Traditions Old and New - Worldwatch Institute

Traditions Old and New - Worldwatch Institute

Traditions Old and New - Worldwatch Institute

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

2 0 1 0STATE O F TH E WO R LDTransforming CulturesFrom Consumerism to SustainabilityTHEWORLDWATCHINSTITUTE

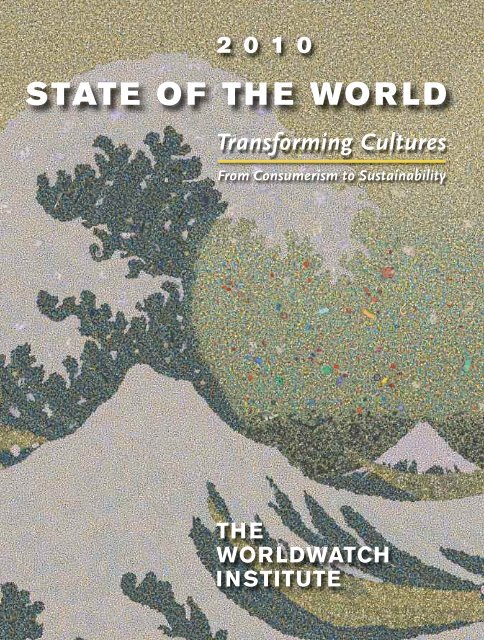

SCIENCE/ENVIRONMENT2 0 1 0STATE OF TH E WOR LDAdvance Praise for State of the World 2010:Transforming CulturesFrom Consumerism to Sustainability“If we continue to think of ourselves mostly asconsumers, it’s going to be very hard to bring ourenvironmental troubles under control. But it’s alsogoing to be very hard to live the rounded <strong>and</strong> joyfullives that could be ours. This is a subversive volumein all the best ways!”—Bill McKibben, author of Deep Economy <strong>and</strong>The End of Nature“<strong>Worldwatch</strong> has taken on an ambitious agenda inthis volume. No generation in history has achieved acultural transformation as sweeping as the one calledfor here…it is hard not to be impressed with thebook’s boldness.”—Muhammad Yunus, founder of the Grameen Bank“This year’s State of the World report is a culturalmindbomb exploding with devastating force. I hopeit wakes a few people up.”—Kalle Lasn, Editor of Adbusters magazineLike a tsunami, consumerism has engulfed humancultures <strong>and</strong> Earth’s ecosystems. Left unaddressed, werisk global disaster. But if we channel this wave, intentionallytransforming our cultures to center on sustainability,we will not only prevent catastrophe but may usher in anera of sustainability—one that allows all people to thrivewhile protecting, even restoring, Earth.In this year’s State of the World report, 50+ renownedresearchers <strong>and</strong> practitioners describe how we canharness the world’s leading institutions—education, themedia, business, governments, traditions, <strong>and</strong> socialmovements—to reorient cultures toward sustainability.full imageextreme close-upSeveral million pounds of plasticenter the world’s oceans every hour,portrayed on the cover by the 2.4million bits of plastic that make upGyre, Chris Jordan’s 8- by 11-footreincarnation of the famous 1820swoodblock print, The Great WaveOff Kanagawa, by the Japanese artistKatsushika Hokusai.For discussion questions,additional essays,video presentations,<strong>and</strong> event calendar, visitblogs.worldwatch.org/transformingcultures.Cover image: Gyre by Chris JordanCover design: Lyle RosbothamBW. W. N O R T O NN E W Y O R K • L O N D O Nwww.worldwatch.org

<strong>Traditions</strong><strong>Old</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>New</strong>Countless choices in human livesare reinforced, driven by, or stemfrom traditions, whether religioustraditions, rituals, cultural taboos,or what people learn from elders <strong>and</strong> theirfamilies. Taking advantage of these traditions<strong>and</strong> in some cases reorienting them to reinforcesustainable ways of life could help make humansocieties a restorative element of broader ecologicalsystems. As many cultures throughouthistory have found, traditional ways can oftenhelp enhance rather than undermine sustainablelife choices.This section considers several importanttraditions in people’s lives <strong>and</strong> in society. GaryGardner of <strong>Worldwatch</strong> suggests that religiousorganizations, which cultivate many of humanity’sdeepest held beliefs, could play a centralrole in cultivating sustainability <strong>and</strong> deterringconsumerism. Considering the financialresources of these bodies, their moral authority,<strong>and</strong> the fact that 86 percent of the peoplein the world say they belong to an organizedreligion, getting religions involved in spreadingcultures of sustainability will unquestionablybe essential. 1Rituals <strong>and</strong> taboos play an important role inhuman lives <strong>and</strong> help reinforce norms, behaviors,<strong>and</strong> relationships. So Gary Gardner alsolooks at rites of passage, holidays, political rit-uals, <strong>and</strong> even daily actions that can be redirectedfrom moments that stimulate consumptionto those that reconnect people withthe planet <strong>and</strong> remind them of their dependenceon Earth for continued well-being.<strong>Traditions</strong> shape not just day-to-day activitiesbut major life choices, such as how manychildren to have. Tapping into traditions—families’ influence, religious teachings, <strong>and</strong>social pressures—to shift family size norms tomore sustainable levels will be essential inglobal efforts to stabilize population growth.Robert Engelman of <strong>Worldwatch</strong> points outthat the prerequisite of this will be to ensurethat women have the ability to control theirreproductive choices <strong>and</strong> that their families<strong>and</strong> governments let them make these choicesin ways that respect their decisions.Another important <strong>and</strong> unfortunatelydiminishing force for sustainability is the wisdomof elders. Through their long lives <strong>and</strong>breadth of experience, elders traditionally helda place of respect in communities <strong>and</strong> servedas knowledge keepers, religious leaders, <strong>and</strong>shapers of community norms. These roles,however, have weakened as consumerism <strong>and</strong>its subsequent celebration of youth <strong>and</strong> rejectionof tradition have spread across the planet.Recognizing the power of elders <strong>and</strong> takingadvantage of all they know, as Judi Aubel of theBLOGS.WORLDWATCH.ORG/TRANSFORMINGCULTURES 21

<strong>Traditions</strong> <strong>Old</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>New</strong> STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Gr<strong>and</strong>mother Project describes, can be animportant tool in cultivating traditions thatreinforce sustainable practices.Finally, one long-lived tradition that hasbeen dramatically altered in the past severalgenerations is farming. Albert Bates of TheFarm <strong>and</strong> Toby Hemenway of Pacific Universitydescribe how sustainable societies willdepend on sustainable agricultural practices—systems in which farming methods no longerdeplete soils <strong>and</strong> pollute the planet but actuallyhelp to replenish soils <strong>and</strong> heal scarredl<strong>and</strong>scapes while providing healthy food <strong>and</strong>livelihoods.Several Boxes in these articles also discussimportant traditions, including the need forethical systems to internalize humanity’s dependenceon Earth’s systems, the value of rekindlingan underst<strong>and</strong>ing of geologic-scale time,<strong>and</strong> the importance of reorienting dietarynorms to encourage healthy <strong>and</strong> sustainablefood choices.These are just some of the many traditionsthat need to be critically examined <strong>and</strong> recalibratedto reflect a changing reality—one inwhich 6.8 billion people live on Earth, another2.3 billion are projected to join by 2050, <strong>and</strong>the ecological systems on which humanitydepends are under serious strain. Cultures in thepast have also faced ecological crises. Some, likethe Rapanui of Easter Isl<strong>and</strong>, failed to altertheir traditions. The Rapanui continued, forexample, to dedicate too many resources totheir ritual building of Moai statues—untiltheir society buckled under the strain <strong>and</strong> EasterIsl<strong>and</strong>’s population collapsed. Others have beenmore like the Tikopians, who live on a smallisl<strong>and</strong> in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. Whenthey saw the dangers they faced as ecologicalsystems became strained, they made dramaticchanges in social roles, family planning strategies,<strong>and</strong> even their diet. Recognizing theresource-intensive nature of raising pigs, forinstance, they stopped raising them altogether.As a result, Tikopia’s population stayed stable<strong>and</strong> continues to thrive today. 2—Erik Assadourian22 WWW.WORLDWATCH.ORG

Engaging Religions to Shape Worldviews STATE OF THE WORLD 2010debt-reduction initiative, the nuclear-freezeinitiative in the United States in the 1980s—all these featured significant input <strong>and</strong> supportfrom religious people <strong>and</strong> institutions. Andindigenous peoples, drawing on an intimate<strong>and</strong> reciprocal relationship with nature, helppeople of all cultures to reconnect, often in aspiritual way, with the natural world that supportsall human activity. 4The Greening of ReligionOver the past two decades, the indicators ofengagement on environmental issues by religions<strong>and</strong> spiritual traditions have grownmarkedly. And opinion polls reveal increasedinterest in such developments. The World ValuesSurvey, a poll of people in dozens of countriesundertaken five times since the early 1980s,reports that some 62 percent of people worldwidefeel it is appropriate for religious leadersto speak up about environmental issues, suggestingbroad latitude for religious activism. 5More specific data from the United Statessuggest that faith communities are potentiallyan influential gateway to discussions aboutenvironmental protection. A 2009 poll foundthat 72 percent of Americans say that religiousbeliefs play at least a “somewhat important” rolein their thinking about the stewardship of theenvironment <strong>and</strong> climate change. 6Another marker of the cultural influenceof religious <strong>and</strong> spiritual traditions is the emergenceof major reference works on religion<strong>and</strong> sustainability, giving the topic added legitimacy.Over the past decade, an encyclopedia,two journals, <strong>and</strong> a major research project onthe environmental dimensions of 10 worldreligions have documented the growth of religionsin the environmental field. (See Table 4.)Dozens of universities now offer courses on thereligion/sustainability nexus, <strong>and</strong> the 2009Parliament of the World’s Religions had majorpanels on the topic. 7Table 4. Reference Works on Religion <strong>and</strong> NatureInitiative Date Appeared Description“Religions of the World <strong>and</strong>Ecology” ProjectEncyclopedia of Religion<strong>and</strong> NatureThe Spirit of SustainabilityGreen BibleWorldviews: Global Religions,Culture, <strong>and</strong> Ecology <strong>and</strong>Journal for the Study ofReligion, Nature, <strong>and</strong> CultureSource: See endnote 7.1995–20052005200920081995, 1996A Harvard-based research project that produced 10volumes, each devoted to the relationship between amajor world religion <strong>and</strong> the environmentA 1,000-entry reference work that explores relationshipsamong humans, the environment, <strong>and</strong>religious dimensions of lifeOne volume in the 10-volume Berkshire Encyclopediaof Sustainability, examining the values dimension ofsustainability through the lens of religionsThe <strong>New</strong> Revised St<strong>and</strong>ard Version, with environmentallyoriented verses in green <strong>and</strong> with essaysfrom religious leaders about environmental topics;printed on recycled paper using soy-based inkJournals devoted to the linkages among the spheresof nature, spirit, <strong>and</strong> culture24 WWW.WORLDWATCH.ORG

STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Engaging Religions to Shape WorldviewsReligious activism on behalf of the environmentis now common—in some cases, tothe point of becoming widespread, organized,<strong>and</strong> institutionalized. Three examples fromthe realms of water conservation, forest conservation,<strong>and</strong> energy <strong>and</strong> climate illustratethis broad-based impact.First, His All Holiness, Patriarch Bartholomew,ecumenical leader of more than 300 millionOrthodox Christians, founded Religion,Science <strong>and</strong> the Environment (RSE) in 1995to advance religious <strong>and</strong> scientific dialoguearound the environmental problems of majorrivers <strong>and</strong> seas. RSE has organized shipboardsymposia for scientists, religious leaders, scholars,journalists, <strong>and</strong> policymakers to study theproblems of the Aegean, Black, Adriatic, <strong>and</strong>Baltic Seas; the Danube, Amazon, <strong>and</strong> MississippiRivers; <strong>and</strong> the Arctic Ocean. 8In addition to raising awareness about theproblems of specific waterways, the symposiahave generated initiatives for education, cooperation,<strong>and</strong> network-building among localcommunities <strong>and</strong> policymakers. Sponsors haveincluded the Prince of Wales; attendees includepolicymakers from the United Nations <strong>and</strong>World Bank; <strong>and</strong> collaborators have includedPope John Paul II, who signed a joint declarationwith Patriarch Bartholomew on humanity’sneed to protect the planet. 9Second, “ecology monks”—Buddhistadvocates for the environment in Thail<strong>and</strong>—have taken st<strong>and</strong>s against deforestation,shrimp farming, <strong>and</strong> the cultivation of cashcrops. In several cases they have used a Buddhistordination ritual to “ordain” a tree in anendangered forest, giving it sacred status inthe eyes of villagers <strong>and</strong> spawning a forestconservation effort. One monk involved intree ordinations has created a nongovernmentalorganization to leverage the monks’efforts by coordinating environmental activitiesof local village groups, government agencies,<strong>and</strong> other interested organizations. 10Third, Interfaith Power <strong>and</strong> Light (IPL), aninitiative of the San Francisco–based RegenerationProject, helps U.S. faith communitiesgreen their buildings, conserve energy, educateabout energy <strong>and</strong> climate, <strong>and</strong> advocate for climate<strong>and</strong> energy policies at the state <strong>and</strong> federallevel. Led by Reverend Sally Bingham, anEpiscopal priest, IPL is now active in 29 states<strong>and</strong> works with 10,000 congregations. It hasdeveloped a range of innovative programs tohelp faith communities green their work <strong>and</strong>worship, including Cool Congregations, whichfeatures an online carbon calculator <strong>and</strong> whichin 2008 awarded $5,000 prizes to both thecongregation with the lowest emissions percongregant <strong>and</strong> the congregation that reducedemissions by the greatest amount. 11These <strong>and</strong> other institutionalized initiatives,along with the thous<strong>and</strong>s of individual grassrootsreligious projects at congregations worldwide—fromBahá’í environmental <strong>and</strong> solartechnology education among rural women inIndia to Appalachian faith groups’ efforts tostop mountaintop mining <strong>and</strong> the varied environmentalefforts of “Green nuns”—suggestthat religious <strong>and</strong> spiritual traditions are readypartners, <strong>and</strong> often leaders, in the effort tobuild sustainable cultures. 12Silence on False Gods?In contrast to their active involvement in environmentalmatters, the world’s religious traditionsseem to hold a paradoxical positionon consumerism: while they are well equippedto address the issue, <strong>and</strong> their help is sorelyneeded, religious involvement in consumerismis largely limited to occasional statements fromreligious leaders.Religious warnings about excess <strong>and</strong> aboutexcessive attachment to the material world arelegion <strong>and</strong> date back millennia. (See Table 5.)Wealth <strong>and</strong> possessiveness—key features of aconsumer society—have long been linked byreligious traditions to greed, corruption, selfishness,<strong>and</strong> other character flaws. Moreover,BLOGS.WORLDWATCH.ORG/TRANSFORMINGCULTURES 25

Engaging Religions to Shape Worldviews STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Table 5. Selected Religious Perspectives on ConsumptionFaithPerspectiveBahá’í Faith “In all matters moderation is desirable. If a thing is carried to excess, it will prove asource of evil.” (Bahá’u’lláh, Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh)Buddhism “Whoever in this world overcomes his selfish cravings, his sorrow fall away fromhim, like drops of water from a lotus flower.” (Dhammapada, 336)Christianity “No one can be the slave of two masters….You cannot be the slave both of God <strong>and</strong>money.” (Matthew, 6:24)Confucianism “Excess <strong>and</strong> deficiency are equally at fault.” (Confucius, XI.15)Hinduism “That person who lives completely free from desires, without longing…attainspeace.” (Bhagavad Gita, II.71)Islam “Eat <strong>and</strong> drink, but waste not by excess: He loves not the excessive.” (Qur’an, 7.31)Judaism “Give me neither poverty nor riches.” (Proverbs, 30:8)Taoism “He who knows he has enough is rich.” (Tao Te Ching)Source: See endnote 13.faith groups have spiritual <strong>and</strong> moral toolsthat can address the spiritual roots of consumerism—includingmoral suasion, sacredwritings, ritual, <strong>and</strong> liturgical practices—inaddition to the environmental arguments usedby secular groups. And local congregations,temples, parishes, <strong>and</strong> ashrams are often tightknitcommunities that are potential models<strong>and</strong> support groups for members interested inchanging their consumption patterns. 13Moreover, of the three drivers of environmentalimpact—population, affluence, <strong>and</strong>technology—affluence, a proxy for consumption,is the arena in which secular institutionshave been least successful in promotingrestraint. Personal consumption continuesupward even in wealthy countries, <strong>and</strong> consumerlifestyles are spreading rapidly to newlyprospering nations. Few institutions exist inmost societies to promote simpler living, <strong>and</strong>those that do have little influence. So sustainabilityadvocates have looked to religions forhelp, such as in the l<strong>and</strong>mark 1990 statement“Preserving <strong>and</strong> Cherishing the Earth: AnAppeal for Joint Commitment in Science <strong>and</strong>Religion” led by Carl Sagan <strong>and</strong> signed by 32Nobel Laureates. 14Despite the logic for engagement, religiousintervention on this issue is sporadic <strong>and</strong>rhetorical rather than sustained <strong>and</strong> programmatic.It is difficult to find religious initiativesthat promote simpler living or that help congregantschallenge the consumerist orientationof most modern economies. (Indeed, anextreme counterexample, the “gospel of prosperity,”encourages Christians to see greatwealth <strong>and</strong> consumption as signs of God’sfavor.) Simplicity <strong>and</strong> anti-consumerism arelargely limited to teachings that get little sustainedattention, such as Pope Benedict’s July2009 encyclical, Charity in Truth, a strongstatement on the inequities engendered bycapitalism <strong>and</strong> the harm inflicted on both people<strong>and</strong> the planet. Or simplicity is practiced bythose who have taken religious vows, whosecommitment to this lifestyle—while oftenrespected by other people—is rarely put forthas a model for followers. 15Advocating a mindful approach to consumptioncould well alienate some of the faith-26 WWW.WORLDWATCH.ORG

STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Engaging Religions to Shape Worldviewsful in many traditions. But it would also addressdirectly one of the greatest modern threats toreligions <strong>and</strong> to spiritual health: the insidiousmessage that the purpose of human life is toconsume <strong>and</strong> that consumption is the path tohappiness. Tackling these heresies could nudgemany faiths back to their spiritual <strong>and</strong> scripturalroots—their true source of power <strong>and</strong> legitimacy—<strong>and</strong>arguably could attract more followersover the long run.Contributions to a Cultureof SustainabilityMost religious <strong>and</strong> spiritual traditions have agreat deal to offer in creating cultures of sustainability.Educate about the environment. As religioustraditions embrace the importance ofthe natural environment, it makes sense toinclude ecological instruction in religious education—justas many Sunday Schools include asocial justice dimension in their curricula.Teaching nature as “the book of Creation,” <strong>and</strong>environmental degradation as a sin, for example—positionsadopted by various denominationsin recent years—is key to moving peoplebeyond an instrumentalist underst<strong>and</strong>ing ofthe natural world. 16Educate about consumption. In an increasingly“full world” in which human numbers<strong>and</strong> appetites press against natural limits, introducingan ethic of limited consumption is anurgent task. Religions can make a differencehere: University of Vermont scholar StephanieKaza reports, for example, that some 43 percentof Buddhists surveyed at Buddhist retreat centerswere vegetarians, compared with 3 percentof Americans overall. Such ethical influenceover consumption, extended to all wisdom traditions<strong>and</strong> over multiple realms in addition tofood, could be pivotal in creating cultures of sustainability.(See Box 3.) 17Educate about investments. Many religiousinstitutions avoid investments in weapons, cigarettes,or alcohol. Why not also steer fundstoward sustainability initiatives, such as solarpower <strong>and</strong> microfinance (the via positiva, inthe words of the Archbishop of Canterbury)?This is what the International Interfaith InvestmentGroup seeks to do with institutional religiousinvestments. In addition, why not stressthe need for personal portfolios (not just institutionalones) to be guided ethically as well? Inthe United States alone the value of investmentportfolios under professional management wasmore than $24 trillion in 2007, only 11 percentof which was socially responsible investment. 18Express the sacredness of the natural worldin liturgies <strong>and</strong> rituals. The most importantassets of a faith tradition are arguably the intangibleones. Rituals, customs, <strong>and</strong> liturgicalexpressions speak to the heart in a profound waythat cognitive knowledge cannot. Considerthe power of the Taoist yin <strong>and</strong> yang framingof climate change, or of Christian “carbonfasts” at Lent, or of the Buddhist, Hindu, <strong>and</strong>Jain underst<strong>and</strong>ing of ahimsa (non-harming) asa rationale for vegetarianism. How else mightreligious <strong>and</strong> spiritual traditions express sustainabilityconcerns ritualistically <strong>and</strong> liturgically?Reclaim forgotten assets. Religious traditionshave a long list of little-emphasized economicteachings that could be helpful forbuilding sustainable economies. These includeprohibitions against the overuse of farml<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong>pursuit of wealth as an end in itself, advocacyof broad risk-sharing, critiques of consumption,<strong>and</strong> economies designed to serve the commongood. (See Table 6.) Much of this wisdomwould be especially helpful now, as economiesare being restructured <strong>and</strong> as people seem opento new rules of economic action <strong>and</strong> a newunderst<strong>and</strong>ing of ecological economics. 19Coming HomeOften painted as conservative <strong>and</strong> unchanginginstitutions, many religions are in fact rapidlyembracing the modern cause of environmen-BLOGS.WORLDWATCH.ORG/TRANSFORMINGCULTURES 27

STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Engaging Religions to Shape WorldviewsTable 6. Economic Precepts of Selected Religious <strong>and</strong> Spiritual <strong>Traditions</strong>EconomicTeaching orPrincipleBuddhisteconomicsCatholiceconomicteachingsIndigenouseconomicpracticesIslamicfinanceSabbatheconomicsDescriptionWhereas market economies aim to produce the highest levels of production <strong>and</strong>consumption, “Buddhist economics” as espoused by E. F. Schumacher focuses on aspiritual goal: to achieve enlightenment. This requires freedom from desire, a core driverof consumerist economies but for Buddhists the source of all suffering. From thisperspective, consumption for its own sake is irrational. In fact, the rational personaims to achieve the highest level of well-being with the least consumption. In this view,collecting material goods, generating mountains of refuse, <strong>and</strong> designing goods towear out—all characteristics of a consumer economy—are absurd inefficiencies.At least a half-dozen papal encyclicals <strong>and</strong> countless bishops’ documents argue thateconomies should be designed to serve the common good <strong>and</strong> are critical of unrestrainedcapitalism that emphasizes profit at any cost. The July 2009 encyclical Charity in Truthis a good recent example.Because indigenous peoples’ interactions with nature are relational rather thaninstrumental, resource use is something done with the world rather than to the world.So indigenous economic activities are typically characterized by interdependence,reciprocity, <strong>and</strong> responsibility. For example, the Tlingit people of southern Alaska, beforeharvesting the bark of cedar trees (a key economic resource), make a ritual apology tothe spirits of the trees <strong>and</strong> promise to use only as much as needed. This approachcreates a mindful <strong>and</strong> minimalist ethic of resource consumption.Islamic finance is guided by rules designed to promote the social good. Because moneyis intrinsically unproductive, Islamic finance deems it ethically wrong to earn moneyfrom money (that is, to charge interest), which places greater economic emphasis onthe “real” economy of goods <strong>and</strong> services. Islamic finance reduces investment risk—<strong>and</strong> promotes financial stability—by pooling risk broadly <strong>and</strong> sharing rewards broadly.And it prohibits investment in casinos, pornography, <strong>and</strong> weapons of mass destruction.The biblical books of Deuteronomy <strong>and</strong> Exodus declare that every seventh (“Sabbath”)year, debts are to be forgiven, prisoners set free, <strong>and</strong> cropl<strong>and</strong> fallowed as a way to givea fresh start to the poor <strong>and</strong> the imprisoned <strong>and</strong> to depleted l<strong>and</strong>. Underlying theseeconomic, social, <strong>and</strong> environmental obligations are three principles: extremes of consumptionshould be avoided; surplus wealth should circulate, not concentrate; <strong>and</strong>believers should rest regularly <strong>and</strong> thank God for their blessings.Source: See endnote 19.tal protection. Yet consumerism—the oppositeside of the environmental coin, <strong>and</strong> traditionallyan area of religious strength—hasreceived relatively little attention thus far.Ironically, the greatest contribution the world’sreligions could make to the sustainability challengemay be to take seriously their ownancient wisdom on materialism. Their specialgift—the millennia-old paradoxical insightthat happiness is found in self-emptying, thatsatisfaction is found more in relationships thanin things, <strong>and</strong> that simplicity can lead to afuller life—is urgently needed today. Combinedwith the newfound passion of manyreligions for healing the environment, thisancient wisdom could help create new <strong>and</strong>sustainable civilizations.BLOGS.WORLDWATCH.ORG/TRANSFORMINGCULTURES 29

Ritual <strong>and</strong> Taboo asEcological GuardiansGary Gardner“Keeping kosher,” the ancient Jewish practiceof observing dietary laws, has great practical <strong>and</strong>symbolic value for many Jews. It promotesawareness of the abundant generosity of thedivine <strong>and</strong> prescribes a particular, respectfulrelationship with the fruits of God’s creation.Some observant Jews are now working to establishan “eco-kosher” tradition: right eating <strong>and</strong>right consumption to preserve environmentalhealth. Eco-kosher would infuse Jewish comm<strong>and</strong>mentswith modern meaning: Bal Tashchit,the injunction not to waste, might applyto excessive or non-recycled food packaging;Tzaar Baalei Chayyim, the comm<strong>and</strong>ment toavoid cruelty to animals, could speak to confinedlivestock operations; <strong>and</strong> Shmirat Haguf,the requirement that people take care of theirbodies, might prohibit foods that have beensprayed with pesticides. The environmentalframing of ancient kosher rituals <strong>and</strong> prohibitionsadds a powerful transcendent dimensionto environmental protection. 1Transforming cultures of consumerism intocultures of sustainability will require a broad setof tools, including, perhaps surprisingly, ritual<strong>and</strong> taboo. Rituals—defined here as formalacts, repeated regularly, that have deep meaningfor a community of people—help peopleto internalize <strong>and</strong> communicate deep-seatedvalues. And taboos—the cultural prohibitionof specific acts <strong>and</strong> products—might also helpto proscribe human activities in an environmentallydegraded world. 2Although commonly associated with spiritualpractices, rituals <strong>and</strong> taboos are as mucha secular as a religious phenomenon. A primeminister or president singing the nationalanthem, h<strong>and</strong> over heart, is engaged in a powerfulritualistic behavior that speaks deeply tocompatriots, for example. And disrespecting aflag or other national symbol is a commontaboo in many countries.Whether secular or religious, political or personal,rituals <strong>and</strong> taboos in a consumer cultureoften reinforce that culture <strong>and</strong> the environmentalproblems it brings. But increasingly thesepractices are being used to bring mindfulness tomodern habits of consumption, as the exampleof eco-kosher suggests. Ritual <strong>and</strong> taboo couldbecome powerful, if largely intangible, tools forbuilding cultures of sustainability.The Power of RitualRitual communication has long had an importantrole in protecting the natural environ-Gary Gardner is a senior researcher at the <strong>Worldwatch</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> who focuses on sustainable economies.30 WWW.WORLDWATCH.ORG

STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Ritual <strong>and</strong> Taboo as Ecological Guardiansment. Cultural ecologist E. N. Andersonobserves that in indigenous societies that havemanaged resources well for sustained periods,the credit often goes to “religious or ritualrepresentation of resource management.” Thisis in part because of the nature of ritual. AnthropologistRoy Rappaport <strong>and</strong> others suggestthat ritual is a more powerful form of communicationthan even language <strong>and</strong> that thisadvantage is useful for environmental protection,especially in cultures like indigenous onesthat are deeply embedded in the natural environment.Rituals express deep, culturallyaccepted truths in ways that language, which iseasily manipulated <strong>and</strong> often used in service offalsehoods, cannot. 3As an example of the power of ritual,Swedish historian of religions Anne-ChristineHornborg cites the effort by the Mi’kmaqpeople on Cape Breton Isl<strong>and</strong>, Nova Scotia, tostop development of a quarry proposed for aMi’kmaq sacred mountain in the early 1990s.While a range of groups, including environmentalists,stepped up to oppose the project,most of them used data, analysis, <strong>and</strong> rhetoricto highlight environmental <strong>and</strong> other impactsof the quarry. The quarry company easily parriedthese arguments with its own statistics<strong>and</strong> analyses. 4The Mi’kmaq, however, took a differentapproach, relying on ritual, including a sweatlodge, drumming, <strong>and</strong> pow-wows, as their“argument,” <strong>and</strong> documenting that the mountainwas a traditional Mi’kmaq sacred site. Thecompany had a difficult time countering theMi’kmaq rituals because, as Hornborg explainsit, rituals are “immune to bureaucratic control.”Or, as another scholar eloquently summarizedit, “You cannot argue with a song.”In the end, the company dropped its bid.While many reasons are given by different partiesfor the company’s decision, the Mi’kmaqrituals, says Hornborg, were a powerful <strong>and</strong>possibly decisive influence. 5Rappaport <strong>and</strong> other scholars cite manyexamples of cultures that use ritual <strong>and</strong> taboo forenvironmental protection. The Tsembaga peopleof <strong>New</strong> Guinea, for instance, use elaboratepig festivals that include ritual slaughters <strong>and</strong> pigeatingrituals to achieve ecological balance. Ritualpig slaughtering, which occurs when pigpopulations have grown too large, lowers ecologicalpressures, redistributes l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> pigsamong people, <strong>and</strong> ensures that the neediest arethe first to receive limited supplies of pork. 6Ethnographers tell similar stories. In Ghana,the traditional beliefs <strong>and</strong> taboos of the Ningopeople protect turtles, which are viewed asgods, <strong>and</strong> mollusks, whose habitat is found ina sacred lagoon. Harvesting each species is forbidden,but no such taboos exist in neighboringGhanaian coastal cultures. As a result, some80 percent of turtle nesting areas along theGhanaian coast are found in Ningo protectedareas, <strong>and</strong> mollusks are up to seven times moreprevalent in areas protected by taboo than inneighboring areas. 7These examples are not isolated cases ofconservation. A 1997 analysis of species-specifictaboos found strong overlap betweentaboos <strong>and</strong> official assessments of speciesendangerment: some 62 percent of reptiles<strong>and</strong> 44 percent of mammals protected byindigenous rituals <strong>and</strong> taboos were also identifiedas threatened in the World ConservationUnion’s Red List of endangered species, suggestingthat indigenous peoples are skilledmonitors of species endangerment. And as theexamples just cited suggest, indigenous peopleshave also developed strategies for protectingspecies, perhaps through co-evolutionaryprocesses whereby human practices, includingtaboos, change in step with threats to thewell-being of various species. 8Rituals of ConsumerismRituals in consumer cultures may be powerfulcarriers of meaning, just as they are in indigenouscultures, but many also help to spreadBLOGS.WORLDWATCH.ORG/TRANSFORMINGCULTURES 31

Ritual <strong>and</strong> Taboo as Ecological Guardians STATE OF THE WORLD 2010McKay SavageLess toxic than most: In Chennai, India, a statue of Ganesh is madealmost entirely of fruits <strong>and</strong> vegetables.consumerist values. Consider modern rites ofpassage—weddings, funerals, bar/bat mitzvahs,<strong>and</strong> quinceañeras, for example—which inmany cases have become events marked byheavy consumption, compared with their oldfashionedpredecessors.The Wedding Report, a market researchfirm, says that weddings are a $60-billionindustry in the United States, with the averagecelebration in 2008 costing nearly $22,000.The expenditures cover a range of goods <strong>and</strong>services—invitations, gifts, meals, paper goods,flowers, rings, guest travel, <strong>and</strong> attire, to namea few—each with its own ecological footprint.Guests who fly in for the event, for instance,have an extraordinary carbon footprint. Thereception can have a large impact as well, especiallyif meat is served <strong>and</strong> if the food was notgrown locally. And the two new gold ringsthat the celebrants exchange required theremoval of tons of ore <strong>and</strong> earth, along withtoxic flows of chemicals to extract the gold. 9Modern funerals, too, cancarry an unnecessary ecologicalfootprint. Today funerals inwestern countries typicallyinvolve an elaborate casket,embalming, flowers, <strong>and</strong> acemetery plot with a concreteliner <strong>and</strong> marble headstone. Thematerials requirements forfunerals in the United States—some 1.5 million tons of concrete<strong>and</strong> 14,000 tons of steelfor funeral vaults, <strong>and</strong> 90,000tons of steel <strong>and</strong> nearly 3,000tons of copper <strong>and</strong> bronze forcaskets—is not huge as a shareof all concrete <strong>and</strong> metals usedin the country. But many of thefeatures of modern funerals arerecent innovations that areentirely unnecessary. After all,just a few generations ago, evenin industrial countries, the bodyof the deceased was prepared at home—wrapped in a shroud or placed in a simplewooden box. And in some cultures today theritual has scarcely any environmental impact:in the Tibetan “sky burial” the body of thedeceased, believed to be an empty vessel nowdevoid of a soul, is cut up <strong>and</strong> left for vulturesto feed on. However unpalatable to the westernmind, this ritual is environmentally restorative<strong>and</strong> does not spread consumerist values. 10Traditional holidays <strong>and</strong> feasts can be occasionsof heavy consumption <strong>and</strong> environmentalimpact. Christmas is a commonly citedexample, but other holidays make the pointas well. In India the festival of GaneshChathauri—which honors Ganesh, the godthat is half-elephant, half-man—typicallyinvolves the use of thous<strong>and</strong>s of large idolspainted in bright colors. At the festival’s end,these are immersed in rivers, lakes, <strong>and</strong> the sea,where the paints <strong>and</strong> other materials contaminatethe water. In the Bangalore area,32 WWW.WORLDWATCH.ORG

STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Ritual <strong>and</strong> Taboo as Ecological Guardianswhere an estimated 25,000–30,000 idols havebeen used in festivals in recent years, a test offour lakes found increased acidification, adoubling of dissolved solids, a tenfold increasein iron content, <strong>and</strong> a 200–300 percentincrease in copper in sediments. Manyobservers have called for alternative ways ofmarking Ganesh Chathauri—using biodegradablematerials for the idols, for example, or rituallysprinkling them in lieu of immersingthem in water bodies. 11Shopping itself has become a major ritualaround some holidays. In the United States,“Black Friday”—the day after Thanksgiving<strong>and</strong> a non-working day for most people—is ashopping extravaganza that marks the openingof the Christmas shopping season. A Web sitepromoting Black Friday deals is up monthsbefore the day arrives, <strong>and</strong> people line up outsideof malls <strong>and</strong> major stores, many of whichopen their doors before dawn. Black Friday hasbecome a popular shopping ritual in itself,with extensive media coverage. And it nowst<strong>and</strong>s as a symbol of excess, with some storesexperiencing violence, injuries, <strong>and</strong> even deathas shoppers rush the doors at opening time. 12Rituals <strong>and</strong> Taboos forSustainable ConsumptionModern rituals for sustainability can be developedout of virtually any dimension of thehuman experience. “Green funerals” areincreasingly common, in which families canchoose an environmentally benign end-of-liferitual that foregoes embalming, uses a simplewooden box or even a shroud for the deceased,avoids use of a burial vault, <strong>and</strong> in some casesmarks the grave with shrubs, trees, or a stonenative to the area, leaving the burial field or forestin an entirely natural state. According to theCentre for Green Burial in the United Kingdom,green burials are now available in Australia,Canada, Europe, <strong>and</strong> the United States. 13Holidays are another opportunity to greencommon rituals. <strong>New</strong> Year’s Day, for instance,is celebrated in many cultures, whether on theGregorian, Chinese, Hebrew, Islamic, orother calendar. For many people, entering anew year is foremost about marking the passageof time. And in this era of civilizationaltransition—an epoch akin to the shift fromhunter-gatherers to farmers, or from agrarianto industrial societies—the new year may bea time to reflect in a long-term sense. (SeeBox 4.) 14But <strong>New</strong> Year’s Day is also a time to set anew direction. In Peru <strong>and</strong> other Latin Americancountries, for example, people make effigiesto represent all that was bad in the yearpast, then burn them at midnight. In Japan,Bonenkai or “forget-the-year parties” are heldin December to prepare for the new year bybidding farewell to the concerns of the pastyear. Would annual cleansing rituals be anappropriate time to review personal <strong>and</strong> communityfailures to respect <strong>and</strong> preserve thenatural world—<strong>and</strong> to vow to do better in thenew year?Earth Day is a relatively new calendar-basedritual that was established specifically to promoteenvironmental awareness <strong>and</strong> care forthe planet. Since its founding in 1970, EarthDay has become a global celebration, withmore than a billion people participating,according to the Earth Day Network. Thegroup claims to work with more than 15,000organizations in 174 countries to create “theonly event celebrated simultaneously aroundthe globe by people of all backgrounds, faiths<strong>and</strong> nationalities.” Such a global platformcould become a powerful place from which tolead the entire human family in ritual appreciationof the planet. 15Fasting, a ritual discipline practiced in manyreligions, is being used by many people toraise consciousness about personal practicesthat might be used for a more sustainableworld. In 2009 the bishops of Liverpool <strong>and</strong>London called on Christians to undertake aBLOGS.WORLDWATCH.ORG/TRANSFORMINGCULTURES 33

Ritual <strong>and</strong> Taboo as Ecological Guardians STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Box 4. Deepening Perceptions of TimeThe Long Now Foundation was founded in01996 to help change long-term thinking frombeing difficult <strong>and</strong> rare to common <strong>and</strong> easy.(The foundation uses five-digit dates; the extrazero is to solve the deca-millennium bug thatwill come into effect in about 8,000 years.) Itstarted with an idea from Danny Hillis, whopioneered the massive parallel logic of today’sfastest super-computers. Hillis wanted tobuild an all-mechanical 10,000-year clock asan icon to long-term thinking.Hillis was inspired by a story relayed to himby Whole Earth Catalog editor Stewart Br<strong>and</strong>:“I think of the oak beams in the ceiling of CollegeHall at <strong>New</strong> College, Oxford. Last century,when the beams needed replacing, carpentersused oak trees that had been planted in 1386when the dining hall was first built. The 14thcenturybuilder had planted the trees in anticipationof the time, hundreds of years in thefuture, when the beams would need replacing.”Over the last 14 years, several prototypes<strong>and</strong> material studies have been completed ofthe clock, <strong>and</strong> the monument-scale version isnow being built. It will be located at one of thefoundation’s high desert sites <strong>and</strong> stretch outthrough several hundred feet of undergroundcaverns. Hillis hopes that a clock “that ticksonce a year, bongs once a century, <strong>and</strong> thecuckoo comes out once a millennium” willhelp reframe the way people look at the future.Since that first inspiration, the foundation hasembarked on several projects to promotelong-term thinking.Long Bets is an online wagering site whereanyone can make bets <strong>and</strong> predictions ofsocial <strong>and</strong> scientific consequence. All the proceedsplus half the interest go to the charityof the winner’s choice; the rest of the interestgoes to Long Bets to maintain the service.Since its inception in 02002, bets have covereda diverse set of topics, from when the humanpopulation will peak to when solar electricitywill become cheaper than fossil fuels.The Rosetta Project is a compendium ofall the world’s documented languages microetchedas readable text onto a three-inch waferof pure nickel. The disk was designed to lastfor millennia <strong>and</strong> act as a key to languagesthat may become lost or extinct. In 02009,one of the disks was accepted into the Smithsonian’sNational Anthropological Archive.Just as discovery of the original Rosetta Stoneallowed researchers to decipher ancient Egyptianhieroglyphics in the 1800s, this modernversion could provide the same service forfuture civilizations.All these projects, as well as a monthlyseminar series about long-term thinkinghosted by Stewart Br<strong>and</strong>, are attempts tochange the conversation. If society only workson problems that can be solved in a four- toeight-year election cycle, then none of the trulylarge issues can be tackled. Solving problemsin education, hunger, health care, macrofinance,population, <strong>and</strong> the environment allrequire a diligence <strong>and</strong> responsibility overdecades, if not centuries. If the right timeframe is used to solve these issues, whatwas once intractable can become possible.Humans are a tenacious species. Chancesare that 10,000 years from now, just like10,000 years ago, there will be people walkingon Earth. Just what kind of Earth, <strong>and</strong> justwhat kind of life those people may be living,will likely depend on the acorns we sow todaythat grow into the great oaks of our future.Alex<strong>and</strong>er RoseLong Now FoundationSource: See endnote 14.carbon fast as a way to demonstrate restraintin consumption <strong>and</strong> solidarity with peopleaffected by climate change. The call was supportedby Ed Millib<strong>and</strong>, the Minister of Energy<strong>and</strong> Climate Change in the United Kingdom,<strong>and</strong> promoted by a development agency, Tear-34 WWW.WORLDWATCH.ORG

STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Ritual <strong>and</strong> Taboo as Ecological Guardiansfund, which had enlisted more than 2,000people for the 2008 fast. Similarly, Muslims inChicago are being asked to “green Ramadan”by exp<strong>and</strong>ing their underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the annualritual fast to include eating locally grown food,reducing their household ecological footprintby 25 percent, switching to cleaner sources ofenergy, <strong>and</strong> stepping up the practices of recycling<strong>and</strong> walking. 16Fasting can be conceived more broadly toinclude a wide range of activities in modernconsumer societies. Many possibilities for settingaside consumerist habits already exist.World Carfree Day, for example, established in2000 to help people experience life without anautomobile, is now celebrated in more than 40countries. Bike to Work day is a similar effort.Earth Hour, which involves turning off lightsat a designated time, has become a worldwidephenomenon in the past few years. And TVTurnoff Week encourages families to watchless television <strong>and</strong> spend more time together. 17Meanwhile, in the United States, Buy NothingDay now st<strong>and</strong>s as a counteroffer to BlackFriday, <strong>and</strong> Take Back Your Time Day offerspeople the chance to say no to overwork <strong>and</strong>overscheduling <strong>and</strong> instead reclaim their timefor meaningful activities. Any of these “fasts”could conceivably become ritualized by religiousor secular groups to give them deepmeaning <strong>and</strong> impact. 18At a personal level, there are many opportunitiesto ritualize consumption <strong>and</strong> increasemindfulness about consumption habits.Indigenous practices could be a useful modelhere, especially the ritual of offering a small actof repentance or gratitude before using aresource. The Tlingit people of Alaska, forexample, who use the bark of cedar trees tomake clothing <strong>and</strong> other items, ask permissionof the spirits of the tree before harvesting thebark <strong>and</strong> promise to use only as much as theyneed. Imagine saying a silent prayer of thanks<strong>and</strong> a vow not to waste before every act ofmodern consumption. Such a private ritualwould likely bring mindfulness to a person’suse of resources. 19One example of a more mindful approachto personal consumption comes from PeterSawtell, a minister in Colorado who exploresthe link between spirituality <strong>and</strong> environmentalism.He has proposed that long-distancetravel, especially flying, become aritualized experience, with the Muslim ritualof the Hajj—the once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimageto Mecca—being the gold-st<strong>and</strong>ard model.Acknowledging that travel is enlightening,broadening, <strong>and</strong> even life-changing, Sawtellnevertheless suggests that because of the highenvironmental impact of trips by air, travelmay need to be intentional <strong>and</strong> sacred now.And while a once-in-a-lifetime trip may be toostrict a st<strong>and</strong>ard for most people, Sawtell suggeststhat once a decade or “once a life-stage”(adolescence, adulthood, retirement) mightbe helpful in thinking about long-distancetravel. In the process, he suggests, peoplemay find that less is more: they might appreciatetravel <strong>and</strong> use it more meaningfully thanwhen it was cheap <strong>and</strong> the environmentalimpact was ignored. Moreover, intentionaltravel could easily be ritualized, says Sawtell.“Imagine what it would be like in ourchurches if we celebrated the value of exceptionaltrips with special blessings for thosewho are embarking on this sort of once-in-alifetimepilgrimage.” 20In sum, ritual <strong>and</strong> taboo figure into manyaspects of any human life <strong>and</strong> help to transmit<strong>and</strong> shape cultural values. While resistant tocynical manipulation, these ancient humanpractices will likely find a place in developmentof new cultures of sustainability. In this epochthat cries out for rapid <strong>and</strong> comprehensivecultural transformation, human societies needto use every tool in the cultural toolbox.BLOGS.WORLDWATCH.ORG/TRANSFORMINGCULTURES 35

Environmentally SustainableChildbearingRobert EngelmanAlthough the idea seems pessimistic <strong>and</strong> is littlediscussed, it is possible that world population—at6.8 billion people today <strong>and</strong> growingby 216,000 a day—has already surpassed sustainablelevels, even if everyone on Earthachieved merely modest European rather thanlavish North American consumption levels. 1Estimates of what could be an environmentally“optimal” population are speculative<strong>and</strong> contentious. It could even be risky to venturea number, since some people might takeit as a target worth aiming at by any means necessary,voluntary or not. Nonetheless, it isclear that with its current range of behavior patterns,humanity is hazardously raising the heattrappingcapacity of the atmosphere,decimating the planet’s biological diversity,<strong>and</strong> risking future food scarcity by depletingfreshwater supplies <strong>and</strong> degrading soils.What if today’s widely varying per capitaconsumption rates worldwide met in somenarrow <strong>and</strong> modest range—but climate change<strong>and</strong> environmental deterioration continuedanyway? Might it then be time, or is it timealready, to evolve cultures that actively promotean average number of children born toeach woman so low that world populationshrinks in the near future? And if so, howcould that be accomplished in ethical <strong>and</strong>acceptable ways?The influence of modern culture on childbearingvaries widely. The range of modernhuman fertility suggests this diversity, withwomen in Bosnia <strong>and</strong> Herzegovina <strong>and</strong> in theRepublic of Korea having barely more than onechild each on average while women inAfghanistan <strong>and</strong> Ug<strong>and</strong>a average more thansix. Women around the world also vary greatly,however, in their access to family planning,which can help them decide whether any givensex act should or should not be open to conception<strong>and</strong> pregnancy. 2So it is not clear which is the larger determinantof fertility: culture <strong>and</strong> women’s (<strong>and</strong>men’s) response to its influence or simply theaccumulation of chance pregnancies that resultfrom sexual activity not effectively protectedagainst the risk of pregnancy. Yet with thenotable exception of China, where shortagesof natural resources are sometimes invoked tojustify the government’s one-child policy, itwould be hard to identify a significant culturein which very small families are promoted toassure environmental sustainability.Robert Engelman is vice president for programs at <strong>Worldwatch</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>and</strong> the author of More: Population,Nature, <strong>and</strong> What Women Want.36 WWW.WORLDWATCH.ORG

STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Environmentally Sustainable ChildbearingParadoxically, according to United Nationssurveys, many developing-country governmentsbelieve population growth is too rapidin their countries. And out of 41 NationalAdaptation Programmes of Action submittedby developing countries to the secretariat of theUnited Nations Framework Convention onClimate Change in recent years, 37 mentionedpopulation density or pressure as hinderingthe success of adaptation to theimpacts of climate change. Outsideof China, Viet Nam, <strong>and</strong>some individual states in India,however, such governmentalconcerns do not translate intoactual pressure on individualsto limit their procreation. 3For the people who workmost closely with population<strong>and</strong> reproduction—especiallyhealth care providers who helpwomen <strong>and</strong> their partners preventpregnancy or enjoy it ingood health when they want achild—this is as it should be. Infact, if there is any dominantglobal cultural paradigm aroundchildbearing, it centers onreproductive health <strong>and</strong> rights—a social recognition that it iswomen <strong>and</strong> their partners, <strong>and</strong> no one else,who should choose when to bear a child <strong>and</strong>should do so in good health.The closest thing to consensus on the perpetuallydivisive topic of human population isa principle first put in writing at a U.N. conferenceon human rights in Tehran in 1968 that“parents have a basic human right to determinefreely <strong>and</strong> responsibly the number <strong>and</strong> spacingof their children.” The adverb “responsibly”has sparked some debate, though not much inrecent years. It could, nonetheless, becomethe basis for discussion of what the word mightmean in a world where environmental sustainabilityis challenged by human activities. 4Twenty-six years after the Tehran conference,in 1994, another U.N. gatheringexp<strong>and</strong>ed on reproductive rights when representativesof almost all the world’s nationsagreed that encouraging healthy <strong>and</strong> effectivereproductive decisionmaking by women <strong>and</strong>their partners was the sole legitimate basis forgovernments to try to influence fertility levels<strong>and</strong> family size within their borders. 5Afghan girls get a meal along with their education.Abuses of reproductive rights have beenmore the exception than the rule in six decadesor so of global family planning experience.But those abuses—from incentive payments forsterilization to forced abortion documented inIndia <strong>and</strong> China <strong>and</strong> a h<strong>and</strong>ful of other countries—havesoured policymakers <strong>and</strong> healthcare providers on population policies, programs,or media messages aimed at convincingwomen <strong>and</strong> couples to have fewer childrenthan they would otherwise choose to have.Absent momentous changes in culture <strong>and</strong>politics around the world, it is difficult toimagine substantial professional or public supportevolving for aggressive promotion of fam-USAIDBLOGS.WORLDWATCH.ORG/TRANSFORMINGCULTURES 37

Environmentally Sustainable Childbearing STATE OF THE WORLD 2010© 2006 Helen Hawkings, courtesy Photoshareilies of just one child or at most two children.The scope for new cultural efforts aimed atconvincing couples to forego a wanted second,third, or fourth child for the sake of the environmentseems small. 6A young family visits a mobile health clinicoffering family planning services <strong>and</strong> basichealth care to members of marginalized ruralcommunities in the Dominican Republic.Does this mean that no conceivable culturaltransformation could help shrink the world’spopulation through lower birth rates? Not atall. (And, given the misunderst<strong>and</strong>ing thataccompanies this topic, it’s worth stating theobvious: population shrinkage based on higherdeath rates is not something to hope for.)There is much in today’s culture that promotespregnancies that individual women donot seek or want, <strong>and</strong> these cultural aspects arean easy immediate target for elimination orreversal. Similarly, there is scope for culturalchange that might lead couples to changetheir views about family size, though thisroute to lower fertility requires vigilance sothat the ultimate childbearing choice remainswith women <strong>and</strong> their partners, not with otherfamily members, the government, or thebroader society.Surprisingly, it is likely that global fertilitylevels would fall low enough to shrink worldpopulation if unintended pregnancies could beeliminated, although the reversal of growthwould take some time to occur. By the bestavailable estimate, nearly two out of five pregnanciesworldwide are not planned or soughtby the women who become pregnant. Thefigures are generally somewhat higher in lowfertilityindustrial countries than in high-fertilitydeveloping ones. 7Current average human fertility (2.5 childrenper woman) is only slightly above the fertilitythat would yield a stable human populationsize. (This is currently just above 2.3 children;stubbornly high death rates among the youngin many developing countries push the globalaverage above the usually cited figure of 2.1.)Moreover, all countries that offer women <strong>and</strong>their partners a range of choices of contraception,backed up by access to safe abortion,have fertility rates low enough to end or reversepopulation growth in the absence of net immigration.A world of fully intentional childbearingmight begin to lose population withintwo or three decades, perhaps sooner. 8Moreover, demographic research over severaldecades makes clear a strong correlationbetween levels of education <strong>and</strong> fertility. Thenumber of children women have in fact fallsroughly in proportion to their advancementthrough school. According to calculations bydemographers at the International <strong>Institute</strong>for Applied Systems Analysis, women with noschooling worldwide have on average 4.5 childreneach. Those with some primary schoolaverage 3 children, while those who completeat least one year of secondary school average1.9 children. And after just one or two yearsof college, fertility drops to 1.7 children per38 WWW.WORLDWATCH.ORG

STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Environmentally Sustainable Childbearingwoman—a rate well below population-maintaining“replacement” fertility. 9Given the force with which access to contraception<strong>and</strong> education for girls reduces fertility,it seems obvious that any culturalconstraints on these should be given first priorityin any move for reform. Unfortunately,such constraints are deeply rooted in humanunease with both sexuality <strong>and</strong> the idea ofgender equality. Cultural transformation musttackle these <strong>and</strong> advance the principle that allwomen should have control over their ownbodies <strong>and</strong> fertility <strong>and</strong> that all should haveopportunities equal to those of men—througheducation, media messages, <strong>and</strong> the work ofpolicymakers at all levels. Limitations on accessto contraception, such as requirements forparental permission or physician prescriptionsfor routinely safe options, are open to publicpressure for legislative or regulatory change.The use of sex <strong>and</strong> women’s bodies foradvertising or easy laughs in television situationcomedies fortifies the lower status of women<strong>and</strong> makes it even more likely that unintendedpregnancies will boost population growthrates—not to mention complicate the lives<strong>and</strong> undermine the aspirations of young people.One study found that the level of exposureto sexual content on television strongly predictedsubsequent teen pregnancy, with the 10percent of teenagers most exposed to televisionsex more than twice as likely to become pregnantwithin three years of the exposure as the10 percent with the lowest exposure. 10Such findings illustrate the power of culture—<strong>and</strong>of media culture in particular—toboost fertility or at least accelerate sexual initiation<strong>and</strong> subsequent childbearing. Combatingsuch cultural influences thus can play animportant role in lowering fertility <strong>and</strong> contributingto slower population growth. Moreover,there is evidence that media such astelevision <strong>and</strong> radio may contribute to lowerfertility just as easily as to higher. 11Where soap operas designed to model contraceptiveuse <strong>and</strong> small family norms areintroduced, perceptions on ideal family sizescan fall. For example, after the radio soapopera Apwe Plezi (derived from a Creole saying,“after the pleasure comes the pain”) wasaired in St. Lucia, of the 35 percent of the surveyedpopulation who had heard it, listenerswere more likely to trust family planningworkers, view extramarital sex as less acceptable,<strong>and</strong> favor families that averaged 2.5 childrenas opposed to 2.9 children for thosewho had not heard the show. While of courseother factors also contributed to this shiftingnorm—such as parallel increases in access tofamily planning resources—it is clear that themedia can play an important role in shapingfamily size norms. 12Another area ripe for cultural transformationis the dominant political view that anyjurisdiction in which population stops growingis headed, in the words of a recent WashingtonPost news story, for “slow-motiondemographic disaster.” A national election inlate 2008 in Japan, for example, seemed torevolve in large part on a proposed paymentof $276 per month to parents for each childyounger than high school age. In Russia,politicians have urged citizens to skip work tohave sex <strong>and</strong> have offered prizes—from refrigeratorsto a Jeep—to women who have a babyon Russia Day, June 12th. Both countrieshave declining populations. 13There is some evidence that incentives likethese can modestly boost a country’s fertility,with a greater effect among women with lowerincomes. Tax benefits targeted at parents on aper child basis, such as those in the UnitedStates, may have a similar impact—<strong>and</strong>, in fact,U.S. fertility has risen modestly in recent years,as has that in other wealthy countries. (In thecase of the United States, fertility has recentlyrisen to roughly the replacement value, whichfor that country is 2.1 children per woman.) 14Politicians justifiably worry that extremelylow birth rates will ultimately make it moreBLOGS.WORLDWATCH.ORG/TRANSFORMINGCULTURES 39

Environmentally Sustainable Childbearing STATE OF THE WORLD 2010challenging to support aging populations. Butthese <strong>and</strong> similar risks are manageable socialchallenges that pale in comparison to those theworld faces in addressing human-caused climatechange, the depletion of renewable freshwatersupplies, <strong>and</strong> the loss of the planet’sbiological diversity. Anyone who takes theseenvironmental problems seriously has goodreason to oppose the efforts of politicians,economists, <strong>and</strong> the media to promote higherbirth rates—as well as those of religious leaders,members of extended families, <strong>and</strong> otherswho urge pregnancy on women who have notchosen it for themselves.Finally, there is the constructive role thateducation <strong>and</strong> open discussion about thechanging environment <strong>and</strong> the relation of populationto its sustainability can play in shapingreproductive decisionmaking. Studying a lobster-fishingvillage in Quintana Roo, Mexico,geographer David Carr of the University ofCalifornia, Santa Barbara, found that culturalattitudes about childbearing had changed as thelobster resource declined. The use of contraceptionwas universal, <strong>and</strong> the community’sbirth rates were comparable to those of suchlow-fertility countries as Italy, Estonia, <strong>and</strong>Russia. The villagers Carr interviewed explicitlytied their modest family size intentions, sodifferent from those of their parents <strong>and</strong> gr<strong>and</strong>parents,to the importance of preserving thefishing resource for their children. 15Perhaps significantly, many villagers alsomentioned the influence on their own reproductiveambitions of television soap operasdepicting small North American families.While satellite television may not be consideredby many as a positive agent of culturaltransformation, in this case it may play a constructiverole by spreading an idea—a smallfamily norm—that contributes to environmentalsustainability more powerfully thanthe messages about wealth <strong>and</strong> consumptionmight undermine it.The sharp fall of fertility around the worldin recent decades is proof that culturally influencedreproductive behaviors can change surprisinglyfast. A family with roughly twochildren is already a cultural ideal in mostindustrial countries, albeit no doubt mostlyfor reasons unrelated to environmental sustainability.If nations soon reach a point wheregreenhouse gas emissions are actually capped<strong>and</strong> food <strong>and</strong> energy prices are high due to arising mismatch of supply <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong>, thereis no telling how cultural norms about childbearing<strong>and</strong> family size might evolve. It isnonetheless hard to imagine that environmentallyconcerned citizens seeking curbs inhuman population growth will ever gain muchpublic support for limiting reproductive rights.But the potential for cultural change thatwould slow <strong>and</strong> eventually reverse populationgrowth—supporting or at least not underminingindividual reproductive choice—is significant<strong>and</strong> worth pursuing.40 WWW.WORLDWATCH.ORG

Elders: A Cultural Resource forPromoting Sustainable DevelopmentJudi AubelThere is considerable discussion in westernindustrialized societies of the need to reexaminethe predominant global cultural paradigmof consumerism, which is clearlyunsustainable. In efforts to address currentchallenges to survival, the focus has been onhalting environmental degradation <strong>and</strong> promotingthe economic survival of communitiesaround the globe. Unfortunately, the degradationof the social environment <strong>and</strong> the breakdownin social connectedness have receivedmuch less attention. 1Another less frequently considered issue isthe relevance of the global cultural model ofconsumerism for other societies that face notonly environmental <strong>and</strong> economic challengesbut also problems specific to their history <strong>and</strong>cultural worldviews. Non-westernized <strong>and</strong>unindustrialized societies in Africa, Asia, LatinAmerica, <strong>and</strong> the Pacific are threatened by lesstangible forces that are undermining culturalidentities <strong>and</strong> decreasing social cohesion.One negative consequence of globalizationis that western individualistic, consumer-oriented,youth-focused values—communicatedthrough multiple international <strong>and</strong> nationalmedia <strong>and</strong> institutional channels—are underminingpositive traditions <strong>and</strong> values of morecollectivist sociocultural systems. In many cases,these traditions <strong>and</strong> values provide the basis forthe society’s sustainable use <strong>and</strong> developmentof both natural <strong>and</strong> human resources.Respecting the Wisdom of EldersA community elder in southern Senegalrecently lamented the fact that developmentprograms rarely pay attention to local culturalvalues: “There have been so many programscarried out in our community: to build moreschool classrooms; to construct a health center;to teach us how to grow more vegetables,how to prevent disease, about the importanceof sending girls to school, <strong>and</strong> of plantingtrees.” His testimony reflects the trend towardcarefully targeted development programs thataim to produce “tangible <strong>and</strong> quantifiableresults” corresponding to donor <strong>and</strong> governmentpriorities but that may fail to addressother less tangible cultural parameters thatmay be equally important for the survival of thecommunities the programs aim to support. Inspite of rhetoric about the need for “culturallyadapted” approaches, development policiesJudi Aubel, a specialist in community development <strong>and</strong> health in developing countries, is executive directorof the Gr<strong>and</strong>mother Project.BLOGS.WORLDWATCH.ORG/TRANSFORMINGCULTURES 41

Elders: A Cultural Resource for Promoting Sustainable Development STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Judi AubelElder <strong>and</strong> infant in a village in Rajasthan,India.<strong>and</strong> programs often unknowingly convey a setof western values that may be counterproductiveto the long-term social development <strong>and</strong>survival of non-western societies. 2One specific <strong>and</strong> decisive facet of nonwesterncultures that is rarely even dealt within discussions on culture <strong>and</strong> development isthe central role played by elders in socializingyounger generations, passing on indigenousknowledge <strong>and</strong> cultural values, <strong>and</strong> ensuringthe stability <strong>and</strong> survival of their societies.The late Andreas Fuglesang, awell-known leader in development communication,referred to the essential role playedby elder community members in more traditionalsocieties as the “information processingunit” of a community. As Malianphilosopher Amadou Hampâté Bâ notes,“When an elder person dies in Africa, it is asthough a whole library had burned down.” 3There is clearly incongruity between thecentrality of elders in non-western societies<strong>and</strong> the centrality of young people in developmentprograms—a problem that has gonelargely unnoticed. There is a growing clash ofcultures between younger members of society,who embrace more global values, <strong>and</strong> oldercommunity members who areholding on to more traditionalones. The tension between thetwo cultural orientations is seenin the decreased communications<strong>and</strong> learning betweenyoung people <strong>and</strong> elders. In thepast, for example, throughoutAfrica members of differentgenerations would sit under alarge tree in the community todiscuss the past, the present,<strong>and</strong> the future. In French, thedesignated tree was referred toas “l’arbre à palabres.” Today inmany communities, while eldersstill sit <strong>and</strong> discuss under suchtrees, young people are morelikely to gather around a radio or television tolook at images <strong>and</strong> hear stories of other places.Yet continuing respect for the wisdom ofelders is reflected in a proverb heard widelyacross Africa, “What an elder sees sitting on theground, a younger person cannot see even ifhe/she is up in a tree.” In a study in Senegal,community respondents of various ages statedthat knowledge is related to age <strong>and</strong>, consequently,elders are viewed as “knowledgeproviders” in key domains such as agriculture<strong>and</strong> health. And in India, Narender Chadha ofthe University of Delhi finds that, in spite ofvast economic <strong>and</strong> social changes, elders continueto comm<strong>and</strong> high respect as “they areconsidered as the storehouses of knowledge <strong>and</strong>wisdom within the family <strong>and</strong> community contexts.”This respect for traditional wisdom issimilarly found in other collectivist, non-westernsocieties in the Pacific <strong>and</strong> Latin America. 4Respect for the wisdom of elders is alsoevident in a new effort at the internationallevel to help find solutions to global problemsthat was initiated in 2007 by Nelson M<strong>and</strong>ela.He brought together a small number ofdistinguished world leaders <strong>and</strong> established agroup called The Elders. M<strong>and</strong>ela’s idea was42 WWW.WORLDWATCH.ORG

STATE OF THE WORLD 2010Elders: A Cultural Resource for Promoting Sustainable Developmentinspired by the role of elders in traditionalsocieties: to bring people together, to encouragedialogue, to provide guidance based ontheir experience. The Elders are currentlyworking on helping to solve several complex<strong>and</strong> conflict-ridden problems, including theIsraeli-Palestinian situation. 5In western individualist societies, however,attitudes toward elders are generally tainted bynegative images of aging. With the globalizationof culture, increasingly ageist attitudesare being disseminated <strong>and</strong> slowly permeatingnon-western cultures as well. And it has beenobserved that older women suffer from ageistbiases even more than men do: they are said tobe a bad influence on children <strong>and</strong> families, illiterate<strong>and</strong> therefore unintelligent, or too old tolearn <strong>and</strong> to change. 6Threats to IntergenerationalRelationshipsGlobalization involves a virtually one-way disseminationof western cultural images <strong>and</strong> valuestoward non-western societies. Only recentlyhas there been some concern at the internationallevel about globalization’s role in spreadingconsumerist cultural images <strong>and</strong> values<strong>and</strong> the resulting breakdown in intergenerationalrelationships in non-western societies.The 2005 World Youth Report from theUnited Nations cautioned, “Young peopleare increasingly incorporating aspects of othercultures from around the world into theirown identities. This trend…is likely to widenthe cultural gap between the younger <strong>and</strong>older generations.” Similarly, an analysis ofthe impact of globalization by the Youth Commissionon Globalisation calls attention to analarming situation: “The youth of the developingworld are attracted, lured or forcedinto non-traditional ways of being by a greatmany factors…<strong>and</strong> alienated from their traditionalcommunities. Such cultural disintegrationis the primary cause of problems such asthe loss of linguistic, historical <strong>and</strong> spiritual traditions,the break down of family supportstructures <strong>and</strong> the loss of a locally organisedpolitical voice.” 7Similar concern about the negative effects ofglobalization on young people in particularare expressed by Akopovire Oduaran of theUniversity of Botswana, who laments the lossof “the rich African tradition of intergenerationalrelationships…daily being weakened bythe increasing change in our value systems asour communities are opened up to culturalglobalization.” He argues that with consumerismhas come the loss of cultural traditions<strong>and</strong> weakened bonds <strong>and</strong> cooperationbetween family <strong>and</strong> community members—alldisturbing signs of diminished social cohesion. 8Yet there is some evidence that young peopleperceive the dangers of globalization. Membersof a Ghanaian youth club noted that“globalisation has brought us a life surroundedby mass-production <strong>and</strong> mass-consumption.…Wesee our own cultures giving way toa consumerist monoculture. There is an urgentneed to revisit, appreciate <strong>and</strong> participate in theevolution of our own cultures, which are community-oriented,non-materialistic, eco-friendly<strong>and</strong> holistic in their worldview.” Mamadou, a20-year-old Senegalese man, stated: “I ampart of a whole generation of young peoplewho are lost. We play soccer <strong>and</strong> watch televisionbut we don’t really belong to the westernworld. Our parents sent us to school butthere we didn’t learn about our culture <strong>and</strong> ourparents didn’t teach us where we came fromeither. We are lost between two worlds.” 9How are consumerist values communicatedto society at large <strong>and</strong> specifically to young peoplein developing countries? Three major institutionsare responsible: the mass media <strong>and</strong>advertising, development organizations <strong>and</strong>programs, <strong>and</strong> formal schools.Mass media <strong>and</strong> advertising are the majorvehicles for diffusion of western values intonon-western societies. While there is increasedBLOGS.WORLDWATCH.ORG/TRANSFORMINGCULTURES 43