ISFNR Newsletter No. 6 February 2012 (in pdf-format)

ISFNR Newsletter No. 6 February 2012 (in pdf-format)

ISFNR Newsletter No. 6 February 2012 (in pdf-format)

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

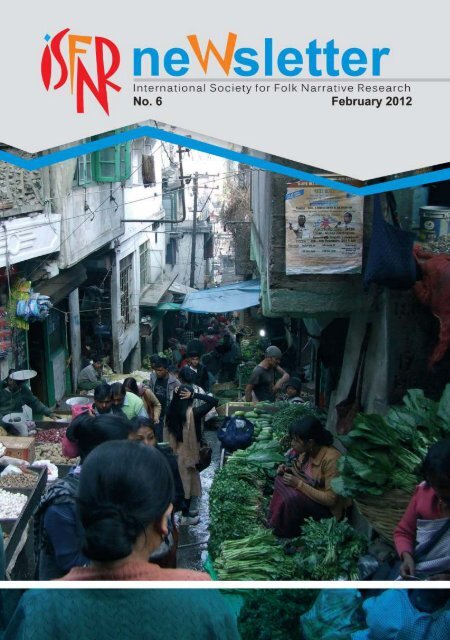

2<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong>Front cover: old market <strong>in</strong> Shillong.Photo by Ergo-Hart VästrikBack cover: boys <strong>in</strong> Nartiang, the villagewith the biggest cluster ofmegaliths <strong>in</strong> the Ja<strong>in</strong>tia Hills, Meghalaya.Photo by Ülo Valk<strong>ISFNR</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong> is published by theInternational Society for Folk NarrativeResearch.InternationalSocietyfor FolkISSN 1736-3594 NarrativeResearchEditor:Ülo Valk (ulo.valk@ut.ee)Language editor: Daniel E. AllenDesign and layout: Marat ViiresEditorial Office: InternationalSociety<strong>ISFNR</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong>for FolkUniversity of TartuNarrativeDepartment of Estonian Research and ComparativeFolkloreÜlikooli 16-20851003 TartuEstonia<strong>ISFNR</strong> on the Internet:http://www.isfnr.orgInternationalSocietyfor FolkNarrativeResearchThis publication was supported by the EuropeanUnion through the European RegionalDevelopment Fund.ContentsEditorialby Ülo Valk.................................................................................................... 3The <strong>ISFNR</strong> Interim Conference “Tell<strong>in</strong>g Identities:Individuals and Communities <strong>in</strong> Folk Narratives” <strong>in</strong>Shillong, <strong>No</strong>rth-East India, <strong>February</strong> 22–25, 2011:Presidential Address at the Open<strong>in</strong>g of the <strong>ISFNR</strong> Interim Conferenceby Ulrich Marzolph ....................................................................................... 4The <strong>ISFNR</strong> Interim Conference 2011 <strong>in</strong> Retrospectby Pihla Siim .............................................................................................. 12<strong>ISFNR</strong> Review: Shillong Lives up to Its Reputationby Meenaxi Barkataki-Ruscheweyh .......................................................... 14An Experience from Indiaby Sarmistha De Basu ............................................................................... 17Impressions of the Local Aspect of the <strong>ISFNR</strong> Interim Conference,Shillong, 2011by Mark Bender .......................................................................................... 18Beliefs and Narratives <strong>in</strong> Shillong, Indiaby María Ines Palléiro ............................................................................... 20CALL FOR PAPERS: 16 th Congress of the <strong>ISFNR</strong> <strong>in</strong> Vilnius,Lithuania, <strong>in</strong> 2013 ..................................................................................... 23CALL FOR PAPERS: Belief Narrative Network Symposium “Boundaries ofBelief Narratives” at the 16 th Congress of the <strong>ISFNR</strong> <strong>in</strong> Vilnius, Lithuania,<strong>in</strong> 2013 ....................................................................................................... 25Life-Tradition: Contribution to the Concept of Life-Worldby Giedrė Šmitienė .................................................................................... 27The Problem of Belief Narratives: A Very Short Introductionby Willem de Blécourt ............................................................................... 36Report of the <strong>ISFNR</strong> Committee on Charms, Charmers and Charm<strong>in</strong>g,2011: The Year of Moscow and Incantatioby Jonathan Roper .................................................................................... 38Collect : Protect : Connect – The World Oral Literature Projectby Claire Wheeler, Eleanor Wilk<strong>in</strong>son and Mark Tur<strong>in</strong> .............................. 39Identity & Diversity: The Future of Indigenous Culture <strong>in</strong> a GlobalisedWorld (Conference at the Central University of Jharkhand,<strong>February</strong> 1–2, 2011)by Faguna Barmahalia, Rupashree Hazowary and Ülo Valk ...................... 43Symposium on F<strong>in</strong>no-Ugric Folkloreby Merili Metsvahi ..................................................................................... 45New <strong>ISFNR</strong> Members Summer 2010 – December 2011 ............................. 47Traditional and Literary Epics of the World:An International Symposium Reviewby Ambrož Kvartič ...................................................................................... 48

<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong> 3Dear Friends <strong>in</strong> Folklore Research,the sixth issue of the newsletter marksthe way of the <strong>ISFNR</strong> from the <strong>in</strong>terimconference, which was held <strong>in</strong> Shillong,India on <strong>February</strong> 22–25, 2011,to the 16 th congress, to convene <strong>in</strong> Vilnius,Lithuania on June 25–30, 2013.The ma<strong>in</strong> goal of the <strong>ISFNR</strong> is to developscholarly work on folk narrativesand to stimulate contacts among researchers,although its regular forums,held on different cont<strong>in</strong>ents and with<strong>in</strong>different cultural contexts, always offersome extra values to the benefits ofacademic discussions. Participants <strong>in</strong>the meet <strong>in</strong> Shillong experienced thefamous ethnic and cultural diversityof <strong>No</strong>rth-East India <strong>in</strong> many aspects:<strong>in</strong> the variety of papers, dedicated tothe local traditions; the cultural eventsof the conference program; and thedaily life <strong>in</strong> the city and <strong>in</strong> the stateof Meghalaya, which is the home ofseveral <strong>in</strong>digenous peoples. In the<strong>in</strong>augural lecture of the <strong>in</strong>terim conference,published <strong>in</strong> this newsletter,Ulrich Marzolph, the president of the<strong>ISFNR</strong>, discusses cultural hybridityand exchange as universal phenomena,characteristic of diverse formsof human expression. The world of<strong>No</strong>rth-East Indian cultures, touched byH<strong>in</strong>duism, by Western and Christian<strong>in</strong>fluences and yet unique as a constellationof local <strong>in</strong>digenous traditions,offers many conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g examples tohis arguments about the weakness ofearly folklore scholarship that tendedto overwrite the narrative cultures ofthe world accord<strong>in</strong>g to familiar patternsof European standards.In order to see the <strong>ISFNR</strong> <strong>in</strong>terimconference <strong>in</strong> Shillong from a varietyof perspectives, I asked fiveparticipants from different countriesto reflect upon their memories andimpressions. Sometimes it is difficultto f<strong>in</strong>d people who will agree to writeconference reports and who laterfulfil these enforced promises – however,this did not happen this time.The ease of receiv<strong>in</strong>g the articlesfrom Sarmistha De Basu, MeenaxiBarkataki-Ruscheweyh, Mark Bender,María Inés Palleiro and Pihla Siimrem<strong>in</strong>ds me of the easy, happy andfriendly atmosphere of this smoothlyrun event. Professor Desmond L.Kharmawphlang, his team and the<strong>No</strong>rth-Eastern Hill University (NEHU)deserve our great gratitude for theirremarkable work, mak<strong>in</strong>g the conferencepossible and mark<strong>in</strong>g Shillongon the mental map of <strong>in</strong>ternationalscholarship as a vibrant centre of folkloristics.The folklore program of theDepartment of Cultural and CreativeStudies, NEHU, def<strong>in</strong>itely has a greatmission <strong>in</strong> service of the ethnic communitiesof <strong>No</strong>rth-Eastern India andacademic folkloristics, which is both awell-established and rapidly develop<strong>in</strong>gdiscipl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> this part of the world.While the memories of <strong>No</strong>rth-EasternIndia are still fresh among the conferenceparticipants, the <strong>ISFNR</strong> is look<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>to its near future to hold its nextregular congress <strong>in</strong> <strong>No</strong>rth-EasternEurope, <strong>in</strong> Vilnius, the capital city ofLithuania. Please f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> this issue thecalls for papers for the 16 th congressof the <strong>ISFNR</strong>, Folk Narrative <strong>in</strong> theModern World: Unity and Diversity,and symposium of the Belief NarrativeNetwork, Boundaries of BeliefNarratives, to be held at the samecongress <strong>in</strong> Vilnius on June 25–30,2013. Lithuania is known not only foramber, basketball and the mystic artand music of Mikalojus K. Čiurlionis,but also for strong traditions <strong>in</strong> folkloreresearch, represented by famousscholars, such as Jonas Balys,<strong>No</strong>rbertas Vėlius, Marija Gimbutas,Algirdas J. Greimas and many others.As an example of current Lithuanianscholarship we can read the articleby Giedrė Šmitienė from the Instituteof Lithuanian Literature and Folklore,one of the lead<strong>in</strong>g centres of folkloreresearch <strong>in</strong> the Baltic states and<strong>No</strong>rthern Europe and the ma<strong>in</strong> organiserof the next <strong>ISFNR</strong> congress. Rely<strong>in</strong>gon her rich fieldwork experience,Giedrė Šmitienė shows that traditioncannot be def<strong>in</strong>ed as a closed setof possessed knowledge but can beunderstood as a lived, embodied andnarrated reality. Tradition thus takes<strong>in</strong>dividual forms, appear<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> relationshipwith home as a lived place, andis <strong>in</strong> constant flow. The concept of lifetradition,<strong>in</strong>troduced by Šmitienė, canprobably also shed light on the jo<strong>in</strong>tactivities of communities and networks<strong>in</strong> creative and develop<strong>in</strong>g forms. TheBelief Narrative Network (BNN) of the<strong>ISFNR</strong>, established <strong>in</strong> 2009 at the 15 thcongress <strong>in</strong> Athens, held a succesfulconference <strong>in</strong> St. Petersburg <strong>in</strong> May2010, organised by professor AlexanderPanchenko, and a symposium,Belief Narratives and Social Realities,at the <strong>ISFNR</strong> <strong>in</strong>terim conference <strong>in</strong>Shillong <strong>in</strong> <strong>February</strong> 2011. In the currentissue we publish the address ofWillem de Blécourt, the chair of theBNN, to the conference <strong>in</strong> St. Petersburg.Unfortunately, he was unableto attend the meet<strong>in</strong>g because ofcomplications of gett<strong>in</strong>g the visa andalso the Skype l<strong>in</strong>k did not work <strong>in</strong> theend. In his short <strong>in</strong>troduction Willemde Blécourt del<strong>in</strong>eates some of theguidel<strong>in</strong>es to study<strong>in</strong>g and problematis<strong>in</strong>gbeliefs and their expressions <strong>in</strong>narratives.The productive work of the <strong>ISFNR</strong>Committee on Charms, Charm<strong>in</strong>g andCharmers is discussed <strong>in</strong> this issueby Jonathan Roper, the chair of thecommittee. Landmarks of 2011 are thesuccessful conference <strong>in</strong> Moscow andthe first issue of the journal Incantatio.Claire Wheeler, Eleanor Wilk<strong>in</strong>sonand Mark Tur<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduce the WorldOral Literature Project, which haseven wider and further-reach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ternationaldimensions. Founded <strong>in</strong>2009, the project is carried out at theUniversity of Cambridge, UK and YaleUniversity, USA and aims to documentand preserve the most endangeredcultural traditions of our planet. As the<strong>in</strong>itiative promotes fieldwork amongmarg<strong>in</strong>alised ethnic communities andsafeguards their oral traditions, the<strong>ISFNR</strong> shares the ethos of the projectand completely supports its goals.Hopefully, readers of the current

<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong> 5Nairobi, Kenya (2000), Melbourne,Australia (2001), and Santa Rosa,Argent<strong>in</strong>a (2007).We are particularly happy to meet<strong>in</strong> Meghalaya s<strong>in</strong>ce the first IndianDepartment of Folkloristics was founded<strong>in</strong> 1972 at the nearby University ofGauhati, the oldest university <strong>in</strong> theregion. The Folklore Research Departmentat Gauhati was established witha view to study the oral literature, customs,art forms and perform<strong>in</strong>g arts ofthe communities of <strong>No</strong>rth-East India.Today, its mission statement deploresa certa<strong>in</strong> cultural <strong>in</strong>stability and thedecay of traditional knowledge <strong>in</strong> theregion. Such an evaluation of the situationof folklore is all the more regrettables<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>No</strong>rth-East India pridesitself of a wealth of cultural, ethnic,and l<strong>in</strong>guistic diversity.Folklore, as we all know, is a pivotalconstituent of cultural identity; folk narrative– the ma<strong>in</strong> concern of our society– serves as the verbal expression ofthis identity at a narrative level. Thespecific characteristics of folk narrativetraditions differ widely on an <strong>in</strong>ternationalscale. Yet all folk narrativetraditions share a notion of condens<strong>in</strong>gthe highly complex worlds of their narratorsand the surround<strong>in</strong>g societies<strong>in</strong>to the nutshell of a narrative. Theextent to which these narratives correspondto the worldview, the ethicalnorms and the social circumstancesof their surround<strong>in</strong>g cultures or societieseventually def<strong>in</strong>es the degree oftheir reception and, hence, their popularity.Narratives may be lengthy andhighly artful compositions, such as thelong epics of Asian, European, or Africantradition the oral performancesof which at times takes days or evenweeks to complete. Narratives mayalso be highly codified items, such asfolktales and fairy tales, or even fairlysimple and straightforward short items,such as jokes and anecdotes. Whilepopular narratives are primarily texts,<strong>in</strong> live performance they may often gotogether with dramatic enactment orvisual representation illustrat<strong>in</strong>g thetext. Whatever they are, popular narrativesconstitute highly mean<strong>in</strong>gful itemsof verbal art, and their documentationand study is a constant challenge toour discipl<strong>in</strong>e. While popular narrativesdeserve to be preserved <strong>in</strong> publishedcollections, they should not, and certa<strong>in</strong>lynot primarily, be stored away asmuseum pieces devoid of their orig<strong>in</strong>alcontext and mean<strong>in</strong>g. Documentationis a necessary part of research, butby no means should the study of folknarrative end with the simple record<strong>in</strong>gor publication, and neither with theclassification of narratives <strong>in</strong> nationalor <strong>in</strong>ternational catalogues. In otherwords, the documentation, classificationand publication of popular narrativesare but the necessary first stepsfor their study. Popular narrativesare very much alive. They changeconstantly while adapt<strong>in</strong>g and respond<strong>in</strong>gto the exigencies of surround<strong>in</strong>gsocieties and cultures.Popular narratives are as much aliveas the people who narrate the tales.At times we may have to face the deplorabledisappearance from activetradition of age-old cherished narrativessuch as those we heard ourselvesfrom previous generations. At the sametime, new genres appear, such as therecent genres of urban legends or of <strong>in</strong>ternetlore. At any rate, a world withoutpopular narratives is simply unimag<strong>in</strong>able.Humanity has been shap<strong>in</strong>g itsexperience <strong>in</strong>to narratives s<strong>in</strong>ce timeimmemorial. The modern media haveaccelerated the lives of many <strong>in</strong>dividualsand communities, particularly <strong>in</strong> thetechnologically ‘advanced’ societies, tosuch an <strong>in</strong>credible pace that the term‘tradition’ almost appears a contradiction<strong>in</strong> terms. Meanwhile, narrativeshave not disappeared. Rather thecontrary, they document their superiorposition <strong>in</strong> human expression by adapt<strong>in</strong>gto the chang<strong>in</strong>g times, by form<strong>in</strong>gnew genres and by transform<strong>in</strong>g oldgenres to fit the new media of transmission.To quote a favourite term ofKurt Ranke, the found<strong>in</strong>g father of my<strong>in</strong>stitution, the German based Encyclopediaof Folktales and Fairy Tales, thehuman be<strong>in</strong>g is a “homo narrans”, andstorytell<strong>in</strong>g is a basic quality of humanexistence. Wherever humans live, theywill always strive to grasp their experienceand communicate their worldview<strong>in</strong> the garb of narratives.Aga<strong>in</strong>st this backdrop of our discipl<strong>in</strong>e,let me stress once more the importanceof stag<strong>in</strong>g the present <strong>ISFNR</strong>Interim Conference <strong>in</strong> Shillong. S<strong>in</strong>ceits <strong>in</strong>ception <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century,the discipl<strong>in</strong>e of folk narrative researchhas turned to India for some of theoldest narrative sources available, andcerta<strong>in</strong>ly some of the most <strong>in</strong>fluentialones on an <strong>in</strong>ternational level. TheSanskrit Pancatantra together withits numerous descendants <strong>in</strong> a multitudeof languages is an <strong>in</strong>fluentialconstituent of world literature as wellas <strong>in</strong>ternational narrative tradition. Theworld’s most renowned collection ofnarratives, the Thousand and OneNights, is heavily <strong>in</strong>debted to ancientIndian tradition. In addition, Indiantradition has produced several otherlarge compilations of narratives thatfor many centuries have exerted aconsiderable <strong>in</strong>fluence on world narrative,East and West, such as thestandard collection of Buddhist tales,the Tripitaka, Somadeva’s Kathâsaritsâgara,The “Ocean of Stories”, or theanonymous Śukasaptati, the “Tales ofthe Parrot”. Meanwhile, whatever weknow about Indian folk narrative on an<strong>in</strong>ternational level appears to pale <strong>in</strong>to<strong>in</strong>significance aga<strong>in</strong>st the truly vast“Ocean of Stories” – to borrow thetitle of Somadeva’s collection – thatwe encounter <strong>in</strong> Indian oral tradition.In particular, Indian folk narrativesare primarily known to the West byway of a small selection of publications<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational languages, yetthe wealth of liv<strong>in</strong>g oral tradition canonly be guessed at by those withoutaccess to the native languages. Thisassessment notably not only holdstrue for India, but <strong>in</strong> fact for manyof the world’s oral traditions, forknowledge of which <strong>in</strong>ternationalscholars depend on the availability ofaccessible translations. At the sametime, the <strong>in</strong>ternational knowledge ofworldwide narrative traditions has for along time also been heavily <strong>in</strong>fluenced

<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong> 7what extent does the perception of therespective folk narrative researcher<strong>in</strong>fluence the understand<strong>in</strong>g of foreigncultures? And f<strong>in</strong>ally: to whatextent does folk narrative researchact aga<strong>in</strong>st the background of a selfcentredmatrix imply<strong>in</strong>g the perceptionof foreign cultures only aga<strong>in</strong>stthe background of the researcher’sown experience?L-R: A.N. Rai, Vice-Chancellor of the <strong>No</strong>rth-Eastern Hill University, A.C. Bhagabati and JawaharlalHandoo at the dedicated session of the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (New Delhi),<strong>ISFNR</strong> <strong>in</strong>terim conference <strong>in</strong> Shillong.Photo by Ülo Valk.of economy – capital, possession andwork. Yet it is certa<strong>in</strong> that knowledge isas unevenly distributed <strong>in</strong>ternationallyas the other categories: globalisationsuggests an equality that it cannotproduce. Moreover, globalisation doesnot imply the functional equivalenceof <strong>in</strong><strong>format</strong>ion that is made globallyaccessible; rather it means the hegemonis<strong>in</strong>gof standards, ever sooften with the implicit goal of globalcommercial exploitation. In order notto turn my presentation <strong>in</strong>to an antiimperialisticpamphlet, I suggest, forthe time be<strong>in</strong>g, to leave aside the politicaland economic implications ofthese considerations, some of whichare deeply relevant for countries likeIndia. So let me return to the specificproblems of folk narrative research.The third conceptual complex to bementioned possesses particular relevancefor my discussion. While theconcept of globalisation is explicitlyconcerned with hegemonis<strong>in</strong>g, theconcepts of <strong>in</strong>tercultural and multiculturalstudies implicitly regard cultureas an entity that can clearly be def<strong>in</strong>edand demarcated, only thereby mak<strong>in</strong>gthe comparison of different entities,<strong>in</strong> this case cultures, possible.In contrast to this concept, <strong>in</strong> recentyears the related debate about thehybridity or hybridisation of cultureshas created awareness of the factthat cultures <strong>in</strong> themselves alreadyrepresent a conglomerate of smallerentities of various orig<strong>in</strong>s 2 . This concept,orig<strong>in</strong>ally borrowed from biology,questions the monolithic and clearlydemarcated character of cultures, andproposes we view cultures – <strong>in</strong> thewords of Edward Said – as “closely<strong>in</strong>terwoven; no culture is unique andpure, every culture is hybrid, heterogeneous,extremely differentiatedand unmonolithic” 3 . The concept ofhybridity thereby challenges the conceptof <strong>in</strong>tercultural studies <strong>in</strong>sofar asit proposes a focus on constituents ofcommon orig<strong>in</strong> rather than on a dialogueof differences. The concept ofcultural hybridity makes it possible – toquote Homi Bhabha – to study “differencewithout a received or decreedhierarchy” 4 . If cultures <strong>in</strong> themselvesare already complex hybrid productswhose characteristics orig<strong>in</strong>ate bothfrom different and common sources,then differences can be observedwithout the need for evaluation.These general considerations leadto various questions for comparativefolk narrative research, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g thebasic question aga<strong>in</strong>st which theoreticalbackground folk narrative researchoperates. How broad are the possibilitiesof perceiv<strong>in</strong>g foreign cultures byway of their narrative expression? ToIn discuss<strong>in</strong>g these questions, the follow<strong>in</strong>gconsiderations are based onthe evaluation of a number of textsdedicat<strong>in</strong>g themselves to the researchof “European narrative X with<strong>in</strong> thenon-European culture Y”. This questionrelates to a special category of‘displaced’ folktales <strong>in</strong> the sense of theterm proposed by <strong>No</strong>rwegian folkloristReidar Thoralf Christiansen <strong>in</strong> 1960 5 .The declared object of such <strong>in</strong>vestigationspromises to supply basic <strong>in</strong><strong>format</strong>ionabout the degree to whichcharacteristics of foreign cultures canbe perceived. In other words: Whenwe are study<strong>in</strong>g characteristics ofan alien culture that orig<strong>in</strong>ate fromour own culture are we <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong>what became of the ‘Own’? Or are wesensitive <strong>in</strong> relation to what the ‘Own’means to the ‘Alien’, and moreover,what the ‘Alien’ means to itself?The example of the European receptionof the Orient may serve to rem<strong>in</strong>dus how strongly the perception of analien cultural sphere can be determ<strong>in</strong>edby the conditions of the perceiv<strong>in</strong>gculture 6 . When, towards the end ofthe seventeenth century, the MuslimOttoman empire ceased to constitutea military threat for Christian centralEurope, the previously reign<strong>in</strong>g anxietydirected aga<strong>in</strong>st the Turks fadedaway and soon gave rise to an uncriticalenthusiasm for everyth<strong>in</strong>g Turkish,a so-called Turquoiserie that generateda popular enthusiasm for th<strong>in</strong>gs‘Oriental’. An essential constituentof this form of Orientalism – notablyboth product and producer – was theEuropean translation of the orig<strong>in</strong>allyArabic Stories of the Thousandand One Nights, <strong>in</strong> English commonlyknown as The Arabian Nights’

8<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong>Enterta<strong>in</strong>ments, <strong>in</strong> short, The ArabianNights, or shorter even, the Nights.The Nights were first <strong>in</strong>troducedto the European public by Frenchorientalist scholar Anto<strong>in</strong>e Gallandfrom 1704 onwards <strong>in</strong> a form that hasaptly been termed an “appropriation”rather than a translation 7 . Galland’stext not only furnished new narrativematerial to the French literary salons,but rather quickly <strong>in</strong> the whole of Europeevoked a tremendous <strong>in</strong>spiration<strong>in</strong> various areas of creativity, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gliterature, music, drama, pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g, andarchitecture. The cultural complexityof the Arabian Nights was unravelledby research only follow<strong>in</strong>g its popularreception and today rema<strong>in</strong>s ratherunknown to the general public. It isquite tell<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>in</strong> common apprehensiona few tales from the ArabianNights became more or less synonymousfor the collection itself. <strong>No</strong>tably,these tales prior to Galland’s translationhad never belonged to the orig<strong>in</strong>alArabic collection. Moreover, they owemuch of their particular characteristicsto the <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong>fluence of the ostensibletranslator. The most productiveof these stories <strong>in</strong> terms of worldwide<strong>in</strong>spiration is the story of Aladd<strong>in</strong> andthe Magic Lamp. While the basicstructure of that story is legitimisedas ‘authentic’ by the oral performanceof the Syrian Christian narratorHanna Diyab, the story conta<strong>in</strong>s elementsthat strongly suggest an autobiographicre-work<strong>in</strong>g by Galland.What the readers perceive thereforeas the ‘Orient’ with<strong>in</strong> the tale is littlemore than their own imag<strong>in</strong>ations andfantasies about the Orient <strong>in</strong> pseudoauthenticgarb; <strong>in</strong> other words, an Orient‘with<strong>in</strong> themselves’. This critiquesimilarly applies to wide areas of thereception of the Arabian Nights <strong>in</strong> then<strong>in</strong>eteenth century, above all for theabundantly annotated translations preparedby Edward William Lane andRichard Burton. Both correspond to a‘text <strong>in</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>d of people’ rather thanconvey<strong>in</strong>g Arabic or ‘Oriental’ reality.S<strong>in</strong>ce the days of Galland almostthree centuries have passed, andone might feel <strong>in</strong>cl<strong>in</strong>ed to th<strong>in</strong>k thatsuch forms of the perception of thecultural ‘Other’ are now relegatedto popular enterta<strong>in</strong>ment – such asthe Disney cartoon version of Aladd<strong>in</strong>that was screened <strong>in</strong> 1992 8 . Witha certa<strong>in</strong> amount of reassurance, itseems unlikely that contemporaryfolk narrative research would fall <strong>in</strong>tothe old trap. But are we really entitledto th<strong>in</strong>k so? Dutch folk narrative researcherJurjen van der Kooi recentlyfelt obliged to publish a strong pleafor “worldwide comparative studies” 9 .Justified as it is, his plea also revealsthat this author regards the ways <strong>in</strong>which the complexity of processes oftransmission are perceived by currentresearch as <strong>in</strong>sufficient. This critiquealso applies to the corpus of Europeanstudies <strong>in</strong> folk narrative research here<strong>in</strong>vestigated. It soon becomes clearthat even though there is discernibleprogress from the colonial attitude 10towards <strong>in</strong>digenous narrative traditions,a conscious effort is needed<strong>in</strong> order to discard a traditional perspective<strong>in</strong> favour of contemporaryrequirements. Let me give you a fewexamples.When the German orientalist (andesteemed translator of the ArabianNights) Enno Littmann expressesconcepts of the “truly lower German”or “authentically oriental” <strong>in</strong> his essay“Sneewittchen <strong>in</strong> Jerusalem” (1932) 11 ,we might feel entitled to evaluate hisremarks as old-fashioned and outdated.But what are we to th<strong>in</strong>k aboutthe debate that was go<strong>in</strong>g on up tothe 1970s between Richard Dorsonand his critics about the African backgroundof Afro-American narratives? 12How should we evaluate Africanistscholar Sigrid Schmidt’s remark, who<strong>in</strong> 1970, when report<strong>in</strong>g about the missionaryRobert Moffat’s experiences<strong>in</strong> 1818, evaluated the behaviour byone of his <strong>in</strong>formants as “an act ofconscious ly<strong>in</strong>g”? 13 What are we toth<strong>in</strong>k when psychologists Am<strong>in</strong>e A.Azar and Anto<strong>in</strong>e M. Sarkis <strong>in</strong> theirstudy of the “migrations of Little RedRid<strong>in</strong>g Hood <strong>in</strong> the Levante” after ahighly sensitive <strong>in</strong>vestigation of theearly European history of <strong>in</strong>ternationaltale type 333 treat the Levant<strong>in</strong>eeditions of the fairy tale surveyedby them (<strong>in</strong> Turkish, Armenian, andArabic) exclusively under the aspect ofto what extent they adapt the foreignstory to the respective cultural background– reach<strong>in</strong>g the unsurpris<strong>in</strong>gconclusion that none of the surveyededitions conta<strong>in</strong>s illustrations preparedby an <strong>in</strong>digenous artist? 14 What arewe to make of the fact that Germanl<strong>in</strong>guist Gunter Senft <strong>in</strong> his study ofthe tale of the brave tailor <strong>in</strong> the TrobriandIslands is almost exclusively<strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> how the orig<strong>in</strong>al fairy talebecame adapted to the alien culture<strong>in</strong> terms of language and content? 15Somehow these studies rem<strong>in</strong>d me ofwhat Werner Daum remarked yearsago about his field research undertaken<strong>in</strong> order to collect fairy tales <strong>in</strong>Yemen, when he wrote: “... and what Iheard everywhere did not <strong>in</strong>terest me:anecdotes of all types, witty stories... It was endlessly disappo<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g.” 16One aspect is common to the quotedstudies: They <strong>in</strong>vestigate their subjectaga<strong>in</strong>st the background of their ownexperience, their own expectationsand their own system of cultural values.Aga<strong>in</strong>st this background, possibleresults lie anywhere <strong>in</strong> between disappo<strong>in</strong>tmentat <strong>in</strong>sufficient capacities ofreception on the one hand and patronis<strong>in</strong>gstatements on the other hand,such as the statement that <strong>in</strong>digenouspeople like to learn and are will<strong>in</strong>g toadapt, perhaps are even open to consciousmanipulation 17 or demonstrate“a certa<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ner understand<strong>in</strong>g for theEuropean fairy tales” 18 .Contrast<strong>in</strong>g with the studiesquoted so far, there are a number ofstudies concerned with the receptionof European folk narratives <strong>in</strong> non-European cultures that demonstratea different degree of sensitivity visà-visalien values. In addition to USscholar Margaret Mills’s essays relat<strong>in</strong>gto Cupid and Psyche or C<strong>in</strong>derella<strong>in</strong> Afghanistan 19 , one might mentionseveral other studies. French AfricanistDenise Paulme supplies her<strong>in</strong>vestigation of a Cendrillon variant<strong>in</strong> Angola 20 with a detailed analysisof the role of women, of patterns ofmarriage and of familial relationships;the European reader who at first mighthave judged the f<strong>in</strong>al <strong>in</strong>cestuous relationshipbetween the hero<strong>in</strong>e andher brother as unsuitable, is thusenabled to understand it from a cul-

<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong> 9turally immanent po<strong>in</strong>t of view as theonly possible way of atta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g ultimatehapp<strong>in</strong>ess. James M. Taggart afteran extensive discussion of variantsof Hansel and Gretel <strong>in</strong> Spa<strong>in</strong> andMexico concludes that there is a relationshipbetween the symbolic contentof the stories and family relations <strong>in</strong>the Hispanic world 21 . And Cameroonscholar <strong>No</strong>rbert Ndong studies <strong>in</strong> greatdetail the references to liv<strong>in</strong>g reality<strong>in</strong> variants of Snow White told by anarrator <strong>in</strong> south Cameroon – while <strong>in</strong>his quality as a member of the studiedtradition group he obviously feltthe need to demarcate his researchaga<strong>in</strong>st the “proponents of a theoryregard<strong>in</strong>g the African people purelyas a consumer and not as a producerof culture” 22 .This second group of studiesdemonstrates how fruitful the conceptof hybrid cultures can be if researchersbecome aware of the factthat cultural exchange takes placealways and everywhere. Though thisassessment is fundamentally valid,both modern media and the mobilityof people <strong>in</strong> the modern world haveconsiderably expanded the temporaland geographic dimensions of communication.With the chang<strong>in</strong>g conditions,the question what ‘Alien’ actuallymeans and what is perceived asalien, and why and how, ga<strong>in</strong>s a newrelevance. A f<strong>in</strong>al example might serveto demonstrate this po<strong>in</strong>t.The Hamburg based sociol<strong>in</strong>guistMechthild Dehn has related thepoignant example of the migration ofa specific variant of Little Red Rid<strong>in</strong>gHood around the world 23 : her exampleorig<strong>in</strong>ates from an <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>in</strong>the fourth grade of elementary schoolaim<strong>in</strong>g to provoke pupils to “actualizecultural terms <strong>in</strong> the process of writ<strong>in</strong>g”.The Persian girl Maryam, whenoffered a choice of contemporarypopular characters (Pippi Longstock<strong>in</strong>g,Batman, Arielle, Aladd<strong>in</strong>, The LionK<strong>in</strong>g, etc.) decidedly opts to writeabout Little Red Rid<strong>in</strong>g Hood. Twopo<strong>in</strong>ts are particularly <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>her execution of the task: On the onehand, Maryam writes <strong>in</strong> Persian (andnot <strong>in</strong> German); on the other hand,the tale of Little Red Rid<strong>in</strong>g Hood isclearly not a component of traditionalIranian popular tradition. These discrepanciesare gradually expla<strong>in</strong>ed:Maryam has come to Germany onlya short while ago and does not commandthe language well enoughto write <strong>in</strong> German. She is familiarwith Little Red Rid<strong>in</strong>g Hood from achildren’s book <strong>in</strong> the Persian languagethat she had received fromone of her teachers. This text <strong>in</strong> turnturns out to be one of the numeroussimplified comic-book adaptations ofpopular stories orig<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g from Japaneseproduction that <strong>in</strong> contemporaryIran enjoys a considerable popularity.The adaptation clearly derives fromthe version presented by the brothersGrimm. In consequence, the tale toldby the Persian girl has made a voyagearound the world before return<strong>in</strong>g toGermany, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g several adaptationsand trans<strong>format</strong>ions <strong>in</strong> culturesalien to its place of orig<strong>in</strong>. Maryamregards her tale as a product of herown culture and is not aware of itslong and complicated history. At thesame time, the alien culture <strong>in</strong> whichMaryam lives at present also regardsthe tale as its own propriety while perceiv<strong>in</strong>gthe changes as alien.In order to decode similar processes,we need not only knowledge aboutthe respective cultural backgrounds <strong>in</strong>the sense of tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to account and<strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g facts. In addition to the accumulationand analytical apprehensionof factual evidence, knowledge hererather means sensibility and, aboveall, responsibility. The study of foreigncultures always implies a form of demarcation.In many ways, this demarcationof the ‘Self’ aga<strong>in</strong>st the ‘Other’cannot be avoided, s<strong>in</strong>ce researchersare always bound to act aga<strong>in</strong>st thebackdrop of their <strong>in</strong>dividual experience,much of which is related to the valuesof their orig<strong>in</strong>al culture and society. Buteven though a certa<strong>in</strong> alienation visà-visforeign cultures is unavoidable,the conscious effort to be aware ofone’s own background and limitationswill help to counterbalance the impliedcultural bias. In modify<strong>in</strong>g a statementfrom Eva Sallis’s book on the ArabianNights, the ideal folk narrative researcher“is not characterized by the absenceof prejudgmental cargo, but by a consciousnessof prejudgment and a willedma<strong>in</strong>tenance of flexibility” 24 . When striv<strong>in</strong>gfor a dialogue of cultures, or evenunderstand<strong>in</strong>g, the contemporary responsibilityof folk narrative researchis to contribute to public awareness ofcommon grounds and to evaluate andhonour the evident differences of hybridcultures as divergent yet fully equivalentforms of human expression.Ladies and gentlemen, dear colleagues!Two centuries after its <strong>in</strong>ception, thediscipl<strong>in</strong>e of folk narrative researchhas matured <strong>in</strong>to a major field of culturalstudies. Consider<strong>in</strong>g the closel<strong>in</strong>k between human existence and theexpression of human experience <strong>in</strong> narratives,we do not only study popularnarratives as they were passed on bytradition. Rather, we take <strong>in</strong>to accountpopular narratives as vibrant and activeconstituents of our contemporarydaily existence, regard<strong>in</strong>g them as thepivotal expression of cultural diversityand common concerns of humanity atthe same time. Judg<strong>in</strong>g from the conferenceabstracts I have had the pleasureto read, stag<strong>in</strong>g the present conference<strong>in</strong> Shillong and the state of Meghalayaimplies the tremendous chance for allof the participants to ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>toan otherwise little-known complex ofregional narrative tradition that at thesame time is part of a larger South Asianand South East Asian web of tradition.Moreover, by conven<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Shillong, the<strong>ISFNR</strong> takes pride <strong>in</strong> acknowledg<strong>in</strong>gthe scholarly achievements of Indianfolklore scholars and <strong>in</strong>stitutions. It isto be hoped that the present event willalso serve to support and strengthenthe study of folklore and folk narrative<strong>in</strong> the present <strong>in</strong>stitution. I am confidentthat the presentations of the conferenceparticipants will conv<strong>in</strong>ce the audienceas well as the responsible authoritiesof the discipl<strong>in</strong>e’s strong stand<strong>in</strong>g andits pivotal relevance for assess<strong>in</strong>g andunderstand<strong>in</strong>g the complexities of lifeas expressed <strong>in</strong> narratives, both from atraditional and a contemporary perspective.Let me thus express my s<strong>in</strong>cerewishes for a challeng<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong>spir<strong>in</strong>gmeet<strong>in</strong>g!

12<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong>The <strong>ISFNR</strong> Interim Conference 2011 <strong>in</strong> Retrospectby Pihla Siim, University of Tartu, EstoniaThe conference was organised by theDepartment of Cultural and CreativeStudies (<strong>No</strong>rth-Eastern Hill University– NEHU) under the guidance of thehead of the department, folklore professorDesmond L. Kharmawphlang.Once before, <strong>in</strong> 1995, an <strong>ISFNR</strong>meet<strong>in</strong>g was organised <strong>in</strong> India. Thatconference, organised by professorJawaharlal Handoo <strong>in</strong> Mysore, washistorical because it was the first<strong>ISFNR</strong> conference to take place outsideof Europe.<strong>No</strong>rth America. A little more than 30participants came from outside India.Some had cancelled their participationat the very last m<strong>in</strong>ute, asI understood. Estonia was very wellrepresented with eleven participants,probably thanks to Margaret Lyngdoh,who is a PhD student <strong>in</strong> folklore fromShillong, do<strong>in</strong>g her doctoral studies atthe University of Tartu.Pihla Siim is writ<strong>in</strong>g her dissertation abouttransnational families <strong>in</strong> Estonia, <strong>in</strong> F<strong>in</strong>land and<strong>in</strong> Russia.Photo by Toomas Pajula.In <strong>February</strong> 2011, the <strong>ISFNR</strong> <strong>in</strong>terimconference took place <strong>in</strong> Shillong,<strong>No</strong>rth-Eastern India, with the theme“Tell<strong>in</strong>g Identities: Individuals andCommunities <strong>in</strong> Folk Narratives”. Thisconference was my first <strong>ISFNR</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>gand probably very different fromthe ‘ord<strong>in</strong>ary’ ones – the location be<strong>in</strong>gso unusual and far away, if looked atfrom Europe. As we found out, evenfor Indians themselves, <strong>No</strong>rth-EasternIndia may represent someth<strong>in</strong>gdifferent, even frighten<strong>in</strong>g. I did notexperience it that way at all, s<strong>in</strong>cewe were very warmly welcomed andtaken good care of. Our hosts did awonderful job to make our stay thereunforgettable. I suppose the <strong>February</strong>was the ideal time for the meet<strong>in</strong>g, becauseit was not too hot, not too coldand not too wet either – just perfect.Shillong is the capital of Meghalaya,one of the smallest states <strong>in</strong> India. Becauseof the roll<strong>in</strong>g hills around thetown, it is also known as the “Scotlandof the East”. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the conference wecame to know and experience whyShillong is also known as the RockCapital of India.The first Indian department of folkloristicswas founded <strong>in</strong> 1972 at GauhatiUniversity, which is also the oldestUniversity <strong>in</strong> <strong>No</strong>rth-East India. The<strong>No</strong>rth-Eastern Hill University <strong>in</strong> Shillongwas established <strong>in</strong> 1973 and theCentre for Creative Arts was set up <strong>in</strong>1977. The Centre for Literary and CulturalStudies was started <strong>in</strong> 1984 withspecial emphasis on the folklore of the<strong>No</strong>rth-Eastern Region. In 1997, theabove two centres were re-structuredand amalgamated.The NEHU campus was located a littleoutside the city limits. All the servicesand departments seemed to beneatly and compactly situated near toeach other, and build<strong>in</strong>gs surrounded– a little surpris<strong>in</strong>gly – by p<strong>in</strong>e trees.The climate <strong>in</strong> Shillong was actuallyvery different from tropical India. Evenwhen driv<strong>in</strong>g the 100 kilometres fromGuwahati to Shillong we observed theastonish<strong>in</strong>gly large changes <strong>in</strong> nature,as well as the changes <strong>in</strong> the text andsymbols pa<strong>in</strong>ted on trucks, reflect<strong>in</strong>gthe different beliefs <strong>in</strong> these two towns.While H<strong>in</strong>duism is the ma<strong>in</strong> religion followed<strong>in</strong> Guwahati, there are a lot ofChristians (Presbyterians, Catholicsand Protestants) <strong>in</strong> Shillong, as wellas people who follow Khasi beliefs.There were around 100 participantsat the conference: from India, otherAsian countries, Europe, South andDesmond L. Kharmawphlang, the ma<strong>in</strong> organiserof the <strong>ISFNR</strong> <strong>in</strong>terim conference <strong>in</strong> Shillong.Photo by Merili Metsvahi.The conference had n<strong>in</strong>e sub-themes,most sizeable of them be<strong>in</strong>g “Ethnicityand Cultural Identity” and symposium“Belief Narratives and Social Realities”with 23 and 29 papers respectively.S<strong>in</strong>ce my research topic is related totransnational families, I was especially<strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> sub-themes “Identity andBelong<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a Transnational Sett<strong>in</strong>g”and “Places and Borders”. There were4–5 parallel sessions runn<strong>in</strong>g all thetime and here I can only shortly discusssome papers and themes that Ipersonally found most <strong>in</strong>spir<strong>in</strong>g.In his presidential address, UlrichMarzholph (Gött<strong>in</strong>gen, Germany)brought up the problem of Western-

<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong> 13centred folkloristics; most folkloristshave until recently received their education<strong>in</strong> the West and thus narrativetraditions of the world have been studiedpredom<strong>in</strong>antly from the Westernperspective. In addition, with<strong>in</strong> multiculturalstudies the perspective hasbeen ma<strong>in</strong>ly that of Western cultures(cf. also women’s studies: <strong>in</strong> ‘third countries’women have been very criticalabout the Western model claim<strong>in</strong>g tospeak for all women). We should furtheranalyse who this knowledge hasbeen produced by and to whom it hasbeen made available. Globalisation hasnot lead to equality yet – and probablynever will. Ulrich Marzholph posed an<strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g question: If we are study<strong>in</strong>gtraits/characteristics of our own culturefound <strong>in</strong> another culture, are we thenreally <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> other cultures? It isalways difficult to study the other withoutreflect<strong>in</strong>g our own culture, withoutstart<strong>in</strong>g from the classifications of ourown culture. One of the tasks for folkloristswould be, accord<strong>in</strong>g to Marzholph,to help to understand hybridity of cultures,and also to value this hybridity.We should not understand culture assometh<strong>in</strong>g bounded and ‘pure’; or pollutedwhen contacted and <strong>in</strong>fluenced byother cultures. Neither should we th<strong>in</strong>kthat one should def<strong>in</strong>e oneself with oneculture exclusively.William Westerman (New Jersey,USA) raised similar questions <strong>in</strong> hispaper, titled “Xenophobia, Narrativesof Migration, and the Sociol<strong>in</strong>guisticDraw<strong>in</strong>g of Borders”. He posed aquestion of what k<strong>in</strong>d of folklore weshould study – that which is pleasantand harmless, or should we also paymore attention to those moments andperiods when folklore turns ‘ugly’?Folklorists tend to turn their backs on‘unpleasant’ folklore. The case thatWilliam Westerman <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> hispresentation was immigration relatedhate speech generated <strong>in</strong> the socialmedia. His question was: if we don’tlook at that k<strong>in</strong>d of folklore, are we <strong>in</strong>that case quietly support<strong>in</strong>g it? He encouragedfolklorists to meet this challenge.We should be will<strong>in</strong>g to takepart <strong>in</strong> the complex moral discussionsL-R: Sadhana Naithani, Parag Moni Sarma and Sadananda S<strong>in</strong>gh (all from India) at the sessionon ethnicity and cultural identity.Photo by Pihla Siim.go<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>in</strong> our societies.The presenters from India touchedon the question of def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g ethnicityand cultural identity <strong>in</strong> many ways. Ienjoyed, for example, the paper byMr<strong>in</strong>al Medhi and Mira Kumara Das(Guwahati, India), who analysed identityconstruction among the Kumars <strong>in</strong>Guwahati us<strong>in</strong>g personal narratives.The Kumars used to live near the templeof Kamakhaya <strong>in</strong> Guwahati untilWorld War II, when they were given 72hours to evacuate from this area. Theauthors were <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> their evacuationexperiences, the memories and<strong>in</strong>terpretations that people gave to theevents and to their own lives. Most ofthe <strong>in</strong>terviewees were born <strong>in</strong> the currentsettlements, and thus reflected onthe experiences of their parents.The presentation by Sadhana Naithani(New Delhi, India) was also basedon lengthy fieldwork. Naithani hasbeen study<strong>in</strong>g folk performances <strong>in</strong>India, <strong>in</strong> traditional and non-traditionalfields, and discussed changes <strong>in</strong> theroles of folk performers. As societyand communities have changed, thecommunities of folk performers havebecome dispersed and modern valuesof performance – <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g commercialism– have been adopted. Naithanicriticised folklorists for lament<strong>in</strong>g thechanges, rather than analys<strong>in</strong>g them.To keep people <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> participat<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> performances, traditionshave to change along with society andcommunity. A dynamic phase of reformulationof traditions is tak<strong>in</strong>g placeand descriptive anthropology is notenough to document it. Accord<strong>in</strong>g toNaithani, what one should be worriedabout is the state not support<strong>in</strong>g theeducation of folk artists at schools.The state, <strong>in</strong>stead, is us<strong>in</strong>g folk forms<strong>in</strong> its own propaganda. In addition towhich the documentation of differentforms of performance is <strong>in</strong>sufficient.Etawanda Saiborne (Shillong, India),who gave her paper on the last dayof the conference, also touched onthe same theme. Communities haveexperienced big changes when fac<strong>in</strong>gthe processes of modernisation,globalisation and Christianisation.Saiborne compell<strong>in</strong>gly discussed thedifferent and even contradictory rolesof new media <strong>in</strong> the (re)production offolklore <strong>in</strong> these new contexts.One of the most positive sides ofthe Shillong conference was thepossibility to meet numerous Indianresearchers. While listen<strong>in</strong>g to theirpapers and discussions I also observedthe familiar juxtaposition ofemic versus etic accounts. There arepositive sides to be found <strong>in</strong> both ofthese standpo<strong>in</strong>ts – <strong>in</strong> study<strong>in</strong>g one’sown group, as well as <strong>in</strong> study<strong>in</strong>g fromthe outsider’s perspective. Still, as isoften the case, this theme seemed

14<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong>to be emotive. Some researchersfrom outside the communities theystudied, were accused of be<strong>in</strong>g toodispassionate and represent<strong>in</strong>g an“urban” view. On the other hand, acerta<strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d of reflexivity and analysisof the researcher’s role, as well asthe aims and effects of his/her study,are certa<strong>in</strong>ly needed when study<strong>in</strong>gone’s own community. I suppose oneof the eternal challenges for folkloristsis to balance these two viewpo<strong>in</strong>ts.As po<strong>in</strong>ted out earlier, folklorists alsoneed to be ready to take a stand <strong>in</strong>relation to societal questions – andalso when a somehow repulsive politicalaspect is present.<strong>ISFNR</strong> Review: Shillong Lives up to Its Reputationby Meenaxi Barkataki-Ruscheweyh,Academy of Sciences and Georg-August-University of Gött<strong>in</strong>gen, GermanyIt was <strong>in</strong> Kohima, capital of the <strong>No</strong>rth-East Indian state of Nagaland, <strong>in</strong> December2010, that I first heard of theInterim meet of the <strong>ISFNR</strong> to be held<strong>in</strong> Shillong <strong>in</strong> <strong>February</strong> 2011. I was<strong>in</strong> Kohima to attend the annual sessionof the Indian Folklore Congress(IFC). Many of the participants at theIFC were plann<strong>in</strong>g to also attend the<strong>ISFNR</strong> meet. I was a bit surprised tohear that two such big events wouldbe held so soon after one another,<strong>in</strong> more or less the same part of theworld. But a rapid run of the <strong>ISFNR</strong>website conv<strong>in</strong>ced me that the <strong>ISFNR</strong>was <strong>in</strong> a different league altogether.Although I could see that I had missedall deadl<strong>in</strong>es I thought I’d try ask<strong>in</strong>g.Desmond’s answer was clear – yes,I could participate but no, I could notpresent a paper. Sometimes that canbe the most convenient arrangement,s<strong>in</strong>ce you don’t have to feelguilty about not hav<strong>in</strong>g presentedsometh<strong>in</strong>g. Also s<strong>in</strong>ce I am not technicallya folklorist, I was relieved thatI wouldn’t need to pretend to be one.So I happily made plans to attend.And I’m glad I did. For those four days<strong>in</strong> Shillong were a real treat. I am notsure how this meet compares withother Interim <strong>ISFNR</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>gs s<strong>in</strong>cethis was my first contact with the<strong>ISFNR</strong>, but for Shillong, perhapseven for India, it was a really bigshow, with more than a hundredparticipants of which a sizeableproportion were from outside theregion. The facilities at NEHU haveimproved significantly over the yearsand the Guest Houses, ConferenceRooms and technical <strong>in</strong>frastructurewere as good as anywhere else <strong>in</strong>the world. The army of very friendlyand helpful volunteers kept th<strong>in</strong>gsgo<strong>in</strong>g and Desmond Kharmawphlangdid an amaz<strong>in</strong>g job of keep<strong>in</strong>g everyth<strong>in</strong>gtogether. And for me, com<strong>in</strong>g asI did from the outside, both <strong>in</strong> termsof the discipl<strong>in</strong>e and the fact that althoughI am Assamese, I now live andwork <strong>in</strong> Germany, it made me proudto belong to this region and to havethe chance to show ourselves off tothe rest of the world.The very impressive <strong>in</strong>augural sessionset the tone for the rest of theconference – the presence of theGovernor of Meghalaya at the <strong>in</strong>augurationlent ceremony and glamour tothe proceed<strong>in</strong>gs, and the presidentialaddress of Professor Ulrich Marzolph,President of the <strong>ISFNR</strong>, set the benchmarkfor the high academic standardfor the event by giv<strong>in</strong>g a systematicaccount of the historical developmentsas well as the present concerns andpriorities of the <strong>ISFNR</strong> as well as offolklore studies worldwide.The other star of the meet, at least <strong>in</strong>terms of his engagement with <strong>No</strong>rth-East India, was Professor Ülo Valkfrom Estonia. In addition to ask<strong>in</strong>gme to write this article for the newsletter,Professor Valk also told me of anMeenaxi Barkataki-Ruscheweyh is do<strong>in</strong>g researchamong the Tangsa ethnic m<strong>in</strong>ority <strong>in</strong>Assam and Arunachal Pradesh.Photo by Pihla Siim.agreement between Gött<strong>in</strong>gen Universityand his own university which couldenable me, as a student at Gött<strong>in</strong>gen,to visit the University of Tartu. I wasalso excited to meet the celebratedfolklorist Sadhana Naithani, aboutwhom I had been hear<strong>in</strong>g for manyyears now, and she certa<strong>in</strong>ly did notdisappo<strong>in</strong>t.Of the many sessions and papers Iattended, my personal favourites werethe talks by Mark Bender (USA) onoral traditions <strong>in</strong> south-west Ch<strong>in</strong>a andthat of Ulf Palmenfelt (Sweden) on <strong>in</strong>dividualhistories and collective localhistories of a community. There were

<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong> 15a few new trend sett<strong>in</strong>g papers too,especially the one by the very youngAmerican folklore student JeanaJorgensen. Look<strong>in</strong>g at her many neatpie charts with percentages and proportions,scepticism aris<strong>in</strong>g from mymathematics background made mewonder if ‘catalogu<strong>in</strong>g gender andbody <strong>in</strong> European fairy tales’ us<strong>in</strong>gmodern technology will tell us significantlymore than what we alreadyknow (or can reasonably guess) aboutattributes like beauty and age. Talksby a few young Assamese and Mizofolklorists were also very <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g.I immensely enjoyed the talks aboutlocal landscapes, places and bordersand their role <strong>in</strong> fram<strong>in</strong>g identity narrativesand could sense that this wasprobably another excit<strong>in</strong>g new directionthat folklore studies would take <strong>in</strong>the next years. And many times dur<strong>in</strong>gthose four days there was so muchthat <strong>in</strong>terested me that I was not surewhether I was turn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to a folkloristor whether this was just an illustrationof the fact that folklore and anthropologyhave a lot <strong>in</strong> common, much morethan either care to admit.There were quite a few scholars fromthe <strong>No</strong>rdic and Scand<strong>in</strong>avian countrieswho had all done amaz<strong>in</strong>g work. Listen<strong>in</strong>gto the <strong>in</strong>credibly meticulous andm<strong>in</strong>utely researched documentationdone by several such folklorists <strong>in</strong> theirtalks I wondered whether the age oldSudheer Gupta from New Delhi <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>ghis film.Photo by Merili Metsvahi.stereotypical images of the cold andserene landscapes of their country andtheir reserved and quiet natures madethem naturally suited for folklore studies.On the other hand, there was notmuch talk about Africa (or for that matterabout Australia and Lat<strong>in</strong> America).One can’t have it all, I suppose.On the whole, there were some greatsessions with some excellent papers.S<strong>in</strong>ce questions of identity, ethnicityand cultural constructs <strong>in</strong>terest me Itried to attend as many talks on thosethemes as I could. There were fiveparallel sessions at any given po<strong>in</strong>tof time. Parallel sessions are unavoidableI guess <strong>in</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>gs of this scale.What could have been avoided, however,is hav<strong>in</strong>g parallel sessions withthe same theme. I kept wonder<strong>in</strong>g whythe division of themes was not donevertically across time <strong>in</strong>stead of horizontallyacross locations. The otherfactor that severely restricted choicewas the fact that the 5 venues werenot all located <strong>in</strong> one build<strong>in</strong>g. That oftenimplied that participants could notreally choose talks, rather they had tochoose sessions, and s<strong>in</strong>ce the fivesessions often had to do with at mosttwo or three thematic categories. Typically,a participant wished he could bepresent at several places at the sametime for certa<strong>in</strong> sessions and couldnot f<strong>in</strong>d even a s<strong>in</strong>gle talk of <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong> some others.In addition, as is <strong>in</strong>evitable at suchlarge gather<strong>in</strong>gs, there were quite afew last m<strong>in</strong>ute cancellations. Thiskept people wonder<strong>in</strong>g until the lastm<strong>in</strong>ute and did cause some confusionas the programme was not updatedat all once the conference got underway. On some occasions, participantshav<strong>in</strong>g arrived at a venue would f<strong>in</strong>dout that an entire session had been reducedto a s<strong>in</strong>gle paper or had lapsedcompletely, which was not very pleasant.Gett<strong>in</strong>g to read the papers <strong>in</strong> theconference proceed<strong>in</strong>gs would havebeen some consolation. But I wassurprised to hear that the practice ofpublish<strong>in</strong>g the proceed<strong>in</strong>gs has beendiscont<strong>in</strong>ued. I don’t know what thereasons are, but it would be great ifthe practice could be revived.Given the many cancellations, it wouldhave been much nicer to have planneda few more plenary sessions. The solitaryplenary session, apart from theopen<strong>in</strong>g event, was on the last day, forwhich many new people arrived on thescene. While Professor A.C. Bhagabatidid a great job of chair<strong>in</strong>g that sessionand Professor J. Handoo was at hisusual combative best, I couldn’t helpwonder<strong>in</strong>g why Professor BirendranathDatta, who is undoubtedly a very seniorand much respected folklorist fromthe region, and certa<strong>in</strong>ly one of thebest known folklorists <strong>in</strong> the country,was not there to share his thoughtswith the gather<strong>in</strong>g.But there were a few other th<strong>in</strong>gs aswell that I couldn’t figure out, for example,the reason for the complete lackof <strong>in</strong><strong>format</strong>ion on the <strong>in</strong>ternet aboutthe actual programme dur<strong>in</strong>g the runupto the event – I was perhaps do<strong>in</strong>gsometh<strong>in</strong>g stupidly wrong all the timebecause despite look<strong>in</strong>g repeatedlyat what looked like the official conferencewebsite I did not manage tof<strong>in</strong>d out what the conference registrationfees for Indian participants was,also if there was a late fee; nor did Imanage to locate the third announcementwhich was supposed to conta<strong>in</strong>the detailed programme. Other participantstold me that they had alsohad trouble with the website and hadfound out when they were scheduledto speak by mail<strong>in</strong>g Desmond. S<strong>in</strong>ce Iwas only go<strong>in</strong>g to listen, I didn’t botherhim but kept wish<strong>in</strong>g that the websitewould tell me more.While listen<strong>in</strong>g to the talks by theforeign scholars gave me the chanceto learn about new areas and topics,the talks by folklorists from the regionoften gave me a sense of deja-vu,often also enabl<strong>in</strong>g me to seefamiliar th<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> a new light. Andsometimes when I was just sitt<strong>in</strong>garound, unable to decide which talkto go to, and chatt<strong>in</strong>g with whoeverhappened to be nearby, I had the feel<strong>in</strong>gthat while Western scholars today

16<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong>Some of the conference organisers and participants. L-R: Desmond L. Kharmawphlang, BettyLaloo, Elishon Makri, G. Badaiasuklang Lyngdoh <strong>No</strong>nglait, Ulrich Marzolph and Chitrani Sonowal.Photo by Merili Metsvahi.might be more than ready to give uptheir superior attitudes and to treat Indianscholars as friends and equals,the colonial hangover was tak<strong>in</strong>g longerto leave the local scholars, many ofwhom seemed not quite ready to stopbe<strong>in</strong>g deferential and servile to theirEuropean counterparts, simply on thebasis of sk<strong>in</strong> colour. It is perhaps thisvery phenomenon that prevents usfrom strik<strong>in</strong>g out on our own and formulat<strong>in</strong>gour own paradigms, despiteliv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a region that has so much tooffer <strong>in</strong> terms of folklore.In that sense I did hope that this meet<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> Shillong, which brought thesetwo worlds to an undifferentiated commonplatform, would perhaps help localscholars to shed their diffidenceand beg<strong>in</strong> to speak their m<strong>in</strong>ds a littlemore boldly. Many papers presentedat the meet were excellent illustrationsof the very high demands of presentday academic scholarship. There weremany great lessons to be learnt. Inthat sense it was a pity that mostof the volunteers at the conference,many of whom were young students offolklore, could not attend the talks (orthey could not pay attention to whatwas be<strong>in</strong>g said, even though theywere present at the venue) be<strong>in</strong>g busywith mundane organisational chores.The cultural programmes which<strong>in</strong>terspersed the academic sessionswere as motivat<strong>in</strong>g and of the sameelevated standards as the sessionsthemselves. The spectacular culturalprogramme on the even<strong>in</strong>g of thefirst day was very colourful and veryenterta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. I was quite amazed atthe professionalism and the technicalperfection of the artists. Furthermore,the cultural events every even<strong>in</strong>gconveyed a very good sense not justof the colourful ethnic diversity ofthis region but also of how Westernmusic has come to play a big part <strong>in</strong>the lives of the Khasis and the otherhill people of the region.Also very impressive was SudheerGupta’s documentary film, which wasscreened just after the sessions endedon the second day. Over and abovethe s<strong>in</strong>gularly <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g theme of theseamless manner <strong>in</strong> which multiplereligions seem to flow <strong>in</strong>to one another<strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> parts of India as illustratedby the community of Muslim Jogi s<strong>in</strong>gersportrayed <strong>in</strong> that film (who stillcelebrate the H<strong>in</strong>du festival of ShivaRatri), the <strong>in</strong>credible c<strong>in</strong>ematographictechniques Gupta employs <strong>in</strong> the filmwere very impressive.I cannot end before I use this chanceto express my thoughts about someth<strong>in</strong>gwhich has begun to bother mevery much <strong>in</strong> recent times – for whilethere was so much be<strong>in</strong>g said aboutvarious folk traditions, narrativesand practices <strong>in</strong> different parts of theworld, most conspicuous by their absencewere the ‘folk’ themselves. Thelonger I have been work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the field,the more conv<strong>in</strong>ced I have becomethat we must <strong>in</strong>clude our folk s<strong>in</strong>gersand storytellers <strong>in</strong> some real sense <strong>in</strong>our learned discussions and deliberationsabout them. I can speak onlyfor myself, and I am not really surehow to go about do<strong>in</strong>g this, but asa native researcher, work<strong>in</strong>g with myown people, I am conv<strong>in</strong>ced that forme it is collaborative much more thanparticipatory ethnography that must bepractised. But it didn’t seem to bothertoo many others at the meet. It wouldhave made me so happy to have actuallyseen a few Khasi storytellers ortraditional priests sitt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> at least atthe talks when their ‘lore’ was be<strong>in</strong>ganalysed and be<strong>in</strong>g given a chanceto speak for themselves.Perhaps that is mere wishful th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>gat this po<strong>in</strong>t of time. But the ambienceof the beautiful and sprawl<strong>in</strong>g NEHUcampus was conducive to such daydream<strong>in</strong>g. To end, by attend<strong>in</strong>g the<strong>ISFNR</strong> meet at Shillong I learnt a lot,met some wonderful people, heardsome superb talks, made some newfriends, and have had the pleasureonce more of wander<strong>in</strong>g around underthe enchant<strong>in</strong>g p<strong>in</strong>e trees <strong>in</strong> thebeautiful NEHU campus dream<strong>in</strong>gabout what is and what could be... Icouldn’t have wished for much more.

<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong> 17An Experience from Indiaby Sarmistha De Basu, The Asiatic Society, Kolkata, IndiaSarmistha De Basu delivered a paper on urbanfolklore <strong>in</strong> Kolkata and West Bengal.Photo by Merili Metsvahi.Surrounded by the scenic beauty ofone of India’s most beautiful citiesShillong, known as the Scotland of theEast, the <strong>No</strong>rth Eastern-Hill Universityarranged the Interim Congress of the<strong>ISFNR</strong> 2011. It was my pleasure andpride to participate <strong>in</strong> this conferenceas a member of this prestigious organisation.The conference was well organisedwith one symposium, one dedicatedsession and six sub-topics. I attendedsome selected lectures of my own<strong>in</strong>terest but tried to share ideas withvarious participants from multiple discipl<strong>in</strong>eswho had flown <strong>in</strong> from manyparts of the world. It was a grand experience<strong>in</strong>deed. Another <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>gth<strong>in</strong>g was to roam around the vastarea of the university and <strong>in</strong>troduceoneself to the conveners and scholarswho made the whole effort successful.The ma<strong>in</strong> theme of the conferencewas to explore identities of <strong>in</strong>dividualsand communities <strong>in</strong> folk narrative,which was successfully covered bythe four sub-topics. The ma<strong>in</strong> subtopic‘Ethnicity and Cultural Identity’covered community identity whereas‘Identity <strong>in</strong> the History of Folkloristics’covered the national identity of differentcasts and societies. ‘Revisit<strong>in</strong>gColonial Constructs of Folklore’ wasthe sphere <strong>in</strong> which folkloric identitiesof colonial communities came to ourattention and ‘Identity and Belong<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> a Transnational Sett<strong>in</strong>g’ was alsovery <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g. Of the other two subtopics,‘Places and Borders’ and ‘TheMak<strong>in</strong>g and Mapp<strong>in</strong>g of Urban Folklore’,my paper was on the later. Theidentity crisis is a great problem andthe subject matter is also very complicated.Perhaps, we can sort out alarge portion of these issues from afolkloristic angle.There were many <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g papers<strong>in</strong> the ‘Belief narratives and socialrealities symposium’ sessions. Thescholars who participated from <strong>No</strong>rth-East India took the chance to expresstheir local beliefs and the realities oftheir condition <strong>in</strong> these sessions.Some of their papers were quitethought provok<strong>in</strong>g. Besides, therewere various <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g papers fromEstonia, Serbia, Argent<strong>in</strong>a and theUSA.In the 24 th <strong>February</strong> afternoon sessionwe met Sudheer Gupta, a scholarc<strong>in</strong>ematographer who presented hislecture demonstration with his shortfilm on Rajasthan’s street s<strong>in</strong>ger family.This family has pursued this professiongeneration after generationnot only due to extreme poverty orlack of education, but also becausethey feel proud enough to <strong>in</strong>herit andcont<strong>in</strong>ue their age-old tradition. Thatsession was excellent and we enjoyedthe film very much.Another presentation of the city puppetshow from Manpreet Kaur, anem<strong>in</strong>ent scholar from Delhi also shonea new light on contemporary experimentation<strong>in</strong> the process of <strong>format</strong>ionof urban folklore. On 25 th <strong>February</strong> animportant session was arranged bythe organiser dedicated to Indira GandhiNational Centre for the Arts, NewDelhi, on <strong>No</strong>rth-East India and South-East Asia: Inter Cultural Dialogue.In recent times, this particular themehas been emphasised by the CentralGovernment of India among the modernresearch scheme on socio-culturalaspects. Therefore, a special effortwas given to the three sessions of thistheme. The first session was held on22 nd <strong>February</strong> and the second along withthe third on 25 th <strong>February</strong>. Papers on the‘Cult of Goddess Tara to the Mode ofWorship <strong>in</strong> Umpha-Puja’ (by ArchanaBarua), ‘Durgabori Ramayan’ (by Prab<strong>in</strong>C. Das and Monika Chutia) and ‘IndigenousNaga (serpent) Cult: a Study ofAssam (India) and Thailand’ (by SanghamitraChoudhury and Pratima Neogi)were also very appeal<strong>in</strong>g.This conference was held <strong>in</strong> India andas I am an Indian participant, I wasable to meet many known scholarshere with whom there were no <strong>in</strong>teractionsotherwise. It was a k<strong>in</strong>d of reunionfor us tak<strong>in</strong>g this opportunity.Interaction with them enriched myexperience many fold. In addition I<strong>in</strong>teracted directly with <strong>ISFNR</strong> members,the President and Vice presidentfor the first time at the conference andI consider it to be very encourag<strong>in</strong>g.This k<strong>in</strong>d of personal meet<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong>scholars from different countries def<strong>in</strong>itelymakes a conference successful.An exhibition of national and <strong>in</strong>ternationaljournals and books was heldwhich was very rich <strong>in</strong> the quality ofthe authors and publishers. I benefittedby be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formed about various<strong>in</strong>ternational journals, such as Folklore.Electronic Journal of Folklore,published <strong>in</strong> Estonia, e-journals aboutsocio-cultural studies, etc.The co-operation of the programmecommittee members, food and f<strong>in</strong>anceassistants, book exhibition assistantsand public relations assistants werevery much appreciative. However, I donot th<strong>in</strong>k it will be out of place to putone suggestion. I request the authorityto publish the entire programme with

18<strong>February</strong> <strong>2012</strong>details on the website beforehand andit was quite helpful <strong>in</strong> arrang<strong>in</strong>g myown schedule.L-R: Ülo Valk (Estonia), Soumen Sen, P. Subbachary and Ranjeet S<strong>in</strong>gh Bajwa (all from India)at the <strong>ISFNR</strong> <strong>in</strong>terim conference <strong>in</strong> Shillong.Photo by Merili Metsvahi.locations on the <strong>ISFNR</strong> website beforethe conference. It will be very helpfulfor participants to plan their attendanceaccord<strong>in</strong>gly at the conference. Ido remember that the 15 th Congress<strong>ISFNR</strong> authorities gave all programmeIn the free sessions and after theconference we did not forget to enjoythe beauty of Shillong. We visitedWards Lake, Umiam Lake, Cherrapunji,Mous<strong>in</strong>gram, and enriched ourexperienced by visit<strong>in</strong>g various waterfalls.Our footpr<strong>in</strong>ts were found at localmarketplaces like Police bazaarwhere<strong>in</strong> we met the local people, collectedgifts and souvenirs for friends,colleagues, guides and relatives. Wewent to Kaziranga, a wildlife sanctuary<strong>in</strong> Assam after the conference wasover. It was also an amaz<strong>in</strong>g experienceand an extra opportunity to knowthe place where the conference wasarranged.Impressions of the Local Aspect of the <strong>ISFNR</strong> Interim Conference,Shillong, 2011. Tell<strong>in</strong>g Identities: Individuals and Communities <strong>in</strong>Folk Narrativesby Mark Bender, The Ohio State University, Columbus, USAThe Interim Conference of the InternationalSociety for Folk NarrativeResearch was held at the <strong>No</strong>rth-EasternHill University, Shillong, Meghalaya,from the 22 nd to 25 th of <strong>February</strong>, 2011.It allowed participants from around theworld a chance to engage with scholarsfrom various places <strong>in</strong> the north-eastL-R: Mark Bender (USA) and Ergo-Hart Västrik (Estonia) at the <strong>ISFNR</strong> <strong>in</strong>terim conference <strong>in</strong>Shillong. Mark Bender has published several books on oral traditions and performance <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Han and ethnic m<strong>in</strong>ority cultures.Photo by Merili Metsvahi.and other parts of India. The multiculturalregion is home to hundreds of localcultures, many with cultural and l<strong>in</strong>guisticsl<strong>in</strong>ks to peoples <strong>in</strong> South-East Asiaand Ch<strong>in</strong>a. The sponsor<strong>in</strong>g organ wasthe dynamic Department of Cultural andCreative Studies at the <strong>No</strong>rth-EasternHill University, Shillong. The Departmentstarted as a centre founded <strong>in</strong>1984 by Prof. Soumen Sen. The centreproduces world-class researchand nurtures a cohort of well-tra<strong>in</strong>edgraduate students <strong>in</strong> folklore andcultural studies under the guidanceof educators that <strong>in</strong>clude the <strong>ISFNR</strong>conference organiser Desmond L.Kharmawphlang. Conference participantswere exposed to many aspectsof the multicultural matrix of <strong>No</strong>rth-EastIndia dur<strong>in</strong>g the welcome ceremony,which <strong>in</strong>cluded a multicultural folkdance program, various food events,and a conference program filled withtalks and papers on various aspectsof folk narrative and culture <strong>in</strong> <strong>No</strong>rth-East India.