by Milton MacKaye - The Saturday Evening Post

by Milton MacKaye - The Saturday Evening Post

by Milton MacKaye - The Saturday Evening Post

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

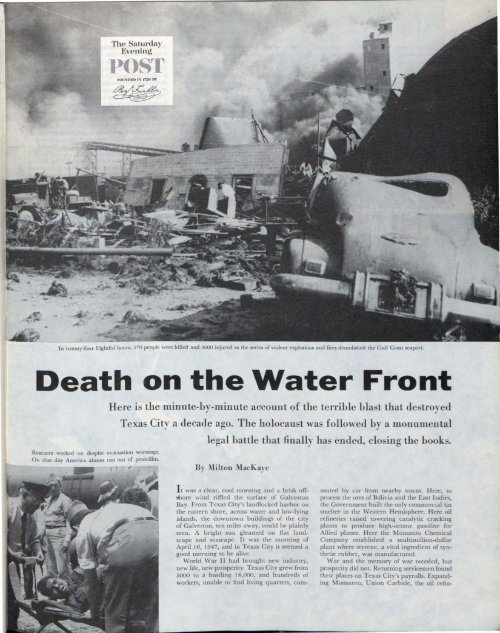

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Saturday</strong><strong>Evening</strong>POSTFOUNDED IN 1728 BYIn twenty-four frightful hours, 570 people were killed and 3000 injured as the series of violent explosions and fires demolished the Gulf Coast seaport.Death on the Water FrontRescuers worked on despite evacuation warnings.On that day America almost ran out of penicillin.Here is the minute-<strong>by</strong>-minute account of the terrible blast that destroyedTexas City a decade ago. <strong>The</strong> holocaust was followed <strong>by</strong> a monumentallegal battle that finally has ended, closing the books.By <strong>Milton</strong> <strong>MacKaye</strong>It was a clear, cool morning and a brisk offshorewind riffled the surface of GalvestonBay. From Texas City's landlocked harbor onthe eastern shore, across water and low-lyingislands, the downtown buildings of the cityof Galveston, ten miles away, could be plainlyseen. A bright sun gleamed on flat landscapeand seascape. It was the morning ofApril 16, 1947, and in Texas City it seemed agood morning to be alive.World War II had brought new industry,new life, new prosperity. Texas City grew from5000 to a bustling 18,000, and hundreds ofworkers, unable to find living quarters, corn-muted <strong>by</strong> car from near<strong>by</strong> towns. Here, toprocess the ores of Bolivia and the East Indies,the Government built the only commercial tinsmelter in the Western Hemisphere. Here oilrefineries raised towering catalytic crackingplants to produce high-octane gasoline forAllied planes. Here the Monsanto ChemicalCompany established a multimillion-dollarplant where styrene, a vital ingredient of syntheticrubber, was manufactured.War and the memory of war receded, butprosperity did not. Returning servicemen foundtheir places on Texas City's payrolls. ExpandingMonsanto, Union Carbide, the oil refin-

20cries, recruited young scientific talent from thenation's top universities and technical schools.It was a young men's town and the wives theybrought with them were young too. <strong>The</strong> TexasCity Terminal Railway Company, next doorto Monsanto on the water front, ownedwharves and warehouses and diesel switchengines and tracks. <strong>The</strong> Terminal facilitiesprovided jobs for stevedores and for Negroand Mexican unskilled labor.Many of the laborers and their familieslived near the wharves and the Monsantoreservation in flimsy, crowded shacks. TexasCity was ahead in many things, but way behindin housing.Almost everyone who wanted to work wasworking on April sixteenth. <strong>The</strong> day shiftwent on duty at eight. Long before that, aprocession of battered jalopies—new cars werehard to get in 1947—began to cross the longcauseway which links island Galveston withthe mainland. At the Bon Ton Café on ThirdStreet, seventeen-year-old Alfred Gersonfed early Texas City breakfasters, while heawaited with impatience the appearance ofhis parents, the café's proprietors, from theframe apartment house across the street. <strong>The</strong>Gersons were Houston people who had beenthere for only a few months, but they wereprospering and they liked Texas City.Henry J. (Mike) Mikeska was president ofthe Texas City Terminal, and had contributedgreatly to the building up of Texas Cityas a deep-water port. An engineer graduate ofTexas A. & M., sixty-year-old Mikeska tookpart in almost every civic enterprise, had beenpresident of the school board for sixteen yearsand was father-at-large for the town.Mike and his wife, Martha Jane, had spentthe weekend at his boyhood home in NorthTexas and had intended to stay longer. Minorlitigation brought him back. Martha Jane usuallydrove Mike to the office. But that Wednesdaymorning she stayed at the house to transplantviolets they had dug up at the old homeplace. Mike left at eight o'clock and there wastrouble at the Terminal soon after he arrived.<strong>The</strong> Grandcamp, a Liberty ship flying theFrench flag, captained and crewed <strong>by</strong> Frenchmen,caught fire. It had been in Texas Cityfor five days loading ammonium nitrate fertilizerfor the fields of France.Three vessels were at the pier that morning.<strong>The</strong> Seatrain dock with its high crane wasempty. <strong>The</strong> S.S. Grandcamp lay in Pier 0.<strong>The</strong> American vessels Wilson B. Keene andHigh Flyer were in the slip beyond. <strong>The</strong> WilsonB. Keene was waiting to load flour forFrance. <strong>The</strong> High Flyer had already packedaway 900 tons of fertilizer and knocked-downLast rites were administered at a temporary morgue set up near the explosion scene. <strong>The</strong> dead left behind 844 dependents—many homeless and utterly without resources.

oxcars for equipment-starved French railroads.Henry J. Baumgartner was a big broadshoulderedman in his middle forties, father offour children and chief of the Volunteer FireDepartment. He liked strenuous dancing and astrenuous domino game, and was the life of theparty at the firemen's monthly get-togethers.Actually, Baumgartner was a purchasingagent for Texas Terminal, but was expected toleave his assignment whenever a fire occurred;it was part of his job. Towns which depend onchemical industries and oil refineries for a payrollhave no illusions; there is always hazard.And Baumgartner and his colleagues were welltrainedand experienced men. <strong>The</strong>y knew howto fight ship fires, oil, benzol and propane fires.But there was no general current knowledgethat ammonium nitrate would explode.Even today, more than ten years later, thereis no trustworthy report on how the Grandcampfire began. At eight o'clock the whistlesblew and the longshoremen and warehousemenwent to work. At the Grandcamp it tookabout ten minutes to lift the covers from theNo. 4 hatch. Some time after that, longshoremennoticed (Continued on Page 95)Above: <strong>The</strong> SS Grandcamp burning. Her cargo—ammonium nitrate—was not yetknown to be a violent explosive. Minutes after this picture was taken, the ship erupted.W. H. Sandberg directed dockside operations afterescaping death when the Grandcamp blew up.For days after the blast, stricken survivors helpedidentify the dead. <strong>The</strong> picture below shows a youngmother who had just found her husband's body.Above: <strong>The</strong> wreck of the Wilson B. Keene, moored alongside the High Flyer, lieswhere she was cut in half <strong>by</strong> the second of the two major explosions on the water front.After the Supreme Court ruled against aidto disaster victims, Representative Thompsonintroduced a bill to compensate survivors<strong>by</strong> a special act of Congress. It passed.

October 26, 195795Death on the Water Front(Continued from Page 21)there was smoke in the hold. Crew memberswent below deck and searched forthe source of the smoke and could notfind it. <strong>The</strong> fire grew and air in the holdbecame acrid and stifling. Longshoremenleft the job, but waited at the pier end towatch the fire fighting.Water introduced into a burning shipputs out fires, but damages cargo. Fewskippers who want to sail again endorsethe damaging of cargo except in direemergencies. Capt. Charles de Guillebonordered the hatches closed, and thenturned live steam into the hold. This, supplantingoxygen, was supposed to smotherthe fire. It didn't. <strong>The</strong> captain finally orderedthe crew to abandon ship and at8:33 the fire alarm was sounded. MikeMikeska and W. H. (Swede) Sandberg,vice president of Terminal, hustled to thescene. So did Henry Baumgartner and hishastily assembled firemen. Dick Wilson,one of them, had worked the night shiftat the docks and was just leaving the yardwhen the alarm sounded. He was dutyboundto stay. Chief Baumgartner peeredat him and said, "Dick, you look tired.Go on home." Dick did, and that kindlyorder saved his life.News of the fire had spread in TexasCity before the alarm was sounded. BeforeTerminal officials could close theirgates 200 or 300 people had gathered nearthe wharf area. <strong>The</strong> town's schools wereovercrowded and the upper grades werebeing taught in double shifts; some of thesight-seers were youngsters free for themorning. Many who came as spectatorsmade themselves useful uncoiling andstretching hose and helping the fire fighters.Texas City's brand-new $14,000 fireengine made its first run since being commissioned.About 450 employees were on duty atMonsanto at eight A.M. In addition, therewere 123 employees of outside contractorswho were doing construction work at theplant. Between coffee in the commissaryand the excitement of fire in the adjoiningquay, a good many of them were slow ingoing to their offices and control posts,and even slower in settling down to thedaily grind. Ralph A. Ford, carpenterforeman, finished his coffee and said,"Smoke's thinning. <strong>The</strong> fire's about out.Let's go to work." Back at his office hebegan making out time slips for the day.Joe Mitchell, Negro porter, started on hismail-distribution rounds, saw Dr. CharlesComstock striding toward the scene of thefire. Comstock, in his middle thirties, aPh.D. from Yale, was technical directorof the Texas division and one of Monsanto'smost brilliant scientific minds.Back at the Terminal, both Mikeskaand Collis Suderman, representative ofthe stevedoring company which was loadingthe Grandcamp, had requested thedispatch of tugs from Galveston; if thefire got out of control, the Grandcampcould be towed away from the wharves tothe open water. At 9:07, Swede Sandberg,concerned with the nonappearance of thetugs, was talking to Suderman some fiftyto seventy-five feet astern of the Grandcamp."Why don't you go out to the end ofthe T-head?" asked Suderman. "You'llprobably see them coming.""Gentlemen," said Sandberg in subsequentofficial testimony, "had I listenedto him and gone out to the T-head, Iwouldn't be here testifying this morning."Instead, he left the dock and started towardhis office to telephone Galveston.On the way he met Mikeska, who, aftertouring other docks, was on his way backto the burning ship. Mikeska gave someroutine instructions, and a few minuteslater Sandberg was back at his desk. Hehad just hung up the telephone when hisroof fell in.For Henry G. Dalehite and his wife,the morning of April sixteenth started tooearly. It was two A.M. when the alarmclock jangled insistently in their pleasanthouse on Causeway Road, Galveston.Elizabeth Dalehite automatically reachedover and stilled the clamor. Twenty-fiveyears married to a shipping man, she wasa merry, plump woman accustomed toirregular schedules and the capricious demandsof boats. Captain Dalehite wasnot only a pilot himself; he operated aservice to incoming ships and had fiveother pilots in his employ.From her honeymoon days, Mrs. Dalehitehad functioned as her husband'schauffeur, secretary and ex-officio partner.It was Henry's job to send pilotspromptly, on radio request, to all portsalong the curving Gulf Coast. But for tendays a telephone strike had been inprogress, and as a result he and his wifehad traveled thousands of miles to keepin touch with his men. While Henry still1 •2 %/I ‘11° .• .1(• ea, T. • , II •I 11 . •■•"Where were you on that last play, Ferguson?"TIM SATURDAY EVENING POST

SORE THROAT?AntibioticCandettesgive immediatesoothing relief!CANDETTES work 2 ways:1 Double Antibiotic action...fightsgerms! Not just one—but two safe,proven antibiotics kill many irritation-causingthroat germs, on contact!2 Anesthetic action...relieves soreness!A safe and effective anestheticacts instantly to relieve soreness ofinflamed membranes.Not an ordinary cough drop — delicious,orange-flavored Candettesare a proven medication! Get themat your drug store.00 Vow0 Guaranteed <strong>by</strong>-NGood HousekeepingCandettesBy the World's Largest Producer of AntibioticsGUAwith REMOVABLE CUTTER for Easy CleaningWorld's most sanitary can opener!Opens all cansl Removable magnet!In" Copper Touch' ®, Chromeor gay colors. Wonderful gift!FEET HURT?Foot, Leg Pains Often Due To Weak ArchIf yours is a foot arch weakness (7 in 10 haveit), the way to make shortwork of that pain is withDr. Scholl's Arch Supportsand exercise.Cost as little as$1.50 a pair. Atselected Shoe,Dept. Stores andDr. Scholl's FootComfort' Shops.slept, Elizabeth tried the telephone again.At Corpus Christi, 225 miles south, aship waited for a pilot; at Baytown, 35miles north, a pilot waited for an assignment.A sleepy stand-<strong>by</strong> operator said theBaytown call was "not essential."<strong>The</strong> Dalehites left home at 2:15. AtBaytown they picked up the pilot; heagreed to fly to Corpus Christi and theycarried him to Houston airport. <strong>The</strong> pinkof dawn now began to seep into the Texassky, and Elizabeth's arms wearied at thewheel. <strong>The</strong>re were fifty-odd miles still togo. <strong>The</strong> captain wanted to call at TexasCity to find out when the next Seatrainwas due to dock.A few minutes after nine, Elizabethparked in the shadow of the Terminalbuildings. About a block away, she andher husband saw the Grandcamp burning.Neither spoke; a pier fire was no noveltyto either. Captain Dalehite left thecar, and about midway of the dock methis old friend, Suderman. Dalehite motionedto his wife to come and join them.She shook her head. She had picked up asmall figure of the Virgin Mary whichaccompanied her on all her trips; shehad already begun to say her morningprayers.It was 9:12. Suddenly, spinning balls offire shot skyward and the Grandcampexploded. <strong>The</strong> result was one of the mostfearful disasters in American history,greater in its loss of life than the celebratedSan Francisco earthquake andfire. Some 570 people were killed andmore than 3000 injured. Property damagehas been estimated at more than $50,-000,000.Elizabeth Dalehite heard nothing. <strong>The</strong>doors of her car were jerked open <strong>by</strong> suctionand she was flung across the roadand into a deep ditch; a Mexican womanblown from a near<strong>by</strong> shack fell atop herand grappled with her in panic. Mrs.Dalehite pulled herself free and was blownto the ground <strong>by</strong> a second explosion.Now she saw rolling clouds of smoke,great banks of fire which, she said later,looked like a "vision of hell." She roseagain and, toward the harbor, the smokemomentarily parted. <strong>The</strong> dock where herhusband had stood and beckoned to herhad vanished.Out of the Texas City disaster grewmassive litigation of real historic interest.Mrs. Dalehite's claim for compensationfor the death of her husband was chosen<strong>by</strong> a committee of lawyers to serve as atest case against the United States Government.It was before Federal tribunalsfor six years and finally went to the SupremeCourt. But of that, more later.It is impossible to estimate the force ofthe Grandcamp explosion, but it is difficultto exaggerate it. Terminal buildingsceased to exist. Monsanto's warehouse—a steel-and-brick structure—was flattened.<strong>The</strong> main power plant was similarlycrushed, and, as the blast fanned out,walls of manufacturing buildings fell, partitionsshredded, pipelines carrying flammableliquids were torn apart. Two sightseeinglight planes, 1500 feet above theGrandcamp, were blown out of the air,with the loss of four lives. Windows inGalveston and Freeport were shattered;the explosion was felt in Palestine, Texas,200 miles away.Edgar M. Queeny, Monsanto's chairmanof the board, flew to the scene of thedisaster that same day. Queeny, in a movingand eloquent public letter, estimatedthat the impact was that of 250 five-tonblockbuster bombs exploding simultaneously.Because the atomic bombs atHiroshima and Nagasaki were explodedhigh in the air. he thought it possible thatsheer blast in those unhappy cities wasless severe than that suffered in the immediateneighborhood of the Grandcamp.On the Monsanto reservation 227 personswere killed. Employees of independentconstruction contractors were in theareas of greatest exposure; the ratio ofdeath and severe injury was greater thanMonsanto's own. Of 123 on the grounds,82 died; 145 Monsanto employees werekilled and more than 200 required hospitalization.Queeny's official report explainedwhy:"A huge wave, rushing in from the basinwhere the ship had rested, inundatedthe area, while the explosion's heat ignitedthe benzol, propane and ethyl benzenepouring out of the ruptured pipesand storage tanks. Savage and cruel fires,feeding on these flammable liquids,scalded those who had survived the blastand were fleeing to safety; they crematedthose who had fallen, and melted andtwisted steel supports and girders."Many died quickly and mercifully. Oneof these was Lucille Ward, beautiful sec-• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •In OctoberBy Louise McNeillCrow call and leaf fallAnd spider spin your yarn,Wheat field turn and sumacburnAnd sheep come home tobarn.Wild geese cry and wingedseed flyAnd frost fern mark thepane,Pods turn brown andshatter downAnd summer die again.But love prevail, nor fade,nor fail,Nor like the sun depart;With us abide this autumntide.Like April in the heart.• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •retary of the plant manager, H. K. (Griz)Eckert. Eckert himself walked out of hisoffice under his own steam, but ultimatelyended up in a hospital, where, in a hazardousoperation, fragments of glass wereremoved from his brain. Robert Morris,assistant manager, was riding in a companyjeep which overturned. He washurled high in the air and saved from fierydeath <strong>by</strong> the wall of water which coveredhim. This was the same fifteen-foot wavewhich dealt cruelly with others, drowningstunned and injured people in pits andpools and serving as a carrier for oil andflames.Death cut almost a clean sweep throughthe rest of Monsanto's executive and technicalforce. <strong>The</strong>se men perished: DoctorComstock; B. F. Merriam, chief plant engineer,a onetime college diving championat Harvard; R. E. Boudinot, productionmanager; R. D. Sutherland, safetyengineer; F. A. Ruecker, chief powerplantengineer; and twenty-two of twentyfouryoung and promising chemists whowere supervising production in differentdepartments. Most of them left widowsand small children.Indeed, hundreds were widowed andorphaned that morning. Eight men diedwhen a flatcar on a railroad siding waslifted like a jackstraw and dropped onthem. Four stalwart brothers in theirearly twenties—Arthur, Clarence, JohnTHE SATURDAY EVENING POSTand William Hattenbach—stevedores all,died together. Hollie 0. Youngman andhis wife were decapitated in their movingautomobile when a 100-pound piece ofmetal hurtled through the windshield.Bales of cotton and balls of sisal twinewhich had been aboard the Grandcampburned in the salt meadows, and, in thesemidarkness, staggering and crawlingfigures began to emerge from the holocaust.<strong>The</strong>re were others, naked, shoeless,coal-black, who ran in circles and fell androse to run again. A small boy walkedcarefully down Dock Street; there was ahole in his side, and, stooping, he held hisvital organs captive with his hands. For afew stunned moments after the explosionit had seemed as though the world wasasleep. Now the awakened wails of theinjured and the lost, the rushing roar ofgasoline and crude oil set ablaze, broughtbattered humanity back to its senses andTexas City to a knowledge of its ownagony.Twenty-seven members of the fire department,including Chief Baumgartnerand Assistant Chief J. M. Braddy, diedwhen the Grandcamp disintegrated. Onlyfour bodies were identified. Thirty-threeof the forty-two men and officers of theGrandcamp lost their lives; they hadabandoned ship, but remained on thedock. Captain de Guillebon died at hispost. So did Mike Mikeska. His wife,Martha Jane, never left her back yard thatday ; frightened, despairing wives came toher for comfort. She was sure there wasnone for her. "I knew," she-said later,"that if there was trouble at the Terminal,Mike would be in the middle of it.Where else would anyone expect him tobe?"Almost every house within a mile ofthe explosion either collapsed or was sobadly damaged as to be a total loss. In theTexas City schools, glass fragments showeredchildren and teachers; concussioncollapsed partitions and crumbled walls,but—almost miraculously—there were nofatalities. In the business district, flyingmissiles tore holes in buildings, roofsgroaned and fell, plate-glass windowswere pulverized.At the Bon Ton Cafe, Al Gerson threwhimself under a counter as the roof fell.When he struggled up through darknessand dust, he heard his mother crying forhelp outside the front door. She and hisfather had been buried <strong>by</strong> the collapse ofthe restaurant portico. His father wasdead, but a few moments later Al discoveredhis mother when he saw an eloquentfinger emerge from the debris. With thehelp of another man, he unearthed her,carried her on a plank to an ownerlesslaundry truck and rushed her to Galveston.She was hospitalized for manymonths.For a time a kind of shell-shocked madnessseized the town. Streaming down onthe business district came the dazed andgroaning wounded from the disaster area.From residential districts came parentslooking for children and children lookingfor parents.Immediately after the explosions, TexasCity could do little to help itself. <strong>The</strong>rewas no city water, no electricity, no facilitieswith which to fight the flames. <strong>The</strong>first appeal to the outside world camewhen a light blinked at a Galveston switchboard.Over the Texas City circuit came atelephone supervisor's voice, "For God'ssake, send the Red Cross." From Galveston,<strong>by</strong> telephone, telegraph and radio,the dreadful news spread to the nation—and the nation responded.Galveston, which had known tragedywhen 6000 died there in the 1900 hurricaneand tidal wave, was already in action.<strong>The</strong>re was a county disaster plan. Froma high window(Continued on Page 98)

98(Continuea from Page 96) overlookingthe bay, a physician connected with theRed Cross saw the not-too-distant waterfront dissolve as though in a bizarre hallucination.He and his staff alerted all citydoctors for emergency duty; then calledJohn Sealy Hospital, St. Mary's Infirmary,Fort Crockett and the United StatesMarine Hospital to advise them to preparefor mass intake of casualties. Fifteenminutes after the explosion, a Galvestontransit company had buses and cars atthe hospitals to take doctors, nurses andmedical supplies to the neighboring community.Another fifteen minutes and theywere on their way.Gradually at Texas City some orderbegan to emerge from chaos. Escape wasthe first impulse of many families; as oiltanks and stills exploded and burned atrefineries, women and men and childrentook to the roads and the fields, wanderingin dull terror. Mayor J. C. Trahanand Police Chief W. L. Ladish co-ordinatedthe activities of the relief agencieswhich now began to pour in <strong>by</strong> plane andautomobile from the outside world. Dr.Clarence F. Quinn, who had served underGeneral Patton as a combat surgeonin World War II, was appointed medicaldirector and drew on his battle experienceto set up efficient first-aid stations.By afternoon, Army, Navy, Air Forceand Coast Guard teams were there tosupplement the efforts of Texas City andGalveston volunteers. From St. Louisand Washington, D.C., came Red Crossprofessionals. From Houston, Dallas,Fort Worth, Beaumont, San Antonio,Port Arthur and other communities camepolice to augment a hard-pressed force.From all adjacent towns came doctorsand nurses and stretcher bearers. <strong>The</strong>Army established field kitchens to feedthe homeless and bewildered.Just an hour and fifteen minutes afterthe Grandcamp exploded, the first mercyplanes were circling Texas City's smallairport. Military, airline, civil-air-patroland private planes—literally hundreds ofthem—brought in personnel and suppliesfrom as far away as California and Massachusetts.Cargo included blood plasmaand embalming fluid, blankets, beds, gasmasks, X-ray equipment, penicillin, food,foam fire extinguishers, asbestos flamefightingsuits.<strong>The</strong> flames had not been slaked as eveningof the first day approached. At sixP.M. Coast Guardsmen reported that theHigh Flyer was on fire. <strong>The</strong> Grandcamp'sexplosion had torn the High Flyer andthe Wilson B. Keene loose from theirmoorings; they were jammed togetherand could not be separated. Now theknocked-down boxcars in the High Flyer'shold were burning fiercely. Apprehensiveabout the ammonium nitrate inthe cargo, city officials at 7:30 orderedthe town evacuated. Once again there wasmass exodus, but, heedless of warnings,the rescue squads in the dock area, theembalmers, the soldiers and police andfiremen worked on. Two huge searchlightsfrom Fort Crockett helped them.<strong>The</strong> Lykes Brothers steamship firm,owner of both the High Flyer and Keene,had flown in two company executivesfrom New Orleans, and efforts were madeto save the imperiled ships <strong>by</strong> towingthem to sea. At eleven P.M. four tugs arrivedfrom Galveston. Lines were putaboard the locked vessels, but after twohours of pulling and hauling, they hadnot been disengaged.Swede Sandberg, a bloody bandagearound his head, was again in commandat the docks. J. C. Smith, a sixty-sevenyear-oldSalvation Army sergeant, wasthere too. He had taken his mobile canteento every major disaster along the gulffor five years, and he continued to servedoughnuts and coffee. A few minutes beforeone A.M. Sandberg saw "what appearedto be Roman candles" shootingskyward from the High Flyer; he hadseen Roman candles like those just beforethe Grandcamp blew. Sandberg gave ordersat once to sound the whistle andclear the area. <strong>The</strong> tugs cast off their linesand headed out into the harbor. Two orthree hundred emergency workers beathasty retreat. At 1:10 the High Flyer exploded.A fragment of the ship slicedthrough the mobile canteen and amputatedSergeant Smith's foot. Sandbergwas the last man to leave the docks. Almostmiraculously, he had again escapedserious injury.<strong>The</strong> High Flyer vanished. Half of theWilson B. Keene climbed up out of theslip, turned end over end, traveled over ademolished warehouse and came to rest300 feet away. Incandescent missiles setafire four oil tanks at the Humble PipeLine Company, two dockside tanks ofUnion Carbide, a Republic Oil RefiningCompany tank and two more tanks at thealready heavily hit Stone Oil Company.An 8000-pound turbine traveled 4000feet through the air and crashed into apump-house roof at Republic. <strong>The</strong> HighFlyer explosions—there were thalmost as violent as those of e the Grandcamp.Yet this time the casualty list wasgratifyingly small. One man was killedand twenty-four injured.Fires continued throughout the night—indeed the last of the fires did not burnout until Tuesday, April twenty-second,but <strong>by</strong> morning of the seventeenth theworst was over.<strong>The</strong> concern of Texas City immediatelyafter its catastrophe was not inquiry orinvestigation, but plain survival. Some2500 people were homeless and jobless;You be the JudgeBy JOSE SCHORROn a vacation tour, Torn filled his gas tank at a service station. Heremained parked there while his wife bought souvenirs across thestreet. Walking through the station to the car, she fell into anunguarded grease pit. When the station refused to pay for herinjuries, she sued."You owe it to your customers to protect them <strong>by</strong> doing businessin a safe place," she contended. "Instead, that grease pitmakes your station a trap.""After your husband paid for the gas, you were no longer customers,"the station's lawyer replied. "You were just using thestation as a free parking lot, at your own risk."If you were the judge, would you make the station pay?• •• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• •••<strong>The</strong> station did not have to pay. <strong>The</strong>court said that the couple were notcustomers after buying the gas, andmany of them possessed only the clotheson their backs. All commerce and industrywas at a standstill. <strong>The</strong> dead had leftbehind them a total of 844 dependents—widows, children, parents, some utterlywithout resources.In this emergency the Red Cross andthe whole nation came generously to therescue. But local businessmen, staringsomberly at the ruins, thought about thefuture. Was Texas City finished as a portand industrial center? It well might havebeen except for the decision of one man.While bulldozers cleared pathways throughrubble, while fireboats still played harborwater on twisted steel, Edgar Queenypublicly announced that Monsanto wouldrebuild its Texas City branch.<strong>The</strong> announcement and its timing werehighly important to the town's economyand morale. It undoubtedly prevented ageneral exodus of skilled labor to otherareas; it probably affected the decisionsof other major companies on whether togo or stay. Monsanto also set an example<strong>by</strong> moving in at once to alleviate with coldcash the hardships of its own people. Aspecial fund of $500,000 was made availableto its personnel officers.Most of the employees of the majorplants and refineries were covered <strong>by</strong>group insurance, and adjusters beganmaking payments forty-eight hours afterthe blast. Individual life insurance andliability policies, in the main, were paidwith similar promptness and celerity. Butthere were many in the morgues and hospitalswho had little insurance or no insuranceat all. Some had been at thedocks as sight-seers and had no claim onworkmen's compensation. Others werechildren, housewives, residents of near<strong>by</strong>houses and volunteer rescue workers.the station was therefore under noobligation to guard their safety.Based upon a 1954 Vermont decision.THE SATURDAY EVENING POSTWhere did the responsibility for theslaughter of the innocents lie? <strong>The</strong> Texasbar believed the responsibility belongedto the United States Government, andmore than 100 lawyers elected to representTexas City clients in damage suits.Some 300 suits were filed <strong>by</strong> 8485 plaintiffs.Basically their case can be summedup as follows: -<strong>The</strong> tremendous power of the blastscame from the fertilizer-grade ammoniumnitrate (FGAN) in the holds of the Grandcampand High Flyer. <strong>The</strong> fertilizer, sometimesdescribed as a distant cousin of dynamite,had been manufactured in threeArmy ordnance plants and shipped <strong>by</strong>rail to Texas in 100-pound laminated bagsfor reshipment to France.<strong>The</strong> Government, then, was guilty ofculpable negligence because, (1) FGANwas a fire hazard and dangerous explosiveand caused the disaster; (2) the FGANwas manufactured and transported underGovernment auspices; (3) the Government,"well knowing the dangerousnature" of FGAN, had failed to notifypublic carriers and their employees, thesteamships and the town of Texas City ofits innate hazards and thus failed to protectthe public.Obviously 100 lawyers and 300 lawsuitswere too many lawyers and toomany lawsuits. By agreement, and withcourt permission, it was decided to consolidateon one test case to determine thewhole question of Government liability.Mrs. Dalehite's suit for compensation forthe death of her husband becathe the testcase.When it comes to suing Uncle Sam, weAmericans can never quite get the Kingof England out of our hair, for our rulethat the Government—that is, "the sovereign"—cannotbe sued without its ownconsent is a heritage from centuries-oldBritish jurisprudence. However, a yearbefore the disaster, Congress passed theFederal Torts Claims Act which permittedlegal remedy for certain wrongs ofGovernment officers and employees. Itwas under this provision that the test casewas brought.<strong>The</strong> Attorney General's office deniedboth the applicability of the provisionand the charges of negligence. "Testsmade over more than a quarter of a century,"the court was told at one point,"have demonstrated that FGAN is notexplosive in the ordinary course of handling,transportation and use." And, indeed,that had been the general belief beforethe Grandcamp blast.Background facts about this particularcargo of FGAN reveal how even a smallTexas town can be caught up in the rushof world events. In 1946 the occupiedcountries—Germany and Japan and Korea—facedfamine. Commanders theresaid the choice was "additional food oradditional troops to control the conqueredpeople." Neither sufficient quantitiesof food nor ships to transport itwere available. But the shipping of fertilizerto the occupied areas offered a solution;a ton of fertilizer, it is often said,will grow seven tons of food. However,there was a grave drawback. <strong>The</strong> entireproduction of commercial fertilizer in theUnited States was committed to an internationalbody, the Combined Food Board,for domestic use and the use of our exhaustedallies; none was available for therecent enemy.In this crisis the War Department decidedto reactivate fifteen surplus ordnanceplants and manufacture its ownfertilizer. This, as a matter of high policy,was approved <strong>by</strong> the Cabinet. But it soonbecame evident that the plants would notget into full production in time for theoverseas planting seasons, so the WarDepartment was permitted <strong>by</strong> the CombinedFood(Continued on Page 100)

100 THE SATURDAY EVENING POSTKills that chill—modern 2laoa action*Best Chill Protection — ExclusiveDuofold 2-layer fabricworks two ways: (1) Quicklyabsorbs body moisture; (2)Evaporates it away from theskin. Keeps you dry and chillfree,indoors and out.Nothing Warmer — Not onebut two insulating layers. Notone but a complete range ofstyles and fabric weights.Bulk-Free! Itch-Free! Lightweight!— <strong>The</strong> last word inwearing comfort. See yourDuofold dealer now.Duofold Inc., Mohawk, N. Y.Distributed in Canada <strong>by</strong> CordonMackay & Co.. Ltd., Toronto, Ont.In trim longies-'n-T-shirts and unionsuits for men; sports styles in Sun ValleyRed* for the entire family; PeppermintCandy Stripe• for girls and ladies.NEW...Powder-Snow Blue•for ladies. . . all shrink-resistant.*Trademarks*2-layer ACTIONmakes the difference!COTTONWOOLfor COMFORT for WARMTHnext to your skin in outer layer.. soft, absorbent ...virgin wool— blots up nature's warmestbody moisture, fiber ... killsno itch!evaporation chill.A fefre...handsomeCABINET KITCHENrefrigerntor • stove • freezer • sinkDOGS — CATS — BIRDSSTOP Misery! Itch, Eczema, Dry coatdue to lack SKIN VITAMIN—linoleic oil(51K in Rex). Add to food. Give Beauty,Brilliant Sheen to Coat or Feathers.FREE LITERATURE, REX, MONTICELLO, ILL.unfold2- a iirasullated undẹriy.ue.adisonly 29" wideClosedPerfect for offices,patios, recreation rooms, motels andapartments. Combines refrigerator,stove, freezer and sink — alsoavailable with oven. Natural woodand white finishes.WRITE FOR FULL DETAILS TOGENERAL AIR CONDITIONING CORP.Dept. 11.9 4542 E. Dunham St.Los Angeles 23, CaliforniaGeneral ChefNATIONWIDE SALESAND SERVICESTIMUSCLES?I 1 i 1 S 8 a ft; derMOSSO leA Treat as well as a Treatment for your SKIN andMUSCLES: Non-alcoholic, not greasy, can't stain,89c and $1.49 at drug counters. (no fed. tax.)USED FOR SKIN COMFORT IN 4,000 HOSPITALSOPPORTUNITYF YOU want extra money, and have spare timeI to put to use, this is for you! You can spend yourspare time taking orders for magazine subscriptions—andearning generous commissions.Just send us your name and address on a postal. Inreturn, we will send you our offer with starting supplies.From then on, YOU are the boss. Subscriptionwork of this type can be carried on right from yourown home. As an independent representative, youmay work whenever it is most convenient for you.Write that postal today. Information and suppliesare sent at no obligation to you.CURTIS CIRCULATION COMPANY257 Independence Square, Philadelphia 5, Pa.SHE FIXED IT ALL HERSELFwith LEECHFLUID CEMENTWs easy to get a "professional touch" onALL household fixing, with Leech professionaltype cements and glues! Ask forLeech fix-it products at your dealers.Plastic ResinAll Purpose GluePorcelain Touch UpLiquid SolderWeatherstrip AdhesivePatch CementHousehold Cement1.1,1C11 PIOSDCTS CO., 1st 243, Ifinchlesse, talus(Continued from Page 98) Board to"borrow" from commercial producerssufficient fertilizer to meet its early needs.This was purchased under a sell-back arrangement.<strong>The</strong> FGAN shipped to TexasCity in 1947 was part of the Government'srepayment to the Lion Oil Company, acommercial concern, which, in turn, transferredownership to an agency of the republicof France.Two years after the lawsuit's beginnings,it came to trial in Houston. <strong>The</strong>trial lasted ninety days—including timeout for a hurricane—and the record ranto 20,000 pages. Many millions of dollarsin damages were at stake, including thelarge claims of insurance companies. FederalJudge T. M. Kennerly considered thecomplex case for five months. In the endhe found the Government liable, and enteredjudgment in favor of all petitioners.Eighty charges of negligence and liabilitywere sustained. Mrs. Dalehite was awarded$60,000, and her son, Henry G. Dalehite,Jr., $15,000.<strong>The</strong>'Goverrunent immediately appealed.In June, 1952, the six judges of the Courtof Appeals, Fifth Circuit, unanimouslyreversed the Kennerly judgment. Now theplaintiffs appealed. In June, 1953, theSupreme Court in a 4-3 decision ruledthat the victims of the Texas City disastercould not collect compensation from theUnited States under presently existinglaws. It was the ghost of the King of Englandagain, as Mr. Justice Reed, whowrote the majority opinion, made evident.No finding of fact was made as towhether the Government had or had notbeen negligent in its handling of FGAN.It may have been that when Congresspassed the Torts Claims Act it had inmind compensation for such bush-leaguetorts as accidents resulting from negligentoperation of mail trucks or military vehicles.Certainly it attempted to protect thestate specifically from liability for errors"in administration or in the exercise ofdiscretionary function." Justice Reed andhis confreres decided the Cabinet-leveldecision to institute the fertilizer programwas a "discretionary act" and that, thus,the Government was immune to suit.Mr. Justice Jackson, spokesman for theminority, disagreed in an indignant andcaustic opinion. He had no doubt of theGovernment's negligence and said thecourt would certainly hold a private corporationliable in a similar situation. <strong>The</strong>"discretionary-act" thesis, he maintained,did not carry over to the Government'sactivities as a manufacturer and shipper.And if it were liable only for minor trafficaccidents, he concluded, "the ancient anddiscredited doctrine that `<strong>The</strong> king can dono wrong' has not been uprooted; it hasmerely been amended to read, `<strong>The</strong> kingcan do only a little wrong.' "Texas City victims applauded this eloquence,but their legal resources were exhausted.Clark W. Thompson, memberof the House of Representatives fromGalveston, a former marine colonel whohimself had served as a volunteer workerduring the disaster, immediately began afight to compensate them <strong>by</strong> a special actof Congress. Hearings opened in November,1953, and hopes brightened—only togive way to frustration and bitterness asthe slow machinery on Capitol Hill groundits gears crankily and almost came to ahalt.But Congressman Thompson kept upthe struggle, and eventually the bill waspassed. President Eisenhower approvedit on August 12, 1955. <strong>The</strong> Secretary ofthe Army was directed to investigateclaims and to determine and fix the awardswhich should be made to disaster claimants.<strong>The</strong> new law ruled out payments tounderwriters and insurance companies,on the premise that they had taken acommercial risk. It put a top limit of $25,-000 on death claims, personal-injury claimsand property-damage claims. Attorneys'fees were to be paid out of the awards andlimited to 10 per cent. Awards for compensationwere to be determined <strong>by</strong> thepractice and standards of the state ofTexas.After long years of waiting, the peopleof Texas City now got action. It was achallenging and unprecedented assignmentfor the office of the Judge AdvocateGeneral of the Army. Col. Alfred Bowman,chief of the claims division, organized,trained and dispatched a task forceof thirty-eight officers to Texas City ; thefield commander was Lt. Col. Tom Marmon,a Lone Star Stater himself. Consultantwas Maj. Gen. C.B. Mickelwait (Ret.),former assistant judge advocate general,who had followed the disaster litigationfrom the beginning.Met at first <strong>by</strong> grim suspicion in a towndisenchanted with Washington officialdom,the task force soon won praise forits fairness and sympathetic handling ofclaims. In a little more than a year 1755cases were processed, 1394 awards weremade, and Treasury checks totaling almost$17,000,000 were issued.When the final case was processed inFebruary of this year, CongressmanThompson paid a visit to the JAG centerat Fort Holabird in Baltimore, Maryland.Speaking for his people, he congratulatedthe Army on its speed and -efficiency,and described the whole operation as "amagnificent job in public relations."Texas City today would seem strangeto the Red Cross teams, the Eastern reportersand radio broadcasters who knewit only in its dire extremity. It has doubledin population and more than doubledin area ; one way or another, it hasassimilated into its corporate limits largeclutches of once-open country which nowboast housing developments. It has spentmany millions on impressive schools anderected a handsome new city hall. <strong>The</strong>days of desperation seem long ago.Shortly after the disaster, a dispossessedbut doughty local merchant named CharlesLerman put up a frequently photographedsign beside his collapsed department store:WE'RE DOWN, BUT NOT OUT. Indeed, amonth later and with a brand-new stock,Lerman was conducting his business froma Quonset hut. <strong>The</strong> sign was propheticfor Texas City. In ten years there has beena marked influx of new industry. At nightglowing towers and flare stacks light thebrackish meadows like a splendid ConeyIsland. <strong>The</strong> original Monsanto plant occupiedthirty acres. Today's Monsanto'soperating units and buildings cover 133acres and the working force has tripled insize.Not long ago I went to Texas City totalk to survivors and to get the firsthandinformation on which this article is based.For all its prosperity, the town still bearsthe stigmata of its agony and the scars ofold wounds. In a back yard of First Street,deeply imbedded and bordered <strong>by</strong> shrubs,lies an immense section of the hull of theGrandcamp. <strong>The</strong> Texas City Terminal—where fifty employees were killed and 129injured—weathered difficult financialyears, but its prospects are bright again.New buildings have arisen, but the docksand warehouses which disappeared withthe Grandcamp have not been replaced.A tall concrete grain elevator, pierced <strong>by</strong>a molten section of the High Flyer, stillstands, but is not in use. <strong>The</strong> Terminalnow concentrates on the shipment of oilsand chemicals.Reminiscence brought back to thoseinterviewed the panic, uncertainty andheartbreak of a decade ago. It also broughtback a justifiable j feeling of civic pride,

October 26, 1957for most of Texas City's residents actedwith courage and generosity and selfreliancein the face of calamity. Local officialsremained in complete control at alltimes; invocation of martial law was nevereven considered. Those who fought thefires, cared for the dead and sought toidentify, the unidentifiable literally hadneither 'sleep nor change of clothing inmany days. <strong>The</strong>ir fealty to duty is notforgotten.As a reporter, I was curious to discoverhow a community reacts when largeamounts of Treasury money are suddenlysiphoned into it, and I questioned threescorepersons who received Governmentchecks. Happily, I have no giddy extravaganzasto chronicle, none of the blunderand plunder and fool's-gold spendingwhich makes the Irish Sweepstakes windfallsthe tabloids' delight. Texas Cityagain has reason for civic pride : the moneyhas been handled sanely and soberly—asinformed businessmen, bankers and lawyersall agree.<strong>The</strong>re are exceptional cases, of course,but not too many. I heard of one glowingpink automobile, but did not see it. Iheard the phrase "living it up," but sawlittle evidence of carnival. Actually, thecompensation voted <strong>by</strong> Congress—althoughthe $17,000,000 total seems tobulk large—did not err on the side of liberality;a sign-off award of $25,000 fordeath or permanent injury is much lessIt seems that the next waris to be fought over disarmament.JACK HERBERTthan usually arrived at in a jury trial. Topaward on the Army records was $49,000.This represented compensation for thedeath of an earning husband and father,severe injury and prolonged hospitalizationof his wife, and heavy property damage.This part of the Texas City chronicledoes not make high drama, but it makesheartening good sense. In the main, Governmentmoney has gone into the purchaseof homes, savings accounts, investmentslooking toward college educationfor youngsters. Funds due orphaned childrenwere put in escrow and can be disbursedonly <strong>by</strong> permission of the courts,which have zealously and wisely safeguardedtheir interests.Here are the stories of two of the manysurvivors I interviewed; their stewardshipof compensation money is typical of theTexas City scene. Vern Linton, now fiftyoneand night superintendent of the Monsantoplant, was on the top floor of afive-story building when the Grandcampexploded. With crushed vertebrae, a badlytorn arm and a useless leg that was lateramputated, Linton escaped the approachingflames <strong>by</strong> sliding down the banister ofa steel staircase to the fourth floor andthen descending, hand over hand, <strong>by</strong> wayof an outside water pipe. After that hecrawled fourteen blocks to safety. Bustedback, artificial leg and all, Vern Lintonreturned to work nine months later, andhas missed only four working days innine years. Vern's $25,000 Governmentcheck has gone into stocks and savings.Ultimately it will finance the medical educationof his younger son. An older boyIs already a mechanical engineer employed<strong>by</strong> an oil company.Fred Grissom, a young engineer justgraduated from the University of Texas,had risen from his drawing board andwas standing <strong>by</strong> a window when the blastCame. Glass blinded him, but somehowhe reached street level. <strong>The</strong>re he encountereda construction worker who couldnot walk. <strong>The</strong>ir meeting is now a legendin Texas City. Fred Grissom furnishedthe legs and the lugging, and the constructionworker furnished the eyesight.Both got to Galveston hospitals. Fred'sright eye was removed, and later a cataractdeveloped in his left eye. That requiredtwo operations, but with his oneuseful eye Fred has been continuously atwork since May, 1950. He has acquired apretty Louisiana wife, two promotions—he is now superintendent of utilities—andthree engaging children. <strong>The</strong> $25,000Treasury check has been used for a needednew car, stocks and bonds.When I was in Texas City, doctors andcivil-defense people were working on aplan for mass evacuation of the Houston-Galveston-Beaumont area in case ofH-bomb attack, and lessons learned inthe 1947 calamity were high on theirslate. John Sealy in Galveston is the teachinghospital of the University of TexasMedical School and carried the heaviestpart of the medical and surgical burden.<strong>The</strong> extraordinary efficiency of casualtycare there is attributed <strong>by</strong> the hospital authoritiesto the fact that, in 1947, most ofthe medical faculty, the seventy-five residentsand eighteen interns were formerArmy doctors who had served overseas.Drs. Virginia Blocker and T. G. Blocker,of John Sealy, have made a survey of 3000Texas City casualties who were in a 4000-foot radius of the explosion. More thanone third of the patients had perforationsof one or both eardrums. Only seven patientswere treated for serious burns;burns occurred principally at the Monsantoplant, and were fatal burns. Fewerthan fifty patients died in hospitals. <strong>The</strong>rewere seven instances of clinical gas gangrenebut no deaths. Penicillin—then newto medicine—made the difference. <strong>The</strong>disaster almost exhausted the supply ofthe whole nation; two billion units ofpenicillin went there <strong>by</strong> air.<strong>The</strong> passing of the years has in no wisewatered down the gratitude the people ofTexas City feel toward the Red Cross andthe people of the nation who came totheir aid in the time of trouble. Examinedin retrospect, the performance of the RedCross can be described as nothing lessthan superlative. Approximately 2000families received financial assistance, anda few of them were a full or partial responsibilityfor several years. For a periodof weeks 1400 homeless people weresheltered and fed at Camp Wallace, awartime military establishment reopenedfor the emergency. In all, the nationalRed Cross spent $1,247,000.<strong>The</strong> amount would have been muchgreater except for extensive benefits fromother sources. Workmen's compensationhelped many victims. All the larger industriesin Texas City contributed liberally torelief. <strong>The</strong>n there were the heart-warmingmoney gifts which, unsolicited, came infrom the American people everywhere,reaching the amazing total of $1,068,000.A local committee headed <strong>by</strong> CarlNessler, businessman and onetime mayor,received and administered this Texas CityRelief Fund. Unions, banking, business,industry and the clergy were representedon the committee. No money whateverwas spent for overhead; even office spacewas donated. Every nickel went for goodworks. In examining the records, 1 discoveredthat the last check was issued onMay 1, 1953. That closed the books.<strong>The</strong>re is a postscript to the story. Railroadcars carrying FGAN destined forTexas City were rerouted after the disaster.At Baltimore the FGAN was loadedon the SS Ocean Liberty. <strong>The</strong> vesselcaught fire outside the harbor at Brest,France, on July 28, 1947. Twenty personswere killed and 500 injured. THE ENDROYAL TRITM1Announcing a new formulationof Royal Triton 10-30...the amazing purple motor oilNow more than ever, all-weather Royal Triton 10-30 prolongs yourengine's trouble-free performance for thousands of extramiles. Royal Triton 10-30--the all-weather grade of the amazingpurple motor oils. Ask for it wherever fine motor oils are sold.UNION OIL COMPANY OF CALIFORNIALos Angeles: Union 011 Bldg. • New York: 45 Rockefeller Plaza • Chicago: 1605 Bankers Bldg. • Boston: 214 Harvard Ave.Philadelphia: No. One Wynnewood Rd., Wynnewood, Pa. • Kansas City, Mo.: 612 W. 47th St. • Dallas: Fidelity Union Life Bldg.New Orleans: 644 Nat'l Bank of Commerce Bldg. • Atlanta: 1401 Peachtree St.I 0 I

![[PDF]. - The Saturday Evening Post](https://img.yumpu.com/51285309/1/190x238/pdf-the-saturday-evening-post.jpg?quality=85)