Saving Gunung Palung: A Rainforest Marriage - Cheryl Knott

Saving Gunung Palung: A Rainforest Marriage - Cheryl Knott

Saving Gunung Palung: A Rainforest Marriage - Cheryl Knott

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

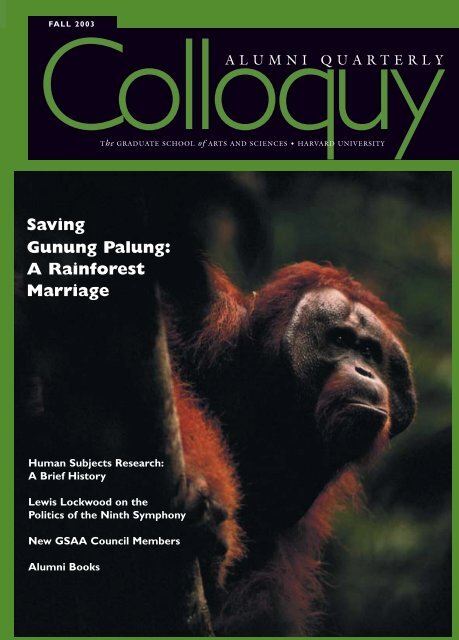

FALL 2003ColloquyALUMNI QUARTERLYThe GRADUATE SCHOOL of ARTS AND SCIENCES • HARVARD UNIVERSITY<strong>Saving</strong><strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong>:A <strong>Rainforest</strong><strong>Marriage</strong>Human Subjects Research:A Brief HistoryLewis Lockwood on thePolitics of the Ninth SymphonyNew GSAA Council MembersAlumni Books

The GRADUATE SCHOOL of ARTS AND SCIENCES • HARVARD UNIVERSITY24<strong>Saving</strong> <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong>:A <strong>Rainforest</strong><strong>Marriage</strong>The hopes and fears of husband-and-wife teamHarvard anthropologist <strong>Cheryl</strong> <strong>Knott</strong> and biologist(and wildlife photographer) Tim Laman, trying tosave a Borneo rainforest.Human Subjects Research:A Brief HistoryHow do researchers—and their human subjects—ensure that experiments are being conductedethically? Research guidelines are a relatively newphenomenon; we take a brief look at how theyoriginated and how they affect research atHarvard today.ColloquyALUMNI QUARTERLYMargot N. Gilladministrative deanPaula Szocikdirector of publications and alumni relationsSusan LumenelloeditorSusan Gilberteditorial assistantJames Clyde Sellman, PhD ’93, historycopy editorplus design inc.designChampagne/Lafayette Communications Inc.printing6ON THE COVER:1417Understanding the Politics of the NinthSymphonyAn excerpt from the new book on Beethoven byProfessor Emeritus Lewis Lockwood:Whatpolitical, social, and personal factors influencedthe writing of this masterpiece, and how has theartist’s intention been subverted and revisedover the centuries?Alumni BooksProgressives branch out, colonial-era justice isdelivered (or not), the American President evokedon film, the diplomacy of Lyndon Johnson, andmore from recently published books by GSASalumni.On DevelopmentThe English Language Program introducesincoming international students to life atHarvard and the American classroom.One of the 2,500 or so wild orangutans living in <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong> National Parkin Borneo. Photo by Tim Laman.GRADUATE SCHOOL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION (GSAA)COUNCILNaomi André, PhD ’96, musicReinier Beeuwkes III, COL ’62, PhD ’70, division ofmedical sciencesLisette Cooper, PhD ’87, geological sciencesA. Barr Dolan, AM ’74, applied sciencesRichard Ekman, AB ’66, PhD ’72, history of AmericancivilizationJohn C.C. Fan, SM ’67, PhD ’72, applied sciencesDonald Farrar, AB ’54, PhD ’61, economicsCharles Field, PhD ’71, urban planningNeil Fishman, SM ’92, applied sciencesKenneth Froewiss, AB ’67, PhD ’77, economicsWerner Gundersheimer, PhD ’63, history, GSA ’66Homer Hagedorn, PhD ’55, historyR. Stanton Hales, PhD ’70, mathematicsDavid Harnett, PhD ’70, history, ex officioKaren J. Hladik, PhD ’84, business economicsMary Lee Ingbar, SB ’46, PhD ’53, economics,MPH ’56Ishier Jacobson, SM ’47, applied sciences, LLB ’51Andrew Jameson, PhD ’58, historyDaniel R. Johnson, AM ’82, East Asian history,AM ’84, business economicsGopal Kadagathur, PhD ’69, applied sciencesAlan Kantrow, AB ’69, PhD ’79, history ofAmerican civilizationRobert E. Knight, PhD ’68, economicsFelipe Larraín, PhD ’85, economicsJill Levenson, PhD ’67, English and Americanliterature and languageSee-Yan Lin, MPA ’70, PhD ’77, economics, chairBarbara Luna, PhD ’75, applied sciencesSuzanne Folds McCullagh, PhD ’81, fine artsIvan Momtchiloff, AM ’58, applied sciencesJohn J. Moon, AB ‘89, PhD ’94, business economicsSandra O. Moose, PhD ’68, economicsF. Robert Naka, SD ’51, applied sciencesMaury Peiperl, MBA ‘86, PhD ‘94, organizational behaviorM. Lee Pelton, PhD ’84, English and Americanliterature and languageNancy Ramage, PhD ’69, classical archaeologyJohn E. Rielly, PhD ’61, governmentAllen Sangines-Krause, PhD ’87, economicsCharles Schilke, AM ’82, historySidney Spielvogel, AM ’46, economics, MBA ’49Dennis Vaccaro, PhD ’78, division of medical sciencesDonald van Deventer, PhD ’77, economicsGustavus Zimmerman, PhD ’80, physics

from the deanBringing TogetherOur Global CommunityPeter T. Ellison, GSAS dean,PhD ’83, biological anthropologyHARVARD ALUMNI ASSOCIATIONAPPOINTED DIRECTORSLisette Cooper • Donald van DeventerGSAA COUNCIL EX OFFICIOLawrence H. SummersPhD ’82, economicspresident of Harvard UniversityWilliam C. KirbyPhD ’81, historydean of the Faculty of Arts and SciencesPeter T. EllisonPhD ’83, biological anthropologyThis November, GSASwill sponsor its firsteveralumni event inEurope. This event, asymposium of Harvardfaculty who will look at “The Modern ArtMuseum in a Global Context,” will be held indean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences London as part of the University-wideMargot N. Gilladministrative dean of the Graduate School ofArts and SciencesMichael ShinagelPhD ’64, English and American literature and languagedean of Continuing Education and University ExtensionThomas M. Reardonvice president for Alumni Affairs and DevelopmentJohn P. Reardon Jr.AB ’60executive director of the Harvard Alumni Association“Harvard in Europe” series.The GSAS event will help expand and consolidateHarvard’s role as a global leader inhigher education. It will also enable many ofour alumni living overseas to reconnect withone another and enjoy an afternoon of “continuingeducation.”With approximately 2,000 GSAS alumniThe GSAA is the alumni association of HarvardUniversity’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. residing in Europe, we have been eager toGoverned by its Council, the GSAA represents sponsor such an event. Now that it’s upon us,and advances the interests of alumni of theGraduate School by sponsoring alumni events and we are already planning similar gatherings inby publishing Colloquy four times each year.Graduate School Alumni AssociationByerly Hall 3008 Garden StreetCambridge, MA 02138-3654phone: (617) 495-5591 • fax: (617) 495-2928gsaa@fas.harvard.edu • www.gsas.harvard.eduother countries where GSAS alumni live andwork.And GSAS alumni are indeed everywhere.In addition to the 2,000 or so in Europe—andmore than 30,000 in North America—about1,300 alumni reside in Asia; over 200 in theMiddle East; nearly 200 in Central and SouthCOLLOQUY ON THE WEBAmerica; over 150 in the Australia/OceaniaThe current issue of Colloquy, as well as recentback issues, are available on the Web at www.gsas. region; and nearly 100 in Africa.harvard.edu/colloquy.We have begun to see this internationalpresence reflected in the composition of ourLETTERS TO THE EDITORAlumni Association Council: Chair See-YanColloquy welcomes your letters. Write to:Colloquy, Harvard University Graduate School of Lin (PhD ’77, economics) is from Malaysia, andArts and Sciences, Byerly Hall 300, 8 GardenStreet, Cambridge, MA 02138-3654; or e-mailgsaa@fas.harvard.edu.Council members include Felipe Larraín (PhD’85, economics) of Chile, Jill Levenson (PhD’67, English and American literature and language)of Canada, and Maury Peiperl (PhD ’94,MOVING?Please send your Colloquy mailing label and yournew address to Alumni Records, 124 Mt. Auburn organizational behavior) and Allen Sangines-Street, Fourth Floor, Cambridge, MA 02138-3654. Krause (PhD ’87, economics) of England.These individuals see themselves—rightfullyso—as ambassadors of GSAS to the worldbeyond Cambridge. They keep us connectedto the various nations our students—currentand prospective—call home, and to the placeswhere so many of our alumni live and work.In addition, other Council members regularlytravel outside the United States and meetwith local GSAS alumni on behalf of ourGlobal Outreach Committee.These dedicated alumni are a testament toGSAS’s role in nurturing the world’s intellectualcapital and in promoting the internationalexchange of ideas.To do this well, however,we need the input of our alumni living abroad.I ask you to take a moment to write to let usknow how GSAS can better serve you—andhow you would like to see GSAS better serveour students.One issue on many people’s minds is theUSA Patriot Act, which went into effect inJanuary 2003. Part of its mandate is a closerscrutiny of international student visa applications.I’m pleased to report that we saw far fewervisa denials than we had anticipated, cominginto this academic year. We have workedclosely with the US State Department toensure that our academic visitors would beaccorded the proper consideration.We are as enthusiastic as ever about workingwith the brightest young scholars fromevery part of the globe, and we will continueto offer them the greatest research and scholarlyopportunities available.I look forward to meeting some of you inLondon shortly, and to hearing from others ofyou in the near future.Colloquy 1 Fall 2003

science in the field<strong>Saving</strong> <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong>: A <strong>Rainforest</strong> <strong>Marriage</strong>By Susan LumenelloTheirs is a story grounded in science.He’s a biologist, she’s ananthropologist, and they startedtheir lives together while doing fieldworkin, and helping to save, a 24,000-acre Indonesian rainforest park and itsinhabitants.<strong>Cheryl</strong> <strong>Knott</strong>, an assistant professorof anthropology who earned her PhD in1999, and husband Tim Laman, a scientificassociate of the Museum ofComparative Zoology and wildlife photographerwho earned his doctorate inorganismic and evolutionary biology in1994, met as students at the GraduateSchool of Arts and Sciences in the early1990s.A decade later, <strong>Knott</strong> and Laman areproud parents of three-year-old Russelland his sister-to-be (due in December)—and they’re still working in the rainforest,studying the animal and plantlife unique to the Indonesian island ofBorneo and one of its largest nationalparks, <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong> (pronounced:goo-noong paw-loong). <strong>Knott</strong> hasmade a career studying orangutans,who only live in the wild in the junglesA match made at GSAS:Tim Laman, PhD ’94,and <strong>Cheryl</strong> <strong>Knott</strong>, PhD ’99, in the rainforestcanopy of the <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong> National Park.All photos in this story by Tim Laman.of Indonesia and Malaysia; Laman did hisPhD work on strangler fig trees and hasstudied a variety of creatures in the park asa field scientist for Harvard and a wildlifephotographer for National Geographic.But <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong> and the 5,000-acreCabang Panti research site within it isthreatened, <strong>Knott</strong> says. Illegal logging hasdegraded large areas of the park and hasnow invaded the study site’s trail system,putting into doubt the survival of the2,500 or so orangutans that live there.According to a recent census taken by<strong>Knott</strong>’s team, that’s about ten percent ofthe world’s orangutan population; theother approximately 23,000 orangutansreside in national parks and reserves elsewhereon the islands of Borneo andSumatra.From January to February of this year,<strong>Knott</strong>, Laman, and their colleagues askedIndonesian officials for more protection ofthe site. They wanted to help governmentofficials “realize the importance of thisarea and its uniqueness,” Laman says.“Consequently there was a big patrol—thenational police force went in and clearedthe place out. Hopefully, our efforts hadsomething to do with that.”Illegal logging involves a substantialportion of the village population around<strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong>. “Something like twothirdsof the households in the area areinvolved in illegal logging [around thenational park],” <strong>Knott</strong> says. “That’s thousandsof people.”The good news is that the park’s forestshave not been clear-cut. The damage hasbeen “selective,” according to <strong>Knott</strong>. Thebiggest and best trees are cut, those sure tobring the best prices on the market, andsmaller trees are taken later. Still, considerabledamage is being done to the habitat.“They come in and cut an area, it getsdried out, and then it’s vulnerable to fire,”<strong>Knott</strong> says. “Once it burns, and they convertit to rice fields, then it’s going to betotally gone. We’re at a point now wherethere’s been a lot of logging, but it’s been inpockets. If it was to stop now, [the forest]could … regenerate. It would take a while,but it would be okay.”Whether that can happen depends uponstricter controls being placed on the illegalloggers. Unfortunately, the most extensivelogging is being done in the lowland forestand the peat swamp, the areas where mostorangutans live. Some can survive in thelogged areas, but it is unclear whether thepopulations are large enough to be viable.AN UPHILL BATTLELocal corruption throws a major wrenchinto the battle for the rainforest. “We’vehad very little power to do much about it,and it’s very frustrating,” Laman says.“But the scale of corruption is so great,and the powers that are involved are sostrong that, as scientists, we feel we haveso little influence. We can only try to arguethe case with Indonesian scientific agenciesand parks departments. Changing thewhole culture of corruption is … reallygoing to be long-term.”“Since the fall of [President] Suharto,there has been a lot of decentralization. Alot more control has been given to theprovinces,” <strong>Knott</strong> says. “So, even thoughthe national government wants to stop it… it’s difficult because some of the localgovernment officials—the police, the military—areinvolved in illegal logging.”The loggers who were arrested back inthe winter of this year are still awaitingtrial, according to <strong>Knott</strong>. “They have to beHarvard University2GSAS

tried locally,” she says. “Whether or notthat’s going to happen, we’re waiting tosee.”Unfortunately, the rules of evidence arefoggy to say the least, <strong>Knott</strong> says.“According to the local police, if you findsomeone with a chainsaw in a nationalpark, you can’t arrest them for illegal loggingbecause someone else will say, ‘Howcan you prove he was there doing illegallogging?’” she says. “If you have a pictureof him cutting down a tree in the park,that’s not good enough evidence because,‘That picture could have been taken someplaceelse.’ And … a policeman or rangersaying, ‘I saw this person cutting down atree in a national park,’ isn’t consideredvalid testimony.”Orangutan poaching for food and forthe illegal pet trade, which has steadilyincreased in recent years, is also threateningthe ape population.“Most people [on Borneo] are Muslim,so they don’t eat orangutans,” <strong>Knott</strong> says.“But some of the Dyak people, the localindigenous people of that area, do eatorangutans. So some of the illegal loggerswill kill to sell the meat to the Dyaks. Andthey’ll kill mothers for their babies for theillegal pet trade.”Three years ago, <strong>Knott</strong>’s team set up atransit center for rescued baby orangutans.She estimates that they’ve brought in about25 infants who had been kidnapped.“When they’re infants, they want tocling to you like they’re little babies. Butonce they’re six-year-olds, what do you dowith them? They’re super strong. Theybite. So people don’t want them, they discardor abuse them, and we find them incages,” <strong>Knott</strong> says.The kidnappings are made even moredisturbing when one realizes that for everykidnapped orangutan baby, a motherorangutan was killed. And since femaleorangutans only reproduce about onceevery eight years, the death of even one hasa major negative impact on this diminishingspecies.A DISTINCTIVE SPECIESOrangutans are particularly susceptible toextinction. “They give birth so rarely;they’re not fast reproducers,” <strong>Knott</strong> says.“But they do seem to have quite high survivorship—theirbabies are not dying veryoften from natural causes.”Studying orangutans is very time-intensivecompared to many other animals.There are two reasons for this. One,orangutans have the longest intervalbetween births of any primate, includinghumans. Two, they’re solitary creatures.After mating, mother and baby go in onedirection while the now lone male goes inanother. This seemingly anti-social lifestylehas to do with the scarcity and wide dispersalof the orangutans’ food supply.They must travel, literally, far and wide tosecure food that is irregularly available.<strong>Knott</strong> has charted the lives of females,males, and juveniles to learn more aboutorangutan reproduction and the environ-continued on page 8ALUMNINOTESASTRONOMYMichael Zeilik, PhD ’75, professor ofphysics and astronomy at the Universityof New Mexico, is the 2003 recipient ofthe Excellence in Introductory CollegePhysics Teaching Award by the AmericanAssociation of Physics Teachers (AAPT).As recipient, Professor Zeilik presenteda lecture at the AAPT summer meeting.He received the Astronomy EducationPrize from the American AstronomicalSociety in 2002.COMPARATIVE LITERATUREEllen Peel, GSA ’76, announces thepublication of her book Politics,Persuasion, and Pragmatism: A Rhetoric ofFeminist Utopian Fiction (Ohio State,2002). She is a literature professor in theDepartments of Comparative and WorldLiterature and of English at San FranciscoState University.ENGLISH AND AMERICANLITERATURE AND LANGUAGEHeather Dubrow, PhD ’72,Tighe-Evansand John Bascom Professor at theUniversity of Wisconsin at Madison,writes that she has been awarded aNational Endowment for the HumanitiesFellowship and a Guggenheim Fellowshipfor a new book that reexamines theworkings of the early modern(Renaissance) lyric.GOVERNMENTAndrew Rudalevige, PhD ’00, receivedthe American Political Science Association’sRichard E. Neustadt Award for thebest book on the presidency published in2002, Managing the President’s Program:Presidential Leadership and Legislative PolicyFormulation (Princeton). He is an assistantprofessor of political science atDickinson College.HISTORYMary Beth Norton, PhD ’69, writesthat her most recent book, In the Devil’sSnare:The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692(Knopf), received the Ambassador BookAward by the English-Speaking Union asthe best book in American studies for2002.The scene after illegal loggers have degraded a section of the park.MATHEMATICSSolomon W. Golomb, PhD ’57,University Professor and Andrew andErna Viterbi Chair in Communications atthe University of Southern California,reports on a busy 2003. In April,Professor Golomb was elected to theNational Academy of Sciences. In May, hereceived a Distinguished Alumnus Awardfrom his (undergraduate) alma mater,Johns Hopkins University and waselected a fellow of the AmericanAcademy of Arts and Sciences. "I hadbeen elected a fellow of the AmericanColloquy 3 Fall 2003CONTINUED ON PAGE 5

on academeHUMAN SUBJECTS/HUMANE RESEARCH:THEN AND NOWBy Janine Brunell LookerWalk into the lobby of WilliamJames Hall, which houses thepsychology department, andyou will find a sign reading, “SubjectsWanted.” The sign directs you to bulletinboards cluttered with various invitationsto participate in psychological researchprojects in exchange for nominal monetaryrewards. “Judge People for $$,”one reads. “Participants Wanted forPsychology Experiment on Memory”reads another.Seems harmless enough.Yet history has taught us that researchconcerning human subjects is as perilousas it is essential. Without such research,the advancement of knowledge in medicine,psychology, and sociology would besluggish, if not altogether impossible.Without it, treatments for cancer, therapiesfor psychological illnesses, andadvances in social understanding wouldbe nonexistent.Yet it is also true that without suchresearch, thousands would have beenspared atrocities and death at the handsof Nazi doctors during World War II, andhundreds of African-American men in theUnited States could have been cured ofsyphilis. The list goes on.This tension between the methods usedto advance scientific knowledge and thedamage these methods may inflict onindividuals has spurred the developmentof ethical standards concerning humanresearch subjects. And it was in reactionto science’s most flagrant offenses thatsuch codes of ethics were conceived.INSTITUTIONAL REVIEWDean Gallant is assistant dean forresearch policy and administration andexecutive officer of the Faculty of Artsand Sciences Standing Committee on theUse of Human Subjects in Research.“There were a number of cases in the1950s and ’60s where the abuse of humanresearch subjects led to the institution offederal regulations to protect these subjects,”he says. Among these was a studyof immune-compromised patients byresearchers who injected cancer cells into“an unwitting group of elderly people.Largely as a result of studies like this, federalrequirements were instituted to establishcommittees such as ours.”The Committee on the Use of HumanSubjects in Research is one of three suchinstitutional review boards (IRBs) atHarvard (the other two are within theMedical School and School of PublicHealth). IRBs approve all research proposalsinvolving human subjects thatwould be conducted at the University, andthey are also mandated to educate andinform researchers about the ethical complexitiesinvolved in human subjectresearch.IRBs also offer guidance for graduatestudent researchers. “There is a generalonline program offered to all researchersusing human subjects—required whenNIH funds are involved,” Gallant says.Harvard’s three IRBs, under the auspicesof the Provost, have just been awarded agrant by the NIH to expand and enhancethis online program, he says, includingdeveloping separate modules for differentdisciplines. In-depth instruction for GSASstudents in the ethics of human subjectsresearch is also integrated by departmentsinto students’ research training curriculum,Gallant adds.At the core of the standards adopted byHarvard and other research institutions isthe Nuremberg Code. It was establishedduring the 1946 trial of 20 physicianswho, “in the name of science,” performedexperimental procedures on concentrationcamp prisoners.The Nuremberg Code laid out ten conditionsto define the practice of ethicalresearch. Among these was a mandate forthe consent of subjects and for the worthinessof the research being considered.Elements of the Nuremberg Codeappeared in the code of standards setseven years later by the NationalInstitutes of Health (NIH). The NIHguidelines were established in response toallegations that American doctors wereperforming unethical research on humansubjects at hospitals and universities—as,for example, in the notorious Tuskegeeand Willowbrook studies.The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–72)was a federally funded research project inwhich 400 African-American men withsyphilis were deceived into participatingin a study of that disease. During thecourse of the study, penicillin was discovered.Although the drug became widelyused as an effective treatment for syphilis,it was withheld from the subjects of theHarvard University4GSAS

Tuskegee study until the research wasstopped. (President Clinton issued an officialapology to the surviving study victimsin 1997.) In the Willowbrook Study, whichtook place in the mid-1960s, childrenadmitted to New York’s WillowbrookState School as “mentally defective persons”were deliberately infected with hepatitisin order to study the progression ofthat disease.These experiments were exposed in theNew England Journal of Medicine andother publications. “Together these revelations—andothers like them—exposed aresearch culture in which the interestsof subjects had been fundamentallydisregarded in the name of science,”wrote Allan Brandt, Amalie Moses KassProfessor of the History of Medicine anddirector of the Division of Medical Ethics,Harvard’s Standing Committee on the Useof Human Subjects. Calhoun, Gallant, andother committee members review as manyas 700 proposals each year.“We do a certain amount of advising—most of the proposals we review requireonly that,” she says. “Occasionally we runacross a proposal that causes concern.”A CASE IN POINTALUMNINOTESCONTINUED FROM PAGE 3Association for the Advancement ofScience some 15 years earlier; so I amnow a ‘fellow of the AAAS’ twice over,"he writes. Also in May, days before his71st birthday, Professor Golombattended meetings in Haifa as a memberof the Technion-Israel Institute ofTechnology’s Board of Governors andAcademic Advisory Committee.MUSICCamilla Cai, AM ’65, recently wasnamed Kenyon College’s second JamesD. and Cornelia W. Ireland Professor ofMusic. Professor Cai, who joined thecollege’s faculty in 1986, specializes in themusicology of Germany and Scandinavia.She is the co-author of Ole Bull: Norway’sRomantic Musician and CosmopolitanPatriot (Wisconsin, 1993) and books andchapters on Brahms, Mendelssohn, andSchumann, among other composers.PHYSICSJohn Mansfield, PhD ’70, reports thatPresident Bush reappointed him for asecond term as member of the DefenseNuclear Facilities Safety Board inWashington. The Board oversees theDepartment of Energy’s nuclearweapons and cleanup activities at sitesaround the country.A hallway in the lobby of William James Hall, where dozens of flyers are posted by faculty and graduatestudent researchers seeking human subjects for research projects.in “Bioethics: Then and Now” (HarvardHealth Policy Review, Spring 2002).In reaction to these research abuses, theNational Commission for the Protection ofHuman Subjects of Biomedical andBehavioral Research was formed and, in1979, published “The Belmont Report:Ethical Principles and Guidelines forthe Protection of Human Subjects ofResearch.” The human subjects regulationslaid out in this report are revisitedregularly.Following these regulations closely isJane Calhoun, an IRB research officer forOne proposal, submitted by Jill Hooley,professor of psychology, involved playingtapes of critical statements made by theirmothers to subjects suffering—or recovering—fromdepression. Hooley studies whypsychiatric patients relapse. “I am interestedin family factors that might be associatedwith patients who do poorly or, conversely,who do well when they are recoveringfrom an episode of illness,” she says.“Research literature has taught us thatcertain kinds of family variables seem to bequite predictive of patients doing wellwhen they are in the recovery process andthat certain of these variables seem to bepredictive of relapse,” Hooley adds. “Oneof these variables is criticism from a closefamily member. This finding has actuallytriggered the development of a number offamily-based interventions to help patientswith these disorders and to reduce rates ofrelapse.”Susan Gilbertcontinued on page 10REGIONAL STUDIES—USSRHarvey Fireside, AM ’55, writes: "Mybook, The 'Mississippi Burning' Civil RightsMurder Conspiracy Trial (Enslow, 2002),was awarded the Carter G. WoodsonBook Prize for "the most distinguishedsocial science book depicting ethnicity"for young readers, by the NationalCouncil for the Social Studies.The bookwas also among the finalists for theNAACP Image Award as the bestchildren’s book" for 2002.IN MEMORIAMStanley Heck, AM ’38, Romancelanguages and literatures, died July 3,2003, in Lincoln, Mass. He had been aresident of Lincoln since 1940 and had alifelong interest in the arts, includinginvolvement in the Lincoln Players andthe Boston Symphony Orchestra. Hewas a past president of the board of theDeCordova Museum. Memorial gifts maybe sent to the Make-a-Wish Foundationof Massachusetts, 295 DevonshireStreet, Boston, MA 02110.TO SHARE YOUR NEWSPlease submit Alumni Notes to: Colloquy,Harvard University Graduate School ofArts and Sciences, Byerly Hall 300,8 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138-3654; or e-mail your news to gsaa@fas.harvard.edu. Please include yourtelephone number or e-mail address.Alumni Notes are subject to editing forlength and clarity.Colloquy 5 Fall 2003

the humanitiesThe Ninth Symphony:The Personal and the PoliticalBy Lewis LockwoodIn his new book, Beethoven: The Music and the Life (Norton), Lewis Lockwood setsout, among other biographical endeavors, to put the music of the world’s most famouscomposer into its historical—and personal—contexts. Lockwood, Fanny PeabodyProfessor of Music Emeritus at Harvard, is also the author of Beethoven: Studies in theCreative Process (Harvard, 1992) and was previously an editor of the journalBeethoven Forum. An excerpt from Beethoven follows. —Susan LumenelloTom KatesProfessor Emeritus LewisLockwood: Of all Beethoven’sworks, the Ninth Symphonyhas had the broadest impact.In 1998 at the Winter Olympics inNagano, Japan, Seiji Ozawaappeared in what may have been thelargest electronic simulation of a concerthall ever imagined. He conducted sixchoirs that were located in New York,Berlin, Cape Town, Sydney, Beijing, andNagano (six cities on five continents) ina televised simulcast in which all of themsang the “Ode to Joy,” the principaltheme of the finale of the Ninth Symphony,electronically synchronized toovercome time differences. Remarkableas this achievement was, it had a background.The “Ode” has been sung at everyOlympic Games since 1956. By the1990s it had become a common practicein Japan for massed choral groups andorchestras to come together in Decemberof each year to give performances ofDaiku—“The Big Nine.”The newly achieved world status ofthe “Ode to Joy” melody is only one ofthe most visible ways in which theBeethoven legend that was created in the19th century has been reshaped andenlarged many times over in the 20th.The very name Beethoven has attainedcult status beyond that of almost anyother classical composer; the cult hasspread through many levels of high,middle, and popular culture in music,art, television, and film. The Beethovenimage, now all too commercially viable,is itself the subject of a sizable literature.And no work has been more fertile increating and maintaining this imagethan the Ninth Symphony.Reprinted with permission from W.W. Norton & Company. Copyright2003 by Lewis Lockwood.In the mind of the general public thereare actually two “Ninth Symphonies.”One is the “Ode to Joy” itself, as choralanthem; that is, just the melody, not theelaborate and complex movement fromwhich it comes. The other is the symphonyas a complete work, a large-scale fourmovementcycle in which the enormousfinale brings solo and choral voices intothe symphonic genre for the first time. Seenas a whole, the movement plan of the workforms a progressive sequence in which thethree earlier movements balance eachother but also prepare the finale and give itmuch of its structural and aesthetic meaning.Beethoven’s setting of the first stropheof Schiller’s poem, beginning “Freude,schöner Götterfunken” (“Joy, beautifulspark of divinity”) is the admitted centerpieceof its finale, but it is matched in significanceby a second, contrasting sectionin a radically different style that sets thefirst chorus of the “Ode,” “Seid umschlungen,Millionen” (“Be embraced, you millions”).The theme and text of “Freude,schöner Götterfunken” is eventually combinedcontrapuntally with that of “Seidumschlungen, Millionen” to form the greatclimax of the movement. The “Seidumschlungen” theme has no chance whateverof being selected as a singable anthemby amateur choral groups because it ismelodically difficult and harmonicallyobscure, and is of a totally different typeand character. In other words, it is animportant feature of the modern history ofthe Ninth Symphony that at popular levelsit is barely known as a symphony atall but is represented only by its mostfamous melody.Harvard University6GSASTHE POLITICAL BACKGROUNDOF THE NINTHIn 1815, during the Congress of Vienna,perpetual spying was the order of the day,and police informers were everywhere.Artists such as Beethoven who wereknown for their republican views were suspect,and the Conversation Books (Editor’snote: After his hearing became severelydiminished, Beethoven used “conversationbooks” to communicate with peoplethrough written questions and remarks)reflect the atmosphere of suspicion thatruled the city. An 1820 entry that wasprobably made in a café says, “anothertime—just now the spy Haensl (Editor’snote: Lockwood notes that this is probablythe spy Peter Hensler) is here.” This situation,combined with Austria’s difficult economicrecovery, Beethoven’s personalfinancial reverses, and the disappearanceor death of many of his traditional aristocraticsupporters, fueled his habitualanxiety. When Dr. Karl von Bursy, recommendedby his old friend Amenda, visitedhim in June 1816, Beethoven ranted loudlyabout the state of things in Vienna:[V]enom and rancor raged in him.He defies everything and is dissatisfiedwith everything, blasphemingagainst Austria and especially Vienna.… Everyone is a scoundrel.There is nobody one can trust. Whatis not down in black and white is notobserved by anyone, not even by theman with whom you have made anagreement.

In a Conversation Book of 1820,[Beethoven’s acquaintance Anton] Schindlerwrote (in a passage not regarded as a lateraddition):Before the French Revolution therewas a great freedom of thought andpolitics. The revolution made thegovernment and the nobility distrustthe common people, which has ledto the current repression. … Theregimes, as they are now constituted,are not in tune with the needs of thetime; eventually they will have tochange or become more easy-going,that is, become a little different.It is against such a background that wecan take the measure of Beethoven’s decisionin 1821–24 to return to his old idea ofsetting Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” and to presentit, not as a solo song to be heard in theprivate salons of music lovers but as ananthem that could be performed on thegrandest possible scale in the concert hall,the most public of settings. His furtherplan, to make that melody the climax of agreat symphony, distantly recalls Haydn’suse of his famous patriotic hymn, “Gotterhalte Franz den Kaiser,” as a slow movementwith variations in his C Major QuartetOpus 76 No. 3, composed in 1797 justa few months after he had written theanthem itself. Beethoven, in this new symphonythat would have Schiller’s “Ode” ascenterpiece, meant to leave to posterity apublic monument of his liberal beliefs. Hisdecision to fashion a great work thatwould convey the poet’s utopian vision ofhuman brotherhood is a statement of supportfor the principles of democracy at atime when direct political action on behalfof such principles was difficult and dangerous.It enabled him to realize in his waywhat Shelley meant when he called poetsthe “unacknowledged legislators of theworld.”CHANGING VIEWS OF THENINTHThe Ninth Symphony, of all Beethoven’sworks, has had the broadest impact andthe widest range of interpretations. FromBeethoven’s time to ours, generations ofcommentators, musicians, artists, and criticshave stepped forward to give voice totheir interpretations, many of them focusingonly on the “Ode” rather than on thesymphony as a whole. Very few haveexplored what may seem to some critics inThe “Ode to Joy” from the Ninth Symphony being sung at Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate for the worldwideopening of the 1998 Winter Olympics.our time the historicizing and anachronisticquestion of what it was, or could havebeen, that Beethoven himself intended thiswork to mean and to express.The interpretive trend began effectivelywith Wagner, whose entire career was conditionedby his fascination with the Ninth:in his early years he copied the entire score,arranged it for piano, performed it manytimes, restored some passages, and claimedit as the starting point of his lifetime aestheticmission to equal and surpassBeethoven by reshaping opera along symphoniclines into music-drama. AsBeethoven transformed the symphony andspoke to the world by combining instrumentalmusic with words, Wagner wouldreshape culture, especially German culture,by means of music-drama based on nationalmyths.In My Life, Wagner writes that he wasimpelled by the “mystical influence ofBeethoven’s Ninth Symphony to plumbthe deepest recesses of music.” Onanother front, every German composerof symphonies after Beethoven, fromMendelssohn and Schumann to Brahms,Bruckner, and Mahler, understood that theNinth had come to be a central bulwark ofmusical experience that each would haveto confront in carving out a personal pathas a symphonist. In fact each composeralso confronted the Ninth in individualworks, whether by the choice of key orscale, by the use of solo and choral voices,or by thematic content. Schumann, forexample, who worshipped Beethoven likeSchumann’s friend Henriette Voigt andportrayed by Schumann as an enthusiasticcommon listener, as saying about theNinth as a monumental experience, “I amthe blind man who is standing before theStrasbourg Cathedral, who hears its bellsbut cannot see the entrance.”Worship of Beethoven, above all thesymphonies, was rampant in the more conservative19th-century centers of Americanmusical culture. The Ninth, which hadreceived its first London performance in1825, was given its American premierein New York in 1846 by the recentlyfounded New York Philharmonic Society.In Boston, Brahmins and transcendentalistsalike acclaimed Beethoven as a godlikefigure (said Margaret Fuller, “the mind islarge that can contain a Beethoven”). Amajor purpose in founding the BostonSymphony Orchestra in the 1880s, in additionto rivaling New York, was to makepossible the performance of Beethoven’ssymphonies, with the Ninth as the capstoneof the great tradition. Though otherWestern musical traditions, especially inthe earlier twentieth century, were lessenthralled with the Beethoven symphonies,especially the Ninth, as these works recededfurther into the past, still the power ofmass media and the message of brotherhoodin the finale continued to make theNinth a natural symbol at great politicalevents celebrating freedom, as at the concertled by Leonard Bernstein on December25, 1989, celebrating the tearing down ofa god, quotes Karl Voigt, the husband of continued on page 12Associated PressColloquy 7 Fall 2003

<strong>Saving</strong> <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong>continued from page 3mental and evolutionary factors that affectit—not only for the sake of orangutans butalso for furthering knowledge of humanevolution.She recently discovered a “really interestingphenomenon” that could affect thetiming of male development in orangutans.Among orangutans, there are two “types”of males: a big male with large cheek padsand a smaller one without cheek pads.“Both are reproductively mature, but theirbehavior is quite different,” she says.To find out what makes them different,<strong>Knott</strong> is investigating a combination ofnutritional and social factors that maydetermine when males develop. Scientists,she says, do not know yet whether “allmales eventually develop [into big males] ifthey live long enough, and whether thereare some that are 50 years old and neverdeveloped.”The phenomenon of the “two types” isextremely rare among mammals, <strong>Knott</strong>says. “There have been times in zoos wherethey remove the big males and the smallermales develop,” she says. “So zoos havethought it was some kind of suppression.The problem is, in the wild these guys aresolitary—they don’t run into each other. Sothey’re probably not having a suppressiveeffect.“I’ve looked at testosterone levels in themales, and [it’s much higher in] the bigmales than the smaller males,” she continues.“But the interesting thing is that we’vediscovered these big males will only stay inthis ‘big’ stage for a fairly brief period.They can’t sustain it; they shrink. And thesmaller males do reproduce, so they’re notreally sub-adults.”<strong>Knott</strong> described what happened to oneof the big males in her study over a year’stime. “He went through this period of reallyintensive mating, but then the cheekpads started to diminish. His whole bodysize and his demeanor totally changed. Hestopped producing these long calls theymake. He stopped mating,” <strong>Knott</strong> says.“If a male can only maintain this ‘prime’form for a brief period, then the smallermales should wait until conditions arevariable, both nutritionally and possiblysocially, before they develop,” she adds.“This may be why you see this delayeddevelopment in some males.” <strong>Knott</strong> also isinvestigating whether these “past-primes”may revert back to being prime males.In terms of nutrition, reproduction isdirectly related to the orangutans’ abilityto get adequate calories. During <strong>Knott</strong>’sPhD work, she discovered that hormonallevels in females are lowest during periodswhen fruit—orangutans’ main foodsource—is least available. Levels rise whenfruit production and consumptionincrease, which is when matings and conceptionsoccur more often. During periodswhen fruit is scarce, orangutans’ (whoweigh from around 100 to more than 200pounds) caloric intake can be less than1,500 calories per day.The discovery that large males can’tA baby orangutan looks into Tim Laman’s camera as it makes its way with its mother through thecanopy of <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong> National Park.retain their prime condition forever, asthey do in zoos, may also be related tonutrition. “They can’t seem to maintain[being a ‘prime male’] for very long—it isvery expensive, energetically,” <strong>Knott</strong> says.“There are a lot of questions we haven’tanswered yet. You really want to studyapes over a lifespan … to see what’s reallyhappening—to see the birth interval, to seewhat really controls reproduction, tounderstand juvenile development.”<strong>Knott</strong> and her team are also using GISand GPS (satellite) monitoring to studyorangutan travel patterns over large areas.“An individual, especially a male, willcome in our area, then disappear, and we’llsee him maybe a year later,” <strong>Knott</strong> says. “Iwant to start long-term overnight follows.Right now we follow them maybe a couplehours out of the study trail system. Thenthey get too far away, and we have to letthem go. We want to camp in the forestand keep following them, really track themto see how far they’re traveling. That’s alsoimportant for conservation too—to seehow big of an area they use.”EXPANDING THEACADEMIC DOMAINAlthough <strong>Knott</strong> is a biological anthropologist(one of her advisors was GSAS DeanPeter T. Ellison), she has come to realizethat she and her husband Laman, a fieldbiologist, can no longer conduct scientificresearch without being involved in conservation.It’s become a critical part of theirscientific work.“Almost every field biologist I knowusually has some kind of conservationcomponent to their work. We can nolonger go into these areas and just do ourown thing with no one bothering us,” shesays. “Local people expect us to be muchmore accountable, to explain what we’redoing there, explain how it benefits them.So it’s interesting. You can no longer justdo the pure research.”Laman, who worked as a research assistantstudying interactions among plantsand animals in the <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong>National Park even before he became aHarvard graduate student, remembers howit used to be.“I first went there over 15 years ago,”he says. “Even the park was surrounded byall these [relatively] undisturbed forests. Itwas a huge wilderness area. You felt likeyou were going into the middle ofHarvard University8GSAS

A “prime” male orangutan (left) in <strong>Knott</strong>’s study, compared with a “past-prime” male, sans colossalcheekpads and aggressive attitude.nowhere. I guess I imagined it was alwaysgoing to be like that. But in the last 15years there’s been an incredible amount ofdevelopment in Indonesia. In areas aroundthe park, the population’s been going up as[people] are moving in from Java. They’rejust cutting down the forests and converting[the land] to agriculture.”In 1997, <strong>Knott</strong> and her team establishedthe <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong> OrangutanConservation Project to help preserve thepark and its unique species of animals,bird, and plant life—and to make it possiblefor academic work to continue. Theproject sponsors a staff of about ten fieldassistants and local people and conductsawareness campaigns in the region andenvironmental education in its school systems.They also have a billboard campaign,a weekly radio program, and regularpublic meetings that can attract hundredsof people.“There’ll be a village moderator, aranger, field assistants. Often they can bekind of contentious because you mighthave illegal loggers come in, so we talkabout what we’re doing,” <strong>Knott</strong> says.“[People] wonder, ‘What are theresearchers doing up there?’”The project also hosts field trips for highschool students. “Most of these kids live inthe local villages, but they’ve never seen awild orangutan, and they’ve never been tothe rain forest even though they live a fewminutes from [it],” <strong>Knott</strong> says. “They stayfor about three days and take data, learnabout what we do, practice beingresearchers.”Knowing that many of these people areinvolved in illegal logging and the illegalpet trade, educating area parents and otheradults is another challenge the Harvardgroup has taken on. Some villagers do recognizethe value of medicines found inrainforests, <strong>Knott</strong> says. They also see thatmuch of the world’s oxygen is generated inrainforests and that without them globalrain patterns will be disrupted. The biologicaldiversity argument can also have animpact. But, she says, “those argumentsdon’t always resonate at the village level,especially among the people doing the logging,most of whom are farmers.”One argument that does resonate is protectionof the <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong> watershed.“We explain that the water they’re gettingcomes down from the mountain and that ifyou destroy the rainforest, you’re going todestroy your water source,” <strong>Knott</strong> says.<strong>Knott</strong>’s group has also developed a“pride campaign” to encourage locals tovalue the wildlife that is uniquelyIndonesian.“Orangutans are only found in Borneoand Sumatra. Proboscis monkeys are onlyin Borneo,” she says. Local children participatein art-related programs like playsand coloring contests. But even these,<strong>Knott</strong> explains, are “mostly targetingparents.”In one coloring contest, children madepictures of orangutans for a billboard.“When a billboard was revealed showingwhat orangutans really looked like, everyonewas shocked to see that they wereorange. They didn’t even know,” she says.“These kids live right there [by the forest],but they have less knowledge of what anorangutan is than a kid in Somerville does.There’s no environmental education.”But the logging of the habitat is what’skilling the park and the orangutans. Inaddition to the awareness and educationcampaigns, <strong>Knott</strong>’s group also targets theirefforts towards the local people who areillegally logging. “Sometimes you go andfind out that [one of the loggers] is so-andso’slittle brother who works for me,” shesays. “These are local people, who say[they’re] just looking for food, which issort of true, but sort of not…”The money the loggers make is, even byvillage standards, not great, compared towhat is being taken away. “Basically, theforest is being cut down for peanuts—thelocal people are not making much moneyoff of this,” <strong>Knott</strong> says. “A rich businessmanwill support a team to do some illegallogging. He’ll give them money up front,so they’re constantly in debt to this person.These local guys are being exploited by themiddlemen.”The logging itself is also extremely dangerous.Trees are felled and local menstand astride the trunks. Holding chainsawblades between their bare feet, they walkbackwards and cut the tree into sections.The “milled” wood is dragged out of theforest on wooden sleds.A TENUOUS FUTUREOnce the forest is gone, the orangutanswill die. <strong>Knott</strong> and Laman try to be hopefulthat it won’t reach that point. But it’sclearly painful for them, knowing that it’spossible their long-time study site mayvanish along with the park and theiropportunities for studying wildlife in itsnatural habitat.“It doesn’t do any good to say, ‘Oh,we’re saving some of the Amazon, so wedon’t need to save Borneo,’” Laman says.“It’s a different rainforest. Every single differentregion of the world—whether it’sAfrican rainforest, South American rainforest,or Southeast Asian rainforest—hasa totally different species composition ofplants and animals. In Borneo, you’ve gotorangutans and hornbills; in SouthAmerica, you’ve got sloths and macawsand jaguars. They’re all rainforests, butthey’re all very different rainforests. So youwant to save all of these places, or at leastparts of them.”<strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong> still harbors a multitudeof amazing wildlife. “If we can get theseareas protected for future generations, thisis the time to do it, not ten years fromnow—ten years from now it’s going to betoo late,” Laman says.“There’ve been some good signs recentlywith the national government takingcontinued on next pageColloquy 9 Fall 2003

<strong>Saving</strong> <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong>continued from previous pagesome action,” <strong>Knott</strong> adds. “But [the studysite is] in danger of being shut down. Thereare only about three orangutan researchsites in the world now.” Others have beenclosed, either because there is too little forestleft, or because the presence of loggersmakes it impossible—and dangerous—towork.Congress has helped by passing theGreat Ape Conservation Act, signed intolaw in 2000. It provides about $5 million ayear to support the conservation and protectionof great apes by giving grants tolocal wildlife management authorities andother organizations involved in the effortto protect the animals and their habitat.<strong>Knott</strong>’s organization in <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong> hasreceived support from this fund, and sheurges people to contact their Congressmember about continuing or even increasingsupport.Consumers can also buy “environmentallycertified wood,” which lets themknow that the wood they’re buying did notcome from rainforests. Woods like Asianmahogany and lauan (used in inexpensiveplywood) are among the many types foundin Indonesian rainforests.“A lot of the public outcry does helppressure the Indonesian officials at thenational level to take action,” <strong>Knott</strong> says.The <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong> Orangutan ConservationProject put up a petition on its Websiteand received about 8,000 signaturesworldwide to stop illegal logging in thepark.“I think things like that do have animpact,” <strong>Knott</strong> says. “[It] could pressureour leaders to pressure other national governmentsas a condition of internationalaid, for example, to protect forests, toshow they’re really doing something.“The orangutan may be the first greatape to go extinct in the wild,” <strong>Knott</strong> says.“Their trajectory for extinction is greaterthan for chimps or gorillas—they’re themost threatened. You figure 80 percent oforangutan habitat has been lost in the last20 years. It’s just totally shocking that thegreat apes could become extinct.”For more information on the <strong>Gunung</strong> <strong>Palung</strong> NationalPark, go to www.fas.harvard.edu/~gporang.<strong>Knott</strong> and Laman’s fieldwork is good,important, even noble, but it’s definitely noteasy.“You wake up usually at around 3:30a.m.,” says <strong>Knott</strong>. “You need to get to thenest when the orangutan wakes up,[around] 5 a.m. That involves getting therein the dark, so maybe you have to travel foran hour in the forest in the dark, then youfollow them all day till they make a nest atnight.You’re on the ground, watching themup in the trees. Some days they don’t govery far, and it’s really easy. But other days… we’re on the side of a mountain.You’realso often carrying all your gear. So, it’s challenging.You’re running after them, and inthe swamp area you might be up to yourknees in water. When you’re looking forthem it’s better if you can walk fast. It’s definitelyphysical, but it’s not grueling.”Orangutans are arboreal creatures—they live in treetops, in what is called therainforest canopy. So Laman spends muchof his time harnessed to a 200-feet tall tree(higher than the Peabody Museum, to rein-Human Subjects / Humane Researchcontinued from page 5Because she was going to be workingwith human subjects, Hooley soughtapproval from the Committee on the Useof Human Subjects.“Professor Hooley first ran a pilot studywith only six healthy women with no historyof depression,” recounts Calhoun.“Next she tried the same procedure withwomen who had recovered from anepisode of depression. Only then did sheapply to do the study with depressedwomen. Thus, she and the committee [onthe Use of Human Subjects] had quite a bitof information to go on in evaluating possiblerisks to the women. At that point, thecommittee asked for a number of changesand additions. For instance, only womenwho had previously told their mothers oftheir depression could participate and nofreshmen could participate. ProfessorHooley was asked to provide volunteers aLife in the Fieldtroduce an earlier marker) with 30 poundsof equipment in a backpack, watching thewildlife. It’s not hard to see why he wouldbring back amazing photographs, along withbiological data—few people have the staminaor academic background for this kind ofwork.Occasionally, big males will come downto the ground and chase people, though<strong>Knott</strong> and Laman have never been chased.There are other dangers, though.“I’ve been pretty lucky,” <strong>Knott</strong> says.“Butthere’s malaria, Dengue fever, giardia. I hadone student who was hit by a tree branchand it opened her scalp up. She had to besewn up. Someone broke [a] foot oncejumping in the river.There are various accidentsand diseases that you can take medicinefor—although not for Dengue fever.But if you have enough DEET (an insectrepellant) on, you can protect yourself frommosquitoes.”As Laman dryly says, “There’s definitelyan adventure component.”more extensive explanation of the imagingprocess that would be used; to explain tothe mothers as well as the daughters thatthe daughters might become upset whileparticipating and what would be done tohelp them.”This example, Calhoun says, demonstratesthe collaboration between an investigatorand the IRB, which “provided ideasabout some additional measures that couldfurther minimize the risk that anyonewould be upset or harmed by the experienceof participating as a research subject.”Hooley’s research—which was approvedby the IRB—involves playing taped messagesboth of criticism and praise to hersubjects while watching brain activity withthe help of MRI (magnetic resonanceimaging). The goal is to determine if thecontinued on next pageHarvard University10GSAS

Human Subjects / Humane Researchcontinued from previous pagePsychology Professor Jill Hooley studies brainactivity of human subjects suffering from clinicaldepression.brain behaves differently in response tocriticism or praise in subjects with no historyof depression than it does in subjectsdiagnosed with the illness.Hooley has found that, among emotionallyhealthy participants, certain areas ofthe prefrontal cortex of the brain becomeengaged to process criticism. However,with subjects who have recovered fromdepression, she says, “that area almostseems to be going off-line. There is adecrease in blood flow to the dorsolateralprefrontal cortex in the recovereddepressed, while there is an increase ofblood flow to that area in the emotionallyhealthy [subjects].”The research follows an original protocol.Her subjects are asked to speak withtheir mothers about the research and invitethem to participate. They are not told whatsorts of remarks will be expressed by theirmothers, although subjects are aware thatsome remarks may be positive and somemay be negative. “Especially harsh criticism,”is not used, Hooley notes.“We try to calibrate the intensity of thecritical remarks to ensure that subjects willnot be exposed to anything too upsettingor out of the ordinary,” she adds.“We also make sure that mothers arecriticizing things about their children thattheir children already know about. Inother words, we try to ensure that this isnot the first time the participant will haveheard his or her mother complain aboutthat particular aspect of his or her behavior,”she says. Participating mothers areaware they are being taped and that thesetapes will be played to their children.Hooley points out that “positive consequences”emerged from her study’s effortsSusan Gilbertto conduct research “with the utmostrespect for the participants.” In particular,she says, no subjects “were distressed byour procedures” and most said “theyfound their participation in the study bothfascinating and enjoyable. Many were alsoquite moved to hear the praising commentsfrom their mothers. In no case was anyfriction between mothers and daughterscaused by our procedures.”OUT OF BALANCE?According to a September 2000 article,“Don’t Talk to the Humans: TheCrackdown on Social Science Research,”in Lingua Franca (the now-defunct magazineof academic life), between 1998 and2000, the NIH suspended or shut downresearch programs at eight different institutionsacross the country for violationsranging from inadequate record-keeping to“a failure to review projects that shouldhave been vetted.”These actions have led to an increasedvigilance by IRBs and have spawned adebate questioning the usefulness of theseregulations. Are these ethical codes effective,or do they perhaps deter the ethicalresearcher by setting up an intellectualroadblock?“The issue is boiling over for a varietyof reasons,” says Nicholas Christakis, professorof medical sociology at HarvardMedical School. “It is definitely the casethat there is more and more scrutiny comingfrom IRBs. I support the ethical conductof human research and I support thereview of that research, but I think thatwhat has happened is that there has been aloss of perspective about what the realrisks in human research are.”“There is a balance between the IRB’sjob and the furthering of science andknowledge,” Jill Hooley says. “The paperworkwe have to give to subjects is gettingmore and more detailed. I know some participantslook at this and say, ‘What areyou doing here? I thought you were justgiving me questionnaires?’ So how can webest incorporate good principles of lookingafter human subjects and still do theresearch that we want to do?“My view as a scientist is that I don’twant to do research that I wouldn’t be aparticipant in myself,” Hooley says.“That’s my yardstick.”For more information about HarvardIRBs, including the official FAS policystatement on ethical research, and links tosome research reports and federal guidelinesmentioned in this article, please go towww.fas.harvard.edu/~research/humsub.html.Janine Brunell Looker is a freelance writer living in Newburyport,Massachusetts.Help Graduate StudentsLaunch their CareersGSAS and the Office of Career Services(OCS) invite you to help us assist graduatestudents interested in academic andnon-academic career opportunities.Whether exploring options during theirstudies or looking for jobs at graduation,GSAS students can benefit from youradvice and support.Here are some ways to volunteer:☛ Register to be a career adviser throughThe Professional Connection, theonline networking database☛ Advertise your internships andemployment positions through OCS’sMonsterTrak job-listing service☛ Be a panelist for GSAS and OCSCareer Options Day☛ Participate in the GSAS/OCSAlternative Careers Fair☛ Organize career-related events forstudents and alumni through your localHarvard Club☛ Participate as an employer in OCS’son-campus recruiting program… Or share your own ideas with OCS.Toget involved, contact Robin Mount, PhD,director of GSAS Career Services andassociate director of OCS, at 54 DunsterStreet, Cambridge, MA 02138; (617) 496-8957; e-mail: ocs@harvard.edu.Colloquy 11 Fall 2003

news and notes … news and notes … news andGSAS ALUMNUS ABIZAID INCHARGE IN IRAQLt. Gen. John Abizaid,AM ’81, Middle Eaststudies, took over USCentral Command inIraq in July 2003. Hisdecorations include theDistinguished ServiceMedal, the Legion ofMerit with five Oak LeafClusters, and the BronzeLt. Gen. John AbizaidStar. He is a graduate ofWest Point and commanded divisions in toursin Bosnia, Kosovo, and the Persian Gulf War.Courtesy of KRTHARVARD CHEMIST WINS KYOTOPRIZEIn June 2003, George Whitesides, MallinckrodtProfessor of Chemistry, was named awinner of the 19th Annual Kyoto Prize. Theprizes, sponsored by theInamori Foundation,Professor GeorgeWhitesidesHarvard News Officehonor “the pursuit ofpeace and betterment ofsociety through a balanceof technology andhumanity.”Whitesides is a pioneerin the field ofbioengineering and isengaged in the emergingfield of nanotechnology.Laureates will receive a diploma, a Kyoto PrizeMedal, and approximately $400,000 at a ceremonyto be held in Japan in November 2003.PRIESTLEY MEDAL TOCHEMISTRY’S COREYE.J. Corey, Sheldon Emery Professor ofChemistry, will receive the 2004 PriestleyMedal for Distinguished Service to Chemistry,the highest honor presented by the AmericanChemical Society. Corey, who has been on theHarvard faculty since 1959, won the NobelPrize in Chemistry in 1990.He is best known for developing theprocess of retrosynthetic analysis, used tomanufacture synthetic cellular “targets” foruse in chemical and biological research.Corey’s later work has focused on creatinganti-cancer compounds and on the use ofcomputers in organic chemistry.BIOLOGIST COLLIER HONOREDFOR WORK IN INFECTIOUSDISEASES RESEARCHJohn Collier, PhD ’64, cellular and developmentalbiology, won the annual Bristol-Myers Squibb Award for DistinguishedAchievement in InfectiousDiseases Researchin July 2003. Collier,Maude and LillianPresley Professor ofMicrobiology and MolecularGenetics atHarvard Medical School,was recognized for“contributions to ourProfessor John Collierunderstanding of themolecular mechanisms by which bacteriacause disease,” according to a HarvardMedical School statement.Collier, a Harvard faculty member since1984, is an authority on anthrax and otherbiological toxins; he has also shown howimmunotoxins may fight cancer. The awardbrings a $50,000 cash prize and a commemorativemedallion.Professor StanleyHoffmannPam MurrayJane Reed/ Harvard News Office2003 EUSA LIFETIMECONTRIBUTION AWARD TOHOFFMANNThe European Union Studies Association(EUSA) awarded its 2003 LifetimeContribution Award in EU Studies to StanleyHoffmann, Paul andCatherine ButtenwieserUniversity Professor inHarvard’s governmentdepartment.“Without Hoffmann’swisdom and science,Europeans and Americanswould not knowand understand eachother nearly as well asthey now do,” said MartinA. Schain, EUSA chair, in a statement. Hoffmann’smost recent book is World Disorders:Troubled Peace in the Post–Cold War Era (Rowman& Littlefield, 1998).PEN USA LITERARY AWARDRECOGNIZES ALUMNUS ELLSBERGThe book Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam andthe Pentagon Papers (Viking, 2002) byDaniel Ellsberg, AB ’52, PhD ’63, economics,won the PEN USA prizefor creative nonfiction inJuly 2003. PEN USA honors“outstanding workspublished or produced bywriters living in the westernUnited States.” In thebook, Ellsberg recountshis transformation froman early-1960s ColdDaniel EllsbergWarrior governmentanalyst to the anti-war activist who leaked thePentagon Papers to the New York Times in 1971.Jock McDonaldRADCLIFFE FELLOWSANNOUNCEDThe Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studywill sponsor 56 fellows for 2003–04,selected from more than 700 applicants.Among the new fellows is Caroline Elkins,PhD ’01, history, and assistant professor ofhistory at Harvard. Professor Elkins will writea book on the Mau Mau crisis, the 1950s anticolonialrebellion in Kenya.Katharine Park, PhD ’81, history of science,Samuel Zemurray Jr. and Doris ZemurrayStone Radcliffe Professor of the History ofScience and of Women's Studies at Harvard,will complete her book Visible Women: Gender,Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection.Harvard Professor of Government JenniferHochschild will write on Madison’s vision ofAmerica and how identity politics informedthat vision. Susan Moller Okin, PhD ’75, government,Marta Sutton Weeks Professor ofEthics in Society in the Stanford UniversityDepartment of Political Science, will studyhow “neglect of gender in economic development… has distorted and retarded the promotionof women’s human rights in recentdecades.”Colloquy 13 Fall 2003

ALUMNI BOOKSThe Hanging of EphraimWheeler:A Story of Rape, Incest,and Justice in Early AmericaBy Irene Quenzler Brown, PhD ’69,history, and Richard D. Brown, PhD’65, historyHarvard University Press, 2003, 388 pp.The Browns delivera novelistic accountof the patheticcircumstances surroundingthe trialand execution of afailed Massachusettsfarmer. Alongthe way they offerinsights into evolvingAmerican attitudes toward race andinterracial marriage, crime and punishment,and the justice system. RichardBrown, co-author of Massachusetts: AConcise History (Massachusetts, 2000)and other books on colonial Americanhistory, is Board of Trustees DistinguishedProfessor of History at theUniversity of Connecticut, where IreneBrown is associate professor of familystudies.Christ’s Passion, Our Passions:Reflections on the Seven LastWords from the CrossBy Margaret Bullitt-Jonas, PhD ’84,comparative literatureCowley Publications, 2003, 104 pp.These sermons by Bullitt-Jonas, a priestassociateat All Saints’ Episcopal Churchin Brookline, Mass., are meditations onthe last “words” (in fact, the last sevensentences) Christ spoke as he was dying.Included are suggestions for prayerfulapproaches to each sentence in the questfor a more vital spiritual life. The authorof Holy Hunger: A Memoir of Desire(Vintage, 2000), Bullitt-Jonas served forseveral years as a chaplain to the Houseof Bishops of the Episcopal Church.Changing the World:AmericanProgressives in War andRevolution, 1914–1924By Alan Dawley, PhD ’71, historyPrinceton University Press, 2003, 409 pp.World War I and anexpanding Americanempire, particularlyin Latin America,compelled 20th-centuryprogressives tobroaden their reformefforts from thedomestic arena to theinternational stage,writes Dawley. A professor of history atthe College of New Jersey, Dawley is alsothe author of Class and Community: TheIndustrial Revolution in Lynn (Harvard,1976), winner of the Bancroft Prize; andStruggles for Justice: Social Responsibilityand the Liberal State (Belknap, 1991).Faith-Based Diplomacy:TrumpingRealpolitikEdited by Douglas Johnston, MPA ’67,PhD ’82, governmentOxford University Press, 2003, 296 pp.The terrorist attacksof September 11,2001, showed religiousextremism takento violent and widespreadends. Theattacks also showedwhy considerationsof faith should bepart of any Westernforeign policy equation, writes Johnston.He and his fellow contributors proposeways politicians and activists can channelthe “enthusiasm of faith” into governmentalpeacemaking efforts. Johnston is alsoco-editor of Religion, the Missing Dimensionof Statecraft (Oxford, 1994) and is thefounding president of the InternationalCenter for Religion and Diplomacy inWashington, DC.Hunting Down the Monk: PoemsBy Adrie Kusserow, MTS ’90, PhD ’96,anthropologyBoa Editions, 2002, 104 pp.Most of these poemsaddress a Westerner’ssearch for spiritualsatisfaction in thereligions of the East;others explore, withmoving clarity, thedeeply felt experiencesof childhood,loss, and the death ofa parent. The author is professor ofanthropology at St. Michael’s College.Nationalizing the Russian Empire:The Campaign Against EnemyAliens During World War IBy Eric Lohr, PhD ’99, historyHarvard University Press, 2003, 237 pp.During times of war,nationalism tends toescalate. Lohr tellsthe grim story of howRussia’s nationalismmanifested itself duringWorld War I withthe wholesale deportationsof Jewish,Muslim, Germanborn,and other “enemy” citizens. Thisforced emigration of about one millionpeople directly contributed to the tensionsthat erupted in the 1917 upheaval, writesLohr. The author is assistant professor ofhistory at Harvard and co-editor of TheMilitary and Society in Russia, 1450–1917(Brill, 2002).Gambling Life: Dealing inContingency in a Greek CityBy Thomas M. Malaby, AB ’90, PhD ’98,anthropologyUniversity of Illinois Press, 2003, 157 pp.In this highly readable ethnography, Malabyshows how gambling—with its culturegrounded in an acceptance of risk andreliance on luck and hope—has permeatedHarvard University14GSAS

the economy andsocial life of onesmall community onthe island of Crete.The author is assistantprofessor ofanthropology at theUniversity of Wisconsinat Milwaukeeand has published inAnthropological Quarterly, Social Analysis,and other journals.Helen Hunt Jackson:A Literary LifeBy Kate Phillips, PhD ’97, history ofAmerican civilizationUniversity of California Press, 2003, 380 pp.Phillips, author ofthe acclaimed novelWhite Rabbit (HoughtonMifflin, 1996),turns to literaryscholarship in thisaccount of the lifeof Helen Hunt Jackson,the subject ofPhillips’s doctoraldissertation. Jackson—best known for hernovel Ramona, a plea for racial justice inthe American West, and for her work onbehalf of Native American rights—is presentedhere as emblematic of the trials andtriumphs of late-19th-century intellectualwomen.Hollywood’s White House:TheAmerican Presidency in Film andHistoryEdited by Peter C. Rollins, AB ’63, PhD’72, history of American civilizationUniversity Press of Kentucky, 2003, 464 pp.On-screen AmericanPresidents, writeseditor Rollins, haveserved as “ourrepresentative men,”reflecting society’sshifting views of themen in the OvalOffice, from DarrylZanuck’s worshipfulWilson (1944) to Oliver Stone’s psychodramaNixon (1995). Rollins, RegentsProfessor of English at Oklahoma StateUniversity, is co-editor of Hollywood asHistorian: American Film in a CulturalContext (Kentucky, 1983) and editor ofthe journal Film & History.Lyndon Johnson and Europe: In theShadow of VietnamBy Thomas Alan Schwartz, PhD ’85,historyHarvard University Press, 2003, 339 pp.To many, LyndonJohnson was the classic“ugly American,”a perception basedlargely on his diplomaticperformanceduring the VietnamWar. Schwartz, anassociate professor ofhistory at VanderbiltUniversity, sets out to correct that perceptionwith this “more dispassionate assessment”of Johnson’s foreign policy. He citesJohnson’s efforts toward nuclear non-proliferationand his early pursuit of détentewith the Soviets as just two examples ofLBJ’s previously unheralded diplomaticsuccesses. Schwartz is also the author ofAmerica’s Germany: John J. McCloy andthe Federal Republic of Germany(Harvard, 1991).Averting “The Final Failure”: JohnF. Kennedy and the Secret CubanMissile Crisis MeetingsBy Sheldon M. Stern, PhD ’70, historyStanford University Press, 2003, 449 pp.Since their declassificationin 1997, thetapes of PresidentKennedy’s ExecutiveCommittee meetingshave been poredover by numeroushistorians, includingHarvard’s Ernest R.May, co-author ofThe Kennedy Tapes: Inside the WhiteHouse During the Cuban Missile Crisis(Belknap, 1997), and considered the “official”transcription. The Ex Comm, as itwas known, comprised the President,Attorney General Robert Kennedy,Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, anda handful of others in the President’sinner circle, who navigated the 13 daysknown as the Cuban Missile Crisis.Where previous books have presentedmore or less straight transcriptions,Stern has created a narrative version thatbrings the human element to the ExComm meetings. Stern also presents anextensive appendix in which he outlinesmore than 100 differences with the officialtranscripts he found in listening tothe tapes. In some cases, Stern presentsnew versions of historic conversationsand moments in the crisis. Sheldon Sternwas the historian at the Kennedy PresidentialLibrary from 1977 to 1999.House by House, Block by Block:The Rebirth of America's InnerCitiesBy Alexander von Hoffman, PhD ’86,historyOxford University Press, 2003, 320 pp.Von Hoffman, a senior research fellowat Harvard’s Joint Center for HousingStudies, describes how grassroots groupsand small businesses—aided mightily byvarious tax incentives and governmentsubsidies—combined to revitalize theSouth Bronx, South Central Los Angeles,and other downtrodden neighborhoodsin Boston, Chicago, and Atlanta. VonHoffman is also the author of LocalAttachments: The Making of anAmerican Urban Neighborhood (JohnsHopkins, 1994) and has written for theBoston Globe, Atlantic Monthly, andother publications.Authors: GSAS alumni who havepublished a new book within thepast year and would like it to beconsidered for inclusion in AlumniBooks should send a copy to: Colloquy,Harvard Graduate School of Arts andSciences, Byerly Hall 300, 8 GardenStreet, Cambridge, MA 02138-3654.Colloquy 15 Fall 2003

The Ninth Symphonycontinued from page 12Among recent interpretations that doexhibit interest in the historical context ofthe work is one that sees the Ninth in thecontext of “political Romanticism,” a termthat refers to a putative synthesis of Schillerianoptimism about humanity’s aspirationsto freedom and joy, and to thepost-Enlightenment Romantic aestheticsof writers such as E.T.A. Hoffmann. Thisview perceives a steady progression throughseveral of Beethoven’s major works, whichare seen first and foremost as vehicles ofpolitical philosophical thought, emergingin the Eroica as a musical translation of the“universal history,” that is, the idea of the“education … of humanity from aninstinctual harmony with nature to a stateof rational, civilized freedom.” SincePrometheus was manifestly devoted toshowing the triumph of education and civilizationover the state of nature, the parallelfits to some degree. Certainly it isplausible that in the Eroica “we behold thefiercest rays of the French Revolutionrefracted through the cooling ether of Germanidealism.” The progression is not presentedas a steady one, in which the Ninthwas simply the end product of a consecutiveseries of enlightened statements abouthuman progress and brotherhood. Quitethe contrary: by the time of the Ninth, themanifest abandonment of Enlightenmentideals by all post-1789 regimes from the1790s to the 1820s—first the Terror andits adversaries, then Napoleon and hisadversaries, then the newly victoriousautocratic governments—led to politicalstasis and retrenchment. The light hadfailed.But the situation was more drastic thanthis viewpoint proposes. The Ninth, in myview, was written to revive a lost idealism.It was a strong political statement made ata time when the practical possibilities ofrealizing Schiller’s ideals of universalbrotherhood had been virtually extinguishedby the post-Napoleonic regimes.Beethoven’s decision to complete the workwas thus intended to right the balance, tosend a message of hope to the future, andto proclaim that message to the world.Alumni Hales, McCullagh, and Sangines-Krause Join GSAA CouncilBy Paula SzocikIn July 2003, three GSAS alumni were namedto serve on the Graduate School AlumniAssociation (GSAA) Council, a 40-memberboard focusing on such issues as graduatescholarship, financial aid, student life, globaloutreach, and alumni careers. Council membersserve three-year terms.R. STANTON HALESR. Stanton Hales, PhD ’70, mathematics, ispresident of The College of Wooster in Ohio.From 1990 to 1995, hewas vice president foracademic affairs andprofessor of mathematicalsciences. Prior tohis appointment atWooster, Hales wasassociate dean of theCollege and professor ofmathematics at PomonaR. Stanton HalesCollege, where hereceived the Rudolph J. Wig DistinguishedProfessorship Award. He has served as consultantto the Federal Home Loan Bank Boardand the California <strong>Saving</strong>s and LoanCommission.SUZANNE FOLDS MCCULLAGHSuzanne Folds McCullagh, PhD ’81, fine arts, isAnne Vogt Fuller and Marion Titus SearleCurator of Earlier Printsand Drawings at the ArtInstitute of Chicago. Shehas been a member ofthe curatorial staff ofthat department since1975. Her specialty isin French and ItalianRenaissance and Baroqueprints and drawings.Suzanne FoldsAuthor of numerousMcCullagharticles and exhibitioncatalogues, including Italian Drawings Before1600 in The Art Institute of Chicago (1979), ascholarly collection catalogue of over 700drawings. She is active as a director of theHarvard Club of Chicago and also serveson the board of the College of theAtlantic, among other educational and civicinstitutions.ALLEN SANGINES-KRAUSEAllen Sangines-Krause, PhD ’87, economics,is a managing director and co-head ofthe General IndustrialsGroups with GoldmanSachs International inLondon. He taught graduateand undergraduatecourses at the InstitutoTecnológico Autónomode México and has beena guest lecturer at theSaid Business School,Allen Sangines-KrauseOxford University.A FOND FAREWELLWe say farewell to the following GSAS alumniwho have concluded their terms as Councilmembers: John Armstrong, AB ’56, PhD ’61,applied sciences; Michael A. Cooper, PhD ’91,English and American literature and language;Gerard Fergerson, PhD ’94, history of science;Richard Nenneman, AB ’51, AM ’53, government;and Wallace P. Wormley, PhD ’76, psychology.We thank them for their years ofservice to the Graduate School.For a complete list of GSAA Council members,go to www.gsas.harvard.edu/alumni/members.html.Paula Szocik is director of alumni relations and publications at theGraduate School of Arts and Sciences.FOR THE FUTURE…It’s easy to include theGraduate School of Arts andSciences in your estate planand to provide support for afellowship, a specific program,or a favorite department.We’ll be glad to send yourecommended language.Contact: Anne T. Melvin orGrant H.WhitneyOffice of Gift Planning124 Mt. Auburn St.Cambridge, MA 02138617-496-3205 (phone)617-495-0521 (fax)ogp@harvard.eduHarvard University16GSAS