Summer 2003 – Issue 66 - Stanford Lawyer - Stanford University

Summer 2003 – Issue 66 - Stanford Lawyer - Stanford University

Summer 2003 – Issue 66 - Stanford Lawyer - Stanford University

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The <strong>Stanford</strong> Law SchoolOffice of Career Services isn'tjust for students. It's for alumni whoare looking for new opportunities, and employerswho are looking for talented lawyers.The Office of CareerServices provides:• one-an-oneassistance to bothjob seekers andrecruiters• new online joblistings• a new onlineresume bank• personalized networkingcontactsAlumni seeking new opportunities:Visit http://www.law.stanford.eduladminlocs/alumni/ to learnabout online job listings, counseling on job search strategies,alumni networking, and other services.Employers:Visit http://www.law.stanford.eduladminlocs/employers/ to posta position online, review resumes of potential recruits, arrangeon-campus interviews, or schedule an on-campus reception.Call the <strong>Stanford</strong> Law School Office of Career Services at(650) 723-3924 for additional information.

FRO~I TIlE DE \~ ;- 1STANFOROLAWYERAffirmative Action: Looking ForwardBY KATHLEEN M. SULLIVANDean and Richard E. Lang Professor of Law and Stanley Morrison Professor of Lawhe end ofJune brings a peculiar frenzy to thosewho follow the Supreme Court. After the long,slow winter months of lmanimous rulings and technicalcases that only a lawyer could love, the Court,like Hollywood, saves the blockbusters for summer.This summer did not disappoint. On the finaldays of the Term, the Court issued two decisionsthat drew marquee attention. Both were written by<strong>Stanford</strong> graduates.In one, the Court, overturning a 17-year-oldprecedent, declared that the right to privacy bars the statefrom treating sexual intimacy between consenting adults as acrime, including for those in gay relationships. JusticeAnthony M. Kennedy CAB '58) who will be our featuredguest at Alumni Weekend <strong>2003</strong>, wrote the majority opinion.In the other, the Court reaffirmed a 25-year-old precedentthat had permitted the limited use of race preferencesin university admissions, upholding the <strong>University</strong> ofMichigan Law School's admissions policy against an equalprotection challenge by rejected white students. JusticeSandra Day O'Connor '52 CAB '50) cast the decisive voteand wrote the statesmanlike opinion of the Court.There have always been two very different defenses ofaffirmative action. One is bad.rward looking, and sees racepreferences as a remedy for past sins of discrimination.Thisrationale creates tension, however, if it appears that nonvictimsbenefit and nonsinners pay.The other sees racial diversity as vital to the effectivefUllctionjng of major institutions in society. This rationale,which is more forward looking and functional, was embracedby a host of amici curiae who filed briefs in support ofMichigan, from <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>University</strong> and the Association ofAmerican Law Schools, to FortLme 500 corporations andretired leaders of the U.S. military.Justice O'CO/mor's opinjon restated the diversity rationalebeyond the contours sketched in the 1978 Bakke opinion.She reiterated that "attaining a diverse student body is atthe heart of the Law School's proper institutional mission,"in part because "classroom discussion is livelier, more spirited,and simply more enlightening and interesting" whenstudents have "the greatest possible variety of backgrounds."Anyone who has taught at <strong>Stanford</strong> Law School can testifyto that. Minority stLldents comprise nearly one third ofour student body, and US News & U70dd Report ranks usamong the most diverse of any top law school in its "diversityindex." Our classrooms are greatly energized as a result.And our "alphabet organizations"-BLSA, SLLSA, ALSA,and APILSA-also produce some of the best and liveliestevents in our ongoing public intellectual life outside of class.But more important, as Justice O'Connor noted, raciallydiverse stLldents become racially diverse alumni. Diversity,she wrote, is important because universities, particularly lawschools, "represent the training ground for a large numberof our nation's leaders," and "in order to cultivate a set ofleaders with legitimacy in the eyes of the citizenry, it is necessarythat the patll to leadership be visibly open to talentedand qualified individuals of every race and ethnicity."As of course the path to leadership from <strong>Stanford</strong> LawSchool well attests. Countless law firms, companies, courts,and government offices have mjnority graduates of <strong>Stanford</strong>Law School in major leadership positions. We celebrate thisfact each year at our popular Alumni of Color event atAlumni Weekend. And our minority alumrli help recruiteach new class; we benefited especially this year from thework of devoted alumJlj who helped us to redress last year'sunusual shortfall in the number of African-American malefirst-year students.Of course we look inour admissions to diversityin its broadest sense-to allthe many ways, not limitedto race, in which a portfolioof different backgrounds,talents, and ambitions canproduce the best mix ofleaders and problem solversin generations to come.We could fill the classmany times over if we just looked to the very highest numbers.But as Justice O'Connor wrote approvingly of theMchigan Law School, we instead "engage in a highly inclividualized,holistic review of each applicant's file, givingserious consideration to all tlle ways an applicant mightcontribute to a diverse educational environment." Thismeans that our graduates include Navy SEALS, jazz musicians,teachers, and start-up entrepreneurs, as well as themost accomplished students just graduating from college.We're very proud of how we do all this. And we're verypleased to have tile blessing of tlle Unjted States SupremeCourt in paying attention to diversity while we do it.

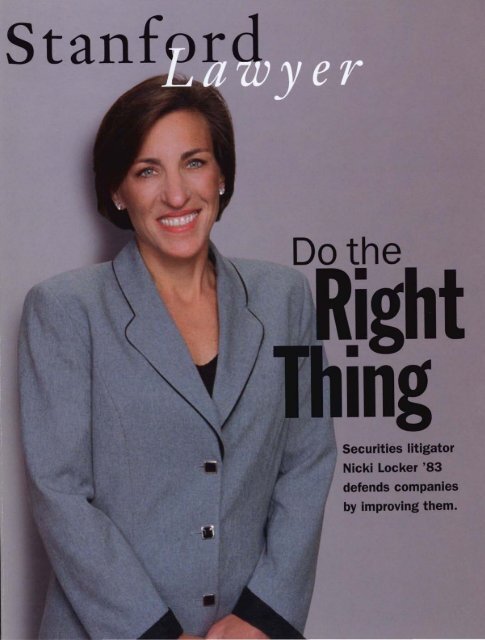

FEATURES12 A LITIGATOR FORTROUBLED TIMES17The rise of Nicki Locker '83heralds a new era in defendingcompanies against securities fraudcharges. Credibility is the nameof the game.SOME RIGHTSRESERVEDTo many, © means "Do not copyor share!" Is there an alternativefor artists who don't want torestrict such free distribution?A new nonprofit, CreativeCommons, has an answer.22 A TORT STORYLandmark laws come from thestrangest places. In an excerptfrom Robert L. Rabin's newbook, Ti!71S St01··ies, he descri beshow two uninspired lawyers,some far-reaching justices, anda treacherous bathroom sinkmade unlikely legal history.

28 GRADUATION <strong>2003</strong>Commencement was cause forcelebration but also intensereflection: graduates will beentering the profession at a timewhen many see the rule of law asa luxury.BRIEFS7 WHAT A DOLL! The ChiefJusticeas a bobblehead9 CITES Quotes from <strong>Stanford</strong>lawyers and friends10 BUILDING BRIDGES A promisingpartnership between East PaloAlto and the Law School11 GOLDILOCKS WALKS No jail timefor eating porridgeDEPARTMENTS1 FROM THE DEAN4 LEITERS6 DISCOVERY Do students viewthe Law School as paradise?32 AFFIDAVIT Crothers Hall, thedorm of champions33 CLASSMATES87 IN MEMORIAM89 GATHERINGS

Stal <strong>Lawyer</strong><strong>Issue</strong> <strong>66</strong>/ Vol.37/ NO.3EditorJONATHAN RABINOVITZj rab i n@stanford.eduCommunications DirectorANN DETHLEFSEN(AB '81, AM '83)an nd@stanford.eduArt DirectorROBIN WEISSrob i n wd esign@attbi.comProduction CoordinatorLINDA WILSONlinda. wilson@stanford.eduCopy EditorDEBORAH FIFEContributing WriterLINLY HARRISIaha rri s@stanford.eduClass Correspondents61 FELICITOUS ALUMNIEditorial InternsADAM BANKS (AB '03)LIEF N. HANIFORD(AB '03, AM '04)JOSEPHINE LAU(AB '03, AM '04)Production AssociateJOANNA MCCLEAN<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong>(ISSN 0585·0576)is published for alumni and friendsof <strong>Stanford</strong> Law School.Correspondence andinformation should be sent toEditor, <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong><strong>Stanford</strong> law SchoolCrown Quadrangle559 Nathan Abbott Way<strong>Stanford</strong>, CA 94305·8610or to:alumni.publications@law.stanford.eduChanges of address should be sent to:alumni.relations@law.stanford.eduCopyright <strong>2003</strong> by the Board of Trusteesof Leland <strong>Stanford</strong> Junior <strong>University</strong>.Reproduction in whole or in part. withoutpermission of the publisher. is prohibited.<strong>Issue</strong>s of the magazine sincefall 1999 are available online atwww.law.stanford.edu/alumnijlawyer.<strong>Issue</strong>s from 19<strong>66</strong> to the presentare available on microfiche throughWilliam S. Hein & Co., Inc., 1285Main Street. Buffalo. NY 14209·1987. ororder online at www.wshein.com/CatalogfGut.asp?TitleNo=400830<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> is listed in: Dialog'sLegal Resource Index and Current LawIndex and LegalTrac (1980-94).Printed on recycled paperLettersEvidence Class instead of Bike Ridesuring the 1998-99 academic year, Iwas a visiting third-year at <strong>Stanford</strong>Law School. I heralded from a law schoollocated in the gray climes of New Haven.That said, I have a rather shocking confessionto make: after orchestrating a wilyescape from the endless Northeasternwinter, I actuaJly rebuffed the perpetualCalifornia sunshine to attend all (well,nearly all) of my third-year courses.Why did I forgo scenic bike rides andpickup soccer games when I had a joblined up and my grades didn't matter?Because the teaching at <strong>Stanford</strong> wasfirst-rate. And right there at the apex wasProfessor George Fisher's evidencecourse. [See "Compelling Evidence,"Spring <strong>2003</strong>, pp. 8-12.]I truly appreciated the passion thatFisher brought to the subject, the claritywith which he presented the materialyes,even Rule 404(b)-the extensivepreparation he devoted to each class, andthe fairness and openness that he extendedto his students. I was happy to seethat he won theJohn Bingham HurlbutAward for Excellence in Teaching forthe second time in his career. Given theamount of time and energy he devoted tohis class, it is a wonder that he was ableto write a book and run a clinic "on theside."Samantha Gmf!Seizing Power: 1952 or 20001hen I saw the "Seizing Power"headline in the Spring <strong>2003</strong> issue,accompanied by the smiling faces ofChiefJustice William Rehnquist '52 (AB'48, AM '48) and Associate Justice SandraDay O'Connor '52 (AB '50), my firstthought was, Aha! <strong>Stanford</strong> Law Schoolis finally confronting the harsh realitythat these two "honored" graduatesstaged a judicial coup d'etat when theyand three colleagues stopped the 2000election and put George IV. Bush intothe White House.As I write, in April <strong>2003</strong>, the effects oftheir act of usurpation are emerging withhorritlc, literally murderous force. Thepresident, who was rejected in 2000 bymost voters but preferred by tlve judges,now makes war on American constitutionalvalues as well as on the internationalrule of law, raining death onanother people and glotying in America'ssupposed right to do so.This, I thought, was a fitting momentfor Stmifol'd Lmvyer and the Law School-------.....1lIIIi2_.._-~- ----~----_tllit_.-.I ,.-.--..._..._ot_---to begin a debate on whether we oughtso regularly to honor these two judges,these putschists. But alas, no. The seizureof power that was being debated at theLaw School and in your pages was theSteel Seizure case of 51 years ago, notthe blow to American democracy deliveredby our illustrious alumni t\vo yearsearlier.Mitchell Zi71t17le1'711tl71 '79The autbol' is one ofthe coordinatm1' ofLawProfessor'S f01' tbe Rule ofLaw, a gTOUp of673 US. law scbool teacben who condemnedthe five justices compl"ising the majority inBush v. Gore for "acting as political pl'OpOneJ1tsfOt· candidate Busb, not flsjudges. "No Longer "More England than England"he cover story about New ZealandChief]ustice Sian Elias, JSM '72["Hail to the Chief," Spring <strong>2003</strong>, pp.20-27], conveys both the deep changes inNew Zealand law since the 1970s and thepersonality and skill of the woman whohas played center stage.As an expatriate New Zealander livingin Canada, I have mostly seen these

LETTERS5STANFORDLAWY ERevents from aremove, but occasionalreUlrn visits(often highlightedby relaxing stayswith Sian and herhusband, Hugh Fletcher) have revealedtheir significance. As New Zealand losesits "More England than England" ch'lracter,it seems more self-confident,though perhaps less of a curiosity to outsiders.\Vhat appears retained, however,is a sense of fairness and a willingness toexperiment with bold new ideas, such asradical tort law reform and proportionalrepresentation.Both as an advocate and a judge, theChiefJustice has helped build the frameworkaround which many changes-especiallythose affecting Maori-have developedin ew Zealand law. Like Canada,New Zealand has started to recognize thecustoms of its indigenous populationswithin its legal system. This will be along and complex process, but not animpossible one if both sides realize theoverall g'ains to be achieved in so doin o'".The article's author, Todd \iVoody,who interviewed me last year for thepiece, may overstate my activist credentials,but he does a superb job of capUlringthe spirit of Sian Elias, a womanwhose intellect is matched only by hersense of humor and style.Bob Pateno71, .JSM '72A Word to the Younghere is the old tune that goes:"California here I come, right backwhere I started from; California I've beenblue, since I've been away from you."SubstiUlte the word "<strong>Stanford</strong>" for"California," and well, you all will get thepoint.It is the end of April, and tomorrowI am headed south from my home onWhidbey Island in 'Washington, viaMesquite, Nevada, to <strong>Stanford</strong>. Oncethere, I will look up Linda Wilson, thecoordinator for class notes, who is theonly person I still know on campus 62years after my graduating. I look forwardto the visit, as it will stir many memories.As my father used to say, "\Vhen youare young, you think you have all thetime in the world to accomplish life'smiracles, but you don't." As I walk thecampus, I will think about one classmatewho was terminally ill but insisted oncontinuing with his law sUldies only topass on during his second year. I also willremember John Haffner, who finishedlaw school with honors, but lost his lifeduring \iVorid War II while operating atank.May I pass on to the current fUUlrelawyers, now studying at <strong>Stanford</strong> LawSchool, the above advice of my father, inparaphrased form: Make good use of allyour time.Elster Haile '41EDITOR'S NOTESChris Wright '80, a partner at Harris,Wiltshire & Grannis in Washington,D.C., should be added to the list of<strong>Stanford</strong> lawyers involved in theSupreme Court case on the constitutionalityof the <strong>University</strong> of Michigan'sadmissions policies ("Cardinal Argumentson <strong>University</strong> of MichiganAdmissions Policy," Spring <strong>2003</strong>, p. 7).Wright was counsel of record for theMichigan Black Law Alumni Societyand filed an amicus curiae brief onthe group's behalf supporting theuniversity in Grutter v. Bollinger.A brief about <strong>Stanford</strong> Law ProfessorJohn Donohue's and Yale Law ProfessorIan Ayres's new findings that lawspermitting people to carry concealedweapons are not likely to cause adecrease in crime ("Ready, Aim,Calculate," Spring <strong>2003</strong>, p. 5) inaccuratelyattributed the source of a quotefrom John Lott, Jr., the scholar whoseconclusions Donohue and Ayres dispute.LoU's remark dismissing theDonohue-Ayres critique appears in apaper that he coauthored with FlorenzPlassman and John Whitley that wasposted in January <strong>2003</strong> on the SocialScience Research Network website.The quote is not from the April issue of<strong>Stanford</strong> Law Review, which includes asimilar comment in an article creditedto Plassman and Whitley but not Lott.<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> welcomes letters from readers. Letters may be editedfor length and clarity. Send submissions to Editor, <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong>,<strong>Stanford</strong> Law School, Crown Quadrangle, 559 Nathan Abbott Way,<strong>Stanford</strong>, CA 94305·8610, or bye-mail to jrabin@stanford.edu.The Law School rolled out a newlydesigned website in April. If you havenot already visited, please check outwww.law.stanford.edu for the latestnews about faculty, students, alumni,and events. Along with streamingvideo of recent conferences, listingsof new jobs, and links to Law Schoolpublications, it also offers the exacttemperature on campus!

6 DISCOVERYSUMMER<strong>2003</strong>"Who Could Resist a World-Class Law Schoolin Paradise?" -DEAN KATHLEEN M. SULLIVAN'I'TilE GRADUATIONceremony in May,we at Strl71frml<strong>Lawyer</strong> counted atleast a half dozenreferences linking theLaw School to paradise,including Dean Sullivan'soft-repeated remark (above),which she first made nearlya decade ago. But do theLaw School's students sharethe same feeling? And cana passion for the Farm coincidewith a career outsideCalifornia' In April andMay, the magazine surveyedJD candidates to gauge theirsentiments, eliciting the followingresponses.<strong>Stanford</strong> has the best weather I have ever lived in.TrueFalseCalifornia is the most beautiful state in the nation.YesNoBefore applying to <strong>Stanford</strong> Law School I had been to California:NeverOne to three timesFour or more timesI had lived in Californiafor an extended periodThe NortheastThe MidwestCaliforniaNo answerOther_•-iillIIIII••Being in California was an important reason I chose tocome to <strong>Stanford</strong> Law School.I plan to spend my life in:False---T~r~e:l~~~~~~~~~~~~===]NUMBER OFRESPONSESRESPONSEPERCENTAGE212 74%74 26%NUMBER OFRESPONSESRESPONSEPERCENTAGE156 55%128 45%NUMBER OFRESPONSESRESPONSEPERCENTAGE34 12%87 30%53 18%115 40%NUMBER OFRESPONSESNUMBER OFRESPONSESRESPONSEPERCENTAGE74%26%RESPONSEPERCENTAGE56 19%17 6%100 35%46 16%70 24%Since September 1, I have flown to the East:Once or twiceThree or more times1...- _Zero times~J;;;;;r~~~~~~~~~~JNUMBER OFRESPONSESRESPONSEPERCENTAGE76 27%107 37%103 36%Since enrolling at law school, I have interviewed for jobs in Boston,New York City, Philadelphia, or Washington, D.C.TrueFalseNUMBER OFRESPONSESRESPONSEPERCENTAGE149 52%139 48%If you answered "True" to the previous question, how do you think thatbeing at <strong>Stanford</strong> instead of a law school in the Northeast affectedyour prospects for the position for which you were interviewing?An advantageA disadvantageNo differenceNo answer_~I=~•NUMBER OFRESPONSESRESPONSEPERCENTAGE78 41%22 11%45 23%47 24%

BRHJ'~ 7STANFORDLAWYERBriefsWHAT A DOLL!HI EF JUSTICE WI LLIAJII H. R EIINQUIST '52 (AB '48, AM '48) hasreceived many honors, but none perhaps as curious as the bobbleheadthat mysteriously appeared in his chambers in May. Although only eightinches tall, the ceramic figurine captures his likeness, right dOl-vn to thefour gold stripes on his judicial robes and the solemn expression on hisface. One of the doll's creators, Ross Davies, describes it as being kindof "cute," while still projecting a stately presence.Davies, an assistant professor at George Mason <strong>University</strong> School of Law, isthe editor-in-chief of The Green Bag, a nonprofit humor journal about the law andthe legal profession, to which a number of <strong>Stanford</strong>Law School faculty have contributed. As ofJune,only two prototypes of the doll existed, butDavies plans to produce about 1,000, and sendcomplimentary copies to those readers whoalready subscribe.Rehnquist can be added to the list of dignitariesand celebrities-including PresidentGeorge W Bush, Sammy Sosa, and OzzyOsbourne-who have been immortalized as bobbleheads.But the Rehnquist doll is unusual for itsscholarly attention to detail: its base has a mapfrom Rehnquist's eloquent 1979 opinion in Leo Sheepv. U.S. regarding 19th-century railroad easements inWyoming; its hands hold a book markedVolume 529 of the Court's reports, whichincludes a notable Rehnquist ruling on acriminal procedure matter that involved agreen bag (it held a brick of methamphetamine);and the ChiefJustice isportrayed wearing the tie that hedonned to preside over President BillClinton's impeachment proceedings.Davies declines to reveal how thebobblehead suddenly appeared inRehnquist's chamber, other than admittingthat he felt it would be disrespectful tocirculate the doll wltil Rehnquist had receivedone. Davies was confident that Rehnquist, whoby reputation has a good sense of humor,would appreciate it, and indeed, the ChiefJustice sent Davies a note of thanks.So is Davies now finished with the dollbusiness? "Stay tuned" was all hewould say. After all, there's another<strong>Stanford</strong> Law School graduate on theCourt who might look quite fetchingas a bobblehead.ALUMNI SPOTLIGHTS36 Sandra Day O'Connor '52Remembering Thurgood Marshall40 Karl ZoBell '58Defending Dr. Seuss53 Fred Phillips '71A Breath of Life57 Jacqueline Stewart '76Exploring Lake Michigan's Riviera60 Christina Fernandez '78Working for the Ultimate JudgeCOLE EARNS TENUREMarcus Cole,a bankruptcy andcorporate reorganizationlawexpert, wasawarded tenurein March. ANational Fellowat the Hoover Institution, he joined theLaw School faculty in 1997 after practicingat the Chicago law firm of MayerBrown. He teaches contracts amongother subjects.JUDGES CONFERENCEMore than 30 federal trial judgesattended lectures by <strong>Stanford</strong> Law professorsat the Law School in May, hearingabout an array of SUbjects, fromcloning to securities fraud. One judgeremarked that it was the best seminarhe'd attended in 16 years on thebench. The Hon. Fern Smith '75, directorof the Federal Judicial Center, theevent's sponsor, credited the strongprogram to Dean Kathleen M. Sullivan,who said, "It's very easy to produce awonderful program when you have awonderful faculty."

8 BRIEFSSUMMER<strong>2003</strong>SEND IN THE CLONESEFORE PROFESSOR HANK GREELY adjourned theFaculty Senate's last session of the academic year inJune, six self-proclaimed Greely clones-with whitewigs, bushy stick-on mustaches, and the stripedsweaters that are a Greely trademark-interruptedthe meeting. It was a tribute to Greely, the Senate's chair,who is also an expert in the legal and ethical issues ofcloning. The disguised professors, all members of the Senatesteering commitee, had adapted Samuellaylor Coleridge'sKubla Khan. In wlison they began:171 Senate would the Greely clonesA stately ne7V l'egime decreeWhere 1"C.wlutions and rep011.\·On budgets, 11/ajors, 17tles, and 5p011SVVould pl'OCeed iu 111/.11zbers infinite.After several more stanzas, Greely declared, "I'm speechless-andyou know how rare that is."Earlier in the meeting, Greely described the pros andcons of his one-year gig in charge of the Senate, a body thatHank Greely [Ieftl. C. Wendell and Edith M.Carlsmith Professor of Law. served as chair ofthe Faculty Senate. His leadership inspired atribute [above] from colleagues.wields an important influence on academic policy, though ithas a limited role in direct <strong>University</strong> decision making. Heobserved that the Senate successfully highlighted its concernson a host of subjects, including tile U.S.A. Patriot Act,administrative computing, grading policy, and the system bywhich faculty salaries are set.But Greely also noted that attendance "stunk," leadinghim to worry abom the Senate's future. "This publicforum-where any question can be put to the president, tothe provost, to the administration-is a very valuable thing,"he said. "I would hate to see us lose that."Based on a June 18, <strong>2003</strong>, <strong>Stanford</strong> Report stOT),MAKING THE GRADE<strong>Stanford</strong> Law School was o. 2 for the fourthconsecutive year in US News & World Report's annualranking of the nation's law schools.The Burton Awards for Legal Achievement honoredSLS in June as the only law school with a studentwinner for four consecutive years. For <strong>2003</strong>, thejudges, who select the best works of legal writing,chose an article by Marcy Karin '03 in the lawschool category. III the law firm category, theyselected a piece by Cornelius Golden, Jr., '73 (AB'70), a partner at Chadbourne & Parke.Eugene Mazo '04, Anna Makanju '04, and CynthiaInda '05 were awarded Paul and Daisy SorosFellowships for Jew Americans in March.In June, the Legal Aid Society-Employment LawCenter gave Miguel Mendez, Adelbert H. SweetProfessor ofLaw, its Tobriner Public ServiceAward for his commitment to diversity and mentoringnew lawyers. .In April, State Controller Steve Westly namedPamela Karlan, Kenneth and Harle MontgomeryProfessor of Public Interest Law, to California'sFair Political Practices Commission.Dean Emeritus Paul Brest, president of theWilliam and Flora Hewlett Foundation, wasappointed to Caltech's board of trustees in May.THREE NEW PROFESSORSThe Law School is bringing new expertise to the study of comparativeand international law with three new faculty members, all to beginteaching in the fall semester.Amalia Kessler, a legal historian who studies civil law systems andEuropean legal history, and Jennifer S. Martinez, an international lawspecialist, were appointed assistant professors. Allen S. Weiner '89was named to the newly established Warren Christopher Professorshipin the Practice of International Law and Diplomacy, a joint professorshipbetween the Law School and the Institute for International Studies.Kessler, with a JD from Yale and a PhD from <strong>Stanford</strong>, was recentlya trial attorney in the Justice Department's honors program. She hadbeen a clerk to Judge Pierre Leval on the U.S. Court of Appeals for theSecond Circuit. Martinez, a Harvard Law School graduate, was aresearch fellow at Yale after working as a clerk to Judge GuidoCalabresi on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, JusticeStephen Breyer on the U.S. Supreme Court, and Judge Patricia Wald atthe U.N. International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.Weiner was formerly the legal counselor at the American Embassyin The Hague and Attache in the Office of the Legal Counselor. He isthe first to fill the professorship that honors former Secretary of StateChristopher '49. It is a rotating three-year position for lawyers whohave extensive experience in international law and diplomacy.FAREWELL TO SIMONWilliam H. Simon resigned as William W. and Gertrude H. SaundersProfessor of Law, as of June 30, to join the faculty at Columbia LawSchool. Simon taught at SLS since 1981 and was awarded emeritusstatus.

"Recoveries do not happen withoutrisk taking. "JOHN CHAMBERS, president and CEO of Cisco Systems,explaining that legislators and regUlators have beenvery constructive in addressing many areas of corporategovernance, but that they should be careful not toovercorrect when considering new rules for expensingstock options, because it will impact risk taking.Chambers's off-the-record talk [he graciously agreedto let us print the above remark) was made at the LawSchool on June 3 as the final keynote address ofDirectors' College. Other participants in the star-studded event were SECChairman William Donaldson, former SEC Chairman Harvey Pitt, DelawareChief Justice E. Norman Veasey, and California Treasurer Phil Angelides."Ifoffering to resign the bestjob in theworld at the greatest law school in the nationhelps build the alliance necessary to get itpassed, then I am happy to make that offer. "LAWRENCE LESSIG, Professor of Law, at an April 28 news conferencewith U.S. Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D.-San Jose) to announce her introductionof legislation, which Lessig had helped develop, aiming toreduce e-mail spam. Lessig promised that if the bill was enactedand did not work, he would resign his <strong>Stanford</strong> professorship. TheLessig-Lofgren proposal was one of a number of bills over the lastfew months that gave Congress impetus to stem the proliferationof spam."So by taking these laws offthebooks, the Supreme Court is makingclear that being gay is not being acriminal. "PAMELA KARLAN, Kenneth and Harle MontgomeryProfessor of Public Interest Law, discussing theSupreme Court's decision in Lawrence v. Texas on the NewsHourwith Jim Lehrer on June 26. Earlier in the year Karlan had filed afriend of the court brief on behalf of 18 constitutional law professors,urging the Court to strike down the Texas sodomy law at theheart of the case."In short, the pipeline leaks, and ifwe waitfor time to correct the problem, we will bewaiting a very long time. At current rates ofchange, it will be almost three centuries beforewomen are as likely as men to become top managers in major corporationsor to achieve equal representation in Congress."DEBORAH L. RHODE, Ernest W. McFarland Professor of Law, in the introductory essay to The Difference"Difference" Makes: Women and Leadership (<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>University</strong> Press, <strong>2003</strong>), a collection of papersedited by Rhode. On April 21, along with Dean Kathleen M. Sullivan, Rhode spoke at the Law Schoolabout the book, explaining that women are now well represented in the middle ranks of law firms andcorporations, but that more work is needed to bring them into leadership positions."It's a centrist, moderate court thatexpresses the values ofmost Americans. "DEAN KATHLEEN M. SULLIVAN, Richard E. Lang Professor of Law andStanley Morrison Professor of Law, describing the general philosophyof the current Supreme Court on the NewsHour with JimLehrer on June 27. In a discussion of the decisions the Courtissued in its latest term, Sullivan argued that the two mostprominent rulings-its upholding of the use of race in universityadmissions and its strikingdown of an antisodomy lawreflectviews about racialdiversity and privacy that havebecome widely accepted inthe last generation."It's hard to say justice hasbeen done. What happened toLisa Hopewell was very, verysad, but it's a separatetragedy. Rick spent the past12 years in prison for acrime he didn't commit. "1,1II~ir1!-':··~"A!J. '",'111 r,-;;, ~.~"~'• - !.• .:!"ALISON TUCHER '92, as quoted in the San Jose Mercury News onJune 18, shortly after proving that her pro bono client, QuedillisRicardo "Rick" Walker, had been wrongly convicted of the murderof Lisa Hopewell in 1991, for which he had served 12 yearsin prison on a sentence of 26 years to life. Tucher, an associateat Morrison & Foerster who first learned of the case in her lastyear of law school, established Walker's factual innocence byfinding witnesses who said that Walker was not present at thecrime, by discovering DNA evidence that placed another suspectat the murder scene, and by uncovering deals that the prosecutionmade with one witness that tainted the testimony.

10 BRIEFSSUMMER<strong>2003</strong>CELEBRATING A CLINIC AND A PARTNERSHIPA new Law School venture providing live client services takes root in East Palo Alto.At the April 2 opening celebration ofthe <strong>Stanford</strong> Community Law Clinic, apurple ribbon, the color of <strong>Stanford</strong> LawSchool, was wrapped with blue andwhite ribbons, the colors of East PaloAlto, to signify the intertwining fortunesof the school and the city.East Palo Alto Mayor Patricia Fosterremarked to the crowd of more than100 students, alumni, local elected officials,and citizens: "If you are comingover here just to help us, don't bother.But if you are coming over because youbelieve your liberation is tied to ours,welcome!" That thought was secondedby Dean Kathleen M. Sullivan, whoobserved that if the clinic is to succeed,it must "offer lessons of law thatstudents can't learn in a classroom."A dozen students began working inthe clinic in January, and in its firstsemester, they handled more than 50cases involving workers' rights, benefits,and housing issues. Under thedirection of the clinic's supervisingattorneys, they conducted administrativehearings, drafted pleadings, prepareddiscovery, and interviewed witnesses.In one case, students persuaded aSan Mateo County appeals officer toauthorize Medi-Cal benefits for a 65year-old diabetic woman who had beendenied such services because her familyhad bought a house in rural Mexicoin 1961 for $100. In another case,they stopped a car wash manager fromforcing his employees to tape theirpockets shut to prevent theft, whichdamaged many of the workers' pants.And the clinic is batting two-for-two inunemployment benefits hearings, twiceoverturning initial decisions thatclients were ineligible.Already 18 students have signed upto work at the clinic in the fall semesterand take the accompanying class.The excitement about the clinicwas evident at the open house celebration.Members of the Law School'sPLANTING FLOWERS, BUILDING BRIDGESliE CITY OF EAST PALO ALTO liesafewmileseast of the <strong>Stanford</strong> campus, but this comlllunity of29,000, on the other side of Highway 101, is aworld apart. Despite its palm trees and sunny skies,it is a 2.5-square-mile pocket of poverty amid theaffluence of Silicon Valley."What bothers me is how hidden it is from its neighbors,"remarks Jenna Klatell '04. "I find myself continuallypointing it out to people who don't even know it's there."To improve awareness of this neighboring city, <strong>Stanford</strong>law students on April 26held the School's annualBuilding COllllllunjty Day.On that Saturday morning,about 75 students Illade thetrek to East Palo AJto andjoined with residents to clearthe new site for a local nonprofit,the EcumenicalHunger Program; to buildMiddle school and law schoolstudents created a shrine for adeceased 13-year-old girl.flower boxes and paint hopscotchcourts at an elementary school; and tocreate a memorial to a 13-year-old girlwho died in a fire on Christmas Eve.Klatell helped organize the groupthat worked on the memorial gardenfor Lucy Sanft, an eighth grader at the4gers Academy, a middle school fortroubled youth. Sanft's classmates hadbeen grieving her death, says Klatell,<strong>University</strong> President John Hennessy, Menlo ParkMayor Nicholas Jellins, Dean Kathleen Sullivan,and East Palo Alto Mayor Patricia Foster celebratethe opening of the new law clinic.Board of Visitors, who were at theSchool for the board's annual meeting,were among those touring the clinic'snewly remodeled storefront office on<strong>University</strong> Avenue. <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>University</strong>President John Hennessy, who helpedto arrange the clinic's funding, joinedin the festivities, as did MayorNicholas Jellins of Menlo Park, whosecitizens are also served by the clinic."The services being offered are essential,"Jellins said.Shirin Slnnar '03 (left)brought friends withher to an East PaloAlto elementaryschool, where theyplanted flowers.who volunteers at the school, and they had decided on theirown to make a tribute to her memory.So many volunteers showed up at the school that daythere weren't enough shovels. Some of the middle schoolstudents began to dig with their hands. By mid-afternoon,the students' parents and other neighborhood adults wereadmiring the completed garden.The projects SLS students tackled in April had nothingto do with law school studies, admits David Kovick '04, anorganizer of the workday, but they were a reminder of theworld beyond <strong>Stanford</strong>. "Just because we're sUldying the law,we don't only and always have to be about the law," he says.

BRIEl- ~ 11STANFORDLAWYERGOLDILOCKS WALKSGirl freed despite eating porridge and using beds.The following article b), Kim Va appeared i17 the San Jose iVIercury ews 017 H'ida)', April 25, <strong>2003</strong>.OLD I L 0 C K S \I'AS F R E E to getlost in the woods again after ajury acquitted her of burglarycharges Thursday, apparentlybuying into the defense'sargument that no child wouldbreak into a house just to eat MamaBear's awful porridge.It was a bitter defeat for the government-<strong>Stanford</strong>Law School DeanKathleen M. Sullivan, who deliveredthe prosecution's closing argument,complained of "jury nullification."Nonetheless, it was also a good lessonfor the children participating in TakeYour Daughters and Sons to Work Day.Like many businesses, <strong>Stanford</strong>invited its employees to take theirchildren to work Thursday, trying toinspire the children to think aboutcareers. Instead of just having approximately300 kids tag along with theirparents, the <strong>University</strong> developedhands-on workshops on everythingfrom a Junior Iron Chef competitionto how to coach athletics.The law workshop offered aglimpse into the high-profile world ofcelebrity trials, complete with scandal,rumors of movie deals, and a glamoroussuspect. Reporters (cnildren shadowing<strong>Stanford</strong> News Service reporterBarbara Palmer) sat in the front row,scribbling in small notebooks.The case of Goldilocks and thethree bears has already spawned severalbooks. Goldilocks, a small girl withmany ringlets, was lost in the woodswhen she happened upon a house. Shewent inside and sampled the bowls ofporridge that were set out, sat in variouschairs, and tried out the bedsbefore falling asleep in the smallestone. It was there she was discovered bythe bears, who returned home after awalk in the woods.Annamaria Armijo-Hussein, a 12year-old member of the prosecutionteam whose mother teaches religionand rebellion at <strong>Stanford</strong>, said shethought the team had a strong burglarycase against Goldilocks. "They didn'tinvite her in," she reminded fellowprosecutors.But earlier in the day, Hussein worriedthat the jury would sympathizewith the suspect. "She's definitelyguilty," she said outside the courtroom."She looks innocent. The only reasonthey're so nice to her is because she'scute.... It's our only weakness."And things seemed to go badly forthe prosecution with the questioning ofMama Bear. Do you make excellentporridge? the prosecution asked."Objection!"V\That's the basis for the objection?the judge [Vice Provost LaDorisCordell '74] asked the defense."Who cares?"It was overruled.Apparently, the six-person jurythreeboys, three girls, all human-didcare.Law Professor Pamela Karlan, donningtiger ears in her role as a defenseattorney, argued persuasively thatGoldilocks did not come into thehouse with the intent to eat the porridge.In fact, the defense said thateven Baby Bear didn't like it, andMama Bear was keeping her child malnourishedby serving only porridge,instead of the recommended five dailyservings of fruits and vegetables.In a controversial move, Karlanplayed the species card, saying thatGoldilocks didn't flee the house out ofguilt, but fear of the animals and theirlarge snouts."In many countries of the world,the bears would eat Goldilocks,"Karlan said.Juror Martin Smith, 14, voted foracquittal, saying, "All the events turnedout good." Baby Bear didn't have to eatthe porridge, and will get a new chair.(It's likely the Bears will pay for thenew furniture. Goldilocks has refusedto pay any damages or apologize, sayingthe Bears owned shoddy furnitureand hadn't apologized for chasing her.)But, as with all fairy tales, theremay eventually be a happy ending.Is there a movie deal in the works?"This was more of a personal familything,'" said Mama Bear, played byZuri Ray-Alladice, 13. "But if Spielbergapproaches, we'll move forward."Copyright © <strong>2003</strong> Sa17 Jose Mercmy News. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission.

'"..~<strong>2003</strong>The board of directors has just learned that its company's numbers aren't adding up.Nicki Locker '83 is ready to defend them, but first they have to come clean.BY JONATHAN RABINOVITZ

NICKI LOCKER 13STANFORDLAWYERt looked like a routine insider trading case. A flurry of sales in thestock of a software company, Critical Path, had occurred in the hoursbefore the company released a disappointing quarterly statement.ON T ESDAY, JANUARY 30,2001, Wilson SonsiniGoodrich & Rosati dispatched Nicki Locker, a 43-year-oldpartner, to look into the matter for the company, one of thefirm's clients. Her first few conversations with employees inCritical Path's San Francisco offices turned up nothingunusual, but then Larry Reinhold, the newly recruited chieffinancial officer, pulled her aside. He was trembling and toldher that they needed to speak privately-on the telephoneassoon as she left."Are you sure you're not being hysterical?" askedLocker, a native New Yorker who is known for asking themost blunt questions in the most disarmingly friendly manner.He assured her he wasn't.A few hours later, Locker understood what Reinhold haddiscovered. Months later it would be determined that roughly20 percent of the previous two quarters' reported revenuesdid not exist. But on that day all Reinhold and Locker knewwas that several transactions appeared to be questionable.Critical Path, a four-year-old dot-com with a marketvalue of nearly $2 billion, was about to be one of the firstcompanies to enter a new era of securities litigation. And thechallenge the case would pose-winning mercy from governmentlawyers by documenting fraud and restoring goodcorporate practices-would soon be the priority assignmentfor Locker and other securities lawyers.As soon as Locker finished her telephone conversationwith Reinhold, she kicked into crisis mode. She is a lean,energetic woman who gets antsy if she hasn't done her morningrun of five miles, and over the next 72 hours she barelyslept as she prepared the company to take a series of emergencymeasures, from halting trading in its stock to suspendingthe executives who appeared to be responsible for a fraud.The pivotal moment came at the emergency meeting ofCritical Path's board of directors that she had organized atVVilson Sonsini's San Francisco office. It started at 3 p.m. onThursday and lasted past midnight. None of the directorswere prepared for Locker's and Reinhold's news: The company'snumbers appeared to be false, and immediate actionwas needed. There were people at the board meeting whoasked whether they could have more time to study the problemsbefore alerting the market and regulators, saysReinhold. Locker answered that it was essential to go publicwith the problem immediately, he adds.On Friday, February 2, at 9:09 a.m., the NASDAQannounced it had halted trading in all shares of Critical Path.The company had issued a news release declaring that itsprevious quarter's results may have been "materially misstated"and that two top executives had been placed on leave. Theboard had asked Locker to conduct an investigation. Thecompany's existence turned on whether Locker could quicklydetermine what had happened and correct the problems.Speaking of her response those first three days, Lockersays, "I did what any lawyer would do." But other lawyersdisagree. "She was doing post-Enron crisis control in a preEnron environment," says Joseph Grundfest '78, W A.Franke Professor of Law and Business and a former commissioneron the Securities and Exchange Commission. "Shewas ahead of the curve."A New EraSecurities litigators have a different job now than they did acouple of years ago.Before 2002, they were primarily dealing with shareholderlawsuits and plaintiffs' attorneys, battling to get theclaims dismissed and generally settling those that weren't.Today, lawyers like Locker are more concerned with cooperatingwith the SEC and the Justice Department, conductinginternal investigations of their clients, and pushing them toimprove governance practices. Enron, WorldCom, and otherfrauds led to this change in the securities law practice. Thebiggest cases in <strong>2003</strong> aren't about missed forecasts, but aboutbig financial restatements, accounting irregularities, the handlingof initial public offerings, and conflicts of interest.At a conference of financial managers in San Jose inMay, Locker was on the keynote panel with one otherspeaker, Harold Degenhardt, the district administrator ofthe SEC's office in Dallas. Degenhardt says that the SEChad 262 cases for financial fraud and disclosure in 2002,more than double the number it was investigating in 200l.Today's problems don't come from "the tension betweenaggressive and conservative accounting, but from legal versusillegal accounting," he says. And he advises the executivesin the room that when the SEC invites them in for achat, they should come in immediately. "We don't like peopleto miss our message," he says. "It hurts our feelings."Locker takes the microphone. She is one of the fewwomen in the room, before a Silicon Valley crowd of 150,standing out from the button-down shirts and khaki pants inPHOTO BY RUSS FISCHELLA

14 NICKI LOCKERSUMMER<strong>2003</strong>her elegant St. John suit, with Peter Pan lapels, that complementsher piercing green eyes. Her talk concentrates on thesubject that is on everyone's mind: "How to get off theSEC's radar screen." There's no easy answer, she warns,noting that even companies in compliance with GenerallyAccepted Accounting Principles have found themselvesbefore the SEC. She urges companies to implement systemsto detect fraud. That would include, for instance, a quarterlyreview of all deals in which the company is both buyingfrom and selling to the same partner. And she cautionsagainst Degenhardt's advice to drop by immediately afterreceiving his cal!. "You don't go by there until you've donesome type of investigation," she says. The company needs toknow beforehand how serious the problem is, as well as todemonstrate its intent to get to the bottom of it, she adds.The respect Locker shows to the SEC is typical of herstyle-and an important new trait for lawyers handlingtoday's securities cases. The relationship between plaintiffs'N"icki Locker was certainly bright. She graduated fromYale College summa cum laude in a special major shedesigned herself (law and ethics in medicine) and was electedto Phi Beta Kappa. In her senior year, it appeared that shewould fulfill her mother's dream. She was accepted into thejoint MDI]D program at Duke <strong>University</strong> and was ready togo until she had a sudden revelation. "I didn't like to look atblood," she says.Locker grew up in Queens, and she has the accent toprove it. Her mother was the general counsel at QueensCollege. Her father, a mechanical engineer, was a nationalhandball champion. Locker was an all-city field hockey playerand a member of the tennis team at Yale. She recently rana marathon and is now training to do a triathalon.For law school, Locker decided that she needed to getaway from the East and enrolled at <strong>Stanford</strong>. She was a clerkto Anthony Kennedy, at that time a Judge on the U.S. CourtofAppeals for the Ninth Circuit (now a Justice on the"I think this work is a blast," says Lockerand defense lawyers in securities litigation has traditionallybeen as contentious as any in a profession that has in recentyears lost much of its civility. "You see lawyers on both sidesmaking extreme arguments," notes Robert Gans, a plaintiffs'lawyer who has been litigating against Locker for three yearsin a case involving the company Network Associates. Manyplaintiffs' lawyers believe that corporate executives are out todefraud shareholders, and many corporate hlwyers see allshareholder lawsuits as frivolous, he says. "Nicki isn't one ofthose," he adds. "Aside from being an excellent lawyer, she'sa straight shooter-she doesn't hide the bal!."Such credibility is of particular importance now, becauseresolving cases involves a greater amount of collaborationbetween the two sides. It's no longer enough to simply getthe case dismissed or have the insurer payout a settlement.Increasingly, the company must work with the parties bringingthe action to show that it has adopted better practices.Grundfest highlights this change in a forthcoming article."Settling entities will have to agree to forms of behaviormodification that will promote 'good governance' agendasand provide for active monitoring designed to assure thatwrongful conduct does not recur," he says. "The simpleinjunction commanding 'go and sin no more' will becomescarcer in the evolving enforcement environment."An Unlikely Securities StarNicki Locker was not supposed to be a securities litigator."Every good Jewish mother wants a bright daughter to be adoctor," says Lola Locker, Nicki's mother.Supreme Coun), then joined 'Nilson Sonsini, where she hasstayed her entire career. She married Lionel Boissiere, MBA'85, in 1986, and they have a nine-year-old son, Jacob, and aseven-year-old daughter, Jaye CorioLocker's career is unusual in that she started in intellectualproperty, migrated to commercial litigation, then, as apartner, decided to make her specialty securities litigation, afield in which the finn is renowned. "In lieu of a midlife crisis,she decided to change directions in her career," remarksBoris Feldman, a Wilson Sonsini partner and one of thenation's most highly regarded securities litigators. Few otherlawyers, he says, could have done it: She would put her childrento bed, then read decisions, briefs, and the statutes intothe early morning hours. "In very short order she knew asmuch as any of us," he says.Locker insists that she's not entirely sure why she madethe switch. She says she was drawn to securities litigationpartly because that's where the big cases are, and partlybecause it seemed like a challenge. "I want to be where theaction is," she says. "I like pressure, I like high profile, I likevery intense.\tVhat can I say? I think this work is a blast."And she makes an admission that would raise the eyebrowsof some corporate defense lawyers: "If I weren't at WilsonSonsini, I'd love to work at the SEC."The switch only added to her stature within WilsonSonsini. She has served on the executive and compensationcommittees and was the co-chair of the member nominatingcommittee, which selects new partners. Larry Sonsini, thefirm's chairman, calls her a leader who has a "future in high

NICKI LOCKER 15STANFORDLAWYERlevel management" at Wilson Sonsini.What makes Locker's success all the more remarkable isthat securities litigation remains one of the last male bastionsin the legal profession. For better or worse, there's a machismoto the field, and a widespread perception remains thatwomen face a tougher time being rainmakers in such highstakecases, says Feldman. Locker, however, has managedto build a strong client list, including Agilent Technologies,Guidant, 12 Technologies, Juniper Networks, NetworksAssociates, and Veritas Software, among others.Settling with ReformsNo case has done more for Locker's reputation for being onthe leading edge of securities litigation than a giant shareholderlawsuit charging that the stock prices of several hundredinitial public offerings were fraudulently inflated. Itinvolves 309 companies that went public and the 55 brokeragefirms that underwrote the offerings. There are dozensof defense lawyers on the case, but Locker represents moreissuers than anyone else-50 high-tech companies-and shewas one of the two defense lawyers for the issuers who presentedoral arguments in the case.After U.S. District CourtJudge Shira A. Scheindlindeclined to dismiss the claims, Locker and the other lawyersrepresenting the issuers worked with the insurance companiesto hammer out a proposal for an unprecedented settlement,guaranteeing to pay investors $1 billion if the plaintiffsAssuming the settlement goes through, it will be a coupfor the issuers. The guarantee would average out to roughly$3.3 million per issuer, to be paid-if at all-by the insurers."The issuing companies probably view Nicki as a hero," saysGrundfest. "It may get them out of this complex litigationwithout having to dig into corporate pockets."The deal, however, is also significant for what it showsabout corporate defense lawyers being willing to step up andreform corporate practice. Whether the issuers publiclyaccept the plaintiffs' argument that they should have beenaware of the alleged stock manipulations by the underwriters,the settlement places the issuers in the position ofadding pressure to the underwriters to improve their practices.Ne71' York Times reporter Gretchen Morgenson writesthat the proposed settlement creates an incentive for thecompanies to assist the plaintiffs' lawyers in their actionagainst the Wall Street firms. Locker says it's too soon to saywhether that incentive will lead to any action. But MelvinWeiss, the lead lawyer on the other side, told Morgensonthat the agreement would require issuers to provide documentsand other support to the shareholder lawyers.The IPO case is unique among securities cases in itsscale and its focus on public offerings. But even in more typicalcases, Locker has demonstrated an ability to win for herclients, while also improving corporate practices. Take herrepresentation of Network Associates, a company that hadacknowledged problems in its accounting and had restated"The issuing companies probably view Nicki as a hero,"says Law Professor Joseph Grundfestdo not win at lcast that much from the underwriters. "This isthe mother of all securities settlements," remarks JeffRudman, a partner at Hale and Dorr who serves with Lockeron the steering committee of lawyers representing the issuers.The settlement proposal, which has yet to be approved,is not the work of one lawyer, but Rudman describes Lockeras invaluable in working through the "endless negotiations"with insurance lawyers and plaintiffs' lawyers. "If there's asemicolon missing on page 42, she'll find it," he says. Andshe made sure that the very complicated formulas in the dealwere not obfuscated in jargon, but spelled out clearly. SaysRudman: "Other folks in the room might be abashed at saying,'I don't know what this means,' but Nicki would interrupt,'Look fellows, I know you're all geniuses, but whydon't you explain it to me, because I know I'm not stupid.'"(One colleague refers to Locker as Columbo with a St.John's wardrobe.) The problem often wasn't with Locker,but with a clause that didn't make sensc.its earnings and revenues.Locker and other lawyers at Wilson Sonsini aggressivelyfought a class action lawsuit against their client, and in Marchthey succeeded in having a large portion of the fraud claimsdismissed. The briefs highlighted her encyclopedic grasp ofthe facts. They persuaded the judge, for instance, that theplaintiffs' confidential witnesses didn't have the basis toknow the information that they had provided the plaintiffs.And the judge was also convinced that the complaint's allegationsweren't "sufficiently particularized" to state a claimfor revenue recognition fraud.In the past, such a court outcome would have been sufficientrepresentation for a corporate attorney, but Locker didmore. She scrutinized the company's operations, and, in theareas where it did not meet best practices, she worked withthe new management to make improvements. Kent Roberts,general counsel at Network Associates, says that the first fewtimes he met her, it didn't feel like she was working for him,

16 NICKI LOCKERSUMMER<strong>2003</strong>because she was so tough in her questions. Only now doeshe fully appreciate what she did. "One of the most importantthings about lawyering is the ability to change behaviorso it's more compliant with the law," he says. "She personifiesthat ability."Notwithstanding the court victory, Network Associates'case is far from over. The company's former controller pledguilty in June to charges of securities fraud. That plea wouldcause headaches for any litigator defending a securities classaction, but at least Locker's credibility is still intact.weekend retreat in Southern California. Over the next fewweeks they interviewed 20 more. The team read over thousandsof pages of sales contracts and accounting documents.The moment of truth came on April 18-78 days afterLocker first learned that something was amiss-when shepresented the findings of her investigation in an informalhearing before six members of the SEC. She laid out all thetransactions that need to be restated. She provided the SECwith the number of employees who had been terminated forquestionable behavior, described their roles, and then told of"One of the most important things aboutlawyering is the ability to change behavior so it's morecompliant with the law," says a client of Locker's."She personifies that ability.""The facts in this case have only gradually come to light,but I've always been confident that she is upfront about thebasis of her knowledge," Gans says. "And in the process shehas done a great job for her client."Cooperating with the SECProof that being open can be the best defense is perhapsbest seen not in a case brought by plaintiffs' lawyers butwhen the SEC is knocking at a company's door. And withCritical Path, Locker embraced that approach.On the day the company's stock stopped trading, Lockerknew that if the SEC brought a §1O(b)5 enforcement action,essentially a fraud charge under the securities laws, it wouldbe fatal to the company. With the company's blessing, sheset out to do an investigation that would satisfy the commissionrather than try to deflect its inquiry.In the past, corporate defense lawyers didn't always conductan internal investigation when accounting problemswere discovered. They didn't want to be doing any work forthe plaintiffs' lawyers. In February 2001, the plaintiffs'lawyers were circling Critical Path, but Locker knew thatthe best thing she could do to defend the company was toair its dirty laundry and clean up its practices so thoroughlythat the SEC would see no need to take further action."We had to establish our credibility," she explains. "Wewanted to hand over the fruits of our investigation and haveit wrapped up for them. We needed to show that CriticalPath had become a good corporate citizen."In the first weekend after the emergency board meeting,Locker, with assistance from colleagues, interviewed 30employees in Critical Path's sales department, who were at athe new managers who had heen recruited. She detailed thenew accounting systems that would ensure that revenueswould not be counted until sales were fully completed. Andshe pointed to other changes in corporate governance,among them new internal auditing practices, that wouldprevent fraudulent practices from occurring again.The SEC accepted most of Locker's findings. And inFebruary 2002, in return for the company's having owned upto the problems, the agency settled the case with its mostlenient cease-and-desist order. No fines were levied, nosanctions imposed.The result is that Critical Path is alive-an outcome thatwas once very much in doubt. The company avoided bankruptcy,and it held on to customers who had been understandablywary about buying its products. While it's a muchsmaller company-in the number of employees and itsambitions-than two years ago, it remains in business.And Locker's handling of the case now looks like it was ablueprint for the SEC on what to expect from companiesunder serious scrutiny. Seven months after her appearancebefore the commission, the agency issued a report on the"relationship of cooperation to enforcement decisions." Itsays that the commission, when considering enforcementactions, will take into account the company's response to thecrisis: "Did the company commit to learn the truth, fullyand expeditiously? ... Did the company promptly makeavailable to our staff the results of its review? ... Whatassurances are there that the conduct is unlikely to recur?"When Locker worked the Critical Path case, she coveredevery point that the SEC's five-page report lists. Indeed, it'sa report that could have heen written by Nicki Locker.

17STANFORDLAWYERSOME RIGHTS RESERVEDIn the copyright war, Creative Commons seeks the middle ground between total control and total mayhem.ANITA IS A MUSICIAN WHO LIVES IN NEW YORK. SHE RECENTLY COMPOSEDAND RECORDED A SONG CALLED "VOLCANO LOVE."I love to jam!BY JONATHANRABINOVITZ"MMM ... FREE SAMPLES!"rom an office in the basement of <strong>Stanford</strong> Law School, Glenn Otis Brown posted thatmessage on the Web on March 11 to announce his latest project. The goal? To make iteasier for the author of a work, regardless of the medium, to give permission to othersto reuse that work in a book, a collage, a remix, or a film.Brown spent the next few weeks preparing a copyright license that automatically permits "sampling."The 226-word first draft was produced with pro bono assistance from Catherine Kirkman'89, an intellectual property lawyer at Wilson, Sonsini, Goodrich & Rosati. It was, in somerespects, the sort of technical, legalistic task that makes up the bread and butter of a corporate IPpractice. "Subject to the terms and conditions of this license," it begins, "licensor hereby grantsyou a worldwide, royalty-free, non-exclusive, perpetual ... license to exercise the rights in theWork as stated below."Cartoons concept and design by Neeru Paharla. Original illustrations by Ryan Junell. Photos by Matt Haughey. Some rights reserved. [See caption, p. 21.]

18SUMMER<strong>2003</strong>ANITA UPLOADED "VOLCANO LOVE" TO HER WEBSITE. SHE ALSO DECIDED TOGET A CREATIVE COMMONS UCENSE TO LET HER RETAIN HER COPYRIGHTWHILE ALLOWING CERTAIN USES OF HER SONG.I www.amta.comAnita's Music SiteDownloads:VolcanoLove.mp3ANITA WENT THROUGH THE UCENSING APPUCATION AND ANSWERED THREESIMPLE GUESTIONS ABOUT WHAT PERMISSIONS AND RESTRICTIONS SHEWANTED FOR HER SONG. THE WEBSITE POINTED HER TO THE UCENSE THATREFLECTED HER PREFERENCES.Read a detailed list of the rights common to an Crratlvc Commoo5 Uq:o:u:s. You may also want to reDo you want to:Require attribution? (~I;l])• YesRequire attribution? Yeah. I wantcredit for my song. Allow commercialuse? No. I don't want people makingmoney without asking me first. Allowmodifications? Sure, as long as theyare required to share alike.Allow modifications of your work? (~r;dl)o YesYes, as long as others share alike (~ I;l]INo(Select a Unrue)But the sampling license then veers off into unchartedterritory, becoming almost a Dadaist manifesto expressed incopyright lingo. It essentially gives a green light to thosewho wish to use the licensed art to create a "derivativework," while denying permission to others who merely aretrying to profit from copies. In Brown's eyes, this is morethan just another license or an academic exercise: it's a steptoward building a movement to protect and to expand thepublic domain-and freedom of expression.Brown, a soft-spoken 29-year-old Texan with a HarvardLaw degree, is the executive director of Creative Commons,a nonprofit organization that <strong>Stanford</strong> Law ProfessorLawrence Lessig helped establish two years ago. The groupaims to build an alternative to what it contends is an increasinglyrestrictive copyright regime. "Copyright that's moderate,"Brown explains in an interview in July. "An alternativeto either mayhem or total contro!."The interest in developing a sampling license, for example,arises from the difficulties that artists now face in "borrowing"from the works of others. AJthough incorporatingand building on the contributions of previous generations isa time-honored practice, it increasingly requires talking to alawyer, filling out forms, detailing the use, and paying a feebefore approval is granted. Many artists ignore the bureaucracyand take their samples, figuring that such use is permittedunder copyright law. Indeed, in many cases, no problemarises. But many others are threatened with lawsuitsunless they desist."There's this huge gray area that's hard to predict,"Brown says. "Are we comfortable with saying that a largepercentage of the culture being created today is illega1?"Some rights reserued.Those three words may be the quickest way to sum upthe Creative Commons philosophy. If the battles over downloadingmusic for free from the Internet have often turnedcopyright on its head, Creative Commons is turning copyrighton its side. Creative Commons accepts the idea thatsome people are going to want the full range of protection"all rights reserved"-while others will opt for no protectionat al!. Creative Commons seeks to provide a voluntaryoption for those who fall in the middle.The group was established in 1999 after Eric Eldred,who had created an online library for texts of books in thepublic domain, suggested it to Lessig. The cyberlaw expertwas already representing Eldred in a challenge to the mostrecent extension of the copyright term. (The SupremeCourt rejected that challenge in January <strong>2003</strong>.) But evenbefore that defeat both men had recognized that preventinga longer copyright term was, by itself, insufficient to build astrong public domain. Lessig, who is also the founder of the<strong>Stanford</strong> Law School Center for Internet and Society,agreed to serve as Creative Commons's chairman.Creative Commons allows creators ofintellectual property to obtain online alicense that they can append to their work.Instead of using the traditional copyrightsymbol, those who adopt a CreativeCommons license mark their work with acircle surrounding two C's. Although theselicenses come in various flavors, they allspecify ways in which the work can be copiedand reused. And the distinctive licenses not only comein both lay-language and technical-legalese versions, but alsoin machine code. This means that it will be possible to do asearch on the Internet for, say, all photographs of the SanFrancisco skyline that are available for free reuse.

II19STANFORDLAWYERANITA PUT THE DIGITAL CODE INTO THE HTML OF HER SITE. THE DIGITALCODE DISPLAYS THE "SOME RIGHTS RESERVED" BUTTON ON HER SITEAND UNKS TO HER UCENSE.Cool! Now it'sreally clear howI want people touse my song.I www.anlta.comIGNACIO IS A FILM STUDENT IN SAN FRANCISCO. HE'S LOOKING FOR ASONG TO PUT IN HIS CLASS FILM PROJECT, SO HE SEARCHES FOR"NONCOMMERCIAL SONGS." THE SEARCH ENGINE FINDS THE DIGITALCODE ON ANITA'S SITE AND TELLS IGNACIO ALL ABOUT HER WORK.Creative Commons is not the only group developingsuch licenses. The Electrorric Frontier Foundation has onein place specifically for audio copying. A group at theMassachusetts Instimte of Technology has been experimentingwith its own version. Creative Commons, however, isprobably the biggest effort, having raised $2 million ingrants from the Center for the Public Domain and the JohnD. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.So far, roughly one million works have been placed undera Creative Commons license, though the exact number is notImown. The group does not charge a fee to those who downloada license, nor does it keep a database of the visitors whohave done so. Lessig explains that Creative Commons wantsit to be easy for the average person to get and use a license."This has to be a lawyer-free zone," he says.In fact, getting a Creative Commons license is quick andpainless. Upon arriving at the site (www.creativecommons.org), one need only click on the "choose license" prompt,then answer a few yes-no questions: Do you want to requireattribution? Do you want to allow commercial uses of yourwork? Do you want to allow modifications of your work?And if you permit modifications, do you want to require thatthe modified work will be shared under the same rules asthis one? The visitor can then obtain a brief tag describingwhat conditions of reuse he is permitting, along with a linkto a more detailed version of the license on the CreativeCommons website. (There's an alternative label for hardcopyworks.)The concept is being put into practice by some notableartists and intellecmals. Roger McGuinn, a founder of therock band The Byrds, has used a Creative Commons licenseto permit noncommercial copying of several hundred folksongs that he has performed and placed on the L1ternet asMP3 files. Jerry Goldman, a political science professor atorthwestern <strong>University</strong> who founded the Oyez Project,which maintains an archive of recordings of Supreme Courthearings, in June placed several hundred hours of HighCourt arguments online, using a Creative Commons licenseto signal that they are available for copying.But equally important, the licenses are being embracedby artists and musicians who have yet to achieve notoriety.Colin Mutchler, a guitarist, wrote to Creative Commons inJuly that he had submitted a guitar track, titled "My Life,"to an online sound pool, Opsound, with a CreativeCommons license that permitted it to be reused and transformed,as long as the work was attributed to him and it wasfor a noncommercial use. One month after the track hadbeen posted, he received an e-mail from a 17 -year-old violinist,Cora Beth, who had added a violin track to his guitar.She called the new version, "My Life Changed.""I think the track is definitely more beautiful," Mutchlerwrote. "Maybe eventually we'll add drums and words."Lessig predicts that by the end of the year more than 10million works will be under Creative Commons licenses.That's an insignificant number viewed in the context of thebillions of works under traditional copyright, but Lessig saysit will demonstrate mass support that will encourageCongress to change existing copyright law. He is championinga bill, the Public Domain Enhancement Act, thatwould require copyright holders to register their works after50 years if they want them to be protected for the remainingyears of the term. All works that are not registered wouldenter the public domain.The idea that a grassroots movement is building overcopyright may sound odd. As many law school graduates willattest, copyright isn't exactly the most glamorous subject inthe curriculum. In writings and lectures, however, Lessigpresents the issue as one that cuts to the heart of sustainingfree expression and a free culmre in the 21st cenmry. While

20SUMMER<strong>2003</strong>• IIGNACIO GOES TO ANITA'S SITE AND USTENS TO ·VOLCANO LOVE.·WHEN HE'S DONE HE CUCKS ON THE CREATIVE COMMONS ·SOME RIGHTSRESERVED· LOGO.This song is great! It willfit perfectly into my film!What's this' CreativeCommons Some RightsReserved' logo?WHEN IGNACIO CUCKS THROUGH, HE SEES THE COMMONS DEED, THEHUMAN-READASU: EXPRESSION OF THE UCENSE THAT INCLUDES INTUITIVEICONS AND PLAIN LANGUAGE.This is easy to understand.I can use her song as long asI give her attribution. don't,..----------i'I------i make money. and share anyversions of a derivative workQcreative with the world.~convnonsCOM"U'!t 1)110I wwwantta,com...tui.....I_-N-eom-.u..·Sh......uiIll..1-0many copyright lawyers complain that the problem is piratesstealing music and movies on the Internet, Lessig points tofundamental changes in law, technology, and the economythat have led to what he calls an unprecedented concentrationof ownership and control of intellectual property."Never in our history has there been a fewer number ofactors exercising more control over our culture," Lessig saidin his July 2 lecture at the Internet Law conference at theLaw School. "This is a fundamentally different creative contextthan ever before: our free society has become a permissionsociety, our free culture has become an owned culture."Lessig notes that not only have copyright terms grownlonger over the past three cenmries (from 14 years to 95 yearsor the author's life plus 75) but so has the scope. Copyrightlaw now prohibits any "copying," not just commercial republishing.More important, works are automatically covered bycopyright at their creation instead of the original system thatrequired creators to register their works to be covered.Lessig adds that increasing concentration of media ownership-andcopyright ownership-leads to even less likelihoodof works being shared for free. And this is vastly magnifiedby the rise of tile Internet. Although the Net at firstled to widespread disregard of copyright, it now is helpingestablish even greater control, Lessig says. As society reliesmore on intellectual property in digital form, intelJecmalproperty is increasingly being distributed with embeddedcodes that make reuse difficult, if not impossible-evenwhen such uses are lawful."We're moving from one extreme to another," Lessigdeclares. "This has become a debate framed by extremiststhepeople who say copyright controls all rights and me peoplewho say there shouldn't be any at all." But mere is also athird, middle group. He explains, "There are people whodon't believe in all rights or none, but believe in some."The sampling license mat executive director Brown has beencrafting is one of several new licenses that Creative Commonsis developing that offer new ways to preserve some rights. Theneed for a sampling license has grown more apparent inrecent years, though decades ago mere was little need for it.As Lessig frequently mentions, Walt Disney borrowed fromthe Bromers Grimm and other artists to create many of hisgreatest films.Still, a recent situation involving Bob Dylan demonstrateshow sampling is now being mistaken for tileft. Dylanis widely known to borrow lines from omer writers in composinghis own works. But in July the 'Wall Street ]Olwnal rana front-page story suggesting that his song "Floater (TooMuch to Ask)" plagiarized a little-known Japanese novel,C011fessio77s ofa Yakuza. In response to the ensuing controversy,Ne7v York Times music critic Jon Pareles wrote that interspersinglines from another text into a larger composition is typicalof what Dylan has often done: "Writing songs that are informationcollages." Pareles adds that such a practice was onceseldom challenged, but that the widespread availability ofmusic on the Internet had led many copyright holders toreact by reaching even further in asserting their rights andrestricting sampling.The challenge for Creative Commons is to come up with alicense that accurately stakes out mis allegedly imperiled territory.And developing me language so tllat it can satisfy bothlawyers and artists is no easy task. On May 23, Brownlaunched a discussion about it with a dozen or so people whosigned up and shared their comments with each omer via email. The review was supposed to have ended four weeks later,but as of mid-July remarks were still flying back and fortll.Don Joyce, a member of an experimental music and artcollective called Negativland that composes in "found sound,"moderated the conversation. Anlong the other participantswere a singer who says she edited Timothy Leary's last novel,

• • 22STANFORDLAWYERWITH ANITA'S UCENSING TERMS IN MIND, IGNACIO LAYS HER TRACK DOWNOVER A SCENE AND WRAPS UP HIS FILM.IGNACIO SHOWS THE NEW CUT OF HIS MOVIE TO HIS FILM CLASS ANDMAKES SURE TO MENTION ANITA IN THE CREDITS.a consultant from a multimedia design smdio, an anthropologyprofessor, and Kjrkman, the Wilson Sonsini partnerwho helped draft the license and is a self-described"copyright geek."One artist raised an objection that a phrase in the]icense-"highJy transformative"-was too vague indescribing what a derivative work is. Kjr!cman answered,"We would go down a legal rat hole trying to define theseterms." And she added, "At some point you end up relyingon a reasonable interpretation of the words that you use."Another participant questioned whether the creator of thederivative work should be required to include an attributionto the artist whose work was borrowed. And thenmany in the group expressed confusion over what happensin a situation in which a derivative work is placed underthe license and then a new derivative work is made. Wasthe creator of the new work under obligation to identifyand get permission from the contributors to the previouswork if the previous artist had not done so?The license and these questions are of more thanabstract interest to Joyce. His collective, Negativland, wassued in 1991 by Island Records for sampling a song fromthe label's band, 2. Negativland's recording was pulledfrom circulation to put an end to the legal wrangling. Sofor Joyce the discussion goes to the heart of how freeexpression can be encouraged today. "How much practicaluse [the new license] will be, we shall see," he says. At thevery least, he adds, "It's bridging the concept gap."Kirkman agrees that this and the other CreativeCommons licenses are pushing the envelope. She spendsmost of her work time developing copyrights for newtechnology products that will protect private interests."Those are fine and noble interests," she says. "But Iwanted to be involved in this discussion because it's on thecutting edge: we're exploring how to use the copyrightIGNACIO UPLOADS THE FINAL VERSION OF HIS FILM TO HIS OWN SITE.SINCE ANITA APPUES THE SHARE AUKE PROVISION TO HER SONG,IGNACIO UCENSES HIS OWN MOVIE UNDER THE SAME TERMS ANITAOFFERED HIM: ATTRIBUTION, NONCOMMERCIAL, AND SHARE AUKE. HEGOES TO THE CREATIVE COMMONS SITE AND GETS THE SAME UCENSEAFTER PERSONAUZING HIS DIGITAL CODE TO DESCRIBE THE MOVIECreative Commons has helped mecollaborate with someone I don'teven know. Now others can usemy film under the same termsII www.lgnaclo.comIgnacio's Film SiteDownloads:IAnacio·sfilm.movCreative Commons has translated this cartoon into Japanese and Finnish aspart of a broader effort to make its licenses available worldwide. The strip isunder an "Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike" Creative Commons license.This permits people to copy it for free, without asking, as long as they creditthe artists and Creative Commons and do not use it for commercial purposes.Also, the license requires that if someone uses it to create a derivative work,that derivative work must also have a license that allows it to be copiedunder the same conditions as the original cartoon. For the complete versionof this strip, plus another one that explains the different licenses, go tohttp://www.creativecommons.org/learn/licenses/.framework for the public interest."The new license is expected to be approved by theCreative Commons board by the end of the summer. It maywind up being only of interest to avant-garde artists andcopyright lawyers. It could end up little more than a footnotein a fumre scholarly treatise on the history of copyright.Then again, maybe Bob Dylan or some other superstarwill learn about it and place the double C symbol on hisworks. And if one such artist takes a stand, then perhapsthousands more will follow.Besides, there's nothing lost by thinking creatively.