230 Chestnut Street Pacific Grove, California 93950 heraldpetrel ...

230 Chestnut Street Pacific Grove, California 93950 heraldpetrel ...

230 Chestnut Street Pacific Grove, California 93950 heraldpetrel ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

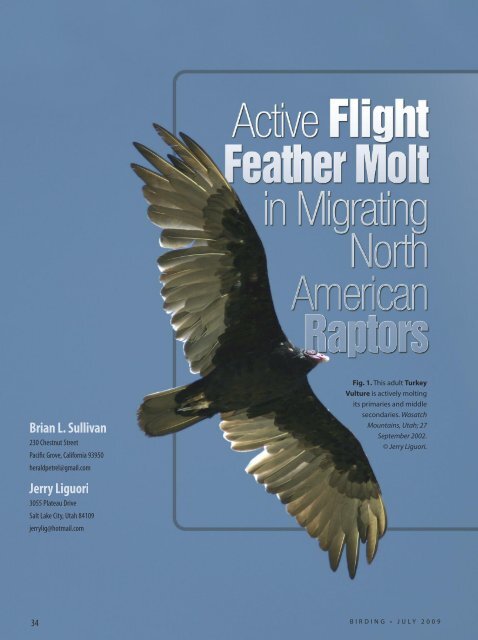

<strong>230</strong> <strong>Chestnut</strong> <strong>Street</strong><strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>Grove</strong>, <strong>California</strong> <strong>93950</strong><strong>heraldpetrel</strong>@gmail.comFig. 1. This adult TurkeyVulture is actively moltingits primaries and middlesecondaries. WasatchMountains, Utah; 27September 2002.© Jerry Liguori.3055 Plateau DriveSalt Lake City, Utah 84109jerrylig@hotmail.com34B i r d i n g • J u l y 2 0 0 9

ood feather condition is an essential component of the lives of birds.All birds undergo the process of molt, replacing worn feathers withnew ones, and this process is typically completed annually. Birds normallymolt only when sufficient resources are available and when it fits intotheir life cycles. The process of active flight feather molt is often insertedinto the lives of birds when other energetic demands are at a low point, butfor large species like raptors, molt takes place over an extended period andoften overlaps with breeding. This overlap can be on the order of fourmonths—shorter in smaller species, longer in larger species. This molt typicallyoccurs between April and September, in order to provide ample timeto replace flight feathers prior to migration. In contrast, most passerines requireless time to molt, undergoing a complete prebasic molt after thebreeding season and just before fall migration.Molt and migration can be physiologically expensive processes for birds, and conventionalwisdom suggests that the two processes typically do not occur simultaneously (Payne 1972,Clark 2001, Elphick et al. 2001). However, whether the separation of these two processes isdriven by physiological demands or aerodynamic limitations, or by some combination of thetwo, remains unclear and may depend on the species. Flight feather molt results in gaps in thewing surface, which could compromise successful migration. Exceptions are known for certaintaxa, including Herring Gull (Steve N. G. Howell, personal communication), Black Tern(Zenatello et al. 2002), and several swallow species (Howell, personal communication),which undergo slow replacement of flight feathers during migration. Both the Red-eyed Vireoand Rose-breasted Grosbeak are exceptional among temperate breeding long-distance migrantpasserines in that they molt flight feathers during fall migration (Tordoff and Mengel 1956,Cannell et al. 1983). Despite previous mention of this phenomenon in the family Accipitridae(Liguori 2000, 2002, 2005, 2009), it is not widely discussed in the molt literature. Pyle (2008)gives raptor molt its most thorough treatment to date, mentioning active wing molt duringmigration for accipiters and for Broad-winged Hawk.Here we provide accounts of 11 raptor species that actively molt flight feathers during migration,and we give synopses of the molt patterns for each species. These accounts are basedon our review of thousands of images from 15 hawk migration sites across North Americawhere we have studied and photographed raptors.w w w . a B a . o r g 35

M O L T I N R A P T O R SOur research has revealed the following insights:• At least six species of Western raptors actively molt flight feathers duringfall migration.• At least six species of Eastern raptors actively molt flight feathers duringspring migration.• Swallow-tailed and Plumbeous Kites actively molt flight feathers whilemigrating through Panama in the fall.• Typically, raptors in active molt during fall migration (August–November)are replacing feathers among the outer five primaries.• Second-year birds actively molt during fall migration less frequentlythan older adults. Second-year birds actively molting are often females,and are probably breeders from the previous summer.The results presented here are based on a combination of more than 30years of raptor field observations as well as the inspection of more than40,000 raptor images. We encourage others to follow up on our work,and to provide additional quantitative support for our findings.Species AccountsAll raptors have ten functional primaries, with P1 the innermostand P10 the outermost. But there are fundamentaldifferences in the pattern of flight feather replacementin the hawks (Accipitridae) and vultures (Cathartidae)vs. falcons (Falconidae). Hawks and vultures molt fromthe innermost primary (P1) sequentially outward to theoutermost primary (P10), and falcons start in the middleprimaries (P4) and replace feathers in both directions. Inmany large species, not all feathers are replaced each year,resulting in a stepwise replacement of flight feathers in which severalwaves of molt occur simultaneously. In larger raptors (for example, eagles),in which the flight feathers are not replaced completely during theprebasic molt, obligate stepwise molt occurs and is present from the secondprebasic molt forward (Pyle 2008; Howell in preparation).Fig. 2. Shown on this page and on p. 37 (lower left) are four of 640 SwallowtailedKites migrating past the Canopy Tower between noon and 3 p.m. Thebird on p. 37 is molting P4 and P5, and the bird on the center right of this pageis molting P6 and P7. Canopy Tower, Panama; 11 August 2008. © Brian Sullivan.Fig. 3. [opposite Page, Top right] This Swallow-tailed Kite is molting P6 andP7. Canopy Tower, Panama; 11 August 2008. © Brian Sullivan.Fig. 4. [opposite Page, Bottom right] This adult Plumbeous Kite is activelymolting flight feathers during migration. P3 is actively growing, and P4 hasbeen shed. Central Panama; 12 August 2008. © Brian Sullivan.36B i r d i n g • J u l y 2 0 0 9

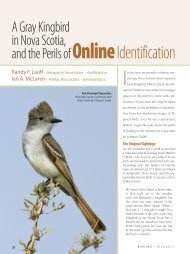

Turkey VultureDuring September and October, Turkey Vultures (and to a lesser extentBlack Vultures in the northern parts of their range) can be seenmolting during migration. Many Turkey Vultures are short-distancemigrants, whereas others migrate long distances. Western birds appearto molt more frequently during migration than Eastern birds(Fig. 1, p. 34).Swallow-tailed KiteDuring the period 10–16 August 2008, we observed migratingSwallow-tailed Kites in central Panama. The majority of migrantsthere were actively molting flight feathers (Figs. 2 and 3). Mostwere molting primaries among P3–P7, and most often P7. We observedevidence of molt in adults only. We suggest that long-distancemigrants such as Swallow-tailed Kites, which leave the U.S.shortly after breeding and show peak numbers on fall migrationthrough Panama by mid-August, may slowly replace primariesduring their southbound migration. It is unknown exactly whenprimary replacement starts, but Pyle (2008) notes that the definitiveprebasic molt begins on the breeding grounds in North Americaand is then suspended for migration, typically with P3–P6 suspendedin adults. Perhaps once birds near the wintering grounds,flight feather molt is again initiated, or perhaps after crossing theGulf of Mexico, they continue molting. Resumed primary moltmight also correspond to seasonal food abundance, but morestudy is needed. Kites have a low wing-load (ratio of body weightto wing surface area), which may allow them to undergo slow replacementof flight feathers during migration, as is seen in BlackTern (Zenatello et al. 2002).Plumbeous KiteLike the Swallow-tailed Kite, adult Plumbeous Kites were observedactively molting primaries during peak migration through Panamaw w w . a B a . o r g 37

M O L T I N R A P T O R S10–16 August 2008 (Fig. 4). Typical patterns involved actively growingP3–P6. It is unclear from the literature when Plumbeous Kites initiateprebasic molt, but it is reasonable to assume that they may be similar tothe congeneric Mississippi Kite in this regard, except that they molt duringmigration, which is not yet documented in Mississippi Kite. Accordingto Pyle (2008), Mississippi Kites initiate prebasic molt on the breedinggrounds and suspend it for migration. Much like Swallow-tailedKites, Plumbeous Kites likely reinitiate flight feather molt at some pointon their southbound migration, perhaps in anticipation of arrival on thewinter grounds, or when flight conditions are optimal—even if they haveto do so with compromised wing shape and aerodynamics. Or perhapsthey don’t suspend molt at all (like swallows), as they don’t cross any significantwater barriers.OspreyWe found at least three examples of Ospreys molting during migration,all from the Atlantic Coast (Figs. 5 and 6). Ospreys exhibited stepwisemolt, in which active flight feather molting is happening in multipleplaces simultaneously, with two waves of active molt occurring in theprimaries, one starting at P6 or P7 and the other at P1. Ospreys initiatethe definitive prebasic molt (annual complete molt after breeding) on thebreeding grounds, typically suspend for migration, and then resume onthe winter grounds (Pyle 2008). It is unclear whether the birds we observedwere in the process of suspending prebasic molt for migration orperhaps were nearby breeders finishing their molt at the beginning of fallmigration. More study is needed.Sharp-shinned HawkIn contrast to the larger Cooper’s Hawks, Sharp-shinned Hawks exhibitactive molt during migration only infrequently, since they typically com-38B i r d i n g • J u l y 2 0 0 9

plete molt prior to migration. It is possible thatlong-distance migrant accipiter speciesdon’t typically molt while migrating. Perhapsdue to the Sharp-shinned Hawk’smore northerly breeding distributionand longer migration, active molt wasonly noted in individuals migratingthrough the Intermountain West (Fig.7). Perhaps individuals breeding farthersouth than the majority of the populationhave shorter migrations and can thus affordto molt and migrate simultaneously.More study is certainly needed.Cooper’s HawkBased on our observations, we found thatCooper’s Hawks are the most frequently notedraptor actively molting during migration in theWest (Figs. 8 and 9). Although other speciesseem to molt less frequently during migration,molt during migration appears to be a regularpart of the Cooper’s Hawk’s life cycle, at leastfor Western montane breeders. Cooper’s Hawksare often seen completing their prebasic moltduring September and October, typically moltingthe outer primaries and secondaries, alongwith a few rectrices. Some adults, however, areobserved earlier in their prebasic molt cycle,growing middle primaries and initiating tailmolt (Fig. 9).Fig. 5. [Top left] This adult Osprey is molting P5 and P9.Cape May Point, New Jersey; 29 September 2003. © Jerry Liguori.Fig. 6. [Bottom left] This adult Osprey is molting P5–P6and P1–P2 in two waves of a “stepwise” molt pattern.Kiptopeke State Park, Virginia; 15 September 2005.© Brian Sullivan.Fig. 7. [right] This adult Sharp-shinned Hawk is activelymolting its tail and flight feathers. The central tail feathers aswell as a middle secondary and the middle primaries are inmolt. Wasatch Mountains, Utah; 29 April 2002. © Jerry Liguori.w w w . a B a . o r g 39

M O L T I N R A P T O R SNorthern GoshawkNorthern Goshawks are rarely seen actively molting during migration(Fig. 10). Being a larger species with a more protracted molt and heavierwing loading, the Northern Goshawk perhaps has little to gain by undergoingmolt during its relatively short migration. The species may followa strategy of molting on the breeding grounds throughout the longnesting cycle, and then suspending if needed, leading to stepwise replacementof flight feathers after the second year (Pyle 2008).Broad-winged HawkAdult Broad-winged Hawks are rarely observed molting during fall migration;in fact, we found only one photograph of an adult in molt, at Veracruz,Mexico. Only a few such birds have been seen there in early October—fewerthan one in a thousand (Howell, personal communication).Pyle (2008) notes that definitive prebasic molt can be completed eitherduring southbound migration or on the winter grounds in after-secondyearbirds. Northbound second-year birds in spring often start their flightfeather molt (beginning with the inner primaries and central tail feathers)in late April to early May, when they are seen in large numbers alongor crossing the Great Lakes (Fig. 11).Swainson’s HawkLike Broad-winged Hawks, adult Swainson’s Hawks are rarely seen moltingduring fall migration. Broad-winged and Swainson’s Hawks are thelong-distance migration champions of the genus Buteo, and perhaps dueto their extended migration, neither actively molts with regularity duringfall. Like other migrant buteos, however, second-year Swainson’s Hawksin spring migration can be seen molting inner primaries at the onset oftheir second prebasic molt in March to early May (Fig. 12).Red-tailed HawkIn the West, adult Red-tailed Hawks are often seen molting during fallmigration (Fig. 13), especially among populations using mountainridges. Most adults are at the end of the definitive prebasic molt atthis time, typically replacing outer primaries, secondaries, andFig. 8. [left] This adult (after-second-year) Cooper’s Hawk ismolting P9, S1, S5, and r2–r5. Wasatch Mountains, Utah;21 September 2008. © Jerry Liguori.Fig. 9. [Top right] This adult (after-second-year) Cooper’s Hawkis molting P6, S1, and r1–r6. Goshute Mountains, Nevada;3 October 1998. © Jerry Liguori.Fig. 10. [Bottom right] This adult (after-second-year) NorthernGoshawk is molting S1 and r3–r4. Goshute Mountains, Nevada;7 October 1999. © Jerry Liguori.40B i r d i n g • J u l y 2 0 0 9

tail feathers during southbound migration. Second-yearbirds may be seen initiating their secondprebasic molt during spring migration across NorthAmerica.Ferruginous HawkFerruginous Hawks are short-distance migrants, andthey rarely molt during migration. In spring, however,migrant second-year birds can be seen beginning primaryand tail molt, and adults can sometimes be seenmolting P8–P10 (Fig. 14).Golden EagleSecond-through-fourth–year Golden Eagles are frequentlyseen actively molting flight feathers during fallmigration in the montane West (Fig. 15). Second-yearbirds are often initiating their second prebasic molt atthis time, with S1 and S2 erupting, whereas third-yearand fourth-year Golden Eagles are typically nearingthe end of their prebasic molt, often replacing outerprimaries, secondaries, and tail feathers. Adult GoldenEagles are rarely seen molting during fall migration. Inspring, second-year birds can be seen beginning theirflight feather molt as early as mid-April.w w w . a B a . o r g 41

M O L T I N R A P T O R SPeregrine FalconAdult Peregrine Falcons often possess two ages of flightfeathers at a time, but it is uncommon to see them in activemolt during fall migration. Adult Peregrine Falcons that domolt flight feathers during fall migration (Fig. 16) may be individualsthat have experienced a difficult or energy-expensivebreeding season. Peregrines are excellent fliers, equally adept atboth powered and soaring flight. As such, small gaps in the wingsmay be tolerable during migration. In spring, second-year birds can beseen molting flight feathers on migration as early as April. Juvenile Peregrinesbegin to replace body feathers as early as February, unlikemost juvenile raptors, which start body molt in April.DiscussionAre These Molting Birds True Migrants?One complication is that some of the birds observed at hawk watches areresidents. How do we know that hawks observed in their prebasic moltare true migrants, as opposed to local residents? Although it is true thatresident birds are observed at many migration sites in North America,skilled observers can separate them from actual migrants based onplumage and behavior. Usually, it is straightforward to distinguish highflyingmigrants in sustained passage from local residents moving around.Local raptors at migration sites typically consist of one or two pairs; thesheer volume of birds seen at migration sites indicates that nearly all aremigrants. However, there are coastal sites, such as the Marin Headlandsjust north of San Francisco, Curry Hammock along the FloridaKeys, and Cape May, where local birds are known to wanderback and forth repeatedly past the official count site.We know that several species do not winter at certainmigration sites (particularly in the montane West) due to42B i r d i n g • J u l y 2 0 0 9

the climate, habitat type, or elevation. The Goshutes hawkwatch in eastern Nevada is one of those sites. Residentspecies include single pairs of Northern Goshawks, RedtailedHawks, Golden Eagles, and Peregrine Falcons. Theseresidents are seen regularly from mid-August to late Septemberbut depart thereafter. The high number of raptors observedand captured at the Goshutes indicates that almost allobserved are indeed migrants. Resident adults are wise toplastic owl decoys and trapping operations, and they arenearly impossible to catch. The same can be said for Swallowtailedand Plumbeous Kites migrating south through Panamain August. While some resident kites may be involved, kettlesof 100+ moving quickly past at high elevation are indicativeof migrants. Migrant Ospreys, especially along the AtlanticCoast, can be more difficult to discern since they overlapwith breeders that congregate along the coast for days ata time in September before moving south.Fig. 11. [Top left] This second-year light-morphBroad-winged Hawk is molting P2–P4 and r1.Brockway Mountain, Michigan; 16 May 2002.© Michael Shupe.Fig. 12. [Bottom left] This second-year lightmorphSwainson’s Hawk is molting P1–P4.Wasatch Mountains, Utah; 11 May 2003.© Jerry Liguori.Fig. 13. [Below] This adult Red-tailed Hawkis molting its outer primaries, middle secondaries,and rectrices. Wasatch Mountains, Utah;28 September 2007. © Jerry Liguori.More Questions than AnswersThe relationships between active flight feather molt and otheravian biological processes require further study, and herewe can only put forth theories. Many long-distance migrantraptors do not appear to molt and migrate simultaneouslywith regularity, but patterns of migration distance and moltare still unclear. Pyle (2008) delineates molt timing for NorthAmerican raptors. Many species apparently start their definitiveprebasic molt on the breeding grounds, suspend molt formigration, and then complete wing molt on the winteringgrounds. A few scenarios might explain the high proportionof Western migrants actively molting during migration. Perhapsthey are late breeders, in the process of suspending acww w . a B a . o r g 43

M O L T I N R A P T O R Stive molt during the first days of migration. Alternatively, they could beshort-distance migrants nearing the winter grounds and resuming theirprebasic molt. We hypothesize that late-breeding, high-elevation, montanepopulations of Western migrant raptors may lack the time to completemolt prior to fall migration; thus, they molt and migrate simultaneously.The effects of poor aerodynamics may be ameliorated partly on raptorsthat primarily use ridges for lift, as opposed to those primarily usingthermal updrafts. More study is needed to find the answers. Other interestingquestions worthy of further exploration include the following:• Is extended molt timing related to a presumably later montane breedingseason?• Is migration distance a factor in determining whether a species orpopulation molts during migration?• Do migratory patterns differ among molting and non-moltingbirds? For example, do long-distance migrant populations ofSharp-shinned and Cooper’s Hawks suspend molt during migration,whereas short-distance migrant populations do not?• And if so, where do these populations breed and winter, andwhat are the biological reasons for these differences?• Are food availability and molt during migration related?ConclusionsMany raptors actively molt during migration,especially in western North America. Aswe learn more about molt and its true physiologicalcosts, we may better understand why certainspecies molt and migrate simultaneously whileothers do not. With the help of birders and ornithologistswho observe, document, andstudy molt, we may indeed find the answersto these questions in the future, and we44B i r d i n g • J u l y 2 0 0 9

will undoubtedly work out many new puzzles in the process.AcknowledgmentsWe thank Steve N. G. Howell for inspiring the development ofthis manuscript, and for shedding light on the process of moltin general. Allen Fish and Buzz Hull of Golden Gate Raptor Researchprovided valuable input from West Coast banding sitesat Marin Headlands, <strong>California</strong>.Literature CitedClark, g.a. 2001. Form and function: The external bird, pp. 3.1–3.56 in: S. Podulka, r.rohrbaugh, and r. Bonney, eds. Handbook of Bird Biology. Cornell laboratory ofornithology, ithaca.Elphick, C., J.B. dunning, and d.a. Sibley. 2001. The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior.Knopf, new york.liguori, J. 2000. identification review: Sharp-shinned and Cooper’s Hawks. Birding32:428–433.liguori, J. 2004. How to age golden Eagles. Birding 36:278–283.liguori, J. 2005. Hawks From Every Angle. Princeton university Press, Princeton.liguori, J. 2009. Hawks at a Distance. Princeton university Press, Princeton.Payne, r.B. 1972. Patterns and control of molt, pp. 104–155 in: d.S. Farner and J.r.King, eds. Avian Biology, vol. 2. academic Press, new york.Pyle, P. 2008. Identification Guide to North American Birds, Part II: Anatidae to Alcidae.Slate Creek Press, Bolinas.Tordoff, H.B., and r.M. Mengel. 1956. Studies of birds killed in nocturnal migration.University of Kansas Publications, Museum of Natural History 10:1–44.Zenatello M., l. Serra, and n. Baccetti. 2002. Trade-offs among body mass andprimary molt patterns in migrating Black Terns (Chlidonias niger),pp. 411–420 in: C. Both and T. Piersma, eds. The Avian Calendar:Exploring Biological Hurdles in the Annual Cycle—Proceedingsof the Third Conference of the European OrnithologicalUnion, Groningen, August 2001 (Ardea, vol. 90).Fig. 14. [left] This adult light-morph FerruginousHawk is molting its primaries. Wasatch Mountains,Utah; 4 May 2002. © Jerry Liguori.Fig. 15. [Top right] This third-year Golden Eagle is moltingP2 and P8. Wasatch Mountains, Utah; 30 September2005. © Jerry Liguori.Fig. 16. [Bottom right] This adult Peregrine Falcon is molting P1, P2, P3,and P7. Wasatch Mountains, Utah; 24 September 2006. © Jerry Liguori.w w w . a B a . o r g 45