The Korban Pesach Of The Shomronim – Samaritans - Halachic ...

The Korban Pesach Of The Shomronim – Samaritans - Halachic ...

The Korban Pesach Of The Shomronim – Samaritans - Halachic ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

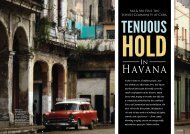

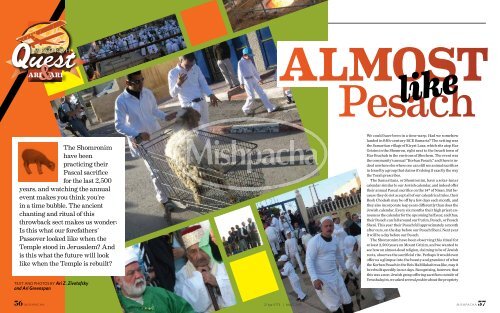

Subjectuestmesor ahQARI ARIAlmostlike<strong>Pesach</strong><strong>The</strong> <strong>Shomronim</strong>have beenpracticing theirPascal sacrificefor the last 2,500years, and watching the annualevent makes you think you’rein a time bubble. <strong>The</strong> ancientchanting and ritual of thisthrowback sect makes us wonder:Is this what our forefathers’Passover looked like when theTemple stood in Jerusalem? Andis this what the future will looklike when the Temple is rebuilt?Text and Photos By Ari Z. Zivotofskyand Ari GreenspanWe could have been in a time warp. Had we somehowlanded in fifth-century BCE Samaria? <strong>The</strong> setting wasthe Samaritan village of Kiryat Luza, which sits atop HarGrizim in the Shomron, right next to the Israeli town ofHar Brachah in the environs of Shechem. <strong>The</strong> event wasthe community’s annual “<strong>Korban</strong> <strong>Pesach</strong>,” and there is indeednowhere else where one can still see animal sacrificesin Israel by a group that claims it’s doing it exactly the waythe Torah prescribes.<strong>The</strong> <strong>Samaritans</strong>, or <strong>Shomronim</strong>, have a solar-lunarcalendar similar to our Jewish calendar, and indeed offertheir annual Pascal sacrifice on the 14 th of Nisan. But becausethey do not accept all of our calendrical rules, theirRosh Chodesh may be off by a few days each month, andthey also incorporate leap years differently than does theJewish calendar. Every six months their high priest announcesthe calendar for the upcoming half year, and thus,their <strong>Pesach</strong> can fall around our Purim, <strong>Pesach</strong>, or <strong>Pesach</strong>Sheni. This year their <strong>Pesach</strong> fell approximately a monthafter ours, on the day before our <strong>Pesach</strong> Sheni. Next yearit will be a day before our <strong>Pesach</strong>.<strong>The</strong> <strong>Shomronim</strong> have been observing this ritual forat least 2,500 years on Mount Grizim, and we wanted tosee how an almost-dead religion, claiming to be of Jewishroots, observes the sacrificial rite. Perhaps it would evenoffer us a glimpse into the beauty and grandeur of whatthe <strong>Korban</strong> <strong>Pesach</strong> in the Beis HaMikdash was like, may itbe rebuilt speedily in our days. Recognizing, however, thatthis was a non-Jewish group offering sacrifices outside ofYerushalayim, we asked several poskim about the propriety56 MISHPACHA 21 Iyar 5773 | May 1, 2013 MISHPACHA 57

SubjectThis is where the lambswould be roasted, cookedwhole without any ofthe bones broken, as theTorah stipulatesREADY FOR THE RITE Amonghundreds of onlookers, piecesof olive wood are dropped intothe fire, while the “shochet” (R)prepares for the moment of sunsetof attending the event, and were assured thatit was not halachically problematic. We werenot disappointed by our visist.<strong>Pesach</strong> Cleaning (Again) As<strong>Pesach</strong> approaches, most Jewish householdsgo into frantic preparation mode,with last-minute arrangements that includefinishing up the remaining bits ofbread and noodles, buying matzoh, macaroons,and other Passover necessities,and cleaning the house of crumbs. Aswe entered this Samaritan village alongwith the throngs of other tourists, thelocals were indeed frantically preparingfor <strong>Pesach</strong> in the same manner, justa month later.But what’s not included in our to-do listis purchasing a live lamb for the <strong>Korban</strong><strong>Pesach</strong> and readying the pit for roasting it.But 2,000 years ago, when the Beis HaMikdashstood in Yerushalayim, that was mostcertainly a concern of the typical household,based on the biblical injunction that eachperson must eat from the Passover sacrifice.Indeed, that is exactly what the <strong>Shomronim</strong>were doing as we meandered through theirsmall town.So who are the <strong>Shomronim</strong>, and whydo they preserve this ancient ritual? <strong>The</strong>760-strong <strong>Shomronim</strong> — probably thesmallest ethnic group in the world — areactually the remnants of a group mentionedin Tanach and whose halachic status isdiscussed extensively in the Gemara. Todaytheir community is divided between theTel Aviv suburb of Holon and Har Grizim— overlooking Shechem.After exiling much of the Ten Tribes(Melachim II 17:24), the king of Assyriabrought other peoples into the emptiedcities of Israel, a cross-population transfertechnique the Assyrians used in all theiroccupied lands as a method of reducingrebellions among the natives. Among thepeople brought into Israel were the Kutim,who settled in Samaria, and were thus laterknown as <strong>Shomronim</strong> or <strong>Samaritans</strong>.After the <strong>Shomronim</strong> were plagued by lionsbecause they were worshipping idols, akohein was sent from Assyria to teach themNO BROKEN BONES Ari Z. and Ari G.examine the whole carcass, after theSamaritan high priest (Top) is escortedto the seat of honorTorah, and they evidently converted —although they continued their idol worship.This led to great ambiguity in theirhalachic status, and Chazal discuss innumerous places in the Talmud whetherthey were “gerei emes” or “gerei arayos” —sincere converts or not — even devoting anentire Maseches Kutim to these laws. Inthe end, Chazal declared them to be non-Jews. Furthermore, they never acceptedthe halachah of the Oral Torah.<strong>The</strong> Kutim, however, give a differentversion of their origin. <strong>The</strong>y claim tobe descendants of the tribes of Efraimand Menasheh, plus some Kohanim andLeviim, arguing that they are the “trueJews,” preserving the original Judaism.<strong>The</strong>y therefore do not call themselves“<strong>Shomronim</strong>,” after the region, but rather“Shamerim” — which means “the observant”in Samaritan Hebrew — or “Bene-Yisrael.” This claim is ancient, althoughRabi Meir in Bereishis Rabbah mockstheir assertion.Still, the <strong>Shomronim</strong> today claim anabsolute belief in monotheism and totaladherence to the Torah. However, theyreject the rest of the books of Tanachand the oral traditions as preserved byChazal. Our contact person in the communitywas able to effortlessly rattle offlarge sections of Chumash by heart andhe reported that by age six or seven heknew a good deal of the Torah.Fires on the Mountain <strong>The</strong><strong>Shomronim</strong> go about their practicesquietly, but the Samaritan <strong>Korban</strong><strong>Pesach</strong> has become quite a tourist attraction,and already as we arrived atthe bottom of the mount, we saw justhow big it would be this year, with thearmy blocking off the access road andrequiring everyone to park below andtake shuttle buses up. <strong>The</strong> other passengerson our shuttle, like the mobsthat we later encountered up on themountain, were an interesting crosssection of the population: Tel Avivians,chareidim from Bnei Brak, agroup of British English teachers whoare spending a year in Shechem, and agroup of seniors from Rishon L’Tzion.We waited for our Samaritan contactperson, who smoothly escorted us intothe enclosed area and showed us to ourVIP seats (which were prearranged by afriend who is a Knesset member), cheerfullyanswering our many questions abouttheir customs. Throughout the eveningwe managed to speak to quite a few <strong>Samaritans</strong>who were friendly and forthcomingin explaining their foreign-yetfamiliarrituals.In the inner area, we were overwhelmedby six three-meter-deep fire pits. This iswhere the lambs would be roasted, cookedwhole without any of the bones broken, asthe Torah stipulates. <strong>The</strong> heat from thepits is fearsome, and we were surprisedto see young boys walking so near theedges that we were afraid of somebodyfalling in. Each family unit has its ownanimal and several are assigned to eachpit where the sheep are roasted.A tumult in the crowd alerted us to58 MISHPACHA21 Iyar 5773 | May 1, 2013 MISHPACHA 59

Almost like <strong>Pesach</strong>a solemn procession coming down themain street of the village. <strong>The</strong>ir high priestand helpers arrived in ornamental religiousgarb, and the gates to the innersection were now closed. We were fortunateto be inside, together with armybrass, politicians, and other communalrepresentatives.Between the village entrance and theceremonial enclosure, we passed the <strong>Samaritans</strong>’house of worship, which, likemany of the buildings, included a mezuzah— but not the rolled parchment typethat graces our doorways. Our mesorahis that the mezuzah contains the firsttwo paragraphs of the Shema written onparchment; theirs have biblical verses oftheir choice, engraved on stone and placedabove the doorway. <strong>The</strong> text is not writtenin the more “modern” Hebrew scriptknown as ksav Ashuri, but in the ancientHebrew script known as ksav Ivri.<strong>The</strong>ir Torah, too, is written in ksav Ivri,which was the standard script used by ourancestors before the Babylonian Exile, andwhich continued to be used sporadicallyduring the Second Temple period. However,while Jews gradually and finallyswitched to ksav Ashuri, the <strong>Shomronim</strong>bucked the tide and preserved a modifiedversion of the ancient script.<strong>The</strong> preservation of the ancient scriptis mentioned in writings throughout thegenerations: <strong>The</strong> Ramban sought the helpof the <strong>Samaritans</strong> in deciphering thetexts of ancient coins; the 15 th -centuryRav Yaakov Tam dealt with the issue ofusing a paroches from a Cairo <strong>Samaritans</strong>ynagogue that contained inscriptionsin Samaritan script; and in the 1500sthe Radbaz was asked about using large,60 MISHPACHAerased Samaritan tombstones that hadbeen stolen by non-Jews and then soldto Jews in Egypt.<strong>The</strong> afternoon had been spent in preparation.<strong>The</strong> young men lighting the fireswith huge pieces of heavy olive woodwere all wearing white garments andheaddresses instead of their usual streetclothes. In years past, the Muslims madethem wear a red head covering to distinguishthem from the neighboring Muslims.This has become their weekdaygarb, but on their Sabbath and holidaysthey wear white.About 50 lambs were brought into theenclosure, all to be slaughtered at thesame second. <strong>The</strong> Torah instructs thatthe <strong>Korban</strong> <strong>Pesach</strong> should be slaughtered“bein ha’arbaim” — literally “between theevenings.” <strong>The</strong> Talmud understands thisto mean all afternoon, but the <strong>Samaritans</strong>require that it take place exactly at theinstant of sunset. As sunset approached,the elderly high priest (replacing the highpriest who passed away suddenly, just afew days before their <strong>Pesach</strong>) enteredthe area, mounted a platform dressed inan interesting silk, tallis-like cloth withgreen stripes.He began reciting prayers and versesfrom Exodus in an ancient Hebrew pronunciation.For example, when he got toHashem’s name, instead of pronouncingit as it is written, he uses the Aramaicword for the “the Name” similar to ouruse of the word Hashem. Much of it wasrecited in unison, and clearly most of theparticipants knew the nusach by heart.<strong>The</strong>y are used to a long prayer service, astheir Sabbath davening, almost all of it intheir unique Aramaic dialect, goes from 3GOOD YOM TOV A dab of blood on the forehead is abrachah for a happy holiday; a Samaritan “mezuzah” withthe verse of choice graces the lintelto 6 a.m. While most of the dialect was unintelligible to us, at one point we heard arepeated mention of “Elokei Avraham, Elokei Yitzchak, v’Elokei Yaakov.”Because of the biblical commandment “an altar of earth shall you make” (Shemos20:21), the <strong>Shomronim</strong> do not have a raised altar as the Jews had, but rathermake a trench lined with stones, fulfilling the verse, “If you build for Me an altarof stones” (Shemos 20:22). Most of the men were standing along the long trenchwith their sheep, while the women were seated in a separate area.“Kill It at Dusk” <strong>The</strong> liturgic chanting lasted for about half an hour, andthen suddenly it sounded like someone had opened a beehive. <strong>The</strong> assembledrealized that the actual slaughter time was approaching, and so they flippedthe sheep, pulled out their knives, and then the high priest recited the versefrom Shemos 12:6: “And the whole assembly of the children of Israel shall killit at dusk.” At that instant there was a sudden flurry of blessings and commotionas the slaughterers each did their job.Next the butchers and flayers got to work. It was difficult to know what was happeningas so much simultaneous activity was taking place. We noticed that manyof the slaughterers had drops of blood on their foreheads. As shochtim ourselves,we understood that sometimes the blood splatters and leaves drops on your face.But that so many of them should have blood on the forehead seemed too coincidental.It turns out that this is their way of saying “chag sameach.” <strong>The</strong>y approacheach other and dab some of the blood on the other person’s forehead as they hugand wish each other a happy holiday.Women started appearing with pita-like matzoh that had been baked the nightbefore, and they explained that during that day they were prohibited to eat bothmatzoh and chometz, but now they could eat the matzoh. Several men showed upcarrying large bundles of hyssops (eizov), which were dipped in the blood and takenback to the houses where it was smeared on the lintel.Soon there was a choking smell of burning hide — because the hide is not eaten,it must be burnt. Indeed, the innards were already being burnt within minutes,and anything left over would also be burnt in fulfillment of the verse in Shemos12:10. Salt was placed on the carcasses, in fulfillment of the Torah instruction thatTop Signs YouHave a Bed BugInfestation:SpecksDuring the mid 90’s however, the bedbugs seemed to have disappearedwithout a trace with barely a fewisolated incidents and sightings acrossthe globe. However off late, the insectshave been making a resoundingcomeback across the world withcountries like the US and severalEuropean countries having to grapplewith a severe bed bug problem ontheir hands.Concerned You May Have Bed Bugs?ScHEDUlE aK9 Inspection*When used inconjunction with a<strong>The</strong>rmaRid treatment.Hassle-FreeTotal Bed BugEradicationThroughHeatTreatment$95877.987.7013www.thermarid.com21 Iyar 5773 | May 1, 2013 MISHPACHA 61SpECIal *parkmg.com

Subject<strong>The</strong> country’s second largestprivately owned commercial mortgagecompany on a transaction volume basisAncient Tribe onthe Mountain ofBlessingTalmudic literature is filled with referencesto the Kutim, or the <strong>Shomronim</strong>. Werethey true converts, or did they convertonly out of fear? Some of the halachicdiscussions include such questions aswhether the shechitah of a Kuti is kosheror whether his matzoh is acceptable. Regardingsome mitzvos, the Gemara assertsthat they were exceedingly carefuland could be relied upon.But most of these discussions wereonly relevant before the big schism, relatedin Chullin 6a, that the Kutim werefound to be worshipping a dove-shapedidol on Har Grizim. <strong>The</strong>y were then declaredto be non-Jews. Rabbi Meir declaredtheir wine as the wine of goyimand their shechitah as that of a non-Jew.From that point forward, halachah hastreated them as non-Jews.If they do consider themselves keepersof the original tradition, why then do theyoffer their sacrifices on Har Grizim andnot in Yerushalayim? Examining theirversion of the Torah together with recentarchaeological excavations on Har Grizimcan explain it. When they first settled theregion, Yerushalayim was in the separateKingdom of Yehudah; later it was inruins. Thus, they ever-so-slightly editedthe Torah, adding a verse after the TenCommandments stating that Har Grizimwill be the location of the permanent altar.After all, Har Grizim is the “mountainof blessings,” where, upon entering theLand, half the tribes stood and deliveredblessings while the tribes on the oppositeHar Eval delivered curses. And in theSamaritan bible, Yehoshua’s altar at HarEval was “moved” to Har Grizim.Archaeologists have actually found theruins of a Samaritan temple built on HarGrizim in the first half of the fifth centuryBCE. That site, with all of the subsequentlydiscovered ruins, was openedwithin the past year to the public as a nationalpark. On display is the stone thatthey claim was the site of the Akeidah,which they also believe took place onHar Grizim and not on Jerusalem’s HarHaMoriah.<strong>The</strong> Babylonians and later the Romansdestroyed the Temples in Jerusalem, butwho destroyed this Samaritan temple?<strong>The</strong> answer: the Jews. In about 128 BCE,the Hasmonean king Yochanan Hyrcanusdestroyed the Samaritan temple that hadstood on Har Grizim for over 200 years.Only a few remnants of it exist today. <strong>The</strong>day of their temple’s destruction is actuallylisted as a holiday in Megillas Taanis.<strong>The</strong> Kutim wanted Alexander Mokdon(aka Alexander the Great) to destroythe Beis HaMikdash, but the decree wasabolished and their own sanctuary wasdestroyed instead.Because of the centrality of Har Grizim,the <strong>Shomronim</strong> direct their prayers in itsdirection and make pilgrimages here ontheir festivals. In fact, the swapping of HarGrizim for Yerushalayim so irked Chazalthat Maseches Kutim concludes with thepassage: “When will we take them back?When they renounce Har Grizim and acceptYerushalayim and techiyas hameisim[resurrection of the dead].”Despite the animosity between theJews and the <strong>Shomronim</strong>, their ranksswelled, and by the fourth century CEthey numbered over a million in the entireMediterranean area, briefly winningindependence from the Byzantine Empire.But subsequent failed rebellions,oppression by the local Arab population,and assimilation thinned their ranks; in1919 there were only 141 <strong>Samaritans</strong> inthe entire world. <strong>The</strong> community hasrebounded, though, and today the <strong>Samaritans</strong>number over 750 individuals.This rejuvenated group is divided almostequally between the city of Holonand their refurbished village overlookingShechem. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Samaritans</strong> in Holon seethemselves as fully Israeli and serve inthe IDF; those on Har Grizim live underthe Palestinian Authority.In recent decades, <strong>Samaritans</strong> have allowedtheir men to intermarry with Jewishwomen, provided that the womanaccepts the Samaritan religion; however,rabbinic authorities never allow intermarriagewith <strong>Samaritans</strong>. Marriage witha Kuti was already prohibited even beforethey were declared full-fledged non-Jews. <strong>The</strong>re are even opinions that a Kutiwho converts is not permitted to marry aJew other than another convert. Becausethe Jewish option isn’t realistic, anotherrecent solution to the shortage of Samaritanmarriage partners is the importationof non-Jewish brides from the Ukraine.PRIESTLY BLESSINGS <strong>The</strong> ancient Aramaic chanting sounds asmysterious today as it did a hundred years agoevery korban have salt on it (Vayikra 2:13). Because they view the matzoh as sacrificialas well, they add salt to the flour-water dough.At this point, many of the Samaritan women and children left while the men continuedto butcher the animals in fulfillment of other commandments. <strong>The</strong>y removedthe right forearm of every animal in preparation for giving it to the priests as gifts,and they excised the gid hanasheh. During this entire process, the head remainedattached because of the prohibition to not break any bones of the korban (Bamidbar9:12). In fact, one young man told us that even when they eat it, they are careful notto break any of the sheep’s bones.Once the whole lambs were put on huge stakes, they were lowered down into thehot pits to cook. <strong>The</strong> fire would incinerate the meat, so as soon as a carcass went in, acloth was put over the pit and children shoveled wet mud onto it. This cut off the supplyof oxygen, putting out the flame and letting the heat do its trick. <strong>The</strong> aroma was abarbecue-lover’s heaven, and now we could dream about what it must have been likein Yerushalayim during the actual Pascal sacrifice.Later, when it was well past dark, the tiny Samaritan community would sit downto their equivalent of a Passover Seder complete with a Pascal lamb. Every single oneof them would be tasting of the korban. Our host admitted that he is a vegetarian buthe, too, would have a little taste, approximately a “quarter zayit,” he told us. Accordingto Samaritan tradition, anyone who does not taste of the meat essentially severshis link to the community. And, because there is no concept of bar or bas mitzvahstatus, even the tiniest infant is given a taste of the korban, just as every weaned childfasts on the <strong>Shomronim</strong>’s only fast day, Yom Kippur.While we knew we were watching a rite performed by a small, non-Jewish minorityliving within our midst, we nonetheless left with a flood of interesting and conflictingthoughts and emotions. Who really was this community? How many of their traditionsare remnants from the ancient practices of our own ancestors? Is this what ourforefathers’ Passover looked like when the Temple stood in Jerusalem, and if not,how did it differ? And most significantly, how does this resemble the future Passoverwhen there will be a rebuilt Temple? As we made our way down the mountain, weoverheard many Jews —who, like us, had come to observe — declaring wistfully thesame thoughts we harbored: “Next year in Yerushalayim!” —62 MISHPACHA 21 Iyar 5773 | May 1, 2013 MISHPACHA 63

![llVtlwnl 1p1l 1biip 3 K11lnM o1it1 [1] - Halachic Adventures](https://img.yumpu.com/35271577/1/190x253/llvtlwnl-1p1l-1biip-3-k11lnm-o1it1-1-halachic-adventures.jpg?quality=85)