Ready, Set, Go! Training Manual - Georgia 4-H

Ready, Set, Go! Training Manual - Georgia 4-H

Ready, Set, Go! Training Manual - Georgia 4-H

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

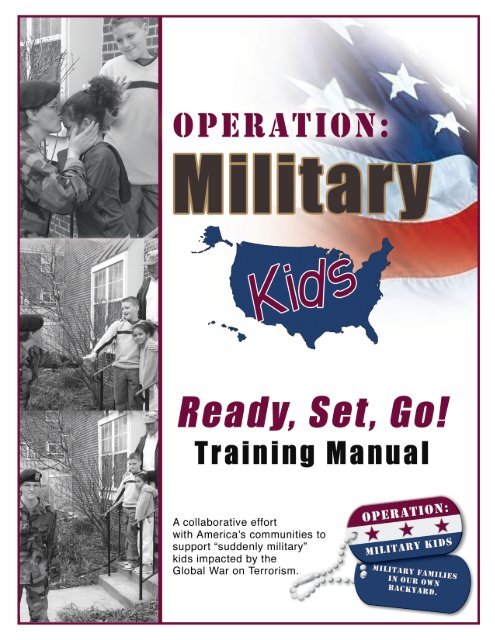

Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>April 20073rd EditionOperation: Military Kids, <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! is a program of the USDA Army Youth Development Project,a collaboration of the U.S. Army Child & Youth Services and the Cooperative State Research,Education, and Extension Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture through Washington State University/WashingtonState Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. Users are encouraged touse all or parts of this information, giving credit to U.S. Army Child & Youth Services and USDACooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service in all printed materials.PrefacePage 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Contributors:Darrin W. Allen, 4-H/Army Youth Development ProjectLinda Bull, Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public InstructionNancy Campbell, U.S. Army Child & Youth ServicesNora Clouse, U.S. Army Child & Youth ServicesMona M. Johnson, Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public InstructionC. Eddy Mentzer, USDA, Cooperative State Research, Education and ExtensionServiceKelly Oram, 4-H/Army Youth Development Project Curriculum SpecialistRob Stout, Print Manager, Washington State University ExtensionMelissa Strong, Graphic Designer, Washington State University ExtensionLagene Taylor, Project Manager, Washington State University ExtensionKevin Wright, Washington State University 4-H Youth DevelopmentThe work of the committee could not have been successful withoutthe support and encouragement of the Operation Military Kids PartnerOrganizations:Tim Richardson, Boys & Girls Clubs of America, Mary Keller, Military ChildEducation Coalition, Kathy <strong>Go</strong>edde, National Guard Bureau Guild and YouthServices Program Manager, Pamela McBride, United States Army Reserve Child &Youth Services Program Manager, Jason Kees, The American Legion, M.-A. LucasUS Army Child and Youth Services, Sharon KB Wright, USDA, Cooperative StateResearch, Education and Extension ServiceSpecial thanks to Washington State OMK Team for developingthe original manual:LTC Beverly White, Washington State National GuardRenee J. Weglage, United States Army Reserve 104th DivisionM. Christine Price, Washington State University 4-H Youth DevelopmentAnnie DeAndrea, Washington State National Guard Family ProgramsAstri Zidack, Educational Service District 101Ruthy Cowles-Porterfield, Washington State Office of Superintendent ofPublic InstructionVisa Detsadachanh, Washington State University 4-H Youth DevelopmentPrefacePage II3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Table of ContentsChapter 1: Introduction to <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>!Lesson Plan........................................................................................................1-1Evaluation Questions.........................................................................................1-2<strong>Training</strong> Session Content...................................................................................1-3Background MaterialRSG! <strong>Training</strong> Agenda..............................................................................1-25RSG! <strong>Training</strong> Materials Supplemental Resources CD................................1-26RSG! Participant Pre-/Post-Test.................................................................1-27RSG! Participant Pre-/Post-Test Answer Key..............................................1-29Chapter 2: A New Reality: Impact of the Global War on TerrorismLesson Plan........................................................................................................2-1Evaluation Questions.........................................................................................2-3<strong>Training</strong> Session Content...................................................................................2-4Chapter 3: Introducing Operation: Military Kids and the OMKImplementation FrameworkLesson Plan........................................................................................................3-1Evaluation Questions.........................................................................................3-3<strong>Training</strong> Session Content...................................................................................3-4Background MaterialOverview of Army Child & Youth Services................................................3-49Overview of National 4-H Program .........................................................3-55Boys & Girls Clubs of America .................................................................3-60The American Legion OMK Fact Sheet.....................................................3-65Military Child Education Coalition (MCEC) Description............................3-68Speak Out for Military Kids (SOMK) Program Overview...........................3-72Hero Pack Project Overview.....................................................................3-76Chapter 4: Exploring Military CultureLesson Plan........................................................................................................4-1Evaluation Questions.........................................................................................4-2<strong>Training</strong> Session Content...................................................................................4-3Background MaterialArmy Values.............................................................................................4-29The Soldier’s Creed..................................................................................4-29The Soldier’s Code...................................................................................4-30US Army Chain of Command...................................................................4-30US Army Ranks and Insignias...................................................................4-30Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionPrefacePage III

Military Service Ribbons and Awards........................................................4-30US Army Acronyms..................................................................................4-31Chapter 5: The Emotional Cycle of Deployment: Mobilization andDeploymentLesson Plan........................................................................................................5-1Evaluation Questions.........................................................................................5-3<strong>Training</strong> Session Content...................................................................................5-4Background MaterialActivity Instructions: A Blanket Community..............................................5-33The Emotional Cycle of Deployment: A Military Family Perspective..........5-34Strengths Resulting from the Deployment Cycle/Stages ..........................5-42Helping Children Adjust While Their Military Parent Is Away ...................5-43Helping the Nonmilitary Parent during a Spouse’s Extended Absence .....5-44Talk to Your Children about Deployment…Before It Happens .................5-45Deployment Stress Related Issues ............................................................5-48Chapter 6: The Emotional Cycle of Deployment: Homecoming and ReunionLesson Plan........................................................................................................6-1Evaluation Questions.........................................................................................6-2<strong>Training</strong> Session Content...................................................................................6-3Background MaterialThe Myth of the “Perfect” Reunion (Answer Key).....................................6-15Helping Children Adjust to Reunion ........................................................6-16Tips for Parents to Keep in Mind .............................................................6-18Tips for the Service Member ...................................................................6-19Tips for Spouse .......................................................................................6-21Children and Reunion .............................................................................6-22Chapter 7: Stress and Coping StrategiesLesson Plan........................................................................................................7-1Evaluation Questions.........................................................................................7-2<strong>Training</strong> Session Content...................................................................................7-3Background MaterialPotato Head Family (Activity Instructions)................................................7-39Stress and Coping In Childhood-Avis Brenner..........................................7-40Stress and Young Children-ERIC Digest, Jan Jewett,and Karen Peterson............................................................................7-48Helping Children Cope With Stress-Karen DeBord...................................7-52Recognizing Stress In Children-NC State University, A&TState University Cooperative Extension..............................................7-58PrefacePage IV3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Strategies for Parents and Teachers-NC State University, A&T StateUniversity Cooperative Extension.......................................................7-63Types of Prevention Strategies-National Institute of Drug Abuse..............7-71Chapter 8: Impact of Grief, Loss and TraumaLesson Plan........................................................................................................8-1Evaluation Questions.........................................................................................8-2<strong>Training</strong> Session Content...................................................................................8-3Background MaterialChildren and Grief: What They Know, How They Feel, How To Help .......8-35Resources for Wounded or Injured Servicemembers and their Families.....8-43America at War: Our Attitude Makes a Difference ...................................8-51America at War: Helping Children Cope ..................................................8-53Fears .......................................................................................................8-55Drugs, Alcohol, and Your Kid ..................................................................8-59Reactions and Guidelines for Children Following Trauma/Disaster ...........8-62Chapter 9: Fostering Resilience in Children and YouthLesson Plan........................................................................................................9-1Evaluation Questions ........................................................................................9-2<strong>Training</strong> Session Content...................................................................................9-3Background MaterialFostering Resiliency in Children and Youth: Four Basic Steps forFamilies, Educators, and Other Caring Adults.....................................9-19Resiliency Requires Changing Hearts and Minds......................................9-29Fostering Resiliency in Kids: Protective Factors in the Family, School,and Community................................................................................9-34The Children of Kauai: Resiliency and Recovery in Adolescenceand Adulthood...................................................................................9-6240 Developmental Assets.........................................................................9-72Risk and Protective Factor Framework .....................................................9-73Fostering Resilience in Time of War..........................................................9-74Building Resilience in Children in the Face of Fear and Tragedy................9-75Promoting Resilience in Military Children and Adolescents.......................9-79Bounce Back (Activity Instructions)..........................................................9-92Chapter 10: Understanding the Influence of the MediaLesson Plan......................................................................................................10-1Evaluation Questions ......................................................................................10-2<strong>Training</strong> Session Content.................................................................................10-3Background MaterialTalking to Children about Terrorism and War.........................................10-13Children and TV Violence.......................................................................10-19Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionPrefacePage

Talking with Kids about Violent Images of War.......................................10-22Chapter 11: Building Community Capacity to Take ActionLesson Plan......................................................................................................11-1Evaluation Questions ......................................................................................11-2<strong>Training</strong> Session Content.................................................................................11-3Background MaterialCollaboration Framework…Addressing Community Capacity................11-29Community Tool Box—VMOSA ............................................................11-49Community Tool Box—Proclaiming Your Dream: Developing Visionand Mission Statements...................................................................11-56Community Tool Box—Creating Objectives ..........................................11-66Community Tool Box—Developing Successful Strategies:Planning to Win................................................................................11-75Community Tool Box—Action Plan .......................................................11-81Community Wellness Multiplied............................................................11-88Chapter 12: Operation: Military Kids ... Next StepsLesson Plan......................................................................................................12-1Evaluation Questions.......................................................................................12-2<strong>Training</strong> Session Content.................................................................................12-3Chapter 13: ResourcesLesson Plan......................................................................................................13-1Evaluation Questions ......................................................................................13-1Background MaterialSample Two-Hour <strong>Training</strong> Plan...............................................................13-3Website Listings for Resources..................................................................13-4OMK Best Practices..................................................................................13-7Appendix A: <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong>—Read Ahead MaterialsAppendix B: JournalAppendix C: EnergizersPrefacePage VI3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Chapter One:Introduction to <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>!I. Lesson PlanA. Purpose: Introduce participants to the training and assist them in gettingacquainted.B. Objectives:1. Articulate training purpose and anticipated outcomes.2. Review training materials provided to participants for future use.3. Engage in group activities to get to know one another.4. Provide participants with understanding of unique stressors that“suddenly military” families face.5. Provide tools and skills to teams to create comprehensive action plansto make OMK an effective support network for National Guard andArmy Reserve families.C. Time: 60 minutesD. Preparation/Materials Needed:✪ <strong>Training</strong> logistic arrangements✪ Instructor training materials: PowerPoint slides, training manual, andagenda✪ Participant copies: <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>s, Pre-/Post-Test,“Walk This Way” activity, CD ROM with copy of RSG! <strong>Manual</strong> and otherresources/materials✪ Pre-Test answer key✪ Calculator to determine class “mean” score for pre-testII. <strong>Training</strong> Session ContentA. PowerPoint SlidesSlide 1-1: Operation: Military Kids—Introduction to <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>!<strong>Training</strong>Slide 1-2: Welcome and IntroductionsSlide 1-3: Ground Rules for the <strong>Training</strong>Slide 1-4: CommonalitiesSlide 1-5: What We Will AccomplishSlide 1-6: <strong>Training</strong> AgendaOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page

Slide 1-7: Purpose of <strong>Training</strong>Slide 1-8: <strong>Training</strong> Materials ProvidedSlide 1-9: How to Use the <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Manual</strong>Slide 1-10: Anticipated OutcomesSlide 1-11: Participant Pre-TestSlide 1-12: “Until Then”Slide 1-13: “What’s in the News”Slide 1-14: What Do Military Youth Have to Say?Slide 1-15: Questions, Comments, Thoughts?B. Activities and Directions1. Trainer-of-Trainers Agenda for Participants• Distribute to participants• Discuss and answer questions2. Participant Pre-Test• Have all participants take test (may want to do this as they enter)• Score tests and determine class mean score• Review responses and relate answers to the rest of the training3. Commonalities• Have participants form small groups• Brainstorm as many things that all members have in common andtwo unique things about each person in the group• Debrief the activity by having participants share what the membersof the group have in commonIII. Must-Read Background MaterialA. Trainer-of-Trainers AgendaB. <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! Supplemental Resources CD Content ListC. Participant Pre-/Post-TestD. Appendix A: OMK Read Ahead MaterialsIV. EvaluationA. Reflection Questions1. What happened when you completed the “Walk This Way” activity?2. Were you surprised at how many individuals did/didn’t have similarexperiences on the activity?3. What struck you as the most important point in this activity?B. Application Questions1. How can you use this information with colleagues to address the needsof youth impacted by the deployment of a parent or loved one?2. How can you use this information to make your Operation: Military KidsTeam more attuned to the needs of military youth at the state, regional,or local level?Chapter 1Page 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Chapter 1:Introduction toOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong>WelcomeWe Are Glad You Are Here!Slide 1-1: Introduction to Operation: Military Kids <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong>Content of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: Try to set a professional, upbeat, safe, and fun atmosphere.What to Do, What to SayDo:• Review content of slide with participants.• Speak with a great amount of energy! Smile…be warm and relaxed…Say: Hello and welcome to the OMK <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong>! We are so happy thatyou could all be here. We are excited and looking forward to working with youover the next three days.Over the next hour we are going to get to know each other, talk about thegoals of the RSG! <strong>Training</strong>, and review the materials we will be working withthis week.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page

Welcome and IntroductionsWho Are Your Teammates?• Name• Where You Work• One Expectation for this <strong>Training</strong>• One Thing About YourselfSlide 1-2: Welcome and IntroductionsContent of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to SayDo:• Review content of slide with participants.• Introduce training team and other Headquarters staff.Say: I would like to introduce your training team for the week.Do:• Have training team introduce themselves.Say: Now we want to get to know something about all of you.Let’s go around the room and please tell us your name, where you work, whatyou do, and why you are here today. What are your expectations for this training?Chapter 1Page 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Do:• Pass the microphone around the room and have each person talk to thegroup.• Review training logistics.Say: Now I will tell you about the important details for the week, for instance,where the bathrooms are (explain), what time we’ll be starting every day(give details), and who to talk with if you have any problems with yourroom (give details).Do:• Check group for understanding.Say: Are there any questions or comments?Do:• Post easel pad sheet labelled “Parking Lot.”Say: Also, as we move through the week, if you have a question during a session, or atnight in your room, please write it down on a Post It note.Do:• Refer to the Post It notes on the table.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page

Ground Rules for the <strong>Training</strong>How Are We <strong>Go</strong>ing To Work TogetherThis Week?Slide 1-3: Ground Rules for the <strong>Training</strong>Content of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: Chart paper and markersTrainer Tips: Get easels with paper and markers ready. Assign someone to record participantresponses. Post responses after completion of activity for duration of training.What to Do, What to SayDo:• Review content of slide with participants.• Through the brainstorming process, come up with a list of ground rulesthat the group will agree to abide by when together.Say: Ok…We want to spend the next few minutes brainstorming some ground rulesthat we can all agree to for our week together. Who would like to start?Do:• Feel free to stimulate discussion with examples like:– <strong>Set</strong> cell phones on silent or vibrate– Ask questions as needed– Be respectfulChapter 1Page 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Do:• Get participants to agree to the ground rules generated.Say: Fantastic…Now raise your hand if you agree to abide by these ground rules andhold others accountable to them as needed.Terrific! It looks like we are all in agreement to have a great week together!Do:• Post ground rules in visible location in training room.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page

Let’s Get to Know Each Other Betterand Play the Game:CommonalitiesSlide 1-4: Let’s Get to Know Each Other Better and Play the Game:CommonalitiesContent of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: Markers, chart paper and easels (or have each group assign someoneto record their brainstorm)Trainer Tips: Make sure chart paper and easel stations are set up prior to beginningthe training.What to Do, What to SayDo: • Divide the participants into groups of about 4 or 5.Say: We are going to be playing the game commonalities.When I say “go” your group has 5-7 minutes to brainstorm as many things thatyou have in common as possible.Nothing obvious like we all have clothes on, shoes, in Kansas City, etc.Chapter 1Page 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Things like we have all been to Europe, or better yet, we have all been to Frankfurt, Germany.Get as detailed as possible!Also, identify one characteristic that is unique to you within your group. Be creative! Not, “Iam the only male in my group,” but, “I won the state baton twirling championship.”Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page

What We Will AccomplishSlide 1-5: A Closer Look at What We Will Accomplish TogetherContent of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to SaySay: We are going to spend some time reviewing our agenda for the week and taking alook at what we want to accomplish.Chapter 1Page 103rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Purpose of <strong>Training</strong>• Give participants an understanding and appreciation ofunique stressors that “suddenly military” families mayface during a deployment.• Provide tools and skills to engage local community OMKpartners to support “suddenly military” children andyouth.• Build a framework to create comprehensive action plansto make OMK an effective statewide support network forNational Guard and Reserve families.Slide 1-6: Purpose of <strong>Training</strong>Content of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to SayDo:• Review content of slide with participants.Say: The purpose of the RSG! training is to provide OMK state teams with the tools andskills to be able to go back and train local partners and build community capacity toenable local community support networks to provide support to “suddenly military”youth.Do:• Check group for understanding.Say: Are there any comments or questions?Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page 11

<strong>Training</strong> AgendaSlide 1-7: <strong>Training</strong> AgendaContent of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: Agenda for the dayTrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to SayDo:• Review content of slide with participants.• Familiarize the audience with the agenda.Say: Now we want to review the agenda for the rest of our time together today.We will do this each day so you will know what we are trying to accomplishfor the day and you will be able to assist us with staying on track.As you can see from the agenda, this training covers a wide variety of topicsand is designed to give you the knowledge, tools, and skills to work with childrenand youth who are experiencing stress due to the deployment and reintegrationof a parent.Chapter 1Page 123rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Say: The structure of the manual is such that each section can be taught as a standalonetopic or grouped together to create any number of different training scenarios.Do:• Check group for understanding.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page 13

How to use the RSG! <strong>Manual</strong>• Train the trainer format• OMK Awareness <strong>Training</strong>• Basis for professional conference workshops• <strong>Training</strong> sessions can be trained individually or in sectionsto tailor training to the needs of local community supportnetworks/teams• Overview of OMK• Content of RSG! can be used to support and develop theHero Pack project, Mobile Technology Lab, andSpeak Out for Military Kids programs• Information is transferable to otherpopulations/circumstances/situationsSlide 1-8: How to Use the RSG! <strong>Manual</strong>Content of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to SayDo:• Review content of slide with participants.Say: This manual is written in a train-the-trainer style and designed to be used in avariety of ways.Do:• Check group for understanding.Say: Are there any comments or questions?Chapter 1Page 143rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

<strong>Training</strong> Materials Provided• CD containing the following materials/resources:— Copy of Operation: Military Kids <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>!<strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>— Copy of PowerPoint Slides for <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong>presentation— Electronic copies of a variety of PDF resources onapplicable military related materialsSlide 1-9: <strong>Training</strong> Materials ProvidedContent of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: RSG! <strong>Manual</strong> and CD to show participantsTrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to SayDo:• Review content of slide with participants.Say: Show the RSG! <strong>Manual</strong> to participants. Reiterate that the training topics can bepresented individually or in groups, whatever meets their needs at the local level.Do:• Review the RSG! CD with the participants.Say: I just want to remind you that this CD contains a wide variety of resourcesbeyond the RSG! <strong>Manual</strong> and we encourage you to become familiar with themas soon as possible.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page 15

Anticipated Outcomes• Participants will increase their understanding of theunique issues facing military, particularly National Guardand Reserve, children/youth impacted by the deploymentof a parent or loved one.• Participants will develop an action plan by conclusion ofthis training to disseminate information and implementOperation: Military Kids program components providedto interested school and community professionals atstate, regional, and local levels.Slide 1-10: Anticipated OutcomesContent of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to SayDo:• Review content of slide with participants.Say: A major focus of this training is to allow your state teams time to formulate plansand strategies on how you will take this train-the-trainer package back to yourstates and use it to help build community capacity to deliver the necessary supportservices in local communities.Do:• Check group for understanding.Say: Are there any comments or questions?Chapter 1Page 163rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Participant Pre-TestMeasuring the Knowledge BaseSlide 1-11: Participant Pre-TestContent of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: Use non-threatening posture when describing pre- and post-tests…some people are stressed by “tests.” Strongly emphasize the fact that this test simplymeasures the amount of knowledge gained from this training, thus participantsshould NOT be able to answer all questions correctly.What to Do, What to SayDo:• Review content of slide with participants.Say: We have covered the order and the topics of the materials we are going to cover thisweek. What we want to do now is find out what you know.We have a very short “pre-test” that we would like you to complete.Do:• Administer pre-test to participants.Say: We will average the scores of this pre-test for the entire group. At the end of thistraining we will administer a post-test and determine the average for this test aswell. I am sure we will see an improvement in test scores!Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page 17

“Until Then”Slide 1-12: “Until Then”Content of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: “Until Then” video presentation, video playerTrainer Tips: Make sure you know where the light switches are located and how tooperate them so you can dim the lights. Also, double check your audio video equipmentto ensure it is working properly.What to Do, What to SayDo:• Transition group into thinking about why they are at the training—which is support children and youth of military families.Say: Over the next hour or so we are going to start to explore the issues that facemilitary children and youth, and discuss how OMK might support them during thisdifficult time.Chapter 1Page 183rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

What is in the News????Slide 1-13: What is in the News????Content of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: Previously collected hardcopy newspaper articles that deal withdeployment of National Guard, Reserve, or Active Duty military personnel. Mobiletechnology labs with internet connection work well with this activity.Trainer Tips: Have 3-5 articles copied for each small group. Make sure all the articlesare not the same so groups talk about different issues. This will stimulate discussionwhen the small group brief back what they discovered.What to Do, What to SayDo:• Break the participants into small groups or state teams as the case may be.Say: Okay, we have talked about the purpose of OMK as being a support system forgeographically dispersed families experiencing deployment. We are going to startexploring the issues families face during a deployment and how OMK can supportthose issues.On your table are a number of articles about deployment. You also have a laptopcomputer with internet connection so you can search for other articles if you choose.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page 19

Do:• Keep time. If all the groups finish reading sooner, move the activity along.Say: Please take the next 10-15 minutes to read through one or two of the articles.As you read the articles you are looking for issues that might make life tough foryoung people.Do:• Give the groups 5-10 minutes to discuss.Say: When everyone in your group has finished reading, spend a few minutesdiscussing what you read and make a list of issues that you found in the articlesthat your group read.Do:• Give the groups 5-10 minutes.Say: Pick your top issue and brainstorm some strategies that you as an OMK state teamcould implement to support families dealing with your top issue.Do:• Spend about 10 minutes back briefing each group’s top issue and strategiesand list of issues. Give each group an equal amount of time.Say: Each group will out-brief their list of issues and their top issue and list of strategiesto support military families.Chapter 1Page 203rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

What Do Military YouthHave to Say???Slide 1-14: What Do Military Youth Have to Say???Content of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: Quotes from youth cut out of MFRI study Adjustments AmongAdolescents in Families When a Parent is Deployed. Study can be found in the RSG!<strong>Manual</strong> Resource CD (pgs. 14-35).Trainer Tips: Use a couple of quotes from each phase of the deployment cycle. Handout quotes to youth participants or adult participants who will recite the quote. READTHE STUDY BEFORE FACILITATING THIS ACTIVITY.What to Do, What to SayDo:• Hand out copies of the quotes to participants who agree to read one.Number them so you can call a number and they stand up and read thequote.Say: OK, we have discussed some of the issues that we think children and youth faceduring a deployment.Now we are going to hear what some military youth have to say! On your resourceCD is a study from the Military Family Research Institute called AdjustmentsAmong Adolescents in Families When a Parent is Deployed. I highly recommendOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page 21

you take the time to read it. Interviews were done with military youth who havebeen through a deployment.The study identifies many issues and gives strategies for supporting both theremaining parent and the adolescents.So let’s hear what they have to say ...Do:Do:• Hold up a copy of the MFRI study Adjustments Among Adolescents in FamiliesWhen a Parent is Deployed.• Identify each stage of deployment and then ask for the correspondingquotes to be read.Chapter 1Page 223rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Any Questions, Comments,or Thoughts for the <strong>Go</strong>odof the Group?Slide 1-15: Any Questions, Comments, or Thoughts for the <strong>Go</strong>od of the Group?Content of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to SayDo:• Review content of slide with participants.Say: Do you have any questions or comments on what we have covered so far?If you go back to your room tonight and have a thought or question, please writeit down and put it on the parking lot in the morning!Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page 23

Welcome and IntroductionsPre-TestActivity: “Walk This Way”<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>!<strong>Training</strong> AgendaA New Reality: Impact of Global War on TerrorismOperation: Military Kids—An Overview and Framework forImplementationExploring Military CultureEmotional Cycle of Deployment: Mobilization and DeploymentEmotional Cycle of Deployment: Homecoming and ReunionStress and Coping StrategiesImpact of Grief, Loss, and TraumaFostering Resilience in Children and YouthUnderstanding the Influence of the MediaBuilding Community Capacity to Take ActionOperation: Military Kids Next StepsOperation: Military Kids PartnersAdditional Resources and Best PracticesPost-TestFinal Thoughts, Comments, and ClosureChapter 1Page 243rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> MaterialsSupplemental Resources CD<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong><strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> PowerPoint PresentationCaring for Kids After Trauma and Death: A Guide for Parents and ProfessionalsEducators’ Guide to Military Children During DeploymentHot Topics: Reunion—Putting the Pieces Back TogetherHow Communities Can Support Children/Families of Those Serving inthe National Guard and Reserve (Military Child Educational Coalition)How to Prepare Our Children and Stay Involved in Their EducationDuring Deployment (Military Child Educational Coalition)National Council of Family Relations Policy Briefing: Building StrongCommunities for Military FamiliesParents’ Guide to Military Children During DeploymentTalking with Children About War and ViolenceU.S. Army Secondary Education Transition StudyWhat Happened to the World: Helping Children Cope in TurbulentTimes“Tough Topics” Fact SheetsOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page 25

<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>!Participant Pre-/Post-TestName:Date/Location of Workshop:Please circle one: Pre- Post-1. The main purpose of OMK is to provide support to the children of families thatare impacted by the Global War on Terrorism.TrueFalse2. Which one of these is not a major component of the OMK initiative?a. Partnership and joint commitment at the federal, state, and local levelare critical to success.b. Rapid response to the issues is necessary to effect change.c. Program developed must be relevant and comprehensive.d. Youth’s best interests are paramount.3. Awareness and knowledge of the impact of deployment on children isimportant because children of military families have unique issues/needs.TrueFalse4. Understanding military culture is important because:a. You may get deployed someday yourself.b. Military people don’t have feelings.c. Empathy and understanding can assist you in dealing with the uniqueissues of children involved in current military life.5. Which one of these is not a stage of deployment:a. Redeploymentb. Post-deploymentc. Active notificationd. Deploymente. EmploymentChapter 1Page 263rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

6. Which strategy is NOT helpful in preparing children for the deploymentprocess?a. Parents should build their emotional bond with children by spendingquality time with them before leaving.b. Plan future communication and ways to stay in touch while apart.c. Do not tell the child about the deployment in advance in order toreduce the stress and worry that will occur.7. The fourth stage of deployment, called sustainment, generally lasts 12months.TrueFalse8. Citizen Soldiers participating in the National Guard and Army Reserve areconnected with military life and culture.TrueFalse9. Talking about the Global War on Terrorism and violence may increase achild’s fear.TrueFalse10. National Guard and Army Reserve Soldiers always serve the federalgovernment on an emergency basis.TrueFalse11. (Answer on Post-Test only.) What are you going to do with this informationwhen you return to your community?Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page 27

— Answer Key —<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>!Participant Pre-/Post-TestName:Date/Location of Workshop:Please circle one: Pre- Post-1. The main purpose of OMK is to provide support to the children of families thatare impacted by the Global War on Terrorism.TrueFalse2. Which one of these is not a major component of the OMK initiative?a. Partnership and joint commitment at the federal, state, and local levelare critical to success.b. Rapid response to the issues is necessary to effect change.c. Program developed must be relevant and comprehensive.d. Youth’s best interests are paramount.3. Awareness and knowledge of the impact of deployment on children isimportant because children of military families have unique issues/needs.TrueFalse4. Understanding military culture is important because:a. You may get deployed someday yourself.b. Military people don’t have feelings.c. Empathy and understanding can assist you in dealing with the uniqueissues of children involved in current military life.5. Which one of these is not a stage of deployment:a. Redeploymentb. Post-deploymentc. Active notificationd. Deploymente. EmploymentChapter 1Page 283rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

6. Which strategy is NOT helpful in preparing children for the deploymentprocess?a. Parents should build their emotional bond with children by spendingquality time with them before leaving.b. Plan future communication and ways to stay in touch while apart.c. Do not tell the child about the deployment in advance in order toreduce the stress and worry that will occur.7. The fourth stage of deployment, called sustainment, generally lasts 12months.TrueFalse8. Citizen Soldiers participating in the National Guard and Army Reserve areconnected with military life and culture.TrueFalse9. Talking about the Global War on Terrorism and violence may increase achild’s fear.TrueFalse10. National Guard and Army Reserve Soldiers always serve the federalgovernment on an emergency basis.TrueFalse11. (Answer on Post-Test only.) What are you going to do with this informationwhen you return to your community?Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 1Page 29

Chapter Two:A New Reality: Impact of Global Waron TerrorismI. Lesson PlanA. Purpose: This lesson will provide participants with an overview of the GlobalWar on Terrorism’s effects on military children and the unique challenges facedby youth whose parents are in the National Guard and Army Reserve. It willalso introduce participants to the structure of youth programs in the U.S. Army,National Guard, and Army Reserve. The information and tools will contributeto their ability to effectively work with the National Guard at the state andcommunity levels.B. Objectives:1. Provide an overview of the Global War on Terrorism’s effects on children.2. Provide an overview of the structure and youth programs of the U.S.Army, National Guard and Army Reserve.3. Explain the differences between the Active Army and Reserve ComponentStructures.4. Identify the strengths and resources the National Guard has to offerwith regard to OMK.5. Identify strategies for working with the National Guard and Army Reserve.C. Time: 90 minutesD. Preparation/Materials Needed:✪ Laptop with LCD✪ Easels for each table/small group✪ Flip chart paper and markers✪ PowerPoint slides✪ Copies of newspaper articles for each participantII. <strong>Training</strong> Session ContentA. PowerPoint SlidesSlide 2-1: Chapter 2 Introduction SlideSlide 2-2: Impact of the Global War on TerrorismSlide 2-3: Unique Issues for Children/Youth in National Guard andArmy Reserve FamiliesOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page

Slide 2-4: Identified Issues for Children/Youth in National Guard andArmy Reserve FamiliesSlide 2-5: AFAP Issue Paper ActivitySlide 2-6: The Active Army Title SlideSlide 2-7: U.S. Army Component StructuresSlide 2-8: Active Army DemographicsSlide 2-9: Army Installation Management RegionsSlide 2-10: Army National Guard Title SlideSlide 2-11: Overview of National GuardSlide 2-12: Army National GuardSlide 2-13: Army National Guard UnitsSlide 2-14: Air National Guard UnitsSlide 2-15: Strategies for Working with the National GuardSlide 2-16: Army Reserve Title SlideSlide 2-17: Army Reserve OverviewSlide 2-18: Army Reserve Regional Readiness CommandsSlide 2-19: Army Reserve UnitsB. Activity & Directions1. Review slides2. Activity Instruction: Newspaper articles with deployment issuesidentified by Soldiers or family members• Distribute copies of newspaper articles to each participant.• Small groups read articles and discuss ways OMK efforts can addressissues identified by Soldiers and family members.• Ask small groups to identify issues and potential OMK ideas.• Ask recorder to record answers on flip chart paper.• Small group spokesperson will share back after 10 minutes.3. Develop overview of local National Guard, Army Reserve, and ActiveDuty CYS program structure.III. Website ResourcesA. U.S. Army Family and MWR Commandhttp://www.armymwr.comB. Army Community Serviceshttp://www.myarmylifetoo.comC. Reserve Affairshttp://www.defenselink.mil/ra/D. Introduction to the National Guard and History of the National Guard trainingmodules at http://www.gftb.org.E. National Guard Family Programs information at http://www.guardfamily.org.F. National Guard website in your stateG. Army National Guard website at http://www.arng.army.mil.H. Army Reserve Family Programs at http://www.arfp.orgChapter 2Page 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

IV. EvaluationA. Reflection Question1. What is one thing you wish someone told you about working with theArmy, National Guard, and/or Reserve?B. Application Question1. What is one way you can apply this new information in your position?Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page

Chapter 2:A New Reality: Impact of the GlobalWar on TerrorismOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong>Slide 2-1: Chapter 2 IntroductionContent of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide content with participants.Chapter 2Page 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Impact of the Global War on Terrorism• Has changed the face of military service for those in theNational Guard and Army Reserve• Mobilization and deployment at record high levels• Different needs than traditional military families• Primary occupation is not one of “Soldier” and familiesdon’t consider themselves “military families”• Geographically dispersed from others in the samecircumstances (not necessarily located near a militaryinstallation)• Family identity changes from “civilian” to“military” with one letter or phone callSlide 2-2: Impact of the Global War on TerrorismContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: Laptop, LCD, screen, PowerPoint slides, flip chart paper, markersTrainer Tips: Have someone change the slides for you.What to Do, What to Say:Do:• Introduce yourself and the topic.Say: This session reviews the Army Structure and the impact of the Global War onTerrorism on military children and youth.Do:• Review PowerPoint slides.Say: National Guard and Army Reserve operations are different today than they havebeen in the past.Previously, Soldiers trained one weekend a month and two weeks in the summer;now it is expected they will be activated for federal missions every 4 to 5 years for9 to 12 months at a time.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page

Say: When these Soldiers are on Active Duty, their families are eligible for militaryprograms and support. However, they are often not aware or able to accessthe programs and support available to them.They are in need of information and training on these resources.In addition, support that they are eligible for on military installations may not belocated anywhere near their work and home. Consequently, they may not befamiliar with or comfortable operating in this military environment.It is no wonder they do not identify themselves as military families and often feeltheir lives have been turned upside down.Chapter 2Page 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Unique Issues for Children/Youth inNational Guard and Army Reserve Families:• Lack of community awareness of and support for family needs• Lack of educator preparedness to recognize and meet needs ofchildren/youth of deployed members• Possible transition from one school to another• Social/emotional/behavioral reactions may impact youths’ future• Accessibility and affordability of childcare• Availability and affordability of after-school programs and youthactivities; children home alone• Difficulty understanding and dealing with media• Frequently unaware of resources to help parents andchildren cope• Deployment cycle—disrupts family before,during, and after...and is repeatedSlide 2-3: Unique Issues for Children/Youth in National Guard andArmy Reserve FamiliesContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.Say: This slide describes the situation that National Guard and Army Reserve familiesmay find themselves in now.Prior to the Global War on Terrorism, very few Army Family or Child & YouthPrograms existed specifically designed to support National Guard and Army Reservefamilies, other than what was already available on an installation.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page

Say: Because of the large numbers of National Guard and Army Reserve Soldiers calledto fight the Global War on Terrorism, the Army had to develop new outreachprograms designed to meet the specific needs of these families…programs in theirown neighborhoods.The Army realized that these families’ normal support systems could not providethem with the information or support to meet their new needs. Their neighbors,teachers, friends, and other community members were often unaware that theirfamily member was deployed or of the impact the War was having on them.Chapter 2Page 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Identified Issues for Children/Youth inNational Guard and Army Reserve Families:• Geographically dispersed families and lack of connection withother youth and families in similar situation• Child separation/anxiety issues regarding safety of deployed parent• Deployed parent absent for significant events• Less parental involvement from parent at home• Limited opportunities for youth to attend extracurricular activities• Teens having increased care of home and younger siblings• Behavioral changes, peer pressure, lower self-esteem• Communication with deployed parent• Need to live with extended family• Changes in financial resourcesSlide 2-4: Identified Issues for Children/Youth in National Guard andArmy Reserve FamiliesContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.Say: This slide outlines some of the issues that National Guard and Army Reservechildren and youth face as a result of their family member being deployed tofight the Global War on Terrorism.These children and youth are strong and resilient. They take on roles andresponsibilities to keep their families functioning that may have been performedby the absent parent. They miss their deployed parents, especially during birthdays,holidays, and other special events. They may be exposed to new circumstances,Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page

e.g., living with a relative or lower family income. They may be the only one in theirschool or community with a deployed family member and thus feel alone.They need our help. And, so do their deployed parents, who will be better ableto concentrate on their military mission if they know that their families are beingtaken care of.Do:• Before moving on: Ask participants if there are any other issues that may notbe identified here that impact these youth.Chapter 2Page 103rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

How can OMK state teams utilize theArmy Family Action Plan (AFAP) processto address unique issues facingchildren/youth in National Guardand Army Reserve families?Slide 2-5: How can OMK state teams utilize the Army Family ActionPlan (AFAP) process to address unique issues facing children/youth in National Guard and Army Reserve families?Materials Needed: Sample AFAP Issue papers for participants, AFAP Issue papertemplatesTrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Hand out sample AFAP Issue paper.Say: Ask participants if anyone is familiar with the Army Family Action Plan (AFAP) orGuard Family Action Plan (GFAP) process.Ask someone who is familiar with AFAP process to explain how an AFAP Issue isdeveloped.Ask participants to utilize the AFAP Issue paper template to define the issue, developthe scope (impact on youth), and develop 2-3 recommendations (ways OMK canOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page 11

address issue).Ask group(s) to be prepared to out brief their issue.Was the AFAP activity helpful in developing OMK strategies for your state? If so,how?Chapter 2Page 123rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

The Active ArmySlide 2-6: The Active ArmyContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page 13

Army Component StructuresActive Component*RegionsGeographically Dispersed**InstallationsReserve ComponentNational GuardStatesArmy ReserveRegions* Base Operations organization, not units** Assigned away from military installations, e.g., Army Recruiters, ROTC InstructorsSlide 2-7: The Army Component StructureContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.Say: The Army is composed of two components: the Active Component, often referredto as “Active Duty,” and the Reserve Component.The Active Component is comprised of Soldiers whose full-time career is soldiering.They are generally assigned to units that are stationed on installations locatedaround the world. The Army divides the world into seven geographic regions formanagement purposes.Some Active Duty Soldiers, e.g., Army Recruiters, ROTC, and Inprocessing personnel,are assigned to locations that are geographically dispersed away from installations.Say: These Soldiers’ place of work is found in malls, schools, Inprocessing Centers, andChapter 2Page 143rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

universities.The OMK focus is on both the Active and Reserve Components.For individuals in the National Guard or Army Reserve, their military duty is apart-time function. They hold regular full-time jobs in their communities.The National Guard is structured in a state configuration through the Joint ForcesHeadquarters. They are assigned to and organized by state. They are activated bythe state governor to perform state missions, e.g., helping with natural disasters,riots, fires, etc. They can be federalized by the President to serve National missions,e.g., the Global War on Terrorism.Army Reserve Soldiers are organized by mission in geographic regions. The ArmyReserve Regions and the Active Duty Regions are not the same. Army ReserveSoldiers have often served in the Army and stayed in the Reserves when they gotout. They have Army experience and are often familiar with the military culture.They are activated by the President to perform Federal missions.Do:• At the end of this slide, ask the audience if they have any questions aboutthe structure of the Active Component.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page 15

Active Army Demographics• 483,452 Soldiers• 54% married• 10% of married Soldiers are dual military• 8% are single parents• 457,428 children• Over 500,000 retirees• Undergoing transformationSlide 2-8: Active Army DemographicsContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.Say: Active Duty Soldiers are stationed worldwide to perform National Security and otherFederal missions. Army spouses and retirees are an excellent source of volunteers toassist with OMK efforts.Chapter 2Page 163rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Army Installation Management CommandRegionsSlide 2-9: Army Installment Management RegionsContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.Say: The Army divides the world into the seven Active Component Regions. The slide showswhich installations are included in each region, except for those overseas. The RegionHeadquarters are noted by stars. The seven regions and their headquarters are:– Northeast Region—Ft. Monroe, VA– Southeast Region—Ft. McPherson, GA– West Region—San Antonio, TX– Pacific Region—Ft. Shafter, HI– European Region—Heidelberg, GE– Korean Region—Yongsan, KoreaSome of this structure may change as the Army transforms over the next few years.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page 17

Army National GuardSlide 2-10: Army National GuardContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do: • Show opening slide.Say: What pictures come to mind when you think about the National Guard?Chapter 2Page 183rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Overview of National Guard• Army National Guard is one branch of the total U.S. Army• ARNG is composed of reservists—civilians who serve theircountry on a part-time basis• Each state and the federal government control theARNG, depending on the circumstances• In peacetime, governors command the Guard Forcesthrough the Adjutant General• During wartime, the President of the United States canactivate the National Guard• Where federalized, Guard units are led by theCommander-in-Chief of the theatre in whichthey are operatingSlide 2-11: Overview of National GuardContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.Say: <strong>Go</strong>vernors can call the Guard into action during local or statewide emergenciessuch as storms, drought, and civil disturbances.Examples of National Guard units being federalized to support operations wouldbe in Bosnia, Afghanistan, and Iraq.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page 19

Army National Guard• 350,000 Soldiers• 33% of Army’s totalstrength• State and Federal mission• State command• Primarily combat andcombat service supportunitsNational GuardAir National Guard• 106,000 Airmen• 19% of Air Force’s totalstrength• State and Federal mission• State command• Primarily flying missionsand expeditionarycombat supportSlide 2-12: National GuardContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.Say: The National Guard is a joint force made up of the Army National Guard and AirNational Guard. This slide identifies the number of ARNG and ANG Soldiers andAirmen. It also provides the percentage of Army Total Strength for both branchesof the National Guard.Both the ARNG and the ANG maintain a state and federal mission and have a statecommand oversight.– Combat and Combat Service Support Soldiers possess occupational specialtiessuch as medical personnel and engineers. They support missions that mayrequire them to be deployed for up to two years.Chapter 2Page 203rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Say: – ANG personnel primarily support flying missions and expeditionary combatsupport. These missions may be frequent and are typically for periods of 3 to 6months.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page 21

Army National Guard Units350,000 SoldiersSlide 2-13: Army National Guard UnitsContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.Chapter 2Page 223rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Air National GuardThe Air NationalGuard connects everypolice and fire stationto the Pentagon and everystate house to the White House.177 ANG Community Based Locations41 Community Based Fighter LocationsSlide 2-14: Air National Guard UnitsContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page 23

Strategies for Working with theNational Guard• Schedule introductory meeting with State YouthCoordinator, State Family Program Director, and WingCoordinators• Inform all potential OMK participants of program services• Learn about issues faced by youth of deployed parents• Work with State Family Programs personnel to enlistCommand support• Invite the State Youth Coordinator to participateon the OMK TeamSlide 2-15: Strategies for Working with the National GuardContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.Say: States are anxious to be a part of OMK and will be a great resource to theState Team.Discuss what resources the Guard can bring to OMK and what resources you canshare with the Guard.Currently there is at least one FAC in each state/territory. Make sure they have yourinformation to share with families. They are the primary source of informationregarding services available to National Guard families.Refer to staff listing.Chapter 2Page 243rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Army ReserveSlide 2-16: Army ReserveContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.• Share purpose and objective of this portion of the chapter.Say: The purpose of this portion of Chapter 2 is to provide an overview of the ArmyReserve and the Army Reserve Child & Youth Services program.We will present an overview of the Army Reserve and explain how the Army Reservesupports OMK.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page 25

• 317,495 SoldiersArmy Reserve Overview• Over 1,923 units throughout U.S. and territories• Federal Mission• Regional commands (13 and 1 ARCOM)• Primarily combat support and combat service supportunitsSlide 2-17: Army Reserve OverviewContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: It is important to note that the number of Soldiers, units, and regionalcommands can and will change. The numbers presented on these slides are current asof August 2005.What to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide content with participants.• Emphasize key points of discussion as follows:Say: Combat Support and Combat Service Support Units do jobs like transportation,military police, civil affairs, engineering, administrative functions, etc.To meet the needs of today’s Army, the Army Reserve is undergoing transformation.Although this will change the structure of the Army Reserve, it does not change theneeds of Army Reserve families within our communities.Chapter 2Page 263rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Army ReserveRegional Readiness Commands96th RRCSalt Lake City, UT88th RRCFort Snelling, MN77th RRCFlushing, NY70th RRCSeattle, WA88th RSGFort Ben Harrison,IN94th RRCFort Devens, MA63rd RRCLos Alamitos,CA99th RRCOakesdale, PA81st RSGFort Jackson, SC7th ARCOM9th RRC89th RRCWichita, KS90th RSGSan Antonia, TX90th RRCN. Little Rock, AR 81st RRCBirmingham, AL65th RRCSan Juan, PRSlide 2-18: Army Reserve Regional Readiness CommandsContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: N/ATrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.Say: There are eleven Regional Readiness Commands or RRCs. The 9th RRC in Hawaiiand the 7th ARCOM in Germany fall under the command and control of the UnitedStates Army Pacific and the United States Army Europe commands, respectively.– Each RRCs area of responsibility, with the exception of the 65th RRC in PuertoRico, corresponds with the standard federal region boundaries used by mostother federal agencies. Probably the best known of these is the Federal EmergencyManagement Agency (FEMA).– Three RRCs have large concentrations of Soldiers and therefore have RegionalSupport Groups (RSGs) to assist in providing support to subordinate units.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page 27

Say:They are shown in red:81st RSG in Fort Jackson, South Carolina88th RSG in Fort Ben Harrison, Indiana90th RSG in San Antonio, Texas– Stability through power projection and an overseas presence:Samoa9th RRC under PACOM—28 units—Hawaii, Alaska, Guam, and American65th RRC—26 units7th ARCOM under EUCOM—25 unitsChapter 2Page 283rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Army Reserve Units317,495 SoldiersSlide 2-19: Army Reserve UnitsContent of this slide adapted from: RSG <strong>Manual</strong> v.1Materials Needed: Trainer and participant manualsPowerPoint slidesTrainer Tips: N/AWhat to Do, What to Say:Do:• Review slide.• Emphasize key points of discussion as follows:Say: The majority of the Army Reserve units are located in the eastern half of the UnitedStates. However, this is not representative of the location of Army Reserve families.It is not uncommon for Army Reserve Soldiers to travel a great distance to their unit.Keep in mind that a Soldier might work at a Reserve Center in one state, but residewith his or her family in a different state.Also, most of the families do not have access to programs and services that areusually available on or near military installations, therefore creating the need forgroups like this to collaborate on community-based initiatives.Operation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>3rd EditionChapter 2Page 29

Chapter Three:Introducing Operation: Military Kids and the OMKImplementation FrameworkI. Lesson PlanA. Purpose: Define Operation: Military Kids Outreach Initiative and explainthe OMK Implementation Framework and oversight responsibilities of thedifferent levels of that framework.B. Objectives:1. What is Operation: Military Kids?2. Who are the Core OMK Partners?3. Define and discuss “Building Community Capacity.”4. What/who are the Management Groups of OMK and what are theiroversight responsibilities?5. Define three program components of Operation: Military Kids.C. Time: 45–60 minutesD. Preparation/Materials Needed:✪ Flip chart paper and markers✪ Participant Handouts—OMK Overview and OMK Implementation Framework✪ Participant Handouts—Speak Out for Military Kids and Hero Packs✪ List of Deployment IssuesII. <strong>Training</strong> Session ContentA. PowerPoint SlidesOperation: Military Kids OverviewSlide 3-1: Introduction to Operation: Military Kids and OMKImplementation FrameworkSlide 3-2: What is Operation: Military Kids?Slide 3-3: Quote From General Helmly—Change in the Army ReserveSlide 3-4: 4-H/Army Youth Development Project—Why Expand?Slide 3-5: Operation: Military Kids—The ConceptSlide 3-6: <strong>Go</strong>al and Objectives of Operation: Military KidsSlide 3-7: Guiding Principles of Operation: Military KidsSlide 3-8: Operation: Military Kids DocumentationChapter 3Page 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Slide 3-9: Operation: Military Kids Core PartnersSlide 3-10: States Receiving Operation: Military Kids GrantsSlide 3-11: What is Building Community Capacity?Slide 3-12: Definition of Building Community CapacityOperation: Military Kids Implementation FrameworkSlide 3-13: Introduction to the OMK Implementation FrameworkSlide 3-14: 4-H/Army Youth Development Project ChartSlide 3-15: What is the Army Youth Development Project?Slide 3-16: OMK Oversight Responsibilities of the 4-H/Army YDPSlide 3-17: OMK Management TeamSlide 3-18: OMK Management Team Oversight ResponsibilitiesSlide 3-19: OMK Program Marketing and Resource Materials Provided byOMK Management TeamSlide 3-20: OMK Partnership Advisory GroupSlide 3-21: Oversight Responsibilities for OMK Advisory GroupSlide 3-22: OMK State TeamsSlide 3-23: OMK Community Volunteer PartnersSlide 3-24: OMK State Team Roles and ResponsibilitiesSlide 3-25: OMK Management FrameworkSlide 3-26: OMK Statewide Support NetworksSlide 3-27: OMK Local Community Support NetworksSlide 3-28: OMK Implementation FrameworkSlide 3-29: OMK Keys to ImplementationSlide 3-30: Core OMK ProgramsSlide 3-31: <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> ContentSlide 3-32: <strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! Chapter FrameworkSlide 3-33: Speak Out for Military Kids (SOMK)Slide 3-34: Speak Out for Military Kids: OutcomesSlide 3-35: Speak Out for Military Kids: ResourcesSlide 3-36: Hero Pack InitiativeSlide 3-37: What is in a Hero Pack?Slide 3-38: Hero Pack ImplementationSlide 3-39: Mobile Technology LabsSlide 3-40: Mobile Technology Labs Hardware/SoftwareSlide 3-41: Mobile Technology Labs OMK State Team OversightB. Activity & Directions1. Operation: Military Kids Overview Brief• Brief large group on OMK overview.2. Building Community Capacity Discussion• Break into small groups.• Ask participants to respond to the question, “What do we mean by‘Building Community Capacity?’”• Give one issue to each group. Each group must develop a strategy onhow to build capacity on the issue they were given. They will need toChapter 3Page 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

include needed resources, training requirements, etc.• Have the smaller groups brief back to entire group.3. Operation: Military Kids Implementation Framework Brief• In the large group, go through the OMK Implementation FrameworkBrief.III. Must-Read Background MaterialA. Operation: Military Kids Web site—http://www.operationmilitarykids.orgB. Overview of Army Child & Youth ServicesC. Overview of National 4-H ProgramD. Boys & Girls Clubs of America DescriptionE. Operation: Proud Partner (OPP) Sites (Boys & Girls Clubs)F. American Legion OMK Fact SheetG. Military Child Education Coalition (MCEC) DescriptionH. Speak Out for Military Kids (SOMK) Program OverviewI. Hero Pack Project OverviewIV. EvaluationA. Reflection Questions1. What did you learn in this discussion about Operation: Military Kidsthat you didn’t know before?2. Does this information change your perception/purpose of your role onyour State OMK Team?3. What strengths do you and your organization bring to the Operation:Military Kids Implementation Framework?B. Application Questions1. How are we going to work together as a State Operation: Military KidsTeam?2. Do any of us know someone/another organization that we need to askto be a part of this team?3. How are we as a team going to ensure we create the links and supportsystems to establish the Community Capacity necessary to effectivelyaddress the issues children and youth are facing in our state?Chapter 3Page 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>

Introduction to Operation: MilitaryKids and OMK ImplementationFrameworkSlide 3-1: Introduction to Operation: Military Kids and OMKImplementation FrameworkContent of this slide adapted from: N/AMaterials Needed: Copies of RSG! Read-Ahead MaterialsTrainer Tips: If your group was given the RSG! Read-Ahead Materials, you can treatmuch of the Implementation Framework as review, therefore not spending as muchtime on it.What to Do, What to Say:Say: In the next 30 minutes or so we are going to introduce the concept of OMK anddiscuss the framework that will help you operationalize OMK in your state.Chapter 3Page 3rd EditionOperation: Military Kids<strong>Ready</strong>, <strong>Set</strong>, <strong>Go</strong>! <strong>Training</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>