Epipelic diatoms from an extreme acid environment - Earth and ...

Epipelic diatoms from an extreme acid environment - Earth and ...

Epipelic diatoms from an extreme acid environment - Earth and ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Epipelic</strong> <strong>diatoms</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>an</strong> <strong>extreme</strong> <strong>acid</strong> <strong>environment</strong>: BeowulfSpring, Yellowstone National Park, U.S.A.William O. Hobbs* 1 , Alex<strong>an</strong>der P. Wolfe 1 , William P. Inskeep 2 , Larry Amskold 1 & KurtO. Konhauser 11Department of <strong>Earth</strong> & Atmospheric SciencesUniversity of AlbertaEdmonton, AB T6G 2E3C<strong>an</strong>ada2 Department of L<strong>an</strong>d Resources & Environmental SciencesMont<strong>an</strong>a State UniversityBozem<strong>an</strong>, MT 59717USA*author for correspondence (whobbs@ualberta.ca)1

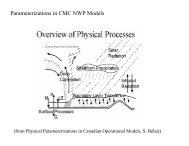

161718192021222324IntroductionAlthough <strong>diatoms</strong> have been shown to respond to temperature in culture (Patrick, 1977;Suzuki & Takahashi, 1995), it remains uncertain whether they are directly thermophilousin <strong>an</strong> eco-physiological sense, or indirectly influenced by <strong>environment</strong>al conditions thatcovary with climate (Anderson, 2001; Wolfe, 2002). The bulk of previous studies on<strong>diatoms</strong> <strong>from</strong> hot spring <strong>environment</strong>s has focused solely on temperature (Hustedt, 1937-1938; Stockner, 1967; Brock & Brock, 1966), with some attention to the influences oflow ambient pH <strong>an</strong>d elevated concentrations of potentially toxic elements, such as arsenic(As) <strong>an</strong>d copper (Cu) (Hargreaves et al., 1975; Whitton & Diaz, 1981).25262728293031323334353637In this paper, we present <strong>an</strong> account of the diatom flora <strong>from</strong> the Beowulf Spring in theNorris Geyser Basin, Yellowstone National Park (YNP). This epipelic communityinhabits As-rich hydrous ferric oxide (HFO) mats that coat the s<strong>an</strong>dy substratum of thespring proximal to the vent (Figure 1). Peripheral to the HFO zone, a green algal matcomposed of cy<strong>an</strong>idiaceous Rhodophyta contains few, if <strong>an</strong>y, <strong>diatoms</strong>. Light & sc<strong>an</strong>ningelectron microscopic (SEM) investigations of these communities are presented <strong>from</strong> bothuncle<strong>an</strong>ed <strong>an</strong>d oxidized materials. Water chemistry implies that the <strong>diatoms</strong> areexploiting <strong>an</strong> ecological niche that may be toxic to other algae. Contrary to Villeneuve &Pienitz’s (1998) suggestion that there is no single diatom assemblage typical of thermalsprings, our study suggests a strong floristic similarity among highly <strong>acid</strong>ic hot springsglobally (Hustedt, 1937-1938; Carter, 1972; Hargreaves et al., 1975; Whitton & Diaz,1981; Cassie & Cooper, 1989; Wat<strong>an</strong>abe & Asai, 1995; DeNicola, 2000; Jord<strong>an</strong>, 2001),3

3839implying that indeed there exists a distinct but biogeographically-disjunct flora in these<strong>extreme</strong> <strong>environment</strong>s.4041424344454647484950515253MethodsBeowulf Hot Spring (44°43’53” N, 110°42’41” W) lies within the Norris Geyser Basin,Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, U.S.A. (YNP Thermal Inventory #NHSP35))(Fig. 1A). Surface sediment collections were obtained <strong>from</strong> both the central portion of thespring, which is coated by HFO, <strong>an</strong>d peripheral green algal mats (Fig. 1B). Samples wereeither cle<strong>an</strong>ed using 30% H 2 O 2 , or mounted uncle<strong>an</strong>ed following dilution of the slurry indeionized water. Valves were mounted in Naphrax <strong>an</strong>d observed at 1000x under oilimmersion with differential interference contrast optics (Leica DMLB). For sc<strong>an</strong>ningelectron microscopy (SEM), slurry was evaporated onto stubs at room temperature in adesiccator, prior to sputter-coating with Au, <strong>an</strong>d examination in a JEOL-6301F fieldemissionSEM. Archives of these samples are kept at 4 o C at the University of Alberta.Our results confirms that it is clearly adv<strong>an</strong>tageous to examine both cle<strong>an</strong>ed <strong>an</strong>duncle<strong>an</strong>ed material (Stockner 1967).54555657585960Beowulf is considered <strong>an</strong> <strong>acid</strong>-sulfate-chloride spring, where the spring discharges<strong>extreme</strong>ly <strong>acid</strong>ic (pH50˚C) water, with mM concentrations of Na + , K + , Cl – ,SO 2- 4 <strong>an</strong>d Si (Figure 1; Table 1; Inskeep et al. 2004). Water samples were obtained bysyringe <strong>an</strong>d filtered through 0.45 µm in-line nylon syringe filters. Samples were further<strong>acid</strong>ified with TraceMetal-grade HNO 3 <strong>an</strong>d kept refrigerated until <strong>an</strong>alysis by ionchromatography. Temperature <strong>an</strong>d pH were measured in the field using a digital4

6162thermometer <strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong> Orion Ross (8165BN) pH meter calibrated between 2 <strong>an</strong>d 4,respectively.6364656667686970717273747576Results <strong>an</strong>d DiscussionWater chemistryThe Beowulf Spring has <strong>an</strong> ionic strength of 0.02 M, which is comparable to a marine –brackish estuarine salinity classification (Juggins, 1992). Aqueous chemistry <strong>from</strong>Beowulf Spring has been characterized on multiple occasions <strong>an</strong>d exhibits very littler<strong>an</strong>ge in concentrations (±10% or less for most constituents; Inskeep et al., 2004). Thewater chemistry reveals the presence of potentially toxic metals to algal growth, namelyCu <strong>an</strong>d As (Table 1). In particular, As concentrations reach 20 µM, much higher th<strong>an</strong>minimum concentrations required to inhibit growth of <strong>diatoms</strong> in culture (Saunders &Riedel, 1998). Similarly, Beowulf Cu concentrations are two to three orders of magnitudegreater th<strong>an</strong> those used by Saunders & Riedel (1998). Thus, natural concentrations of As<strong>an</strong>d Cu in the Beowulf Spring approach or exceed those <strong>from</strong> the most highly impacted<strong>acid</strong>-mine drainages (Whitton & Diaz, 1981; Verb & Vis, 2000).77787980818283While it is not our intention to speculate as to whether there is active uptake of As by<strong>diatoms</strong> in Beowulf Spring, As uptake is likely occurring among other microorg<strong>an</strong>isms inYNP hot springs, namely bacteria (L<strong>an</strong>gner et al., 2001; Inskeep et al., 2004).Metabolism of As by marine algae is hypothesized to occur because of the molecularsimilarity between phosphorous <strong>an</strong>d As (Edmonds & Fr<strong>an</strong>cesconi, 1998). Generalpathways of metals metabolism by algae include sequestration, complexation with5

848586exuded dissolved org<strong>an</strong>ic carbon, <strong>an</strong>d redox tr<strong>an</strong>sformations during uptake (Saunders &Riedel, 1998). Thus, a r<strong>an</strong>ge of biogeochemical processes exist to allow not only thesurvival, but indeed the success, of algae inhabiting these <strong>extreme</strong> <strong>environment</strong>s.87888990919293The pH of Beowulf Spring at the time of sampling was 2.26, <strong>an</strong>d the temperature was67 o C. A number of diatom communities have been documented at pH of

107108(Asada & Tazaki, 2001), is identical to our observations <strong>from</strong> the Beowulf material (Fig.1C-D).109110111112113114115116117118119120121122123124125Brown matsThe HFO mat contained abund<strong>an</strong>t <strong>diatoms</strong> that occur as solitary epipelic forms. Allobserved specimens are biraphid taxa, hence capable of motile displacement within themat. Several specimens preserved intact chloroplasts when viewed in LM. SEM revealeddiatom surfaces both completely free of secondary silica precipitates <strong>an</strong>d with cle<strong>an</strong>areolae (Fig. 1E & F), as well as thoroughly Si-encrusted specimens (Fig. 1G & H). Inthe latter inst<strong>an</strong>ces, inorg<strong>an</strong>ic Si precipitation has formed a continuous botryoidal coating,comprised of coalescent individual papillae of approximately 100 nm diameter. Wehypothesize that living <strong>diatoms</strong> have cle<strong>an</strong>er valve surfaces th<strong>an</strong> dead ones, <strong>an</strong>d perhapsthat inorg<strong>an</strong>ic silica precipitation may at times overwhelm living cells. Inskeep et al.(2004) have provided a complete characterization of the brown mat, revealing a variety ofSiO 2 crystalline polymorphs <strong>an</strong>d microbial communities encrusted with As-rich HFO. Itis unclear to us at this time what aspect of the HFO mat contributes to the success of the<strong>diatoms</strong> living there, in sharp contrast to their absence in the green mat. Given thatCy<strong>an</strong>idiaceae are virtually absent in the HFO mats, it is also possible that resourcecompetition plays a role in delimiting these algae.126127128129Floristic descriptionThe epipelic diatom community in Beowulf Spring consisted of five species (Table 1).The domin<strong>an</strong>t diatom taxon was Nitzschia cf. thermalis var. minor Hilse (56%), followed7

130131132133134135in decreasing order of relative abund<strong>an</strong>ce by Pinnularia acoricola Hustedt (21%),Eunotia exigua (de Brébisson ex Kützing) Rabenhorst (15%), Nitzschia ovalis Arnott(7%) <strong>an</strong>d Encyonema minutum (Hilse ex Rabenhorst) D.G. M<strong>an</strong>n (

153154155156157158159160161162163164165apiculate ends, tr<strong>an</strong>sapical striae composed of fine areolae, <strong>an</strong>d a constricted centralmargin (Figs. 3A-E). REM of N. homburgiensis <strong>an</strong>d the isotype material of N. thermalisvar. minor Hilse reveal that the fibulae are irregular, widely spaced, <strong>an</strong>d c<strong>an</strong> extend to thecenter of the tr<strong>an</strong>sapical axis (Plate 39 of L<strong>an</strong>ge-Bertalot, 1978). Comparatively, thefibulae <strong>from</strong> Beowulf specimens r<strong>an</strong>ge in thickness <strong>from</strong> 0.5 to 1.0 µm along the apicalaxis (Fig. 2C) <strong>an</strong>d are confined to the margin of the valve. In addition the raphe of ourspecimens is more eccentric th<strong>an</strong> that of N. homburgiensis (Fig. 3B). Cassie (1989)illustrated N. umbonata <strong>from</strong> a shallow thermal pool (Tok<strong>an</strong>nu, New Zeal<strong>an</strong>d) withsimilar fibulae <strong>an</strong>d raphe structures to Beowulf specimens, but associated withsignific<strong>an</strong>tly larger valves (36-45 µm). Morphometric comparisons of N. cf. thermalisvar. minor, N. hombergiensis, N. umbonata, N. steynii Cholnoky emend. (Schoem<strong>an</strong> &Archibald, 1988), <strong>an</strong>d N. rimosa M<strong>an</strong>guin (Bourelly & M<strong>an</strong>guin, 1952) indicate that eachof these taxa has a distinctive morphology (Table 2).166167168169170171172173174175Further questions arise in considering the ecologies of these <strong>diatoms</strong>. L<strong>an</strong>ge-Bertalot(1978) associates N. homburgiensis with circumneutral, unpolluted freshwaters, includingthe Arctic, whereas N. umbonata inhabits both polluted localities <strong>an</strong>d, moreover, hotsprings. From a strictly ecological st<strong>an</strong>dpoint, specimens <strong>from</strong> Beowulf have far closeraffinity to L<strong>an</strong>ge-Berlatot’s (1978) N. umbonata. Because the combination thermalis var.minor predates all of the potentially equivalent taxa (<strong>an</strong>d/or closely-allied forms), wehave identified the Beowulf specimens as Nitzschia cf. thermalis var. minor Hilse. At thispoint, <strong>an</strong>d pending further <strong>an</strong>alysis, we feel that proposing a new name would onlyfurther confuse nomenclatural issues within the ‘N. thermalis’ complex. There appear to9

176177178be no similar specimens held in the collections of either the C<strong>an</strong>adi<strong>an</strong> Museum of Natureor the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences (P.B. Hamilton & M.B. Edlund, pers.comm.).179180181182183184185186187188189190191192193194195Nonetheless, it is clear that <strong>diatoms</strong> of the N. umbonata-thermalis cluster occur in <strong>an</strong>umber of locations in Europe <strong>an</strong>d N. America that have <strong>extreme</strong> water chemistries. Forexample, Whitton & Diaz (1981) recorded N. thermalis at <strong>acid</strong> mine drainage sites withpH between 3 <strong>an</strong>d 4 in the U.K. <strong>an</strong>d Belgium. Stockner (1967) noted the presence of N.thermalis in alkaline hot springs (>35 o C) situated in Mount Rainier, Washington, USA,but not in similar springs <strong>from</strong> the Upper Geyser Basin, YNP, suggesting that this speciesis not necessarily <strong>acid</strong>obiontic. It should be noted that N. thermalis is larger <strong>an</strong>d has nocentral interruption of the fibulae, in contrast to our specimens <strong>an</strong>d N. thermalis var.minor sensu Hilse (V<strong>an</strong> Heurck, 1880-1885), though both nominate <strong>an</strong>d varietal formsseem to occur in similar <strong>environment</strong>s. Weed (1889) found specimens of Denticulathermalis Kütz. in hot springs of the Pelic<strong>an</strong> Creek area in YNP, which he may haveconfused with <strong>an</strong>y number of Nitzschia. From our extensive literature survey, it appearsthat Nitzschia cf. thermalis var. minor is not widespread in hot springs (Copel<strong>an</strong>d, 1936;Stockner, 1967; Whitton & Diaz, 1981; Villeneuve & Pienitz, 1998; DeNicola, 2000).This may suggest that N. cf. thermalis var. minor may be restricted to only the hottestsprings of high ionic strength <strong>an</strong>d greatest <strong>acid</strong>ity.196197198Pinnularia acoricola Hustedt (Figs. 2K-M & 3G-I)Length: 11-17.5 µm10

199200201202203204205206207208209210Width: 2.5-3.5 µmStriae / 10 µm: 13-17P. acoricola has a l<strong>an</strong>ceolate to slightly oval valve morphology, with broadly roundedapices. The striae are strongly convergent at the poles <strong>an</strong>d radial in the central area. Thecentral area is either rounded or interrupts striae extending to the valve margin. Theexternal distal ends of the raphe are hooked in the opposite direction to the proximalends. DeNicola (2000) discusses the misidentification of P. acoricola as P. obscura, <strong>an</strong>dsimilarities to P. chapm<strong>an</strong>i<strong>an</strong>a. However, neither of these species c<strong>an</strong> be consideredsynonyms to P. acoricola. Our specimens, examples of which are shown both in LM(Figs. 2K-M) <strong>an</strong>d SEM (Figs. 3G-I), are consistent with detailed descriptions <strong>an</strong>d lightmicrographs offered by Carter (1972), Krammer & L<strong>an</strong>ge-Bertalot (1986) <strong>an</strong>d Wat<strong>an</strong>abe& Asai (1995).211212213214215216217218219220221P. acoricola has been observed in a number of <strong>acid</strong>ic waters globally (Hustedt, 1937-1938; Carter, 1972; Hargreaves et al., 1975; Whitton & Diaz, 1981; Cassie & Cooper,1989; Wat<strong>an</strong>abe & Asai, 1995; DeNicola, 2000; Jord<strong>an</strong>, 2001). From the literature, itseems clear that this species is endemic to highly <strong>acid</strong>ic <strong>environment</strong>s, namely hotsprings <strong>an</strong>d <strong>acid</strong> mine drainage. The pH of waters in which it has been observed r<strong>an</strong>ges<strong>from</strong>

222223224225concentrations of Cu <strong>an</strong>d Zn in Beowulf Spring are four orders of magnitude lower(Table 1). It is also noted that P. acoricola has been documented in close association withCy<strong>an</strong>idium caldarium elsewhere, in both hot springs (Whitton & Diaz, 1981) <strong>an</strong>dendolithic habitats (Hernández-Chavarría & Sittenfeld, 2006).226227228229230231232233234235236237238Eunotia exigua (de Brébisson ex. Kützing) Rabenhorst 1864 (Figs. 2A-E & 3J-L)Length: 8-31 µmWidth: 3-5 µmStriae / 10 µm: 16-25Valves are crescent-shaped <strong>an</strong>d isopolar, with ends capitate to rostrate, the ventral marginis slightly concave. Striae are punctate <strong>an</strong>d tr<strong>an</strong>sapical. Raphe is short, located on theventral margin of the m<strong>an</strong>tle, <strong>an</strong>d occasionally migrate to the valve face distally with acurved terminal fissure (Fig. 3J), where it terminates internally in a helictoglossa (Fig.3L). A single rimoportula occurs at one pole of each valve. There is considerablevariability in the morphology of Eunotia exigua, which has led to the reference of thespecies as a complex or ‘E. exigua sensu lato’ (Krammer & L<strong>an</strong>ge-Bertalot, 1991;DeNicola, 2000).239240241242243244Eunotia exigua is truly a cosmopolit<strong>an</strong> species, present in lakes, ponds, bogs <strong>an</strong>d hotsprings <strong>from</strong> tropical to arctic regions (Scherer, 1981; Whitton & Diaz, 1981; Round,1991; DeNicola, 2000; Joynt & Wolfe, 2001). E. exigua is <strong>an</strong> <strong>acid</strong>obiontic taxa occurringalmost exclusively in <strong>acid</strong>ic <strong>environment</strong>s, <strong>an</strong>d having a pH optimum

245246<strong>acid</strong> mine drainage. Furthermore, concentrations of Cu <strong>an</strong>d Zn >100 mg l -1 did notimpede the diatom’s viability.247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261262263Nitzschia ovalis Arnott (Figs 2I-J & 3F)Length: 12-20.5 µmWidth: 3.5-5 µmFibulae / 10 µm: 12-14Valves are elliptical with rounded apices. Striae are fine <strong>an</strong>d generally unresolvable inlight microscopy (Figs. 2I-J) <strong>an</strong>d require SEM to reveal their morphology (Fig. 3F).There is no central area or nodule, <strong>an</strong>d fibulae are regularly spaced on the valve marginwith no central interruption. The raphe structure is peripheral <strong>an</strong>d not visible in LM.There is potential for misidentification of N. ovalis as N. communis Rabenhorst, <strong>an</strong>d viceversa (DeNicola, 2000). The morphology of N. communis is slightly narrower, <strong>an</strong>d striaeare more evident under LM. Nitzschia ovalis also shares features with N. pusilla Grunowemend. L<strong>an</strong>ge-Bertalot <strong>an</strong>d N. aurariae Cholnoky, both of which are narrower <strong>an</strong>d, in thecase of N. pusilla, exhibits slightly rostrate apices (Krammer & L<strong>an</strong>ge-Bertalot, 1988;DeNicola, 2000). The Beowulf specimens of N. ovalis are consistent with both typematerial in V<strong>an</strong> Heurck (1880-1885) <strong>an</strong>d Europe<strong>an</strong> specimens described <strong>an</strong>d illustratedby Krammer & L<strong>an</strong>ge-Bertalot (1988).264265266267Very few records of N. ovalis exist for freshwater <strong>environment</strong>s despite its originaldescription as a continental species. However, there are a number of marine accounts forthis diatom, <strong>an</strong>d it has been referred to as <strong>an</strong> estuarine benthic taxon (Saks, 1982).13

268269270271272273Laboratory work showed that optimal growth occurred in waters of high ionic strength(i.e., 0.03 M) <strong>an</strong>d the cultures tolerated temperatures up to 36 o C (Saks, 1982). Itspresence in Beowulf Spring most likely relates to the high ionic strength of the water,coupled to broad toler<strong>an</strong>ces with respect to pH. Other reported occurrences of N. ovalis infreshwaters seem to be restricted to <strong>acid</strong> mine drainage in the U.K. (Hargreaves et al.,1975).274275276277278279280281282283284285286287288289290ConclusionsThe <strong>extreme</strong> conditions of Beowulf Spring reduce algal diversity to taxa with toler<strong>an</strong>ce oflow pH, high ionic strength, <strong>an</strong>d elevated concentrations of aqueous metals that areinhibitory or toxic to other groups. Clear zonation between cy<strong>an</strong>idiace<strong>an</strong> (green) <strong>an</strong>ddiatom (brown) mats within the Beowulf Spring show that the habitat is furthersubdivided spatially (Figure 1). The possibility of competitive exclusion between thehabitats occupied by either group c<strong>an</strong>not be dismissed, all the more as both groups appearto metabolize silica actively. <strong>Epipelic</strong> <strong>diatoms</strong> <strong>from</strong> the brown mats in Beowulf Spring,<strong>an</strong>d their close affinities with other hot-spring assemblages, raise several interestingquestions concerning the ecophysiology <strong>an</strong>d biogeography of <strong>diatoms</strong>. It appears that thealgae in the Beowulf system are not merely surviving <strong>extreme</strong> <strong>environment</strong>al conditionsbeyond the toler<strong>an</strong>ces of other forms, but potentially deriving benefits <strong>from</strong> certainaspects of this habitat. Low diatom diversity <strong>an</strong>d hence reduced inter-specificcompetition, coupled to the absence of predators, are obvious factors that may contributeto the success of this community. The potential metabolism of toxic metals by these<strong>diatoms</strong> must also be considered, <strong>an</strong>d this merits further investigation. The apparent14

291292293294295296297298active silica metabolism of Cy<strong>an</strong>idiaceae may provide considerable phylogenetic insight,given the relationship between <strong>diatoms</strong> <strong>an</strong>d red algae (Keeling et al. 2004). In terms ofbiogeography, two of the <strong>diatoms</strong>, Pinnularia acoricola <strong>an</strong>d Nitzschia cf. thermalis var.minor, appear almost exclusively associated with hot-springs, whereas <strong>an</strong>other, N. ovalis,is halophilous, <strong>an</strong>d a fourth, Eunotia exigua, is <strong>an</strong> <strong>acid</strong>obiont that inhabits <strong>acid</strong>-minedrainages <strong>an</strong>d naturally-<strong>acid</strong>ic <strong>environment</strong>s with equal facility. It remains a mystery howsuch disjunct associations have emerged. Together, our observations provide strongincentives to more thoroughly catalog the diatom floras of YNP springs.299300301302303304305306307308309AcknowledgmentsWe th<strong>an</strong>k the National Park Service (Department of the Interior) for permission toconduct research in Yellowstone National Park. We also th<strong>an</strong>k Stef<strong>an</strong> Lalonde forsampling <strong>an</strong>d laboratory support. Drs. Paul Hamilton <strong>an</strong>d Mark Edlund graciouslyconfirmed the lack of Nitzschia cf. thermalis var. minor in the herbariums of theC<strong>an</strong>adi<strong>an</strong> Museum of Nature <strong>an</strong>d the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences,respectively. Research was supported by the Natural Sciences <strong>an</strong>d Engineering ResearchCouncil of C<strong>an</strong>ada (NSERC) <strong>an</strong>d the National Science Foundation (NSF MicrobialObservatory). This paper is dedicated to Dr. Eugene Stoermer for his enormouscontribution to diatom research.31015

310311312ReferencesANDERSON, N.J. (2001): Diatoms, temperature <strong>an</strong>d climatic ch<strong>an</strong>ge. – Eur. J. Phycol.35: 307-314.313314315ASADA, R. & K. TAZAKI (2001): Silica biomineralization of unicellular microbesunder strongly <strong>acid</strong>ic conditions. – C<strong>an</strong>. Mineralogist 39: 1-16.316317318BROCK, T.D. & M.L. BROCK (1966): Temperature optima for algal development inYellowstone <strong>an</strong>d Icel<strong>an</strong>d hot springs. – Nature 209: 733-734319320321322BOURELLY, P. & E. MANGUIN, (1952) Algues d’eau douce de la Guadaloupe etdépendences. – Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique: 1-281. Soc. d’editiond’Enseignements Sup.,Paris.323324325CARTER, J.R. (1972): Some observations on the diatom Pinnularia acoricola Hustedt. –Microscopy 32: 162-165326327328CASSIE, V. (1989): A contribution to the study of New Zeal<strong>an</strong>d <strong>diatoms</strong>. - BibliothecaDiatomologica, B<strong>an</strong>d 17: 1-266. J Cramer, Berlin.329330331CASSIE, V. & R.C. COOPER (1989): Algae of New Zeal<strong>an</strong>d thermal areas. -Bibliotheca Phycolologica B<strong>an</strong>d 78: 1-261. J. Cramer, Berlin.33216

333334CHARLES, D. F. (1985): Relationships between surface sediment diatom assemblages<strong>an</strong>d lakewater characteristics in Adirondack lakes. - Ecology 66: 994–1011.335336337338COMPÈRE, P. & A. DELMOTTE (1986): Diatoms in two hot springs in Zambia(Central Africa). – In: F.E. ROUND. Proceedings of the Ninth International DiatomSymposium: 29-40. Biopress Ltd., Bristol.339340341COPELAND, J.J. (1936): Yellowstone thermal Myxophyceae. – Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci.36: 1-232.342343344DENICOLA, D. (2000): A review of <strong>diatoms</strong> found in highly <strong>acid</strong>ic <strong>environment</strong>s. –Hydrobiol. 433: 111-122.345346347348EDMONDS, J.S. & K.A. FRANCESCONI (1998) Arsenic metabolism in aquaticecosystems. – In: W.J. LANGSTON & M.J. BEBIANNO (eds.) Metal Metabolism inAquatic Environments: 159-183. Chapm<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d Hall, London.349350351352FOURNIER, R.O. (1985): The behaviour of silica in hydrothermal solutions. – In: B.R.BERGER & P.M. BETHKE (eds.) Geology <strong>an</strong>d Geochemistry of Epithermal Systems:45-61. Reviews in Economic Geology Vol. 2.353354355HARGREAVES, J.W., E.J.H. LLOYD & B.A. WHITTON. (1975): Chemistry <strong>an</strong>dvegetation of highly <strong>acid</strong>ic streams. – Freshwat. Biol. 5: 563-576.17

356357358359HERNÁNDEZ-CHAVARRÍA, F. & A. SITTENFELD. (2006): Preliminary report on the<strong>extreme</strong> endolithic microbial consortium of ‘Pailas Frías’, ‘Rincón de la Vieja’Volc<strong>an</strong>o, Costa Rica. – Phycol. Res. 54: 104-107.360361362HUSTEDT, F. (1937-1938): Systematische und Untersuchungen über denDiatomeenflora von Java, Bali und Sumatra. – Arch. Hydrobiol., Suppl. 15 & 16.363364365366367INSKEEP, W.P., R.E. MACUR, G. HARRISON, B.C. BOSTICK & S.FENDORF(2004): Biomineralization of As(V)-hydrous ferric oxyhydroxide in microbial matsof <strong>an</strong> <strong>acid</strong>-sulfate-chloride geothermal spring, Yellowstone National Park. – Geochim.Cosmochim. Acta. 68: 3141-3155.368369370371372JORDAN, R.W. (2001): Taxonomy, morphology <strong>an</strong>d distribution of two Pinnulariaspecies <strong>from</strong> <strong>acid</strong>ic lakes <strong>an</strong>d rivers in Yamagata <strong>an</strong>d Miyagi Prefectures, NortheastJap<strong>an</strong>. – In: R.JAHN, J.P. KOCIOLEK, A. WITKOWSKI & P.COMPÈRE. Studies onDiatoms: L<strong>an</strong>ge-Bertalot Frestschrift: 279-302. A.R.G. G<strong>an</strong>tner Verlag K.G.373374375376JOYNT III, E.H. & A.P. WOLFE (2001): Paleo<strong>environment</strong>al inference models <strong>from</strong>sediment diatom assemblages in Baffin Isl<strong>an</strong>d lakes (Nunavut, C<strong>an</strong>ada) <strong>an</strong>dreconstruction of summer water temperature. – C<strong>an</strong>. J. Fish Aquat. Sci. 58: 1222-1243.37718

378379380JUGGINS, S (1992): Diatoms in the Thames Estuary, Engl<strong>an</strong>d: ecology, paleoecology,<strong>an</strong>d salinity tr<strong>an</strong>sfer function. - Bibliotheca Diatomologica, B<strong>an</strong>d 25: 1-216. J. Cramer,Berlin.381382383KEELING, P. J., J.M. ARCHIBALD, N.M. FAST, & J.D. PALMER (2004): Commenton ‘The evolution of modern eukaryotic phytopl<strong>an</strong>kton’. Science 306: 2191b.384385386KONHAUSER, K.O., B. JONES, V.R. PHOENIX, G. FERRIS & R.W. RENAUT(2004). The microbial role in hot spring silicification. Ambio 33: 552-558.387388389390KRAMMER, K. & H. LANGE-BERTALOT (1986): Bacillariophyceae 1. Teil:Bacillariophyceae. – In: H. ETTL, J. GERLOFF, H. HEYNIG & D. MOLLENHAUER(eds). Süßwasserflora Von Mitteleuropa 2. Fischer, Stuttgart.391392393394KRAMMER, K. & H. LANGE-BERTALOT (1988): Bacillariophyceae 2. Teil:Bacillariaceae, Epithemiaceae, Surirellaceae. – In: H. ETTL, J. GERLOFF, H. HEYNIG& D. MOLLENHAUER (eds). Süßwasserflora Von Mitteleuropa 2. Fischer, Stuttgart.395396397398KRAMMER, K. & H. LANGE-BERTALOT (1991): Bacillariophyceae 3. Teil:Centrales, Fragilariaceae, Eunotiaceae. – In: H. ETTL, J. GERLOFF, H. HEYNIG & D.MOLLENHAUER (eds). Süßwasserflora Von Mitteleuropa 2. Fischer, Stuttgart.39919

400401402LANGE-BERTALOT, H. (1978): Zur systematic, taxonomie und ökologie desabwasserspezifish wichtigen formenkreises um “Nitzschia thermalis”. – Nova Hedwigia30: 635-652.403404405406LANGNER, H.W., C.R. JACKSON, T.R. MCDERMOTT & W.P. INSKEEP (2001):Rapid oxidation of arsenite in a hot spring ecosystem, Yellowstone National Park. –Environ. Sci. Technol. 35: 3302-3309.407408409MANN, J.E. & H.E. SCHLICHTING (1967): Benthic algae of selected thermal springsin Yellowstone National Park. – Tr<strong>an</strong>s. Amer. Microsc. Soc. 86: 2-9.410411412PATRICK, R. (1977): Ecology of freshwater <strong>diatoms</strong>. – In:. Werner, D (ed).: TheBiology of Diatoms: 284-332. Bot<strong>an</strong>ical Monographs Vol.13. Blackwell, UK.413414415ROUND, F.E. (1991): Epilithic <strong>diatoms</strong> in <strong>acid</strong> water streams flowing into the resevoirLlyn Bri<strong>an</strong>ne. - Diatom Res. 6: 137-145.416417418419SAUNDERS, J.G. & G.F. RIEDEL (1998): Metal accumulation <strong>an</strong>d impacts inphytopl<strong>an</strong>kton. – In: W.J. LANGSTON & M.J. BEBIANNO (eds). Metal Metabolism inAquatic Environments: 59-76. Chapm<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d Hall, London.420421422SAKS, N.M. (1982): Temperature, salinty <strong>an</strong>d ultraviolet irradiation effects on thegrowth of strains of Nitzschia ovalis. – Mar. Biol. 68: 175-179.20

423424425426SCHOEMAN, F.R. & R.E.M. ARCHIBALD (1988): Taxonomic notes n the <strong>diatoms</strong>(Bacillariophyceae) of the Gross Barmen thermal springs in South West Africs/Namibia.– S. Afr. J. Bot. 54: 221-256.427428429SHERER, R.P. (1981): Freshwater diatom assemblages <strong>an</strong>d ecology/palaeoecology of theOkefenokee swamp/marsh complex, Southern Georgia, USA. - Diatom Res. 3: 129-157.430431432SIMONSEN, R. (1987): Atlas <strong>an</strong>d catalogue of the diatom types of Friedrich Hustedt,Vol: 2. - J. Cramer, Stuttgart.433434435STOCKNER, J.G. (1967): Observations of thermophilic algal communities in MountRainier <strong>an</strong>d Yellowstone National Parks. – Limnol. Oce<strong>an</strong>. 12: 13-17436437438SUZUKI, Y. & M. TAKAHASHI (1995): Growth responses of several diatom speciesisolated <strong>from</strong> various <strong>environment</strong>s to temperature. - J. Phycol. 31: 880-888.439440441VAN HEURCK, H. (1880-1885): Synopsis des diatomées de Belgique. – Ducaju & Cie.,Anvers.442443444445VERB, R.G. & M.L. VIS (2000): Comparison of benthic diatom assemblages <strong>from</strong>streams draining ab<strong>an</strong>doned <strong>an</strong>d reclaimed coal mines <strong>an</strong>d nonimpacted sites. - J. N. Am.Benth. Soc. 19: 274-28821

446447448VILLENEUVE, V. & R. PIENITZ (1998): Composition Diatomifère de quatre sourcesthermals au C<strong>an</strong>ada, en Isl<strong>an</strong>de et au Japon. - Diatom Res. 13: 149-175.449450451452WATANABE, T. & K. ASAI (1995): Pinnularia acoricola Hustedt var. acoricola as <strong>an</strong><strong>environment</strong>al frontier species occurred in inorg<strong>an</strong>ic <strong>acid</strong> waters with 1.1 – 2.0 in pHvalue. – Diatom 10: 9-11.453454455WEED, W.H. (1889): The diatom marshes <strong>an</strong>d diatom beds of the Yellowstone NationalPark. – Bot. Gaz. 14: 117-120.456457458459WHITTON, B.A. & B.M. DIAZ (1981): Influence of <strong>environment</strong>al factors onphotosynthetic species composition in highly <strong>acid</strong>ic waters. Verh. Internat. Verein.Limnol. 21: 1459-1465.460461462WOLFE, A.P. (2002): Climate modulates the <strong>acid</strong>ity of arctic lakes on millennialtimescales. Geology 30: 215-218.22

Table 1: Water chemistry of Beowulf Hot Spring, Yellowstone National Park. Allconcentrations are reported in µM, except where indicated.ParameterConcentrationNa 11136*Si 4690K 1225Ca 125Al 124As 19.6Mg 8.2Fe 6.2*P 4.5Zn 0.9Mn 0.6Cu 0.1<strong>an</strong>ions*Cl - 137702-*SO 4 1510*F - 147-*NO 3 20.0otherpH 2.26Temp ( o C) 67Ionic strength (M) 0.02* data <strong>from</strong> Inskeep et al. (2004)23

Table 2: A comparison of the morphology, ultrastructure <strong>an</strong>d ecology of Nitzschia cf.thermalis var. minor <strong>from</strong> Beowulf Spring, Yellowstone National Park, U.S.A. <strong>an</strong>dsimilar species.Nitzschia cf. N. hombergiensis b N. umbonata b N. steynii c N. rimosa dminor athermalis var.Length (µm) 15-28 32-52 22-125 27-54.5 60Width (µm) 2-4 5-6 6-9 4-5 7Striae / 10µm 23-27 34-40 24-30 24-26 25-28Fibulae / 10µm) 8-10 9-15 7-10 10-12 7-9Fibulae notesCentral areaconstricted0.5-1 µm thickon valve margin;irregularlyspacedIrregular & widelyspaced; c<strong>an</strong> extendto centre of valveShort, narrow,regularly spaced;convergence of 2-3straieProminent& evenlyspacedyes yes slight variable noHabitat Thermal springs Circumneutral;unpolluted watersThermal springs;eutrophic waters;<strong>acid</strong> mine drainagea. Description of specimens <strong>from</strong> Beowulf Spring, Yellowstone Nat. Park, U.S.A (this paper).b. L<strong>an</strong>ge-Bertalot (1978) <strong>an</strong>d Krammer & L<strong>an</strong>ge-Bertalot (1988)c. Schoem<strong>an</strong> & Archibald (1988)d. Bourelly & M<strong>an</strong>guin (1952)ThermalspringsRobustThermalsprings24

463464465466467468469470471472473474475476Figure captionsFig. 1. A: Beowulf Spring, Norris Geyser Basin. Brown areas are hydrous ferric oxides(HFO) <strong>an</strong>d green areas represent cover by rhodophytes including Cy<strong>an</strong>idium. B: Close-upof the tr<strong>an</strong>sition between the HFO mat <strong>an</strong>d Cy<strong>an</strong>idiaceae, with penny for scale. C: SEMphotograph of silica casts produced by coccoid Cy<strong>an</strong>idiaceae cells. D: Close-up of cellsin (C) showing remn<strong>an</strong>ts of soft-bodied cells within the silica cast (cc). E-H: SEMmicrographs of <strong>diatoms</strong> <strong>from</strong> the HFO mat. (E) Nitzschia cf. thermalis var. minor withcle<strong>an</strong> areolae devoid of precipitate. (F) Nitzschia ovalis (No) <strong>an</strong>d Pinnularia acoricola(Pa), also with cle<strong>an</strong> areolae; the cast of a Cy<strong>an</strong>idiaceae cell is also visible below N.ovalis. (G) A cell of N. ovalis encrusted in a diagenetic silica precipitate that completelysheathes the cell <strong>an</strong>d blocks areolae. (H) A Pinnularia acoricola cell with diageneticsilica papillae on the apical cell surface; areolae are visible beneath. Scale bars are 10µm, except (H) where it is 1 µm.477478479480481482483484Fig. 2. Light micrographs of Beowulf Spring <strong>diatoms</strong> <strong>from</strong> cle<strong>an</strong>ed samples (1000xmagnification). A-E: Eunotia exigua. (A-D) Valve views showing variable morphology.(E) Girdle view showing terminal raphe nodules at the apices (arrows). F-H: Nitzschia cf.thermalis var. minor. (F-G) Valve view; central constriction of valve margin <strong>an</strong>dinterruption of raphe <strong>an</strong>d fibulae; fine striae (H) girdle view. I-J: Nitzschia ovalis valveview; dense fibulae <strong>an</strong>d striae not resolvable under LM. K-M: Pinnularia acoricola (K-L) valve view. (M) girdle view. Scale bar is 10 µm.48525

486487488489490491492493494495496497Fig. 3. SEM photographs of <strong>diatoms</strong> <strong>from</strong> cle<strong>an</strong>ed samples of Beowulf Spring. A-E:Nitzschia cf. thermalis v. minor. (B) Shows the external view of the central nodule (cn)with the eccentric raphe. (C) An internal view showing the fibulae on the valve marginwith the interior of central nodule (cn) visible. (D) Apiculate distal end of the valveshowing fibulae <strong>an</strong>d distal raphe end terminating in a helictoglossa (h). (E) Apiculate endwith eccentric raphe F: Nitzschia ovalis cell. G-I: Pinnularia acoricola. (G) Hypovalveview showing the strongly convergent striae at the poles <strong>an</strong>d radial pattern in the centralarea. (H) Girdle view (I) distal raphe end deflected; striae appear as groups of individualpuncta in costa-like areas. J-L: Eunotia exigua. (J) Valve view with the curved rapheterminus on the valve face. (K) Raphe structure on the valve m<strong>an</strong>tle with helictoglossaevident. (L) Close-up of the internal raphe terminus showing the helictoglossa (h) <strong>an</strong>drimoportulae (r). White scale bars are 1 µm, except A, G, H, J, & K where it is 10 µm.26

ACDBccEF G HPaNoFigure 1

a b c d e f f’ g g’ h h’i i’ j j’ k k’ l l’ m m’Figure 2

cncnA B ChDEFG H IhrJKLFigure 3