Bodily mimesis as “the missing link” in human cognitive ... - CiteSeerX

Bodily mimesis as “the missing link” in human cognitive ... - CiteSeerX

Bodily mimesis as “the missing link” in human cognitive ... - CiteSeerX

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

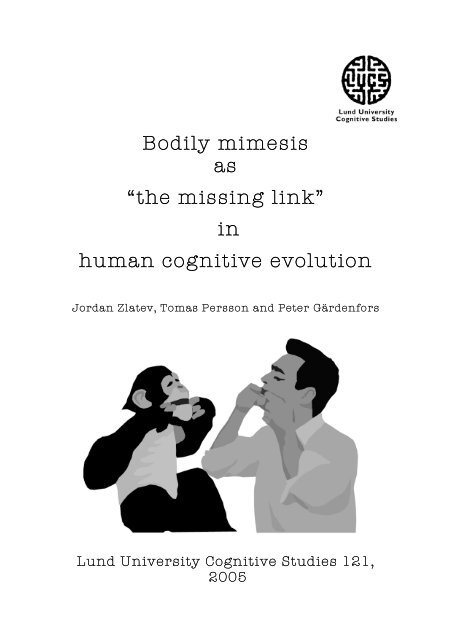

<strong>Bodily</strong> <strong>mimesis</strong><strong>as</strong><strong>“the</strong> <strong>miss<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>l<strong>in</strong>k”</strong><strong>in</strong><strong>human</strong> <strong>cognitive</strong> evolutionJordan Zlatev, Tom<strong>as</strong> Persson and Peter GärdenforsLund University Cognitive Studies 121,2005

Zlatev, Persson and Gärdenfors, Lund University Cognitive Science 121, (2005). 3F<strong>in</strong>ally, the units of language stand <strong>in</strong> complex<strong>in</strong>ternal semantic relations <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g e.g.complementarity (Deacon 1997) and grammaticalrelations <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g hierarchical structure andrecursivity (Hauser, Chomsky and Fitch 2002;Givón 2002). Noth<strong>in</strong>g of the k<strong>in</strong>d h<strong>as</strong> beenshown to exist <strong>in</strong> natural animal communication,though <strong>as</strong>pects of both semantic relations andgrammatical patterns are not beyond the gr<strong>as</strong>pof language-taught apes (Savage-Rumbaugh andLew<strong>in</strong> 1994).We may conclude that the six general differencesbetween language and animal communicationdiscussed <strong>in</strong> this section and summarized <strong>in</strong>Table 1 def<strong>in</strong>e two very different types of semioticsystems. Even though one may argue thatfor each of the <strong>in</strong>dividual features there may besome forms of animal communication thatwould appear to be “<strong>in</strong>termediary”, e.g. theflexible <strong>in</strong>terpretations of chimpanzee alarm callsby Diana monkeys (Zuberbühler 2000), no animal<strong>in</strong> the wild h<strong>as</strong> anyth<strong>in</strong>g approach<strong>in</strong>g the socially transmitted,voluntarily controlled, contextually flexible, triadicsemiotic system that is language.As po<strong>in</strong>ted out <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>troduction, the difficultquestion is to account why and how such adist<strong>in</strong>ctively “odd” (from a biological perspective)communication system emerged <strong>in</strong> the firstplace. Proposals <strong>in</strong> the currently explod<strong>in</strong>g literatureon language orig<strong>in</strong>s vary widely on whatthey f<strong>in</strong>d to be the crucial feature of <strong>human</strong>cognition that could “bridge the gap” to language:process<strong>in</strong>g of recursivity (Hauser, Chomskyand Fitch 2002; Bickerton 2003), enhancements<strong>in</strong> social cognition (Tom<strong>as</strong>ello 1999;Tom<strong>as</strong>ello et al. <strong>in</strong> press), mechanisms support<strong>in</strong>gthe learn<strong>in</strong>g and use of symbolic relations(Deacon 1997, 2003). In the present quest forthe Holy Grail of expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>human</strong> uniquenessthat tends to focus on the orig<strong>in</strong> of languagedifferent researchers tend to offer their favoritecandidate for <strong>“the</strong> <strong>miss<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>l<strong>in</strong>k”</strong> and do theirbest to support their hypothesis, often at theprice of disregard<strong>in</strong>g a good deal of evidence(see Johansson 2005). Our overall project similarlyaims to resolve the puzzle of what makes<strong>human</strong> be<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>cognitive</strong>ly and communicativelyspecial, but differs from the majority <strong>in</strong> (a) notfocus<strong>in</strong>g on language but on a skill that we argueis a prerequisite for language and (b) draw<strong>in</strong>g<strong>cognitive</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretations and toward more low-levelmechanisms l<strong>in</strong>ked to the particular stimulus featuresof the environment.” (Hauser 1996: 59)from a large number of empirical and theoreticalstudies.Table 1. Six characteristics of animal communicationand <strong>human</strong> language1. Degree oflearn<strong>in</strong>g2. Consciouscontrol3. Contextuality4. Interpretation5. Communicativerelations6. Systematicity(<strong>in</strong>ternal relationsandcomb<strong>in</strong>atorics)Animal communication(<strong>in</strong>the wild)None (“<strong>in</strong>nate”)orhighly limitedNone orhighly limitedTied to aparticularcontext(stimulussett<strong>in</strong>g)(Relatively)fixed responseDyadic:- Cue (environment,subject)- Signal (subject,recipient)None, orvery limitedHuman languageExtensiveHighFlexible, relatively<strong>in</strong>dependent fromspecific contextFlexible, “negotiable”Triadic:Speaker-addresseereferentHighAnimals and <strong>human</strong> be<strong>in</strong>gs differ not only <strong>in</strong>their means of communication, but <strong>in</strong> (apparently)non-communicative <strong>as</strong>pects of cognitionsuch <strong>as</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g, symbolic thought, <strong>“the</strong>ory ofm<strong>in</strong>d”, etc. In other words, there is a parallelbetween the “communicative gap” and the“<strong>cognitive</strong> gap”. What is the source of this parallelism?When it comes to ontogeny, a possibleexplanation for the source of the “higher functions”of <strong>human</strong> be<strong>in</strong>gs is the cl<strong>as</strong>sical proposallaid out by Vygotsky (1978) that the latter can beseen <strong>as</strong> result<strong>in</strong>g from the <strong>in</strong>ternalization of <strong>in</strong>terpersonalrelations and representations, or <strong>as</strong> expressed byVygotsky <strong>in</strong> an often quoted p<strong>as</strong>sage:Every function <strong>in</strong> the child’s cultural developmentappears twice: first, on the sociallevel, and later, on the <strong>in</strong>dividual level; firstbetween people (<strong>in</strong>terpsychological), and then<strong>in</strong>side the child (<strong>in</strong>trapsychological). This appliesequally to voluntary attention, to logicalmemory, and to the formation of concepts.

4<strong>Bodily</strong> <strong>mimesis</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>“the</strong> <strong>miss<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>l<strong>in</strong>k”</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>human</strong> <strong>cognitive</strong> evolutionAll the higher functions orig<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>as</strong> actual relationsbetween <strong>human</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals. (Vygotsky1978: 57)We wish to suggest that an evolutionary analogto this process, i.e. a process of hom<strong>in</strong>id selfenculturation<strong>in</strong> which more complex forms ofcommunication created selection pressures formore complex forms of cognition, can help usunderstand the close connections between thetwo “gaps”. Such a socio-cultural perspective on<strong>human</strong> cognition and its evolutionary orig<strong>in</strong>sdoes not conflict with, but rather presupposesthe crucial underly<strong>in</strong>g role of our general primatecognition (Donald 1991; Tom<strong>as</strong>ello 1999; Zlatev2003). In this article we will adopt such a bioculturalperspective <strong>as</strong> a general “work<strong>in</strong>g hypothesis”,without thereby argu<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>st more<strong>in</strong>dividual-b<strong>as</strong>ed alternatives (e.g. Gärdenfors2003). Ultimately, we will need a synthesis of thesocial and the <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>as</strong>pects of <strong>human</strong> cognition<strong>in</strong> order to make sense of the nature ofour major theoretical concept that is both <strong>in</strong>terand<strong>in</strong>tra-personal, <strong>as</strong> we show below.3. <strong>Bodily</strong> <strong>mimesis</strong>The concept of <strong>mimesis</strong> goes back at le<strong>as</strong>t to Aristoteles,but <strong>as</strong> far <strong>as</strong> <strong>human</strong> <strong>cognitive</strong> evolutionis concerned, we take our departure from the<strong>mimesis</strong> hypothesis of <strong>human</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>s presented byDonald (1991, 1998, 2001). This hypothesisstates that a specific form of communication andcognition (and correspond<strong>in</strong>g culture) mediatedbetween those of the common ape-ancestor andmodern <strong>human</strong>s b<strong>as</strong>ed on <strong>“the</strong> ability to produceconscious, self-<strong>in</strong>itiated, representationalacts that are <strong>in</strong>tentional but not l<strong>in</strong>guistic.”(Donald 1991: 168) In brief, Donald proposesthat while ape culture is b<strong>as</strong>ed on “episodic cognition”and <strong>as</strong>sociational learn<strong>in</strong>g, early Homo –most likely Homo erectus/erg<strong>as</strong>ter consider<strong>in</strong>g therelative jump <strong>in</strong> bra<strong>in</strong> size and material culturewitnessed at this stage of hom<strong>in</strong>id evolution –evolved a new form of cognition. What supportedthis w<strong>as</strong> the fact that the body could beused volitionally to do what somebody else isdo<strong>in</strong>g (imitation), to represent external eventsfor the purpose of communication or thought(mime, gesture) and to rehearse a given skill bymatch<strong>in</strong>g performance to a goal.The most important features that Donald attributesto <strong>mimesis</strong> are: (a) reference: mimetic representationsstand for someth<strong>in</strong>g (for someone);(b) <strong>in</strong>tentionality: this referential relationship isgr<strong>as</strong>ped both by the “mimer” and the <strong>in</strong>terpreter;(c) communicativity: the relationship <strong>in</strong> (b)can be used for the purpose of convey<strong>in</strong>gthoughts; (d) autocu<strong>in</strong>g: production is voluntary <strong>as</strong>opposed to <strong>in</strong>st<strong>in</strong>ctive; and (e) generativity: the“ability to “parse” one’s own motor actions <strong>in</strong>tocomponents and then recomb<strong>in</strong>e these components<strong>in</strong> various ways” (Donald 1991: 171).It can be observed that features (a)-(e) def<strong>in</strong>ea system of communication that is <strong>in</strong>termediatebetween animal communication and language, <strong>as</strong>characterized <strong>in</strong> Section 2 and Table 1. Like thelatter it is learned, flexible and possibly triadic.At the same time, it lacks the follow<strong>in</strong>g criticalfeatures of <strong>human</strong> language:• Conventionality: not just shared, but knownto be shared and thus a part of mutualknowledge (Itkonen 1978; Clark 1996); Notthat this is not the same <strong>as</strong> arbitrar<strong>in</strong>ess (seebelow), even though to notions are oftenmistakenly conflated. 2• Arbitrar<strong>in</strong>ess: the semiotic ground for theexpression-content relation requires neithersimilarity, nor contiguity (Peirce 1931-1935;Sonesson <strong>in</strong> press)• Extensive systematicity of the <strong>in</strong>ternal relationsamong signs (Deacon 1997; Zlatev2003).Thus the hypothesis that <strong>mimesis</strong> plays the roleof a “<strong>miss<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>l<strong>in</strong>k”</strong> (<strong>in</strong> the words of Donaldhimself) <strong>in</strong> <strong>human</strong> <strong>cognitive</strong> evolution is a prioriattractive. Furthermore, it h<strong>as</strong> been backed upby evidence from archeology, neurobiology,<strong>cognitive</strong> psychology and developmental psychology,such <strong>as</strong> the presence of a “mimeticstage” <strong>in</strong> <strong>human</strong> ontogeny and the presence ofmimetic thought <strong>in</strong> patients with total aph<strong>as</strong>ia,the homology between “mirror neuron” systems<strong>in</strong> monkeys used for action recognition, andstructures for the control of imitation, mentaliz<strong>in</strong>gand language <strong>in</strong> <strong>human</strong> be<strong>in</strong>gs (e.g. Donald1991, 2001; Nelson 1996; Zlatev 2002, 2005;Corballis 2002).2 It is also completely dist<strong>in</strong>ct from the so-calledconventionalization of behaviors discussed <strong>in</strong> theethological literature, for which we reserve the termritualization (see Section 6).

Zlatev, Persson and Gärdenfors, Lund University Cognitive Science 121, (2005). 5Nevertheless, the <strong>mimesis</strong> hypothesis h<strong>as</strong>been met with much resistance and criticism(Mitchell and Miles 1993; Tom<strong>as</strong>ello 1993; etc)that can be summarized <strong>as</strong> follows: On the onehand, Donald’s theory underestimates the cognitionof non-<strong>human</strong> primates with respect totool-mak<strong>in</strong>g and cultural traditions (Boesch2003) and their ability to understand others’<strong>in</strong>tentions (Tom<strong>as</strong>ello, Call and Hare 2003). Onthe other hand, features (a)-(e) attribute so muchrepresentational complexity to <strong>mimesis</strong>, that thisobviates the need for a second <strong>cognitive</strong> transitionto language (Laakso 1993). If this criticismis correct, then <strong>mimesis</strong> can hardly “bridge thegap” <strong>as</strong> required, s<strong>in</strong>ce it, so to speak, both givestoo little to the apes and too much to Homo erectus,thus effectively creat<strong>in</strong>g a second gap: betweenapes and Homo erectus, without any <strong>in</strong>dicationsof how it w<strong>as</strong> bridged <strong>in</strong> evolution. F<strong>in</strong>ally,Donald’s theory does not address the questionwhy <strong>mimesis</strong> evolved <strong>in</strong> the first place, and whyit later became superseded by language.Apart from these issues, Donald’s def<strong>in</strong>itionof <strong>mimesis</strong> is unclear with respect to at le<strong>as</strong>t thefollow<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>ts: Are the features (a)-(e) mentionedabove necessary and jo<strong>in</strong>tly sufficient orare some more central than others? Is there apriority for the communicative or the noncommunicativeforms of <strong>mimesis</strong>? In which wayshould one <strong>in</strong>terpret the notoriously ambiguousterms “reference” and “<strong>in</strong>tentionality”? Furthermore,if <strong>mimesis</strong> possesses all the features oflanguage except for phonetic realization <strong>as</strong>claimed by Laakso (1993), it rema<strong>in</strong>s unclearwhat exactly makes it “not l<strong>in</strong>guistic” <strong>in</strong> thewords of Donald quoted earlier. Hence, our firststep <strong>in</strong> elaborat<strong>in</strong>g the mimetic hypothesis of<strong>human</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>s is to offer a more specific(re)def<strong>in</strong>ition of the concept, which we refer to<strong>as</strong> bodily <strong>mimesis</strong> <strong>in</strong> order to dist<strong>in</strong>guish it fromthe broader concept with Aristotelian roots:(Def) <strong>Bodily</strong> <strong>mimesis</strong>: A particular act ofcognition or communication is an act of bodily<strong>mimesis</strong> if and only if:1. It <strong>in</strong>volves a cross-modal mapp<strong>in</strong>g betweenproprioception (k<strong>in</strong>aesthetic experience) andexteroception (normally dom<strong>in</strong>ated by vision),unless proprioception is compromised.(Cross-modality)2. It is realized by bodily motion that is, or canbe, under conscious control. (Volition)3. The body (part) and its motion correspondto – either iconically or <strong>in</strong>dexically – some action,object or event, but at the same time aredifferentiated from it by the subject. (Representation)4. The subject <strong>in</strong>tends for the act to stand forsome action, object or event for an addressee,and for the addressee to appreciate this(Communicative sign function)But it is not an act of bodily <strong>mimesis</strong> if:5. The act is fully conventional, i.e. a part ofmutual knowledge, and breaks up(semi)compositionally <strong>in</strong>to mean<strong>in</strong>gful subactsthat relate systematically to each otherand to other similar acts. (Symbolicity)This def<strong>in</strong>ition resolves some of the problemsmentioned earlier. By stat<strong>in</strong>g that bodily <strong>mimesis</strong><strong>in</strong>volves a mapp<strong>in</strong>g between proprioception, <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>gk<strong>in</strong>esthetic sense and the <strong>in</strong>put from sk<strong>in</strong>receptors and serv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>as</strong> our b<strong>as</strong>ic form of selfknowledge(e.g. Edelman 1992; Gallagher 1995,2005) and exteroception (above all vision, butalso hear<strong>in</strong>g and touch), this expla<strong>in</strong>s the sense<strong>in</strong> which bodily <strong>mimesis</strong> <strong>in</strong>volves the body, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gspecific organs such <strong>as</strong> the vocal tract –to the extent that they are <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> proprioceptive-exteroceptivemapp<strong>in</strong>g. S<strong>in</strong>ce speechproduction, and possibly even speech comprehensionaccord<strong>in</strong>g to the “motor theory ofspeech perception” (Liberman and Matt<strong>in</strong>gly1985) <strong>in</strong>volve such a mapp<strong>in</strong>g, this implies thateven speech <strong>in</strong>volves bodily <strong>mimesis</strong>, at thesame time <strong>as</strong> it transcends it due to symbolicity.By focus<strong>in</strong>g on full conventionality and systematicity<strong>as</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g language from bodily<strong>mimesis</strong>, it becomes clear <strong>in</strong> which sense <strong>mimesis</strong>is “not l<strong>in</strong>guistic”. Most importantly, however,the five criteria <strong>in</strong> the def<strong>in</strong>ition of bodily<strong>mimesis</strong> presented above allow us to cl<strong>as</strong>sify<strong>human</strong> and ape socio-<strong>cognitive</strong> skills along <strong>as</strong>cale consist<strong>in</strong>g of at le<strong>as</strong>t four dist<strong>in</strong>ct stages.We refer to this <strong>as</strong> the <strong>mimesis</strong> hierarchy (see Table2).Acts which only fulfill the first condition, butnot the others can be def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>as</strong> proto-mimetic.Neonatal face-mirror<strong>in</strong>g and cross-modal match<strong>in</strong>g(Meltzoff and Moore 1977, 1983, 1994) canbe regarded <strong>as</strong> such, and these have been witnessed<strong>in</strong> newborn chimpanzees <strong>as</strong> well (Myowa-Yamakoshi et al. 2004). On the other hand, bothdeferred imitation and mirror self-recognition fulfillconditions (1)-(3) and thus show a full form ofbodily <strong>mimesis</strong>. Skills such <strong>as</strong> these presupposethat the subject can both differentiate betweenhis own (felt) bodily representation, and the

6<strong>Bodily</strong> <strong>mimesis</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>“the</strong> <strong>miss<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>l<strong>in</strong>k”</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>human</strong> <strong>cognitive</strong> evolutionentity that this representation corresponds to,and to see the first <strong>as</strong> stand<strong>in</strong>g for the latter. Thisis what Piaget (1945) called ‘the symbolic function’and argued that it appears at the end of thesensorimotor period of the child’s development.Sonesson (1989, <strong>in</strong> press) uses differentiation <strong>as</strong> thecrucial criterion to dist<strong>in</strong>guish between truesigns, which display it, and pre-sign mean<strong>in</strong>gs,which do not. Note, however, that such representation,<strong>as</strong> <strong>in</strong> Piaget’s example of the childmodel<strong>in</strong>g the open<strong>in</strong>g and clos<strong>in</strong>g of a matchboxwith his mouth, is not <strong>in</strong>tentionally communicative.Therefore, if condition (4) is not fulfilled itis bodily <strong>mimesis</strong> only of a dyadic sort. If it isfulfilled, then we have triadic <strong>mimesis</strong>, such <strong>as</strong> that<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> pantomime or declarative po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g. F<strong>in</strong>ally,condition (5) dist<strong>in</strong>guishes between <strong>in</strong>tentionalgestural communication, and signed language,which also possesses the properties ofconventionality and systematicity (S<strong>in</strong>gleton,Goldw<strong>in</strong>-Meadow and McNeill 1995).Table 2. The <strong>mimesis</strong> hierarchy. Def<strong>in</strong>itions of the fourevolutionary stages (for terms <strong>in</strong> italics, see the def<strong>in</strong>itionof bodily <strong>mimesis</strong> <strong>in</strong> the text) and examples ofcorrespond<strong>in</strong>g types of acts.Stage Def<strong>in</strong>ition ExamplesProto<strong>mimesis</strong>Dyadic<strong>mimesis</strong>Triadic<strong>mimesis</strong>Jo<strong>in</strong>t attention,declarativepo<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g, pantomimePost<strong>mimesis</strong>A bodily act <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>gCross-modality withproprioception, butlack<strong>in</strong>g Volition orRepresentation (or both)An <strong>in</strong>terpersonal or<strong>in</strong>trapersonal bodilyact display<strong>in</strong>g Volitionand Representation, butnot Communicative signfunctionAs dyadic <strong>mimesis</strong> butalso <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g Communicativesign functionAs triadic <strong>mimesis</strong>,but also <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>gSymbolicityFacial expressions,bodilysynchronizationShared attention,imperativepo<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g, mirrorself-recognition,do-<strong>as</strong>-I-doimitationSigned languageIn the rema<strong>in</strong>der of this article we shall apply theproposed <strong>mimesis</strong> hierarchy to the evolution(and to a lesser degree, the ontogeny) of three<strong>cognitive</strong>-communicative capabilities: imitation(Section 4), <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity (Section 5), and gestures(Section 6). By analyz<strong>in</strong>g evidence from primatology,and to a smaller extent child development,we will identify levels with<strong>in</strong> these doma<strong>in</strong>sthat correspond to the levels of the <strong>mimesis</strong>hierarchy. In other words, we considerwhether there are simple forms of these capacitiesthat are <strong>in</strong> essence proto-mimetic; whetherthere are forms that are dyadic mimetic; whetherthere is furthermore evidence for communicative<strong>in</strong>tentions, and thus for triadic <strong>mimesis</strong>.F<strong>in</strong>ally we <strong>as</strong>k whether there are specific formsof imitation, <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity and gesture thatdepend on the acquisition of a conventionalsymbolic system, i.e. language, and are thus postmimetic.We will show that the progression protomimetic> dyadic-mimetic > triadic-mimetic > postmimetic,<strong>in</strong>stead of the dichotomy animal signal<strong>in</strong>gvs. <strong>human</strong> language outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Section 2,and <strong>in</strong> particular by dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g between dyadicand triadic <strong>mimesis</strong>, h<strong>as</strong> implications for atheory of the orig<strong>in</strong>s of <strong>human</strong> <strong>cognitive</strong>uniqueness. It may seem that such a theory goesaga<strong>in</strong>st the stream of much current theoriz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>evolutionary science s<strong>in</strong>ce it <strong>in</strong>vokes relativelydiscrete “stages” requir<strong>in</strong>g qualitative transitions,while both the nature of evolutionary processes<strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g many small mutations and the availablefissile evidence seem to speak <strong>in</strong> favor of aprolonged gradual process (Johansson 2005).However, we h<strong>as</strong>ten to note that there is nocontradiction between the stage-like theory thatwe will pursue and the evolutionary evidence.Firstly, it is completely possible to have relativelydiscrete transitions, or “punctuated equilibria”(Eldredge and Gould 1972) with<strong>in</strong> a b<strong>as</strong>icallygradual framework, i.e. without this imply<strong>in</strong>g anyform of “saltations” or sudden “macromutations”(Dessalles 2004). The likelihood forfairly rapid and abrupt changes is even higherwhen biological and cultural evolution <strong>in</strong>teract,<strong>as</strong> h<strong>as</strong> most likely been the c<strong>as</strong>e with <strong>human</strong><strong>cognitive</strong> evolution <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g language (Deacon1997). Secondly, our notion of a <strong>mimesis</strong> hierarchy,<strong>as</strong> other similar constructs (Dennett 1996;Zlatev 2003), is meant to serve primarily <strong>as</strong> aconceptual role <strong>in</strong> help<strong>in</strong>g us relate and compareprimate skills <strong>in</strong> somewhat different doma<strong>in</strong>s: itis not an evolutionary ladder for cl<strong>as</strong>sify<strong>in</strong>g differentspecies, which may very well have differentdegrees of the mimetic skills under discussion,and thus form much more of a cl<strong>in</strong>e. Withthese caveats we proceed with our analysis.

Zlatev, Persson and Gärdenfors, Lund University Cognitive Science 121, (2005). 74. Mimesis and imitationChimpanzees, bonobos, gorill<strong>as</strong> and orangutanscan copy behavior to some extent and <strong>in</strong> seem<strong>in</strong>glyvarious ways. The literature on ape imitation<strong>in</strong> the broad sense of the term (see Whitenet al. 2004 for a recent review) can for our purposesbe grouped <strong>in</strong>to the follow<strong>in</strong>g ma<strong>in</strong> experimentalparadigms: Neonatal mimick<strong>in</strong>g Instrumental tool-use Experiments with “artificial fruits” (puzzleboxes) “Do-<strong>as</strong>-I-do” t<strong>as</strong>ks- <strong>in</strong> respect to body movements (“Simonsays”)- <strong>in</strong> manipulation of objects Ethological methods (i.e. field observationsof food process<strong>in</strong>g techniques or <strong>in</strong>directevidence from local traditions)Most obviously relevant for our discussion ofstages of bodily <strong>mimesis</strong> are those types of observationallearn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> which an observer copiessometh<strong>in</strong>g of a model’s bodily actions, may it be <strong>in</strong> alaboratory tool-us<strong>in</strong>g situation, natural forag<strong>in</strong>gsituation or mimick<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a do-<strong>as</strong>-I-do game.Other forms of observational or social learn<strong>in</strong>g,like emulation, available <strong>in</strong> several versions (Byrne1998; Custance, Whiten and Fredman 1999),response facilitation (see Byrne 1999), and stimulusandlocal enhancement (see Tom<strong>as</strong>ello 1996), can<strong>in</strong>form observers about properties of the environmentand objects, or the connection betweencerta<strong>in</strong> manipulations and outcomes, but do not<strong>in</strong>volve copy<strong>in</strong>g bodily actions per se and thus itis not clear if they <strong>in</strong>volve bodily <strong>mimesis</strong>.For our purposes, the collective term imitationperta<strong>in</strong>s most clearly to the copy<strong>in</strong>g of bodilymotions (the do-<strong>as</strong>-I-do experimental paradigm)<strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> to imitation on the action level <strong>in</strong> objectmanipulation. The notion of action level imitationw<strong>as</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>ally contr<strong>as</strong>ted to that of programlevel (Byrne and Russon 1998), the latter be<strong>in</strong>gthe hierarchical organization of a series of actionsand the former the execution of an <strong>in</strong>dividualcomponent action. Note that imitation onthe program level can take place without imitationon action level. The program level h<strong>as</strong> beenfurther divided by Whiten (1998) <strong>in</strong>to be<strong>in</strong>geither of a sequential or a hierarchical k<strong>in</strong>d. Anexample of sequence imitation from the artificialfruitexperiments would be to manipulate obstacleA before obstacle B, while an example ofimitation on the action level would be pok<strong>in</strong>g vs.pull<strong>in</strong>g to remove a plug. If the subject copiesthe manual movement of the model, it is regarded<strong>as</strong> an <strong>in</strong>stance of action-level imitation,but if the ape <strong>in</strong>stead copies the movement ofthe plug, it is categorized by Custance et al.(1999) <strong>as</strong> object movement re-enactment. The latter isusually regarded <strong>as</strong> a form of emulation, wherethe end state of an event is achieved (or copied)but the subject <strong>in</strong>vents his or her own way toachieve this end and the model is <strong>in</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesuperfluous. However, s<strong>in</strong>ce object movementre-enactment is a special k<strong>in</strong>d of emulationwhere at le<strong>as</strong>t the direction of the movement ofthe object is copied, <strong>in</strong> our analysis it wouldqualify <strong>as</strong> a form of bodily <strong>mimesis</strong>.There is also the hypothetical c<strong>as</strong>e where thesubject only learns that the plug can be movedand then proceeds to br<strong>in</strong>g about that effect <strong>in</strong>whatever way he or she prefers. To determ<strong>in</strong>ewhat is what, however, is a tricky bus<strong>in</strong>ess. Inthe latter c<strong>as</strong>e the subject might happen to br<strong>in</strong>gabout by chance the same movement of the plug<strong>as</strong> the model showed, and thus give the impressionof object movement re-enactment. Furthermore,<strong>in</strong> both a false and <strong>in</strong> a true c<strong>as</strong>e ofobject movement re-enactment, the subject canalso happen to perform the same manual actions<strong>as</strong> the model by chance and give the impressionof bodily imitation on the action level. At le<strong>as</strong>tthree forms of observational learn<strong>in</strong>g can thusyield the same expression: simple emulation,object movement re-enactment and action levelimitation. The experiments with artificial fruits,some of which we will review below, are designedto te<strong>as</strong>e apart these copy<strong>in</strong>g strategies.The failures of great apes to fully copy behavior<strong>in</strong> several early studies led Tom<strong>as</strong>ello,Kruger and Ratner (1993) to conclude that apesemulate, but cannot imitate, s<strong>in</strong>ce imitation <strong>in</strong>their view entails copy<strong>in</strong>g both of the goal andthe method to br<strong>in</strong>g about that goal. ForTom<strong>as</strong>ello and his collaborators imitation thush<strong>as</strong> a <strong>“the</strong>ory of m<strong>in</strong>d” component by def<strong>in</strong>ition,and on the b<strong>as</strong>is of the imitation data, the grouph<strong>as</strong> argued that apes lack an understand<strong>in</strong>g ofothers <strong>as</strong> <strong>in</strong>tentional agents (e.g. Tom<strong>as</strong>ello1999). S<strong>in</strong>ce then both the field of primate imitationstudies h<strong>as</strong> expanded and the MPI Leipziggroup h<strong>as</strong> modified their views on apes’ abilitiesto understand <strong>in</strong>tentional agency (Tom<strong>as</strong>ello etal. <strong>in</strong> press, see Section 5 for more discussion).

8<strong>Bodily</strong> <strong>mimesis</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>“the</strong> <strong>miss<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>l<strong>in</strong>k”</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>human</strong> <strong>cognitive</strong> evolutionDonald’s def<strong>in</strong>ition of <strong>mimesis</strong> (presented <strong>in</strong>Section 3), compris<strong>in</strong>g reference, <strong>in</strong>tentionality, communicativity,autocu<strong>in</strong>g and generativity, is difficult toapply to non-<strong>human</strong> primate imitation becauseobservational learn<strong>in</strong>g through copy<strong>in</strong>g h<strong>as</strong> beenstudied <strong>in</strong> non-communicative tool us<strong>in</strong>g andpuzzle box situations, with few exceptions such<strong>as</strong> the study by Tom<strong>as</strong>ello et al. (1994) on chimpanzeegestures <strong>in</strong> which the authors did notf<strong>in</strong>d any observational learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> functionalgesture acquisition. However, us<strong>in</strong>g ourdef<strong>in</strong>ition (see Section 3), it is possible to applythe concept of bodily <strong>mimesis</strong> to f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> thefield of ape imitation. As we will show <strong>in</strong> thissection, these f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs can be <strong>in</strong>terpreted <strong>as</strong>evidence that apes are capable of at le<strong>as</strong>t protomimeticand dyadic mimetic imitation, and possiblyeven triadic mimetic imitation when a communicativesign function is added.4.1 Proto-mimetic imitationIn what we call proto-mimetic imitation there is(iconic) resemblance between the copy and thecopied, which is probably b<strong>as</strong>ed on a b<strong>as</strong>ic formof identification with the model (see Section5.1). For this to be cl<strong>as</strong>sified <strong>as</strong> proto-mimeticrather than dyadic-mimetic, there should be noclear evidence for volition or for differentiationbetween oneself and the model.The prime candidate for proto-mimetic imitationis neonatal facial mirror<strong>in</strong>g. In the c<strong>as</strong>e of<strong>human</strong> neonatal mirror<strong>in</strong>g, the field is dividedbetween those who prefer a m<strong>in</strong>imalist <strong>in</strong>terpretationand those who argue for a more mentalisticone. For example, Anisfeld (1996) <strong>in</strong> a metaanalysisof experiments by Meltzoff and Mooreand Heimann argues that the <strong>in</strong>fant’s response islimited to one facial movement, tongue protrusion,and not several. If so, it would be a largelyreflexive form of mirror<strong>in</strong>g unlikely to requirevolition on the part of the <strong>in</strong>fant, and thus wouldbe proto-mimetic. On the other hand Meltzoffand Moore (1977, 1983, 1994) have argued thatthe <strong>human</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant not only displays volition (i.e.choice on whether to imitate or not, and abilityto mirror more than tongue protrusion), but thathe/she differentiates between him/herself and themodel. Meltzoff and Moore (1994) argue thatthere is evidence for deferred imitation <strong>in</strong> 6-week-old <strong>in</strong>fants who imitated the action whensee<strong>in</strong>g the model aga<strong>in</strong> after a delay of 24 hours.While differentiation <strong>in</strong> itself does not requirethe k<strong>in</strong>d of displacement that is witnessed <strong>in</strong>deferred imitation (see Sonesson <strong>in</strong> press), weagree with Piaget (1945) that the capacity fordeferred imitation rests on at le<strong>as</strong>t a simple formof representational activity. Thus, if the Meltzoff-Moore<strong>in</strong>terpretation of neonatal imitationis correct, we must conclude that <strong>human</strong> childrenperform dyadic imitation (see below) froma very early age.In the c<strong>as</strong>e of apes, newborn chimpanzeeshave been shown to have a period of <strong>in</strong>natemirror<strong>in</strong>g responsiveness to <strong>human</strong> facial stimuli(mouth open<strong>in</strong>g and tongue protrusion) that ispresent to 11 (Myowa-Yamakoshi 2001) or 9(Myowa-Yamakoshi et al. 2004) weeks of age.This shows that neonate chimpanzees have (atle<strong>as</strong>t) the capacity for proto-<strong>mimesis</strong> with respectto faces. It is to our knowledge not yettested whether this capacity also <strong>in</strong>volves differentiationor volition. But different sources forhighly similar responses <strong>in</strong> <strong>human</strong> and ape newbornsseem unlikely.4.2 Dyadic-mimetic imitationIn what we call dyadic-mimetic imitation, thesubject differentiates between self and modeland understands that a bodily posture or motioncan correspond to someth<strong>in</strong>g else, like an objector action. However, there is no attempt tocommunicate this “someth<strong>in</strong>g else” to another<strong>in</strong>dividual by means of the bodily motion.In a non-communicative sett<strong>in</strong>g, like <strong>in</strong> theexperiments on social learn<strong>in</strong>g studied with non<strong>human</strong>primates the “someth<strong>in</strong>g else” mentionedabove would be to understand the mean<strong>in</strong>gof a model’s actions: what the model is try<strong>in</strong>gto achieve. As mentioned above, imitat<strong>in</strong>g thegoal <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> the means to br<strong>in</strong>g about that goalis the hallmark of (true) imitation accord<strong>in</strong>g toTom<strong>as</strong>ello, Kruger and Ratner (1993), and <strong>in</strong>volvescerta<strong>in</strong> levels of <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>gunderstand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>in</strong>tentions.When try<strong>in</strong>g to implement the imitation ofgoals <strong>in</strong> an experimental sett<strong>in</strong>g the goal is oftento get hold of a food item, and these experimentshave tended to either foster <strong>in</strong>novation oruse of old reliable methods. This is not surpris<strong>in</strong>g.If you truly want to get hold of a food item,and apes clearly do so, the most effective means

Zlatev, Persson and Gärdenfors, Lund University Cognitive Science 121, (2005). 9one can come up with is used, and that is notnecessarily the one witnessed.The well-known rake experiment of Nagell etal. (1993) is an example of imitation studies us<strong>in</strong>gan <strong>in</strong>strumental tool. If there is any learn<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the c<strong>as</strong>e of apes it is generally consideredto be <strong>in</strong> the form of emulation: the subjectslearn someth<strong>in</strong>g new about tools, theirmovements or the environment, but not aboutthe bodily actions the model is us<strong>in</strong>g to br<strong>in</strong>gabout the <strong>in</strong>tended goal.Better imitation results have been obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>experiments with so called “artificial fruits”, i.e.boxes with obstacles that the subject h<strong>as</strong> to workaround <strong>in</strong> order to get to the food content.These experiments address the question: Whatdo apes spontaneously copy when they get anopportunity to observe a model? Which strategiesand mechanisms of social learn<strong>in</strong>g are <strong>in</strong>volved?The artificial fruit experimental paradigmh<strong>as</strong> yielded mixed results, <strong>as</strong> strategies ofresult emulation, object movement reenactment,action-level imitation and sequenceimitation have been recorded (Whiten et al.2004). The results seem to vary over fruit usedand species tested and/or age of subjects (Sto<strong>in</strong>skiand Whiten 2003; Custance et al. 2001; Sto<strong>in</strong>skiet al. 2001; Whiten et al. 1996). Action-levelimitation implies that the subject can represent amodel’s manual movements and re-enact thesefrom memory. Perform<strong>in</strong>g sequence imitationmeans that the subjects are also able to parse <strong>as</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>g of component actions and later re<strong>as</strong>semblethese <strong>in</strong> the same f<strong>as</strong>hion from memory,which aga<strong>in</strong> show their ability to re-enact detachedrepresentations voluntarily.Apes have demonstrated some skills of action-leveland sequence imitation, but at thesame time they experience some difficulties withthem <strong>as</strong> evident by their lack of full copy<strong>in</strong>g.Imitat<strong>in</strong>g the use of familiar motor actions <strong>in</strong>novel situations seem to come about more e<strong>as</strong>ily<strong>in</strong> apes than copy<strong>in</strong>g new motor actions altogether(Myowa-Yamakoshi and Matsuzawa1999). Especially for young <strong>in</strong>dividuals actionsare more likely to be copied if they are close tothe ones already <strong>in</strong> the subjects’ repertoire(Bjorklund et al. 2002). It is not yet settledwhether apes’ relatively poor performance ondetailed imitation of bodily actions is due tomotor-perceptual <strong>as</strong>pects or skills <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity.However, s<strong>in</strong>ce recent studies have shownthat at le<strong>as</strong>t chimpanzees have a degree of understand<strong>in</strong>gof the mentality of others (see belowand Section 5.2), the motor-perceptual explanationshould not be underestimated.Goal directedness is lack<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the most bodilymimetic paradigm, the “do-<strong>as</strong>-I-do” experiments,where part of mak<strong>in</strong>g sure that the copyis acquired through observation is to performnever-before seen, or at le<strong>as</strong>t unusual, movementswithout any practical function. There isno food item to get to at the end of the actionsequence. The subject is verbally <strong>as</strong>ked to do thesame <strong>as</strong> the model on cue. The do-<strong>as</strong>-I-do paradigmis an example of studies that <strong>as</strong>k the question:Can apes copy behavior? The answer ispositive. Both cross-fostered (or “enculturated”)apes, e.g. the orangutan Chantek (Miles et al.1996) and the chimpanzee Viki (Custance et al.1995), and chimpanzees with more moderate<strong>human</strong> upbr<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g (Custance et al. 1995) canp<strong>as</strong>s these tests. Once they understand themean<strong>in</strong>g of the “do the same” command, anyfaults <strong>in</strong> the copy is bound to be motorperceptualand not due to <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity issues.The do-<strong>as</strong>-I-do experiments prove thatapes are capable of both volition and representation(they represent the model’s body), which qualifythem <strong>as</strong> dyadic-mimetic imitators. However,learn<strong>in</strong>g the concept of SAMENESS may <strong>in</strong>fluencethe performance of apes profoundly. Thompson,Boysen and Oden (1997) found that language-naïvechimpanzees learned to judge relationsbetween relations (A is to A <strong>as</strong> B is to B,and not <strong>as</strong> C is to D) <strong>in</strong> a match<strong>in</strong>g-to-samplet<strong>as</strong>k only if the subjects had previously learned atoken for the concept SAME. Ord<strong>in</strong>ary match<strong>in</strong>gto-sampletra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g could not yield the same result.Experiments that h<strong>in</strong>ge on the subject “gett<strong>in</strong>gthe po<strong>in</strong>t of the game”, so to speak, haveimplications for ecological validity s<strong>in</strong>ce theexperimenter h<strong>as</strong> to plant certa<strong>in</strong> knowledge <strong>in</strong>the subject that it might not have stumbled uponnaturally. This is especially problematic for evolutionaryre<strong>as</strong>on<strong>in</strong>g around comparative experimentalpsychology, s<strong>in</strong>ce it is not clear whatcircumstances would have “planted” suchknowledge <strong>in</strong> the hom<strong>in</strong>id l<strong>in</strong>e.Deferred imitation on objects, <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g do<strong>as</strong>-I-doimitation, is perhaps the most promis<strong>in</strong>gevidence for dyadic mimetic capacities <strong>in</strong> apes.In these experiments the subject is shown actionson objects and is then either <strong>as</strong>ked to “dothe same th<strong>in</strong>g” (if the verbal command islearned) or (if not) the spontaneous handl<strong>in</strong>g of

Zlatev, Persson and Gärdenfors, Lund University Cognitive Science 121, (2005). 11tak<strong>in</strong>g have shown that chimpanzees know theimportance of others’ visual attention, both <strong>in</strong>communicative contexts (Tom<strong>as</strong>ello et al. 1994;Krause and Fouts 1997; Pika, Liebal andTom<strong>as</strong>ello 2003, 2005) e.g. use of attentiongett<strong>in</strong>ggestures and competitive contexts (Hareet al. 2000; Hare, Call and Tom<strong>as</strong>ello 2001).Apes also seem to be able to dist<strong>in</strong>guish <strong>in</strong>tentionalfrom accidental acts (Call and Tom<strong>as</strong>ello1998) and to judge an experimenter <strong>as</strong> eitherunwill<strong>in</strong>g or unable to give them a treat (Call etal. 2004). The conclusion is therefore that apesdo understand second-order mentality, at le<strong>as</strong>t <strong>in</strong>the form of second-order attention and (possibly)second-order <strong>in</strong>tentions. However, understand<strong>in</strong>gthe communicative sign function, andthus triadic <strong>mimesis</strong>, requires third-order mentality– <strong>as</strong> we will argue <strong>in</strong> Section 5 – and there isyet no clear evidence that (non-enculturated)apes are capable of this.Possible <strong>in</strong>stances of triadic mimetic imitation<strong>in</strong> non-<strong>human</strong> primates would be copy<strong>in</strong>gof referential signs <strong>in</strong> language-taught apes.However, most of the learn<strong>in</strong>g of signs by apesthat have been taught a signed language, such <strong>as</strong>the gorill<strong>as</strong> Koko and Michael (Bonvillan andPatterson 1993, 1999), the chimpanzee W<strong>as</strong>hoe(Fouts 1972) and the orangutan Chantek (Miles1990) takes place by gett<strong>in</strong>g the hands molded<strong>in</strong>to the signs and therefore does not qualify <strong>as</strong>either imitation or bodily <strong>mimesis</strong>. Still, Gardnerand Gardner (1969) also used the “do-<strong>as</strong>-I-do”paradigm to teach new signs to W<strong>as</strong>hoe withsome success. A more general problem, however,is that it is difficult to dist<strong>in</strong>guish the imitativelearn<strong>in</strong>g of such signs from post-<strong>mimesis</strong>s<strong>in</strong>ce these apes were taught a simplified form ofAmerican Sign Language (ASL), and that impliesthat they were exposed to, and possibly evenacquired at le<strong>as</strong>t a degree of symbolicity (<strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>gconventionality and systematicity). In a studyof the functions of the repetition of lexigrams bylanguage-tra<strong>in</strong>ed chimpanzees and bonbobosGreenfield and Savage-Rumbaugh (1993) reportat le<strong>as</strong>t some clear c<strong>as</strong>es of the acquisition oflexigrams through imitation. At the same timeSavage-Rumbaugh and Lew<strong>in</strong> (1994) emph<strong>as</strong>izethat only when the chimpanzees Sherman andAust<strong>in</strong> acquired the referential mean<strong>in</strong>g of thelexigrams, after a prolonged and laborious processof tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, could they match lexigrams tosamples.Perhaps the most conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g evidence fortriadic-mimetic imitation <strong>in</strong> apes <strong>in</strong>volves the<strong>in</strong>vention of iconic signs by Koko (Patterson1980) and Chantek (Miles 1990). Such sign areexamples of representation (the ape representssometh<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the environment) and communicativesign function (the ape addresses this to his or hercaregivers). S<strong>in</strong>ce the imitation is creative, <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>gthe resemblance (iconicity) between thesign and the way the referent is typically used, itcannot be solely a product of be<strong>in</strong>g taught <strong>as</strong>ymbolic code. The fact that Koko’s and Chantek’ssign <strong>in</strong>ventions build on iconicity suggestthat they are c<strong>as</strong>es of triadic-mimetic rather thanpost-mimetic imitation. We return to these c<strong>as</strong>es<strong>in</strong> Section 6.4.4 Post-mimetic imitationWhile speech may be regarded <strong>as</strong> <strong>in</strong> part postmimetic(see Section 3), the paradigm exampleof post-<strong>mimesis</strong> is signed language: it is b<strong>as</strong>ed oncross-modal mapp<strong>in</strong>g between proprioceptionand vision, and possesses the other features of<strong>mimesis</strong>: volition, representation and communicativefunction. Furthermore, it is symbolic, not <strong>in</strong>the Peircian sense of lack<strong>in</strong>g any motivationalrelationship between the expression and contentpoles of its signs – over 50% of the signs of ASLare judged to be iconic (Woll and Kyle 2004) –but <strong>in</strong> the sense of consist<strong>in</strong>g of conventional signs(presuppos<strong>in</strong>g third-order mentality, see Section5) and systematicity (i.e. <strong>in</strong>ternal relations betweenthe signs). Other <strong>in</strong>stances of post<strong>mimesis</strong>would be emblems like the thumbs-up“OK” sign, or nodd<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stead of say<strong>in</strong>g “yes”,which fulfill the property of conventionality, andat le<strong>as</strong>t a limited form of systematicity.Accord<strong>in</strong>gly, post-mimetic imitation wouldconsist of skills <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the learn<strong>in</strong>g of suchsigns. As po<strong>in</strong>ted out above, some apes thathave been taught a signed language did acquiresome of their signs <strong>in</strong> this manner, though themajority of signs were acquired through mold<strong>in</strong>gof the hands. Even for those that were acquiredby imitation, there may be doubt concern<strong>in</strong>g thedegree of their conventionality and systematicity,e.g. deaf native signers have difficulties <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>gapes’ sign<strong>in</strong>g (P<strong>in</strong>ker 1994).One form of imitation that is clearly symbolic(and hence post-mimetic) is what Tom<strong>as</strong>ello(1999) calls role-reversal imitation: imitation of sign

Zlatev, Persson and Gärdenfors, Lund University Cognitive Science 121, (2005). 13of language, it is not so much the syntax of imitationthat is difficlt for apes, but its semantics. It isconceivable how ape copy<strong>in</strong>g ability, coupledwith a motivation to share one’s mental states(which can, of course, also mean attempt<strong>in</strong>g toimpose one’s view on others), can give rise tomimetic-communicatory <strong>in</strong>teractions, <strong>in</strong> whichlevels of <strong>mimesis</strong> and <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity are closelyconnected, <strong>as</strong> we will argue <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>gsection.5. Mimesis and <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivityWe understand the notion of <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivitybroadly (and rather literally) <strong>as</strong> the shar<strong>in</strong>g andunderstand<strong>in</strong>g of others’ mentality. The term “mentality”is taken here to <strong>in</strong>volve not only beliefs andother forms of conceptual knowledge, but allforms of consciousness, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g emotions,desires, attentional foci and <strong>in</strong>tentions (seeGärdenfors 2003). Not all of these need to beunderstood conceptually, but may <strong>in</strong>volve preconceptual,non-reflective understand<strong>in</strong>g.While the close connection between bodily<strong>mimesis</strong> and imitation discussed above, andgesture (to be analyzed <strong>in</strong> Section 6) is fairlystraightforward, this may not be the c<strong>as</strong>e withrespect to <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity. The re<strong>as</strong>on for thislies, we believe, <strong>in</strong> the dom<strong>in</strong>ant cognitivist viewof mentality <strong>as</strong> consist<strong>in</strong>g entirely (or at le<strong>as</strong>tpredom<strong>in</strong>antly) of propositional representations.In this view, to understand another’s m<strong>in</strong>dwould imply hav<strong>in</strong>g beliefs concern<strong>in</strong>g theirbeliefs. This conception can e<strong>as</strong>ily be framed <strong>as</strong>hav<strong>in</strong>g some sort of <strong>“the</strong>ory of m<strong>in</strong>d” and, <strong>in</strong>deed,this h<strong>as</strong> been the dom<strong>in</strong>ant conception <strong>in</strong>the field (e.g. Baron-Cohen 1995).A great deal of the debate about the <strong>cognitive</strong>abilities of apes h<strong>as</strong> concerned whether or not theyhave a <strong>“the</strong>ory of m<strong>in</strong>d” (Woodruff andPremack 1979; Byrne 1995; Gómez 1994; Heyes1998; Tom<strong>as</strong>ello 1999). Also <strong>in</strong> the discussion of<strong>human</strong> <strong>cognitive</strong> development, the question whenand how children develop one h<strong>as</strong> been a centralfocus of content (Perner et al. 1987; Gopnik andAst<strong>in</strong>gton 1988; Gopnik and Meltzoff 1997;Mitchell 1997).But regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity <strong>as</strong> a <strong>“the</strong>ory”<strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g (primarily) beliefs h<strong>as</strong> had some negativeimplications for understand<strong>in</strong>g this fundamentalsuite of socio-<strong>cognitive</strong> capacities: (a) thequestion is typically posed <strong>as</strong> <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g a discrete,all-or-noth<strong>in</strong>g property: either the child oranimal “h<strong>as</strong> a theory of m<strong>in</strong>d” or doesn’t; (b) therole of one’s own body and actions – and those ofthe other – is m<strong>in</strong>imized, and (c) <strong>“the</strong>oriz<strong>in</strong>g”about the m<strong>in</strong>ds of others (or even oneself) isconsidered prior to act<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> consort with them,giv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity a rather static, detachedquality.Recently, however, these implications havebeen seriously questioned on the b<strong>as</strong>is of bothnew empirical evidence from child developmentand primatology and older philosophical, aboveall phenomenological, <strong>in</strong>sights. With respect to(a) it h<strong>as</strong> become clear that <strong>“the</strong> generic term‘theory of m<strong>in</strong>d’ actually covers a wide range ofprocesses of social cognition” (Tom<strong>as</strong>ello, Calland Hare 2003: 239). Consequently one mustdist<strong>in</strong>guish between these different processes <strong>in</strong>order to understand the <strong>cognitive</strong> capabilities ofanimals, <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> children of different ages. Forexample, Gärdenfors (2003) splits the so-called<strong>“the</strong>ory of m<strong>in</strong>d” <strong>in</strong>to six levels, where the middlefour clearly correspond to different socio<strong>cognitive</strong>capabilities: understand<strong>in</strong>g others’emotions, attention, <strong>in</strong>tentions and beliefs, respectively.Such a division can be complementedwith the hypothesis that the different capabilitiescorrespond to different phylogenetic and ontogeneticstages <strong>in</strong> evolution and development, and<strong>in</strong>deed Gärdenfors (2003) makes this proposal.The criticism concern<strong>in</strong>g (b) and (c) w<strong>as</strong> developedfirst with<strong>in</strong> the phenomenology ofHusserl some one hundred years ago and targetedthe <strong>in</strong>tellectualist perspective on the “understand<strong>in</strong>gof other m<strong>in</strong>ds” (the usual term for<strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity <strong>in</strong> philosophy) <strong>as</strong> a matter of<strong>in</strong>ference or analogy from the knowledge ofone’s own m<strong>in</strong>d. As summarized by a modern<strong>in</strong>terpreter: “For Husserl, understand<strong>in</strong>g anotherperson is not a matter of <strong>in</strong>tellectual <strong>in</strong>ference,but a matter of sensory activations that are unified<strong>in</strong> or by the animate organism or lived bodythat is perceiv<strong>in</strong>g another animate organism.”(Gallagher <strong>in</strong> press).This perspective on <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity w<strong>as</strong> furtherdeveloped by Merleau-Ponty (1962), <strong>in</strong>particular through the notion of the “corporealschema” which serves <strong>as</strong> “a normal means ofknow<strong>in</strong>g other bodies” (Merleau-Ponty 2003:218). More recently, Gallagher (1995, 2005, <strong>in</strong>press) h<strong>as</strong> elaborated the dist<strong>in</strong>ction betweenbody schema and body image where the first is preconsciousand serves <strong>as</strong> a precondition and

14<strong>Bodily</strong> <strong>mimesis</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>“the</strong> <strong>miss<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>l<strong>in</strong>k”</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>human</strong> <strong>cognitive</strong> evolutionbackdrop for <strong>in</strong>tentionality (cf. Searle’s (1992)notion of the Background), while the latter is “a(sometimes conscious) system of perceptions,attitudes, beliefs and dispositions perta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g toone’s own body” (Gallagher 2005: 37). Empiricalneuroscience h<strong>as</strong> recently given support for therole of the body <strong>in</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g others throughmechanisms <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g “mirror neurons” (Rizzolattiet al. 1996; Gallese, Keysers and Rizzolati2004; Arbib <strong>in</strong> press), that mediate between theperception of another and the subject’s ownproprioception and action.With<strong>in</strong> this “embodied” and action-orientedperspective on the understand<strong>in</strong>g of otherm<strong>in</strong>ds, unlike <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>tellectualist cognitivistone, bodily <strong>mimesis</strong> becomes clearly relevant.With respect to dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g different levels of<strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity, we can apply the <strong>mimesis</strong> hierarchydef<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Section 3 to yield a possibleevolutionary and developmental hierarchy of<strong>in</strong>tersubjectivitity.It should be noted that this way of “splitt<strong>in</strong>gthe theory of m<strong>in</strong>d” is different from that proposedby Gärdenfors (2003) s<strong>in</strong>ce the differentcapabilities dist<strong>in</strong>guished by the Gärdenfors(understand<strong>in</strong>g emotion, attention, <strong>in</strong>tention andbelief) are <strong>in</strong> a sense orthogonal to the <strong>mimesis</strong>hierarchy. For example, the understand<strong>in</strong>g ofothers’ emotions occurs on each one of the levelsof the <strong>mimesis</strong> hierarchy, with <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>cognitive</strong> complexity. However, if we considerwhat may be regarded <strong>as</strong> a typical manifestation ofthe respective capability (emotion, attention and<strong>in</strong>tention), there turns out to be considerableoverlap between the levels of <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivitydef<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> this article and those of Gärdenfors(2003): Emotion can be shared on a protomimeticlevel, shar<strong>in</strong>g attention <strong>in</strong>volves (atle<strong>as</strong>t) dyadic <strong>mimesis</strong>, understand<strong>in</strong>g communicative<strong>in</strong>tentions is centrally implicated <strong>in</strong> triadic<strong>mimesis</strong> (but “simple” <strong>in</strong>tentions are understooddyadically), and understand<strong>in</strong>g beliefs appears torequire explicit symbolic skills, which can beargued to be post-mimetic s<strong>in</strong>ce they depend onlanguage (see Section 5.4).A central question <strong>in</strong> relat<strong>in</strong>g the proposed<strong>mimesis</strong> hierarchy and <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity iswhether the respective <strong>mimesis</strong> level serves <strong>as</strong> aprecondition and a causal factor for the developmentof correspond<strong>in</strong>g skills of <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity. Or isit rather that <strong>in</strong>dependently reached <strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>tothe m<strong>in</strong>d of others makes <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>gly complexforms of <strong>mimesis</strong> possible? Our general Vygotskyanapproach suggests the first scenario:bodily <strong>mimesis</strong> is a fundamentally <strong>in</strong>terpersonalactivity that exercises (<strong>in</strong> ontogeny) and providesselection pressures (<strong>in</strong> phylogeny) for develop<strong>in</strong>gmore ref<strong>in</strong>ed skills <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d read<strong>in</strong>g. Thus, ourpredom<strong>in</strong>ant take is that <strong>mimesis</strong> drives <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivityrather than the other way around.At the same time we acknowledge that the “driv<strong>in</strong>g”metaphor is not completely adequate s<strong>in</strong>cethe causality runs <strong>in</strong> both ways and is possiblybest described <strong>in</strong> terms of co-evolution. We willreturn to this issue <strong>in</strong> the summary at the end ofthis section.5.1 Proto-mimetic <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivityGiven our def<strong>in</strong>ition of bodily <strong>mimesis</strong> we canregard some of the most b<strong>as</strong>ic forms of <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity<strong>as</strong> “proto-mimetic” to the extentthat they (a) consist of forms of <strong>in</strong>terpersonal<strong>in</strong>teraction that <strong>in</strong>volve cross-modal mapp<strong>in</strong>gbetween proprioception and the (visual) perceptionof others, (b) do not fulfill either one of thecharacteristics volition and representation. This canbe made more precise us<strong>in</strong>g the dist<strong>in</strong>ction madeby Gallagher (1995, 2005) between body schemaand body image. The first is characterized <strong>as</strong> “<strong>as</strong>ystem of sensory-motor processes that constantlyregulate posture and movement – processesthat function without reflective awarenessor the necessity of perceptual monitor<strong>in</strong>g” (Gallagher2005: 37-38). The second is, <strong>as</strong> po<strong>in</strong>tedout, “a (sometimes conscious) system of perceptions,attitudes, beliefs and dispositions perta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gto one’s own body” (Gallagher 2005: 37).Given these def<strong>in</strong>itions, we can state that acts ofproto-<strong>mimesis</strong> <strong>in</strong>volve (above all) the body schema,which is largely <strong>in</strong>nate (<strong>in</strong> the sense of be<strong>in</strong>gpresent at birth) and pre-conscious, rather thanthe body image, which is gradually constructedwith experience and is accessible to consciousness.Furthermore, the forms of <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivitydescribed here do not require a conceptual differentiationbetween self and other, which isnecessary for establish<strong>in</strong>g a correspondencerelation between them, i.e. what we refer <strong>in</strong> ourdef<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>as</strong> representation. This is not to say thatthe young <strong>in</strong>fant lives <strong>in</strong> a completely undifferentiatedworld <strong>in</strong> which there is no awareness ofself whatsoever, <strong>as</strong> <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>as</strong>sical accounts of <strong>in</strong>fantcognition (e.g. James 1890). Nevertheless, even a

Zlatev, Persson and Gärdenfors, Lund University Cognitive Science 121, (2005). 15modern developmental psychologist who emph<strong>as</strong>izesthe role of awareness of others’ attentionand the presence of affective selfconsciousness<strong>in</strong> the first months of life po<strong>in</strong>tsout that “older <strong>in</strong>fants reveal a greater focus onthe self and the younger ones reveal a more immersed,less detached focus on the other” (Reddy2003: 401). This “more immersed, less detached”quality of the earliest forms of <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivitysupports our cl<strong>as</strong>sification of them <strong>as</strong>proto-mimetic.Can this analysis be extended to the (early)<strong>in</strong>terpersonal relations among apes? As po<strong>in</strong>tedout <strong>in</strong> Section 4.3 “neonatal mirror<strong>in</strong>g” h<strong>as</strong> alsobeen observed <strong>in</strong> apes (though this h<strong>as</strong> so faronly be attested with <strong>human</strong>, rather than apefaces <strong>as</strong> stimuli). S<strong>in</strong>ce this is typically attributedto a form of identification with the person imitated,serv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>as</strong> a b<strong>as</strong>is for <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivitywhen children are concerned (Meltzoff andGopnik 1993; Gallagher 2005), it can be viewed<strong>as</strong> evidence that at le<strong>as</strong>t apes, and possibly othermammals too, have such b<strong>as</strong>ic proto-mimetic<strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity. The function of such “mirror<strong>in</strong>g”can be related to what is possibly the mostb<strong>as</strong>ic form of <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity, both ontogeneticallyand phylogenetically: the ability to shareemotions, or empathy (E<strong>in</strong>fühlung). As a protomimetic,non-representational capacity, this istestified <strong>in</strong> early <strong>in</strong>fancy and sometimes referredto <strong>as</strong> <strong>in</strong>teraffectivity (Stern 2001). The well-knownexperiments described by Trevarthen (1992)show that parent-<strong>in</strong>fant <strong>in</strong>teractions <strong>in</strong> the firstfew months take the form of a reciprocal rhythmic“dance”, and that frustration follows if this“attunement” is disrupted (notice the musicalmetaphors). The suggestion is that emotionssuch <strong>as</strong> joy and suffer<strong>in</strong>g are perceived directly,possibly <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g mirror-neuron structuressimilar to those <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> action recognitionand imitation, rather than <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ferences tounderly<strong>in</strong>g states (Gallese, Keysers and Rizzolati2004).Preston and de Waal (2002) have argued persu<strong>as</strong>ivelythat <strong>as</strong> a b<strong>as</strong>ic mechanism <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g thel<strong>in</strong>kage of perception and action, a b<strong>as</strong>ic form ofempathy is available to most if not all mammalspecies. Def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g empathy <strong>as</strong> “any processwhere the attended perception of the object’sstate generates a state <strong>in</strong> the subject that is moreapplicable to the object’s state or situation thanto the subject’s own prior state or situation”(ibid: 4), they see a clear evolutionary motivationfor its emergence <strong>in</strong> the ability to recognize andunderstand the behavior of con-specifics. It is anopen question how much of such match<strong>in</strong>g betweenthe visually perceived body of the otherand the proprioceptively perceived body of oneselfis doma<strong>in</strong>-general – and thus can be expectedto be general across species – and howmuch is specialized <strong>in</strong> the form of speciesspecificcommunicative signals such <strong>as</strong> facialexpressions. It is characteristic that such signals,such <strong>as</strong> the famous “play-face” expression ofgreat apes (an evolutionary precursor to the<strong>human</strong> smile) typically carry emotional ratherthan referential mean<strong>in</strong>g.A second socio-<strong>cognitive</strong> skill that relates to<strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity and appears to have a protomimeticorig<strong>in</strong>, at le<strong>as</strong>t <strong>in</strong> <strong>human</strong> children, isattention. Reddy (2001, 2003, 2005) h<strong>as</strong> arguedthat prior to awareness of the other’s attentionto an external object and much prior to jo<strong>in</strong>tattention appear<strong>in</strong>g around 12 months (see below),children “show an awareness of others <strong>as</strong>attend<strong>in</strong>g be<strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> an awareness of self<strong>as</strong> an object of others’ attention” (Reddy 2003:357), displayed <strong>in</strong> phenomena such <strong>as</strong> eyecontact,<strong>in</strong>tense smil<strong>in</strong>g, coyness, ‘call<strong>in</strong>g’ vocalizations,show<strong>in</strong>g-off etc. S<strong>in</strong>ce awareness of self(at this stage) is largely proprioceptive, whileawareness of the attention of others (<strong>in</strong> see<strong>in</strong>gchildren) is mostly b<strong>as</strong>ed on vision, this satisfiesour first criterion for bodily <strong>mimesis</strong>. Reddy’sclaim is that such dyadic (though not dyadicmimetic)<strong>in</strong>teractions underp<strong>in</strong> later developments<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity. Evidence for this is the observationthat autistic children show difficultieseven with such simple <strong>in</strong>terpersonal engagements,“suggest<strong>in</strong>g that whatever is go<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>in</strong>dyadic attentional engagements may <strong>in</strong>deed becritical, not just <strong>as</strong> a source of <strong>in</strong>formation andexperience about attentional behavior, or <strong>as</strong> <strong>as</strong>caffold for the subsequent development ofawareness of attention, but also <strong>as</strong> evidence ofawareness of attention” (Reddy 2005: 95).Until recently it h<strong>as</strong> not been clear whethersuch awareness of another’s attention exists <strong>in</strong>the <strong>in</strong>teraction between <strong>in</strong>fant apes and theirmothers, but <strong>in</strong> a recent study, Bard et al. (<strong>in</strong>press) report that the rates of mutual gaze between<strong>in</strong>fants and their mothers are virtually thesame <strong>in</strong> 3-month old <strong>human</strong> children and 3-month old chimpanzees; 18-20 and 17 times perhour, respectively (though <strong>human</strong>s tend to engage<strong>in</strong> longer bouts of mutual gaze). Further-

16<strong>Bodily</strong> <strong>mimesis</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>“the</strong> <strong>miss<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>l<strong>in</strong>k”</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>human</strong> <strong>cognitive</strong> evolutionmore, the authors noticed a “cultural” differencebetween the apes at Primate Research Institute,Japan and those at Yerkes National PrimateResearch Center, USA, with the ones <strong>in</strong> Japanengag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> mutual gaze at much higher rates (22vs. 12 times per hour), while the ape mothers <strong>in</strong>the USA cradled their <strong>in</strong>fants more often (71% vs.40% of the total time). Intrigu<strong>in</strong>gly, a similar<strong>in</strong>verse correlation between visual and tactilecontact h<strong>as</strong> been observed <strong>in</strong> <strong>human</strong> societies,with traditional cultures favor<strong>in</strong>g touch andWestern ones gaze: “With reduced physical contactfound <strong>in</strong> Western societies, mutual engagementshifts to the visual system, arguably a moreevolutionarily derived pattern” (Bard et al. <strong>in</strong>press). S<strong>in</strong>ce apes do not seem to differ from<strong>human</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the capacity to perform this shift (andpossibly even transmit it culturally to their descendents),this confirms the conclusions fromneonatal imitation that there is no major differencebetween the species on the proto-mimeticlevel.5.2 Dyadic mimetic <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivityIn our previous discussion, we proposed thatproto-mimetic <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity, without a cleardifferentiation between self and other is b<strong>as</strong>edon the (mostly) unattended body schema andsimilarly unattended mechanisms for “bodycopy<strong>in</strong>g”. On the other hand, what we here referto <strong>as</strong> dyadic mimetic <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity is b<strong>as</strong>ed on theconscious control of the movements of one’sbody and attention to their correspondence tothe body of another, whereby one can imag<strong>in</strong>ewhat the other experiences on the b<strong>as</strong>is of one’sown experiences <strong>in</strong> similar circumstances. In theterm<strong>in</strong>ology of Gallagher (1995, 2005), we proposethat the role that bodily <strong>mimesis</strong> properplays for the development of <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivityimplies not the body schema but the body image.While the body schema and the body imagenormally <strong>in</strong>teract, Gallagher (2005) shows how<strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> pathologies they can be dis<strong>as</strong>sociated.The dist<strong>in</strong>ction between the dyadic form ofmimetic <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity, described here, and thetriadic one described <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g sub-sectionis that while the dyadic form <strong>in</strong>volves the propertiesof volition and representation (see Section3), e.g. <strong>in</strong> the c<strong>as</strong>e of recogniz<strong>in</strong>g oneself <strong>in</strong> amirror or <strong>in</strong> shared attention, there is no understand<strong>in</strong>gof communicative sign function. Thus thereis no b<strong>as</strong>is for <strong>in</strong>tentional communication on theb<strong>as</strong>is of shared representations. As we shall seehere and <strong>in</strong> the discussion of ape gestures <strong>in</strong>Section 6, it is the latter that appears to be mostdifficult for non-<strong>human</strong> primates. Below, webriefly describe how understand<strong>in</strong>g others’ emotions,attention and <strong>in</strong>tentions can be seen <strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>timately related to dyadic <strong>mimesis</strong>.Where<strong>as</strong> (simple) empathy is proto-mimetic,what Preston and de Waal (2002) call <strong>cognitive</strong>empathy requires a differentiation between subjectand object where <strong>“the</strong> subject is thought to useperspective-tak<strong>in</strong>g processes to imag<strong>in</strong>e or project<strong>in</strong>to the place of the object” (ibid: 18). Evidencethat this is not an isolated phenomenon,but shows a more advanced level of <strong>in</strong>tentionalityis the fact that <strong>cognitive</strong> empathy “appears toemerge developmentally and phylogeneticallywith other ‘markers of m<strong>in</strong>d’ … <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g perspectivetak<strong>in</strong>g …, mirror self-recognition …,deception, and tool-use.” (ibid: 18). Researchconcern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>cognitive</strong> empathy <strong>in</strong> apes h<strong>as</strong> focusedon their consolation behavior, which iswell attested <strong>in</strong> at le<strong>as</strong>t chimpanzees, but h<strong>as</strong> notbeen found <strong>in</strong> monkey species (de Waal andAureli 1996) or any other mammalian species.Consolation is <strong>cognitive</strong>ly more complex thansimple empathy s<strong>in</strong>ce the consol<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividualnot only feels that somebody else experiences anegative emotion, but also <strong>in</strong>tends to help relievethis, imply<strong>in</strong>g an ability to imag<strong>in</strong>e the morepositive emotional state. 3This supports the <strong>in</strong>terpretation that <strong>cognitive</strong>empathy <strong>in</strong>volves a more sophisticated representationalcapacity than what is necessary forsimple empathy. S<strong>in</strong>ce dyadic <strong>mimesis</strong> <strong>in</strong>volvesboth the ability to identify with the other, and atthe same time to differentiate between self andother, our (Vygotskyan) hypothesis is that it isdyadic <strong>mimesis</strong>, implicated <strong>in</strong> e.g. imitation (Section4) that scaffolds the development of suchrepresentational capacity.S<strong>in</strong>ce dyadic <strong>mimesis</strong> allows to “place oneself<strong>in</strong> the shoes of others”, it also gives the oppor-3 An <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g question is what goes on <strong>in</strong> them<strong>in</strong>d of an ape that is be<strong>in</strong>g consoled: If one couldidentify <strong>cognitive</strong> processes of the form “I can feelthat you feel that I feel bad”, this would be equivalentto “third order emotion”. However, given thelack of methodology for test<strong>in</strong>g the existence ofsuch a process, we feel compelled to apply Occam’srazor and <strong>as</strong>cribe only second order emotionsof the form “I feel that you feel”.