Cormorant - Wildlife Control Information

Cormorant - Wildlife Control Information

Cormorant - Wildlife Control Information

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

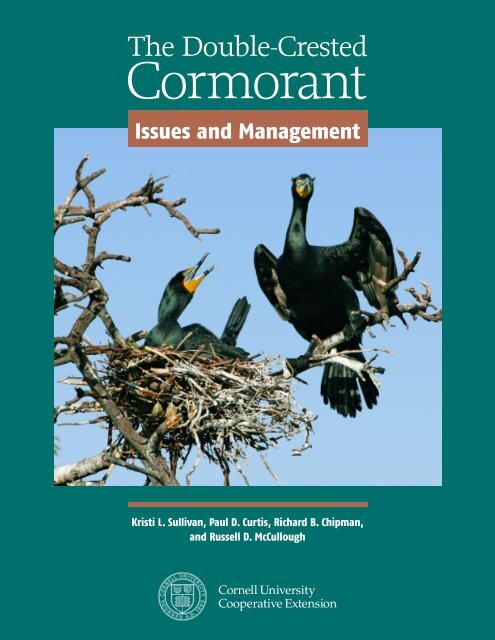

AcknowledgementsFunding for this publication wasprovided by the United States Fishand <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service. We thank ShaunaHamisch of the United States Fish and<strong>Wildlife</strong> Service; James Farquahar of the NewYork State Department of EnvironmentalConservation; Jeremy Coleman of CornellUniversity; Peter Mattison of Integral Consulting;Scott Barras and Travis DeVault of theUSDA, <strong>Wildlife</strong> Services, National <strong>Wildlife</strong>Research Center; and Milo Richmond of USGSNew Y0rk Cooperative Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> ResearchUnit for their review of this document.Their helpful comments and suggestionsgreatly improved this publication. Specialthanks to Phil Wilson for the design, layout,and production of this guide.Prepared byKristi L. Sullivan and Paul D. Curtis, Department ofNatural Resources, Cornell University; Richard B.Chipman, USDA APHIS, <strong>Wildlife</strong> Services; and RussellD. McCullough, New York State Department of EnvironmentalConservation, Bureau of FisheriesPublished byDepartment of Natural ResourcesCornell University, Ithaca, New YorkCopyright © 2006 All rights reserved.Cover photo by Joyce GrossThe views and conclusions contained in this documentare those of the authors and should not beinterpreted as representing the opinions or policiesof the U.S. Government. Mention of trade namesor commercial products does not constitute theirendorsement by the U.S. Government.

The Double-Crested<strong>Cormorant</strong>Issues and ManagementPreface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Biology and Natural History . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Description of the <strong>Cormorant</strong>. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Habitat. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Breeding and Nesting Behavior . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Migration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Food Habits and Feeding . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Concerns About <strong>Cormorant</strong>s . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Impacts on Recreational Fisheries. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Impacts on Aquaculture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15Effects on Vegetation and Habitat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15Impacts on Other Bird Species. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16Newcastle Disease. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17Recreation, Property Values and Tourism . . . . . . . . . . . 17Non-Lethal Management Options . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18Harassment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18Habitat Modification . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19Fisheries Management . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Lethal Management Options . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Nest Destruction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Shooting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22Regulation and Management Authority for <strong>Cormorant</strong>s . . . . . . . 23The United States Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service . . . . . . . . . . 23USDA APHIS <strong>Wildlife</strong> Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23State <strong>Wildlife</strong> Management Agencies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24New Strategies for Managing <strong>Cormorant</strong> Damage . . . . . . . . . . . 25Increased Local <strong>Control</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25<strong>Control</strong> around Aquaculture Facilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26Other Management Options . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26Adaptive Management . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27Additional Readings. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

3PrefaceThis bulletin is a comprehensiveguide to the issues surrounding thedouble-crested cormorant (Phalacrocoraxauritus), a species that has generateda tremendous amount of interest andcontroversy in recent years. The informationpresented is intended to help anglers, fishhatchery operators, fisheries and wildlifeprofessionals, lake association members,nature center personnel, Cooperative Extensioneducators, secondary school teachers,and the interested public find the informationneeded to understand both the complexityof issues involved, and the managementoptions available. Although conflicts withcormorants occur in other areas of the country,this bulletin focuses on populations of theinterior United States and the northeasternAtlantic coast.The double-crested cormorant is an interesting yet controversial bird.LEE KARNEY

4IntroductionEven though breeding populationsof the double-crested cormorant arepresent in many locations throughoutNorth America, this bird is neitherwell known nor widely recognized by thepublic. Unlike other more popular, captivatingwater birds like the Canada goose (Brantacanadensis) or common loon (Gavia immer), thedouble-crested cormorant is viewed by manyas a relatively uncharismatic species. Malignedfor centuries and persecuted for their fisheatinghabits, the cormorant has recentlybecome the center of controversy in regionswhere numbers have rapidly increased.Expanding populations have raised concernsabout adverse impacts cormorants might haveon other bird and fish species of special concern,declines in local fish populations, anddestruction of vegetation at nesting areas.Specific socioeconomic concerns include economiclosses from depredation at aquaculturefacilities, potential impacts on fishing-relatedbusinesses, loss of fish in private lakes, anddamage to trees on private property.Although double-crested cormorants arewidespread, some geographic areas have experiencedsignificant population growth andconflict, while others have not. The breedingrange of the cormorant is divided into five geographicareas—Alaska, the Pacific coast, thesouthern United States, the interior UnitedStates and Canada, and the northeast Atlanticcoast. Populations have been growing and expandingsince at least the 1980s in the interiorUnited States and Canada, northeast Atlanticcoast, and the southern United States. In thispublication, we focus on the interior and Atlanticcoast breeding populations, which breedand nest in the north, then migrate south towinter in coastal areas from Texas to NorthCarolina with significant concentrations inthe Mississippi delta region.Within the interior United States and Atlanticcoast regions, the occurrence and severityof cormorant impacts varies. For example,in the Great Lakes region the number of cormorantsincreased an average of 29 percentper year from 1970 to 1991, after which populationgrowth slowed. In some of these areascormorant populations may be at an all-timehigh. However, recent population increasesmay alternatively represent recovery toward

5pre-settlement numbers of cormorants insome regions, and a re-colonization in otherregions after a long period of absence.Recent population increases follow a dramaticdecline that occurred between the 1950sand 1970s, caused by the effects of human persecutionand chemical contamination fromDDT. <strong>Cormorant</strong> numbers began to rebound inthe mid-70s when DDT was banned, pollutioncontrol lowered the concentrations of toxiccontaminants in the bird’s food, food becamemore abundant throughout their winter andsummer ranges, and cormorants were givenprotection by both Federal and State laws.These factors allowed populations of theseadaptable birds to grow.COURTESY OF USDA, WILDLIFE SERVICES<strong>Cormorant</strong> numbers have increased after a dramatic decline from the 1950s to the 1970s.

6Biology andNatural HistoryDescription of the <strong>Cormorant</strong>The double-crested cormorant is along-lived, colonial-nesting water birdnative to North America. One of 38species of cormorants worldwide, andone of six species in North America, it is usuallyfound in flocks, and sometimes confused withgeese or loons when on the water (Table 1).Male and female cormorants look alike, havingblack plumage tinted with a greenish gloss onthe head, neck and underside. In breedingplumage, tufts or crests of feathers appear for aSTAN TEKIELAThe double-crested cormorant perches on trees, rocks, buoys, and other objects that overhang or project from water.

7Table 1Characteristics useful for field identification of Double-Crested <strong>Cormorant</strong>sversus Canada Geese or Common LoonsCanada Geese Common Loons Double-Crested <strong>Cormorant</strong>sColorBlack, gray, buff and white,dark head and neck, lighterbodyBlack and white, black backevenly patterned with white inbreeding seasonUniformly dark, or mottledbrown and gray breastNeck C-shaped curve, long Short, curved Snake-like curve, longBill Long, flattened at tip Heavy with pointed tip Slender, cylindrical, hooked tipTail Shorter than cormorant Very short Much longer than geese or loonsWing beat Slower than cormorant or loon Faster than geese or cormorant Slower than loon, somewhatmore rapid than geeseNeck in flight Held horizontal Held slightly lower thanhorizontalHeld slightly higher thanhorizontalPerching position Remains on ground Ungainly on land Upright posture with curvingneck, tail used as brace, wingsoften spread; prefers trees,rocks, and buoys that overhangor project from waterPosition on waterSwims with most of body abovewaterSwims low in waterBody often nearly submerged,neck, more erect than loons,bill pointed at upward angleSTAN TEKIELALEE KARNEYWENDY VANDYK EVANSCanada gooseCommon loonDouble-crested cormorant

8short time on either side of the head of adultbirds, giving them their name. Their black billsare slender and cylindrical with a hooked tipand sharp edges. They have black, webbed feetset well back on their body, a long curving neck,orange facial skin, and an orange throat pouchlike their pelican relatives (family Pelicanidae).Some one- to two-year-old juvenile cormorantsmay have grey or tan plumage on their neckand breast.Double-crested cormorants have a bodylength of 29 to 36 inches, a wingspan of about54 inches, and weigh four to six pounds. Onaverage, double-crested cormorants live for sixyears but 19-year-old birds have been documentedin the wild. When away from the roost,they are usually silent, but they may makehoarse, grunting alarm notes at roost sites.They are expert divers, with webbed feet,streamlined bodies, and feathers that hold waterand reduce buoyancy. They are typically believedto dive to depths of eight to 20 feet. After feeding,cormorants characteristically dry their feathersby perching with their wings outstretched.LEE KARNEY<strong>Cormorant</strong>s dry their feathers by perching with their wings outspread.

9HabitatDuring the breeding season double-crestedcormorants inhabit lakes, ponds, slow-movingrivers, lagoons, estuaries and open coastlines.They need suitable nesting sites with feedingareas nearby. <strong>Cormorant</strong>s may nest in trees oron the ground, on steep cliffs, or rocky or sandyislands. They may also use artificial sites suchas bridges, wrecks, abandoned docks or towers.Nesting trees and structures are usually locatedin or near the water on islands, in swamps, oralong tree-lined lakes. <strong>Cormorant</strong>s chooselive evergreen or deciduous trees for nesting,though the trees often die within three to tenyears because of the significant accumulationof guano deposited on them. They prefer tonest in trees when available, rather than nestingon the ground.Outside of the breeding season, cormorantsuse a variety of habitats including marineislands and coastal bays in addition to thosehabitats used during the breeding season. <strong>Cormorant</strong>sneed places with nighttime roosts anddaytime resting or loafing areas during all seasons.They roost on sandbars, rocky shoals, cliffsand offshore rocks, utility poles, fishing piers,high-tension wires, channel markers, pilings,and trees near their fishing grounds.Breeding and Nesting Behavior<strong>Cormorant</strong>s are monogamous and breed incolonies ranging from several pairs to a fewthousand pairs. Double-crested cormorants<strong>Cormorant</strong>s nest in colonies ranging from several pairs to thousands of pairs.have some site fidelity, meaning they returnto the same site to breed year after year. Youngcormorants often return to colony sites wherethey hatched or to nearby areas to breed. Beginningin April, the pair begin construction of anelevated platform nest composed of twigs,branches, and other plant materials. Thesenests often reach a height of 12–20 inches andmay be re-used in subsequent years.Like other colonial-nesting birds such asgreat blue herons (Ardea herodias), cattle egrets(Bubulcus ibis), great egrets (Ardea alba), blackcrownednight herons (Nycticorax nycticorax),gulls (Larus spp.), and terns (Sterna spp.), cormorantsprefer islands with sparse vegetation.They usually breed beginning at age three,laying two to seven (typically three or four)light blue or bluish-white eggs in mid- to lateApril. Both adults begin incubating the eggssoon after the female lays the first one, and eachJEREMY T. H. COLEMAN

10egg hatches after about 25 days. Because incubationbegins right away, the first and last nestlingmay hatch a week or more apart. When thisoccurs, the youngest birds typically do not survive,as the begging activities of the older, largermore vocal nestlings receive more attentionfrom the adult birds. On average, each nest producestwo young. The chicks usually can fly bythe time they are six weeks old. They accompanyadults to feed at seven weeks and are independentwhen they are about ten weeks old.<strong>Cormorant</strong>s lay two to seven eggs in a nest built of twigs, branches,and other plant material.JEREMY T. H. COLEMANJEREMY T. H. COLEMANDouble-crested cormorant chicks wait in the nest for their next meal. These young will become independent when they are ten weeks old.

11Migratory routes of all birds marked in May 2004and transmitting through January 2005100 0 100 200 300 miles<strong>Cormorant</strong> colonyWest Crossover IslandFour Brothers IslandFour Brothers IslandFour Brothers IslandLittle Galloo IslandBuffalo HarborBuffalo HarborOneida LakeOneida LakeOneida LakeOneida LakeOneida LakeOneida LakeOneida LakeTransmitting bird03-23-05 49512g.txt03-07-05 48838g.txt09-12-05 48862g.txt06-21-05 48861g.txt06-27-05 48850g.txt05-22-05 48832g.txt03-02-05 48831g.txt09-11-05 49514g.txt07-24-05 48847g.txt02-12-05 48845g.txt01-21-05 48841g.txt05-09-05 48836g.txt02-19-05 48829g.txt05-02-05 48833g.txtADAPTED FROM MAP BY BRIAN S. DORR / USDA / WS / NATIONAL WILDLIFE RESEARCH CENTERRoutes chosen by double-crested cormorants equipped with satellite-transmitting radio collars while on nesting grounds in May, 2004MigrationDouble-crested cormorants of the Atlanticcoast and interior populations are seasonalmigrants. They leave the northeast in September,migrating south along coastlines and rivervalleys. The two primary migration routes aredown the Atlantic coast and through theMississippi and Missouri Valleys to the GulfCoast. <strong>Cormorant</strong>s return to their breedinggrounds in late March or April.A cormorant affixed with a radio transmitter allows scientists tolearn more about the migratory routes of these birds.JEREMY T. H. COLEMAN

12Food Habits and FeedingDouble-crested cormorants feed almost exclusivelyon fish, primarily small bottomdwellingor schooling “forage” fish. They areadaptable, opportunistic feeders that prey onmany species of small fish (less than sixinches), usually feeding on those that are mostabundant and easiest to catch. This includesfish such as alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus), gizzardshad (Dorosoma cepedianum), yellow perch(Perca flavescens), sculpins (Cottus spp.) andsticklebacks (Pungitius pungitius). Because a cormorant’sability to catch a particular species offish depends on a number of factors (distribution,relative abundance, behavior, habitat), thecomposition of a cormorant’s diet can varyquite a bit from site to site and throughout theyear, and can reflect the number and types offish present in a given area at a given time.<strong>Cormorant</strong>s feed on a variety of fish species.CAL VORNBERGER WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHYTypically, cormorants feed during the day inshallow water (less than 25 feet) within a fewmiles of the shore and the breeding colony. Tocapture food cormorants dive below the surfaceand pursue prey underwater. Dives may lastfrom 20–25 seconds or more and between divesthe birds sometimes swim with their heads submerged,searching for prey. They grasp theirprey in their bills and sometimes swallow fishunderwater. <strong>Cormorant</strong>s swallow large fish orthose that are difficult to handle, such as eelsor spiny fish, at the surface. At times, they maythrow their prey into the air, catch it, and swallowit head first. <strong>Cormorant</strong>s typically forageindividually but may also gather into feedingflocks of tens to hundreds of birds, especiallywhen preying on small schooling fish.Adult cormorants feed regurgitated food totheir nestlings. For very young chicks, an adultwill arch its neck, take the head of the chickinto its mouth, and regurgitate a semi-liquidfood. Older nestlings will thrust their headsinto the adult’s throat and remove whole fishregurgitated into the neck pouchOverall, double-crested cormorants are notmajor consumers of commercial and sport fishspecies. However, exceptions have been documentedat specific sites. <strong>Cormorant</strong>s often congregatewhere there are high concentrations offish such as stocking release sites, aquacultureponds, dams and other areas. In these instances,as well as in some open water situations,they can have significant local impacts.

13Concerns About<strong>Cormorant</strong>sImpacts on Recreational FisheriesThere is a long history of conflictbetween human fishery interests and cormorants.As North American cormorantpopulations expanded following a lowpoint in the 1960s and 1970s, concerns aboutfishery impacts also expanded. By the late 1990s,natural resource agencies in 27 states reportedlosses to free-ranging fish stocks. Agencies in tenstates, ranging from the southwest to the northeast,considered cormorant predation to be ofmoderate to major fishery management concern.In reviews of cormorant diet studies, scientistshave concluded that fish species of recreationalor commercial significance generallymake up only a small percentage of the cor-DERIVED FROM TABLE IN WIRES, ET. AL., CITED ON PAGE 32Reported moderate cormorantpredation concern in fisheriesReported major cormorantpredation concern in fisheriesStates reporting concerns regarding cormorant predation to sport and commercial fisheries

14These fish were collected from the stomach of adouble-crested cormorant. <strong>Cormorant</strong>s are opportunisticand feed on a variety of fish species.morant diet. <strong>Cormorant</strong>s, however, are opportunisticpredators whose diet varies considerablywith local prey availability. For example,in one study trout comprised one percent ofgreat cormorant (Phalacocrorax carbo) diet (byweight) in one English river, and 85 percent ofthe diet in another. In another study, investigatorsfound that the percent of sport and commerciallysignificant species in the diet ofdouble-crested cormorants feeding at aWyoming river varied from less than one percentto 93 percent. At Rice Island in the ColumbiaRiver, estuary salmonids, some of which arefederally listed as threatened or endangered,are the most important prey of double-crestedcormorants. However, diet studies by themselvessay more about the importance of thefish to the cormorant than about the impact ofthe cormorant on the fish.Reviewers considering the effect of cormorantpredation on fisheries have often concludedthat they have no clearly definedimpact. Studies of fisheries impact are often inconclusive,because obtaining information canbe difficult and expensive, particularly in largeopen systems. Fisheries operateunder a wide variety ofphysical, biological and culturalconditions, so that evenwhen comprehensive informationis available it may beimpossible to separate theeffects of the various influences.Such conclusions, as can be made, aregenerally specific to the fishery in question.In recent years, several large studies offishery-cormorant interactions have been conducted.Not surprisingly the conclusions havevaried. However, studies on eastern LakeOntario, using a 20-plus year fishery database,concluded that cormorant predation was associatedwith an increase in mortality of youngsmallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieui) thatcontributed to a major decline in bass abundanceand in the quality of the bass fishery.Researchers at the Cornell University BiologicalField Station have studied the walleye(Sander vitreus) population, recreational fishery,and cormorant diet at Oneida Lake, NewYork. They determined, based on over 40 yearsof fish population data, that cormorant predationwas likely a significant source of subadultwalleye mortality that negativelyimpacted the fishery.<strong>Cormorant</strong> diets are highly variable dependingon local prey availability. Impacts on fisheriesare likely to be even more variable due tothe complex set of conditions under whichthey operate. When consideringthe potential impactof cormorant predation onany given fishery, it is importantto be aware thatsuch impact is likely to bespecific to that set of conditions.<strong>Information</strong> devel-JEREMY T. H. COLEMAN

15oped to date reveals that concerns about cormorantimpacts on open water fisheries arewidespread, but aquatic systems are extremelycomplex, and the impacts of any single predatorspecies are difficult to demonstrate with ahigh degree of certainty.Impacts on Aquaculture<strong>Cormorant</strong>s have also come into conflict withthe expanding aquaculture industry in thesoutheastern United States and elsewhere.Winter cormorant roosts in the southernUnited States near aquaculture ponds mayrange from hundreds of birds to tens of thousands.Depredation to catfish in particular hasbeen economically significant. Estimated lossto the catfish industry ranges from 5–25 milliondollars with estimates of $13 million inlosses in Mississippi alone. <strong>Cormorant</strong>s canaffect hatchery operations throughout theUnited States. The mere presence of cormorants,as well as wounds caused by unsuccessfulattacks, may stress hatchery fish.Stressed fish grow more slowly and are moresusceptible to disease. Fish-eating birds likecormorants also may increase the spread ofdisease and parasites.Effects on Vegetation and HabitatLike most colonial waterbirds, double-crestedcormorants can have a significant effect on vegetationat breeding and roosting sites throughnormal nesting activities. Their guano is acidicand can change soil chemistry, killing groundvegetation and irreversibly damaging nest trees.<strong>Cormorant</strong>s also destroy vegetation directly bystripping leaves and small branches from treesfor nesting material. At times, the weight of thebirds and their nests can even break branches.Loss of trees can lead to increased erosion, particularlyon sand spits and barrier beaches.In one example on Little Galloo Island inLake Ontario, all of the trees have died overGround vegetation and trees usually die shortly after cormorantsbegin nesting in an area, as pictured here on Little Galloo Islandin eastern Lake Ontariotime from a combination of defoliation andguano. Damage to vegetation can occur relativelyquickly after cormorants move into anarea. For instance, in the St. Lawrence estuarycormorants on several islands caused irreversibledamage to trees in less than three years.JEREMY T. H. COLEMAN

16Addition of cormorants as a nesting species in1982 on Young Island in Lake Champlain resultedin the loss of all but one tree by 1996.In some cases, cormorant colonies have significantlyaffected rare plants and plant communities.For example, the islands in westernLake Erie are home to rare Carolinian woodlandswith stands of Kentucky coffeetree (Gymnocladusdioicus), and large cormorant coloniesthere could threaten their continued existence.The interactions between colonial water birdsand vegetation are natural occurrences thathave taken place throughout history. However,in human-altered ecosystems where alternativehabitat is limited or unavailable, cormorantscan affect the persistence of vegetation communitiesand other wildlife species that rely onhabitat provided by these communities.Impacts on Other Bird Species<strong>Cormorant</strong>s tend to be attracted to nesting sitesof other colonial water birds. Occupying similarhabitat may affect other colonial water-birdspecies such as gulls, terns, egrets, herons,black-crowned night herons, as well as somewaterfowl, by directly competing for nestingsites or by altering nesting habitat. For example,cormorant guano deposited under nesttrees can kill understory vegetation important<strong>Cormorant</strong>s may alter nesting habitat for other bird species, suchas the black-crowned night heron.for nesting black-crowned night herons. AtWest Sister Island National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge inLake Erie, which supports the largest heroncolonies in the Great Lakes, great blue heronnumbers have declined annually since thedouble-crested cormorant arrived in 1992, presumablydue to a combination of nest site competition,loss of nesting sites, and an increase inhuman activity.On Oneida Lake, New York, double-crestedcormorants, along with gulls, are thought toGARY KRAMER

18Non-LethalManagement OptionsHarassmentHarassment, or scare tactics appliedin an integrated and consistent fashion,can discourage cormorants fromusing specific sites. Birds can be hazedat fish hatcheries and aquaculture facilities,as well as roosting and nesting sites on largerponds, lakes and the marine environment. Devicesthat make noise including pyrotechnicssuch as shell crackers, screamers, whistling orPropane canons and other noise-making devices are used to discourage cormorants from usingspecific areas.exploding projectiles, bird bangers, propanecannons, and live ammunition have beentried, with varying success. Live ammunitionis often the least expensive and most readilyavailable form of pyrotechnics, however othermethods may be more effective and extraprecaution should be taken to avoid injuringor killing cormorants and other protectedspecies. Hand-held lasers have been used successfullyto disperse roosting cormorants andare most effective in lowlight conditions, such asat night roosts. In addition,lasers are silent andcan be used to move cormorantswithout disturbingother non-targetspecies.The regular presenceof humans may frightencormorants fromsmaller aquaculture orhatchery facilities aswell as from roostingsites and potentialcolonies. EncouragingCOURTESY OF USDA, WILDLIFE SERVICES

19RICHARD CHIPMANUsing a variety of methods in combination, such as mylar tape (above), propane canons (opposite), human effigies, and scare eyeballoons can increase the effectiveness of harassment efforts.visitors and frequent human activity nearvaluable stocks at hatcheries and aquaculturefacilities also may help to reduce depredationon fish stocks.Visual harassment techniques like scarecrows,human effigies, and balloons have alsobeen tried with varying degrees of success.However, stringing mylar tape between stakesnear roosting and loafing sites has proveneffective in reducing cormorant use of theseareas on Oneida Lake in New York. In addition,chasing cormorants with boats has been usedsuccessfully to disperse roosts and flocks fromponds and larger bodies of water. <strong>Cormorant</strong>slearn quickly and these methods often do notdeter the birds for long. For harassment to beeffective, a variety of techniques should beused in combination, and the location andcombination of devices should be changed frequentlyfor best results.

20Habitat ModificationNetting and grid wires can prevent or detercormorants from preying on fish in hatcheryor aquaculture ponds. Nets provide a physicalbarrier and are effective as long as the edgesof the nets extend to the ground surroundingthe pond. If nets do not extend to the ground,cormorants may learn to walk into the waterand around the netting. Although netting canbe effective, the cost may be prohibitive forlarge ponds. In some instances, the levies betweenponds are too narrow to hold net supportstructures, and netting may interfere withmachinery needed for daily operations.Overhead wire systems work by making itdifficult for cormorants to land on, and takeoff from, ponds. Although these systems areeffective at preventing large flocks fromlanding, individual birds often learn to flybetween the lines, or land on levies and walkinto the pond despite the wires. However,grid wires may reduce access to people aswell, and present hazards to non-targetspecies like osprey (Pandion haliaetus) orswallows (Hirundinidae), as well as bald eagles(Haliaeetus leucocephalus). Floating ropes,sometimes called bird balls, are a less expensiveand less labor-intensive alternative towire systems. Floating ropes can be strungparallel to each other and 50–55 feet apart.The success of both wire systems and floatingropes depends on the availability of alternativeforaging areas nearby. Birds that are ableto find other food sources easily are morelikely to be deterred.Wire grid systems can also protect nestingcolonies of other waterbirds. Along with gulls,cormorants can out-compete common ternsfor favored nesting islands. Grid wires suspendedabove tern nesting colonies can enhancetern nesting success and productivityby discouraging larger birds from nesting. Thismethod effectively reserves nesting space forcommon terns until they are able to establishand defend a colony.Fisheries ManagementSite-specific impacts on fisheries often occurwhen large concentrations of easily accessiblefish are present. Fish are particularly vulnerablewhen large numbers of hatchery-raised lake fishare released at once, or when natural movements,like salmon smolt runs, or fish spawningbehavior may concentrate fish in small areas.Fish harvest methods that congregate fish inenclosed areas that cormorants can access alsoleave fish vulnerable. Releasing fish at night sothey have time to disperse before cormorantsbegin feeding in the morning can reduce predation.In lakes, releasing fish in deep water ratherthan from the shore can reduce predation. Instreams, fish can be stocked early in the seasonbefore cormorants return from their winteringgrounds. Harassment conducted in coordinationwith stocking may also relieve pressure onrecently stocked fish.

21Lethal ManagementOptionsNest Destructionvariety of methods can be used toreduce or stabilize cormorant populations,or to deter them from taking upresidence in new areas. Any techniquethat involves egg or nest destruction or removalof cormorants will require federal and in manyareas state permits may also be required. Nestsor nesting trees can be removed or physicallybroken up with the hope that adult birds willeither leave the area, or fail to rebuild and renestsuccessfully that season. This method maybe useful for discouraging cormorants fromnesting in new areas, especially if nests are destroyedearly on. It requires more effort in alreadyestablished colonies. Nest destruction isrelatively labor intensive, although can be practicalon smaller colony sites. In order to be effective,control must be repeated throughout thenesting season and likely on an annual basis.Nest removal may shift cormorants to other locationswhere they may cause other conflicts.Egg oiling can be used to prevent or reducepopulation growth and may be useful for eliminatingcolonies at specific location, especially ifcombined with other harassment or populationreduction methods. Spraying eggs with foodgradecorn oil prevents the exchange of gassesthrough the shell, causing asphyxiation. Thebenefit of egg oiling over destroying eggs is thatcormorants will continue to incubate the eggsManagers discourage nesting and encourage cormorants to leaveWantry Island in Oneida Lake, New York by removing their nests.Nest removal is a labor-intensive management activity.JEREMY T. H. COLEMAN

22and are less likely to attempt to re-nest. Managementstrategies that include egg oiling arebest suited to situations where cormorant presencecan be tolerated, and rapid populationreduction is not the goal. Because cormorantsoften re-nest, some reproduction may stilloccur if persistent effort is not applied. In somestates, a pesticide applicators license may berequired for oiling eggs.ShootingWhen a rapid reduction in cormorant numbersis required, shooting adult cormorants isan approach that is more effective for theimmediate reduction of populations thandestroying eggs or nests. Shooting can bemost effective on breeding colonies, althoughopen water shooting and removal at roostscan also be used to protect specific sites.Shooting adults also helps to reduce cormorantpopulations through harassmentof the remaining birds. Special care is necessaryto prevent killing of non-target species.Shooting can be combined with pyrotechnicsto enhance the effectiveness of non-lethalcontrol options.KRISTI L. SULLIVANA back-pack sprayer can be used to spray eggs with food grade corn oil, preventing them from hatching.

23Regulation and ManagementAuthority for <strong>Cormorant</strong>sThe United States Fish and<strong>Wildlife</strong> ServiceThe United States Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong>Service (usfws) has the primary responsibilityand authority for managingmigratory bird populations in theUnited States. This authority was establishedby the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, atreaty between the United States and GreatBritain (on behalf of Canada) established to:1. ensure the conservation and management ofmigratory birds internationally;2. sustain healthy migratory bird populationsfor consumptive and non-consumptive uses;and3. restore declining populations of migratorybirds.In 1972, the U.S. Convention with Mexicowas amended and the double-crested cormorantwas added to the list of Migratory Birds andgiven protection in the United States under theMigratory Bird Treaty Act. Under this protection,cormorants cannot be captured or shot,and their nests and eggs cannot be disturbedunless a permit is first obtained from usfws.Depredation permits to take cormorants havebeen issued by usfws since 1986 and may allowfor the taking of eggs, adults and young, oractive nests.USDA APHIS <strong>Wildlife</strong> ServicesAlthough the usfws has primary responsibilityfor managing cormorants, the usfwsdoes not conduct on-the-ground managementactivities when cormorants cause damage.The United States Department of AgricultureAnimal and Plant Health Inspection Service<strong>Wildlife</strong> Services (usda aphis ws) is one of theagencies involved with on-the-ground management.Their job is to help states, organizations,and individuals resolve conflicts betweenpeople and wildlife on public and private landsby collecting information, documentingdamage, and recommending or implementingwildlife damage management options.In March 1998, usfws issued an AquacultureDepredation Order, allowing people engagedin commercial aquaculture to shootcormorants without a federal permit at freshwateraquaculture facilities or state-operatedhatcheries in Minnesota and 12 southeastern

24states. The Depredation Order allowed shootingof cormorants during daylight hourswhen necessary to protect aquaculture/hatcherystock, if these actions were taken in conjunctionwith a non-lethal harassmentprogram approved by usda aphis ws.State <strong>Wildlife</strong> Management AgenciesAlthough usfws has the primary responsibilityfor managing cormorants, state wildlifemanagement agencies are also actively involvedin management of double-crestedcormorants. In many states, double-crestedcormorants are protected by state migratorybird legislation in addition to the MigratoryBird Treaty Act. <strong>Cormorant</strong> control programsare being implemented in states where cormorantsare affecting fish populations, vegetationand other colonial water birds. In NewYork and Vermont, for instance, programs areunderway to prevent the spread of cormorantsto other nesting islands in Lake Ontario,Oneida Lake, and Lake Champlain. Until recently,a federal permit issued by the usfwswas required before any state agency couldimplement a control program. As populationsof cormorants in many states increased, theexisting permit requirements left little flexibilityfor states to efficiently deal with conflictson a local level.JEREMY T. H. COLEMANThe double-crested cormorant is protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

25New Strategies for Managing<strong>Cormorant</strong> DamageIn 1999, the usfws with usda aphis wsas a cooperator, recognizing the need torespond to new challenges facing resourcemanagers, began developing anEnvironmental Impact Statement (eis) ondouble-crested cormorant management“to address impacts caused by populationand range expansion of the double-crestedcormorant in the . . . United States.” This document,approved in 2003, was developed toaddress growing concerns from the publicand natural resource management professionalsabout the effects of double-crestedcormorants on local fish populations, otherbird populations (including threatened andendangered species), vegetation and habitat,private property, and economic opportunities.The goal of the eis was to develop managementoptions to reduce conflicts withdouble-crested cormorants and enhance theflexibility of land management agencies todeal with problems on a more local level,while ensuring the long-term sustainabilityof cormorant populations.Increased Local <strong>Control</strong>The formal rule change includes several provisionsfor managing cormorant conflictson a local scale. The plan includes a newPublic Resource Depredation Order, whichallows state fish and wildlife agencies, federally-recognizedtribes, and usda aphis wsto use lethal control to manage doublecrestedcormorants to address conflicts in 24states. The states include Alabama, Arkansas,Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa,Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan,Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, New York,North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, SouthCarolina, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, WestVirginia, and Wisconsin.According to the new Depredation Order,lethal control, including shooting, egg oilingor destruction, and nest destruction, can becarried out to protect public resources includingfish, wildlife, plants and other wildspecies on public lands and waters. Withappropriate landowner permission, controlactivities can also take place on private landswhere double-crested cormorants that arecausing harm to public resources occur.

26Agencies are still encouraged to use nonlethaltechniques when appropriate, and responsibleagencies must conduct a baselinesurvey of colonial waterbird populations inthe area, followed by monitoring the effectivenessof the management program eachyear control measures are implemented.<strong>Control</strong> aroundAquaculture FacilitiesThe eis also allowed for increased control ofconflicts at aquaculture facilities. Under thenew rule, private and state aquaculture facilitiesin Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia,Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi,North Carolina, Oklahoma, SouthCarolina, Tennessee and Texas can shootcormorants without a federal permit as theyhave been able to since 1998. However, theAquaculture Depredation Order has beenexpanded to also allow lethal control ofcormorants at winter roost sites (October toApril) in those 13 states. In all other statesusda aphis ws may still recommend thatpermits be issued and the usfws may issuepermits to take birds, eggs or active nests.Other Management OptionsIn addition to these new features, federalregulations still allows permits to be issuedby usfws to private landowners if there issignificant economic damage to privatelystocked fish on a privately owned waterbody that maximizes fishing opportunitiesfor patrons, either for a fee or for recreation.As before, the usfws can issue permits ifcormorants are causing significant propertydamage to physical structures or vegetationon either public or private land or water, orif there is significant human health andsafety risk (e.g., airports, water quality).Adaptive ManagementThe goals of the current management rulesand depredation order are to reduce conflictswith double-crested cormorants through localizeddamage management while maintainingviable populations of double-crestedcormorants. To ensure that these goals arebeing met, the usfws is encouraging agenciesto use adaptive management to evaluatethe effects of control measures on cormorantpopulations and the extent to whichcontrol measures are alleviating damage. Asnew information is gained, future managementactivities can be modified, or adapted,as necessary.

27SummaryDouble-crested cormorantmanagement occurs in a complexbiological, ecological, and socioeconomicenvironment. Althoughcormorants can cause a variety of resourcedamages, the actualoccurrence, and relativesignificance, ofimpacts should bedetermined on a localizedbasis and science-based management strategies planned andimplemented accordingly. Continued evaluationof the impacts of management actionson both cormorant populations and theresources being protected will contributeto our understandingof how best tomanage and conservethis remarkablyadaptable andabundant bird.JEREMY T. H. COLEMAN<strong>Cormorant</strong>s use a variety of roost sites including channel markers,sandbars, rocky shoals, cliffs and offshore rocks, utility poles,fishing piers, high-tension wires, pilings, and trees.

28Additional ReadingsRICHARD CHIPMANAdams, C., M. Richmond, L. Rudstam, andJ. Forney. 1999. Diet of Double-crested<strong>Cormorant</strong>s in a New York Lake with aLong-Term Study of Walleye and YellowPerch Populations. Cooperative Fish and<strong>Wildlife</strong> Research Unit, Cornell University,Ithaca, New York, and Cornell BiologicalField Station, Bridgeport, New York.Barras, S.C., and K. Godwin. 2005. <strong>Control</strong>lingbird predation at aquaculture facilities:Frightening techniques. Southern RegionalAquaculture Center Publication No. 401.Bedard, J., A. Nadeau, and M. Lepage. 1995.Double-crested cormorant culling in theSt. Lawrence River Estuary. ColonialWaterbirds 18 (Spec. Pub. 1):78–85.As new information about cormorants is gained, managementactivities can be adapted as necessary.Belyea, G.Y., S.L. Maruca, J.S. Diana, P.J.Schneeberger, S.J. Scott, R.D. Clark, Jr., J.P.Ludwig, and C.L. Summer. 1999. Impactof double-crested cormorant predation on

29the Yellow Perch population of the LesCheneaux Islands of Michigan. pp. 47–59In Symposium on Double-crested <strong>Cormorant</strong>s:Population Status and Management Issues inthe Midwest (M.E. Tobin, ed.). USDA Tech.Bull. No. 1879. 164pp.Callaghan, D.A., J.S. Kirby, M.C. Bell and C.J.Spray. 1998. <strong>Cormorant</strong> Phalacrocorax carbooccupancy and impact at stillwater gamefisheries in England and Wales. Bird Study5:1–17.Chang, P.W. 1981. Newcastle disease.pp. 261–274 In CRC Handbook Series inZoonoses, Volume 2, Section B: ViralZoonoses (J.H. Steel, ed.). CRC Press, BocaRaton, FL.Coleman, J.T.H., M.E. Richmond, L.G. Rudstam,and P.M. Mattison. 2005. Foraging locationand site fidelity of the double-crestedcormorant on Oneida Lake, New York.Waterbirds 28: 498–510.Collis, K., S. Adamany, D.D. Roby, D.P. Craig,and D.E. Lyons. 2000. Avian predation onjuvenile salmonids in the lower ColumbiaRiver. Annual Report for 1998 researchto the Bonneville Power Administration,Portland, OR (http://www.efw.bpa.gov/Environment/ew/ewp/docs/reports/downstrm/d33475-2.pdf).Craven, S.R. and E. Lev 1987. Double-crestedcormorants in the Apostle Islands,Wisconsin, USA: Population trends, foodhabits and fishery depredations. ColonialWaterbirds 10:64–71.Daniel, A. 1989. Forest decline on Young Island:Impact of nesting ring-billed gulls on vegetationand soils with recommendations forwildlife management. Masters Thesis.University of Vermont, Burlington.Derby, C.E. and J.R. Lovvorn. 1997. Predationon fish by cormorants and pelicans in acold-water river: a field and modelingstudy. Canadian Journal of Fisheries andAquatic Sciences 54: 1480–93.Dieperink, C. 1995. Depredation of commercialand recreational fisheries in a Danish fjordby cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis)Shaw. Fisheries Management and Ecology2:197–207.Glahn, J.F., S.J. Werner, T. Hanson and C.R. Engle.2003. <strong>Cormorant</strong> depredation losses andtheir prevention at catfish farms: Economicconsiderations. United States Department ofAgriculture, <strong>Wildlife</strong> Services, National<strong>Wildlife</strong> Research Center. pp. 138–146 InHuman Conflicts with <strong>Wildlife</strong>: EconomicConsiderations. Proceedings of the 3rd NWRCSpecial Symposium (L. Clark, ed.).

30Jarvie, S., H. Blokpoel, and T. Chipperfield. 1999.A geographic information system to monitornest distributions of double-crestedcormorants and black-crowned nightheronsat shared colony sites near Toronto,Canada. pp. 121–129 In Symposium onDouble-crested <strong>Cormorant</strong>s: Population Statusand Management Issues in the Midwest(M.E. Tobin, ed.). usda/aphis Tech. Bull.No. 1879. 164pp.Hatch, J. J., and D.V. Weseloh. 1999. Doublecrested<strong>Cormorant</strong> (Phalacrocorax auritus).In The Birds of North America, No. 441(A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds ofNorth America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.Herbert, C. E., J. Duffe, D.V. Weseloh, E.M.Senese, and G. D. Haffner. 2005. Uniqueisland habitats may be threatened bydouble-crested cormorants. Journal of<strong>Wildlife</strong> Management 69: 68–76.Karwowski, K., J.T. Hickey, and D.A. Stilwell.1994. Food study of the Double-crested<strong>Cormorant</strong>, Little Galloo Island, LakeOntario, New York, 1992. U.S. Fish and<strong>Wildlife</strong> Service, Cortland, NY.Lantry, B.F., T.H. Eckert, and C.O. Schneider.1999. The relationship between the abundanceof smallmouth bass and doublecrestedcormorants in the eastern basin ofLake Ontario. New York State Departmentof Environmental Conservation SpecialReport, Cape Vincent, New York.Lemmon, C.R., G. Bugbee, and G.R. Stephens.1994. Tree damage by nesting doublecrestedcormorants in Connecticut. TheConnecticut Warbler 14:27–30Lewis, H.F. 1929. The natural history of thedouble-crested cormorant (Phalacrocoraxauritus auritus (Lesson). Ph.D. Thesis,Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.Ludwig, J.P., C.N. Hull, M.E. Ludwig, and H.J.Auman. 1989. Food habits and feedingecology of nesting double-crestedcormorants in the upper Great Lakes,1986–1989. Jack Pine Warbler 67: 115–126.Mattison, P.M. 2006. Quantifying disturbancefactors and effects in common terns (Sternahirundo) using visual, audio, and reproductivedata. M.S. Thesis, Cornell University,Ithaca, New York.Molina, K.C. 2004. Breeding larids of the SaltonSea: Trends in population size and colonysite occupation. Studies in Avian Biology27:92–99.

31McCullough, R.D., and D.W. Einhouse. 1998.Lake Ontario —Eastern Basin Creel Survey,1998. New York State Department ofEnvironmental Conservation SpecialReport, Watertown, New York.Mendall, H.L. 1936. The home-life and economicstatus of the double-crestedcormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus auritus L).The Maine Bulletin 39:1–159.Mitchell, R.M. 1977. Breeding biology of thedouble-crested cormorant on a Utah lake.The Great Basin Naturalist 37:1–23.Neuman, J., D.L. Pearl, P.J. Ewins, R. Black, D.V.Weseloh, M. Pike, and K. Karwowski. 1997.Spatial and temporal variation in the diet ofdouble-crested cormorants (Phalacrocoraxauritus) breeding on the lower Great Lakesin the early 1990s. Canadian Journal ofFisheries and Aquatic Sciences 54:1569–1584.Palmer, R.S. 1962. Handbook of North AmericanBirds. Volume 1. New Haven and London.Yale University Press.Price, I.M., and D.V. Weseloh. 1986. Increasednumbers and productivity of doublecrestedcormorants, Phalacrocorax auritus,on Lake Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist100:474–482.Rudstam, L.G., A.J. VanDeValk, C.M. Adams,J.T.H. Coleman, J.L. Forney, and M.E.Richmond. 2004. Double-crestedcormorant predation and the populationdynamics of walleye and yellow perch inOneida Lake. Ecological Applications14:149–163.Russell, I., A. Cook, D. Kinsman, M. Ives,N. Lower, and S. Ives. 2003. Stomachcontents analysis of cormorants at somedifferent fishery types in England andWales. Vogelwelt 124:255–259.Sheppard, Y. 1994. <strong>Cormorant</strong>s and pelicans:Scapegoats for a fishing industry gone bad.Birds of the Wild 4:30–34.Trapp, J.L., T.J. Dwyer, J.J. Doggett, and J.G.Nickum. 1995. Management responsibilitiesand policies for cormorants: UnitedStates Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service. Waterbirds18 (Spec. Pub. 1):266–230.VanDeValk, A.J., C.M. Adams, L.G. Rudstam,J.L. Forney, T.E. Brooking, M.H. Gerkin,B.P. Young, and J.T. Hooper. 2002.Comparison of angler and cormorantharvest of walleye and yellow perch inOneida Lake, New York. Transactions of theAmerican Fisheries Society 131:27–39

32Weseloh, D.V., and P.J. Ewins. 1994.Characteristics of a rapidly increasingcolony of double-crested cormorants(Phalacrocorax auritus) in Lake Ontario:Population size, reproductive parametersand band recoveries. Journal of Great LakesResearch 20:443–456.Wires, L.R., F.J. Cuthbert, D.R. Trexel, andA.R. Joshi. 2001. Status of the doublecrestedcormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus)in North America. Final Report to UnitedStates Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service. Universityof Minnesota, St. Paul, Minn.Weseloh, D.V., and B. Collier. 1995. The rise ofthe double-crested cormorant on the GreatLakes: Winning the war against contaminants.Great Lakes Fact Sheet. Canadian<strong>Wildlife</strong> Service, Environment Canada andLong Point Observatory.

Unlike other water birds, the double-crested cormorant is neither well-known nor widely recognized by the public.STAN TEKIELA

The Double-Crested<strong>Cormorant</strong>Issues and ManagementIn the eastern United States, the doublecrestedcormorant has generated a tremendousamount of interest and controversy in recentyears. <strong>Cormorant</strong> populations have increaseddramatically since the 1970s, and conflicts withcommercial and sport fisheries, competition withother waterbirds for nesting space, and damageto property occur in several states.The information presented in this guide is intendedto help anglers, fish hatchery operators, fisheriesand wildlife professionals, lake association members,and other interested stakeholders find theinformation needed to understand both the complexityof issues involved, and the managementoptions available for reducing cormorant problems.Although conflicts with cormorants occur in otherareas of the country, this bulletin focuses on populationsof the interior United States and the easternAtlantic coast.This publication is the result of collaboration byCornell University Cooperative Extension, the U.S.Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service, the USDA APHIS <strong>Wildlife</strong>Services, the USGS New York Cooperative <strong>Wildlife</strong>Research Unit, and the New York State Departmentof Environmental Conservation. Copies of thisbooklet are available from the Department of NaturalResources, Fernow Hall, Cornell University,Ithaca, New York 14853.Kristi L. Sullivan, Paul D. Curtis, Richard B.Chipman, and Russell D. McCulloughDepartment of Natural ResourcesFernow HallCornell UniversityIthaca, NY 14853