The extended gateway concept in port hinterland container logistics ...

The extended gateway concept in port hinterland container logistics ...

The extended gateway concept in port hinterland container logistics ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

models and methods <strong>in</strong> the field of <strong>in</strong>termodal <strong>logistics</strong>. Danielis (2006) has put <strong>in</strong>to evidence therole of the economic analysis for <strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>termodal railway trans<strong>port</strong>. Yet, research on themodell<strong>in</strong>g of dry <strong>port</strong>s is only at the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g and many issues still need to be morecomprehensively considered. Indeed, new types of models need to be developed to address the<strong>extended</strong> <strong>gateway</strong> role of dry <strong>port</strong>s <strong>in</strong> both supply cha<strong>in</strong> management and <strong>port</strong> h<strong>in</strong>terland <strong>in</strong>termodal<strong>in</strong>frastructure and service networks. In addition, these models should be formulated based on the socalled‘triple bottom l<strong>in</strong>e’ or ‘susta<strong>in</strong>able’ perspective, by simultaneously <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g economic,environmental and social performance measures of <strong>port</strong> h<strong>in</strong>terland conta<strong>in</strong>er <strong>logistics</strong>.Motivated by these reasons, <strong>in</strong> this paper a capacitated network programm<strong>in</strong>g model featur<strong>in</strong>gl<strong>in</strong>ear parameters and constra<strong>in</strong>ts – called the ‘<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model’ – is theoretically illustrated <strong>in</strong> detailas a tool for the economic analysis and strategic plann<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>port</strong> h<strong>in</strong>terland conta<strong>in</strong>er <strong>logistics</strong>systems accord<strong>in</strong>g to the <strong>extended</strong> <strong>gateway</strong> <strong>concept</strong>. <strong>The</strong> model optimizes the <strong>in</strong>land multimodaldistribution of full and empty conta<strong>in</strong>ers im<strong>port</strong>ed through a regional sea<strong>port</strong> cluster (<strong>in</strong>ward<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model). <strong>The</strong> load<strong>in</strong>g units can also transit through one or more regional dry <strong>port</strong> facilitiesact<strong>in</strong>g as <strong>extended</strong> <strong>gateway</strong>s (the so-called <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s), as well as through extra-regional <strong>in</strong>landlocations featur<strong>in</strong>g a railway term<strong>in</strong>al, before reach<strong>in</strong>g their f<strong>in</strong>al dest<strong>in</strong>ations. As presented here,the model is a novel extension of the homonym transhipment model formulated and empiricallyapplied by Iannone and Thore (2010) to <strong>in</strong>vestigate the <strong>in</strong>land distribution of conta<strong>in</strong>ers im<strong>port</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>Italy through the Campanian sea-land <strong>logistics</strong> system. Based on a perspective of susta<strong>in</strong>able<strong>logistics</strong>, the primal objective function now also <strong>in</strong>ternalizes the external costs <strong>in</strong> terms ofgreenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, noise, accidents and congestion deriv<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>in</strong>landtrans<strong>port</strong> operations.<strong>The</strong> major novelty of this analytical tool consists of the detailed modell<strong>in</strong>g of the conta<strong>in</strong>er releaseoperations at sea<strong>port</strong>s and <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the possibility for shippers to postpone storage andcustoms operations to the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s. More specifically, the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model allows the measurementof the economic, environmental and social benefits aris<strong>in</strong>g from the employment of <strong>extended</strong><strong>gateway</strong>s and <strong>in</strong>termodal trans<strong>port</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>port</strong> h<strong>in</strong>terland conta<strong>in</strong>er distribution. It can simulate longterm alternative scenarios <strong>in</strong> terms of supply of <strong>in</strong>frastructure and services, demand characteristics,and government and <strong>in</strong>dustrial policies. In this respect, the model also enables an exam<strong>in</strong>ation ofpossible public and private policy <strong>in</strong>itiatives to stimulate <strong>port</strong> h<strong>in</strong>terland <strong>in</strong>termodal <strong>logistics</strong>.1.4 Plan for this research<strong>The</strong> rest of the chapter is organized as follows. <strong>The</strong> next section conta<strong>in</strong>s an overview of<strong>in</strong>troductory topics <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>ear programm<strong>in</strong>g which <strong>in</strong>cludes a <strong>concept</strong>ual explanation of the relationsbetween primal and dual programs. Section 3 proposes a stylized representation of how a typical<strong>port</strong> h<strong>in</strong>terland network over which conta<strong>in</strong>er distribution operations are performed is entered <strong>in</strong>tothe <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model. Based on such hypothetical network, a detailed analytical formulation of theprimal and dual programs of the <strong>in</strong>ward <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> problem <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g trans<strong>port</strong> external costs ispresented. F<strong>in</strong>ally, an explanation on how to represent simultaneously the primal and dual problemsby means of data-boxes is provided. Section 4 <strong>in</strong>troduces possible empirical applications of themodel to address practical <strong>port</strong> h<strong>in</strong>terland conta<strong>in</strong>er <strong>logistics</strong> problems <strong>in</strong> Northern Europe andItaly. In addition, some limits of the current formulation of the model are highlighted, envisag<strong>in</strong>gfurther research developments.2. L<strong>in</strong>ear programm<strong>in</strong>g: a methodological overviewL<strong>in</strong>ear programm<strong>in</strong>g is a method of applied mathematical economic analysis for allocat<strong>in</strong>g andutiliz<strong>in</strong>g scarce resources <strong>in</strong> the best possible (optimal) way. A scarce resource is a resource whichis available <strong>in</strong> limited quantities and can also be an output that must be supplied to customers. Inl<strong>in</strong>ear programs such limitations are stated as constra<strong>in</strong>ts.L<strong>in</strong>ear programm<strong>in</strong>g problems can be formulated <strong>in</strong> either m<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>g or maximiz<strong>in</strong>g form. <strong>The</strong>mathematical function to be optimized subjected to constra<strong>in</strong>ts is called the ‘objective function’ and3

can represent, for <strong>in</strong>stance, a cost m<strong>in</strong>imization or profit maximization behaviour. In either case, theorig<strong>in</strong>ally formulated problem is called the ‘primal program’. For every primal program there is arelated unique ‘dual program’ which <strong>in</strong>volves the same data, provides useful <strong>in</strong>formation forsensitivity analyses, enhances the understand<strong>in</strong>g of the orig<strong>in</strong>al model, and allows <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>sights<strong>in</strong>to the <strong>in</strong>terpretation of problem solution.Duality is an extremely im<strong>port</strong>ant <strong>concept</strong> <strong>in</strong> mathematical programm<strong>in</strong>g. Whenever one solves al<strong>in</strong>ear programm<strong>in</strong>g model, he or she implicitly solves two problems: the primal resourceallocation problem, and the dual resource valuation or pric<strong>in</strong>g problem. <strong>The</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> relationshipsexist<strong>in</strong>g between a primal model and its dual can be summarized as follows (see, for <strong>in</strong>stance,Jensen and Bard, 2003, and Thompson and Thore, 1992):- If the primal problem has a m<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>g objective then the dual problem has a maximiz<strong>in</strong>gobjective and vice versa.- When the primal model has n variables and m constra<strong>in</strong>ts, the dual model has m variablesand n constra<strong>in</strong>ts.- For every primal constra<strong>in</strong>t, there is a dual variable. <strong>The</strong> coefficients of dual variables <strong>in</strong>dual objective function are the right hand side of the correspond<strong>in</strong>g primal constra<strong>in</strong>ts.- For every primal variable, there is a dual constra<strong>in</strong>t. <strong>The</strong> right hand sides of dual constra<strong>in</strong>tsare the coefficients of the correspond<strong>in</strong>g primal variables <strong>in</strong> primal objective function.- <strong>The</strong> constra<strong>in</strong>t coefficient matrix of the dual is the transpose of the constra<strong>in</strong>t coefficientmatrix of the primal.- All variables <strong>in</strong> the primal problem are restricted to be nonnegative. As for the dualproblem, the sign of the dual variable correspond<strong>in</strong>g to a right way primal constra<strong>in</strong>t isnonnegative whereas the sign of the dual variable of a wrong way primal constra<strong>in</strong>t isnonpositive; the dual variable of an equality primal constra<strong>in</strong>t is unconstra<strong>in</strong>ed 2 .- <strong>The</strong> dual of a dual is the primal problem.In addition, a primal problem and its dual also share relationships <strong>in</strong> their solution, and it isalways possible to obta<strong>in</strong> primal solution from dual solution and vice versa.<strong>The</strong> l<strong>in</strong>ear formulation of a programm<strong>in</strong>g model provides an evaluation of the scarcity ofresources by means of ‘shadow prices’ or ‘dual variables’. Each constra<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> the primal problemhas an associated shadow price which can be <strong>in</strong>terpreted as the marg<strong>in</strong>al value of the resourcesrepresented by the coefficient <strong>in</strong> the right hand side of the constra<strong>in</strong>t. It is the amount by which theoptimal value of the primal objective function would change per allowable unit variation <strong>in</strong> the righthand side of the correspond<strong>in</strong>g constra<strong>in</strong>t, all other parameters held as constant. To sum up, shadowprices or dual variables <strong>in</strong>dicate how much one would be will<strong>in</strong>g to pay for additional units of givenlimited resources, thus represent<strong>in</strong>g the marg<strong>in</strong>al utility of relax<strong>in</strong>g the correspond<strong>in</strong>g primalconstra<strong>in</strong>ts or equivalently the marg<strong>in</strong>al cost of strengthen<strong>in</strong>g the constra<strong>in</strong>ts.Apart from the constra<strong>in</strong>ts, also all variables of a primal programm<strong>in</strong>g problem have what isknown as a marg<strong>in</strong>al or imputed value. This value is called the ‘reduced cost’ for each variable. <strong>The</strong>variables <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the optimal solution of a problem automatically have a reduced cost of zero.Instead, the reduced cost for any variable not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong>to the f<strong>in</strong>al solution can be <strong>in</strong>terpreted asthe penalty one would pay to force the variable <strong>in</strong>to the solution. In a m<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>g model, theoptimal solution would <strong>in</strong>crease by the amount of the penalty. In a maximiz<strong>in</strong>g problem, thesolution would decrease. In general, if a primal variable is non-basic, the value of its reduced costcoefficient is the value of the slack/surplus variable 3 of the correspond<strong>in</strong>g dual constra<strong>in</strong>t. If a dual2 When the objective function of a l<strong>in</strong>ear program is m<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>g, greater or equal to <strong>in</strong>equalities ( ≥)are “right way<strong>in</strong>equalities” and less than or equal to ( ≤ ) <strong>in</strong>equalities are “wrong way <strong>in</strong>equalities”. For a maximiz<strong>in</strong>g objective, ≤are right way <strong>in</strong>equalities and ≥ are wrong way <strong>in</strong>equalities (Thompson and Thore, 1992; Thore and Iannone, 2005).3 Slack and surplus variables respectively convert ≤ and ≥ <strong>in</strong>equalities to equalities. <strong>The</strong>se quantities are zero forthose constra<strong>in</strong>ts that are satisfied exactly.4

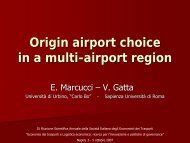

variable is non-basic, the value of its reduced cost coefficient is the value of the slack/surplusvariable of the correspond<strong>in</strong>g primal constra<strong>in</strong>t.<strong>The</strong> primal and dual programs of a l<strong>in</strong>ear programm<strong>in</strong>g model are tied together accord<strong>in</strong>g to theso called ‘complementary slackness conditions’. In particular, complementary slackness is therelationship between slack and/or surplus variables <strong>in</strong> the primal problem and the op<strong>port</strong>unity costs<strong>in</strong> the dual. For <strong>in</strong>stance, if a primal resource has positive slack, it is not b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g on the optimalsolution. Mak<strong>in</strong>g more of this resource available will not improve the optimal value of the objectivefunction. At the same time, because all of the resource is not be<strong>in</strong>g used, it has a dual price of zero.If one uses more of it, he or she does not sacrifice any utility from another use. If, on the other hand,the resource has zero slack, it is called a ‘b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g constra<strong>in</strong>t’. All of the resource is be<strong>in</strong>g used, andmak<strong>in</strong>g more of it available will improve the optimal value of the objective function. However, itwill have a positive op<strong>port</strong>unity cost because the additional units will have to be taken from someother use.Compared with other programm<strong>in</strong>g model types, l<strong>in</strong>ear models are by far the easiest to solve.Optimal values of primal and dual variables, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g reduced costs, are given by moderncomputer programs as part of the optimal solution. Large-scale computer codes are widely availablefor most ma<strong>in</strong>frames and workstations as well as for microcomputers, with only limited restrictions.3. <strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model: a stylized formulation<strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model is an <strong>in</strong>ventory theoretic and capacitated l<strong>in</strong>ear programm<strong>in</strong>g model optimiz<strong>in</strong>gthe road and rail distribution of full and empty conta<strong>in</strong>ers over an <strong>in</strong>land network encompass<strong>in</strong>gsea<strong>port</strong>s, <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s and other locations.This section presents a stylized formulation of the primal and dual programs of the <strong>in</strong>ward<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g trans<strong>port</strong> external costs. Such example covers all the features of reallife <strong>port</strong> h<strong>in</strong>terland conta<strong>in</strong>er network problems that can be <strong>in</strong>vestigated by means of empiricalapplications of the model.3.1 Stylized <strong>port</strong> h<strong>in</strong>terland conta<strong>in</strong>er distribution network and problem descriptionFigure 1 firstly illustrates a hypothetical first tier regional node <strong>in</strong>frastructure system for conta<strong>in</strong>ertraffic. This system comprises a s<strong>in</strong>gle sea<strong>port</strong> represented by node 1, and a s<strong>in</strong>gle <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>featur<strong>in</strong>g the two ‘virtual nodes’ 2 and 3 that are supposed to have an identical geographicallocation but <strong>in</strong>volve <strong>in</strong> part different <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> process<strong>in</strong>g activities. F<strong>in</strong>ally, there are three otherregional and extra-regional <strong>in</strong>land locations, that are the nodes 4, 5, 6, of which only 4 and 5 have arailway term<strong>in</strong>al.<strong>The</strong> sea<strong>port</strong> node 1 is the orig<strong>in</strong> node of this small network, while nodes 2, 4, 5 and 6 are thedest<strong>in</strong>ation nodes. <strong>The</strong>re is one <strong>in</strong>flux <strong>in</strong>to the network: the supply of im<strong>port</strong>ed conta<strong>in</strong>ers at node 1.<strong>The</strong>re are four effluxes: the demands at nodes 2, 4, 5 and 6 for conta<strong>in</strong>ers discharged at the sea<strong>port</strong>.Nodes 2, 4 and 5 are also <strong>in</strong>termediate nodes enabl<strong>in</strong>g the multimodal transhipment of conta<strong>in</strong>erstrans<strong>port</strong>ed from the sea<strong>port</strong> to dest<strong>in</strong>ation. Node 3 is a pure <strong>in</strong>termediate multimodal transhipmentnode because it does not feature a conta<strong>in</strong>er demand; it is supposed to also perform a customsfunction and it is connected to the sea<strong>port</strong> by railway only for conta<strong>in</strong>er transfers under theresponsibility of shipp<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>es (carrier haulage) and without any accompany<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>land customstransit document 4 . In general, node 3 is employed only for the handl<strong>in</strong>g of full conta<strong>in</strong>ers. Bothvirtual nodes 2 and 3 have the same outbound multimodal connections.4 In compliance with the customs regulations currently <strong>in</strong> force <strong>in</strong> Italy, only the railway trans<strong>port</strong> permits the necessaryconditions of fiscal safety related to the <strong>in</strong>land haulage without any accompany<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>land transit document forconta<strong>in</strong>erized cargoes that have not been nationalized yet through customs clearance. Of course, the hypotheticalnetwork shown <strong>in</strong> Figure 1 can be easily expanded to take also account of other <strong>in</strong>land <strong>logistics</strong> solutions such as thosebased on <strong>in</strong>land waterway trans<strong>port</strong>, as well as those arranged under the customs license of maritime term<strong>in</strong>alcompanies.5

LEGENDSea<strong>port</strong>Virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node without customs function4Virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node with customs functionInland location with railway term<strong>in</strong>alInland location served only by truck235Conta<strong>in</strong>er <strong>in</strong>fluxConta<strong>in</strong>er effluxRoad connectionRailway connection16Figure 1 Stylized multimodal <strong>port</strong> h<strong>in</strong>terland <strong>logistics</strong> network with virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodesAs for the railway l<strong>in</strong>ks represented <strong>in</strong> Figure 1, the sea<strong>port</strong> node 1 is connected to the node 4 andto the nodes 2 and 3. Node 3 is reachable from the sea<strong>port</strong> node by railway carrier haulage only andexclusively for the forward<strong>in</strong>g of customs bonded full conta<strong>in</strong>ers. Nodes 2 and 3 are also l<strong>in</strong>ked tothe nodes 4 and 5.Each railway service available <strong>in</strong> real life at the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> is represented by the correspond<strong>in</strong>gspecific rail connections simultaneously available at each virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node. In particular, therail service from the sea<strong>port</strong> to the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> is supposed to simultaneously carry conta<strong>in</strong>ers fromnode 1 to node 2 and from node 1 to node 3. In the same way, the rail service from the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> tothe node 4 simultaneously carries conta<strong>in</strong>ers from node 2 to node 4 and from node 3 to node 4. Andso on.As for the road l<strong>in</strong>ks, node 1 is connected to all the other nodes of the network, exclud<strong>in</strong>g thevirtual node 3. Both virtual nodes 2 and 3 are l<strong>in</strong>ked by road to all the other <strong>in</strong>land locations of thenetwork; furthermore, road trans<strong>port</strong> at a zero generalized cost is admitted from virtual node 3 tovirtual node 2 to meet the conta<strong>in</strong>er demand of im<strong>port</strong><strong>in</strong>g operators located <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>. F<strong>in</strong>ally,the other <strong>in</strong>land nodes hav<strong>in</strong>g a railway term<strong>in</strong>al are connected by truck to some <strong>in</strong>land locationsthat are directly l<strong>in</strong>ked with the regional sea<strong>port</strong>-<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> system. In particular, node 4 can also beemployed as <strong>in</strong>termediate node to serve node 5, while node 5 can also be employed as <strong>in</strong>termediatenode to serve nodes 4 and 6.In practice, at the <strong>in</strong>land nodes served by railway it is assumed the possibility to performmultimodal transhipment operations for various O/D comb<strong>in</strong>ations, that is for traffic relations fromthe supply<strong>in</strong>g sea<strong>port</strong> to the <strong>in</strong>land f<strong>in</strong>al demand<strong>in</strong>g nodes. More specifically, at the extra-regionalnodes served by railway it is assumed the possibility to perform only rail-to-truck and truck-to-trucktranshipment operations, while at the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> it is also assumed the possibility of railway-torailwayand truck-to-railway transhipment operations.<strong>The</strong> stylized network <strong>in</strong> Figure 1 is assumed to be typified by relatively small <strong>in</strong>land locationsfeatur<strong>in</strong>g a railway term<strong>in</strong>al (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> location). Similarly to the other nodes of thenetwork, also the <strong>in</strong>land locations served by railway are assumed as centroid areas <strong>in</strong> which thetraffic of demanded conta<strong>in</strong>ers term<strong>in</strong>ates. Given this configuration of the network, <strong>in</strong>tra-zonal posthaulage activities at these locations are assumed to serve negligible (very short) distances. Hence, atthe moment, such activities are omitted from the modell<strong>in</strong>g entirely.To sum up, once an im<strong>port</strong>ed full conta<strong>in</strong>er has been cleared by customs at node 1, it can bedirectly sent to one of the demand locations 2, 4, 5 and 6. Alternatively, it can be sent to dest<strong>in</strong>ationby transit<strong>in</strong>g through one or more <strong>in</strong>termediate transhipment nodes (exclud<strong>in</strong>g the virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>node 3 with customs function). A similar forward<strong>in</strong>g scheme applies to empty conta<strong>in</strong>ers.6

But there is also another possibility for the distribution of full conta<strong>in</strong>ers. Rather than be<strong>in</strong>gcleared by customs at node 1, a full conta<strong>in</strong>er may be shipped by bonded and sealed railtrans<strong>port</strong>ation from node 1 to node 3, which virtually represents the customs clear<strong>in</strong>g facilitylocated at the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> <strong>in</strong> the h<strong>in</strong>terland. Once cleared here, the conta<strong>in</strong>er may be transferred to itsf<strong>in</strong>al demand location. Of course, empty conta<strong>in</strong>ers do not require customs clearance before be<strong>in</strong>greleased from <strong>in</strong>termodal nodes.<strong>The</strong> splitt<strong>in</strong>g of a s<strong>in</strong>gle <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> facility <strong>in</strong>to two separate virtual nodes enables the formulationof a standard l<strong>in</strong>ear programm<strong>in</strong>g model for the entire network, thus avoid<strong>in</strong>g explicit 0-1programm<strong>in</strong>g features to handle the decisions of where to carry out the customs clearance andstorage operations for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers.3.2 <strong>The</strong> primal programm<strong>in</strong>g modelAs presented here, the primal program of the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model m<strong>in</strong>imizes the total socialgeneralized logistic cost for <strong>port</strong> h<strong>in</strong>terland multimodal distribution of im<strong>port</strong>ed full and emptyconta<strong>in</strong>ers (<strong>in</strong>ward <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model), subjected to flow balance constra<strong>in</strong>ts at all nodes, nonnegativityconstra<strong>in</strong>ts on endogenous variables, and capacity constra<strong>in</strong>ts on all rail connections. <strong>The</strong>model also features a road supply sub-model for the quantification of road trans<strong>port</strong> times atnational scale accord<strong>in</strong>g to the Road Code regulations.<strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model solves for the optimal <strong>in</strong>land rout<strong>in</strong>g of maritime conta<strong>in</strong>ers discharged atone or more sea<strong>port</strong>s. This task <strong>in</strong>cludes f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g the detailed quantities of standardized load<strong>in</strong>g unitsto be shipped from sea<strong>port</strong>s, the trans<strong>port</strong>ation modal choice along each <strong>in</strong>land l<strong>in</strong>k, and the detailedpathway through the system chosen, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the possibility of multimodal transhipmentoperations at one or more regional <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s and at other <strong>in</strong>termediate <strong>in</strong>land nodes featur<strong>in</strong>g arailway term<strong>in</strong>al.<strong>The</strong> model also determ<strong>in</strong>es whether shippers will choose to have their conta<strong>in</strong>erized consignmentscontrolled and cleared by customs directly at the sea<strong>port</strong>s, or whether they will prefer to complywith customs formalities at the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s. By means of parameters represent<strong>in</strong>g dwell times, free ofcharge storage times, handl<strong>in</strong>g charges, demurrage charges, probabilities and costs of customscontrols, the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model simulates <strong>in</strong> detail the conta<strong>in</strong>er release operations and their associatedpric<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms at sea<strong>port</strong> and <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> term<strong>in</strong>als 5 , <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the possibility of relocat<strong>in</strong>gstorage and customs operations from the sea<strong>port</strong>s to the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s (i.e. the <strong>extended</strong> <strong>gateway</strong><strong>concept</strong>). In this respect, the model allows for spell<strong>in</strong>g out various arrangements of customs checkson full conta<strong>in</strong>ers (automated computerized controls, documentary control, X-ray scann<strong>in</strong>g controls,and physical <strong>in</strong>spections).<strong>The</strong> primal equilibrium solution of the model can be broken down <strong>in</strong>to merchant flows and carrierflows, represent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> any case the optimum of a hypothetical shipper operat<strong>in</strong>g the entire network.In the common fashion, the overall solution for this economic agent can be shown to co<strong>in</strong>cide withthe decentralized solutions of <strong>in</strong>dividual programs for each participat<strong>in</strong>g logistic agent who shipsconta<strong>in</strong>ers through the network.All model’s elements are for one plann<strong>in</strong>g period (which <strong>in</strong> the empirical applications hascorresponded to an operational year), and are assumed not to vary dur<strong>in</strong>g the plann<strong>in</strong>g horizon. <strong>The</strong>notations used <strong>in</strong> the model are shown below.5 Term<strong>in</strong>al operators offer conta<strong>in</strong>er storage services to decouple the successive steps <strong>in</strong> the trans<strong>port</strong> cha<strong>in</strong> and theynormally provide a limited amount of free of charge storage time which should allow for the customers to arrangecustoms formalities and other authorities to do their required clearances. Storage rates after free time (demurragecharges) are charged by term<strong>in</strong>al companies to optimize the yard productivity, m<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>g the conta<strong>in</strong>er dwell timedepend<strong>in</strong>g on deliberate supply cha<strong>in</strong> management strategies of us<strong>in</strong>g term<strong>in</strong>als as low cost warehouses. Also customsand adm<strong>in</strong>istrative procedures may add substantially to the dwell time, and therefore to the direct and <strong>in</strong>direct costs forshippers. In some cases, shippers endeavour to have all necessary conta<strong>in</strong>ers checked with<strong>in</strong> free storage time providedby term<strong>in</strong>al companies, with this typically be<strong>in</strong>g not achieved for 100 per cent of conta<strong>in</strong>er volumes and determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gsignificant generalized costs to be borne.7

Indices:I: set of all nodes of the network = { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5,6 }L (I): set of all <strong>in</strong>termodal nodes of the regional <strong>logistics</strong> system = { 1, 2,3 }N (L): set of <strong>in</strong>termodal nodes of the regional <strong>logistics</strong> system exclud<strong>in</strong>g virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodes with1,2customs function = { }O (L): set of <strong>in</strong>termodal nodes of the regional <strong>logistics</strong> system exclud<strong>in</strong>g virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodes1,3without customs function = { }P (O): set of sea<strong>port</strong> nodes of the regional <strong>logistics</strong> system = { 1 }Q (N): set of virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodes without customs function = { 2 }D (O): set of virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodes with customs function = { 3 }Z (I): set of all <strong>in</strong>land locations demand<strong>in</strong>g conta<strong>in</strong>ers = { 2, 4, 5,6 }E (Z): set of <strong>in</strong>land locations (exclud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s) demand<strong>in</strong>g conta<strong>in</strong>ers = { 4, 5,6 }R (Z): set of <strong>in</strong>land locations without rail term<strong>in</strong>al and demand<strong>in</strong>g conta<strong>in</strong>ers = { 6 }H (I): set of <strong>in</strong>land locations perform<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>termediate multimodal transhipment function:2, 3, 4,5{ }T: set of conta<strong>in</strong>er types = { full,empty }M: set of admitted <strong>in</strong>land trans<strong>port</strong>ation modes = { rail,truck }Road_Type: set of road l<strong>in</strong>ear <strong>in</strong>frastructure types = { motorway,other roads }A: set of one-way railway services = { 1_(2+3) , 1_4, ( 2+3 )_4,(2+3)_5}Customs: set of all customs control types = { AC, DC, PI,SC}6Customs2 (Customs): set of customs control types which do not entail additional direct customsAC,DCcosts = { }Customs3 (Customs): set of customs control types entail<strong>in</strong>g additional direct customs costs =PI,SC{ }Parameters:⎡Demand t pi⎤ : vector of demands specified <strong>in</strong> number of conta<strong>in</strong>ers of type t ∈ T (measured <strong>in</strong>⎣ ⎦TEU) by orig<strong>in</strong>-dest<strong>in</strong>ation pair (that is from each sea<strong>port</strong> node p ∈ P towards each node i ∈ I )⎡road _ typeRoad _ dist ij⎤ : vector of kilometer lengths of road l<strong>in</strong>ear <strong>in</strong>frastructure⎣⎦road _ type ∈ Road _ type between nodes i ∈ I and j ∈ I⎡⎣Tot _ road _ distij⎤⎦: vector of kilometer lengths of total road l<strong>in</strong>ear <strong>in</strong>frastructure between nodesroad _ typei ∈ I and j ∈ I , that are given as Tot _ road _ distij= ∑ Road _ distijroad _ type∈Road _ Type⎡road _ typeRoad _ speed ⎤ : vector of admitted average speeds (expressed <strong>in</strong> km/h) of trans<strong>port</strong> by⎣⎦truck over road l<strong>in</strong>ear <strong>in</strong>frastructure road _ type ∈ Road _ type6 AC stands for Automated Computerized Control, DC for Documentary Control, PI for Physical Inspection, and SC forX-ray Scann<strong>in</strong>g.8

⎡Road _ driv _ time ⎤⎣ij : vector of admitted driv<strong>in</strong>g times (expressed <strong>in</strong> number of hours) for⎦trans<strong>port</strong> by truck between nodes i ∈ I and j ∈ I , that are calculated asRoad _ driv _ time⎛ ⎞ ⎛ ⎞⎜ ⎟ ⎜ ⎟⎜ Road _ speed ⎟ ⎜ Road _ speed⎟⎝ ⎠ ⎝ ⎠motorway∈Road _ Type other roads∈Road _ TypeRoad _ distijRoad _ distijij = +motorway∈Road _ Type other roads∈Road _ Type⎡Rests_ time ⎤⎣ij : vector of times for rests (expressed <strong>in</strong> number of hours) prescribed by Road⎦regulations for trans<strong>port</strong> by truck between nodes i ∈ I and j ∈ I⎡Stops_ time ⎤⎣ij : vector of times for stops (expressed <strong>in</strong> number of hours) prescribed by Road⎦regulations for trans<strong>port</strong> by truck between nodes i ∈ I and j ∈ I⎡⎣Rail _ distij⎤⎦: vector of kilometer lengths of rail l<strong>in</strong>ear <strong>in</strong>frastructure between nodes i ∈ I and j ∈ I⎡tRail _ time ij⎤ : vector of times for railway trans<strong>port</strong> of conta<strong>in</strong>ers of type t ∈ T between nodes⎣ ⎦full Ti ∈ I and j ∈ I , where Rail _ time ∈ empty∈Tfull∈Tij is given, while Rail _ timeij= Rail _ timeijfor allempty∈Tempty∈Ti,j ≠ d ∈ D ⊆ I , and Rail _ time i∈I , d∈D= Rail _ time d∈D,i∈I= 0 (virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodes d ∈ D canonly receive and forward full conta<strong>in</strong>ers)⎡tmTot _ trans<strong>port</strong> _ time ij⎤ : vector of total travel times (expressed <strong>in</strong> number of hours) for trans<strong>port</strong>⎣⎦of conta<strong>in</strong>ers of type t ∈ T by mode m ∈ M between nodes i ∈ I and j ∈ I , wheret,rail MijTot _ trans<strong>port</strong> _ time ∈ = Rail _ time , andtijt,truck Mij ∈ = ij + ij +ijTot _ trans<strong>port</strong> _ time Road _ driv _ time Rests _ time Stops _ time⎡tmTrans<strong>port</strong> _ fare ij⎤ : vector of unit prices (measured <strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) for trans<strong>port</strong> of conta<strong>in</strong>ers of⎣⎦type t ∈ T by mode m ∈ M between nodes i ∈ I and j ∈ I⎡tmGas _ cost ⎤ : vector of external unit costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU-km) for emissions of greenhouse gases⎣⎦deriv<strong>in</strong>g from trans<strong>port</strong> of conta<strong>in</strong>ers of type t ∈ T by mode m ∈ M⎡tmAir _ cost ⎤ : vector of external unit costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU-km) of air pollution deriv<strong>in</strong>g from⎣ ⎦trans<strong>port</strong> of conta<strong>in</strong>ers of type t ∈ T by mode m ∈ M⎡tmNoise _ cost ⎤ : vector of external unit costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU-km) of noise deriv<strong>in</strong>g from trans<strong>port</strong>⎣⎦of conta<strong>in</strong>ers of type t ∈ T by mode m ∈ M⎡tmAccident _ cost ⎤ : vector of external unit costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU-km) of accidents deriv<strong>in</strong>g from⎣⎦trans<strong>port</strong> of conta<strong>in</strong>ers of type t ∈ T by mode m ∈ M⎡tmCongestion _ cost ⎤ : vector of external unit costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU-km) of congestion deriv<strong>in</strong>g⎣⎦from trans<strong>port</strong> of conta<strong>in</strong>ers of type t ∈ T by mode m ∈ M⎡tmTot _ extern _ cost ij⎤ : vector of total external unit costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) deriv<strong>in</strong>g from trans<strong>port</strong> of⎣⎦conta<strong>in</strong>ers of type t ∈ T by mode m ∈ M between nodes i ∈ I and j ∈ I , where9

Tot _ extern _ costwhile Tot _ extern _ cost ijt,rail ∈ M=Annual_rate: scalar represent<strong>in</strong>g the annual op<strong>port</strong>unity and economic-technical depreciation costrate of conta<strong>in</strong>erized cargoesIm<strong>port</strong> _ value : scalar represent<strong>in</strong>g the average unit customs declared value (expressed <strong>in</strong>[ ]t,truck∈Mij=⎛t, truck∈Mt,truck∈MGas _ cost + Air _ cost + ⎞⎜⎟t, truck∈Mt,truck∈M= ⎜ Noise _ cost + Accident _ cost + ⎟⋅Tot _ road _ distij;⎜t,truck∈M+ Congestion _ cost⎟⎝⎠⎛t, rail∈Mt,rail∈MGas _ cost + Air _ cost + ⎞⎜⎟t, rail∈Mt,rail∈M= ⎜ Noise _ cost + Accident _ cost + ⎟⋅Rail _ dist⎜t,rail∈M+ Congestion _ cost⎟⎝⎠Euros/TEU) of conta<strong>in</strong>erized im<strong>port</strong> cargoes disembarked at the regional sea<strong>port</strong> systemLeas_cost: scalar represent<strong>in</strong>g the conta<strong>in</strong>er leas<strong>in</strong>g unit charge per day (expressed <strong>in</strong>Euros/TEU/day)⎡ full∈T , mc ij⎤ : vector of total social generalized unit costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) for trans<strong>port</strong> of conta<strong>in</strong>ers⎣ ⎦of type full ∈ T by mode m ∈ M between nodes i ∈ I and j ∈ I , that are calculated asfull∈T , m full∈T , m full∈T , mij _ ij _ _ ijc = Trans<strong>port</strong> fare + Tot extern cost +ij⎧⎡⎛Annual _ rate ⎞⎤⎫⎜⋅ Im<strong>port</strong> _ value ⎟ + Leas_cost ⎪⎢365⎥full∈T , m ⎪+⎝⎠⎨⎢⎥ ⋅Tot _ trans<strong>port</strong> _ timeij⎬⎪⎢24⎥⎪⎪⎢⎥⎩⎣⎦⎪⎭where the first two terms are respectively the direct trans<strong>port</strong> cost and the total trans<strong>port</strong> externalcost (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU), while the third term is the time related cost dur<strong>in</strong>g trans<strong>port</strong> operations (i.e. thesum of <strong>in</strong>-transit <strong>in</strong>ventory hold<strong>in</strong>g cost and conta<strong>in</strong>er leas<strong>in</strong>g cost, <strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU)⎡ empty∈T , mc ij⎤ : vector of total social generalized unit trans<strong>port</strong> costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) for conta<strong>in</strong>ers⎣ ⎦of type empty ∈Tby mode m∈ M between nodes i ∈ I and j ∈ I , that are calculated asempty∈T , m empty∈T , m empty∈T , mij _ ij _ _ ijc = Trans<strong>port</strong> fare + Tot extern cost +⎛ Leas_costempty∈T , m ⎞+ ⎜ ⋅Tot _ trans<strong>port</strong> _ timeij⎟⎝ 24⎠where the first two terms are respectively the direct trans<strong>port</strong> cost and the total trans<strong>port</strong> externalcost (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU), while the third term is the time related cost dur<strong>in</strong>g trans<strong>port</strong> operations (i.e.conta<strong>in</strong>er leas<strong>in</strong>g cost, <strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU)⎡DwTime_ empty ⎤⎣n : vector of unit dwell times (expressed <strong>in</strong> number of days/TEU) for empty⎦conta<strong>in</strong>ers at node n ∈ N10

⎡customs,mDwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> p⎤ : vector of unit <strong>port</strong> dwell times (expressed <strong>in</strong> number of⎣⎦days/TEU) for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers submitted to customs control type customs ∈Customsat sea<strong>port</strong>node p ∈ P , and leav<strong>in</strong>g the same node by trans<strong>port</strong> mode m ∈ M⎡DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> _ CB ⎤⎣p : vector of unit <strong>port</strong> dwell times (expressed <strong>in</strong> number of days/TEU)⎦for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers to be cleared at the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> and leav<strong>in</strong>g the sea<strong>port</strong> node p ∈ P by railwaycarrier haulage under customs bond (without any accompany<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>land customs transit document)⎡DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> _ Aqm ⎤ : vector of unit <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> dwell times (expressed <strong>in</strong> number of⎣⎦days/TEU) for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers already cleared by customs at the sea<strong>port</strong> node and leav<strong>in</strong>g the virtual<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node q ∈Qby trans<strong>port</strong> mode m ∈ M⎡customs,mDwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> ⎤⎣d: vector of unit <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> dwell times (expressed <strong>in</strong> number of⎦days/TEU) for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers submitted to customs control type customs ∈Customsat virtual<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node d ∈ D , and leav<strong>in</strong>g the same node by trans<strong>port</strong> mode m ∈ M⎡customsRatio _ <strong>port</strong> p⎤ : vector of ratios (%) of disembarked full conta<strong>in</strong>ers submitted to customs⎣⎦control type customs ∈Customsbefore to be cleared at sea<strong>port</strong> node p ∈ P⎡customsRatio _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> dp⎤ : vector of ratios (%) of full conta<strong>in</strong>ers arriv<strong>in</strong>g at virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node⎣⎦d ∈ D from sea<strong>port</strong> node p ∈ P by rail under customs bond (without any accompany<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>landcustoms transit document) and to be submitted to customs control type customs ∈ Customs , thatcustomsdpcustomspare given by Ratio _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> = Ratio _ <strong>port</strong> for all d ∈ D⎡Wa _ DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> m p⎤ : vector of weighted average unit <strong>port</strong> dwell times (measured <strong>in</strong>⎣⎦number of days/TEU) of full conta<strong>in</strong>ers cleared by customs at sea<strong>port</strong> node p ∈ P and leav<strong>in</strong>g thesame node by trans<strong>port</strong> mode m ∈ M , that are given by∑,( )m customs m customsp p pcustoms∈CustomsWa _ DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> = DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> ⋅ Ratio _ <strong>port</strong>⎡Wa _ DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> m pd⎤ : vector of weighted average unit <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> dwell times⎣⎦(measured <strong>in</strong> number of days/TEU) of full conta<strong>in</strong>ers arriv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node d ∈ D byrailway carrier haulage under customs bond from sea<strong>port</strong> node p ∈ P , cleared by customs at thesame node d ∈ D , and leav<strong>in</strong>g by trans<strong>port</strong> mode m ∈ M , that are given byWa _ DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>∑customs∈Customsmpd =customs m customs,( DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>dRatio _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>dp)= ⋅⎡Free_ time ⎤⎣l : vector of free of charge conta<strong>in</strong>er storage unit times (measured <strong>in</strong> number of⎦days/TEU) at node l ∈ L⎡tDemurrCharge l⎤ : vector of demurrage unit charges (measured <strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) for conta<strong>in</strong>ers of⎣⎦type t ∈Tat node l ∈ L⎡tHandlCharge l⎤ : vector of conta<strong>in</strong>er handl<strong>in</strong>g unit charges (measured <strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) for⎣⎦conta<strong>in</strong>ers of type t ∈Tat nodel ∈ L11

⎡customs3Additional _ customs _ charge o⎤ : vector of additional customs unit charges (expressed <strong>in</strong>⎣⎦Euros/TEU) for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers submitted to customs control type customs3∈Customs3at nodeo∈O⎡customs2,mPort _ dir _ cost1 p⎤ : vector of direct unit costs (expressed <strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) for handl<strong>in</strong>g⎣⎦and storage of full conta<strong>in</strong>ers submitted to customs control type customs2 ∈Customs2at sea<strong>port</strong>node p ∈ P , and leav<strong>in</strong>g the same node by trans<strong>port</strong> mode m ∈ M , that are calculated asPort _ dir _ cost1customs2,mp=,( _ _ _ )⎧⎡customs2 m full∈T full∈TDwTime full <strong>port</strong> p − Free timep ⋅ DemurrCharge ⎤p + HandlCharge⎪⎣⎦p⎪customs2,m= ⎨if DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> p > Free _ timep⎪full∈Tcustoms2,m⎪HandlChargep if DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> p ≤ Free _ timep⎩where ⎡customs2,mfull∈T( DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> p − Free _ timep ) ⋅ DemurrCharge ⎤⎣p is the unit cost of⎦full Tconta<strong>in</strong>er storage (Euros/TEU), and HandlCharge ∈p is the unit charge for conta<strong>in</strong>er handl<strong>in</strong>g(Euros/TEU).⎡customs3,mPort _ dir _ cost2 p⎤ : vector of direct unit costs (expressed <strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) for handl<strong>in</strong>g,⎣⎦storage, and customs control of full conta<strong>in</strong>ers submitted to customs control typecustoms3 ∈Customs3at sea<strong>port</strong> node p ∈ P , and leav<strong>in</strong>g the same node by trans<strong>port</strong> modem ∈ M , that are calculated asPort _ dir _ cost2customs3,mp=,( _ _ _ )⎧⎡customs3 m full∈T full∈TDwTime full <strong>port</strong> p − Free timep ⋅ DemurrCharge ⎤p + HandlChargep+⎪⎣⎦⎪customs3⎪+Additional _ customs _ chargep⎪customs3,m= ⎨if DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> p > Free _ timep⎪full∈Tcustoms3⎪HandlChargep+ Additional _ customs _ chargep⎪customs3,mif DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> p ≤ Free _ time p⎪⎪⎩⎡customs2,mInter<strong>port</strong> _ dir _ cost1 ⎤⎣d: vector of direct unit costs (expressed <strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) for⎦handl<strong>in</strong>g and storage of full conta<strong>in</strong>ers submitted to customs control type customs2 ∈Customs2atvirtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node d ∈ D , and leav<strong>in</strong>g the same node by trans<strong>port</strong> mode, that are calculated asInter<strong>port</strong> _ dir _ cost1customs2,mdcustoms2,m( _ _d_ d )=⎧⎡full∈TDwTime full <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> − Free time ⋅ DemurrCharge ⎤d+⎪⎣⎦⎪full∈Tcustoms2,m= ⎨+ HandlChargedif DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>d> Free _ time⎪full∈Tcustoms2,m⎪HandlChargedif DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>d≤ Free _ time⎩dd12

where ⎡customs2,m( _ _d− _ d )DwTime full <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> Free time ⋅⎣DemurrChargefull∈Td⎤ is conta<strong>in</strong>er⎦full Tstorage cost, and HandlCharge ∈dis conta<strong>in</strong>er handl<strong>in</strong>g charge⎡customs3,mInter<strong>port</strong> _ dir _ cost2 ⎤⎣d: vector of direct unit costs (expressed <strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) for⎦handl<strong>in</strong>g storage, and customs control of full conta<strong>in</strong>ers submitted to customs control typecustoms3 ∈Customs3at virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node d ∈ D , and leav<strong>in</strong>g the same node by trans<strong>port</strong>mode m ∈ M , that are calculated asInter<strong>port</strong> _ dir _ cost2customs3,mdcustoms3,m( _ _d_ d )=⎧⎡full∈TDwTime full <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> − Free time ⋅ DemurrCharge ⎤d+⎪⎣⎦⎪full∈Tcustoms3⎪+ HandlCharged+ Additional _ customs _ charged⎪customs3,m= ⎨if DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>d> Free _ time⎪full∈Tcustoms3⎪HandlCharged+ Additional _ customs _ charged⎪customs3,mif DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> ≤ Free _ time⎪⎩⎡ f n⎤ : vector of total generalized unit costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) of release operations for empty⎣ ⎦conta<strong>in</strong>ers at <strong>in</strong>termodal node n ∈ N , that are calculated as⎧⎡empty∈T( DwTime _ emptyn − Free _ timen ) ⋅ DemurrCharge ⎤n +⎪⎣⎦⎪empty∈T⎪+ HandlChargen+ ( Leas_rate⋅DwTime _ empty n)⎪fn= ⎨if DwTime_emptyn- Free_time n > 0⎪empty∈T⎪HandlChargen+ ( Leas_rate⋅DwTime _ empty n)⎪⎪if DwTime_emptyn- Free_time n ≤ 0⎩where ⎡empty∈Tempty∈T( DwTime _ emptyn − Free _ timen ) ⋅ DemurrCharge ⎤n + HandlCharge⎣⎦n isterm<strong>in</strong>al operation cost, and ( Leas_rate ⋅ DwTime _ empty n ) is conta<strong>in</strong>er leas<strong>in</strong>g cost⎡g m p⎤ : vector of weighted average total generalized unit <strong>port</strong> costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) of the release⎣ ⎦operations for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers cleared by customs at sea<strong>port</strong> node p ∈ P and leav<strong>in</strong>g the same nodeby trans<strong>port</strong> mode m ∈ M , that are calculated asm ⎡⎛Annual _ rate⎞m ⎤g p = ⎢⎜⋅ Im<strong>port</strong> _ value⎟⋅ Wa _ DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> p +365⎥⎣⎝⎠⎦m( Leas _ cost Wa _ DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> p )customs2,mcustoms2∑ ( Port _ dir _ cost1pRatio _ <strong>port</strong> p )+ ⋅ ++ ⋅ +customs2∈Customs2customs3,mcustoms3∑ ( Port _ dir _ cost2pRatio _ <strong>port</strong>p )customs3∈Customs3+ ⋅ddd13

where⎡⎛Annual _ rate ⎞⎢⎜⋅ Im<strong>port</strong> _ value ⎟⋅Wa _ DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong>⎣⎝365⎠⎤⎥ is weighted average <strong>in</strong>-⎦transit <strong>in</strong>ventory hold<strong>in</strong>g cost, ( Leas _ cost Wa _ DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> m p )conta<strong>in</strong>er leas<strong>in</strong>g cost, and∑customs2∈Customs2customs3∈Customs3( _ _ customs2,m_ customs2Port dir cost1p⋅ Ratio <strong>port</strong> p ) +( _ _ customs3,m_ customs3Port dir cost2pRatio <strong>port</strong> p )mp⋅ is weighted average+ ∑ ⋅is weighted average handl<strong>in</strong>g,storage and customs control cost⎡k p⎤ : vector of total generalized unit <strong>port</strong> costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) of the release operations for full⎣ ⎦conta<strong>in</strong>ers leav<strong>in</strong>g the sea<strong>port</strong> node p ∈ P by railway carrier haulage under customs bond (withoutany accompany<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>land customs transit document) towards the virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node withcustoms function, that are calculated askp( DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> _ CBp Free _ timep ) DemurrChargepfull∈THandlChargep( Leas _ cost DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> _ CBp)⎧⎡full∈T− ⋅ ⎤ +⎪⎣⎦⎪⎪+ + ⋅ +⎪⎪ ⎡⎛Annual _ rate ⎞⎤⎪+ ⎢⎜⋅ Im<strong>port</strong> _ value ⎟⋅DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> _ CB p365⎥⎣⎝⎠⎦⎪= ⎨if DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> _ CBp> Free _ timep⎪full∈T⎪HandlChargep+ ( Leas _ cost ⋅ DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> _ CBp) +⎪⎪ ⎡⎛Annual _ rate ⎞⎤⎪+ ⎢⎜⋅ Im<strong>port</strong> _ value ⎟⋅DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> _ CB p365⎥⎪ ⎣⎝⎠⎦⎪if DwTime _ full _ <strong>port</strong> _ CBp≤ Free _ time⎪p⎩⎡ ms q⎤ : vector of total generalized unit <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) of the release operations for⎣ ⎦full conta<strong>in</strong>ers already cleared by customs <strong>in</strong> the sea<strong>port</strong> node and leav<strong>in</strong>g the virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodeq ∈ Q by trans<strong>port</strong> mode m ∈ M , that are calculated assmqmfull∈T( DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> _ Aq − Free _ timeq ) ⋅ DemurrCharge ⎤q +⎦full∈TmHandlChargeq( Leas _ cost Wa _ DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> _ Aq)⎧⎡⎪⎣⎪⎪+ + ⋅ +⎪⎪ ⎡⎛Annual _ rate ⎞Im<strong>port</strong>m ⎤⎪+ ⎢⎜⋅ _ value ⎟⋅DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> _ A q365⎥⎣⎝⎠⎦⎪mq= ⎨if DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> _ Aq> Free _ time⎪full∈Tm⎪HandlChargeq+ ( Leas _ cost ⋅ DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> _ Aq) +⎪⎪ ⎡⎛Annual _ rate ⎞Im<strong>port</strong>m ⎤⎪+ ⎢⎜⋅ _ value ⎟⋅DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> _ A q365⎥⎪ ⎣⎝⎠⎦⎪mif DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> _ A ≤ Free _ time⎪⎩qq14

⎡u m pd⎤ : vector of weighted average total generalized unit <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> costs (<strong>in</strong> Euros/TEU) of the⎣ ⎦release operations for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers arriv<strong>in</strong>g to virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node d ∈ D from sea<strong>port</strong>node p ∈ P by railway carrier haulage under customs bond (without any accompany<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>landcustoms transit document), and subsequently leav<strong>in</strong>g the same virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node by trans<strong>port</strong>mode m ∈ M after customs clearance, that are calculated asm ⎡⎛Annual _ rate⎞m ⎤u pd = ⎢⎜⋅ Im<strong>port</strong> _ value⎟⋅ Wa _ DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> pd +365⎥⎣⎝⎠⎦m( Leas _ cost Wa _ DwTime _ full _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> pd )customs2,mcustoms2∑ ( Inter<strong>port</strong> _ dir _ cost1dRatio _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>dp)+ ⋅ ++ ⋅ ++customs2∈Customs2∑customs3∈Customs3customs3, mcustoms3( Inter<strong>port</strong> _ dir _ cost2d⋅ Ratio _ <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>dp)⎡WKNOTR1DIR a⎤⎣⎦ : vector of maximal numbers of one-way weekly tra<strong>in</strong>s operated by railwayservice a ∈ A⎡MXNOTEU1TR a⎤⎣⎦ : vector of maximal numbers of conta<strong>in</strong>ers (expressed <strong>in</strong> TEU) per one-waytrip by railway service a ∈ AOPWEEKYEAR: scalar represent<strong>in</strong>g the number of railway operational weeks <strong>in</strong> a year⎡b a⎤⎣ ⎦ : vector of maximal numbers of conta<strong>in</strong>ers (<strong>in</strong> TEU) that can be trans<strong>port</strong>ed by one-wayrailway service a ∈ A , that are calculated asba = OPWEEKYEAR ⋅WKNOTR1DIRa ⋅ MXNOTEU1TRaEndogenous variables:tm⎡⎣x ij⎤⎦: vector of <strong>in</strong>land shipments of conta<strong>in</strong>ers of type t ∈ T (measured <strong>in</strong> TEU) disembarked atthe sea<strong>port</strong> 1∈ P and forwarded between nodes i ∈ I and j ∈ I by trans<strong>port</strong> mode m ∈ M<strong>The</strong> stylized primal <strong>in</strong>ward <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> problem <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g trans<strong>port</strong> external costs reads:m<strong>in</strong> W =tm tm empty∈T , mm full∈T , m( cij xij ) ( fn xni ) ( g p xpz)∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑= ⋅ + ⋅ + ⋅ +t∈T m∈M i∈I j∈I m∈M n∈N i∈I m∈M p∈P z∈Z∑ ∑full∈T , rail∈M m full∈T , m( k p xpd) ∑ ∑ ∑ ( sq xqe)+ ⋅ + ⋅ +p∈P d∈Dm∈M q∈Q e∈E⎡ truck∈Mfull∈T , truck∈Mrail∈Mfull∈T , rail∈M∑ ⎢∑( u1∈P, d xdz) ∑ ( u1∈P,d xde)d∈D z∈Z e∈E+ ⋅ + ⋅⎣⎤⎥⎦(1)subject to:∑ ∑tmt− xpi≥ −Demand1∈P , pfor all t ∈T and p ∈ P(2)i∈I m∈Mtm tm t∑ ∑ ih ∑ ∑ hi 1∈P hm∈M i∈Im∈M i∈Ix − x ≥ Demand , for all t ∈T and h ∈ H(3)15

∑ ∑m∈M i∈I∑t∈T∑t∈T∑t∈T∑t∈Ttmijtmtxir≥ Demand1∈P , rfor all t ∈T and r ∈ R(4)t, rail∈Mt,rail∈M( 1∈P 2∈Q 1∈P 3∈D)xx,+ x,≤ b1_(2+3) ∈A(5)t,rail∈M1∈P 4∈Z,≤ b1_4 ∈A(6)t, rail∈Mt,rail∈M( 2∈Q 4∈Z 3∈D 4∈Z)t, rail∈Mt,rail∈M( 2∈Q 5∈Z 3∈D 5∈Z)x,+ x,≤ b(2+3)_4 ∈A(7)x,+ x,≤ b(2+3)_5 ∈A(8)x ≥ 0 for all t ∈T, m ∈ M , and i, j ∈ I (9)tmxij= 0 if Trans<strong>port</strong> _ fareij= 0for all t ∈T, m ∈ M and i, j ∈ I (10)xfull∈T , truck∈M3∈D 2∈Q≥,0 (11)<strong>The</strong> sets Q and D represent virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodes. A full conta<strong>in</strong>er arriv<strong>in</strong>g at a sea<strong>port</strong>node p ∈ P can either be cleared by the customs right away, <strong>in</strong> which case it can proceed to an<strong>in</strong>land demand<strong>in</strong>g location z ∈ Z , <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodes without customs function( q ∈Q ⊆ Z ). Or it can have its customs clearance delayed, <strong>in</strong> which case it has to proceed byrailway to a virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> node with customs function d ∈ D . In this manner, shippers may avoidcostly delays <strong>in</strong> sea<strong>port</strong> await<strong>in</strong>g access to customs clearance.<strong>The</strong> railway services to/from the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> <strong>in</strong>clude the connections to/from each of the twocorrespond<strong>in</strong>g virtual nodes. For <strong>in</strong>stance, the rail service from the sea<strong>port</strong> node 1 to the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> issymbolically represented by ‘1_(2+3)’, which means that such service carries conta<strong>in</strong>ers from node1 to node 2 and node 3, simultaneously. In the same manner, the rail service from the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> tothe location 5 is symbolically represented by ‘(2+3)_5’, which means that such service carriesconta<strong>in</strong>ers simultaneously from node 2 to node 5 and from node 3 to node 5.<strong>The</strong> demand specified by ‘orig<strong>in</strong> node-orig<strong>in</strong> node’ pair (i.e. Demand for all t ∈T and p ∈ P )<strong>in</strong>dicates the total conta<strong>in</strong>er supply available at the specific <strong>port</strong> node p ∈ P , and is entered <strong>in</strong> themodel with the m<strong>in</strong>us sign <strong>in</strong> order to write the flow conservation constra<strong>in</strong>t (2) with a ≥ sign.<strong>The</strong> critical cost items explicitly taken <strong>in</strong>to account by the model are:- conta<strong>in</strong>er handl<strong>in</strong>g costs;- conta<strong>in</strong>er storage costs, <strong>in</strong> function both of the demurrage charge and of the dwell timeexceed<strong>in</strong>g the free time provided by term<strong>in</strong>al companies at sea<strong>port</strong>s and <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s;- additional direct costs for physical <strong>in</strong>spection and X-ray scanner control by customs atsea<strong>port</strong>s and <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s;- <strong>in</strong>-transit <strong>in</strong>ventory hold<strong>in</strong>g costs, <strong>in</strong> function of the customs declared value of cargoes, thetime duration of distribution operations, and a reference <strong>in</strong>terest rate reflect<strong>in</strong>g both theop<strong>port</strong>unity cost of the capital tied <strong>in</strong> conta<strong>in</strong>erized goods and the economic-technicaldepreciation costs of the same goods;- conta<strong>in</strong>er leas<strong>in</strong>g costs, <strong>in</strong> function both of a conta<strong>in</strong>er leas<strong>in</strong>g charge and of the timeduration of distribution operations;- <strong>in</strong>ternal trans<strong>port</strong> costs;- external trans<strong>port</strong> costs (climate change, air and nose pollution, accidents, congestion).In the objective function (1) such cost items are compressed <strong>in</strong>to aggregated parameters (c, f, g, k,s, and u). Furthermore, the <strong>in</strong>ternal costs of trans<strong>port</strong> either by road or railway toward generic nodes<strong>in</strong>clude the term<strong>in</strong>al operation costs related to the offload<strong>in</strong>g of the conta<strong>in</strong>er from the vehicle at thetpptm16

end of the trip. <strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal costs of road trans<strong>port</strong> from <strong>in</strong>land nodes featur<strong>in</strong>g a railway term<strong>in</strong>al(exclud<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodes) to demand nodes not so equipped comprise the costs of term<strong>in</strong>aloperations both at the departure and at the arrival.Total travel times by road over admitted l<strong>in</strong>ks are equal to the driv<strong>in</strong>g time both on motorwaysand on other road types plus the time for rests and stops prescribed by Road regulations. Roaddriv<strong>in</strong>g times are computed by assum<strong>in</strong>g two different admitted truck’s average speeds overmotorways and other road types. <strong>The</strong> number and time duration of rests and stops need to becalculated as a function of the driv<strong>in</strong>g time 7 . As for total travel times by rail over admitted l<strong>in</strong>ks,these are <strong>in</strong>stead purely exogenous.<strong>The</strong> weighted average total generalized unit <strong>port</strong> and <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> costs of release operations forcleared full conta<strong>in</strong>ers (i.e. the g and u parameters) are computed by tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to consideration bothdirect costs (for term<strong>in</strong>al and customs operations) 8 and time-related <strong>in</strong>direct costs (for <strong>in</strong>ventoryhold<strong>in</strong>g and conta<strong>in</strong>er leas<strong>in</strong>g), accord<strong>in</strong>g to the different probabilities observed <strong>in</strong> the sea<strong>port</strong> p forthe different types of customs control 9 .<strong>The</strong> capacity limits of railway services (i.e. the b parameters) are computed by tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>toaccount: i) the number of railway operational weeks <strong>in</strong> the plann<strong>in</strong>g period, ii) the number ofweekly tra<strong>in</strong>s operated by each service a ∈ A , and iii) the maximal number of conta<strong>in</strong>ers per trip ofthe same service.<strong>The</strong> objective function (1) denotes the total social generalized logistic cost for the distribution ofim<strong>port</strong>ed full and empty conta<strong>in</strong>ers throughout the <strong>port</strong> h<strong>in</strong>terland network. <strong>The</strong> first term representsthe total social cost for rail and road trans<strong>port</strong>ation over the network. <strong>The</strong> second term <strong>in</strong>dicates thetotal release cost for empty conta<strong>in</strong>ers at sea<strong>port</strong> and <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodes. <strong>The</strong> third term denotes thetotal release cost for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers cleared by customs at the sea<strong>port</strong> and leav<strong>in</strong>g by road andrailway. <strong>The</strong> fourth term <strong>in</strong>dicates the total release cost for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers leav<strong>in</strong>g the sea<strong>port</strong> byrailway under customs bond on behalf of shipp<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>es and without any accompany<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>landcustoms transit document. <strong>The</strong> conta<strong>in</strong>ers will be subsequently cleared by customs at the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s.<strong>The</strong> fifth term of the function is the total release cost for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers already cleared <strong>in</strong> thesea<strong>port</strong>, enter<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s, and leav<strong>in</strong>g the same <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s by road and railway. F<strong>in</strong>ally, thesixth term represents the total release cost for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers cleared by customs at the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s,and leav<strong>in</strong>g the same <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s by road and railwayFlow conservation at the orig<strong>in</strong> node requires that the supply at the node must suffice to cover theflows leav<strong>in</strong>g the same node (constra<strong>in</strong>t (2)). For <strong>in</strong>termediate nodes the balanc<strong>in</strong>g conditions statethat the flow enter<strong>in</strong>g each node must suffice to cover the flows leav<strong>in</strong>g it (constra<strong>in</strong>ts representedby (3)). F<strong>in</strong>ally, for each dest<strong>in</strong>ation node, the deliveries forthcom<strong>in</strong>g at the node must suffice tocover demand (constra<strong>in</strong>ts represented by (4)).Capacity constra<strong>in</strong>ts of the railway connections are (5)-(8). <strong>The</strong> limit of each connectiontowards/from the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> jo<strong>in</strong>tly considers the railway services towards/from each of the twocorrespond<strong>in</strong>g virtual nodes (<strong>in</strong> (5), (7), (8)).Non-negativity constra<strong>in</strong>ts on the primal endogenous variables are represented by (9). <strong>The</strong>y statethat the variables cannot assume negative values. In addition, the conditions represented by (10) set7 See, for <strong>in</strong>stance, the computational procedure employed by Aponte et al. (2009) with regard to freight trans<strong>port</strong> onItalian roads.8 <strong>The</strong> term<strong>in</strong>al pric<strong>in</strong>g structure at sea<strong>port</strong>s and <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>s can be much more articulated and diversified than thatmodelled <strong>in</strong> the primal program presented above. Demurrage fees are usually charged by term<strong>in</strong>al operators on aslid<strong>in</strong>g scale. In addition, such charges may generally vary among different term<strong>in</strong>als located <strong>in</strong> the same sea<strong>port</strong> or<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong>, and also accord<strong>in</strong>g to specific agreements among service providers and customers (i.e. term<strong>in</strong>al companies,shipp<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>es and shippers). <strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model may easily simulate whatever type of term<strong>in</strong>al pric<strong>in</strong>g structure.9 For simplification and illustrative purposes, <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model it is assumed that all the conta<strong>in</strong>er transit<strong>in</strong>gthrough the sea<strong>port</strong>s of the <strong>in</strong>vestigated regional logistic system carry legitimate cargoes, and therefore succeed <strong>in</strong>positively pass<strong>in</strong>g the customs controls. Moreover, the model does not take <strong>in</strong>to consideration the payment of customsduties related to the traded goods’ value.17

to zero all variables <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g non-exist<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>ks of the logistic network 10 . F<strong>in</strong>ally, the constra<strong>in</strong>t(11) permits one-way road trans<strong>port</strong> with a nil generalized cost for full conta<strong>in</strong>ers between the twovirtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodes, that is the road trans<strong>port</strong> between 3∈ D and 2 ∈ Q .3.3 <strong>The</strong> dual programm<strong>in</strong>g modelWhen a direct programm<strong>in</strong>g problem is one of cost m<strong>in</strong>imization, the dual program is one ofmaximiz<strong>in</strong>g value. <strong>The</strong> dual program of the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model maximizes the total net appreciation ofconta<strong>in</strong>er flows’ shadow value cumulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the network, while also <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the shadow value ofrail services’ capacity constra<strong>in</strong>ts. <strong>The</strong> problem is subjected to the conditions that the valueappreciation created along each and every l<strong>in</strong>k be exhausted by its costs; <strong>in</strong> addition, there are bothnon-negativity and non-positivity constra<strong>in</strong>ts on endogenous variables.In the primal <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> problem there is a given supply of full and empty conta<strong>in</strong>ers at eachsea<strong>port</strong>, and a given demand at each <strong>in</strong>land location (exclud<strong>in</strong>g the virtual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodes withcustoms function); furthermore, there are <strong>in</strong>termediate transhipment nodes (also <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g all virtual<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> nodes) and capacity limits of railway services. Accord<strong>in</strong>gly, <strong>in</strong> the dual <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> problem,there are shadow prices for each type of traffic flows (i.e. flows of full and empty conta<strong>in</strong>ers)implied at the nodes of the <strong>in</strong>vestigated network. <strong>The</strong>se dual variables measure the value or worthof relax<strong>in</strong>g the correspond<strong>in</strong>g flow conservation constra<strong>in</strong>ts by one unit, and they can be arranged astthe vector ⎡ ⎤ for all t ∈ T and i ∈ I.Also, the dual problem features shadow prices of railwayv i⎣ ⎦capacity constra<strong>in</strong>ts. <strong>The</strong>se parameters can be arranged as the vector [ ] ascc for all a ∈ A,and are<strong>in</strong>terpreted as imputed costs assessed on conta<strong>in</strong>er shipments along the concerned rail services.<strong>The</strong> dual <strong>in</strong>ward <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> problem reads:max Z =( v t t ) ( t t) ( ) p Demand pp + v i Demand pi scc a b a(12)∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑− ⋅ ⋅ + ⋅p∈P t∈T i≠ p∈I p∈P t∈T a∈Asubject to:full∈Tfull∈Tfull∈T , truck∈M1∈P z 1∈P , ztruck∈M1∈P−v + v ≤ c + g for all z ∈ Z(13)full∈T full∈T full∈T , rail∈M rail∈M1∈P 2∈Q 1_(2+3) ∈A≤1∈P , 2∈Q1∈P−v + v + scc c + g(14)full∈T full∈T full∈T , rail∈M1∈P 3∈D 1_(2+3) ∈A≤1∈P , 3∈D−v + v + scc c + k(15)1∈Pfull∈T full∈T full∈T , rail∈M rail∈M1∈P 4∈E1_4∈A ≤1∈P , 4∈E1∈P−v + v + scc c + g(16)full∈Tfull∈Tfull∈T , truck∈M2∈Q e 2∈Q , etruck∈M2∈Q−v + v ≤ c + s for all e ∈ E(17)full∈T full∈T full∈T , rail∈M rail∈M2∈Q 4∈E(2+3)_4∈A≤2∈Q , 4∈E2∈Q−v + v + scc c + s(18)full∈T full∈T full∈T , rail∈M rail∈M2∈Q 5∈E(2+3)_5∈A ≤2∈Q , 5∈E2∈Q−v + v + scc c + s(19)full∈Tfull∈Tfull∈T , truck∈M3∈D z 3∈D,ztruck∈M3∈D−v + v ≤ c + u for all z ∈ Z(20)full∈T full∈T full∈T , rail∈M rail∈M3∈D 4∈E(2+3)_4∈A≤3∈D,4∈E3∈D−v + v + scc c + u(21)10 Similarly to all the large-scale network models, also the <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>port</strong> model uses a sparse data structure, that is a structurebased on data matrices with relatively few non-zero entries. It seems appropriate to remember and highlight the fact that(road and/or railway) connections are not allowed between some nodes of the network <strong>in</strong>vestigated by the model.<strong>The</strong>refore, a value equal to zero has to be assigned to the spatial, temporal and economic attributes of forbidden l<strong>in</strong>ks,and appropriate constra<strong>in</strong>ts have to be formulated accord<strong>in</strong>gly.18

full∈T full∈T full∈T , rail∈M rail∈M3∈D 5∈E(2+3)_5∈A ≤3∈D,5∈E3∈D−v + v + scc c + u(22)full∈Tfull∈Tfull∈T , truck∈Me e'ee'−v + v ≤ c for all e = 4,5 ∈ Efull∈T full∈T full∈T , truck∈M5∈E 6∈E ≤5∈E , 6∈Eand e' = 5,4 ∈ E(23)−v + v c(24)empty∈Tempty∈Tempty∈T , truck∈M1∈P z1∈P , z−v + v ≤ c + f for all z ∈ Z(25)1∈Pempty∈T empty∈T empty∈T , rail∈M1∈P 2∈Q 1_(2+3) ∈A≤1∈P , 2∈Q−v + v + scc c + f(26)empty∈T empty∈T empty∈T , rail∈M1∈P 4∈E1_4∈A ≤1∈P , 4∈E1∈P−v + v + scc c + f(27)empty∈Tempty∈Tempty∈T , truck∈M2∈Q e2∈Q , e−v + v ≤ c + f for all e ∈ E(28)2∈Qempty∈T empty∈T empty∈T , rail∈M2∈Q 4∈E(2+3)_4∈A≤2∈Q , 4∈E1∈P−v + v + scc c + f(29)empty∈T empty∈T empty∈T , rail∈M2∈Q 5∈E(2+3)_5∈A≤2∈Q , 5∈E−v + v + scc c + f(30)empty∈Tempty∈Tempty∈T , truck∈Me e'ee'2∈Q2∈Q−v + v ≤ c for all e = 4,5 ∈ Eempty∈T empty∈T empty∈T , truck∈M5∈E 6∈E ≤5∈E , 6∈Eand e' = 5,4 ∈ E(31)−v + v c(32)tiv ≥ 0 for all i ∈ I and t ∈T(33)scc ≤ 0 for all a ∈ A(34)aIn the dual objective function (12), the total shadow cost the conta<strong>in</strong>er flows enter<strong>in</strong>g the networktt∑ ∑ v ⋅ Demand . <strong>The</strong> total shadow value of the conta<strong>in</strong>er flows leav<strong>in</strong>g out the f<strong>in</strong>alis ( ppp )p∈P t∈Tttdest<strong>in</strong>ations is ∑ ∑ ∑ ( vi⋅ Demandpi )∑ ( scc ⋅b).a∈Aaai≠ p∈I p∈P t∈T. <strong>The</strong> total shadow value of rail capacity <strong>in</strong> the network isFurthermore, there are the dual constra<strong>in</strong>ts represented by (13)-(32). <strong>The</strong>re is one dual constra<strong>in</strong>tfor each and every modal l<strong>in</strong>k <strong>in</strong> the network. It states an im<strong>port</strong>ant pr<strong>in</strong>ciple that is referred to as‘exhaustion of value’. Along any positive road flow <strong>in</strong> the network, the <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> shadow value(that is the difference between the shadow price at dest<strong>in</strong>ation v j and the shadow cost at orig<strong>in</strong> v i )must be exactly exhausted by the total social unit logistic cost of the shipment. Instead, along anypositive rail flow <strong>in</strong> the network, the imputed appreciation -v i + v j along the rail l<strong>in</strong>k plus theshadow price of the capacity limit must be exactly exhausted by the total social unit logistic cost ofthe shipment. That is, all cumulat<strong>in</strong>g values must have a source that can be accounted for. No freevalue can arise.Consider for example the road l<strong>in</strong>k for the transfer of conta<strong>in</strong>ers from node 1 to node 2 <strong>in</strong> Figurefull1. <strong>The</strong> shadow cost of the flow at node 1 is v ; the shadow price of the flow at node 2 is vexhaustion of value condition then states1full full full,truck truck1+2 12+1full,truck truck12+1full2. <strong>The</strong>−v v ≤ c g , i.e. the dual price at node 2cannot exceed the dual price at node 1 plus the unit logistic cost c g . Actually, if there isa positive road trans<strong>port</strong>ation flow along the l<strong>in</strong>k, the shadow price at node 2 must equal the shadowprice at node 1 plus the logistic cost. A hypothetical logistic agent shipp<strong>in</strong>g conta<strong>in</strong>ers from node 1to node 2 will then break exactly even. But there is also the possibility that the shadow value atnode 2 falls short of the shadow cost at node 1 plus the the logistic cost. In that case, the shipperwould suffer an imputed loss and the shipment is not worth his while. No road shipment will take19