The ICL Inquiry Report

The ICL Inquiry Report

The ICL Inquiry Report

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>ICL</strong> <strong>Inquiry</strong>HC 838

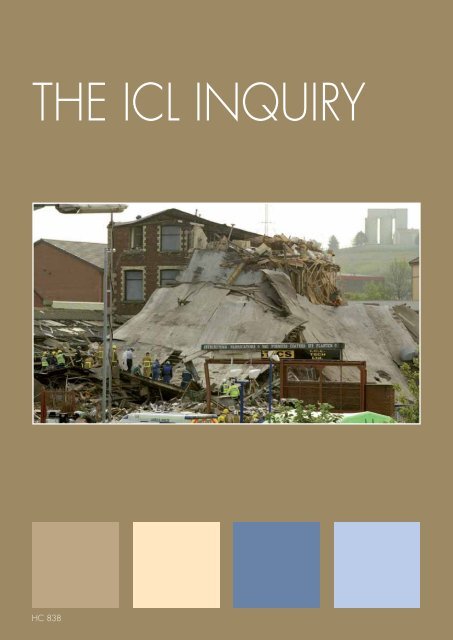

<strong>The</strong> <strong>ICL</strong> <strong>Inquiry</strong> <strong>Report</strong>Explosion at Grovepark Mills, Maryhill, Glasgow11 May 2004Presented to the House of Commons and the Scottish Parliament under S26 Inquiries Act 2005Presented to the House of Lords by Command of Her MajestyOrdered by the House of Commons to be printed on16 July 2009Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish MinistersJuly 2009HC 838 Edinburgh: THE STATIONERY OFFICE £34.55SG/2009/129

© Crown Copyright 2009<strong>The</strong> text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free ofcharge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. <strong>The</strong> materialmust be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified.Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holdersconcerned.For any other use of this material please write to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew,Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or e-mail: licensing@opsi.gov.ukISBN: 9780102952247

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTIntroduction by the Right HonourableLord Gill, Chairman of the <strong>Inquiry</strong><strong>The</strong> tragedy that occurred at Grovepark Mills on11 May 2004 has blighted the lives of manypeople. My purpose in this <strong>Inquiry</strong> has been tofulfill my Terms of Reference, which are set outbelow, and to make proposals for a new safetyregime for LPG installations that will minimise therisk that such an event will be repeated.Terms of Reference• To inquire into the circumstances leadingup to the incident on 11 May 2004 atthe premises occupied by the <strong>ICL</strong> groupof companies, Grovepark Mills, Maryhill,Glasgow.• To consider the safety and related issuesarising from such an inquiry, including theregulation of the activities at Grovepark Mills.• To make recommendations in the light of thelessons identified from the causation andcircumstances leading up to the incident.• To report as soon as practicable.This is the first joint inquiry to be held underthe Inquiries Act 2005 (the 2005 Act) and thefirst to be conducted under the the Inquiries(Scotland) Rules 2007 (SSI 2007 No 560) (the2007 Rules). <strong>The</strong> 2005 Act has introduceda new framework for public inquiries that willgreatly increase the efficiency with whichthey are conducted without compromising thethoroughness of the process. <strong>The</strong> essence of thisapproach is that inquiries will be inquisitorialprocesses, in which the relevant questions willbe determined by the inquiry, rather than theadversarial, litigation-based processes typicalof major inquiries in the past in which theinquiry agenda has been set by the participantsthemselves. In this new approach, there is noreason to fear that the truth-finding process willbe compromised. On the contrary, there is everyreason to think that it will be enhanced.I hope that this <strong>Inquiry</strong> has demonstrated thestrengths of the new procedures.Since this has been the first joint inquiry underthe new procedures and since it has been thefirst of its kind to be held in Scotland, I have setout the history of the <strong>Inquiry</strong> in Appendix 4 tothis <strong>Report</strong>. I hope that this history will be helpfulto those who have to conduct similar inquiries ofthis kind.I am grateful to the <strong>Inquiry</strong> Team who collectedand analysed a mass of evidence quickly,organized the inquiry hearings efficiently and,above all, assisted the core participants at everystage.I am grateful too to counsel to the <strong>Inquiry</strong>, both ofthem outstanding lawyers, for the benefit of theirskill and experience; and to the core participantsand their representatives for the help that theyhave given me in fulfilling my terms of reference.Lastly, I am grateful to the staff of the MaryhillCommunity Central Hall for their unfailing helpthroughout the <strong>Inquiry</strong> hearings.This was an avoidable tragedy. My <strong>Inquiry</strong> hasexamined its causes and considered how the riskof a similar tragedy can be minimised. I hopethat my recommendations will put LPG safety ona new footing: But I am conscious that progressin LPG safety will have been achieved at greatcost to the victims of this disaster and theirfamilies. I extend to the families of the deceasedand to those who were injured my heartfeltsympathy.Brian GillJuly 2009iii

CONTENTSPart 1 1Chapter 1 – <strong>The</strong> explosion, the rescue operation and the victims 2Chapter 2 – <strong>The</strong> cause of the explosion and its effects 4Chapter 3 – <strong>The</strong> prosecution 7Part 2 9Chapter 4 – Liquefied petroleum gas 10Chapter 5 – LPG installations 12Chapter 6 – <strong>The</strong> LPG industry 25Part 3 27Chapter 7 – <strong>The</strong> regulatory system 28Part 4 31Chapter 8 – <strong>The</strong> <strong>ICL</strong> group of companies 32Part 5 35Chapter 9 – <strong>The</strong> history and the layout of the Grovepark Mills site 36Chapter 10 – Calor and Johnston Oils and the installation at the site 39Chapter 11 – <strong>The</strong> installation of the LPG tank and external pipework 44Part 6 51Chapter 12 – A narrative account of the involvement of HSE at Grovepark Mills 52Chapter 13 – <strong>ICL</strong> and risk assessments 79Chapter 14 – <strong>The</strong> approach to LPG safety at Grovepark Mills 85Part 7 105Chapter 15 – What caused the disaster 106Part 8 111Chapter 16 – <strong>The</strong> responses of HSE and of the industry in the aftermath of the disaster 112iv

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTPart 9 119Chapter 17 – LPG safety: an overview 120Chapter 18 – <strong>The</strong> action plan 130Appendices 147Appendix 1 – List of core participants 148Appendix 2 – List of witnesses before the <strong>Inquiry</strong> 149Appendix 3 – Chronology of legislation, regulations, codes of practice and guidance 152Appendix 4 – <strong>The</strong> history of the <strong>Inquiry</strong> 164Appendix 5 – <strong>The</strong> <strong>ICL</strong> <strong>Inquiry</strong> Team 178Appendix 6 – Definitions and glossary 179v

<strong>The</strong> deceasedMargaret BrownlieAnnette DoylePeter FergusonThomas McAulayJames Stewart McCollTracey McErlaneKenneth MurrayTimothy SmithAnn Trench<strong>The</strong> injured survivorsJames AitkenWilliam AitkenheadGordon BellAlan ByrneAlan DonaldsonNicholas DownieNicole EagleshamStacey EagleshamMonica FlynnDaniel FraserAndrew GallowayWilliam GiffordDaniel GilmourDavid HamiltonMartin HamiltonCharlene HowarthDerek KingLinda KinnonArchibald LindsayElizabeth LogieSheena McColl (now O’Brien)Christopher McGinleyJames McGoldrickMaureen McPhailClaire McShaneWilliam MastertonIan MaversElizabeth MillsTammy NelsonChristopher ProvanCharles RobertsonJohn TurnerMatthew WylieThose exposed to the risk of death or injuryJames AndersonDavid AndrewsJames BaxterWilliam ChapmanPatrick FeggansDavid FordeLinda JohnstonRobert McMillanAnthony NorthcoteJoyce RussellJason StewartRobert Warrenvi

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTPart 11

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTIncident Commander had declared a MajorIncident, had put in place arrangements for coordinatingthe rescue effort and had establishedsecurity cordons. By 1.00 pm, the SouthernGeneral Hospital Mobile Medical Team wason site. Soon after, Assistant Firemaster WilliamMcDonagh took command of the rescueoperation. At first, there were five fire crews.Fourteen more were called in. <strong>The</strong> medicalteams established a triage procedure andhad the injured taken to various hospitals inthe Glasgow area. By mid-afternoon, twentyfour casualties had been removed to hospital,sixteen persons were believed to be still buriedin the rubble and the rescuers were in contactwith five persons who were trapped. At 9 pmthe last survivor was rescued. By the end of theday, there were thirty seven known casualtiesand six fatalities.the rescue operation. This was an occasionwhen ordinary people did extraordinary acts.Hundreds of emergency service personnelfrom across the United Kingdom offered help,including the members of specialist rescueteams throughout Scotland and the north ofEngland. Over the next three days the bodiesof the deceased were recovered. <strong>The</strong> last wasremoved from the site at 11.25 am on 14 May.At the end of the rescue phase, the Fire andRescue Service gave control of the scene to thePolice.<strong>The</strong> members of the emergency serviceswho attended the scene showed ourstandingprofessionalism and dedication. <strong>The</strong>yworked tirelessly in difficult and harrowingcircumstances. <strong>The</strong> staff of the nearbyCommunity Central Hall in Maryhill providedsupport and refuge to the relatives andfriends of the casualties in the difficult hoursimmediately after the disaster and throughout3

PART 21at the lowest point. It can permeate throughsubterranean structures. Its exact route could notbe determined with certainty in this case.When the pipe was excavated, it wasdiscovered that when the level of the yard hadbeen raised, the section of the pipe in whichthe main leak occurred had been packedaround with loose fill material. Beneath thesurface hard-standing a large concrete slabrested on top of the pipe where it turned andentered the building. <strong>The</strong> main leak at the finalbend had been caused by external corrosionaggravated by the weight of the piece ofconcrete that rested on it.<strong>The</strong> leak developed in three stages: there wasinitial corrosion, then a combination of loadingand corrosion which accelerated the failure,and a final opening of the crack because ofits weakened state. <strong>The</strong> rate of release of LPGwould have increased during the final stage. Itwas not possible to determine for how long thegas had been leaking into the basement.aggressive’ in respect of their corrosivequalities, and the rubble in-fill containedlarge pieces of concrete that had beenbearing directly on the undergroundpipework;5. there was a further small leak in the sectionof the pipework that was situated aboutone-third of the distance from the tank to thebasement. It resulted from perforation byexternal corrosion.<strong>The</strong>re was LPG in the soil around the pipe trackin a pattern consistent with leakage from theunderground pipework before the explosion.<strong>The</strong> possibility that the explosive atmosphereresulted from any other potential source, suchas natural gas, dust or ground methane can beexcluded completely.Further examination of the pipe showed that1. the steel pipework had originally beengalvanised but otherwise had no othercorrosion protection;2. the screwed malleable iron fittings, straightcouplings, bends and elbows joininglengths of pipework were, with oneexception at the tank end, ungalvanisedand had no other corrosion protection;3. the pipe lengths and fittings weresubstantially corroded, with a significantreduction in wall thickness in the pipeworkoverall;4. the material used to form and fill thepipe track comprised a range of soiltypes classified as ‘aggressive’ to ‘very6

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTChapter 3 – <strong>The</strong> prosecutionIn the week after the explosion the then LordAdvocate announced that the Health andSafety Executive (HSE) and Strathclyde Policewould conduct a joint investigation and reportto the Procurator Fiscal. On completion of theinvestigation, the need for a Fatal Accident<strong>Inquiry</strong> or for any other form of public inquirywould be considered.had been caused by the leakage of LPG froma corroded underground pipe that connectedan above-ground LPG storage tank to an ovenwithin the premises.On 28 August 2007, <strong>ICL</strong> Tech and <strong>ICL</strong> Plasticswere each fined £200,000.In November 2006 the Crown took proceedingson indictment against <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics Limited and <strong>ICL</strong>Tech Limited under section 33(1)(a) of the Healthand Safety at Work etc. Act 1974.<strong>The</strong> charges alleged inter alia that therehad been failures (1) to make a suitable andsufficient assessment of the risks to the healthand safety of employees while at work infailing to identify that the pipework conveyingLiquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) from the bulkvessel storage to the premises presenteda potential hazard and risk; (2) to appointone or more competent persons to assist incarrying out such risk assessments; (3) to havea proper system of inspection and maintenancein respect of the LPG pipework concerned,and (4) to ensure, so far as was reasonablypracticable, that the pipework was maintainedin a condition that was safe and without risk toemployees.On 17 August 2007 at Glasgow High Court,the companies pled guilty as libelled to thecharges.<strong>The</strong> Crown and the defence agreed thatthe cause of the collapse of the building atGrovepark Mills had been an explosion; thatthe cause of the explosion had been the ignitionof an accumulation of LPG in the basementarea of the building; and that this accumulation7

PART 218

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTPart 29

PART 2Chapter 4 – Liquefied petroleum gasLiquefied petroleum gas (LPG) is the genericterm for hydrocarbon fuel gases with theprimary active constituents propane and butane.<strong>The</strong>se constituents are derived from petroleumand can be readily converted to liquid formby the application of moderate pressure and/or refrigeration. LPG is normally supplied in theform of commercial propane.In liquid form, it occupies a smaller volumethan the corresponding volume of gas. Atatmospheric temperature and pressure, 1m³of liquid vaporises to form 274m³ of gas. Asa liquid at ambient temperature, LPG exerts apressure equivalent to its vapour pressure. It musttherefore be stored in a suitable pressure vessel.<strong>The</strong> compressibility of LPG makes it particularlysuitable for bulk storage and transportation.Due to the possibility of its expansion, LPGtransported as liquid presents a greater hazardthan that transported as vapour.Vaporised LPG at atmospheric pressure isapproximately one-and-a-half to two timesheavier than air. Escapes of LPG therefore tendto flow along the ground or the floor and toaccumulate at low points such as pits, sumps,drains, basements and the bilges of boats.Natural gas is lighter than air and thereforedissipates more easily into the atmosphere.When LPG is released to atmosphere itvaporises and mixes with air. <strong>The</strong> mixtureis flammable at concentrations of between2% and 10%. It burns most energeticallywhen the mixture is about 4% to 5% in air (a“stoichiometric mix”). At concentrations below2% the mixture does not burn as it is tooweak to sustain combustion. At concentrationsabout 10% it does not burn as it is too rich.By contrast, natural gas is flammable in air atconcentrations between 5% and 15% and burnsmost energetically at a mix of about 9%.Because of its greater density and itsflammability in air at lower concentrations, LPGpresents a greater hazard than natural gas.<strong>The</strong> special hazards of LPG have been wellunderstood for many years.LPG fire and explosion incidents are relativelyuncommon in relation to other incidents andwhere they do occur they relate mostly to LPGin liquid form. Only a small number of incidentscan be found on HSE’s databases involvingLPG leaks from pipes. Only one of these wasidentified by the <strong>Inquiry</strong> as having occurredbefore May 2004 involving vapour rather thanliquid. This incident occurred at LightweightBody Armour in Daventry in 1988 and involveda vapour leak from a buried pipe operating at30 psi (2 bar).<strong>The</strong> greater risk presented by the loss of LPGin liquid phase has resulted in priority beinggiven by HSE to producing guidance on liquidphase releases. According to HSE, “this isdue to the fact that one volume of liquid willexpand to give approximately 250 volumesof gaseous LPG and 12000 volumes of LPGat the lower flammable limit. As a result, thepotential consequences of a leak of liquidcompared with a similar sized leak of vapourare that much greater” … “Whilst both LPGstorage tanks and LPG pipework carry withthem the inherent hazard of leakage of LPG,the risk of leakage and its consequences,are generally much greater for bulk storagevessels containing liquid LPG. <strong>The</strong> pressuresare generally higher and the quantities thatcould escape are larger than for LPG pipeworkcontaining liquid, which in turn are greater10

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTthan that for vapour pipelines. This is borne outby the known incident record. <strong>The</strong> majority oflarge scale incidents involving releases of LPG,both nationally and internationally, are knownto have involved bulk vessels as opposed topipework... In contrast, the incident recordsuggests that the risk of deaths or injuriesresulting from a low pressure LPG leak from apipe is low, especially where bulk storage is notinvolved.”Although HSE considered the risk of arelease of liquid LPG to be low, the potentialconsequences of such a leak can be high.<strong>The</strong>re may also be serious consequences ifLPG leaks into an unventilated void. Users andsuppliers must therefore adhere to the highestpossible standards when storing and handlingLPG.Since LPG, like natural gas, is odourless in itsnatural state, a stenching agent is added tomake it detectable, by persons with a normalsense of smell, at concentrations of one fifth ofthe lower limit of flammability. <strong>The</strong> stenchingagent is an important safeguard against therisks of fire and asphyxiation which arise whenhigher concentrations of LPG accumulate inconfined spaces.Several witnesses in this case said that theydid not smell the LPG stenching agent beforethe explosion. <strong>The</strong> explanation is that since thepropane gas was heavier than air the smellwould probably have been evident only in thebasement.11

PART 2Chapter 5 – LPG installationsTypical LPG installation for smallcommercial customers<strong>The</strong> industry norm is for the LPG supplier tosupply both the product and the tank to theindustrial and commercial customer. Installationsvary according to the supplier.<strong>The</strong> following description relates to two ofthe industry’s typical installations. It should benoted that, save for regulations 37, 38 and 41and subject to regulation 3(8), the Gas Safety(Installation and Use) Regulations 1998 (GSIUR)as matters stand do not apply generally to‘factories’ within the meaning of the FactoriesAct 1961.<strong>The</strong> pipework within an LPG installationis defined by reference to the part of theinstallation within which it is incorporated. <strong>The</strong>service pipework is that which runs from thetank regulator to the emergency control valve(ECV). <strong>The</strong> GSIUR definition of service pipeworkmeans “a pipe for supplying gas to premisesfrom a gas storage vessel, being any pipebetween the gas storage vessel and the outletof the ECV”. <strong>The</strong> installation pipework runs fromthe ECV to the isolation valve at the appliance.<strong>The</strong> GSIUR definition of installation pipework“means any pipework for conveying gas for aparticular consumer and any associated valveor other gas fitting including any pipework usedto connect a gas appliance to other installationpipework and any shut off device at the inletto the appliance, but it does not mean (a) aservice pipe; (b) a pipe comprised in a gasappliance; (c) any valve attached to a storagecontainer or cylinder; or (d) service pipework”.<strong>The</strong> “appliance pipework” runs from theappliance servicing valve to the appliance itself.Calor supplied details of the set-up of theirtypical LPG installation. For the most part itis typical of the industry. <strong>The</strong> diagram belowillustrates this.Figure 2 - Calor diagram12

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORT3 IN-LINE VESSEL LOW PRESSURE INSTALLATION1st StageRegulator2nd Stage Regulatorwith UPSO/OPSOCombination (Combo) Valve1. Filler Valve2. Liquid Offtake Valve3. Vapour Offtake ValveFloatGaugePressure ReliefValve (PRV)5 IN-LINE VESSEL LOW PRESSURE INSTALLATIONServicePipework2nd Stage Regulatorwith UPSO/OPSO1st StageRegulatorPressure ReliefValve (PRV)FillerValveLiquid WithdrawelValveVapourOfftake ValveFloatGaugeFigure 3On top of the tank, there are three valves,which may be located separately, or maybe grouped together in a single combinationvalve. Those valves are the filler valve, usedin the filling of the tank; the liquid withdrawal‘off-take’ valve, used for the removal of liquid formaintenance purposes; and the vapour off-takevalve, from which the vapour travels out of thetank into the pipework.<strong>The</strong>re are two further items on the top of thetank itself; the float gauge, which indicates thelevel in the tank, and the pressure relief valve.An installation with a combination valve,pressure relief valve and float gauge is referredto as a three-in-line. Where the filler, liquid offtakeand vapour off-take valves are separatedon the top of the tank it is referred to as a fivein-line.13

PART 2Pressure ReliefValveFigure 4 – <strong>ICL</strong> tank with the hood offFigure 5 – Pressure Relief ValveRelief ValveAdaptorFigure 6Figure 7 – Relief Valve Adaptor<strong>The</strong> LPG is stored as liquid within the tank, atnormal vapour pressure of about 7 bar. Afterleaving the vapour off-take valve, the vapourpasses through the first stage regulator, whicheffects an initial reduction in pressure fromabout 7 bar to 0.7 bar. <strong>The</strong>reafter, it passesthrough a second stage regulator, whichreduces the pressure from 0.7 bar to about 37millibar, the usual and safe operating pressure.Underpressure and overpressure valves arenormally incorporated within the second stageregulator. <strong>The</strong> former shuts off the supply if thereis a drop in pressure at the tank end of theinstallation; for example, if the tank runs dry. <strong>The</strong>latter shuts off the supply if there is an increasein pressure; for example, if the regulator fails.14

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTFiller valveFillervalveLiquid offtakevalveVapour offtakevalveFigure 8 – 3-in-line valve installationFigure 9 – 5-in-line valve installationOverpressure shut-off(OPSO) valveUnderpressure shut-off(UPSO) valveFigure 10 – 2nd stage regulatorFigure 11 – 2nd stage regulator<strong>The</strong> positions of the first and second stageregulators vary. <strong>The</strong> first stage regulator is oftenconnected directly into the combination valve.<strong>The</strong> second stage regulator is often connecteddirectly to the first stage regulator. Alternatively,the first stage regulator may be sited somedistance away from the tank. <strong>The</strong> two regulatorsmay be widely separated, with the first stageregulator sited at or near the tank, and thesecond stage regulator close to the entry pointto the building that the installation serves. In thatcase, any section of underground pipework thatconnects the two regulators will be carryingvapour at about 0.7 bar, rather than at thereduced pressure of 37 millibar. <strong>The</strong> first stageregulator is commonly sited away from the tank15

PART 2Figure 12 – Typical single bulk vessel operating with vessel mounted regulators and low pressure underground pipeworkFigure 13 – Installation with 2nd stage regulator close to building entry point16

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTFigure 14 – 1st stage regulator serving 2 tankswhere there is a manifolding or joining togetherof two tanks and the first stage regulator servesboth. In that case, the first stage regulator isusually supported on the pipework which entersthe ground (Fig. 14).Exceptionally, installations may have a singleregulator effecting a one-stage reduction ofoperating pressure. In more modern installations,the pressure reduction may be effected in threestages.Where an installation incorporates a section ofunderground pipework, the vapour leaves thelast of the valves on the tank by way of metallicpipework, which connects to a polyethylene(PE) upright by way of a transition coupling.17

PART 2<strong>The</strong> typical installation used by Johnston Oilsis different from Calor’s in only minor respects.Johnston Oils prefer not to use a combinationvalve on top of the tank. Where the secondstage regulator is installed on the tank, theygenerally place it further along the pipeworkleading from the vapour off-take valve, at adistance from the first stage regulator. JohnstonOils, like Calor, have installations with one orboth of the regulators sited further downstreamfrom the tank.Figure 15 – Typical Emergency Control Valve (ECV) onoutside of property<strong>The</strong> upright section is covered by a GlassReinforced Plastic (GRP) sleeve, which protectsthe PE against both mechanical damage anddegradation by U V light. Where it enters theground, the PE pipework is covered by blacktubes, known as “hockey sticks” which give astandard radius to the pipe thereby preventing itfrom over-bending or being crushed.Where the pipework re-emerges from the groundnear the building, it will again be protected by ahockey stick and GRP sleeve. It passes througha transition fitting into the emergency controlvalve (ECV), which can turn off the supply. Afterthe ECV, the pipework often changes to copperwhich is sleeved as it passes through the wall ofthe building. <strong>The</strong>re is generally a warning signbeside the ECV, specifying what is to be done ifthere is a gas escape.If the pipework between the tank and thebuilding is above ground, galvanised steel isused rather than PE.<strong>The</strong> use of metal and polyethylene inburied service pipeworkPipework of various materials has beenused in underground sections of servicepipework. In the past, service pipework wasusually metallic. Such pipework was usuallygalvanised, often with a thin zinc coating, toprotect against corrosion. It was often alsowrapped with Denso tape, a proprietary tapeused as corrosion protection. For Denso tapeto be effective the pipework must be carefullyprepared and the tape must be applied in aparticular way. This is a difficult procedure. Itis often not adhered to properly. Unprotectedburied metallic pipework is likely to have alifespan of about thirty years; but corrosionleading to failure and leakage can occurconsiderably sooner than that.Polyethylene first came into use in the 1980s. Atthat time, only a limited number of installationswere installed with all-polyethylene pipework.From 1983 to about 1992 the practice wasto use polyethylene for the buried section ofthe service pipework, with metallic risers ateither end. <strong>The</strong> understanding at that time wasthat the metallic riser gave better protectionthan polyethylene against fire and mechanicaldamage. In due course, the LPG industry18

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORT<strong>The</strong> standard material currently used forunderground service pipework is polyethylene.<strong>The</strong> norm is that all the pipework incorporated inan installation will be made of polyethylene. MrTomlin of Calor Gas said that it is not susceptibleto corrosion and has a lifespan of about fiftyyears. Dr Fullam of HSE said that “polyethylene(PE) pipe is impervious to most corrosionmechanisms including those that are biologicallybased. Medium density PE is manufacturedwithout a plasticiser and it is therefore less likelyto become brittle over time as a result of the lossof the plasticizer. PE pipes can last in excess of25 years. <strong>The</strong> main reason for failure is humaninterference, for example, someone digging it up”.Figure 16 – Typical ECV labelbecame less concerned about that risk andcame to use polyethylene risers protected byGRP sleeves. Where risers were made of steel,the parts of them below ground level weregenerally protected against corrosion by beinggalvanised and wrapped with Denso tape.From about 1993 onwards, the great majorityof new installations used only polyethylenepipework. Recent research into installationsinstalled before 1993 disclosed that of thoseexamined, 73% had polyethylene servicepipework with metallic risers, 13% hadpolyethylene pipework only, 9% had metallicpipework only, and 5% had pipework ofcopper or multiple materials.Tightness test and proof testA tightness test may also be described as asoundness or leak test. It is a pneumatic pressuretest to ensure the gas tightness of pipeworkfittings and components. It may also be used tocheck the effectiveness of shut-off devices. It iscarried out on an exchange of tanks, and afterany work is carried out on a gas fitting that mightaffect the tightness of the overall installation.<strong>The</strong> definition of a tightness test in IGE/TD/4polyethylene and steel gas services and servicepipework is “a specific procedure to verify thatpipework meets requirements for gas tightness”.GSIUR details the legal requirements fortightness testing LPG installations. Regulation6(6) provides that:“Where a person carries out any work inrelation to a gas fitting which might affectthe gas tightness of the gas installationhe shall immediately thereafter test theinstallation for gas tightness at least asfar as the nearest valves upstream anddownstream in the installation.”19

PART 2A proof test, otherwise known as a strength test,is a pressure test to establish that the mechanicalintegrity of pipework, fittings and componentsmeets the required standard. It is carried out ata higher pressure than a tightness test, abovethe operating pressure of the installation, andis used to determine the strength of a systemfollowing its construction. A proof test shouldnot be carried out on an installation with whichthe engineer is not familiar. If an engineer raisesthe pressure of a system above the normaloperating level without knowing how theinstallation was designed, what it is constructedof and how it was constructed, he risks his ownsafety and that of others in the vicinity. <strong>The</strong>definition of a strength test in IGE/TD/4 is “aspecific procedure to verify that pipework meetsthe requirements for mechanical strength”.When Maurice Coville of Calor gave adviceabout the <strong>ICL</strong> installation, as I shall laterdescribe, a tightness test was understood bythe LPG industry to be an appropriate methodfor determining the integrity of an undergroundpipe. I deal with that part of the history later.It is now recognised that a tightness test carriedout on existing buried pipework gives noindication of its integrity. Even though a tightnesstest is satisfactory, the pipework may be in poorcondition and may be about to develop a leak.A tightness test should be used in conjunctionwith other appropriate methodologies todetermine the overall suitability of the pipeworkfor its continued use; for example, a leakagesurvey, records, operating pressure, material ofconstruction, and so on.Responsibilities for the Commercial/Industrial LPG Installation<strong>The</strong> responsibilities of the supplier and the userfor an LPG installation are determined by theterms and conditions of the supply contract. Ingeneral, the supplier is responsible for the tank,together with the associated pipework up toeither the vapour off-take valve or the first stageregulator. I discuss this important distinction later.<strong>The</strong> supplier is generally not responsible for theservice pipework downstream of either point.Any service pipework between either point andthe emergency control valve, whether buried ornot, is the responsibility of the user.<strong>The</strong> responsibilities of supplier and user in thenatural gas industry are different. Responsibilitiesfor natural gas are divided into two categories:transportation and supply. A natural gastransporter is responsible for the transportationand conveyance of the gas as far as theemergency control valve, while the supplier hasresponsibility for supplying from the emergencycontrol valve through to a meter regulator, whichis regarded as the end of the network. <strong>The</strong> userhas responsibility for the installation after themeter. <strong>The</strong>refore, the transporter will generallyhave responsibility for any buried servicepipework up to the emergency control valve,whether it is outside or inside the building.Regulation 37 of the Gas Safety (Installationand Use) Regulations 1998 (the GSIUR) carrieswith it certain responsibilities in the event of agas leak. In particular, it imposes an obligationto prevent an escape of gas within twelvehours of its being notified. In relation to naturalgas, that obligation lies with the transporter. Inrelation to LPG, it lies with the supplier.<strong>The</strong>re is a difference of approach betweenLPG suppliers as to the point up to which thesupplier takes responsibility for the installation.Calor’s responsibility for it ends at the vapour20

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORToff-take valve. Johnston Oils takes responsibilityup to the first stage regulator, a position thatseems to be regarded by UKLPG as the industrynorm. Suppliers such as Johnston Oils take thatapproach whether the first stage regulator issituated at the tank or is remote from it. It is myimpression that before evidence on the pointcame out at the <strong>Inquiry</strong>, the industry seems notto have regarded these differences in approachas being significant.It is usual industry practice for the supplier toinstall the service pipework up to the emergencycontrol valve, although the supplier will nothave ultimate responsibility for it. Nothing isvisible on the installation in terms of a notice orcolour coding to indicate where responsibilitypasses from the supplier to the user. <strong>The</strong> usualpractice is that users are made aware of theirresponsibilities for service pipework throughthe contract and, in the case of Calor, by theprovision of a welcome pack.Tank exchangeIt is relatively common for LPG users to changesupplier at the end of a contract. <strong>The</strong> outgoingsupplier removes its tank, and the incomingsupplier connects its own tank to the installation.<strong>The</strong> LPG industry considers that the use of anintegrated system makes it easier for the userto change suppliers. An exchange of tanks ofthis kind is generally described as a like-for-likeexchange. <strong>The</strong> result is that the new suppliermay know nothing of the history and conditionof the pipework to which its tank is beingconnected.Different approaches are adopted by differentsuppliers when taking over the supply to anexisting installation. Calor’s procedure is toinstall the tank, carry out a visual inspection ofpipework that is above ground, and carry outa tightness test on the installation. Calor assumethat the customer has fulfilled all responsibilitiesin relation to any section of underground servicepipework and that it is in safe condition. Calor’sprocedure in this respect has not changedsince 2004. Johnston Oils adopted the sameapproach as Calor until 2004; but since2005, in response to the <strong>ICL</strong> disaster, theyhave carried out a full risk assessment of theinstallation when taking over a supply. This maylead to their recommending replacement ofthe underground service pipework should therebe any doubt as to its age or condition. If theuser does not follow such recommendations,Johnston Oils will refuse to supply to theinstallation.It is now recognised by the industry that thecarrying out of a like-for-like exchange maygive rise to difficulty where the outgoing andincoming suppliers operate different regimesof responsibility for the installation. Industrypractice seems to have been to assume that ina like-for-like tank exchange there was a like-forlikeexchange of responsibilities.But if the outgoing supplier takes responsibilityto the first stage regulator, and the incomingsupplier takes responsibility only to the vapouroff-take valve, the user may not realise thatit has assumed responsibility for the servicepipework in between.Strengths and weaknesses ofthe present system regardingresponsibility for service pipeworkIt was accepted by all relevant witnesses thatit was undesirable that different approachesshould be adopted by different suppliers withregard to responsibility for pipework.21

PART 2Bulk Propane Tank Propane Cyclinder LPG OvenLPG BurnerMill WallLPG Oven BurnersGround LevelPilot LightsRegulator &Pressure GaugeUndergroundPipeFigure 17Figure 18 – <strong>The</strong> vapour take off valve fitted to the onetonnepropane storage tankAll of the witnesses who discussed the pointwere unanimous in their view that responsibilityfor service pipework should remain with the LPGuser. <strong>The</strong>y reached that view on the basis thatit is the user who has day-to-day control overthe site and, therefore, the service pipework,together with knowledge of the installationdownstream of the tank and associatedvalves. A supplier would also face difficultiesin obtaining insurance for a liability in respectof the service pipework since that was a riskwhich it could not control. <strong>The</strong>re is an importantdistinction between the natural gas and theLPG industries in that the natural gas customerhas no control over a gas escape upstream ofthe emergency control valve, whereas an LPGcustomer can control the supply of gas into theservice pipework by simply closing the isolationvalve at the tank in the event of an escape. <strong>The</strong>proper comparison to be drawn, I think, is notbetween LPG and natural gas, but between LPGand other packaged fuels and chemicals, suchas oil and compressed gas.One of the important questions in this <strong>Inquiry</strong> iswhether the supplier’s responsibility should endat the vapour off-take valve, in accordance withCalor’s practice, or at the first stage regulator,in accordance with the general industry view.Calor consider that making the demarcation atthe vapour off-take gives a degree of certaintythat is not present if the first stage regulator isregarded as the relevant point, because thefirst stage regulator may be located at differentplaces at different sites. On the other view, itmay be desirable for the pipework up to the22

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTFigure 20 – <strong>The</strong> witness marks (arrow) in the circlip grooveleft by the missing excess flow valve circlipFigure 19 – <strong>The</strong> witness marks (arrow) left by the missingexcess flow valve springFigure 21 – <strong>The</strong> one-tonne storage tanFigure 22 – <strong>The</strong> two manifolded 47kg propane cylindersfirst stage regulator to remain the responsibilityof the supplier, since it contains high pressurevapour. I shall discuss this question later.<strong>The</strong> <strong>ICL</strong> Installation<strong>The</strong> diagram (Fig. 17) represents the <strong>ICL</strong>installation at the date of the explosion. <strong>The</strong>complete LPG system consisted of a one tonnetank, two 47 kg cylinders, surface pipeworkand regulator, underground pipework to thebasement of the building, pipework within thebuilding, LPG oven and ancillary items.<strong>The</strong> one-tonne tank that had been fitted byJohnston Oils on 29 November 1998 wasfitted with a vapour off-take valve (Fig. 18).23

PART 2Figure 23 – <strong>The</strong> position of the LPG pipe as it enters theground from the one-tonne propane storage tank end.Figure 24 – <strong>The</strong> LPG underground pipeline enters thebuilding in an alcove in the basementAlthough the valve appeared to have beenoriginally fitted with an excess flow valve,which fitted into the base of the valve, the innerworkings of the valve were absent when DrHawksworth inspected it. <strong>The</strong>re was evidencethat the working components of the valve hadbeen in place at some time. This type of excessflow valve is intended to protect against a fullpipe failure, or shear. It is not intended to offerany protection against a crack or a split in thepipe; nor to protect an underground pipe. <strong>The</strong><strong>ICL</strong> installation was unusual in that there wasno second stage regulator because of the highoperating pressure of the oven.section of pipe that incorporated a furthervalve and a high pressure regulator. Below theregulator the pipe went underground.<strong>The</strong> underground pipe went from the positionclose to the tank to enter the building in analcove in the basement. It then went up throughthe dispatch floor to the ground floor ceilingeventually to connect to the LPG oven. <strong>The</strong>valve shown (Fig. 24) was, in the past, used toisolate the LPG supply into the building.<strong>The</strong> pipework from the tank was initially 10mmouter diameter (OD), nominal internal diameter(ID) 8.4mm, copper tubing connecting to 1 inchsteel pipe about 0.5m from the outlet. <strong>The</strong> oneinch pipe fed back to a T-coupling (through anin-line valve) where a further flexible hose, alsofitted with an in-line valve, connected to two 47kg propane cylinders. <strong>The</strong> other side of the pipeT-coupling then dropped down to a vertical24

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTChapter 6 – <strong>The</strong> LPG industryUKLPG<strong>The</strong> trade association of the LPG industryis UKLPG. UKLPG was formed in January2008, by amalgamation of the LPGA (the LPGAssociation) and ALGED (the Association forLiquid Gas Equipment Distributors), which wereformed in 1947 and 1975 respectively. Its mainpurpose is to promote the highest safety andtechnical standards. It encourages its membersto assist it on such matters. It keeps its membersinformed of forthcoming changes that mightaffect the industry and provides them with allrelevant Codes of Practice. I discuss these inmore detail in Part 3.Most of the members of UKLPG are retailsuppliers to direct end users, who are generallysmall customers. <strong>The</strong> industry is dominatedby four majors, namely Calor Gas, Flo Gas,Shell and BP. Several wholesale suppliers aremembers, including Total, Conoco Philips andTexaco Chevron. <strong>The</strong> membership of UKLPGaccounts for 95% of suppliers of LPG in the UK.<strong>The</strong> remaining 5% account for only about 1%of the total quantity of LPG supplied in the UK.<strong>The</strong>y are mostly independent companies, oftenoperated by individuals who have previouslyworked for larger suppliers. For the most partthey observe the UKLPG Codes of Practice.I am impressed by the quality of UKLPG’s workin its field. It has produced an updated Code ofPractice that is comprehensive and incorporatesthe lessons of experience. <strong>The</strong> Code hasfollowed a careful process of consultation withinthe industry and with HSE. <strong>The</strong> paramount aimof the Code is safety. UKLPG’s approach is notbased on considerations of cost.UKLPG has made an outstanding contributionto this <strong>Inquiry</strong>. It has provided a detailed surveyof the history of the practice of the industry anda reasoned and constructive response to therecommendations of Mr Sylvester-Evans.Institute of Gas Engineers andManagers (IGEM)<strong>The</strong> Institute of Gas Engineers and Managers(IGEM) is the chartered body for gas industryprofessionals and draws representation fromboth the natural gas and LPG industries. IGEMhas published industry standards since the1960s, including those on gas and mainsservices.Members of UKLPG are obliged to adhere toits Articles of Association and to comply withits Codes of Practice. UKLPG has the powerto suspend or expel members for breaches ofits Codes of Practice. It will generally find outabout a member’s failure to adhere to a safetyrequirement through a complaint by the publicor by a fellow member. <strong>The</strong> Board reviews anycomplaints received. In twenty years, UKLPGhas had to suspend only one member for aserious breach of safety.25

26PART 2

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTPart 327

PART 3Chapter 7 – <strong>The</strong> regulatory systemIntroduction<strong>The</strong> regulatory regime is extensive in relationto LPG, but in most cases is not specific to it.It consists of primary legislation, secondarylegislation, codes of practice, HSE guidance,industry guidance, and building, planning andfire legislation. I do not propose to analysethis wealth of material in detail. It is sufficientfor the purposes of this inquiry to say that thelegislation is complex and is spread over amultiplicity of statutes and regulations. Much ofit reflects the changes in emphasis in health andsafety legislation over the years.<strong>The</strong> diversity of these sources and the manyproblems of interpretation of them make itdifficult for the layman to understand the law.That in itself is a significant weakness in thepresent safety regime.Health and SafetyHealth and safety in essence means themanagement of the risks to people’s health andsafety from work activities. To be truly effective,health and safety has to be an everydayprocess supported by everyone involved as anintegral part of workplace culture - employers,employees, third party organisations such asSTUC, TUC, employer organistaions, tradeassociations (notably UKLPG in the context ofthe subject matter of this report) consultant firmsand voluntary organisations producing healthand safety guidance.<strong>The</strong> Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 andits underlying principles and philosophy providea legislative framework that is adaptable.<strong>The</strong> Act established the simple principlethat those who create risk are best placedto manage it. This applies whether the riskmaker is an employer, is self-employed oris a manufacturer or supplier of articles orsubstances for use at work. Each risk maker hasa range of duties that must be implemented tomanage the risk.All workers have a fundamental right to workin an environment where risks to health andsafety are properly controlled. <strong>The</strong> primaryresponsibility for this lies with the employer.Workers also have a duty of care for their ownhealth and safety and for the health and safetyof others who may be affected by their actions.<strong>The</strong> legislation requires that workers shouldco-operate with employers on health and safetyissues.<strong>The</strong> Act led to the setting up of the Health andSafety Commission (HSC) and the Health andSafety Executive (HSE) and established HSEand local authorities as joint enforcers of healthand safety law. On 1 April 2008 HSC andHSE merged to form a single entity known asthe Health and Safety Executive (HSE).HSE is the national regulatory body responsiblefor promoting the cause of better health andsafety at work within the United Kingdom. Itworks in partnership with local authorities toprovide strategic direction and to lead themanagement of the risks to health and safetyfrom work activities as a whole. To do this itconducts research, proposes new regulationswhere and when needed, introduces newor revised regulations and codes of practice,alerts duty holders to new and emerging risks,provides information and advice and promotestraining. Its focus is on identifying practical stepsand measures which can be taken by dutyholders to reduce the risks that people may bekilled, injured or made ill by work activities.28

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTIts key role is to ensure that duty holders aremotivated to do the right thing because itmakes sense and to support the duty holders inintegrating health and safety into their functionsand responsibilities in a commonsense andproportionate way.Enforcement has three main objectives: 1) toseek to compel duty holders to take immediateaction to deal with the identified risk; 2) topromote sustained compliance with the law; 3)to look to ensure that duty holders who breachhealth and safety requirements, and directors ormanagers who fail in their responsibilities, areheld to account for their actions.Better Regulation<strong>The</strong> Better Regulation Commission’s summary,updated in December 2007, is that the fiveprinciples of good regulation should be:• Proportionate: Regulators should onlyintervene when necessary. Remedies shouldbe appropriate to the risk posed, and costsidentified and minimised.• Accountable: Regulators must be able tojustify decisions, and be subject to publicscrutiny.• Consistent: Government rules and standardsmust be joined up and implemented fairly.• Transparent: Regulators should be open, andkeep regulations simple and user friendly.• Targeted: Regulation should be focused onthe problem, and minimise side effects.Competency<strong>The</strong>re is confusion in the health and safetyenvironment between a qualified person anda competent person. <strong>The</strong> legislation makesrequirements for engagement of a “competent”person. In essence a person is to be consideredcompetent if he has the ability to applyknowledge in a way that is proportionate,meaningful and useful to the intended audience.<strong>The</strong> essence of competence is said by HSEto be relevance to the workplace with therequirement that there is a proper focus onboth the risks that occur most often and thosewith serious consequences. Competence is theability for every director, manager and workerto recognise the risks in operational activitiesand then apply the right measures to controland manage those risks.Hierarchy and status of legislation<strong>The</strong> primary legislation is the Health andSafety at Work Act 1974 (HSWA). It allowsfor secondary legislation, usually in the form ofregulations and approved codes of practice.Regulations are made by the appropriateMinister, normally on the basis of proposalssubmitted by HSE after consultation. <strong>The</strong>y haveto be laid before Parliament for a period of 21days before coming into force. It is a criminaloffence to fail to comply with any requirementof a regulation.Approved codes of practice (ACoPs) areapproved by HSE with the consent of theappropriate Secretary of State. <strong>The</strong>y do notrequire agreement from Parliament. ACoPs havea special authority in law. Failure to complywith an ACoP may be taken by a court incriminal proceedings as evidence of a failureto comply with the requirements of the Act or ofregulations to which the ACoP relates, unlessit can be shown that those requirements werecomplied with in some equally effective way.ACoPs therefore provide flexibility to cope withinvention and technological change without alowering of standards.29

PART 3HSE also publishes non-statutory guidanceto accompany regulations. Guidance is notcompulsory. In comparison with subject-specificregulations, guidance is more straightforwardand quicker to produce. It is also simpler tokeep up to date. Health and safety inspectorsmay refer to guidance to illustrate goodpractice.<strong>The</strong> industry is often best placed to produceits own guidance and codes of practicesfrom its collective experience and knowledgeof the hazards, risks and best practice. Onthis approach the industry itself advocatesand promulgates best practice. Since 1998much of this guidance has been producedin collaboration with HSE. Codes of Practiceproduced by UKLPG are prepared inconsultation with HSE. Some carry an HSEforeword stipulating that the UKLPG Codesof Practice are not to be regarded as anauthoritative interpretation of law but that tofollow them will be regarded normally as doingenough to comply with the health and safetylaw. <strong>The</strong>re is a strong demand from users fornon-statutory guidance of this kind.statement published in 1996, HSE emphasisedthe continuing importance of standards as aform of guidance in promoting health andsafety.<strong>The</strong> history of the legislation,regulations codes and guidanceTo assist in the interpretation of the history of thiscase, I set out in Appendix 3 a table showingthe legislation, regulations, codes and guidancethat were in force at the key dates. As indicatedin the table, some of the earlier guidancereferred to was internal to the FactoriesInspectorate and the HSE.<strong>The</strong> relevant dates relating to the <strong>ICL</strong> installationhave been marked on this table. <strong>The</strong>y are thedate of installation (1969), the date at which theyard was raised (January 1973), the date onwhich the LPG tank was exchanged by Calor(1982), the date of the Ives/Coville compromise(1988), the change of supplier from Calorto Johnston Oils (1998) and the date of theexplosion (11 May 2004).Information from HSE’s inspections andinvestigations is used when identifyingstandards, which may be published as informalguidance or as formal standards. <strong>The</strong> BritishStandards Institution is the national bodyresponsible for the development of Britishstandards. <strong>The</strong> great majority of these aretransposed European or international standards,for example BS5482 – Code of Practice forDomestic Butane and Propane Gas BurningInstallations. <strong>The</strong>y are sometimes referred toin HSE’s published guidance. Occasionally,compliance with standards is required in healthand safety regulations and codes. In a policy30

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTPart 431

PART 4Chapter 8 – <strong>The</strong> <strong>ICL</strong> groupof companies<strong>The</strong> <strong>ICL</strong> group consists of privately ownedlimited companies. <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics Limited is theholding company. <strong>ICL</strong> Technical Plastics Limitedand Stockline Plastics Limited are two of its sixoperating subsidiaries.<strong>ICL</strong> Plastics Limited<strong>ICL</strong> Plastics Limited (<strong>ICL</strong> Plastics) wasincorporated on 17 November 1961 with itsprincipal object being:“to carry on the business of processingplastics by all methods including ‘fluid bed’plastic dip coatings in various finishes, coldplastic spraying, plastic sheet welding,plastic slush moulding, plastic vacuumforming and fibreglass resin bondedmoulding”.Campbell Downie was the sales and financedirector. Ronald Cunningham was theproduction director. He resigned in 1966.Latterly, Campbell Downie had non-executiveduties.Campbell Downie’s wife Lorna was appointedcompany secretary on 26 April 1972. On25 May 1972, Ronald Ferguson and StewartMcColl were appointed as directors.In May 2004 Campbell Downie’sshareholding, and minimal shareholdings heldby his children, amounted to 68% of the sharesin <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics. Ronald Ferguson held 28% andStewart McColl held 4%.Between 1973 and 1975, subsidiarycompanies were created for the manufacturingand distribution operations. <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics, as theholding company with Campbell Downie aschairman, became responsible for maintainingthe group’s financial resources, providingaccounting and IT services, carrying outstrategic market analysis and undertakingresearch and development. Mr Downiewithdrew from all executive duties in thesubsidiaries after executive directors wereappointed.<strong>ICL</strong> Technical Plastics Limited<strong>ICL</strong> Technical Plastics Limited was incorporatedon 26 November 1973 to continue to developand specialise in production methods. Itsprincipal object was the same as that of <strong>ICL</strong>Plastics.<strong>The</strong> ownership and responsibility for the fixedplant and equipment to carry out this functionwere transferred from <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics to <strong>ICL</strong>Technical Plastics Limited. <strong>The</strong>re was no transferof the title to the site.Campbell Downie and Lorna Downie were theinitial directors. Lorna Downie resigned on 13December 1973 and was replaced by RogerWoodford. He resigned on 27 September1977 when Stewart McColl was appointedas a director with responsibility for sales. FrankStott was appointed on 27 April 1978 in placeof Campbell Downie and was managingdirector until 31 October 1998. He remained adirector until 22 January 2004. Peter Marshallwas managing director from 12 October 1998until he resigned on 1 October 2000.<strong>ICL</strong> Plastics owned about 83% of the sharesin <strong>ICL</strong> Tech. <strong>The</strong> minority shareholder in <strong>ICL</strong>Tech was Frank Stott who held 17% of theshares. Campbell Downie also held a minimalshareholding.32

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTOn 19 August 1999 the company changedits name to <strong>ICL</strong> Tech Limited (<strong>ICL</strong> Tech). At thetime of the disaster, <strong>ICL</strong> Tech employed 33people.Stockline Plastics LimitedStockline Plastics Limited (Stockline) wasalso incorporated on 26 November 1973.Its main function was to stock and distributeall forms of plastic, acrylic, polystyrene,polythene and other similar materials. In2004 its main operations were conducted inthe warehouse building adjacent to the mainbuilding.Campbell Downie and Stewart McColl wereboth appointed directors of Stockline in January1973.<strong>The</strong> offices for <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics and <strong>ICL</strong> Tech werein the main building at Grovepark Mills inwhich <strong>ICL</strong> Tech carried out its industrialprocesses.<strong>The</strong> directors of companies in the <strong>ICL</strong>group as at 11 May 2004As at 11 May 2004, Campbell Downie wassemi-retired chairman and non-executive directorof <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics, Stewart McColl was the salesdirector, Margaret Brownlie was the financedirector and Lorna Downie was the personneland company secretary. Ronald Ferguson wasa director but had no management role atany time. Stewart McColl was the managingdirector of <strong>ICL</strong> Tech.<strong>The</strong> directors were paid a salary and couldhold up to 25% of the shares in their company.Salaries were set against what each companycould afford to pay and remuneration fluctuatedaccordingly. <strong>The</strong>re were no mechanisms toaward directors’ bonuses.<strong>The</strong> <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics group was self-financing andhad no borrowings.Campbell DownieMr Downie took semi-retirement from <strong>ICL</strong> Plasticsin the mid 1980s. From then on his mainfunction was to provide financial and strategicguidance to <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics.<strong>The</strong> financial management of the companieswas tightly monitored. Mr Downie developeda funds flow system of financial accounting toallow his fellow directors to see exactly whereeach company stood on a month to monthbasis.In the early days Mr Downie spent about athird of his time on the <strong>ICL</strong> premises. His visitsbecame more irregular from the mid 1980sas the <strong>ICL</strong> Group expanded and he had tobe away from Glasgow more frequently.Following his semi-retirement, he left the dayto day running of the operating subsidiaries tothe individual directors and rarely worked onthe premises. From the 1990s onwards he metwith Margaret Brownlie at <strong>ICL</strong>’s office once ortwice a week to discuss finance, IT programmedevelopment and related matters.Although semi-retired, Mr Downie was regularlyconsulted by directors of both <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics and<strong>ICL</strong> Tech in relation to any decisions that werefinancially significant.Mr Downie did not regard himself as havingthe ultimate control and responsibility for theoperating decisions for <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics, <strong>ICL</strong> Techor any of the other subsidiaries. He described33

PART 4the <strong>ICL</strong> company structure as flat rather thanhierarchical. <strong>The</strong> directors of each subsidiarymade their own decisions. At board meetingsMr Downie presided but did not exercise a voteexcept if there was disagreement between thedirectors. As chairman, he had a casting vote.34

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTPart 535

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORT<strong>The</strong> despatch area was used for the packagingof goods for delivery and the processing ofgoods received at the factory. <strong>The</strong> first floor ofthe main building was used mainly for storageby <strong>ICL</strong> Tech. It had a variety of store roomsand other equipment including CNC millingand grinding machines. <strong>The</strong> second floor wasoccupied by <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics, <strong>ICL</strong> Tech and Stockline.It contained the personnel offices, training room,computer rooms, accounts department andboard room. <strong>The</strong> third floor was used for lightstorage by <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics and <strong>ICL</strong> Tech.<strong>The</strong> basement below the despatch areacreated from the open pit was used partly by<strong>ICL</strong> Tech for the storage of components thatwere no longer in use, but primarily by AndrewGalloway and Kenneth Murray for storageof building tools, equipment and materials.<strong>The</strong>y had been employed by <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics sincearound 1987 as handymen, mostly doingmaintenance work. <strong>The</strong> ceiling of the basementwas the steel plate that formed the floor of thedespatch area.In the basement there was a fireproof storethat Andrew Galloway and Kenneth Murrayhad built around 1996-1998. In the area ofthe fireproof store there was reinforcement ofthe steel ceiling. Between the steel beams thatsupported the steel ceiling there were concretelintels. <strong>The</strong>se were cemented onto the beams onthe underside of the steel floor.<strong>The</strong>re was an opening between the groundfloor and the basement through the steel floorwhere the base of the shot blasting machine,located in the coating shop, extended intothe basement. Occasionally access to thebasement was required to clean and repair themachine.History of the fabrication shopSome years before the explosion <strong>ICL</strong> Plasticsacquired on behalf of <strong>ICL</strong> Tech a modern,rectangular single-storey portal-framed steelstructure with an asbestos sheeted roof andexternal brick wall panels to the north ofGrovepark Mills. It was then known as <strong>The</strong>Scooter Centre. It had about two-thirds of thearea of the main building. <strong>ICL</strong> Tech moved itsfabrication operations into it from the first floorof the main building.<strong>The</strong> fabrication shop was where the shaping,drilling, cutting and welding of plastics andmetals took place. Wood was also cut to makemoulds, jigs and frames. A wide variety ofmachinery was used to perform these functions.<strong>The</strong> fabrication shop was accessed from theback yard security door. At the entrance therewas a receiving area for stock and materials.<strong>The</strong>re was also a cabinet there which storedvarious chemicals. <strong>The</strong>re were two electricovens in the fabrication shop.<strong>The</strong> only LPG that was used in the fabricationshop was in a flamer that worked off apropane bottle. <strong>The</strong> bottle was kept in acubicle. It was used about once a week forabout an hour. It was not used on the day ofthe explosion.History of the Stockline warehouseAt the time of the disaster, Stockline occupied thewarehouse next to the main building on a leasefrom <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics. <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics had bought thisfrom John Russell Joiners on 27 February 1981.This building survived the explosion.<strong>The</strong> main business of Stockline was thestorage and sale of bulk plastic sheeting. <strong>The</strong>warehouse had a small amount of machinery37

PART 5for cutting and altering sheets of plastic tocustomers’ specifications. At the time of thedisaster, all of the Stockline office staff workedin the main building.<strong>The</strong> yardTo the south side of the main building was atriangular shaped yard. A bulk storage tankfor LPG was located there at a distance ofabout 15.5 feet from the building. <strong>The</strong> tankwas connected to the underground piperunning beneath the yard that I have alreadydescribed. This pipe originally rose to enterthe main building above ground through abricked up window into the open pit area. Tocounter problems with flooding, the level of theyard was raised in 1973. As a result, the LPGpipework was covered over where it enteredthe building. I refer to this in greater detailelsewhere in this report.CoatingShopLPGOvenOriginalVoidDespatchAreaLPG SupplyPipeRaisedYardRampBuried LPGPipe EntryFigure 25 – Model of the Grovepark Mills premises38

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTChapter 10 – Calor and Johnston Oilsand the installation at the siteLPG was supplied to the Grovepark Mills site byCalor Gas Limited (Calor) between 1969 and1998 and by Johnston Oils Limited, trading as JGas, between 1998 and 2004.Calor Gas LimitedCalor have been one of the major UK nationalsuppliers of LPG since the fuel was first usedand have been supplying bulk tank installationssince the mid 1950s. Calor have played anactive part in setting technical standards. <strong>The</strong>yhave a substantial technical department.It has not been possible to ascertain theprecise events and procedures followed atthe Grovepark Mills premises. Calor’s generalpractice is as follows.Standard installation procedure for all premisesContracts are generally arranged by salesstaff who have knowledge of tank locationand installation requirements but no in-depthtechnical expertise. Technical queries arepassed to the technical department. During theinitial detailed discussion with the prospectivecustomer, the salesman would establish thepurpose of the LPG installation; whether Calorwas being asked to supply any appliances;and how much of the pipework, includingpressure regulators and isolation valves, theprospective customer wished Calor to supplyand install.<strong>The</strong> contractual arrangements made betweenCalor and the customer would determine theresponsibility for installation and maintenance.Normally, any part of an installation beyond,or downstream of, the vapour off take valve,would be the customer’s responsibility. Thiswould mean that the first stage regulator, itsfittings and all pipework between the firststage regulator and the appliances within thepremises would be the responsibility of thecustomer.This would all be set out in the initial contractualdocumentation.To calculate the size and number of the tanksrequired, and the size of the pipe required,it would be necessary to consider a numberof factors including the exact locations of theappliances, the gas input capacities of theappliance burners and their burning pressures,the pipe-run distances from the appliance tothe point of entry into the building and from thebuilding to the storage tank, and to allow for aminimum four weeks supply in the tank basedon usage.In accordance with regulations, the tankagewould have to be sited at a set distance fromthe nearest building, boundary, propertyline and any other fuel sources. <strong>The</strong>re wouldhave to be adequate access for the vehicledelivering the tank, for the tanker and for fireservice vehicles. <strong>The</strong> siting distances of tanksand other associated requirements are laiddown in various Health and Safety Executivepublications. <strong>The</strong> prospective customer and thesalesman would then agree on the position ofthe tank site.<strong>The</strong> salesman would then sketch the installationand price the work agreed. <strong>The</strong> salesmanwould produce a specification and list ofmaterials, and a contract. On agreement andacceptance of the proposal by the customer, acontract would be completed and signed.<strong>The</strong> Sales Force Manual prepared by Calorprovides sales staff with instructions that they39

PART 5are to follow. <strong>The</strong> Manual instructs sales staff torefer to the technical staff where the installationis not straightforward. Every proposedinstallation involves a drawing.If Calor were to install any pipework, anyrelated drawings would indicate the pipeworkroute, its termination and tank location. <strong>The</strong>drawings would show all measurements. Beforeprogramming an installation, the salesman’spaperwork and drawing would be checkedby a member of Calor’s Technical ServicesDepartment. Further checks would be carriedout by the fitter installing the tank and by thetank delivery driver, both of whom would visitthe site with a site drawing.<strong>The</strong> fitting of LPG bulk installationsCalor have regional fitters who carry out LPGinstallations. A standard installation in noncommercialpremises would comprise the tank,first stage regulator, second stage regulator ifrequired, external pipework, isolation valve,and internal pipework to point of usage. <strong>The</strong>extent of Calor’s involvement in the installationoverall depends on the terms of the agreement.Calor work to HS(G)34 guidelines and to theLPGA Codes of Practice/British Standards andtheir own specifications. In the absence of anyformal procedures and guidelines, as was theposition in the 1960s, Calor drew up theirown guidelines. With a new installation, safetyinformation and an emergency service cardwould be provided to the customer.For a new installation in commercial premises,Calor would now generally provide a tankand a first stage regulator and offer to installthe pipework to the exterior wall of thebuilding.<strong>The</strong> ownership of, and responsibility for, thepipework depends on the individual contractbetween Calor and the customer. If thecustomer is required to lay pipes, the onus willbe on the customer to follow the specificationprovided by Calor. If requested, Calor can laythe pipes.Calor will connect to existing pipework onlyafter inspecting and pressure testing thepipework.Calor normally retains ownership of a tank andleases it to the customer. All other items suppliedby Calor are sold to the customer. Calor wouldsell tanks only in exceptional circumstances. Byretaining ownership, Calor ensures that the tanksare tested under their testing regime. Testingtanks is mandatory. <strong>The</strong> test dates are displayedon the tanks.Having agreed the siting of the tank, thecustomer would be required to lay a solidconcrete tank base of prescribed dimensions.In the case of a 2-tonne tank, this would be 12feet by 6 feet by 6 inches. <strong>The</strong> customer wouldbe informed of the dimensions and the route ofthe trench for the underground pipework fromthe tank base to the pipe entry point at thewall of the building. Calor would deliver thetank and place it onto the concrete base andinstall the vapour off-take valve on the tank andthe vapour off take pipe as far as ground leveladjacent to the trench where the undergroundpipe would be laid. <strong>The</strong> tank would bedelivered tested onto the base.To activate the delivery of a tank, the customerwould notify Calor when the base had beenprepared and the trench opened. If Calor hadcontracted to do so, the Calor fitter would install40

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORTthe necessary equipment, pipe and fittings. Ifpart of the pipework had been installed by thecustomer, the tank would not be commissionedfor use until the Calor fitter had carried out asoundness test on the entire installation. If Calorhad fitted the customer’s internal pipework, Calorwould normally check the soundness of thepipework in 2 stages - from the tank to the firststage regulator and from the first stage regulator tothe customer’s appliance. A pressure gauge wouldbe fitted to the customer’s appliance to monitorthe test. Once the customer’s entire installationwas completed, Calor would commission thetank. Only then could the tank be filled withgas. Bulk tanks to be installed would sometimescontain 50 litres of gas to enable the fitter tocarry out a pressure test and to commission thetank. A soap test of all joints would be carriedout. If any leaks became apparent, these wouldbe repaired by the tank fitter. During installationand commissioning of the system, safety signswould be located in close proximity by the fitter.Emergency contact numbers would also beprovided. <strong>The</strong>reafter, gas would be delivered tothe tank.Once the tank and pipework had beeninstalled, the customer would be given a safetyleaflet explaining the arrangements for pipeworkinspection. A 5-year inspection of the pipeworkis currently recommended, tying in with the5-year tank inspection. This would include apressure test. Excavation of pipework would beconsidered necessary only if a problem or aleak had been reported.Periodic testingCalor carry out 5-, 10- and 20-year tests ontheir bulk tanks. A 5-year test involves a visualinspection and, until more recently, a changeof the pressure relief valve. No soundness teston the pipework is carried out at the 5-yeartest. A 10-year test involves an ultrasonic testto measure the thickness of the metal at variouspoints of the tank. <strong>The</strong> pressure relief valve ischanged at this time. <strong>The</strong>re is also a soundnesstest of the pipework between the tank andthe emergency control valve. A 20-year testinvolves either an exchange of the tank or anenhanced in-service test which involves the testscarried out at 10 years and tests of the valvesand pipework on the tank itself. A soundnesstest is also carried out. It is open to customersat any time to request Calor to carry out asoundness test of their pipework. <strong>The</strong> cost ofsuch a test is charged to the customer.<strong>The</strong> filling of tanksOnly Calor can fill Calor tanks. This is a termof their contract with the customer. Deliveriesof gas made by Calor require the deliverydriver to complete a Bulk Installation Defect<strong>Report</strong> (BIDR). If the driver has encountered anydifficulties, he is required to contact Calor’semergency response immediately to have anengineer sent to the site.Installation of LPG pipework in basement areasSince LPG is heavier than air, Calor state thatthey would not knowingly connect pipework toan appliance in a basement or pit. Where itwas necessary for pipework to be installed in abasement, it would not be approved by Calorunless there were appropriate safety measuresin place, such as having as few joints aspossible, having gas detection equipment, andhaving the pipe protected against mechanicaldamage.41

PART 5Johnston Oils Limited trading as JGasJohnston Oils Limited (Johnston Oils) is aprivately owned supplier of fuels. It also tradesunder the name J Gas. <strong>The</strong> company is basedin Bathgate and has been trading for 40 years.Johnston Oils supplied gas to the GroveparkMills site from 1998 to the date of the disaster.<strong>The</strong> contract between Johnston Oils and <strong>ICL</strong>Plastics<strong>The</strong> supply of LPG by Johnston Oils to <strong>ICL</strong>Plastics began on 22 April 1998. <strong>The</strong> termsand conditions of the supply are set outin a document dated 10 February 1998.<strong>The</strong>y provided that the risk in the productsdelivered would pass to the buyer immediatelyupon delivery. Condition 3(c) provided thatJohnston Oils were responsible for insurance,maintenance and testing of tanks, regulatorsand pipework supplied. <strong>The</strong> pipework wasalready in situ when Johnston Oils took over thesupply. <strong>ICL</strong> Plastics drew up a diagram whichwas attached to the agreement showing wherethe tank was and where access could begained by Johnston Oils’ delivery vehicles.Under the bulk supply agreement, if thecustomer moved to another gas supplier thepipework would remain the responsibility ofthe customer. Johnston Oils considered that,as new suppliers taking over an existinginstallation under their agreement, they wouldbe responsible for the pipes only up to thefirst stage regulator. <strong>The</strong>re was nothing in theUKLPG Guidelines issued at that time thataffected the position. <strong>The</strong> industry practice wasthought always to have been, and to continueto be, that the responsibility for pipework restedwith the owner or the customer. HSE guidancewas interpreted as supporting that view.When Johnston Oils took over the supplythey carried out a soundness test. Neither <strong>ICL</strong>Plastics nor <strong>ICL</strong> Tech asked Johnston Oils toinspect the pipework. If either had, JohnstonOils would have carried out a risk assessmentand investigated the type of pipes being usedat the site, their location and their estimatedage. Given the nature of the pipework,Johnston Oils would have recommended thatit be replaced. This would have been doneby Johnston Oils only on receipt of a writteninstruction.Johnston Oils were never aware of any problemwith the pipework at Grovepark Mills. If a driverhad reported any problem with the pipeworkdownstream of the first stage regulator, hewould have been instructed to turn off the gas.<strong>The</strong> customer would have then been contactedand advised to have repairs carried out to thepipework. If the customer had asked JohnstonOils Ltd to carry out the repairs, they wouldhave done so.Mr Alan Elliott of Johnston Oils consideredthat LPG pipework should not be installed ina basement or open void. He considered thatif such pipework existed, it should be subjectto a risk assessment. He did not know thatthe pipework from the tank was routed belowground into and through the basement. If hehad known of this, he would have advised <strong>ICL</strong>Plastics to dig up the buried pipework becausethat would be the only way to establish its typeand condition.Regular inspectionsJohnston Oils had a written scheme ofinspection for bulk tanks. This was Johnston Oils’standard specification for all installations.42

THE <strong>ICL</strong> REPORT<strong>The</strong> annual testing and inspection of thevalves and fittings of a tank was a commonpractice. Johnston Oils issued their drivers witha checklist, which was returned to the mainJohnston Oils’ offices once tests had beencompleted. If a leak was identified, the normalpractice was that the delivery driver contactedJohnston Oils’ headquarters.Past practice dictated that at every 5-yearexamination the pressure relief valve wouldbe replaced. Research carried out by Calorin conjunction with HSE concluded that thereasonable life of the valve was 10 years. Asa result the industry changed its practice toreplacement every 10 years rather than every 5years. <strong>The</strong> replacement of the valve had nothingto do with the integrity of the tank itself. After20 years the tank would be refurbished.Johnston Oils’ tanker drivers carried out annualinspections of the bulk tank on 8 August 2001,10 June 2002 and 9 June 2003. <strong>The</strong> tankwould have been inspected and the valves andfittings leak tested, but there was no testing ofthe pipework. <strong>The</strong>re was no indication that a5-year examination of the tank was carried out.Other circumstances relating to theLPG installation at Grovepark MillsAt some point before the disaster, twoadditional 47 kg LPG cylinders were fitted toa branch in the pipework which led from thetank to the first stage regulator. <strong>The</strong>y providedback-up if the LPG in the tank ran out. It is notknown who fitted those cylinders. <strong>The</strong> presenceof these cylinders did not play any part in thecausation of the explosion.43