2011-2012 - Center for Khmer Studies

2011-2012 - Center for Khmer Studies

2011-2012 - Center for Khmer Studies

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

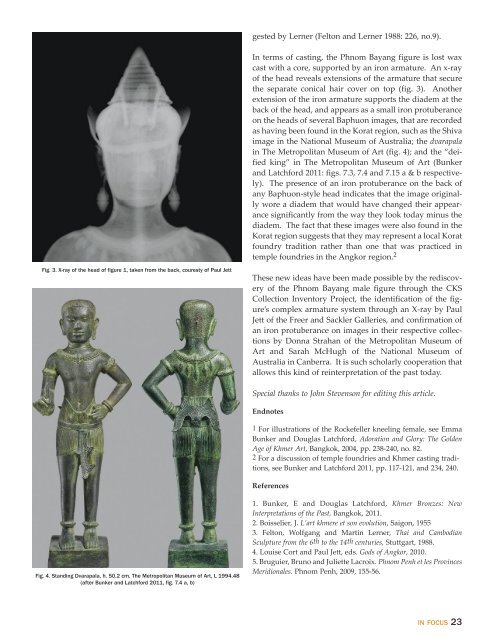

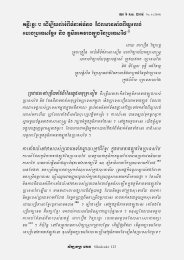

gested by Lerner (Felton and Lerner 1988: 226, no.9).In terms of casting, the Phnom Bayang figure is lost waxcast with a core, supported by an iron armature. An x-rayof the head reveals extensions of the armature that securethe separate conical hair cover on top (fig. 3). Anotherextension of the iron armature supports the diadem at theback of the head, and appears as a small iron protuberanceon the heads of several Baphuon images, that are recordedas having been found in the Korat region, such as the Shivaimage in the National Museum of Australia; the dvarapalain The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 4); and the “deifiedking” in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Bunkerand Latch<strong>for</strong>d <strong>2011</strong>: figs. 7.3, 7.4 and 7.15 a & b respectively).The presence of an iron protuberance on the back ofany Baphuon-style head indicates that the image originallywore a diadem that would have changed their appearancesignificantly from the way they look today minus thediadem. The fact that these images were also found in theKorat region suggests that they may represent a local Koratfoundry tradition rather than one that was practiced intemple foundries in the Angkor region. 2fig. 3. X-ray of the head of figure 1, taken from the back, couresty of Paul JettThese new ideas have been made possible by the rediscoveryof the Phnom Bayang male figure through the CKSCollection Inventory Project, the identification of the figure’scomplex armature system through an X-ray by PaulJett of the Freer and Sackler Galleries, and confirmation ofan iron protuberance on images in their respective collectionsby Donna Strahan of the Metropolitan Museum ofArt and Sarah McHugh of the National Museum ofAustralia in Canberra. It is such scholarly cooperation thatallows this kind of reinterpretation of the past today.Special thanks to John Stevenson <strong>for</strong> editing this article.Endnotes1 For illustrations of the Rockefeller kneeling female, see EmmaBunker and Douglas Latch<strong>for</strong>d, Adoration and Glory: The GoldenAge of <strong>Khmer</strong> Art, Bangkok, 2004, pp. 238-240, no. 82.2 For a discussion of temple foundries and <strong>Khmer</strong> casting traditions,see Bunker and Latch<strong>for</strong>d <strong>2011</strong>, pp. 117-121, and 234, 240.Referencesfig. 4. standing Dvarapala, h. 50.2 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, L 1994.48(after Bunker and Latch<strong>for</strong>d <strong>2011</strong>, fig. 7.4 a, b)1. Bunker, E and Douglas Latch<strong>for</strong>d, <strong>Khmer</strong> Bronzes: NewInterpretations of the Past, Bangkok, <strong>2011</strong>.2. Boisselier, J. L’art khmere et son evolution, Saigon, 19553. Felton, Wolfgang and Martin Lerner, Thai and CambodianSculpture from the 6th to the 14th centuries, Stuttgart, 1988.4. Louise Cort and Paul Jett, eds. Gods of Angkor, 2010.5. Bruguier, Bruno and Juliette Lacroix. Phnom Penh et les ProvincesMeridionales. Phnom Penh, 2009, 155-56.in focus 23