ruling elites and decision-making in fascist-era dictatorships

ruling elites and decision-making in fascist-era dictatorships

ruling elites and decision-making in fascist-era dictatorships

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

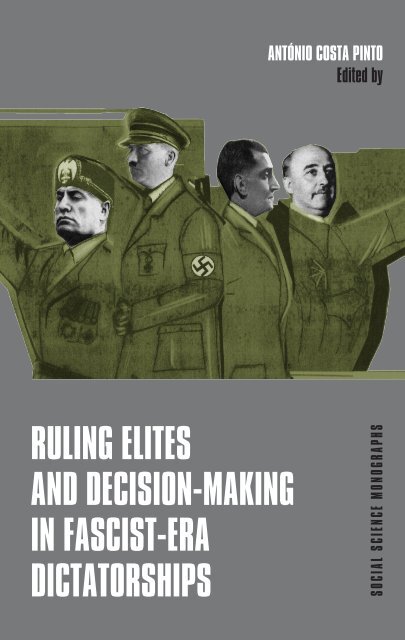

António Costa P<strong>in</strong>toEdited byRULING ELITESAND DECISION-MAKINGIN FASCIST-ERADICTATORSHIPSSOCIAL SCIENCE MONOGRAPHS, BOULDERDISTRIBUTED BY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS, NEW YORK2009

ContentsAcknowledgementsList of Tables <strong>and</strong> FiguresixxiIntroduction: Political <strong>elites</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>fascist</strong>-<strong>era</strong> <strong>dictatorships</strong>António Costa P<strong>in</strong>to1. Mussol<strong>in</strong>i, charisma <strong>and</strong> <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> 1Didier Musiedlak2. Political elite <strong>and</strong> <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Mussol<strong>in</strong>i’s Italy 19Goffredo Ad<strong>in</strong>olfi3. M<strong>in</strong>isters <strong>and</strong> centres of power <strong>in</strong> Nazi Germany 55Ana Mónica Fonseca4. Nazi propag<strong>and</strong>a <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong>: the hybridof ‘modernity’ <strong>and</strong> ‘neo-feudalism’ <strong>in</strong>Nazi wartime propag<strong>and</strong>a 83Aristotle Kallis5. The ‘empire of the professor’: Salazar’sm<strong>in</strong>isterial elite, 1932–44 119Nuno Estêvão Ferreira, Rita Almeida de Carvalho,António Costa P<strong>in</strong>toxv

6. Political <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the PortugueseNew State (1933–9): The dictator, the councilof m<strong>in</strong>isters <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>ner-circle 137Filipa Raimundo, Nuno Estêvão Ferreira,Rita Almeida de Carvalho7. Executive, s<strong>in</strong>gle party <strong>and</strong> m<strong>in</strong>isters <strong>in</strong>Franco’s regime, 1936–45 165Miguel Jerez Mir8. S<strong>in</strong>gle party, cab<strong>in</strong>et <strong>and</strong> political <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>fascist</strong> <strong>era</strong> <strong>dictatorships</strong>: Comparative perspectives 215António Costa P<strong>in</strong>toContributors 253Index 257

AcknowledgementsThis book is the result of a research project undertaken at theUniversity of Lisbon’s Social Sciences Institute <strong>and</strong> funded by thePortuguese Foundation for Science <strong>and</strong> Technology (grant PTDC/HA17/65818/2006), under the title ‘Political <strong>elites</strong>, s<strong>in</strong>gle parties <strong>and</strong><strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>fascist</strong>-<strong>era</strong> <strong>dictatorships</strong>: Portugal, Spa<strong>in</strong>, Italy <strong>and</strong>Germany’.The basis for this research project emerged with the creation ofthe ICS dataset on the <strong>fascist</strong> elite, which <strong>in</strong>cludes complete prosographicaldata on the m<strong>in</strong>isters of Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, Franco’sSpa<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> Salazar’s Portugal, <strong>and</strong> which proved to be a morecomplex task than may be imag<strong>in</strong>ed. Research on Italy, Germany <strong>and</strong>Portugal was undertaken by Ana Mónica Fonseca, Filipa Raimundo,Goffredo Ad<strong>in</strong>olfi, Nuno Estevão Ferreira, Rita Almeida de Carvalho<strong>and</strong> Susana Chalante. Miguel Jerez Mir, <strong>in</strong> collaboration with JavierLuque, Javier Alarcón, José Manuel Trujillo, Isabel Bernal <strong>and</strong> ManuelaOrtega conducted research on Spa<strong>in</strong>. The exam<strong>in</strong>ation of sourceson the council of m<strong>in</strong>isters <strong>and</strong> some of the case studies on <strong>decision</strong><strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong>processes were the responsibility of the authors. One exceptionwas the transcription of Salazar’s h<strong>and</strong>-written diaries, <strong>in</strong> whichhe recorded almost all of his daily activities, which led to the creationof the ICS dataset on Salazar.While the sources consulted <strong>in</strong> the preparation of this book’schapters are spread across many archives <strong>and</strong> libraries, the ma<strong>in</strong> re-

Rul<strong>in</strong>g Elitessearch took place <strong>in</strong> the Central State Archive (Arquivio Centraledello Stato) <strong>in</strong> Rome, the Institute of Contemporary History (Institutsfür Zeitgeschichte) <strong>in</strong> Munich, the National Library (BibliotecaNacional) <strong>and</strong> National Archive (Arquivo Nacional–Torre do Tombo)<strong>in</strong> Lisbon <strong>and</strong> the National Library (Biblioteca Nacional) <strong>in</strong> Madrid.Some prelim<strong>in</strong>ary f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs have been presented at sem<strong>in</strong>ars <strong>and</strong>at a conference at the University of Lisbon’s Social Sciences Institutedur<strong>in</strong>g October 2008, with some of the papers be<strong>in</strong>g published <strong>in</strong> thePortuguese Journal of Social Science 8 (1) (2009).The debt of gratitude the editor owes <strong>in</strong> the preparation of collectedworks is always great, but I would particularly like to mentionthe patience <strong>and</strong> vitality of Juan J. L<strong>in</strong>z, who is both a friend <strong>and</strong> amaster <strong>and</strong> who had collaborated <strong>in</strong> a previous project (Pedro Tavaresde Almeida, António Costa P<strong>in</strong>to, Nancy Bermeo, eds., Who governsSouthern Europe?, London, Frank Cass, 2003) <strong>and</strong> who, while unableto attend the conference, was will<strong>in</strong>g to discuss <strong>and</strong> comment on sev<strong>era</strong>lof the chapters.F<strong>in</strong>ally, I would like to express my thanks to the project’s researchassistant, Claudia Almeida, for her assistance <strong>in</strong> the preparation of thechapters <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dex, to Joaquim António Silva for his patient elaborationof the figures <strong>and</strong> tables <strong>and</strong> for the cover design, to StewartLloyd-Jones for translat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> correct<strong>in</strong>g the text <strong>and</strong>, last but notleast, to Professor Stephen Fischer-Galati, editor of the Social ScienceMonographs.António Costa P<strong>in</strong>toLisbon, July 2009

List of Tables <strong>and</strong> FiguresTables2.1 M<strong>in</strong>isters on the Fascist Gr<strong>and</strong> Council 302.2 M<strong>in</strong>isters on the Fascist Gr<strong>and</strong> Council (by years <strong>in</strong> office) 302.3 Av<strong>era</strong>ge number of Cab<strong>in</strong>ets <strong>and</strong> m<strong>in</strong>isters (Italy) 372.4 Mobility of m<strong>in</strong>isters through portfolios (%) (Italy) 382.5 Cont<strong>in</strong>uity with the lib<strong>era</strong>l regime (Italy) 402.6 Political offices held by m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Italy) 412.7 M<strong>in</strong>isters’ party membership (Italy) 422.8 Party representation <strong>in</strong> Mussol<strong>in</strong>i’s government (%) 432.9 Av<strong>era</strong>ge age of m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Italy) 452.10 Educational level of m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Italy) 472.11 Fields of higher education of m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Italy) 482.12 Occupational distribution of m<strong>in</strong>isters accord<strong>in</strong>g toemployment status (%) (Italy) 482.13 M<strong>in</strong>isters’ occupational background (%) (Italy) 503.1 Educational level of m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Germany) 633.2 University degree of the civilian m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Germany) 633.3 Fields of higher education of m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Germany) 643.4 M<strong>in</strong>isters’ occupational background (Germany) 65

xiiRul<strong>in</strong>g Elites3.5 Political offices held by m<strong>in</strong>isters (Germany) 673.6 Political offices held by m<strong>in</strong>isters underthe Weimar Republic 693.7 M<strong>in</strong>isters’ previous parliamentary experience <strong>in</strong>democratic lib<strong>era</strong>l regime (Germany) 705.1 Duration of m<strong>in</strong>isterial careers by m<strong>in</strong>isterial portfolio(Portugal) 1255.2 M<strong>in</strong>isters’ occupational background (%) (Portugal) 1265.3 Political offices held by m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Portugal) 1306.1 Topics discussed at the council of m<strong>in</strong>isters bycategory (%) (Portugal) 1486.2 Meet<strong>in</strong>gs with m<strong>in</strong>isters before, dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> after hold<strong>in</strong>goffice (Portugal) 1526.3 Meet<strong>in</strong>gs with other political office holders (Portugal) 1577.1 Frequency of meet<strong>in</strong>gs of the council of m<strong>in</strong>isters1938–45 (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 1857.2 Political ‘family’ to which cab<strong>in</strong>et members belonged(1938–45) (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 1947.3 Subjects of agreements at meet<strong>in</strong>gs of the council ofm<strong>in</strong>isters 1939–45 (%) (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 1957.4 M<strong>in</strong>isterial portfolios held by the military (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 1997.5 Age distribution (%) <strong>and</strong> av<strong>era</strong>ge age of m<strong>in</strong>isters (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 2007.6 Educational level of m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 2027.7 University degree of civilian m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 2027.8 Fields of higher education of civilian m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 2027.9 M<strong>in</strong>isters’ occupational background (%) (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 2047.10 Political offices held by m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 2067.11 Political offices held by m<strong>in</strong>isters <strong>in</strong> democratic regime(%) (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 2077.12 M<strong>in</strong>isters’ previous parliamentary experience <strong>in</strong>democratic-lib<strong>era</strong>l regime (%) (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 207

List of Tables <strong>and</strong> Figuresxiii7.13 Duration of m<strong>in</strong>isterial careers (%) (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 2087.14 Mobility of m<strong>in</strong>isters through portfolios (%) (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 2088.1 M<strong>in</strong>isters’ occupational background (%) (Portugal,Spa<strong>in</strong>, Italy <strong>and</strong> Germany) 2358.2 Political offices held by m<strong>in</strong>isters (%) (Portugal, Spa<strong>in</strong>,Italy <strong>and</strong> Germany) 237Figures2.1 Meet<strong>in</strong>gs of the council of m<strong>in</strong>isters <strong>and</strong> of the FascistGr<strong>and</strong> Council 282.2 Portfolios held by Mussol<strong>in</strong>i 292.3 M<strong>in</strong>isterial turnover <strong>in</strong> Mussol<strong>in</strong>i’s governments 322.4 Duration of m<strong>in</strong>isterial careers (years) (Italy) 382.5 Regional orig<strong>in</strong>s of m<strong>in</strong>isters: geographical areas (%) (Italy) 466.1 Number of meet<strong>in</strong>gs of the council of m<strong>in</strong>isters(1933–9) (Portugal) 1477.1 Frequency of meet<strong>in</strong>gs of the council of m<strong>in</strong>isters(1938–45) (Spa<strong>in</strong>) 1857.2 Mobility of m<strong>in</strong>isters <strong>in</strong> Franco’s government 1939–45 192

Introduction:Rul<strong>in</strong>g <strong>elites</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>decision</strong><strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>fascist</strong>-<strong>era</strong><strong>dictatorships</strong>António Costa P<strong>in</strong>toA prudent sovereign will rel<strong>in</strong>quish some of his power voluntarily when helearns … that limitations placed upon his caprice markedly <strong>in</strong>crease his capacityto govern <strong>and</strong> to achieve his steady aims.Jean Bod<strong>in</strong> After the so-called ‘third wave’ of democratisations at the endof the 20th century had significantly <strong>in</strong>creased the number of democracies<strong>in</strong> the world, the survival of many <strong>dictatorships</strong> <strong>and</strong> theemergence of new dictatorial regimes have had an important impact.Tak<strong>in</strong>g as our start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t the <strong>dictatorships</strong> that emerged s<strong>in</strong>ce thebeg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of the 20th century, but ma<strong>in</strong>ly those <strong>in</strong>stitutionalised after1945, the social science lit<strong>era</strong>ture has returned to the question ofthe factors that led to the survival <strong>and</strong> downfall of the <strong>dictatorships</strong><strong>and</strong> dictators <strong>and</strong> which the <strong>fascist</strong> regimes did not escape: the constructionof legitimacy; the regimes’ capacity to distribute resources;divisions with<strong>in</strong> the power coalitions; the political <strong>in</strong>stitutions of the<strong>dictatorships</strong>; their capacity for survival; <strong>and</strong> the cost-benefit analysisof rebellion (G<strong>and</strong>hi 2008).As monocratic regimes, <strong>dictatorships</strong> have been characterised asbe<strong>in</strong>g ‘the selectorate of one’: the dictator, whose power rema<strong>in</strong>s significant(Putnam 1976: 52–3). However, dictators do not rule alone<strong>and</strong> a govern<strong>in</strong>g elite stratum is always formed below them.Cited <strong>in</strong> Holmes (1995: 11).

xviRul<strong>in</strong>g ElitesThis book explores an underdeveloped area <strong>in</strong> the study of fascism<strong>and</strong> right-w<strong>in</strong>g <strong>dictatorships</strong>: the structure of power. The old <strong>and</strong> richtradition of elite studies can tell us much about the structure <strong>and</strong>op<strong>era</strong>tion of political power <strong>in</strong> the <strong>dictatorships</strong> that were associatedwith fascism, whether through the characterisation of the socio- professionalstructure or by the modes of political elite recruitment thatexpress the extent of its rupture <strong>and</strong>/or cont<strong>in</strong>uity with the lib<strong>era</strong>lregime, the type of leadership, <strong>and</strong> the relative power of the political<strong>in</strong>stitutions <strong>in</strong> the new dictatorial system (Lewis 2002; Almeida, P<strong>in</strong>to<strong>and</strong> Bermeo 2003). Analys<strong>in</strong>g four regimes associated with fascism(Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, Franco’s Spa<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> Salazar’s Portugal)from this perspective, the book <strong>in</strong>vestigate the dictator-cab<strong>in</strong>et-s<strong>in</strong>gleparty triad from a comparative perspective.Locat<strong>in</strong>g power <strong>in</strong> <strong>fascist</strong>-<strong>era</strong> <strong>dictatorships</strong>:political <strong>in</strong>stitutions <strong>and</strong> <strong>elites</strong>Italian Fascism <strong>and</strong> German National Socialism provided powerful<strong>in</strong>stitutional <strong>and</strong> political <strong>in</strong>spiration for other regimes, their types ofleadership, <strong>in</strong>stitutions <strong>and</strong> op<strong>era</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g methods already encapsulatedthe dom<strong>in</strong>ant models of the 20th-century dictatorship: personalisedleadership, the s<strong>in</strong>gle or dom<strong>in</strong>ant party <strong>and</strong> the ‘technico-consultative’political <strong>in</strong>stitutions.The <strong>dictatorships</strong> associated with fascism dur<strong>in</strong>g the first half ofthe 20th century were personalised <strong>dictatorships</strong> (Payne 1996). It is<strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g to see that even those regimes that were <strong>in</strong>stitutionalisedfollow<strong>in</strong>g military coups <strong>and</strong> even military <strong>dictatorships</strong> gave birthto personalist regimes <strong>and</strong> more or less successful attempts to creates<strong>in</strong>gle or dom<strong>in</strong>ant parties. The personalisation of leadership <strong>in</strong> the regimeswas transformed <strong>in</strong>to a dom<strong>in</strong>ant trait. More than half of the 172<strong>dictatorships</strong> of the 20th century that had been ‘<strong>in</strong>itiated by militaries,parties, or a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of the two, had been partly or fully personalisedwith<strong>in</strong> three years of the <strong>in</strong>itial seizure of power’ (Geddes 2006:164). However, autocrats need <strong>in</strong>stitutions <strong>and</strong> <strong>elites</strong> to rule <strong>and</strong> theirrole with<strong>in</strong> the regimes is often underestimated, tak<strong>in</strong>g the centralisationof <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> with<strong>in</strong> the <strong>dictatorships</strong> as a given.

IntroductionxviiIn order to avoid their legitimacy be<strong>in</strong>g underm<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>and</strong> theirauthority usurped, dictators need to co-opt <strong>elites</strong> <strong>and</strong> create or adapt<strong>in</strong>stitutions that are a locus for negotiation <strong>and</strong> <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong>:‘without <strong>in</strong>stitutions they cannot make policy concessions’ (Geddes:2006:185). On the other h<strong>and</strong>, as Amos Perlmutter notes, no authoritarianregime can survive politically without the support of modern<strong>elites</strong>, such as bureaucrats, managers, technocrats <strong>and</strong> the military(Perlmutter 1981: 11). The political <strong>in</strong>stitutions of the <strong>dictatorships</strong>,even those that are ‘nom<strong>in</strong>ally democratic’, are not mere w<strong>in</strong>dowdress<strong>in</strong>g: they do affect policy <strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> (G<strong>and</strong>hi 2009). Autocrats alsorequire ‘compliance <strong>and</strong> coop<strong>era</strong>tion’, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> some cases, <strong>in</strong> order‘to organise policy compromises’, they also ‘need nom<strong>in</strong>ally democratic<strong>in</strong>stitutions’ that can serve as a forum <strong>in</strong> which factions <strong>and</strong> canforge agreements (G<strong>and</strong>hi 2009: viii): ‘nom<strong>in</strong>ally democratic <strong>in</strong>stitutionscan help authoritarian rulers ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> coalitions <strong>and</strong> survive <strong>in</strong>power’ (Geddes 2006: 164).When we look at the 20th-century <strong>dictatorships</strong> we note an enormousdegree of <strong>in</strong>stitutional variation. The parties, cab<strong>in</strong>ets, parliaments,corporatist assemblies, juntas <strong>and</strong> the whole set of <strong>in</strong>stitutionsthat Perlmutter def<strong>in</strong>es as ‘the parallel <strong>and</strong> auxiliary structuresof dom<strong>in</strong>ation, mobilisation <strong>and</strong> control’, are symbols of the oftentense diversities that characterise authoritarian regimes (Perlmutter1981: 10).Italian Fascism <strong>and</strong> German National Socialism represented attemptsto create a new set of political <strong>and</strong> para-state <strong>in</strong>stitutions thatwere, <strong>in</strong> one form or another, present <strong>in</strong> other <strong>dictatorships</strong> of theperiod. After tak<strong>in</strong>g power, both the National Socialist <strong>and</strong> Fascistparties became powerful <strong>in</strong>struments of a new order as agents of aparallel adm<strong>in</strong>istration. Transformed <strong>in</strong>to s<strong>in</strong>gle parties they flourishedas breed<strong>in</strong>g-grounds for a new political elite <strong>and</strong> as agentsfor a new mediation between the state <strong>and</strong> civil society, creat<strong>in</strong>gtensions between the s<strong>in</strong>gle party, the government <strong>and</strong> the stateapparatus <strong>in</strong> the process (L<strong>in</strong>z 2007). These tensions were also aconsequence of the emergence of new centres of political <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong>that transferred power from the government <strong>and</strong> the

xviiiRul<strong>in</strong>g Elitesm<strong>in</strong>isterial elite <strong>and</strong> concentrated it <strong>in</strong>to the h<strong>and</strong>s of Mussol<strong>in</strong>i <strong>and</strong>Hitler (P<strong>in</strong>to 2002).The <strong>in</strong>t<strong>era</strong>ction between the s<strong>in</strong>gle party, the government, the stateapparatus <strong>and</strong> civil society appears fundamental if we are to achievean underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of the different ways <strong>in</strong> which the various <strong>dictatorships</strong>of the <strong>fascist</strong> <strong>era</strong> functioned. The party <strong>and</strong> its ancillary organisationswere not merely parallel <strong>in</strong>stitutions; they were also centralagents for the creation <strong>and</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>tenance of the leader’s authority <strong>and</strong>legitimacy.The <strong>fascist</strong> regimes were the first ideological one-party <strong>dictatorships</strong>situated on the right of the European political spectrum, <strong>and</strong>their development—alongside the consolidation of the first communistdictatorship—decisively marked the typologies of dictatorial regimeselaborated dur<strong>in</strong>g the 1950s (Roberts 2006; Brooker 2009).While Friedrich <strong>and</strong> Brzez<strong>in</strong>ski recognised that the s<strong>in</strong>gle party playeda more modest role with<strong>in</strong> the <strong>fascist</strong> regimes than it did with<strong>in</strong> theircommunist peers, part of the classification debate about Europeanfascism cont<strong>in</strong>ued to <strong>in</strong>sist, eventually excessively, that the theories oftotalitarianism ‘deformed’ their role, often without any empirical support(Friedrich <strong>and</strong> Brzez<strong>in</strong>ski 1956).The <strong>in</strong>herent dilemma <strong>in</strong> the transformation of the s<strong>in</strong>gle partyas the dictatorship’s ‘<strong>rul<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitution’ <strong>in</strong>to the leader’s ‘<strong>in</strong>strument ofrule’ is somewhat different <strong>in</strong> right-w<strong>in</strong>g <strong>dictatorships</strong> than for theirsocialist equivalents (P<strong>in</strong>to, Eatwell <strong>and</strong> Larsen 2007). Some authorsspeak of the degen<strong>era</strong>tion of the party as a ruler organisation <strong>in</strong>to an‘agent of the personal ruler’ <strong>in</strong> the case of the communist parties <strong>in</strong>power (Brooker 1995: 9-10). In the <strong>dictatorships</strong> associated with fascism,the s<strong>in</strong>gle party was not the regime’s ‘<strong>rul<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitution’: rather,it was one of many.Many civilian rulers do not have a ‘ready-made organisation uponwhich to rely’ (G<strong>and</strong>hi 2008: 29), <strong>and</strong> to count<strong>era</strong>ct that precariousposition civilian dictators tend to have their own type of organisation.In the <strong>in</strong>ter-war period some <strong>fascist</strong> movements emerged eith<strong>era</strong>s rivals to or <strong>in</strong>stable partners <strong>in</strong> the s<strong>in</strong>gle or dom<strong>in</strong>ant party, <strong>and</strong>often as <strong>in</strong>hibitors to their formation, <strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> the <strong>in</strong>stitutionalisation

Introductionxixof the regimes more difficult for the dictatorial c<strong>and</strong>idates. However,the relationship between the dictators <strong>and</strong> their parties, particularly <strong>in</strong>those that existed prior to the tak<strong>in</strong>g of power, is certa<strong>in</strong>ly very complex.For example, Italian Fascism seems to provide a good illustrationof the thesis that ‘where a party organisation has developed priorto the seizure (of power) <strong>in</strong> which able lieutenants have made theircareers, possibly developed regional bases of support, <strong>and</strong> comm<strong>and</strong>the loyalty of men who fought under them, party members also havegreater ability to constra<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong>, if necessary, replace leaders” (Geddes2006: 162), which is very different from the case with German NationalSocialism.The centre of <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> is also very different across the<strong>dictatorships</strong>. As many case studies have shown, ‘to mitigate the threatposed by <strong>elites</strong>, dictators frequently establish <strong>in</strong>ner sanctums wherereal <strong>decision</strong>s are made <strong>and</strong> potential rivals are kept under close scrut<strong>in</strong>y’(G<strong>and</strong>hi 2008: 20). Dictators usually establish smaller formal <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>formal <strong>in</strong>stitutions ‘as a first <strong>in</strong>stitutional trench aga<strong>in</strong>st threats fromthe <strong>rul<strong>in</strong>g</strong> elite’ (Geddes 2006: 164).This book, then, analyses this relationship between the s<strong>in</strong>gle parties<strong>and</strong> the political <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutions with<strong>in</strong> those <strong>dictatorships</strong>associated with fascism, focus<strong>in</strong>g on the relationship betweenthe dictators, the s<strong>in</strong>gle parties, the cab<strong>in</strong>et <strong>and</strong> the govern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>elites</strong>.The authors also seek to identify the ma<strong>in</strong> centre of <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong>power, the ma<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional veto players <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>t<strong>era</strong>ction betweenthe formal <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>formal power structures <strong>in</strong> each of the regimes be<strong>in</strong>gstudied.

xxRul<strong>in</strong>g ElitesREFERENCESAlmeida, P. T., P<strong>in</strong>to, A. C., <strong>and</strong> Bermeo, N. (eds) (2004), Who Governs SouthernEurope? Regime change <strong>and</strong> m<strong>in</strong>isterial recruitment, 1850-2000, London: FrankCass.Brooker, P. (2009), Non-democratic regimes, London: Palgrave.———, (1995), Twentieth-century <strong>dictatorships</strong>: The ideological one-party states, NewYork, NY: New York University Press.Friedrich, C. J. <strong>and</strong> Brzez<strong>in</strong>ski, Z. K. (1956), Totalitarian dictatorship <strong>and</strong> autocracy,Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Geddes, B. (2006), ‘Stages of development <strong>in</strong> authoritarian regimes’, <strong>in</strong> Tismaneanu,V., Howard, M. M. <strong>and</strong> Sil, R. (eds), World order after Len<strong>in</strong>ism, Seattle <strong>and</strong>London: University of Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Press, pp. 149–70.Gh<strong>and</strong>i, J. (2008), Political <strong>in</strong>stitutions under dictatorship, Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press.Holmes, S. (1995), Passion <strong>and</strong> constra<strong>in</strong>t: On the theory of lib<strong>era</strong>l democracy, Chicago:University of Chicago Press.L<strong>in</strong>z, J. J. (2007), ‘Fascism <strong>and</strong> non-democratic regimes’, <strong>in</strong> Maier, H. (ed.), Totalitarianism<strong>and</strong> political religions, vol.3: Concepts for the comparison of <strong>dictatorships</strong>:theory <strong>and</strong> history of <strong>in</strong>terpretation, London: Routledge, pp. 225–91.Lewis, P. H. (2002), Lat<strong>in</strong> <strong>fascist</strong> <strong>elites</strong>. The Mussol<strong>in</strong>i, Franco <strong>and</strong> Salazar regimes,Westport: Praeger.Payne, S. G. (1996), A history of fascism, Madison, WI: University of Wiscons<strong>in</strong>Press.Perlmutter, A. (1981), Modern Authoritarianism. A comparative <strong>in</strong>stitutional analysis,New Haven <strong>and</strong> London: Yale University Press.P<strong>in</strong>to, A. C. (2002), ‘Elites, s<strong>in</strong>gles parties <strong>and</strong> political <strong>decision</strong>-<strong>mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>fascist</strong><strong>era</strong><strong>dictatorships</strong>’, Contemporary European History 11 (3): 429-54.P<strong>in</strong>to, A. C., Eatwell, R. <strong>and</strong> Larsen, S. U. (eds) (2007), Charisma <strong>and</strong> fascism <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ter-war Europe, London: Routledge.Putnam, R. D. (1976), The comparative study of political <strong>elites</strong>, Englewood Cliffs, NJ:Prentice-Hall.