Everything is what it is and not another thing

Everything is what it is and not another thing

Everything is what it is and not another thing

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Every<strong>thing</strong></strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>what</strong> <strong>it</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>not</strong> a<strong>not</strong>her <strong>thing</strong><br />

by David Connearn<br />

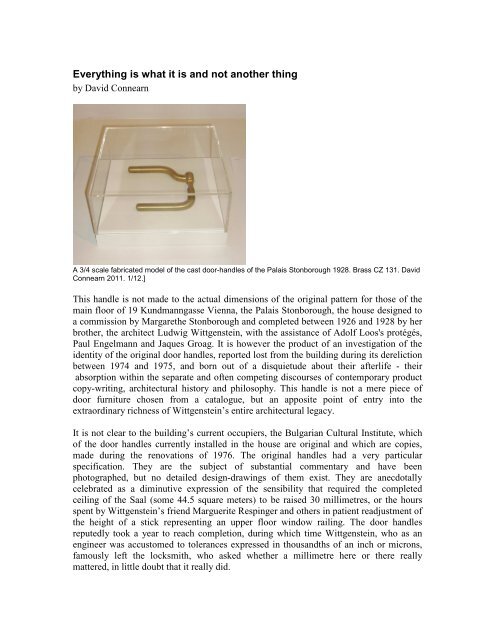

A 3/4 scale fabricated model of the cast door-h<strong>and</strong>les of the Pala<strong>is</strong> Stonborough 1928. Brass CZ 131. David<br />

Connearn 2011. 1/12.]<br />

Th<strong>is</strong> h<strong>and</strong>le <strong>is</strong> <strong>not</strong> made to the actual dimensions of the original pattern for those of the<br />

main floor of 19 Kundmanngasse Vienna, the Pala<strong>is</strong> Stonborough, the house designed to<br />

a comm<strong>is</strong>sion by Margarethe Stonborough <strong>and</strong> completed between 1926 <strong>and</strong> 1928 by her<br />

brother, the arch<strong>it</strong>ect Ludwig W<strong>it</strong>tgenstein, w<strong>it</strong>h the ass<strong>is</strong>tance of Adolf Loos's protégés,<br />

Paul Engelmann <strong>and</strong> Jaques Groag. It <strong>is</strong> however the product of an investigation of the<br />

ident<strong>it</strong>y of the original door h<strong>and</strong>les, reported lost from the building during <strong>it</strong>s dereliction<br />

between 1974 <strong>and</strong> 1975, <strong>and</strong> born out of a d<strong>is</strong>quietude about their afterlife - their<br />

absorption w<strong>it</strong>hin the separate <strong>and</strong> often competing d<strong>is</strong>courses of contemporary product<br />

copy-wr<strong>it</strong>ing, arch<strong>it</strong>ectural h<strong>is</strong>tory <strong>and</strong> philosophy. Th<strong>is</strong> h<strong>and</strong>le <strong>is</strong> <strong>not</strong> a mere piece of<br />

door furn<strong>it</strong>ure chosen from a catalogue, but an appos<strong>it</strong>e point of entry into the<br />

extraordinary richness of W<strong>it</strong>tgenstein’s entire arch<strong>it</strong>ectural legacy.<br />

It <strong>is</strong> <strong>not</strong> clear to the building’s current occupiers, the Bulgarian Cultural Inst<strong>it</strong>ute, which<br />

of the door h<strong>and</strong>les currently installed in the house are original <strong>and</strong> which are copies,<br />

made during the renovations of 1976. The original h<strong>and</strong>les had a very particular<br />

specification. They are the subject of substantial commentary <strong>and</strong> have been<br />

photographed, but no detailed design-drawings of them ex<strong>is</strong>t. They are anecdotally<br />

celebrated as a diminutive expression of the sensibil<strong>it</strong>y that required the completed<br />

ceiling of the Saal (some 44.5 square meters) to be ra<strong>is</strong>ed 30 millimetres, or the hours<br />

spent by W<strong>it</strong>tgenstein’s friend Marguer<strong>it</strong>e Respinger <strong>and</strong> others in patient readjustment of<br />

the height of a stick representing an upper floor window railing. The door h<strong>and</strong>les<br />

reputedly took a year to reach completion, during which time W<strong>it</strong>tgenstein, who as an<br />

engineer was accustomed to tolerances expressed in thous<strong>and</strong>ths of an inch or microns,<br />

famously left the locksm<strong>it</strong>h, who asked whether a millimetre here or there really<br />

mattered, in l<strong>it</strong>tle doubt that <strong>it</strong> really did.

Between then <strong>and</strong> now the h<strong>and</strong>les have however acquired a<strong>not</strong>her life, in which their<br />

image has become more important than the <strong>thing</strong> <strong>it</strong>self. They have become lost in their<br />

own h<strong>is</strong>tory, eclipsed by their representation. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> an inev<strong>it</strong>able tendency of h<strong>is</strong>torical<br />

process, but whilst the original material pers<strong>is</strong>ts <strong>it</strong> behoves us to pay a requ<strong>is</strong><strong>it</strong>e attention<br />

to the <strong>thing</strong>s themselves which, in the words of a<strong>not</strong>her philosopher-art<strong>is</strong>t, “have a lot<br />

going for them”, before we consign their status to unquestioned convention.<br />

The original h<strong>and</strong>les were cast, requiring the fabrication of a prototype from which a<br />

mould was made. The material <strong>and</strong> means of construction of the prototype <strong>is</strong> unknown,<br />

<strong>and</strong> would generally be irrelevant beyond <strong>it</strong>s util<strong>it</strong>y for the requirements of that stage of<br />

the process: <strong>it</strong> could, for instance, have been wax. But every<strong>thing</strong> about these h<strong>and</strong>les<br />

suggests a design narrative in which the cast, as the final form, <strong>is</strong> in fact an anomaly.<br />

They appear to have been designed one step at a time, in a manner which has d<strong>is</strong>tinct<br />

parallels w<strong>it</strong>h the method of work pictured in the activ<strong>it</strong>ies of the builders <strong>and</strong> the<br />

commentary thereon in the opening pages of the Philosophical Investigations. A lim<strong>it</strong>ed<br />

design vocabulary <strong>is</strong> establ<strong>is</strong>hed: bend, house, wedge, bear, fix. Each function <strong>is</strong> then<br />

interrogated as though being defined, or searched for <strong>it</strong>s minimal cond<strong>it</strong>ion or ‘rules’ of<br />

operation <strong>and</strong> application, in relation to the context of ‘usage’ – the practical <strong>and</strong><br />

aesthetic conventions, hab<strong>it</strong>s <strong>and</strong> training, which ground <strong>and</strong> inform the character of the<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing of an object’s ident<strong>it</strong>y, util<strong>it</strong>y <strong>and</strong>, occasionally, <strong>it</strong>s beauty.<br />

In the preface to the Investigations, W<strong>it</strong>tgenstein refers to himself as a draughtsman;<br />

albe<strong>it</strong>, modestly, a bad one. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> rather more than an appropriate metaphor for<br />

compos<strong>it</strong>ional process. It signifies a perspective, for there <strong>is</strong> a very clear formal sense in<br />

both engineering <strong>and</strong> arch<strong>it</strong>ecture that some<strong>thing</strong> which can<strong>not</strong> be drawn (specified)<br />

can<strong>not</strong> be made. Whilst studying engineering in Berlin W<strong>it</strong>tgenstein had indeed taken<br />

add<strong>it</strong>ional drawing classes. Th<strong>is</strong> capabil<strong>it</strong>y was put to use whilst working on jet-tip<br />

propulsion under Petavel <strong>and</strong> Lamb at Manchester, where he showed <strong>what</strong> was then an<br />

extraordinary design skill. At a more domestic scale, having exhausted the patience of<br />

Pinsent, Russell <strong>and</strong> no doubt others on countless fru<strong>it</strong>less trips to select furn<strong>it</strong>ure for h<strong>is</strong><br />

rooms at Cambridge, he designed h<strong>is</strong> own, described by Russell on the occasion of <strong>it</strong>s<br />

later acqu<strong>is</strong><strong>it</strong>ion as ”the best deal I ever made”. Th<strong>is</strong> obsessive capac<strong>it</strong>y to model, to<br />

‘bild’ remained fundamental to him. After leaving Cambridge he designed a small house<br />

for h<strong>is</strong> own use in Norway, which became the template for h<strong>is</strong> repeated intellectual<br />

retreats. It was recogn<strong>is</strong>ed by the Austrian army, which gave him charge of a gunnery<br />

repair workshop during World War 1, prompting h<strong>is</strong> later gift of 1million Crowns for the<br />

development a “decent” cannon. W<strong>it</strong>tgenstein later designed <strong>and</strong> built a steam engine to<br />

demonstrate <strong>it</strong>s working principles to h<strong>is</strong> pupils at one of the schools at which he taught<br />

during the early 1920s in rural Austria. At more serious scale, he personally designed the<br />

lift gear in the Kundmanngasse house, together w<strong>it</strong>h a host of other mechan<strong>is</strong>ms that are<br />

attached to <strong>it</strong>s windows <strong>and</strong> doors, the sliding steel shutters that r<strong>is</strong>e from the floor to<br />

cover them, <strong>and</strong>, of course, the radiators.<br />

Yet <strong>it</strong> <strong>is</strong> these h<strong>and</strong>les in particular which, though seemingly simple, show evidence of<br />

greater a dens<strong>it</strong>y of thought than a merely imposed design. They reveal an intimate

familiar<strong>it</strong>y w<strong>it</strong>h their build-process <strong>and</strong> the particular capabil<strong>it</strong>ies of the material used, a<br />

tactile reg<strong>is</strong>ter of underst<strong>and</strong>ing which has, perhaps underst<strong>and</strong>ably, been overlooked.<br />

<strong>Every<strong>thing</strong></strong> about the design of the h<strong>and</strong>les <strong>is</strong> indicative of a h<strong>and</strong>s-on working<br />

knowledge of the material requirements – <strong>not</strong> of a cast, but of their fabrication. The<br />

radius of the bend in the right-angled h<strong>and</strong>le <strong>is</strong> tight, but <strong>not</strong> arb<strong>it</strong>rary. It <strong>is</strong> the minimum<br />

radius achievable, <strong>not</strong> in a cast object, but by actually bending the material. The radius of<br />

the bends which intersect to form the swaged h<strong>and</strong>le <strong>is</strong> greater than that of <strong>it</strong>s counterpart<br />

by the radius of the h<strong>and</strong>le stock <strong>it</strong>self, <strong>and</strong> w<strong>it</strong>h 60 degrees of arc produces the clearance<br />

common between both h<strong>and</strong>les <strong>and</strong> the door surface. It <strong>is</strong> also the tightest return bend that<br />

steel or malleable brass of that dimension will naturally form when levered rather than<br />

machine-pressed or cast into shape. The swage reduces non-axial leverage on the lock<br />

mechan<strong>is</strong>m <strong>and</strong> h<strong>and</strong>le joint. The v<strong>is</strong>ible part of the cylinder into which both h<strong>and</strong>les f<strong>it</strong><br />

has dimensions no greater than the minimum required to drill <strong>it</strong> across <strong>it</strong>s axes in order to<br />

house the h<strong>and</strong>le shafts in both directions. The combination of all the elements of the<br />

h<strong>and</strong>le-ensemble in a tapered f<strong>it</strong> which bears only on the turning bush of the lock<br />

mechan<strong>is</strong>m, <strong>and</strong> <strong>is</strong> held together by a single axial screw, d<strong>is</strong>plays <strong>not</strong> only an<br />

extraordinary <strong>and</strong> elegant efficiency, but also suggests the family resemblance of the<br />

fabricated elements to parts <strong>and</strong> functions of the machinery - the mill <strong>and</strong> lathe - used to<br />

make them: the tapered quill, the square chuck key, <strong>and</strong> the components of the machinery<br />

controls. All parts of the door h<strong>and</strong>les have a specific reason to be as they are <strong>and</strong> the size<br />

they are, related to the way in which a prototype has been considered <strong>and</strong> made. No<strong>thing</strong><br />

<strong>is</strong> extraneous, but th<strong>is</strong> exemplifies an aesthetic perspective, <strong>not</strong> a program.<br />

The after-life of the “W<strong>it</strong>tgenstein h<strong>and</strong>le” as a source of contemporary style resulting in<br />

objects that have at best a very d<strong>is</strong>tant family resemblance to their source – such as those<br />

by Ize, Technoline GnbH <strong>and</strong> FSB - signals a slippage in underst<strong>and</strong>ing which stretches<br />

beyond the objects themselves, <strong>and</strong> beyond the treatment of the house for which they<br />

were made. I suggest that the material properties of the h<strong>and</strong>les designed by W<strong>it</strong>tgenstein<br />

for the Pala<strong>is</strong> Stonborough are best understood in relation to the design <strong>and</strong> fabrication<br />

requirements of a prototype. The purpose of my investigation has <strong>not</strong> been to replicate,<br />

but to focus attention on the specific<strong>it</strong>y of one small <strong>it</strong>em original material, <strong>and</strong> to afford<br />

<strong>it</strong> a similar consideration to that required of a manuscript fragment. By taking a closer<br />

look at <strong>what</strong> has become by peculiar default the most widely d<strong>is</strong>tributed but least<br />

authentically represented object of W<strong>it</strong>tgenstein’s production, I hope also to have<br />

provided an in<strong>it</strong>ial ‘h<strong>and</strong>le’ on the importance of affording a similar attention to the detail<br />

of the largest remaining unresearched fragment of h<strong>is</strong> career, now approaching the<br />

centenary of <strong>it</strong>s comm<strong>is</strong>sion. A detailed underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the house that W<strong>it</strong>tgenstein<br />

designed for h<strong>is</strong> own use, built in Skjolden, Norway, during 1913/14, elements of which<br />

are known to have a prototypical relationship to elements of the house in the<br />

Kundmanngasse, <strong>is</strong> essential to the proper assessment of W<strong>it</strong>tgenstein's arch<strong>it</strong>ectural<br />

thinking. It <strong>is</strong> likely to be more important than the Kundmanngasse in <strong>it</strong>s relation to h<strong>is</strong><br />

philosophical work. 1479