Moruga Bouffe - The Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists' Club

Moruga Bouffe - The Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists' Club

Moruga Bouffe - The Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists' Club

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

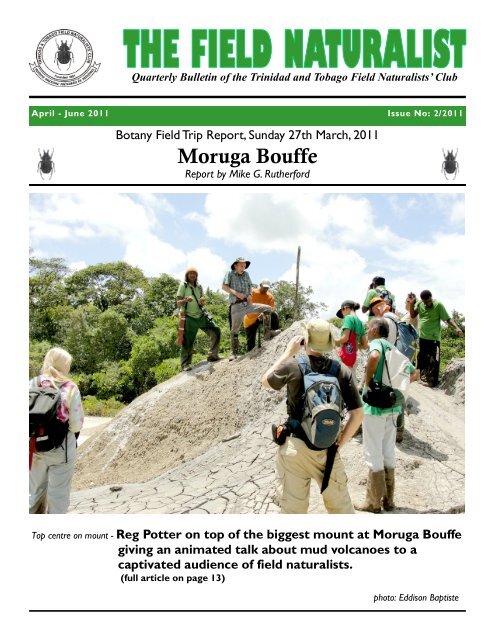

Quarterly Bulletin of the <strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong> <strong>Field</strong> Naturalists’ <strong>Club</strong>April - June 2011Botany <strong>Field</strong> Trip Report, Sunday 27th March, 2011<strong>Moruga</strong> <strong>Bouffe</strong>Report by Mike G. RutherfordIssue No: 2/2011Top centre on mount - Reg Potter on top of the biggest mount at <strong>Moruga</strong> <strong>Bouffe</strong>giving an animated talk about mud volcanoes to acaptivated audience of field naturalists.(full article on page 13)photo: Eddison Baptiste

Page 2 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011134Inside This IssueCover<strong>Moruga</strong> <strong>Bouffe</strong><strong>Field</strong> Trip Report, 27th March 2011- Mike G. Rutherford(full article on page 13)<strong>The</strong> Conflicted Nataurlist- Christopher k. StarrPart 3. Black FliesQuarterly Bulletin of the <strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong> <strong>Field</strong> Naturalists’ <strong>Club</strong>April - June 2011EditorsEddison Baptiste, Elisha Tikasingh (assistant editor)Editorial CommitteeEddison Baptiste, Elisha Tikasingh,Palaash Narase, Reginald PotterContributing writersChristopher Starr, Elisha Tikasingh, Hans Boos,Lester Doodnath, Mike Rutherford, Natasha Mohammed51819- Elisha S. TikasinghMonos Isl<strong>and</strong>- Lester W. Doodnath- Natasha A. Mohammed- Christopher k. StarrBook Notice- Christoper K. StarrWe Go to Grenada 1975Feature Serial (part 1b)- Hans Boos23 Management Notices24Notes to ContributorsEditor’s noteMany thanks to all who contributed <strong>and</strong> assistedwith articles <strong>and</strong> photographs.CONTACT THE EDITORWeb Email Facebook DownloadsWebsite:PhotographsEddison Baptiste, Mike Rutherford,Natasha MohammedDesign <strong>and</strong> LayoutEddison Baptiste<strong>The</strong> <strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong> <strong>Field</strong> Naturalists’ <strong>Club</strong> is anon-profit, non-governmental organizationManagement Committee 2011 - 2012President ……………... Eddison Baptiste 695-2264Vice-President ……….. Palaash Narase 751-3672Treasurer…………….. Selwyn Gomes 624-8017Secretary ………...…... Bonnie Tyler 662-0686Assist-Secretary ……... Paula Smith 729-8360Committee members ... Ann M. Sankersingh 467-8744http://www.ttfnc.orgPostal: <strong>The</strong> Secretary, TTFNC, c/o P.O. Box 642,Port-of-Spain, <strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong>Email:Contact us!admin@ttfnc.orgDan Jaggernauth 659-2795Mike Rutherford 329-8401Disclaimer:<strong>The</strong> views expressed in this bulletin are those of the respectiveauthors <strong>and</strong> do not necessarily reflect the opinion <strong>and</strong> views ofthe <strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong> <strong>Field</strong> Naturalists’ <strong>Club</strong>

Page 3 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011THE CONFLICTED NATURALISTby Christopher K. StarrUniversity of the West Indiesckstarr@gmail.comMy house, like Victor Quesnel's, is a sort ofwildlife sanctuary. Mosquitoes, non-nativecockroaches <strong>and</strong> most termites are unwelcome,but just about everybody else is at leasttolerated. Three species of geckos (<strong>and</strong> theoccasional skink) leave their, uh, leavings onthe floor, a small price to pay for the pleasureof their squeaking, scurrying company. For atime the house was home to a Cook's treeboa, whom I would encounter in unexpectedcorners. <strong>The</strong> snake was quite a bit messierthan the unamused lizards, but I was sure hewas worth it.In some years house wrens nest inside. <strong>The</strong>y are certainlyprejudicial to good housekeeping, but so what?<strong>The</strong>y are such delightfully lively little birds that onecan forgive them all manner of sins.A short-tailed fruit bat roosted in the bathroom forsome months. <strong>The</strong> bat sometimes brought fooditems into the house, dropping the uneaten parts onthe floor, so that I was able to see what it was eating.(I believe Victor once did a study of the feeding habitsof bats roosting in his house.) My bat dropped a greatmany pwa-bwa (Swartzia pinnata) seeds after chewingoff the sweet white ariloid. This corroborated myhypothesis that pwa-bwa seeds are bat-dispersed.Tarantulas <strong>and</strong> web-building spiders are certainly present.Every now <strong>and</strong> then I clean old, disused silkfrom the ceiling, trying not to damage or even inconveniencethe little eight-legged darlings. All arachnidsare welcome in Obronikrom.Many other beasts w<strong>and</strong>er indoors for much shorterperiods. I get nocturnal maribons at the lights.Whacking big robust cockroaches fly in the windows,skedaddle about <strong>and</strong> then depart. Moths often comein, stay at rest through the day, <strong>and</strong> fly back out whennight returns.Besides these, two social wasps nest inside from timeto time, <strong>and</strong> these <strong>and</strong> several others nest on the outsideof the house, along with mud-nesting solitarywasps, carpenter ants, stingless bees <strong>and</strong> the occasionalorchid bee. Although I have never seen eitherof them inside the house, army ants raid across thepatio a couple of times a year, <strong>and</strong> bachac columnswalk along the edge every night.On 6 April I awoke to notice three unaccustomedwasps clinging to the ceiling over my head. Now, thatwas interesting, so I did exactly what you would do. Ipicked up some plastic vials, collected the wasps, <strong>and</strong>then whipped out my h<strong>and</strong> lens. It was Agelaia multipicta.This widely-distributed maribon is far fromcommon in <strong>Trinidad</strong>. I encounter a colony on averageless than once a year, so I was happy to get specimensright at home.When I came home that evening I noticed severalmore on the ceiling <strong>and</strong> flying about the lights. Itstruck me that there must be a new colony nearby.Not exactly. It wasn't near the house but right insideit. <strong>The</strong> next morning I happened to look into thespare bathroom <strong>and</strong> met a truly striking sight. <strong>The</strong>rewas a great mass of wasps hanging in clusters on thefar wall, spread over the ceiling <strong>and</strong> especially dense inthe angle between them, where they had already begunto build combs.My immediate reaction was sharp delight. Hot damn!A real live Agelaia colony right there in my ownhouse. And then, very quickly, I had misgivings. This<strong>and</strong> some other Agelaia species build huge colonies --this founding swarm appeared to comprise severalthous<strong>and</strong> individuals -- <strong>and</strong> they are not docile whendisturbed. I have been stung by several species, <strong>and</strong> itis always painful. A. multipicta (<strong>and</strong> possibly mostmembers of the genus) have barbs on the stinger, sothat it remains fixed in the wound, where it keeps on(Continued on page 9)

Page 4 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011Annoying <strong>and</strong> Blood Sucking Arthropods of <strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong>3. Simulium Black Fliesby Elisha S. Tikasinghelisha.tikasingh@gmail.comBlack flies, Simulium, are sometimes mistakenly called s<strong>and</strong> flies probably becausethey are small, usually less than 5.0 mm in length. While many members of thisgroup are black, there are others that are grey, yellow or orange. <strong>The</strong> antennae<strong>and</strong> legs of a black fly are short, the thorax is somewhat arched giving it ahump-backed look, <strong>and</strong> their wings are clear.<strong>The</strong>se black flies are called buffalo gnats in theU.S.,cabouri or kabowra flies in Guyana, pium inBrazil <strong>and</strong> congo flies in <strong>Trinidad</strong>. <strong>The</strong>ir bites arevery painful <strong>and</strong> very more so than the s<strong>and</strong> flies.This is due to their mouth parts which containblade-like lancets which macerate the skin at thebite site causing intense pain. <strong>The</strong> saliva introducedin the bites cause an allergic reaction with severeitching <strong>and</strong> swelling. )Simulium Black Flyfeeding on human armPhoto: Elisha TikasinghEffects of Black Fly bites.Initial bite may be accompanied by a red spot(shown in circles) <strong>and</strong> later by local swelling.Photo: Elisha TikasinghBlack flies breed in fast running streams, creeks <strong>and</strong> riverswhere the water is well aerated. <strong>The</strong>y will not breed inponds <strong>and</strong> stagnant water. Eggs are deposited in massesnear rocks, aquatic vegetation <strong>and</strong> other objects in thewater which the larvae cling to on hatching.(Continued on page 4 )Back Fly larva on vegetation.Next to it is an empty pupal skinPhoto: Elisha Tikasingh

Page 5 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011(Continued from page 3)<strong>The</strong> larvae undergo six moults <strong>and</strong> then spins acocoon for pupal development. <strong>The</strong> pupa containsmany filaments which are very diagnostic to thespecies level.Staff of the <strong>Trinidad</strong> Regional Virus Laboratory havecollected <strong>and</strong> identified seven species mainly fromthe rivers of the Northern Range (CAREC unpublisheddata). Based mainly on adult morphology thefollowing species were: Simulium clarki, S. metallicum,S. placidum, S. incrustatum, S. sp. near incrustatum, S.samboni <strong>and</strong> S. subnigrum).In <strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong>, black flies are not known tocarry any disease, but elsewhere such as northAmerica in the spring <strong>and</strong> summer months theyemerge in such large numbers that they annoyanimals preventing them from feeding resulting inemaciation <strong>and</strong> sometimes they may even enter thenostrils of the animals suffocating them causing theirdeaths. In Guyana, they also emerge in largenumbers during the rainy season so that people arereluctant to go in the interior <strong>and</strong> thus preventingdevelopment of the area.Back Fly cocoon stageimage found at:ttp://www.bgsd.k12.wa.us/hml/jr_cam/macros/upper_efl_f05/up_efl_f05a.html<strong>The</strong> adults are difficult to identify <strong>and</strong> generally onemust have the associated pupal skin for definitiveidentification. <strong>The</strong> next time you are at a mountainstream where the water is not polluted, check theleaves of vegetation or sticks submerged in thewater <strong>and</strong> you may find black fly larvae <strong>and</strong> pupae.<strong>The</strong> entire life cycle from egg to adult may take fromtwo to three months depending on temperature theof the water. Black flies are very robust <strong>and</strong> arestrong flyers <strong>and</strong> may be found far from theirbreeding sites. Adults are active during the day, <strong>and</strong>hardly enter homes.In West Africa, Central America <strong>and</strong> Venezuelaspecies of Simulium carry a threadlike filarial worm,Onchocerca volvulus to people living near rivers. <strong>The</strong>adult worm live in subcutaneous nodules on thejoints or trunk (Africa) <strong>and</strong> shoulders <strong>and</strong> head(Central America <strong>and</strong> Venezuela) from where theyproduce larvae called microfilariae which arereleased to other parts of the body. Some of themicrofilariae may enter the eye causing blindness<strong>and</strong> the disease known as ―river blindness‖ oronchocerciasis. When one sees pictures showing―the blind leading the blind‖ the blindness in theseindividuals is usually due to onchocerciasis.In Guyana <strong>and</strong> the Brazilian Amazon, Simuliumspecies of the amazonicum group (now identified asS. oyapockense) are vectors of the filarial wormMansonella ozzardi to humans (Nathan et al. 1982,Shelley et al. 1980, Shelley et al. 2004). Infection withMansonella ozzardi may cause articular painparticularly in adults.Control is by killing the larvae at its breeding sites.Fogging with an appropriate insecticide givetemporary relief. Personal protection is by the useof insect repellents.(Continued on page 12)

Page 6 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011Botany <strong>Field</strong> Trip Report, Saturday 8th March, 2008Monos Isl<strong>and</strong>Report by Lester W. Doodnath <strong>and</strong> Natasha A. MohammedMonos Isl<strong>and</strong> Group Shoot ( Left to right )photo: Natasha MohammedFront row : Winston Johnson, Stephen Smith, Esperanza Luengo, Shane Ballah, Nicholas See Wai,Juanita Henry, Jo-Anne Sewlal, Betsy Mendez, Lester DoodnathSecond row: Bobby Oumdath, BonnieTyler, Ray Martinez, Christopher Starr, Kayman SagarBack row: Richard Peterson, Sheldon Brown, Michael GreenDuring early Spanish times the isl<strong>and</strong>of Monos was inhabited by Red HowlerMonkeys (Alouatta seniculus) whicheven at that time would have led aprecarious existence due to little foodor water being present on the isl<strong>and</strong>(de Verteuil 2002). <strong>The</strong>se monkeyswere soon extirpated <strong>and</strong> cottongrowing was practiced together withsubsistence fishing.<strong>The</strong> avid botanists of this group learnt that onMonos that dry vegetation was normally found.According to Beard (1946) the deciduous seasonalforest originally present would have been afasciation of the Bursera–Lonchocarpus association(Continued on page 7)

Page 7 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011Monos Isl<strong>and</strong> Lester Doodnath, Natasha Mohammed(Continued from page 6)which would have been the Protium-Tabebuiaecotone.Our objective was to look for Bursera latifolia whichis the other species of Naked Indian (B. simaruba –with a papery, peeling bark). B. latifolia can be differentiatedfrom B. simaruba by the leaves <strong>and</strong> flowers.However during this dry season visit all the leaves ofthese deciduous trees had fallen <strong>and</strong> telling the twospecies apart was not possible.<strong>The</strong> first plant that caught our attention was theterrestrial Anthurium genmanii which has a normalpresence here. Also terrestrial was Bromeliaplumeria <strong>and</strong> B. pitcairnia seen growing on rocks.Calli<strong>and</strong>ra krugerii was seen growing as a st<strong>and</strong> oftrees. Incense (Protium guianense) is part of thecharacteristic fasciation, when the leaves arecrushed you get the characteristic smell of incense.Balsam (Copaifeira officinalis) normally has smoothbark. <strong>The</strong>n we observed a fruiting Balsam tree withatypical bark that was not smooth. Why was thiswe wondered? Different isl<strong>and</strong> conditions? Wesaw that Capparis hastate has waxy shiny alternateleaves <strong>and</strong> that Ouratea guildingi has yellow flowers.On the leaves of Amyris simplicifolia you see dots thatindicate that it belongs in the citrus family, Rutaceae.You can tell this because when the leaves arecrushed you get that characteristic smell.Orchids observed included the Brown bee Orchid(Oncidium altissimum), Oeceoclades maculata <strong>and</strong>Spiranthes sp. <strong>The</strong> three-angled epiphytic cactiAnthocereus pentagonus has edible juicy fruit.According to Hans Boos we were on the road thatgoes around Monos to an area that the Americanscalled ―Saucey‖ which was a recreation location.We examined a Cat’s Claw (Macfadyena unguis-cati)vine <strong>and</strong> flowers, whose leaves are glossy green withtwo leaflets per petiole <strong>and</strong> has a 3-prongedclaw-like climbing appendage. <strong>The</strong> flowers aresolitary, bright yellow, funnel-shaped, <strong>and</strong> have ashort blooming during the dry season.Indicative of the seaside vegetation of the westernisl<strong>and</strong>s was Manchineel (Hippomane mancinella),Black mangrove (Avicennia germinans), WhiteMangrove (Laguncularia racemosa) <strong>and</strong> ButtonMangrove (Conocarpus erectus). Button Mangrovecan be told from the White Mangrove due to thestriations on the bark.<strong>The</strong>n we saw Pithocellobium roseum which hasprickles on the bark. This was the first sighting forMonos <strong>and</strong> it was flowering in March. It had pinkflowers <strong>and</strong> the pods were also observed.Diospyros inconstans is indicative of dry forest <strong>and</strong>was in fruit. Jacquinia sp is coastal, together withHibiscus pernambucensis (hairy leaves) <strong>and</strong> <strong>The</strong>spesiapopulnea (smooth leaves). Erythroxylum havanense<strong>and</strong> Citharexylum sp were found by the jetty alongthe coast <strong>and</strong> indicative of the dry forest type.We met Mr. Peter Tardieu in his garden near aformer coconut estate where he grew various fruitcrops. He spoke to us of issues of tenure for thisarea where before he had a lease for 20 years.Close by there is a marker by the US EngineerDepartment from the 1940’s.Non-avian fauna seen in <strong>and</strong> around this coconutestate were the Cracker (Hamadryas sp.) <strong>and</strong>Emperor butterflies (Morpho peleides). Ray Martinezcollected specimens of the coastal mosquito(Deinocerites magnus) from crab holes. An Ameiva(Ameiva ameiva) lizard was observed here. <strong>The</strong> skullof a Caiman (Caiman crocodilus) was found by acolonial wall that the Siegert Family had built.ConclusionQuesnel (1996) reported a total of 34 plant species,as compared to a total of 47 species, in this brief,one-day, study (2008). Differences in number ofspecies may be attributed to the length of timespent in the field, seasonal abundance, floweringspecies present, which would be attributed to stagesof maturity <strong>and</strong> seasons- time of the year. <strong>The</strong> trailsexplored by parties on both occasions, may also(Continued on page 8)

Page 8 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011Monos Isl<strong>and</strong> Lester Doodnath, Natasha Mohammed(Continued from page 7)have differed <strong>and</strong> presented differences incomposition. Although we did not find what we setout to for on this expedition, this present (2008)study revealed species indicative of Beard’sProtium-Tabebuia ecotone.Fruit of the Balsam TreePhoto: Natasha A. MohammedAcknowledgments<strong>The</strong> authors wish to express their deepest gratitudeto Mr. Winston Johnson of the National Herbariumfor both his field expertise, his knowledge inidentifying the vegetation <strong>and</strong> his cooperative spiritwith assisting with the spelling of such, during hisvacation.References:Barcant, M. 1970. Butterflies of <strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>Tobago</strong>. London: CollinsBeard, J. S. 1946. <strong>The</strong> Natural Vegetation of<strong>Trinidad</strong>. Oxford: Oxford University Press.De Verteuil, A. 2002. Western Isles of <strong>Trinidad</strong>.Litho Press, <strong>Trinidad</strong>.Quesnel, V. 1996. List of Plants seen on MonosIsl<strong>and</strong>. UnpublishedLester W. Doodnath next toBalsam Tree TrunkPhoto: Natasha A. MohammedFor comparative species listing of plants found on Monos Isl<strong>and</strong> in 1996 <strong>and</strong> 2008 see Page 10

Page 9 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011Botany <strong>Field</strong> Trip Report, Saturday 8th March, 2008Bug Component - Monos Isl<strong>and</strong>Report by Christopher K. Starr<strong>The</strong> buggists present were Shane Ballah, JoAnneSewlal, Christopher Starr <strong>and</strong> Danny Velez. Asalways, we were on the lookout for novel instancesof ants attending homopterans or extra-floralnectaries for sugars. On this tripwe failed to find anything of the sort, butthere was good success in another endeavour.Microcerotermes arboreus is a very common termitein both <strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong>, where its characteristichard, gray-brown nests are often seen on treetrunks. It has long been known that the bee Centrisderasa nests in the nests of A. arboreus. <strong>The</strong> burrowsmade by the bee are often detectable at thetermites' nest surface. Microcerotermes indistinctus isphysically very similar to M. arboreus, such that thetwo are very hard to tell apart on the basis of thetermites, themselves. However, their nests arereadily distinguishable, first of all because M. indistinctusis only known to nest on the soil surface.<strong>The</strong>se are, then, true "ethospecies", i.e.reproductively isolated species that can easily betold apart through behavioural characters but notor hardly through physical characters. We havefound M. indistinctus on all three of the Bocas Isl<strong>and</strong>s<strong>and</strong> on the Chaguaramas Peninsula. It is especiallyabundant on Monos, <strong>and</strong> Shane <strong>and</strong> I had early takendata on nest structure <strong>and</strong> colony composition ofthe species there.Dissection of nests had also shown the presence ofcells closely resembling those of C. derasas, so it wasevident that this or a closely related species is foundin the nests of M. indistinctus. We collected 10more colonies in order to augment our earlier dataset<strong>and</strong> to search for bees that could be identified tospecies. We did well in gaining new data on thetermites, themselves. We found evidence of pastCentris use in three of the nests <strong>and</strong> a single activecell with a late larva. We are now trying to rearthis individual, in hopes of having an adult specimen.THE CONFLICTED NATURALIST(Continued from page 3)pumping venom. Al Hook would be coming to<strong>Trinidad</strong> for the summer, during which time thatwould be his bathroom. What kind of a host wouldleave a potentially dangerous colony of wasps toestablish itself right there where a guest performs hisablutions?So, very reluctantly, I concluded that the wasps had togo. It would have been so easy just to spray them,but it would also be dreadfully unprincipled.Whenever possible, a naturalist prefers to encourageunwelcome residents to move out unharmed bymaking the site less hospitable. For example, whenasked how to rid a building of bats, my advice is tosubject their roost to continuous light <strong>and</strong> abothersome breeze from an electric fan. Bats, I find,get the point <strong>and</strong> decamp within days.Dealing with it could not wait. A founding swarm hasonly a weak attachment to its chosen nest site, but astime passes <strong>and</strong> the colony builds a nest <strong>and</strong> fills itwith developing brood the attachment will becomemuch harder to break. Wasps with an investment todefend are ready to sting when it is threatened.So, I left the bathroom light on, put a mosquito coil toburning, <strong>and</strong> went to work. I returned this evening tofind the wasps gone, leaving intact their neat set offive parallel combs. <strong>The</strong> colony had absconded.Maribons tend not to swarm very far, so the colonyhas probably refounded within a few hundred meters.I look forward to locating its new nest sites <strong>and</strong>paying my wasps a visit.Christopher K. Starr

Page 10 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011Botany <strong>Field</strong> Trip Report, Saturday 8th March, 2008Comparative species listing of plantsfound on Monos Isl<strong>and</strong> in 1996 <strong>and</strong> 2008Report by Lester W. Doodnath <strong>and</strong> Natasha A. Mohammed

Page 11 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011Botany <strong>Field</strong> Trip Report, Saturday 8th March, 2008Comparative species listing of plants found on Monos Isl<strong>and</strong> in 1996 <strong>and</strong> 2008Continued from page 10

Page 12 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011Botany <strong>Field</strong> Trip Report, Saturday 8th March, 2008Bird list of botany trip to Monos Isl<strong>and</strong>Report by Matt KellyLeft to rightDan Jaggernauth<strong>and</strong> Winston JohnsonSt<strong>and</strong>ing next to an AlbesiaTree TrunkPhoto: Natasha A. MohammedSimulium Black Flies (Continued from page 5)ReferencesNathan, M.B., Tikasingh, E.S. <strong>and</strong> Munroe, P. 1982.Filariasis in Amerindians of Western Guyana withobservations on transmission of Mansonella ozzardiby a Simulium species of the amazonicum group.Tropenmedizin und Parasitologie, 33: 219-222.Shelley, A. J., Luna Dias, A.P.A., Moraes, M.A.P. 1980.Simulium species of the amazonicum group as vectorsof Mansonella ozzardi in the Brazilian Amazon. Transactionsof the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine <strong>and</strong>Hygiene, 74: 784-788.Shelley, A. J., Hern<strong>and</strong>ez, L.M. <strong>and</strong> Davies, J.B. 2004.Blackflies (Diptera: Simuliidae) of Southern Guyanawith keys for the identification of adults <strong>and</strong> pupae –A Review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro,99: 443-470.

Page 13 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011<strong>Field</strong> Trip Report, Sunday 27th March, 2011<strong>Moruga</strong> <strong>Bouffe</strong>Report by Mike G. Rutherford<strong>The</strong> usual early start on Sunday morning saw severalcarloads of people assemble outside the south gateof UWI. <strong>The</strong>re was some debate about which routewe were to take with most people assuming that wewould head south to San Fern<strong>and</strong>o then past PrincesTown <strong>and</strong> on to <strong>Moruga</strong>. However, it was announcedthat we would all head east to SangreGr<strong>and</strong>e <strong>and</strong> then down Manzanilla way, past GaleotaPoint <strong>and</strong> then through the Petrotrin checkpoint toaccess the road to <strong>Moruga</strong> <strong>Bouffe</strong> from the easternside. We arrived at our destination just after 10am.After the approximately 30 people had put theirboots on <strong>and</strong> slapped on sunscreen <strong>and</strong> bugrepellent we assembled at 10:20am. Dan Jaggernauth<strong>and</strong> Reginald Potter gave a brief talk about the walk<strong>and</strong> the destination. We were going to see the<strong>Moruga</strong> <strong>Bouffe</strong>, a mud volcano in the middleof the forest. A mud volcano happens whengas <strong>and</strong> mud rise up through a fault in theearth’s surface, when one occurs in a tropicalforest it forms what is called a tassik – anopen area surrounded by forest. In the tassik,which can be several acres across, gasbubbles up through craters of different sizes<strong>and</strong> shapes. On the way we were also goingto see one of the biggest trees in <strong>Trinidad</strong>.<strong>The</strong> group started the walk by heading along a partlyovergrown road, on the way there were several oldoil pumps which seemed to be a bit worse for wearbut were still slowly bringing up the precious blackliquid.Soon Dan had called his first halt, in the vegetationat the side of the road he had found some Zeb-a-pik(Neurolaena lobata) a shrub about 2 metres high withlong pointed leaves <strong>and</strong> clusters of small yellowflowers. <strong>The</strong> leaves <strong>and</strong> flowers can be used tomake a bitter tasting tea for the treatment of fever<strong>and</strong> menstrual pains, Bonnie Tyler tasted the flowers<strong>and</strong> confirmed they were bitter.Meanwhile Stevl<strong>and</strong> Charles was looking into aroadside ditch trying to locate the appropriatelynamed Windward Ditch Frog (Leptodactylus validus)which could be heard calling but was keeping itselfwell hidden. Up above several people spotted aPlumbeous Kite (Ictinia plumbea). This is a fairly easybird of prey to identify with its grey colouring <strong>and</strong>long wings projecting well beyond the tail. It has thehabit of perching on dead branches <strong>and</strong> feeding onflying insects caught on the wing. As we weresurrounded by butterflies, dragonflies <strong>and</strong> damselfliesalong the road I’m sure there was no shortageof feeding options for the kite.Just as we came to the end of the old road we hadone last exciting find before starting on the forestpath. In a shallow puddle covered in algae <strong>and</strong>rotting leaves I saw a slight movement which couldonly have been made by an animal. Treading carefullyI probed gently with my machete <strong>and</strong> waspleasantly surprised to find a small Common Galap(Rhinoclemmys punctularia). I picked it up <strong>and</strong> calledout for people to come <strong>and</strong> get a look <strong>and</strong> soon thewee terrapin was being photographed from allangles. Stevl<strong>and</strong> gave everyone a quick talk aboutthe animal <strong>and</strong> its habits <strong>and</strong> we debated whetherwe should take it down to the nearby stream ratherthan leave it in a murky puddle. However, afterdeciding that it may have just spent the last few daysgetting up from the stream I put it back where Ifound it.Almost as soon as we entered the forest the pathbecame very muddy <strong>and</strong> slippy <strong>and</strong> several membersof the walk started to find it hard going. <strong>The</strong>re was ametal sign put up by the Forestry Division saying,―Our forest is valuable. Two different forest typescan be seen on this trail Mora-Crappo <strong>and</strong> FineleafCarat. Look, Listen <strong>and</strong> Learn‖. As seems to be thefate of signs the world over wherever there arepeople with guns this one had been used as targetpractice with the forestry logo having been neatlyblasted out of the sign. Nearby in a rotting log I(Continued on page 14)

Page 14 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011<strong>Moruga</strong> <strong>Bouffe</strong> Mike G. Rutherford(Continued from page 13)found a couple of harvestmen, a type of arachnidwith very long legs. I took them back to the UWIZoology Museum to look at them under the microscope,I was amazed by their appearance, like miniaturetriceratops they had three large spines comingout the top of their bodies <strong>and</strong> this helped me toidentify them as a male <strong>and</strong> female Stygnoplusclavotibialis.<strong>The</strong> next botanical pause came when Dan foundsome fruits of the Toporite tree (Hern<strong>and</strong>ia sonora).This tree, which was often grown as a shade treefor cocoa, produces small fruits which when driedout have a small hole in the top allowing them to beused as a whistle hence its other common name ofwhistling fruit. <strong>The</strong> timber from the tree was oftenused for housing due to its strength <strong>and</strong> durability.Beside the edge of the path I observed some usedshotgun shells, the first of many we would find onthe walk. Although Petrotrin has attempted to imposea hunting ban in the area, the evidence seemedto suggest that it is not enforced. <strong>The</strong> path continuedover a very overgrown metal bridge which if ithadn’t been for the stream underneath would havebeen easy to mistake for just another part of theforest.Further along the trail Dan was showing everyonethe fruits of the Prickly Palm (Bactris major) whichgrows to around 4 metres high. From the samefamily as the coconut this tree produces small whitefruits which can be used to make an alcoholic drink,a juice <strong>and</strong> also processed to make oil.At this point a light rain started which did nothingfor the already treacherous mud. After a bit moreslipping <strong>and</strong> sliding <strong>and</strong> trying not to grab onto moreprickly palms <strong>and</strong> then scrambling across some fallenlogs to get past a very muddy part we suddenlyheard the cry of ―snake, snake‖ up ahead. Racingforward to get a look I found Stevl<strong>and</strong> using a longstick to move a juvenile Mapepire Balsain (Bothropsatrox) from off the path to behind a rotting log.Pausing to allow people to take photographs, from asafe distance of course, Stevl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> I put thevenomous snake down on the ground in order toget some close up shots <strong>and</strong> to observe itsbehaviour. <strong>The</strong> snake was quite easy going <strong>and</strong>allowed us to get several close up photographs.Juvenile Mapepire BalsainPhoto: Mike RutherfordWhen I had satiated my curiosity I looked up <strong>and</strong>realised that we were already at our firstdestination. Partly hidden by the vegetation but stillvery impressive I could see the huge trunk of thelargest Silk Cotton Tree (Ceiba pent<strong>and</strong>ra) in <strong>Trinidad</strong>.This tree is over 56 metres tall <strong>and</strong> has a circumferenceof 10.3 metres above the buttresses.For a full account of its measurement see the 2003issue of Living World. Everyone w<strong>and</strong>ered aroundthe base of the tree looking at the huge buttressroots <strong>and</strong> trying to peer between the branches ofthe smaller surrounding trees to see the top. <strong>The</strong>sides of the tree reminded me more of a cliff facerather than a living organism <strong>and</strong> the lianas hangingdown certainly tempted me to climb up for a betterlook. However, common sense <strong>and</strong> being wet <strong>and</strong>muddy put a halt to any tree climbing plans.After people had taken photos <strong>and</strong> admired thegiant tree we set off again. Paul Christopher sighteda male White-shouldered Tanager (Tachyphonus luctuosusflaviventris) flying through the forest, whilstlower down Bonnie Tyler found a beautiful spidercrawling across the leaf litter. I took some photos<strong>and</strong> later identified it as a male <strong>Trinidad</strong> Dwarf Tarantula(Cyriocosmus elegans). With silvery legs <strong>and</strong>orange colouring on its cephalothorax <strong>and</strong> part ofits abdomen it is probably the most striking(Continued on page 16)

Page 15 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011Below leftTricky stream Crossing(Dan Jaggernauth assisting)Photo: Mike Rutherford(above) left to right - Paula Smith, Bonnie Tyler,<strong>and</strong> Mike RutherfordCradled in the huge buttress rootsat the base of the largest Silk Cotton Tree(Ceiba pent<strong>and</strong>ra) in <strong>Trinidad</strong>.Photo: Eddison BaptisteRightDos Cocorite or liana snake(Pseustes poecilonotus polylepis)pretending to be a piece of vegetation.Photo: Mike Rutherford

Page 16 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011<strong>Moruga</strong> <strong>Bouffe</strong> Mike G. Rutherford(Continued from page 14)tarantula I’ve ever seen. Not much further alongAmy Deacon found a striped tree snail (Drymaeusbroadwayi) nestled amongst the spines on a pricklypalm trunk.Throughout the day many orchids were discoveredattached to trees, on rotting logs <strong>and</strong> on theground. Bede Rajahram listed the various species hefound including the epiphytic Ionopsis utricularioides,the white Maxillaria camaridii <strong>and</strong> the pink Epidendrumstenopetalum.<strong>The</strong> first sign we were getting near to our seconddestination was the sight of a small pile of mud inthe forest, people were stopping to look <strong>and</strong> takepictures but Dan encouraged everyone to keepmoving as we were very near to the main event.<strong>The</strong> vegetation thinned out <strong>and</strong> soon everyone wasst<strong>and</strong>ing in a muddy clearing with the hot middaysun beating down on us. Another, rather out ofplace, metal Forestry Division sign welcomed us―Outst<strong>and</strong>ing Features – Mud cones <strong>and</strong> flows aretypical of the impressive mud volcanoes on the site.You will hear it before you see it.‖ Again the signwas peppered with bullet holes.<strong>The</strong>re was a second sighting of a Common Galap,this time an adult, hiding in the vegetation just nextto the mud flats. Scattered over the mud I foundseveral empty shells from two of <strong>Trinidad</strong>’s commonestl<strong>and</strong> snails, the long, pointy, stripedPlekocheilus glaber <strong>and</strong> the brown, coiled Cyclohidalgoatranslucidum trinitense. <strong>The</strong> mud had also providedus with signs of other animals passing throughwith footprints all over the bouffe. Some were easyto identify, with an iguana leaving an unmistakablelarge, scaly, reptilian footprint <strong>and</strong> a brocket deerleaving a line of cloven hoof prints but there were afew other mammal prints that had us all guessing -racoon, tyra or just a dog?Reg Potter gave a talk about the volcanoes, which Irecorded with my camera. Here is a partial transcriptas the wind kept muffling the microphone.―Mud volcanoes are normally formed on geologicalanticlines. That’s when the sediment folded up <strong>and</strong>over (gesturing with his h<strong>and</strong>s). It’s also quite interestingthat oil accumulates in anticlines as well butyou don’t always find oil where mud volcanoes arebecause mud volcanoes let the liquid in the earthescape <strong>and</strong> get squeezed out <strong>and</strong> there they arelying all round the place. Sometimes you get tracesof oil <strong>and</strong> frequently the bubbles you see are methanegas <strong>and</strong> if you try <strong>and</strong> light it with a match you’llsee it burst into flames as the bubble pops. Andthat’s a sure sign of hydrocarbons... It’s usually alsoon a fault along the anticline or crossing the anticline,whatever it takes to provide an escape routefor liquid under pressure <strong>and</strong> this pressure is causedby tectonic forces <strong>and</strong> it squeezes up <strong>and</strong> flows outat the surface.‖ At this point Dan pointed out thatthe cone Reg was st<strong>and</strong>ing on had bubbled up at theexact moment he had said the word pressure, Regnoted what dangers he put himself under just to giveus all a lecture. Dan then wondered if Reg was relatedto Manning’s Prophetess due to his ability topredict the bubbling, Richard Peterson wasconvinced there was a link. Anyway I digress, Regcontinued his talk, ―This is the biggest area of anymud volcano except maybe Piparo... there are somesuch as Erin that have pools that you can get into<strong>and</strong> bathe <strong>and</strong> because the mud is of a higherdensity than water you tend to float rather high init.‖After the talk people spread out to find somewhereto eat their lunches, some found shady spots on theedge of the mud whilst others just collapsed wherethey stood. Once we had all eaten we started thewalk back to the cars. Initially we headed back theway we had come but eventually we took a differentroute allowing us to see more of the forest.<strong>The</strong> forest floor at one point was covered in largeflat seeds from a Bloodwood tree; I took someseeds with me back to UWI where WinstonJohnson from the Herbarium identified them as beingfrom Pterocarpus rohrii. <strong>The</strong>re were also manycalabash trees around with their large distinctivefruits <strong>and</strong> lots of seedling Mora trees. Further aheada second juvenile Mapepire Balsain was found <strong>and</strong>again moved to a safe distance away from the path.(Continued on page 17)

Page 17 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011<strong>Moruga</strong> <strong>Bouffe</strong> Mike G. Rutherford(Continued from page 16)On the route back we encountered a rather trickyobstacle as we had to get across a wide stream withsteep, muddy banks at either side. Dan stood in themiddle <strong>and</strong> helped many to wade across, some ofthe more limber decided to walk along a narrowfallen log <strong>and</strong> then swing to the far bank on a treebranch.We were all waiting around on the bank for everyoneto cross when someone called out ―snake!‖again. I moved towards the call wondering wherethe reptile was but didn’t see anything; it was onlywhen someone said it was right in front of me that Inoticed the cryptic critter. On the side of a tree,which I had already walked past, there was a DosCocorite or liana snake (Pseustes poecilonotus polylepis)pretending to be a piece of vegetation. Its bodywas kinked <strong>and</strong> bent just like a vine <strong>and</strong> it was onlywhen I traced the body to the end <strong>and</strong> found thehead did I realise what it was. <strong>The</strong> snake stayed frozenwhilst people came for a closer look. I was curiousto see how far its deception would go so onceeveryone had taken their photos <strong>and</strong> moved on Itouched the snake on the tail <strong>and</strong> to my surprise itdid nothing but sway slightly as though the vine itwas pretending to be had been caught in a breeze.Not much further on we came out of the forest intoan empty hunters camp <strong>and</strong> had a quick rest in theshade, poking around under the discarded sheets ofcorrugated iron that lay scattered around the sitewe found a fairly large Tailless Whip Scorpion(Heterophrynus sp.). A very long legged arachnid withlarge spiked pedipalps, they look rather scary butare actually harmless (to humans at least).It was only a short walk now along an old road pasta few more empty camps where we saw a Crapaudor Cane Toad (Rhinella marina) in a hole <strong>and</strong> aStriped Gecko (Gonatodes vittatus) on a post. <strong>The</strong>last animal encounter for me was a pleasant surprise,Amy Deacon <strong>and</strong> Aidan Farrell had foundsomething on the road so cheekily called for me tocome quick. I dashed over expecting to see somethingfast disappearing into the bush but instead wasgreeted with a very slow moving snail crossing theroad, it was a live Plekocheilus glaber <strong>and</strong> it was greatto be able to see what the snail itself looked likerather than just an empty shell.All the walkers were back at the cars <strong>and</strong> accountedfor by 2:30pm. After everyone had said theirgoodbye’s two car loads of walkers decided to addin a quick visit to another mud attraction. RegPotter led the way on a short drive to the Lagoon<strong>Bouffe</strong>, a mud volcano that had taken the shape of alake of mud rather than a cone. On the drive severalmore animals were added to the list of sightings forthe day – two Tegu lizards (Tupinambis teguixin), oneGiant Ameiva lizard (Ameiva ameiva) <strong>and</strong> a ChannelbilledToucan (Ramphastos vitellinus).Thankfully it was only a short walk to Lagoon <strong>Bouffe</strong>along a slippy path through thick forest. On the wayStevl<strong>and</strong> spotted a skink (Mabuya sp.) but was unableto catch it for a closer look. After five minutes theforest opened up <strong>and</strong> we were greeted with thesight of a large expanse of liquid mud stretchingabout 100 metres across. We stood on the edge<strong>and</strong> watched several birds flying around includingsome plovers, but as the group had all neglected tobring binoculars we could not identify them any further.<strong>The</strong>re were several places where you couldsee the bubbles coming up but it looked a bittreacherous to head out any further to investigate.Around the edge of the lake there were the remainsof many snake millipedes <strong>and</strong> flat backed millipedes,seemingly they had become stuck in the mud <strong>and</strong>perished.We headed back to the cars <strong>and</strong> started the longdrive home. Overall this trip was a great day out<strong>and</strong> allowed club members <strong>and</strong> visitors to see someof <strong>Trinidad</strong>’s biggest mud volcanoes, its tallest tree<strong>and</strong> some of its most interesting wildlife. Of particularnote was the range of reptiles <strong>and</strong> amphibiansthat were encountered, I sincerely hope that thenewly formed TTFNC Herpetology Group have asmuch luck in their future trips.

Page 18 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011Book NoticeChristopher K. StarrUniversity of the West Indiesckstarr@gmail.comDeVerteuil, L.A.A. 1858. <strong>Trinidad</strong>: Its Geography, naturalResources, Administration, Present Condition, <strong>and</strong> Prospects.London: Ward & Lock 508 pp. Free downloadat the Open Library, http://openlibrary.org/books/OL14046198M/ .This substantial book covers a broad range of topics,with two substantial chapters on plants <strong>and</strong> animals.Others that may be of interest to readers of thesepages are on climate, topography, <strong>and</strong> timber <strong>and</strong>other natural resources.<strong>The</strong> emphasis is very much on utility, <strong>and</strong> the plantsare treated almost entirely in terms of economicvalue. Not surprisingly, much of the treatment of l<strong>and</strong>vertebrates has to do with those that are hunted.This gives rise to some eye-catching statements. Forexample, the agouti is characterized as "Very common,well known, <strong>and</strong> easily domesticated." (p116)Similarly, "<strong>The</strong> Deer is very common in all parts of theisl<strong>and</strong>, but particularly in the neighbourhood of plantations...." (p118). And the opossum (manicou) isabundant as well.I have no doubt that he was right about the commonnessof these three native species at that time, but it isobviously not true today. In 20 years of <strong>Trinidad</strong>, Ihave never seen a wild brocket deer <strong>and</strong> seldom eitherof the other two. <strong>The</strong> reason for this change isnot obscure. <strong>The</strong>y have been hunted to a fraction oftheir former numbers. Apologists for the huntersblame habitat destruction for the decline, but this ispurest hypocrisy, as suitable habitat is still very extensivein <strong>Trinidad</strong>.DeVerteuil suggested that two species of peccarieswere present here, <strong>and</strong> his characterizations certainlymatch the white-collared <strong>and</strong> white-lipped peccaries,Pecari tajacu <strong>and</strong> Tayassu pecari, respectively. <strong>The</strong> formeris our familiar -- i.e. in the zoo; I have never seenit alive in the wild, for the usual reason -- quenk.<strong>The</strong>re seems no good evidence of the other in <strong>Trinidad</strong>during historical times.Three of his notes on insects deserve mention. Hecomments (p132) that the large larva of the palmweevil, Rhynchophorus palmarum, known as groo-grooworm is "much esteemed by our gourmets." Thisaccords well with a comment by the Canadian naturalistLéon Provancher, who visited <strong>Trinidad</strong> later inthe century. Provancher's informants emphasizedthat the groo-groo worm was not food for the poor,as it fetched a high price from English gourmets. It iscurious that the habit of eating this insect seems tohave disappeared entirely.On the next page, DeVerteuil notes that "Locusts visitthe shores at long intervals, <strong>and</strong> make ravages similarto those in other countries." Almost certainly he isreferring to Schistocerca gregaria, the migratory locustof Africa <strong>and</strong> the Mideast, swarms of which -- so I amtold -- have at times been blown clear across the Atlanticwith the Sahara dust. I wonder if this still occurson occasion or if changes in agriculture in Africahave altered the pattern.And he remarks (p136) on the swarming of termites<strong>and</strong> ants in great numbers after rain. <strong>The</strong> correlationbetween weather <strong>and</strong> the appearance of these "rainflies"was plain to DeVerteuil, but "How to accountfor this influence of rain? Really, I cannot discover anysatisfactory explanation: they are not forced out byinundations, since many live in houses; they do notcome forth in search of food, not even, I think, with aview to breeding." In fact, breeding <strong>and</strong> founding newcolonies is exactly what it is all about, <strong>and</strong> rain -- especiallyat the start of the rainy season -- providesgood conditions for this, so that the timing is by nomeans a mystery.I thank Adrian Hailey for bringing this book to my attention.

Page 19 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011WE GO TO GRENADA 1975Feature Serial by Hans Boos(Part 1b)As we rounded the light, fixed on a rock on thewestern tip of <strong>Trinidad</strong>, we saw the First Boca openout, giving us our first view of the Caribbean Seabeyond, <strong>and</strong> we felt the first billowing surge of theAtlantic rollers as they chased through this gap betweenmainl<strong>and</strong> <strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> the first isl<strong>and</strong> to thewest, Monos.<strong>The</strong> wind too, freshened, becoming a cool northeasterly,<strong>and</strong> prompted by this, the crew swiftlyloosened the ties on the sails with expert precision,<strong>and</strong> with a maximum of shouts <strong>and</strong> bawling back <strong>and</strong>forth between them <strong>and</strong> the captain, the canvas sailswere hauled up. Immediately "Starlight V" listed toport as the sails filled <strong>and</strong> boomed overhead <strong>and</strong> wefelt the headway increase. <strong>The</strong> bow rose over thefirst waves that were now increasing in size as theyswept past Point Rouge on the northwestern tip of<strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> the singers found it difficult to keeptheir feet or their beat in the now alive schooner.As we cleared <strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> headed northeast, on atack that would take us, distance wise, away fromGrenada, we ran into the cross-waves that werebeing reflected off the north coast, <strong>and</strong> travelling atright angles to the ones coming in out of the deepAtlantic. With each rise of the schooner there wasan added shudder as she traversed these crossingfurrows in the ever darkening sea.I had begun to feel queasy sitting in the stern, which,in addition to the up <strong>and</strong> down motion, the boat hada peculiar slewing motion from side to side. I amvery prone to motion sickness on boats <strong>and</strong> thoughI had not been affected during the long years of fishingin many small open pirogues with my father <strong>and</strong>his brothers, I had been very seasick on both crossingsof the Atlantic on my way to <strong>and</strong> from Engl<strong>and</strong>for my abortive attempt to become a veterinarian— a tale perhaps told elsewhere. Australia-boundtoo, I had terrible episodes of sickness which hadeither confined me to my bunk, deep in the bowelsof the immigration liner "Southern Cross," or survivingup on the foredeck, binoculars in h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong>the wind in my face. <strong>The</strong>re, both on the "Golfito"<strong>and</strong> the "Camito" — the ships of my Atlantic crossings— <strong>and</strong> on the "Southern Cross" I was able tospend as many hours as hunger <strong>and</strong> fatigue wouldallow, scanning the skies <strong>and</strong> surface of the oceanfor the unexpectedly rich mid-ocean bird life, ormarvelling at the ocean life below the bows orsweeping past. Sharks, dolphins, a whale or two, Ihad spotted, <strong>and</strong> flying fish spraying outward, fromthe curling bow-wave, gliding like large blue <strong>and</strong> silvermarine dragonflies, propelled onward by theirtails when they once more touched the wave-topsover which they were skimming; <strong>and</strong> giant sunfish,Mola mola, desperately, their dorsal <strong>and</strong> ventral finsflapping like mad, seeking to get out of the path, getsome depth between their slow cruising misshapenun-fish-like bodies <strong>and</strong> the oncoming steel juggernaut.I would have to make a mad dash up the swaying<strong>and</strong> heaving corridors from my cabin up to the freshair on the deck, where the motion forward with thesalty fresh air in my face, <strong>and</strong> deep in my lungs,dampened the rising gorge, <strong>and</strong> quelled the back-ofthethroat bitterness, signalling a bout of seasicknesswhich was aptly described by my father asfear in the first hour that you were going to die, <strong>and</strong>then, fear in the second that you were not.But I had survived such bouts <strong>and</strong> now I suggestedto Julius that we go forward to join the singers,where I felt I could better quell the rising uneasiness,<strong>and</strong> where we might have to spend the nightanyway, as there was little room where we wereensconced in the stern, so that we could watch overour goods.As we made our way forward between stacks offreight, large biscuit tins, cartons of packaged goods,lashed down propane <strong>and</strong> oxygen cylinders, bales ofP.V.C. plastic pipes, the singing up ahead faltered <strong>and</strong>petered out to a silence. We would have the bow(Continued on page 20)

Page 20 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011WE GO TO GRENADA 1975 Hans Boos(Continued from page 19)to ourselves, sharing it with the occasionally complaininggoats.I felt better immediately as we found a place on theforward hatch cover, <strong>and</strong> as the sky darkened intonight we forged into the increasing sea <strong>and</strong> wind.<strong>The</strong>n I was torn with indecision <strong>and</strong> doubt thatthough we had quit what little space we had in thestern, because of my very real fear of impending seasickness, we might have exchanged it for a night ofbeing soaked by the spray that was now being blownby the wind over the heaving bow.I looked wryly at Julius <strong>and</strong> he shrugged his shoulders,saying, "We may have to spend the night withthe goats in the lee of the bow."<strong>The</strong> thought of actually doing this was not in myimagination, for the smell of these animals, as well astheir copious pelletized droppings around themwhere they were tethered, would deter even themost crazed soul. We sat as far back as possible toescape the spray <strong>and</strong> settled as best we couldamongst the boxes <strong>and</strong> bales. <strong>The</strong> "Starlight V"heeled over, as gusts of wind seemed to grip her<strong>and</strong> push her violently forward, angled against theoncoming forces. <strong>The</strong> sail above us would slackenfor a second <strong>and</strong> then with a great cracking"thwack" would refill, shaking down spray that hadaccumulated on the canvas. We were getting wetanyway. Becoming colder <strong>and</strong> more cramped by theminute, <strong>and</strong> it was only about half past nine. <strong>The</strong>trip to Grenada would take all night. We were expectingto sail into St Georges Harbour at dawn. Itwas going to be a long night. Grim at this prospect,<strong>and</strong> questioning our decision to travel by schooner,we tried to make the best of it. <strong>The</strong>n, to make mattersworse, it suddenly began to rain. Silver curtainsof water were added to the spray from each wave."See if there is a place to keep dry," I asked Julius,who struggled aft. He came back to tell me that itwas drier in the stern <strong>and</strong> there was a small spacebehind the cook house where there seemed to be alittle shelter for our bags. Fearing the worst <strong>and</strong>resigned to what I knew would happen if I went aft, Inevertheless had no choice. So with rising gorge Imade my way sternward, passing people already inthe throes of their misery. Seated between twostacks of square Crix biscuit tins, where he hadwedged himself, sat Michael St John. His normallyhealthy shiny black face looked gray in the dim lightof the tossing light bulbs that lit this passageway."You alright, St John?" I managed to ask. His eyeswere stark as he could only gasp out, "Oh Gord, MrBoos," before he pitched forward, <strong>and</strong> I barely gotout of the way as he added the contents of hisstomach to the swill — a mixture of sea, rain, <strong>and</strong>untold ejecta — that, I noted, was now flowingdown the passageway, <strong>and</strong> out the scuppers. Ibarely made it to the side <strong>and</strong> added mine to thegreenly passing ocean. It had started. I passedthrough the area where the traffickers still slept ontop of the engine hatch, Terry was there, a smile onhis face, unaffected. I made it to the back of thecook house, <strong>and</strong> barely had time to pull the packsaway <strong>and</strong> lean over the gunwale. Those who havebeen sea-sick will underst<strong>and</strong> what I was goingthrough. For those who have not, no descriptionwill suffice.I lay on top of the jumble of pots <strong>and</strong> pans, <strong>and</strong> hungmy head over the stern. Here at least I was dry, butany effort to open my eyes which let in the view ofthe field of the waves <strong>and</strong> the tossing horizon — forthe delineation between the starry sky <strong>and</strong> the darksea was clearly visible — I was wracked with a freshseries of spasms that had long since emptied me ofany <strong>and</strong> all food I had eaten earlier, until my beard<strong>and</strong> moustache were encrusted, <strong>and</strong> I no longer hadany desire or will to wipe them clean.In between episodes, I managed to reach my packages<strong>and</strong> unroll a pallet of vinyl-covered foamrubber<strong>and</strong> lay it over the pots <strong>and</strong> pans. On this Ilay, <strong>and</strong> it was only a short roll over to once morehang my head over the stern. <strong>The</strong>re I lay in what Iremember as the most abject misery <strong>and</strong> desperationin my life. I was pressed up against the twocold propane gas cylinders boring into my lowerback <strong>and</strong> the pots <strong>and</strong> pans below me were nosofter than a jumble of sharp, quarried, bucket-sizedrocks.(Continued on page 21)

Page 21 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011WE GO TO GRENADA 1975 Hans Boos(Continued from page 20)It must have been about midnight, <strong>and</strong> I had stoppedcounting the times I had rolled to the rail, at adozen. <strong>The</strong> mainsail above me quivered <strong>and</strong>snapped <strong>and</strong> with each snap a small shower of dropsof water fell to dampen me anyway. I looked up atthe stretched canvas <strong>and</strong> saw the boom cross thesky, <strong>and</strong> the "Starlight V" stood upright for a secondor two, the masts swinging in a wide arc. <strong>The</strong> captainhad swung the helm over, changing course nowto the northwest, to make the run into Grenada.Now the diesel kicked in, adding its roar, <strong>and</strong> theschooner once more heeled over to port, the sailsclose hauled, the boom almost directly over thecenter of the stern, <strong>and</strong> the raindrops now becamea steady drip on the place where I lay.But I did not care anymore. I was prepared to die.Being wet did not matter. By keeping my eyesclosed I could suppress the urge to heave. But I wasso uncomfortable, in pain even, that every now <strong>and</strong>again I would be forced to change my position, toopen my eyes, <strong>and</strong> I would be forced to try to consignto the ocean, what I no longer had to give. Unbelievably,I must have slept, out of pure exhaustion.At one point I decided that, rather than endure anymore, I would jump overboard <strong>and</strong> swim to Grenada.In my delirium this was eminently reasonable.A full bladder impelled me to the bog-house on theport stern. Groping my way there, I met Julius comingout. He was ashen in the darkness. He admittedthat, in there, in the enclosed space, he, for thefirst time in his life, had succumbed too. I came out<strong>and</strong> looked into the engine-hatch area. <strong>The</strong>re wasTerry. I had forgotten him in my misery. <strong>The</strong>re hewas, holding a large basin, while the traffickers vomitedinto it. Terry of the iron stomach was unmovedby this. He moved on with the basin to anothermoaning woman. A rope crossed the spacelike a clothes line, from which hung a young man, byone h<strong>and</strong>. He swayed with the movement of theship, hanging onto the rope, his eyes closed, hisother h<strong>and</strong> clapped to the side of his head, a smallred transistor radio trapped there. He spent therest of the trip there, oscillating <strong>and</strong> lurching toevery heave <strong>and</strong> dip of the afterdeck beneath hiswide-planted feet.Making his way around this man on the clothes line,Terry emptied the basin over the side, only to returnto the frantic gesturing of another stricken trafficker,holding her palm clamped to her bulgingmouth. I barely made it to my pallet on top of thepots <strong>and</strong> pans, but I had no more to give to thepassing ocean but sour driblets of bitter bile. Sometimein the pre-dawn hours, I was aware of Juliuslying nearby with his head resting on my legs, as Imust have slept fitfully. A change in the frantic diesel-<strong>and</strong> sail-powered rushing through the waves <strong>and</strong>starred darkness woke me, <strong>and</strong> looking out over thestern gunwale I saw the sea was smooth <strong>and</strong> itstretched away in a lead-gray plain, tinged with thepinks of dawn. Above the "clunk-clunk" of the diesel,I could hear, coming plainly over the still water<strong>and</strong> quiet of the morning, the high-pitched whistlings<strong>and</strong> two-tiered pipings of the frogs on mainl<strong>and</strong>Grenada.I pushed myself upright <strong>and</strong>, looking ahead, saw thatwe were entering St George's harbour, Point Salinepassing on our starboard, <strong>and</strong> the multi-colouredstacks of the buildings <strong>and</strong> houses of St George's,which circled the harbour, <strong>and</strong> climbed away up thesurrounding hills that ringed the city. Julius stirredtoo, <strong>and</strong> listening intently, said, "Hear the frogs." Icertainly heard them. It was incredible that so tiny acreature — not more than 1 cm from nose to hindend — could put out such a sound that could carrythe half mile or so to where we were slowly motoringin. Elutherodactylus johnstonei, a tiny, highlysuccessful colonizer of many other Caribbean Isl<strong>and</strong>s<strong>and</strong> mainl<strong>and</strong> South America as well — I laterheard them, or a related species, in the leafy atriumof an hotel in downtown Maracaibo in Venezuela —had kept me awake with their incredibly loud chorusoutside my windows as I vacationed in Barbadosduring my teenage years. <strong>The</strong>y were everywhere inGrenada <strong>and</strong> continued their calling even during theday in areas where it was shaded, or where theweather grew dark with rain.Washing the crust of my night's ordeal from myface, I felt like a zombie, an appearance confirmed by(Continued on page 22)

Page 22 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011WE GO TO GRENADA 1975 Hans Boos(Continued from page 21)Julius <strong>and</strong> Terry when I joined them up on the bow.St John, too, looked much the worse for wear as Ienquired how he had spent the night, <strong>and</strong> even thepair of capuchin monkeys were subdued, sitting likelittle, hairy, pitiful dwarfs in their cages. <strong>The</strong>y toomust have had a terrifying night in an alien surrounding,filled with strange sounds, smells <strong>and</strong> movement.We tied up at the dock not long after <strong>and</strong> the passengers,including us, swarmed ashore, <strong>and</strong> the bustlewe had seen in <strong>Trinidad</strong> was repeated in reverse,as the "Starlight V" was relieved of her burden. Wesought out the Immigration <strong>and</strong> Customs officers,<strong>and</strong> presenting our documents explained to themour mission. That we were bringing animals to bolsterthe badly depleted ones in the Grenada Zoo,bought us some more than usual assistance, <strong>and</strong> thenatural curiosity to see animals, especially monkeys,gave us the slight advantage of clearing through thedock-side red tape that would normally apply tosuch oddly out-of-place passengers on an interisl<strong>and</strong>schooner.<strong>The</strong> zoo was within walking distance, <strong>and</strong> we shoulderedour packs <strong>and</strong> between us, we began to carrythe monkeys to their new home. From among thecrowd waiting on the dock-side, sorting out the baggagecoming ashore, <strong>and</strong> greeting returning relatives<strong>and</strong> envoys of the religious group, shouts of "Doondan,Doon-dan" rang out. St John broke away fromus <strong>and</strong> ran towards the two or three young menwho greeted him with elaborate h<strong>and</strong> shaking <strong>and</strong>back patting, <strong>and</strong> with repeated greetings all interspersedwith the ecstatic "Doon-dan."St John brought the three men over to us, saying, asintroductions were done, that I was his "Bossman,"<strong>and</strong> a jumbled, tumbling-out of details of what wehad come to do, poured from him. In the broadGrenadian accents of their animated exchange whichwe tried our best to underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> reply to, theonly concrete facts that we were able to glean werethat "Doon-dan" was St John's Grenadian "petname," that one of the other men's name was "Dr.Bones," <strong>and</strong> that they were eager to assist us in locatingany monkeys <strong>and</strong> catching any snakes thatmight exist on Grenada."Doon-dan", which St John had become as his feetmet his native soil, <strong>and</strong> by which name we referredto him during our brief contacts for the remainderof our expedition, suggested that he go off with hisfriends to make arrangements <strong>and</strong> contacts up in thenorth of the isl<strong>and</strong>. A two-pronged attack wouldbenefit the expedition much better than if we allstuck together to enquire <strong>and</strong> search in the sameareas.It seemed the best course of action, <strong>and</strong> in anyevent, Doon-dan had become a Grenadian the momenthe l<strong>and</strong>ed. We were strangers. He wouldassist us as a local of the isl<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> could do thatbetter in the company of his friends who were assuringus that everything had been arranged <strong>and</strong>prepared for our arrival <strong>and</strong> stay, up in the town ofSauteurs in the north of the isl<strong>and</strong>. Doon-dan hadobviously communicated with his friends prior to hiscoming, <strong>and</strong> they had greeted him like a returninghero. So we told him to get on with it, <strong>and</strong> I gavehim an advance in cash to cover any contingencieshe might meet. He jumped into the battered bluejitney with his friends <strong>and</strong> in a smoky, muffler-lessroar, they disappeared along the curving harbourroad.We looked after the departing jitney, glad in a wayto be rid of the man who had been transformedfrom the St John we knew into the Doon-dan wedid not. We trudged into the zoo, <strong>and</strong> finding thesuperintendent, we turned over our charges to him.<strong>The</strong> veterinarian would be in later, so, ensuring thatthe monkeys had access to water <strong>and</strong> some fruit<strong>and</strong> greens from a nearby hibiscus hedge, we set offto rent a car, <strong>and</strong> get something into our stomachs.At least Julius' <strong>and</strong> mine. Terry was fine, none theworse for wear from the voyage. We found coffee<strong>and</strong> snacks at a nearby shop <strong>and</strong> never did warmcoffee taste better as it went down. I could feel thecolour come back to my face <strong>and</strong> the ringing in myears go away as it untangled itself from the incessantcreaking of the frogs that was now everywherearound us.(to be continued )

Page 23 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 2/2011Management NoticesNew members; Volunteers; PublicationsManagement NoticesNew Members<strong>The</strong> <strong>Club</strong> warmly welcomes the following new members:Ordinary member:Fiona Cooper, Nikoki Forbes, Timothy MaynardNew life members:Kris Sookdeo, Richard FarrellNow life members:Jalaludin Khan, Martyn Kenefick, Shane T. BallahNew Website<strong>The</strong> <strong>Club</strong> has transferred to a new domain name <strong>and</strong> email address. <strong>The</strong> change allows us more space<strong>and</strong> greater control to reach out to the public <strong>and</strong> stay in touch with members.Website: www.ttfnc.orgEmail: admin@ttfnc.orghttp://www.facebook.com/pages/<strong>Trinidad</strong>-<strong>Tobago</strong>-<strong>Field</strong>-Naturalists-<strong>Club</strong>/68651412196?v=infoPUBLICATIONS<strong>The</strong> following <strong>Club</strong> publications are available to members <strong>and</strong> non-members:<strong>The</strong> TTFNCTrail GuideMembers =TT$200.00<strong>The</strong> NativeTrees of T&T2nd EditionMembers =TT$100.00Living worldJournal 1892-1896 CDMembers =TT$175.00Living World Journal 2008Living World Journal back issuesMembers price = freeMISCELLANEOUS<strong>The</strong> Greenhall TrustStarted in 2005, in memory of Elizabeth <strong>and</strong> Arthur Greenhall, dedicated artist <strong>and</strong> zoologist respectively,the Trust offers financial assistance to aspiring artists <strong>and</strong> biologists (in areas of flora <strong>and</strong> fauna) in <strong>Trinidad</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong>. Full details are available on their website: http://www.greenhallstrust-wi.org/link.htmYour 2011 Annual Membership Fees are Due:Please view bottom right of the mailing label to check if your subscripition has been paid.

<strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong> <strong>Field</strong> Naturalists’ <strong>Club</strong>P.O. Box 642, Port of Spain, <strong>Trinidad</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong>NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORSGuidelines for Articles <strong>and</strong> <strong>Field</strong> trip reports:Contributors <strong>and</strong> authors are asked to take note of the following guidelines when submittingarticles for inclusion in the newsletter1. Articles must be well written (structure/style), <strong>and</strong> be interesting <strong>and</strong> fun to read.3. Articles must have a sound scientific base.4. Articles submitted must be finished works. Please no drafts.5. Articles should generally not exceed 3000 words. Longer articles, if interestingenough, will be broken up <strong>and</strong> published as separate parts.6. Articles should be submitted as a text file, word or text in an e -mail.7. <strong>Field</strong> trip reports may include a separate table listing the scientific names, commonnames <strong>and</strong> families of plants <strong>and</strong> animals identified within the body of the report.8. Photographs can be in any of the following formats JPEG, BMP, PICT, TIFF, GIF. <strong>The</strong>ymust not be embedded into the word processing files. Information on the imagecontent including names of individuals shown must be provided.9. Acceptable formats for electronic submissions are doc <strong>and</strong> txt.10. All articles must reach the editor by the eight week of each quarter.Submission deadline for the 3rd Quarter 2011 issue is August 31st 2011.11. Electronic copies can be submitted to the ‘Editor’ at: admin@ttfnc.orgPlease include the code QB2011-3 in the email subject label.12. Hard copies along with CD softcopy can be delivered to the editor or any memberof Management.