Indigenous Democracy - Centre for Human Rights, University of ...

Indigenous Democracy - Centre for Human Rights, University of ...

Indigenous Democracy - Centre for Human Rights, University of ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

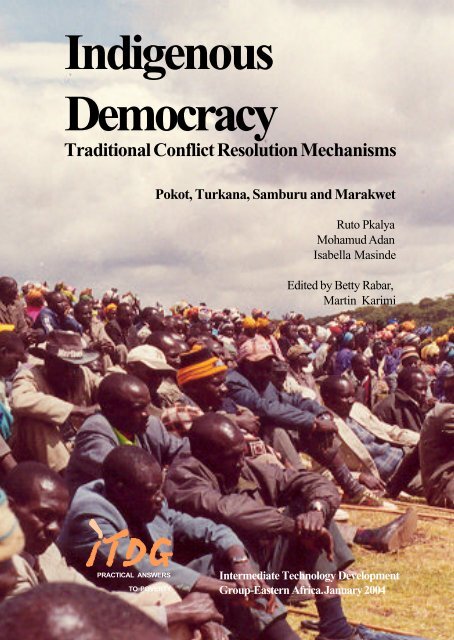

<strong>Indigenous</strong><strong>Democracy</strong>Traditional Conflict Resolution MechanismsPokot, Turkana, Samburu and MarakwetRuto PkalyaMohamud AdanIsabella MasindeEdited by Betty Rabar,Martin KarimiPRACTICAL ANSWERSTO POVERTYIntermediate Technology DevelopmentGroup-Eastern Africa. January 2004

<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Democracy</strong>Traditional Conflict Resolution MechanismsPokot, Turkana, Samburu and MarakwetA publication <strong>of</strong> ITDG-EA,January 2004Isabella MasindeMohamud AdanRuto PkalyaEdited by Betty Rabar,Martin Karimi

Copyright 2004Intermediate Technology Development Group - EasternAfrica.Use <strong>of</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation contained in this publication, eitherwholly or in part is permitted provided the source isackowledged.January 2004DTPMartin KarimiISBN 9966 - 931 - 17 - 1This publication was funded by USAID, and UNDP/GEF (EACBBP).

Strengths and Weaknesses <strong>of</strong> Turkana Mechanisms...................58Chapter 5, The MarakwetMarakwet’s Defination <strong>of</strong> Conflict................................................61Customary Institutions <strong>of</strong> Governance and Conflict Resolution......62Prevention and Management <strong>of</strong> Marakwet Internal Conflicts..........63Inter-ethnic Conflicts................................................................68Prevention and Management <strong>of</strong> Marakwet’s External Conflicts......70Strengths and Weaknesses <strong>of</strong> Maraket Customary Mechanisms <strong>of</strong>Conflict Management................................................................73Chapter 6, The SamburuSocio-Political Institutions.........................................................75Internal Conflicts.....................................................................77Prevention and Management <strong>of</strong> Internal Conflicts........................78External Conflict......................................................................81Causes and Manifestations <strong>of</strong> External Conflicts.........................81Prevention and Management <strong>of</strong> Inter-ethnic Conflicts....................84Strengths and Weaknesses <strong>of</strong> Samburu Conflict ResolutionMechanisms............................................................................86Chapter 7Improving Traditional Mechanisms <strong>of</strong> Conflict Resolution.............90Chapter 8Conclusion and Recommendations...........................................93Selected Bibliography...........................................................100AnnexResearch Questionnnaire.........................................................102

Intermediate Technology Development GroupIntermediate Technology Development Group (ITDG) wasestablished in 1966 based on the then radical ideas <strong>of</strong> FritzSchumacher, an economist and the author <strong>of</strong> “Small is Beautiful”.ITDG has since grown into an international development agencywith its head <strong>of</strong>fice in UK and regional <strong>of</strong>fices in East Africa, SouthAsia, South America and Southern Africa. It also has country <strong>of</strong>ficesin Bangladesh, Nepal and Sudan.ITDG’s work is driven by its vision <strong>of</strong> “a world free <strong>of</strong> poverty andinjustice in which technology is used <strong>for</strong> the benefit <strong>of</strong> all”.ITDG’s mission is “to help eradicate poverty in developingcountries through the development and use <strong>of</strong> technology bydemonstrating results, sharing knowledge and influencingothers”. ITDG’s development is guided by the following coreprinciples; putting people first; working in partnership, respect <strong>for</strong>diversity and a concern <strong>for</strong> future generations.Intermediate Technology Development Group-Eastern Africa (ITDG-EA) is a regional <strong>of</strong>fice <strong>of</strong> ITDG. The organization works towardsfulfilling its mission in Eastern Africa by reducing vulnerability,increasing services to the people, making markets work <strong>for</strong> poorproducers and introducing new technologies.Conflict resolution and cross-border harmonization is an integralcomponent <strong>of</strong> the group’s aim <strong>of</strong> reducing vulnerability among poorpeople especially the pastoral communities in the Greater Horn <strong>of</strong>Africa. Through the Conflict Management Project, the agency isimplementing peace programmes in Northern Kenya (Turkana,Marsabit, and Samburu) and works through partners in West Pokot,Marakwet, Moyale, Mandera and Wajir Districts. In conjunction withpartners, ITDG-EA is implementing cross-border activities inSouthern Ethiopia (Omo region), Southern Sudan, Eastern Uganda(Karamoja cluster) and Western Somalia.i

AcronymsASAL Arid and Semi Arid LandAU IBAR African Union InterAfrican Bureau <strong>of</strong> AnimalResourcesCAPE Community Based Animal Health andParticipatory EpidemiologyCBO Community Based OrganizationCORDAID Catholic Organization <strong>for</strong> Relief andDevelopment AidCSO Civil Society OrganizationDDC District Development CommitteeDRC Democratic Republic <strong>of</strong> CongoDSC District Security CommitteeDSG District Steering GroupEACBBP East Africa Cross Border Biodiversity ProjectITDG Intermediate Technology Development GroupNGO Non Governmental OrganizationPEDP Pokot Educational and DevelopmentProgrammePPG Pastoralists Parliamentary GroupSALW Small Arms and Light WeaponsSRIC Security Research and In<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>Centre</strong>USAID United States Agency <strong>for</strong> InternationalDevelopmentUSIP United States Institute <strong>of</strong> Peaceiii

Bloomingdale630-582-4100Nov 03, 2014-Nov 10, 2014Class BulletinSep 10, 2014-Sep 10, 2031 WE 03:50 PM 30 min LEISURE POOL $50.00 USD 5Sep 13, 2014-Sep 13, 2031 SA 11:20 AM 30 min LEISURE POOL $50.00 USD 5Nov 02, 2014-Nov 02, 2020 SU 09:35 AM 30 min LEISURE POOL $50.00 USD 4Wave 401 PrivateWave 401 (ages 5-6)Wave 401 is designed <strong>for</strong> the child who completed a 301 level class or is assessed as being able to swim front crawl and backstroke.Children will work on front crawl with roll breathing, backstroke, rotary breathing, whip kicks and butterfly arms.(Private ratio: 1:1)Children can gain and improve swimming skills even more rapidly in private lessons. Thirty-minute private and semi-private areavailable <strong>for</strong> all ages and skill levels. You are required to find your own semi-private partner. To schedule lessons, call or stop by theAquatics <strong>of</strong>fice.PrivateDates Days Time Duration Location Price Class SizeAug 16, 2014-Nov 03, 2014 SA 09:00 AM 30 min LEISURE POOL $200.00 USD 1Wave 401 Semi-PrivateWave 401 (ages 5-6)Wave 401 is designed <strong>for</strong> the child who completed a 301 level class or is assessed as being able to swim front crawl and backstroke.Children will work on front crawl with roll breathing, backstroke, rotary breathing, whip kicks and butterfly arms.(Semi-private ratio: 1:2 or 1:3)Children can gain and improve swimming skills even more rapidly in private lessons. Thirty-minute private and semi-private areavailable <strong>for</strong> all ages and skill levels. You are required to find your own semi-private partner. To schedule lessons, call or stop by theAquatics <strong>of</strong>fice.Dates Days Time Duration Location Price Class SizeMar 05, 2014-Mar 05, 2030 WE 06:10 PM 30 min LEISURE POOL $100.00 USD 3Wave 501 GroupWave 501 (ages 5-6; ratio 1:5)Wave 501 is designed <strong>for</strong> the child who completed a 401 level class or is assessed as being able to swim all four competitive strokes.Children will work on developing their technique and endurance in all four competitive strokes, with an emphasis places on therhythm and proper timing involved in each stroke.501Dates Days Time Duration Location Price Class SizeJul 13, 2014-Jul 13, 2040 SU 09:00 AM 30 min LEISURE POOL $50.00 USD 5Wave 601 GroupWave 601 (ages 5-6; ratio 1:6)Wave 601 is designed <strong>for</strong> the child who completed a 501 level class or is assessed as being able to swim all four competitive strokesand get ready <strong>for</strong> swim team. In addition to fine tuning their strokes, student will learn rhythmic breathings, flip turns and legalfinishes <strong>for</strong> each stroke.Dates Days Time Duration Location Price Class SizeJan 18, 2014-Jan 18, 2030 SA 10:45 AM 30 min LEISURE POOL $50.00 USD 6Sep 10, 2014-Sep 10, 2031 WE 05:00 PM 30 min LEISURE POOL $50.00 USD 6Wave 601 PrivateWave 601 (ages 5-6)Wave 601 is designed <strong>for</strong> the child who completed a 501 level class or is assessed as being able to swim all four competitive strokesand get ready <strong>for</strong> swim team. In addition to fine tuning their strokes, student will learn rhythmic breathings, flip turns and legalfinishes <strong>for</strong> each stroke.(Private ratio: 1:1)Children can gain and improve swimming skills even more rapidly in private lessons. Thirty-minute private and semi-private areavailable <strong>for</strong> all ages and skill levels. You are required to find your own semi-private partner. To schedule lessonetiveand not liable to critique, <strong>for</strong> it is laden with superstitiousbeliefs.iv

AbstractThis publication details the indigenous methods <strong>of</strong> conflictresolution among the Pokot, Tukana, Samburu, andMarakwet communities <strong>of</strong> North Rift Kenya. Traditionalconflict resolution structures are closely bound with sociopoliticaland economic realities <strong>of</strong> the lifestyles <strong>of</strong> theAfrican communities. These conflict resolution structuresare rooted in the culture and history <strong>of</strong> African people,and are in one way or another unique to each community.The overriding legitimacy <strong>of</strong> indigenous conflict resolutionstructures amongst these communities is striking.The publication outlines scarce and unequal access tonatural resources and power, ethnic mistrust(ethnocentrism), inadequate state structures, bordertensions and proliferation <strong>of</strong> illicit arms into the hands <strong>of</strong>tribal chiefs, warlords and fellow tribesmen as some <strong>of</strong>the causes <strong>of</strong> inter-ethnic conflicts in northern Kenya.A brief description <strong>of</strong> the three communities regarded asrepresentative <strong>of</strong> the entire pastoralists community in thegreater horn <strong>of</strong> Africa region has been given. In addition,a detailed description and analysis <strong>of</strong> their indigenousgovernance and conflict resolution institutions has beencarried out. The Kokwo amongst the Pokot andMarakwet, the tree <strong>of</strong> men amongst the Turkana andNabo among the Samburu communities are perhaps themost important governance institutions amongst thestudy communities.The study found out that cattle rustling, and to someextent, land clashes are the main manifestation <strong>of</strong>conflicts in northern Kenya. In response to the cattlerustling menace that has ravaged the vast and ruggedregion, the communities under study have evolved overtime and institutionalised an elaborate system andmechanisms <strong>of</strong> resolving conflicts whether intrav

community or inter-community. The elders in the threecommunities <strong>for</strong>m a dominant component <strong>of</strong> thecustomary mechanisms <strong>of</strong> conflict management. Theelders command authority that makes them effective inmaintaining peaceful relationships and community way<strong>of</strong> life. The authority held by the elders is derived fromtheir position in society. They control resources, maritalrelations, and networks that go beyond the clanboundaries, ethnic identity and generations. The eldersare believed to hold and control supernatural powersrein<strong>for</strong>ced by belief in superstitions and witchcraft. Thisis perhaps the basis <strong>of</strong> the legitimacy <strong>of</strong> traditional conflictresolution mechanisms amongst the pastoralists.Among other findings, this study has given dueconsideration to the unique pastoralists’ cultures thatemphasise the resolution <strong>of</strong> conflicts amicably througha council <strong>of</strong> elders, dialogue, traditional rituals andcommon utilization <strong>of</strong> resources especially dry-seasongrazing land. Peace pacts between these communitieshave largely been hinged on availability <strong>of</strong> pasture andwater and entirely cushioned on a win-win situation. Thecurrent peaceful relationship and military alliancebetween Pokot and Samburu, Turkana and Mathenikoand Pokot and Matheniko are testimonies to the power<strong>of</strong> indigenous customary arrangements <strong>of</strong> peace buildingand border harmonization. Nevertheless, such peacepacts are flouted as soon as conditions that necessitatedthe pact cease to hold as they are governed byopportunistic tendencies. In total, the said communitieshave consistent and more elaborate methods <strong>of</strong>intervening in internal (intra-ethnic) conflicts than theinter-ethnic conflicts.The study reports that among the three communities,there is a marked absence or inadequacy <strong>of</strong> en<strong>for</strong>cementmechanisms/framework to effect what the elders andvi

other traditional courts have ruled. The customary courtsrely on goodwill <strong>of</strong> the society to adhere to its ruling.In terms <strong>of</strong> gender consideration, the whole process isgrossly flawed. There is a serious gender and ageimbalance as women and youth are largely excluded fromimportant community decision-making processes.Women and children are there to be seen and not hearddespite <strong>of</strong> the fact that they play a critical role inprecipitating conflicts.Limited government understanding <strong>of</strong> pastoralists’livelihoods and the ensuing marginalization <strong>of</strong>pastoralists’ issues, livelihoods and institutions havecorroded the efficacy and relevance <strong>of</strong> customaryinstitutions <strong>of</strong> conflict management. Such traditionalstructures are referred to as archaic, barbaric and thatthey lack a place in the modern global village. As a result,governments fail to appreciate, collaborate andcomplement the traditional methods <strong>of</strong> resolving conflicts.These pseudo critics have failed to acknowledge thatthe African traditional mechanisms <strong>of</strong> conflict resolutionare fundamentally different from the Western ways <strong>of</strong>conflict resolution.The study proposes that there should be increasedcollaboration and networking between the governmentand customary institutions <strong>of</strong> governance. In particular,the government should recognize and aid customarycourts en<strong>for</strong>ce their rulings. The elders should be trainedon modern methods <strong>of</strong> arbitration and at minimum,traditional mechanisms <strong>of</strong> conflict management shouldbe more sensitive to the universally accepted principles<strong>of</strong> human rights.Gender and age mainstreaming in conflict resolutionshould be prioritised in all traditional courts and invii

decision-making processes. Women and children voicesshould be heard and be seen to fundamentally alter thepace and direction <strong>of</strong> community governance system.The regional problem <strong>of</strong> illicit arms that has scaled upthe severity and frequency <strong>of</strong> cattle raids should beaddressed by the governments in the region. These armshave also sneaked in the veiled aspect <strong>of</strong>commercialisation <strong>of</strong> cattle raids in the region.Pastoralists are no longer raiding to replenish their stocksespecially after periods <strong>of</strong> severe drought and animaldiseases, but are increasingly raiding to enrichthemselves by engaging in trade <strong>of</strong> stolen livestock. Thisaspect has overwhelmed traditional conflict resolutionmechanisms and should be addressed.viii

Chapter 1Introduction1.1 Problem StatementFor a long time, Africa has been saddled and boggeddown by intermittent conflicts both within and betweenits states. From Algeria to Sierra Leone, Liberia to Sudan,the Horn, East and Central Africa and the Great LakesRegion armed conflicts are increasing and are almostexclusively within rather than between states. Evencountries that were once regarded as island <strong>of</strong> peaceand tranquillity such as Ivory Coast have fallen victims<strong>of</strong> the escalating armed conflicts in Africa.In these conflict scenarios, poorer and more marginalizedpeople are the principal victims rather than members <strong>of</strong>the armed <strong>for</strong>ces. In addition to death and wantondestruction that it brings in its wake, the conflicts alsocontribute to displacement and disruption <strong>of</strong> livelihoods<strong>of</strong> the poor people.Conflicts among the Pokot, Turkana, Somali, Boran,Rendille, Marakwet and Samburu are the trademark <strong>of</strong>the vast, marginalized and rugged terrain <strong>of</strong> northernKenya. Hardly a week elapses be<strong>for</strong>e the Kenyan mediareports inter-ethnic cattle raiding and intra-ethnic clan(Somali) skirmishes among these communities, resultingin enormous loss <strong>of</strong> lives, property and displacements.1

Nomadic pastoralism is the main economic activity andthe main source <strong>of</strong> livelihood in the arid and semi aridnorthern Kenya. Apart from environmental vagaries,conflicts are many and centre mainly, on the exploitation<strong>of</strong> the limited resources. Conflict over natural resourcessuch as land, water, and <strong>for</strong>ests is ubiquitous. Peopleeverywhere have competed <strong>for</strong> the natural resources theyneed or want to ensure or enhance their livelihoods.However, the dimensions, level, and intensity <strong>of</strong> conflictvary greatly. Conflicts over natural resources can takeplace at a variety <strong>of</strong> levels, from within the household tolocal, regional, societal, and global scales. Furthermore,conflict may cut across these levels through multiplepoints <strong>of</strong> contact. The intensity <strong>of</strong> conflict may also varyenormously — from confusion and frustration amongmembers <strong>of</strong> a community over poorly communicateddevelopment policies to violent clashes between groupsover resource ownership rights and responsibilities. Withreduced government power in many regions, theresource users, who include pastoralists, marginalfarmers and agro-pastoralists, increasingly influencenatural resource management decisions.However, the causes <strong>of</strong> conflict are diverse, and include:limited access to water and pasture resources, loss <strong>of</strong>traditional grazing land, cattle raiding, lack <strong>of</strong> alternativesources <strong>of</strong> livelihood from pastoralism, diminishing role<strong>of</strong> traditional institutions in conflict management, politicalincitement, non-responsive governments policy and intertribalanimosity. The complexity <strong>of</strong> the conflicts isheightened by the presence <strong>of</strong> international and regionalboundaries that have affected nomadic pastoralismthrough creation <strong>of</strong> administrative units, which splitcommunities that once lived together. This is true <strong>for</strong>example, between the Pokot and the Turkana whooccupy parts <strong>of</strong> Kenya and Uganda. These boundarieshave interfered with seasonal movements (nomadism)2

that were occasioned by resource dynamics. Proliferation<strong>of</strong> small arms and light weapons (SALW) from war torncountries in the Horn <strong>of</strong> Africa and the Great LakesRegion (Rwanda, Burundi and DRC) have amplified theproblem. The failed Somalia state coupled with theongoing civil war in Southern Sudan has resulted inproliferation <strong>of</strong> thousands <strong>of</strong> dangerous arms into thehands <strong>of</strong> tribal chiefs, warlords and ordinary tribesmen.Due to remoteness, rugged terrain, underdevelopedinfrastructure and pastoralists’ migratory nature, the<strong>for</strong>mal security system is inaccessible and/orinappropriate to manage the nature and the magnitude<strong>of</strong> the current conflicts. This is why despite the presence<strong>of</strong> <strong>for</strong>mal security personnel in Kenya, Uganda andSudan, conflicts executed in the <strong>for</strong>m <strong>of</strong> cattle rustlinghas continued to claim human lives, loss <strong>of</strong> property anddestruction <strong>of</strong> biodiversity.Despite the sustained local, state and regional ef<strong>for</strong>ts toresolve inter-community conflicts in northern Kenya andacross the borders, there has been no success inreducing the tally <strong>of</strong> these conflicts in successive years.The inability <strong>of</strong> these ef<strong>for</strong>ts to contain and resolve theconflicts infers a failure to identify a conflict-resolutionframework that would satisfy the traditional (thoughchanging) socio-political and cultural dynamics <strong>of</strong> theparties in conflict. Such a framework will have to berooted in customary principles <strong>of</strong> “war and peace” asembedded in traditions and social structure <strong>of</strong> acommunity that takes into consideration not only thedistributive issues that are amenable to negotiation andacceptable solutions, but also the subjective andemotionally loaded issues such as group status, identityand survival that are <strong>of</strong>ten non-negotiable and principalsources <strong>of</strong> unmanageable conflicts.3

<strong>Indigenous</strong> conflict management and resolutionmechanisms use local actors and traditional communitybasedjudicial and legal decision-making mechanismsto manage and resolve conflicts within or betweencommunities. Local mediation typically incorporatesconsensus building based on open discussions toexchange in<strong>for</strong>mation and clarify issues. Conflictingparties are more likely to accept guidance from thesemediators than from other sources because an elder’sdecision does not entail any loss <strong>of</strong> face and is backedby social pressure. The end result is, ideally, a sense <strong>of</strong>unity, shared involvement and responsibility, and dialogueamong groups otherwise in conflict.Community members involved in the conflict participatein the dispute resolution process. These communitymembers can include traditional authorities, <strong>for</strong> instanceelders, chiefs, women’s organizations, and localinstitutions.The elders in traditional African societies <strong>for</strong>m a dominantcomponent <strong>of</strong> the customary mechanisms <strong>of</strong> conflictmanagement. The elders have three sources <strong>of</strong> authoritythat make them effective in maintaining peacefulrelationships and community way <strong>of</strong> life. They controlaccess to resources and marital rights; they have accessto networks that go beyond the clan boundaries, ethnicidentity and generations; and possess supernaturalpowers rein<strong>for</strong>ced by superstitions and witchcraft.The elders function as a court with broad and flexiblepowers to interpret evidence, impose judgements, andmanage the process <strong>of</strong> reconciliation. The mediator leadsand channels discussion <strong>of</strong> the problem. Parties typicallydo not address each other, eliminating directconfrontation. Interruptions are not allowed while partiesstate their case. Statements are followed by open4

deliberation which may integrate listening to and crossexaminingwitnesses, the free expression <strong>of</strong> grievances,caucusing with both groups, reliance on circumstantialevidence, visiting dispute scenes, seeking opinions andviews <strong>of</strong> neighbours, reviewing past cases, holdingprivate consultations, and considering solutions.The elders or other traditional mediators use theirjudgment and position <strong>of</strong> moral ascendancy to find anacceptable solution. Decisions may be based onconsensus within the elders’ or chiefs’ council and maybe rendered on the spot. Resolution may involve<strong>for</strong>giveness and mutual <strong>for</strong>mal release <strong>of</strong> the problem,and, if necessary, the arrangement <strong>of</strong> restitution. Localmediation typically incorporates consensus buildingbased on open discussions to exchange in<strong>for</strong>mation andclarify issues. Conflicting parties are more likely to acceptguidance from these mediators than from other sourcesbecause an elder’s decision does not entail any loss <strong>of</strong>face and is backed by social pressure. The end result is,ideally, a sense <strong>of</strong> unity, shared involvement andresponsibility, and dialogue among groups otherwise inconflict.Traditional <strong>for</strong>ms <strong>of</strong> mediation and legal sanctioning <strong>of</strong>tenappear in the aftermath <strong>of</strong> widespread conflict where noother mechanisms <strong>for</strong> social regulation exist. This isparticularly true in the case <strong>of</strong> failed states such asSomalia and partly Sudan, where indigenousmechanisms, some ad hoc, others traditional and longestablished,provide order where the outsider’s eye seesonly chaos. In many areas <strong>of</strong> Somalia including parts <strong>of</strong>Mogadishu, Sharia courts are en<strong>for</strong>cing law and order, awelcome novelty <strong>for</strong> residents who have been deprived<strong>of</strong> a functioning judicial system <strong>for</strong> years.5

Traditional mediation is effective in dealing withinterpersonal or inter-community conflicts. This approachhas been used at the grassroots level to settle disputesover land, water, grazing-land rights, fishing rights, maritalproblems, inheritance, ownership rights, murder, brideprice, cattle raiding, theft, rape, banditry, and inter-ethnicand religious conflicts.It would be correct to argue that the elders in thepastoralist communities <strong>of</strong> northern Kenya are not entirelyable to operate and resolve conflicts within thesestructural limits <strong>of</strong> customary conflict management. Theprocess may be time-consuming and encourage broaddiscussion <strong>of</strong> aspects that may seem unrelated to thecentral problem, as the mediator tries to situate theconflict in the disputants’ frame <strong>of</strong> reference and decideon an appropriate style and <strong>for</strong>mat <strong>of</strong> intervention.Nevertheless, they are critically important in maintainingpeaceful relationships in these communities.1.2 Purpose <strong>of</strong> the studyThe purpose <strong>of</strong> this study was to conduct participatoryresearch and in-depth analysis <strong>of</strong> traditional conflictresolution mechanisms amongst the Pokot, Turkana,Samburu, Marakwet and Borana communities in Kenya.This was conceptualised on the basis <strong>of</strong> under-utilisedefficacy <strong>of</strong> traditional institutions in conflict management.Conceptualisation <strong>of</strong> the pastoralists’ conflicts asresource-based and with cultural overtones puts theemphasis on the access and distribution there<strong>for</strong>e allowsessential insights into alternative, culturally acceptabledisputes resolution mechanisms. The pastoralist’ssituation in Kenya and across the borders jeopardisesstates’ legal and moral obligation to provide security toits citizens. In the case <strong>of</strong> northern Kenya, one noticesthe classical retreat <strong>of</strong> the state, first, on its existenceand, second, its ineptitude. Where the state fails or is6

unable to provide such security to its people, logicdemands that the people seek alternative means to meetthese challenges. Traditional conflict resolutionmechanisms become the alternative.The ability <strong>of</strong> local mechanisms to resolve conflictswithout resorting to state-run judicial systems, police, orother external structures is the ingenuity <strong>of</strong> thesestructures that have largely been ignored andmarginalized. Local negotiations can lead to ad hocpractical agreements, which keep broader intercommunalrelations positive, creating environmentswhere nomads can graze together, urban people canlive together, and merchants can trade even if militarymen remain in conflict.Additional results <strong>of</strong> local conflict management occurwhen actors who do not have political, social or economicstake in continuing violence come together and build a‘constituency <strong>for</strong> peace.’ In some cases, this canundermine the perpetrators <strong>of</strong> violence, leading to thedevelopment <strong>of</strong> momentum toward peace.The introduction <strong>of</strong> police, courts and prison systemshave been erroneously interpreted to infer that thecustomary law has been rendered obsolete and its placetaken by the western styled court system. Nevertheless,pastoralists have continued to rely on customary law andmechanisms in resolving their conflicts both within andwithout the communities.Documented reference will bridge the in<strong>for</strong>mation gapthat has existed in African societies and this will go along way in passing customary law and system fromgeneration to generation.The specific objectives <strong>of</strong> this study were:7

♦♦♦♦To have an in-depth understanding and analysis<strong>of</strong> traditional conflict resolution mechanisms.To collect and collate the most common types <strong>of</strong>intra-ethnic and inter-ethnic disputes and thetraditional mechanisms <strong>of</strong> their managementamong the Pokot, Turkana, Samburu andMarakwet communities.To critically assess the role and efficacy <strong>of</strong>customary institutions <strong>of</strong> conflict management inpresent-day pastoralist conflict and the modernstate legal framework.To examine the ways in which customaryinstitutions <strong>of</strong> conflict management can bestrengthened and integrated within the <strong>for</strong>malmodern state judicial framework.Local mechanisms aim to resolve conflicts withoutresorting to state-run judicial systems, police, or otherexternal structures. Grassroots mediation depends onan existing tradition <strong>of</strong> local conflict managementmechanisms, even if these are currently marginalized ordormant.1.3 Study MethodologyPokot, Turkana, Samburu and Marakwet communitiesw e r estrategicallyselected asstudy samplessince theydemonstrate arich indigenousknowledge andmechanisms inc o n f l i c tresolution. Thepastoralists are8

in constant acrimony. They have also tried to resolvethe conflicts using traditional mechanisms. It is adocumented fact that pastoralist communities haveelaborate mechanisms <strong>of</strong> resolving their intra and intercommunity/clan conflicts. The word ‘pastoralists’ is <strong>of</strong>tenused to indicate a broad ethnic origin and livelihood.However, it should be noted that, pastoralism is a way <strong>of</strong>life and livelihood largely cushioned on resource scarcityand dynamics.The methodology that was applied in this study involvedsurveys <strong>of</strong> the existing indigenous conflict resolutionmechanisms, interviews with pastoralists’ elders, warriorsand women and plenary discussions by peacecommittees among the study communities. Both fieldinterviews as well focused group discussions and indepthanalysis <strong>of</strong> relevant secondary data sources suchas published and unpublished books, magazines andjournals were put to use.The primary methodology <strong>of</strong> the study involved interviewsand discussions with pastoralists’ communities’ eldersin each <strong>of</strong> the four communities covered. The elders wereselected on the basis <strong>of</strong> leadership experience in thecommunity, command <strong>of</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> the community’sfolktale and way <strong>of</strong> life, and proven longstandingparticipation in <strong>for</strong>ums to settle or manage conflicts anddisputes in the community. The elders had to showknowledge <strong>of</strong> community values, practices andphilosophy <strong>of</strong> life.The researchers also used participant observation incollecting the in<strong>for</strong>mation. The researchers participatedin a number <strong>of</strong> <strong>for</strong>ums that customary mechanisms wereused to resolve inter-ethnic conflicts. These <strong>for</strong>umsincluded the Todonyang declaration between Turkana,Merille and Dong’iro communities, Pokot and Marakwet9

communities peace talks organized by Pokot Educationaland Development Programme (PEDP) at KameleyPrimary School ground, Wajir regional peace meetingthat brought together Wajir, Moyale and Marsabit districtsat Wajir and the Modogashe declaration meeting. Videodocumentation <strong>of</strong> various pastoralists’ traditional conflictresolution processes was also used in the study. Ageand gender balance was maintained throughout thestudy.10

Chapter 2The Study Communities2.1. The PokotThe bulk <strong>of</strong> the Pokot people are found in West Pokotdistrict, situated along Kenya’s western boundary withUganda and borders Trans Nzoia and Marakwet districtsto the south, Baringo and Turkana districts to the eastand north respectively. The district is arid and semi arid.Apart from West Pokot district, a substantial number <strong>of</strong>Pokot people are inBaringo, Trans Nzoiaand to a lesser extentSamburu district. InUganda, the Pokotpeople are found inNakapirpirit district inthe largerKaramojang region.Pokot history isdifficult to sketch.Linguistically, theyseem to be related tonumerous peopleswho live in the regionwith ties to both theNilo-Hamitic peopleswho came from North11

Africa and to Bantu peoples who came from centralAfrica. For purposes <strong>of</strong> the Kenyan census Pokot areplaced in the Kalenjin group, which consists <strong>of</strong> manydiverse groups <strong>of</strong> people who share Nilo-Hamitic ancestryand history. Some authorities also consider the Pokotcommunity as the fourteenth tribe <strong>of</strong> the largerKaramojang cluster. This assumption is derived from thefact that each Pokot man, like the rest <strong>of</strong> Karamojangcluster men, has a bull that is particularly significant tohim. The choice <strong>of</strong> a bull is made using appearance as acriterion and a name that reflects the look <strong>of</strong> the bull isassigned to it. The man will then adopt the name <strong>of</strong> thisbull as his own, and sing songs in praise <strong>of</strong> his bull in anattempt to attract women. This description could as wellsuggest that even the lowland Marakwet are the fifteenthKaramojang cluster.Amongst the Karamojang people, from birth until death,cattle constitute not only their livelihood but also the verycentre <strong>of</strong> their lives. Birth, the passage to adulthood,marriage, death and the passing <strong>of</strong> decision-makingpower from one generation set to the next are all markedby the praising, slaughter and sharing <strong>of</strong> cattle.The nomadic way <strong>of</strong> life that most <strong>of</strong> the Pokot live hasallowed them to come into contact with numerousdifferent peoples throughout history. This interaction hasallowed them to incorporate social customs that in somecircumstances included marriage with other communities.Many specific Pokot customs seemed to be borrowedfrom their Turkana and Karamojang neighbours.About one quarter <strong>of</strong> Pokot peoples are cultivators (cornpeople), while the remaining are pastoralists (cowpeople). Between both groups, however, the number <strong>of</strong>cows one owns measures wealth. Cows are used <strong>for</strong>barter exchange, and most significantly as a <strong>for</strong>m <strong>of</strong> bride12

wealth. A man is permitted to marry more than onewoman, as long as he has sufficient number <strong>of</strong> cows to<strong>of</strong>fer as bride price. This is the primary way <strong>for</strong> wealthand resources to change hands in Pokot society. Cowsare rarely slaughtered <strong>for</strong> meat. They are much morevaluable alive. Cows provide milk, butter, and cheese,which <strong>for</strong>m the core <strong>of</strong> Pokots’ dietary needs.Pokot community is governed through a series <strong>of</strong> agegrades.Group membership is determined by the age atwhich one undergoes initiation. For young men thisoccurs between ages fifteen and twenty, while <strong>for</strong> youngwomen it usually occurs around age twelve at the onset<strong>of</strong> menarche. After initiation, young people are allowedto marry and are permitted to begin participating in localeconomic activities. Young men and women <strong>for</strong>m closebonds with other members <strong>of</strong> their initiation groups, andthese bonds serve <strong>for</strong> future political ties. When a manor woman reaches old age, he or she is accorded acertain degree <strong>of</strong> status and respect. Responsibilities <strong>of</strong>elders include presiding over important communitydecisions, festivals, and religious ceremonies.Tororot is considered the supreme deity among thePokot. Prayers and <strong>of</strong>ferings are made to him duringcommunal gatherings, including feasts and dances. Suchceremonies are usually presided over by a communityelder. Diviners and medicine men also play a significantrole in maintaining spiritual balance within the community.Pokot believe in sorcery and use various <strong>for</strong>ms <strong>of</strong>protection to escape the ill will <strong>of</strong> sorcerers. Pokot alsorevere a series <strong>of</strong> other deities, including sun and moondeities and a spirit who is believed to be connected withdeath. Dances and feasts are held to thank the god <strong>for</strong>the generosity and abundance, which he bestows uponPokot communities.13

2.2 The TurkanaThe Turkana are one <strong>of</strong> the most courageous and fiercegroups <strong>of</strong> warriors in Africa. They are traditionallynomadic shepherds, the majority <strong>of</strong> whom live west <strong>of</strong>Lake Turkana in the present day Turkana district. Turkanadistrict is part <strong>of</strong> Kenya’s arid and semi arid lands. It issituated along Kenya’s northwestern border with Ugandaand Sudan, and Ethiopia to the north. It also bordersKenyan districts <strong>of</strong> West Pokot and Baringo to thesoutheast and Marsabit to the east. About 22,000Turkana <strong>of</strong> Ethiopia live west <strong>of</strong> the Omo River in theextreme southwestern regions <strong>of</strong> the country. OtherTurkana people can be found in eastern Uganda,Marsabit, Isiolo, Samburu and Trans Nzoia districts <strong>of</strong>Kenya.The myth <strong>of</strong> Nayere (a heroine) indicates that the Turkanaoriginated from the Jie people <strong>of</strong> Uganda, probably duringa severe drought and entered their cave-land (eturkan),through Tarach River, near Moru anayere (hill <strong>of</strong> Nayere).Turkana land is a semi desert plain consisting <strong>of</strong> sand,gravel, pebble beds and scattered volcanic ranges. Thevegetation varies from desert to shrubs with scatteredthorn bush. In the Northwest the vegetation consists <strong>of</strong>grass such as Cynodon dactylon. In the central area,the vegetation is very poor and the ground cover is lessthan 5%. Along the watercourses, the vegetation consists<strong>of</strong> higher acacia trees, palms, and in some places thickthorn bushes.The Turkana refer to themselves as Ngiturkan and totheir land as Eturkan. Although they emerged as a distinctethnic group during the nineteenth century, the Turkanahave only a vague notion <strong>of</strong> their history. Their mainconcerns are land and how to win it, and livestock and14

how to acquire it. They have pursued these aims withsingle-mindedness <strong>for</strong> nearly 300 years.Among the traditional Turkana community, socio-politicalinfluence and power belongs to those who have age,wealth, wisdom (emuron), and oratorical skill. Socialorganization is based on territorial rights (the rights <strong>of</strong>pasture and water), kinship, relationships betweenindividuals, and rights in livestock and labour.The Turkana men <strong>of</strong>ten have multiple wives. When awife marries into a household, the head <strong>of</strong> the familygives her a portion <strong>of</strong> his livestock. Her sons will laterinherit these herds. Because <strong>of</strong> the unusually high brideprice, it is almost impossible <strong>for</strong> a man to marry until hisfather has died and he has inherited livestock. TheTurkana household consists <strong>of</strong> a man, his wives and theirchildren, and <strong>of</strong>ten the man’s mother.Young men undergo initiation at the age <strong>of</strong> 16 to 20.This ceremony involves animal sacrifice. Initiation is aprerequisite <strong>for</strong> later taking a human life. The status <strong>of</strong> awarrior is determined once a man has killed his firstenemy-an event he will mark by notching a scar on his15

ight shoulder or chest. After that time, he begins carryinga weapon. His clan sponsor gives him a spear and otherweapons, a stool that serves as a headrest, and a pair<strong>of</strong> sandals. The Turkana dress consists <strong>of</strong> a shuka (sheet<strong>of</strong> cloth) wrapped around the waist. Scars are made onthe arms to indicate how many victims the warrior hasinjured. White ostrich feathers are also worn on the heads<strong>of</strong> the warriors who have killed at least one person.Camels, cattle, sheep, and goats provide <strong>for</strong> most <strong>of</strong> theneeds <strong>of</strong> the Turkana. Donkeys are mainly used <strong>for</strong>transport especially during migrations. Turkanas’ dietconsists <strong>of</strong> goat milk, goat meat, grains, and wild fruit.Along the shores <strong>of</strong> Lake Turkana, some engage infishing and farming. The isolated Turkana do very littletrading with other tribes. They sell livestock in order tobuy grains and other household goods.The Turkana ascribe to their traditional African religion.Though fearless in all aspects, they are highlysuperstitious. They believe in dreams and place greatfaith in diviners (emurons) who have the power to healthe sick, make rain, and tell <strong>for</strong>tunes (by casting sandalsor reading animal intestines). The Turkana believe in asingle, all-powerful god, Akuj, who rarely intervenes inhuman affairs. The Turkana are skeptical <strong>of</strong> any divinerwho pr<strong>of</strong>esses to have mystical powers but fails todemonstrate that power in everyday life.2.3 The MarakwetMarakwet district is virtually the present home <strong>of</strong> theMarakwet People. The district was created through anexecutive order on 4 th August 1994. Initially, it was part<strong>of</strong> Elgeyo-Marakwet district. Marakwet district bordersWest Pokot to the north, Trans Nzoia to the west, UasinGishu to the southwest, Keiyo to the south, and Baringoto the east. The lower parts <strong>of</strong> the district are arid unlike16

the highlands, which are suitable <strong>for</strong> mixed farming andsedentary life. A number <strong>of</strong> Marakwet people are foundin Trans Nzoia, Uasin Gishu and Keiyo districts.Like the Pokot, Marakwet history is difficult to trace. Theyare considered as a sub-tribe <strong>of</strong> the larger Kalenjincommunity that also comprises the Pokot, Tugen, Keiyo,Nandi, Kipsigis and Sabaot. Their pastoral livelihood andgovernance is similar to that <strong>of</strong> the larger Karamojangcluster, and thus they are considered to be the fifteenthKaramojang cluster member. Linguistically, they arecloser to the Pokot community and to a lesser extent tothe other Kalenjins.The Marakwet society is divided into thirteen patrilinealclans, each <strong>of</strong> which (with the exception <strong>of</strong> the Sogomclan) is divided into two or more exogamic sectionsdistinguished by totems. Homesteads are in totemicsettlements scattered widely throughout the district. Thecommunity lives in territorial groups, which are politicallydistinct but interconnected by the clan structure and theage-sets. Their religious leader is known as the orgoy.He is consulted regarding the outcome <strong>of</strong> war, be<strong>for</strong>ethe warriors set out.Traditionallythe Marakwetrarely fightwars as aterritorialg r o u p .Nevertheless,Pokot andTugen aretraditionalenemies <strong>of</strong> theMarakwet. An17

individual is armed with a shield, a sword, a club andeither a spear or a bow and arrows.The Marakwet people are pastoralists, hunters as wellas agriculturalists. They keep cattle, sheep and goatsand depend on their animals <strong>for</strong> milk and meat. Theytraditionally built their homes on the escarpment. Thereis no story <strong>of</strong> creation told but Asis, is thought to be asupreme, omnipotent, omniscient arbitrator <strong>of</strong> all thingsand guarantor <strong>of</strong> right.2.4 The SamburuThe Samburu are the semi-nomadic pastoralists whodwell in the present day Samburu district in the centralparts <strong>of</strong> northern Kenya. Five districts in the Rift Valleyand Eastern Provinces border the district. To thenorthwest is Turkana district while to the southwest isBaringo district. Marsabit district is on the northeast, Isioloto the east and Laikipia district to the south. The language<strong>of</strong> the Samburu people is called Samburu. It is a Maalanguage very close to the Maasai dialects. Linguistshave debated the distinction between the Samburu andMaasai languages <strong>for</strong> decades. The Chamus (Njemps)speak the Samburu language and are <strong>of</strong>ten counted asSamburu people. The Samburu tongue is also relatedto Turkana and Karamojong, and more distantly to Pokotand the Kalenjin languages. The Samburu communityis characterized by the gerontocracy with age systems.The district is semi arid and supports crop farmingespecially in the highlands whereas the lowlands arepredominantly endowed with livestock resources. Atpresent, most <strong>of</strong> the Samburu people keep cattle, sheep,and goats. Pastoralism is the most prominent activity inthe district, taking up more than 90% <strong>of</strong> the land.18

The division <strong>of</strong> labour between the sexes and the agesorganizes the daily livestock keeping activities <strong>of</strong> theSamburu. Uncircumcised boys and girls graze theanimals. The circumcised young men are admitted tothe age set and are supposed to maintain the localsecurity. After marriage, old men are in control <strong>of</strong> thefamily and animals. Girls are married <strong>of</strong>f immediatelyafter circumcision. This ranges from the age <strong>of</strong> 12 years.Women not only maintain households but also checkand milk the animals every morning and evening. TheSamburu mainly live on milk. Their staple food is thestock products like yoghurt, butter, boiled meat, androasted meat. Cattle blood is drawn to drink sometimesmixed with milk or meat. Clothes, footwear, ropes, andbed sheets are made <strong>of</strong> animal’s skins. The communityplaster’s their house walls with cowpat.To the Samburu, the livestock are important not only asa means <strong>of</strong> subsistence but also as a means <strong>of</strong> socialcommunications. For example, if a person gives acastrated sheep to another person, they call each other‘paker’ which means “a castrated sheep” without referringto their proper names. In the Samburu community,livestock can be a medium <strong>of</strong> the social ties. Withoutpaying dowry in <strong>for</strong>m <strong>of</strong> livestock as bride wealth to thefiancé’s family, a man cannot marry in the Samburusociety. Likewise, to undergo initiation, it is mandatory<strong>for</strong> a Samburu to per<strong>for</strong>m rites <strong>of</strong> passage. In most cases,the rites involve livestock and or livestock’s products.For example, when sons and daughters are gettingcircumcised, a village elder has to smear butter on thehead <strong>of</strong> the boy/girl’s father.Initiation is done in age grades <strong>of</strong> about five years, withthe new “class” <strong>of</strong> boys becoming warriors, or morans(il-murran). The moran status involves two stages, juniorand senior. After serving five years as junior morans, the19

group goes through anaming ceremony,becoming senior morans<strong>for</strong> six years. After thisperiod, the seniormorans are free to marryand join the council <strong>of</strong>the junior elders.Samburu people arevery independent andegalitarian. Communitydecisions are made bymen (senior or bothsenior and junior elders),<strong>of</strong>ten under a treedesignated as a ‘council’meeting site. Women may sit in an outer circle andusually will not speak directly in the open council, butmay convey a comment or concern through a malerelative. However, women may have their own ‘council’discussions and then carry the results <strong>of</strong> suchdiscussions to men <strong>for</strong> consideration in the men’s council.The Samburu traditional religion is based onacknowledgment <strong>of</strong> the Creator God, whom they callNkai, as do other Maa-speaking peoples. They think <strong>of</strong>him as living in the mountains around their land, such asMount Marsabit. They also believe in charms and havetraditional ritual <strong>for</strong> fertility, protection, healing and otherneeds. But it is common to have prayer directly to Nkaiin their public gatherings. Samburu and MaasaiChristians use traditional Maasai prayer patterns in prayerand worship. They also use the term Nkai <strong>for</strong> variousspirits related to trees, rocks and springs, and <strong>for</strong> thespirit <strong>of</strong> a person. They believe in an evil spirit calledmilika.20

The greatest hope <strong>of</strong> an old man approaching death isthe honour <strong>of</strong> being buried with his face toward a majesticmountain, the seat <strong>of</strong> Nkai. The Samburu are devout intheir belief in God. But they believe he is distant fromtheir everyday activities. Diviners (laibon/ laibonok)predict the future and cast spells to affect the future.Civilization has brought so many changes in the lifestyleto the Samburu community. People now eat not only thelivestock products but also agricultural products, whichare bought with cash. The skirt made <strong>of</strong> goatskin hasbeen replaced by the ready-made dresses. Plastic beadshave also replaced the necklace made <strong>of</strong> the doom palm.21

Chapter 3The PokotThe Pokot community does not have a single word torefer to conflict. A number <strong>of</strong> phrases are used to describeand understand the concept. Poriot refers to the actualfight/combat whereas siala, kwindan, porsyo denotesquarrels and general disagreements. Nevertheless, thecommunity defines conflict as disagreement between aman and his wife or wives, disputes between parentsand children or children amongst themselves especiallyconcerning inheritance issues. Competition over pasture,grazing land and water resources, <strong>of</strong>ten leading to cattlerustling or raids, is the Pokot definition <strong>of</strong> inter-ethnicconflicts.Among the agro-pastoralists Pokot found in high potentialareas, access to land or outright land ownership isanother emerging description <strong>of</strong> conflicts. Land disputesare prevalent both at the community and inter-communitylevels.The Pokot community has an elaborate and systematicmechanism <strong>of</strong> classifying and resolving their internalconflicts vis-à-vis external conflicts. For instance, it is aserious crime <strong>for</strong> a fellow Pokot to steal a goat or a cowfrom a fellow Pokot. Stealing cattle (cattle raids) fromother communities is culturally accepted and even notregarded as a crime. It is the moral obligation <strong>for</strong> Pokot22

warriors to raid other communities solely to restock theirlivestock especially after a severe drought or generally<strong>for</strong> dowry purposes.3.1. Institutions <strong>of</strong> Conflict ManagementAmong the Pokot people, the family, the extended family,the clan and the council <strong>of</strong> elders (Kokwo) are the maininstitutions <strong>of</strong> conflict management and socio-politicalorganization <strong>of</strong> the community.a) The FamilyAn ideal Pokot family is composed <strong>of</strong> the husband (head<strong>of</strong> the family institution), his wives and children. Thehusband’s authority in the family is unquestionable. Heis the overall administrator <strong>of</strong> family matters and propertyincluding bride price, inheritance and where applicable,land issues.b) The Extended Family and NeighbourhoodThe extended family is made up <strong>of</strong> the nucleus family,in-laws and other relatives. All matters that transcendnucleus family are discussed at the extended family <strong>for</strong>a.The extended family serves as an appellate court t<strong>of</strong>amily matters. In some instances neighbours (porror)are called to arbitrate family disputes or disputes betweenneighbours.c) The Council <strong>of</strong> Elders (Kokwo)The Kokwo is the highest institution <strong>of</strong> conflictmanagement and socio-political stratum among thePokot community. Kokwo is made up <strong>of</strong> respected, wiseold men who are knowledgeable in community affairsand history. The elders are also good orators andeloquent public speakers who are able to use proverbsand wisdom phrases to convince the meeting or theconflicting parties to a truce. Every village is representedin the council <strong>of</strong> elders. Senior elderly women contribute23

to proceedings in a Kokwo while seated. Womenparticipate in such meetings as documentalists so as toprovide reference in future meetings. They can advisethe council on what to do and what not to do citing prioroccurrence or cultural beliefs. Be<strong>for</strong>e a verdict is made,women are asked to voice their views and opinions. TheKokwo observes the rule <strong>of</strong> natural justice. Both theaccused and the accuser are allowed to narrate theirstory be<strong>for</strong>e the panel. Traditional lawyers (eloquentmembers representing the plaintiff and defence) canspeak on behalf <strong>of</strong> the conflicting parties. The Kokwodeals with major disputes and issues and is mandatedto negotiate with other communities especially <strong>for</strong> peace,cease-fire, grazing land/pastures and water resources.The Kokwo is the highest traditional court and its verdictis final.3.2 Types, Prevention and Management <strong>of</strong> InternalConflictsImposing heavy fines and severe punishment has provedto be an effective method <strong>of</strong> preventing conflicts withinthe Pokot community. For instance, the practice <strong>of</strong>punishing the whole family or clan if one member commitsmurder, is in itself a prohibitive measure. In case <strong>of</strong>adultery, the fine is higher than the normal bride pricerendering the act economically and socially unviable. Inaddition, the purification process is tedious andfrustrating. The culprit is ridiculed in public and may beexcommunicated from the community.Although there is a marked absence <strong>of</strong> an elaboratemechanism or practice discouraging the Pokot fromengaging in acts <strong>of</strong> external conflicts, prohibitive finesrein<strong>for</strong>ced by superstitious beliefs, norms and tabooshave played a key role in controlling an upsurge <strong>of</strong> internalconflicts.24

a) Domestic ConflictsLike any other community, domestic quarrels do existamong the Pokot people. At the family level, disputes dooccur between the family members. A man and his wifeor wives might quarrel over issues such as lateness, poormilking skills, selfishness, and disobedience or generallaziness. If a man fails to provide food <strong>for</strong> his wife orwives, disputes arise. In polygamous homes (mostfamilies are polygamous), a husband might be accused<strong>of</strong> spending too much time in a certain house (wife). Thewives might also pick quarrels among themselves andso can their children.Inheritance is another prominent cause <strong>of</strong> domesticconflict among the Pokot. It is a customary principle thatmale children are entitled to their father’s propertyespecially when they are about to break-<strong>of</strong>f from thefamily to start their own homes. In such cases, somechildren might claim that the property was unevenlydistributed. In polygamous families, a woman might inciteher male children to demand certain things from theirfather to match her co-wife’s children. In isolated cases,a man might refuse to hand over part or all <strong>of</strong> his propertyto his children advising them to seek their own by raidingneighbouring communities. Inheritance disputes alsoarise after the death <strong>of</strong> the head <strong>of</strong> the family. How toshare and or manage the deceased property normallygenerates disputes since there are no written wills.Sharing <strong>of</strong> dowry earned from marrying <strong>of</strong>f a daughter isanother source <strong>of</strong> domestic conflict in Pokot community.However, there is an elaborate rule or procedure <strong>of</strong>determining who gets what. Nevertheless, quarrelsemerge during the process <strong>of</strong> sharing the dowry.Domestic conflicts are resolved at the family level. Thehead <strong>of</strong> the family arbitrates such cases and where he is25

an interested party or the accused, extended family canbe called to arbitrate the dispute. Neighbours can alsoarbitrate domestic quarrels if called upon to do so. Issuesthat cannot be conclusively or adequately resolved atthe family level are referred to the council <strong>of</strong> elders(Kokwo). There is no prescribed <strong>for</strong>m <strong>of</strong> punishment <strong>for</strong>any given kind <strong>of</strong> crime committed at the domestic level.It varies from household to household and solelydetermined by family members.b) TheftsTheft cases are prevalent and lead to conflicts within thePokot community. This is a crime punishable by a range<strong>of</strong> fines including death. Interestingly, the Pokotcommunity regards stealing from a fellow Pokot as aserious crime whereas stealing from other communitiesis not a crime but a just cultural practice <strong>of</strong> restocking.Livestock (cattle, goats, sheep, and camels) are the moststolen property among the Pokot people. Grains, poultry,clothes, spears, arrows and shields are rarely stolen.Theft cases are normally arbitrated at the KokwoSupreme Court. When an individual or family losessomething (a goat, sheep, cow, bull, steer, grain, poultry,camel, beer, gourd or money), the first thing that is doneis to make the loss publicly known. At the same timeinvestigations are undertaken with the help <strong>of</strong> wise menwho cast skin sandals to tell which direction the stolenitem is, and the sex, age, and colour <strong>of</strong> the suspectedthief. Circumstantial evidence is sought includingfootprints <strong>of</strong> the thief. If somebody shows up and admitsguilt, he or she is fined accordingly. As noted earlier, thereare no hard and fast rules guiding the fine. The fine isdecided upon at the whims <strong>of</strong> the elders. If nobody ownsup, a Kokwo is convened. However, the punishmentbecomes severe if the Kokwo proves you guilty.26

If no suspect is arrested, or in some instances wherethe suspect refuses to admit guilt, the elders announcethat a ‘satan’ (onyot) might have committed the crimeand the community is given a grace period <strong>of</strong> two weeksbe<strong>for</strong>e the ‘satan’ is condemned to death in a traditionalritual. During the grace period, parents are expected togrill their children and relatives in the hope <strong>of</strong> finding theculprit in order to avert the catastrophe that might bemeted on the family if one <strong>of</strong> them is responsible <strong>for</strong> thetheft. If the two weeks elapse and still nobody admitsguilt, the Kokwo reconvenes and a date <strong>of</strong> per<strong>for</strong>ming(muma) is scheduled.i) MumaMuma is an act <strong>of</strong> witchcraft. It is however culturallyacceptable due to the fact that it is done in daylight. Itonly targets the ‘satan’ and the community is in<strong>for</strong>med inadvance. Currently, a permit to per<strong>for</strong>m the ritual is soughtfrom the government making it legitimate. It is used <strong>for</strong>the good <strong>of</strong> society and not to harm innocent individuals.The complainant is asked to avail a steer (castrated bull,preferably not white in colour) and traditional beer(pketiis) <strong>for</strong> the ritual. On the material day, a last minuteappeal is made to whoever might have committed thecrime. If nobody admits guilt, one <strong>of</strong> the respected eldersannounces that the culprit (satan) who has terrorizedthe community is about to be witched <strong>for</strong> the interest <strong>of</strong>the community.A red-hot spear is used to kill the availed steer by piercingit around the chest (heart). The red-hot spear, which looksnow reddish due to blood from the steer, is pointedtowards the sun while elders murmur words, condemningthe thief (onyot) to death including members <strong>of</strong> his orher family and clan. The meat is roasted, eaten and itsremains (bones and skin) are burnt to ashes, buried or27

thrown into a river. Anybody who interferes with the steer’sremains is also cursed to death.The effects <strong>of</strong> the muma are so devastating that it canwipe out members <strong>of</strong> the whole clan if not reversed. Aftersometime, death will visit members <strong>of</strong> the familyresponsible <strong>for</strong> the theft and they start dying one by one.Interestingly, only men die as a result <strong>of</strong> muma. Theafflicted family or clan members convene a Kokwo andplead to pay back what was reported stolen so as tostop more deaths. The elders convene and a steer isslaughtered eaten and the affected family members arecleansed using traditional beer, milk and honey. Theelders reverse the rite and further deaths cease.Muma acts as a deterrent to theft and other crimes inPokot society. The process is scaring and its effectsdreadful. Nobody would like to be caught in it. It is aneffective preventive measure to internal conflicts amongthe Pokots.ii) MutaatMutaat is just like muma. It is another way <strong>of</strong> cursingand bewitching thieves in the society. Mutaat isspecifically directed at thieves unlike muma, which canapply to other crimes in society like adultery and propertydisputes.Be<strong>for</strong>e mutaat is per<strong>for</strong>med, the initial processesundertaken during muma are carried out. Only specificelders per<strong>for</strong>m the mutaat ritual. Currently permit toper<strong>for</strong>m the ritual is sought from the government (chiefs)thus validating and legitimising the ritual. Like muma,mutaat is directed towards the ‘satan’ and is per<strong>for</strong>medin daylight. The whole community participates.28

During the ritual, specific elders collect soil, put it insidea pot, and mix it with meat from a steer and otherundisclosed ingredients. (The respondents were not sure<strong>of</strong> or refused to divulge the nature <strong>of</strong> the concoction).The elders murmur words to the effect that be<strong>for</strong>e theculprit dies, he or she should open his or her mouth (talkabout the crime). The ritual is carried out in a secludedplace. The pot, with its contents, is buried and peopledispatch waiting <strong>for</strong> the results.After a period <strong>of</strong> time, the contents <strong>of</strong> the pot decompose.This heralds that somebody or groups <strong>of</strong> people are aboutto die. And immediately, the thief or thieves die one byone while admitting that he or she is the one who stolethe property in question. The family <strong>of</strong> the deceasedimmediately convenes a Kokwo pleading to pay backwhat was stolen so as to reverse the curse and saveother members <strong>of</strong> the family. A cleansing ritual similar tothat done during muma is per<strong>for</strong>med.c) AdulteryAdultery is another cause <strong>of</strong> conflict within the Pokotcommunity. An adulterous person is considered uncleanand is subjected to strenuous rituals <strong>of</strong> cleansing themoment proved guilty or caught in the act. Fornicationalso attracts a harsh penalty. In such situation, the facevalue (dowry) <strong>of</strong> such a girl is drastically reduced. Amongthe Pokot, high importance is attached to a girl’s virginityand is used to determine the bride price.Rape is a relatively new phenomenon among the Pokot.The line between adultery and outright rape is so blurredthat you cannot openly talk <strong>of</strong> the two. For the purposes<strong>of</strong> this study, rape is treated as adultery since therespondents refused to admit its existence.29

Adultery cases are handled by the Kokwo. Where thereis enough evidence to prove that somebody slept withsomebody’s wife, a Kokwo is immediately convened.i) Amaa / nwata /ighaaIf the two parties were caught in the act or admit doing it,then no time will be wasted. The man responsible <strong>for</strong>the act is fined heavily, amaa, (pays cattle more thanbride price that was paid <strong>for</strong> the woman) and is told tocleanse (mwata, ighaa) the family <strong>of</strong> the affected man.Interestingly the responsible woman is not fined but isbeaten by her husband. The mwata / ighaa cleansingritual is per<strong>for</strong>med using contents <strong>of</strong> a goat’s intestinesmixed with honey and milk.ii) KikeematIf the suspect pleads not guilty, the case will be arguedin the traditional court (Kokwo). Both sides can enlistservices <strong>of</strong> traditional lawyers and circumstantialevidence can be adduced to help the elders establishthe truth. If the couple insists that they did not committhe crime, then the Kokwo requests them to undress.Their clothes (skin clothes) are washed, mixed with someundisclosed concoctions and then drained. The two areasked to drink the resultant liquid. At this point, if oneparty admits guilt, he or she is saved the trouble <strong>of</strong>drinking the mixture leaving the adamant party to drinkthe concoction. The ritual is known as kikeemat.If kikeemat was per<strong>for</strong>med till completion and theaccused man was guilty and refused to own up,catastrophes will befall his family and if the situation isnot reversed, (ama followed by kikeemat) the man willdie. After death <strong>of</strong> the suspected man, his family willconvene a Kokwo, pay an adultery fine and cleanse thefamily <strong>of</strong> the aggrieved man.30

Kikeemat is also used in witchcraft cases. The onlydifference is that the suspects’ clothes are washed, mixedwith some herbs and the said suspects <strong>for</strong>ced to drinkthe solution. Like adultery, the suspect if indeed was awitch would die.d) MurderThe Pokot people regard murder as the act <strong>of</strong> terminatingsomebody’s life intentionally or accidentally. Killing afellow Pokot tribesman is an atrocious crime that leadsto the punishment <strong>of</strong> the whole clan or the extendedfamily <strong>of</strong> the culprit. Murderers are regarded as outcastsin the community and are not allowed to mingle withothers until and unless traditional purification (cleansing)rituals are per<strong>for</strong>med. However, it is not a big deal <strong>for</strong> aPokot to kill a person(s) from other tribe(s). In such acase, the killer is regarded as a hero and special tattoosare etched on his body as a sign <strong>of</strong> honour and respect.In murder cases, the accused may not deny if he or shewas caught in the act. However, the possibility <strong>of</strong> asuspect denying the charge exists. These scenarios arehandled differently.i) LapayLapay is sought if the suspect admits killing or was seenmurdering the deceased. Lapay is a fine or compensationin murder cases. Where lapay is administered, the familyand clan members <strong>of</strong> the deceased take all the property<strong>of</strong> the murderer including that <strong>of</strong> his clan. Lapay is acollective punishment. The whole clan pays <strong>for</strong> the sins<strong>of</strong> an individual. Its collective nature makes it a deterrentand preventive measure <strong>for</strong> murder.Lapay is an interesting method <strong>of</strong> seeking justice in thecommunity. If a murder occurs within a family, <strong>for</strong>instance, a man kills his brother, then the family/clan <strong>of</strong>31

the wife will demand that you pay <strong>for</strong> the blood <strong>of</strong> theirslain relative. One loses a family member and at thesame time all his property is taken.There is no standard fine <strong>for</strong> murder. The fine is largelycircumstantial. A heavier penalty will be administered ifthe deceased was married than if the victim was single.Also, if your bull kills somebody then you will be liable tolapay. Women victims attract a lenient fine.ii) KokwoIf a suspect pleads not guilty to a murder charge, a Kokwois convened and the case is argued with both sidesgetting ample time to argue their case. Circumstantialevidence is adduced be<strong>for</strong>e the court. If the traditionalcourt proves the suspect guilty, lapay is prescribed asthe judgement. The family <strong>of</strong> the deceased immediatelyassumes ownership <strong>of</strong> the murderer’s property togetherwith that <strong>of</strong> his clan. In case the court fails to prove thatthe suspect is guilty, and the plaintiffs argue that thesuspect has a case to answer, then muma is prescribed.This is the last resort.e) Land DisputesLand disputes are a relatively new phenomenon amongthe agro-pastoralists Pokot. This kind <strong>of</strong> conflict is morepronounced in agriculturally productive and settled placesand also along riverine areas where crop farming/furrowirrigation is practiced. Among the pastoralists, land is acommunal property and is administered by elders <strong>for</strong>the benefit <strong>of</strong> the whole community. This is also rein<strong>for</strong>cedby the fact that their land is generally arid making nomadicpastoralism the only suitable means <strong>of</strong> livelihood. Thequestion <strong>of</strong> land ownership is seen as an impediment tonomadism and a capitalist lifestyle in a community whichis essentially socialist.32

In the high potential areas, land has been adjudicatedand given to individuals as private property. This has notonly bred conflicts within the community but is alsoresponsible <strong>for</strong> the escalating inter-ethnic conflicts inKenya. At the family level, land conflicts might plungethe whole family into chaos that could lead to death.Land and other minor disputes in Pokot community aredealt with at different levels. Land disputes betweenfamily members are solved by the family, extended family,the immediate neighbours and where necessary at theKokwo. Agreements and verdicts are based onconsensus. Kokwo is the Supreme Court and nobodycan appeal against its ruling. However, based on new oremergent evidence, the Kokwo can be reconvened todeliberate on the matter based on the new evidence.f) WitchcraftWitchcraft is not tolerated in Pokotland. Witches arecategorised with murderers in the community anddeserve to die in the most painful way possible. Conflictsdo arise when certain individuals, family or clan membersare suspected to be witches. Whenever a calamityoccurs, blame is apportioned to the suspected witchesand this might breed hatred, animosity and eventualviolence in the community. Families or clans that aresuspected to be witches or harbouring witches are notallowed to participate in important cultural rituals andceremonies.From the <strong>for</strong>egoing, it can be inferred that the prohibitivefines, the collective nature <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the punishments,and the strenuous process involved in purification makesPokot customary methods <strong>of</strong> conflict managementpreventive and highly respected. However, the majordrawback is that this method can’t be applied to otherethnic groups thus limiting its impacts and efficacy to33

community level. Nevertheless, it has put the Pokot socialfabric closely knit.3.3. Pokot Inter-ethnic ConflictsConflicts with other communities is best manifestedthrough cattle rustling, a practice that has ravaged theGreater Horn <strong>of</strong> Africa. All other <strong>for</strong>ms <strong>of</strong> inter-ethnicconflicts are pegged on cattle rustling and expansivetendencies <strong>of</strong> the Pokot people. The community is inconstant conflicts with neighbouring Turkana,Karamojang, Marakwet, Sabiny and Bukusucommunities. Karamojang and Sabiny communities arein Uganda but they regularly raid the Kenyan Pokot. Thisis the region where cattle have been stolen and movedso many times that it is difficult to ascertain the rightfuloriginal owners.3.3.1. Causes <strong>of</strong> Inter-ethnic ConflictsThe Pokot community has advanced a number <strong>of</strong>reasons to explain the increasing cases <strong>of</strong> cattle rustlingand inter-ethnic conflicts. Cattle rustling is permitted if itis intended <strong>for</strong> restocking especially after a period <strong>of</strong>severe drought or disease outbreak. Meanwhile warriorsare under pressure to raise enough cattle <strong>for</strong> dowrypurposes, which can be as high as 100 cattle. Thistraditional culture is amplified by stereotypes andprejudices which depict other communities as inferior interms <strong>of</strong> military superiority. Turkana and Karamojangare considered as lesser men <strong>for</strong> they don’t circumcisetheir boys.Competition over scarce pasture, dwindling grazing landas a result <strong>of</strong> expanding agricultural land and waterresources are perhaps the main causes <strong>of</strong> conflictbetween Pokot and her neighbours. The community isin constant conflict with the Karamojang, Turkana andSabiny communities owing to scarcity <strong>of</strong> resources.34

The flow <strong>of</strong> arms into the hands <strong>of</strong> Pokot warriors hasincreased the severity <strong>of</strong> conflicts. Pokot proximity toUganda and southern Sudan’s gun merchants has madeguns easily available and cheap to acquire. A study bySecurity Research and In<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>Centre</strong> (SRIC)Pr<strong>of</strong>iling Small Arms and Light Weapons in the NorthRift, reports that there are over 44,710 assorted rifles inPokot land. This situation has commercialised cattlerustling. The urge to own a gun and ammunition has ledto raids. The proceeds from stolen animals are used toacquire guns. Barter trade also takes place whereanimals are exchanged <strong>for</strong> guns.Land conflicts between Pokot community and herneighbours is another manifestation <strong>of</strong> inter-ethnicconflicts. History has it that the Pokot community waschased away from the current Trans Nzoia district tocreate the white highlands. Upon independence the postcolonial administration settled other communities in the<strong>for</strong>mer white highlands and the Pokot communitycontinued to live in the dry, arid and rocky present dayhome. Pokot’s conflict with the Bukusu in Trans Nzoia isan <strong>of</strong>fshoot <strong>of</strong> the bitter memories <strong>of</strong> their ancestralgrazing land.Political incitement is another relatively new dimension<strong>of</strong> inter-ethnic. Political leaders are on record as havingincited Pokot-Marakwet conflicts in the Kerio valley. Thisconflict became pronounced immediately after the dawn<strong>of</strong> political pluralism in Kenya in the early 90s. Marakwetcommunity was seen as betraying the larger Kalenjinpolitical destiny as they were leaning towards the politicalpluralists.The respondents also cited insensitive governmentpolicies as a cause <strong>of</strong> inter-ethnic conflicts between Pokot35

and her neighbours. The Pokot community is consideredas embracing illogical cultural attachment to large herds<strong>of</strong> animals, which is environmentally destructive. Thedistrict is least developed, further rein<strong>for</strong>cing theargument that government’s development plans favoursome districts.Women, especially girls among the Pokot are a knowncatalyst <strong>of</strong> conflicts. They sing war songs that praisesuccessful warriors and ridicule those considered asunder per<strong>for</strong>mers in cattle raids. Warriors who have killedenemy <strong>for</strong>ces are spoon-fed by girls and given specialgoatskin clothes (atele) as a sign <strong>of</strong> honour. Bravewarriors are also smeared with special oil made frommilk or animal fat on their <strong>for</strong>eheads. Such practiceswould prompt warriors to engage in cattle raids and killas many enemy warriors as possible.3.3.2. Prevention <strong>of</strong> Inter-ethnic Conflictsa) Traditional Early WarningTraditional early warning among the Pokot communityinvolves collection <strong>of</strong> sensitive intelligence in<strong>for</strong>mationconcerning other communities’ security and externalthreats. A number <strong>of</strong> methods are employed in collectingand disseminating military in<strong>for</strong>mation to the communityso as to take preventive measures.Casting <strong>of</strong> skin sandals by knowledgeable and expertcommunity elders can <strong>for</strong>etell an impending attack onthe community. Other elders can verify such in<strong>for</strong>mationand if similar findings are obtained, then the intelligencereport is disseminated to the community. To <strong>for</strong>etell animpending strike, such experts <strong>of</strong>ten consult intestines<strong>of</strong> goats. Such in<strong>for</strong>mation is very accurate and thecommunity members adhere to it. In such a situation,the community members are advised to move away fromdanger spots together with their livestock. Warriors are36