Upreti, Trilochan, International Watercourses Law and Its Application ...

Upreti, Trilochan, International Watercourses Law and Its Application ...

Upreti, Trilochan, International Watercourses Law and Its Application ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

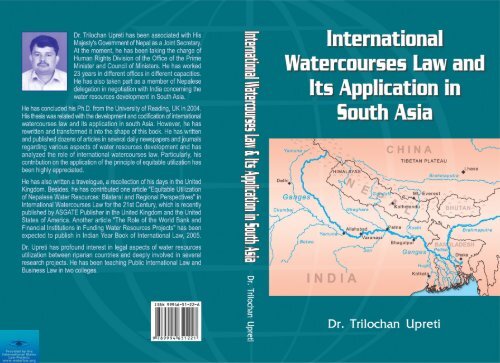

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong><strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong>in South AsiaDr. <strong>Trilochan</strong> <strong>Upreti</strong>Pairavi PrakashanDr. <strong>Trilochan</strong> <strong>Upreti</strong> has been working with His Majesty'sGovernment of Nepal as a Joint Secretary. At the moment, he hasbeen working in Human Rights division, in Office of the PrimeMinister <strong>and</strong> Council of Ministers. He has worked 23 years indifferent offices on different capacity. He has also taken part as amember of Nepalese delegation in negotiation with Indiaconcerning the water resources development in South Asia.He has concluded his Ph.D. from the University of Reading, UKin 2004. His thesis was related with the development <strong>and</strong>codification of international watercourses law <strong>and</strong> its applicationin south Asia. However, he has rewritten <strong>and</strong> transformed it intothe shape of this book. He has written dozens of articles in severaldaily newspapers <strong>and</strong> also in several journals regarding differentaspects of water resources development <strong>and</strong> has analyzed the roleof international watercourses law. Particularly, his contribution onthe application of the principle of equitable utilization has beenhighly appreciated.He has also written a travel story regarding his days in the UnitedKingdom. Besides, he has contributed one article "EquitableUtilization of Nepalese Water Resources: Bilateral <strong>and</strong> RegionalPerspectives" in <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> for the 21stCentury, edited by Surya P. Subedi, which is recently publishedby ASGATE Publisher in United Kingdom <strong>and</strong> the United Statesof America. Another article "The Role of the World Bank <strong>and</strong>Financial Institutions in Funding Water Resources Projects" hasbeen expected to publish in Indian Year Book of <strong>International</strong><strong>Law</strong>, 2005.Dr. <strong>Upreti</strong> has deep interest in legal aspects of water resourcesutilization between riparian countries <strong>and</strong> has been deeplyinvolved in several research projects. He has been teaching Public<strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> Business <strong>Law</strong> in two colleges.I II

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong><strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong>in South AsiaFor Pairavi PrakashanPublished by Managing Director Padam SiwakotiEdition : 2006© <strong>Trilochan</strong> <strong>Upreti</strong> 2006All rights reserved. No part of this publication may bereproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmittedin any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,photocopying, recording or otherwise without the priorpermission of the publisher <strong>and</strong> Author.<strong>Trilochan</strong> <strong>Upreti</strong> has asserted his right under theCopyright <strong>Law</strong>.Dr. <strong>Trilochan</strong> <strong>Upreti</strong>Price : NRs. 1000/–I.C. : 700US$ : 20£ : 15ISBN : Hard Bound : 99946-51-22-6Paperback : 99946-51-21-8Pairavi Prakashan(Publishers & Distributors)'M' House Ramshapath, Kathm<strong>and</strong>uP.O. Box: 9570, Tel: 4229233Printers :XVII XVIII

PrefaceIn this book, the author has attempted to present a comprehensivereview of the evolution of water law over the centuries. While doing so, theauthor has also attempted to outline the positive <strong>and</strong> negative aspects of theinternational treaties on boundary <strong>and</strong> transboundary rivers around theworld.Like any international law in general, the one covering water sectoralso constitutes mainly the State practices, judicial pronouncements,international coventions <strong>and</strong> scholarly writings. In this book, the author hascited a profusion of examples of water disputes across the world <strong>and</strong> theways they were attempted to resolve. The author, after doing a criticalanalysis of the four doctrines of international water law, viz. territorialsovereignty, territorial integrity, prior appropriation <strong>and</strong> equitableutilization, has considered the last doctrine as the best, one, for it has wideracceptance among the international community. The author seems to be anardent supporter of the principle of equitable utilization, because he hasemphasized in a number of places in the book that the principle would helpserve the interests of the riparian States <strong>and</strong> resolve their disputes in areconciliatory manner.The book also elaborates the water availability <strong>and</strong> its potential uses inSouth Asia for the economic development <strong>and</strong> environmental sustainabilityof the region. It attempts to outline the problems <strong>and</strong> suggest the equitableutilization of rivers as solutions to them.The concept of equity <strong>and</strong> the emerging concept of equitable utilizationin shared natural resources have been dealt with at length, citing judicatureof the <strong>International</strong> Court of Justice. The readers will get an opportunity tobe acquainted with numerous international treaties on water sharing that aresaid to be based on the principle of equitable utilization.The oft-quoted Columbia River Treaty between the USA <strong>and</strong> Canadais believed to be ideally based on the principle of equitable utilization. Inthis book, this treaty is broadly suggested as an ideal point of reference fortreaty on shared watercourses based on the principle of equitable utilization.However, it is important to note that the concerned riparian States tookdecades to reach an agreement on the Columbia River water sharing. Thetreaty was not signed overnight.Helsinki Rules are believed to be the basis for principle of equitableutilization. The rules state- "each basin State in entitled within its territory toget reasonable <strong>and</strong> equitable share in the benefical uses of the water oninternational drainage basin". However, it has not been easy to determinethe reasonable <strong>and</strong> equitable share from the viewpoint of various relevantfactors <strong>and</strong> is also not possible to formulate a general rule to assign weightsto these relevant factors.Equitable utilization of resource is based on equity, i.e., fairness,faithfulness <strong>and</strong> norms of distributive justice, <strong>and</strong> the interest of everyriparian State is taken into consideration. The author has recommended theprinciple of equitable utilization to be the most ideal rule for rivers of Nepalthat flows across India <strong>and</strong> Bangladesh. Although equitable utilization isarguably the best approach to achieve justice in sharing a watercourse <strong>and</strong> ispossibly the best possible means for resolving the conflicts, the question asto "how to make the principle operational" remains unanswered, <strong>and</strong> it willbe asking too much to expect an answer from the book.Nepal, as a co-riparian State, has border rivers <strong>and</strong> also trans-boundaryrivers. A regional or sub-regional treaty on sharing water is not yet inexistence. Nonetheless, we have the experience of entering into bilateralagreements on one border river <strong>and</strong> two transboundary rivers. So far asequitable utilization is concerned, agreements on trans-boundary riversnamely Koshi <strong>and</strong> G<strong>and</strong>ak Agreements in no way illustrate the principle ofequitable utilization, whereas the agreement of border river, namelyMahakali Treaty, reflects the principle of equitable distribution to a greaterextent. However, it is important to note that the Mahakali Treaty hasascertained the equitable sharing only for the water that will be augmentedfrom the development of Pancheswore Multipurpose Project <strong>and</strong> not for thenatural flow of the river. This is owing to the integration of SardaAgreement in Mahakali Treaty. Nevertheless, Mahakali Treaty could be theframework treaty for the equitable sharing of water of border rivers, ifimplemented with good faith <strong>and</strong> sincerity.Nepal without a delay needs to develop its strategy <strong>and</strong> framework forthe equitable sharing of watercourses. In doing so, she should adoptdifferent approaches for border rivers <strong>and</strong> trans-boundary rivers. Althoughthe book is comprehensive on principle of equitable sharing, it has yet toaddress the issues adequately in the context of Nepal <strong>and</strong> her rivers.The legal aspect of India's River Linking Project has been discussed inthe book in terms of her national <strong>and</strong> international dimensions both asthreats <strong>and</strong> opportunities to the smaller neighbouring countries. The bookgives quite an insight on the project for those interested in the region's waterresources.All in all, it is a very comprehensive work dealing with water issuesfrom the naitonal, regional <strong>and</strong> global st<strong>and</strong>points. The book givessignificant information on Nepal's position on water resources. The bookseems to have a number of repetitions of some of the issues, which perhapswill be done away with in the later editions.25 December 2005-12-25 (Mahendra Nath Aryal)SecretaryXVII XVIII

PrefaceSouth Asia has been remain one of the poorest area of the worlddespite the fact that immense water resource available here has notbeen fully used for the beneficial use of countries of this area. Ithas been identified that utilisation of these resources for thepoverty alleviation, infrastructure development <strong>and</strong> also for thelivelihood of people is of utmost required. However, even in thiscircumstance states are not moving forward to end their suspicion,bitterness <strong>and</strong> move ahead for the end of this cause by this means.This book has critically analysed the root cause of different views<strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>s of these nations <strong>and</strong> demonstrates how states in anotherpart of the world have been able to settle their divergent views <strong>and</strong>utilised shared waters for their mutual benefits. In doing so,evaluation of the law <strong>and</strong> practice developed so far has been made<strong>and</strong> how such law can be applied in south Asia has beenrecommended. Basically, critical analysis of international waterlaw <strong>and</strong> its application in south Asia is the major objective of thisbook.Fresh water is an indispensable part of the hydrosphere <strong>and</strong> theterrestrial system. Water is a finite resource for which there is nosubstitute; its total volume cannot be increased <strong>and</strong> no living thingcan exist without it. Global water usage is becoming unsustainableat present levels, which are still rapidly increasing due to theworld’s swelling population, <strong>and</strong> per capita usage that isincreasing with prosperity. The other issue of great concern is theuneven availability <strong>and</strong> unsustainable use of water, exacerbated byproblems such as pollution, deforestation <strong>and</strong> desertification.Indo-Nepalese water relations are used as a case study.To date, most problems associated with water use <strong>and</strong> itsallocation have been resolved through negotiations, agreements,<strong>and</strong> judicial pronouncements, assisted by experts in this field, <strong>and</strong>by reference to international customs <strong>and</strong> state practices. Althoughsome of these practices – those which are unanimously recognisedby the international community – have taken the shape ofcustomary international law, many related issues still remaincontentious, particularly in the developing world. There is still noone authority able to agree a universal definition ofequity/equitable utilisation <strong>and</strong> how this is to be reconciled withthe ‘no harm’ rule, <strong>and</strong> in the meantime, state practice has led to avariety of resolutions.The notion of equity is generally agreed to imply that nationsrepresenting the weak, poor <strong>and</strong> vulnerable should receivepreferential treatment by means of concessions made by the richernations <strong>and</strong> even by the richer developing state. This concept iswell exemplified by the Millennium Development Goal <strong>and</strong> DebtRelief Programmes, amongst other measures. The problems ofvulnerable countries such as Nepal must be overcome in aconstructive, effective <strong>and</strong> prudent manner, by means of greaterinternational co-operation based on the elements of equity, <strong>and</strong>requiring a reversal of the present policies of the World Bank <strong>and</strong>the richest industrial nations. This book has shown that the rule ofequitable utilisation provides the ability to resolve conflicts in awin-win manner, including in the Indo-Nepalese context.There are very many people who have significantly contributed tothis studies but it is not possible to mention all of them. However,my wife Mrs Puspa Devi <strong>Upreti</strong> has provided me source offunding, inspiration <strong>and</strong> needful help in completing my PhD in theUnited Kingdom <strong>and</strong> the book is based on these four years hardwork. Professor S. P. Subedi, Dr Chris Waters, Dr Duncan French,<strong>and</strong> Mr Damodar Bhattarai contribution in this undertaking shouldbe acknowledged. If this book contribute, even little, in creatingconducive environment for making broader consensus amongnations of south Asia <strong>and</strong> to the academic circle in their betterunderst<strong>and</strong>ing about this complex area, the author would considerthat the effort has been succeeded.In spite of my sincere effort there could be lacking <strong>and</strong>shortcoming <strong>and</strong> any comment <strong>and</strong> criticism in this regards will beheartily welcomed.23 December, 2005 - Dr. <strong>Trilochan</strong> <strong>Upreti</strong>XVII XVIII

<strong>International</strong> Treaties <strong>and</strong> other DocumentsConvention relating to the Development of Hydraulic Poweraffecting more then one State <strong>and</strong> Protocol of signature,Geneva, 9 December 1923.Convention on <strong>Law</strong> of Non-Navigational Uses of <strong>International</strong><strong>Watercourses</strong>, 21 May 1997.Convention on the Protection <strong>and</strong> Use of Transboundary<strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> Lakes, Helsinki, 17 March1992.<strong>International</strong> Regulation Regarding the Use of <strong>International</strong><strong>Watercourses</strong> for Purposes other than Navigation, Declarationof Madrid, 20 April 1911.The Convention <strong>and</strong> Statute on the Regime of NavigationalWaterways of <strong>International</strong> Concern, Barcelona, 20 April,1921.The Helsinki Rules on the Uses of the Waters of <strong>International</strong>Rivers, Helsinki, February 1966.Resolution 33/87 on Cooperation in the Field of theEnvironment Concerning Natural Resources Shared by Two orMore States, New York, 15 December 1978.1. Table of Bilateral Treaties1. Convention between Norway <strong>and</strong> Sweden on CertainQuestions Relating to the <strong>Law</strong> on <strong>Watercourses</strong>, signed atStockholm on 11 May 1929.2. Convention Regarding the Determination of the LegalStatus of the Frontier between Brazil <strong>and</strong> Uruguay signedat Montevideo on 20 December 1933.3. Treaty between Great Britain <strong>and</strong> the United StatesRelating to Boundary Waters, <strong>and</strong> Questions arisingbetween the United States <strong>and</strong> Canada signed atWashington, 11 January, 1909.4. Treaty between the United States <strong>and</strong> Mexico relating tothe utilization of the waters of the Colorado <strong>and</strong> TijuanaRivers <strong>and</strong> of the Rio Gr<strong>and</strong>e (Rio Bravo) from FortQuitam, Texas, to the Gulf of Mexico, signed atWashington on 3 February1944, <strong>and</strong> supplementaryProtocol, signed at Washington on 14 November 1944.5. Exchange of Notes between His Majesty’s Government inthe United Kingdom <strong>and</strong> the Egyptian Government inRegard to the Use of the Waters of the River Nile forIrrigation Purposes, Cairo 7 May 1929.6. Agreement between the United Arab Republic <strong>and</strong> theRepublic of Sudan for the full Utilization of the Nilewaters, signed at Cairo on 8 November 1959.7. Treaty between India- Pakistan Regarding the Use of theWaters of the Indus, signed at Karachi on 19 September1960.8. Treaty between the United States of America <strong>and</strong> CanadaRelating to Co-operative Development of the WaterResources of the Columbia River Basin, signed atWashington, 17 January 1961.9. Agreement between the Government of Nepal <strong>and</strong> theGovernment of India on the G<strong>and</strong>ak River Irrigation <strong>and</strong>Power Project, signed at Kathm<strong>and</strong>u on 4 December 1959.10. Agreement between the Government of India <strong>and</strong> theGovernment of Nepal on the Kosi Project, signed atKathm<strong>and</strong>u on 25 April 1954.XVII XVIII

11. The Treaty on the Lesotho-Highl<strong>and</strong> Water Project 1986,Lesotho-South-Africa.12. The treaty of the utilisation of the Parana River, Gauirafalls <strong>and</strong> Ygazu River, 1973 Paraguay-Brazil (ITAIPU).13. The Treaty of Peace 1994, Israel <strong>and</strong> Jordan.14. The Treaty on Sharing of the Ganges Waters at Farakka1996, India-Bangladesh.15. The Integrated Treaty on the Sharing of Mahakali River1996, Nepal- India.2. Table of Multilateral Treaties1. The Treaty for Amazon Co-operation, 1978 Bolivia-Brazil-Columbia-Guyana-Peru-Surinam <strong>and</strong> Venezuela.2. Agreement on the Environmentally Sound Management ofthe common Zambezi River System 1987 Angola,Botswana, Congo, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius,Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa,Swazil<strong>and</strong>, Zimbabwe, Tanzania <strong>and</strong> Zambia.3. Agreement for the Sustainable Development of theMekong River Basin, 1995 Thail<strong>and</strong>, Laos, Cambodia <strong>and</strong>Vietnam.Table of Cases1. Decided by <strong>International</strong> Courts/ Tribunals1. The case relating to the territorial jurisdiction of the<strong>International</strong> Commission of the River Oder, 1929 (PCIJ).2. The Diversion of Water from the Meuse 1937 (PCIJ).3. The Gabcikovo-Nagymaros Case 1997 (ICJ).4. Helm<strong>and</strong> River delta case 1872 <strong>and</strong> 1905 (Arbitration).5. Lake Lanoux case 1857(Arbitration).6. Gut Dam case 1968 (Arbitration).7. The Trail Smelter case 1938-1941(Arbitration).2. Major cases decided by municipal courts.1. Kansas versus Colorado 1902 & 1907.2. Wyoming versus Colorado 1936 & 1940.3. New Jersey versus New York 1931.4. Connecticut versus Massachusetts 1931.5. The Krishna River Dispute, 1961.6. The Narmada River Water Dispute, 1978.7. The Godawari River Water Dispute, 1980.8. The Punjab-Rajasthan-Haryana Water Dispute 1986.9. The Tungabhadra River Dispute 1944.10. The Muskhund Dam project Dispute 1965.11. The Bajaj Sagar Dam Project 1966.12. The Zwillikon Dam case 1878.13. The Leith River case, 1913.14. Societe Enerfie Electrique verusa Compaynia ImpreseElectriche Liguri 1939.15. Wurttemberg <strong>and</strong> Prussia versus Baden case 1927.XVII XVIII

ADBAJILAus.JILAYBLADPILALCCASEANAGOAInt.ABABYBILCYILCJIEL&PCERDSCBRCLJDJILDVCDPREP&LEEZECAFEESCAPECEELRFDIGEFFAOGYBILGATTGSPGIELRGIFGOIAcronymsGSP General System of PreferenceGAP Guneydogu Anadolu Projesi (Greater AntoliaAsian Development BankProject)American Journal of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>HILJ Harvard <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong> JournalAustralian Journal of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>HMG/N His Majesty’s Government of NepalAustralian Yearbook of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>HSC High Seas ConventionAnnual Digest of Public <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>HHDC Himalayan Hydro Development CorporationAsian African Legal Consultative committeeICJ <strong>International</strong> Court of JusticeAssociation of South East Asian NationsIDA <strong>International</strong> Development AssociationAfrican Growth <strong>and</strong> Opportunity ActILM <strong>International</strong> Legal MaterialsInter-American Bar AssociationILC <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong> CommissionBritish Yearbook of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>ILA <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong> AssociationCanadian Yearbook of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>IBWC <strong>International</strong> Boundary <strong>and</strong> Water CommissionColorado Journal of <strong>International</strong> Environmental ICCPR <strong>International</strong> Covenant of Civil <strong>and</strong> Political<strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> PolicyRightsCharter of Economic Rights <strong>and</strong> Duties of States IWL <strong>International</strong> Water <strong>Law</strong>Canadian Bar ReviewILWP <strong>International</strong> Water <strong>Law</strong> ProjectCambridge <strong>Law</strong> JournalISNT Informal Single Negotiation TestDenver Journal of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>IWC <strong>International</strong> WatercourseDamodar Valley CorporationIPP Independent Power ProducerDetail Project ReportILR <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong> ReportsEnvironmental Policy & <strong>Law</strong>IJC <strong>International</strong> Joint CommissionExclusive Economic ZoneICLQ <strong>International</strong> <strong>and</strong> Comparative <strong>Law</strong> QuarterlyEconomic Commission for Asia <strong>and</strong> the Far East Int AmBA Inter-American Bar AssociationEconomic <strong>and</strong> Social Commission for Asia <strong>and</strong> IJIL Indian Journal of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>PacificIse. LR Israel <strong>Law</strong> ReviewEconomic Commission for EuropeIMF <strong>International</strong> Monetary Fundthe Environmental <strong>Law</strong> ReporterINHURED- Institute of <strong>International</strong> Human Rights,Foreign Direct InvestmentEnvironment <strong>and</strong> DevelopmentGlobal Environment FacilityIWRA <strong>International</strong> Water Resources AssociationFood <strong>and</strong> Agriculture OrganisationKCC Karnali Co-ordination CommitteeGerman Yearbook of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>ISNT Informal Single Negotiation TextGeneral Agreement on Tariffs <strong>and</strong> TradeIPP Independent Power ProducerGeneralised System of PreferenceIDA <strong>International</strong> Development AssociationGeorgetown <strong>International</strong> Environmental <strong>Law</strong> LOSC <strong>Law</strong> of the Sea ConferenceReviewLNTS League of Nations Treaty SeriesGlobal Infrastructure FundLDC Least Developed CountriesGovernment of IndiaPCIJ Permanent Court of <strong>International</strong> JusticeXVII XVIII

MFN Most Favoured NationsMOWR Ministry of Water ResourcesMJIL Melbourne Journal of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>MDG Millennium Development GoalMD Managing DirectorMIGA Multilateral Investment Guarantee AgencyNAFTA North American Free Trade AgreementNRJ Natural Resources JournalNEA Nepal Electricity AuthoritySADC South Africa Development CommunitySCIP St<strong>and</strong>ing Committee for Inundation ProblemsSTABEX Stabilisation of Export EarningNYBIL Netherl<strong>and</strong>s Yearbook of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>UNCIW United Nations Convention on Non-Navigational Use of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong>NIEO New <strong>International</strong> Economic OrderNEA Nepal Electricity AuthorityNLR Nepal <strong>Law</strong> ReviewODA Overseas Development AssistanceOD Operational DirectiveOP Operational PoliciesBP Bank ProcedureOAS Organisation of American StatesPMP Pancheswar Multipurpose ProjectPPA Power Purchase AgreementRs RupeesSAARC South Asian Association of RegionalCooperationSARI South Asia Regional InitiativeSAGQ South Asia Growth QuadrangleSAPP South African Power PoolSMEC Snowy Mountain Electric CompanySASE South Asia Sub-Regional EconomicCooperationTVA Tennessee Valley AuthorityVJIL Virginia Journal of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>WTO World Trade OrganisationWCD World Commission on DamsWDM World Development MovementWRC Water Resource CommitteeWB the World BankWSSD World Summit on Sustainable DevelopmentWECS Water <strong>and</strong> Energy Commission SecretariatWWC World Water CouncilWI Water <strong>International</strong>YBILC Yearbook of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong> CommissionUDHR Universal Declaration of Human RightsUNC United Nations ConventionUNGA United Nations General AssemblyUNCED United Nations Conference on Environment <strong>and</strong>DevelopmentUNCHE United Nations Conference on HumanEnvironmentUNEP United Nations Environment ProgrammeUNDP United Nation Development ProgrammeUSAID United States Agency for <strong>International</strong>DevelopmentUNTS United Nations Treaty SeriesUCLR University of Colorado <strong>Law</strong> ReviewUNCTAD United Nations Conference on Trade <strong>and</strong>DevelopmentUSSR Union of Soviet Socialist RepublicsUTLJ University of Toronto <strong>Law</strong> JournalXVII XVIII

GlossaryMap of the Ganges BasinThe following terms are widely used in the south Asian Subcontinent<strong>and</strong> are defined for ease of reference:1. Bigha: A unit for the measurement of l<strong>and</strong> in Nepal. OneBigha is equal to 0.6772 hectare.2. Crore: A unit of accounting equivalent to 10 million.3. Cumec: Cubic metres per second (one cumec equals 8.107acre-feet).4. Cusecs: cubic feet per second.5. One cubic metre equals 33.315 cubic feet.6. 10,000 cubic metres equals one hectre-metre7. One hectre-metre equals 8.107 acre-feet.8. One cumec equals 35.32 cusecs.9. One litre is equals to 0.22 gallons.10. Kharif: Monsoon crop.11. Lakh: A unit of accounting equals to one hundredthous<strong>and</strong>.12. MAF: Million acre feet.13. Rabi: Winter crop.14. Rs: Rupees, the currency of India, Nepal <strong>and</strong> Pakistan,with a different value in each country.15. The river known in India <strong>and</strong> Nepal as the Ganga is knownin Bangladesh as the Ganges.XVII XVIII

- Preface III- Preface V- Table of <strong>International</strong> Treaties VII- Table of Cases X- Acronyms XI- Glosory XV- Map of theGanges Basin XVI- Table of Content XVIITable of ContentsChapter- OneIntroduction1.1 Significance of Water 11.2 Uneven Availability <strong>and</strong> Scarcity 41.3 Emerging Principles 61.4 Challenges Ahead 101.5 Structure of the Book 13Chapter- TwoDevelopment <strong>and</strong> Codification of<strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong>2.1 Introduction 162.2 Sources of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> 182.2.1 Earliest Stage of Development of IWC 182.2.2 The United States 202.3 Water Disputes 252.3.1 Inter-State Water Dispute in India 252.3.2 Development in European States 322.4 <strong>International</strong> Judicial <strong>and</strong> Arbitral Decisions 362.4.1 Helm<strong>and</strong> River Delta Case 372.4.2 Trail Smelter Case 392.4.3 Lake Lanoux Case 412.4.4 Gut Dam Case 432.5 PCIJ <strong>and</strong> ICJ Decisions 442.5.1 River Oder Case 442.5.2 The Diversion of the Meuse Case 472.5.3 Gabcikovo-Nagymaros Case 482.6 Scholarly Contributions 512.7 State Practices 542.7.1 Boundary Water Treaty 572.7.2 The Colorado Treaty 592.7.3 The Nile Treaty 602.7.4 The Indus Water Treaty 622.7.5 The Columbia River Treaty 632.7.6 Lesotho-Highl<strong>and</strong> Treaty 652.7.7 Amazon Cooperation 662.7.8 Southern African Development 662.7.9 Treaty between Paraguay <strong>and</strong> Brazil 672.7.10 The Treaty of Peace 682.7.11 Mekong River Treaty 692.7.12 Ganges River Treaty 702.8 The Impact of Water Issues on Bilateral Relations 712.9 <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Reform Efforts 772.9.1 The Helsinki Rules on the Use of theWaters of <strong>International</strong> Rivers, 1966 <strong>and</strong> ILA 772.9.2 <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Commission 802.9.3 UNCIW, 1997 902.9.4 The Institute of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong> 952.9.5 Some Other Institutions 962.10 Some UN Resolutions 982.11 Conclusions 100XVII XVIII

Chapter- ThreeEquitable Utilisation3.1 Principles of <strong>International</strong> Water <strong>Law</strong> 1033.1.1 Absolute Territorial Sovereignty 1033.1.2 Territorial Integrity 1043.1.3 Prior Appropriation 1063.1.4 Equitable Utilisation 1083.2 The Rule of Equitable Utilisation in IWL 1093.3 Procedural <strong>Law</strong> 1173.3.1 The Duty to Consult <strong>and</strong> Negotiate 1183.3.2 Discharge of Duty 1213.4 Origin <strong>and</strong> Development of Equity 1253.5 Types of Equity 1283.6 The Role of Equity in <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong> 1313.6.1 Unjust Enrichment 1343.6.2 Estoppel 1363.6.3 Acquiescence 1383.6.4 Ex Aequo Et Bono 1393.7 Equity for Scarce Resource Allocation 1383.7.1 Corrective Equity in Tradeing Arrangements 1413.7.2 Corrective Equity as Analysed toContinental Shelf Allocation 1433.7.3 Broadly Conceived Equity inContinental Shelf <strong>Application</strong> 1453.7.4 Broadly Conceived Equity inConventional Arrangements 1493.7.5 Common Heritage Equity 1513.8 Equity: an Integral Aspect of SustainableDevelopment 1543.9 Drainage Basins <strong>and</strong> Diversion of Waters 1603.10 The Right of a State to Utilise Water in itsown Territory 1633.11 Water as a Political Weapon 1673.12 Recent Developments on Equitable Utilisation 1693.13 The Role of Joint Commissions in IWC 1713.14 Conclusions 175Chapter- FourProspects <strong>and</strong> Problems ofNepalese Water Resources4.1 Introduction 1804.2 Potential of Nepalese <strong>Watercourses</strong> 1834.3 History of Water Resource Development:Indo-Nepal Relations 1874.4 Bilateral Relations with India 2004.5 Impact of Bilateral Relations in the WaterResources Sector 2064.6 Negotiations on Water Resources Projects 2084.7 Associated Multi-Disciplinary Complications 2094.8 Problems <strong>and</strong> Prospects of Nepalese Water Resources 2114.9 Projects of Bilateral Interest 2174.10 The Tanakpur Controversy 2214.11 Issues of Downstream Benefits 2234.12 Regional Co-operation 2354.13 Problems <strong>and</strong> Prospects of Water ResourcesDevelopment 2404.14 Conditions for Funding Imposed by the WorldBank <strong>and</strong> the Other Donors 2434.15 Conclusions 252Chapter- FiveIndia's River Linking Project5.1 Introduction 2575.2 Magnitude of the Problem 2585.3 Legal Issues Involve in the River Linking Project 2635.4 Concern of Neighbours 2705.5 Diversions Around the Globe 2745.6 Conclusions 275XVII XVIII

Chapter- SixConclusions <strong>and</strong> Recummendations6.1 Conclusions 2786.2 Summary of Findings 2786.3 Implications of water Scarcity 2836.4 Changing Perspectives 2866.5 Implications <strong>and</strong> Future Research 288• Appendixes 292- Appendix- 1 292- Appendix- 2 304- Appendix- 3 312- Appendix- 4 320- Appendix- 5 344• Bibliography 354•XVII XVIII

Introduction / 1 2 / <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong> in South Asia1.1 Significance of WaterChapter- OneIntroductionWater is a key element for the existence of all kinds of life.Early civilisations in Mesopotamia, Egypt, India <strong>and</strong> Chinaemerged on the banks of different rivers. 1 Water also hasimportant implications for most religions of the world. 2 TheGanges, for example, is considered holy by millions of Hindus.Thus, not surprisingly, when Saint Narad met the great IndianKing, Yuddhistira, his greeting was directly related to water: "Ihope your realm has reservoirs that are large <strong>and</strong> full of water,located in different parts in the l<strong>and</strong>, so that the agriculture doesnot depend on the caprice of the Rain-God". 3Water was equally important in the western world; twomillennia ago, the eminent Greek Philosopher, Pinder, said thatthe "best of all things is water". 4 Italian scholar Leonardo daVinci said "water is the driver of nature." 5 Life is impossiblewithout water, <strong>and</strong> it has been reported that the human bodyconsists of between 60 to 80% water by weight, depending1 D. A. Caponera (ed), The <strong>Law</strong> of <strong>International</strong> Water Resources,Rome: Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO), Legislative study No.23, 1980, p. 6.2 A. K. Biswas, "Water for Sustainable Development of South <strong>and</strong>Southeast Asia in the Twenty First Century” in A. K. Biswas & T.Hashimoto, (eds), Water Resources Management Series 4: Asian<strong>International</strong> Waters: From Ganges -Brahmaputra to Mekong, OxfordUniversity, 1996, p. 5.3 Ibid.4 Ibid.5 Ibid.upon the individual. 6 Thus it is quite natural for states, theprincipal actors of international relations, 7 to wish to safeguardtheir interests in fresh waters from the potentially diverginginterests of other riparian states, <strong>and</strong> to reconcile their interests(insofar as this may be possible). In the present context ofburgeoning population sizes, 8 <strong>and</strong> increasing dem<strong>and</strong> for scarcewater resources, if this problem is not properly identified,addressed <strong>and</strong> resolved, there is a strong possibility of conflictsthreatening international peace <strong>and</strong> security. 9It may be useful at this point to provide a brief overview of theavailability of water resources in its different forms. Thevolume of earth's water supply is approximately 326 millioncubic metres. Of this, 97.5% is salt water (with 71% of theearth's surface being covered by seawater) <strong>and</strong> 2.5% is freshwater (8 million cubic metres). Of this fresh water, 0.4% is onthe surface <strong>and</strong> in the atmosphere, 12.3% is underground, <strong>and</strong>87.3% is in the polar ice caps <strong>and</strong> in glaciers. 10 Freshwaterresources are an essential component of the earth's hydrosphere<strong>and</strong> an indispensable part of all terrestrial ecosystems. Thefreshwater environment is characterised by the hydrologicalcycle, 11 including floods <strong>and</strong> droughts, which in some regions6 S. C. McCaffrey, The <strong>Law</strong> of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong>: Non-Navigational Uses, Oxford University, 2001, p. 3.7 Lotus Case in PCIJ series A/B vol. 3, p. 17 & the Corfu Channel Casein ICJ Reports 1949, p. 35.8 Supra note 6, p. 5, the population of the world in 1950 was 2.5 billion;it has doubled in less than forty years <strong>and</strong> the United Nations forecaststhat it could reach some 9 billion by 2050.9 V. Narayan, "‘Water’ the Oil of Next Century" TERI Newswire III,(19), New Delhi: October 1997, pp. 1-5.10 P. Wouters (ed), <strong>International</strong> Water <strong>Law</strong>: Selected Writings ofProfessor Charles B. Bourne, the Hague: Kluwer <strong>Law</strong>, 1997, p. 108.11 A. Dixit, Basic Water Science, Kathm<strong>and</strong>u: Nepal Water ConservationFoundation, 2002, pp. 2-20. It has been reported that water evaporatesfrom the sea, rivers, <strong>and</strong> streams, <strong>and</strong> also a large amount of waterenters the atmosphere by transpiration from plants. The same water

Introduction / 3 4 / <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong> in South Asiahave become more extreme <strong>and</strong> dramatic in theirconsequences. 12The water going out from the surface of the earth must comeback in equal amounts - a perpetual cycle with no beginning,middle or end. In other words, the watercourse system is anelement of the hydrological cycle, which consists of theevaporation of water into the atmosphere, chiefly from theoceans, <strong>and</strong> its return to earth through precipitation <strong>and</strong>condensation. 13 The volume of groundwater is large <strong>and</strong> coversa significant quantity of the freshwater system, 14 however, theinternational community (IC) has not agreed upon a setframework of rules on groundwater <strong>and</strong> there are several issuesthat need to be resolved before such rules will be acceptable toall states. 15 As McCaffrey rightly observed, the area ofgroundwater is still in a primary <strong>and</strong> inchoate stage:"as such, the law of international groundwater may onlybe said to be, in the embryonic stages of development, .... but this situation should prevail only until a specialregime can be tailored for international groundwater". 16falls as a result of rain, snow <strong>and</strong> precipitation, which flows over thesurface to percolate into the ground, ground water emerging intostreams <strong>and</strong> moving within aquifers. In this sense, the relation ofground water <strong>and</strong> surface water is inextricably interlinked. Thus, thetotal quantity of water has remained stable over the billions of years.12 N. A. Robinsion (ed), IUCN Environmental Policy & <strong>Law</strong> paper No27: Agenda 21: Earth's Action, New York: Oceana Pub. , 1993, p. 357.13 Supra note 11, p 20.14 Ibid. p. 6, 97% of freshwater remains as groundwater.15 Supra note 10, state practice suggests different practices on groundwater, for example, the USA <strong>and</strong> Canada deliberately rejected theconcept of the unity of a drainage basin for which boundary waterswere separated from tributary waters flowing into boundary waters.Although, equitable utilisation is the applicable rule on groundwater,the Helsinki Conference placed groundwater at the head of the lists ofsubject that it recommended for further study by the ILA. pp. 299, 274& 269.16 Supra note 6, p. 433.Eventually, it appears that until the full regime is developed onthe issues, groundwater is covered by the rules of equitableutilisation adopted in the UN Convention on the Non-Navigable Uses of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> (UNCIW). 17Regardless of the definition of a watercourse (WC) in the 1997UN convention, which includes groundwater, 18 there is still alot that needs to be done in order to obtain an agreeable formulaon the issue. With regard to the lack of freshwater, Falkennarhas distinguished four different causes of water scarcity 19 :aridity, drought, desiccation, <strong>and</strong> water stress.1.2 Uneven Availability <strong>and</strong> ScarcityIn order to accrue optimum benefits from an <strong>International</strong>Watercourse (IWC) it must be developed in a holistic,integrated manner, considering the whole length of awatercourse as a unit. This fact itself highlights the significanceof riparian co-operation in order that maximum benefits can beaccrued from an IWC due to its geographical <strong>and</strong> hydrologicalcircumstance, e.g., a good site to construct a reservoir lies inone country (Nepal), but such augmented water can be used inanother country (India); flood damage can be prevented (India<strong>and</strong> Bangladesh), <strong>and</strong> hydropower plants can be constructed inother countries (in Nepal <strong>and</strong> India). Geography <strong>and</strong> hydrologydetermine this fact. In fact Nepal owns magnificent gorgeswhere high dams can be built <strong>and</strong> the Himalayan waters stored,but such sites are not available in India, Bhutan <strong>and</strong>17 Ibid.18 "Watercourse" means a system of surface waters <strong>and</strong> groundwaterscontributing by virtue of their physical relationship a unitary whole <strong>and</strong>normally flowing into a common terminus. Article 2 (a) of 1997UNCIW, 36 ILM (1997), p. 700.19 R. Clarke, Water: the <strong>International</strong> Crisis, London: Earthscan Pub.,1991, p. 2, as quoted to Malin Falkner from Stockholm's NaturalScience Research Council.

Introduction / 5 6 / <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong> in South AsiaBangladesh. 20 Therefore, cooperation between the riparianstates is essential.The regulation of freshwater resources did not receive muchattention in the international arena prior to the 1950's due to therelative lack of scarcity, fewer international disputes over theuse of water, relatively low levels of use <strong>and</strong> so forth. 21However, during the latter half of the nineteenth century,efforts were made to establish the rule of free navigation ofrivers. Such rules originated with a (Revolutionary) Frenchdecree 22 of November 16, 1792, which opened the RiversScheldt <strong>and</strong> Meuse to the vessels of all riparian states. TheTreaty of Vienna of 1815, 23 along with many navigationaltreaties between nations was based on this decree. 24 The Treatyresolved the long <strong>and</strong> complex disputes on navigational rightsof European states. However, even at this stage, there weredisputes between countries concerning the use of freshwater.The efforts to settle them, which will be analysed at theappropriate juncture of the book, indicated quite clearly therelevance of the issue, <strong>and</strong> laid much essential jurisprudentialgroundwork, which has been developed since 1950. A fewinstances of international disputes over international riversinclude the dispute relating to the River Helmond in 1872 <strong>and</strong>1905 (between Afghanistan <strong>and</strong> Persia), the Nile (betweenEgypt <strong>and</strong> nine other North African states) <strong>and</strong> the Colorado(between Mexico <strong>and</strong> the USA). At the end of the nineteenthcenturythere were numerous conflicts relating to shared waterresources in India, Germany, Austria, Switzerl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> theU.S.A. Municipal court judgements of these <strong>and</strong> other states,have significantly contributed to the codification <strong>and</strong>20 D. Gyawali, “Himalayan Waters: Between Euphoric Dreams <strong>and</strong>Ground Realities” in K. Bahadur & M. Lama (ed), New Perspective onIndia-Nepal Relations, New Delhi: Har-An<strong>and</strong>a Pub., 1995, p. 256.21 L. Caflisch, "Regulation of the Uses of <strong>International</strong> Waterways: TheContribution of the United Nations" in M. I. Glassner (ed), The UnitedNations at Work, Westport: CT, Prager, 1998, p. 4.22 Supra note 10, p. 110.23 Supra note 1, pp. 29-30.24 Supra note 10, p. 110.development of international law in this area. In the nextchapter, a critical analysis of some of the more important ofthese decisions will be provided.As stated above, the use of water increases in comparison to itsavailability, due to alarming population growth <strong>and</strong>unsustainable use of water, e.g., by polluting it, which hascontributed to its scarcity. If the issues cannot be resolved intime, it may reach a level, which threatens the concepts ofpeace <strong>and</strong> security enshrined in the Charter of the UnitedNations. 25 It is because water can neither be substituted norproduced. Whilst some disputes have been resolved, manymore remain, <strong>and</strong> it is indeed a real challenge to theinternational community <strong>and</strong> international law to resolve thesedisputes to the satisfaction of the contesting states. The issuehas been further exacerbated by the increases in daily waterconsumption, which is the inevitable result of enhancedst<strong>and</strong>ards of living. 261.3 Emerging PrinciplesThe fundamental area of this study will be equitable <strong>and</strong>reasonable use of an IWC between riparian states. This bookwill argue that the principle of equity <strong>and</strong> in particular the ruleof equitable utilisation, among others, will be the best way ofresolving disputes involving IWC’s. The case of Nepal, India,Bangladesh <strong>and</strong> Bhutan will be dealt with in view of equitablelegal principles. It should be noted that the topic of pollution isnot directly addressed, although there are occasions where theconcepts “spill over”. For example as discussed below, the25 D.J. Harris, Cases <strong>and</strong> Material on <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong>, London: Sweet<strong>and</strong> Maxwell, 1998, pp. 1048 – 1067: Article 1 of the Charterenvisages settling every dispute by pacific means, enhancinginternational cooperation <strong>and</strong> friendly relations between states <strong>and</strong>Articles 33-38 chart out the procedure of pacific settlement of disputes.26 A. Tanzi <strong>and</strong> M. Arcari, The United Nations Convention on the <strong>Law</strong> of<strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong>: A Framework for Sharing, the Hague:Kluwer <strong>Law</strong>, 2001, p. 4.

Introduction / 7 8 / <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong> in South Asiaapplication of no harm rule for the North American contextinvolves discussion of pollution <strong>and</strong> analyses the failure of theno harm rule in disputes between the US <strong>and</strong> Canada. Theresearch will consider <strong>and</strong> evaluate the existing law on IWC,analyse issues of Nepal’s IWC <strong>and</strong> its link to regional issues,with the objective of assessing current obstacles <strong>and</strong> makingrecommendations for its resolution in the spirit of internationalwater law (IWL). However, the nature of the particularproblems facing Nepal <strong>and</strong> Bhutan are different from those ofother countries. From their point of view, the main problem isnot the lack of water but how to share <strong>and</strong> allocate the benefitsof these abundant water resources, with particular reference toIndia. Whereas, the issues of other riparian states i.e., India <strong>and</strong>Bangladesh, are how to augment the water in the dry season<strong>and</strong> allocate it, <strong>and</strong> also how to avert <strong>and</strong> mitigate the affect offlooding in the monsoon season.Nepal has immense hydropower potential of 83,000 megawatts(MW). Apart from this, these waters can be used for severalpurposes simultaneously 27 e.g., drinking, irrigation,navigational, industrial <strong>and</strong> other uses. So far, little benefit, hasbeen taken 28 , that is to say, vast resources are still not beingtapped. The reasons for this are lack of capital, technology <strong>and</strong>riparian objections. The huge water resources available toNepal have not been beneficially utilised so far. Worse still, inrecent years considerable harm has occurred during the drought<strong>and</strong> monsoon seasons not only in Nepal, but also in India <strong>and</strong>Bangladesh, which have been severely affected by flooding,with huge loss of life <strong>and</strong> property. It is asserted, however, thatif arrangements could be made for the fully beneficial use ofthese resources by all states concerned, it would be a milestoneevent for both the alleviation of poverty <strong>and</strong> the development of27 National Planning Commission (NPC), "The Ninth Plan, 1999-2004”,Kathm<strong>and</strong>u: NPC, (1998), p. 458; also see B. G. Verghese, Waters ofHope, New Delhi: Oxford & IBH Pub., 1990, p. 337.28 Ibid. Less then 19% people have access to electricity, only 45%irrigation facility has been provided so far.infrastructure within all four of the member states of the SouthAsia Association for Regional Co-operation (SAARC). 29 Theadvantages identified so far, are flood control, increasedvolume of water for irrigation (downstream benefits),navigation, recreation <strong>and</strong> miscellaneous other benefits. 30Tremendous harm is caused annually by flooding 31 <strong>and</strong>drought, which could be prevented by international cooperation,<strong>and</strong> the scenario could be reversed by adopting newmeasures for mitigating <strong>and</strong> averting flood water. <strong>International</strong>co-operation on the use <strong>and</strong> sharing the immense benefits ofthese resources has been duly acknowledged but divergence ofinterests, suspicion, distrust <strong>and</strong> non-cooperation have severelyprohibited such opportunities. There is a huge potential beingwasted, that could be utilised by co-operation. 32In order to fulfil the needs <strong>and</strong> aspirations of the people, use ofthese abundant resources is urgently required. It can only bechanged by the states themselves. In the past, few projects weredeveloped, <strong>and</strong> even these projects could not yield equitable<strong>and</strong> reasonable benefits to the parties. What is more,implementation of previous agreements was not carried out29 Ibid. p 393, there are four states Bhutan, Nepal, India <strong>and</strong> Bangladeshwithin the SAARC Quadrangle.30 Ibid. p 465.31 Staff, “Flood Havoc” , The Independent, 5 September 1988: the entirel<strong>and</strong>scape looked as if it had been hit by a brown snowstorm, with justa few village houses <strong>and</strong> same trees rising above it. One whole bank ofthe Ganges was completely submerged, which made the other side ofthe river appear to be the coastline” quoted by an observer. Also seestaff, “Flood in south Asia” The Guardian, 5 September 1988, 25million people were left homeless, more than a thous<strong>and</strong> died as adirect result of the floods, <strong>and</strong> three million tons of rice were lost. Onevillager, who had taken refuge on his roof, described other hardships;“I stay awake through the night to protect my children from deadlysnakes, which often climb on the roof.”32 B. Subba, Himalayan Waters, Kathm<strong>and</strong>u: Panos South Asia, 2001, p.225; also see S. P. Subedi, “Hydro-Diplomacy in South Asia: TheConclusion of the Mahakali <strong>and</strong> Ganges River Treaties” (1999) 93AJIL, pp. 953-962.

Introduction / 9 10 / <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong> in South Asiapursuant to the provisions of the treaties. As a matter of fact,from these experiences Bhutan, Bangladesh <strong>and</strong> Nepal are verycautious in dealing with India with regards to sharing of thebenefits from these resources. The situation will be described inchapter four. The reasons are obvious, India <strong>and</strong> Nepal hadconcluded two treaties in the mid-1960’s, primarily forirrigation, flood control <strong>and</strong> miscellaneous purposes includingthe Kosi project <strong>and</strong> the G<strong>and</strong>ak project. The Nepalese people<strong>and</strong> the political parties alleged that these were carried outentirely for Indian benefit, ignoring Nepal's rights to theseresources. In other words, it was a ‘sell out’ of the naturalresources. 33 Similarly, due to the construction <strong>and</strong> operation ofthe Farakka barrage, at the border between India <strong>and</strong>Bangladesh, on the Ganges River, the barrage has causedsevere adverse impact to Bangladesh <strong>and</strong> planted the seeds ofdistrust <strong>and</strong> suspicion toward the former. Bhutan also appearsnot satisfied with the outcome of past agreement. As will bedescribed later, this project seriously caused adverse affects inBangladesh for a long time period. 34Water resources are the only substantial available naturalresources in this region besides coal <strong>and</strong> gas, <strong>and</strong> there is anurgent need to utilise these water resources expeditiously forthe benefit of the people of the region. There are bottleneckspreventing the achievement ofthis objective, which must be overcome by enhancing bilateralas well as regional co-operation. 3533 B. G.Verghese <strong>and</strong> R. R. Iyer (eds), Harnessing the EasternHimalayan Rivers: Regional Co-operation in South Asia, New Delhi:Konark Pub., 1993, pp. 200-2003; also see B. C. <strong>Upreti</strong>, The Politics ofHimalayan River Waters, New Delhi: Nirala Pub., 1993, pp. 98-118.34 M. Asfuddowalah, “Sharing of Tranboundary Rivers: The GangesTragedy” , M. I. Glassner, (ed), The United Nations at Work, WestportCT: Praeger, 1998, pp. 215-218.35 Supra note 27, pp. 390-393.1.4 Challenge AheadThis book aims to discuss <strong>and</strong> evaluate the present state ofIWL. It will also try to link the issue to Nepal's circumstances,in which water sharing <strong>and</strong> taking benefits therefrom must beaccording to the rules of international law. In principle,international law is equally applicable to all nations. In practice,economically weak nations, such as Nepal or Ethiopia aretreated unequally. For instance, Egypt is able to use mostportions of the waters in the Nile, at the same time, Ethiopiahaving significantly contributing waters in Blue Nile (maintributary of the Nile), is prohibited from using its equitableshare of waters in the same river by the objections <strong>and</strong> threatsof former. In a similar way, Nepal is not able to use its ownshare of water because of Indian objections stating that suchnew use would impair its prior use. India has developed theFarakka barrage. Egypt developed the Aswan dam (with SovietUnion support). China is developing the Three Gorges projectsfrom its own resources, in spite of severe criticism frominternational spheres. 36 Of course, dams are often criticised forpolitical <strong>and</strong> environmental considerations unrelated to riparianissues. In these cases international assistance has not beenforthcoming. <strong>International</strong> cooperation has not been provided toenable the implementation of projects for example in thefollowing cases, Narmada in India, <strong>and</strong> the Southern Antoliaproject in Turkey. There is also a current conflict over theongoing supply of drinking waters from Malaysia to Singapore.In order to develop such water projects, poor countries do nothave resources, they need international or bilateral co-operationin money, technology <strong>and</strong> skilled manpower. Foreign donorsseek clearance from other riparian states <strong>and</strong> these riparianstates object to such a project stating it will affect themadversely. In many cases, donors cancel funding. Therefore, aweak <strong>and</strong> poor country does not have its own resources <strong>and</strong>36 www.internationalwaterlaw.org "Three Gorges Dam". Dams are notconsidered to be a part of sustainable development because of theiradverse affect on ecology <strong>and</strong> indigenous people.

Introduction / 11 12 / <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong> in South Asiadonors refuse to provide assistance on the basis of suchobjections. Suggestions are made in this thesis on how toresolve such a discriminatory system. There are a fewinstruments such as debt relief mechanisms <strong>and</strong> MillenniumDevelopment Goals, which favour poor, geographicallyh<strong>and</strong>icapped <strong>and</strong> vulnerable nations. 37 The adoption of similaradequate arrangements specific to IWCs will be recommended.Arguably, however, the principles of equity <strong>and</strong> the rule ofequitable utilisation could be the best weapons to tackle thesesensitive issues.In order to implement the provisions of international law, thereneeds to be a treaty or agreement between watercourse states, 38<strong>and</strong> the political will to implement such a treaty in the spirit ofgood neighbourliness. Unless these states agree with eachother, the rules of international law cannot be properlyimplemented. The real problem can only be overcome bycooperative <strong>and</strong> good neighbourly relations. <strong>International</strong> lawitself cannot work out any solutions if the states themselves arereluctant to co-operate. In the development of IWL, 'soft law',that is to say, declarations, resolutions <strong>and</strong> so on, although notlegally binding internationally, have some moral or politicalcompulsion, <strong>and</strong> have played a crucial role in the codification<strong>and</strong> development of international law. In this research,examples of both hard <strong>and</strong> soft law will be juxtaposed in regardto the equitable utilisation of watercourse. The main area to becovered in this study will be limited to equitable sharing <strong>and</strong>37 21 ILM 1982, p. 1295, Article 148-participation of developing statesactivities in the area protect the special interest of the l<strong>and</strong>locked <strong>and</strong>geographically disadvantaged nations.38 For example, in order to enjoy the right of right to access to <strong>and</strong> fromthe sea to the l<strong>and</strong>-locked states Article 125 of the UNCLOS III (1)provides the authority, whilst (2) states that 'the terms <strong>and</strong> modalitiesfor exercising freedom of transit shall be agreed between the l<strong>and</strong>lockedstates <strong>and</strong> transit states concerned through bilateral, subregionalor regional agreement', in 21 ILM (1982), p. 1290.the non-navigational use of boundary <strong>and</strong> transboundarywatercourses, although there is some link with Nepal <strong>and</strong>Bhutan's right of access to <strong>and</strong> from the sea through cooperativedevelopment on the Ganges river, which will also beconsidered.The danger in scarce water supply cannot be underestimated.Overuse <strong>and</strong> scarcity of water resources further puts pressureon the supply, quantity <strong>and</strong> quality of freshwater, <strong>and</strong> hasalready added to the number of wars throughout the world inthe twentieth century. 39 If this issue is not settled to thesatisfaction of all nations <strong>and</strong> communities, conflicts areinevitable in the future. 40 As reported in the past, rivers not onlyaggregate humans, they also separate them. 41 That is to say,there are good examples of cooperation in sharing the benefitsfrom IWC, at the same time there are several conflicts, disputes<strong>and</strong> even wars for the same reason.Clarke has argued that conflicts on IWC remain only in thedeveloping world. For example, in Europe there are four sharedrivers, which are effectively regulated by more than 175treaties. 42 Obviously, for developing countries, which lackcapital, technology <strong>and</strong> skilled manpower, co-operation fromother watercourse states is imperative. As will be seen in theforthcoming chapter, none of the donor agencies, whetherbilateral <strong>and</strong> multilateral, are prepared to finance any projectuntil they have positive signals from all other watercourse39 Supra note 6, pp. 272-73. Israelis <strong>and</strong> Arabs fought a war on waterissues in 1967 <strong>and</strong> the danger lies in many areas ahead. A World Bankofficial stated in 1995: 'the wars of the next century will be over water'.40 Supra note 9, p. 1-4.41 Supra note 26, p. 4.42 Supra note 19, p. 91-92.

Introduction / 13 14 / <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong> in South Asiastates in connection with the proposed project. 43 My workingexperience in this regard, particularly in the Nepalese context,is discussed below.1.5 Structure of the BookFollowing this introduction, Chapter Two deals with thedevelopment <strong>and</strong> codification of IWL. It evaluates statepractice, judicial pronouncements, <strong>and</strong> scholarly writings, inbilateral as well as in multilateral dimensions. Evolution ofthese principles, their far-reaching implications <strong>and</strong> criticalanalyses of these principles will be taken into consideration.Chapter Three deals with the concept of equity, itsdevelopment, the emerging concept of equitable utilisation inshared natural resources, <strong>and</strong> the jurisprudence of the<strong>International</strong> Court of Justice (ICJ) <strong>and</strong> its predecessor thePermanent Court of <strong>International</strong> Justice (PCIJ), in the area.The use of equitable utilisation in a shared natural resource hasbeen carried out to take account of the interests of all statesequally <strong>and</strong> without discrimination. It reconciles divergentneeds so as to ensure a fair deal. Apart from this, several courts,such as the ICJ, PCIJ <strong>and</strong> the decisions of numerous arbitrationtribunals <strong>and</strong> national courts in regard to the application ofequity <strong>and</strong> equitable sharing <strong>and</strong> utilisation, will be analysed.Chapter Four deals with IWL <strong>and</strong> its application in the Indo-Nepal context. In this chapter, Nepal’s past experience in waterprojects with her neighbour will be critically dealt with <strong>and</strong>43 D. Goldberg, "World Bank Policy on Projects on <strong>International</strong>Waterways in the context of the <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Commission" in G.H. Blake, W. H. Hildsley, M. A. Pratt, R. J. Ridley &H. Schofield(eds), The Peaceful Management of Transboundary Resources,Dordrecht: Graham & Troatmat/Martinus Nijhoff, 1995, pp 153-165:Bank's Operational Directives (OD) 7.50, an internal policy documentrequired consent from a riparian states on the proposed project in aninternational watercourses in order to provide lending by the Bank.Other donors have adopted the same approach.how other states are doing in similar circumstances will beassessed. Moreover, how other states resolve the issues, howconflicts are averted <strong>and</strong> co-operation achieved, <strong>and</strong> how theyinfluence the Nepalese issues will be evaluated.Chapter Five critically described the legality of India's RiverLinking Project (RLP), its national <strong>and</strong> international dimension<strong>and</strong> its requirement to get rid from the recurring flood, drought<strong>and</strong> famine phenomenon in India <strong>and</strong> Bangladesh. Chapter Sixwill be a conclusion based on the evaluation, assessment <strong>and</strong>the critical analysis of the research. It also will presentconclusions drawn from all available materials, <strong>and</strong> suggest <strong>and</strong>identify the discrepancies, anomalies <strong>and</strong> shortcomings of thepresent system <strong>and</strong> recommend a better way out for theresolution of conflicts in a reasonable, sustainable <strong>and</strong> equitableway. Implications of the research for the areas of human rights,the environment <strong>and</strong> IWL will be provided. The main theme ofthe book will be the application of equity to resolve issuespertaining to the allocation <strong>and</strong> uses of these resources.However, the application of equity is itself a complicated task<strong>and</strong> there is no hard <strong>and</strong> fast rule on how it can apply to anyparticular watercourse. A critical analysis of its application <strong>and</strong>how states have resolved conflicts in similar situations to thatof India <strong>and</strong> Nepal <strong>and</strong> other neighbours will be made. Acritical analysis of four principles of international water lawwill be provided, e.g., territorial sovereignty, territorialintegrity, prior appropriation <strong>and</strong> equitable utilisation. I haveselected equitable utilisation as the best rule for its wideracceptance by the international community.To sum up this chapter, it can be stated that the earth, nature<strong>and</strong> the existence of living beings is impossible withoutfreshwater <strong>and</strong> the fact is that the availability of water isuneven, scarce <strong>and</strong> finite. The total availability of freshwater

has remained the same for millions of years. An United Nationsstudies indicates that by the year 2025, 50 % of the people indeveloping worlds will be lacking in water overall, <strong>and</strong> in westAsia, scarcity will reach 90%. 44 It shows the gravity of theproblem, for which international law <strong>and</strong> modern scientificinnovations have to play a very constructive role in order toresolve the conflicts arising out of it, <strong>and</strong> eliminate the rootcause of the problem in a reasonable <strong>and</strong> equitable way. Theresearch will strive to find such a resolution within the rules ofequitable utilisation.•Introduction / 15 16 / <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong> in South Asia44 P. Brown, “Scarcity of Freshwater”, The Guardian, 23 May 2002, p. 3.

16 / <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong> in South Asia Development <strong>and</strong> Codification of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> / 17Chapter- TwoDevelopment <strong>and</strong> Codification of<strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong>2.1 IntroductionThe availability of <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> for water was not a problemuntil the 1950s except in a few countries with arid <strong>and</strong> semiaridclimates. 1 Thus, there were very few conflicts <strong>and</strong> disputesin this area except in the western part of the United States <strong>and</strong>some parts of the Middle East. 2 In fact, the development ofIWL is a recent phenomenon in international relations. As aconsequence of the increase in various competing uses, givingrise to increasing disputes <strong>and</strong> conflicts, the necessity for lawsto resolve the issues was direly felt. In this context, variousstate practices, concepts <strong>and</strong> rules emerged. However, thedevelopment <strong>and</strong> codification of such rules were undertaken ona piece-meal basis, not based on a holistic framework orapproach.As the human powers to control, divert <strong>and</strong> use the mightyrivers through scientific innovation increased, competing aswell as complementary uses, such as, recreation, irrigation,hydropower, industrial, <strong>and</strong> drinking water have put evengreater strains on finite resources. As a result, hundred of dams<strong>and</strong> reservoirs have been constructed <strong>and</strong> water delivered fardistances to where it was needed; that is to say, technologyhelped undertake mammoth water projects. Such activities, not1 L. Caflisch, "Regulation of the Uses of <strong>International</strong> Waterways: TheContribution of the United Nations" in M. I. Glassaner (ed), TheUnited Nations at Work, Westport, CT: Prager, 1998, p. 4.2 S. C. McCaffrey, The <strong>Law</strong> of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong>, Oxford:Oxford University, 2001, pp. 8-15.surprisingly, led to conflict amongst communities <strong>and</strong> nations.This was exacerbated in the areas where water was alreadyscarce.The <strong>International</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Commission (ILC), an official body ofthe United Nations, drafted <strong>and</strong> adopted the UNCIW. Severalprinciples enunciated in it will be critically assessed, byconsidering the diverging interests <strong>and</strong> views of states <strong>and</strong> theirrepresentatives, including the views of the SpecialRapporteurs. 3There are more than 300 international watercourses (IWC),which are regulated by more than the same number of treaties.The fact is that the practices of states are as different as theissues of each watercourse are unique, <strong>and</strong> require different <strong>and</strong>special arrangements. A few representative treaties will beevaluated, with an appraisal of the principles associated withthese treaties. In the process of the resolution of disputes thatemerged between states, judicial pronouncements by the PCIJ,the ICJ, federal courts <strong>and</strong> arbitral tribunals will also bediscussed. In order to tackle the issues efficiently, a separatediscussion <strong>and</strong> assessment of each segment of the sources ofinternational law, as stipulated in article 38 of the ICJ Statute,i.e., state practice, judgements of courts, international customs<strong>and</strong> writings of reputed publicists, will be carried out. 43 36 ILM UNCIW, 1997, pp 700-720; also see II (1) YBILC (1994), pp.88-135.4 Article 38 of ICJ Statute states: “(1) The court, whose function is todecide in accordance with international law such disputes as aresubmitted to it, shall apply:a. <strong>International</strong> conventions, whether general or particular,establishing rules expressly recognised by the contesting states;b. <strong>International</strong> customs, as evidence of a general practice acceptedas law;c. The general principles of law recognised by civilised nations;d. Subject to the provisions of Article 59, judicial decisions <strong>and</strong> theteachings of the mostly highly qualified publicists of the variousnations, as subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law.

18 / <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong> in South Asia Development <strong>and</strong> Codification of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> / 19In the light of water as essential requirement for people, thedifficulty of access to water <strong>and</strong> the problems associated withits scarcity, a very careful <strong>and</strong> prudent resolution of the issue isof the utmost need in order to maintain smooth relationsbetween riparian states. As has been analysed, the issue by itscomplex nature requires a prudent <strong>and</strong> balanced resolutionreconciling the diverse interests of contestant states. 52.2 Sources of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong>2.2.1 Earliest Stage of Development of IWCThe quantum of water is the same as it was three billion yearsago. 6 At the same time, its uses have gone up to such a pointthat to keep a balance between dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> supply has becomea formidable task. Furthermore, such waters have also becomestrategic resources for several states in order to attain the socioeconomic<strong>and</strong> political aspirations of their people as well as thebest tool for bargaining with other riparian states. The otherreason, however, for the huge increase in the use of the watersis the rising prosperity in human lives along with the rapidpopulation growth. This exacerbates the problem further, <strong>and</strong>the consequence is obvious, more stress on water supply.As a result of misuse <strong>and</strong> overuse of water, the quantityavailable as well as the quality has been found to be decreasingin several parts of the world. Consequently, it has given birth toseveral conflicts. Earlier development in the area by the courts,tribunals, bilateral as well as multilateral conventions, customs,(2) This provision shall not prejudice the power of the court to decidea case ex aequo et bono, if the parties agree thereon.”5 R. Clarke, Water: The <strong>International</strong> Crisis, London: Earthscan Pub.,1991, p. 92.6 A. Dixit, Basic Water Science, Kathm<strong>and</strong>u: Nepal Water ConservationFoundation, 2002, p. 6: “the total supply [of water] neither grows nordiminishes. It is believed to be almost precisely the same now as it was3 billion years ago. Endlessly recycled, water is used, disposed of,purified <strong>and</strong> used again.”agreements, <strong>and</strong> writings of the publicists greatly inspired <strong>and</strong>influenced the resolution of most of the conflicts. Ultimately,on numerous occasions, disputes were resolved amicably <strong>and</strong>peacefully by accommodating divergent interests, but some ofthem remain unresolved. 7 Resolution of the disputes wascarried out in accordance with the concepts of co-operation <strong>and</strong>good neighbourly relations, based on equity, which were laterlargely followed by the other states in their bilateral relations<strong>and</strong> appreciated by the international community. Efforts will beconcentrated on assessing <strong>and</strong> evaluating the far-reachingconsequence of these achievements <strong>and</strong> their implications forthe development of IWL.As stated earlier, scientific innovation has enabled humans toundertake water diversion to far away places as exemplified inthe western part of the United States, Australia, the then SovietUnion, Israel <strong>and</strong> several other parts of the world wheregr<strong>and</strong>iose diversion works have been undertaken. 8 In theMiddle-East (ME), a complex <strong>and</strong> huge project, 'the peacepipeline' has been proposed, which is supposed to deliver waterfrom Turkey to all Middle-Eastern countries including Israel.Apart from this, in Libya, there is an ambitious plan forcollecting <strong>and</strong> diverting water in a pipeline, also called a 'greatman-made river', which stretches from deep aquifers, so called“fossil” water. This is intended to augment the seriouslydepleted groundwater supplies in the coastal region, bybringing water from the hundreds of desert wells at Tazirbu <strong>and</strong>Saria. 9 Nevertheless, with such new developments <strong>and</strong>innovations, the formulation of particular rules that could7 C. B. Bourne, "The Primacy of the Principle of Equitable Utilization inthe 1997 Watercourse Convention" in XXXV CYBIL, (1997) pp. 215-231.8 P. Wouters (ed), <strong>International</strong> Water <strong>Law</strong>: Selected Writtings ofProfessor Charlse. B. Bourne, the Hague: Kluwer <strong>Law</strong>, 1997, pp. 221-241.9 Supra note 2, p. 10.

20 / <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Its</strong> <strong>Application</strong> in South Asia Development <strong>and</strong> Codification of <strong>International</strong> <strong>Watercourses</strong> <strong>Law</strong> / 21address new circumstances <strong>and</strong> issues always remains achallenge to the international community.The uneven availability, scarcity, misuse <strong>and</strong> overuse of thewater, further confronted by the increasing dem<strong>and</strong> of a rapidlyincreasing population will arguably make water the issue of thetwenty-first century. 10 It should not be misunderstood that thescarcity of fresh water only causes conflicts between sovereignindependent states. Similar problems also exist within states, asinter-state water disputes within a federal structure. As a matterof fact, most of the legal development of this area has beenenriched by the inter-state disputes resolution mechanisms inthe United States, India <strong>and</strong> other federal states. Thesignificance of these decisions is of far reaching consequence inthe development <strong>and</strong> codification of IWL. These decisions canbe considered as a foundation of the rule of equitable utilisationin the use of IWCs. 112.2.2 The United StatesThe decisions of the US Supreme Court in water disputesbetween states have provided a rich body of jurisprudence inthe area of equitable utilisation. (In inter-state disputes, the USSupreme Court has used the term ‘equitable apportionment’whilst in international relations the US has used the term‘equitable utilisation’. There is no fundamental differencebetween these terms). To analyse all these decisions is notpossible. However, a quick survey of some representativedecisions is essential. In the United States, each of the 50 statesenacts its own water law. Most such laws hold the view that thewater resources are the wealth of the state through which theyflow. For the protection of their existing use, when such useconflicts with other states, each state tends to rely on its ownlaw. The reasons are apparent. The western part of the USA isan arid or semi-arid area where water is scarce <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> is10 Ibid. p. 64.11 Ibid. p. 228.huge. As a result, there were, <strong>and</strong> still are, water disputes inwhich a lot of norms, concepts <strong>and</strong> ideas have been developedin resolving these issues. Intriguingly, as the disputes went tothe Supreme Court, they were resolved by the application offederal as well as international law, considering the dispute assimilar to the disputes between two sovereign nations. As willbe seen in the forthcoming sub-topic, such decisions haveplayed a significant role in the development of the area wherethe main thrust of the decisions has been ‘equitableapportionment'.In the Kansas v. Colorado cases of 1902 & 1907, Kansas, thedownstream <strong>and</strong> prior user, blamed Colorado for violating thefundamental principle of “use your own without destroyinganother’s legal right” in the Arkansas River. 12 Coloradocontested saying that because the river originates <strong>and</strong> flows inits territory, it has full authority to use its water without caringabout the effects outside its border. The court in its judgementapplied international law principles. The arguments of bothstates solely relying on their own respective water laws wererefused. The court decided that 'equality of right <strong>and</strong> equitybetween two states forbids any interference with the presentwithdrawal of water in Colorado for the purpose of irrigation'. 13The reasons given for the decision were that the court wanted toensure that justice was done to both states in the givensituation. Basically, the judgement upheld the rule of equitableapportionment of the waters, refusing their reliance on 'prioruse' <strong>and</strong> the 'Harmon Doctrine'. The Harmon Doctrine is basedon the 1896 legal opinion of Attorney General Harmon to theSecretary of State in relation to water sharing issues withMexico-US. Harmon stated that the US had full authority to theUS over water that flows in its territory without regards to itseffect on Mexico. The court regarded prior use as only one ofthe factors that had to be considered in determining whether ornot a certain use is equitable <strong>and</strong> not the only determining12 185 U.S. 125 (1902), p. 146.13 206 U.S. 46 (1907), pp. 44-118.