A magazine of lunar topographic studies Vol. 17 No. 2 December 2008

A magazine of lunar topographic studies Vol. 17 No. 2 December 2008

A magazine of lunar topographic studies Vol. 17 No. 2 December 2008

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

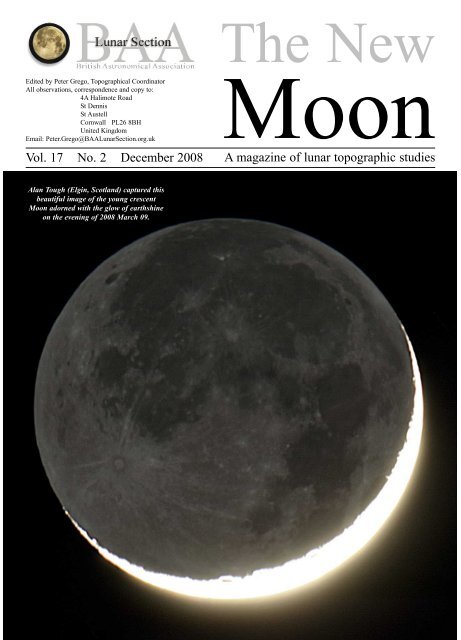

Edited by Peter Grego, Topographical CoordinatorAll observations, correspondence and copy to:4A Halimote RoadSt DennisSt AustellCornwall PL26 8BHUnited KingdomEmail: Peter.Grego@BAALunarSection.org.uk<strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>17</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 2 <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>The NewMoonA <strong>magazine</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>lunar</strong> <strong>topographic</strong> <strong>studies</strong>Alan Tough (Elgin, Scotland) captured thisbeautiful image <strong>of</strong> the young crescentMoon adorned with the glow <strong>of</strong> earthshineon the evening <strong>of</strong> <strong>2008</strong> March 09.

Bruce Kingsley’s image <strong>of</strong> the Altai Scarp, taken on <strong>2008</strong> <strong>No</strong>vember <strong>17</strong> using a 280 mm SCT and Skynyx 2-0 CCD.ContentsPapers3 The lesser-known nomenclature <strong>of</strong> the crater Gassendi Nigel Longshaw6 Beginning <strong>lunar</strong> imaging Maurice Collins821Geology <strong>of</strong> the Rimae HippalusFeatures <strong>of</strong> the young Moon’s terminatorPhil MorganPeter GregoObservations11 Agatharchides A region Phil Morgan12 Agatharchides A region Phil Morgan13 Agatharchides A region Phil Morgan14 Hippalus, Campanus and Rimae Hippalus Grahame Wheatley15 Hippalus / Poisson Peter Grego16 Messier and Messier A / Wrottesley Peter Grego<strong>17</strong> Region west <strong>of</strong> Marius Colin Ebdon18 Darwin Colin Ebdon19 Darwin Peter Grego /Phil Morgan20 Grimaldi and the ‘Miyamori Valley’ Phil Morgan24 Bailly / waxing gibbous Moon Sally RussellImages12Young <strong>lunar</strong> crescent with earthshinePiccolomini and the Altai ScarpAlan ToughBruce Kingsley23 15 day Moon, supersaturated Maurice CollinsPage 2 The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>

The lesser-known nomenclature <strong>of</strong> thecrater GassendiNigel LongshawSELDOM does one comeacross a <strong>lunar</strong> featurewhich has received as muchattention as the great ruinedcrater Gassendi situated onthe northern shores <strong>of</strong> theMare Humorum. As T. G. E.Elger (1836-97) wrote underSelenographical notes inThe Observatory (1890),“Mainly owing, it may besurmised, to the exceptionallyinteresting variety <strong>of</strong>detail on its floor, Gassendimay, next to Plato, claim tobe more favoured in thisrespect than any other formation.During the last 40years many distinct representations,<strong>of</strong> a more or lessvaluable type, haveappeared in various forms,mostly executed with a viewto display the marvelloussystem <strong>of</strong> clefts which ramifyamid the ridges and hillsin the interior and to drawattention to the equallyremarkable character <strong>of</strong> theborder and its adjuncts.”Named by GiovanniBattista Riccioli (1598-1671) using the spellingGassendus in honour <strong>of</strong> the French theologianand astronomer (1592-1655) thecrater forms an integral part <strong>of</strong> anydescription <strong>of</strong> this area <strong>of</strong> the Moon andwas described at length by many <strong>of</strong> theearly selenographers. Debate has ragedfrom the interpretation <strong>of</strong> its interior featuresto the forces which have shaped itsmorphology, it has been the site <strong>of</strong> severalTLP reports, P. Moore records in his Guideto the Moon (1953) that H. P. Wilkins(1897-1960) recorded a possible meteoricimpact observation on 1951 May <strong>17</strong> whenhe saw a ‘bright’ speck inside Gassendiwhich lasted one second and left a glowfor perhaps two seconds more. One authoreven claimed Gassendi’s central mountainsrepresent a giant letter ‘E’ ‘as perfectas if drawn by an architect’ suggestive <strong>of</strong>intelligent life resident on the <strong>lunar</strong> surface!On reading observational reports andpapers in relation to this formation oneThe New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>A sunrise study <strong>of</strong> Gassendi by E.Stuyvaert made on 1879 <strong>No</strong>vember 24.From the Annals de l’Observatoire deBruxelles, <strong>Vol</strong>ume 4, 1883.Gassendi, in all its‘telescopic glory’ asdepicted by E. L. Trouveloton Plate 20 <strong>of</strong> the Annals<strong>of</strong> the Harvard CollegeObservatory (1873).comes across nomenclaturewhich has been appended toGassendi and its surroundings,nomenclature whichhas never been <strong>of</strong>ficiallyadopted yet in itself is worthrepeating as it adds a littlemore interest to the timespent at the eyepiece andreminds us <strong>of</strong> those selenographersto which we owe agreat deal. It is also apparentthat the formation forms thesubject <strong>of</strong> many observationaldrawings which havebeen published in the pasthowever I thought it wouldalso be useful to reproducesome <strong>of</strong> the lesser-knownrenditions made by authorswhose work seldom finds itsway into the mainstream literatureor lies buried inpapers seldom referred to inthe present day.One <strong>of</strong> the earliest <strong>studies</strong><strong>of</strong> the feature was by John Philips (1800-74) and was published in <strong>Vol</strong>ume 158 <strong>of</strong>the Philosophical Transactions <strong>of</strong> theRoyal Society (1869) illustrating his paper<strong>No</strong>tices <strong>of</strong> some parts <strong>of</strong> the surface <strong>of</strong> theMoon. A geologist, Philips first observedthe Moon through the great Rosse reflector,an experience so pr<strong>of</strong>ound that ‘thereafterastronomy largely engaged his attention’according to Sheehan and Dobbins inEpic Moon. Philips described the telescopicappearance <strong>of</strong> Gassendi in some detailusing terminology later elaborated on byE. Neison (1851-1938) in his 14 pagemonograph on Gassendi published in theAstronomical Register <strong>Vol</strong>ume 11 (1873).According to Philips the walls <strong>of</strong> Gassendiare ‘everywhere rugged and fissured’,with the highest point being ‘on the eastern[classical orientation] border (9000feet according to Madler) where a sort <strong>of</strong>lacuna [hollow], rather than a crater occursin the middle <strong>of</strong> the crest’. This becomesPage 3

Above: A rare high sun study <strong>of</strong> Gassendi by H. Tompkins whichappeared in the English Mechanic, number 2618, 1915 May 28.The curious appearance <strong>of</strong> the three bright circular featureswould be worth checking under similar lighting these mayrepresent the central peaks and the two craters on the floorindicated on Trouvelot’s drawing.‘The Lacuna’ in Neison’s later paper and isdescribed as being ‘some 8 miles inextreme length and 4 in breadth, is notdeep, but <strong>of</strong> very irregular shape; andbears the appearance <strong>of</strong> being a space onthe wall enclosed by two ridges, ratherthan anything else’. Philips also describesthe northern part <strong>of</strong> Gassendi as beingcomposed <strong>of</strong> a ‘confluence <strong>of</strong> small ridgesfrom the interior, directed towards thespoon-shaped crater, marked A onMadler’s map’. Taken up by Neison thisbecomes the ‘spoon’ crater beingdescribed as ‘thirteen miles long by tenbroad is very deep, having very steep interiorslopes nearly 4000 feet deep: and fromthe walls several spurs or plateau’s project’.T. W. Webb (1806-85) wrote in correspondencewith W. R. Birt (1804-81) in1871 that he ‘ascertained one curious feature,the whole wall once occupying, as wemay suppose, the breach betweenGassendi and the ‘spoon’, has rolled downinto the interior <strong>of</strong> Gassendi and extendsas an ill-defined mass, half way to the central[mountain] group’.Exterior to the westernwall there is amountain spur un<strong>of</strong>ficiallyknown as the‘Percy Mountains’, aname proposed by W.R. Birt in his paperentitled On the extension<strong>of</strong> <strong>lunar</strong> nomenclature,MNRAS volume24 p.19-20,<strong>No</strong>vember 1863.Described by Elger as‘the bright highlandsextending east <strong>of</strong>Gassendi towardsMersenius, formingthe north eastern border<strong>of</strong> the MareHumorum. Theyabound in minutedetail — bright littlemountains and ridges— and include someclefts pertaining to theMersenius rill system;but their most noteworthy feature is thelong bright mountain arm, branching outfrom the eastern wall <strong>of</strong> Gassendi andextending for more than 50 miles towardsthe south east" (all directions in Elger’sreport are <strong>of</strong> course ‘classical’ orientation).This mountain spur is designated as suchby Hugh Percival (Percy in many <strong>of</strong> hispublished works) Wilkins on his MoonMaps published in 1960. Wilkins’ chartscontain many names which he attemptedto have ratified by the InternationalAstronomical Union and accepted as <strong>of</strong>ficialnomenclature, whilst the name ‘PercyMountains’ has never <strong>of</strong>ficially accepted,and was not <strong>of</strong> his own making, perhaps its<strong>of</strong>ficial recognition would be a fitting tributeto a much maligned selenographerwhose success in resurrecting the BAALunar Section following the Second WorldWar is all to <strong>of</strong>ten overlooked.Observing early sunrise on the PercyMountains with my Questar telescope on<strong>2008</strong> June 14 I thought the general form <strong>of</strong>the mountain range gave the appearance <strong>of</strong>a corkscrew in the small telescope at lowpowers, which perhaps sits rather well juxtaposedwith Philips’ ‘spoon’ further to thenorth! Under a low Sun using a smalltelescope there is a distinct triangularshaped shadow which is formed south <strong>of</strong>Below: Two vignettes <strong>of</strong> Gassendi made by the author on<strong>2008</strong> June 14 using a Questar 90 mm MCT x80 and x160.Seeing conditions: AIII.The ‘spoon crater’(Gassendi A) on the sameevening at colongitude45.28°. The triangularshapedshadow to thesouth (IAU) <strong>of</strong> the cratercan also be seen, muchas it was described by thecorrespondent in theEnglish Mechanic.Sunrise on the ‘PercyMountains’ at colongitude45.03°. The ‘lacuna’ isalso visible on the westernwall, as described byPhilips and Neison.Page 4 The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>

Gassendi A, this shadow is veryprominent, and appears somewhatstrange in its orientation.The surface relief to the eastappears a little shallow and it isdifficult to reconcile how such aprominent shadow might beformed. In the EnglishMechanic for 1910 June 10 onecorrespondent using a smallaperture telescope raised thequery ‘is there a high ridge <strong>of</strong>hills to the south <strong>of</strong> Gassendi Ato account for this long pointedshadow?’ The Times Atlas <strong>of</strong> theMoon indicates a ridge extendingto the south <strong>of</strong> Gassendi Acoupled with a rille or valley atits base; this ridge and lowerground to the west is probablyAbove: Drawing by George H. Leonard onp.153 <strong>of</strong> Someone Else is On Our Moon(1977), according to him ‘an outstandingexample <strong>of</strong> a perfect E on the floor <strong>of</strong>Gassendi’.Above: Typical <strong>of</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>. L. Weinek’sdelightful <strong>lunar</strong> vignettes, this exampleappears, along with others, in a littleknownbook The Amateur Astronomerby Gideon Riegler (1910) and recentlyrediscovered’ by Richard Baum.responsible for the lingering shadow spirein this region.With the level <strong>of</strong> attention this formationhas received in the past it would be feasibleto compile a detailed record <strong>of</strong> pastobservations, observations which resoundto the same controversies which plaguedformations such as Plato, Linné andEratosthenes. There is a level <strong>of</strong> truth inthe old selenographical saying ‘every manhis own Gassendi’, the ability to detect thefiner detail on the crater floor is dependentupon the instrument used, the illuminationat the time <strong>of</strong> the observation, seeing conditionsand <strong>of</strong> course the individualobserver, it is perhaps understandable whyso many differing interpretations anddrawings have be made, the result <strong>of</strong>which all to <strong>of</strong>ten suggested evidence forchanges on the <strong>lunar</strong> surface to thosereceptive to such ideas.The purpose <strong>of</strong> the preceding brief outlineis simply to bring to light and compilea number <strong>of</strong> long lost references and hopefullyencourage time to be spent at the eyepiece,once stationed at the telescope perhapsthe observer will take pleasure insimply recording what they can see, nomatter how strange a feature might initiallyappear, there is a good chance someonehas recorded something similar in the past.Left: An impressive study <strong>of</strong> Gassendiby J. W. Durrad on 25 January 1877,featuring on p.287 <strong>of</strong> WalterGoodacre’s book The Moon (1931)The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>Page 5

Beginning <strong>lunar</strong> imagingMaurice CollinsIhave recently been contacted by someonewho is interested in getting into<strong>lunar</strong> imaging, so I have been thinkingabout how I started, and giving him sometips. I thought may be worth sharing witha wider audience also in case there is anyoneout there who may be under theimpression that it is something way toodifficult or expensive for them to do.Firstly, do you have any sort <strong>of</strong> still digitalcamera that you use for family photos,holidays etc? Even a mobile phone camerawill work. If you do have a digital cameraand a good eye relief eyepiece <strong>of</strong> fairlylong focal length, you are all set to make astart. To begin with, a 25 mm to <strong>17</strong> mmeyepiece works well, but you can use up tothe limit <strong>of</strong> your telescope as long as thecamera can see through it.To take images, simply point the camerathrough the eyepiece, holding it by hand.To find the Moon with the camera lens,which can be a bit tricky, back <strong>of</strong>f a bituntil you see the bright spot <strong>of</strong> the Moon’simage on the cameras LCD screen, thenbring it down closer, but never actuallytouching the two lenses together (thoughno harm seems to be done if they dobriefly touch). Put one finger on the side <strong>of</strong>the eyepiece to steady the camera in place.It does not cause as much vibration as youwould expect and helps keep the Moon inthe field <strong>of</strong> view while taking the photo.Next, focus the telescope, as the focus <strong>of</strong>your eye at the eyepiece is different towhat the camera sees — for me it is a reasonablylarge change <strong>of</strong> telescope focus.Then use the camera’s zoom function(either digital or optical zoom is okay) t<strong>of</strong>rame out the black eyepiece field stop thatvignettes the image so that you only seethe <strong>lunar</strong> surface on the LCD <strong>of</strong> the camera,or at least only the edges <strong>of</strong> the frameshowing black. Gently press the shutterwhile holding your breath so as not to giggleanything. Oh yes, and remember todisable the flash! And voila, you shouldget a very nice image <strong>of</strong> the whole disk orpart <strong>of</strong> the Moon. If it looks too bright andsaturated, or too dim and grainy, check theEV settings on the camera and go up ordown a couple <strong>of</strong> settings to see whatworks best for that phase <strong>of</strong> Moon.Take lots <strong>of</strong> shots. Some will be blurry,some will be sharp, and the more you havethe better you will get a good one out <strong>of</strong> it.You can then process the images on yourcomputer to reduce the size to sharpen itand run the other image processing functionsover it to get it looking good.Sometimes the images look better ingrayscale, sometimes the good ones looknice in color.The technique described above is theeasy way into <strong>lunar</strong> astrophotography. Ifyour camera has an AVI movie mode, youPage 6 The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>

Maurice Collins’ image <strong>of</strong> the morning terminator on <strong>2008</strong> July 10, using a Fuji A800 (8.3 megapixel digicam) and 200 mm SCT.are even one step up and can just record avideo sequence which you can then stackusing a program like Registax to get reallysharp images that you can mosaic togetherif you like. This works for planets too.This way, I recently obtained a really niceshot <strong>of</strong> the crescent Mercury showing itsphase. You can even use a video camera,and convert the camera files to AVI andthen do the stacking. I have only used thisfor a <strong>lunar</strong> eclipse and thin crescent Moonbut it works, though a bit more work isinvolved.The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>The next step up (and easier way) is withthe a modified webcam or astronomicalCCD camera such as the Meade LPI(Lunar and Planetary Imager). <strong>No</strong> eyepiecesare needed, just the camera at primefocus and you can add a Barlow lens if youwish to increase the image scale.Think simple, and it usually works. Alsoif someone says to you: “You can’t do itthat way!” ask “why not?” Break the rules(if there are any hard and fast ‘rules’) andexperiment to see if it works. You don’tyou need brackets and fancy CCD camerasto do <strong>lunar</strong> astrophotography. If you havethem, all the better, but if you don’t, <strong>lunar</strong>imaging is still something you can do.I now use the Meade LPI to do my <strong>lunar</strong>imaging, and much <strong>of</strong> it is done remotely,but it wasn’t too long ago that I was usingthe simplest methods outlined here to takepictures <strong>of</strong> the Moon, so before I forget mybeginnings I thought it worth sharing withothers. I hope this helps someone in gettingstarted who would otherwise not think<strong>of</strong> trying it, using gear they may alreadyhave around home.Page 7

Geology <strong>of</strong> the Rimae HippalusPhil MorganTHE Mare Humorum (Sea <strong>of</strong> Moisture)is a circular basin roughly 400 kilometresin diameter, dating to the Nectariangeological period <strong>of</strong> <strong>lunar</strong> history, and likethe other circular Maria is a site <strong>of</strong> a positivegravity anomaly. In the late Imbrianera its interior was flooded by mare lavaproducing fine arcuate wrinkle ridges, particularlyaround the eastern half <strong>of</strong> thebasin, probably as a result <strong>of</strong> compressivestress. This compression produced a correspondingzone <strong>of</strong> tension around theperiphery <strong>of</strong> the basin, the results <strong>of</strong> whichwe can see today as a series <strong>of</strong> (mostly)arcuate rille systems, namely the RimaeAgatharchides, Hippalus, Mersenius andDoppelmayer. This article deals with theRimae Hippalus, in particular the regionaround the small crater Agatharchides A.Formed by crustal dilation and tectonicmovement <strong>of</strong> crustal blocks, the RimaeHippalus are a roughly parallel series <strong>of</strong>graben-type rilles that mark the easternboundary <strong>of</strong> the basin spanning a distance<strong>of</strong> some 250 kilometres. Best observed ataround colongitude 35° onwards at sunriseand about colongitude 200° onwards atsunset.Starting at the north at the old floodedcraters Agatharchides and Agatharchides Pas a trio <strong>of</strong> rilles, the Rimae Hippalus IIand III skirt around the crater <strong>of</strong> that name,whilst the Rima Hippalus I slices throughthe centre <strong>of</strong> it in a beautiful concentric arcas it heads towards the south. At this pointthey are joined by the shorter rille RimaHippalus V, and all peter out as they strikesouth towards the crater Vitello.Observationally, most <strong>of</strong> my <strong>studies</strong>have been centered round the small, butinteresting (18 km) crater AgatharchidesA. This crater was named Moore byWilkins, and in 1949 Patrick Moore (nowSir Patrick <strong>of</strong> course) discovered twodusky bands running up the inner west(IAU) wall <strong>of</strong> the crater using a 6-inchrefractor. Since this crater sits directly ontop <strong>of</strong> the Rima Hippalus II and there is nosign <strong>of</strong> the rille cutting through either thecrater floor or its ramparts, we can assumethat the crater is the younger <strong>of</strong> the two(though it’s not always emphatically thecase that that one feature overlying anotheris always the younger!)To the west <strong>of</strong> Agatharchides A the RimaHippalus II shows a considerable displacement.This break is not visible under earlysunrise conditions as it is hidden by thelong shadows striking westwards fromAgatharchides A. Just south <strong>of</strong> this displacementthe rille forks into two and theeastern branch runs northwards into thesouthern outer rampart <strong>of</strong> A. In fact thisarea is the centre <strong>of</strong> a zone <strong>of</strong> fracturingthat is radial to Mare Humorum and iscomplimentary to the more obvious concentricarcuate Hippalus rille system.Another dislocation sits directly underAgatharchides A. As the Rimae HippalusIII heads south it meets the north outerrampart <strong>of</strong> Agatharchides A, passes underthe west (IAU) wall and emerges to thesouth, curving to the west just east <strong>of</strong> theRima Hippalus III dislocation mentionedabove. Lunar maps show the RimaHippalus III continuing on south <strong>of</strong>Agatharchides A, but I believe this section<strong>of</strong> the rille was never connected directly tothe shorter north segment, although visuallyit does appear to do so to the Earthbased observer. Similar fractures can beseen along the Rima Hippalus I insideHippalus itself, and to the north. All aredextral (right handed) in their displace-The Hippalus area, mapped by Walter Goodacre in 1910 (left) and Percy Wilkins in 1946 (right). From the collection <strong>of</strong> Peter Grego.Page 8The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>

ment. Just east <strong>of</strong> Agatharchides A anothershallow rille runs south and is bisected bythe Rima Hippalus IV. This rille is als<strong>of</strong>ractured along its length, herringbonefashion (see Lunar Orbiter image IV-132at right).As the Rima Hippalus III strikes southwardsbeyond Agatharchides A, the rilleskirts a small hill, recorded sometimes ashaving a summit craterlet. Observationallyat least, the rille at this point has a pronouncedbend eastwards. It is interestingto note that this sharp ‘bendaround’ is notconfirmed by the overhead Lunar Orbiterimages, although many observers haverecorded it as such in the past. Rükl alsoshows no great curvature here, though forthe most part he based his charts on theLunar Orbiter photos. This apparent <strong>lunar</strong>illusion is shown well on my drawing <strong>of</strong>2004 March 1 (see p.12). Allowing for thisrille’s position on the <strong>lunar</strong> sphere, some30° west <strong>of</strong> the Moon’s central meridian,and the resultant distortion in its shape(curvature), we would expect the bend <strong>of</strong>the rille around the small hill to appear lessto the Earth bound observer, and not, as isapparently the case, much more. Further<strong>studies</strong> by myself show that a section <strong>of</strong>the eastern half <strong>of</strong> the hill has fallen orslumped into the bottom <strong>of</strong> the rille.Whilst the extra shadow that this fallensection casts eastwards could explain anapparent increased curvature <strong>of</strong> the rille atAbove: Lunar Orbiter photo IV-132, at col. 48.66°. Credit: NASA.Below: Part <strong>of</strong> LAC 93 (featured on p.79-80 <strong>of</strong> The Times Atlas <strong>of</strong> the Moon) showingMare Humorum and Rimae Hippalus. <strong>No</strong>rth is at top. Credit: NASA.The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>Page 9

sunset, it couldn’t do so at sunrise. In factthe shadows falling eastwards from thehigher part <strong>of</strong> the hill at sunset largelyobscure any chance observing this illusion at<strong>lunar</strong> dusk.Other features <strong>of</strong> interest in this regioninclude the narrower Rima Hippalus IV. Thismuch more difficult to observe rille runsnorth eastwards diagonally from the aforementionedsmall hill for some distance, andis a line <strong>of</strong> demarcation between two areas<strong>of</strong> differing tone. To the south <strong>of</strong> this, andalmost parallel to it, is another even finer,and unnamed difficult to observe rille. Asthe Rima Hippalus II and III run north fromAgatharchides A, there is a fairly broad butshallow rille connecting the two diagonallyat roughly the same angle as the RimaHippalus IV further south. This is shownfaintly on p.80 <strong>of</strong> The Times Atlas <strong>of</strong> theMoon (LAC 94).To sum up, this is a particularly interestingregion <strong>of</strong> the Moon to study, and one doesn’tneed a particularly large telescope toobserve most <strong>of</strong> the finer features mentionedabove. Perhaps those observers that likeCCD imaging as well as a bit <strong>of</strong> a challenge,could attempt to unravel and explain themystery <strong>of</strong> the ‘bendaround’ rille?Right: Part <strong>of</strong> LAC 94 (featured on p.79-80<strong>of</strong> The Times Atlas <strong>of</strong> the Moon) showingthe area to the east <strong>of</strong> Hippalus and most <strong>of</strong>the features mentioned in the article. <strong>No</strong>rthis at top. Credit: NASA.Below: Detail from a map <strong>of</strong> the Hippalusarea by the great observer P. B.Molesworth (1867-1906), presented withnorth at the top for easier comparison withthe LAC map.Page 10 The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>

The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>Page 11

Page 12 The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>

The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>Page 13

Hippalus, Campanusand Rimae HippalusHippalus, Campanus and Rimae Hippalus2000 January 1620:05 to 21:15 UTCol. 34.6° to 35.2°Moon’s age 10.1 dLunation 953Seeing: AII, AI at timesTransp: Generally good, clear and cold240 mm f/9.8 Newtonian x235Grahame WheatleyLocation: Long Eaton, <strong>No</strong>ttingham, UKPage 14 The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>

Hippalus<strong>2008</strong> <strong>December</strong> 720:10 to 20:45 UTCol. 31.6° to 31.9°Moon’s age: 10.1 dLunation 1063Seeing: AII-III, some mist200 mm SCT x200, binoview, integrated lightPDA sketch (north at top), enhanced inPhotoPaint immediately indoorsPeter GregoLocation: St Dennis, Cornwall, UK<strong>No</strong>tes: Hippalus had just begun to emerge fromthe morning terminator. I was intrigued by thenetwork <strong>of</strong> faintly illuminated patches on thefloor, which was mainly in shadow. <strong>No</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> theRimae Hippalus were immediately obviousowing to the shallow illumination and abundance<strong>of</strong> shadow. A broad dark band <strong>of</strong> shadowran from north to south across Hippalus andextended further south, blending into the terminator.Hippalus’ northwestern rim appeared asa bright line. To the southwest, the peaks <strong>of</strong> Promontorium Kelvin jutted out <strong>of</strong> the shadow, alongwith several peaks south <strong>of</strong> Hippalus. Another set <strong>of</strong> illuminated peaks could be seen north <strong>of</strong>Hippalus. A dusky tract where Rima Hippalus II lies was visible to the northeast betweenHippalus’ northeast wall and Agatharchides A, and only part <strong>of</strong> the Rima Hippalus III was visible.Poisson<strong>2008</strong> <strong>No</strong>vember 1901:40 to 02:15 UTCol. 162.7° to 163.0°Moon’s age 21.1 dLunation 1062Seeing: AII, clear skies300 mm Newtonian, x100 x200PDA sketch (north at top)enhanced in PhotoPaintimmediately indoorsPeter GregoLocation: St Dennis, Cornwall<strong>No</strong>tes: The unusual kidneybeanshape <strong>of</strong> Poisson is evidentlyvery ancient and overlainby several smaller craters,namely Poisson A and T in thenorth and west and Poisson U and V in the south. Poisson’s floor, most <strong>of</strong> which was illuminatedby the late afternoon sunshine, appeared somewhat hilly. A sizeable unnamed crater about 50 kmin diameter appeared to lie to the southeast <strong>of</strong> Poisson. Apianus lies just north <strong>of</strong> the area drawn,its southern edge depicted. To the far west is the eastern rim <strong>of</strong> Aliacensis.The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>Page 15

Messier and Messier A<strong>2008</strong> <strong>December</strong> 15-16 / 23:50 to 00:15 UTCol. 130.1° to 130.3° / Moon’s age 18.3 d /Lunation 1063 / Seeing: AII, some mist200 mm SCT x200, binoview, integrated lightPDA sketch, enhanced in PhotoPaint indoorsPeter Grego / St Dennis, Cornwall, UK<strong>No</strong>tes: Both craters were largely filled withshadow cast by their western rims. Messiercast a long twin-pointed shadow eastwardacross the mare for around 15 km. The internaleastern wall was not particularly brilliant.Messier A’s inner eastern wall was the brightestpart <strong>of</strong> the area depicted, a crescent withno discernable terracing or structure. It casttwin lobes <strong>of</strong> shadow around Messier’s northwesternand southwestern ramparts. The rayextending westward from Messier A was notprominent and its dual nature was not particularlyevident near to the crater. Subtle shadingwas observed elsewhere in the country aroundthe crater pair, with delicate fans <strong>of</strong> light anddusky albedo radiating out from both.Wrottesley<strong>2008</strong> <strong>December</strong> 15 / 00:20 to 00:55 UTCol. 118.1° to 118.4° / Moon’s age <strong>17</strong>.3 d/Lunation 1063 / Seeing: AII, clear and cold200 mm SCT x200, binoview, integrated lightPDA sketch, enhanced in PhotoPaint indoorsPeter Grego / St Dennis, Cornwall, UK<strong>No</strong>tes: Wrottesley was half filled with eveningshadow, its central peak showing as a singlebright dot. Some structure was discerned on itsinner eastern wall, in part radial shading linkedto deformities in the outline <strong>of</strong> the eastern rim.The northeastern part <strong>of</strong> the inner wall wasbright. East <strong>of</strong> Wrottesley was Petavius’ rim,inside the shadow <strong>of</strong> which was seen intricateslivers <strong>of</strong> illumination corresponding to highpoints in Petavius' inner wall terracing. A curvinglow ridge extended north <strong>of</strong> Wrottesley andconnected with an elongated crater shown nearthe top edge <strong>of</strong> the sketch. The area toWrottesley’s southwest was complicated, andwhat’s shown is only a general impression. Itappeared to consist <strong>of</strong> low ridges correspondingto an ancient and degraded crater over whichWrottesley is overlain. The plateau northwest <strong>of</strong> Wrottesley cast a dark curving shadow. Its heightswere complex and the main feature seemed to be a large depression like an old crater.Page 16 The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>

The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>Page <strong>17</strong>

Page 18 The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>

DarwinDarwin<strong>2008</strong> October 12 / 20:20 to 21:10 UTCol. 69.3° to 69.8° / Moon’s age 13.5 d /Lunation 1059 / Seeing: AII-III, slight mist200 mm SCT x200, binoview used,integrated lightPDA sketch, enhanced in PhotoPaint indoorsPeter Grego / St Dennis, Cornwall, UK<strong>No</strong>tes: A good libration for a general study <strong>of</strong>Darwin, a vast and ancient crater near thewestern limb. The crater was emerging intothe morning light during the session. Some <strong>of</strong>its northern floor was visible, in the form <strong>of</strong>what appeared to be a large area <strong>of</strong> raisedground, subtly shaded on its eastern face.Darwin's southern floor was completely coveredwith shadow, the southwestern rim beingvisible as a narrow, complex line <strong>of</strong> illumination.The dark-floored crater Crüger was visibleto Darwin's northeast. A narrow linearshadowed scarp ran from Darwin's northeasternrim, extending south and east <strong>of</strong> Crüger.Parts <strong>of</strong> the southern extension <strong>of</strong> RimaSirsalis was visible running from the southeasternrim <strong>of</strong> Darwin, north to de Vico A, withhints <strong>of</strong> it further north to Crüger A, but indistinctlyseen here.The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>Darwin<strong>2008</strong> October 12 / 21:30 to 22:15 UTCol. 70.2° to 70.5° / Moon’s age 13.5 d /Lunation 1059305 mm Newtonian, x400Phil Morgan / Tenbury Wells, Worcestershire,UKIt’s not <strong>of</strong>ten that three people, observing independently<strong>of</strong> each other, make visual <strong>studies</strong><strong>of</strong> the same feature on the same evening atabout the same time. This is what happenedon the evening <strong>of</strong> <strong>2008</strong> October 12, whenColin Ebdon (p18), Peter Grego (above, left)and Phil Morgan (above) depicted the largecrater Darwin as it emerged from the morningterminator. Libration was excellent on thisoccasion, with libration in latitude at around-03° 10’ and libration in longitude -05° 50’.Page 19

Page 20 The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>

Features <strong>of</strong> the young Moon’sterminatorPeter GregoMareHumboldtianumGaussPlutarchCannonNeperSchubertKastnerAnsgariusHecataeusThe New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>HumboldtLeft: TheMoon’s easternlibration zonecentred on90°E. FromNASA chartLPC-1.AMONG the thousands <strong>of</strong> <strong>lunar</strong> observationaldrawings to be found in the current archives<strong>of</strong> both the SPA Lunar Section and the BAA LunarSection’s Topographical Sub-section, it may surprisethe reader to learn that there are no detailedvisual depictions <strong>of</strong> features on the very young(sub-36 hour) <strong>lunar</strong> terminator. As far as imagery isconcerned, photographs <strong>of</strong> the young <strong>lunar</strong> crescentare usually rather indistinct and blurred.The narrow sliver <strong>of</strong> a sub-36 hour <strong>lunar</strong> crescentis not easy to spot. The observer’s location andlocal horizon, weather and atmospheric conditions,the season, timing <strong>of</strong> new Moon and the Moon’sangular diameter all have to combine favourably tomake the attempt worth trying. UK-basedobservers are most favourably placed to make thesearch for young <strong>lunar</strong> crescents during the spring,when the ecliptic makes its steepest angle to thewestern horizon. Since the Moon always lies closeto the ecliptic it will be at its highest above thehorizon after sunset, while the Sun drops quicklybelow the horizon and skies darken rapidly. Thehigher the Moon at sunset, the less atmosphericmurk its light has to compete with, and the observer’schances <strong>of</strong> discerning it are improved. Thecontrast between the dim crescent and the duskskies is not great, even under the clearest conditions;the presence <strong>of</strong> atmospheric haze will causeextinction near the horizon, reducing the chances<strong>of</strong> seeing this elusive phenomenon. It also helps toPage 21

have a Moon near perigee, since theorbital motion <strong>of</strong> the Moon is at its fastestand it will have moved further from theSun following new Moon in a given period<strong>of</strong> hours.The sub-36 hour Moon presents a dim,thin partial crescent shimmering with turbulence.Because the Moon is not a perfectsphere, the very young crescent neverextends to a full semicircular arc aroundthe limb — the shaded areas <strong>of</strong> high reliefon the Moon’s terminator are facing theobserver and block out some <strong>of</strong> the sunlitportions behind them, and this effect ismore pronounced towards the horns <strong>of</strong> thecrescent where the Moon is narrower.Andre Danjon (1890-1967) calculated valuesfor the ‘deficiency arc’ — the extent towhich the crescent varies from a semicircledepending on its elongation from theSun. A 180° crescent can only be seen atelongations exceeding 40°. Actually, atlarger elongations in which the Moonpresents a wider crescent, the deficiency is<strong>of</strong> a negative value, which produces an arcslightly longer than 180°, the ends <strong>of</strong> thecrescent extending to produce the phenomenon<strong>of</strong> ‘Saber’s Beads’ (see above).At elongations <strong>of</strong> less than 40°, the <strong>lunar</strong>crescent gradually gets smaller until, at anelongation <strong>of</strong> 7° the deficiency arc is also7°, and the illuminated portion <strong>of</strong> theMoon cannot be seen at all.When the Moon is under a day old, justbeing able to see the Moon is a feat initself, and it isn’t really possible to identifyany <strong>of</strong> the Moon’s features with certainty;observers might want to estimate thesize <strong>of</strong> the crescent and make a sketch <strong>of</strong>any peculiarities in its outline. Imagersmay record the phenomenon using digitalcameras, and perhaps they will even showthe earthshine on the Moon’s unilluminatedface. Half a day later, when the Moon isaround 36 hours old, it has become possibleto readily identify <strong>lunar</strong> features telescopicallyor by comparing an image to asuitable map.On <strong>2008</strong> September 1, at 06:55 UT,Maurice Collins (Palmerston <strong>No</strong>rth, NewZealand) managed to capture the 1.45 dayold crescent Moon as it came out <strong>of</strong> theclouds just 5° above the horizon (springtimein the antipodes). Using a 200 mmSCT (C8) and LPI CCD camera, Mauricecaptured a number <strong>of</strong> images and performeda manual mosaic in Photoshop.The result is an excellent image <strong>of</strong> the veryyoung crescent Moon in terms <strong>of</strong> theamount <strong>of</strong> clearly discernable <strong>topographic</strong>detail. The image is all the more valuablebecause libration for the eastern limb wasvery favourable at the time. A number <strong>of</strong>features have been identified on the image(see p.21).I would be interested in seeing moreobservational drawings and images <strong>of</strong> featureson the very young crescent Moon, so‘Saber’s Beads’. At the beginning <strong>of</strong>Lunation 1040 Nigel Longshaw(Chadderton, Oldham, UK) made thisobservation <strong>of</strong> the Moon’s southern cuspshowing a number <strong>of</strong> detached illuminatedpoints beyond the main crescent. Thesepoints <strong>of</strong> light, reminiscent <strong>of</strong> the solareclipse phenomenon <strong>of</strong> Baily’s beads,have been referred to as ‘Saber’s Beads’,after Stephen Saber, an American amateurastronomer who has drawn attention tothem. The phenomenon is easily visible afew days after new, but it is reportedlyvisible when the Moon is just a day old.Date: 2007 January 22Time: 18:35-45 UT Seeing: AIIIInstrument: 66 mm APO (WilliamOptics ZS 66 mm SD) x97<strong>No</strong>tes: The Moon’s southern cusp is<strong>of</strong>ten a beautiful sight during the first fewdays at the start <strong>of</strong> a lunation; however Icannot recall seeing so many ‘detached’illuminations in the past. The little refractordealt amiably with this difficult observation,and contrast remained excellent,despite poor seeing. Earthshine took on a‘smoky'’grey/green hue particularly to thesouthern pole and western limb.if you have made them in the past, pleasedo send them in. Such observations andimages, made at (or beyond) the limits <strong>of</strong>what might be considered acceptableobserving conditions, may bring to lightpreviously visually unreported <strong>topographic</strong>alfeatures. A Wratten #21 orange or#23A light red filter will help increase thecontrast between the twilight sky and thefaint <strong>lunar</strong> crescent (this applies to visualobservation as well as imaging).Features to attempt to look out for duringfavourable librations include the westernedge <strong>of</strong> the major crater Schrödinger andthe Vallis Schrödinger (neither <strong>of</strong> which Ihave read about actually being discernedvisually) extensions <strong>of</strong> the cusp in thesouth polar region beyond Amundsen, andshadows cast by the eastern borders <strong>of</strong>Mare Smythii, Mare Marginis, MareHumboldtianum and Belkovich and theshadows <strong>of</strong> the asemblage <strong>of</strong> infilledcrater-plains which makes up MareAustrale.Of course, the same elusivity applies tothe Moon’s western limb very late on inthe lunation, but under opposite circumstances.On the whole, however, sectionrecords for late lunation observations fromthe UK are much poorer in terms <strong>of</strong> quantity,but in terms <strong>of</strong> quality they tend to bebetter, since more dedicated and skilledobservers will tend to make the effort toobserve late on in the lunation.Page 22 The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>

Maurice Collins writes: Blue areas are high Titanium, reds are very-low Ti rocks. Mare Frigoris and the region in Imbrium aroundthe Apennine bench formation seem to be quite red and perhaps rich in these rocks. The reddish creamy rocks <strong>of</strong> the highlands east<strong>of</strong> Tycho underlying the younger rays and other ejecta there is quite interesting. The rays from Langrenus are quite startling.An invitation to joinThe BAA Lunar Section Topographical Subsection Yahoo GroupThe free and timely distribution <strong>of</strong> observations is important, and there’s only so much that canactually be published in the Lunar Section Circulars and The New Moon.A new Yahoo group has been set up for the BAA Lunar Section’s Topographical Subsection — aplace where members can post their observational drawings, share files and discuss mattersrelated to visual <strong>lunar</strong> observing. All visual <strong>lunar</strong> observers are invited to join us at:http://uk.groups.yahoo.com/group/baa<strong>lunar</strong>section-topography/At the time <strong>of</strong> writing the group has 16 members and more than 150 <strong>lunar</strong> observations havebeen posted there — thanks to all those who have joined!Peter GregoThe New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>Page 23

Bailly<strong>2008</strong> October 1221:00 to 22:00 UTCol. 69.7° to 70.2°Moon’s age 13.5 dLunation 1059105 mm OG, x240Sally Russell / UKBaillyWaxinggibbous Moon<strong>2008</strong> October 1121:20 to 22:30 UTCol. 57.7° to 58.3°Moon’s age 12.5 dLunation 105970 mm OG, x30Sally Russell / UKPage 24 The New Moon <strong>December</strong> <strong>2008</strong>