PRACTICEUrban planning in IndiaFrom token inclusion totransformative participationAlthough labelled ‘participatory’ many urban planningprocesses in India involve only select elite groups. This articleexplains what is required to achieve genuine participationinvolving all stakeholders, including the poor and themarginalised.Kanak Tiwarikanak@pria.<strong>org</strong>Programme Manager at PRIA Global PartnershipKaustuv Kanti Bandyopadhyaykaustuv@pria.<strong>org</strong>Director of PRIA Global PartnershipIndian cities are chaos personified - vastheterogeneous conurbations whereindividuals and groups represent all shades ofeconomic, social, religious, cultural andprofessional identities. The fast pace ofurbanisation often leads to impromptu andthoughtless expansion, with littleconsideration given to basic services such aswater, sanitation and roads. Inclusive andparticipative city planning can be challengingto achieve; but it offers an ideal opportunityto implement processes that make planningresponsive to the needs of <strong>multi</strong>plestakeholders, with particular focus on poorand marginalised members of society.Embedding citizen participation in cityplanning is problematic because of the sheerscale of cities, the wide gaps in knowledgeand power between stakeholders, the lack oftechnical expertise and the prevalence ofpolitical patronage that favours elites.Traditionally, expert-driven planningprocesses have been so entrenched that therewas hardly any space for the poor andmarginalised to participate. In addition, thelack of updated data, weak local governmentsand political resistance to participatoryprocesses has widened the schism betweencitizens and city plans.Recently, the idea of participatory planninghas become rather fashionable. Projects led byboth government and private developers useterms such as ‘stakeholder consultation’ and‘people-friendly plan’ in their project briefs.But the reality of participatory planning isthat it tends to be limited to meetings with afew elite groups, where city issues arediscussed – and then the professionals takethe decisions on any future development.Sadly, such tokenism means that people’scontrol over decision making remains elusive.This will continue to be the case as long asprofessionals involved in the project receiveno training for facilitating meaningfulparticipation in highly fragmented societies,and as long as <strong>multi</strong>ple stakeholders andinterest groups including women, children,youth, the elderly and other marginalisedpeople are excluded from consultations.The greatest need is to facilitate citizens’involvement in the planning of their citiesand localities, and to transform theircontribution from mere nominal orconsultative participation into instrumentaland transformative participation.The Society for Participatory Research inAsia (PRIA) is one of the very few civilsociety <strong>org</strong>anisations in India that takes adifferent approach to city planning. Over thecourse of the past twelve years, we haveattempted to transform rigid planningprocesses into processes that are more peoplefriendly, flexible and inclusive. In this articlewe will share the lessons we have learned.More specifically, we will describe theexperiences we had preparing participatorycity development plans for two small townsand how we helped institutionalise socialaccountability mechanisms in five cities– four of which are state capitals.For PRIA, it is a given that urban planningis a participatory process. Staff are trained toreinforce this perspective in the way theyengage with the elected representatives. Whenpreparing the participatory developmentplans, PRIA held workshops for stakeholdersto help clarify the political and developmentalimportance of the planning process.Discussions held after the workshopsreinforced the view that the councillors andthe citizens together are the initiators andowners of the planning process.After the workshops and preliminarydiscussions, PRIA <strong>org</strong>anised citywidecampaigns to ensure that as many people aspossible knew about the development plans.This was an essential step in creating anenabling environment for a <strong>multi</strong>-stakeholderprocess to succeed. It meant clarifyinginformation that was often skewed, sensitisingthe ‘upper classes’ to the negativeconsequences of perpetuating existinginequalities and giving confidence tomarginalised groups and individuals.The next stage was to jointly analyse thecurrent situation to see what <strong>change</strong>s neededto be made to achieve the desired result. Allthe stakeholders contributed to this. However,it was necessary to limit the influence of someof the professional groups such as localacademic institutions, media groups, andvarious professional and businessassociations. Such stakeholders can contributeenormously to making the planning processan open and transparent ‘public deliberation’,but they need to modify their expectations toensure that the poor and marginalised canstill lead the process, or at least participate ina meaningful way.The PRIA facilitators then collated all theinformation, presented it to the stakeholders,and asked for validation and feedback.Everyone’s comments were incorporated andthe final plan was prepared and submitted tothe municipality. From that point onwards itwas mainly up to the municipality tomaintain the momentum and commitmentsof the various stakeholders. However, giventhe current resource-starved nature of localgovernments in India, it may not be possiblefor institutions to implement the plans intheir totality.The lessons we learnedThe demand and supply side ofaccountabilityParticipation requires a two-way processbetween citizens who demand accountability,better services and a defining role in decisionmaking, and a local government thatacknowledges the equal importance of allstakeholders and responds appropriately andtransparently. Facilitators must placethemselves as an interface between the14 <strong>Capacity</strong>.<strong>org</strong> Issue 41 | December 2010

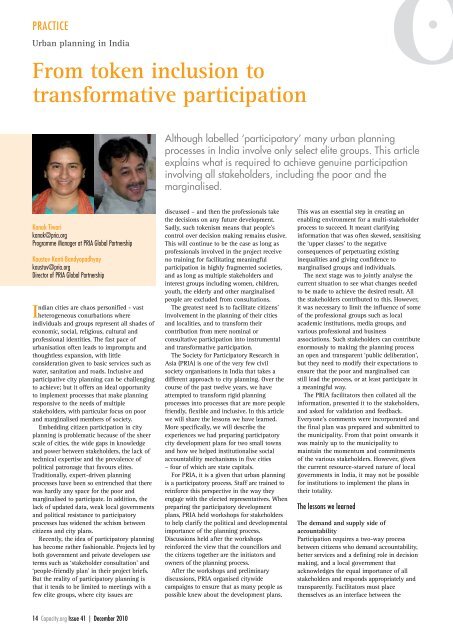

‘supply’ and ‘demand’ sides of the process.(This is easier said than done, particularlywhen the facilitator is a pro-poor, civil society<strong>actor</strong> aware of skewed power relationshipsthat favour elitist governance structures.)In earlier projects, citizens had beenencouraged to participate but it was soonclear that amplifying the voice of the citizenswould have little effect if nobody waslistening. Learning this helped us to bridgethe rift between supply and demand. A veryinteresting example of this was support forthe creation of systems to redress grievancesin some municipalities. The citizens wereencouraged to flood the municipality withservice-related complaints. Simultaneously,the municipal officials and electedrepresentatives were sensitised and given thecapacity to respond by making strategic<strong>change</strong>s in their complaints systems. Even themost advanced complaints redressal systemsbecome defunct if citizens do not use them,while municipalities would never realise theimportance of social accountabilitymechanisms unless there was a demand.The importance of inclusivenessEnhancing capacity and promotingknowledge ex<strong>change</strong> are crucial. Facilitatorsmust be present on site throughout the courseof the intervention and they must f<strong>org</strong>erelationships with local civil society groupsand citizens’ <strong>org</strong>anisations. The ex<strong>change</strong> ofknowledge allows local people to give theirperspectives on issues related to the socioeconomic,cultural and planning aspects ofthe city. Facilitators must make sure that theyinform the citizens and local partners aboutall relevant policies, schemes andentitlements, and that they present thetechnicalities of planning in an accessibleway using local languages. It is essential to beaware of and use existing social networkssuch as religious groups and neighbourhoodgroups, as well as professional associationssuch as colleges, trades associations andchambers of commerce to expand thestakeholder base to include the entire city.Then knowledge and ideas can really begenerated from different fields.Including womenWomen are the real agents of <strong>change</strong> becausethey are the best representatives of many ofthe silent and marginalised groups. Womenhave higher hopes that, with the help ofexternal support, their efforts could makethings better – and they tend to be free oflocal political allegiances. Instead of beinghighly critical, they <strong>org</strong>anise themselves andget things done. In the cities of Raipur andRanchi, women <strong>org</strong>anised themselves intoneighbourhood groups and demanded publictaps, toilets and dustbins – and they got them.However, this was not the case in thesmall towns we worked in, where womenwere reticent about coming out into thepublic domain. It took months before agender balance could be achieved incommunity meetings. In these cases, it wasWomen collect their daily water ration from a new community tap in Mumbai, Indiaimportant to emphasise that they shouldparticipate actively (merely being there wasnot enough) and recognise that they hadimportant issues to share. It was interestingto observe that while men contributed tophysical infrastructure issues, women, whenthey started speaking, shared insights intoissues such as the lack of higher educationinstitutes, which caused their children to goaway; or the absence of street lights, whichrestricted their mobility. They spoke too ofthe dearth of maternal care centres, and toldmany stories of women having their babieswhile travelling to distant clinics.Do not discard technical expertiseTechnical expertise that is on the side of thepoor and marginalised <strong>change</strong>s the powerequation. It is important that developmentprofessionals respect technical expertisebecause they expect technical experts to acceptthe necessity of participatory processes. It isimportant that architects, planners, urbandesigners and other experts interact directlywith the people. Certainly, there is a need toplace participatory planning in collegecurriculums, but it is even more important thatit is instilled into the psyches of the technicalexperts. A good illustration of this is the storyof a community that was demanding a waterpipeline in their area, but the municipality wasasking them to shift to another area if theywanted better services. It escalated into a hugemisunderstanding with the people in thecommunity feeling very mistrustful of the localgovernment. The problem arose because thesettlement was partially situated on hard rockthrough which water pipelines could not bedrilled. A planner and geologist intervened, acompromise solution was reached and in-situresettlement was carried out to make wateravailable for every family.Technical expertise can also be useful inassessing the priority of people’s needs andexplaining about the equitable distributionof limited resources. For example, peoplefrom better-off economic backgroundssometimes suggest planning ideas forAlamy / India imagesairports and shopping malls when their townstill lacks proper basic services such as waterand sanitation.Small achievementsSmall achievements sow the seeds of hugesuccesses. Getting a small tap installed orrehabilitating one slum settlement proves tothe people that efforts yield results. Suchvictories build trust and enthusiasm andencourage more people to participate. Theyalso enhance the quality of participationconsiderably once people realise that theirefforts can make a difference.Small successes are also important for thelocal governments to showcase theirwillingness to become responsive. This isespecially so in political environments wherethe devolution of resources and power arestill very much the gift of the higherechelons of government.Access to informationInformation and knowledge are power – andgiving the poor and marginalised access tothem leads to their empowerment. Historically,information about policies, planning standards,the provision of services and entitlements todevelopment resources was largely inaccessibleto the marginalised majority – and even whenit was made available, it was presented inincomprehensible language that rendered itinaccessible. One of the roles of facilitators isto decode such planning jargon, not only forthe common citizens but also for electedrepresentatives. Equipped with the rightinformation and analysis, people can start totake charge of interventions and producesustainable solutions.But if they are to move beyond pilotprojects to schemes with larger coverage andgreater impact, they must have the support ofnational and district governments; as onlygovernments can provide the huge resourcesneeded for the next step.