Obstetric fistula in tanzania - EngenderHealth

Obstetric fistula in tanzania - EngenderHealth

Obstetric fistula in tanzania - EngenderHealth

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

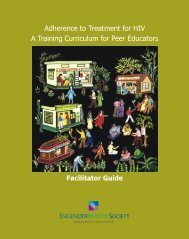

RISK AND RESILIENCE: <strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>fistula</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>tanzania</strong>An Overview of F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs and Recommendations from the StudyThe cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g widespread <strong>in</strong>cidence of obstetric<strong>fistula</strong> is a signal that health and social systems arefail<strong>in</strong>g to meet the basic needs of women. TheWorld Health Organization estimates thatapproximately two million girls and women livewith <strong>fistula</strong> worldwide, and an additional 50,000-100,000 new cases occur each year [1]. In Tanzaniaalone, it is estimated that there are approximately2,500-3,000 new cases of <strong>fistula</strong> each year [2].<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>fistula</strong> is typically seen as a severe anddebilitat<strong>in</strong>g medical condition susta<strong>in</strong>ed dur<strong>in</strong>gchildbirth. However its roots are deeply embedded<strong>in</strong> social, cultural and economic determ<strong>in</strong>ants thatunderlie poverty and vulnerability. Fistula largelyaffects girls and women liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> rural areas, andthose liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> poverty. They often lack access toadequate health services and <strong>in</strong>formation, cannotpay for medical treatment, and are poorlyeducated. Moreover, <strong>fistula</strong> <strong>in</strong>hibits women’s abilityto work and to <strong>in</strong>teract with communities, driv<strong>in</strong>gthem deeper <strong>in</strong>to poverty and further underm<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gtheir economic and social position. Despite thesechallenges, however, girls and women with <strong>fistula</strong>are typically strong and resourceful, cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g tosupport their families and themselves [3].Risk and Resilience: <strong>Obstetric</strong> Fistula <strong>in</strong> Tanzania,exam<strong>in</strong>es the many dimensions of obstetric <strong>fistula</strong>and its related social vulnerability. The study wasconducted by Women’s Dignity Project and<strong>EngenderHealth</strong>, <strong>in</strong> collaboration with HealthAction Promotion Association, Kivul<strong>in</strong>i Women’sRights Organization, and Peramiho MissionHospital. Sixty one Tanzanian women withobstetric <strong>fistula</strong> participated <strong>in</strong> the study, togetherwith members of their families and communities,and local health care providers. This policy brief,the <strong>in</strong>troduction to four thematic briefs, beg<strong>in</strong>swith an explanation of obstetric <strong>fistula</strong> followed byan overview of the research study. The brief thenpresents the key f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from the study togetherwith recommendations on strategies that areurgently required to save women’s lives andsafeguard their health and well-be<strong>in</strong>g.*WHY THIS RESEARCH STUDY?The purpose of the study was to understand the manydimensions of <strong>fistula</strong> and its related social vulnerabilitythrough the experiences and views of girls and women liv<strong>in</strong>gwith <strong>fistula</strong>, members of their families and communities, andlocal health care providers. This study presents vital evidenceon how health care and social systems often fail to meetwomen’s basic needs, and presents recommendations on howthe lives of girls and women can be saved <strong>in</strong> future.from her vag<strong>in</strong>a, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> constant and humiliat<strong>in</strong>g odorand wetness. In nearly all cases of obstetric <strong>fistula</strong>, the babydies. The trauma of labor can result <strong>in</strong> extreme nerve damageto the woman’s lower limbs, lead<strong>in</strong>g to paralysis or seriouslyimped<strong>in</strong>g the ability of the woman to walk normally. Leftuntreated, <strong>fistula</strong> can also lead to pa<strong>in</strong>ful rashes, <strong>in</strong>fections,and ulcerations.Figure 1: Diagram show<strong>in</strong>g how obstetric <strong>fistula</strong> candevelop dur<strong>in</strong>g childbirthWHAT IS OBSTETRIC FISTULA?<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>fistula</strong> is a severe <strong>in</strong>jury that can develop dur<strong>in</strong>gprolonged and obstructed labor. Without prompt medical<strong>in</strong>tervention (typically a caesarean section), the constantpressure of the fetal skull <strong>in</strong> the birth canal cuts off the bloodsupply to the tissues, caus<strong>in</strong>g the tissues to dis<strong>in</strong>tegrate (seeFigure 1). A hole or ‘<strong>fistula</strong>’ then forms between the vag<strong>in</strong>aand bladder and/or between the vag<strong>in</strong>a and rectum. The girlor woman is left with cont<strong>in</strong>uous and uncontrollable leak<strong>in</strong>gBLADDERRECTUM* The companion briefs <strong>in</strong> this series exam<strong>in</strong>e, <strong>in</strong> greater depth, the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs for four focal areas of the current research. A full list of their titles isfound on the f<strong>in</strong>al page of this brief.1

Many women are either unaware that treatment is available tosurgically repair <strong>fistula</strong>, or cannot access or afford thetreatment. As a consequence, many girls and women do notreceive treatment for their condition. They may become sociallyostracized and ridiculed, or become so ashamed of theircondition that they isolate themselves from their communities.Others are rejected and abandoned by husbands and families.Moreover, women may be left with few, if any, opportunitiesto earn a liv<strong>in</strong>g, forced to rely on others to survive [4].STUDY LOCATION, PARTNERSAND PARTICIPANTSThe study was conducted <strong>in</strong> three districts of Tanzania: S<strong>in</strong>gidaRural, Songea Rural and Ukerewe. Additional <strong>in</strong>terviews wereconducted at Bugando Medical Centre <strong>in</strong> Mwanza. Studyparticipants were from several different ethnic groups. Datacollection took place between July 2003 and September 2005and was undertaken by two researchers from Women’s DignityProject and two staff from each of the local partners: HealthAction Promotion Association <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gida, Kivul<strong>in</strong>i Women’sRights Organization <strong>in</strong> Ukerewe and at Bugando MedicalCentre, and Peramiho Mission Hospital <strong>in</strong> Songea. Dataanalysis and write-up were done by staff of Women’s DignityProject and <strong>EngenderHealth</strong>. The study was approved by theNational Institute of Medical Research <strong>in</strong> Tanzania.A total of 61 girls and women with <strong>fistula</strong> participated <strong>in</strong> thestudy. The <strong>in</strong>terviews explored women’s pregnancy, labor,delivery, and post-delivery experiences related to the pregnancythat caused the <strong>fistula</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g their access to resources, socialsupport, antenatal care (ANC), and other health services.Additionally, the women were asked how <strong>fistula</strong> had affectedtheir lives and the lives of their families <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gpsychologically, physically, f<strong>in</strong>ancially, and socially. Participantswere also asked about the cop<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms used to mitigatethe impacts of <strong>fistula</strong>, and recommendations on locallyappropriate solutions to prevent and manage the condition. Allgirls and women liv<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>fistula</strong> who participated <strong>in</strong> thestudy were provided with surgical repair of their <strong>fistula</strong>.In addition, 42 different family members were <strong>in</strong>terviewed tounderstand their perspectives on experiences and care-seek<strong>in</strong>gbehavior related to the pregnancy that caused the <strong>fistula</strong>, theimpact of <strong>fistula</strong> on the lives of family members, and cop<strong>in</strong>gstrategies used. Specifically, <strong>in</strong>terviews focused on the actionsthat the woman and her family and friends took dur<strong>in</strong>g laborand delivery, and the woman’s access to medical, social andf<strong>in</strong>ancial resources over this period. Lastly, researchers helddiscussions with 68 community members and 23 health careproviders to explore their perceptions of the socioeconomic,cultural, and familial factors contribut<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>fistula</strong>, rootcauses and beliefs about <strong>fistula</strong>, and cop<strong>in</strong>g strategies used tomitigate its impact.Study <strong>in</strong>struments <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong>-depth <strong>in</strong>terviews, groupdiscussions, and several participatory research methods.2

F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g 3: The lack of birth preparedness,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g basic <strong>in</strong>formation on childbirth andtak<strong>in</strong>g action around ‘delays’, <strong>in</strong>creases risk.The majority of women <strong>in</strong> the study had planned to deliver ata health facility of some type, although <strong>in</strong> the end nearly allstarted labor at home. A majority of the women <strong>in</strong>terviewedfaced multiple delays <strong>in</strong> reach<strong>in</strong>g a facility with the necessaryservice to enable them to deliver safely. The reason most oftencited for delays was that the woman or her family or friends didnot identify a problem that needed to be addressed by a skilledhealth provider.Fewer than half of the women had set aside some funds forcosts related to labor, delivery, post-delivery and/or transport.Thus, when problems emerged, the necessary preparationwas lack<strong>in</strong>g.Recommendation: Concrete <strong>in</strong>formation on birth preparedness,that is understood and acted upon, is critical to avoid delays <strong>in</strong>time of emergency.Health care providers, women, and their families needcomprehensive <strong>in</strong>formation on birth preparedness to help <strong>in</strong>times of emergencies. It must <strong>in</strong>clude the ‘danger signs’ that<strong>in</strong>dicate obstetric complications, the imperative to take quickaction when signs and symptoms of obstetric complicationsfirst present, and the importance of adequate plann<strong>in</strong>g toavoid delays <strong>in</strong> times of emergency (e.g., sav<strong>in</strong>g funds fordelivery-related expenses and arrang<strong>in</strong>g emergency transportplans). Traditional birth attendants and health workers <strong>in</strong>peripheral facilities (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g lower level cadres) must alsohave this basic knowledge so that quick and proper referralscan be made to facilities with qualified medical personnel,supplies, and equipment to manage complications. Byunderstand<strong>in</strong>g and swiftly act<strong>in</strong>g upon complications aris<strong>in</strong>gdur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy and delivery, the risks of maternal and<strong>in</strong>fant death and <strong>in</strong>jury, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g obstetric <strong>fistula</strong>, can besignificantly reduced.F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g 4: Lack of access to emergencycaesarean section poses a great threat towomen’s lives.The most commonly cited barriers to facility-based deliverywere lack of money, and excessive distance to the nearesthospital. Yet, nearly all the women who did make a movedur<strong>in</strong>g childbirth eventually got adequate care at the hospitallevel. The majority of the women <strong>in</strong>curred costs for transport,and a m<strong>in</strong>ority reported hav<strong>in</strong>g to pay some type of fee forthe delivery.The 2004/5 Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey notesthat women do not have sufficient access to essentialmaternal health services <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g caesarean section. The2004/5 DHS also notes that “gett<strong>in</strong>g money for treatment”was the s<strong>in</strong>gle biggest obstacle fac<strong>in</strong>g women seek<strong>in</strong>g healthcare, followed by distance to the health facility and the needto take transportation. Strik<strong>in</strong>g differences were reportedbetween rich and poor women, and between urban and ruralwomen. Over half of the poorest qu<strong>in</strong>tile cited distance tofacility and the need to take transport as big problems. Incontrast, less than 20% of urban women and those from thehighest qu<strong>in</strong>tile encountered these problems [5].4

channels that reach rural areas need to be prioritized, forexample radio broadcast and <strong>in</strong>formational outreach throughfaith-based <strong>in</strong>stitutions such as churches and mosques.Beyond <strong>in</strong>formation, women must be supported actively toaccess <strong>fistula</strong> treatment. Given the severe economic impact of<strong>fistula</strong> on women and their families, it is imperative that<strong>fistula</strong> repairs be provided at m<strong>in</strong>imal or no cost. Ideally,support should cover the costs of both transport andtreatment. Fistula programs have an ethical obligation todevelop mechanisms of such support, so that advocacy on<strong>fistula</strong> does not raise women’s expectations for treatmentwhen treatment is beyond reach.F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g 6: Even though most women with<strong>fistula</strong> had support from others, theemotional and economic impacts of <strong>fistula</strong>are substantial for the woman herself, andfor her family.Although all of the women <strong>in</strong> the study mentioned be<strong>in</strong>gsupported by at least one person when they susta<strong>in</strong>ed their<strong>fistula</strong>, the majority of the women reported that they isolatedthemselves from their community. The women felt a strongsense of shame about their condition and did not want to soilthemselves <strong>in</strong> public or to smell badly. A majority of thewomen suffered stress and worry, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g about the impactof the <strong>fistula</strong> on their families.Women and their families also suffered economically as aresult of the <strong>fistula</strong>. Nearly all of the women said that <strong>fistula</strong>affected their ability to work. Of these women, the majoritycould not work at all. As a result, their families were affectedby the loss of the woman’s contribution to work <strong>in</strong> the home,on the farm, or <strong>in</strong> earn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>come from other employment. Inaddition, families faced higher expenses <strong>in</strong> the dailymanagement of the woman’s condition, such as costs forextra clothes and soap, and <strong>in</strong> efforts to seek treatment torepair the <strong>fistula</strong>. Many families made great sacrifices to helpgirls and women get <strong>fistula</strong> repairs, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g family membersforgo<strong>in</strong>g work and <strong>in</strong>come to accompany the women to seektreatment.Recommendation: Advocacy, support, and re<strong>in</strong>tegrationefforts should be <strong>in</strong>stituted to reduce the emotional andeconomic impacts of <strong>fistula</strong>.After successful repair, most women <strong>in</strong> the study resumedtheir normal lives, able to <strong>in</strong>teract freely with their families,friends and communities, attend meet<strong>in</strong>gs and churchservices, and take active roles <strong>in</strong> economic activities. Manycalled their return to health “a miracle.” The f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs alsoshow that families - <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g husbands - can, and do, supportwomen with <strong>fistula</strong>. These and other positive illustrations ofsupport from family, friends, and communities can be used <strong>in</strong>public education and advocacy efforts to break the stigmaaround <strong>fistula</strong>.Re<strong>in</strong>tegration programs can strengthen opportunities forsuccessful re-entry after repair. However, to date, only limited<strong>in</strong>formation is available on women’s experiences withre<strong>in</strong>tegration. Further research is needed <strong>in</strong> this area so<strong>in</strong>terventions are based on a thorough understand<strong>in</strong>g of whatwomen with <strong>fistula</strong> themselves need to help them beg<strong>in</strong> lifeanew after repair. Re<strong>in</strong>tegration efforts should also be m<strong>in</strong>dfulof the potentially differ<strong>in</strong>g needs of women who have had<strong>fistula</strong> for different periods of time, as it is possible thatstigma and isolation deepen the longer that a woman liveswith <strong>fistula</strong>.6

Bibliography[1] Murray C and Lopez A. Health Dimensions of Sex and Reproduction. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland:1998[2] Raassen, T. Personal communication 2005, based on <strong>in</strong>ternational estimates and local conditions.[3] Women’s Dignity Project. Faces of Dignity. Dar es Salaam: 2003[4] UNFPA and <strong>EngenderHealth</strong>. <strong>Obstetric</strong> Fistula Needs Assessment Report: F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from N<strong>in</strong>e African Countries. NewYork: 2003.[5] United Republic of Tanzania. National Bureau of Statistics and Macro International. Tanzania Demographic and HealthSurvey 2004/5. Dar es Salaam: 2005[6] Nicol, M. “Hospital Fistula, VVF Patients, Experiences of Health Services”. Presentation at the Conference of East,Central and Southern Africa <strong>Obstetric</strong>ians and Gynecologists, October, 2005. Dar es Salaam: 2005.[7] Kigoda, A., Deputy M<strong>in</strong>ister of Health and Social Welfare, from her speech to Parliament on 3 July 2006. Dodoma,Tanzania.[8] Mbaruku G. and Bergstrom S. Reduc<strong>in</strong>g Maternal Mortality <strong>in</strong> Kigoma, Tanzania. Health Policy and Plann<strong>in</strong>g (1995)10(1): 71-78[9] Kayongo M., et. al., Strengthen<strong>in</strong>g Emergency <strong>Obstetric</strong> Care <strong>in</strong> Ayacucho, Peru. International Journal of Gynecologyand <strong>Obstetric</strong>s (2006) 92: 299-307[10] Santos C., et. al., Improv<strong>in</strong>g Emergency <strong>Obstetric</strong> Care <strong>in</strong> Mozambique: The Story of Sofala. International Journal ofGynecology and <strong>Obstetric</strong>s (2006) 94: 190-201Other briefs <strong>in</strong> the seriesOverview Risk and Resilience: <strong>Obstetric</strong> Fistula <strong>in</strong> TanzaniaAn Overview of F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs and Recommendations from the StudyBrief 1 Prevent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Obstetric</strong> Fistula: Antenatal Care, Birth Preparedness and Family Plann<strong>in</strong>gBrief 2 Reduc<strong>in</strong>g the Risk of <strong>Obstetric</strong> Fistula: Skilled Birth Attendance and Emergency <strong>Obstetric</strong> CareBrief 3 Liv<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>Obstetric</strong> Fistula: The Devastat<strong>in</strong>g Impacts of the Condition and Ways of Cop<strong>in</strong>gBrief 4 Mend<strong>in</strong>g Lives and Recover<strong>in</strong>g Livelihoods: Repair of <strong>Obstetric</strong> Fistula and Re<strong>in</strong>tegrationFor more <strong>in</strong>formation, please contactWomen’s Dignity ProjectPO Box 79402Dar es Salaam, TanzaniaTel: +255 22 2152577Fax: +255 22 2152986Email: <strong>in</strong>fo@womensdignity.orgWebsite: www.womensdignity.org<strong>EngenderHealth</strong>440 N<strong>in</strong>th AvenueNew York, NY 10001 USATel: +1 212 561 8000Fax: +1 212 561 8067Email: <strong>in</strong>fo@engenderhealth.orgWebsite: www.engenderhealth.orgHealth ActionPromotion AssociationPERAMIHOMISSION HOSPITALPhotos by Mwanzo Mill<strong>in</strong>ga© Women’s Dignity Project and <strong>EngenderHealth</strong> 2006. All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced without fee or prior permission foreducational and <strong>in</strong>formational purposes, provid<strong>in</strong>g acknowledgement of the source is recognized by citation.8