Open as a single document - Arnoldia - Harvard University

Open as a single document - Arnoldia - Harvard University

Open as a single document - Arnoldia - Harvard University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

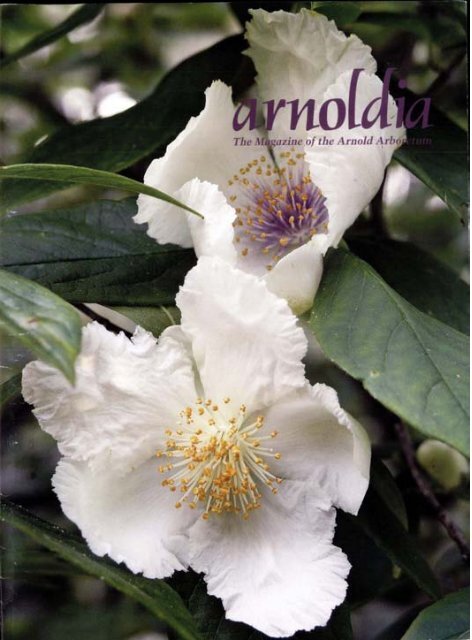

·a-ryt o ~aVolume 63 Number 4 ’ 2005·<strong>Arnoldia</strong> (ISSN 004-2633; USPS 866-100) ispublished quarterly by the Arnold Arboretum of<strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>University</strong>. Periodicals postage paid atBoston, M<strong>as</strong>sachusetts.Subscriptions are $20.00 per calendar year domestic,$25.00 foreign, payable m advance. Single copies ofmost issues are $5.00 (plus postage); the exceptionsare 58/4-59/1 (Met<strong>as</strong>equoia After Fifty YearsJ and54/4 (A Source-book of Cultivar Names), which are$10.00. Remittances may be made m U.S. dollars,by check drawn on a U.S. bank; by internationalmoney order; or by Visa or M<strong>as</strong>tercard. Send orders,remittances, change-of-address notices, and all othersubscription-related commumcations to <strong>Arnoldia</strong>,Arnold Arboretum, 125 Arborway, Jamaica Plam,M<strong>as</strong>sachusetts 02130-3500. Telephone 617.524.1718;facsimile 617.524.1418; e-mail arnoldia@arnarb.harvard.edu.Postm<strong>as</strong>ter: Send address changes to<strong>Arnoldia</strong>The Arnold Arboretum125 ArborwayJamaica Plam, MA 02130-3500Karen Madsen, EditorMary Jane Kaplan, CopyeditorLois Brown, Editorial AssistantAndy Winther, DesignerEditorial CommitteePhyllis AndersenRobert E. CookPeter Del TrediciJianhua LiRichard SchulhofStephen A. SpongbergKim E. TrippCopyright © 2005. The President and Fellows of<strong>Harvard</strong> CollegePage2 Against All Odds: Growing Frankliniain BostonPeter Del Tredici8 A Silver Anniversary: The Fall PlantDistribution and Sale, 1980-20059 The Dove Tree: A Long Journey WestRichard SchulhofIlex pedunculosa: The Longstalk HollyPhyllis Andersen11 I13 ’Yoshino’: An Outstanding Cultivar of theJapanese CedarKim E. Tripp15 Microbiota decussata: A Versatile ConiferNancy Rose17 Chionanthus retusus: The ChineseFringetreePeter Del Tredici ~ Jianhua Li19 Beach Plum: A Shrub for Low-MaintenanceLandscapesRichard H. Uva ~ Thom<strong>as</strong> H. Whitlow2 1 Calycanthus chinensis: The ChineseSweetshrubJianhua Li & Peter Del Tredici23 Rhus trilobata: Worthy Plant SeeksWorthy NameNancy Rose26 Demystifymg DaphnesBob Hyland29 Index to Volume 63Front cover: The flowers of Stewarna ovata formagrandiflora, accession number 18244-B, received fromin 1925.T. G. Harbison of Highlands, North Carolma,This specimen is unusual in producmg five-petaledflowers with either purple or nearly white anther filaments,and occ<strong>as</strong>ionally chimeric flowers with both.Photograph by Peter Del TrediciInside covers: A photo gallery of plants to be offered onSeptember 18, at the Arboretum’s 25th fall plant sale.See list of photographers on page 32.Back cover: The graceful fruit of the longstalk holly,Ilex pedunculosa. Photograph by Ethan W. Johnson.

Against All Odds: Growing Franklinia in BostonPeter Del Trediciheexcuse toricallyyear 2005 gives the Arboretum anto celebrate two of its most his-significant plants: it marks thecentennial of the Franklinia alatamaha locatedalong Chinese Path, on the southwest slope ofBussey Hill. Two specimens, growing side byside, were propagated in 1905 <strong>as</strong> cuttings froma tree received by the Arboretum in 1884. Sincethen, the plants have become giant shrubs thatsprawl across the landscape, taking root wherevertheir branches touched the ground. This "selflayering"habit of Franklinia is an importantpart of its growth strategy and gives the plantsan air of dynamism that suggests they will havemoved to a completely different part of the Arboretumby the time of their next centennial.The larger of the two plants (#2428-3-B) isnow 21 feet (6.3m) tall by 53 feet ( 16m) wide andh<strong>as</strong> eight more-or-less vertical "trunks" greaterthan 5 inches (12cm) in diameter (the largest is 7inches, or 18cm). The smaller plant (#2428-3-A)is also 21 feet tall but just 30 feet (9m) wide, andh<strong>as</strong> six stems larger than 5 inches in diameter.In the ranks of monumental trees, these are notFranklima alatamaha, # 2428-3-B, at the Arnold Arboretum.

3The spectacular flower of Franklinia.impressive dimensions, but they are enough toplace them among the largest Franklini<strong>as</strong> anywherein the world. More important, they are theoldest Franklini<strong>as</strong> of known, <strong>document</strong>ed lineage.To put it another way, we know where theplants came from and when, which is more thanmost people can say about their Franklini<strong>as</strong>.The title of "oldest <strong>document</strong>ed Franklinia"w<strong>as</strong> bestowed on the Arboretum’s plants in 2000after a two-year survey of cultivated Franklini<strong>as</strong>throughout the world that w<strong>as</strong> conducted byHistoric Bartram’s Garden in Philadelphia.’ Toappreciate the significance of this finding, wemust review the plant’s colorful history. Thespecies w<strong>as</strong> discovered in southe<strong>as</strong>t Georgia,along the Altamaha River near Fort Barrington,on October 1, 1765, by John Bartram and hisson William. The plant w<strong>as</strong> not in flower atthe time, so its identity remained uncertain.William returned to the area in 1773 and produceda beautiful illustration of the plant inflower that he ranked <strong>as</strong> being "of the first orderfor beauty and fragrance." In 1776, William w<strong>as</strong>able to collect seed from the plants, which hetook back to Philadelphia. Several other collectorslater visited the Bartram’s Franklima sitealong the Altamaha River, the l<strong>as</strong>t being theEnglish nurseryman John Lyon in 1803.2 Sincethen, no one h<strong>as</strong> reported finding Frankliniagrowing in the wild.3The species w<strong>as</strong> first described and giventhe name Franklinia alatamaha in 1785 byWilliam’s cousin Humphry Marshall in hisgroundbreaking book, Arbustum Americanum:The American Grove. William’s own descriptionof his encounter with Franklinia in the wilddid not appear until 1791, when he publishedTravels after a long series of delays. UnfortunatelyBartram’s very American name did nottake hold in Europe, where botanists chose torefer to Franklinia <strong>as</strong> Gordonia pubescens.4 Thisname stuck until 1889, when Sargent changedit to Gordonia altamaha.5 It w<strong>as</strong>n’t until after1925 that Humphry Marshall’s original namefor the plant, Franklinia alatamaha, w<strong>as</strong> widelyrecognized by botanists <strong>as</strong> legitimate.6

4William sowed the Franklinia seedhe had collected shortly after hisreturn to Philadelphia in January 1777,and they germinated soon after. Theresultmg plants produced their firstflowers four years later, in 1781, andtheir first seed in 1782.’ On August 16,1783, William wrote to Linnaeus thathe had raised a total of five Franklini<strong>as</strong>eedlings-two he sent to France andtwo he planted in his own garden,which were currently flowering and"full of seed nearly ripe."8In November 1831, William Wynne,the foreman at Bartram’s Garden,reported that one of the original seedlingsw<strong>as</strong> fifty feet tall,9 and in 1832,the botamst Constantine Rafinesquevisited the garden and described <strong>as</strong>pecimen that w<strong>as</strong> "nearly 40 feethigh."’° In 1846, D. J. Browne noteda Franklinia in Bartram’s garden thatw<strong>as</strong> "fifty-two feet in height, with atrunk three feet and nine inches incircumference [which equals a diameterof 14 inches]."" Seven years later,Thom<strong>as</strong> Meehan me<strong>as</strong>ured one ofBartram’s Franklini<strong>as</strong> at "about thirtyfeet high [with] a diameter of fromThe Arboretum’s original accession card for the Franklinia alatamaha(received <strong>as</strong> Gordonia pubescens) from Thom<strong>as</strong> Meehan m December1884Thom<strong>as</strong> Meehan (1826-1901).This drawmg appears in The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture,rev. ed., 1916, with this caption : "A tender tree bound m branches ofhemlock. The protected tree is a specimen of gordoma [Frankhnia] about10 feet high, at Arnold Arboretum, Boston."

5nine to twelve inches." He went on tonote that "the finest specimen latelyblew off in a gale,"’z a statement thatclearly indicates that only one of Bartram’soriginal seedlings-the smallerof the two-w<strong>as</strong> alive in 1853.The l<strong>as</strong>t me<strong>as</strong>urement of the originaltrees w<strong>as</strong> in 1890, by Joseph Meehan,Thom<strong>as</strong>’ younger brother, whoreported in Garden and Forest:This tree w<strong>as</strong> supposed to be dead, andin fact it did die to the ground, but ona recent visit to it I observed a suckerof several feet m length from a portionof the stump beneath the ground.In this same article, Meehan reportedthe existence of a 25-foot-tall specimenof Franklinia growing in thegarden of William De Hart in Philadelphiathat w<strong>as</strong> "raised by layeringa branch of the original tree in Bartram’sGarden."13 Unfortunately thistree no longer exists.The two plants that grew in Bartram’sgarden were a ready source ofFranklinia seed-indeed, the onlysource-and they were distributedby William and later by his nephew,Robert Carr.’4 As Franklinia becamemore common in the Philadelphiaarea,a number of local nurseriesbegan propagating it. Foremostamong the early propagators w<strong>as</strong>Thom<strong>as</strong> Meehan, who had immigratedto the United States in 1848and worked <strong>as</strong> the gardener at Bartram’sGarden before establishing his own nurseryin Germantown in 1853.’S In that same year,Meehan published The American Handbook ofOrnamental Trees in which he described thecultivation and propagation of Franklinia: "Itseems to thrive best in a light rich loam, contiguousto moisture; and may be propagated byeither seeds or layers."’~ During the 1870s and80s, the Arboretum’s first director, C. S. Sargent,worked closely with Meehan to save Bartram’shouse and what w<strong>as</strong> left of the garden fromdestruction, a goal that w<strong>as</strong> accomplished in1891 when the property officially became partof the Philadelphia park system."C. E. Faxon’s illustration of Franklima alatamaha (Tab XXII) from volumeone of Silva of North America by C. S. Sargent (1890).It w<strong>as</strong> therefore appropriate that Thom<strong>as</strong>Meehan should have donated a Franklinia plantto the Arnold Arboretum. It w<strong>as</strong> accessionedunder #2428 <strong>as</strong> Gordonia pubescens in December1884. Meehan’s donation w<strong>as</strong> most likelypropagated from a specimen of Franklinia growingin his nursery in Germantown, just outsidePhiladelphia. Sargent mentions this tree in theFranklima entry of the first volume of Silva ofNorth America where he published a beautifulillustration of it.l8 The specific technique thatw<strong>as</strong> probably used to propagate this plant w<strong>as</strong>described by Thom<strong>as</strong> Meehan’s younger brother7Joseph in Garden and Forest: "The tree can be

1893.7its hardiness. From the perspective of 120 years’hindsight, however, the plant’s susceptibility todise<strong>as</strong>e-especially from the wilt-causing fungusPhytophthora cinnamoni-appears to be amore critical problem. This pathogen is particularlytroublesome in heavy, wet soils, but evenwhere drainage is not an issue, Franklmia h<strong>as</strong>the well-deserved reputation of being difficultto keep alive-a "miffy" plant, to use an Englishhorticultural term. A second factor that makesFranklinia tricky to grow is its requirement foracid soil-with a pH between 5 and 6-an observationthat w<strong>as</strong> not <strong>document</strong>ed until 1927.23This reconstruction of Franklinia’s long historyat the Arboretum makes it obvious that muchof the horticultural knowledge that we take forgranted today exists only because of the workof persistent staff members constantly pushingthe limits of what they could cultivate. TheFranklinia growing today on Bussey Hill area living legacy to the untiring efforts of JohnBartram and his son William, Thom<strong>as</strong> Meehan,Charles Sargent, and John Jack. Indeed, on acrisp fall day m October, a knowledgeable visitorto the Arboretum can sense the presence ofthese men amidst the stunning display of purewhite flowers and rich crimson foliage. Theywere able to accomplish great things becausethey believed in the importance of their workand stuck with it through all kinds of adversity.Without their concerted efforts, Frankliniamight never have survived into the twenty-firstcentury, let alone come into flower on BusseyHill in the year 2005.Endnotes’ Historic Bartram’s Garden. 2000. Franklinia Census.Special publication of the John Bartram Association2F. Harper, ed. 1958. The Travels of Wilham Bartram,Naturahst’s Edition New Haven: Yale UmversityPress; J. Ewan. 1968. Wilham Bartram. Botanicaland Zoological Drawings, 1756-1788 Philadelphia:American Philosophical Society.3F. Harper and A. N. Leeds. 1937. A supplementarychapter on Frankhma alatamaha. Bartonia 19: 1-13.4J. Fry. 2000. Franklmia alatamaha, a history of that"very curious" shrub. Bartram Broadside, Spring2000.5C. S. Sargent. 1889. Gordoma pubescens. Garden andForest 2(96): 6166C. E. Kobuski. 1951. Studies in the Theaceae, XXI: thespecies of Theaceae indigenous to the Umted States.Journal of the Arnold Arboretum 32: 123-138.’ H. Marshall 82/G~: 6. 1785 Arbustum Amencanum: theAmencan Grove. Joseph Crukshank: Philadelphia.J. J. T. Fry. 2003. More on Frankhm<strong>as</strong> The AmericanGardenerW. Wynne 1832. Gardener’s Magazme (London) 8:272-277.10C. S. Rafinesque. 1832. New plants from Bartram’sBotamc Garden. Atlantic journal 1, 2: pp 79-80." D. J. Browne 1846. Trees of America. Natme andForeign New York. Harper Brothers.’z T. Meehan. 1853 The Amencan Handbook ofOrnamental Trees. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo,and Co.’3"J. Meehan. 1890. Gordoma Altamaha (pubescens/.Garden and Forest 3/133~: 445. See also J. Meehan.1888. Garden and Forest 1(36) : 429.J. Fry. 1996. Bartram’s garden catalogue of NorthAmerican plants, 1783. Journal of Garden History16.’S L. H. Bailey. 1916. The Standard Cyclopedia ofHorticulture, pp. 1587-88. New York: The MacmrllanCo.’~ T. Meehan. 1853. The Amencan Handbook ofOrnamental Trees. Philadelphia: Lrppmcott, Grambo,and Co."J. Meehan. 1897. In Bartram’s Garden. Meehans’Monthly 7’ 50.’n C. S. Sargent. 1890. Silva of North Amenca 1~ 45-4GHoughton Mifflin, Boston Frankhma is cl<strong>as</strong>sified <strong>as</strong>Gordonia altamaha in this work.1v J. Meehan. 1888. Garden and Forest 1(3G~: 429.z°C. S. Sargent. 1889. Notes. Garden and Forest 2(84)z’---480Noteworthy late-flowering shrubs.Garden and Forest 6(295): 436-437.22C. S. Sargent 1884. Notes. Garden and Forest 7(344):390.~F. V. Coville. 1927. The effect of alummum sulfate onrhododendrons and other acid-soil plants. SmithsonianInstitution 1926 Annual Report, W<strong>as</strong>hington, D.C.,pp.369-382.AcknowledgmentsThe author would especially like to thank Joel T.Fry, Curator of Historic Collections at Bartram ’sGarden, for directing him to the articles in Garden andForest describing the Arnold Arboretum’s efforts atcultivating Frankhnia.Peter Del Tredici is a senior research scientist at theArnold Arboretum.

10on anything else." Beginning in the spring of1900, Wilson, working from a map provided byHenry, searched a large area of central Chinaonly to discover that the one tree of knownlocation had been cut for lumber. Undeterred, heeventually found several fruiting trees, and hesent hundreds of seeds back to England. The firstplant came into bloom at the Veitch Nursery in1911. However, unbeknown to both Wilson andVeitch, Pere Farges had in 1897 sent 37 seeds tothe arboretum of Maurice de Vilmorin in LesBarres, France. In 1899, one of those seeds germinatedand the resulting tree bloomed in 1906.So even though Wilson could claim responsibilityfor broadly distributing the dove tree, thanksto the large quantities of seed he had gathered,the credit for introducing the first specimen tothe west belonged to Farges. Smarting from theloss of greater glory, Wilson wrote, "After mysuccessful introduction of Davidia in 1901, andits free germmation in 1902, I had yet one littlecup of bitterness to drain. "It is from the one plant germinated fromFarges’ seed that the outstanding specimenat the Arnold Arboretum (accession #5159*A~originated. The plant, a rooted layer, w<strong>as</strong>obtained by Charles Sargent and planted at theArboretum in 1904. Injured by severe cold earlym life, the tree resprouted from its b<strong>as</strong>e to formthe multi-stemmed specimen we know today.When it bloomed for the first time in 1931, thenArboretum director Oakes Ames, writing in theArboretum’s Bulletin for Popular Information,declared that the specimen w<strong>as</strong> notable more forits botanical novelty than for its beauty:We are told that in its native land, when ladenfrom top to bottom with enormous white floralbracts, some of them attammg a length of eightmches or more, D. mvolucrata presents a wonderful<strong>as</strong>pect. But from an aesthetic pomt of view ith<strong>as</strong> httle to recommend it. Its claim to a place inthe garden rests on the bizarre form rather thanthe beauty of the mflorescence.If he could see the fully mature specimen oftoday, Oakes Ames might very well revise hisopinion. Now over 30 feet in height, the treein bloom is without question an outstandingfeature of the Arboretum’s spring landscape(remember, though, the dove tree is an alternateyearbloomer). You can usually find it in fullThe distmctme bark of the dove treeflower on or about Lilac Sunday, perched on thewest-facing slope of Bussey Hill along ChinesePath near several other spectacular specimensof similar vintage. Interestingly, a few feet awaygrows a dove tree that originated from the seedcollected by Wilson for the Veitch Nursery andsent to the Arboretum <strong>as</strong> a sapling in 1911. Asomber reminder of failed expectations, the Wilsonspecimen (accession #14473*A) resides in theshade of stewarti<strong>as</strong> and h<strong>as</strong> never attained thephysical prominence of its nearby neighbor. Likemost dove trees in cultivation, both specimensare of the botanical variety Davidia involucratavar. vilmoriniana, which differs from the speciesin having smooth rather than felted leaves.Still rare in gardens, Davidia is unrivaledamong hardy trees for historical, botanical, andhorticultural distinction. More than a one-se<strong>as</strong>onornament, it offers attractive mottled, reddishgraybark along with three- to five-inch leavesthat are a bright green and usually free of pestsor dise<strong>as</strong>e. The large round fruits, roughly oneand-one-halfinches in diameter, dangle singlyand often persist into the winter. Althoughonce established it is hardy to USDA zone 6,young plantmgs may require some protection inextreme winters. Ple<strong>as</strong>e note that if you plant <strong>as</strong>eedling from the Arboretum plant sale, you willwait up to ten years before seeing a bloom. Yetaccording to E. H. Wilson, the flowers of "themost interesting and beautiful of all trees of thenorth temperate flora" are well worth the wait.Richard Schulhof is deputy director of the ArnoldArboretum.

Ilex pedunculosa: The Longstalk HollyPhyllis AndersenInIlectingthe fall of 1892, during his first plant col-trip to Japan, Charles Sprague Sargentadmired a distinctive holly growing alongthe Nag<strong>as</strong>endo Highway, the famous mountainroad connecting Kyoto to Edo (now Tokyo). Hefound the plant growing both in the wild and inthe gardens of local inns, sometimes <strong>as</strong> a shrubonly two to three feet high and sometimes <strong>as</strong>a well-formed tree <strong>as</strong> tall <strong>as</strong> twenty to thirtyIts ovalfeet, with a narrow, round-headed top.leaves were a lustrous, dark green. But its mostdistinctive feature w<strong>as</strong> its long flower stems,or peduncles, which in the early fall droopedunder the weight of bright red fruit,the stems of fruiting cherry trees.not unlikeThe plant that had so impressed Sargent w<strong>as</strong>Ilex pedunculosa, the longstalk holly, firstdescribed for publication by the Dutch botanistFriedrich Anton Wilhelm Miquel in 1868. Itsaffinity with the hollies of New England made itof particular interest to Sargent, who w<strong>as</strong> committedto researching the similarities betweenthe flor<strong>as</strong> of e<strong>as</strong>tern Asia and e<strong>as</strong>tern Northw<strong>as</strong> further enhancedAmerica. The plant’s appealby Sargent’s desire to add plants of significantornamental value to the Arnold Arboretum’scollection. Later Sargent hired the British plantexplorer E. H. Wilson to further pursue the studyof Asian flora, and in 1907 Wilson sent seeds ofI. pedunculosa from China back to Boston.With lustrous leaves, bnght red frmt, and dependable hardmess throughout zone 5, the longstalk holly is abroadleaf evergreen that fewm New England can nval

14it "the bionic plant.") Frost or freezedamage to soft tip growth is e<strong>as</strong>ilydifferentiated from the symptoms ofredfire fungus. Redfire usually progressesfrom older to younger tissuealong a branch and up the tree.Insects are seldom a problem. Sincebagworms, which plague Leylandcypress in some are<strong>as</strong>,are not normallya pest of Cryptomeria, the fullsizeforms of Japanese cedar makean excellent alternative to Leylandcypress.Almost all forms of Japanese cedarcan be propagated e<strong>as</strong>ily from cuttings,which are best taken fromNovember through February but willroot at almost any time of year ifmature, hardened wood is available.Full-size cultivars like ’Yoshino’ willusually root even if no visible maturewood is available (albeit more slowly/,but avoid cutting during activeflushes of growth. Wound cuttingsminimally and treat them with moderateconcentration of rooting hormonesand place them under mist. (Inwinter, bottom heat can help.) As onemight expect in a hydrophilic plant, itroots f<strong>as</strong>ter at higher mist frequenciesthan those used for other conifers.The cultivar ’Yoshino’ is a fullsizedform that will reach 50 feetquite rapidly and retain a uniform,. 1 11 . ~ I ~ I . Imormamy pyramiaainamt mtn tnetype species’ cloudlike silhouette. It is the mostreliably cold-hardy cultivar and the best choicefor zone 6 gardens. A beauty <strong>as</strong> a specimen, innumbers it will also rapidly make a handsomescreen. ’Yoshino’ h<strong>as</strong> been used to create a lushbackground to the waterfall and mountain pathsof Tenshin-en, the Japanese garden at Boston’sMuseum of Fine Arts.ReferencesBailey Hortorium. 1976. Hortus Third MacMillan Pub.Co. 341Den Ouden, P, and B. K. Boom. 1965. Manual ofCultivated Conifers The Hague, MartinusNi~hoff, Netherlands.-=>0>--""’" ~~JCryptomeria japonica growing in a nursery in Maryland.Dirr, M.A. 1990. Manual of Woody Landscape Plants.Stipes Pub. Co.Hornibrook, M. 1938. Dwarf and Slow-Growmg Comfers,2nd ed. Theophr<strong>as</strong>tus, Noble.Krussmann, G. 1985. Manual of Cultivated Comfers.Timber Press.Van Gelderen, D.M., and I. R. P. van Hoey Smith. 1986.Conifers Timber Press.Vidakovic,M. 1991 Com fers, Morphology and Vamation.Graficki Zavod Hrvatske, Zagreb.Kim Tripp, a Putnam Fellow at the Arnold Arboretum,1994-1995, is now director of the New York BotanicalGarden.

Microbiota decussata: A Versatile ConiferNancy Rose~ / /~ V / icrobiota growing decussata is an elegant, lowevergreenshrub that is finding-L 1 its way into more gardens every year.Its combmation of graceful form, attractive foliage,cold hardiness, and landscape value earnedit a 1998 Cary Award, which annually honorsoutstanding woody plants for New Englandgardens. Microbiota decussata h<strong>as</strong> gamed favorwell beyond New England, however, and gardenersin many states may find it an excellentaddition to their landscapes.This unique conifer h<strong>as</strong> a remote and limitednative range: the Sikhote Alin mountain rangein the southe<strong>as</strong>tern leg of Siberia, bordering theSea of Japan. It is often found growing abovethe treeline, frequently in <strong>as</strong>sociation withPinus pumila, a shrubby pine species, and inshrubland are<strong>as</strong> m the upper mountain valleysof the region. The species w<strong>as</strong> first recorded bybotamst I. K. Shishkin in 1921, in the mountainsnorthe<strong>as</strong>t of Vladivostok, and named by botanistV. L. Komarov in 1923.Despite being discovered and named over 80years ago, Microbiota decussata is often describedin garden catalogs <strong>as</strong> "new" or "recently discovered."This claim is actually not so far off, sincethere w<strong>as</strong> a significant lag between the plant’sdiscovery and its introduction to gardeners inNorth America. The species w<strong>as</strong> not mentionedin Hortus Third, the 1976 edition of the venerabletome that lists cultivated plants of the U.S.and Canada. It h<strong>as</strong> slowly become more availablein the nursery trade over the p<strong>as</strong>t 20 years, however,and is clearly now here to stay.Microbiota decussata is the lone species in itsgenus, but it is not without relatives. It belongsto the cypress family, a wide-ranging group ofconiferous trees and shrubs that includes wellknownevergreen genera like Jumperus, Thu~a(arborvitae), and Chamaecyparis (false cypress).Taxonomically, M. decussata is perhaps mostsimilar to Platycladus orientahs (orientalarborvitae), but the two are different enough tomaintain their separate designations.With a height at maturity averaging only tento eighteen inches in most landscape plantings,the plant’s low, widespreading form resemblesthat of spreading junipers. (Interestingly,native Siberian specimens with heights rangingfrom eight inches to over three feet have beenreported, indicating that it may be possible toselect shorter or taller types from wild populations.)Many long stems radiate horizontallyfrom the plant’s crown, creating a spread thatcan reach ten feet or more. As these mainstems grow outward, numerous gently archingsecondary branches rise from them, developingfirst near the center of the plant. Since all ofMicrobiota decussata’s branch tips nod downward,the result is a wonderfully graceful, softlylayered appearance. The nodding branch tips arecharacteristic of the species and make it e<strong>as</strong>y todifferentiate it from spreading jumpers, whosebranch tips tend to flare upwardThe individual branchlets of Microbiotadecussata are arranged in lacy, fernlike sprays,much like those of arborvitae; no doubt thisaccounts for another common name for theplant, "Russian arborvitae." The branchlets arecovered with closely pressed, scale-like needlesarranged in opposite pairs. The pairs emerge at90-degree angles from each other, resulting in aneatly layered, four-ranked arrangement termeddecussate-hence the plant’s specific epithetdecussata. The individual needles are tiny (oneeighthinch or less), with convex outer surfaces,a triangular shape, and tips that feel slightlysharp when you run a finger down the branchletbackwards, from tip to b<strong>as</strong>e.The foliage can safely be described <strong>as</strong> a ple<strong>as</strong>antbright green during the growing se<strong>as</strong>on butdescribing its winter color is a highly subjectiveexercise. Those who don’t like the plantuse terms like "dull brown" or "dirty purplish

16Microbiota decussata h<strong>as</strong> a natural affimty for rocksbrown" while those who find it appealingdescribe the color <strong>as</strong> anything from "magnificentcopper" to "rich bronze" or "burgundy purple. "Beauty (and color descriptions) are clearly in theeye of the beholder. Plants grown where theyare shaded during the winter show less bronzingthan those in full sun. Some plants seem to greenup more quickly than others in the spring; perhapsin the future nursery growers should selectfor this trait in new cultivars.Being a conifer, Microbiota decussata does ofcourse bear cones, but they are so small <strong>as</strong> to behardly noticeable. Male and female cones occuron the same plant-in other words, it is monoecious.The male cones are the smaller, aboutone-sixteenth to one-eighth inch long; theyrele<strong>as</strong>e pollen in the spring. Female cones, aboutone-eighth inch long, consist of a <strong>single</strong> nakedseed held within two to four leathery scales; theseeds mature in late summer or early autumn.It is a very cold hardy plant, surviving throughUSDA zone 3 (average annual minimum temperatureminus 30 degrees to minus 40 degrees F). Infact, it seems to prefer cooler climates and mayfail to thrive in are<strong>as</strong> warmer than USDA zone6. Excellent soil drainage is a must, but <strong>as</strong> long<strong>as</strong> the site is well drained the plant can adaptto a range of soil types and pH levels. It growswell in evenly moist soil, but once establishedit also tolerates drier conditions. An inch or twoof organic mulch-wood chips,shredded bark, or pine needlesappliedin a wide circle around theplant will help keep the root zonecool and moist. So far M. decussatah<strong>as</strong> not shown susceptibilityto Phomopsis tip blight, a commondise<strong>as</strong>e problem for some ofthe spreading junipers, and appearsto be free of other major dise<strong>as</strong>e orinsect problems.When Microbiota decussat<strong>as</strong>tarted to become available innurseries it w<strong>as</strong> often touted <strong>as</strong>extremely shade tolerant. Thisw<strong>as</strong> seen <strong>as</strong> a great advantage overspreading junipers, which growpoorly and exhibit thinning foliagein shade. More experience withM. decussata h<strong>as</strong> led to modified recommendations,however. It too is prone to limited growthand thinner foliage when grown m dense, fullshade, so the better choice seems to be partialshade or full sun exposure. In regions with hotsummers this Siberian native appears to benefitfrom partial shade, especially in the afternoon.Microbiota decussata is usually sold in containersat nurseries and garden centers, butis also available from a number of mail ordergarden catalogs. While it can be grown fromseed, most commercial propagation is by rootedstem cuttings.This is a plant with multiple uses in the landscape.Because of its low height and wide spread,it makes an ideal evergreen groundcover, its ferny,layered foliage creating a three-dimensionaleffect that is lacking in many groundcovers. Ith<strong>as</strong> a natural affinity for rocks, whether sweepingaround the b<strong>as</strong>e of a well-placed decorativeboulder or spilling over the top of a stone retamingwall. Attractive alone, it also combines wellwith small deciduous shrubs, herbaceous perennials,and other conifers. Even its bronze wintercolor shows to advantage when contr<strong>as</strong>ted withthe dark green foliage of evergreens, the colorfulfruit of shrubs like Ilex verticillata ’Red Sprite’,or the light tones of ornamental gr<strong>as</strong>ses.For a note about the author, see page 25.

Chionanthus retusus: The Chinese Fringetree°Peter Del Tredici ~ jianhua LiTdescribeTandsome is a word often used tothe Chinese fringetree~. -L (Chionanthus retusus). Whenplanted in the open, this species developsinto an elegant small tree, twentyto thirty feet high with approximatelythe same spread. A century-old specimenat the Arnold Arboretum is abouttwenty feet tall by thirty feet wide, andwhen in bloom from late May throughmid June is totally covered with showy,white flowers. It is no exaggeration tosay that this tree is capable of puttingon one of the Arboretum’s best floraldisplays. The blue-purple fruit, whichto Octo-a second se<strong>as</strong>on of interest.Chinese fringetree is more tree-likeand graceful than its straggly Americancousin, C. vmginicus, and is not nearlyso late to leaf out in the spring.The species h<strong>as</strong> a broad distribution mAsia, where it shows considerable variationin its growth habit. In cultivationmatures from late Septemberber, providesat the Arnold, some specimens are multistemmed,while others-especiallythose raised from Korean seed-are distinctly<strong>single</strong>-stemmed. The plant seemsto have broad ecological adaptability,growing equally well in the warm, dryclimate of southern California (USDAzone 9) and the cold, moist climates ofNew England (USDA zone 5). ( When young, the Chinese fringetree’s barkis a pale buff color, peeling off in papery strips.On mature trees, the bark is tight, with distinctridges and furrows. The lustrous leavesare elliptic to ovate in shape, three to eightinches long and one-and-one-half to four incheswide. The white flowers, each with four straplikepetals, are about an inch across and giveoff a delicate fragrance. They are produced atAn eighteen-year-old specimen of Chionanthus retusus growmgArnold Arboretum. Note the smgle-stemmed growth habit that h<strong>as</strong>developed without prunmg.the ends of the branches and completely hidethe foliage when the tree is in bloom. In NewEngland the fall color, being pale yellow, ishardly spectacular; in warm climates, thereis no fall color to speak of and green leavesstay on the tree through December. It is adaptablein its environmental responses, beingtolerant of full sun to partial shade, moderatesummer drought, and a wide range of soil con-at the

18 sThe showy flowers and blue-purple fruit of Chionanthus retusus.ditions. It is generally not bothered by insectpests or dise<strong>as</strong>es.The Chinese fringetree belongs to the genusChionanthus, which w<strong>as</strong> described by CarlLinnaeus m his Genera Plantarum ( 1737, 1754).The name w<strong>as</strong> b<strong>as</strong>ed on the American fringetree,which had been introduced to Europe before1736. Like the Chinese fringetree, Chionanthusvirginicus produces a profusion of showy, whiteflowers in spring, which explains Linnaeus’choice of name for the genus=( chion snow;=anthos flower).The taxonomic history of the genus is alsointeresting. In 1788, Swartz described a small,evergreen, Jamaican tree with small corolla lobes,naming it Thouinia to commemorate the Frenchgardener Andre Thouin (1747-1824). However,Linnaeus had already used this name in 1781.Accordingly, Swartz gave his new genus a differentname, Linociera, in honor of a sixteenthcenturyFrench physician, Geoffrey Linocier.Between 1791 to 1976 many species of Linocierawere described from both the old world and thenew. In 1976, William Stearn proposed the unionof Linociera and Chionanthus. The difficulty ofdistinguishing species of Loniciera and Chionanthushad been recognized <strong>as</strong> long ago <strong>as</strong> 1860 byGeorge Thwaites, who suggested the two generabe merged but did not present a formal proposal.Thus, prior to 1976 botanists generally referreddeciduous species with big flowers (corolla 1.5to 4 cm~ to Chionanthus and evergreen specieswith small flowers (corolla less than I cm) toLinociera. However, a small-flowered Ecuadorianspecies (L. pubescens) is a deciduous treewhile a deciduous Florida species (C. pygmaeus)h<strong>as</strong> small flowers. Other morphological traitsoverlap between Chionanthus and Linociera,and no clear-cut differences separate the two.Therefore, Stearn’s proposal to unite them h<strong>as</strong>been widely accepted in the botanical community.The combined group is referred to <strong>as</strong> Chionanthusbecause this name w<strong>as</strong> published earlierthan Linociera. The union h<strong>as</strong> led to the transferof numerous species from Linociera to Chionanthuseven though genetic studies have notbeen performed to determine the evolutionaryrelationships of deciduous and evergreen species.Modern DNA research will surely help clarifythe taxonomy of Chionanthus and Linociera.ReferencesDirr, M. A. 1998. Manual of Woody Landscape Plants, 5thed. Stipes Publishing, Champaign, IL.Gilman, E. F., and D. G. Watson. 1993. Chionanthusretusus, Chinese Frmgetree. Fact Sheet ST-160.Department of Environmental Horticulture,Flonda Cooperative Extension Service, Instituteof Food and Agricultural Sciences, <strong>University</strong>of Florida.Peter Del Tredici is a senior research scientist and JianhuaLi is a taxonomist at the Arnold Arboretum.

---------------------------Beach Plum: A Shrub for Low-MaintenanceLandscapesRichard H. Uva and Thom<strong>as</strong> H. WhitloweachBplum (Prunus maritimaJ,shrub native to the Atlanticco<strong>as</strong>t, is familiar to beachgoersfrom southern Maine through Maryland,where populations can be foundon and near the co<strong>as</strong>tal dunes. Sincecolonial times its fruits have been collectedin the wild for preserves andjelly and were reportedly used evenearlier by Native Americans. Nowadays,although beach plum is occ<strong>as</strong>ionallyfound in the nursery trade, it israrely grown in cultivation. Demandis incre<strong>as</strong>ing for native species thatcan thrive in low-maintenance, poornutrientlandscapes-reclamationsites, roadsides, sand dunes in need ofstabilization-and beach plum is an excellentcandidate to fill that need. By virtue of its showyspring flower display and colorful fruits, beachplum also warrants incre<strong>as</strong>ed use in more intensivelymanaged ornamental landscapes.Beach plums have extensive root systems, nodoubt an adaptation to a habitat that is characterizedby high wmds, blowing sand, unstable substrates,wind-borne salt, and soil that is low innutrients and water-holding capacity. It shouldbe noted that beach plum’s distribution is notlimited to sandy soils, however; it also thrivesunder cultivation on moist, rich soil <strong>as</strong> long <strong>as</strong>it h<strong>as</strong> good drainage and full sun. Today, jellyproduction from wild-growing shrubs is a smallbut thriving cottage industry in the Northe<strong>as</strong>t,and farmers are beginning to plant beach plumto make fruit more readily available.The horticultural literature of the 1940smentions several cultivars of beach plum thathad been selected for fruit production at thattime, but we have been unable to locate specimens.(If a reader knows of any still existing,Prunus mantima.we would appreciate hearing about it.) Morerecently, the Cape May (New Jersey) PlantMaterials Center of the Natural Resources ConservationService (NRCS) h<strong>as</strong> rele<strong>as</strong>ed a selectionknown <strong>as</strong> ’Ocean View’; it w<strong>as</strong> developedfor stabilizmg co<strong>as</strong>tal sand dunes, but couldbe used in any sunny, well-drained location.The information below h<strong>as</strong> been adapted fromNRCS’ "Notice of Rele<strong>as</strong>e of ’Ocean View’."1/A New Cultivar of Beach Plum’Ocean View’ is a cross of four wild-growingstrains from Delaware, New Jersey, and M<strong>as</strong>sachusettsthat were selected for their exceptionalseedling vigor, foliage abundance, dise<strong>as</strong>e andinsect resistance, leaf retention, fruit production,and cold tolerance. It h<strong>as</strong> been field-testedon sandy co<strong>as</strong>tal sites from North Carolina toMaine and is recommended for use withinzones 5b to 8b.This new cultivar is an upright, denselybranched shrub with pale green foliage. Itsalternate, serrated leaves are elliptical to ovate

20Beach plum on Cape Cod, M<strong>as</strong>sachusetts.in shape and range from about 1.5 to 2.5 inchesin length and half that in width. In early spring,before the leaf buds unfold, clusters of snowywhiteblooms emerge to cover the crown of theshrub, creating a frothy spl<strong>as</strong>h in the otherwisegray landscape. The individual flowers, onlyabout one-quarter to three-quarters of an inchin diameter, take on a pink hue before droppingoff to be replaced by the emerging leaves. Theround fruits ripen to a bright red in late Augustor early September.’Ocean View’ seedlings should be planted ata depth of approximately two inches above theroot collar on stable sand dunes and no deeperthan the root collar on inland soils. Fertilizationhelps with good establishment and vigorousplant growth. Recommended spacing of plantsvaries with intended use: to provide a dense barrierof protective vegetation, seedlings shouldbe placed about four to six feet apart, and whenused inland for residential are<strong>as</strong> or wildlife plots,about six to eight feet apart.The availability of this new cultivar givesgardeners in the Northe<strong>as</strong>t an opportunity toenjoy a bit of native beach vegetation in theirbackyards without adding to their list of maintenancet<strong>as</strong>ks. And if you don’t care to use the fruityourself for jelly, wildlife will appreciate it.ReferencesJames B. Newman and Cecil B. Currin. 1994. Noticeof rele<strong>as</strong>e of ’Ocean View’ beach plum. U S.Department of Agriculture, Soil ConservationService, Technology Development andApphcation, Ecological Science, W<strong>as</strong>hington,D.C. http://www.plant-materials.nrcs.usda.gov/njpmc/rele<strong>as</strong>es.htmlFor information on beach plum fruit crop developmentple<strong>as</strong>e visit our website: www.beachplum.cornell.edu See also <strong>Arnoldia</strong> 62 4, "Tamingthe Wild Beach Plum" by R. H. Uva.Dr. Uva and Professor Whitlow have collaborated on thedevelopment of beach plum <strong>as</strong> a fruit crop for severalyears at Cornell <strong>University</strong>.

Calycanthus chinensis: The Chinese Sweetshrubjianhua Li ~ Peter Del Tredicialycanthus withchinensis~ beautiful deciduous shruba narrow geographicis adistribution m Zhejiang Province,China. It grows up to ten feet tallwith a broad profile. The leavesare oppositely arranged with shortpetioles and are glossy green witha touch of roughness on the uppersurface. In the Boston area its noddingflowers appear in mid to latespring. Appearances notwithstanding,the sepals and petals are notdifferentiated (therefore termedtepals): the outer tepals are a silkywhite with a tinge of pink and adiameter of two to three inches,while the inner tepals are a waxypale yellow to white with maroonmarkings. Unlike the native Calycanthusfloridus the flowers arenot fragrant and are pollinated bysmall beetles.Tepals and stamens occupy therim of a deep floral cup; the ovariesare attached to the side of the cup.The fruits, top-shaped with manyseeds, overwinter on the shrub. Inits natural habitat, it grows underneatha canopy and therefore is bestcultivated in partial shade withwind protection and good soil moisture.In 1998 Michael Dirr describedit <strong>as</strong> "a unique plant but doubtfully<strong>as</strong> worthy <strong>as</strong> Calycanthus floridus."Opinions may vary <strong>as</strong> to the species’comparative garden worthiness, butwhere evolutionary and taxonomic histories areconcerned, C. chinensis definitely provokes moreinterest. As a practical matter, the species is rarein the wild and needs our help to survive.The pendant flowers of Calycanthus chinensis have an unusual, waxy texture.Calycanthus chinensis belongs to Calycanthaceae,which includes two genera and aboutten species.’ Chimonanthus (wintersweet) isthe other genus; it differs from Calycanthus in

-22In this closeup of a Calycanthus chinensis flower, the mnerand outer whorls of tepals are clearly msible.many features, including morphology, woodanatomy, pollen, and embryology. Species ofChimonanthus are literally called "waxyprunus" in Chinese because it blooms in winterwith waxy yellow flowers that resemble cherries.C. chinensis w<strong>as</strong> first described <strong>as</strong> a species ofCalycanthus2 and w<strong>as</strong> later recognized <strong>as</strong> <strong>as</strong>eparate genus, Sinocalycanthus.3 Morphologically,this species differs from other species ofCalycanthus in its white flowers and dimorphic(two forms), broadly ovate tepals. Therefore,many authors recognize this species <strong>as</strong> a separategenus from Calycanthus.4 However, we prefer totreat this plant <strong>as</strong> a species of Calycanthus forthe following re<strong>as</strong>ons.First, it is rare that species of different generahybridize successfully, but Calycanthus chinensish<strong>as</strong> been successfully crossed with C. floridusand C. occidentalis.s Second, differencesin DNA sequences are few among C. floridus,C. occidentalis, and C. chinensis.6 Third, thistreatment shows Calycanthus’ disjunct distributionin e<strong>as</strong>tern Asia and North America. Anda serious one-isa final consideration-hardlythe tongue twisting required to pronounce thelong hybrid name Sinocalycanthus.When Calycanthus chinensis w<strong>as</strong> first introducedinto cultivation in North America in theearly 1980s, its hardiness w<strong>as</strong> unknown. ButThe flowers of our natme e<strong>as</strong>tern sweetshrub differ fromthose of their Chinese relatme both in form and fragrance.experience at the Arnold Arboretum h<strong>as</strong> shownthe plant to be fully hardy in USDA zone 6, havingsurvived temperatures of minus 10 degreesF in 2003. The plants being offered for sale wereraised from seeds produced by plants growingoutdoors at the Arnold Arboretum since 1998.The parent plants were raised from seeds collectedat the Nanjing Botanical Garden in 1994.Endnotes~‘ Li, J. Ledger, T. Ward, and P. Del Tredici. 2004.Phylogenetics of Calycanthaceae b<strong>as</strong>ed on molecularand morphological data, with a special referenceto divergent paralogues of the nrDNA ITS region.<strong>Harvard</strong> Papers m Botany 9: 69-83.2W. C. Cheng and S. Y. Chang. 1963. Scientia Srlvae 8: 1.3--. 1964. Genus novum calycanthaceaearumchmae onentahs Acta Phytotaxonomica Smica 9:135-138.’L Li 1989. Cytogeographical study of CalycanthusLmnaeus. Gmhaia 9: 311-316; Y. Li and P. T. Li.2000. Cladistic analysis of Calycanthaceae. journalof Tropical and Subtropical Botany 8: 275-281; M.Dirr. 1998. Manual of Woody Plants, 5th ed. Stipes,Champaign, IL.5 F. T. L<strong>as</strong>seigne, P. R. Fantz, and J. C. Raulston. 2001.~ Smocalycalycanthus raulstonn (Calycanthaceae/:A new mtergeneric hybrid between Sinocalycanthuschinensis and Calycanthus flondus HortScience36: 765-767; Todd L<strong>as</strong>seigne, pers. comm.‘ Li et al. 2004.7G. H. Straley. 1991. Presenting Sinocalycanthuschinensis. Arnoldza 51 / 118-22.Jianhua Li rs a taxonomist and Peter Del Tredici is a semorresearch scientist at the Arnold Arboretum

Rhus trilobata: Worthy Plant Seeks Worthy NameNancy Roseaddledsumac,with common names like skunkbush,stinking sumac, and ill-scentedRhus trilobata is clearly a shrubin need of a good public relations agent. Thoseunflattering names refer to the strong scent itsfoliage and stems emit when crushed. Ignorethe unappealing monikers, and you will findthat its ornamental and environmental <strong>as</strong>setsare more than sufficient to make R. trilobata avaluable landscape plant.Rhus trilobata h<strong>as</strong> a wide native range in westernNorth America, reaching from the Canadianprovince of S<strong>as</strong>katchewan south to Tex<strong>as</strong> andMexico but skipping the moist co<strong>as</strong>tal are<strong>as</strong> ofthe Pacific Northwest. It grows in many ecologicalregions, from the Great Plains gr<strong>as</strong>slands tomountain shrubland, chapparal, and forest are<strong>as</strong>,and is found in <strong>as</strong>sociation with numerous speciesof deciduous and evergreen trees and shrubs<strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> with gr<strong>as</strong>ses and forbs.Within its native range this deciduous shrubcan grow from two to twelve feet tall, withfour to six feet being typical in most landscapesettings; its height is determined in partA lemonade-hke drmk can be made from the attractme red fruits.

24by moisture availability. Its formranges from irregularly upright tomounded, with numerous slender,branched stems rising upward fromthe crown. These flexible youngstems have been used in b<strong>as</strong>ketryby Native Americans, accountingfor one of the plant’s lesser-knowncommon names: b<strong>as</strong>ketbush. Shootsalso emerge from the extensive systemof woody rhizomes that spreadlaterally below ground, creatinga dense thicket that in width canequal two or more times the plant’sheight. A taproot together with alarge m<strong>as</strong>s of more shallow fibrousroots anchor the shrub.The leaves of Rhus trilobata,compound and alternately arrangedon the branches, consist of threesubsessile (nearly stalkless) leafletsthat are generally ovate or rhomboidalin shape. The terminal leafletis the largest, with a length ofone to two-and-one-half inches; it isoften distinctly three-lobed (hencethe specific epithet trilobata) butat times displays only shallow ornegligible lobing. Its leaf marginsare coarsely toothed, most teethbeing rounded although some areslightly pointed. Leaf surfaces,while variably pubescent on youngleaves, usually become smoothand slightly glossy <strong>as</strong> the foliagematures. Medium to dark green in summer,the leaves often develop excellent fall foliagecolor that ranges from yellow to orange, red, andreddish purple.In spring Rhus trilobata blooms before itsfoliage appears, the flowers emerging fromshort, catkin-like spikes borne at the branchtips. Individual flowers may be unisexual orbisexual, with both types occurring on mostplants. Only about one-eighth inch long, theyare light yellow or greenish yellow and have fivepetals. The fruit is a red, subglobose (not perfectlyround) drupe about one-quarter inch long,slightly hairy and a bit sticky on the surface andcontaining a <strong>single</strong> dark brown nutlet. MatureNew leaves are downy, usually becommg smooth and glossy mth matumty.In fall the green gives way to yellows, orange, reds, and reddish purple.fruits have a tart t<strong>as</strong>te; a tangy lemonade-likedrink can be made by steeping them in water.The fruits, leaves, stems, and roots of R. trilobatahave been used for various culinary,medicinal, and other utilitarian purposes bynative cultures in the western United States.Six naturally occurring varieties of Rhustrilobata are recognized: var. anisophylla, var.pilosissima, var. quinata, var. racemulosa, var.simplicifolia, and var. trilobata. R. trilobatavar. trilobata-so named to indicate that it displaysthe species’ typical morphology-coversthe entire native range. The other varieties varyin such features <strong>as</strong> height, growth habit, leafsize and form, and fruit pubescence. Where the

25ranges of these varieties overlap, plants often showmtermediate morphological characteristics.Rhus trilobata looks very much like its morewidely available cousin, R. aromatica. Theresemblance is close enough that skunkbushw<strong>as</strong> previously listed in taxonomic references <strong>as</strong>a variety (R. aromatica var. trilobata) rather than<strong>as</strong> a separate species. Morphological differencesbetween the two are few. R. trilobata’s leaves,flowers, and fruits are generally smaller andits terminal leaflets more distinctly lobed thanthose of R. aromatica, but these features showenough variability to make them unreliable <strong>as</strong>diagnostic tools. It is in geographic distributionthat the two species show clear differences, withR. trilobata occupying a western range whileR. aromatica is found e<strong>as</strong>t of the Great Plains.A corresponding difference is found in theirenvironmental adaptations: R. trilobata toleratesfairly dry, alkaline soils while R. aromaticaprefers moist, slightly acidic sites. The leaves ofboth species emit a distinct odor when crushed,but the somewhat less pungent scent of R. aromaticaearned it the common name "fragrantsumac" while R. trilobata is stuck with its lessthan-flatteringnicknames.As its wide natural range might indicate, Rhustrilobata is an adaptable plant. It grows well insomewhat alkaline soils but also appears to tolerateneutral to slightly acidic soils. Most referenceslist it <strong>as</strong> winter hardy to USDA zone 4(average annual minimum temperature minus20 to minus 30 degrees F), but the hardiness ofindividual plants is likely to vary dependingon seed provenance. It thrives in either full sunor partial shade, but fall foliage color is usuallybetter in full sun.Because it is well adapted to drier climaticconditions, Rhus trilobata is an excellent choicefor xeriscaping. Annual precipitation in most ofits range averages just 10 to 20 inches; by contr<strong>as</strong>t,the average is 42.5 inches in Boston and29.4 inches in Minneapolis-St. Paul. In USDAregional evaluations, a seed-grown selection ofR. trilobata from Bighorn County, Wyoming,fared best at evaluation sites with drier climaticconditions. Specimens failed to thrive and/orshowed higher incidence of fungal leaf spots insites with poorly drained soils, higher rainfall,and higher humidity.Rhus trilobata can be propagated in severalways. One of the simplest is by root (rhizome)cuttings. In spring, sections of rhizome can bedug up, cut into sections, and potted or plantedin a propagation bed. Alternatively, softwoodstem cuttings taken in early to mid summer canbe rooted in a peat-perlite medium under mist.For seed propagation, the fleshy pulp should firstbe removed from the seeds of ripe fruits. Theseeds (nutlets) have a very hard coat that mustbe cracked by mechanical or chemical scarification,after which they can be planted directlyin a seedbed. Plants of R. trilobata can moste<strong>as</strong>ily be found in nurseries in western states,but several mail-order garden catalogs offercontainer-grown plants for sale.This sumac can be used effectively in severalways. Its dense network of roots and rhizomesmakes it an ideal plant for holding soil on steepslopes, banks, and terraces. It also works wellin large-scale m<strong>as</strong>s plantings since its suckeringhabit allows it to fill an area quickly. Its abilityto tolerate drought and grow in rocky or gravellysoil makes it a good choice for dry, difficultsites. New England gardeners should not be putoff by Rhus trilobata’s affinity for arid soils,however. As long <strong>as</strong> it is planted on a sunny,well-drained site where flooding is not a problem,it will do well in those hilly or rocky are<strong>as</strong>that are common in the Northe<strong>as</strong>t but less thanideal for more common garden shrubs. Onceestablished, R. trilobata requires little maintenance; pruning to control height and improveappearancecan be done <strong>as</strong> needed. With itsattractive spring flowers, colorful fruit, andbright fall color, R. trilobata is a worthy additionto native plant displays, naturalized gardens,commercial properties, and other sites in needof a tough, adaptable shrub.Nancy Rose is a horticulturist and educator with the<strong>University</strong> of Minnesota Extension Service. She h<strong>as</strong>been growing and evaluating woody ornamental plantsfor many years, most recently at the <strong>University</strong> ofMinnesota Landscape Arboretum and previously at theMorton Arboretum near Chicago. She is also a gardenwriter and photographer, writing a gardening column forthe Mmneapol1s Star-Tmbune and wriring and editmgfor several gardemng magazines. Nancy is co-author ofthe books Shrubs and Small Trees for Cold Chmatesand The Right Tree Handbook.

Demystifying DaphnesBob Hylandhavetime andbeen a fan of shrubby daphnes for a longdespite their reputation <strong>as</strong> persnicketyunpredictable garden plants. I love todrink in their heady fragrance when they arein bloom. My first encounter with the genusw<strong>as</strong> with Daphne odora (winter daphne)-to beexact,a handsome cultivar called ’Aureomarginata’.It’s a deliciously sweet-smelling shrub,very reminiscent to me of j<strong>as</strong>mine. Its leatheryleaves are evergreen, a deep, shiny green edgedwith yellow. The almost white flowers are anattractive reddish purple on the outside.to USDA zones 7 to 9.Daphne odora is hardyWith careful siting, a little extra winter protection,and some tender loving care, I w<strong>as</strong> able tocoax it into overwintering in my garden in Wilmington,Delaware. Later, in my San Franciscogarden, the generally frost-free, Mediterraneanclimate made the ~ob much e<strong>as</strong>ier; m fact, someof my snobbier gardening friends considered it abit pedestrian.Daphne serves <strong>as</strong> both the common name andgenus epithet of some fifty species of deciduous,semi-evergreen, or evergreen shrubs nativeto Eur<strong>as</strong>ia (Europe, N.Africa, and temperateand subtropical Asia). The genus is a memberof Thymelaeaceae (mezereum family), whichincludes about forty genera of deciduous andevergreen trees and shrubs native to temperateand tropical regions of both hemispheres. Otherlesser-known cultivated ornamental plants inthis family include Dirca and Edgeworthia.The plant’s name may have come from thenymph of cl<strong>as</strong>sical Greek mythology. As thestory is told, Daphne w<strong>as</strong> loved and relentlesslypursued by Apollo, the god of prophecy,music, medicine, and poetry, whose advancesshe tried to thwart. After praying for help toGaia, goddess of the earth, she w<strong>as</strong> changedinto a laurel tree and evaded her pursuer. It ismore likely, however, that the name comesfrom an Indo-European word meaning "odor. "The root and bark of Daphne are said to havebeen used for toothaches, skin dise<strong>as</strong>es, andeven cancer, which seems odd since all parts ofthe plant are poisonous.In the Northe<strong>as</strong>t several Daphne species arehardy and have long been cultivated for theirhandsome foliage and intoxicating fragrance.Daphne flowers are tubular and flare at themouth into four spreading lobes. They appearon small to mid-sized shrubs that make superbgarden plants. Their dense, broad, moundedform is particularly well suited to small, intimategardens where they can be viewed closeup,but daphnes have a place in any landscape. Theycombine nicely with many perennials that toleratesun or partial shade. Good bedfellows includelow-growing thymes and sedums, variegatedhakone gr<strong>as</strong>s (Hakonocloa macra ’Aureola’/,sedges jCarexj, host<strong>as</strong>, coral bells (Heuchera),and hardy geraniums. Most of their allegedunpredictability can be overcome with carefulplacement in the garden and good culture.I heartily agree with Michael Dirr and otherdaphne-philes-a <strong>single</strong> flowering se<strong>as</strong>on wouldjustify their use.Growing DaphnesDaphnes are widely thought to be unpredictableand subject to dying for no apparent re<strong>as</strong>on: many a gardening friend h<strong>as</strong> told me not toget too attached to one. It is true that daphnesdislike extremes of moisture or temperature.Their root systems are picky, preferring not tosit in water or to dry out. Moist but well-drained,humus-rich soil is ideal, and mulching helpskeep roots cool in summer. Some English gardenbooks suggest that daphnes do best in limestonesoils, but this h<strong>as</strong> not been my own experience.I recommend acidic to slightly alkaline soils. Atthe Arnold Arboretum, several Daphne speciesgrow well in acid soils of pH 4.5 to 5.Generally speaking, you can plant daphnesin full sun to partial shade, but the foliage, particularlyon the variegated leaves, does not liketo bake in hot summer sun-afternoon shade isideal. Daphnes also do not take kindly to trans-

27The variegated leaves of Daphne x burkwoodii ’Carol Mackie’.planting once established m the garden; it is bestto plant container-grown stock in a permanentlocation. Keep pruning to a minimum, with judiciousdeadheading and light tip pruning. Do nottry to rejuvenate plants by cutting back hardthiscan e<strong>as</strong>ily sound the death knell.Besides this b<strong>as</strong>ic knowledge, all that’s neededfor successful daphne culture is planning aheadand some extra tender loving care. Find just theright spot, take the time to prepare and amendthe soil, monitor moisture levels, provide a wintermulch over the roots, and daphnes will generallyflourish and bloom for many years.The Arnold Arboretum will offer the followingthree dazzling daphnes at their fall 2005plant sale.Daphne x burkwoodii ’Carol Mackie’This is one of the most striking of all daphnesforthat matter, of all variegated shrubs. A geneticmutation, or sport, of hybrid Daphne x burkwoodii(D. cneorum x D. cauc<strong>as</strong>lca/, this cultivarw<strong>as</strong> discovered and originally propagatedby Carol Mackie in her Far Hills, New Jersey,garden in 1962. Carol Mackie w<strong>as</strong> a p<strong>as</strong>sionategardener and a very active member and officer ofthe Garden Club of Short Hills and the GardenClub of America. She developed a deep mterestin unusual plants and a very keen eye for the rareand unusual.Her namesake cultivar is highly prized forits small, intensely green leaves that are handsomelyedged in a creamy white to golden yellow.In May and June in New England, the foliageis enhanced by rose-pink buds that unfold tostar-shaped, richly fragrant, pale pink flowersborne in dense, terminal umbels, two inches indiameter. Individual flowers are about a halfmchin diameter and are followed by small, red,drupehke fruits.’Carol Mackie’ matures into a dense, moundedshrub that ultimately reaches three to four feetm height and width. It exhibits a tough constitutionand is hardy to USDA zones 4 to 8; it w<strong>as</strong>once listed <strong>as</strong> a "Top Ten" ornamental plantin Vermont. Accordmg to Michael Dirr m thefifth edition of his Manual of Woody LandscapePlants, Daphne x burkwoodii ’Carol Mackie’survived minus 30 degrees F without injury inthe Umversity of Maine’s display gardens. In

.28more southerly parts of its hardiness range, theplant remains evergreen through winter.Tom Ward, co-director of living collections atthe Arboretum, holds D. x burkwoodii ’CarolMackie’ in high esteem. He reports that it h<strong>as</strong>performed well both at the Arboretum and inhis own New England garden. If you’ve had thesame success with’Carol Mackie’, you might trya newer cultivar, ’Briggs Moonlight’. Introducedby Briggs Nursery, Elma, W<strong>as</strong>hington, it offersthe reverse leaf variegation of ’Carol Mackie’,with creamy yellow centers and narrow, darkgreen margins.Daphne genkwa (Lilac Daphne)Daphne genkwa hails from China; it w<strong>as</strong> introducedinto cultivation in the United States in1843. An open, deciduous shrub with erect, slender,sparsely branched stems, it is a gem in thespring garden. Axillary clusters of two to sevenlovely, one-fourth-to-three-fourths-inch diameter,lilac-colored flowers bloom during Mayon naked stems of the previous year’s growth,just before and while new foliage is beginning toemerge. Floral fragrance is very subtle to nonexistent.Dry, ovoid fruits develop after flowering;they are grayish whiteand nothing to writehome about.Mid-green, one- tothree-inch-long leaves,lance-shaped to ovate,are arranged oppositely(occ<strong>as</strong>ionally alternately)on stems. This isunusual among daphnespecies, which normallysport alternatelyarranged leaves. Leavesare softly silky whenfirst unfurling.Daphne genkwa isDaphne genkwa.hardy to USDA zones5 to 7 and generallyI’ . 11. 11 , ...matures to three to four feet in height andwidth. Currently no specimens of D. genkwa areplanted out in the Arboretum’s living collections,but one-descendant of wild-collectedplants from the former Czech Republic -isgrowing in the nursery. The Arboretum’s plantDaphne x transatlantica ’Summer Ice’.records also indicate that wild-collected seed ofD. genkwa from China w<strong>as</strong> received from E. H.Wilson in 1907.Daphne x transatlantica ‘Summer Ice’Daphne x transatlantica is a newly found hybrid,the result of a naturally occurring cross betweenD. collina and D. cauc<strong>as</strong>ica (cauc<strong>as</strong>ian daphne).it combines the small stature and strong fragranceof D. collina with the fragrance and longblooming period of D. cauc<strong>as</strong>ica. D. x transatlanticais a compact, semi-evergreen, moundedshrub that blooms continuously in New Englandfrom May to frost with small, delightfully fragrant,white flowers. The late Jim Cross, founderof Environmentals Nursery in Cutchogue, LongIsland, is responsible for introducing this hybridinto the nursery trade. He originally sold it <strong>as</strong>a form of D. cauc<strong>as</strong>ica, but molecular studieslater proved it to be a hybrid that h<strong>as</strong> been namedD. x transatlantica.The cultivar ’Summer Ice’ grows into a wellbehaved,domed shrub that reaches three to fourfeet in height and width. The delicately variegatedleaves sport fine, creamy white edgessimilarto but more demure than D. burkwoodii’Carol Mackie’. Its spicy white flowers are borneabundantly at the ends of branches in late spring,followed by sporadic summer bloom and a strongfall show. ’Summer Ice’ is hardy to zone 5.Bob Hyland is co-owner and manager of Loomis CreekNursery, Hudson, New York, pubhc garden consultant,and former vice president of horticulture and operationsat Brooklyn Botanic Garden. He frequently writes aboutplants when not watering.

-pensylvamcum-hippoc<strong>as</strong>tanum-Russian--Bussey- -Center--Chinese--collection--Dana--Fall--Hemlock--Leventritt- -Weather-platyphylla-flondus-cvs.--flonda-kousa-officmalls-sawara-winter-genkwa-odora-x- - -"Agamst---"CalycanthusIndex to Volume 63Numbers m parentheses refer to issues, those m boldface to illustrations of the entnes."A Good Day Plant-Collecting inTaiwan," Rob Nicholson 1. 20-27Abies nephrolepis 3: 26Abies nordmanmana 4. 8Abraham J. Miller-Rushing, "HerbariumSpecimens <strong>as</strong> a Novel Tool forClimate Change Research," withDamel Pnmack et al.Acer alleghamensis 4: inside frontcover- negundo 1: 281: 281~ 28-platanoides- ru brum 1: 29Aceraceae 1: 28Adelges tsugae (HWA) 2: 33Aesculus 1: 3, 4-hippoc<strong>as</strong>tanum 1: 3, 4, 5cv. ’Baumanml’ 1: 3-pama 1: 3, 4, 5-x x carnea 1~ 3, 4, 5, 6"Agamst All Odds: Growing Franklmiain Boston" 4: 2-7Alisan National Scemc area [Taiwan]1: 23Alpinia speciosa 1: 24Amentotaxus Preserve [Taiwan] 1: 24Amentotaxus formosana 1: 22-25Ames, Oakes 4: 10Andersen, Phyllis, "Ilex pedunculosaThe Longstalk Holly" 4: 11-12Anemone ’Groene Ridder’ 1: insidefront coveramse, false 1: 10arbormtae, oriental 3: 41, inside backcover4: 15Arnold Arboretum 1: 32, 2: 16, 26,27Hill 4: 2, 6, 9for Tropical Forest Science3: 7Path 4: 2, 6, 9of e<strong>as</strong>tern Asian photographs3’ 34Greenhouses 2: 3; 3: 22Plant Distribution and Sale,1980-2005 4: 8Hill 2: 35-36, 37, 38Garden 1: 8--Phellodendron amurensis collection1: front and back coversStation Data-200363:2Astragalus 3: 14Bartram, John 3: 29; 4: 3, 7Bartram, William 4: 3, 4, 5, 7Bartram’s Garden 4: 4, 5"Beach Plum: A Shrub for Low-MaintenanceLandscapes," Richard HUva & Thom<strong>as</strong> H. Whitlow 4:19-20beach plum 4. 19, 20beautybush 4’ 8Betula ermannn 3: 263 : 25Bhthdale Romance [Nathaniel Hawthorne]3 : 28, 30Book of Fruit 3: 28box elder 1: 28Brook Farm, West Roxbury,29,30Browne, D J. 4: 4,buckeye 1: 3, 5- red 1: 3, 4, 5Bull, Ephraim Wales 2: 14, 15, 17MA 3:Caesalpmioideae 3: 6"Calycanthus chinensis The ChmeseSweetshrub," Jianhua Li & PeterDel Tredici 4: 21-22Calycanthus chinensis 4: 21, 221 : 4; 4: 21, 22Calhcarpa dichotoma ’Issai’ 4: insideback covercamphor tree 3: 4, 36"Capturing and Cultivating Chosenia,"Peter Del Tredici 3: 18-27Carr, Robert 4: 5Carya ovata 3: 9Caryophyllus florepleno 1 : 1cedar, Japanese 4: 13, 14Cephalotaxus mlsomana 1: 22-24Cercis canadensis 1: 8Chamaecypans 1 : G, 10- pisi f era 1: 6, 71. 6, 7Changbai Shan 3- 13, 16 18-19 20 2125-27Chatsworth Bakewell, Derbyshire 2:inside front and back coversChaw, Shu-Mlaw 1: 22-24, 25, 26Chen, Chih-Hui 1: 24-26chestnut 3: 3Chimonanthus 4: 21, 22China 3: 9, 10, 16,34,38,43"Chionanthus retusus. The ChmeseFnngetree," Peter Del Tredici &Jianhua LiChionanthus retusus 4: 17, 18vmgmicus 4: 17, 18"Chosenia: An Amazing Tree ofNorthe<strong>as</strong>t Asia," Inna Kadis 3.8-17chosema 3: 8-9, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 23, 24Chosema 3: 21, 22, 23, 24-arbutifoha 8, 9, 10 13Cmnamomom camphora 3: 36-sp. 2: front coverConcord, MA 2: 14Connor, Sheila, "The Nature ofE<strong>as</strong>t Asia: Botanical and CulturalImages from the Arnold ArboretumArchmes" 3: 34-44Corlett, Richard, "Dipterocarps: TreesThat Dominate the Asian Ram Forest"with Richard Pnmack 3: 2-7Cornales 1: 9cornel, Japanese 1: 9cornelian cherry, European 1: 9Cornus altermfoha 1: 91: 91: 9-m<strong>as</strong> 1 : 9-nuttallm 1: 91 : 9crabapples 1: 8cranberry 2: 19, 20cryptomena, Japanese 1: 8Cryptomena japonica 1: 8; 4: 13, 14--’Yoshmo’ 4. 14Cycads 1: 25Cyc<strong>as</strong> taitungensis 1: 25, 26, 27cypress, Leyland 4: 14false 1: 6, 7dammar [resm] 3: 4daphne, lilac 4: 284: 26Daphne x burkwoodm ’Carol Mackie’4: 274. 284: 26transatlantica ’Summer Ice’ 4:28Damdia mvolucrata 3: 37; 4: 8, 10- - var. mlmonmana 4: 8, 10De Hart, William 4: 4Del Tredici, Peter 3: 26; photos by 2:front cover; 4: front coverAll Odds: GrowmgFrankhnia m Boston" 4: 2-7chinensis: TheChinese Sweetshrub," with JianhuaLi 4: 21-22

- - -"Capturing---"Chionanthus- - -"Finding- - -"Herbarium-kaki-costulatus-E<strong>as</strong>t-flowering-western-European-e<strong>as</strong>tern--molhs- -Herbaria-Chinese-e<strong>as</strong>tern-mountain-northern-southern-western-European-- -European---pedunculosa- -"Chosema:30and CultivatingChosema" 3: 18-27retusus: TheChinese Fnngetree," with JianhuaLi 4: 17-18a Replacement forE<strong>as</strong>tern Hemlock: Research at theArnold Arboretum," with AliceKitayma 2: 33-39Specimens <strong>as</strong>a Novel Tool for Climate ChangeResearch," with Abraham J. Miller-Rushmg et al. 2: 26-32"Demystifying Daphnes," Bob Hyland4: 26-29Diospyros 3: 43: 38, 39Diploblechnum fr<strong>as</strong>em 1 : 24Dipterocarp 3: 2-6, 7Dipterocarpaceae 3: 3"Dipterocarps: Trees That Dominatethe Asian Ram Forest, " RichardCorlett and Richard Primack 3:2-7Dipterocarpus 3: 33: back coverDirr, Michael 4: 21, 26, 27-28disjunct species, E<strong>as</strong>t Asian-e<strong>as</strong>ternNorth America 1: 10dogwood, alternate-leaved 1: 9Asian giant 1: 91: 8- kousa 1: 9flowering 1: 9"Dove Tree: A Long Journey West,"Richard Schulhof 4: 9-10dove tree 4: 9, 10Dryobalanops aromatica 3 : 4E<strong>as</strong>t Tennessee State <strong>University</strong> 1: 2,7,8El Niiio-Southern Oscillation events3: 5, 6elm, American 2: 9, 11, 12, 13, 16-17- Enghsh 2: 1 1"Elms at Yale College," engraving byW. H. Bartlett 2: 8-9Ericaceae 2: 18Evelyn, John 1: 14, 16-17, 19Famchild, David 2: 3, 17Farges, Paul Guillaume 4: 9, 10Farrar, Reginald 3: 4 1Faxon, C. E., illustration by 4: 5Fernald, M. L. 1: 29"Finding a Replacement for E<strong>as</strong>ternHemlock: Research at the ArnoldArboretum," Peter Del Tredici andAlice Kitajima 2: 33-39Flora of the Lesser Antilles 2 : 6Formosa, see TaiwanFrankhma alatamaha 4: 2-6, 7fringetree, Chmese 4: 18genetic variation, mutational 1: 2Gondwana 3: 3Gore, Christopher 2: 10grape, Concord 2: 9, 15, 16, backcoverwme 2: 14- fox 2: 14Greeley, Horace 2: 15gum, E<strong>as</strong>t Asian 1: 9American black 1: 9Hamamehs x intermedia 1 : 4japonica 1 : 41: 4Hamilton, William 2: 10Hammond Woods, Newton, MA 1:28, 29<strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>University</strong> 1: 292: 3Hawthorne, Nathaniel 3: 28-30, 31,32-33Heather 2: 22Hedysarum 3: 14hemlock woolly adegid 2: 33hemlock, Carolina 2: 332: 33, 34-36, 39or Canadian 2: 33, 35, 362: 33Japanese 2: 33, 34Japanese 2’ 342: 33Henry, Augustine 4: 9, 10"Herbarium Specimens <strong>as</strong> a NovelTool for Climate Change Research, "Abraham J. Miller-Rushing, DamelPnmack, Richard B. Pnmack, CarolineImbres, and Peter Del Tredici2: 26-32herbarium specimens 2: 26-32Hers, Joseph 3: 35, photos by 3: 41hickory, shagbark 3: 9Hippoc<strong>as</strong>tanaceae 1: 5Historic Bartram’s Garden 4: 3holly, American 4: 124: 12evergreen American 1: 81: 8Hopea 3: 4ponga 3 : 5horse chestnut 1: 3, 4, 5--red 1:3"Horticulture and the Developmentof American Identity, " Philip J.Pauly 2: 8-17House of Seven Gables [NathanielHawthorne] 3: 32Hovey, Charles 2: 15Howard, Richard Alden 2: 2-7HWA (Adelges tsugae~ 2: 33-36Hwang, Shy-Yuan 1: 26hybridization 1: 3-6Hyland, Bob, "Demystifying Daphnes"4: 26-29Ilex aqmfolmm 1 : 8; 4: 12opaca 1: 8; 4: 124: 12, back cover"Ilex pedunculosa. The LongstalkHolly," Phyllis Andersen 4: 11-12illipe nuts 3: 6Imbres, Caroline, "Herbarium Specimens<strong>as</strong> a Novel Tool for ChmateChange Research," with Abraham J.Miller-Rushing et al. 2: 26-32"In Favor of Trees," John BnnckerhoffJackson 1: 13-19"In Memonam : Richard Alden Howard,1917-2003," Judith A Warnementand Carroll E. Wood, Jr. 2:2-7"In the Library: Hortus Nitidissimis,"Sheila Connor 1: 32Indonesia 3: 3International Umon for Conservationof Nature and Natural ResourcesRed List of Threatened Plants 1: 2 1Ishikawa, Shmgo 3: 22Jack, John George 3: 34, 35-36; 4: 6, 7;photos by 3: 36Jackson, John Brinckerhoff, "In Favorof Trees (1994)" 1: 13-19, drawmgsby 1: 15, 16Japan 3: 9, 22, 35Jefferson, Thom<strong>as</strong> 2: 10Johnson, Ethan W., photo by 4: backcoverJuniperus squamata var. meyen 3: 41Kadis, Irma 3: 21, 22An Amazing Tree ofNorthe<strong>as</strong>t Asia" 3: 8-17Kalmia latifoha ’Comet’ 4: insideback cover2014 2014 ’R<strong>as</strong>pberry Glow’ 4: 8kapur tree 3: 4Kitajima, Ahce, "Finding a Replacementfor E<strong>as</strong>tern Hemlock:Research at the Arnold Arboretum, "with Peter Del Tredici 2: 33-39Kolkmtzla amabihs ’Pink Cloud’ 4: 8Korea 3: 9, 18, 20, 35Lan Lee 3: 42Larix olgensis 3 : 27Lenox, MA 3: 32

--"Chionanthus--x-bristly--x-sylvatica-koraiensis-pumila-sylvestmformis-occidentahs-onentalls- -"Herbamum- -"The--Asian--pseudoacacia-x- -"Rhus31Levy, Foster, "Using Arboreta toTeach Biological Concepts" 1: 2-12with Tim McDowellLi, Jianhua, "Calycanthus chinensisThe Chinese Sweetshrub, " mthPeter Del Tredici 4. 21-22retusus. The ChineseFnngetree," with Peter DelTredici 4~ 17-18Lilmm regale 3: 37lrly, E<strong>as</strong>ter 3: 37lime tree 1. 17linden 17"Lmgonberry: Dainty Looks, SturdyDisposition, and T<strong>as</strong>ty Berries," LeeReich 2’ 18-25lingonberry 2 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23,24-25Lmociera 4’ 18Lmodendron chmense 1. 12- tuhpifera 1: 8, 12chmense 1: 12locust, black 1: 41: 4c<strong>as</strong>que rouge 1: 4longstalk holly 4: 11, 12, back coverLyon, John 4: 3Madsen, Karen, photo by 1 ~ front andback coversmagnolia, lrly-flowered 1: 3, 4- saucer 1: 4- Yulan 1. 3, 4Magnolia denudata 1: 2, 3, 4- hlnflora 1: 2, 3, 4soulangiana 1: 3---’Alexandrma’ 1: 2, 3, 4- stellata ’Centennial’ 4: 8- vmgmana ’Moonglow’ 4: insidefront coverMalay Peninsula 3: 3Malaysia 3: 3Manmng, Robert 3. 28maple, Norway 1: 28- red 1 ~ 8, 29, 30, 31- striped 1. 28Marble Faun [Nathaniel Hawthorne]3: 33Marshall, Humphry 4: 3McDowell, Marta, "Verdant Letters:Hawthorne and Horticulture" 3:28-33McDowell, Tim, "Usmg Arboreta toTeach Biological Concepts" 1: 2-12with Foster LevyMeehan, Joseph 4: 4Meehan, Thom<strong>as</strong> 4: 4, 5, 6, 7Meyer, Frank Nichol<strong>as</strong> 3: 34, 38-39;photos by 3: 38, 39Meyer, Paul 1: 22mezereum family 4: 26"Microbiota decussata A VersatileConifer," Nancy Rose 4’ 15-17Microbiota decussata 4: 15-16Nhquel, Fnednch Anton Wilhelm 4: 11Mongohan athletes 3 40morphological variarion 1: 6-8Mosses from an Old Manse [NathanielHawthorne] 3: 30mountain laurel 4. 8Mussaenda pubescens 1~ 24Nakal, Takenoshm 3: 10Nanjing Botanical Garden 3. 19; 4: 22Natural History Museum, London1: 32Nature of E<strong>as</strong>t Asia: Botanical andCultural Images from the ArnoldArboretum Archrves," Sheila Connor3: 34-44Nicholson, Rob, "A Good Day: Plant-Collectmg m Taiwan" 1 ~ 20-27, 25North American-Chinese Plant ExplorationConsortium (NACPEC)3: 18, 20Nyssa smensls 1: 91. 9oak 3: 3-4, 6Old Manse, Concord [MA] 3. 30Our Old House [Nathaniel Hawthorne]3 : 33Oxytropis 3: 14Panax gmseng 3: 20parent-hybnd combinations 1: 4Pauley, Philip J., "Horticulture andthe Development of AmericanIdentity" 2: 8-17Peabody,Sophia 3’29 30pear tree 2: 27Perry, Lily M. 2: 2persimmon sugar 3: 38Philippines 3’ 3Phomopsis 4: 16Phyllostictaaurea 4: 13phylogenetic biogeography 1: 2, 8-10Phytophthora cmnamom 4: 7Pierce, Franklin 3: 32Pmus x acenfoha 1: 43: 254: 153: 251: 41: 4Platycladus omentahs 3: 41, insideback coverplum yew, Wilson’s 1. 22, 23Polygonatum alte-lobata 1: 23poplar 3: 9, 13- Lombardy 2: 10Poncirus tnfol1ata 4’ inside backcoverPopulus 3: 21Primack, Damel, "Herbarium Specimens<strong>as</strong> a Novel Tool for ChmateChange Research," with Abraham J.Miller-Rushing et al. 2: 26-32Pnmack, Richard, "Dipterocarps:Trees That Dominate the AsianRam Forest" with Richard Corlett3.2-7Specimens <strong>as</strong> aNovel Tool for Climate ChangeResearch," with Abraham J. Miller-Rushing et al. 2: 26-32Sex Life of the Red Maple"1: 28-31Prince family nursery 2: 10, 14Pnnceton Nurseries 2: 16Prunus mantima 4: 19-- ‘Ocean View’ 4: 19coronans 1: 26PseudodrynanaPurdom, William 3: 34, 35, 39-41;photos by 3: 40Pusey, Nathan 2: 3Pyrus 2: 27Rafinesque, Constantine 4: 4rain forest, Amazoman 1. 143: 4redbud 1: 8redfire 4: 13Rehder, Alfred 3: 35Reich, Lee "Lingonberry DaintyLooks, Sturdy Disposition, andT<strong>as</strong>ty Berries" 2: 18-23, 24, 25Rhododendron dauncum 1: 11-mmus 1: 11-’P.J.M.’ 1: 11v<strong>as</strong>ey 2: 28Rhus aromatica 4’ 25"Rhus trilobata- Worthy Plant SeeksWorthy Name," Nancy Rose 4:23-26Rhus trilobata 4: 23-24, 25Robmia hispida 1: 41: 4margaretta 1: 4Rock, Joseph 3: 34, 35; photos by 3’42~13Rosa ’L’admirable’ 1 ~ inside backcoverRose, Nancy, "Microbiota decussata~A Versatile Comfer" 4: 15-17tmlobata: Worthy PlantSeeks Worthy Name" 4: 23-26Royal Botamc Gardens, Kew 1: 32; 3:37,39Rutgers Umversity 2: 16