at 49 (Del 1994)),and failure to consider strategic buyers (In re Netsmart Technologies, Inc S’holders Litig, 924 A2d 171 at 199 (Del Ch 2007)).19 Note 1 above, at 17.20 Ibid, at 18.21 2008 WL 4053221 (Del Ch).

224 Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Law International Vol 10 No 3 September 2009susta<strong>in</strong> disloyalty based on dis<strong>in</strong>terested directors <strong>in</strong>tentionally disregard<strong>in</strong>gduties, <strong>the</strong> appeal court held:‘if <strong>the</strong> directors failed to do all that <strong>the</strong>y should have under <strong>the</strong>circumstances, <strong>the</strong>y breached <strong>the</strong>ir duty <strong>of</strong> care. Only if <strong>the</strong>y know<strong>in</strong>glyand completely failed to undertake <strong>the</strong>ir responsibilities would <strong>the</strong>y breach<strong>the</strong>ir duty <strong>of</strong> loyalty. The trial court approached <strong>the</strong> record from <strong>the</strong> wrongperspective. Instead <strong>of</strong> question<strong>in</strong>g whe<strong>the</strong>r dis<strong>in</strong>terested, <strong>in</strong>dependentdirectors did everyth<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong>y (arguably) should have done to obta<strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> best sale price, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>quiry should have been whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>se directorsutterly failed to attempt to obta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best sale price.’ 22The Delaware Supreme Court <strong>in</strong> Lyondell has clearly affirmed <strong>the</strong> objective<strong>of</strong> target board directors maximis<strong>in</strong>g shareholder value and obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>best sale price available, and it has clarified when exactly that objectivemust be pursued (not simply when a company is <strong>in</strong> play, but ra<strong>the</strong>r whenembark<strong>in</strong>g on or respond<strong>in</strong>g to events lead<strong>in</strong>g to a change <strong>of</strong> control). Ithas also brightened <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e between <strong>the</strong> duty <strong>of</strong> care (implicat<strong>in</strong>g as it doesgross negligence without conscious or culpable <strong>in</strong>tent), and <strong>the</strong> duty <strong>of</strong> loyalty(implicat<strong>in</strong>g as it does bad faith or <strong>the</strong> failure to act <strong>in</strong> good faith). TheSupreme Court <strong>of</strong> Canada <strong>in</strong> <strong>BCE</strong>, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, disaffirmed <strong>the</strong> pursuit<strong>of</strong> maximis<strong>in</strong>g shareholder value as <strong>the</strong> sole objective and arguably blurred<strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e for target board director duties <strong>in</strong> change <strong>of</strong> control transactions.<strong>BCE</strong>It is fair to say that <strong>the</strong> reasons <strong>in</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> delivered by <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court <strong>of</strong>Canada on 19 December 2008, six months almost to <strong>the</strong> day after <strong>the</strong> tersejudgment allow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> appeals and dismiss<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> cross appeals, surprisedmore than a few observers who had assumed that <strong>the</strong> summary judgment(prior to receiv<strong>in</strong>g written reasons) meant that <strong>Revlon</strong> was good law <strong>in</strong> Canada.Any such illusion was shattered when <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court framed <strong>the</strong> issue:‘On <strong>the</strong>se appeals, it was suggested on behalf <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporations that<strong>the</strong> “<strong>Revlon</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e” <strong>of</strong> cases from Delaware support <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple that where22 Note 1 above, at 19.

<strong>Reconcil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> Control Transactions225<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> shareholders conflict with <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> creditors, <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> shareholders should prevail.’ 23and asserted:‘There is no pr<strong>in</strong>ciple that one set <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests – for example <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests<strong>of</strong> shareholders – should prevail over ano<strong>the</strong>r set <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests. Everyth<strong>in</strong>gdepends on <strong>the</strong> particular situation faced by <strong>the</strong> directors and whe<strong>the</strong>r,hav<strong>in</strong>g regard to that situation, <strong>the</strong>y exercise bus<strong>in</strong>ess judgment <strong>in</strong> aresponsible way.’ 24with a fur<strong>the</strong>r nail <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Revlon</strong> c<strong>of</strong>f<strong>in</strong>:‘What is clear is that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Revlon</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> cases has not displaced <strong>the</strong>fundamental rule that <strong>the</strong> duty <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> directors cannot be conf<strong>in</strong>ed toparticular priority rules, but is ra<strong>the</strong>r a function <strong>of</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess judgment23 Note 2 above, at para 85. It is unfortunate that <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> Canada, <strong>in</strong> com<strong>in</strong>gto this conclusion, did not <strong>the</strong>refore attempt to dist<strong>in</strong>guish earlier decisions <strong>in</strong> Canadawhich appeared to adopt <strong>Revlon</strong>. See for example Re CW Sharehold<strong>in</strong>gs Inc and WIC WesternInternational Communications Ltd et al (1998) 39 OR (3d) 755 (SC) at paras 41 and 42:‘The law as it relates to <strong>the</strong> general duties <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> directors <strong>of</strong> Canadian corporations isnot controversial. The directors must exercise <strong>the</strong> common law fiduciary and statutoryobligation (a) to act honestly and <strong>in</strong> good faith with a view to <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>corporation, and (b) <strong>in</strong> do<strong>in</strong>g so, to exercise <strong>the</strong> care, diligence and skill that a reasonablyprudent person would exercise <strong>in</strong> comparable circumstances: see <strong>the</strong> Canada Bus<strong>in</strong>essCorporations Act. In <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> a hostile take-over bid situation where <strong>the</strong> corporationis ‘<strong>in</strong> play’ (ie where it is apparent <strong>the</strong>re will be a sale <strong>of</strong> equity and/or vot<strong>in</strong>g control)<strong>the</strong> duty is to act <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shareholders as a whole and to take active andreasonable steps to maximise shareholder value by conduct<strong>in</strong>g an auction. As CallaghanACJHC said <strong>in</strong> Corona M<strong>in</strong>erals Corp v CSA Management Ltd (1989) 68 OR (2d) 425 at 429:“The purpose <strong>of</strong> an auction <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> securities <strong>in</strong>dustry is to try and achieve <strong>the</strong> highestvalue for <strong>the</strong> shareholders <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> target companies for <strong>the</strong>ir shares. That <strong>in</strong> my view is anacceptable purpose …”In <strong>the</strong> American authorities this shareholder maximization-through-auction duty is knownas <strong>the</strong> “<strong>Revlon</strong> Duty”, based on <strong>the</strong> decision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Delaware Supreme Court <strong>in</strong> <strong>Revlon</strong> Inc vMacAndrews & Forbes Hold<strong>in</strong>gs, 506 A 2d 173 (1986). At p 182 <strong>of</strong> that report, <strong>the</strong> court said:“The duty <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> board had thus changed from <strong>the</strong> preservation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Revlon</strong> as a corporateentity to <strong>the</strong> maximisation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> company’s value at a sale for <strong>the</strong> stockholders’ benefit.This significantly altered <strong>the</strong> board’s responsibilities … <strong>the</strong> directors’ role changed fromdefenders <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporate bastion to auctioneers charged with gett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> best price for<strong>the</strong> stockholders at a sale <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> company.”The directors, moreover, are obliged to exercise <strong>the</strong>se duties and carry out <strong>the</strong> maximisationprocess <strong>in</strong> a fashion which takes <strong>in</strong>to account – and m<strong>in</strong>imises, to <strong>the</strong> fullest extentreasonably possible – <strong>the</strong> conflict <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest which is <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> position <strong>in</strong> which<strong>the</strong>y f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong>mselves. The company for which <strong>the</strong>y are responsible is under attack. Thereis a natural tendency to be defensive. More importantly, <strong>the</strong>re is a natural tendency toprotect <strong>the</strong>ir own position <strong>of</strong> management and control. Jobs and careers are at stake.’24 Note 2 above, at para 84.

226 Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Law International Vol 10 No 3 September 2009<strong>of</strong> what is <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> particularsituation it faces.’ 25Ah yes, <strong>the</strong> illusive pursuit <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> illusive ‘best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation’!A fair question is whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>BCE</strong> and its ‘best <strong>in</strong>terests’ analysis leaves anyscope at all to come to a similar conclusion to where <strong>the</strong> application<strong>Revlon</strong> might have led? As with <strong>the</strong> Lyondell analysis, <strong>the</strong> answer to thatquestion requires some factual background before engag<strong>in</strong>g fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>that illusive quest.The appeals <strong>in</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> arose out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pursuit <strong>of</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> Inc by a private equityconsortium led by Ontario Teachers Pension Plan Board (‘Teachers’) <strong>in</strong>an LBO required to be f<strong>in</strong>ancially supported by Bell Canada, <strong>the</strong> whollyowned operat<strong>in</strong>g subsidiary <strong>of</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> Inc. 26 Bell Canada’s debenture-holdersopposed <strong>the</strong> change <strong>of</strong> control transaction primarily on <strong>the</strong> basis that <strong>the</strong>debt assumption would lead to credit rat<strong>in</strong>gs downgrades, which <strong>in</strong> turnwould lead to a reduction <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> trad<strong>in</strong>g value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir bonds. Their legalchallenge was framed <strong>in</strong> accordance with <strong>the</strong> legal form <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> acquisition,namely <strong>the</strong>ir stand<strong>in</strong>g at <strong>the</strong> court-required approval <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> transactionvia a plan <strong>of</strong> arrangement pursuant to section 192 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Canada Bus<strong>in</strong>ess25 Note 2 above, at para 87. The Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> Canada took some comfort for this positionby cit<strong>in</strong>g former Delaware Supreme Court Chief Justice Veasey (‘Veasey’):‘In a review <strong>of</strong> trends <strong>in</strong> Delaware corporate jurisprudence, former Delaware SupremeCourt Chief Justice E Norman Veasey put it this way:“[It] is important to keep <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> precise content <strong>of</strong> this ‘best <strong>in</strong>terests’concept – that is, to whom this duty is owed and when. Naturally, one <strong>of</strong>ten th<strong>in</strong>ksthat directors owe this duty to both <strong>the</strong> corporation and <strong>the</strong> stockholders. Thatformulation is harmless <strong>in</strong> most <strong>in</strong>stances because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> confluence <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests,<strong>in</strong> that what is good for <strong>the</strong> corporate entity is usually derivatively good for <strong>the</strong>stockholders. There are times, <strong>of</strong> course, when <strong>the</strong> focus is directly on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stockholders [ie, as <strong>in</strong> <strong>Revlon</strong>]. But, <strong>in</strong> general, <strong>the</strong> directors owe fiduciaryduties to <strong>the</strong> corporation, not to <strong>the</strong> stockholders. [Emphasis <strong>in</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al.]”(E Norman Veasey with Christ<strong>in</strong>e T Di Guglielmo, ‘What Happened <strong>in</strong> DelawareCorporate Law and Governance from 1992–2004? A Retrospective on Some KeyDevelopments’ (2005) 153 U Pa L Rev 1399 at 1431).’Of course <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> Canada is merely tak<strong>in</strong>g judicial notice <strong>of</strong> Veasey to state<strong>the</strong> obvious, namely that <strong>the</strong> general rule <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g director duties is ‘best <strong>in</strong>terests’, butfails to take <strong>the</strong> next step, pr<strong>in</strong>cipally that <strong>in</strong> a change <strong>of</strong> control situation, <strong>the</strong> focus isdirectly on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stockholders.26 The o<strong>the</strong>r consortium members were Providence Equity Partners Inc and MadisonDearborn Partners, LLC. For <strong>the</strong> purposes <strong>of</strong> its analysis, s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>BCE</strong> Inc and Bell Canadahad <strong>the</strong> same boards <strong>of</strong> directors, <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court found it ‘unnecessary… to dist<strong>in</strong>guishbetween <strong>the</strong> conduct <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> directors <strong>of</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> [Inc], <strong>the</strong> hold<strong>in</strong>g company, and <strong>the</strong> conduct<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> directors <strong>of</strong> Bell Canada’: <strong>BCE</strong>, ibid, at para 33. The writer questions <strong>the</strong> virtue <strong>of</strong>this failure to so dist<strong>in</strong>guish.

<strong>Reconcil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> Control Transactions227Corporations Act (CBCA) 27 argu<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> arrangement should not befound to be fair, and alternatively, pursuant to section 241 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CBCA,argu<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> LBO was ‘oppressive’. The trial court approval found <strong>the</strong>plan <strong>of</strong> arrangement to be fair and dismissed <strong>the</strong> oppression claim. TheCourt <strong>of</strong> Appeal judgment held that <strong>the</strong> plan <strong>of</strong> arrangement had not beenshown to be fair and accord<strong>in</strong>gly found it not necessary to deal with <strong>the</strong>oppression claim. The Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> Canada ultimately concluded that<strong>the</strong> trial judge had not erred <strong>in</strong> approv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> plan <strong>of</strong> arrangement and that<strong>the</strong> debenture-holders had failed to prove oppression.The spotlight on <strong>the</strong> duties <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> directors first arose <strong>in</strong> November2006, when <strong>BCE</strong> Inc became aware that KKR was <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> <strong>BCE</strong>. Thepresident and CEO <strong>of</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> Inc, Michael Sabia (‘Sabia’), <strong>in</strong>formed KKRthat <strong>BCE</strong> Inc had no <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> any transactions with KKR. Rumours arose<strong>in</strong> early 2007 that KKR and Canada Pension Plan Investment Board mightbe <strong>in</strong>itiat<strong>in</strong>g a bid for <strong>BCE</strong> Inc and that Teachers was also <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> apotential transaction. After a <strong>BCE</strong> Inc board meet<strong>in</strong>g, Sabia <strong>in</strong>formed each<strong>of</strong> KKR and Teachers that <strong>BCE</strong> Inc was not <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> a change <strong>of</strong> controltransaction ‘because it was set on creat<strong>in</strong>g shareholder value through <strong>the</strong>execution <strong>of</strong> its 2007 bus<strong>in</strong>ess plan’. 28 After erroneous press reports on29 March 2007, <strong>BCE</strong> Inc was forced to issue a press release stat<strong>in</strong>g that nodiscussions were be<strong>in</strong>g held as to any go<strong>in</strong>g-private transaction. However,follow<strong>in</strong>g a Schedule 13D fil<strong>in</strong>g by Teachers on 9 April 2007, and faced withheightened speculation that <strong>BCE</strong> Inc was <strong>in</strong> play, <strong>the</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> Inc directors metto discuss strategic alternatives with f<strong>in</strong>ancial and legal advisers and decidedthat ‘it would be <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> [Inc] and its shareholders tohave compet<strong>in</strong>g bidd<strong>in</strong>g groups and to guard aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> risk <strong>of</strong> a simplebidd<strong>in</strong>g group assembl<strong>in</strong>g such a significant portion <strong>of</strong> available debt and27 Canada Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Corporations Act, RSC 1985, c C-44. Under Canada’s constitution, unlike<strong>the</strong> US, <strong>the</strong>re is a concurrent federal <strong>in</strong>corporation power with <strong>the</strong> prov<strong>in</strong>ces. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>prov<strong>in</strong>ces have arrangement, oppression (o<strong>the</strong>r than Québec, and <strong>in</strong> British Columbia,only shareholders have stand<strong>in</strong>g) and statutory director duties <strong>of</strong> care and good faithprovisions substantially similar to <strong>the</strong> CBCA. On expressly stated duties, <strong>the</strong>y are similar toModel Act states, which, unlike Delaware, have codified director duties. An ‘arrangement’can be similar to a three-cornered amalgamation <strong>in</strong> Canada, which itself is similar to a USstyleacquisition merger, to effect a takeover, as opposed to a vanilla tender <strong>of</strong>fer <strong>in</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>rCanada or <strong>the</strong> United States. Arrangements have <strong>the</strong> added advantage <strong>in</strong> cross-borderdeals, as judicially approved devices, <strong>of</strong> avoid<strong>in</strong>g comprehensive registration statementfil<strong>in</strong>gs under US securities laws where <strong>the</strong> acquirer is <strong>of</strong>fer<strong>in</strong>g non-cash consideration, and<strong>in</strong> Canada <strong>of</strong> avoid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> need to comply with certa<strong>in</strong> prov<strong>in</strong>cial takeover bid rules (<strong>in</strong>Canada, constitutionally, securities laws are prov<strong>in</strong>cial, not federal). However, follow<strong>in</strong>g<strong>BCE</strong>, takeover architecture will need to reconsider <strong>the</strong> advantages <strong>of</strong> arrangements aga<strong>in</strong>st<strong>the</strong>se additional risks.28 Note 2 above, at para 10. On <strong>the</strong> Lyondell analysis, this would not trigger <strong>Revlon</strong> duties.

228 Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Law International Vol 10 No 3 September 2009equity that <strong>the</strong> group could preclude potential compet<strong>in</strong>g groups fromparticipat<strong>in</strong>g effectively <strong>in</strong> an auction process’. 29 An appropriate press releasewas made on 17 April 2007.Follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> issuance <strong>of</strong> this press release, a number <strong>of</strong> Bell Canadadebenture-holders wrote to <strong>the</strong> board express<strong>in</strong>g concern and seek<strong>in</strong>gassurance that <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>terests would be considered, to which <strong>BCE</strong> Inc repliedthat it ‘<strong>in</strong>tended to honour <strong>the</strong> contractual terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> trust <strong>in</strong>dentures’. 30As it turned out, <strong>the</strong> board got someth<strong>in</strong>g else factually right as well: <strong>in</strong> itsauction bidd<strong>in</strong>g material to prospective acquirers, it apparently stated thatits evaluation <strong>of</strong> compet<strong>in</strong>g bids would consider <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g arrangementimpact on <strong>BCE</strong> Inc and Bell Canada’s debenture-holders, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g respectfor <strong>the</strong> contractual terms.As <strong>the</strong> auction process unfolded, three consortia <strong>of</strong>fers, all contemplat<strong>in</strong>ga considerable amount <strong>of</strong> acquisition debt for which Bell Canada wouldbe liable (likely result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> rat<strong>in</strong>g downgrades), were submitted. TheTeachers’ <strong>of</strong>fer orig<strong>in</strong>ally envisioned an amalgamation (which would havetriggered debenture-holder vot<strong>in</strong>g rights) and at <strong>the</strong> encouragement <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> Inc board, Teachers submitted a revised <strong>of</strong>fer with a structure not<strong>in</strong>vok<strong>in</strong>g a debenture-holder vote, by propos<strong>in</strong>g a plan <strong>of</strong> arrangement,and <strong>in</strong>cidentally rais<strong>in</strong>g its cash bid from C$42.25 to C$42.75 per share(a 40 per cent premium, with Bell Canada guarantee<strong>in</strong>g C$30 billion <strong>of</strong>debt out <strong>of</strong> total capital required <strong>of</strong> C$52 billion). After consideration,and on <strong>the</strong> recommendation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent committee, which hadreceived appropriate fairness op<strong>in</strong>ions relat<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> shareholders (butnot debenture-holders whose rights were viewed as not be<strong>in</strong>g arranged),<strong>the</strong> board found that <strong>the</strong> Teachers’ <strong>of</strong>fer was ‘<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>BCE</strong>and <strong>BCE</strong>’s shareholders’. 31 The def<strong>in</strong>itive agreement was signed on 30 June2007, and shareholder approval <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> arrangement on 21 September 2007was by a majority <strong>of</strong> 97.93 per cent. The ensu<strong>in</strong>g credit rat<strong>in</strong>g downgradeto <strong>the</strong> debentures below <strong>in</strong>vestment grade not only caused a 20 per centtrad<strong>in</strong>g value decl<strong>in</strong>e, it also would cause certa<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional holders29 <strong>BCE</strong>, ibid, at para 13. The board went <strong>in</strong>to classic <strong>Revlon</strong> mode at this po<strong>in</strong>t, creat<strong>in</strong>g an<strong>in</strong>dependent committee to <strong>in</strong>itiate and oversee an auction process and to review ‘strategicalternatives with a view to fur<strong>the</strong>r enhanc<strong>in</strong>g shareholder value’: ibid, at para 14. This wasfollowed on 13 June 2007 with bidd<strong>in</strong>g rules and a general form <strong>of</strong> transaction document toauction participants. The Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal judgment at para 17 affirmed that <strong>the</strong> trial judgefound ‘<strong>the</strong> overrid<strong>in</strong>g objective <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> strategic review and auction process was to maximizeshareholder value, while respect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> corporation’s legal and contractual obligations’.30 Ibid, at para 15. This doesn’t, <strong>of</strong> course, amount to much ‘consideration’ given thatpresumably one must honour contractual commitments <strong>of</strong> any k<strong>in</strong>d under threat <strong>of</strong>suit for breach.31 Ibid, at para 18. The notion <strong>of</strong> ‘best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>BCE</strong>’ (<strong>in</strong> addition to <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong><strong>BCE</strong>’s shareholders) proved prescient: see n 25 above.

<strong>Reconcil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> Control Transactions229subject to credit-rat<strong>in</strong>g restrictions to be obliged to dispose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir hold<strong>in</strong>gs.The debenture-holders opposed <strong>the</strong> plan <strong>of</strong> arrangement on a number <strong>of</strong>grounds <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> trial court, two <strong>of</strong> which survived and were at issue <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>Supreme Court:‘First, <strong>the</strong> debentureholders sought relief under <strong>the</strong> oppressionprovision <strong>in</strong> s 241 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CBCA. Second, <strong>the</strong>y opposed court approval<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> arrangement, as required by s 192 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CBCA, alleg<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong>arrangement was not “fair and reasonable” because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> adverse effecton <strong>the</strong>ir economic <strong>in</strong>terests.’ 32In order to consider <strong>the</strong>se two issues <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> a change <strong>of</strong> controltransaction, <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court felt obliged first to clarify <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong>director duties generally:‘The directors are responsible for <strong>the</strong> governance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation. In<strong>the</strong> performance <strong>of</strong> this role, <strong>the</strong> directors are subject to two duties: afiduciary duty to <strong>the</strong> corporation under s 122(1)(a) (<strong>the</strong> fiduciary duty);and a duty to exercise <strong>the</strong> care, diligence and skill <strong>of</strong> a reasonably prudentperson <strong>in</strong> comparable circumstances under s 122(1)(b) (<strong>the</strong> duty <strong>of</strong> care).The second duty is not at issue <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se proceed<strong>in</strong>gs as this is not a claimaga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> directors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation for fail<strong>in</strong>g to meet <strong>the</strong>ir duty <strong>of</strong>care. However, this case does <strong>in</strong>volve <strong>the</strong> fiduciary duty <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> directors to<strong>the</strong> corporation, and particularly <strong>the</strong> “fair treatment” component <strong>of</strong> thisduty, which, as will be seen, is fundamental to <strong>the</strong> reasonable expectations<strong>of</strong> stakeholders claim<strong>in</strong>g an oppression remedy.’ 33The Supreme Court noted that <strong>the</strong> fiduciary duty arose <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> common lawand equated it with a duty to act <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation. Italso relied on its earlier decision <strong>in</strong> Peoples Department Stores Inc (Trustee <strong>of</strong>) vWise (‘Peoples’) 34 to clarify just what that means:‘Often <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> shareholders and stakeholders are co-extensivewith <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation. But if <strong>the</strong>y conflict, <strong>the</strong> directors’duty is clear – it is to <strong>the</strong> corporation: Peoples Department Stores. Thefiduciary duty <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> directors to <strong>the</strong> corporation is a broad, contextual32 <strong>BCE</strong>, ibid, at para 22.33 Ibid, at para 36. Section 122(1)(a) specifically reads: ‘Every director and <strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> acorporation <strong>in</strong> exercis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir powers and discharg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir duties shall (a) act honestlyand <strong>in</strong> good faith with a view to <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation… .’ This codification<strong>of</strong> fiduciary duty is likely very close to Delaware’s non-codification <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘duty <strong>of</strong> loyalty’at common law.34 Peoples Department Stores Inc (Trustee <strong>of</strong>) v Wise, 2004 SCC 68, [2004] 3 SCR 461. Peoples wasnot a change <strong>of</strong> control case and <strong>the</strong>re has been much speculation on whe<strong>the</strong>r its hold<strong>in</strong>gwas relegated to a distress situation, or had wider applicability, which has now been clarifiedby <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court <strong>in</strong> <strong>BCE</strong>. See also <strong>BCE</strong>, n 2 above, at para 88.

230 Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Law International Vol 10 No 3 September 2009concept. It is not conf<strong>in</strong>ed to short-term pr<strong>of</strong>it or share value. Where <strong>the</strong>corporation is an ongo<strong>in</strong>g concern, it looks to <strong>the</strong> long-term <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> corporation. The content <strong>of</strong> this duty varies with <strong>the</strong> situation at hand.At a m<strong>in</strong>imum, it requires <strong>the</strong> directors to ensure that <strong>the</strong> corporationmeets its statutory obligations. But, depend<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> context, <strong>the</strong>remay also be o<strong>the</strong>r requirements. In any event, <strong>the</strong> fiduciary duty owed bydirectors is mandatory; directors must look to what is <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation.’ 35The Supreme Court did not shy away from <strong>the</strong> obvious question <strong>of</strong> whatspecific <strong>in</strong>terests an amorphous concept such as ‘best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>corporation’ encompasses by suggest<strong>in</strong>g a possible non-exclusive shopp<strong>in</strong>glist:‘In consider<strong>in</strong>g what is <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation, directorsmay look to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong>, <strong>in</strong>ter alia, shareholders, employees, creditors,consumers, governments and <strong>the</strong> environment to <strong>in</strong>form <strong>the</strong>ir decisions.Courts should give appropriate deference to <strong>the</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess judgment <strong>of</strong>directors who take <strong>in</strong>to account <strong>the</strong>se ancillary <strong>in</strong>terests, as reflected by <strong>the</strong>bus<strong>in</strong>ess judgment rule. The “bus<strong>in</strong>ess judgment rule” accords deferenceto a bus<strong>in</strong>ess decision, so long as it lies with<strong>in</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> reasonablealternatives …’ 36In discuss<strong>in</strong>g remedies for director breaches <strong>of</strong> section 122(1) duties, <strong>the</strong>Supreme Court surveyed four <strong>in</strong> particular: directors’ actions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> name35 <strong>BCE</strong>, ibid, at paras 37 and 38.36 Ibid, at para 40. It is fair to say that <strong>the</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess judgment rule receives similar judicialdeference on both sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> US–Canada border: See Paramount’s ‘reasonableness notperfection’ standard, n 18 above, and Gantler, n 10 above, as to when ‘entire fairness’will be applied. In Canada, <strong>the</strong> foundation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess judgment rule <strong>of</strong>ten cited<strong>in</strong> Canadian cases is as enunciated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘Repap case’ (UPM – Kymmene Corp v UPM –Kymmene Miramichi Inc (2002) 27 BLR (3d) 53 (Ont Sup Ct J), aff’d (2004) 42 BLR (3d)34 (Ont CA) at para 153:‘However, directors are only protected to <strong>the</strong> extent that <strong>the</strong>ir actions actuallyevidence <strong>the</strong>ir bus<strong>in</strong>ess judgment. The pr<strong>in</strong>ciple <strong>of</strong> deference presupposes thatdirectors are scrupulous <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir deliberations and demonstrate diligence <strong>in</strong> arriv<strong>in</strong>gat decisions. Courts are entitled to consider <strong>the</strong> content <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir decision and <strong>the</strong>extent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation on which it is based and to measure this aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> facts as<strong>the</strong>y existed at <strong>the</strong> time <strong>the</strong> impugned decision was made. Although Board decisionsare not subject to microscopic exam<strong>in</strong>ation with <strong>the</strong> perfect vision <strong>of</strong> h<strong>in</strong>dsight, <strong>the</strong>yare subject to exam<strong>in</strong>ation.’See also Nicholas Dietrich, ‘The “Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Judgment Rule”: Whose Judgment?’ (2002) 14(4)Corporate Governance Review 7. It is also fair to say that ‘best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation’,as a general pr<strong>in</strong>ciple, whe<strong>the</strong>r express or implied <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> common law, is ano<strong>the</strong>r notionrespected on both sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> border as a general director duty. However, <strong>in</strong> a change <strong>of</strong>control transaction, <strong>Revlon</strong>, as affirmed by Lyondell, narrows that duty to obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> bestprice available. See nn 66 and 67 below.

<strong>Reconcil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> Control Transactions231<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation; civil actions (such as <strong>in</strong> tort) for breaches <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> duty <strong>of</strong>care; oppression actions focus<strong>in</strong>g on harm to <strong>the</strong> legal and equitable <strong>in</strong>terests<strong>of</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> specified stakeholders; and <strong>the</strong> remedial-like aspect <strong>of</strong> requiredcourt approvals <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> cases such as plans <strong>of</strong> arrangement affect<strong>in</strong>gcerta<strong>in</strong> stakeholders’ rights. It was <strong>the</strong> latter two <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se four broad areas<strong>of</strong> remedial action which <strong>the</strong> debenture-holders claims focused on. Thetrial court approval dealt with <strong>the</strong> oppression claim and <strong>the</strong> arrangementclaim as entail<strong>in</strong>g dist<strong>in</strong>ct deliberations and held that <strong>the</strong> debenture-holderswere entitled to nei<strong>the</strong>r remedy. The Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal judgment regarded<strong>the</strong> two remedies as overlapp<strong>in</strong>g, with both grounded on failure to considerdebenture-holder expectations, an approach rejected by <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court,which felt it was necessary to deal with <strong>the</strong>m dist<strong>in</strong>ctly.OppressionThe Supreme Court reviewed <strong>the</strong> two dist<strong>in</strong>ct (strict word<strong>in</strong>g vs broadpr<strong>in</strong>ciple) approaches <strong>in</strong> oppression case law <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g CBCA, s 241(2) 37and adopted a two-prong approach, namely look<strong>in</strong>g first to underly<strong>in</strong>gpr<strong>in</strong>ciples, and specifically ‘<strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> reasonable expectations’. 38 Oncea reasonable expectation is established, <strong>the</strong>n one cont<strong>in</strong>ues to consider‘whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> conduct compla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>of</strong> amounts to “oppression”, “unfairprejudice” or “unfair disregard”… .’ 39 The first enquiry focuses on <strong>the</strong>court’s equitable jurisdiction to determ<strong>in</strong>e not just what is legal, but whatis fair, recognis<strong>in</strong>g that fairness is fact specific and bound by contextualand relationship situations. The issue is not whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> party has an actualexpectation but whe<strong>the</strong>r that expectation is reasonable hav<strong>in</strong>g regard toall <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> facts and circumstances, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>re may beconflict<strong>in</strong>g claims and expectations. It is here <strong>in</strong> its decision where <strong>the</strong>Supreme Court first <strong>in</strong>directly rejects <strong>Revlon</strong>’s s<strong>in</strong>gular focus <strong>in</strong> a change <strong>of</strong>control transaction:‘The corporation and shareholders are entitled to maximize pr<strong>of</strong>it andshare value, to be sure, but not by treat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividual stakeholders unfairly.Fair treatment – <strong>the</strong> central <strong>the</strong>me runn<strong>in</strong>g through <strong>the</strong> oppression37 A court may order remedied action where:‘(a) any act or omission <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation or any <strong>of</strong> its affiliates effects a result,(b) <strong>the</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess or affairs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation or any <strong>of</strong> its affiliates are or have beencarried on or conducted <strong>in</strong> a manner, or(c) <strong>the</strong> powers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> directors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation or any <strong>of</strong> its affiliates are or havebeen exercised <strong>in</strong> a manner that is oppressive or unfairly prejudicial to or that unfairlydisregards <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> any security holder, creditor, director or <strong>of</strong>ficer … .’38 Note 2 above, at para 56.39 Ibid.

232 Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Law International Vol 10 No 3 September 2009jurisprudence – is most fundamentally what stakeholders are entitled to“reasonably expect”.’ 40If <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court had stopped here, one might conclude that somecerta<strong>in</strong>ty could be extricated from <strong>the</strong> dicta <strong>in</strong> that section 241(2) limitsoppression to security holders, creditors, directors and <strong>of</strong>ficers, and <strong>the</strong>reforeconflict<strong>in</strong>g, reasonably held <strong>in</strong>terests among a known universe could besensibly determ<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> a change <strong>of</strong> control transaction. However, <strong>the</strong> courtwent much fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> muddy<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> waters <strong>of</strong> pursuit <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> elusive holygrail <strong>of</strong> ‘best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation’:‘The fact that <strong>the</strong> conduct <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> directors is <strong>of</strong>ten at <strong>the</strong> centre <strong>of</strong>oppression actions might seem to suggest that directors are under adirect duty to <strong>in</strong>dividual stakeholders who may be affected by a corporatedecision. Directors, act<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation,may be obliged to consider <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir decisions on corporatestakeholders, such as <strong>the</strong> debentureholders <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se appeals. This is whatwe mean when we speak <strong>of</strong> a director be<strong>in</strong>g required to act <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> corporation viewed as a good corporate citizen. However, <strong>the</strong> directors owea fiduciary duty to <strong>the</strong> corporation, and only to <strong>the</strong> corporation. Peoplesometimes speak <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> directors ow<strong>in</strong>g a duty to both <strong>the</strong> corporationand to stakeholders. Usually this is harmless, s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> reasonableexpectations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stakeholder <strong>in</strong> a particular outcome <strong>of</strong>ten co<strong>in</strong>cideswith what is <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation. However, cases (such as<strong>the</strong>se appeals) may arise where <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong>terests do not co<strong>in</strong>cide. In such cases, it isimportant to be clear that <strong>the</strong> directors owe <strong>the</strong>ir duty to <strong>the</strong> corporation,not to stakeholders, and that <strong>the</strong> reasonable expectation <strong>of</strong> stakeholdersis simply that <strong>the</strong> directors act <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation.’ 41[Emphasis added.]With <strong>the</strong> greatest respect, it is submitted that <strong>in</strong> a change <strong>of</strong> controltransaction, conflict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> stakeholders, whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y bestockholders, creditors, employees, suppliers, customers or o<strong>the</strong>rs with a‘stake’ <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation, will almost <strong>in</strong>evitably be <strong>in</strong> conflict when facedwith alternative bids whose proponents will almost always have differentpost-clos<strong>in</strong>g plans affect<strong>in</strong>g various stakeholders. One can only imag<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong>difficulties faced by directors attempt<strong>in</strong>g to come to terms with <strong>the</strong> ‘best<strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation’, as well as <strong>the</strong> defensive mischief that might arise<strong>in</strong> a change <strong>of</strong> control transaction <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong> good corporate citizenship.Presumably, this is why <strong>Revlon</strong> and its progeny, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Lyondell, oblige40 Ibid, at para 64.41 Ibid, at para 66.

<strong>Reconcil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>BCE</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> Control Transactions233directors to channel that pursuit towards a s<strong>in</strong>gular objective, maximis<strong>in</strong>gshareholder value.Return<strong>in</strong>g to its specific analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first prong <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oppressionapproach (whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> claimant reasonably held its expectation), <strong>the</strong> courtlisted a non-exclusive list <strong>of</strong> factors to determ<strong>in</strong>e reasonable expectation: (1)commercial practice; (2) nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation; (3) relationships; (4)past practice; (5) preventive steps; (6) representations and agreements, and(7) fair resolution <strong>of</strong> conflict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terests. It is <strong>in</strong> connection with this lastfactor where <strong>the</strong> court aga<strong>in</strong> ventured <strong>in</strong>to ‘corporate citizenship’ territory:‘In each case, <strong>the</strong> question is whe<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>in</strong> all <strong>the</strong> circumstances, <strong>the</strong>directors acted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporation, hav<strong>in</strong>g regardto all relevant considerations, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g, but not conf<strong>in</strong>ed to, <strong>the</strong> needto treat affected stakeholders <strong>in</strong> a fair manner, commensurate with <strong>the</strong>corporation’s duties as a responsible corporate citizen.’ 42It is also <strong>in</strong> connection with this last factor where <strong>the</strong> court expressly rejected<strong>Revlon</strong> shareholder <strong>in</strong>terest paramountcy <strong>in</strong> change <strong>of</strong> control transactions,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Unocal’s 43 overlay to circumstances where <strong>the</strong> objective is not toma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> enterprise but ra<strong>the</strong>r to sell to <strong>the</strong> highest bidder. 44The court <strong>the</strong>n turned its attention to <strong>the</strong> second prong <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oppressionanalysis approach, namely whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> conduct compla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>of</strong> rises to‘oppression’, ‘unfair prejudice’ or ‘unfair disregard’ <strong>of</strong> its claimants’ <strong>in</strong>terests.While acknowledg<strong>in</strong>g that an exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se types <strong>of</strong> conduct wascomplementary to reasonable expectation analysis, and that <strong>the</strong> two prongsmay merge, <strong>the</strong> court felt it was worth not<strong>in</strong>g that ‘as <strong>in</strong> any action <strong>in</strong> equity,wrongful conduct, causation and compensable <strong>in</strong>jury must be established<strong>in</strong> a claim for oppression’. 45 The court also viewed <strong>the</strong> adjectival trilogy <strong>of</strong>prescribed conduct as a cont<strong>in</strong>uum with ‘oppression’ be<strong>in</strong>g viewed as <strong>the</strong>most harsh and abusive, and with ‘unfair disregard’ be<strong>in</strong>g viewed as <strong>the</strong> leastserious wrong. As to ‘unfair prejudice’ rank<strong>in</strong>g somewhere <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> middle,<strong>the</strong> court cited adopt<strong>in</strong>g a ‘poison pill’ to thwart a takeover bid and m<strong>in</strong>oritysqueeze-outs, two features <strong>of</strong>ten seen <strong>in</strong> change <strong>of</strong> control transactions. 46In apply<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> two prongs (reasonable expectation, and if so, violation<strong>of</strong> that expectation by conduct constitut<strong>in</strong>g oppression, unfair prejudiceor unfair disregard) to <strong>the</strong> two aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> debenture-holder oppressionclaims (that <strong>the</strong>y had a reasonable expectation that <strong>the</strong> directors would42 Ibid, at para 82.43 Unocal Corp v Mesa Petroleum Co, 493 A 2d 946 (Del 1985). See <strong>the</strong> additional SupremeCourt’s <strong>Revlon</strong> rejection language, nn 23, 24 and 25 above.44 Note 2 above, at para 86.45 Ibid, at para 90.46 Ibid, at para 93.