New wilderness in the Netherlands - Agnes van den Berg

New wilderness in the Netherlands - Agnes van den Berg

New wilderness in the Netherlands - Agnes van den Berg

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 78 (2006) 362–372<strong>New</strong> <strong>wilderness</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands: An <strong>in</strong>vestigation of visualpreferences for nature development landscapes<strong>Agnes</strong> E. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong> a,∗ , Sander L. Koole ba Wagen<strong>in</strong>gen University and Research Centre, P.O. Box 47, 6700 AA, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlandsb Department of Social Psychology, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Van der Boechorststraat 1, 1081 BT, Amsterdam, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlandsReceived 27 July 2004; received <strong>in</strong> revised form 10 November 2005; accepted 23 November 2005Available onl<strong>in</strong>e 8 February 2006AbstractThe present research <strong>in</strong>vestigated visual preferences for nature development landscapes among 500 resi<strong>den</strong>ts from six plan areas <strong>in</strong> TheNe<strong>the</strong>rlands. Significant differences <strong>in</strong> relative preferences for wild versus managed scenes were found between landscape types and respon<strong>den</strong>tgroups. Development of wild nature was evaluated less positively <strong>in</strong> a forested area than <strong>in</strong> more open, rural areas. Among <strong>the</strong> background variables<strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> study, place of resi<strong>den</strong>ce, age, socio-economic status, farm<strong>in</strong>g background, preference for green political parties, and recreationalmotives were found to be systematically related to relative preferences for wild versus managed nature scenes, account<strong>in</strong>g for 16% of <strong>the</strong> variance<strong>in</strong> preference rat<strong>in</strong>gs. These f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are discussed with<strong>in</strong> an applied decision mak<strong>in</strong>g context <strong>in</strong> The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands.© 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.Keywords: Landscape preferences; Visual quality; Wilderness; Nature development; Socio-economic differences; Recreational motives1. Introduction“The wildness pleases. We seem to live alone with Nature.We view her <strong>in</strong> her <strong>in</strong>most recesses, and contemplate herwith more delight <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se orig<strong>in</strong>al wilds than <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> artificiallabyr<strong>in</strong>ths and feigned <strong>wilderness</strong>es of <strong>the</strong> palace” (A.A.Cooper, third Earl of Shaftesbury, The Moralists, 1709/1999)Anthony Ashley Cooper, third Earl of Shaftesbury(1671–1713), was one of <strong>the</strong> first modern th<strong>in</strong>kers who advocated<strong>the</strong> virtues of wild nature. In <strong>the</strong> three centuries thathave passed s<strong>in</strong>ce his pioneer<strong>in</strong>g work, <strong>the</strong> traditional notion of<strong>wilderness</strong> as an ugly and evil place has become slowly replacedby a new vision of <strong>wilderness</strong> as a unique and valuable type ofenvironment (Nash, 1967; Thacker, 1983). In <strong>the</strong> United States,this new vision of <strong>wilderness</strong> has ultimately resulted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> legalprotection of <strong>wilderness</strong> areas by <strong>the</strong> Wilderness Act of 1964and <strong>the</strong> creation of a National Wilderness Preservation System(NWPS). Likewise, o<strong>the</strong>r countries around <strong>the</strong> world have estab-∗ Correspond<strong>in</strong>g author. Tel.: +31 317 474393; fax: +31 317 424812.E-mail addresses: agnes.<strong>van</strong><strong>den</strong>berg@wur.nl (A.E. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>),sl.koole@psy.vu.nl (S.L. Koole).lished laws and strategies to protect <strong>the</strong> values of <strong>wilderness</strong> (cf.Jongman et al., 2004).In recent years, some countries have adopted more pro-activestrategies to safeguard <strong>the</strong> values of <strong>wilderness</strong> (SER, 2002).In The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands, for <strong>in</strong>stance, <strong>the</strong> Dutch authorities havedecided to establish a National Ecological Network that <strong>in</strong>volves<strong>the</strong> transformation of more than 50,000 ha of farmland <strong>in</strong>to newnatural areas (M<strong>in</strong>istry of Agriculture, Nature Management,and Fisheries, 1996). Some of <strong>the</strong>se former farmlands will beactively managed by regulative activities such as mow<strong>in</strong>g andclear-cutt<strong>in</strong>g. O<strong>the</strong>r former farmlands will be more passivelymanaged and left undisturbed to evolve <strong>in</strong>to “new <strong>wilderness</strong>”.Enhanc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> scenic quality of <strong>the</strong> landscape is one of <strong>the</strong> majoraims of this Dutch nature development policy. However, becausenature development practices are based on ecological pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesra<strong>the</strong>r than on lay people’s aes<strong>the</strong>tic preferences, it rema<strong>in</strong>s to beseen how far <strong>the</strong> newly developed natural areas will be appreciatedby <strong>the</strong> general public (Gobster, 1999; Parsons and Daniel,2002).The central aim of <strong>the</strong> present research was to ga<strong>in</strong> more<strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to people’s visual preferences for nature developmentlandscapes. In <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g paragraphs, we first discuss differentstrategies for nature development and <strong>the</strong>ir relation to <strong>the</strong>concept of <strong>wilderness</strong>. We <strong>the</strong>n review prior research on <strong>in</strong>di-0169-2046/$ – see front matter © 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.11.006

A.E. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, S.L. Koole / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 78 (2006) 362–372 363vidual differences <strong>in</strong> visual preferences for wild versus managednatural landscapes along with <strong>the</strong> potential rele<strong>van</strong>ce of place ofresi<strong>den</strong>ce, socio-economic variables, and recreational motivesto expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se differences. F<strong>in</strong>ally, we present <strong>the</strong> results of asurvey among 500 resi<strong>den</strong>ts from six nature development areas<strong>in</strong> The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands.1.1. Nature development and <strong>the</strong> concept of <strong>wilderness</strong>The Dutch nature development policy can be understood aspart of an <strong>in</strong>ternational movement that has set forth ecologicalrestoration as <strong>the</strong> new standard <strong>in</strong> nature management practice(Hobbs and Norton, 1996; Davis and Slobodk<strong>in</strong>, 2004). In general,ecological restoration may be def<strong>in</strong>ed as human <strong>in</strong>tervention<strong>in</strong>tended to recover nature’s <strong>in</strong>tegrity which is considered tobe threatened or even absent because of human activities suchas agriculture, <strong>in</strong>dustry, m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, and recreation (Swart et al.,2001). A dist<strong>in</strong>ctive characteristic of <strong>the</strong> Dutch plans for ecologicalrestoration is that <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terventions will be carried outma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> agricultural production areas, which will be transformed<strong>in</strong>to completely new natural areas. To achieve this,several k<strong>in</strong>ds of nature management strategies may be applied,rang<strong>in</strong>g from active strategies that guide natural processes bymeans of regulative activities, to more passive strategies thatencourage <strong>the</strong> development of spontaneous natural processes bym<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>g human activities <strong>in</strong> an area (cf. Hobbs and Harris,2001). Application of active nature management strategies promotes<strong>the</strong> development of orderly, managed natural landscapes,while application of more passive strategies promotes <strong>the</strong> developmentof wild, unmanaged natural landscapes. In The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands,<strong>the</strong>se latter landscapes are commonly referred to as “new<strong>wilderness</strong> areas”.The term “new <strong>wilderness</strong>” for humanly redeveloped landscapesmay sound like a contradiction. However, this contradictiononly arises when one def<strong>in</strong>es <strong>wilderness</strong> as prist<strong>in</strong>eareas which are completely untouched by humans. The latterdef<strong>in</strong>ition is often used <strong>in</strong> legal documents (cf. <strong>the</strong> AmericanWilderness Act, 1964). However, it is also possible to def<strong>in</strong>e<strong>wilderness</strong> from a more subjective, psychological perspective.Results of landscape perception studies <strong>in</strong>dicate that lay peopleuse <strong>the</strong> term <strong>wilderness</strong> to describe any natural area withoutdiscrim<strong>in</strong>able human <strong>in</strong>fluences (Wohlwill, 1983; Kaplanand Kaplan, 1989). Thus, <strong>the</strong> appearance of an environment,ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> actual amount of human <strong>in</strong>terference, determ<strong>in</strong>eswhe<strong>the</strong>r an <strong>in</strong>dividual perceives it as <strong>wilderness</strong> or not. On <strong>the</strong>basis of this psychological def<strong>in</strong>ition of <strong>wilderness</strong> it is possibleto refer to humanly redeveloped landscapes as <strong>wilderness</strong>landscapes.The planned nature development will drastically change <strong>the</strong>appearance of <strong>the</strong> Dutch countryside. Consequently, <strong>the</strong> scenicconsequences of nature development plans as <strong>the</strong>y are experiencedby those who live, work, and recreate <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> designatedareas constitute an important element <strong>in</strong> land management decisions.In recognition of this notion, Dutch nature developmentpolicy has <strong>in</strong>cluded enhancement of <strong>the</strong> landscape’s scenic qualityas a criterion for environmental plann<strong>in</strong>g and managementnext to ecological criteria such as <strong>in</strong>crease of biodiversity andnaturalness. By do<strong>in</strong>g so, <strong>the</strong> Dutch government has shownan awareness that public or scenic aes<strong>the</strong>tics should be dist<strong>in</strong>guishedfrom ecological values (cf. Gobster, 1999; Parsons andDaniel, 2002). However, details on how <strong>the</strong> scenic quality criterionrelates to <strong>the</strong> various restoration options have not beenspecified. It would <strong>the</strong>refore be useful to ga<strong>in</strong> more <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>tohow local people evaluate <strong>the</strong> scenic quality of different types ofnature development landscapes, <strong>in</strong> particular wild versus moremanaged landscapes.1.2. Visual preferencesWhen people are asked to categorize natural scenes, <strong>the</strong>y typicallyput wild, disorderly scenes toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> one pile, whereas<strong>the</strong>y put more managed and structured scenes toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>rpile (cf. Hartig and E<strong>van</strong>s, 1993). Degree of human <strong>in</strong>fluencethus represents a key dimension underly<strong>in</strong>g people’s landscapeperceptions. The evaluation of this dimension varies considerablybetween <strong>in</strong>dividuals. Indeed, sett<strong>in</strong>gs reflect<strong>in</strong>g ei<strong>the</strong>r lowor high degrees of human <strong>in</strong>fluence tend to elicit <strong>the</strong> most <strong>in</strong>dividualvariation <strong>in</strong> environmental preferences (Dear<strong>den</strong>, 1984;Gallagher, 1977; Orland, 1988; Strumse, 1996). Accord<strong>in</strong>gly,<strong>the</strong>re exist important <strong>in</strong>dividual differences <strong>in</strong> visual preferencesfor wild versus more managed natural sett<strong>in</strong>gs.Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) have reviewed <strong>the</strong> available evi<strong>den</strong>ceon <strong>in</strong>dividual differences <strong>in</strong> landscape preferences. Theiranalysis suggests that differences between members of varioussubcultures and ethnic groups can nearly always be <strong>in</strong>terpreted <strong>in</strong>terms of <strong>the</strong> preferred balance between natural and human <strong>in</strong>fluences.Some <strong>in</strong>dividuals tend to display a preference for wildnatural landscapes, whereas o<strong>the</strong>rs tend to display a preferencefor more managed nature. Unfortunately, <strong>the</strong> studies reviewedby Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) do not allow any firm conclusionsconcern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> cultural or ethnic variables that underlie <strong>the</strong>se differences,because <strong>the</strong> subcultures and groups that were studieddiffered on more than one dimension (e.g., urbanity, familiarity,age, race, <strong>in</strong>come). In <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g paragraphs, we consider <strong>the</strong>empirical evi<strong>den</strong>ce for three types of variables that are oftenmentioned as possible correlates of <strong>in</strong>dividual differences <strong>in</strong>preferences for wild versus managed natural landscapes: placeof resi<strong>den</strong>ce, socio-economic characteristics, and recreationalmotives.1.3. Place of resi<strong>den</strong>ceA first potential source of <strong>in</strong>dividual differences <strong>in</strong> preferencefor wild versus managed nature is place of resi<strong>den</strong>ce. Studiesamong rural resi<strong>den</strong>ts have sometimes reported negative evaluationsof plans to protect or develop nearby <strong>wilderness</strong> areas(e.g., Fiallo and Jacobsen, 1995; Durrant and Shumway, 2004).For example, results of a recent survey <strong>in</strong>dicated that resi<strong>den</strong>tsof six south-eastern Utah counties displayed negative attitudestoward <strong>the</strong> designation of <strong>wilderness</strong> study areas <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir county(Durrant and Shumway, 2004). Such negative attitudes havebeen attributed to perceived impacts on livelihoods or disagreementwith local plann<strong>in</strong>g procedures, which may give rise to a‘resistance to change’.

A.E. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, S.L. Koole / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 78 (2006) 362–372 365<strong>in</strong>dicative of a more generic <strong>in</strong>fluence of resi<strong>den</strong>ts’ familiaritywith <strong>the</strong> local, managed landscape (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989).Second, with respect to socio-economic characteristics, wepredicted that farmers, because of <strong>the</strong>ir extended experiencewith agricultural, managed landscapes and <strong>the</strong>ir depen<strong>den</strong>ce onnature for <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>come, would display relatively low preferencesfor wild nature development landscapes, and relatively high preferencesfor managed nature development landscapes. In a similarve<strong>in</strong>, we expected that elderly respon<strong>den</strong>ts and respon<strong>den</strong>ts witha low socio-economic status, because of <strong>the</strong>ir weaker position<strong>in</strong> life and greater vulnerability to <strong>the</strong> dangerous aspects of wildnature, would display relatively low preferences for wild as comparedto managed nature development landscapes. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore,we expected that environmentalists, because of <strong>the</strong>ir more ecocentricenvironmental beliefs (cf. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong> et al., <strong>in</strong> press),would display relatively high preferences for wild as comparedto managed nature development landscapes.Third and last, we predicted that preferences for wild versusmanaged nature development landscapes would be related torespon<strong>den</strong>ts’ recreational motives. Based on <strong>the</strong> notion that certa<strong>in</strong>,more <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic, motives are relatively important to <strong>wilderness</strong>users as compared to users of o<strong>the</strong>r natural sett<strong>in</strong>gs (Knopfet al., 1983; Johnson, 2002), we expected that respon<strong>den</strong>ts whovisited nature for reflection, recovery from stress, and naturestudy would display higher preferences for wild natural landscapesas compared to managed nature development landscapes.2. Method2.1. Data collection and respon<strong>den</strong>tsData were obta<strong>in</strong>ed via a mail survey among resi<strong>den</strong>ts fromsix different areas <strong>in</strong> The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands. A total of 1340 questionnaireswith full-color photographs (225 per area) were distributedwith a cover letter <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that only persons of16 years and older were to answer <strong>the</strong> questionnaire. In eacharea, addresses were selected us<strong>in</strong>g a random-selection procedurebased on postal codes. A total of 515 questionnaires werereturned, yield<strong>in</strong>g a response rate of 38%. This somewhat lowresponse rate was probably due to <strong>the</strong> length of <strong>the</strong> questionnaire(27 pages). Fifteen questionnaires were discarded because<strong>the</strong>y conta<strong>in</strong>ed miss<strong>in</strong>g data on more than two variables, leav<strong>in</strong>g500 respon<strong>den</strong>ts (360 males, 140 females) for <strong>the</strong> analysis. Themean age of <strong>the</strong> respon<strong>den</strong>ts was 49 years, and varied between16 and 84 years.Because <strong>the</strong> present research was not aimed at mak<strong>in</strong>g generalizedstatements about proportions of <strong>the</strong> Dutch populationthat prefer wild or managed nature development, we considered<strong>the</strong> somewhat low response rate acceptable. The primary focusof <strong>the</strong> present research was on ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> relationsbetween <strong>in</strong>dividual characteristics and landscape preferences.The most important requirement for study<strong>in</strong>g such relationsis that <strong>the</strong> sample shows enough variation on <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong>dividualcharacteristics, i.e., place of resi<strong>den</strong>ce, socio-economic characteristics,and recreational motives. Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary analyses <strong>in</strong>dicatedthat respon<strong>den</strong>ts were approximately evenly distributedacross <strong>the</strong> six selected areas, 80 ≤ ns ≤ 89. Moreover, our sample<strong>in</strong>cluded respon<strong>den</strong>ts from a wide range of socio-economicbackgrounds and with various recreational motives. Thus, <strong>the</strong>rewas sufficient variation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> present sample to conduct ouranalyses.2.2. Plan areasAt <strong>the</strong> time of <strong>the</strong> survey, all six plan areas had been designatedby <strong>the</strong> Dutch Government as nature development areas(cf. M<strong>in</strong>istry of Agriculture, Nature Management and Fisheries,1996). However, <strong>the</strong> areas differed with regard to physical geographiccircumstances, land use, surface area of planned naturedevelopment, and phase of <strong>the</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g procedure. In <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g,a brief description of <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> characteristics of eacharea at <strong>the</strong> time of survey will be provided.Area 1 (‘Ulvenhout-Galder’) was a sandy, agricultural areasituated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> prov<strong>in</strong>ce of North Brabant. The plans for naturedevelopment <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area focused on several brook valleys witha total surface area of about 800 ha. At <strong>the</strong> time of survey, severalplan alternatives had been formulated and made public. Apreferred alternative had not yet been selected.Area 2 (‘De Burd’) was a highly managed clay area <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>prov<strong>in</strong>ce of Friesland, surrounded by canals and lakes. The plansfor nature development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area focused on grassland <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>Nor<strong>the</strong>rn part of <strong>the</strong> area, which had a total surface area of about250 ha. At <strong>the</strong> time of survey, a preferred plan to develop a claymarsh had been selected and made public. Local reactions tothis plan had been predom<strong>in</strong>antly negative.Area 3 (‘Grensmaas’) was part of <strong>the</strong> valley of <strong>the</strong> river Maas<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> prov<strong>in</strong>ce of Limburg. The nature development plans for<strong>the</strong> specific area <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> survey covered about 250 ha.At <strong>the</strong> time of survey, a plan to develop riparian woodlands,floodpla<strong>in</strong>s, and marshes had been selected and made public.A specific feature of <strong>the</strong> plan was that it would be f<strong>in</strong>anced byprofits from gravel m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Local reactions to this plan had beenprimarily positive.Area 4 (‘Compagnonsbossen’) was a wooded area of about225 ha situated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> prov<strong>in</strong>ce of Friesland. The woods, whichhad orig<strong>in</strong>ally been planted for forestry purposes, were on oneside adjacent to a protected peat area. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r sides, <strong>the</strong>ywere surrounded by fields. The aim of <strong>the</strong> nature development<strong>in</strong> this area was to <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>the</strong> water level <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> woods to helpprevent dehydration of <strong>the</strong> adjacent peat area. Although severalplan alternatives had been formulated at <strong>the</strong> time of survey, <strong>the</strong>sehad not yet been made public.Area 5 (‘Bran<strong>den</strong>’) was a highly managed sandy area situated<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> prov<strong>in</strong>ce of Dren<strong>the</strong>. The plans for nature development<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area focused on a brook valley with a total surface areaof about 350 ha. The plann<strong>in</strong>g procedure <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area had not yetstarted at <strong>the</strong> time of survey. However, a possible land-use planfor this area had been developed. This plan <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>the</strong> developmentof marshes and <strong>the</strong> restoration of <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al w<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gof <strong>the</strong> brook.Area 6 (‘<strong>Berg</strong>en-Egmond-Schoorl’) was a coastal area withbulb fields and grassland situated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> prov<strong>in</strong>ce of North Holland.The plans for nature development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area focused onseveral polders with a total surface area of about 920 ha. At <strong>the</strong>

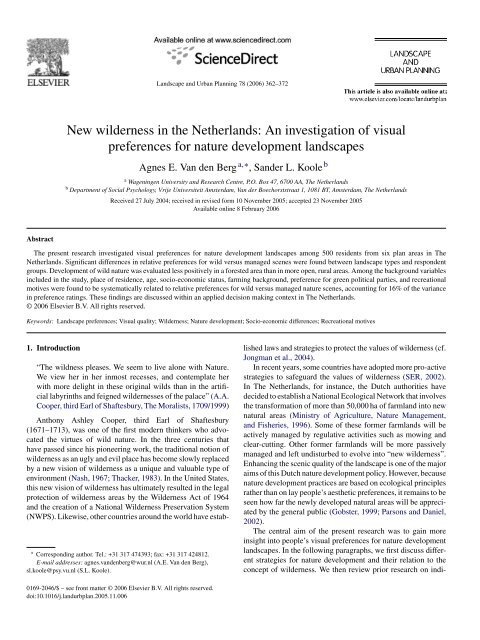

366 A.E. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, S.L. Koole / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 78 (2006) 362–372time of survey, several plan alternatives had been formulated andmade public. A preferred alternative had not yet been selected.2.3. StimuliThe stimulus set consisted of six pairs of full-color photographs(10 cm × 15 cm) of natural landscapes. The photographswere selected <strong>in</strong> consultation with local authorities(Fig. 1). One photograph of each pair depicted <strong>the</strong> landscape <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> area as it would look like after <strong>the</strong> realization of active naturemanagement strategies (i.e., landscapes classified as ‘sem<strong>in</strong>atural’or ‘multifunctional’ <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dutch handbook of targetnature types; Bal et al., 1996). The o<strong>the</strong>r photograph of eachpair depicted <strong>the</strong> landscape <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area as it would look like whenit would be left to evolve spontaneously, without active human<strong>in</strong>tervention (i.e., landscapes classified as ‘approximately natural’or ‘guided natural’ <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> handbook of target nature types).Because examples of <strong>the</strong> latter type of landscape were not available<strong>in</strong> The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands at <strong>the</strong> time of study, our contact persons<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> areas selected referent images from o<strong>the</strong>r countries, suchas Poland and Russia, to portray this type of landscape.In <strong>the</strong> questionnaire, <strong>the</strong> two types of nature developmentlandscapes were referred to as landscapes A and B. In <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduction,it was expla<strong>in</strong>ed that <strong>the</strong> landscapes <strong>in</strong>dicated with an Arepresented ‘actively’ managed sett<strong>in</strong>gs, while landscapes <strong>in</strong>dicatedwith a B represented ‘passively’ managed sett<strong>in</strong>gs. Theconcepts of active and passive management were expla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>a neutral manner, without emphasiz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> desirability of a particularstrategy (see Appendix A).2.4. Measures and questionnaireThe questionnaire began with a general <strong>in</strong>troduction, <strong>in</strong> whichrespon<strong>den</strong>ts were given a map depict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> locations of <strong>the</strong>six plan areas and some basic <strong>in</strong>formation on nature developmentand nature management strategies (see Appendix A). Therema<strong>in</strong>der of <strong>the</strong> questionnaire was divided <strong>in</strong>to three parts. Thefirst part started with questions about <strong>the</strong> 12 photographs ofnatural sett<strong>in</strong>gs. Pairs of photographs of actively and passivelymanaged landscapes were shown <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> upper halves of adjacentpages, with actively managed landscape on <strong>the</strong> left page,and <strong>the</strong> passively managed landscape on <strong>the</strong> right page. Rat<strong>in</strong>gscales were pr<strong>in</strong>ted directly underneath each photograph.Respon<strong>den</strong>ts were asked to rate each landscape on several characteristics,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g beauty and perceived <strong>wilderness</strong>.Perceived beauty was measured on a positively skewed, 6-po<strong>in</strong>t Likert scale with separate verbal labels for each scale po<strong>in</strong>t(1 = ‘not at all beautiful’; 2 = ‘not beautiful’; 3 = ‘somewhatbeautiful’; 4 = ‘beautiful’; 5 = ’very beautiful’; 6 = ‘extremelybeautiful’). We decided to use a positively skewed scale, becauseprevious research has shown that natural landscapes generallyelicit positive reactions and are rarely rated as ugly (cf. Ulrich,1993). Perceived <strong>wilderness</strong> was measured by ask<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> respon<strong>den</strong>tsto rate, on a 5-po<strong>in</strong>t Likert scale, <strong>the</strong> applicability of <strong>the</strong>description: ‘a wild landscape where nature can take its owncourse’. To avoid response bias, <strong>the</strong> question about perceived<strong>wilderness</strong> was embedded <strong>in</strong> a list of eight questions, seven ofwhich are irrele<strong>van</strong>t to <strong>the</strong> focus of <strong>the</strong> present <strong>in</strong>vestigation andwill not be fur<strong>the</strong>r discussed.The second part of <strong>the</strong> questionnaire consisted of generalquestions about nature and landscape, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g questions aboutrecreational motives. These motives were assessed by ask<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> respon<strong>den</strong>ts to rate <strong>the</strong> applicability of reasons for visit<strong>in</strong>gnatural areas on a 5-po<strong>in</strong>t scale. The first recreational motive,recovery from stress, was measured by <strong>the</strong> statement: “I visitnature to escape <strong>the</strong> stress of daily life and to put my worriesaside”. The second motive, reflection, was measured by <strong>the</strong> statement“I visit nature to th<strong>in</strong>k <strong>in</strong> peace about <strong>the</strong> th<strong>in</strong>gs that bo<strong>the</strong>rme”. The third motive, study<strong>in</strong>g nature, was measured by <strong>the</strong>statement “I visit nature to study special animals and plants”.These three statements about recreational motives were embeddedamong three o<strong>the</strong>r statements which are irrele<strong>van</strong>t to <strong>the</strong>focus of <strong>the</strong> present <strong>in</strong>vestigation and will not be fur<strong>the</strong>r discussed.The f<strong>in</strong>al part of <strong>the</strong> questionnaire assessed various backgroundcharacteristics, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g age, <strong>in</strong>come, education level,farm<strong>in</strong>g background, and environmentalism. Respon<strong>den</strong>ts who<strong>in</strong>dicated that <strong>the</strong>y, or <strong>the</strong>ir partner, worked, or had worked, oncattle and/or arable farms were classified as farmers. A measureof environmentalism was derived from respon<strong>den</strong>ts’ politicalpreference. Respon<strong>den</strong>t who <strong>in</strong>dicated that <strong>the</strong>y voted for a‘green’ political party (i.e., “Groen L<strong>in</strong>ks”) dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> last electionswere classified as environmentalists.2.5. Data analysisThe questionnaires of 40 respon<strong>den</strong>ts conta<strong>in</strong>ed one or twomiss<strong>in</strong>g values on rele<strong>van</strong>t variables. Because <strong>the</strong> questionnairewas quite extensive, we suspected that <strong>the</strong>se miss<strong>in</strong>g datareflected random omissions ra<strong>the</strong>r than systematic response patterns.Therefore, to avoid <strong>the</strong> omission of valid data, we decidedto impute <strong>the</strong> miss<strong>in</strong>g data for <strong>the</strong>se respon<strong>den</strong>ts <strong>in</strong>stead of delet<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong>ir data altoge<strong>the</strong>r. We replaced <strong>the</strong> miss<strong>in</strong>g values by <strong>the</strong>average values of <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r respon<strong>den</strong>ts. The same pattern ofresults was obta<strong>in</strong>ed when cases with miss<strong>in</strong>g data were deletedfrom <strong>the</strong> dataset (Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, 1999).We analyzed <strong>the</strong> data us<strong>in</strong>g analysis of variance (ANOVA)and regression analysis. These statistical techniques assume<strong>in</strong>terval data, while <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> depen<strong>den</strong>t variable, perceivedbeauty, was measured on an ord<strong>in</strong>al Likert scale. However,accord<strong>in</strong>g to prevail<strong>in</strong>g notions, Likert scales can be used with<strong>in</strong>terval procedures, provided <strong>the</strong> scale items have at least fiveand preferably seven categories. Perceived beauty had six categories,and thus fulfilled this requirement. Jaccard and Wan(1996) state that for many statistical tests, even ra<strong>the</strong>r severedepartures from <strong>in</strong>tervalness do not seem to affect Type I andType II errors dramatically. This is supported by o<strong>the</strong>r literature(B<strong>in</strong>der, 1984; Nunnally, 1978; Zumbo and Zimmerman, 1993).To prepare <strong>the</strong> data for regression analysis, we first computeddifference scores between beauty rat<strong>in</strong>gs for wild andmanaged landscapes, <strong>in</strong> such a way that higher scores representedhigher relative preferences for wild nature. Notably,<strong>the</strong> use of this s<strong>in</strong>gle preference <strong>in</strong>dex potentially results <strong>in</strong>a loss of <strong>in</strong>formation because it neglects cont<strong>in</strong>uous varia-

A.E. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, S.L. Koole / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 78 (2006) 362–372 367Fig. 1. Pairs of managed (left) and wild (right) natural sett<strong>in</strong>gs presented as nature development plans <strong>in</strong> six areas.

368 A.E. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, S.L. Koole / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 78 (2006) 362–372Table 1Mean rat<strong>in</strong>gs of <strong>wilderness</strong> (scale range 1–5) and beauty (scale range 1–6) formanaged and wild nature development landscapes <strong>in</strong> six areas (N = 500, standarddeviations <strong>in</strong> paren<strong>the</strong>ses)Area Perceived <strong>wilderness</strong> (1–5) Perceived beauty (1–6)Managed Wild Managed Wild1 2.05 (.83) 4.14 (.78) 3.87 (.76) 4.69 (.88)2 2.37 (.98) 3.75 (.94) 3.49 (1.01) 4.14 (1.00)3 2.63 (.88) 3.84 (.92) 3.88 (.79) 4.25 (1.09)4 2.73 (.95) 4.18 (.85) 4.25 (.89) 3.73 (1.15)5 3.00 (.91) 4.16 (.79) 4.32 (.84) 4.75 (.86)6 2.05 (.81) 4.01 (.85) 3.71 (.91) 4.29 (1.08)Total 2.48 (.56) 4.01 (.58) 3.92 (.55) 4.31 (.69)Note. See Fig. 1 for depictions of <strong>the</strong> landscapes; perceived <strong>wilderness</strong> was measuredby ask<strong>in</strong>g respon<strong>den</strong>ts to rate <strong>the</strong> applicability of <strong>the</strong> description: ‘a wildlandscape where nature can take its own course’. All means differ significantlybetween wild and cultivated landscapes at p < .001.tions <strong>in</strong> perceived <strong>wilderness</strong> of <strong>the</strong> landscapes. To exam<strong>in</strong>e<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluence of cont<strong>in</strong>uous variations <strong>in</strong> perceived <strong>wilderness</strong>on landscape preferences, we re-analyzed <strong>the</strong> data us<strong>in</strong>g multilevelanalysis (Bryk and Rau<strong>den</strong>bush, 1992; see Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>et al., 1998, for an application <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> doma<strong>in</strong> of nature evaluation).We formulated a basic two-level model, with <strong>in</strong>dividualbeauty rat<strong>in</strong>gs of <strong>the</strong> twelve landscapes as lower level observationsnested with<strong>in</strong> persons. Effects of perceived <strong>wilderness</strong>on beauty rat<strong>in</strong>gs, and socio-economic differences <strong>in</strong> relationsbetween <strong>wilderness</strong> and beauty, were estimated by add<strong>in</strong>g rat<strong>in</strong>gsof perceived <strong>wilderness</strong>, socio-economic variables, recreationalmotives, and <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>teraction terms to this model. Theresults of <strong>the</strong> multilevel analysis were highly similar to thoseproduced by <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>ear regression analysis with <strong>the</strong> preference<strong>in</strong>dex as a s<strong>in</strong>gle depen<strong>den</strong>t variable (see Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong> (1999,Chapter 5) for a more detailed description of <strong>the</strong> outcomesof <strong>the</strong> multilevel analysis). Because <strong>the</strong> regression approachis more conventional and easier to <strong>in</strong>terpret for most readersthan multilevel analysis, we rema<strong>in</strong>ed with this approach <strong>in</strong> thisarticle.3. Results3.1. Perceived <strong>wilderness</strong>To check whe<strong>the</strong>r our classification of <strong>the</strong> landscapes as‘wild’ versus ‘managed’ corresponded to respon<strong>den</strong>ts’ perceptions,we compared respon<strong>den</strong>ts’ average <strong>wilderness</strong> rat<strong>in</strong>gs ofwild landscapes to <strong>the</strong>ir average <strong>wilderness</strong> rat<strong>in</strong>gs of managedlandscapes. Rele<strong>van</strong>t means are displayed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> left half ofTable 1. Wild landscapes were generally perceived as wilderand more spontaneous <strong>in</strong> character than <strong>the</strong>ir managed counterparts,M = 4.01 versus M = 2.47, t(499) = 47.20, p < .001. Thisdifference <strong>in</strong> perceived <strong>wilderness</strong> was found for each pair oflandscapes, all p’s < .001. Thus, respon<strong>den</strong>ts’ perceptions of <strong>the</strong>landscapes as wild or managed corresponded with variations <strong>in</strong>nature management strategies between <strong>the</strong> landscapes.Table 2Mean beauty rat<strong>in</strong>gs (scale range 1–6) for managed and wild nature developmentlandscapes <strong>in</strong> six areas rated by resi<strong>den</strong>ts and nonresi<strong>den</strong>ts (standard deviations<strong>in</strong> paren<strong>the</strong>ses)Area Resi<strong>den</strong>ts Nonresi<strong>den</strong>tsManaged Wild Managed Wild1 4.00 a (.85) 4.84 b (.77) 3.85 a (.75) 4.66 b (.91)2 4.13 a (1.07) 4.11 a (1.26) 3.36 b (.95) 4.15 a (.95)3 3.80 a (.85) 4.28 b (1.17) 3.89 a (.78) 4.25 b (1.08)4 4.29 a (1.06) 3.73 b (1.23) 4.24 a (.86) 3.72 b (1.13)5 4.56 a (.83) 4.81 b (1.00) 4.29 c (.84) 4.75 a,b (.83)6 4.00 a (.95) 4.55 b (1.06) 3.65 c (.89) 4.23 d (1.08)Note. Means with unequal letters differ per row at p < .05.3.2. Perceived beautyRespon<strong>den</strong>ts generally perceived both <strong>the</strong> wild and managedlandscapes as beautiful. As can be seen <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> right halfof Table 1, mean beauty rat<strong>in</strong>gs of both types of landscapeswere well above <strong>the</strong> conceptual midpo<strong>in</strong>t of <strong>the</strong> scale, whichwas already positively skewed. The ANOVA also revealed asignificant effect of landscape type, which <strong>in</strong>dicated that wildlandscapes were generally perceived as more beautiful thanmanaged landscapes, M = 3.92 versus M = 4.31, t(499) = 9.92,p < .001. Higher beauty rat<strong>in</strong>gs for wild landscapes were foundfor five out of <strong>the</strong> six landscape pairs, all p’s < .001. Theonly exception to this pattern was obta<strong>in</strong>ed for <strong>the</strong> pair oflandscapes from Area 4 (a forested area). In Area 4, <strong>the</strong>wild landscape was rated significantly less beautiful than <strong>the</strong>managed landscape, M = 3.73 versus M = 4.25, t(499) = 7.88,p < .001.3.3. Resi<strong>den</strong>ts versus nonresi<strong>den</strong>tsTable 2 provides an overview of mean beauty rat<strong>in</strong>gs by resi<strong>den</strong>tsand nonresi<strong>den</strong>ts. In Areas 2, 5 and 6, resi<strong>den</strong>ts rated <strong>the</strong>managed plan for <strong>the</strong>ir own area as significantly more beautifulthan nonresi<strong>den</strong>ts, all p’s < .01. In addition, resi<strong>den</strong>ts of Area6 also rated <strong>the</strong> wild landscape <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own area significantlymore beautiful than nonresi<strong>den</strong>ts, p < .05.The strongest differences <strong>in</strong> landscape preferences betweenresi<strong>den</strong>ts and nonresi<strong>den</strong>ts were found <strong>in</strong> Area 2. As can be seen<strong>in</strong> Table 1, nonresi<strong>den</strong>ts rated <strong>the</strong> managed landscape <strong>in</strong> Area 2as significantly less beautiful than <strong>the</strong> wild landscape, M = 3.36versus M = 4.15, while resi<strong>den</strong>ts of Area 2 rated <strong>the</strong> managedlandscape <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir area as slightly more beautiful than <strong>the</strong> wildlandscape, M = 4.13 versus M = 4.11. This <strong>in</strong>teraction-effect washighly significant, F(1,499) = 29.03, p < .001.We analyzed beauty rat<strong>in</strong>gs of resi<strong>den</strong>ts of Area 2 <strong>in</strong> moredetail to f<strong>in</strong>d out whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>ir higher preference for managednature applied only to <strong>the</strong>ir own area, or whe<strong>the</strong>r it also appliedto landscapes from <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r five areas. Results of this analysisshowed that resi<strong>den</strong>ts from Area 2 also rated <strong>the</strong> managedlandscape <strong>in</strong> three o<strong>the</strong>r areas significantly more beautiful thano<strong>the</strong>r nonresi<strong>den</strong>ts of <strong>the</strong>se areas, all p’s < .05. This f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g suggeststhat <strong>the</strong> higher preference for managed nature by resi<strong>den</strong>tsof Area 2 reflects a general preference for managed landscapes,

A.E. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, S.L. Koole / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 78 (2006) 362–372 369Table 3Mean beauty rat<strong>in</strong>gs (scale range 1–6) for managed and wild landscapes as afunction of socio-economic variables (standard deviations <strong>in</strong> paren<strong>the</strong>ses)Socio-economic variablesLandscape typeManaged (a) Wild (b) b − a F-valuePlace of resi<strong>den</strong>ceArea 2 (N = 82) 4.07 (.50) 4.11 (.73) .04 15.53 ***O<strong>the</strong>r areas (N = 418) 3.98 (.55) 4.34 (.68) .46Farm<strong>in</strong>g backgroundFarmers (N = 91) 4.12 (.54) 4.04 (.77) −.08 33.11 ***Nonfarmers (N = 409) 3.88 (.54) 4.37 (.66) .49Age

370 A.E. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, S.L. Koole / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 78 (2006) 362–372preferences for nature development landscapes (Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>,2003; Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong> and Vlek, 1998; Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong> et al., 1998,<strong>in</strong> press).Averaged across <strong>the</strong> six areas, plans to develop wild naturalsett<strong>in</strong>gs were rated as more beautiful than plans to developmanaged sett<strong>in</strong>gs. This f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g fits well with f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of studies<strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r countries, which have also found a general “taste for<strong>wilderness</strong>” (e.g., Arriaza et al., 2004). However, it is importantto note that <strong>the</strong> present research did not employ representativesamples of respon<strong>den</strong>ts and landscapes. The present f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gthat <strong>wilderness</strong> landscapes were generally preferred over managednatural landscapes should <strong>the</strong>refore be <strong>in</strong>terpreted withcaution.Although wild nature development landscapes were generallypreferred over managed landscapes, <strong>wilderness</strong> was notappreciated <strong>in</strong> all areas. In <strong>the</strong> fourth area, a plan to developa wild forest was evaluated less beautiful than a plan to developa more managed forest. Both resi<strong>den</strong>ts and nonresi<strong>den</strong>ts displayeda preference for <strong>the</strong> managed forest, which suggests thatthis f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g cannot be attributed to contextual <strong>in</strong>fluences, such asa resistance to change by local resi<strong>den</strong>ts. Conceivably, <strong>the</strong> wildnatural landscape <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> fourth area may have received low preferencerat<strong>in</strong>gs because of <strong>the</strong> <strong>den</strong>se foreground and mid-groundunderbrush, characteristics which have been found to <strong>in</strong>fluencevisual preferences for forests <strong>in</strong> a negative way, irrespective of<strong>the</strong> degree of <strong>wilderness</strong> (Schroeder and Daniel, 1981; Brownand Daniel, 1986). Alternatively, it is also possible that <strong>wilderness</strong>is less appreciated <strong>in</strong> forests than <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r types of naturallandscapes because structure and order are more important <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong>se highly <strong>den</strong>se and complex environments.Consistent with our expectations, local resi<strong>den</strong>ts displayedhigher preferences for <strong>the</strong> development of managed nature <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong>ir area than nonresi<strong>den</strong>ts. Resi<strong>den</strong>ts did not, however, displaylower preferences for <strong>the</strong> development of wild nature <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong>ir area than nonresi<strong>den</strong>ts. The higher preference for managednature was strongest among resi<strong>den</strong>ts of <strong>the</strong> second plan area(Area “De Burd” <strong>in</strong> Friesland). Because <strong>the</strong>re had been somelocal resistance to nature development <strong>in</strong> this area, higher preferencesfor managed nature by resi<strong>den</strong>ts of this area may havereflected a momentary <strong>in</strong>fluence of <strong>the</strong> planned-change context(cf. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong> and Vlek, 1998). However, resi<strong>den</strong>ts of <strong>the</strong> secondarea also displayed higher preferences for managed nature <strong>in</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r regions, which po<strong>in</strong>ts to a more generic effect of familiarityor experience with rural landscapes. Still, because geographicalregion of resi<strong>den</strong>ce was confounded with characteristics of localplann<strong>in</strong>g procedures, <strong>in</strong>terpretations of differences between resi<strong>den</strong>tsand nonresi<strong>den</strong>ts must rema<strong>in</strong> tentative.Among <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r socio-economic variables <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>study, age, socio-economic status, farm<strong>in</strong>g background, an<strong>den</strong>vironmentalism were all found to be significantly relatedto <strong>in</strong>dividual differences <strong>in</strong> preferences for <strong>wilderness</strong>. Asexpected, farmers, older respon<strong>den</strong>ts, and respon<strong>den</strong>ts with lowlevels of <strong>in</strong>come and education displayed relatively low preferencesfor wild natural landscapes, while respon<strong>den</strong>ts witha preference for green political parties, younger respon<strong>den</strong>ts,and respon<strong>den</strong>ts with high levels of <strong>in</strong>come and education, displayedrelatively high preferences for wild nature. As <strong>in</strong> previousresearch (e.g. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong> et al., <strong>in</strong> press) even groups with <strong>the</strong>lowest preferences for <strong>wilderness</strong>, such as farmers, did not ratemanaged nature as significantly more beautiful than wild nature.Ra<strong>the</strong>r, respon<strong>den</strong>ts from <strong>the</strong>se groups rated managed and wildnature as equally beautiful.In l<strong>in</strong>e with our predictions, respon<strong>den</strong>ts who <strong>in</strong>dicated that<strong>the</strong>y visited nature for restoration, reflection, and to study plantsand animals, displayed higher preferences for wild natural landscapesthan respon<strong>den</strong>ts for whom <strong>the</strong>se motives were lessimportant. These f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs speak to <strong>the</strong> adaptive role of visualpreferences <strong>in</strong> guid<strong>in</strong>g and direct<strong>in</strong>g perceivers to landscapesthat promise to fulfill <strong>the</strong>ir needs (Staats et al., 2003; Koole andVan <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, 2004, 2005; Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong> et al., 2003). Still,recreational motives expla<strong>in</strong>ed only 3% of <strong>the</strong> variance. Consequently,<strong>in</strong>dividual differences <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> appreciation of <strong>wilderness</strong>could not be exhaustively expla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> terms of differences <strong>in</strong>recreational motives.4.1. Limitations and practical implicationsThe present research is subject to several limitations. First,we exam<strong>in</strong>ed people’s evaluations of photographs ra<strong>the</strong>r thanactual natural sett<strong>in</strong>gs. Fortunately, various studies have reportedhigh levels of consistency between visual preferences based onphotographs and parallel responses based on direct experienceof <strong>the</strong> represented landscapes (Daniel, 1990; Kellomaki andSavola<strong>in</strong>en, 1984; Stamps, 1990). Moreover, <strong>the</strong> preference forwild nature that was obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> present research was corroborated<strong>in</strong> recent Dutch survey among local respon<strong>den</strong>ts whohad had direct experience with nature development landscapes(Buijs et al., 2004). Based on <strong>the</strong>se results, it seems likely that<strong>the</strong> current results will generalize to evaluations of actual naturalsett<strong>in</strong>gs.A fur<strong>the</strong>r limitation is that <strong>the</strong> present research used onlyDutch respon<strong>den</strong>ts. There is reason to believe, however, thatour f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are rele<strong>van</strong>t to o<strong>the</strong>r cultures as well. Studies <strong>in</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r countries, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g nonwestern nations such as Nepal,have yielded similar differences <strong>in</strong> preferences for <strong>wilderness</strong>among groups from different socio-economic backgrounds (seeDurrant and Shumway (2004), for an overview). Never<strong>the</strong>less,it would be <strong>in</strong>formative to extend <strong>the</strong> current analysis to o<strong>the</strong>rcountries, <strong>in</strong> particular countries where <strong>wilderness</strong> is less scarcethan <strong>in</strong> The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands.F<strong>in</strong>ally, recreational motives were each assessed by only oneitem <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> present research. This relatively crude measurementmay have suppressed <strong>the</strong> predictive power of recreationalmotives. Future work should be directed toward construct<strong>in</strong>g alarger pool of items that covers <strong>the</strong> entire range of recreationalmotives <strong>in</strong> order to obta<strong>in</strong> a better test of <strong>the</strong> rele<strong>van</strong>ce of motivationalaccounts for understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividual differences <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>appreciation of <strong>wilderness</strong>.Despite <strong>the</strong> aforementioned limitations, <strong>the</strong> present researchmay have some important practical implications for land agencies.The f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> majority of respon<strong>den</strong>ts evaluated plansfor nature development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir area as beautiful provides a rationalefor <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>uation and implementation of nature developmentstrategies. However, as already noted, this f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g should

A.E. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, S.L. Koole / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 78 (2006) 362–372 371be <strong>in</strong>terpreted with caution because <strong>the</strong> study did not employ representativesamples of responses. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, local authoritiesmay use <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation on <strong>in</strong>dividual differences <strong>in</strong> preferencesfor wild versus managed nature to make <strong>in</strong>formed decisions on<strong>the</strong> application of active versus passive management strategies.A f<strong>in</strong>al f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g with practical value for land agencies is that evaluationsof local resi<strong>den</strong>ts were not strongly <strong>in</strong>fluenced by <strong>the</strong>irplace of resi<strong>den</strong>ce, even though <strong>the</strong>y were confronted with realisticalternatives for each of <strong>the</strong> six areas. Based on this result,resi<strong>den</strong>ts’ evaluations of nature development plans should not bedismissed too easily as be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>duced by <strong>the</strong> local change context.Ra<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>put of resi<strong>den</strong>ts deserves to be taken seriouslyas a useful source of <strong>in</strong>formation regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> visual quality ofnature development plans.Appendix A. Background <strong>in</strong>formation on naturedevelopment (translated from Dutch)A.1. Nature management: What does it mean?The concept of ‘nature management’ refers to all measuresthat are aimed at streng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g nature values. The circumstances<strong>in</strong> an area are adjusted <strong>in</strong> such a manner that more plants andanimals can live <strong>the</strong>re. In this questionnaire, we will make a dist<strong>in</strong>ctionbetween two types of nature management: active naturemanagement, and passive nature management. Actively managedlandscapes will be <strong>in</strong>dicated with <strong>the</strong> letter A, passivelymanaged landscapes will be <strong>in</strong>dicated with <strong>the</strong> letter B.A.2. Active nature managementActive nature management implies that nature is cont<strong>in</strong>uouslyguided and streng<strong>the</strong>ned by measures such as graz<strong>in</strong>g, adjust<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> water level, mow<strong>in</strong>g, cutt<strong>in</strong>g, and dredg<strong>in</strong>g. In most cases,active nature management is applied to comb<strong>in</strong>e nature valueswith o<strong>the</strong>r values, like agriculture, recreation or <strong>the</strong> cultural historyof an area. Active nature management can be carried out byfarmers, or by national nature management organizations.A.3. Passive nature managementPassive nature management implies that nature <strong>in</strong> an area isleft to reign freely as much as possible. To start this process,human <strong>in</strong>terventions such as clean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> soil or restor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>orig<strong>in</strong>al water level are often required. These <strong>in</strong>terventions arecarried out by nature management organizations. After <strong>the</strong>se<strong>in</strong>terventions species of plants and animals are left to evolve on<strong>the</strong>ir own. The only management that takes place is graz<strong>in</strong>g, forexample by wild horses or cows.ReferencesArriaza, M., Cañas-Ortega, J.F., Cañas-Madueño, J.A., Ruiz-Aviles, P., 2004.Assess<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> visual quality of rural landscapes. Landscape Urban Plann.69, 115–125.Bal, D., Beije, H.M., Hoogeveen, Y.R., Jansen, S.R.J., Van der Reest, P.J., 1996.Handboek natuurdoeltypen <strong>in</strong> Nederland [The Handbook of Target NatureTypes <strong>in</strong> The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands]. National Reference Centre for Nature Management,Wagen<strong>in</strong>gen (with English summary).Ball<strong>in</strong>g, J.D., Falk, J.H., 1982. Development of visual preference for naturalenvironments. Environ. Behav. 14, 5–28.B<strong>in</strong>der, A., 1984. Restrictions on statistics imposed by method of measurement:some reality, some myth. J. Crim<strong>in</strong>al Justice 12, 467–481.Brown, T.C., Daniel, T.C., 1986. Predict<strong>in</strong>g scenic beauty of timber stands. For.Sci. 32, 417–487.Brush, R., Chenoweth, R.E., Barman, T., 2000. Group differences <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> enjoyabilityof driv<strong>in</strong>g through rural landscapes. Landscape Urban Plann. 47,39–45.Bryk, A.S., Rau<strong>den</strong>bush, S.W., 1992. Hierarchical L<strong>in</strong>ear Models: Applicationsand Data Analysis. Sage Publications, London.Buijs, A.E., De Boer, T.A., Gerritsen, A.L., Langers, F., De Vries, S., VanW<strong>in</strong>sum-Westra, M., 2004. Gevoelsrendement <strong>van</strong> natuurontwikkel<strong>in</strong>g langsde rivieren [Affective value of nature development along rivers]. Report 868.Alterra, Wagen<strong>in</strong>gen.Cooper, A.A., Third Earl of Shaftesbury (1709), 1999. The Moralists: A PhilosophicalRhapsody, Characteristics of Men, Manners, Op<strong>in</strong>ions, Times.Clarendon, Oxford.Daniel, T.C., 1990. Measur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> quality of <strong>the</strong> natural environment: A psychophysicalapproach. Am. Psychol. 45, 633–637.Davis, M.A., Slobodk<strong>in</strong>, L.B., 2004. The science and values of restoration ecology.Restor. Ecol. 12, 1–3.Dear<strong>den</strong>, P., 1984. Factors <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g landscape preferences: an empirical <strong>in</strong>vestigation.Landscape Plann. 11, 293–306.Durrant, J.O., Shumway, J.M., 2004. Attitudes toward <strong>wilderness</strong> study areas: asurvey of six Sou<strong>the</strong>astern Utah counties. Environ. Manage. 33, 271–283.Fiallo, E., Jacobsen, S., 1995. Local communities and protected areas: attitudesof rural resi<strong>den</strong>ts towards conservation and Machalilla National Park,Ecuador. Environ. Conserv. 22, 241–249.Gallagher, T.J., 1977. Visual preference for alternative natural landscapes.Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.Gobster, P.H., 1999. An ecological aes<strong>the</strong>tic for forest landscape management.Landscape J. 18 (1), 54–64.González Bernaldez, F., Parra, F., 1979. Dimensions of landscape preferencesfrom pairwise comparisons. In: Elsner, G.H., Smardon, R.D. (Eds.), Proceed<strong>in</strong>gsof Our National Landscape. A Conference on Applied Techniquesfor Analysis and Management of <strong>the</strong> Visual Resource. GeneralTechnical Report PSW-35. USDA Forest Service, Pacific SouthwestForest and Range Experiment Station, Berkeley, CA, pp. 256–262.Hartig, T., E<strong>van</strong>s, G.W., 1993. Psychological foundations of nature experience.In: Gärl<strong>in</strong>g, T., Golledge, R.G. (Eds.), Behavior and Environment:Psychological and Geographical Approaches. Elsevier Science Publishers,Amsterdam, pp. 427–457.Hendee, J.C., Stankey, G.H., Lucas, R.C., 1990. Wilderness Management, 2nded. North American Press, Gol<strong>den</strong>, CO.Hobbs, R.J., Harris, J.A., 2001. Restoration ecology: repair<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> earth’s ecosystems<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> new millennium. Restor. Ecol. 9, 239–246.Hobbs, R.J., Norton, D.A., 1996. Towards a conceptual framework for restorationecology. Restor. Ecol. 4, 93–110.Jaccard, J., Wan, C.K., 1996. LISREL Approaches to Interaction Effects <strong>in</strong>Multiple Regression. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.Johnson, B., 2002. On <strong>the</strong> spiritual benefits of <strong>wilderness</strong>. Int. J. Wilderness 8,28–32.Jongman, R.H.G., Külvik, M., Kristiansen, I., 2004. European ecological networksand greenways. Landscape Urban Plann. 68, 305–319.Kaplan, R., Herbert, E.J., 1987. Cultural and subcultural comparisons <strong>in</strong> preferencefor natural sett<strong>in</strong>gs. Landscape Urban Plann. 14, 281–293.Kaplan, R., Kaplan, S., 1989. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective.Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.Kellomaki, S., Savola<strong>in</strong>en, R., 1984. The scenic value of <strong>the</strong> forest landscapeas assessed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> field and <strong>the</strong> laboratory. Landscape Plann. 11, 97–107.Knopf, R.C., 1983. Recreational needs and behavior <strong>in</strong> natural sett<strong>in</strong>gs. In: Altman,I., Wohlwill, J.F. (Eds.), Human Behavior and Environment: Ad<strong>van</strong>ces<strong>in</strong> Theory and Research, vol. 6. Plenum Press, <strong>New</strong> York, pp. 205–240.

372 A.E. Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, S.L. Koole / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 78 (2006) 362–372Knopf, R.C., Peterson, G.L., Lea<strong>the</strong>rberry, E.C., 1983. Motives for recreationalriver float<strong>in</strong>g: relative consistency across sett<strong>in</strong>gs. Leisure Sci. 5, 231–255.Koole, S.L., Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, A.E., 2004. Paradise lost and reclaimed: a motivationalanalysis of human–nature relations. In: Greenberg, J., Koole, S.L.,Pyszcz<strong>in</strong>sky, T. (Eds.), Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology.Guildford, <strong>New</strong> York.Koole, S.L., Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, A.E., 2005. Lost <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>wilderness</strong>: terror management,action control, and evaluations of nature. J. Personal. Social Psychol..Lyons, E., 1983. Socio-economic correlates of landscape preference. Environ.Behav. 15, 487–511.M<strong>in</strong>istry of Agriculture, Nature management, and Fisheries of The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands,1996. Nature conservation policy <strong>in</strong> The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands: objectives, methodsand results. Report nr. B-16. National Reference Centre for Nature Management,Wagen<strong>in</strong>gen.Nash, R., 1967. Wilderness and <strong>the</strong> American M<strong>in</strong>d. Yale University Press, <strong>New</strong>Haven, CT.Nunnally, J., 1978. Psychometric Theory. McGraw-Hill, <strong>New</strong> York.Orland, B., 1988. Aes<strong>the</strong>tic preference for rural landscapes: some resi<strong>den</strong>t andvisitor differences. In: Nasar, J. (Ed.), Environmental Aes<strong>the</strong>tics: Theory,Research, and Applications. Cambridge University Press, <strong>New</strong> York, pp.364–378.Parsons, R., Daniel, T.C., 2002. Good look<strong>in</strong>g: <strong>in</strong> defense of scenic landscapeaes<strong>the</strong>tics. Landscape Urban Plann. 60, 43–56.Ribe, R.G., 1994. Scenic beauty perceptions along <strong>the</strong> ROS. J. Environ. Manage.42, 199–221.Roggenbuck, J.W., Lucas, R.C., 1987. Wilderness use and user characteristics:a state-of-knowledge review. In: Lucas, R.C. (Ed.), Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs of<strong>the</strong> National Wilderness Research Conference: Issues, State-of-knowledge,Future Directions. General Technical Report INT-220. United Stated Departmentof Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermounta<strong>in</strong> Research Station, Og<strong>den</strong>,UT, pp. 204–345.Schroeder, H.S., Daniel, T.C., 1981. Progress <strong>in</strong> predict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> scenic beauty offorest landscapes. For. Sci. 27, 71–80.SER, Society for Ecological Restoration Science & Policy Work<strong>in</strong>g Group,2002. The SER Primer on Ecological Restoration. www.ser.org/.Staats, H., Kieviet, A., Hartig, T., 2003. Where to recover from attentionalfatigue: an expectancy-value analysis of environmental preference. J. Environ.Psychol. 23, 147–157.Stamps, A.E., 1990. Use of photographs to simulate environments. A metaanalysis.Percept. Motor Skills 71, 907–913.Stankey, G.H., Schreyer, R., 1987. Attitudes toward <strong>wilderness</strong> and factorsaffect<strong>in</strong>g visitor behavior: a state-of-knowledge review. In: Lucas, R.C. (Ed.),Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs of <strong>the</strong> National Wilderness Research Conference: Issues, Stateof-knowledge,Future directions. General Technical Report INT-220. UnitedStated Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermounta<strong>in</strong> ResearchStation, Og<strong>den</strong>, UT, pp. 246–293.Strumse, E., 1996. Socio-economic differences <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> visual preferencesfor agrarian landscapes <strong>in</strong> western Norway. J. Environ. Psychol. 16, 1–15.Swart, J.A.A., Van der W<strong>in</strong>dt, H.J., Keulartz, J., 2001. Valuation of nature <strong>in</strong>conservation and restoration. Restor. Ecol. 9, 230–238.Thacker, C., 1983. The Wildness Pleases: The Orig<strong>in</strong>s of Romanticism. CroomHelm, London.Ulrich, S.R., 1993. Biophilia, biophobia and natural landscapes. In: Kellert, S.R.,Wilson, E.O. (Eds.), The Biophilia Hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. Island Press, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton,DC.Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, A.E., 1999. Individual differences <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> aes<strong>the</strong>tic evaluationof natural landscapes. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Universityof Gron<strong>in</strong>gen, Gron<strong>in</strong>gen. Retrieved January 22, 2006, from http://dissertations.ub.rug.nl/faculties/ppsw/1999/a.e.<strong>van</strong>.der.berg/.Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, A.E., 2003. Personal need for structure and environmentalpreference. In: Hendrickx, L., Jager, W., Steg, L. (Eds.), Human DecisionMak<strong>in</strong>g and Environmental Perception: Understand<strong>in</strong>g and Assist<strong>in</strong>gHuman Decision Mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Real-life Sett<strong>in</strong>gs. RijksuniversiteitGron<strong>in</strong>gen, Gron<strong>in</strong>gen, pp. 129–148. Retrieved January 22, 2006, fromhttp://www.agnes<strong>van</strong><strong>den</strong>berg.nl/nfs.pdf.Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, A.E., De Vries, D., Vlek, C.A.J., <strong>in</strong> press. Images of nature,environmental values, and landscape preference: Explor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir relationships.In: Van <strong>den</strong> Born, R.J.G, De Groot, W.T., Lenders, R.H.J.(Eds.), A Scientific Exploration of People’s Implicit Philosophies regard<strong>in</strong>gnature <strong>in</strong> Germany, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands and <strong>the</strong> United K<strong>in</strong>gdom.LIT-Verlag, Münster. Retrieved January 22, 2006, from http://www.agnes<strong>van</strong><strong>den</strong>berg.nl/images.pdf.Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, A.E., Koole, S.L., Van der Wulp, N.Y., 2003. Environmentalpreference and restoration: (How) are <strong>the</strong>y related? J. Environ. Psychol. 23,135–146.Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, A.E., Vlek, C.A.J., 1998. The <strong>in</strong>fluence of planned-change contexton <strong>the</strong> evaluation of natural landscapes. Landscape Urban Plann. 43, 1–10.Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong>, A.E., Vlek, C.A.J., Coeterier, J.F., 1998. Group differences <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>aes<strong>the</strong>tic evaluation of nature development plans: a multilevel approach. J.Environ. Psychol. 18, 141–157.Vir<strong>den</strong>, R.J., 1990. A comparison study of <strong>wilderness</strong> users and non-users: implicationsfor managers and policymakers. J. Park Recreation Adm<strong>in</strong>. 8, 13–24.Wellman, J.D., Buyhoff, G.J., 1980. Effects of regional familiarity on landscapepreferences. J. Environ. Manage. 11, 105–110.Wohlwill, J.F., 1983. The concept of nature: a psychologist’s view. In: Altman,I., Wohlwill, J.F. (Eds.), Human Behavior and Environment: Ad<strong>van</strong>ces <strong>in</strong>Theory and Research, vol. 6. Plenum Press, <strong>New</strong> York, pp. 5–37.Zumbo, B.D., Zimmerman, D.W., 1993. Is <strong>the</strong> selection of statistical methodsgoverned by level of measurement? Can. Psychol. 35, 390–399.<strong>Agnes</strong> Van <strong>den</strong> <strong>Berg</strong> received her PhD <strong>in</strong> environmental psychology for researchon <strong>in</strong>dividual differences <strong>in</strong> preferences for natural landscapes. She currentlyworks as an associate professor and senior researcher at Wagen<strong>in</strong>gen Universityand Research Center. Her research focuses on basic and applied aspects ofhuman–environment relationships, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g health benefits of nature, fear ofnature, and <strong>the</strong> spatial translation of people’s nature experiences.Sander Koole holds a PhD <strong>in</strong> social psychology. He is currently an associateprofessor at <strong>the</strong> Vrije Universiteit <strong>in</strong> Amsterdam, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands. His research<strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude emotion regulation, <strong>the</strong> self, and experimental existential psychology.