Mark Gudesblatt, MD

Mark Gudesblatt, MD

Mark Gudesblatt, MD

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

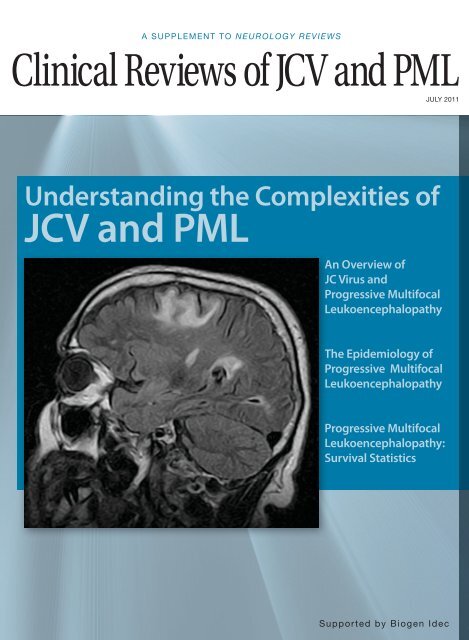

A SUPPLEMENT TO NEUROLOGY REVIEWSClinical Reviews of JCV and PMLJULY 2011Understanding the Complexities ofJCV and PMLAn Overview ofJC Virus andProgressive MultifocalLeukoencephalopathyThe Epidemiology ofProgressive MultifocalLeukoencephalopathyProgressive MultifocalLeukoencephalopathy:Survival StatisticsSupported by Biogen Idec

Understanding theComplexities ofJCV and PMLCONTENTSAn Overview of JC Virusand Progressive MultifocalLeukoencephalopathy ..................................S3<strong>Mark</strong> <strong>Gudesblatt</strong>, <strong>MD</strong>The Epidemiology ofProgressive MultifocalLeukoencephalopathy ................................S10John F. Foley, <strong>MD</strong>Progressive MultifocalLeukoencephalopathy:Survival Statistics ............................................S17Moti L. Chapagain, PhDSUPPLEMENT EDITOR<strong>Mark</strong> <strong>Gudesblatt</strong>, <strong>MD</strong>FACULTY<strong>Mark</strong> <strong>Gudesblatt</strong>, <strong>MD</strong>John F. Foley, <strong>MD</strong>Moti L. Chapagain, PhDS2 July 2011 • Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML

An Overview of JC Virusand Progressive MultifocalLeukoencephalopathy<strong>Mark</strong> <strong>Gudesblatt</strong>, <strong>MD</strong>Chief of Neurology, Brookhaven MemorialHospital Medical Center, Brookhaven, NY,and South Shore Neurologic Associates, PC,Bay Shore, New York.Dr. <strong>Gudesblatt</strong> is a consultant for Biogen Idec,Teva Neuroscience, Medtronic, Inc, and Lundbeck Inc.IntroductionThe risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy(PML) has been traced to an otherwiseinnocuous acquisition of the JC virus (JCV). Afteran asymptomatic primary infection, JCV, ahuman polyomavirus, typically persists in a quiescentstate without clinical consequences. 1 Thegenesis of PML, a rare complication of JCV, is dependenton a series of events that permit the virusto become active within the central nervous system(CNS). 2 Although JCV was isolated in 1971, 3much of the progress in understanding the pathophysiologyof PML was subsequent to the steepincrease in cases associated with the epidemic ofhuman immunodeficiency virus (HIV). 2 Recentattention to the causes and prevention of PMLis driven by a small but accumulating number ofcases associated with the use of immunomodulatingdrugs prescribed for such indications as organtransplant or chronic autoimmune diseases. 1 Theinfrequency of PML even in the most vulnerablepopulations suggests that the complex molecularroute from asymptomatic JCV infection to a fulminantCNS disease is potentially modifiable. 4While increased survival has been seen with somebiological therapies, such as natalizumab formultiple sclerosis (MS), risk stratification prior toinitiating immunosuppressive drugs may furtherreduce PML cases. 5JCV: Biological PropertiesJCV, named from the initials of the first patient inwhom the virus was isolated, is a 5.1-Kb doublestrandedDNA virus with only 5100 base pairs buta large coding region, representing 90% of its viralgenome. 6 Like the BK virus, another polyomavi-Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML • July 2011 S3

us of the genus Papovaviridae that was firstisolated at about the same time, JCV is presentin the majority of the human population.7 Infectivity rates are highly varied (33%to 91%) 8 depending on the method of detectionused and the age, gender, and underlyingstatus of the population being tested. JCVis currently felt by some to be typically acquiredin childhood, adolescence, or youngadulthood. 9 Although some believe that themajority of infections are acquired before age10, the risk for exposure and infection continuesthroughout adulthood. 10 The primaryinfection appears to occur in tonsil or gastrointestinalepithelial cells. 11 At the time of acquisitionand throughout its latent state, theinfection remains asymptomatic. 1After primary infection, latent JCV canpersist lifelong in one or more of several tissues,most likely the kidney, the bone marrow,and the lymph glands. 12 Latent infection in theCNS is possible, but its frequency and relativeimportance to PML are unclear. 12 AlthoughJCV infects a narrower range of cell types thanthe BK virus, other polyomaviruses, such asthe more recently identified WU and KI types,which predominately affect respiratory tissue,also appear to initially infect a relatively smallnumber of cell targets. 10One method currently identified for JCVto bind to cells is via the N-linked glycoproteinwith an alpha-(2-6)-linked sialic acid orthe serotonin 5-HT2a receptor. 13,14 It enters thecell through endocytosis. 15 At least 14 genotypesof JCV have been identified. 16 All areunique to the human host. These are associatedwith specific racial groups or geographicregions. For example, types 1 and 4 predominatein Europe, while types 3 and 6 predominatein Africa. 17The non-coding control region (NCCR)defines JCV genotypes. This region, which determinesgene regulation and viral replication,is relatively stable and may not be a strong determinantof pathogenicity. In contrast, thegene sequence of the regulatory region, whichmay be important for hematogenous spreadof the virus into the CNS, 18 has been characterizedas hypervariable. 1 Relative to the regulatoryregion of quiescent, archetypal JCV, theregulatory region of pathogenic forms of JCVin patients with PML typically contains multipledeletions and duplications. 19 Activationof the virus is associated with transcription ofthe agnoprotein as well as the VP1, VP2, andVP3 caspids, which are thought to be essentialfor viral propagation. 20 Other proteins transcribedin the regulatory region of the genomemay interfere with T antigen functions. 21 Forthese reasons, reconfiguration of the NCCR isconsidered to be important to both the neurotropismand the neurovirulence that is likelyto define the risk of PML.JCV infection, presumed to have coexistedin the human population for millennia, is sufficientlyubiquitous that it has been proposedas a target of the co-divergence studies employedto trace both human migration andevolution. 22 Although subsequent analysesdetermined that the phylogeneses of JCV andhumans are not sufficiently similar to servethis purpose, 16 the polyomaviruses overalland JCV in particular may be useful for betterunderstanding the interrelationship betweenviral infections and human defenses. Recognizedfor only 50 years, the five human polyomaviruses,which, in addition to the JC, BK,WI, and KU viruses, include the Merkel virus,are all seen with high prevalence rates butwith low risk of clinical disease. 10 While latentpolyomavirus infection is typical, JCV may reactivateperiodically in infected tissues, basedon viral shedding in the urine, without clinicalconsequences. 23PML: Description of Clinical FeaturesPML is the only demyelinating disorder directlylinked to an active virus. 24 The disorderis characterized by productive JCV infectionof cells in the CNS, particularly oligodendrocytes.The importance of other cell types inPML, such as astrocytes, also appears to be significant.A definitive diagnosis of PML, whichhas nonspecific clinical signs and symptoms,is considered to be detection of JCV DNA indemyelinated lesions on brain tissue or centralspinal fluid, often with DNA hybridizationor polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifi-S4 July 2011 • Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML

cation. Although PML is generally consideredto be an opportunistic infection in immunocompromisedpatients, such as individualswith acquired immunodeficiency syndrome(AIDS) or individuals taking an immunomodulatoryor immunosuppressant therapy, therehave been a few cases of PML in individualsconsidered to be immuno competent. 25The infection of oligodendrocytes is a lyticprocess that leads to pathological alterationsin the cerebrum, cerebellum, and brain stem.On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), multiplediffuse asymmetrical lesions are typicallyfound in the subcortical hemispheric whitematter and cerebellar peduncles. 1 Lesionsmay also be found in the grey matter. Reactivegliosis and giant, multinucleated astrocytesare also observed in affected areas. Lesionsare not usually edematous and they can begenerally distinguished from lesions associatedwith MS by a variety of features, such asa low likelihood of enhancement on gadoliniumMRI imaging, configuration, andthe appearance on diffusion-weightedimaging (DWI).PML may manifest in any one ormore of a broad array of neurologicsymptoms, including limb weakness,gait abnormalities, paresis, cognitivedeficits, psychiatric and behavioral changes,and speech or visual deficits. The most commonof these features, limb weakness, is reportedby about half of patients. 26 Patientsmay report sensory disturbances. Headachesare reported by about 10%.Although detection of JCV DNA in a demyelinatedlesion is considered a definitivesign of PML, and presence of JCV DNA in thecerebrospinal fluid (CSF) confirms diagnosisof PML, the correlation between JCV in blood(viremia) and the presence of PML is modesteven with serial measurements. In HIV patientswith PML, for whom there is the greatestexperience in the detection and evaluationof PML, only about half had detectableJCV viremia on serial analyses. 27 A variety oftests have been developed to facilitate diagnosisof PML through detection of JCV, includinga polyclonal antibody test for the JCVagnoprotein, 28 which appears to be presentonly in cases of virulent infection. Enzymelinkedimmunosorbent assays (ELISA) 29 havebeen developed as predictive tools, but somepatients with PML have low or undetectableJCV in the CSF. Even PCR amplification testing,which is generally considered the mostsensitive, has generated false-negative testsin patients with PML. 30 Low serum or CSFJCV titers do not correlate with brain tissuedamage, although they might correlate withsurvival. 31 A diagnosis of presumed PML canbe made on the basis of clinical features,combined with MRI findings, in the absenceof alternative diseases, even in the absence oflaboratory-detectable JCV. 32JCV as Causative Agent of PMLThe events that lead from asymptomatic JCVinfection to overt PML remain controversial.Although immunosuppression is strongly implicatedin the pathway from a quiescent toUltimately, understanding thetransformation of JCV to its virulent formsmay be a more important target of controlthan promoting immune response.an active virus, the role of reactivation is notclear. The reactivation hypothesis is built onthe premise that diminished immune defensespermit a previously dormant virus to replicaterapidly at the sites of latency. In this hypothesis,PML occurs after the virus mutatesinto a virulent form and crosses the bloodbrainbarrier (BBB). However, this is not fullyconsistent with some laboratory and clinicalobservations. In particular, the reactivationof JCV may be less important than a far morecomplex interrelationship between immunedefenses and JCV replication. One argumentagainst reactivation is that fulminant JCV andPML remain very rare events in immunosuppressedindividuals. The trigger for transformationthat confers JCV with virulence andneurotropic properties may be more significantthan an increased rate of replication. Recentevidence suggests that mutations in theClinical Reviews of JCV and PML • July 2011 S5

VP1 capsid protein are associated with the developmentof PML. 33 Ultimately, understandingthe transformation of JCV to its virulentforms may be a more important target of controlthan promoting immune response.The factors that alter the NCCR of JCV toincrease its pathogenicity have been difficultto isolate in the absence of an animal model.Several proteins implicated in cell-type–specificregulation of JCV DNA transcriptionhave been isolated. For example, substantialresearch has been devoted to evaluatingwhether NF-1X, which is a member of theNF-1 family of functional proteins, is involvedin modification of JCV gene function. In humanglial cell lines, expression of NF-1X hasbeen associated with increased susceptibilityto JCV. 34 Conversely, loss of susceptibilityto JCV infection has been associated withloss of NF-1X expression. Other DNA-bindingproteins, such as c-Jun and GBP-1, have alsobeen pursued for their ability to alter nucleotidesequence arrangements in the JCV regulatoryregion.Due to the variability in outcomes ofPML, the relative pathogenicity conferred bychanges in the regulatory genes of JCV is likelyto be an important factor. These rearrangementsmight act on numerous variables thatinfluence the ability of JCV to produce PMLor affect its severity. One classification systemattempted to match sequence differencesin JCV variants with characteristic behavior,such as relative cell tropism in the CNS andrates of replication. 35 The interaction betweenthe genetic transformation of JCV from its archetypeand its relative ability to predict riskof PML or even risk of adverse outcomes inthose who develop PML may lead to insightsabout mechanisms of pathogenesis and opportunitiesto intervene.One of the most important questions inthe effort to understand the relationship ofJCV and PML is whether the transcriptionchanges needed to confer pathogenicity to thevirus occur in virus replicating at low rates inthe kidney or bone marrow or in virus alreadypresent in the CNS. While JCV was originallyconsidered neurotropic because it was firstisolated in the brain, it was then thought to berare or absent in the CNS except during activedisease. The evidence that JCV can be foundin the CNS in the absence of PML raises thepossibility that the transcription changes occurin the brain under some impetus related tochange in immune function rather than a viralreactivation outside of the CNS that producesPML when it crosses the BBB. 36 The effort todevelop consistent theories is challenged bysome apparently contradictory findings, suchas the identification of the same viral strainin the urine of patients without PML and thebrain of patients with PML. 37 Mutations inthe archetypal virus in patients with PML areidentified in the CSF and blood, suggestingthat mutation occurs after primary infectionwith the archetypal virus.One of the most likely transporters of JCVacross the BBB, whether the virus is in a quiescentor activated state, is B-lymphocytes.JCV-infected B-cells have been detected inthe brains of patients with PML, 38 but transmigrationacross the BBB may not alone besufficient for PML to occur, particularly if JCVhas not undergone the changes that wouldallow it to express proteins needed for cellbinding. It is possible that transmigration ofJCV into the BBB is not directly related to therisk of PML. Rather, this transmigration mayoccur in both individuals who do and whodo not develop a demyelinating disorder, indicatingthat some further step is needed forproductive infection of oligodendrocytes.A complex relationship between immunedefenses and JCV is further suggested by theinconsistent relationship between the presenceof JCV-specific antibodies and protectionagainst PML. Although the level of antibodieshas not been found to correlate withprotection against PML, 39 there is preliminaryevidence that JCV-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes(CTLs) prevent or slow PML progression.40 CD8+ lymphocytes are also beingevaluated for their ability to defend againstPML. While high numbers of CD8+ cells havebeen observed near active PML lesions, 41 immunocompetentindividuals have been foundmore likely to have a CD8+ T-cell response toS6 July 2011 • Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML

JCV exposure than those who are not immunocompetent.42 Lower viral loads in the CSFhave been correlated with better survival inHIV-infected patients with PML, 43 but characteristicsof the JCV may be equally as importantfrom the prognostic perspective. Forexample, polymorphisms in the VP1 caspidcoding region have been associated with lessvirulent PML and slower progression. 44Ultimately, it is likely that PML has beena very rare event except in individuals withAIDS because of an array of barriers that diminishthe risk. These have been groupedinto viral barriers, host barriers, and immunologicalbarriers. 45 The key viral barrier appearsto be the need for JCV to undergo a geneticrearrangement of its promoter regionto produce a transformation that will permitinfection of oligodendrocytes. Host barriers,although not yet identified, are presumedbecause overt PML is rare compared to thefrequency of JCV infection. The immunologicalbarriers include JCV-specific cytotoxic Tcells, but other types of cell-mediated immunityare suspected to be involved. 45PML occurs in a very small proportion ofindividuals at risk. The highest rate of PML,observed in patients with AIDS, is approximately4% to 5%. In contrast, the rates of PMLwith immunomodulating therapies are typicallyless than 0.01%. 4 Although PML is a seriousdisease, it is not necessarily fatal in allcases, as evidenced by an approximate 70%survival rate in natalizumab-treated PMLcases, 5 encouraging efforts to identify characteristicsof the virus and of the host defensethat may be important for improving prognosis.While assaying JCV DNA in the blood orurine of patients prior to treatment with animmunomodulating therapy to predict riskof PML does not appear to be effective, 46 thisnot only highlights the insensitivity of currentDNA detection methods, it may also suggestthat the presence of JCV is not as importantas the interrelationship of the virus to the immunedefenses. This is a logical assumptionfrom the frequency of JCV exposure in thegeneral population and the marked infrequencyof PML even in highly immunocompromisedpatients.ConclusionEstimates vary, but many experts believe thatthe majority of the human population harborsJCV. In most individuals, the virus, after a primaryinfection in childhood, resides in tissuereservoirs, replicating at very low levels. Althoughasymptomatic reactivation may occur,there appear to be no clinical consequencesin the vast majority of cases. The exceptionsinclude productive infection of oligodendrocytesand other brain cells, leading to the demyelinatingdisease PML. Prior to the AIDSepidemic, PML was exceedingly rare, and itremains rare outside of this disease. Based ona multitude of clinical observations, severalfactors must be present for PML to occur. Thefirst two are infection with mutant, pathogenicforms of JCV and an immunocompromisedstate. However, some additional factor or factorsare likely to be essential. Even in cases ofprofound immunodeficiency, such as AIDS,only a small minority of patients developPML. When associated with immunomodulatingor immunosuppressant agents, PML iseven rarer by several orders of magnitude andtypically occurs only after extended exposure.To date, the mechanisms by which latentJCV transforms into a pathogenic infection inthe CNS remain incompletely understood butmay involve both the characteristics of theJCV as well as specific processes in immuneresponse. The infrequency of PML complicatesefforts to isolate the mechanisms thatdistinguish those immunocompromised patientswho develop PML from those who donot, but there are several promising avenuesof research. The effort to isolate the specificmolecular steps is being actively investigatedfor their potential to permit those at variouslevels of risk to be detected and stratified interms of risk-benefit ratio in advance of therapyor to be treated appropriately to abort theactive PML infectious process. Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML • July 2011 S7

References1. Tan CS, Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocalleukoencephalopathy and otherdisorders caused by JC virus: clinical featuresand pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol.2010;9(4):425-437.2. Seth P, Diaz F, Major EO. Advances in thebiology of JC virus and induction of progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathy.J Neurovirol. 2003;9(2):236-246.3. Padgett BL, Walker DL, ZuRhein GM, etal. Cultivation of papova-like virus fromhuman brain with progressive multifocalleucoencephalopathy. Lancet. 1971;1(7712):1257-1260.4. Tyler KL. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy:can we reduce risk inpatients receiving biological immunomodulatorytherapies? Ann Neurol. 2010;68(3):271-274.5. Vermersch P, Kappos L, Gold R, et al. Clinicaloutcomes of natalizumab-associatedprogressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.Neurology. 2011; 76(20):1697-1704.6. Frisque RJ, Bream GL, Cannella MT. Humanpolyomavirus JC virus genome. JVirol. 1984;51(2):458-469.7. Padgett BL, Walker DL. Prevalence of antibodiesin human sera against JC virus, anisolate from a case of progressive multifocalleukoencephalopathy. J Infect Dis.1973;127(4):467-470.8. Matos A, Duque V, Beato S, et al. Characterizationof JC human polyomavirus infectionin a Portuguese population. J MedVirol. 2010;82(3):494-504.9. Kunitake T, Kitamura T, Guo J, et al. Parent-to-childtransmission is relativelycommon in the spread of the humanpolyomavirus JC virus. J Clin Microbiol.1995;33(6):1448-1451.10. Boothpur R, Brennan DC. Human polyomaviruses and disease with emphasison clinical BK and JC. J Clin Virol.2010;47(4):306-312.11. Monaco MC, Jensen PN, Hou J, et al. Detectionof JC virus DNA in human tonsiltissue: evidence for site of initial viral infection.J Virol. 1998;72(12):9918-9923.12. Tan CS, Ellis LC, Wüthrich C, et al. JC viruslatency in the brain and extraneural organsof patients with and without progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathy.J Virol. 2010;84(18):9200-9209.13. Komagome R, Sawa H, Suzuki T, et al. Oligosaccharidesas receptors for JC virus. JVirol. 2002;76(24):12992-13000.14. Elphick GF, Querbes W, Jordan JA, et al.The human polyomavirus, JCV, uses serotoninreceptors to infect cells. Science.2004;306(5700):1380-1383.15. Pho MT, Ashok A, Atwood WJ. JC virusenters human glial cells by clathrin-dependentreceptor-mediated endocytosis.J Virol. 2000;74(5):2288-2292.16. Shackelton LA, Rambaut A, Pybus OG,Holmes EC. JC virus evolution and its associationwith human populations. J Virol.2006;80(20):9928-9933.17. Dubois V, Moret H, Lafon ME, et al. JCvirus genotypes in France: molecularepidemiology and potential significancefor progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.J Infect Dis. 2001;183(2):213-217.18. Pfister LA, Letvin NL, Koralnik IJ. JC virusregulatory region tandem repeats inplasma and central nervous system isolatescorrelate with poor clinical outcomein patients with progressive multifocalleukoencephalopathy. J Virol. 2001;75(12):5672-5676.19. Agostini HT, Ryschkewitsch CF, Singer EJ,Stoner GL. JC virus regulatory region rearrangementsand genotypes in progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathy:two independent aspects of virus variation.J Gen Virol. 1997;78(Pt 3):659-664.20. Gasparovic ML, Gee GV, Atwood WJ. JCvirus minor capsid proteins Vp2 and Vp3are essential for virus propagation. J Virol.2006;80(21):10858-10861.21. Frisque RJ. Structure and function ofJC virus T’ proteins. J Neurovirol. 2001;7(4):293-297.22. Sugimoto C, Hasegawa M, Kato A, et al.Evolution of human Polyomavirus JC:implications for the population history ofhumans. J Mol Evol. 2002;54(3):285-297.23. Behzad-Behbahani A, Klapper PE, VallelyPJ, et al. Detection of BK virus andJC virus DNA in urine samples from immunocompromised(HIV-infected) andimmunocompetent (HIV-non-infected)patients using polymerase chain reactionand microplate hybridisation. J Clin Virol.2004;29(4):224-229.24. Weber T, Major EO. Progressive multifocalleukoencephalopathy: molecular biology,pathogenesis and clinical impact.Intervirology. 1997;40(2-3):98-111.25. Gheuens S, Pierone G, Peeters P, KoralnikIJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathyin individuals with minimal oroccult immunosuppression. J Neurol NeurosurgPsychiatry. 2010;81(3):247-254.26. Gillespie SM, Chang Y, Lemp G, et al. Progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathyin persons infected with human immunodeficiencyvirus, San Francisco, 1981-1989. Ann Neurol. 1991;30(4):597-604.27. Dubois V, Moret H, Lafon ME, et al. Prevalenceof JC virus viraemia in HIV-infectedpatients with or without neurological disorders:a prospective study. J Neurovirol.1998;4(5):539-544.28. Okada Y, Endo S, Takahashi H, et al. Distributionand function of JCV agnoprotein.J Neurovirol. 2001;7(4):302-306.29. Hamilton RS, Gravell M, Major EO. Comparisonof antibody titers determined byhemagglutination inhibition and enzymeimmunoassay for JC virus and BK virus. JClin Microbiol. 2000;38(1):105-109.30. Landry ML, Eid T, Bannykh S, Major E.False negative PCR despite high levelsof JC virus DNA in spinal fluid: implicationsfor diagnostic testing. J Clin Virol.2008;43(2):247-249.31. Garcia De Viedma D, Diaz Infantes M, MirallesP, et al. JC virus load in progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathy: analysisof the correlation between the viral burdenin cerebrospinal fluid, patient survival,and the volume of neurological lesions.Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(12):1568-1575.32. Cinque P, Koralnik IJ, Clifford DB. Theevolving face of human immunodeficiencyvirus-related progressive multifocalleukoencephalopathy: defininga consensus terminology. J Neurovirol.2003;9(Suppl 1):88-92.33. Gorelik L, Reid C, Testa M, et al. Progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathy(PML) development is associated withmutations in JC virus capsid proteinVP1 that change its receptor. J Infect Dis.2011;204(1):103-114.34. Monaco MC, Sabath BF, Durham LC, MajorEO. JC virus multiplication in humanhematopoietic progenitor cells requiresthe NF-1 class D transcription factor. J Virol.2001;75(20):9687-9695.35. Jensen PN, Major EO. A classificationscheme for human polyomavirus JCVvariants based on the nucleotide sequenceof the noncoding regulatory region.J Neurovirol. 2001;7(4):280-287.36. Sabath BF, Major EO. Traffic of JC virusfrom sites of initial infection to thebrain: the path to progressive multifocalleukoencephalopathy. J Infect Dis.2002;186(Suppl 2):S180-S186.37. Myers C, Frisque RJ, Arthur RR. Directisolation and characterization of JC virusfrom urine samples of renal andbone marrow transplant patients. J Virol.1989;63(10):4445-4449.38. Chapagain ML, Nerurkar VR. Human polyomavirusJC (JCV) infection of human Blymphocytes: a possible mechanism forJCV transmigration across the blood-brainbarrier. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(2):184-191.S8 July 2011 • Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML

39. Weber F, Goldmann C, Krämer M, et al.Cellular and humoral immune responsein progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.Ann Neurol. 2001;49(5):636-642.40. Du Pasquier RA, Kuroda MJ, Schmitz JE,et al. Low frequency of cytotoxic T lymphocytesagainst the novel HLA-A*0201-restricted JC virus epitope VP1(p36) inpatients with proven or possible progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathy.J Virol. 2003;77(22):11918-11926.41. Wüthrich C, Kesari S, Kim WK, et al. Characterizationof lymphocytic infiltrates inprogressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy:co-localization of CD8(+) T cellswith JCV-infected glial cells. J Neurovirol.2006;12(2):116-128.42. Du Pasquier RA, Schmitz JE, Jean-JacquesJ, et al. Detection of JC virus-specific cytotoxicT lymphocytes in healthy individuals.J Virol. 2004;78(18):10206-10210.43. De Luca A, Giancola ML, Ammassari A,et al. The effect of potent antiretroviraltherapy and JC virus load in cerebrospinalfluid on clinical outcome of patientswith AIDS-associated progressive multifocalleukoencephalopathy. J Infect Dis.2000;182(4):1077-1083.44. Delbue S, Branchetti E, Bertolacci S, etal. JC virus VP1 loop-specific polymorphismsare associated with favorableprognosis for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.J Neurovirol. 2009;15(1):51-56.45. Berger JR. The basis for modeling progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathypathogenesis. Curr Opin Neurol.2011;24(3):262-267.46. Rudick RA, O’Connor PW, Polman CH, etal. Assessment of JC virus DNA in bloodand urine from natalizumab-treated patients.Ann Neurol. 2010;68(3):304-310.Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML • July 2011 S9

The Epidemiologyof Progressive MultifocalLeukoencephalopathyJohn F. Foley, <strong>MD</strong>Rocky Mountain Multiple SclerosisClinic, Salt Lake City, Utah.IntroductionProgressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML)is a rare disease that is generated by a change in therelationship between the human host and residentJC virus (JCV). Prior to the epidemic of acquiredimmunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), fewer than250 cases had been reported worldwide. 1 Otherthan AIDS, in which 3% to 5% of individuals developPML, 2 this disease has been an unusual complicationof myeloproliferative or lymphoproliferativedisorders and immunosuppressant therapiesadministered to control autoimmune diseases ormalignancies. 3 However, the now well-documentedpotential for treatment-related PML that hasoccurred during use of the novel biologically activeselective therapeutics has intensified efforts toidentify the molecular steps as well as the risk factorsthat permit the transition from benign (archetypal)JCV infection to neurotrophic JCV infectionof the central nervous system (CNS). In addition toJCV seropositivity, at least two other factors appearto define risk. These are altered immune functionand extended exposure to the immunomodulatingagent. Detailed epidemiology of PML may be usefulto the effort to isolate factors that render individualssusceptible to PML. It may also aid calculationsof the risk of PML in relation to expected benefitsfrom immunomodulating agents.Dr. Foley has received consulting fees from Biogen Idec,Genzyme, and Teva and has received honoraria fromBiogen Idec and Teva.JCV and PML: History andEarly Epidemiology StudiesPML, first described in the late 1950s in threepatients with hematologic malignancies, is a demyelinatingdisorder of the white matter characterizedby lytic infection of cells in the CNS, par-S10 July 2011 • Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML

diseases, which represent an autoimmune inflammatoryprocess, PML may be a direct resultof immune dysfunction but is more likelyto be an indirect consequence of the therapiesthat exert their therapeutic effect by immunosuppressionor by immunomodulation.Treatment duration as well as priorimmunosuppressant exposure have clearlyemerged as important factors in riskstratification.JCV and ImmunomodulatingTherapiesNumerous biologically active therapies havebeen associated with risk of PML. These includebut are not limited to rituximab, natalizumab,infliximab, efalizumab, and tacrolimus. 9 Whilemost of the reported cases of PML associatedwith these therapies have accrued since 2003,it is possible, if not likely, that sporadic earliercases went unrecognized or undiagnosed. Thespecific mechanisms of treatment-related PMLmay vary, but the immunomodulating propertiesof these agents, particularly the changesthey exert on lymphocyte trafficking, are consideredto be a common feature. 10 However, theinfrequency of PML with all of the agents so farimplicated suggests that there are both multipleand complex molecular steps required forthe archetypal JCV to produce PML. Patientspecificsusceptibilities are a focus of intensiveongoing investigation.Early reports of treatment-related PMLincluded use of rituximab in cancer patientsand infliximab in patients with an inflammatorydisease. 11,12 More attention was directed totreatment-related PML when a series of caseswere associated with the anti-inflammatorybiological agents natalizumab, 13 which inhibitsthe cellular adhesion molecular alpha4-integrin,and efalizumab, 9 which exerts its antiinflammatoryeffect by binding to the CD11asubunit of lymphocyte-associated antigen 1.Although there were only a small number ofcases associated with each of these agents, theseries of these unexpected complications overa relatively short period intensified the effort toquantify the risks for this complication.The unadjusted risk of PML with all of theimmunomodulating agents linked to this disorderhas remained very low. By exposure, theincidence of PML on rituximab is an estimated1 per 100,000 when this agent has been usedfor the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and1 per 5000 patients when used for the treatmentof systemic lupus erythematosus. 6 Fornatalizumab and efalizumab, the risk is alsolow but has been related to treatment duration.Although experience with efalizumab remainslimited, all four cases (three documented andone suspected) occurred in patients who weretaking efalizumab continuously for at leastthree years. 14 The overall incidence of PML innatalizumab-treated patients as of June 1, 2011,is 1.51/1000, with the highest risk occurring between25 to 36 infusions. 15Following the evidence that PML was apossible complication of natalizumab, thisagent was briefly voluntarily withdrawn fromthe market until further analysis of this uncommonand unexpected complicatingproblem. Based on the low rates ofPML and the well-documented benefitsof natalizumab in multiple sclerosis(MS), it was reintroduced in June2006 and is currently available onlythrough the Tysabri Outreach: UnifiedCommitment to Health (TOUCH) prescribingprogram. Since that time, additional cases ofPML have been reported, but the pattern of riskhas remained relatively stable.Treatment duration as well as prior immunosuppressantexposure have clearly emergedas important factors in risk stratification. Thereare likely to be numerous other factors that alsoinfluence risk of PML in patients taking biologicallyactive agents of this nature. Most apparentis the underlying presence of resident JCVinfection. Infection site and potential geneticmutational characteristics of the viral capsidmay well play a role as well. A two-stage ELISAassay has been developed for JCV and will likelybecome a standard annual assessment onceit is commercialized. Moreover, although thepresence of JCV is necessary, biologically ac-S12 July 2011 • Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML

tive therapies appear to exert some change onthe relationship between the virus and the CNSbut impose little or no direct effect on the replicationrate of the pathogen. Although one smallstudy did associate natalizumab with reactivationof JCV, a much larger study was unable todemonstrate any change in JCV-DNA positiveurine specimens after 48 weeks of natalizumabtreatment. 6 In a series of five patients who diddevelop PML, there was no change in JCV DNAlevels prior to disease onset.There are at least 14 currently availablegenotypes, which are determined by the codingregion of JCV. 8 While genotypes have notbeen well matched with virulence, changes inthe hypervariable regulatory region do appearto control the transformation from an archetypelatent JCV to an opportunistic neurotropicinfection with propensity for PML. 5 However,the transformation from the archetype formof the virus to the PML-capable infection doesnot appear to be fully explained by alterationsin the biology of the virus. 16 Rather, in aseries of experiments conducted in the presenceof the JC virus T antigen, the replicationand transcription functions were remarkablysimilar between the archetype and virulentstrains, producing the hypothesis that archetypestrains do not have to convert to PML-typestrains to infect cells in the CNS. This suggeststhat the conversion to the virulent form may, inat least some cases, take place after JCV infectscells in the CNS.The site of the latent JCV infection may alsobe relevant to risk of PML. Low levels of replicationin the bone marrow or lymph tissue, forexample, may pose a much greater risk that thevirus will reach the CNS than latent infection inrenal tissue, particularly when immunomodulatingtherapies alter lymphocyte function. Inone study, JCV virus could be detected in thebone marrow of about twice as many patientswith PML, whether associated with AIDS oranother etiology, than those without PML. 17Although the ability of JCV to reside in the CNSin a latent state is controversial, the potentialfor CNS latency to serve as a risk factor for PMLdeserves further evaluation. If CNS latency isan uncommon but necessary event, this mayexplain the infrequency with which PML isa treatment-related complication. However,autopsy studies suggest that JCV is capable ofcrossing the BBB without producing a demyelinatingdisease, 18 which, again, supports thelikelihood that the presence of JCV in the CNSalone is not a sufficient reason by itself for PMLto occur.One theory is that cell susceptibility to JCVinternalization is required independent of thepresence of receptors known to be used bythis virus for attachment. The nuclear factor-1(NF-1) class X protein, for example, has beenfound at higher levels in JCV-susceptible cellsthan nonpermissive cells, leading to speculationthat expression of this receptor, or additionalreceptors, such as c-Jun, are necessaryfor virus to infect cells critical to PML disease. 19While it has been proposed that activation ofB-lymphocytes by immunomodulating therapies,such as rituximab or natalizumab, play acritical role in transporting JCV across the BBB,this, again, may be one of several molecularevents that must occur for PML to develop.The many unresolved issues complicatethe effort to isolate the steps that permit benign,archetypal JCV to mount a productiveand virulent infection of the CNS. Followinga report of rituximab-related PML, monitoringof blood for JCV and BK virus, anotherpolyomavirus, was performed in 73 consecutivepatients who received rituximab as partof a therapeutic regimen following solid organtransplantation. 20 Over a median 13 months offollow-up, JCV was detected with polymerasechain reaction (PCR) in the blood of four patients(5.5%). Loss of cell-mediated immunityappeared to correspond with JCV detection,but JCV could not be detected in the blood ofany of the four individuals with subsequentmonitoring. None developed PML or any clinicalevidence of neurologic disease. In contrast,all 73 patients developed BK-associated nephropathy,prompting a reduction in the immunosuppressionregimen.In patients who already have PML, an evaluationof the cell-mediated immune responsesuggests that CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes(CTLs) may play a critical role in the early con-Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML • July 2011 S13

tainment of JCV in the CNS as well as influencethe clinical outcome. 21 In a study exploringthis hypothesis, autopsy samples from 26AIDS-related and 20 non–AIDS-related casesof PML were evaluated. In the tissue samples,the predominant inflammatory cells wereCD8+ T-lymphocytes, which were closely associatedwith JCV-infected glial cells. The authorsspeculated that these cell populations could becrucial to the immunosurveillance that determinesrisk and the extent of a productive JCVinfection in the CNS, providing a potentiallyuseful target for understanding relative risksand determining targets of therapy.JCV is characterized as an opportunisticinfection because of its ability under specificcircumstances to transform from a benignresident microbe to a productive pathogen,but there may be variability in the molecularevents leading to PML in individuals withAIDS relative to individuals who develop PMLas a complication of an immunomodulatingtherapy. 22 For example, the viral load of JCVin the CNS has been identified as a predictorof survival in AIDS-related PML, but severeimmune deficiency in these patients may differfrom the alterations in immune functioncurrently suspected of mediating risk of PMLamong those taking an immunomodulatorytherapy. While antiretroviral therapies havebeen associated with a reduction in the JCVviral load in the CNS and an improvement insurvival, 23 the strategy for preventing PML orcontrolling JCV after the demyelinating diseasehas developed is likely to be different inpatients whose underlying risk has been dueto persistent exposure to an immunomodulatingtherapy.Survival and Risk StratificationPML is not necessarily a fatal disease, despitetraditional dogma. The high rates of fatalityduring the AIDS epidemic before the introductionof effective antiretroviral rates were observedirrespective of PML. In the current era,slightly more than half of AIDS patients whodevelop PML are alive at one year, and the raterises to nearly 60% in patients with PML withanother etiology, such as exposure to an immunomodulatingtherapy. 24 In patients with AIDS,an immune reconstitution inflammation syndrome(IRIS) was associated with a lower rateof survival at one year (53% vs 65%), althoughthis difference did not reach statistical significance.A low CD4+ count was also a risk factorfor PML-related mortality in AIDS patients, althoughthe presence of JCV-specific CTLs wasassociated with a trend for improved survival.Other data support the role of JCV-specificCTLs as predictors of survival in PML. In astudy employing a highly sensitive assay for detectingthe cellular immune response to JCV inpatients with PML, JCV-specific CTLs seemedto limit progression of brain lesions. 25 The authorssuggested that the same mechanism mayprevent PML altogether in many patients bymechanisms analogous to control of cytomegalovirus(CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).One of the likely mechanisms of CTLs in regardto survival among those who develop PML isa reduction in viral production and CNS damage.In one series of 12 patients with PML thatdemonstrated a wide variation in the JCV viralload, greater JCV burden could not be associatedwith the magnitude of neurological damage,but higher viral loads did correlate with shortersurvival time. 26Several strategies are being pursued forPML risk stratification and for predicting diseasecourse in those who develop PML. In astudy that sequenced the genomic coding regionsof the VP1-associated–specific polymorphicresidues at specific positions of the outerloop, some appear to be associated with a morefavorable prognosis. 27 As the external loopsare thought to provide the principal antigenicstructures as well as receptor-binding sites anddomains responsible for hemagglutination,these regions may be valuable for identifyingJCV with a low propensity for CNS infection aswell as a more benign course of PML. Goreliket al 28 found VP1 mutations in CSF and bloodsamples isolated from PML patients, but noturine samples, suggesting that mutations occurafter infection with archetype virus.Due to a far larger sample size, more dataare available regarding predictors of survivaland potential therapies in AIDS-related PML.S14 July 2011 • Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML

10. Chapagain ML, Nerurkar VR. Humanpolyomavirus JC (JCV) infection of humanB lymphocytes: a possible mechanismfor JCV transmigration acrossthe blood-brain barrier. J Infect Dis.2010;202(2):184-191.11. Goldberg SL, Pecora AL, Alter RS, et al.Unusual viral infections (progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathy and cytomegalovirusdisease) after high-dosechemotherapy with autologous bloodstem cell rescue and peritransplantationrituximab. Blood. 2002;99(4):1486-1488.12. Imperato AK, Bingham CO 3rd, AbramsonSB. Overview of benefit/risk of biologicalagents. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22(5Suppl 35):S108-S114.13. Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL.Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathycomplicating treatment withnatalizumab and interferon beta-1afor multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med.2005;353(4):369-374.14. Seminara NM, Gelfand JM. Assessinglong-term drug safety: lessons (re)learned from raptiva. Semin Cutan MedSurg. 2010;29(1):16-19.15. Data on file. Tysabri safety update.Weston, MA: Biogen Idec; June 2011.16. Sock E, Renner K, Feist D, et al. Functionalcomparison of PML-type andarchetype strains of JC virus. J Virol.1996;70(3):1512-1520.17. Tan CS, Dezube BJ, Bhargava P, et al. Detectionof JC virus DNA and proteins inthe bone marrow of HIV-positive andHIV-negative patients: implications forviral latency and neurotropic transformation.J Infect Dis. 2009;199(6):881-888.18. White FA 3rd, Ishaq M, Stoner GL, FrisqueRJ. JC virus DNA is present in many humanbrain samples from patients withoutprogressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.J Virol. 1992;66(10):5726-5734.19. Sabath BF, Major EO. Traffic of JC virusfrom sites of initial infection to thebrain: the path to progressive multifocalleukoencephalopathy. J Infect Dis.2002;186(Suppl 2):S180-S186.20. Kamar N, Mengelle C, Rostaing L. Incidenceof JC-virus replication after rituximabtherapy in solid-organ transplantpatients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(1):244-245.21. Wüthrich C, Kesari S, Kim WK, et al. Characterizationof lymphocytic infiltrates inprogressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy:co-localization of CD8(+) T cellswith JCV-infected glial cells. J Neurovirol.2006;12(2):116-128.22. Taoufik Y, Gasnault J, Karaterki A, et al.Prognostic value of JC virus load in cerebrospinalfluid of patients with progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathy. JInfect Dis. 1998;178(6):1816-1820.23. De Luca A, Giancola ML, Ammassari A,et al. The effect of potent antiretroviraltherapy and JC virus load in cerebrospinalfluid on clinical outcome of patientswith AIDS-associated progressive multifocalleukoencephalopathy. J Infect Dis.2000;182(4):1077-1083.24. Marzocchetti A, Tompkins T, Clifford DB,et al. Determinants of survival in progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathy.Neurology. 2009;73(19):1551-1558.25. Du Pasquier RA, Schmitz JE, Jean-JacquesJ, et al. Detection of JC virus-specific cytotoxicT lymphocytes in healthy individuals.J Virol. 2004;78(18):10206-10210.26. Garcia De Viedma D, Diaz Infantes M,Miralles P, et al. JC virus load in progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathy:analysis of the correlation betweenthe viral burden in cerebrospinal fluid,patient survival, and the volume ofneurological lesions. Clin Infect Dis.2002;34(12):1568-1575.27. Delbue S, Branchetti E, Bertolacci S, etal. JC virus VP1 loop-specific polymorphismsare associated with favorableprognosis for progressive multifocalleukoencephalopathy. J Neurovirol. 2009;15(1):51-56.28. Gorelik L, Reid C, Testa M, et al. Progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathy(PML) development is associated withmutations in JC virus capsid protein VP1that change its receptor specificity. J InfectDis. 2011;204(1):103-114.29. Bossolasco S, Calori G, Moretti F, et al.Prognostic significance of JC virus DNAlevels in cerebrospinal fluid of patientswith HIV-associated progressive multifocalleukoencephalopathy. Clin Infect Dis.2005;40(5):738-744.30. Gasnault J, Kousignian P, Kahraman M, etal. Cidofovir in AIDS-associated progressivemultifocal leukoencephalopathy: amonocenter observational study withclinical and JC virus load monitoring. JNeurovirol. 2001;7(4):375-381.31. Gorelik L, Lerner M, Bixler S, et al. Anti-JC virus antibodies: implications forPML risk stratification. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(3):295-303.S16 July 2011 • Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML

Progressive MultifocalLeukoencephalopathy:Survival StatisticsMoti L. Chapagain, PhDAssistant Researcher, Department ofTropical Medicine, Medical Microbiologyand Pharmacology, John A. Burns Schoolof Medicine, Honolulu, Hawaii.Dr. Chapagain has no conflicts of interest to disclose.IntroductionFrom a newly emergent, rare, and mysterious illnesspredominantly affecting patients with underlyinglymphoproliferative disorders or hematologicalmalignancies in the 1950s, 1,2 progressive multifocalleukoencephalopathy (PML) has evolved into oneof the most frequent conditions associated withacquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). 3,4Moreover, PML has recently emerged as a lifethreateningcomplication among individuals onimmunomodulatory monoclonal antibody therapyand dramatically impacted their utilization. 5-7While PML has been regarded by most observers asboth a rare and fatal disease, 8 recent occurances ofPML among individuals with monoclonal antibodytherapies expanded the epidemiological reach ofthe disease and widened concerns. However, thesemore recent manifestations of PML have also ledto important advances in detection and treatment.Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviraltherapy (HAART)/combination antiretroviraltherapy (cART) stemming from the AIDS epidemicthat began in the 1980s, HIV-positive patients withPML are living longer and enabling researchersand clinicians to better understand the disease. 8,9The development of an immune reconstitutioninflammatory syndrome (IRIS) as well as PML associatedwith monoclonal antibodies used in thetreatment of such disorders as multiple sclerosis(MS) has also contributed to improved descriptionof the characteristics of PML as well as advances inmanagement of the disease. 8 Indeed, survival ratesfrom recent series provide evidence in support ofreclassifying PML from a fatal disease to a chronicdisease. 9-11Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML • July 2011 S17

TABLE 1 Common clinical features of AIDS-associated PML patients*Clinical features Berenguer et al 32 (2003) Falcó et al 34 (2008) Engsig et al 26 (2009)Cognitive deficits NR NR 27 (57%)Limb weaknesses 82 (69.5) 26 (42.6) 20 (43%)Gait/coordination disorders 76 (64.4) 33 (54.1) 32 (68%)Speech disorders 55 (46.6) 25 (41.0) 20 (43%)Visual impairments 24 (20.3) 16 (26.2) 13 (28%)Seizures 15 (12.7) NR 6 (13%)Cranial nerve palsies 37 (31.4) NR 3 (6%)Sensory affections NR NR 8 (17%)Altered mental status NR 19 (31.1) NRTotal PML cases 118 (100) 61 (100) 47 (100)* Number (percentage) of PML cases. NR = Not rated.PML is a disease of the brain and centralnervous system (CNS) characterized by multifocaldemyelination resulting from lytic infectionof oligodendrocytes by human polyomavirusJC (JCV), 12 a ubiquitous DNA virus namedafter the patient from whom it was first isolated(John Cunningham). 2,8,13 A neurotropic virusthat infects only human beings, JCV is foundin more than 50% of the human populationby adulthood. 8,14 Despite up to 91% of peoplein some smaller, localized population studieshaving detectable serum antibodies againstJCV, PML had remained a relatively rare disease.15 Between 1958 and 1984, only 230 caseswere identified in one comprehensive review. 14During the HIV epidemic, however, the prevalenceincreased significantly, with up to 5% ofAIDS patients developing PML. 8 Mortality associatedwith PML also rose—from 1.5 deathsper 10 million individuals in 1979, before thestart of the epidemic, to 6.1 deaths per 10 millionindividuals in 1987. As a demyelinatingdisorder, PML belongs to the class of opportunisticinfections and occurs predominantly inpatients with severe immunosuppression. 2,13Common presenting symptoms of HIV/AIDSassociatedPML include cognitive deficits, gaitdisorders, limb weaknesses, speech disorders,and visual impairments (Table 1). The naturalcourse of the disease historically is progressive,typically leading to death within months whenthe patient remains immunocompromised. 2In a comprehensive review of clinical featuresand pathogenesis, Tan and Koralnik 8 categorizedPML into three main forms (Table 2):(1) classic PML, which usually affects patientswith severe cellular immunosuppression, includingthose with HIV/AIDS, hematologicalmalignancies, chronic inflammatory disorders,or organ transplant recipients; (2) PMLassociated with the use of therapeutic monoclonalantibodies; and (3) PML-IRIS, which istriggered by a rapid global recovery of the immunesystem after the initiation of cART in patientswith HIV/AIDS or subsequent to discontinuationof immunosuppressive treatment inHIV-negative patients.Although several classes of drugs used tosuppress the host cellular immune responsehave been implicated, monoclonal antibodieshave emerged in recent years as a new categoryof drugs associated with PML. These immunomodulatorydrugs are not broad-spectrum immunesuppressors, but they selectively modulateone or more aspects of the immune systemand have been used in the treatment of autoimmunediseases, including at least four conditionsthat had not been previously implicatedin the risk stratification for PML—MS, Crohn’sdisease, psoriasis, and lupus. Among theS18 July 2011 • Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML

TABLE 2 Different forms of PMLClassic PMLPML associated withmonoclonal antibodies 10PML-IRISOnset Subacute Subacute Immune-recoveryPatientscharacteristicsNeurologicsymptomsMRIDiagnosisSevere immune compromisedeither because of HIV,lymphoproliferative disorders,organ transplant recipients,or on immune-suppressivetherapyBased on location;neurobehavioral, motor,language, visual symptoms,cognitive impairment, seizure;no optic nerve or spinal cordinvolvementAsymmetric, well demarcated,contrast non-enhancingsubcortical white matterlesions, hyperintense in T2and FLAIR, hypointense in T1Suggestive symptoms, JCVdetection in CSF or brainbiopsy, MRIGenerally immune-competentindividuals with autoimmunedisease taking one of immunemodulatingantibodiesSimilar to classic PMLContrast enhancement (43%)may be present, particularly afterdiscontinuation of treatmentAny new neurologic symptomsor signs in patients with monoclonalantibody warrants carefulevaluation, JCV detection inCSF or brain biopsy, MRIHIV+ patients: after initiationof cART; after discontinuationof natalizumabor plasma exchange innatalizumab-associatedPML in MS patientsSimilar to classic PML,appearance of new neurologicsymptoms or rapiddeterioration may occurContrast enhancementand mass effectSuggestive symptoms,JCV detection in CSF orbrain biopsy, MRIHistologyDemyelinating lesions oftenat grey/white junction, JCV inenlarged oligodendrocytes,bizarre astrocytesDemyelination similar to classicPML, with addition of inflammatoryinfiltratesDemyelination similar toclassic PML, with additionof inflammatory infiltratesTreatmentcART for HIV-positivepatients; discontinuation ofimmune-suppressive treatmentfor HIV-negative patientsDiscontinue or decrease immunomodulatingdrugs, plasmaexchange or immunoabsorptionfor natalizumab-treated patients,high-dose corticosteroidsConsider steroids in caseswith notable neurologicworsening or signs ofimpending brainherniationPML = Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy; cART = combination antiretroviral therapy; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging,FLAIR = fluid attenuated inversion recovery. (Adapted from Tan CS, Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathyand other disorders caused by JC virus: clinical features and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(4):425-437.)monoclonal antibodies associated with PMLare natalizumab, which is indicated for MS andCrohn’s disease; rituximab, used to treat lupus;and efalizumab, which had been indicated forthe treatment of moderate to severe plaquepsoriasis before being permanently withdrawnfrom the market in April 2009 following diagnosisof PML in three patients receiving thedrug. While the exact mechanism of PML developmentin individuals taking these monoclonalantibodies is debatable, these monoclonalantibodies have been suggested by some tofacilitate JCV reactivation and disseminationor create artificial immune deficiency status inthe CNS (Table 3). Since hematopoietic precursorcells are susceptible to JCV infection, 16 andnatalizumab and efalizumab facilitate releaseof hematopoietic precursor CD34+ cells intoClinical Reviews of JCV and PML • July 2011 S19

TABLE 3 Summary of agents predisposing to PMLAgents Mechanisms of action Possible explanation forincreased risk of PMLNatalizumabα4β1 and α4β7 integrinantibodies↓ JCV-specific CTLs traffickinginto CNS; ↓ CNSperivascular dendritic cellsfor antigen processing; ?↑neurotrophic JCV expressionEstimatedrisk of PML1.51:1,000patientstreated*Unique predispositionfor PML aYesEfalizumab Anti CD11a antibody Blockade of co-stimulatorymolecules on T-cells; ↓ JCVspecificCTLs trafficking intoCNSRituximab Anti CD20 antibody ↑ JCV expression with recoveryof B-cell population;↓ B-cell antigen presentation1:500 6 Yes1:25,000** NoPML = Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy; CTLs = cytotoxic T-lymphocytes; ↓ = decreasing; ↑ = increasing; ?↑=possiblyincreasing; a = risk of development of PML with the drug in the absence of underlying disorders that increase its risk. (Adaptedfrom Berger JR. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and newer biological agents. Drug Saf. 2010;33:969-83.)* Data on file. Tysabri safety update. Weston, MA: Biogen Idec; June 2011. ** Data extracted from Clifford DB, Ances B, Costello C,et al. Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol. 2022 (in press).blood circulation, 14,17 it is plausible to thinkthat immature JCV-infected leukocytes maybe released from the bone marrow after thesemonoclonal antibody treatments, inducingviremia. 18 Indeed, a small (n = 19) study demonstratedthe increased prevalence of JCV inurine, plasma, and peripheral-blood mononuclearcells (PBMCs) after the initiation of natalizumabtreatment among MS patients. 19 However,a larger (n = 1397) study by Rudick andcolleagues 20 failed to confirm these findings,and another study did not detect JCV DNA inthe PBMCs and CD34+ hematopoietic precursorcells in natalizumab-treated patients, arguingagainst the JCV infection of CD34+ cells andits mobilization as possible explanation of PMLdevelopment after natalizumab treatment. 17Natalizumab binds with adhesion moleculesα4β1 and α4β7 integrins, 21 whereas efalizumabbinds to the alpha chain (CD11a) of the leukocytefunction–associated antigen (LFA-1), 22 inhibitsthe migration of lymphocytes across theblood-brain barrier (BBB), and may possiblycreate compartmentalized cell-mediated immunedeficiency in the CNS, facilitating localJCV reactivation and PML development.Rituximab, which was first approved bythe US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)in 1997, was found to be associated with PML.As of 2009, 57 HIV-negative patients who weretreated with rituximab and other agents developedPML. 23 Fifty-five of these PML patientshad lymphoid malignancies, while only twohad lupus and one each had rheumatoid arthritis,idiopathic autoimmune pancytopenia,or immune thrombocytopenia purpura. However,most of these patients were treated withseveral other classes of immunosuppressiveagents, and the exact role of rituximab in PMLdevelopment is unclear. 8 Rituximab binds withCD 20 expressed on B-lymphocytes and depletestheir population in the blood 23 and alsopossibly releases the JCV-infected immatureB-lymphocytes.DiagnosisSince the clinical features of PML vary accordingto the localization of the demyelinating lesionsand are nonspecific, diagnosis of PMLrequires strong clinical vigor supported bylaboratory tests. Methods for diagnosing PMLinclude polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detectionof JCV DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid(CSF) and detection of viral DNA or proteinsby in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistryon a brain biopsy sample. 8 In addition,S20 July 2011 • Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML

characteristic brain changes on magnetic resonanceimaging (MRI) are useful. 24 PCR detectionof JCV in CSF has been a gold standard forconfirming PML diagnosis; however, becauseof cART its sensitivity in AIDS-associated PMLmay be low, ranging from 42% to 81%. 25-27 Whilethe PCR method is also useful in diagnosingmonoclonal antibodies- and IRIS-associatedPML, PCR may fail to detect low JCV in CSF ofthese individuals because JCV replication maybe held by a competent immune system in theformer and recovering immune system in thelatter, and a brain biopsy may be necessitated. 8Since only a small fraction of monoclonalantibody–treated individuals are likely todevelop PML, which can lead to long-termneurological sequelae or death, stratifying patientsaccording to risk of PML development isof paramount importance. Indeed, a series ofrecent studies have determined three factorsthat are useful in stratifying monoclonal antibody-treatedMS patients according to theirrisk of PML development. These factors areanti-JCV antibody–positive status, prior immunosuppressantuse, and natalizumab treatmentduration.In a recent editorial, Tyler 5 raised the questionof whether risk can be reduced in patientsreceiving biological immunomodulatorytherapies. “The ability to stratify risk moreaccurately in specific subpopulations wouldobviously be of tremendous utility in guidingtherapeutic decisions,” he wrote. “Diseaseprevention and risk reduction are even morecritical because of the absence of any specificantiviral therapy of proven benefit in the treatmentof PML.”Even though no subjects in their study developedPML, Chen and colleagues 19 suggestedthat surveillance of blood or urine may be usefulin identifying patients potentially at risk ofdeveloping PML after natalizumab treatment.However, a larger prospective study by Rudickand colleagues 20 testing for JCV DNA using acommercially available quantitative PCR assayas well as a more sensitive quantitative PCRassay developed at the National Institutes ofHealth found no difference in the prevalenceof JCV DNA–positive plasma in placebo-treatedor natalizumab-treated patients, nor in theprevalence of similarly positive urine specimensat baseline and at 48 weeks. Furthermore,JCV DNA was not detected prior to diseaseonset in the blood of the five patients whodeveloped PML during the study. Rudick et al 20concluded that “measuring JCV DNA in bloodor urine with currently available methods isunlikely to be useful for predicting PML riskin natalizumab-treated MS patients,” a findingwith which Tyler concurred. 5Pointing to detection of virus-specific antibodiesas the traditional method for establishingpast exposure to viral infection, Tyler 5went on to observe that “A highly sensitive andspecific JCV antibody assay would theoreticallyenable the population to be divided intothose at risk for developing PML (antibodypositive), and those not at risk (antibody negative).”While early studies of JCV serostatus indicatedthat the primary infection happenedin infancy and childhood and that, by adulthood,sero prevalence rates as high as 80%were reported, these findings may have beenconfounded by use of a nonspecific hemagglutination-inhibitionassay, a less accurate butwidely available assay method of that time, aswell as by potential antibody cross-reactivitybetween antibodies against JCV and other humanpolyomaviruses.Two recent studies of note have useddifferent forms of enzyme-linked immunosorbentassay (ELISA) techniques. 7,28 In anevaluation of MS patients treated with natalizumabusing a two-step ELISA to detect antibodiesto the JCV-like particles, Gorelik andcolleagues 28 demonstrated that 100% (17 outof 17) of sera from natalizumab-associatedPML patients obtained 16 to 180 months priorto PML development were JCV-seropositive,whereas only 53.6% of non-PML MS patientstreated with natalizumab were anti-JCV–seropositive.The investigators interpreted theirresults as warranting further research on theclinical utility of the assay as a potential PMLrisk stratification tool for MS patients. Similarly,another ELISA study using baculovirus expressedJCV VP1 showed that 65% of sera from214 MS patients treated with natalizumab andClinical Reviews of JCV and PML • July 2011 S21

88% (22 of 25) sera from natalizumab-associatedPML cases were JCV-seropositive. 7 Thethree patients with PML who were JCV-seronegativewere tested during plasma exchange.Seronegativity during plasma exchange mightreflect not seronegativity but the eliminationof anti-JCV antibodies from circulation, hencecausing a false-sero negative state. These threepatients were subsequently tested with theGorelik assay and were seropositive. 29 Tyler 5suggested that findings from these two studiesmay indicate potential use of JCV antibodytesting for estimating risk of natalizumabassociatedPML development. However, becauseof very high prevalence of JCV seropositivityin the general population, JCV antibodytesting may be of limited use in predictingPML development among seropositive individuals.Indeed, there is almost no risk of PMLdevelopment in JCV-seronegative individuals.Antibody testing may be useful in excludingthe risk of PML development in JCV-seronegativeMS patients treated with natalizumab orother monoclonal antibodies.Clinical OutcomesCurrently, there are no proven therapiesor vaccines available for the treatment andprevention of PML. Although early observationalstudies demonstrated promising resultswith cidofovir in improving survival ofHIV-positive patients with PML in combinationwith cART, subsequent studies have concludedthat cidofovir therapy has no significanttherapeutic benefit. 8 Similarly, while oneretrospective study suggested that cytarabinemay stabilize PML in a subset of HIV-negativepatients, subsequent studies failed to show asurvival benefit. Drugs such as mirtazapineand mefloquine have shown some promisein anecdotal or small case studies, but furtherstudies are warranted to prove their beneficialeffect against PML. In the absence of effectiveantiviral pharmacotherapy targetingPML, restoring the host’s adaptive immuneresponse against JCV remains the currentmanagement objective—achieved mainly bytreatment with cART in HIV-positive patientsand by reducing immunosuppressive or immunomodulatingdrugs where possible inHIV-negative individuals.A few HIV/AIDS patients after the initiationof cART and almost all cases of PML associatedwith natalizumab after discontinuation oftherapy may develop PML-IRIS. 2,8 In PML-IRIS,although the recovering immune system maycontrol JCV replication, it can also aggravateCNS inflammation and may accentuate theclinical picture. 2 Inflammation can also lead tosignificant neurological deficits, mass effectswith herniation, and other catastrophic effects,including death. The use of steroids can be beneficialin such severe cases and, when appropriatelymanaged, PML-IRIS has been reportedin multiple instances to lead to prolonged survivaland even improvement in PML-relatedneurological deficits. Vermersch et al 11 recentlyreported a 71% survival rate in natalizumab-treatedPML patients, attributed in partto aggressive corticosteroid management ofIRIS and rapid diagnosis once symptoms wereidentified. The use of steroids remains controversialbecause, as immunosuppressants, steroidsmight increase replication of HIV in HIVpositivepatients or alter treatment regimensin HIV-negative patients who have cancer orautoimmune disease. 8 While short-term discontinuationof cART may reduce the symptomsof PML-IRIS in HIV-positive patients,even short-term interruption of the therapycan increase HIV mutation rate, resulting infuture drug resistance.Survival RatesThe onset of PML is insidious, but in the absenceof treatment disease progression is usuallyrapid, with death ensuing in three to sixmonths after diagnosis. With the advent ofcART in the mid-1990s, however, HIV-positivepatients are living longer. 8 Several studies havedemonstrated that cART significantly prolongslife span of AIDS-associated PML caseswith one-year survival being 50% or more,while it was 5% or less in patients not receivingcART. 26,30-35While PML-IRIS appears to be more commonand more severe in patients with natalizumab-associatedPML than it is in patientsS22 July 2011 • Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML

with HIV-associated PML, recent studies suggestthat early recognition and treatment ofmonoclonal antibody-associated PML-IRISimproves prognosis. 10,11Higher CD4+ T-cell count, contrast enhancementon radiographic imaging and neurologicalrecovery, 8,35-37 and low JCV load inthe CSF 8,30,38-40 are all associated with longersurvival in HIV-associated PML patients. In a1998 study of biopsy-proven, AIDS-associatedPML, nearly 43% of the long-term survivors(≥12 months) had CD4 T-lymphocyte countsgreater than 300 cells/mm 3 versus 4.3% of theshort-term survivors (≤12 months). 36 Radiographicimaging demonstrated contrast enhancementin 50% of the long-term survivorscompared with only 9% of the short-term survivors,whereas neurological recovery and radiographicimprovement were seen only in thelong-term survival group (71.4%).Subsequent study on HAART-treated HIVassociatedPML cases corroborated thesefindings. 37 The two patients who died afterthree months had more extensive white matterchanges on their initial MRI studies thanthe two long-term survivors, and follow-upimaging revealed progressive destructive diseasein the short-term survivor group. The twolong-term survivors, both of whom were aliveat the time the study’s findings were reported(at 22 and 43 months’ survival, respectively),had evidence of development of a mass effecton follow-up MRI, and the studies of oneof the two patients demonstrated temporaryenhancement, suggesting to the investigatorsthat such findings in the early phase of treatmentmay represent positive predictive factorsfor longer-term survival.More recently, the presence of JCV-specificCD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) in patientswith PML was associated with a trendtoward longer survival. 35 In a study reportingthe clinical outcomes of 60 patients with PML,73% of whom were HIV-positive, Marzocchettiand colleagues 35 found that PML patients withdetectable CTLs within three months of diagnosishad an estimated probability of survivalat one year of 73% versus 46% for those withoutCTLs, rates that could be juxtaposed with theone-year estimated survival of HIV-positiveand HIV-negative patients with PML—52% and58%, respectively. Meanwhile, the estimatedone-year survival rate of HIV-positive patientswith PML who had a CD4 count greater than200/microL at the time of PML diagnosis was67% versus 48% for those with a CD4 count lessthan 200/microL, but this trend toward longersurvival in the former group was found by theinvestigators to be less pronounced than thepresence of CTLs.The magnitude of the JCV load in the CSFhas been examined in several studies andfound to be inversely correlated with survival.8,30,38-40 Taoufik and colleagues 38 measuredJCV load in CSF of 12 AIDS-associated PMLpatients using quantitative PCR and demonstrateda significant inverse correlationbetween JCV load in CSF and survival time(P < .01). Patients with high JCV loads diedwithin eight months after the onset of PMLand within three months after JCV quantitation;whereas patients with low virus loadswere still alive at the end of the study, withsurvival times greater than 19 months afterthe beginning of PML and 13 months afterCSF sampling. These results suggested thatCSF JC virus load determination may be usefulin monitoring anti-JCV therapies in PML.Subsequently, Yiannoutsos and colleagues 39estimated JCV burden in CSF samples from15 AIDS-associated biopsy-proven PML patientsby semiquantitative PCR and demonstratedthat lower viral load was predictive oflonger survival (median survival from entry,24 weeks) compared with a high JCV burden(7.6 weeks). Similarly, Garcia De Viedma andcolleagues 40 in 2002 also found an inverse correlationbetween JCV load in CSF and survivaltime—patients with JCV load greater than4.68 log had shorter survival than those withlower viral load. These results were virtuallyidentical to those of a multicenter analysis of57 HIV-positive PML patients treated with andwithout HAART, in which a baseline JCV DNAload of less than 4.7 log helped predict longersurvival among HAART-treated patients. 30Probability of survival at one year in this latterstudy was .46 with HAART and .04 without it.Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML • July 2011 S23

The marked difference in survival in thatmulticenter analysis points to the progress thathas been made in altering the prognosis of patientswith PML. Prior to the advent of HAART/cART, only about 10% of HIV-positive patientssurvived at least one year following PML diagnosis.9,41 In an evaluation of the clinical and radiographicfeatures of PML in a cohort of 154AIDS patients, median survival was six monthsand 9% of patients were alive more than oneyear after PML was diagnosed. 3 With the introductionof cART, however, the one-year survivalrate has risen to approximately 50%. 8,9,31 TheItalian Registry Investigative Neuro AIDS StudyGroup found, for example, that patients startingHAART at diagnosis of PML who had previouslyreceived antiretrovirals demonstrateda significantly higher one-year survival probability(58%) versus those continuing HAART(24%) or who never received it (0%). 31Clinical vigilance, early diagnosis, andprompt treatment (discontinuation ofnatalizumab, initiation of plasmaexchange) were associated withimproved survival.More recent data from the United Statesare even more promising and suggest that, foran increasing number of HIV-positive patients,PML has become a chronic disorder ratherthan a relentlessly and rapidly progressive fataldisease. 9 In a study of the clinical outcomeof long-term survivors of PML, investigatorsfollowed 24 patients who survived more thanfive years from disease onset, with a meanfollow-up period of 94.2 months. All but oneof the patients were HIV-positive and receivedHAART, and the remaining patient had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and was HIV-negative.<strong>Mark</strong>ed improvement of neurological functionoccurred in 4 of 24 patients (17%), partial improvementwas observed in 11 of 24 (46%), and9 of 24 (37%) remained stable. At the end of theobservation period, one-third of patients (8 of24) had no significant disability despite persistentsymptoms, one-quarter (6 of 24) hadslight disability and could live independently,and equal numbers of the remainder (5 of 24,21%, in each group) either were moderatelydisabled or had moderately severe disabilityrequiring constant help or institutionalization.Survival in the study was linked to the patients’ability to initiate a cellular immune responseto the JCV. 8,9 The 23 HIV-positive patients had amedian CD4 count of 389/mL at the end of theobservation period, and 19 of 23 (83%) had undetectableHIV RNA in their plasma. 9 Nineteenof 20 patients (95%) tested in this series haddetectable JCV-specific CD8+ CTLs in theirperipheral blood. The authors argued that improvedprognosis of HIV-positive patients withPML resulted from HAART-associated immunerecovery:In fact, PML is becoming a chronic disease—ratherthan a fatal disease—in agrowing number of HIV-infected patients.For this reason, it is important to understandthe clinical outcome of long-termsurvivors of PML in HIV-infected patients….Interestingly, the overwhelmingmajority of tested subjects [in our cohort]had a detectable cellular immuneresponse against JCV, which confirmsprevious studies on the role of T lymphocytesin PML survival. 9Interestingly, one-year survival rates betweenpatients with PML-IRIS (54%) and PMLpatients without IRIS (49%) were comparable,suggesting that the inflammatory reaction associatedwith IRIS does not alter the survivalrate of patients with PML—in contrast to whathas been observed for classic PML in otherstudies.Recent evidence indicates that survival ofmonoclonal antibody–associated PML patientsis improving. In one of the largest series reportedin MS patients who had natalizumabassociatedPML, 20 of 28 patients (71%) werestill living at the time of reporting. 10 Clinicalvigilance, early diagnosis, and prompt treatment(discontinuation of natalizumab, initiationof plasma exchange) were associatedwith improved survival. 10 Vermersch and colleagues11 reported a similar survival rate (71%)in a study of clinical outcomes in 35 cases ofnatalizumab-associated PML.S24 July 2011 • Clinical Reviews of JCV and PML

Natalizumab, the first monoclonal antibodyapproved for the treatment of relapsingforms of MS, was voluntarily withdrawn fromthe US and European markets in February 2005after three patients undergoing therapy withthe drug in combination with other immunoregulatoryand immunosuppressive agentswere diagnosed with PML. 5,8 However, it wasreintroduced again as a monotherapy for MSin June 2006, and since its reintroduction 130additional cases developed PML among 83,300exposed patients through June 1, 2011.Of the three natalizumab-associated PMLcases reported in 2005, two were fatal. In one,the diagnosis of a 60-year-old man who hadreceived natalizumab for Crohn’s disease waschanged from fatal astrocytoma to PML afteranalysis of frozen serum samples revealedthat JC virus DNA was detectable in the serumthree months after the start of monotherapywith the monoclonal antibody and two monthsbefore the appearance of symptomatic PML. 42In a second case, a 46-year-old woman withrelapsing-remitting MS participating in a clinicaltrial of combined therapy with natalizumaband interferon beta-1a, in which she received37 doses of the monoclonal antibody (300 mg)every four weeks, died from PML, which wasdiagnosed by PCR assay (JCV DNA in the CSF)and confirmed at autopsy. 43 The third case,which also involved combination therapywith interferon beta-1a in a patient with MS,highlights the importance of early detection,differential diagnosis, and swift treatment response.44 Although the first PML lesion seen onMRI was indistinguishable from an MS lesion,PML was diagnosed and progressed rapidly,even though natalizumab was discontinuedand treatment with corticosteroids, cidofovir,and IV immunoglobulin was initiated. The patientbecame quadriparetic, globally aphasic,and minimally responsive; but within threemonths following natalizumab discontinuation,changes consistent with PML-IRIS weredetected and systemic cytarabine was initiated,leading to improvement in the patient’scondition in two months.The risk of PML development increaseswith duration of exposure to natalizumab.Once natalizumab was approved again for usein June 2006, no new cases of PML were reportedduring the first two years of the drug’sremarketing. The first reported case was diagnosedin July 2008 following the appearance ofsymptoms. In subsequent months, one to twocases per month were reported, for a total of31 by the end of January 2010. Of the 28 PMLcases confirmed by the end of November 2009,eight were fatal and, of the 20 who survived,many had serious morbidity and substantialand permanent disability. The median treatmentduration to onset of symptoms for all 28cases was 25 months. None of the 28 patientswere on concurrent therapy with interferonbeta and, while three patients had never receivedany disease-modifying therapy otherthan natalizumab, previous treatment withother immunosuppressants (including interferon)may have increased the risk of PML, accordingto the investigators.Treatment response in this series illustratesthe complexities of the improved prognosisin patients with natalizumab-associatedPML. In 27 cases, either plasma exchange orimmunoabsorption was used to achieve rapidclearance of natalizumab and restorationof CNS immune surveillance. In almost all ofthese cases, the subacute progression and exacerbationof earlier symptoms of PML thatare typical of IRIS occurred within days to afew weeks of plasma exchange. High-dose corticosteroidtherapy has been used to treat IRISwith some success, and in many cases in thisseries repeated courses of IV steroid were given.Death was more common among patientswho were either untreated or inadequatelytreated with corticosteroids. Prognosis wasalso related to the location of lesions and isprobably a more important prognostic factorthan is the size of the lesions. Cases in whichlesions affected such critical regions as thebrainstem had the most serious consequencesand, while higher JCV titers in the CSF are generallyassociated with larger lesions size, patientswho presented with low viral loads wereamong the fatal cases in the series. In one casein which JCV was not detected in CSF and neitherplasma exchange nor immunoabsorptionClinical Reviews of JCV and PML • July 2011 S25