NGAANYATJARRA ART OF THE LANDS - UWA Publishing - The ...

NGAANYATJARRA ART OF THE LANDS - UWA Publishing - The ...

NGAANYATJARRA ART OF THE LANDS - UWA Publishing - The ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

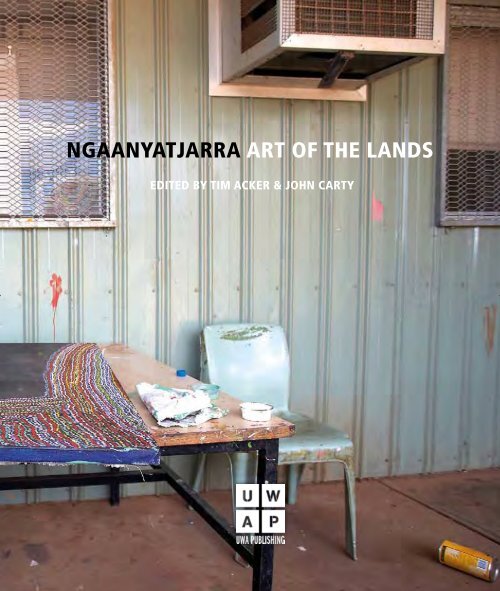

Ngaanyatjarra art of the landsedited by tim acker & john carty

First published in 2012by <strong>UWA</strong> <strong>Publishing</strong>Crawley, Western Australia 6009www.uwap.uwa.edu.au<strong>UWA</strong>P is an imprint of <strong>UWA</strong> <strong>Publishing</strong>,a division of <strong>The</strong> University of Western AustraliaThis book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposeprivate study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under theCopyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process withoutwritten permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisherCopyright © Tim Acker and John Carty 2012<strong>The</strong> moral right of the authors has been assertedCartography courtesy of Department of Indigenous Affairs(Tony Veale, Senior Cartographer)Design and typeset by Anna Maley-FadgyasPrinted by ImagoCover image by Cliff Reid, Tingarri, 2010, 1220 x 1110 mm:acrylic on linen, Sims Dickson CollectionA full CIP record for this book is available from theNational Library of Australia

opposite Artists in the studio, Tjarlirli Artsfollowing Tjitji pirni! Angilyiya Mitchell, Anawari Mitchell and <strong>The</strong>lma McLean piggy-back their tjanpi kidsContentsNgaanyatjarra LandsArt CentresvviForewordMap1 An emerging present: a shorthistory of the Ngaanyatjarra Lands.David Brooks15 Purnu, tjanpi, canvas:a Ngaanyatjarra art history.John Carty37 <strong>The</strong> art of community: the place ofart centres in the NgaanyatjarraLands. Tim Acker49 Plates127 Maruku Arts and Crafts.John Carty141 Memories of a purnu-man in theNg Lands. Steve Fox149 Winneringu! Tjanpi DesertWeavers. Jo Foster161 Kanytupayi’s attraction.Thisbe Purich263 Glossary265 Art centres267 Artists281 Acknowledgements171 Papulankutja Artists.John Carty181 Cliff Reid. Dianna Isgar183 Mr Forbes. David Brooks191 Warakurna Artists. John Cartywith Edwina Circuitt207 Mr Shepherd’s studio.Edwina Circuitt209 <strong>The</strong> past is everywhere:Ngaanyatjarra history paintings.Pamela Faye McGrath217 Kayili Artists. John Carty231 Singing brindle. Anisha Angelroth233 Reflections on Kayili Artists.Tim Pearn229 Warburton glass.Nancy Tjungupi Carnegie231 Tjarlirli Art. John Carty241 Nyarapayi Giles. Pamela McGrath253 Irrunytju Arts. Judith Ryan259 Irrunytju Arts story.Tjawina Robertsix

Ngaanyatjarra Lands

<strong>The</strong> next generation of artists – a young painter in the making, at Papulankutja Artists, 2011An emerging present: a shorthistory of the Ngaanyatjarra LandsDavid Brooks1 This figure has beencalculated fromarchaeological work thathas been undertakenat various places in theWestern Desert and onits margins. See, forexample, Smith, MA.(2006) Characterisinglate Pleistocene andHolocene stone artefactassemblages fromPuritjarra rock shelter:A long sequencefrom the Australiandesert, Records of theAustralian Museum 58:371-410.It is safe to say that the majority of Australians have neverheard of the Ngaanyatjarra Lands, though they occupy anarea the size of the state of Victoria, or for that matter, thesize of the whole United Kingdom. Anyone who finds theLands on a map will see that they are located in the middleof the continent’s deserts, 1,000 kilometres from the twonearest towns; Alice Springs to the east and Kalgoorlie tothe west. <strong>The</strong> connecting roads are unsealed and vulnerableto either corrugation or flooding. <strong>The</strong>re are few visitors to thearea apart from the ‘adventure’ tourists who take their wellequippedfour-wheel drives along the Great Central Roadbetween Perth and the famous sites of the centre like Uluru.But even these travellers, more intrepid than most, are unlikelyever to see beyond what is visible from the highway. <strong>The</strong> longstretches of desert landscapes, striking in their immensity, area confronting prospect when imagining human habitation.This is far from the perspective of the 2,000 Aboriginalpeople, the Ngaanyatjarra, who live in ten tiny communities,located away from the highway, scattered in the dunes andranges of the Ngaanyatjarra Lands. For these people, this landhas been home for around 35,000 years. 1Underpinned by this awe-inspiring history andcontinuity, these communities are in no sense a relic of thepast. This is no sleepy hollow that the world has passed by.Ngaanyatjarra life is about today, and it is busy. <strong>The</strong>re issubstance and complexity to its internal affairs, enough tosatisfy the most enquiring and energetic of personalities. Noone dreams of a more interesting life elsewhere. <strong>The</strong> peopleare poor by national standards, but they have their owntype of prosperity. Ngaanyatjarra well-being arises from,is sustained by, and feeds back into one great wellspring– connectedness to Country. <strong>The</strong> Ngaanyatjarra, unlike somany people in Australia, including many Aboriginal people,live on their own land. This land was never taken away fromthem and they have never been separated from it. To them,it is the rest of Australia – the governments who make thepolicies and the tourists who pass by so fleetingly – thatseems adrift from its moorings and ‘remote’ in its location.<strong>The</strong> communities of the Lands are occupied by peoplewith ties to their immediate area and are run relativelyindependently, yet all are knitted together by a web of kinship,Dreamings, history, and now, new forms and styles of artisticactivity. To understand the development of contemporaryart in these communities, it helps to first understand howthese communities even came to be. It is a story that involvesall the people and all corners of their Lands, but the focusin this essay, as in the book more broadly, is on the fourcommunities – Warakurna, Papulankutja, Tjukurla and Patjarr– whose art centres are part of the Western Desert Mob.<strong>The</strong> Ngaanyatjarra area first became known to thebroad public in sensational fashion in the late 1950s, viaan episode that came to be called ‘the Warburton Range1

Judith Yinyaka Chambers, Mr Grayden, 1016 x 1016 mm: acrylic on canvas, National Museum of Australia‘Mr Grayden travelled a long way round, through tali country, from waterhole to waterhole. Starting at Warburton, he went down Walu way and up to Tjurtjuranyarra (CircusWater)...<strong>The</strong>y were looking for the smoke from the camp fire, then they would go to the camp and meet those people. <strong>The</strong>y would collect the papa (dingo) skins and give thepeople food and clothes. My father and mother met Mr Grayden near Yuliya.’

left People waiting to sell dingo skins to Mr Wade of the Warburton Missionright Delivery of weekly stores from the Warburton Mission, 19642 Unfortunately, in beingcast as political pawnsand victims, many ofthe facts were distortedin this case and theagency of Ngaanyatjarrapeople at the time wasmisrepresented. See P.McGrath and D. Brooks,‘<strong>The</strong>ir Darkest Hour: thefilms and photographsof William Graydenand the history of the“Warburton RangeControversy” of 1957’,in Aboriginal History vol.34, ANU Press, Canberra.3 <strong>The</strong> larger backgroundto these developmentsis described succinctlyby Sue Davenport, PeterJohnson and Yuwaliherself in Cleared Out(Aboriginal StudiesPress, Canberra, 2005);an account whichreveals the interplaybetween the Stateand CommonwealthGovernments and thefailure of both – butparticularly the StateGovernment, whoseresponsibility it primarilywas – to act effectively inthese matters in regardto Aboriginal interests.4 This was the bodycreated by theCommonwealthGovernment toimplement thetesting program.Controversy’. Newspaper photographs were published thathad been taken by Bill Grayden at a dry waterhole north ofWarburton, showing a group of Aboriginal people lookingemaciated and poverty stricken. In truth, this was a singlegroup that had just come in from the Rawlinson Range –which was in the middle of a drought – and the pictureswere far from reflective of the general state of people inand around the Lands. But the story struck a public nerve,exposing the deep issues and divisions in Australian societyover the welfare of Aboriginal people. Through these events,the Ngaanyatjarra people unwittingly became symbols, inthe 1950s, of Australia’s neglect of its Indigenous people. 2<strong>The</strong>re was little specification of local places and identitiesin the published material that surrounded the controversy,with the exception of the Warburton Mission. <strong>The</strong> Missionwas established in 1934, and represented the first permanentEuropean incursion into the Lands. <strong>The</strong> Mission becamehome for those desert people whose traditional Country wasclose by, with others who were based further afield, comingto orient their seasonal movements by bringing in dingoscalps that the missionaries sold for the government bounty.In providing Ngaanyatjarra people with secure resourcesand a base in, or close to, their home territories, the Missionplayed a crucial role in stemming the combination of forcesthat would otherwise have seen much greater populationloss in subsequent decades (until the homelands movementin the 1970s), and in mitigating other changes that wouldhave inevitably diminished that bondedness of people withCountry. <strong>The</strong> Mission gradually built up its numbers ofNgaanyatjarra residents and today, as a self-run community,Warburton is the major population centre of the Lands.In its first two decades, the mission had limited contactwith people from areas such as Warakurna and Papulankutja.However, the 1950s was the time when real change came tothe region, and the people from these regions were amongthe first affected. <strong>The</strong> biggest driver of change that the regionhas ever seen emerged in this period: the rocket-testing centreat Woomera, in central South Australia. <strong>The</strong> NgaanyatjarraLands lay under a possible flight path for rockets that mightultimately come to ground somewhere near the Percival Lakes,further to the north-west, near the Canning Stock Route. <strong>The</strong>Lands were never thought of as any kind of focal point in thisprogram, which represented Australia’s major contributionto the Cold War. 3 All the Weapons Research Establishment(WRE) 4 wanted of this area was that it be the site of a testingpoint for the atmospheric conditions ‘down range’ from thelaunching point at Woomera. WRE also needed to ensurethat no nomadic people in the region became victims of anyrocket debris that might happen to fall from the sky. Fromthese concerns two types of impact arose. One began in 1955with the grading by Len Beadell’s subsequently famous roadbuildingteam of a major road, the ‘Gunbarrel Highway’ fromngaanyatjarra lands 3

Jean Burke, Macauley and McDougall, 762 x 1524 mm: acrylic on canvas, National Museum of Australia‘At holiday time we were walking back towards Blackstone. Mr McDougall and Mr Macauley would light a fire in the spinifex to let us know that they were nearby, next we wouldsend up a fire to show them where we were camped. Like sending a message on the telephone, we were talking from a long way. <strong>The</strong>n they would come to the camp in the yellowtruck with the mirka (food). We were all happy to see him, children and dogs were running around happy.’

left Ivan Shepherd, who would become an important Ngaanyatjarra artist as an adult, was photographed as a young man at Giles Weather Station, circa 1956-58. Photograph byRobert Macaulay, Robert Macaulay Private Collection, Canberraright Kanytjupayi Benson, who would become one of the great Ngaanyatjarra artists, with her husband, Jimmy Benson, and their children Sylvia (baby) and Thomas. c. 1956–1957,Rawlinson Range. Photograph by Robert Macaulay, Robert Macaulay Private Collection, Canberra5 Ernabella wasestablished at the sametime as Warburton andbecause of this may beconsidered as in manyrespect as a ‘sister’establishment, althoughit was associated with adifferent denomination.6 For some of the facts citedhere about Macaulay, aswell as about the ‘GraydenAffair’ referred to earlier,I am indebted to the workof Pamela Faye McGrath,also a contributor to thisvolume.Central Australia to the vicinity of the waterhole at Warakurnain the Rawlinson Range. <strong>The</strong> purpose of the road was tofacilitate the building at this site of a weather station, to benamed after the explorer Ernest Giles. <strong>The</strong> other impact wasthe deployment by WRE of two Native Patrol Officers (NPOs).<strong>The</strong> intention of the government was that the NPOswould mitigate impact, not cause it – but inevitably, in apart of the world where so few whitefellas had ever been, letalone stayed for any length of time, they turned out to playa significant role in their own right. For many of the peoplewho were still leading a customary or ‘nomadic’ way of life inthis part of the desert – and this was nearly everybody exceptthose who had settled at Warburton Mission or at Ernabella 5in the Pitjantjatjara Lands in north-western South Australia –NPO Walter MacDougall was the first white man with whomthey had meaningful contact. Fortunately he was a man whocarried out his work with great integrity and his memory isheld in universally high regard as a result. <strong>The</strong> younger NPO,Robert Macaulay – also a man of integrity – was appointedlater, in 1956, to assist MacDougall, and with a particularbrief of working in and around the new Giles WeatherStation. While MacDougall’s work found him ranging over ahuge area, Macaulay stayed mostly in the one place, Giles,for two full years, getting to know the Warakurna people,including members of the Shepherd, Porter, Reid, Golding,Bennett, Newberry, Burke and Ward families. 6<strong>The</strong> building of the weather station, tiny though it was inphysical terms and of only peripheral importance in the grandscale of the rocket program, was a significant event in theLands, and it had a major effect on the lives of the scoresof Aboriginal people who were living on their Country wherethe weather station was sited. <strong>The</strong> creation of the station didnot directly undermine people’s way of life; the area directlyaffected was small and people had plenty of alternativewaterholes to use. <strong>The</strong> impact was more about the new andoften bizarre dynamics that were introduced. Station staffsometimes encouraged the presence of the desert peoplethere, and sometimes tried to force them away. This reflectedthe official policy on how to deal with these matters, whichwas itself confused. On the one hand, the government wantedto avoid accusations of ‘corrupting’ the Aboriginal way of life,which was assumed to have been previously ‘untouched’,while on the other, it was sensitive to possible accusations ofinhumanely withholding assistance from people in need.As to the local families in that area, the prevailingdrought meant that they wanted any food they could getfrom the station, sometimes desperately. Beyond this, theywere certainly interested in establishing relations. ‘Wewanted to get learned for the whitefella’, people have said.It was always the way of the desert to do this. Provided anewcomer was not an out-and-out antagonist, survival inthis harsh environment would be even more difficult if yourngaanyatjarra lands 5

habit is to reject others. Hence, when the staff did things likefiring shots over their heads to scare them away, the peoplewere not only frightened but greatly disappointed.<strong>The</strong> building of the road to the weather station inWarakurna by Len Beadell closely followed an interventioninto the Lands from another source. <strong>The</strong> Western AustralianGovernment had always been conspicuous by its absencein the Lands. For over two decades it refused to give anyassistance to Warburton Mission while doing its best to ignorethe existence of the desert people altogether. But in 1955 itresponded to the pressure from a mining company by makingavailable for exploration, without consulting Yarnangu, a largeportion of the Reserve 7 in the central ranges, well to the east ofWarburton and to the south of Warakurna. <strong>The</strong> result was busymining camps at both Blackstone and Wingellina. At thesecamps there was little or no restraint on engagement with thelocal people, and not surprisingly, the results were mixed. Onthe one hand, people worked there and received payment inkind if not in money, but on the other hand, there was concernover some miners’ intentions towards local women, as well asconflict over damage to sacred Dreaming places. For many ofthe Blackstone mob this was their first significant contact withwhite men, and it was different from the experience of boththe Warburton and the Warakurna people.A network of new tracks appeared in this part ofthe Lands as a result of the exploration activity, and wasaugmented by the Gunbarrel Highway when it was builtthrough the same area. NPO MacDougall wrote as earlyas 1955 that it was ‘now possible to drive along roads fromAlice Springs to Kalgoorlie’. This had been an unheard-of ideanot long before. Macaulay reported that ‘during the secondhalf of the 1950s an unprecedented number of governmentofficials associated with surveying and mineral exploration– not associated with Aboriginal affairs – and even tourists,have been traversing the Lands’. 8 <strong>The</strong> negative effects didnot pass without a response from the Blackstone mob.Rising dissatisfaction led to the mobilisation of the people tohave the offenders removed. Eventually, the mining campsclosed down, and the tourist trips were stopped.Coincidentally, the creation of the new roads had other,internal consequences, in terms of the routes and patterns ofAboriginal relations and communications. Before this time, thegreat stretches of sand-dune country between the Rawlinsonand Central Ranges had constituted a considerable barrier toregular travel – necessarily on foot – between these two areas,but now, with the building of Beadell’s road, communicationand social exchange between Warakurna and Blackstone werefacilitated. A particularly close relationship between these twocommunities continues to this day.All the new interest and activity on the Lands in thisperiod did not mean that life changed drastically or suddenlyfor most of the people, particularly for those still livingcustomary lives on the greater, undisturbed portion of thecountry. Indeed, it was not for another ten years that theTjukurla and Patjarr mobs became visible in this narrative, foras occupants of the most remote parts of the hinterland thevarious developments passed them by. In the case of Patjarr,there was to be drama of a kind arising from their earlyencounters with the wider world, just as there had been, indifferent ways, with the Warakurna and Blackstone Mobs.By the time they had their first lengthy dealings with awhitefella in the form of the archaeologist Richard Gould,who went to camp with them in their home Country at Patjarrin the Clutterbuck Hills in the mid 1960s, 9 the Patjarr mobhad made a number of tentative visits to Warburton Mission.At first the Warburton people, who by this time had been atthe Mission for more than 30 years, were quite antagonistictowards them. 10 Having made adjustments, some of thempainful, to the Mission’s expectations and way of life, it musthave been uncomfortable, or worse, for these people, nowthoroughly used to a settled life, to be confronted with whatamounted to a vision of their own past. On the other hand,now that there is a universally more positive valuation ofthe ‘traditional past’, the Patjarr mob has come to representa proud image of cultural continuity, but also perhaps aconflicted vision of how history unfolded across the lives ofsome Ngaanyatjarra people in the twentieth century.It is not clear whether in the late 1960s the Patjarr peopleactually wanted or intended to settle in Warburton, but inthe event they were given no choice. On top of the visitsby the relatively benign Gould and filmmaker Ian Dunlop,they began to be beset in their homeland area by a legionof state government field parties. It was their misfortune tocollide with the fall-out of the long decades of state neglect.Now, in the 1960s, against the backdrop of the unwantedcontroversies associated with Giles Weather Station and withthe rocket program generally, officialdom wanted to showhow concerned it was about the desert people, in part bypatrolling the desert looking for remaining nomadic groups.<strong>The</strong> government soon perceived the political impossibility ofbeing seen to ‘leave them out there’ in the desert — and theymade sure they were ‘brought in’. With the social difficultiesthat they experienced once they were at Warburton, thesepeople headed off for a time in search of some of their relativeswho had gone far west to Wiluna. Around 1990, hearingthat the Warburton community was prepared to establish aserviced community at Patjarr, largely at its own expense, theyreturned. <strong>The</strong>y have lived there on their own terms ever since.

left Jean Burke,<strong>The</strong> Wati who was Looking for Lasseter 2011, 762 x 1524 mm: acrylic on canvas, National Museum of Australia. ‘<strong>The</strong>re was a white man. He was travelling aroundlooking for Lasseter. He went and camped at a rock hole south of Docker River. He then went to another rock hole where he drank the water and washed his face. Some people sawhim. <strong>The</strong>y must have got jealous and got wild. <strong>The</strong>y speared him and he finished.’right Patjarr community today7 Reserves for the ‘Useand Benefit of AboriginalPeople’ had been createdin the 1920s and ‘30sover a vast cross-borderregion. <strong>The</strong> term‘Ngaanyatjarra Lands’is of much more recentprovenance: it reflectsthe perspective of theself-determination era,and is essentially aninformal term that doesnot correspond withany firm administrativeboundaries.8 Report by RobertMacaulay, 28 March 1960.9 Soon after Gould’sfieldwork with them, theywere filmed by Ian Dunlopof the CommonwealthFilm Unit (now FilmAustralia) for hisrenowned People of theWestern Desert series.10 D. Brooks, ‘What Impactthe Mission?’ Mission Timein Warburton, TjulyuruArts Centre, 2000.<strong>The</strong> main families involved have been the Ward, Carnegie,Campbell, Jennings, Jones, Robertson and Giles families.We lived unaware of the white man and his world…<strong>The</strong>re were no roads. We lived there and saw whensomeone made a road and we were afraid because we’dnever seen anything like it. When we first saw the roadwe all ran off to the bush in fright and we would peerout from behind the bushes. When we used to see aplane flying over, we would run into thick scrub and hide.…we were taken to Warburton. And at Warburton, Iwent to school and I grew up there, my brother Neil andI. I learnt English at school. I used to go to church. I drewpictures and listened. At first, having just come from thebush, we couldn’t understand anything. <strong>The</strong>y would say,‘Hey, you two children, come here.’ We would get scaredbecause we didn’t know. So we would run to mum anddad in fright and say, ‘Mummy and Daddy, they weretalking about you.’ But we just made it up because wedidn’t know. I thought they were going to grab us andchoke us. But they only wanted us to go to school. Westayed there going to school.We were there long before all these trees around theWarburton community were planted. We lived there fora long time with our families. We were there for a whileand we heard talk that someone was going to build aroad back to our home. Lots of people agreed with theidea and all the old people got very happy and said, ‘Yes,make a road and go back to your own Country.’And they did it. I was part of the group of peoplewho made the road. I had only one child, Stephen, at thattime. My father and the rest of the people, many of whomhave passed way, made the road all that way to Patjarr.And my father said, ‘Yes, let’s go back and live there.’We continued working on the road and then thearmy gave us army tents. We stayed there at Karilywaraa long time and the food supply got low. I still had alittle bit for the children. We would go home and putthe food away. We kept living here. A bore for water wasdrilled. We kept living there and later on small houseswere built and a little shop. Later still, a bigger shop wasbuilt. <strong>The</strong> small township of Patjarr kept getting biggerand we would say, ‘This is wonderful. We’re back here inour own Country, our traditional Country.’ Others usedto say, ‘Let’s go back (to Warburton)’ and I’d say, ‘No. Wemade this road out here.’ Norma Ngumarnu Giles<strong>The</strong> Tjukurla mob has never been caught up in one of thesedramas that have their roots in the conflicts, complexitiesand paradoxes of a colonial encounter. <strong>The</strong>se people havealways been just too far out of the way. <strong>The</strong> Tjukurla mobnever attracted government attention as the Patjarr peoplengaanyatjarra lands 7

Eunice Yunurupa Porter, Going Home, 762 x 1016 mm: acrylic on canvas, National Museum of Australia‘All the people went to Warburton for a big meeting. At the meeting we were told that the government were going to help us to start the communities in Mantamaru, Blackstone,Tjirrkarli and Warakurna. We were so happy! People were jumping up saying ‘I want go home to Mantamaru!’, ‘I want to go to Warakurna!’, ‘Ngurraku!’...Everybody rolled up theirswags, blankets, billycans. <strong>The</strong> children and old people went in the trucks and some other people were walking. We were all so happy to be going to our home.’

left Eunice Yunurupa Porter and tjanpi minyma outside Warakurna Women’s Centrecentre A stand of desert oaks in Ngaanyatjarra Countryright ‘Yungal. <strong>The</strong> old people came here for water. It is a sacred rock hole’, says Winston Mitchell, a senior Ngaanyatjarra man at this site north of Papulankutjadid, nor did they experience any clash with Countrymen whohad long ago become accustomed to a changing world.As with Patjarr, the community itself was late in emerging.Tjukurla was not established until around 1989, followingthe tireless urging of the Giles, Butler, Farmer, Ward and Reidfamilies, among others, who had been obliged to wait manyyears at Docker River (just over the border in the NorthernTerritory, and established in 1968) and Warakurna. <strong>The</strong>y stillhave very close links with these communities.Many of the Tjukurla people are actually descendedfrom people whose Country was in and around Kulkurta, thefamed home of the Tingarri Dreaming that has inspired awealth of Western Desert painting. Kulkurta, to this day, isalmost unreachable, buried in a vast swathe of sand-dunecountry north of the Rawlinson Range. <strong>The</strong> Tjukurla area,150 kilometres to the east of Kulkurta and in much moreopen country, had first suffered a loss of population as partof the slow eastward drift that began with developments faraway in Central Australia, including the establishment of theHermannsburg Mission on the Finke River (NT) in the 1890s.As this happened, some of the men from Kulkurta movedin and married the remaining local women. Thus, today’sTjukurla mob looks after not only the country surroundingthe community, but a vast landscape to its west, includingthe Tingarri Country of Kulkurta.This short history gives a glimpse into the kinds of impactsthat Ngaanyatjarra people experienced in their encounter –as recent as it was – with the Australian settler world. As theaccount shows, there was not one amorphous group that wasuniformly affected. <strong>The</strong> harsh conditions of the desert ensuredthat its human population was always sparse and dispersedacross this huge land, with one small group sometimes beingout of contact with another for years on end. Hence, whenchange came from the outside it would affect one quarterin particular and more-distant areas less so. Thus, for manyyears after the missionaries came, it was only the locals of theWarburton Range area who were seriously affected, and theywere altered by the experience in ways that did not extendto their fellows in the Rawlinson or Blackstone Ranges or theClutterbuck Hills. <strong>The</strong> same applies to the locals of the latterareas who experienced the impacts of the Weather Stationand the NPOs, miners, archaeologists and film-makers, andthe government patrols, respectively. Eventually, however, allthe groups were drawn into the more expanded domain thatexists today and that encompasses the Lands as a whole. <strong>The</strong>overall experience is that whatever the local manifestationwas, and however large it may have loomed at the time tothose involved, none of the individual mobs nor the regionas a whole suffered anything that could be classed asdevastating. Certainly, the Ngaanyatjarra people have beenbuffeted by change, but they have not been destroyed by it.In each instance, and as a whole, they have responded tongaanyatjarra lands 9

opposite Jackie Kurltjunyintja Giles , Tingarri Stories, 2000, 1310 x 1910 mm: acrylic on canvas, Courtesy of the Warburton Collectionfollowing <strong>The</strong> Great Central Road, between Warakurna and Warburton, slices through the landscapewhat has come their way. <strong>The</strong>y are not victims, and they donot want to be seen that way.In large part, what has always given these people theirstrength, and what continues to do so, is their Tjukurrpa, orDreaming. To understand the Ngaanyatjarra, how they havesurvived and why they are as vibrant and creative as ever, oneneeds to gain an insight into the ingenuity of their culturalsystem, contextualised as it is by the overarching presence, inthe cultural imagination, of the Dreaming Beings undertakingtheir vast foundational journeys across the desert. Within thisframework, the Tjukurrpa integrates each aspect or dimensionof desert life, providing a conceptual core from which all thechallenges, issues, questions, needs and dilemmas posed bylife could be rendered comprehensible and in some mannerresolved. <strong>The</strong>se Dreaming Beings established the features ofthe landscape as well as the human social and moral order,endowed the world with its animal and plant food and otherresources, and provided the ritual knowledge by means ofwhich successive generations of people could continue toreproduce themselves socially and spiritually.<strong>The</strong> great Dreaming travellers are colourful characterswhose adventures unfold in a mythological world that canbe visceral and bloodthirsty, but is also often humorous andironical. <strong>The</strong> Wati Kutjarra (Two Goanna Men), sometimepurveyors of wisdom and knowledge, cavort unconscionablythrough other people’s Country as if it is their own, meetingchallenges boldly but sometimes foolishly, and almostalways with an excess of enthusiasm. Another man, Yula,prowls the landscape on his own rather than in a pair likethe Wati Kutjarra. This aloneness itself prefigures a sinisteror at least problematical nature. Sure enough, Yula, who isold enough to know better, is regularly to be found in pursuitof the Seven Sisters, a group of women who are also greattravellers, but are intent on minding their own business,and certainly on avoiding the attentions of lustful old men.Ngirntaka, namesake of the spectacular perentie lizard thatgrows up to two metres long in the desert, is another manwith an enigmatic personality. <strong>The</strong> sites that bear his nameand imprint are often prominent hills or bluffs that overlooka vast horizon — capturing the way that the reptile itselfwill often be seen on a high rock, peering out. In the stories,Ngirntaka is something of a show pony, but he has a darkerside as a maparntjarra, a magic man. <strong>The</strong>se Dreaming Beingsand many others are celebrated in the paintings created byNgaanyatjarra artists, and the adventures, characteristicsand nuances associated with them are reflected in the feel ofthe paintings and in their iconography. One of the favouritesof some painters is the Tingarri, whose home is the greatnorthern site of Kulkurta. In this Dreaming, waves of Tingarripeople sweep through the sand-ridge landscape of the northlike an invading army, over-running and then incorporatingthe isolated small groups of locals they meet on the way.Sometimes the long (50-kilometre plus), straight sand ridgesthemselves are identified with the streaming hordes. Tingarripaintings typically depict, through multiple circles all joinedby lines, the great connectedness of previously disparateentities that comes about in and through this Dreaming.<strong>The</strong> Dreaming culture of the Ngaanyatjarra people isnot fundamentally different from that of other Aboriginalpeople, though it has a vastness of scope that has sprungfrom millennia of life in the desert landscape. <strong>The</strong> pricelessasset that the people have is a culture and social system thatremains alive and intact. <strong>The</strong> country has not fallen into thehands of others, and it has not been transformed throughdevelopment or tamed in other ways. Apart from the roadsthat run like veins through the Lands, the landscape inwhich the Dreaming beings live on, as they always have,is unchanged. <strong>The</strong> people are still on their Country andare keeping the Dreaming alive and vital. <strong>The</strong>y are doingso not only by continuing to follow their age-old culturalimperatives, but by bringing the Dreaming to bear on thenew circumstances and challenges of their contemporaryworld. <strong>The</strong>re is no more powerful instance of this than thesort of painting that is to be found in their art centres.ngaanyatjarra lands 11