The Legal Environment for Ground Forces - Integrated Defence Staff

The Legal Environment for Ground Forces - Integrated Defence Staff

The Legal Environment for Ground Forces - Integrated Defence Staff

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

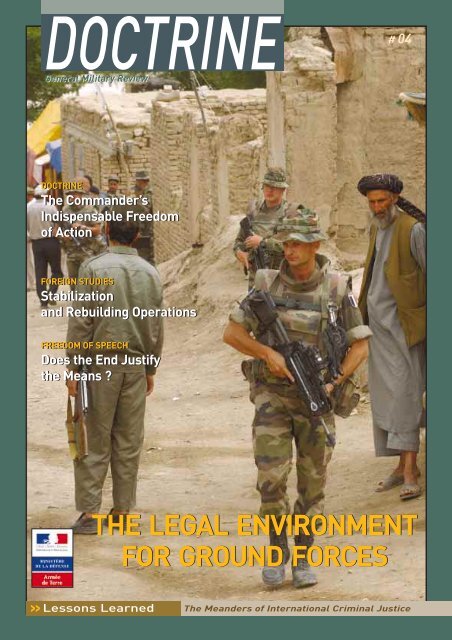

FOREWORDIn his famous book, Law in Wartime and Peacetime, Grotius wrote “ a famous Roman general pretendedthat the clamor of the battlefield kept him from hearing the voice of the law. ” In 1625,Grotius added that “ nothing is more common than putting law and weapons at odds ” - this is aserious error.Would any of our soldiers questionthat today ? <strong>The</strong> soldier isat odds with many issues : theexpansion of international laws ; themultiplicity and swelling of internationalregulations ; the confrontation ofheterogeneous national laws within complexmultinational consultations ; thediversity and types of new missions <strong>for</strong>eignto accepted norms of the Law of LandWarfare ; the permanent obligation tojustify his actions in front of the publicopinion. All parties, on a permanentbasis, scrutinize the daily actions of soldiersagainst the law.Law can sometimes be used as a flag.It can also be used as an instrument toserve a party. On the other hand, withoutit, no action can be legitimated.As a matter of fact, what law gives a soldierthe extraordinary permission to useviolence ?Further, what law allows him to interveneoutside of his own borders ?Lastly, what law allows him to silencethe guns in <strong>for</strong>eign lands ?It is vital that the officers leading an armythat deploys 10,000 to 15,000 soldiersin out-of-area operations on a constantbasis become aware of the legal frameworksurrounding their actions. Recentstudies carried out by the commissionon the general status of the military havedemonstrated the magnitude of theseissues.I am pleased to take notice that“ Doctrine ” has dedicated this editionto this problem. It is also important toobserve that this deliberation is not limitedto the personnel of the legal directorate.I trust that this study will be fruitful.Because without law, there is neitherState of legitimacy nor democracy, andas Pascal wrote : “ <strong>for</strong>ce and justice coexistto ensure peace, the overarchingwealth. ”CCH J.J. CHATARD/SIRPA TerreCatherine BERGEAL,Senior <strong>Legal</strong> Counsel, Council of StateDirector, Juridical AffairsSEPTEMBER 2004 4 DOCTRINE # 04

doctrine<strong>The</strong> Commander’sIndispensable Freedom of ActionBecause of the increasing number of overseas deployments, French soldiers are often confronted to a new problem :the frequent lack of a clearly defined legal framework. Sometimes, as a corollary to that issue, some (<strong>for</strong>tunately veryfew) soldiers fall into legal problems. This has caused the legal protection of the soldier in overseas (out-of-area)operations to be a particularly sensitive topic in the course of the last few years. Members of the Armed <strong>Forces</strong>(particularly of the Army) have developed a mounting feeling of distrust and sometimes fear of national andinternational judiciary institutions because of the increasing role of the legal issues within western societies,growingly prominent in France. As such, they rightly refuse to receive the attention of the justice <strong>for</strong> having used <strong>for</strong>cewhile obeying a national order.Somehow, the reality of this possibility causes a “ feeling of legal insecurity ” 1 . <strong>The</strong> resulting psychological effectscan cause some subordinates to become faint-hearted or even turn some leaders into inaction, or even to declineresponsibility.However, this aversion to risk-taking (the fear of the possible consequences of the decisions taken at the timeof events - especially when they are highly publicized in the media) can inhibit certain leaders’ action at all levelsof command and thus limit their necessary freedom of action. This freedom is essential <strong>for</strong> the proper execution ofthe missions that they were entrusted with by the Nation - within the framework, or not, of an international or localorganization.BY GENERAL (RET) JEAN-MARIE VEYRAT, EDITOR OF “DOCTRINE ” MAGAZINECCH J.J. CHATARD/SIRPA TerreHence, this premiseestablishes that the legalframework of their actionshould be clearly definedby the authorities in charge,in particular by the politicalauthorities that have setthe operational objective.First and <strong>for</strong>emost, the<strong>for</strong>mulation of the desiredend-state and the rules ofengagement (ROE) must bespecified. <strong>The</strong> description ofthe legal framework shouldgo well beyond the chieflytechnical opinions renderedby legal specialists who arenot always well aware ofthe realities on the ground.With the necessary freedomof action and the associatedconfidence which will havebeen granted to them, themilitary commanders willthen be able, at all levels ofthe hierarchy, and withinthe joint and generallymultinational framework ofan operation, to detail thedirectives received, and togive orders and guidance.All this in accordance withthe doctrine of employmentof the French <strong>for</strong>ces, whichremains, <strong>for</strong> our units andstaffs, the best protectionbecause they are thesynthesis of internationaland national rules that areto be applied by the armed<strong>for</strong>ces of a democraticcountry.ARMED FORCES CONDUCTINGOVERSEAS (OUT-OF-AREA)OPERATIONS ARE CONFRONTED TOLEGAL ISSUES LINKED TO THEIRACTIONS, INCLUDING POTENTIALPENAL CONSEQUENCES.<strong>The</strong> often speedy initiationof operations generallyprevents from assigning <strong>for</strong>each a specific and preciselegal framework, welladapted to the theatre andthe types of actions to becarried out. On the contrary,there is usually asuperposition ofinternational, national, andlocal laws, which does notfacilitate the task of thosewho are to ensure that thoseregulations are respected.<strong>The</strong>y are magistrates, policeofficers, provosts, and theyoften choose to apply the lawthat they know best, ingeneral the national law,which, in any event, remainsapplicable to the Frenchnationals. This national law,designed to be internal, isoften badly adapted to ourunits’ framework of action,which is neither peace norwar, but rather some sort ofundeclared conflict or acrisis. <strong>The</strong>se situations areSEPTEMBER 2004 5 DOCTRINE # 04

<strong>The</strong> Statutory Recognitionof Service Members Involvedin Overseas Operations<strong>The</strong> national law is the legal basis <strong>for</strong> the action of the service member in overseas (out-of-area)operations. Even in a <strong>for</strong>eign country, “ in all times and places ” (article 12 of the statutes),the soldier exclusively falls within the scope of national law. This legal recognition results from aset of provisions mainly articulated around the general statutes of the service member ; criminallaw and the military justice code (article 27 of the statutes) ; the 6 of August 1955 law pertaining tothe advantages granted to military personnel involved in maintenance of law and order operationsunder certain circumstances; and the pension code (article 20 of the statutes).This legal recognition does not however particularly distinguish overseas operations as an actiondeparting from common law : on the contrary, soldiers are “ subject to common criminal law aswell as to the provisions of the military justice code ” (article 27 of the statutes). As professionalsoldiers, they benefit from a risk cover and a compensation right (articles 20, 58, 59 et 60 ofthe statutes) <strong>for</strong> recorded disabilities “ resulting from or occurring during service ” (articles L2 et L3of the disability military pension code).BY COLONEL GUILLAUME DE CHERGÉ, LEGAL ADVISER OF THE SOUTH-WEST ARMY REGION<strong>Legal</strong> Recognition Vs.the Reality of OverSeasOperationsSo, the legal recognitiongiven by the statutes is notadapted to the ambiguousreality of overseasoperations. In fact, overseasoperations are notnecessarily war operationsbut, most frequently, the wayto bring to an end an armedconflict that does not have aninternational nature,and without the projected<strong>for</strong>ce having to take anactive part in the conflict.<strong>The</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, the servicemember is exposed toexceptional risks.<strong>The</strong> legal misapprehensionof these risks can affect andturn the responsibilitysystem in overseasoperations into an ordinary,especially in the followingareas :- the assimilation of therecourse to <strong>for</strong>ce to thecase of action in selfdefense<strong>for</strong> oneself or <strong>for</strong>others ;- the professionalmisconduct madeimprudently or followingnon-action, especially incases of emergency orfailure to assist a person indanger ;- the evaluation of damagesencountered or made inconnection with its link toservice ;- the always possibleopening of a preliminaryinvestigation against amilitary based on adenunciation.Thus, the personal natureof the action of the soldierdetermines the level ofresponsibility : militarypersonnel benefit fromState protection as soonas he “ is subject tocriminal prosecutionsresulting from facts whichdo not have a nature ofpersonal misconduct ”(article 24 of the statutes).This personal nature alsoappears in the judicialproceedings when thesoldier is summoned aswitness of incriminatedfacts. <strong>The</strong>se proceedingsdisregard the statutorylink to retain one criminaloffense nature concerningthe carried out action.Widening of the Self-Defense Concept to theFramework of the Mission<strong>The</strong> revision of the militarygeneral statutes, as itappears in the draft 1 , sticksto the principle of the individualityof the service memberin overseas operations.However, it is aimed atenhancing the statutorywarranties (article 1 of thestatutes) in accordance withthe general legal principles.If the soldier cannot claimimmunity resulting from thefact that he is acting inoperations and followingorders, he can benefit nowfrom a positive judicialqualification of his action, ina follow-on criminalproceedings connecting hisactions to service.DOCTRINE # 04 8 SEPTEMBER 2004

doctrineCCH J.J. CHATARD/SIRPA Terre<strong>for</strong> the Senate. As thenstressed by Professor GuyCarcassonne : “ Indeed andas, everybody knows, thisvote was not legallyindispensable. It was not anauthorization ; it was thecase of a confidence motionon a precise issue. It was notat all indispensable <strong>for</strong> theCommander-in-Chief of theArmies to legally be able tocommit France in thisconflict. ”Such a power given to theParliament would require aconstitutional change.During the debate, withoutvote, on Kosovo, which tookplace on April 1999 in thenational Assembly, thePresident of the DefenseCommission, in this sense,expressed the wish that theGovernment would ask <strong>for</strong>the authorization ofParliament be<strong>for</strong>ecommitting troops overseas.<strong>The</strong> Prime Minister thenjudged that article 35 of theConstitution was not to beapplied but stated, “ the caseof a military engagement onthe ground could not beenvisaged, unless thequestion is submitted to you.You would be <strong>for</strong>mallyconsulted to authorize, ornot, thanks to a vote, such anintervention ”.All in all, the internalframework of overseasoperations seemed to bewell established. Accordingto the Constitution, it is <strong>for</strong>the Parliament to authorizethe declaration of war. Otheroverseas operations fallunder executiveprerogatives. In the later, thein<strong>for</strong>mation modalities of theParliament have howeverbeen rein<strong>for</strong>ced. Thus,Defense Minister AlainRichard, announced fourmeasures on February 4,1999 :- the preparation of a yearlyreport from the defenseministry <strong>for</strong> the Parliamenton overseas operations ;- a debate on this report andthese operations duringsub-appropriationdiscussions ;- a presentation, to thedefense commissions of theNational Assembly and theSenate, of the objectives ofoverseas operations withinthe month following theirstart ;- a visit trip, once every sixmonths, of MPs belongingto defense commissions toarmed <strong>for</strong>ces in overseasoperations.<strong>The</strong> International <strong>Legal</strong>Framework of OverseasOperationsWhile the October 4, 1958Constitution provides <strong>for</strong> thehypothesis of a declarationof war, it also refers to thePreamble of the October 27,1946 Constitution whichstates that “ the FrenchRepublic will not embarkupon any war in view ofconquest and will never useits <strong>for</strong>ces against the libertyof any people ”. Thisprovision is contemporary tothat of the United NationsCharta, signed on June 26,1945 and implemented onthe following October 24.<strong>The</strong> Charta dispositions buildup the international legalframework of recourse to<strong>for</strong>ce.Article 2, paragraph 4 of theCharta states that “ in theirinternational relations themembers of the Organization(of the United Nations) refrainfrom resorting to the threator use of <strong>for</strong>ce, either againstthe territorial integrity or thepolitical independence of anyState, or in any other wayincompatible with the aims ofthe United Nations ”. In thisway, the Charta sets out ageneral principle ofprohibition of recourse to<strong>for</strong>ce, still keeping thelegality of such recourseunder certain circumstancesor in view of certainobjectives.<strong>The</strong> first exception to thisprohibition is well known : itis the one stated in article 51of the Charta concerning the“ national self-defense right,individual or collective,should a member of theUnited Nations have to facean armed aggression, up tillthe Security Council hastaken the necessarymeasures in order tomaintain international peaceand security ”. At first sight,this disposition seemssimple by setting out theprinciple of self-defense.However, in legal terms oneknows that the absence of ageneral definition of“ aggression ” doesn’t solveall the difficulties raised byarticle 51 of the Charta. Inface of the sole 3314resolution of the UnitedNations General Assemblypassed in 1974, aggressioncan, today, only be definedas the intervention of theSecurity Council. Failing suchan intervention, which since1945 has only occurred onceat the time of the “ war inKorea ”, states areauthorized to use theirlegitimate self-defense rightup till it has reached itsobjectives. <strong>The</strong> conduct ofmilitary operations beyondwhat is necessary to repelaggression is not authorizedby this defense.<strong>The</strong> United Nations Charta, towhich article 2, paragraph 4refers to, sets out a secondexception to the prohibitionof the recourse to <strong>for</strong>ce. It isthe one contained in articles42 and 53 pertaining tocollective action taken inview of facing a threatagainst peace, a break ofpeace or an act ofaggression. Article 42, andmore generally chapter VII ofthe Charta to which itbelongs, are legitimatelyseen as one of the cornerstones of the UN structure.<strong>The</strong>se dispositions haveencountered a sharp revivalin their employment with theend of the cold war. <strong>The</strong>concerned resolutions didnot however contain explicitdispositions on recourse to<strong>for</strong>ce, as in most cases, theSecurity Counsel prefers toSEPTEMBER 2004 11 DOCTRINE # 04

use a <strong>for</strong>mulation enablingthe States participating in a<strong>for</strong>ce to take all necessarymeasures in order to fulfilltheir mandate. Such awording should beunderstood in an extensiveway and include recourse to<strong>for</strong>ce.Several examplesemphasize the restraint inwords of the SecurityCouncil resolutions, in whichthe “ recourse to <strong>for</strong>ce ” isonly mentioned in resolution169 dated February 21, 1961<strong>for</strong> the UNAPROC in Congo.After that, <strong>for</strong> Somalia,resolution n° 794 datedDecember 5, 1992authorized, in accordancewith chapter VII of theCharta, the United TaskForce Somalia to use “ allnecessary means to imposesecurity conditions <strong>for</strong>humanitarian operations assoon as possible ”.In Rwanda, France wasauthorized by resolutionn° 929 dated June 22, 1994to use “ all necessary meansto reach the humanitarianobjectives ”. In Haiti, themultinational <strong>for</strong>ce wasauthorized based on chapterVII, thanks to resolutionn° 940 dated July 31, 1994to “ use all necessary meansto facilitate the departure ofthe military leaders ”.As far as East Timor isconcerned, the Intal Force inEast Timor is authorized to“ take all necessarymeasures to fulfill itsmandate ”.Irrespective of self-defenseand of collective actionunder the United Nationsumbrella, these last fifteenyears have seen thedevelopment of a trendadvocating another basis <strong>for</strong>the use of <strong>for</strong>ce, that of the“ right of humanitarianinterference ”. Beyond themoral requirement of facingdistress situations, oneshould question theintegration of this current inaffirmative law.On one hand, the classicinternational law hasacknowledged since longago the right <strong>for</strong> a State toensure the protection of itscitizens overseas in certaincircumstances. This isthe meaning of Max Huber’ssentence, President ofthe IJPC, in 1924 concerningBritish holdings in Morocco.However, law preciselyrestricts this stateprerogative, as it directlyjeopardizes the sovereigntyof another State.<strong>The</strong> intervention <strong>for</strong>the benefit of one’s citizensmust notably be strictlynecessary andproportionate.“ <strong>The</strong> right of humanitarianinterference ” aims at goingfurther than to this stateright of saving its citizens.However, it fits into aninternational law based onthe sovereignty of States.In this way, in 1946the International Court ofJustice in the Straits of Corfuaffair ruled that “ the allegedintervention right can onlybe envisaged ... as thedemonstrationof a <strong>for</strong>ce policy, policy whichin the past, has givenplace to the worst possibleabuses that, whateverthe present deficiencies ofthe international society,may be, should find noplace in international law ”.Humanitarian law faithfullyreflects this orientation.Thus, article 3 of protocol IIof 1977, added to theGeneva Conventions on noninternationalarmed conflictsfurther explains that “nodisposition of the presentprotocol should be invokedas a justification <strong>for</strong> a director indirect intervention,whatever the reason maybe, in the armed conflictor in home or <strong>for</strong>eignaffairs of the other signingparty on the territory ofwhich the conflict occurs ”.Today, some voices arerising to criticize thisaffirmative right, essentiallyin European democracies.<strong>The</strong>ir claim <strong>for</strong> ahumanitarian interferenceright is notably rejected bya great deal of SouthernStates. Hubert Védrine,French Foreign Minister,analyzes this situation inanswering Dominique Moïsi :“ <strong>The</strong> right of interferenceyou are speaking about is ofconcern <strong>for</strong> numerouscountries, as who interferes ?Always the same countries !I believe it is advisable topreserve the sovereignty ofStates... We have difficultiesin assessing what it stillrepresents, <strong>for</strong> a greatmajority of UN MemberStates, in terms of dignity,national identity, andprotection against a worryinginternationalization. I wouldlike to add that, contrarily toan accepted idea, moreproblems emerge due to theweakness of a certainnumber of the 189 UNMember States and not fromtheir excessive strength.”This structuring of theinternational society doesn’tjeopardize <strong>for</strong> States, inaffirmative right, the meansof action in order to facehumanitarian distresssituations. While article 2,paragraph 7 of the Chartastates that “ no dispositionof the said Charta authorizesthe United Nations tointervene in matters whichessentially fall under thenational competence of aState ”, it further states, infact that “ this principledoesn’t jeopardize theimplementation of coercionmeasures stated <strong>for</strong>th inchapter VII ”. It is on thisbasis that operation“ Render Hope ” in Somaliahad been decided in 1992.Of course, it has been thesame <strong>for</strong> Former Yugoslaviaand the United NationsProtection Force from 1992onwards. Examples are nownumerous : Cambodia,Angola, Haiti, Rwanda, andTimor...<strong>The</strong> legal framework ofoverseas operations is bothnational and international.As far as national law isconcerned, it refers to theprerogatives of thelegislative and executivepowers. <strong>The</strong> first oneauthorizes the declaration ofwar ; the second one haswide prerogatives necessary<strong>for</strong> overseas armed actions.As far as international law isconcerned, the UnitedNations Charta defines aprecise framework thatprohibits recourse to armed<strong>for</strong>ce but may authorize it incase of self-defense orcollective action.Such collective actions,under the United Nationsumbrella, are the necessaryanswer to dramatichumanitarian situations invarious countries of theworld. However, after theirdevelopment in the early90’s, such operations arenowadays less numerous.Undoubtedly, the cause <strong>for</strong>this is notably to be soughtin the critics that areimmediately aroused byinactive countries. Thisapparent paradox goes farbeyond the analysis of thelegal framework of overseasactions, but also underlinesthat it is not incomplete.Within the United Nationsand when they want it,States have the means toact in order to face violenceand distress.DOCTRINE # 04 12 SEPTEMBER 2004

doctrine<strong>The</strong> Protection of Service MembersDuring Operations AbroadOverseas operations are an essential activity of our <strong>for</strong>ces. <strong>The</strong> purpose of the proposed reflection isto look into the juridical environment of French service members during operations conductedabroad (or out-of-area).In this regard, it is not considered to be adequate both with respect to the successful conduct of missionsand the medical and social coverage. However, room <strong>for</strong> improvements exist.It is acknowledged that an overseas operation is an operation of a humanitarian nature that can only beconducted after re-establishment (or imposition) of a minimum public order enabling acceptable livingconditions <strong>for</strong> the population. All this being often complicated by the obligation to separate - or imposejoint-living - of populations whose liking or respect <strong>for</strong> others is not the primary concern.<strong>The</strong> action of the soldiers lies within a crisis framework, of a variable intensity (intensity levels are likelyto change very rapidly). <strong>The</strong> recourse to armed <strong>for</strong>ce cannot be excluded; if this happens, is the Frenchservice member sufficiently legally protected ? Protected, yes; sufficiently, no. Let’s be quite clear aboutthis : we are not talking about making him impune. <strong>The</strong> present situation can nevertheless be improved,whilst leaving the completeness of his attributions to the criminal judge.BY COLONEL GILLES BERNARD (ADMINISTRATION), LEGAL AFFAIRS CELL, FRENCH JOINT STAFF<strong>The</strong> Service Member andthe Use of Armed Forceon Overseas OperationsBasic Principle : it is theFrench Law that isApplicable.But in fact, in many cases,an overseas operation hasa multinational nature ; thecommander of thisoperation issues ROEs(Rules of Engagement). Itwill be admitted that theseROEs do not raise any legalissues vis-à-vis the armedconflicts legitimacy and law.<strong>The</strong> problem is that theseROEs are not a legislativeor regulatory disposition inFrench law that are imposedto the criminal judge.In case of possible criminalproceedings, the use ofweapons will be scrutinizedCCH J.J. CHATARD/SIRPA Terrein accordance with thecriminal code provisions,in the light of “ selfdefense” and the level of“ necessity ” ; that’s quiteusual, although thesenotions have beendeveloped taking intoaccount a democratic and“civilized ” society, asituation which is scarcelyencountered duringoverseas operations.However, article 16-1 of thegeneral statutes of thesoldiers imposes to check“ whether the normalconscientiousness, takinginto account theresponsibilities, powersand assets they areendowed with, as well asthe very specific difficultiespertaining to the missionsthey are entrusted by law ”,have been correctlyimplemented. <strong>The</strong> fact ofnot acknowledging theexistence of the ROEs doesnot enable a completeadherence to the provisionsof this article. In order tobe able to reconcile thepossible action of thecriminal judge with article16-1 of the military generalstatutes it is there<strong>for</strong>enecessary to make roomwithin our legal system <strong>for</strong>the ROEs.On one hand, the FrenchState acknowledges thatservice members cancomply with the ROEslegitimately issued by asupranational authorityand, on the other, that itscriminal justice does notrecognize them.<strong>The</strong> review commission ofthe soldier general statuteshas proposed that theSEPTEMBER 2004 13 DOCTRINE # 04

following provision beadded to the militaryjustice code : “ the servicemember is not criminallyliable , when, inaccordance withinternational law provisionsand within the frameworkof a military operationtaking place outsidethe French territory, heexercises coercionmeasures or uses armed<strong>for</strong>ce when it is necessaryin order to fulfillthe mission ”.Although this proposal isa real step <strong>for</strong>ward, itshould however go furtherand specifically quotethe ROEs.This is not aninsurmountable legaldifficulty and would likelyenhance a more sereneclimate <strong>for</strong> action withoutjeopardizing in any waycriminal justiceprerogatives.<strong>The</strong> Medical and SocialCoverageThis development will onlydeal with theacknowledgment ofincapacitatingconsequences in relationwith their possible link toservice. Although the 1955law provisions (imputabilitypresumption, reduction ofthe disability limit downto 10%) are systematicallyextended to overseasoperations, this has notavoided problemspertaining to theimputabilityacknowledgement inconnection with theexecution of service.In fact, certain casesconnected to this issuehave created a strongemotion in the militarycommunity. Althoughthe outcome of thesecases was in favor ofthe plaintiffs,the closing stages neededlengthy and fastidiousproceedings <strong>for</strong> situationsrather commonly facedby personnel duringoverseas operations.It is not the case ofreviewing these litigations ;it is just a matter ofstressing the difficulty toappreciate the connectionof certain activities with“ service ”.Two Situations Should beCarefully Scrutinized.<strong>The</strong> first one encompasseswhat we call “ day to dayactivities ”. Althoughthe service member is led“ to serve anywhere ”,he does not have the legalprotection recognizedby the Court of Cassationrecognized to employeescarrying out a mission(appeal n°285 dated July19, 2001 ; appeal n° 133dated April 2, 2003 ;Social Chamber ; “ butconsidering thatthe employee carrying outa mission benefits fromthe protection stated <strong>for</strong>thin article L.411-1 of theSocial Security Code duringthe duration of the missionhe carries out <strong>for</strong>the benefit of his employer,it does not matter whetherthe accident occurs duringa service connectedmission, or not, withthe exception <strong>for</strong> theemployer or the SocialSecurity to bring evidencethat the employee hadinterrupted his mission<strong>for</strong> a private reason ”).<strong>The</strong> second one coversrecreational activities,essentially tourism trips.This situation mayundoubtedly change fromone theater of operation toanother ; it cannot howeverbe ignored.It is considered that takinginto account the Court ofCassation jurisprudencein statutory texts and thedisability military pensioncode would enable toclarify the medical andsocial coverage <strong>for</strong>personnel on overseasoperations without, atthe same time, increasingcost to the government.<strong>The</strong> review commissionof the Military GeneralStatutes suggests to takeinto account theimputability presumptionfrom the start till the endof the mission ; it’s animprovement whichhowever does not go as faras the Court of Cassationjurisprudence.This contribution onlyaimed at evoking the legalsituation of personnelduring overseas operations; although the principleof commitment to suchoperations seems to bewell established,the consequences vis-à-vispersonnel seem moreblurred. Let’s hope thatthe proposals of the reviewcommission of the MilitaryGeneral Statutes will finda favorable echo. Maybewe could go further -allocate a specific legalstatute to overseasoperations.DOCTRINE # 04 14 SEPTEMBER 2004

doctrineIs there a Law of Warfare ?If war confronts us with a specific problem, it comes from its disproportionate, and barbarian nature. Just as afight between two men has a violent aspect without any rule, and any constraint..., when no police <strong>for</strong>cesintervene, in the same way, a declared war sets <strong>for</strong>ces in motion, which consequently overstep the mark of thewrong undergone or of the incurred threat. It is a “ savage all or nothing ”. This disproportion is certain, itwounds our innate sense of reason - and we claim that war is “ absurd ” ; it wounds our will <strong>for</strong> universal good -we claim it is a “ scandal ”. But, when you think about it, disproportion is not so much the sign of madness or ofcollective injustice as much as it is the proof of a lack of any institution, of higher wisdom, able to providemeasured solutions and to be able to impose them on on the belligerents. “ War is not a rightful necessity - it isneither metaphysical nor divine -. Nevertheless, the defense of a nation against an aggression infringing on itsrights, on its dignity, and on its safety, can legitimize this statement. <strong>The</strong> law of war acquires obvious nobility,insofar as it enables to safeguard international balance and universal peace from the tantrums and oscillationsof nations. ” 1Peace is a work of justice but it is also a work of <strong>for</strong>ce.<strong>The</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, we must initially deal with the concept of law within war ; then, we will deal with the fundamentalprinciples of this law.BY LIEUTENANT-COLONEL JÉRÔME CARIO, CENTER FOR FORCE EMPLOYMENT DOCTRINE (CDEF) LESSONS LEARNED DIVISION (DREX)ADC F. CHESNEAU/SIRPA TerreWhat is Law Within War ?Is there not a contradictionin the very terms when wedeal with “ law within waror the law of armedconflicts 2 ” ? Can weassociate to the term of lawa behaviour which seems tobe its denial ? 3 <strong>The</strong> paradoxis only apparent. Indeed,war, like trade, like themovement of people, -following the example ofany human activity - is anopportune chance toregulate it. “ After all, itshould not be more childishto codify the conduct ofhostilities between twoarmed groups than it is <strong>for</strong>road traffic ”. Thus, there isno inconsistency indealing with the “ Law ofarmed conflicts ”. 4Law within war is thus aset of principles and rulesof public international lawapplicable duringconflicts and whosepurposes are :- to protect and affirmthat non-combatants,civilians in particular,and out-of-actionsoldiers are treated withhumanity (Geneva Law),- to limit, even to prohibit,some warfare methodsand means, in order toprevent undistinguishedviolence and excessivesufferings (<strong>The</strong> HagueLaw).Sources <strong>for</strong> this law lie incustoms and internationalconventions. If thesecustoms go up rather far intime5, ..., conventions thatcodified them, as what wasthen called “ war law andcustoms ”, originate at thetime of the creation of theInternational Red Cross.This is when it producedthis legal corpus commonlyreferred to as humanitarianinternational law or law ofarmed conflicts. 6Today, it is thus a set ofnumerous andsophisticated internationaltreaties, which make up themain part of law within war.For this reason, their scopemust be evaluated with thecriteria and methodologysuitable <strong>for</strong> internationalSEPTEMBER 2004 15 DOCTRINE # 04

law. Thus, be<strong>for</strong>e affirmingthat such a rule applies to aparticular conflict, it isadvisable to check if theNations taking part in thisconflict are bound bythe treaty which statesthe rule and, in the event ofan affirmative answer, ifthey did not make anyreservations. For example,if the 1949 GENEVAConventions were ratifiedby almost all the Nations,it is neither true <strong>for</strong> theiradditional 1977 agreements- which bind only two thirdsof them to date - nor <strong>for</strong>the 1980 convention - whichbinds less than one thirdof them. 7“For us, French soldiers,the law of armed conflictsis a mandatory law, whichprevails over the rules ofnational law.” 8This flexible law applies tointernational wars only,namely mainly interstatewars, such as the Iraq - Iran(1980-1988), Iraq - Kuwait(1990-1991), Ivory Coast(2002-2003) or Iraq - Anglo-American coalition (2003 -...) conflicts ; nationalliberation wars, whichoppose a Nation to a<strong>for</strong>eign occupation poweror regime, such as theWestern Sahara (1975 -...)conflict ; internal conflictswith an interventioncharacterized by thecommitment of <strong>for</strong>eignarmed <strong>for</strong>ces, such as theVietnamese (1958 - 1975) orAfghan (1979 - 1989/2002)conflicts.the four GenevaConventions, (article 3,common to the fourconventions), - in the 1954<strong>The</strong> Hague Convention(article 19), - as well as atreaty that includes lessthan 20 articles, the 19772 nd additional agreement.<strong>The</strong>se texts state theminimal protectionstandards <strong>for</strong> the victims.Still it is necessary that aninternal armed conflictreach a certain scale <strong>for</strong>these provisions to apply,which is not the case if therebellious party does notcontrol a part of territory ordoes not have, at least, anorganized armed <strong>for</strong>ce.<strong>The</strong>se texts do not applya <strong>for</strong>tiori, either to situationsof internal disorders.Main Principles in LawWithin WarLaw within war relies onthe primacy of the victims’interests. In case of doubt,it means that it is necessarythat - between twobehaviors - the behaviorthat is most favorable tothe victims prevails. 9PROPORTIONALITYThis principle of priority tothe protection of the victimslies in the fact that this lawrelies less on the interstatereciprocity than on theunilateral obligationtowards the victims. 10In other words it is notbecause a warring factionviolates the “ jus in bello ”that the other party can giveup applying it ; reprisals aregenerally prohibited. 11Thus, on the one hand,there is law within war thatregulates the conduct ofhostilities by relying onthe conservation of Nations :it is the militaryrequirement 12 ; on the otherhand, there is a law ofassistance, which tends toprotect the victims : it is thehumanitarian principle. 13Apart from these generalprinciples, there areprinciples more specific tothe various phases of aconflict.Indeed the law of armedconflicts governs two typesof situations :- situations of confrontationwhere individuals areMILITARY REQUIREMENTexposed to the directeffects of hostilities ;- situations following aconfrontation whereindividuals findthemselves in the enemy’spower.Thus, the specific principlesof proportionality 14 and ofdiscrimination 15 are setdown as a requirement <strong>for</strong> amilitary commander whenplanning and conducting anoperation. <strong>The</strong>y have butone goal, to avoidunnecessary evils whileenabling a militarycommander to achieve thetasked mission, which thusresults into a militaryrequirement. This militaryrequirement may producecollateral damage or effectsthat are likely to be butaccidents.When understood andapplied in this way, the lawof armed conflicts is surelynot a “weapon againstsoldiers”. “Contrary to whatsome people wish or evenimagine, the law of armedconflicts should not beconsidered as a constrainton the conduct of themission; on the contrary, itcontrols it.” 16DISCRIMINATIONIn internal conflicts, muchmore frequent nowadays,such as the Yugoslavconflict, in its early phase(1990 - 1991), the conflictin Chechnya (1994 -...) or inLiberia (1989 -...), the lawof armed conflicts involvesnothing more than a trifleshare, - a provision inColLateralEffectsAVOIDING UNNECESSARY EVILSColLateralDamageDOCTRINE # 04 16 SEPTEMBER 2004

doctrineConclusion<strong>The</strong> implementation of law within war does not elude the weaknesses of the current international system, whose processstill largely relies on the willingness of Nations and thus un<strong>for</strong>tunately on the law of the strongest. Consequently, we canwonder why a Nation that deliberately violates international law by engaging in a war - unambiguously banished since theen<strong>for</strong>cement of the United Nations Charter, (purpose of the jus ad bellum) - would comply with the rules of the law ofarmed conflicts (purpose of the jus in bello) ?Actually, in spite of many serious violations, we cannot ignore that it also contributes to spare innumerable lives, eitherbecause the standards that it defends have been understood and accepted, or still by mutual interest, or finally out offear of international sanctions or disgrace.But <strong>for</strong> the law of armed conflicts to be complied with, the Nations must first of all commit themselves to become partiesto existing treaties and to carry out prescribed obligations.<strong>The</strong>n, <strong>for</strong> the law of armed conflicts to be known by all those that will have to en<strong>for</strong>ce it and to become part of nationallegislative systems, it is necessary that Nations take a range of measures or provisions.Two kinds of national measures are particularly important :- national legislations that Nations must pass to en<strong>for</strong>ce these treaties; “the higher contracting parties and parties toconflict must repress serious offences and take the necessary measures to put an end to all other infringements toconventions or to the present agreement which result from an oversight contrary to a duty to act.” 17- measures about the dissemination of Law of Armed Conflicts (DCA) and soldier training. “ <strong>The</strong> higher contracting partiescommit themselves to disseminate conventions and the present agreement in their respective countries and in particularto incorporate its study in military training syllabuses as much as possible, in peacetime as in periods of war. ” 18Thus, if <strong>for</strong>ce is necessary, “ it is necessarily controlled, i.e. anxious to save civilian populations and respectful of theadversary... Numerous are those that could think that law within war might be at the level of speech whereas action takesplace in the concrete realities of a quite different inspiration. It is a dangerous and criminal concept ”. 19Law within war or the principle of controlled <strong>for</strong>ce is thus necessarily essential to us ; <strong>for</strong> this reason, it must feed ourthinking, our training, our operational planning and our commitments.1G. de Nantes. War and deathpenalty. In the CRC in the 20 thcentury. March 1976.2 In a deliberate way, we willconsider that the concepts oflaw within war, humanitarianinternational law or law ofarmed conflicts <strong>for</strong>m the samelegal corpus.3 For CLAUSEWITZ : “ One couldnot introduce a moderatingprinciple into the philosophy ofwar without making nonsense ”.4 Eric DAVID. Principles of Law ofarmed conflicts. BruylantEdition. Brussels. 1999republication.5 Jerome CARIO. Law of armedconflicts or limitations to harm,in its regulations and means.Doctorate thesis in history -humanitarian international law.Nantes University, November2001.6 In 1864, following the workissued by Henri DUNANT - Amemory of SOLFERINO, thatNations adopt the first majormultilateral convention on lawwithin war : the GENEVAConvention dated August 22,1864 <strong>for</strong> the improvement ofthe fate of wounded soldiers.7 Lieutenant-Colonel JérômeCario. Law of armed conflicts.Editions Lavauzelle/CREC.July 2002.8 Article 55 of the 1958 -Constitution : “ <strong>The</strong> treaties oragreements regularly ratifiedor approved have, as of theirpublication, a higher authoritythan that of laws, on thecondition that, <strong>for</strong> eachagreement or treaty, it isapplied by the other party. ”See : (<strong>The</strong> principle ofreciprocity).9 In war, “ it is preferable towound rather than to kill and itis preferable to take somebodyprisoner rather than towound ”. ICRC (InternationalCommittee of the Red Cross)principle of humanity.10 “ <strong>The</strong> higher contractingparties commit themselves toabide by this convention andthis agreement and to en<strong>for</strong>cethem, in all circumstances. ”Article 1 common to the fourGeneva Conventions andarticle 1/1 of the1 st agreement.11 Vienna Convention on the lawof treaties, art. 60, paragraph 5.12 Military requirement : It is theprinciple which authorizes abelligerent to take all thenecessary measures thatwould be required to completean operation and that wouldnot be prohibited by the laws ofwar.13 <strong>The</strong> humanitarian principle : Itis the protection of noncombatantsin allcircumstances.14 <strong>The</strong> principle of proportionality• It is a principle of limitation<strong>for</strong> military operations :- It is not an unlimited right as<strong>for</strong> selecting the means toharm the enemy ;- It is the prohibition to inflictuseless sufferings ;- It is the prohibition to causeextended, durable and seriousdamage to the naturalenvironment.• It is also a principle ofprohibition or limitation ofcertain combat means ormethods :- Perfidy ;- <strong>The</strong> prohibition toexterminate survivors ;- <strong>The</strong> prohibition or theregulation of some weapons.15 <strong>The</strong> principle of discrimination- It is the distinction madebetween combatants andcivilian people:- It is the distinction madebetween military objectivesand civilian assets;- It is a rein<strong>for</strong>ced protection<strong>for</strong> some civilian assets;- Protected areas.16 Major General Bruno CUCHE.Symposium on Humanitarianinternational law and armed<strong>for</strong>ces. May 2000. Researchcenter of Saint-Cyr Academy.Editions PIR, Saint-CyrAcademy.17 “ G P I -86; G I-49 ; G II-50 ;G III-129 ; G IV-146 ”18 “ GI -47 ; G II-48 ; G III-127 ;G IV-144 ; GPI-83/1 ; H.CP-25. ”19 General Jean-RenéBACHELET. Short speechdelivered at the SIGEM.March 2001.SEPTEMBER 2004 17 DOCTRINE # 04

<strong>The</strong> Rules of Engagementin Ten Questions<strong>The</strong> notion of rules of engagement (ROE) remains <strong>for</strong> many people an object of questions. What doesthis expresion include, what is the use of these rules of engagement ? Where are they coming from ?What is their legal value ? This article has no other ambition than to provide some short elements ofanswers to these questions.BY COLONEL (QUARTER MASTER) FRANÇOIS MARTINEAU*, LEGAL AFFAIRS DIRECTORATEADC F. CHESNEAU/SIRPA TerreWhat are the Rules ofEngagement<strong>The</strong> joint glossary <strong>for</strong>the words and expressionsrelated to the operationnaluse of <strong>for</strong>ces defines themas “ Guidances released bya competent militaryauthority and specifyingthe circumstances and thelimits in which <strong>for</strong>ces will beallowed to open fire or keepfighting. ” However, anothertext often implemented bythe French armed <strong>for</strong>ces,NATO 1 MC 362, definesthem in a slightly differentway : “ <strong>The</strong> ROE’s areguidances released tomilitary <strong>for</strong>ces ( includingservice members ) whichdefine the circumstances,the conditions, the degreeand the manner in whichone has to respect, to beallowed, or not to use <strong>for</strong>ce,or to engage in behaviourwhich might be consideredas provocations. ”So, we are in the presenceof two definitions : the useof firearms in one case andthe use of <strong>for</strong>ce,understood in a largersense, in another. <strong>The</strong>sedefinitions reflect theirtime. <strong>The</strong> present Frenchdefinition is taken from theAAP-6 (NATO glossary),adopted in 1973, itselfinspired by the 1967American definition, allthese definitions datingfrom the Cold War era. <strong>The</strong>MC 362 definition as well asrecently adopted 2 others,show a larger concept : theuse of <strong>for</strong>ce includes theuse of weapons but alsoencompasses any measureleading to restrict individualliberties as well as actionsor measures that can beseen as aggressive orprovocative by a potentialadversary. <strong>The</strong>se definitionshave in common the factthat they have beenadopted <strong>for</strong> less than fiveyears. <strong>The</strong>y reflect theevolution of the missionsassigned to the military inthe framework of peacekeeping missions. Soldiersare increasingly requestedto substitute themselves topolice <strong>for</strong>ces. This leadsthem, <strong>for</strong> example, to carryout identity controls, todetain individuals or arrestwar criminals. This is thereason why the Armed<strong>for</strong>ces staff deemednecessary, to come closerto the recently adopteddefinitions, to givethoughts to the definitionof the ROE that will soonappear in the Joint doctrine<strong>for</strong> the use of <strong>for</strong>ce inexpeditionary operations -the result of a commonwork between the Armed<strong>for</strong>ces staff and the <strong>Legal</strong>affairs Directorate. Francewill then have at itsdisposal a catalog of rulesof engagement comparablewith those of NATO andthe EU, and interoperablewith them.Where are they ComingFrom ?<strong>The</strong> notion stemmed fromthe US Navy in the midfifties 3 . Why this navalorigin ? During the ColdWar, the US Navy ships, outat sea, might findthemselves facingharassment actions byWarsaw Pact ships 4 . It wasthere<strong>for</strong>e necessary to givethe commanders directionspermitting them to controlthe escalation risks duringpossible clashes withadverse fleets. <strong>The</strong> notionwas later used, in the earlysixties, by the US Air Forceelements stationed in SouthKorea and then by the USArmy.Of What Use are they ?<strong>The</strong> object of the rules ofengagement is to enablethe civilian or militaryauthority to master the useof <strong>for</strong>ce at the differentechelons of command ; andthis, depending on thelimitations imposed by thepolitical, military and legalrequirements. Bydetermining the conditions<strong>for</strong> the use of <strong>for</strong>ce, theypermit the commanders ofdeployed <strong>for</strong>ces to managecrisis situations in peaceDOCTRINE # 04 18 SEPTEMBER 2004

law which are the law of thearmed conflicts 10 and thelaw on human rights. <strong>The</strong>standards to be appliedmay vary depending on thenature of the crisis and itslevel of violence. <strong>The</strong>re<strong>for</strong>ethey are specified <strong>for</strong> eachoperation. Besides, thenational law continues toapply to the militarycomposing the <strong>for</strong>ce. So,under the article 113-6 ofthe Criminal Code and ,moreover, <strong>for</strong> the militarypersonnel, because of thearticles 59 and 68 of theCode of Military Justice, theFrench criminal law appliesto all the French citizensoutside the territory ofthe Republic. <strong>The</strong> laws of<strong>for</strong>eign states may,regarding the use of <strong>for</strong>ce,differ from the French law.In the hypothesis of amultinational operation onemust ensure that theimplementation of the rulesof engagement does notcontravene the French lawwhich prevails. <strong>The</strong>reference documents ofthe different organizations(NATO, European Union)envision the possibility thatthe states taking part in anoperation releasecomments or restrictionspermitting each state torespect its own law.What is their <strong>Legal</strong>Value ?<strong>The</strong> combination of therules of engagementbetween political, militaryand legal factors is a sourceof confusion about thevalue of these rules. Itwould be wrong to believethat the respect of the rulesof engagement of theinternational and nationallaws make themautomatically acquire theirvalue. <strong>The</strong> rules ofengagement must beconsidered as orders fromthe command or, interms of the CriminalCode, orders from the“ legitimateauthority ”. <strong>The</strong> <strong>for</strong>cein overseas operationis, in fact, employedunder the order of alegitimate authorityi.e. a competent publicauthority 11 .CCH J.J. CHATARD/SIRPA TerreConcretely, canthe rules ofengagementexonerate soldiers whoapply them from criminalresponsibility ? Article 122-4of the Criminal Code<strong>for</strong>esees, as a cause <strong>for</strong>exoneration of criminalresponsibility,the obedience to anindistinguishable illegalorder from the legitimateauthority. 12 Insofar asthe act prescribed by therules of engagement is notobviously illegal, theexecutor will see himselfexonerated of his criminalresponsability. <strong>The</strong>responsibility then weightson the drafter of the rules ofengagement. Respect ofthe rules of engagement bysubordinates contributesthere<strong>for</strong>e to their legalprotection.It is precisely to rein<strong>for</strong>cethe latter that the Directionof the legal affairsproposed, in the frameworkof the works of revision ofthe general status ofthe military, that be insertedin this text a dispositionestablishing the principlethat “ particular criminaldispositions pertaining tothe use of <strong>for</strong>ce by servicemembers outsidethe national territory are<strong>for</strong>eseen by the MilitaryCode of Justice ”. <strong>The</strong>sespecial dispositions might,in substance, establish that“ is not criminallyresponsible the soldier who,in the respect of the rules ofthe international law and inthe framework of a militaryoperation taking placeoutside the French territory,applies coercion measuresor uses armed <strong>for</strong>ce when itis necessary <strong>for</strong> theper<strong>for</strong>mance of themission ” 13 .* Chief of the office <strong>for</strong> the right ofarmed conflicts in the Directorate<strong>for</strong> the legal affairs of the Defenseministry .1 On Novembre 9 th 1999, the militaryCommittee ratified the documentMC 362, “ NATO Rules of engagement“ which states the procedureto adopt rules of engagement andprovides a catalog of these rules.2 Like the UN guidance “ Rules ofengagement <strong>for</strong> the UN peacekeeping operations (April 2002)(MD/FGS/020.0001) or the concept “Use of <strong>for</strong>ce <strong>for</strong> EU-led Military CrisisManagement Operations” ofthe European Union(ESDP/PESD/COSDP 342 datedNovember 20 th 2002).3 <strong>The</strong> first in<strong>for</strong>mal use of theexpression dates in November 1954with the release of the “ InterceptEngagement Instructions <strong>for</strong>the U.S. Navy ”.4 This explains why the French Navy,accustomed to operations andexercices in conjunction with NATONavies has been, historically,the first to be confronted with thatnotion.5 In 1982, a US Army study demonstratedthat out of 269 cases offriendly fires against ground <strong>for</strong>ces,99, or 37 % resulted from fires fromAir Force planes supposed to supportthem.6 Proportionality is the requirementthat the use of <strong>for</strong>ce will be limitedin intensity, duration and scope, towhat is necessary to stop and repelthe attack or the threat. Except asotherwise stated, minimal <strong>for</strong>ceincludes lethal <strong>for</strong>ce when it isnecessary. In war time, the rulesare more flexible than the rulesestablished <strong>for</strong> peace supportoperations.7 <strong>The</strong>re are however exceptions.So, with a deterrent goal, Francedeclared during the Iran-Irak war,that “ the French war ships willopen fire at the <strong>for</strong>ces which willrefuse to stop their attack on aneutral merchant ship whenFrench ships have received distresssignals. “8 However rules of engagement havebeen seen with guidances such as :“ looting is <strong>for</strong>bidden “, “ treat withhumanity all captured persons “, “denial of quarter is <strong>for</strong>bidden “.Mixing these permanent principleswithin the rules of engagementwith technical rules pertaining tothe operation may be confusing <strong>for</strong>the unit members who may givethem an identical value and “ <strong>for</strong>get“ the principles of the law of thearmed conflicts that would not havebeen reminded by the rules ofengagement.9 For the procedure adopted by theEuropean Union, see LCL Joram’sarticle devoted to operation “Artemis “.10 <strong>The</strong> law of the armed conflicts rulesthe use of the military <strong>for</strong>ce insituations of armed international ornon international conflicts. It limitsthe means and methods of combatthat may be employed by the belligerentparties. <strong>The</strong> use of <strong>for</strong>cecannot go beyond what is authorizedby this law.11 See Article 21 of the Constitution ofthe Fifth Republic about the assignmentof the military authorities. -law n°72-662 dated July 13th 1972general status the military of -Decree n°82-138, dtd 8 Feb 1982Attributions of the Chiefs of <strong>Staff</strong>.12 Article 122-4 para 2 of theCriminalCode : “ Is not criminally responsiblethe person who per<strong>for</strong>ms anact ordered by the legitimateauthority except if this orders areobviously illegal. “13 Report of the Commission incharge of the revision of the generalstatus of the military, chaired byM. Denoix de Saint Marc, datedOctober 29th 2003, pp. 15-17.DOCTRINE # 04 20 SEPTEMBER 2004

doctrine<strong>The</strong> Indispensable Cooperation Betweenthe Military Authority and the Military Policein Criminal MattersIn French law, the notion of crisis, defined as an intermediate situation between peace and war,has no legal existence. So France’s engagement outside the national territory occurs in theabsence of a specific legal framework. Crisis management is there<strong>for</strong>e kept in the French commonlaw to which must be added dispositions of international significance such as :1) the agreement about the status of the <strong>for</strong>ces which establishes, at least, a privilege of juridiction,2) the rules of engagement which, schematically, constitute the framework of the military actiondefined by the political authority.That way, any member of the French <strong>for</strong>ces operating or deployed in a <strong>for</strong>eign country, notably in amultinational operation, remains under the influence of these texts and of the French law. Since1999, the Armed <strong>for</strong>ces tribunal in Paris is the sole competent to take cognizance of thesecriminally litigious actions or omissions under the article 59 of the Military Justice Code (CJM).<strong>The</strong> district attorney of this tribunal is assisted by criminal police officers of the Armed <strong>for</strong>ces(OPJFA), professional soldiers from the Gendarmerie who serve with the military police and whohave as one of their missions to carry out criminal police duties within the armed <strong>for</strong>ces. As such,they ascertain the violations of all nature and report them to the competent magistrate.But the particular situation of the overseas operations imposes the cooperation of the militaryauthority who has some prerogatives in criminal matters and of the OPJFAs who must take intoaccount the legitimacy of the action.BY LIEUTENANT-COLONEL (QUARTER MASTER) P. JABOT, LEGAL ADVISOR OF THE COMMANDER, LAND COMMAND<strong>The</strong> Role of the MilitaryAuthority in CriminalMattersAs a general rule, themilitary authority has theability to take up theattorney’s summary. In thisframework, he has acertain competence <strong>for</strong>judgement.<strong>The</strong> Military AuthorityIn<strong>for</strong>ms the Attorney<strong>The</strong> article 40 para 2 of theCriminal Procedure Code(CPP) specifies that “ anyconstituted authority (...)who, in the exercise of hisfunction has the knowledgeof a crime or an offence isobliged to report it withoutany notice to the attorneyand to <strong>for</strong>ward to thismagistrate all thein<strong>for</strong>mations pertaining toit ”. It is under this articlethat the military authorityis obliged to in<strong>for</strong>m theProsecutor’s Office of allcrimes or offences in hisknowledge 1 . <strong>The</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e themilitary authority in<strong>for</strong>msthe attorney either directlyor through an OPJFA. Thatin<strong>for</strong>mation is subject to noregulation about the <strong>for</strong>m.This duty to in<strong>for</strong>m mustnot be confused with theindictment or the opinionof the minister and of theentitled authorities asestablished by the article698-1 of the CCP whichenable the militaryauthorities to directlyrequest the intervention ofthe Gendarmerie <strong>for</strong> aninvestigation, <strong>for</strong> examplein the framework of arobbery committed in amilitary facility.<strong>The</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e the militaryauthority is obliged toin<strong>for</strong>m the attorney of thecrimes, notably thosewhich might have occurredduring an engagement bythe Force. Consequently,the presence of OPJFAs inthis type of action is notmandatory but may favor,through the drafting ofhearing and observationreports, the protection ofthe interests of the militarywho would be undulysummoned by a victim. <strong>The</strong>military authority must alsoevaluate the act.SEPTEMBER 2004 21 DOCTRINE # 04

SIRPA Gendarmerie<strong>The</strong> Reviewing Authorityof the MilitaryCommanderOn October 27 th 1999 2 ,the Council of Stateconsidered thatthe administrative authorityis only responsible to reportto the attorney “concerningthe facts thatit comes to know inthe course of itsattributions, if these factsseem plausible and if itestimates that theyconstitute a sufficient basisto be in breach of the law,the implementation ofwhich it has <strong>for</strong> mission toensure. ” <strong>The</strong> militaryauthority is there<strong>for</strong>e notobliged to immediately,automatically, and withoutjudgement <strong>for</strong>ward thein<strong>for</strong>mation concerning anadverse incident. It mustexert its competence byinvestigating the case.<strong>The</strong> facts must besufficiently established, belinked to its competencearea and present apunishable or criminalnature. So it has somepower of evaluation and candecide that a violent actconducted in accordancewith the received ordersdoes not present apunishable or criminalnature. Of course, if needbe, the legal authoritywhich would have hadknowledge of the factsthrough another channel,can always estimatethat there is, in thecircumstance, a violationof the obligation to in<strong>for</strong>m.What would then bethe sanction ? <strong>The</strong>re are afew specific dispositionswhich constitute offencessuch as, <strong>for</strong> example, hidingor modifying any evidenceof a crime or of an offence 3 ,the threat or intimidationto deny the filing of acomplaint 4 , or yet witnessbribing 5 . Nevertheless thesecases are few in numbersand strictly defined.It appears there<strong>for</strong>e that themilitary authority is totallyable to judge the existenceor not of a characterizedoffence. Evidently, it is notabout hiding a criminaloffence, but it can have nofear to err on the wrongside as soon as it estimatesthat the action was notunlawful.Taking into Accountof the Legitimacy ofthe Action by the OPJFAs<strong>The</strong> intervention of theOPJFAs, legitimateaccording to the texts, mustallow to verify the legitimacyof the military action.An Intervention Justified bythe TextsMilitary Police personnel, aswell as the officers, NCOsand gendarmes under theircommand, practice militarycriminal police duties underthe dispositions of articles81 to 88 of the CJM andnotably article 84 para 4 ofthe CJM which specifies thatthe OPJFAs “ are bound ,towards the attorney, bythe obligations establishedby article 19 of the CPP ”which itself stresses that“ they are obliged to in<strong>for</strong>mthe attorney without anynotice about the crimes,offences and infringementsthey know about ”.<strong>The</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, the applicationof this article imposesupon them to in<strong>for</strong>m aboutany characterizedinfringement withoutnotice. If they are not partyto the military action, theywill be able to collect thein<strong>for</strong>mations likely to helpthem to evaluate the actthanks to the cooperationwith the military authority.In this context, the kind ofrelations maintained withthe command will, ofcourse, be determining.If an investigation isdecided, the relationsbetween the DistrictAttorney and the OPJFA willDOCTRINE # 04 22 SEPTEMBER 2004

e direct. Which will thenbe the elements ofevaluation ?- Is the act covered by selfdefence6 ?- Has the act beenperpetrated because ofnecessity in order tosafeguard a seriouslythreatened person orproperty 7 which includesnotably the persons orproperties having a specialstatus quoted in the rulesof engagement ?- Is there a cause <strong>for</strong>irresponsibility, the acthaving been “ ordered orauthorized by legal orregular dispositions ” or“commanded by thelegitimate authority,except if this act isobviously illegal 8 ”, inother words, have ordersbeen given ?<strong>The</strong> legitimate action mustfind its justification in theanswer given to thesequestions.<strong>The</strong> Legitimate ActionCovered by Lawcommanded and authorizedby the law or the regulation.So, the French law offers,depending on thecircumstances, means toaddress a legitimate action.Other rules of the law canalso be legitimatelyinvoked. <strong>The</strong> local criminallaw, if it exists, is certainlyan example that must betaken into account inoperations (searching orfrisking ) which are, inprinciple, conducted inaccordance with guidancefrom the Force commander.In this type of situation, aOPJFA, who has anindisputable know-how, cannevertheless find himselftaken aback with regards tothe details, and of whichrule to apply.Similarly, in the frameworkof a peace keepingoperation, relatively intensecombat phases may occur,imposing the respect ofthe rules and principles ofthe humanitarian law.<strong>The</strong> rules of theinternational law andthe law of the armedconflicts should there<strong>for</strong>ebe applied depending onthe events.Finally, the rules ofengagement will be invokedevery time orders have beengiven <strong>for</strong> the execution of alegitimate action ; thoughnot constituting a legalstandard, they are derivedfrom the internationalmandate given to the Forceand are validated by theFrench political power. <strong>The</strong>ydetermine the conditions ofexecution of the missionand, even if they are notreleased, they must be ableto “cover ” the militaryactions conducted in theframework of the mandate.<strong>The</strong> cooperation ofthe OPJFA and of themilitary authority or of itslegal advisor is there<strong>for</strong>enecessary to establish thelegitimacy of the act. It isindeed commonlyrecognized that in the law,legitimacy is oftensynonymous of legality.Besides, it must be stresseddoctrinethat until now no member ofa French <strong>for</strong>ce in operationhas been the object of acriminal sentence followingthe execution of a militaryaction. <strong>The</strong> centralizationof the affairs by the TAPsince 1999 shouldperpetuate this situationinsofar as the magistratesof this tribunal have todaya good knowledge ofthe difficulties whichthe military are confrontedwith when in overseasoperations.1 Instruction n°21420/DEF/SGA/DAJ/APM/EO dated October 23 th 2001.2 <strong>The</strong> Solana Case.3 Article 434-4 of the Criminal Code.4 Article 434-5 of the Criminal Code.5 Article 434-15 of the Criminal Code.6 Article 122-5 and 122-6 ofthe Criminal Code.7 Article 122-7 of the CriminalCode.8 Article 122-7 of the Criminal Code.9 “ <strong>The</strong> person who justifies to havebelieved he could legally per<strong>for</strong>man action, and that his act againstlaw was unavoidable, is not legallyheld responsible. ” Article 122-3 ofthe Criminal Code.Let us immediately discardthe action which might beconsidered as illegal ; it isthe case, <strong>for</strong> example, whenan operation would bebeyond the framework ofthe mandate of the Force.Here, the indicted soldiercould try to justify his act byweighing his unavoidableerror against the law 9 .In the case of a legitimateaction which unwillinglycaused inappropriatebehaviors, (<strong>for</strong> example :injury because of rashness),a precedent by the SupremeCourt of Appeal datedJanuary 5 th 2 000recognized a clause ofcriminal irresponsibility tothe faults unvoluntarilycommitted during theexecution of an actConclusion<strong>The</strong> OPJFA on the theater has there<strong>for</strong>e no reason to be systematically involved inthe military actions conducted by the <strong>for</strong>ces in the execution of their mission ;the military authority must play its role in criminal matters.But there is no reason either to try to systematically keep the OPJFA aside.<strong>The</strong> establishment of a confident relationship between the military and legalauthorities is required ; there should be no suspicion of hidden violations whichthe legal authority is responsible <strong>for</strong> investigating.For that, it certainly belongs to the legal advisor of the commander on the theater,in liaison with the military police commander to dissipate all the misunderstandingsand to see to it that the written reports be marked with some caution not to stir upinextricable disputes on the principles when no serious incident occured.SEPTEMBER 2004 23 DOCTRINE # 04

Overseas Operationsof the Bundeswehrin the Light of InternationalLaw and Constitutional LawSoldiers committed in overseas operations want to know the justification <strong>for</strong> amilitary intervention in which they take part. <strong>The</strong>y ask why they must part fromtheir families during a protracted period, even be put at risk of dying, beingwounded, displaced or tortured. Thus they claim a credible legitimating of a militarymission together with a legal cover <strong>for</strong> overseas operations. A lack of a legitimatestatus would result into a loss of motivation. Thus it is in the interest of theemployer-state to avoid it.BY BARON OSKAR MATTHIAS VON LEPEL, CHIEF OF THE “INTERNATIONAL LAW, CONSTITUTIONAL LAW,MILITARY LAW AND MILITARY DISCIPLINE” DEPARTMENT, MORAL AND CIVIC TRAINING CENTER OF THE BUNDESWEHRIn the past, a German soldierconsidered himself first as a militarycombatant who had to show hisabilities within the armed <strong>for</strong>ces toenable the State to assert itself. <strong>The</strong>legitimate aspect of his mission wasobvious. Today, he has to considerhimself as an instrument of thecurrent policy. In a new securitycontext, he contributes inimplementing political decisionsabroad. It is difficult <strong>for</strong> him tounderstand the meaning of hismission if he does not receive anyexplanation. Consequently, he mustbe in<strong>for</strong>med of the political goalssought after by the militaryintervention in which he takes part.Moreover, he must know the legallegitimate characteristic that justifiesthe pursuit of the objectives througha military commitment. Thislegitimating gives him the certainty toact on solid legal bases, in particularwhen he is not completely convincedby the official political arguments.This legitimating procedure relies onthe “citizen in uni<strong>for</strong>m” principle. Weask our soldiers to obey orders whilekeeping a critical mind. However, tohave a critical mind, soldiers need toknow the main reasons <strong>for</strong> theircommitment as well as the principlesof international law and constitutionallaw underlying their mission. Formilitary commanders who have toanswer questions from theirsubordinates, this requirement is anenormous challenge.In addition, the commanders ofsoldiers committed in operationsmust face other questions with legalimplications. Indeed, it is necessaryto explain to soldiers in whichconditions and how they have theright to resort to <strong>for</strong>ce. <strong>The</strong> use of<strong>for</strong>ce within the framework of anoperation, including overseasoperations, permit one to impose apolitical mission with military means.It is absolutely necessary to avoidthat a counter-productive use of <strong>for</strong>ceby some soldiers or a militarycommander when they carry out theirmissions jeopardizes the success ofthe operation.Consequently, only duly authorizedcoercive measures can be applied.Contrary to traditional warfare, notresorting to <strong>for</strong>ce is the rule andresorting to <strong>for</strong>ce is exceptional.Applicable law in operation is thusorganized around the questionsarising in this context.DOCTRINE # 04 24 SEPTEMBER 2004

<strong>for</strong>eign studiesCCH J.J. CHATARD/SIRPA TerreBoth aspects, the “right to carry outoperations” on the one hand and“applicable law in operation” on theother hand, constitute the primaryelements of any legal training withinthe framework of operationalplanning.<strong>Legal</strong> Bases <strong>for</strong> MilitaryOperations<strong>The</strong> Importance of LegitimatingOverseas Operations withInternational Law<strong>The</strong> framework set up by internationallaw <strong>for</strong> committing armed <strong>for</strong>cesoverseas is defined throughproscription standards. <strong>The</strong> mostimportant of which is the universal banto resort to <strong>for</strong>ce in internationalrelations. States are compelled tosettle their disagreements throughpeaceful means. To meet thisrequirement of the United NationsCharter, Member States havetransferred their prerogative to resortto <strong>for</strong>ce to the system of collectivesecurity of the United Nations. <strong>The</strong>yhave entrusted the Security Councilwith the safeguard of internationalsecurity. Only the Council is authorizedto inflict sanctions, should peace bethreatened or broken or should anaggression occur. Coercive measuresthat the Council imposes inaccordance with chapter VII ofthe United Nations Charter are notregarded as war, but as internationalpolice operations carried out withmilitary assets.<strong>The</strong> task of the Security Council whichconsists in authorizing independentStates to resort to <strong>for</strong>ce, is carried outthrough the adoption of resolutions bywhich Member States are entrustedwith a military intervention into <strong>for</strong>eignStates. Overseas operations of theBundeswehr currently in progress relyalso on such resolutions. Within theframework of international law theylegitimate the use of <strong>for</strong>ce byindependent States. By principle,Germany takes part only inmultinational military interventionsjustified by a mandate of the UnitedNations. Exceptions, such as those wefaced during the air war in Kosovo,require a specific legitimating byinternational law.Considering the problems moreclosely, we realize that some elementsare still missing <strong>for</strong> a comprehensiveexplanation <strong>for</strong> the Bundeswehroperations to be entirely covered byinternational law. In fact, theoperations of the Bundeswehr are alsobased on conventional internationallaw. As an example, let us considerthe SFOR commitment in Bosnia-Herzegovina.<strong>The</strong> SFOR - and previously the IFOR -mission results first of all from theprovisions of the Dayton peaceagreements. <strong>The</strong>y describe theobligations of <strong>for</strong>mer civil warbelligerents and the mission <strong>for</strong> thepeace supporting <strong>for</strong>ce whoseimplementation was entrusted toNATO. <strong>The</strong> Nations represented withinthe Security Council which signed thepeace agreements confirmed theimplementation of the treaty’sprovisions, negotiated with theconcerned belligerents and the BalkanStates ; it followed that any noncompliancewith these agreementswould result into coercive measures inaccordance with chapter VII of theUnited Nations Charter. To this end,resolution 1088 dated 12/12/1995 wasadopted. As far as its legitimatestanding regarding international law,the commitment of the Bundeswehrwithin the SFOR framework relies thusSEPTEMBER 2004 25 DOCTRINE # 04

on two elements : commoninternational law and conventionalinternational law.As the Bundeswehr takes part in aNATO multinational military operation,it is sometimes suggested that theSFOR commitment should also berelated to a NATO mandate under theterms of conventional internationallaw. This is not correct. <strong>The</strong> mandate ofthe Security Council obtained <strong>for</strong> theSFOR commitment by the States whichsigned the Dayton peace agreementswas not addressed to NATO, but tothe Member States of the UnitedNations. Thanks to their troops, theyhad to achieve the implementation ofthe Dayton peace agreements. <strong>The</strong>ywere tasked to take suitable measuresto carry out the tasks arising fromthe peace agreements with theassistance and within the frameworkof the organization mentioned inappendix 1-A.If the Security Council consideredNATO - expressly mentioned inthe Dayton agreements - when itdrafted its resolution, it dealt howeverat first with some nations whichcombined their <strong>for</strong>ces, capacities andresources on the account of theDayton agreements and which werealso NATO members. <strong>The</strong>y decided tocarry out the U.N. mandate togetherand to OPCON their available troopsto a NATO command. However thisprocedure did not trans<strong>for</strong>m thedecisions made by the NATO Councilinto a NATO mandate. Indeed, it wasa common decision made byindependent States in compliance withthe rules and procedures provided<strong>for</strong> in the NATO treaty. Thus themilitary operations of NATO <strong>for</strong>ces donot rely on a NATO Council decision asa legal base, but on agreementssettled within Alliance qualifiedorganizations binding NATO-membersovereign States under the terms ofinternational law.It was requested from the States notbelonging to NATO to also take part inthe NATO operation. To this end,NATO Member States authorizedthe NATO Council to conclude relevantagreements with the Nations thatdid not belong to the Alliance andwere ready to commit themselves tothe NATO operation.<strong>The</strong> Legitimating of OverseasOperations of the Bundeswehrby Constitutional LawContrary to other nations, whereasthe military operations of allthe Nations supplying troops <strong>for</strong> peacesupport missions rely on identicalprinciples of international law,Germany has some specificcharacteristics as regards the coverageof operations by constitutional law.At the end of the East-West blocksconfrontation and after Germany’sreunification, the federal governmentof that time took a cautious turntowards a policy of participation inmultinational military operations. Thispolicy caused a strong dispute withinGerman public opinion. It particularlyconcerned the commitment in Somaliain the early 90s. Parliamentaryopposition of that time regardedmilitary operations out of theframework of national and collectivedefense pertaining to the Alliance asanti-constitutional. It referred tothe text of paragraph 2 of article 87aof the fundamental Law : Apart fromdefense, armed <strong>for</strong>ces should becommitted only insofar as the presentfundamental Law authorizes itexpressly. As the very authorizationrequired by this constitution articleis not included in the fundamentalLaw, overseas operations ofthe Bundeswehr - according to whatwas said at the time - would not havecomplied with the fundamental Law.A political controversy followed,arousing a keen interest, and wascarried out with legal arguments. Thisintense public debate was concludedby a decision of the federalconstitutional Court dated 07/12/1994.It objected to the reservations aspresented. It justified its decision byreferring to paragraph 2 of article 24 ofthe fundamental Law, which authorizesGermany to adhere to a system ofcollective mutual security to safeguardpeace. According to the interpretationproposed by the Court, thisconstitutional provision alsolegitimates peace support operationswithin the framework of the UnitedNations.With this decision, the federalconstitutional Court made anotherdetermining decision, whichappreciably influenced politicalpractices : Any armed operationrequires the preliminary parliamentaryauthorization of the Bundestag -whatever it is : a pure peace supportmission or a mandate of the UnitedNations allowing coercive measures incompliance with chapter VII of the U.N.Charter. This interpretation of thefederal constitutional Court does notcome directly from the wording of thefundamental Law. It comes from theconstitutional tradition which attachesa great importance to Parliament - atradition that could be observed since1918, only excluding the state practiceof the IIIrd Reich.However, the parliamentaryprerogative of approval does notconfer any right to the Bundestag totake initiatives. This means that theBundestag does not have the right tocompel the federal government tolaunch an overseas operation. It canonly grant or refuse its assent to anyoverseas operation requested by thefederal government.Applicable law in operationRights and obligations <strong>for</strong> troops incountries of deployment result fromthe mission of the <strong>for</strong>ces committedoverseas, defined under the terms ofinternational law and constitutionallaw. Rules of engagement, stipulatedat international level and called “ Rulesof Engagement ” (ROEs), are thecommand and control tool thatenables political authorities to have aninfluence on the armed <strong>for</strong>ces toachieve the political goals. <strong>The</strong>se areOPORDs (Operation Orders) andintervention orders thanks to whichpolitical intentions can beimplemented in compliance with thelegal provisions in <strong>for</strong>ce. ROEs areused as a legal basis <strong>for</strong> ordersgoverning troop operations, should weDOCTRINE # 04 26 SEPTEMBER 2004